6 The Transition from a Lawyer to a BC Provincial Court Judge The Honourable Judge Shannon Keyes

7 Minding the Gap

Andrew Tang

9 Getting Older is Something to Be Proud Of W. Laurence Scott, QC

10 Reflections on a Less-Than-Linear Path in Law

Ashley Syer

12 Making a Career from My Lifelong Passion for Animal Rights

Rebeka Breder

13 Serving Those Who Serve the Greater Good Krista Vaartnou

16 Three Reasons We Struggle with Career Transitions

Iva Erceg

18 The Pandemic as My Personal Circuit Breaker

Stephen P.E. Curran

20 Transitions of the In-House Bar

Sybila K. Valdivieso

21 Life is Too Short to Hate Your Job

Sara Forte and Sarah Ewart

22 Lawyer to Mediator

Sharon Sutherland

23 Love It or Leave It? The Legal Career Edition

Karmen Masson

25 Making Aligned and Empowering Choices

Janiene Chand

26 The Path to a Flourishing Legal Practice Comes with Change

Allison Wolf From the Branch

8 Advocacy in Action

19 CLEBC Publications are Feeling the Impact of the Global Paper Shortage

27 Finding Community and Mentorship The Law Foundation of BC

30 From Summer Student to Program Director of Indigenous Justice

British Columbia Law Institute

31 New Study Paper Examines Public Hearings on Land-Use Bylaws

34 BarMoves

Volume 34 | Number 3

From the President

4 When Do We Need to Change?

Clare Jennings

Executive Director

5 CBABC 101 — Leveraging Your Membership

Kerry L. Simmons, QC

Indigenous Matters

14 Where Did My Crystal Ball Go? The Honourable Judge Alexander Wolf

PracticeTalk

28 The War for Talent

David J. Bilinsky

Dave’s Tech Tips

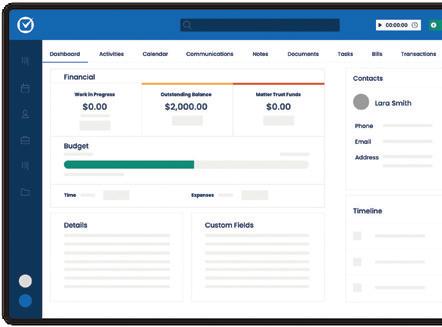

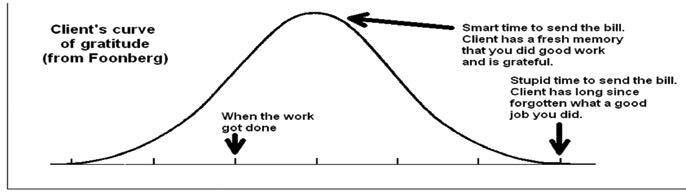

29 Time Management is the Flip Side of the Coin to Billing Time

David J. Bilinsky

Nothing Official

33 The Beverley

Tony Wilson, QC

Brandon D. Hastings, Committee Chair Editorial Committee

Tonie Beharrell Isabel Jackson Sean Vanderfluit

Eryn Jackson Lisa Picotte-Li

Deborah Carfrae, BarTalk Editor Staff Contributors

Faith Brown Michaela David Sylvie Kotyk Sanjit Purewal

BarTalk is produced on the traditional and unceded territories of the Coast Salish peoples, including the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations.

BarTalk is published six times per year by the Canadian Bar Association, BC Branch (“CBABC”) and is available at cbabc.org/bartalk. This publication is intended for information purposes only and is not legal advice.

CBABC supports more than 7,200 members in British Columbia. We connect our members to the people, knowledge, and skills they need to successfully practice.

and letters

Alyssa Brownsmith Travis Dudfield Carolyn Lefebvre Jo-Anne Stark © Copyright 2022 The Canadian

the

CLARE JENNINGS

This spring, I had the privilege of talking to lawyers across the province about the regulation of our profession, Harry Cayton’s recommendations for changes at the Law Society, and the government’s move toward a single regulator for legal professionals. As you might expect — and will see in our final report — there was a diversity of opinions and reactions.

One notable theme was the principle of change itself, and how we know when change is right, good, or even necessary. Are we changing for the sake of change alone, or are we actually improving things? Are we relying on concepts of “tradition” and “usual practice” because they retain meaning and value today, or because they are familiar and comfortable? Are we resisting specific changes for legitimate reasons, or are we resistant to any change?

Consider section 3 of the Legal Profession Act: “the Law Society must uphold and protect the public interest in the administration of justice, which includes the fundamental tenet of ensuring the independence of lawyers.” Unlike any other profession, lawyers must be free to challenge government and act contrary to its interests. An independent Bar is the source of an independent judiciary, who also must be free to hold government accountable and rule against it. This must not only be true, but be seen to be true. Can this need be met by changing the way we’re governed, or is self-governance the best and most effective way to maintain this independence? Harry Cayton’s report suggests that

self-governance is an outmoded tradition, but his assessment didn’t consider the unique role of lawyers and the legal profession.

What about access to justice? Every day, we see the access to justice issues in dealing with our clients and the courts. Our tradition of pro bono practice is not enough. Government funding for Legal Aid is insufficient to meet all needs, particularly in the family law realm. I hear regularly from frontline Legal Aid lawyers who are effectively providing pro bono services to Legal Aid clients every day, because the tariff simply doesn’t cover the breadth of services required. A robust, fully-funded legal aid system is our best and most essential tool to ensure access to justice.

access to our profession and the best service to our clients, or is change needed? We know that there is a financial barrier to entry into our profession; are we working to dismantle it?

Programs like the ELC and the UVic Law Co-op program can help, but so would student loan forgiveness and ensuring that articled students earn a living wage. We know that BIPOC and 2SLGBTQIA+ law students and lawyers face barriers to entry and in practice; are we working on a daily basis to dismantle individual or systemic barriers that not only impact our colleagues, but also our clients? Are our traditions helping or hindering us?

But we have to look beyond legal aid and pro bono. The Law Society has taken steps to address these unmet needs through its Innovation Sandbox. Lawyers are offering legal coaching and unbundled legal services. Access Pro Bono recently launched the Everyone Legal Clinic (“ELC”) (of which CBABC is a proud Founding Service Partner); not only will the ELC expand the availability of pro bono legal advice in BC, it offers an alternative entry path to our profession. What more can we do? And do we ensure that any solutions developed provide meaningful access to justice — not just service, but service that meets quality standards?

When we look at how we conduct the business of law, are we ensuring

Whether good or bad, change is uncomfortable. It pushes us out of our comfort zone. It makes us question our own actions and behaviours, along with often long-held values and assumptions about ourselves, our profession, and our communities. While it’s true that many see our profession as traditional and resistant to change, we are making changes. Lawyers should be proud of the work we have done and continue to do. That’s how we’ll ensure our profession lives up to the fundamental values underlying the need for self-governance: independence, integrity, access to justice, and loyalty and service to our clients.

Clare Jennings president@cbabc.org

KERRY L. SIMMONS, QC

If it’s been awhile since you checked out what CBABC can do for you, let me guide you to make the most of your membership. At every stage of your career, as you move into new practice areas, seek to focus or broaden your network, or want to reach a wider audience, your engagement in CBABC will support you.

Your colleagues organize Section meetings and they are the perfect place to grow your business, learn the latest, build your professional profile, and connect with others. The people you meet are your referral network. They are at the end of the phone if you want to consult on a file. You can share your knowledge as a speaker. If you are moving into a new area of practice, you’ll want to review past recordings and attend live meetings to get up to speed fast!

I recommend that everyone join and update (cbabc.org/sections/enroll) their Sections to receive notice of the meetings and practice updates. Almost all meetings are delivered virtually to be accessible everywhere in the province. And for those of you who want to gather in person with local colleagues, just ask for a Section Hub to be setup and our staff will make it happen.

