How guest ensembles contribute to liturgical life out of term time

The innovative WOOFYT is opening up the instrument to young ears

INSIDE THE ORGAN PALESTRINA AT 500

The composer’s influence on choral music across the centuries CHOIR SCHOOLS

Royal Patron

HRH The Duchess of Gloucester

President

Harry Christophers CBE

Ambassadors

Alexander Armstrong, Anna Lapwood MBE Board of Trustees

Jonathan Macdonald (Chair), James Gurling OBE, David Hill MBE, Sue Hind Woodward, Stuart Laing, James Lancelot, Giverny McAndry, Heather Morgan, James Mustard, Isobel Pinder, Gavin Ralston, Simon Toyne CEO

Jonathan Mayes

Programmes Director

Cathryn Dew

Programmes Manager

Anna Elliss

Development Director

Victoria McDougall (maternity cover)

Development Officer

Katy Ashman

Volunteer & Events Coordinator

Hannah Capstick

Digital & Communications Manager

Anna Kent

Director of Finance & Resources

Jessica Lock

Finance Officer

Amanda Welsh

Cathedral Music Trust is extremely grateful to our team of volunteers across the UK who give many hours of their time each year to support the work we do.

Cathedral Music Trust 27 Old Gloucester Street London WC1N 3AX info@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk 020 3151 6096 (office hours) www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

Registered Charity Number 1187769

Facebook CathedralMusicTrust X @_cathedralmusic

Instagram @cathedralmusictrust

YouTube CathedralMusicTrust

Linked In Cathedral Music Trust

CATHEDRAL MUSIC MAGAZINE

Interim Editor Hattie Butterworth editor@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

Designer Jo Craig

Production Manager Kyri Apostolou

Cathedral Music is published for Cathedral Music Trust by Mark Allen Group twice a year, in May and November. Spring 2025

am writing the welcome to this issue of Cathedral Music sitting in the crypt of St Martin-in-the-Fields church, in the heart of London. Having dropped off my daughter for her rehearsal with the junior choir here, I’m afforded some time to reflect on how music, and the places where we make music, bring people together and help create cohesion. It is brilliant to see in action, as my relatively shy 8-year-old comes to life, launching into joyful song with her fellow choristers.

That is the type of encounter I have been privileged to witness on many occasions over my first 9 months at the Trust; seeing firsthand the impact of cathedral music in many places across the UK. It is also a theme that is reflected across articles in this issue of the magazine as we explore the brilliant training afforded to so many choristers in choir schools across the country (‘Tradition and Change’ p.28), the joy and enthusiasm of visiting choirs undertaking tours and residencies (‘Sacred Soundscapes’, p 39) and the unique challenges composers face when writing for young voices (‘The Brilliance of Youth’ p 46).

It was a particular pleasure to see interviews with some friends I used to sing with at Calvary Church in Pittsburgh, as they travelled to Lincoln Cathedral for a week last summer. Their opportunity to experience the daily routine of services – at a place whose roots trace back to the beginnings of the cathedral music tradition – reminds me what a unique and precious jewel we are custodians of. It is no wonder that there is such strong international admiration for this music and, despite the many challenges we know exist, it is heartening to see the joy with which the next generation plays its part.

As my daughter emerges from the rehearsal room laughing and chattering, I can’t help but feel optimistic about the future, and the role that we all get to play in helping cathedral music to thrive.

Jonathan Mayes, CEO, Cathedral Music Trust

The views expressed in articles are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent any official policy of Cathedral Music Trust.

Advertisements are printed in good faith, and their inclusion does not imply endorsement by the Trust; all communications regarding advertising should be addressed to info@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk.

Every effort has been made to determine copyright on illustrations used; we apologise for any mistakes we have made. The Editor will be glad to correct any omissions.

Corrections from Cathedral Music, Autumn 2024: p.9. Kate Aitken, Head of Voice at St Mary’s Music School, was misquoted, with ‘changing’ voices incorrectly referred to as ‘breaking’ voices. The article also incorrectly referred to St. Mary’s Music School as ‘St Mary’s School’; p.41. Mr Nigel McClintock resigned from his post at Saint Peter’s Cathedral, Belfast in 2019, not in 2022 as originally stated. Please accept our apologies, on behalf on Mark Allen Group, for these errors.

