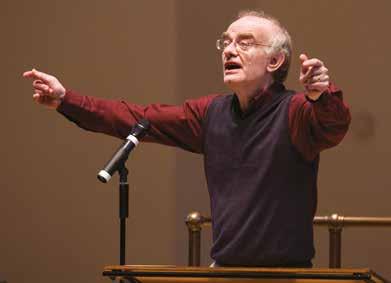

SIR JOHN RUTTER

We raise a toast to the great British choral composer as he turns 80

How the streaming of services online became a global success

We explore his enigmatic life and eloquent music THE MAGAZINE OF CATHEDRAL MUSIC TRUST

GIBBONS AT 400

VIRTUAL CATHEDRALS SINGING OUT

How St Paul’s Cathedral has revitalised its education programme

A Cathedral Music Trust membership is the perfect gift for a choral and organ music lover.

Give someone special the chance to delve deeper into the heart of cathedral music.

Buy now at: www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/friends or for further information please email katy.ashman@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

From just £30 a year

CATHEDRAL MUSIC TRUST

Royal Patron

HRH The Duchess of Gloucester

President

Harry Christophers CBE

Ambassadors

Alexander Armstrong, Anna Lapwood MBE

Board of Trustees

Jonathan Macdonald (Chair), James Gurling OBE, David Hill MBE, Sue Hind Woodward, Stuart Laing, James Lancelot, Giverny McAndry, Heather Morgan, James Mustard, Isobel Pinder, Gavin Ralston, Simon Toyne CEO

Jonathan Mayes

Programmes Director

Cathy Dew

Programmes Manager

Anna Elliss

Development Director

Leila Alexander

Development Officer

Katy Ashman

Volunteer & Events Coordinator

Hannah Capstick

Digital & Communications Manager

Laura Cottrell

Director of Finance & Resources

Dan Bishop

Finance Officer

Amanda Welsh

Cathedral Music Trust is extremely grateful to our team of volunteers across the UK who give many hours of their time each year to support the work we do.

Cathedral Music Trust

27 Old Gloucester Street London WC1N 3AX info@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk 020 3151 6096 (office hours) www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

Registered Charity Number 1187769

CathedralMusicTrust @_cathedralmusic @cathedralmusictrust

CathedralMusicTrust

Cathedral Music Trust

CATHEDRAL MUSIC MAGAZINE

Editor Rebecca Franks editor@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

Designer

Louise Wood

Production Manager Kyri Apostolou

Cathedral Music is published for Cathedral Music Trust by Mark Allen Group twice a year, in May and November. Autumn 2025

WFROM THE EDITOR

elcome to your autumn issue of Cathedral Music, and my first as the magazine’s editor. It’s a joy to be stepping into this role, and after a wonderful summer meeting the team at Cathedral Music Trust, I know it’s going to be easy to fill this magazine with engaging features, interviews and news, bringing you all the latest insights into the cathedral music world.

I distinctly remember the first time I fell in love with a piece of choral music. It was at my school’s carol service in a local church, and a small group of singers were rehearsing John Rutter’s The Lord bless you and keep you. I was so moved by the seemingly effortless simplicity and purity of this piece, and I still am today. I’m far from alone in being touched by Sir John’s music, as you’ll read in our wonderful tribute to him, to mark his 80th birthday, by those who know his craft best (p42).

Based in Cambridge, Rutter follows in a long line of distinguished composers who have shaped the English choral tradition, including Orlando Gibbons. Four hundred years after Gibbons’s death, details of his life remain hard to pin down, but his music speaks for itself, as we find out in ‘The Master Storyteller’ (p38).

The theme of traditions, and how they might evolve, is threaded through several other articles in this issue. It’s been fascinating to find out more about why choirs decide to recruit choristers from a variety of schools rather than the single choir-school model (p28). And if you can’t always get to a cathedral near you, think about watching a streamed service online (p31), an intriguing development that’s come out of the pandemic.

As I write this letter, the nights are drawing in and autumn is on its way, and it will soon be the busy time of Advent and Christmas. I couldn’t let the season pass without celebrating it in print, and I hope you enjoy our perusal of the history of Christmas carols (p45) as well as a round-up of the unmissable Christmas albums (p62).

Rebecca Franks, Editor of Cathedral Music

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Cathedral Music Trust.

Advertisements are printed in good faith, and their inclusion does not imply endorsement by the Trust; all communications regarding advertising should be addressed to info@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk.

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used; we apologise for any mistakes we have made. The Editor will be glad to correct any omissions.

Corrections from Cathedral Music, Spring 2025: p27. We mistakenly claimed that Leeds Cathedral Choir offers opportunities to collaborate with the singer-songwriter Gabrielle. We would like to correct this and put the record straight. In fact, the choir works with Paul McCreesh’s Gabrieli ensemble. Please accept our apologies, on behalf on Mark Allen Group, for these errors.

Front cover: Sir John Rutter (Photo: Nick Rutter) Back cover: St John’s College, Cambridge (Photo: Keith Heppell)

28 Multi-school cathedral choirs

Andrew Stewart finds out why some cathedrals prefer to recruit choristers from a variety of local schools rather than from dedicated choir schools

Partnerships at St Paul’s

Cathy Dew reveals how the iconic London cathedral has revitalised its educational outreach programmes over the last two years

31 The virtual cathedral Clare Stevens discovers why the streaming of services online has flourished in Britain’s cathedrals since the pandemic

38 The master storyteller

To mark the 400th anniversary of Orlando Gibbons, Jeremy Summerly explores the composer’s enigmatic life and eloquent music

Graham Westley Lacdao

Adobe Stock/Nicolae Gherasim

Matt Wilson Nick Rutter; Chester Cathedral

42 Celebrating Sir John Rutter

We speak to leading performers, composers and clergy about what makes the popular British composer’s choral music so special

45 A history of Christmas carols

Carols might be a staple of Christmas today, but that hasn’t always been the case. We tell the colourful story of these festive favourites

Rebecca Franks welcomes you to this new issue

The latest developments and stories from across the world of church and cathedral music 19

People & Places

Who is moving and to where? We congratulate those taking on exciting new roles

Events

Join a Cathedral Music Trust at a gathering near you 22 Award

Reflections

2024 recipients discuss the beneficial impact of Cathedral Music Trust’s vital support 50

Reviews

Recent releases of choral and organ music reviewed, plus a round-up of the latest scores, and a Christmas album special 66

Cathedral Music Trust Future Leader David Whitworth on the joys and benefits of a life involved with choral music

Adobe Stock

Nick Rutter

NEWS & PREVIEWS

UNESCO RECOGNITION CAMPAIGN FOR ANGLICAN CHORAL MUSIC

Anglican Choral Music is a remarkable cultural treasure.

This autumn, Cathedral Music Trust is calling for its inclusion in the UK’s nominations for UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage inventory, overseen by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). For centuries, the sound of Evensong has shaped our cathedrals, chapels and communities, creating a shared experience of music, language and spirituality. Together, we sustain more than music; we nurture a legacy. Your support for the Trust and local choral foundations ensures that choristers and organists receive life-changing musical training and opportunities to cultivate artistic skills, confidence, discipline and a sense of belonging.

Our collective backing ensures that this example of living heritage reaches millions worldwide through broadcasts, concerts and recordings. However, in a fast-changing world, the tradition faces real challenges.

The Trust’s advocacy efforts are multifaceted, focusing on both financial support and strategic initiatives to ensure the vitality of cathedral music and the preservation of daily sung worship. By actively campaigning for UNESCO recognition, we aim to raise the profile of this living cultural heritage, champion high quality music education, and secure a future where Anglican Choral Music remains a vital part of our national legacy.

At this stage Cathedral Music Trust is leading the campaign by creating a

forum of support across choral and heritage sectors, inviting testimonies and examples demonstrating the living nature and community impact of choral music, and invites organisations and individuals to endorse the initiative to raise awareness within their own networks.

Autumn updates will be shared about progress on the Trust’s website and across social media. Securing UNESCO status would mark an important milestone, but not an endpoint, in a wider effort to ensure that Anglican Choral Music continues to inspire, educate and transform lives through this important musical pratice for generations to come. Visit cathedralmusictrust.org.uk to get involved

CATHEDRAL MUSIC TRUST ANNOUNCES LATEST AWARDS

Cathedral Music Trust has announced its latest round of awards through the Cathedral Music Support Programme, totalling £470,000 and supporting music in 27 Anglican and Roman Catholic cathedrals and churches in the UK.