We often talk about how much value newly-called lawyers get from the CBA, but let me tell you how we deliver at every stage of your career.

For those with 25 years or more of experience, the Senior Counsel Section is the place for you. Whether it is adapting to new tools, revering the role of elders, or developing your personal and professional succession

plans, you’ll be among trusted colleagues facing similar challenges.

Mid-career lawyers have so many opportunities in CBABC. With those tough early years behind you, your professional needs and expectations have changed. Through CBABC, you can be recognized as a leader by speaking at professional development sessions, developing practice toolkits and resources, or writing for BarTalk

Speaking of professional development , CBABC has focused our attention on Indigenous cultural awareness through our Truth & Reconciliation Series each fall. Programs on equity, diversity, and inclusion support members to improve your toolbox to engage with clients and colleagues, and even adapt your employment setting! We focus on business and practice management in January through April, and throughout the year, we host practice-specific and regional conferences. All of these opportunities are offered for free or at a very low cost to members. Just another benefit for you!

legal education, access to justice, law reform, and justice system modernization. There is no end to the work that needs to be done.

Following the release of Agenda for Justice 2021, CBABC has seen many of our recommendations reflected in this spring legislative session. And there is much more going on behind the scenes. We enjoy a constructive relationship with government, the Law Society, and the courts. What our members say matters and CBABC provides the power of a collective to advance members’ goals and interests. You can be proud of being part of CBABC.

Every professional association has a member discount program and CBABC is no exception. MemberPerks by Venngo offers access to discounts from thousands of big brands and local favourites, including those available outside the Lower Mainland. You and your family are eligible to participate. And let’s not forget the CBA Advantage program with Audi Canada’s discounts of up to $5,500!

If working with others on a passion project is your jam, our 20 Committees and Working Groups provide that engagement. You might consider becoming your county or practice area’s representative to Provincial Council, or even join the Board. The exposure to the people and issues shaping the legal industry is unparalleled and you can influence the discussions about regulation,

I could go on, because there truly is a lot for every member at any stage of their professional path. Give me a call and we can be sure you get the most from your membership.

Kerry L. Simmons, QC ksimmons@cbabc.org

THE HONOURABLE JUDGE SHANNON KEYES

When I was a law student, I assumed that the natural progression of a legal career was to become a judge. I didn’t realize at the time that very few lawyers become judges. But I wanted to be a judge because I loved the law, and then the business of practising law took over. Fast forward 28 years, a lifetime later, and it happened to me.

I didn’t think about applying to the Bench until I was approached by some members of the judiciary asking if I would consider applying to the Provincial Court Bench. Eventually I applied. The hardest part of the application, aside from the interview, was having to write an essay about why I might be a good judge. I found it very awkward to write about myself. One of the strange things about the process is that an applicant isn’t told whether they have made it to the approved list or not. Some of my colleagues had long since forgotten about their application to the Bench and were quite surprised when they finally got the call.

Once a lawyer has accepted appointment to the Bench, the lawyer cannot appear before the court. For me the formal transition process from lawyer to judge was very speedy — I was appointed only five days or so after the call from the attorney general. For appointees in private practice, it typically takes much longer to close their practice.

A new judge begins a practical training program, including shadowing and being mentored by judges and attending courses, which is wonder fully helpful. Once the initial exhilaration was over, the new reality settles in. I had been accustomed to a warm, cozy, even raucous collegiality as a Crown counsel; by comparison, the halls of judges’ chambers were very quiet and lonely. One of the difficulties for many new judges is that the obligation to be and appear impartial may have a chilling effect on your relationships with friends who were also your colleagues. For me, almost all of my friends were lawyers, so that meant my social life disappeared along with my barristers robes. For a while I

rare for me to see any other judges. Whereas I had been used to sleeping in my own bed and eating with my family, I was now often sleeping in dingy cinder block hotel rooms and eating alone in the local pub, wondering if I would be seeing the guys enjoying “a few too many” at the table next to me in the prisoner’s box the next day.

Another thing that I did not realize as counsel is the solitary nature of judicial deliberation — and how exhausting it is to make decisions, day after day, which will change or govern peoples’ lives for years. As counsel, I would chat over my files with my colleagues; sometimes we worked as co-counsel. But as the judge, the buck literally stops with you. You may or may not have a colleague available to discuss the file with you, but in the end, you have to make a decision, and you have to make it alone.

I assumed that the natural progression of a legal career was to become a judge.

felt like transitioning to the Bench was like going into Purdah. I missed my friends.

In the north, where I was appointed, judges travel extensively to hold court in many small towns, and I was often away from home. Aside from my home chambers, it was

Eventually I adjusted to the new role. I am in my 9th year on the Bench now, and I am happy to tell you that it is still endlessly interesting and challenging — and my colleagues on the Bench are as warm, kind, and helpful as my colleagues at the Bar. Much as I enjoyed counsel work, I am happy being a judge.

The Honourable Judge Shannon Keyes, BC Provincial Court was first called to the Bar in 1986 after earning her bachelor of laws degree from the University of Victoria in 1985. She was an associate at Rubin-Haws and Associates, Barristers and Solicitors between 1987 and 1988, and began her own practice in 1991. She joined Cobbett and Cotton Barristers and Solicitors in September 1994 as an associate, and six years later joined the Criminal Justice Branch as Crown counsel, a position she has held until her appointment to the Bench.

ANDREW TANG

Change is inevitable but with it comes opportunities for both learning and growth. Although navigating the divide between being a law student to a fully practising junior lawyer can feel challenging and even overwhelming at times, there are fortunately some common law school experiences and skills that can be relied on to help ease this time of transition.

Although everyone’s experience at law school is different, two timetested strategies for success are being organized and developing effective time management skills. Fortunately, these foundational skills that are crucial to law school success are also entirely transferrable to the practice of law itself with organization and time management oftentimes being a junior lawyer’s life preserver in a sea of files. Therefore, those who took the time to hone these skills in law school will continue to reap their benefits in practice; and for those who did not, it is never too late to work on improving them.

Although the path through law school can sometimes feel solitary given that responsibility ultimately falls upon the individual student

to attend classes, complete assignments, and study for exams, most seek comfort and draw strength from spending time with others in study groups. It is no different in practice as, in most cases, articling students seek support from one another and junior lawyers work within a team that typically includes a senior lawyer, paralegal, and/ or legal administrative assistant. Each member of this team contributes their own skills, experience, and knowledge toward a common goal, with the only difference being that instead of A+ grade, the goal is an A+ resolution for the client.

important for junior lawyers to put their best foot forward at all times from day one and to always make that extra effort to be courteous and professional because a poor reputation is something that can be difficult, if not impossible, to change.

Everyone makes mistakes, with lawyers (from all walks of experience) being no exception. As a result, mistakes are bound to happen. Although these mistakes can feel devastating, what matters more is how we deal with and learn from them. Therefore, just like how it is sometimes best to simply accept a bad grade and move on, junior lawyers should recognize their limitations and remember that when things do not quite go their way, they should be kind to themselves and others while turning that regret into a learning opportunity and way to improve for the future.

The transition from backpack to briefcase can be a daunting one; however, the skills and lessons that are learned in law school provide an excellent foundation for success in practice.

Not unlike law school, the legal profession is a small and close-knit community. Therefore, upon beginning practice, a junior lawyer’s reputation can develop and spread very quickly, for better or worse. Therefore, it is

In summary, the transition from backpack to briefcase can be a daunting one; however, the skills and lessons that are learned in law school provide an excellent foundation for success in practice. Although it can be all too easy for a junior lawyer to doubt themselves amidst the heightened pressure and higher stakes of real-life practice, they should take comfort and confidence in knowing that the skills that they developed in law school can be relied upon in their transition to practice and beyond.