Front cover: Lincoln Cathedral (Photo: Adobe Stock) Back cover: Bristol Cathedral (Photo: Jon Craig)

28 The future of choir schools

Robert Guthrie explores the wide-ranging models for educational establishments connected with choral foundations and the challenges they face

36 The Woofyt

An innovative approach to helping children understand the intricacies of the organ through interactive workshops

39 Visiting choirs

Ensembles from abroad play a crucial role in British liturgical life throughout the holidays –Clare Stevens meets some of them 31 Summer Festivals

Our comprehensive guide to concerts and events taking place in churches and cathedrals throughout the coming months

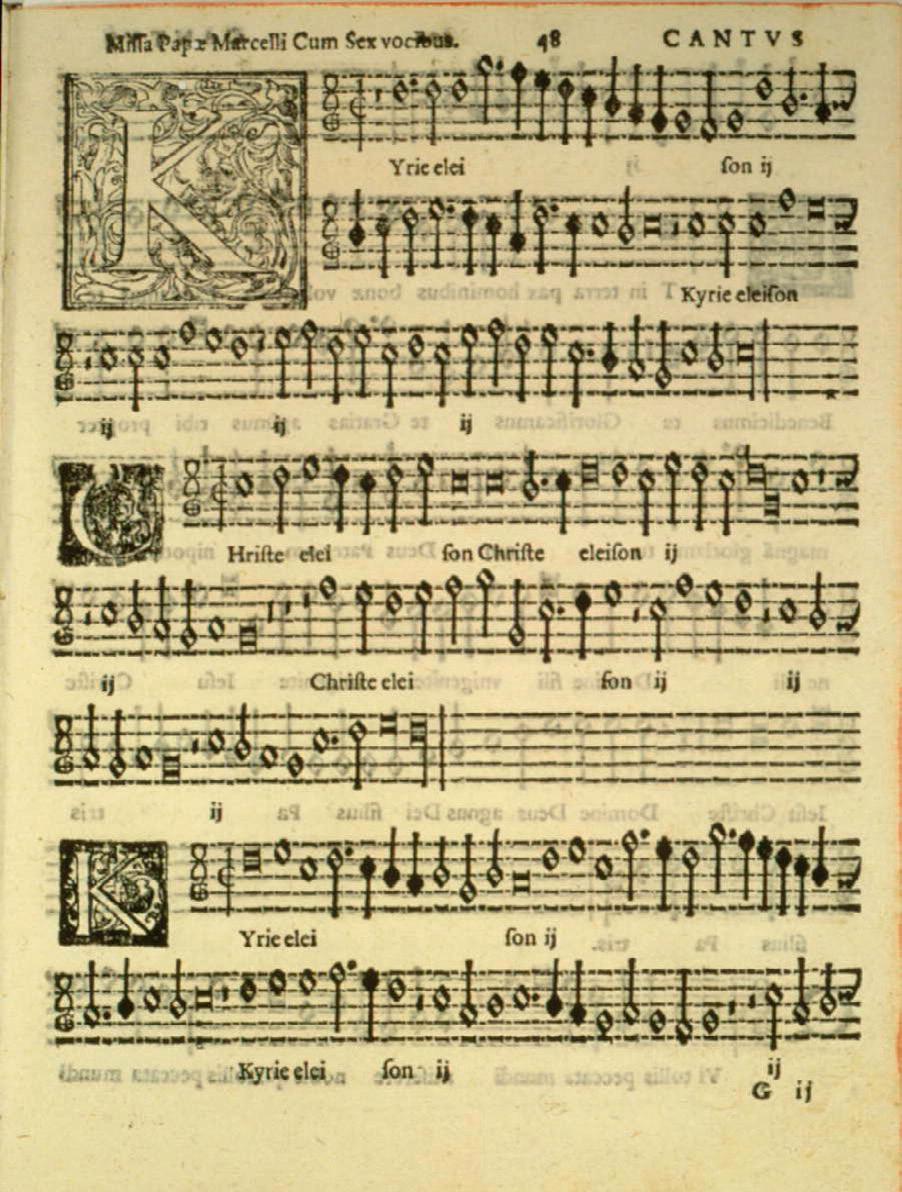

42 Palestrina at 150

As the music world marks the anniversary of the Italian composer’s birth, Edward Breen explores his influence on choral music today