Now, as its renewed main awards scheme enters its second year, the Cathedral Music Support Programme

Cathedral music scholarship scheme

The Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick has announced a new choral scholarship programme for talented young choristers in Warwick and the surrounding area, which will begin in September 2026.

The King Henry VIII Choral Programme, which is a partnership between Warwick Schools Foundation and The Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick, has been made possible by The King Henry VIII Endowed Trust, Warwick.

The programme will enable young choristers to sing in the choir of St Mary’s while also accessing the musical opportunities available as part of being a pupil at Warwick Schools Foundation, which comprises five schools, four in Warwick and one in Royal

(CMSP) is awarding 20 new recipients, as well as continuing to support 20 choral foundations which were awarded multi-year grants in 2024.

The CMSP builds partnerships with cathedrals and other choral foundations across the UK, developing work that shares Cathedral Music Trust’s objectives in

three areas: pathways to music; training and development; and supporting the workforce. This year, financial support provided by the Edington Festival contributes to the award made to Chester Cathedral.

Cathedral Music Trust CEO Jonathan Mayes says: ‘The invaluable work of our cathedral and church musicians enriches the lives of both participants and the communities in which they operate. At a time when the sector faces numerous financial challenges, this much-needed investment demonstrates the Trust’s dedication to securing the future of our world-renowned tradition.’

The Church Choir Award, run in partnership with the Royal School of Church Music, also awarded £30,000 of funding to seven church choirs to enhance their work through innovative and exciting projects.

For details of all the recipients, visit cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

Leamington Spa. Boys and girls across the Foundation from Year 3 upwards will be eligible to be assessed for the Award.

Oliver Hancock, Director of Music at St Mary’s Church, said: ‘The newly launched scholarship is an exciting new venture between St Mary’s Church and Warwick Schools Foundation. We’re hoping to

continue to build on a really solid relationship, and give more and more children a doorway into this fantastic world of choral singing.’

For more information regarding the scholarship programme, including the application process and eligibility criteria, visit warwickschoolsfoundation.co.uk/ khviii-choral-award

IN BRIEF…

The National Youth Choir of Northern Ireland has announced its closure after 26 years, after losing its Arts Council funding, which totalled around £60,000 a year.

A petition has been launched calling for the withdrawal of funding to be reversed, noting that the decision is ‘not only short-sighted, it is an act of cultural vandalism’ and that its loss is a ‘deliberate dismantling of a vital pathway for young people in Northern Ireland to engage in transformative artistic experiences.’

In an article for the Irish Times, the Arts Council of Northern Ireland said the decision was not due to funding pressures but instead ‘based on the ability of the organisation to meet the programme’s criteria’. They say that ‘provision of high-quality youth choral training and development in Northern Ireland remains a priority for the Arts Council’.

The King’s Birthday Honours List 2025, announced in June, included several figures from the UK’s choral and cathedral music community. Michael Downes, Director of Music at the University of St Andrews, received an OBE for services to music, while James Manwaring, Director of Music at Windsor Boys’ School, was awarded an MBE.

The Reverend Richard Coles’s cosy crime novel Murder Before Evensong has been made into a TV series, due to be aired this autumn on Channel 5. It stars actor Matthew Lewis as Daniel Clement, the Rector of Champton, who finds himself turning amateur sleuth.

OWAIN PARK APPOINTED CHIEF CONDUCTOR OF THE BBC SINGERS

Owain Park has been appointed Chief Conductor of the BBC Singers, beginning in autumn 2026. He will succeed Sofi Jeannin, who has led the group since 2018. Park has been Principal Guest Conductor of the group since 2022.

Over the last year, Park conducted the group in several performances. In February 2024, he directed a concert celebrating the music of distinguished composer Dame Judith Weir and in October 2024, he conducted the BBC Singers as part of their Centenary concert at the Barbican. The previous year the renowned choir had been threatened with closure, but after protests and public outcry the

decision to disband was scrapped and the group was saved.

Park says: ‘I’m absolutely thrilled to be stepping into the role of Chief Conductor of the BBC Singers – it’s both a dream and an honour. With their rich history and spirit of innovation, the Singers represent so much of what excites me about music-making.’ Jonathan Manners, Director of the BBC Singers, says: ‘Everyone involved with the BBC Singers is thrilled that Owain Park will be the group’s Chief Conductor. He is perfectly placed to continue the remarkable work of Sofi Jeannin as the BBC Singers continue to make music that is exciting, relevant and impactful.’

Richard Tanner named as the next Organist and Director of Music at Saint Thomas Fifth Avenue, New York

Saint Thomas Church Fifth Avenue, New York has announced Richard Tanner as its next Organist and Director of Music. Tanner replaces Jeremy Filsell, who has been in the role since 2019, and joins from his position of Director of Music at the prestigious Rugby school in the UK, established in 1567. During his time at Rugby, he founded the Rugby Choristers at Bilton Grange, the UK’s most recently formed Anglican choral foundation. Tanner also became director of Festival on The Close, a five-day celebration of culture community and creativity all in aid of Cancer Research and The Bradley Club.

Speaking of the appointment, Tanner said, ‘I am delighted to have been invited by Fr. Turner to join the vibrant community at Saint Thomas Church Fifth Avenue … I look forward to building on their legacy, excited by the Vestry’s vision for the future.’ Tanner’s career includes 20 years of work as a musical director and organist for BBC Radio 4’s Daily

Service. As producer, he has worked on over 40 commercial recordings and as an organist he has played on numerous recordings including of Messiaen’s La Nativité du Seigneur, music by David Briggs, and The Manchester Carols by Carol Ann Duffy and Sasha Johnson Manning.

ORGAN AT ST JAMES’S CHURCH, PICCADILLY TO BE RESTORED AS PART OF MULTI-MILLION PROJECT

The Renatus Harris Organ at St James’s Church, Piccadilly, will be rebuilt as a part of a £20 million restoration project. 85 years after

the last restorations, which were due to the bombing of the church and the rectory during the Second World War, the ‘Wren Project’ seeks to

rejuvenate the building, courtyard and gardens.

The organ was originally in the private Roman Catholic chapel of King James II in Whitehall Palace. It was then given to St James’s Church by Queen Mary in 1691. The organ served the church well for around 280 years, with the likes of Handel and Leopold Stokowski playing it.

However, the instrument has not been in playable condition since the 1960s. Organ builders Goetze and Gwynn have been commissioned to build the new pipe organ, which will be made in their workshop in Sherwood Forest. A memorial grant has been given by the Julia Rausing Trust towards renewing the organ as well as funding a 10-year organist and sub-organist scholarship programme at the London venue.

Jaya

Vemuri

GAVIN HIGGINS NAMED INAUGURAL ASSOCIATE COMPOSER OF THE THREE CHOIRS FESTIVAL

The Three Choirs Festival has named Gavin Higgins as its inaugural Associate Composer, marking the launch of a major composer development programme. This three-year residency deepens the festival’s ties with living composers, placing long-term creative collaboration at the heart of its programming in the lead up to its 300th edition in 2028.

Higgins’s first commission as Associate Composer, a setting of the Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis, will be premiered at the 2026 Festival in Gloucester, the city of his birth. The work will be premiered by the combined three cathedral choirs of Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester at Choral Evensong on Wednesday 29 July 2026, and will be broadcast live on BBC Radio 3.

The Organ Club celebrates centenary in 2026

The Organ Club, founded by a group of organ enthusiasts in 1926, is set to celebrate its centenary next year. Festivities began this September with a launch lunch in the grand Cutlers’ Hall in the City of London. The event included speeches from the Club’s Vice-President Dame Gillian Weir, and Lord Berkeley (the composer and Radio 3 presenter Michael Berkeley), after which members walked round the corner to St Paul’s Cathedral for Evensong. Celebrations in 2026 include three new compositions for organ commissioned from leading composers, an annual organ-playing competition for teenagers (open to competitors from the UK and overseas) and an organ recruitment drive spearheaded by a group of young members who call themselves The Musketeers.