Andrew Tang is an associate at Harper Grey LLP practising in the areas of health, professional regulation, and securities law.

More than 200 lawyers across BC participated in CBABC’s roundtables in March and April to look at the regulation of lawyers and the role of the Law Society. Lawyers attending expressed a need for the Bencher Table to reflect diverse geographical regions because the practice of law is different based on geography, as well as other factors. Lawyers also supported stronger disciplinary measures taken against those members who repeatedly fail to comply with the Code of Conduct and the Legal Profession Act. There were mixed views on the issue of Benchers providing confidential advice to lawyers and the process of interviewing articling students. We thank all lawyers who shared feedback on ThoughtExchange (bit.ly/bt0622p9-1) to rank the Harry Cayton’s recommendations.

communities where there is a need to connect people to lawyers and court services, as the justice system continues to transition to a hybrid model using videoconferencing.

CBABC members made a submission (bit.ly/ bt0622p9-3) to the Law Society of BC and the government, emphasizing that the movement toward non-adversarial processes for family law disputes should not negatively impact those who are most vulnerable and require court intervention. The recommendations caution the government against a “one size fits all” approach to family law disputes, as family dynamics and culture often dictate the solutions that are most appropriate.

Following the Law Society’s release of the Cayton governance report, the BC Government announced plans (bit.ly/bt0622p9-2) to develop a legislative proposal for a single statute and regulator for lawyers, paralegals, notaries, and others providing legal services with a goal of modernizing the regulatory framework and improving the public’s access to legal services. CBABC will participate in the consultation to ensure that the independence of lawyers is maintained, regulation does not increase barriers to services by lawyers, and your views are known.

CBABC thanks all lawyers and law firms who donated dozens of computers, laptops, and smartphones during the A2J Tech Drive. With these donations, we can support Indigenous and remote

CBABC members also made a second submission (bit.ly/bt0622p9-4) to amend the Family Law Act as s. 203 currently creates a high threshold for appointing a lawyer to represent children. This proposed amendment offers greater opportunity for children to have their interests represented in family law disputes.

CBABC members responded to a call for consultation from the BC Supreme Court Civil and Family Rules Committee with a submission (bit.ly/bt0622p9-5) to modernize the rules of contempt. Given the considerable time and expense involved in making a contempt application, CBABC recommended greater transparency in the remedies available to litigants while also retaining the inherent jurisdiction of the court. Members also recommended efforts to simplify processes so that meeting the conditions for a finding of contempt did not exceed the efforts in securing the original order.

W. LAURENCE SCOTT, QC

Iam not old.

Yes, it’s been almost forty years since I applied to law school. Yes, I am over 60 years old. Yes, my hair is turning whiter. Yes, I keep getting mail from the Canadian Association of Retired Persons. Yes, I qualify for an assortment of senior discounts at restaurants and stores. But, I am not old.

Cicero claims with affected astonishment in his De Senectute, his discourse on old age: “What is this old age which all men desire to obtain, and yet which all men find fault with so soon as they have obtained it? They say it comes upon them quicker than they expected... .”

The truth is, I am getting older. And, it is happening quicker than I expected!

I am still going to my office every day. I am still actively practising family law. My family arbitration and mediation practices continue to thrive and grow. I still get excited about the prospect of advising new clients and assisting more families. I’m happy at work!

Getting older, and the accompanying wealth of knowledge and experience that comes with it, is something to be proud of.

There is no need to give up on a profession you love just because you reach a certain age. If your health permits and the work interests you and excites you, then you should keep doing it.

Older lawyers have much to contribute to our colleagues and to our communities. There are always new challenges to keep us active and engaged.

Lawyers can add value to society at large. Joining a law-related board or committee or getting involved in a community organization can help each of us grow personally and professionally.

At the same time, we have an opportunity to build intergenerational engagement between young lawyers and older lawyers. The beginning of a legal career is usually a bewildering and worrisome time. New lawyers need good mentors.

Let us not forget that our laws and legal policies resulted in disparities and inequalities between Indigenous peoples and our more expansive Canadian society. Older lawyers, who have borne witness to the history of those laws and legal policies, have a special responsibility to address these inequalities and work to build a mutually respectful relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

All of us are the guardians of a rich professional heritage. Each of us can play a key role in teaching a

Getting

older is to be embraced and celebrated, and the extra time so many of us have is a gift to be used meaningfully and wisely.

new generation of lawyers, sharing our values, and preserving our traditions while at the same time acknowledging the reconciliation of our Indigenous peoples and their role in our legal system.

Many years ago, I met a very old man. He was 99 years old and born in 1876. We chatted as we walked along the sandy seashore of a Scottish island in the Outer Hebrides and into the nearby town. He delighted in talking about the wonders of his lifetime. He didn’t dwell on difficulties and disappointments. He happily told me how he got up every morning and readied himself for the day. He put on a clean shirt and a tie, pulled on his old tweed jacket, and placed his flat cap carefully on his head and went for a long walk. “I dinnae want to miss anythin’,” he said in his authoritative Scottish brogue.

Part of the wisdom of my great uncle, and a retired judge, surfaced as a steady expression of gratitude for all those people who shaped his long life together with a determination to remain engaged in his community and an unending desire for personal enlightenment.

Like him, getting older is to be embraced and celebrated, and the extra time so many of us have is a gift to be used meaningfully and wisely.

ASHLEY SYER

“A

career path is rarely a path at all. A more interesting life is usually a more crooked, winding path of missteps, luck and vigorous work. It is almost always a clumsy balance between the things you try to make happen and the things that happen to you.”

— Tom Freston

Iwas one of those atypical teenagers who knew exactly what I wanted to do when I grew up. Somewhere in my Law 12 class, I figured it out. I wanted to be a lawyer.

In law school, the trial moot and clinical Law Students’ Legal Advice Program were my favourite parts. I wanted to do, not just read.

I knew a big firm wasn’t for me. While the beautiful shiny offices were enticing, I wanted a small firm where I could dig in, do meaningful and interesting work, and wear jeans and cool shoes to work.

I knew exactly what I wanted. Or at least I thought I did.

I got my summer articling job in an unconventional way: an offer on the spot while I was waiting tables. It was at the cool little firm I had dreamed about. I summered, articled, and became an associate. I was on my way to the career I’d always hoped for.

A few months after I was called to the Bar, my mom was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Seven months after that, so was my dad. My world turned upside down. My firm fired me. My parents died, seven months apart.

I joined another firm and tried to get back on track. There are a lot of reasons why that didn’t work out. After a certain point, I knew it would never work and so did the firm.

I applied for an inhouse job, and after months of interviews I was their second choice. When I asked why I didn’t get the job, I was told it was because I had “taken some time off” after I lost my parents, and because I had never been properly mentored. I’m not sure which answer surprised me more.

have colleagues around the office to bounce things off.

I eventually got my own space, with the hope of having a few other likeminded lawyers join me. I ended up falling in love with a space far too big, but took the leap and signed the lease.

A funny thing happened. Every person who has taken an office here, with a single exception, has been in the first year of starting their own solo practice or new partnership. At last count, about ten new practices have started here. Friends joked that I was running an accidental lawyer incubator.

The same week, I got a call from a law school classmate, offering me a spare office in a space he was going to share with two other sole practitioners. I never wanted to be a sole practitioner. It sounded terrifying. I had no clients, no clue how to run a practice, and no inclination to be my own boss. I also had no alternatives, so I figured I would give it a year and see what happened.

The transition was hard, but the good days were great, and the freedom was even better. It was a lot of learning, and I was grateful to

With the pandemic came more change. I found myself with four empty offices and needing a plan.