46 Music for childrens’ choirs

Composer Will Todd explains how he writes music for young voices, and the transformative impact the best of the genre can have

3

Cathedral Music Trust’s CEO welcomes you to this new issue

6

The latest developments and stories from across the world of church and cathedral music

19

Who is moving, and to where? We congratulate those taking on exciting new roles

21

Join Cathedral Music Trust at a gathering near you

The organisations which have benefi ted from the Trust’s vital support

Recent releases of choral and organ music reviewed, plus a round-up of the latest scores, and a new novel

66

Cathedral Music Trust volunteer Jean Duerden on the joys of supporting both the organisation and her local cathedral in Blackburn

Anna Lapwood, Director of Music at Pembroke College Cambridge and Cathedral Music Trust Ambassador, has announced that she is to leave her post at the Cambridge college at the end of the academic year. When appointed in 2016 at the age of 21, Lapwood became the youngest person to hold the position of director of music at an Oxford or Cambridge university college, and now leaves to pursue her solo organ career. Since her appointment at Pembroke, Lapwood has developed a significant online following with over

one million TikTok followers, becoming known by many as the ‘TikTok organist’ and opening up the world of the organ to a younger audience. Lapwood is also now an associate artist at the Royal Albert Hall and has sold out her live concert at the hall on 15 May.

In a statement on Instagram, Lapwood said: ‘Some rather big news to share. At the end of this Academic year I’m going to be leaving my job at Pembroke so that I can pursue organ playing full-time. This is, without a doubt, one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever made, and I can’t describe

how much I’m going to miss the wonderful musicians in the Chapel Choir and Girls’ Choir ... I can’t wait to see what they will achieve, and I will be cheering them on from my organ bench.’

Lord Smith, Master of Pembroke, said: ‘Anna has transformed Pembroke’s music and choirs ... she has brought the power of music to make a difference to communities and schools across Zambia; and she has given a real lift to the entire College in the process.’

Luke Fitzgerald will replace Lapwood at Pembroke later this year.

The Cathedral Music Trust has announced a key change to its Board of Trustees, as Jason Groves steps down after six years of service. Groves played a vital role in the Trust’s transition from Friends of Cathedral Music and helped establish the Cathedral Choirs’ Emergency Fund to support musicians during the pandemic. While stepping down as a trustee, he will remain an Adviser to the Trust and take up his new role as Master of the Company of Communicators.

The Trust has appointed James Gurling OBE - pictured below - to

the Board, bringing expertise in marketing and communications. A former Southwark Cathedral chorister, Gurling serves as Executive Chairman of Public Affairs at MHP Group and was awarded an OBE in 2015 for services to politics. Reflecting on his appointment, Gurling said: ‘It was a huge privilege to be a chorister at Southwark Cathedral, where I learned early on the liberating and empowering impact of cathedral music. I look forward to contributing further to the Trust’s important work.’

‘It was a huge privilege to be a chorister at Southwark Cathedral, where I learned the empowering impact of cathedral music’

Notre Dame Cathedral has reopened in the French capital following years of restoration to repair damage from a fire in April 2019. The reopening ceremony welcomed performers including the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France led by Gustavo Dudamel and featuring soloist Olivier Latry, as well as pianist Lang Lang, cellists Yo-Yo Ma, Renaud Capuçon and Gauthier Capuçon, and sopranos Julie Fuchs and Pretty Yende. French organist and composer Thierry Escaich improvised on the cathedral’s newly rebuilt organ.

Royal Birmingham Conservatoire has unveiled its brand new ‘Juliet’ organ in a week-long festival of free concerts and masterclasses. The new 1,138 pipe organ has been custom built by UK specialists William Drake Ltd for RBC’s dedicated Organ Studio.

Quires and Places Founder Tim Popple has announced the publication of a new book. Entitled ‘Evensong –Notes from the choir’ the book is a comical reflection on life as a church musician and an insiders guide to the service of Evensong. Composer Sir John Rutter has said of the book, ‘Tim Popple lifts the lid on its mysteries with the lightest of touches, plenty of anecdotes, and some laughout-loud moments.’ The book will be launched on Wednesday 14 May following Evensong at Holy Sepulchre London.