Each year, a new composer will join the programme, building a cohort of three composers in residence by the third year. Over the course of their residencies, Associate Composers will engage closely with audiences and contribute to the artistic life of the festival, culminating in the premiere of a major choral orchestral work in their final year.

Speaking of the appointment, CEO David Francis says: ‘Speaking on behalf of the Artistic Directors and team at the Three Choirs Festival, we are really excited that Gavin Higgins, who has strong local connections, has accepted our invitation to become our Associate Composer, the first of this new initiative. Over the years our festival has created deep and lasting connections between composers and festival audiences, and this Association will continue that incredible legacy.’

Gavin Higgins added: ‘I was born in Gloucester and grew up in the area, and so the chance to come back home and share my music with the amazing audiences Three Choirs attracts feels very special indeed. I’m looking forward immensely to immersing myself within the festival and introducing some old and new works to audiences over the coming years. I can’t wait to get stuck in – it’s going to be very exciting!’

Yusef Bastaway

TRURO CATHEDRAL WELCOMES

MORE GIRL CHORISTERS

For the first time, girls aged 8-13 are being invited to apply to the Chorister Programme at Truro Cathedral, following the move to welcome girls aged 13-18 for the first time back in 2015. The latest development is part of the Cathedral’s push to enrich the Cathedral’s musical life and lay the foundation for greater inclusivity. The aim is to eventually create a fully mixed-gender chorister group.

All choristers attend Truro School, which offers scholarships to those in the programme. There are also means-tested bursaries to ensure

financial circumstances do not hinder access to the programme.

Truro Cathedral’s Director of Music, James Anderson-Besant, commented, ‘This will widen access to the choir; through an immersive training, children develop teamwork, leadership and confidence skills alongside musical excellence. In due course, we will be announcing our plans for an exciting new scheme to nurture boys’ singing in the 13-18 age

range – an area currently underrepresented in cathedral music.’

The Very Reverend Simon Robinson, Dean of Truro and Rector of St Mary’s Truro, said: ‘This is great news for the children and young people of Cornwall as well as for us.’ At the core of this development is a commitment to empowering young singers and widening access opportunities to all children.

Gloucester Cathedral has announced that its new organ, built by Nicholson & Co., will be installed and unveiled at Easter 2026, in time for that summer’s Three Choirs Festival. The project, which began in 2024, involves a complete renewal of NEW ORGAN FOR GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL TO BE UNVEILED IN 2026

the organ’s mechanism, including new soundboards, console and wind system, while retaining the historic façade and restored Harris pipes dating from 1666.

Designed to serve as a liturgical and concert instrument, the organ will feature an expanded tonal

scheme, including new 32-foot stops, enabling it to accompany both choirs and orchestra.

Assistant Director of Music

Jonathan Hope described it as ‘the heartbeat of the Cathedral’s worshipping life’ and a resource for the wider community.

NORTHERN IRELAND ORGAN COMPETITION

19-year-old Italian organist

Maximilian Haller heralded as the winner of the 2025 competition, which took place in St Patrick’s Church of Ireland Cathedral, Armagh on 11 and 12 August 2025

Haller played a programme consisting of the movement ‘Hermes’ from Jean Guillou’s suite Hyperion, or The Rhetoric of Fire; two movements from JS Bach’s Organ Concerto in D minor, BWV 596 ‘After Vivaldi’, and Reger’s Fantasia in D minor Op. 135b.

Haller is a student at the University of Music and Theatre Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy in Leipzig, Germany. As first prize winner, he receives £4,000 awarded by The John Pilling Trust and a trophy awarded by Neiland and Creane Organ Builders of Kilinick, Co Wexford, together with public recitals hosted by St Thomas, Fifth Avenue, New York, Westminster Abbey, King’s College, Cambridge, St Michael’s Church, Dún Laoghaire and St Anne’s Cathedral, Belfast. Haller also won the Dame Gillian Weir Medal, plus £300 donated by Wilson Auctions, for the stand-out performance of a single work, the Reger Fantasia.

‘For me, the main focus was to give my very best while still letting the music breathe and speak. Performing pieces from the German Romantic tradition, which I truly love, made the whole experience even more special,’ said Haller. ‘The audience was so warm and appreciative, and it was a real joy to share this music with them. I also really enjoyed the atmosphere and the chance to meet everyone involved – it’s a wonderful experience that goes beyond just the prize.’

Second Prize in the Senior category of the competition, which is open to under-21s, went to Jukka Geisler, 19, a student at the

University of Music and Theatre in Munich, Germany, who receives the David McElderry Memorial Award of £1,000 and public recitals hosted by St Paul’s Cathedral, London, Trinity College, Cambridge and The Portico of Ards, Co Down. Geisler also won the Bach Prize of £300, donated by Mrs Elizabeth Bicker MBE.

The third prize was won by Daniel Carroll, 20, from the USA, a student at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. He receives £300 sponsored by Wells-Kennedy organ builders and public recitals at St George’s, Hanover Square, London, Glasgow Cathedral, and Galway Cathedral. Highly Commended Awards were given to Pascal Bachmann (18, UK) and Julien Landers (20, Luxembourg).

Nathan Whitley, 18, from Ireland, won The John Pilling Trust First Prize of £500 in the Intermediate category of the competition, held on the afternoon of Tuesday 12 August.

Second Prize and £300, presented by the Pipe Organ Preservation Co., went to Chamberlain Ofosu (15, United Kingdom). Third Prize and £200 – also presented by the Pipe Organ Preservation Company – went to Gavin Lawrence (17, Ireland).

Rafael Estrella (14, UK) was awarded The John Pilling Trust First Prize of £300 at the Junior Competition held in St Malachy’s Church, Armagh.

The competition jury was chaired by Sophie-Véronique CaucheferChoplin, organist of the Great Organ of Saint-Sulpice in Paris, who was joined by Simon Harden, Lecturer in Organ Performance at the TU Dublin Conservatoire and Organist and Director of Music at Christ Church Cathedral, Waterford, and by David Hill MBE, artistic director of the Bach Choir, London, the Yale Schola Cantorum, Connecticut and of the Charles Wood Summer School, which runs concurrently with the organ competition.

Liam McArdle

25-HOUR ORGAN MARATHON

Organist Hugh Morris is set to take on an impressive endurance challenge when he plays for 25 hours straight, beginning at 5pm on 21 November. He’s undertaking the musical marathon to raise money for the Royal School of Church Music (RSCM), of which he is director, as part of the Royal College of Organists’ ‘Play the Organ Year’.

For most of the time, Morris will be playing hymns chosen at random from Ancient & Modern: Hymns and Songs for Refreshing Worship, but once an hour, on the hour, he will play a standalone organ piece, plus he will be joined by guest

Lambeth Palace Library celebrates 500 years of the Arundel Choirbook

Lambeth Palace Library is celebrating the 500th birthday of the Arundel or Lambeth Choirbook by hosting ‘Sing Joyfully: Exploring Music in Lambeth Palace Library’, an exhibition that runs until 6 November 2025. The exhibition places the Choirbook alongside other musical holdings from the collection, including two leaves of 14th-century polyphony recently discovered in the binding of a 15th-century printed book.

The Arundel Choirbook is one of only two surviving choirbooks from the reign of Henry VIII and an important source for early English polyphonic music. The manuscript volume has been held in Lambeth Palace Library since the 17th century.

To celebrate the manuscript’s quincentenary in musical fashion, chamber choir the Iken Scholars has recorded seven pieces from

performers and local choirs throughout the day. Audience members can donate to request a specific hymn, and the entire event will be streamed live on the RSCM YouTube channel. As part of the event, organists worldwide are invited to join in a mass play along of the Largo from Handel’s Xerxes at 2pm on 22 November.

the Choirbook, to be released this autumn. The seven pieces, recorded for the first time, were anonymously composed and are unique to the Choirbook. The set is known academically as the ‘Lambeth Anonymous’ and the recording took place in the Lambeth Palace Chapel. This autumn, the Iken Scholars will present two concerts with selections from the Choirbook: one in the Great Hall at Lambeth Palace, and the other at St Nicholas’s Church in Arundel, in the same building as the chapel for which the Choirbook was first commissioned.

Mary Clayton-Kastenholz, Curator of ‘Sing Joyfully’ at Lambeth Palace Library, said: ‘It has been a huge privilege to coordinate these activities … it feels as though we are bringing this wonderful manuscript, otherwise silent, to life.’