Out of the pandemic

The Lawyer Incubator was born. It is the first of its kind in Canada, though they do exist elsewhere. It gives new solos support, resources, and structured mentorship. It is exciting to be able to take some of what I have learned over the last eight years to help new sole practitioners set up a practice that they are proud of, with the hope that they will all become so successful they will eventually outgrow the space too.

The role of mentor is becoming one of my favourite of all the many hats I wear. As I transition my own practice away from litigation and into a mediation focus, I find myself more comfortable traveling this winding and sometimes unpredictable road.

Arjun is a member of the Lending/Insolvency Practice Group. He primarily works with banks, private lenders, real estate investors and developers, and corporate borrowers on a variety of matters, such as project financing, construction lending, and negotiating and dra ing security documents.

Arjun was called to the B.C. Bar in 2021.

ZSA is excited to announce a new partnership

ZSA Legal Recruitment has been actively assisting Diverse lawyers in elevating their career opportunities for some time now, but recognized that a strategic partnership would help accelerate and improve our results. It is for this reason that we are so enthusiastic about our new partnership with Blink Equity, a Diversity Equity and Inclusion (DEI) firm that specializes in helping organizations attract, retain, and advance the careers of the best Black Talent. Together, we seek to make concrete gains in the number of Black and Diverse lawyers being given the opportunity to not only showcase their skill sets in challenging and rewarding positions, but as importantly to grow and thrive in their new work environments.

For further information on our partnership, or to learn more about how we can assist your firm or legal department find and maintain Diverse legal talent, please contact:

RACE mrace@zsa.ca

TSHIAMALA Pako@blinkequity.ca zsa.ca and blinkequity.ca

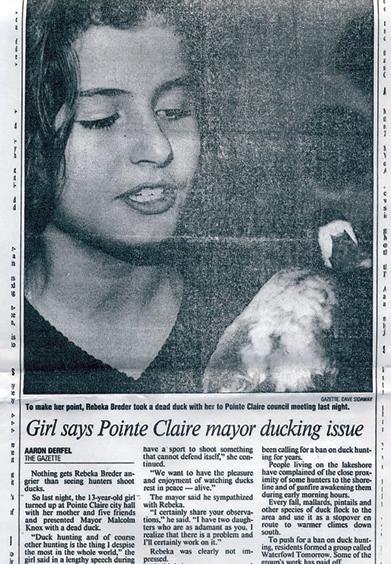

REBEKA BREDER

Isometimes (half) joke about how my career in animal law started when I was 13, growing up as an animal rights activist in Montreal.

The included picture is me, at 13, featured in the front section of the Montreal Gazette, holding a dead duck with a bullet wound in his chest. I was presenting an argument to various city counsel to ban duck hunting in the suburbs while gathering hundreds of signatures for this ban.

It’s no secret that I love animals, but “love” may be the wrong word. People have fought for the rights of women, African Americans, and human rights generally. Those advocates did not usually say they fought for these rights because they “love” women or African Americans. They fought for these rights because to deny these groups rights was simply wrong. Similarly, I have always argued for the rights and protection of animals. Not necessarily because I “love” animals (even though I do!), but because it is simply wrong to continue treating and using animals in a way that denies their inherent right to be free from harm caused by humans.

Defending animals is what drives me every day. In the early 2000s when I was in law school, I was told that lawyers should separate their personal passions from their clients’ cases to maintain an objective perspective. I was also told that I was idealistic and

that once I enter the “real world,” my passion for animal rights and welfare will be subdued by the realities of the legal profession. I have been told similar things since I was a little girl. I remember a time in high school, when I delivered a speech to my English class about the reasons it is wrong to wear fur coats. The next day, my

teacher walked into the classroom with her mink fur coat, which she had not done before, and she gave me a snarky look. She later told me I will grow out of “this phase.”

I am about to turn 45 years old. This is either an extremely long phase, or I have not grown out my burning, deep-to-my-core, passion to fight for and protect animals in any way I can. In fact, it is only getting stronger.

As a child, I organized protests for animal rights in the streets, and started student clubs that fought for animals and the environment. In the 1990s, when I was in my late teens, I realized that I wanted to go to law school to use my fighting skills in the courtroom to defend animals. I whole heartedly disagree with those professors and students who told me that I cannot be passionate about my legal work. As lawyers, having a passion can drive us to be more effective, while maintaining our objectivity and intelligence in the strategies we use to pursue our clients’ cases.

Having incorporated animal law in my practice at a respectable full-service downtown Vancouver law firm for over a decade, I decided to start my own law firm in December, 2016. I wanted to do so for a long time, but the timing never seemed right. Then, in the summer of 2016, my father, with whom I was extremely close, passed away. On his death bed, he encouraged me to finally start my own Animal Law firm. And with those words and the encouragement of my mother and husband, who have always been my biggest supporters, I did.

I am grateful to have founded the first exclusive animal law firm in Western Canada. All of this confirms that you can indeed pursue your passions in law and be successful. Success can be measured in diverse ways — such as making a career out of one’s lifelong passion. For me, this means fighting for animal rights in our judicial system.

Rebeka Breder, Breder Law Corporation. Twitter: @animallawcanada

Iwent to law school with the intention of working in the area of charities and not-forprofit law. I made that decision while working for a private foundation. I recognized that while I enjoyed being employed by charities, I wanted to develop technical expertise in order to bring greater value to the charitable sector. Many of the lawyers that I have met working in the charities and not-for-profit Bar report that they fell into the practice area, while others, like myself, have sought it out.

The Canadian non-profit and charitable sector accounted for 8.7% of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product in 2021, according to Imagine Canada (bit.ly/bt0622p13-p1). It’s a multibillion-dollar sector, and the scope of service and expertise required to meet the needs of Canadian nonprofits and charities is extensive. The sector includes numerous sub-sectors with diverse operational purposes, ranging from the provision of health care services and education, to land preservation and other environmental causes, artistic enterprises of all kinds, professional organizations, sporting, recreational and hobbyist groups, organizations working for the alleviation of poverty and “giving” ventures like public and private foundations. What ties this “sector” together is a shared regulatory environment and a mandate to serve the public benefit in some manner or other.

There may be more opportunities to take on values-driven work as a charities and not-for-profit lawyer than in

other areas of legal practice. In general, at least on the solicitor side, it also tends to be a fairly low-conflict practice area. Organizations and people within the sector are accustomed to working together to leverage their strengths in furtherance of a shared goal or common charitable purposes. Clients who are technically adverse interest frequently are working to serve the same goal, objects, or beneficiaries. As such, serving clients in this context requires the lawyer to look out for the client’s best interest, while also working proactively to assist the “other side.” This dynamic can require delicate handling of all parties.

and some boards may be more transient than in the for-profit context. As a result, clients may require more ongoing support. In my experience, this can be jarring for some lawyers who are accustomed to working on fast-paced corporate transactions or in contentious corporate litigation. But the extra time and attention can make the work more rewarding, if you have the patience for it.

There are, of course, challenges to acting for charities and non-profits.

... working for charities and non-profits helps those organizations to operate more effectively, and provides a stronger foundation for them to continue their missionbased work.

For example, the clients in the charities and not-for-profit sector are occasionally less sophisticated than the clients a transactional lawyer might encounter. They may be volunteers or overtaxed employees working off the side of their desk,

I find that serving charities and nonprofit clients offers considerable intellectual rigour and reward. The issues that charities and non-profits face touch on numerous areas of legal practice ranging from gifting and trusts to corporate governance, tax and regulatory compliance, insurance-related matters, human rights issues, contracts, and employment. Charities, in particular, operate within a highly regulated environment under the Income Tax Act (Canada), and there are many “grey” areas concerning how those regulations may be applied and enforced by the Charities Directorate.

As a lawyer serving a diverse sector with certain common attributes, there are opportunities to become an expert in the recurrent issues that affect clients, while also regularly encountering novel issues and developing inventive solutions. Beyond the intellectual pursuit, the reward is that working for charities and non-profits helps those organizations to operate more effectively, and provides a stronger foundation for them to continue their mission-based work. It might even help amplify the good in the world, and that is quite special indeed.