Fugue State Films is raising money to create its next documentary – The Organ in America – which will explore the story of organs built by immigrants in English and German styles, and how American builders emerged to create instruments in their own distinct styles. Due to the country’s wide scope, the documentary will be split into three parts, the first looking at organ building in Upstate New York. You can find out how to support the project by visiting: fuguestatefilms. co.uk

Cathedral Music Trust held its annual Patrons’ Evensong at Southwark Cathedral on 15 November, bringing together supporters, clergy, and musicians for an evening of choral music. The service, led by Southwark Cathedral Choir, featured Nico Muhly’s Southwark Service, Preces and Responses by Philip Moore, and Parry’s Blest Pair of Sirens. HRH The Duchess of Gloucester, the Trust’s Royal Patron, gave the first reading from the First Book of Chronicles. The event also paid tribute to Ian Keatley, Southwark Cathedral’s former Director of Music, who passed away in summer 2024, aged 42, and who had been instrumental in planning the evening’s programme.

Following the service, David Hill MBE and Revd Canon Kathryn Fleming spoke on the transformative power of cathedral music. A drinks reception in the retrochoir followed, where new CEO Jonathan Mayes thanked Patrons for their continued support.

T he former Organist and Master of Music at St Giles’ Cathedral, Edinburgh, has been recognised in the New Year Honours list for his services to music.

Michael Harris, who served as Organist and Master of Music at St Giles’ Cathedral from 1996 until his retirement in December 2024, has been awarded an MBE for his outstanding contribution to cathedral music.

Harris began his musical journey as a chorister at Gloucester Cathedral before studying at St Peter’s College, Oxford, and the

Royal College of Music, London. His career included roles at Leeds and Canterbury cathedrals before taking up the post at St Giles’ Cathedral, where he played a pivotal role in major state and royal occasions. These included the opening of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, the service of thanksgiving for Queen Elizabeth II, and the Coronation of King Charles III in 2023.

Cathedral Music Trust has expressed its gratitude for Harris’s dedication to cathedral music over the decades and wished him well in his retirement.

The Purcell Club, affiliated to Westminster Abbey Old Choristers Association, is offering guided evening tours of the Abbey. The tours, which last around two hours, offer a unique way to see the historic building accompanied by music. Proceeds from the tours will go towards the upkeep of the Abbey as well as towards its chosen charities. Tickets are available for group bookings only and the Bookings Secretary can be contacted at purcellclubbookings@gmail.com

Saint Thomas Fifth Avenue New York has announced that it will merge its chorister school with the Professional Children’s School New York, and that current director of music Jeremy Filsell will leave at the end of the academic year. In a letter to the Choir School Alumni and Families, Rector Carl F Turner spoke of how ‘both the Vestry and Dr Filsell feel that fresh musical vision is required’.

The merger with the Professional Children’s School was announced on November 7 following months of negotiations by a ‘sustainability task force’ to examine various options for balancing its budget. ‘We

Salisbury Cathedral has received a new chamber organ, funded by The Friends of Salisbury Cathedral. Built by Dutch organ makers Henk & Niels Klop, the instrument is designed to accompany the cathedral choir’s pre-19th-century repertoire and serve as a continuo instrument for concert performances.

John Challenger, Assistant Director of Music, noted: ‘We are pleased to receive this new chamber organ. Its tonal quality, compactness, and versatility make it a valuable addition to the cathedral’s musical resources.’

The organ was first used during Evensong and a performance of Handel’s Messiah in December and more recently in performances of parts IV and V of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio as part of the cathedral’s Epiphany Devotion. Normally housed in the quire, the chamber organ is portable and can be used in various locations within the cathedral.

recognise that the current music programme with a residential choir school is unsustainable,’ it said.

The musical changes spoken of in the rector’s letter are said to include provision for a separate girls’ choir, a choir of professional men and women, and an expanded form of the Noble Singers (a programme initiated under Dr Filsell’s wife Rebecca Kellerman-Filsell) through an outreach project to local children.