IN BRIEF…

The British Institute of Organ Studies (BIOS) is hosting a conference, ‘The Global British Organ’, in April 2026 to celebrate its 50th anniversary. Held at Wadham College, Oxford from 9-11 April 2026, it will focus on the global impact of the British organ over the centuries, the influence of foreign organs imported into the UK on the British organ, and the influence of British organ music around the world.

In addition to recitals and conference papers, there will be a gala reception and dinner. Further details and application information will appear on the BIOS website soon.

Music publisher Stainer and Bell has signed an agreement with the charity Elgar Works, securing exclusive worldwide distribution rights for all titles published by the charity. This partnership marks the first time that Elgar Works editions – including the Elgar Complete Edition – will be available globally through a single distributor. The new agreement will see Stainer and Bell make the full Elgar Works catalogue available globally to performers, libraries, academics and enthusiasts.

Lay Vicar Steve Abbott retires after 40 years’ service in Salisbury Cathedral Choir. He joined the choir as an alto in 1985. His highlights include The Prince and Princess of Wales launching the Spire appeal, Desmond Tutu preaching and Edward Heath’s funeral. Abbott will continue to conduct the St John’s singers and the Cathedral Youth Choir as well as rehearsing with the Cathedral Staff Choir he set up earlier this year.

Lambeth Palace Library

NOTES FROM A SMALL ISLAND

CEO Jonathan Mayes reflects on the first part of his 3,000-mile cycling pilgrimage to see 100 choirs in 50 days

And we’re off. The first four days of 50 completed and they were four days of absolute joy! Sunny weather, (mostly) smooth roads, and very warm welcomes. What has struck me the most on this first portion of my ride is how doing the journey by bicycle gives an amazing sense of the connections between places – the architecture, the topography, the people. Cycling brings a particular sense of how places of worship relate to the landscape – sometimes soaring above habitations, sometimes nestled on the edge of a village or next to a key river crossing.

On two wheels you also get a feel for the tangible distance between places of worship, building a detailed picture of the rich tapestry of churches, abbeys, priories and cathedrals dotted across the map. I went from the modern urban reality of Newcastle Cathedral (in which, we heard a brilliant rendition of Byrd…) to historic Carlisle (where, paradoxically, the music took on a more modern hue with Leighton’s setting of the Canticles).

What made these days particularly special, however, were the many conversations I had. I’m hugely grateful to those who made time for me, sharing stories of the huge impact of singing; of the community formed through choirs; and of the splendour of organs, supporting and augmenting music in all these places. I am very much looking forward to many more conversations like this, which all demonstrate the broad and deep passion for cathedral music that exists across the country.

It only occurred to me as I was heading on the train from London back up to Lancaster for the start of Leg 2, that the seven days ahead of me accounted for the longest (though, perhaps surprisingly, not the hilliest) leg of my Choral Adventure, averaging 62 miles each day. I’ve

never tried riding this far before. Seven days of cycling also meant seven nights away from home, and I was hugely fortunate to spend five of those with some wonderful hosts connected to cathedrals and churches in Douglas, Manchester, Chester, Wrexham and Hereford. The hospitality and generosity I encountered was immense and meant that any hopes I had for losing some bodyweight were squashed by the copious quantities of cheese and cake consumed.

The kindness of strangers was also particularly welcome, when, at various times, I found myself soaked through (thanks Lancashire…), with oily hands having tried to fix a broken chain in Shropshire, and for company on the road just when I was running out of steam – especial thanks to Fran Wilson, Lay Clerk at Lichfield Cathedral and cyclist extraordinaire.

All of this leads me to a reflection of how our magnificent choral tradition doesn’t just require physical resources, training and spaces. It needs those things in abundance, of course. But for great music to be sustained, it requires above all things, great people. People who care deeply, who engage passionately, and who share their talents generously.

For Leg 3, I had a lot planned for just two days of cycling – the geography of the West Midlands meant that visiting seven different choral foundations is feasible in the space of around 100 miles – but found myself packing in even more, with what felt like essential detours to places of childhood memory. I’m a Brummie, both in terms of upbringing and in my heart (Up the Villa!). These days of the pilgrimage took me to places I’d not visited in years, and how very wonderful it was to reacquaint myself with them.

The privilege of exposure to joyful experiences in childhood –particularly the musical ones – ought to be the right of every child. We’re doing our part to try and make that

reality here at Cathedral Music Trust; having launched the Small Sounds programme in five cathedrals last autumn, we’re seeing it expand to 12 venues later this year – creating new musical memories for young children and their families at the earliest stages. The value of this work is hugely visible as I visit the places the Trust has funded, reinforcing our continued efforts to increase our support – including this challenge of cycling around the country. At times, the ride feels overwhelming, but then I remember why I’m doing it and find renewed energy to keep pedalling!

The fourth leg was the longest in terms of days in the saddle, distance travelled and number of hills traversed. So it’s no surprise that across the eight days, I went through a range of emotions: from elation to despair; from figurative and literal highs to frustrating lows. The overriding emotion throughout the 20 days so far is still one of great joy and enormous fulfilment. However, a third of the way into this adventure, this is where I also felt some of the challenge of the epic journey. 3,000 miles really is a long way. But I reached the 1,000-mile mark, and it felt like a really significant milestone as I make my way around the country. Read more on Jonathan’s blog and donate to support the Trust at www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

THE SIBTHORP CIRCLE

THE SIBTHORP CIRCLE

The Sibthorp Circle, named in honour of our Founder Revd. Ronald Sibthorp, recognises and brings together the generous individuals who have pledged to remember Cathedral Music Trust with a gift in their Will.

The Sibthorp Circle, named in honour of our Founder Revd. Ronald Sibthorp, recognises and brings together the generous individuals who have pledged to remember Cathedral Music Trust with a gift in their Will.

We give thanks to those who have remembered the Trust in this way.

We give thanks to those who have remembered the Trust in this way.

Michael Antcliff

Michael Antcliff

The Revd Sarah Bourne

The Revd Sarah Bourne

David Bridges

David Bridges

Michael Cooke

Michael Cooke

Eric Cox

Eric Cox

Stephen Crookes

Stephen Crookes

Robert Frier

Robert Frier

Clarendon Gritten

Clarendon Gritten

Rodney Gritten

Rodney Gritten

Julian Hardwick

Julian Hardwick

Edward Hart

Edward Hart

Rosemary Hart

Rosemary Hart

Tom Hoffman MBE

Tom Hoffman MBE

Sheila Kemp

Sheila Kemp

Dr James Lancelot

Dr James Lancelot

Robin Lee

Robin Lee

Jonathan Macdonald

Jonathan Macdonald

Julia MacKenzie

Julia MacKenzie

Kate MacLean

Kate MacLean

Roddie MacLean

Roddie MacLean

Iain Nisbet

Iain Nisbet

Martin Owen

Martin Owen

John Pettifer

John Pettifer

Marc Starling

Marc Starling

David Williamson

David Williamson

Margaret Williamson

Margaret Williamson

And several anonymous supporters

And several anonymous supporters

To find out more or to join The Sibthorp Circle

To find out more or to join The Sibthorp Circle contact:

Leila Alexander T: 0203 151 6096

E: leila.alexander@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

Leila Alexandra T: 0203 151 6096 E: leila.alexandra@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

NICOLAS KYNASTON (1941–2025)

Preston/Murrill; Jackson/ Cocker; Danby/Boëllmann. To many organists of a certain generation, these names will instantly bring to mind the EMI compilation, The King of Instruments. They might continue the list: Willcocks/Bach –and Kynaston/Vierne. This last track – the Carillon de Westminster – was my own first encounter with the playing of Nicolas Kynaston, the virtuoso British organist who died in March 2025 at the age of 83.

Even to my novice ears there was something that set it apart; I couldn’t define quite what it was, although I remember being intrigued by his registration. Other recordings by him soon joined my collection: Popular Organ Works at the Albert Hall (for which he won an award for sales, which he proudly showed to visitors); the Elgar Sonata at Ingolstadt; Bach at Clifton.

