PARADISE*

Tivien Andrews-Homerang

Grace Hasu Dlabik

Sione Monū

Tearia Teaiwa Mortimer

Nicholas Mortimer & Katerina Teaiwa

Alexander Sarsfield

Curated by: Dan Toua

Image Grace Hasu Dlabik Ivosa & Goava, 2024

Toru Uta fired earthenware, 42 x 25 x 25cm and 34 x 32 x 32cm

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Paradise* began as a question.

What does “paradise” mean when you’re far from the place it was promised to be?

to Australia - by force or deception - as indentured labourers. While acknowledging this dark past, Tivien also offers a vibrant portrait of urban PNGAustralian life today with their new suite of works. Featuring emblems of PNG life (bilum, kina, malagan) these works remind us that the Pacific is not an ethnographic footnote. We are a living, thriving, culture that continues to adapt and evolve.

For the Pasifika diaspora, “paradise” is a story we’ve inherited: lush islands, swaying palms, endless blue seas. But our lived experiences rarely fit so neatly. Hence the asterisk - it’s a signal. It invites pause. It marks complication. It gestures towards silences, footnotes, and contested histories.

Paradise* brings together artists who navigate what it means to carry ancestral knowledge, ritual, and identity across oceanic and generational distances. Together, they speak back to colonial legacies, settler expectations, and extractive representations of the Pacific, while offering alternative ways of being and belonging.

Sione Monū’s installation Beaded Dreams is a work of sparkling introspection, reflecting on their life lived across the Tasman Sea. The series began in 1998, in Werribee, Melbourne, and has evolved over years and different postcodes, here in Australia, and in Aotearoa. Using materials from their childhood (plastic beads, glitter foam, foam board), Sione mimics what was available in diasporic communities for adornment and artmaking. These materials also come with environmental costs. As Sione says “these highlight the complexity of the diasporic existence: survival of culture and self today, holds the environmental complications tomorrow.” But this work also holds hope. Sione calls it “a cautious joy, a rare celebration.” Indeed, Sione’s practice reimagines traditional Tongan forms through queer futurity, holding space for softness and strength.

This tension is mirrored in Tivien Homerang-Andrews’ Blackbirding series, which unapologetically references Australia’s slave trade of some 62,000 South Sea Islanders that began in the 1860s. Tivien’s haunting oil paintings recreate scenes of Islanders brought

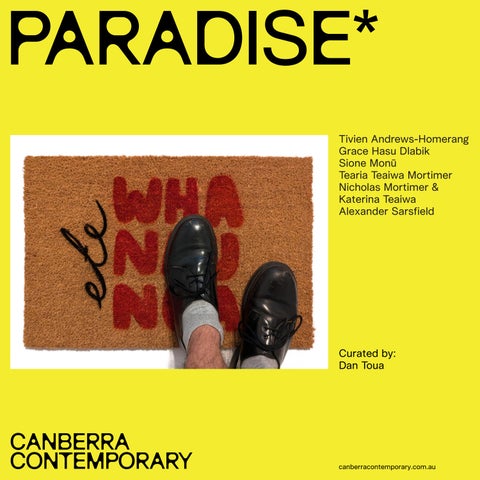

This fusing of contemporary energy with ancestral reverence is clear in Alexander Sarsfield’s installation, Standing on the Paepae. Paepae is a Te Reo Māori word denoting a doorsill, a threshold, an orators’ bench - a physical and symbolic space on the marae. A space of transition, welcome, conversation and negotiation, the paepae is integral to being received into culture, even if it is not wholly your own. An installation of humble doormats, doused in the colours of the national Maori flag, they are each emblazoned with familiar comforting words every Islander hears on returning home. The artist explains: “This work speaks directly to the awkwardness of waiting on the doorstep - wondering if you should have brought more food - and to the resolution of being welcomed onto one’s marae, feeling a little less like a guest when you leave.”

Like all things in the Pacific, No Fear of Flying is a family affair. Created by Tearia Teaiwa Mortimer, Nicholas Mortimer and Katerina Teaiwa, these photographs were inspired by a poem written by Katerina’s sister, Teresia Kieuea Teaiwa, titled Fear of Flying. Written in a mix of English and broken Gilbertese (another colonial legacy), the poem references a central motif in Banaban dance, and speaks of the filight of the frigate bird, magic, of connection to the natural world around us. It hints at the damage colonisation has caused, leading to self-doubt, a ‘fear of flying’. But it is only a fear, not an inability. We can succeed if we recognise our capabilities and regain trust in ourselves. We must. The photographs that are borne from this poem reflect this. In them, Tearia is captured in full flight: arms outstretched, leaping, dancing, flying, suspended in the black night. Tearia upends the stereotype of the docile Islander and offers instead an image of strength, courage, and self-determination.