Dr Jeremy Filsell joined Fifth Avenue six years ago in 2019, following previous director Daniel Hyde’s move to King’s College Cambridge. During his tenure, Filsell has developed a concert series at Fifth Avenue, and made many recordings of a range of lesser-

known choral repertoire on the Signum and Acis labels.

The process now begins to search for Filsell’s replacement and is chaired by Dr Karl Saunders who currently leads the music committee and is treasurer of the Vestry.

St John’s College has announced a significant new organ project that will see the installation of a historic ‘Father’ Willis instrument in its chapel by May 2026. The organ, originally built in 1889 and previously housed at St Peter’s Church, Brighton, will be restored and relocated by Harrison & Harrison Ltd. The project, the largest of its kind at the chapel in a generation, will involve the careful removal of the existing Mander organ, which has served the college since 1994, and its transfer to St John the Divine in Kennington, London.

Director of Music at St John’s, Christopher Gray, highlighted the instrument’s importance: ‘The Willis organ has an authentic voice for English repertoire and is the perfect instrument for accompanying the choir, with a vast palette of colours that will delicately shimmer in quiet passages and powerfully underpin the most thrilling climaxes.’

During the transition period, a custom-built Viscount Regent Classic digital organ will be used for services. Gray added: ‘Visitors and listeners to our broadcasts and recordings will be able to experience some of the most beautiful music of recent centuries played on an organ of the finest pedigree.’

The Three Choirs Festival has announced its 2025 programme, which this year takes place between July 26 and August 2 in Hereford. The programme includes the revival of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s work The Atonement, first performed at the Hereford festival in 1903 as well as Mendelssohn’s Elijah and Herbert Howells’ Hymnus Paradisi

Elsewhere, two significant world premieres from Bob Chilcott and Richard Blackford will take place, with the Festival’s choirs performing alongside the Philharmonia Orchestra. Other performers taking to the stage in Hereford include celebrated vocal ensembles the King’s Singers and Stile Antico, baritone Roderick Williams, soprano

Sarah Connolly, clarinetist Emma Johnson, and the Carducci Quartet. This year marks the first festival with new CEO David Francis at the helm. Francis said of the announcement: ‘I am in no doubt that the 2025 Three Choirs Festival in Herefordshire is going to be a powerful and inspirational experience for everyone. The 2025 Three Choirs Festival demonstrates our commitment to great choral repertoire, commissioning and premiering new works as well as revisiting festival commissions...’

Booking for the 2025 Three Choirs Festival is now open, available from 3choirs.org/ hereford-2025

‘The 2025 Festival demonstrates our commitment to great choral repertoire, commissioning and premiering new works’

‘Music is the heartbeat of enabling our cathedrals’ worship, and our mission and service to the communities of our dioceses.’ These words from the Very Revd Jo Kelly-Moore, Chair of the Association of English Cathedrals, set the tone at a day-long conference held last November by Cathedral Music Trust and the Association of English Cathedrals. The event brought together cathedral and music leaders from across the country to explore fresh ways to deliver and sustain our rich choral heritage for future generations.

With the challenge of chorister recruitment, rising cathedral expenses, and the inconsistent provision of music teaching in our schools, many cathedrals have already begun to expand and widen their remit to be more inclusive and diverse and to explore different ways

to maintain and grow the rich English choral tradition.

Keynote speaker the Rt Revd Stephen Lake highlighted the need for accountability, financial responsibility and shared goals, noting the role of choirs in mission as well as enhancing worship. Panels were convened to debate how to uphold excellence in the changing musical landscape and to share ideas around building a sustainable financial future.

Jonathan Macdonald, Chair of Cathedral Music Trust, said: ‘While the standards of cathedral music have never been higher, the sector is facing real challenges with financing and recruitment and there is a clear need for musicians, clergy and lay staff to work more closely together to ensure a sustainable future.

‘The discussions at the conference were both open and insightful, and

provided us all with a deeper understanding of the diverse range of issues faced by cathedrals and their music departments.

‘The insight gathered will be invaluable to Cathedral Music Trust as we continue to evolve our support programmes and increase our activity in advocacy and fundraising.’

Cathedral Music Trust has a key role to play in bringing together cathedral and music leaders, highlighting issues for the sector and advocating for the tradition in the media, at government level and globally. The Trust also held its inaugural academic conference last Autumn, welcoming over 100 academics from across the UK and Europe to Salisbury, and will continue to convene leaders in the coming year to drive forward issues of sustainability, excellence and inclusivity.