Kynaston enjoyed mentioning this appearance when interviewed; it seems pleasingly emblematic of the slightly quixotic aspects of his upbringing. He came from a spiritual and artistic family; his mother was a violinist, his father a priest and painter. A former student recollects ‘waking up on the spare bed in the study, usually with a sore head, to be greeted by the sight of barely covered, cavorting water nymphs, as depicted in an enormous oil painting hanging overhead, painted by Nicolas’s father’.

After a choristership at Westminster Cathedral in London, Kynaston attended Downside, but after taking lessons with Fernando Germani, he walked out, never to return. After further study with Germani and Ralph Downes, he returned to Westminster Cathedral at the age of just 19 as organist, leaving after ten years to become one of the great virtuoso players of the 20th century.

Westminster Cathedral and its organs always kept a special place in

Kynaston’s affections; a recording of his final (2009) recital there is currently available on YouTube.

Kynaston’s renown is easy to understand. His performances packed a punch, as one former student put it to me; his playing was ‘breathtaking, thrilling, communicative, moving, intimate, grand’. His recordings (many now easily accessible online) were, as one producer attests, prepared as if they were performances; Liszt’s Fantasy & Fugue on the Chorale ‘Ad nos, ad salutarem undam’ was once captured in a single 40-minute take.

Public achievement is one thing. But Kynaston’s private activity, as a teacher (including as Professor of Organ at the Royal Academy of Music for 12 years), reveals another side to his musical character. His students speak with unanimous respect and affection of their association. He was civilised, cultured, thoughtprovoking, encouraging, generous, and heedless of time when it came to teaching – lessons would extend long past their allotted span, with no extra payment expected.

He demanded high standards. An example: NK: ‘[redacted]?’ Student: ‘Yes, Nicolas? NK: ‘there should never be any need for wrong notes in the pedals, should there, [redacted]?’ Student: ‘No, Nicolas’. But he was no dictator: ‘He encouraged and enabled me to seek my own authentic voice… he provoked me always to be curious and to explore numerous different approaches –even (especially?) those that didn’t sit well with me at first’.

He gently repaired bruised confidence and broadened musical horizons, instilling in students a sense of line which came from his experience as a French horn player. ‘I have always felt how important it is for organists to widen their horizons, including by playing an orchestral instrument. It is crucial to understand, apart from anything

else, how breath works. A musical line needs to breathe.’

On the matter of breathing, lessons were famously wreathed in cigarette smoke – he was notorious for regularly blocking the chapel drains of one Cambridge college with discarded fag ends.

Kynaston’s last months were spent in a nursing home. He found this difficult, but frequent visits from former students and colleagues brightened his days, and in their company, he enjoyed reminiscing about the past and listening to recordings of his playing. The kindness and respect he showed to young players at the start of their careers was repaid in full.

Kynaston’s own words should close these reflections. ‘I have been obliged sometimes to say to students, “Are you enjoying playing this piece?” I am afraid that just occasionally people have replied that they have not considered that before. But this is the point, the heart of what we do as musicians. The performer is a communicator, trying to express what he or she feels about the music, and trying to capture what the music itself, the composer, is saying, is meaning in the composition. But enjoyment, pleasure, is the core. That is your job. Otherwise, there is no reason to do it.’

STEPHEN FARR

JOAN LIPPINCOTT (1935 – 2025)

Joan Lippincott, one of America’s pre-eminent concert organists and a revered teacher, whose artistry and pedagogy shaped generations of performers and church musicians, died on 31 May in Newtown, Pennsylvania at the age of 89, following complications from a spinal infection.

A musician of extraordinary intellect, technical brilliance and spiritual depth, she leaves a legacy of excellence that continues to resonate through concert halls, churches and conservatories across the country.

Born Joan Edna Hult in Kearny, New Jersey, she studied piano and organ from an early age, eventually becoming a pupil of Alexander McCurdy at Westminster Choir College in Princeton, New Jersey, where she earned both Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees, and at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where she received the Artist’s Diploma. Lippincott

quickly established herself as a formidable interpreter of the major organ repertoire, particularly the works of JS Bach, whose music remained central to her life’s work. She served with distinction on the faculty of Westminster Choir College, where she was Professor of Organ and head of the organ department. With an unerring ear, a fierce dedication to musical integrity, and deep kindness, she was both a demanding teacher and a lifelong mentor to her many students, who became affectionately known as ‘Lippincott Kids’.

In 1967, she signed with Lilian Murtagh Concert Management (which later became Karen McFarlane Artists, Inc). Her discography of more than 20 recordings garnered acclaim for clarity, expressiveness and stylistic insight, in which scholarly rigour and vibrant musicality were always held in elegant balance. Her playing demonstrated her

championship both of historical performance practice and the living American organ tradition. Lippincott served from 1993 to 2000 as Principal University Organist at Princeton University, sat on the juries of several prominent organ competitions, and was active in the American Guild of Organists and other professional organisations. She served on the Advisory Board of The American Bach Society and was an honorary member of Sigma Alpha Iota. Her career was rewarded with a garland of honour, including awards and an honorary doctorate from Westminster Choir College. In 2013, the Organ Historical Society published a festschrift, ‘Joan Lippincott: The Gift of Music’, with Larry G Biser editing contributions from students and colleagues. Rider University awarded her its Sesquicentennial Medal of Excellence in 2015. She was the honouree for the American Guild of Organists Endowment Fund Distinguished Artist Award Recital and Gala Benefit Reception in 2017 and was named International Performer of the Year by the Guild’s New York City Chapter in 2019. Beyond her public accomplishments, Joan was a person of grace, humility, and quiet strength. Her students remember her not merely for her precision and high standards, but for her nurturing of the entire student, person and artist combined. She took deep care with each student’s voice and vocation, guiding both with patience, insight and love. She was preceded in death by her beloved husband, Curtis, to whom she was married 58 years. She is survived by countless former students, friends, colleagues and admirers. A service of thanksgiving for her life was held on Saturday, 4 October at the Princeton University Chapel.

SCOTT DETTRA

PEOPLE & PLACES

We offer our congratulations to the following people who are on the move

Hilary Punnett joins St Paul’s Cathedral as Assistant Director of Music. For the past 20 years she has worked as a conductor and organist across England and Canada, including at the cathedrals of Christ Church Oxford, Chelmsford and Lincoln.

Anna Lapwood MBE, one of Cathedral Music Trust’s ambassadors, has been named the firstever official Organist of the Royal Albert Hall, where she will continue to increase access to organ and choral music and launch a Royal Albert Hall Organ Scholarship.

Ben Collyer has been appointed Sub Organist at Manchester Cathedral. He is currently Assistant Director of Music at St Michael’s Cornhill, Organ Fellow of Sinfonia Smith Square and was until recently Acting Assistant Director of Music at St Albans Cathedral.

Geoffrey Woollatt leaves his Sub Organist post at Manchester Cathedral to become the Director of Music at Bradford Cathedral. Woollatt previously held positions at Chester Cathedral and St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral in Glasgow.

Steven Fox’s tenure at the Cathedral Choral Society in Washington has been extended to 2028-29. He has led the symphonic chorus since 2017, and garnered a Grammy nomination for his recording of Kastalsky’s Requiem for Fallen Brothers.

Peter Siepmann has been appointed Director of Music at Nottingham Cathedral. The conductor and organist has been Organist and Director of Music at St Peter’s Church in Nottingham since 2007 and Conductor of Nottingham Bach Choir since 2019.

Hugh Rowlands also heads to New College, Oxford this autumn as Assistant Organist. He joins following time as Assistant Master of Music at the Chapels Royal, HM Tower of London and Acting Director of Music at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge.

William Saunders has been appointed by Colchester City Council as the new City Organist. The role includes performing at key civic occasions and the annual Mayor Making ceremony. Past roles include Director of Music at The Royal Hospital School.

Nick Rutter

St Pauls, Graham Lacado

www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/legacies

EVENTS

Join us for a Cathedral Music Trust gathering near you

SUNDAY 8 FEBRUARY 2026

Selby Abbey Local Gathering

Discover historic Selby, the hidden gem of North Yorkshire, and journey through the Abbey’s 900 years of worship, music and tradition. Marvel at inspiring architecture, from the famous Jesse and Washington Windows to the intricately carved high altar, and experience the majestic sound of the Romantic-style Hill Organ, one of the finest of its kind in the UK. At the heart of it all, the Choir of Selby Abbey leads us in sung worship.