Image Sione Monū Fob Tabies, 2025

Foam, beads, glitter, fishing line, 50 x 48cm

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Grace Hasu Dlabik’s hand-formed stoneware vessels resonate deeply with her maternal ancestral line, each symbolising her great grandmothers, Ivosa and Goava, from the Lavaipia and Botai Clans of Papua New Guinea. Each vessel speaks to the female form; of birth, discovery and the cyclical renewal of life. Wrapped in twining and palm leaves, each piece is fired in ‘toru uta’ (hole in the ground), whereby the moisture from the leaves creates smoke that forms an imprint, telling its own birthing story. While the work is symbolic of beginnings, it also reveals the threat facing cultural practice. In Grace’s home village, there is only one elder left with the knowledge to continue this tradition. The natural materialsclay, sea water, sand - are increasingly polluted and compromised. Once highly valued, these pots are no longer widely traded. The vessels embody both beauty and urgency: they honour matrilineal strength while sounding a quiet alarm.

As I write, it strikes me that each artwork holds multiple complexities. And though there are tensions, these stories exist alongside each other with matterof-fact grace. I think this speaks of the ways that art can anchor diasporic identities in new lands while holding onto the depth of where we’ve come from. This work is vibrant, evolving, and grounded in lived experience. It proves that the Pasifika diaspora is not monolithic, but made up of shifting identities, humour, homesickness, and pride.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the gallery as a holding space - not just for objects, but for voices, for discomfort, for talanoa, for dreaming. I wanted Paradise* to be a place where us “third culture kids” could see ourselves reflected. A space to explore the contradictions of diasporic life: what we carry, what we’ve lost, what we’re learning, and what we’re remaking. It’s about shifting the frame; centring Pasifika ways of knowing; resisting flattening or fetishisation, and making space for stories that haven’t always been heard - stories that honour Pacific sovereignty, autonomy, and imagination.

I like to think of Paradise* as a return. A return to voice, to visibility, to the strength and beauty of culture carried forward against the current.

*but it’s not all as it seems

Dan Toua

Dan Toua is an arts worker living and working on unceded Ngunnawal and Ngambri Country (Kamberri/ Canberra, Australia).

She is an independent curator, sessional lecturer, board member, and Creative Australia peer assessor. Dan is also currently undertaking a PhD at the ANU, with the goal of developing a Curatorial Handbook to support culturally sensitive curatorial practices of Pacific cultural materials in Australian national institutions.

Dan grounds her curatorial practice in cultural autonomy, two-way relationships, and knowledge sharing. In her work, she strives to be an active part of the global push to reimagine cultural collections, exhibition development, and curatorial methodologies with a focus on anti-colonial and (re)indigenised practices.

Above Grace Hasu Dlabik

My Family’s Mat, 2025

Mixed media, 102 x 179cm

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Left Tearia Teaiwa Mortimer, Nicholas Mortimer & Katerina Teaiwa

Fear of Flying (in broken Gilbertese), 2016 Poem by Teresia Kieuea Teaiwa, 56 x 73cm

Right Tearia Teaiwa Mortimer, Nicholas Mortimer & Katerina Teaiwa

No Fear of Flying 1 - 5 (Paradise* exhibition installation), 2025 Photographs, 75 x 75cm each

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Left Tearia Teaiwa Mortimer, Nicholas Mortimer & Katerina Teaiwa

No Fear of Flying 1 - 5 (Paradise* exhibition installation), 2025

Photographs, 75 x 75cm each

Right Grace Hasu Dlabik

Porebada (Paradise* exhibition installation), 2025

Photographs, acrylic paint, 110cm x 110cm

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

Left Grace Hasu Dlabik

Porebada (Paradise* exhibition installation), 2025

Photographs, acrylic paint, 110cm x 110cm

Right Grace Hasu Dlabik

Ivosa & Goava, 2024

Toru Uta fired earthenware, 42 x 25 x 25cm and 34 x 32 x 32cm

Photo by Brenton McGeachie

be,

Left Tivian Andrews-Homerang

Where I want to

2025 Oil on canvas, 60 x 90 cm (oval)

Right Tivian Andrews-Homerang

Boluxaam Malagan, 2025 Oil on canvas, 91.5 x 91.5 cm

Photo by Brenton McGeachie