Krista Vaartnou. linkedin.com/in/kristavaartnou-95376773

THE HONOURABLE JUDGE ALEXANDER WOLF

Ihave had a lot of jobs. I was a stockboy in a Kmart; I’ve built windows in a factory. I have worked as a ditch digger, hotel desk clerk, bathroom janitor, machinist, assistant funeral director, sandwich maker, dishwasher, and the list goes on.

However, ever since I was 15, I dreamed of studying politics in Ottawa and going to Dalhousie Law School. The only reason I went to law school was to be an insurance litigator working for big Insurance companies. (I am still not sure why people roll their eyes when I tell them that). It should be noted that I grew up in an environment where nobody was cheering you on to finish high school, let alone go to law school.

In the mid 80s, I fled from my home province on my motorcycle. I was doing what any uneducated, longhaired rebel with a cause and two chips on his shoulder would do. I joined the Air Force. My theory was that I could learn skills that would allow me to work my way through university. I had already dropped out of acting school, unaware I could have asked for a student loan to help with tuition. I was broke. My shortlived military career was not a bad decision. I gained office skills and worked as a secretary, administrative assistant, legal researcher, and paralegal throughout my university years.

I did study politics in Ottawa — but fell in love with Anthropology — the study of culture. As time went on, I had a thirst for law and culture. Here comes the legal career whirlwind.

Why did I choose Dalhousie? It was not because Dalhousie is the best law school, although ask any Dal graduate which school is the best and they will not be shy on sharing their opinion. I chose Dal, because it was old. Somehow, I equated “old” with “good.”

One of my professors, who will remain nameless, (Mary Ellen TurpelLafonde), took me on as a bit of a special project. She sent me to

the Philippines to spend time in a Tribal Legal Aid Clinic where I was exposed to new ways of thinking about the law and had the time of my life. I was excited by the idea of being a lawyer in other countries and postponed my dream of becoming a Bay Street insurance litigator.

Next stop? I transitioned into a Human Rights Management Internship with the Aga Khan Foundation and off to New Delhi where I studied Indian Law at the New Delhi Jesuit Institute of Law. After receiving this “social activist” training, I worked with Jesuit lawyers in a city called Ahmedabad. There is no reason to know this small

Indian city — it only has a population of about eight million. We focused on cases called “atrocities.” Not just beatings, rapes, and murders, but crimes committed for cultural reasons. Often these crimes were committed on the relatively unheard of population of tribals or “Adivasis” (literally meaning “Indigenous” peoples). Their population is officially over 100 million — but thought to be much more.

Eventually, I came back to my dream and articled in a Toronto boutique insurance litigation firm. I loved the work but wanted to be in court more and joined the Federal Department of Justice (“DOJ”). For me, transitioning from India and parachuting into the role of a drug prosecutor in Toronto wasn’t filling my desire to mix law and culture. My journey with the DOJ took me from Toronto to the Yukon where I was in court every day and able to work with communities. I remember being the Crown in any number of lengthy, highly moving peacemaking circles. My time in the Yukon taught me a lot about Indigenous peoples and how mainstream institutions and communities can work together. After that I spent a little time on Residential school cases as a civil litigator and as managing lawyer to an Indigenous Poverty Legal Aid office in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver.

Alas, I yearned for more international legal stimulation. So, I did

what any responsible, well educated, career minded lawyer would do. I abandoned my legal career in Canada and I moved to Fiji. For the better part of two years, I worked as a legal officer with Fijian Legal Aid. I can tell you nothing stimulates the legal mind more than landing in a new country to dozens of manslaughter, murder, infanticide, and treason cases. I was at a slight legal disadvantage as the language of the accused in court was either Fijian or Fijian Hindi. There were no interpreters and my language skills, while always “flexible,” came nowhere near the concept of “fluent.”

I did have the amazing privilege of representing an Indigenous Fijian client charged with treason. The multiple month-long trial started on the first day with the tendering of the parliamentary hansard transcripts that captured things like, “Second masked gunman shoots bullets into ceiling of Parliament” or “First masked gunman: this is a coup.” One of these masked gunmen later heard the words “I hereby sentence you to death by hanging. May God have mercy on your soul.” These were perhaps the most memorable words I have ever heard in a court. Imagine it coming from an Australian judge, wearing a huge wig with a little piece of black cloth placed on top of the wig. In any event, tired of wearing wigs and hanging out on beautiful beaches, I came back to Vancouver and started up my private practice — and I loved it.

Just when I thought my career could not be going any better, in 2014, I transitioned to a job teaching with UBC Law School. I was part of a team

I always thought was a bit strange — until I got the job, and now I understand. They are like family. Everyone has said that when you are a judge you have to rely on your experiences. In other words, draw from your own life experiences when making decisions.

Every day, in court, I try to draw on my legal experiences as a poverty and international lawyer, Crown prosecutor and civil litigator, defence counsel and teacher. Each time I transitioned from one role to another, I felt like I was living a dream. To me, that is key, do what you love — and in life, what you love to do might even change over time. Career transitions are just a part of life’s journey.

that ran their Indigenous experiential learning clinic located right in the middle of the Vancouver Downtown Eastside. I had come full circle, having run from my home neighbourhood in the 80s. The clinic represents Indigenous clients while teaching keen upper year law students everything they want to know about lawyering.

Since accepting the appointment to be a judge with the British Columbia court, I have received lots of sound advice from my learned colleagues. We often refer to each other as “brother” or “sister,” which

When I started out my legal journey, nobody gave me a crystal ball. In my mind, I did not think I would need one — I had it all mapped out. Little did I know that my career would be such a long twisted legal trail.

My advice to anyone in law, would be “you don’t have a crystal ball, you cannot tell where you will be in twenty years — but imagine the possibilities.”

Top photo: Judge Wolf in a barristers wig when he was defence doing a jury trial in Fiji. Bottom photo: Judge Wolf doing a jury trial in the Yukon when he was Crown.

The Honourable Judge Wolf is a member of the Kwikwasut’inuxw Haxwa’mis First Nation from Gilford Island, which is located North of Vancouver Island. He is the resident Provincial Court Judge to the western coast of Vancouver Island, which includes the communities of Ucluelet and Tofino. His Indigenous name is “Abatzagee,” which means “worldly essence.”

IVA ERCEG

how to overcome them

You want to make a career transition, but you just can’t seem to take meaningful steps toward your career goals.

Even after soul-searching, clarifying your career values, and identifying potential leads, you keep putting off doing the work necessary to make the transition.

Whether you’re considering a transition to a new career entirely or just want to pivot within the same industry, making a career change can be daunting. Here are some psychological factors that could be getting in the way of your career aspirations.

Limiting beliefs about career transitions and changes are pervasive, including ideas that it is too early or too late to change, that a pay cut is inevitable, that you’ll be settling for less, that you’ll let others down, or that this means you failed in some respect.

We tend to be most susceptible to believing such myths in times of low confidence and when we try to ignore the confusing and overwhelming feelings that can accompany change. Instead, let yourself feel the full range of emotions, which may include fear, sadness, guilt, or excitement.

Be kind to yourself and allow those emotions to come. Avoidance of emotions can exacerbate feelings of anxiety, which, in turn, can make these myths seem more convincing.

If you find yourself allowing career change myths to take up precious mental real estate, ask yourself: where are these ideas coming from, and whose voices are asserting them? Make peace with the fact that your choices will not please everyone.

Fear of the unknown, fear of failure, and fear of change can keep people trapped in their current situations. Career transition can spur fears regarding job security, losing status or a sense of identity, self-doubt about one’s abilities, or even fears about disruption of a routine, among other things.

as separate from your work-identity, or maybe you need to acknowledge the skills and capabilities that have gotten you where you are today.