FRIDAY 6 – SUNDAY 8 MARCH 2026

Oxford National Gathering

Join us in the City of Dreaming Spires to explore the thriving choral tradition in Oxford’s choral foundations. From the world-class choir at Christ Church Cathedral to the stunning Dobson Organ of Merton College Chapel, come behind the gates of the colleges and learn about the hundreds of years of history and musical excellence at work inside their beautiful chapels.

SATURDAY 19 SEPTEMBER 2026

Gloucester Cathedral Local Gathering

With the brand-new Nicholson & Co organ set to be unveiled by Easter 2026, ready for the Three Choirs Festival, our Gloucester Local Gathering offers a remarkable chance to experience this exciting instrument in all its glory. Recently featured in Cathedral Voice, the new organ will serve not only as a liturgical and concert instrument, but also as an inspiration for future generations of musicians. Join us to

be uplifed by the organ, an excellent choir and the stunning Cathedral.

FRIDAY 9 – SUNDAY 11 OCTOBER 2026

Exeter and Buckfast Abbey National Gathering

Discover the work of Exeter Cathedral’s music outreach team and the Cathedral School at the Autumn National Gathering. Saturday will explore the tranquil Buckfast Abbey, near Buckfastleigh in Devon. It’s home to a community of Roman Catholic Benedictine monks, for whom music plays a fundamental role in the Daily Office, and the first Ruffatti Organ in the UK. We come back to Exeter for evensong and our Gala Dinner, with guest speakers Peter and Simon Toyne. With even more music and exploration on offer on Sunday, this weekend promises to showcase the world-class cultural heritage on offer in the South West.

For more information or to book, visit www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/events, email info@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk, or call 020 3151 6096 (Mon–Fri, 9am–4pm).

VOLUNTEERS

Local Ambassadors are needed in these areas: Chichester, Guildford, Winchester, Exeter, Truro, Bristol (and Clifton), Hereford, Worcester, St Albans, Coventry, Birmingham, St Edmundsbury, Cambridge, Lincoln, Sheffield, Wakefield, Liverpool (Anglican and Met), Carlisle, Ripon, London: Westminster Cathedral, Greenwich, Hampton Court, Windsor, Edinburgh, Glasgow and all of Scotland (except Inverness), Bangor, Brecon, Llandaff, Newport and all of Wales (except St Asaph), all of Ireland and Northern Ireland. We would love to hear from you if you are interested in volunteering. To find out more please visit www.cathedralmusictrust.org. uk/support/volunteer or email hannah.capstick@ cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

Buckfast Abbey hosts a Cathedral Music Trust Gathering in 2026

AWARD RECIPIENTS

IN SUPPORT OF EXCELLENCE

As a Friend or Patron of Cathedral Music Trust, your generosity allows us to make awards to support the music-making of cathedrals and churches in the UK and the Republic of Ireland. In 2024, the Trust made 28 awards totalling £500,000. We speak to some of last year’s recipients to discuss their impact

By JONATHAN WHITING, HOLLY BAKER & HATTIE BUTTERWORTH

Derby Cathedral received £29,500 to support the extension of the schools’ singing programme and its Keyboard Pathway as part of the Music in Schools programme

Since its inception in 2021, Derby Cathedral’s Music in Schools programme has been rapidly expanding its outreach, now engaging over 900 children weekly across 18 schools in Derbyshire. A significant and promising aspect of this initiative is the Keyboard Pathway, which provides piano and organ tuition to students across age groups from Key Stages 1 to 4.

Alexander Binns, Director of Music at Derby Cathedral, explains the urgent need for the scheme: ‘Currently, many churches across Derbyshire are desperately short of organists, with most existing players in their 70s or 80s. We established the Keyboard Pathway to nurture the next generation of organists and pianists who can fill these roles in the coming years.’

The programme has made a strong start, currently working individually with 14 young pianists and organists across three schools. Students have access to expert tuition from professional musicians, learning on high-

DERBY CATHEDRAL

Alexander Binns

quality instruments, including a Royal College of Organists digital organ installed in one of the schools. The programme is designed to cater to all levels, providing foundational skills for beginners as well as advanced training for students aiming to achieve higher qualifications or perform publicly.

Performance opportunities have quickly become a cornerstone of the programme.

Derby Cathedral recently hosted a Key Stage 1 concert showcasing some of the youngest pianists in the programme, while older students regularly perform at cathedral services. One pupil, preparing for their Grade5 examination, recently played voluntaries before and after Evensong, providing them with valuable public performance experience.

Binns describes the benefits of these opportunities: ‘Performance builds confidence and skills dramatically. Many children in state schools have limited performance opportunities compared to their peers in independent education. By providing frequent and diverse platforms –from cathedral services to celebration concerts – we’re levelling that playing field.’

Alongside regular tuition, the Cathedral has partnered with the Derby and District Organists’ Association to deliver interactive workshops in local primary schools, introducing younger pupils to the organ through innovative demonstrations, musical games and hands-on instrument-building sessions. They also experience the vast range and versatility of the organ, hearing familiar tunes from Harry Potter and ‘Steve’s Lava Chicken,’ a song from the recent A Minecraft Movie, captivating their imagination and sparking a new interest in the instrument.

The collaboration with the local organists’ association is crucial, providing students with access to additional mentorship, resources and potential future opportunities in the broader musical community. Binns emphasises, ‘It’s about building a musical ecosystem where young musicians can thrive and see a clear pathway forward, whether professionally or as dedicated amateurs.’

Looking forward, Binns hopes the programme will continue to grow. ‘We want to see our keyboard students not only filling church positions across the county but also achieving scholarships and excelling in

broader musical circles. Ideally, we’d like a dedicated full-time Keyboard Tutor to drive this vision, ensuring even greater accessibility and musical excellence.’

The programme has already celebrated significant successes. One student recently won a regional competition in Leicester, highlighting the remarkable standards and exceptional talent emerging from the programme. Additionally, a new Junior Organ Scholarship has been established, creating a formal pathway for talented young musicians to further develop their skills through dedicated training and public performance opportunities at the Cathedral and beyond.

The vision of the Keyboard Pathway goes beyond simply addressing the shortage of church musicians; it aims to foster lifelong passion and engagement with music. Binns notes, ‘We want our students to feel confident and enthusiastic about musicmaking, whatever their future paths. Music provides invaluable personal growth and community connections, enriching lives beyond measure.’

Ultimately, the Keyboard Pathway remains a crucial component of Derby Cathedral’s broader mission: fostering musical excellence, building community engagement, and enriching the lives of young musicians across Derbyshire. Through committed teaching, ample performance opportunities and strategic partnerships, the Cathedral hopes to inspire the next generation of organists and pianists.

LEFT

Alexander Binns hopes to inspire a new generation of pianists and organists with Derby Cathedral’s new Keyboard Pathway initiative

Derby Cathedral

BELOW The three choral scholars and one organ scholar who joined Hereford Cathedral for the 2024-25 year

Hereford Cathedral received £20,500 to support its successful choral and organ scholarship programme

‘We are aware that we have achieved a high standard of choral excellence with the scholarship programme, and we want it to remain excellent,’ Julia Smith, Hereford Cathedral’s Fundraising Officer, explains. ‘The music scholarships are particularly intense, their schedule is full-on with up to eight choral services a week, assisting chorister

training, chaperoning, flyering; they get involved at all levels,’ she continues.

Hereford Cathedral takes on three choral scholars and one organ scholar every year and immerses them in the cathedral’s life. The scholars are housed in St Ethelbert’s house in the city centre, with the cathedral paying for the rent and bills as well as providing a stipend, with the aim that each scholar can dedicate their full time to the cathedral and its music. It is an intense but rewarding year for the scholars, and this summer has been particularly busy with Hereford Cathedral hosting the week-long Three Choirs Festival, as Smith explains: ‘They are entrusted with a lot of responsibility from quite early on. There is the expectation that they are good role models for the choristers and one of them takes on the responsibility of organising the song school as well.’

One of Hereford’s biggest aims with the scholarship programme is making the opportunity accessible for all. They take a range of scholars, some with cathedral music backgrounds but others from local parish churches. Smith explains: ‘We want to keep our reach as broad as possible. We are looking at who is going to benefit the most from the scholarship and who is going to fit in with the other scholars, as they are a close team.’