Buzard Pipe Organ Builders has announced the construction of a new facility to house its organ building operation. It is located in Rantoul, Illinois, 10 miles north of Buzard’s existing Champaign shops. The new 45,000 square foot building will house workshops for its production, service, and tonal departments, attached warehouse space, administrative offices, design

studios and a conference room. The new facility is scheduled for completion during the summer of 2025, with move-in in the autumn. Buzard Pipe Organ Builders will also have space to administer its Apprenticeship Program and to mentor interns and students from the University of Illinois School of Music.

Buzard Pipe Organ Builders

The City of London church of St Bartholomew the Great has announced that it has signed a contract for a new organ with German firm Orgelbau Eule. Following more than two years of negotiation and planning, the new organ is projected to take three years to build and when complete will comprise four manuals, more than 5,000 pipes, and 58 stops.

Speaking of the project, Director of Music Rupert Gough said: ‘St. Bartholomew the Great

is a growing church both in terms of congregational numbers and musical provision. Music lies at the heart of everything we do, and the lack of pipe organ has been a weak link for well over a decade. This new instrument will be a significant and, in many ways, unique addition to the musical life of the city ... we selected Eule Orgelbau for the beauty of their meticulous voicing.’ The projected completion date for the project is Easter 2028.

has occupied its Champaign location for 35 years. Forty-four new pipe organs have been built in the shop, beginning with Buzard’s ‘Spiritual Opus 1’ (actually, Opus 7) at the Episcopal Chapel of St John the Divine on the University of Illinois campus, culminating with its Opus 50 for St Peter’s Lutheran Church, Hemlock, MI, currently in production.

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) Awards, which took place on Thursday 6 March at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, recognised significant achievements in choral singing. Among the winners included Sir James MacMillan and his 10-yearold festival The Cumnock Tryst, which received the Series and Events award. The Inspiration award went to Belfast’s Open Arts Community Choir and music director Beverley McGeown for ‘uniting disabled and non-disabled people from different backgrounds through the power of song’, while record label NMC received the Gamechanger award for its work in promoting the work of contemporary composers.

As CEO Jonathan Mayes begins his choral adventure, he shares the motivation behind cycling 2,700 miles to see 100 choirs in 50 days

Cycling is something I’ve done since I can remember: being taken to school and church on the cross-bar of my Dad’s old postman’s bike; gashing my knees when tumbling off on the ‘ash path’ in Birmingham; unbridled excitement at getting my first drop-handlebar racer at the age of 10; commuting by bike to every single job I’ve had including in sub-zero Chicago and alpine-esque Bristol; going on annual ‘birthday rides’ for my Dad, covering his age in miles (it’s becoming quite challenging of late..!)

Travelling by bike has always been about more than simply getting from A to B. It’s very much a way of life and I have the scars to prove it; and whilst cycling on two wheels is an ideal mode of individual transport, the thing that appeals to me most is how quickly community builds around cycling and cyclists. There’s a two-wheeled camaraderie that means there will always be an interesting conversation to be had or a helping hand available.

That notion was the genesis for the idea of a cycling pilgrimage around England and Wales to visit the many places where Cathedral Music Trust has supported music-making. On our most recent birthday ride (78 miles around Warwickshire and the West Midlands) it struck me just how common it is to encounter great choral singing and organ playing within close geographical proximity. I realised that by connecting all of these places by bicycle, I might demonstrate how, wherever you are across the country, you’re never too far from an evensong or a sung eucharist: from the challenging hills of Cornwall to the gentle flats of

Norfolk; from the heartlands of the Midlands to the rugged terrain of Carlisle.

It sounds fairly simple when written down like that, but a Christmas holiday spent looking at maps has left me in no doubt about the magnitude of the challenge. I am hugely indebted to the excellent route-planning provided in the Cathedral Cycling Route, compiled by Shaun Cutler, which has formed the basis for a ride of around 2,700 miles of cycling and 123,000 feet of climbs across 50 days of riding; equivalent to cycling around 10% of the earth’s circumference at the equator and from sea level to the top of Everest more than four times.