Instead of imagining all possible negative scenarios, visualize a successful transition. What does it look like?

Perhaps, most importantly, be motivated by your fears. Why should you fear staying in your current role? Maybe you’re unfulfilled, burnt-out, or longing for the next challenge — imagine not acting on those downsides, and let the fear of inaction inspire your next move.

It’s important to recognize that having worries around career transition is completely natural, and also to acknowledge that desire for stability can cause you to miss out on a more rewarding career.

Accepting that change typically can’t happen without at least some distress can lead to a more welcoming outlook; but also remember that worrying about change can cause more anxiety than the change itself!

Fear generally has a purpose, so listen to what it is alerting you to: maybe more research can provide clarity, maybe breaking down tasks into manageable chunks can bring calm, maybe you need to engage in self-reflection around your identity

If you have perfectionist tendencies, there’s also a good chance you engage in a healthy dose of procrastination. When it comes to career transitions, a perfectionist might think their transition must be perfect and they have to have everything planned out, continuously delaying taking actual steps.

To overcome the perfectionismprocrastination loop, try going for good enough. Don’t wait for conditions to be perfect to get started. Start small and do a bit at a time. Seek out mentors and arrange informational interviews, but don’t worry about having all the right contacts. Make an appointment with a career counsellor. Surround yourself with supportive friends and colleagues, as well as others considering a career change.

What is one step you could take today to advance your career goals?

Iva Erceg (she/her) is a former lawyer currently conducting research on career change as part of her Masters degree in Counselling Psychology at the University of British Columbia.

With COVID restrictions lifting, Section meetings are beginning the transition from virtual to our new hybrid model, where people can join in-person or by Zoom. No matter where you are, you can now host an in-person hub with your local colleagues to view the meeting. We know that Sections meetings are about content and connecting — and we’ll be working hard in 2022-23 to deliver both.

Between March and May, 80 Section meetings were held in BC. Here are a few highlights!

Young Lawyers - Lower Mainland invited Miriam Leung and Meaghan Loughry of the Counsel Network to share tips on writing the perfect resumé and mastering online interviews. They discussed formulating a stand-out resumé, the purpose of a deal sheet/ representative cases list, and how to prepare for an interview in person or virtually.

and John Logan, QC, at their 2nd annual in-person dinner. Over 100 attendees convened to hear from speakers about funny, important, or cherished events in their career.

Family Law - Vancouver Island hosted the alwaysentertaining John-Paul Boyd, QC to discuss the path to a career in family law, and the enhancement of day-to-day practice with authorship of family law resources for the public.

This joint meeting by the Civil Litigation – Vancouver and Vancouver International Arbitration Centre (VanIAC) adopted a hybrid format and hosted experienced arbitrators and practitioners for an afternoon panel discussion and cocktail reception. Ludmila B. Herbst, QC, William E. Knutson, QC, and Craig R. Chiasson shared tips on how to navigate and effectively advocate in domestic and international arbitrations. This was followed by a half-hour networking reception.

Civil Litigation - Vancouver hosted The Hon. Justice Jaqueline Hughes, The Hon. Justice Jasvinder S. (Bill) Basran, The Hon. Justice G. Bruce Butler, The Hon. Justice E.J. Adair (Ret’d)

General Practice, Solo & Small Firm invited Cynthia Mason and Monique Shebbeare to share their experience with practising in niche areas and tips on how to develop a specialized practice. The CBA unites you with corporate counsel and other lawyers across practice areas, throughout the country and beyond our borders. BC Members enjoy free and unlimited enrollment in over 60 Sections.

cbabc.org/RENEW22

STEPHEN P.E. CURRAN

When I meet new clients at my office in North Vancouver, I am often asked about my experience. When I reveal to them that before landing at my current law firm — a firm of around a dozen lawyers — I worked at a large, international law firm in New York City, followed by 11 years in Vancouver working with a national law firm, the question invariably posed by the client is: “What’s your billing rate?”

When other lawyers hear of my background, their typical response is: “What happened?”

The former question is easy to answer; the latter is a bit more complicated.

One year after moving from a downtown Vancouver law firm to my “local” perch in Central Lonsdale, it is clear to me that the pandemic was a “circuit breaker” event in my career. I started practising law in New York City, where as a young lawyer I was immersed in a busy private equity transactions practice, during the frothy leveraged buy-out environment preceding the 2008 financial crisis. When I relocated to Vancouver in 2010, in part motivated by “lifestyle” considerations, I quickly learned that a transactional practice on either side of the 49th parallel promises a heavy workload and the regular application of crisismanagement skills.

When the pandemic turned life upside down, the demands of my practice remained largely unabated. When people at the firm were first instructed to work from home, however, none of us knew what to expect. Would our work grind to a halt? How long could we continue to effectively practise law remotely? Very few were able to predict that, for many of us, the demands on our time would only accelerate.

While the demand for my legal services has continued apace, the manner in which I deliver those services has changed significantly. Many of these changes have been documented and described in detail by others in this publication and elsewhere, and include reflections

persisted, I was able to more fully commit to family engagements with increased regularity.

In addition to my newfound balance in daily activities, I also found that I was able to more clearly reflect on my career and what was important to me in my practice. Having a bit of distance from my usual routine (which for me included 10+ hours per day in the office), I could soberly assess my development as a lawyer, and contemplate what I still wanted to accomplish professionally. The ultimate product of this assessment: I wanted to try something different. I wanted to experience private practice from a more intimate platform; I wanted to learn more about the “business” of law; and I wanted to find a way to become more involved in my local community of North Vancouver.

I wanted to try something different. I wanted to experience private practice from a more intimate platform.

on the increased use of videoconferencing, virtual transactions, and an augmented reliance on the “cloud”. In my case, however, working from home also afforded me an ability to be more present among friends and family on a daily basis. Although important client deadlines

The sum of these reflections convinced me to take a step back from a great national firm, where I worked with very talented people, and set up practice within a 10-minute walk from my home. Through my career transition, I have fundamentally changed my approach to the practice of law, and I have gained a deeper insight into the aspects of my practice that I value the most. I was able to count on a strong network of friends and family when I deliberated my next steps, but in many ways I would not have taken the time to think about making a change unless the pandemic, and the ensuing disruption to our daily lives, had given me space to think and reflect.

Stephen P.E. Curran is a partner with Lakes, Whyte LLP.

If you have been considering moving away from the print to the online version of CLEBC’s publications, now is the time to make the change! As with publishers around the world, CLEBC is facing increasing challenges with securing quality paper for our print publications, significant cost increases, as well as delays in completing the printing process. We are becoming less certain when we can deliver the print publication to you.

CLEBC is pleased to offer all of our publications in an online format with many features not available in the print and with none of the uncertainty of delay in receiving your publication in the mail. CLEBC online publications allow you to:

Access your CLEBC publications anytime, anywhere, from your smartphone, tablet, or computer.

Run a search query within a specific publication or across all of your CLEBC publications.

Link directly to case law and legislation and websites referred to in the publications.

Download all of the forms and precedents included in the publications in a single download.

Expand the reading pane and hide the navigation pane for an improved reading experience.

There is no better time to take your CLEBC publications library online and help us reduce our carbon footprint.

For more details, visit: cle.bc.ca online.

SYBILA K. VALDIVIESO

The In-House Bar has experienced unprecedented change; a quiet yet impactful shift in the last few years with more lawyers leaving private practice for In-House practice. Organizations began developing internal legal teams and, in many sectors, legal departments now employ more lawyers who perform legal work formerly done by external lawyers. This has strengthened organizational capacity, reduced legal costs, and led to better legal advice from internal colleagues who understand the business. These are benefits of the unique role of In-House Counsel who work as business advisors and ensure decisions are legally and ethically sound.