However, it is not just the scholars who benefit from the programme, but everyone involved in the cathedral’s music, as Smith illustrates: ‘It’s very much a two-way benefit – they’re brought here and receive experience of high-level choral music, but they bring us a fresh energy, and it really reinvigorates the choir.’ The funding has allowed Hereford Cathedral to continue its scholarship programmes at the high standard of which they are proud. ‘We’re so grateful to Cathedral Music Trust as their support has meant we now have the breathing space to make our music more financially sustainable.’ They were at risk of having to cut back in order to fix short-term budget problems, but the Cathedral Music Trust Award has meant that is no longer the case. As Smith says: ‘It’s a real success story, not just for the Cathedral, but for music excellence in Hereford and Herefordshire.’

Hereford

A Church Choir Award of £3,300 was awarded to St Lawrence Parish Church to support the development of the choir and the introduction of midweek services

Jonty Ward, Music Director at St Lawrence Parish Church in York describes the church as traditional, citing the fact they hold midweek feasts in the day, which is unusual for a parish church. ‘It’s the style of worship that needs music really to lift it off the ground,’ Ward explains.

Ward started the church choir himself in 2017 while at university in York, at which point the group was entirely student based. After his degree, Ward stayed on at the Church, growing the choir so it is now open to anyone and boasts a mix of all ages and backgrounds. ‘The funding has really opened up what is possible to do chorally midweek. We have done a lot more this year.’

The church is currently without a vicar, but Ward cites the music as helping keep the energy and impetus of the church alive

between their vicar’s departure and advertising for a new one. ‘Being traditional Anglo-Catholic, we rely on having an incumbent for a sense of direction, so it’s been really important in the absence of the vicar to keep the church vibrant and fresh.’

Ward eventually aims to give the singers a fee. ‘We hope the music becomes a more professional set-up, something similar to a large London parish church. There seems to be a discrepancy between what happens there and in the North of England and we are hoping to change that.’

Despite not being a cathedral, Ward hopes for the same quality and standard of music, which he defines as ‘excellence in liturgy and music, aiming to be on the upper end of what you might expect from a parish church.’

Ward has big plans for the future of choral music at St Lawrence, and the funding from Cathedral Music Trust has allowed them to dream even bigger. Ward also describes the ‘reassurance’ the award has given them: ‘To receive the award has been a validating step for our choral music. Proof that we are heading in the right direction. We are still such a young church, so every year is just going to be better than the previous one.’

ABOVE

Henry Dyer

St Lawrence Parish Church Choir, in York, was set up in 2017 by its current Music Director Jonty Ward

MUSIC ADMINISTRATORS

Rochester and Newcastle Cathedrals have both received funding to support valuable administrative roles

ABOVE Newcastle Cathedral Choir has benefitted from hiring a Chorister Programme Supervisor and Administrator

They are the silent heroes of cathedral music departments, yet rarely do we hear about the work of the music administrator or the impact their presence has. Maybe it is understanding the difficulties of running a department without one that can give the greatest insight into their importance. ‘If only the job was about turning up and conducting a choir,’ says Director of Music Adrian Bawtree, reflecting on running Rochester before a Cathedral Music Trust grant enabled a music administrator to be hired. ‘There are so many things that have to be done in terms of the logistics, the timetabling, the

scheduling. All of this has a knock-on effect as to how much we can then reasonably achieve in terms of artistic creation, because you need headspace for that, you need time to think and time to develop ideas.’

Cathedral Music Trust awarded £29,500 in 2024 to Rochester Cathedral, which enabled them to hire Victoria Kemp. With Kemp now managing the department’s logistics, ‘it’s just beginning to free me up to think creatively,’ Bawtree says. ‘Now, the administrator makes connection with the voluntary choir, makes sure that everybody’s got the message about when the rehearsals are, when we’re singing, what we’re singing, where we need to meet, what are the arrangements for getting into the building at certain times etc. Now, when I turn up for the rehearsal, everyone knows what they’re doing so we can concentrate on the music.’

Peter Cumiskey

Previously much of this administrative work has been done by the assistant organist, someone who traditionally plays the organ for the cathedral’s services. ‘That’s taking them away from time for preparation for the services and the concerts that we do,’ says Bawtree. ‘You can never get away from admin,’ he acknowledges. ‘It just exists, and it exists in spades! You have to have somebody pragmatically-minded who knows what to prioritise. It is of great comfort to me that we now have Victoria because, as an artist myself, I’m quite nervy and I need that pragmatism.’

This is something mirrored by Newcastle Cathedral, who received £28,000 from the Cathedral Music Trust to hire a Chorister Programme Supervisor and Administrator. This position has a large focus on the safeguarding and wellbeing of choristers. ‘With a greater number of children from a range of socio-economic backgrounds now venturing to the Cathedral as Probationer Choristers, Verity’s role is helping us provide an infrastructure that will ensure that these children keep singing, and progress and develop through the choir,’ explains Ian Roberts, Director of Music at Newcastle Cathedral about hiring Verity Hodson Walker. ‘Through Verity’s communication,

administration, and pastoral oversight we are seeking to provide support where it is most needed, so that an ever-increasing number of children continue to receive the wonderful gift of cathedral music.’

Hodson Walker discusses the impact of her role: ‘Where my role is particularly important is ensuring that everyone that comes in and works with the children or alongside them knows exactly what is expected of them and how the adults in the room can support children and look out for them.’ Before her role at the Cathedral, Hodson Walker studied music at Newcastle University, having been a member of the National Children’s Choir. Following a PGCE in Primary Education, she decided she wanted something ‘a little bit more focused in the musical world but centered around teaching and learning.’

‘I’ve been impressed with the commitment of everyone here and how the music department fits in within the wider worship and community of the cathedral,’ she adds. ‘I think it’s really, really beautiful and continuing to grow in its impact of worship – whatever that looks like for an individual.’

For more information on the Trust’s grant programmes and on recipients of awards, visit www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/programmes

Victoria Kemp, the Music Administrator at Rochester Cathedral

LEFT Verity Hodson Walker, Chorister Programme Supervisor and Administrator at Newcastle Cathedral

ABOVE LEFT

BROAD HORIZONS

Dedicated choir schools provide many of Britain’s cathedral choirs with choristers. Yet it’s not the only model and many cathedrals recruit from a variety of schools in their local area

By ANDREW STEWART

Tradition has ways of burying change such that old practices are quickly forgotten and new ones just as soon valued as eternal verities. Take the case of cathedral choir schools, providers of Britain’s choristers for longer than anyone can remember. They belong to a strikingly diverse, surprisingly fluid tradition, one with medieval roots and High Victorian branches. Some are open to residential pupils, some to day pupils, others to both. Yet not every cathedral, whether Anglican or Catholic, offers choral scholarships to a nearby independent school. The venerable choir school model is one of several, increasingly so, as cathedrals strive to recruit choristers from a variety of communities.

Canterbury Cathedral made headline news in 2023 when it announced that it would set aside compulsory boarding for members of its Boys’ Choir and open the doors to choristers from local state schools. The rule change ended an exclusive association with the independent St Edmund’s School, in place since 1972. Beyond considerations of equality and inclusion, the move was driven by a significant fall in recruitment. The new arrangement sees boy and girl choristers each singing three services a week. Current choristers studying at St Edmund’s on a full bursary, worth two thirds of the school’s annual fee, will continue to receive financial support from the cathedral until they leave the choir.

BELOW Canterbury Cathedral moved to a new recruitment model in 2023 for its choirs

Matt Wilson

Dr David Newsholme, Director of Music at Canterbury Cathedral, believes the change will secure the choir’s future. His confidence rests on the experience of recruiting choristers to the Girls’ Choir he founded in 2014. Its members travel to Canterbury from all over Kent. ‘Around 50 children have applied since the new model began two years ago,’ notes Newsholme. ‘We will have 22 girls and 21 boys in the choir stalls this September and expect nine probationers. Since the change, we’ve seen strong interest from children from a wide variety of schools and social and ethnic backgrounds. We welcome children from everywhere, including some from St Edmund’s who want to become choristers. We find that boys and girls from the state and independent sectors flourish here. I think the future’s very bright.’