But I’ve told too many people now to pull out, so here I am, announcing to the world that on 16 May 2025 I’ll embark upon my most daunting cycling adventure; setting off from Durham and working my way up to Newcastle (in time to join-up with our Friends & Patrons at the National Gathering – apologies in advance to all of the attendees for the lycra…). I’ll then be working my way around the country in ‘stages’ - typically 4-5 days at a time – across weekends and holidays. The key thing I’m aiming for is to hear choirs sing and organs being played in each location – over 100 separate cathedrals, churches, abbeys and royal peculiars. It’s going to take me a full year to

LEFT Jonathan Mayes begins his life as a cyclist! His route planned will take him around the cathedrals and churches of England and Wales (Scotland and Ireland will have to wait for another time!)

complete the ride, with an aim of arriving back in Durham in May 2026. Spacing out the stages to around 1 trip/month means that I can coincide my rides with services and concerts, whilst also keeping up the day-to-day running of the Trust. It will also help ensure my family still recognises me.

You won’t be surprised to hear that I am using this challenge as a chance to fundraise for the Trust and the support we are giving to musicians and choral foundations around the country. Our work is a critical part of the funding picture for cathedral music around the UK. I hope you’ll donate and encourage others to do so too.

However this isn’t just about fundraising; it is a pilgrimage. A journey to places and, critically, to have conversations with people in those places. I’m keen to use the days in the saddle to build on the communal aspect of cycling and will be inviting friends, colleagues, musicians and supporters to join me on the road. Please get in touch if you’re up for sharing in a leg of the journey with me! I hope to share some of those conversations with you over the coming months; highlighting not just the brilliant music-making that exists in cathedrals and churches across the country, but also the superb people who make it happen. Wish me luck!

OBITUARIES

Herbert John La French

Norman, who preferred to be called John, was born in Hornsey, North London, on 15 January 1932, and became a leading authority on organs, as consultant and author. The only child of Herbert and Hilda Norman, he attended Tollington Grammar School in nearby Muswell Hill, moving to Norwich School from 1942-45 to escape the bombing of London. Aged 15, he started learning to play the organ, having to give this up when he went to study at Imperial College, London, where he took a BSc in Physics (specialising in acoustics), met Jill in 1951 and graduated in 1953. Getting married in 1956, the couple first lived in East Barnet and in 1964 moved to a house in Whetstone, where Norman lived for the rest of his life. Jill fell ill in 2001, was looked after at home by Norman for many years, and died in 2018. In 2020 he met Jill Hollywell and they had five happy and fulfilling years together. After enjoying a cruise with Jill, Norman developed pneumonia, dying peacefully in Barnet hospital on 27 January.