Naturally, at some point, In-House Counsel may consider transitioning to a non-legal role, such as to chief operating officer, chief executive officer, or to a hybrid role aligned with legal, such as chief compliance officer, chief procurement officer, or corporate secretary. When considering a transition, evaluating one’s skills as business advisor is key because that role provides the understanding of what the organization does, what needs to be protected, what future risks may arise, and how to provide alternative solutions when needed. The fact that In-House Counsel immerse themselves in the business of an organization, means they have the ideal skillset to make such a transition.

The following preparation and planning aspects should be considered when contemplating a transition to more of a business role:

Seek opportunities to engage in projects beyond legal areas and build strong relationships within the organization from a business first perspective — this shows that you are willing and ready to transition.

Think about why you want to transition: what business aspects interest you? For many lawyers, it is the legal aspect of their work that is most fulfilling, so be clear on what makes a non-legal or hybrid role attractive. Impact, new challenges, career change, or compensation are some of the key attractions.

The In-House Bar has experienced unprecedented change; a quiet yet impactful shift in the last few years with more lawyers leaving private practice for In-House practice.

Will you transition to a non-legal or hybrid role at the same organization where you are In-House Counsel? Consider conflicts that may arise, and clarify that you are no longer the lawyer for the organization. A consultation with the In-House legal team would be important, and if concerns remain, consider moving to a different organization.

Evaluate your skills, including business skills, for the role you want, such as: financial planning; integrated risk management; people management; etc .

and develop them. To gain skills, consider a secondment in a similar role or join a board.

Also assess the risk orientation of the role you want in relation to your own approach to risk. Many non-legal roles require willingness to take risk for the sake of a business outcome, whereas legal roles are often about reducing risk.

Remember that technology is a business skill: COVID-19 has accelerated technology use and expectations and there is more integration of technology into broader business solutions so develop your technology skills to stay current and get ahead of the curve.

Seek guidance from those you trust, including the Canadian Corporate Counsel Association (“CCCA”) and members of the Bar. Speak with colleagues who transitioned to nonlegal or hybrid roles — there is much value in the voice of experience.

If you transition to a non-legal role, the door stays open to return to the practice of law, however the longer you are outside law, the less likely it is you will return. You will also need to let go of the legal analysis, so self-assess and determine if a hybrid role would be more fulfilling for you.

Finally, remember in 2022 careers are flexible. If you want to transition, plan and prepare, seek support and ignore rigid views about the limits of In-House Counsel — the facts speak for themselves, InHouse Counsel careers today have unlimited possibilities!

Sybila is Executive Director and Senior Legal Counsel with the Provincial Health Services Authority. She sits on the executive committee of the CCCA BC and wishes to thank fellow executive colleagues David Avren and Justin Wood for their contribution to this article.

SARA FORTE AND SARAH EWART

What Not Your Average Law Job has discovered about finding happiness in your career

“You’ll never find 100 happy Canadian lawyers.” When we first talked to people about our Not Your Average Law Job™ project, we were met with skepticism. The project kicked-off with a single profile on a happy Canadian lawyer, who took a non-traditional path. Now, less than a year later, the project is on track to hit 100 happy lawyer profiles by the summer of 2022 and won’t stop there. There are far more than 100 happy Canadian lawyers.

When we launched this grass-roots project, we saw it as a tool to inspire lawyers unhappy in their careers to explore other paths within the profession before leaving law. As it unfolded, we realized that the project had become an unintended research project, and we had become accidental experts in lawyer happiness.

Talking to happy lawyers, clear themes of what makes them happy in their careers have emerged. They have all had unique paths to happiness in law, but they share some things in common. We are excited to share a few.

Finding the perfect job is often the result of reflection and planning, not luck. Happy lawyers take time to figure out what their needs outside of the office are and then find work that makes that lifestyle possible. If working from home is

important to you, do not accept work that requires you to be in an office. If you know that you only want to practise in one area of law, do not apply for jobs that would include work in several areas.

Flexibility can mean many things. For some, the flexibility to be able to watch their child’s school performance at 3 p.m. on a Wednesday afternoon is important. Others are at their best working from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. and prefer the flexibility to work outside the standard office hours. Some Canadian lawyers have homes and families across the globe and appreciate the flexibility to be able to work in another country for a few months of the year. Whatever flexibility means to you, we have found that lawyers are happier working on their own schedule.

others rely on a close-knit circle of friends outside of the profession. It does not matter who is on your side, the important thing is to keep a team behind you, rooting for your success.

4. HAPPY LAWYERS

Life is too short to hate your job. There are a lot of different career options out there and all it might take for you to land your perfect role is sending an application in for a job you think is out of your league or sending a message on LinkedIn to a lawyer whose career you admire. Putting yourself out there and taking a risk can be scary, but it will lead to fulfillment in your career.

A happy career is not built alone. Happy lawyers acknowledge that they could not have developed the practice that they have without the love and support of co-workers, mentors, family, and friends. Some lawyers join online communities and

Got a work-related problem that’s slowing you down? There’s an app for that! Happy lawyers do not cling to tradition — if it no longer serves them — and are open to try new things that help free up their time to help their clients and do other things they enjoy. Happy founders and solo practitioners run their practices in innovative ways by introducing things like alternatives to traditional billing models.

SHARON SUTHERLAND

For many lawyers, a career transition to mediation has appeal. Motivations vary, but may include interest in a more collaborative (less adversarial) role than one’s current position, perceived suitability of the practice to gradual retirement, a way of diversifying practice to keep it fresh, a better match with one’s values, and a desire to support people in more flexible problem-solving approaches.

Whatever the motivation, many lawyers form their image of mediation practice while attending mediations as counsel. Apart from commonly limiting observation to one kind of mediation, this is a bit like watching law shows on TV to find out what lawyers do day-to-day: you only see the parts that make good TV.

Here are a few additional observations for lawyers considering a transition to mediation.

Marketing is a much bigger part of mediation practice than most new mediators realize. Often people moving into mediation are passionate about mediating but are uncomfortable with or have very little interest in marketing. Experienced mediators describe spending 20% or more of their time in marketing (include presentations, writing, attending events and more). Be prepared for this aspect of the work.

There is paperwork! While a mediation practice may generate substantially less “paper”-work than many legal practices, ... someone has to do the administrative work. If you are building a mediation

practice while still maintaining a legal practice, you may be able to pass many administrative tasks to an existing assistant. If that’s not your transition plan, give thought to time needed for scheduling, creating, and regularly updating standard communications and agreements, invoicing, financial management, and all of the other aspects of running a business. Talk to other mediators about how they manage these tasks — many have found ways to make this more manageable.

The practice can be lonely and isolating. If you’re moving from a firm, you may miss the ease with which one can reach out to colleagues to talk through issues. This isn’t a necessary aspect of mediation practice, but for many ensuring one has a network of colleagues to connect with requires conscious effort. Think about building networks with other mediators from the very outset. Join communities of practice, attend new mediator group meetings, and ensure that you have collegial supports.

your current legal connections. Think about co-mediating with someone with a very different background: your legal skills and knowledge bring something to the mix, and you may learn much more about trauma-informed practice, engaging external resources, community-based models, and more. The collaboration can help you find and follow your passion in mediation — and can add tools to your toolbox.

Similarly, consider broadening your professional development choices beyond just mediation training. Conflict resolution is a highly interdisciplinary field. Explore broader learning options such as equity, diversity and inclusion, neuroscience, applied improvisation, and so many more.

More so now than ever, mediation can occur on any platform. You may be attracted to in-person mediation, but explore the multitude of approaches that make use of video, audio, and text-based models. Yes, even avatar mediation is an option. Where do you communicate best? You may be surprised by the opportunities.