Canterbury’s new recruitment model has already returned impressive results. The cathedral choir’s recent recording of works by Gabriel Jackson, a former Canterbury treble, received a coveted Gramophone Editor’s Choice accolade. How does David Newsholme respond to those who lament the passing of the boarding requirement?

‘Resistance to change has always been there,’ he replies. ‘But there have been two quite distinct traditions within living memory at Canterbury, with choristers boarding at Choir House in the precincts while being educated at St Edmund’s School and choristers coming to the Choir School as day pupils. Before that, all choristers were day pupils. It shows how things evolve over time.’

Among Britain’s Roman Catholic churches, Arundel Cathedral stands out for the beauty of its Gothic Revival architecture and the

excellence of its choir. Responsibility for the latter rests with Elizabeth Stratford, Organist and Master of the Choristers, who has worked wonders since 2002. Arundel, commissioned by the Duke of Norfolk in the late 1860s, has never kept a choir school. The Sussex institution’s voluntary choir included one boy and one girl at the start of Stratford’s tenure. Today it numbers 24 choristers drawn from 14 primary and secondary schools, some local, others based beyond Arundel. Their socially diverse backgrounds reflect the reality of a rural county, where genuine poverty is often invisible.

‘I want everyone to have a fair shot,’ says Stratford. Her egalitarian ethos stems from personal experience as the child of a singleparent household where every penny mattered. ‘Becoming a chorister at St Anne’s Cathedral in Leeds completely transformed my life.’ Arundel Cathedral Choir offers its own transformative experiences, including one-to-one vocal training, lessons in music theory and the discipline of performing every Sunday. ‘We don’t give scholarships or travel expenses, so it’s a huge commitment for every parent. They must decide whether they can afford petrol costs and if they want their lives to be governed by the weekly round of rehearsals, services and singing lessons. We’re asking them to do something big. The flip side is what their children receive from a very young age as part of this tremendous collaborative experience, involved in delivering the liturgy.’

Arundel’s choir is not exclusively Catholic as most of its choristers attend state and voluntary aided faith schools, with some coming from the independent sector.

ABOVE Arundel Cathedral Choir includes 24 choristers drawn from 14 primary and secondary schools

Marcin Mazur

Stratford visits schools to hear an entire year group sing, choosing children with potential before leading them through a voice trial. ‘I hear every child without knowing anything about their background,’ she observes. Parents receive an information pack and an invitation to attend an open evening. ‘Money is an obstacle, and our 6.30pm Tuesday rehearsal can be difficult for a parent travelling far or caring for other children. There’s also a perception that the church is going to be a particular thing, so it’s about breaking that down by explaining what modern church life is like.’ Her outreach work depends on clear communication and the development of good relations with head teachers. ‘Boys are very much on my radar for upping the numbers,’ she notes, ‘but we already have more than most voluntary choirs. I want the choir to be all-inclusive.’

Ian Roberts, Director of Music at Newcastle Cathedral since 2014, has long experience of building choirs without the support of a choir school. The process, he suggests, requires strategic thinking, strong partnerships and a determination to embed singing in school culture. Newcastle Cathedral’s choir school closed in 1977, following a long decline in its finances, fabric and academic attainment.

‘After I arrived in Newcastle,’ Roberts recalls, ‘I visited every school I could in our large urban area to widen recruitment. At first, we had more children coming to chorister auditions. But I couldn’t sustain going to 60 or 70 schools on a regular basis and being that week’s “community act” at assembly.’ He devised new ways to raise school singing standards, including short bespoke projects with Year 3 pupils. ‘But I wanted to find

something that was longer lasting and resourced so I wasn’t doing it all myself. The game-changer came when we launched our own schools singing programme and then became one of the first Anglican cathedrals to join the National Schools Singing Programme.’

The latter, established in 2021 with funding from the Hamish Ogston Foundation, aims to arrest the decline of music in state schools. It began by covering most of the UK’s Catholic dioceses before welcoming its initial cohort of Anglican cathedrals. ‘Their template means we can tailor what we do in schools to suit the National Curriculum or the Model Music Curriculum,’ notes Roberts. ‘We’ve seen a change in the culture of certain schools and more choristers coming from them. It’s a major line in, but not the only one.’ Others, he adds, include Newcastle Cathedral’s ChoriStarters programme for Year 2 pupils, Mini ChoriStarters for reception pupils, and the Cathedral Music Trust’s Small Sounds early years scheme, which connects infants under five and their parents with cathedral musicians through weekly music sessions.

‘We couldn’t depend on any one thing for developing potential choristers,’ Roberts comments. ‘Getting more choristers has been a wonderful by-product of our Schools

Singing Programme, which enabled 800 local children to get an amazing musical education this year. Of course, I’m envious of colleagues at places with choir schools... Because our choristers meet less often after school, every precious second of rehearsal time has to be utilised. It would be nice to have more time with them, which a choir school would offer. But that’s the only con I can think of, and there are many more pros about our model.’

ABOVE Newcastle Cathedral joined the National Schools Singing Programme to boost chorister recruitment

Peter Cumiskey

THE VIRTUAL CATHEDRAL

During the pandemic, many cathedrals began streaming their services online. Five years on, the practice is flourishing, both widening accessibility and bringing innovation to the choral tradition

By CLARE STEVENS

There has been a transformation in recent years between cathedrals and the communities beyond their walls, thanks to the presence of cameras, microphones and internet-streaming facilities at so many services.

Perhaps you live abroad and your child or grandchild is an organ or choral scholar at a British cathedral, so you might not be able to travel to hear them play in person very often, if at all. Instead you might have been logging on to YouTube or Facebook Live every Sunday to see and hear them at work. The same might be true if you are the relative of a chorister living in the UK, but hundreds of miles from where they sing; or perhaps in the same city but housebound.

Online, you will you have been able to eavesdrop on their regular services. When the valedictory services take place in the summer for choristers, choral and organ scholars, and the community gathers for their final Evensong and The Dean thanks them for their hard work and beautiful singing over many years, shakes them by the hand and sends them out to the next stage of their lives with a prayer of benediction, you can see their reactions, hear the applause of the congregation and listen in real time to the anthem the departing choristers have chosen as their swan song.

who regularly attends weekday Evensong in person, but now family members who are still at work when the services take place, or ferrying other children to afterschool activities, as well as those who live far away, can often catch up with a special service, a short solo or a particularly impressive organ voluntary via a recording.

‘Choir members’ families are part of our congregation,’ says Sarah MacDonald, Director of Music at Selwyn College, Cambridge and Director of the Girls’ Choir at Ely Cathedral. That’s very apparent to anyone

BELOW Chester Cathedral has embedded digital technology into its services INSET

Sarah MacDonald,

Director of Music at Selwyn College

Nick Rutter; Chester Cathedral

MacDonald’s parents live in Canada, and she says they regularly watch her conducting Evensong while they have their breakfast.

The same applies, of course, to other members of a cathedral or collegiate congregation who, for whatever reason, are unable to attend services in person. ‘There is a small group of about 30 chronically unwell members of our congregation who rely on this weekly broadcast to keep them involved with Cathedral life, and to help their mental health,’ says Adrian Partington, Director of Music at Gloucester Cathedral. ‘We set up livestreams during the pandemic as soon as lockdown rules permitted worship in the cathedral, and we were keen to continue with it, since many members of our congregation continued to feel unsafe in public after the pandemic had passed. The number of views each week has dwindled over the past four years, but we are continuing to do it on behalf of those people.’

Other foundations report that numbers logging on to their livestreams have stayed remarkably healthy in the post-pandemic period, and see online platforms, set up as a response to an unprecedented crisis, as an important channel for building new congregations, worth nurturing both for their own sake and as a potential first step towards in-person worship. Both Sarah MacDonald and Dean Tim Stratford (of Chester Cathedral) say they know their live streams of Evensong

during the week are watched and listened to with headphones by large numbers of students, who have the video open on a corner of their laptop screens as they work in college libraries. But there’s also a worldwide congregation of people who join in with the services, greeting each other via the comments bar and establishing virtual relationships with one another and with the participants in the services. This has led to more than one transatlantic visitor turning up at Chester, greeting the clergy by name and introducing themselves as a member of the online congregation. They also have a devotee who owns a chocolate factory in Ohio, and not only sent a cake to her new virtual friends in England, but broadcasts their livestreams to her colleagues in the factory.