There are many models of mediation, and many outstanding mediators who are not lawyers. Learn about multiple approaches to mediation and build your own style. You can (and should) learn from mediators with backgrounds in counselling, social work, and financial planning — and from first career mediators straight out of school. Build networks beyond

For some lawyers, mediation offers a chance to do more pro bono work than might be possible in their existing practice. There are opportunities to help within your own communities, whether they be local schools, community sports groups, faith-based communities, clubs, etc. Conflict is everywhere, and you may find that you are able to give back in new ways that align with your interests and values.

Sharon Sutherland is Director of Strategic Innovation at Mediate BC and has been mediating since her Call to the Bar. Twitter: @ssuth — LinkedIn: sharonsutherland

KARMEN MASSON

Have you ever thought about changing your area of practice or even leaving the profession altogether? Rates of attrition from private practice and from the practice of law are worrying.

Lacking motivation, a sense of fulfillment, or a semblance of work/life balance, you may be doubting that you are in the right place.

I know how it feels to be uncertain, overwhelmed, and at times, lost. I have burned out and believed that the only solution was to leave practice... which I did. I returned, but not out of a sense of clarity, but a sense of fear of losing my status as a practising lawyer — a status that I, like you, had spent years pursuing. The search for my “right place” in law continued and eventually I began to discover what was important and meaningful to me.

There are five key lessons I know now that I wish I would have known when I was making my decision whether to love or leave law:

If you are feeling tired or overwhelmed with any aspect of your work or life, take care of yourself first. You may need to pause to be able to see, and eventually address, the issues you are facing. Scheduling time for self-care may help, or you may wish to seek additional supports.

If you have doubts about your work or career path, do not push aside

your thoughts, feelings, and questions. Listen to yourself, and be thoughtful and considerate of your own needs. Journaling about your challenges and their impact can be a helpful step toward taking charge of the issues.

Thinking about the following questions can help lead to insights into what fulfillment, meaning, or balance means to you:

What is most important to you in your work? What are your non-negotiable work values?

What are your top strengths (i.e., the things you do naturally and did not have to learn)? How much are these strengths being utilized in your work?

it would be perfectly normal for worries disguised as good questions to come up:

What if I make less money?

Will they think I could not manage things?

What if I fail?

If you are feeling blocked, defining or redefining what success means to you at this stage of your career and life can help to clarify your goals and chart a course forward.

Another common block that causes worry and indecision are assumptions about what others might be thinking or feeling. Do not assume that others do not care or will not support you. Rather than expecting negative responses, ask yourself:

What do I risk by holding my assumptions as truths?

How can I learn more about others’ thoughts or ideas?

What opportunities or supports might you need?

The answers may or may not come easily. By being curious and pursuing your introspection with self-respect and integrity, the answers should present themselves. Talking about these questions with someone you trust can also help to deepen your reflection and shift perspective.

While exploring what is most important and meaningful to you,

When it comes to making decisions about whether to stay or make a change, there are no guarantees that you will get it right the first time. By applying these lessons, and others that you may pick up along the way, you will learn much about yourself and how you can define and create a practice and career that are right for you.

Karmen Masson is a lawyer coach who supports lawyers and leaders in law. Your Best Practice

Chelsea Dubeau

ESTATE LITIGATION CED@HDAS.COM

Oliver C. Hanson

Ellen Hong

ESTATE LITIGATION ESH@HDAS.COM

Karen Powar

EMPLOYMENT LAW PERSONAL INJURY KKP@HDAS.COM

FAMILY LAW CIVIL LITIGATION GSS@HDAS.COM

Gurminder Sandhu

James Woods

ESTATE PLANNING CORPORATE / COMMERCIAL JGW@HDAS.COM

Hamilton Duncan is the Fraser Valley’s preeminent business and litigation law firm. With an office in Surrey, and now in Vancouver, our recent growth is unprecedented in our 63-year history.

Reflective of that growth is our admission of seven new partners. Each has demonstrated the same drive, skill and unwavering commitment to exceptional client service that has made our firm what it is today. Our pride in them is paralleled only by our enthusiasm about our future.

Learn more about them and us at hdas.com

We make it simple to succeed.

JANIENE CHAND

You’ve made the decision to transition your career, now what…

First up, ask yourself these two powerful questions:

1. Do you know what it is about the current career that does not work for you?

2. Do you know what career will work for you and why?

When you make the choice to transition your career, you are choosing to make a change. A change that comes with many mixed emotions. A change that feels exciting but scary at the same time. A change you know you need without potentially knowing what you need or how you will meet your needs.

Career transitions are often made by individuals when feelings of fulfillment and satisfaction are missing from their current career. This is why self-awareness and self-discovery are so important. Without knowing yourself and what you need or want, it is difficult to make changes that will be fulfilling and meaningful.

You need to understand what it is about your current career that does not align with you so that you can make empowering choices and take actions that are in alignment.

So how do you achieve alignment?

To have alignment, you need to know and understand your personal core values. Identifying your personal core values is the first step.

Once you know them you are able to explore what values you prioritize. And from there you can identify how you can take actions and make choices that are in alignment with your values.

This includes asking yourself if any of the values you believe to be yours are actually internalized through others around you, such as your parents, and what each of your values mean to you. For instance, work-life balance can be an important value but what it looks like to you may differ from what it looks like for someone else.

you can hold them firmly and recognize when they are being crossed. Ask yourself what your boundaries are in relation to your career, and whether or not they are healthy boundaries. For instance, being unable to decline work due to the thinking that it will leave a negative impression on your colleagues, even if it requires you to work overtime which is misaligned with your values, means you have unhealthy boundaries. Knowing and understanding your boundaries helps build confidence.

Once you go through this process of self-discovery, you will have more self-awareness. You will have clarity around your desired vision for your career. A vision that makes you feel empowered and aligns with your authentic self.

Let’s bring empowerment into this mix.

In order to feel empowered, you need to identify and work through your limiting beliefs. Ask yourself if you have any beliefs that are not necessarily true, beliefs that are limiting.

For instance, do you believe that things always go wrong in your life?

Is this actually true, or are you just telling yourself this story?

It is not until you realize that you are telling yourself these stories, that you can actually begin reframing your mindset and building confidence in yourself.

Additionally, you must know and understand your boundaries so that

It is important to take the time for a deep dive, to reflect on your wants and needs. To ensure that your career transition is a step toward the desired vision you have for your career.

By having clarity and awareness around yourself and your vision, you can confidently make the change you desire. You can proceed with confidence as you go through a career transition.

So instead of wondering whether or not you have made the right decision(s), you are confidently making choices that feel aligned and empowering.

Janiene Chand is a former lawyer, certified professional coach, and founder of Janiene Chand Coaching, a life and career coaching business. linkedin.com/ in/janiene-chand-43b52b164

ALLISON WOLF

Jenny feels stuck. At three years of practice, she values her warm relationships with colleagues at her firm. There’s just one problem. It’s a boutique litigation practice, and Jenny is learning that she does not like litigation.

Mark also feels stuck. He’s at a firm with a good reputation and highquality work. He likes the practice area, but the senior partner he works for is difficult and prone to dishing sarcastic put-downs and angry tirades. The other partners know this is a problem, but no one steps in to help.

Jenny and Mark are not alone. Most lawyers do not land the perfect job right out of law school.

Many lawyers with flourishing careers have made at least one career transition, if not more.

There are three essential steps you can take to navigate toward flourishing.

Suffering and misery carry important messages — investigate. Seek out the source. What is causing the energy drain? These feelings could be due to misalignment or overwork.

Common misalignments are too many unpleasant clients. Work that is, for the most part, unmotivating and depleting. A toxic work environment. Or a sense of work conflicting with your core values. Sometimes, work that once aligned no longer does. As a more senior lawyer, you

may no longer be engaged by legal work that has become mundane.