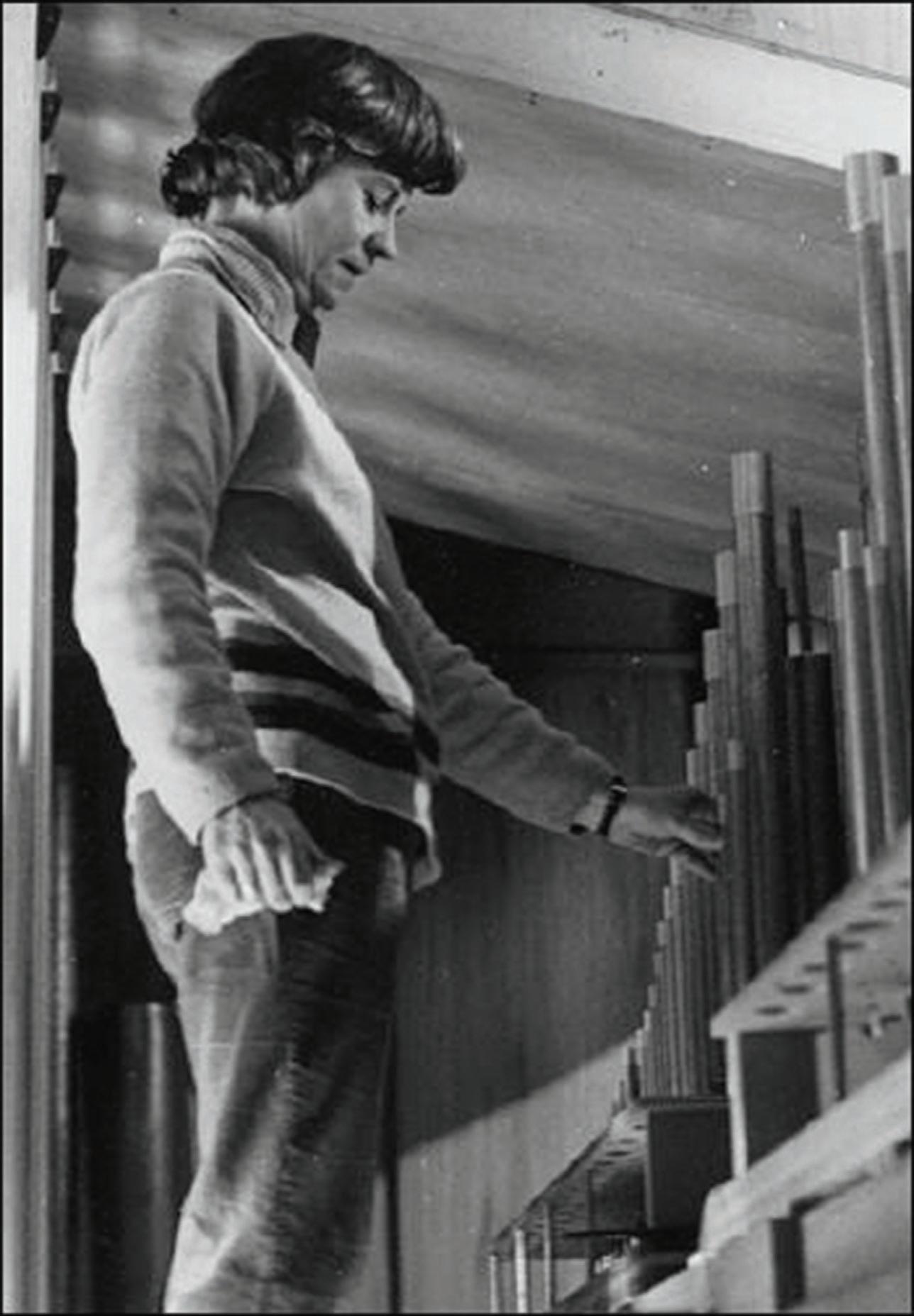

John Norman said that his introduction to the organ world had been ‘Cleaning’ what he described as ‘a somewhat doubtful little organ in the Methodist Mission Hall off the Old Kent Road’. This was a holiday job given to him, aged 16, by his father Herbert, managing director of Hill, Norman & Beard. Norman joined the family firm in his twenties, becoming a director in 1960. He travelled extensively around the world for the company, which at the time had subsidiary workshops in Canada and Australia. He had a particular interest in three areas of work. One was the

design of new electrical mechanisms of all sorts, principally the firm’s compact electro-magnetic switching and combination relays and the application of pallet magnets. The second was in continuing to develop (with voicer Mark Fairhead) the neo-baroque style of voicing which the firm adopted in rebuilds and new organs from the early 1950s. The third was in designing clever compact organs for churches with modest space or little money, using a limited amount of inter-rank borrowing for bass octaves of 4ft and 2ft stops. These organs, and the Pedal additions in the company’s rebuilds, used Norman’s design of direct-electric chests with large cardboard tube expansion chambers. The climax of his inventiveness was the unique electro-magnetic action for the 1971 Gloucester Cathedral organ, the year in which he replaced his father as managing director. In addition to the Gloucester organ and a sizeable clutch of new small instruments, Norman would have considered as his most significant projects the rebuilds in St Mary-at-Hill, Bath Abbey, Lichfield Cathedral and St Mary Stafford.

Things were not easy for HN&B in the early 1970s so in 1974 John resigned. He joined IBM, remaining with them until his retirement in the late 1980s. He was responsible for the IBM customer magazine and selling large computers to corporate organisations. While at IBM, his friend Michael Gillingham suggested that he assist the London Diocesan Advisory Committee for the Care of Churches with faculty applications for organs. This took him back into the organ world and he remained

‘He acted as consultant for numerous organs – the most exquisite was for the Undercroft of the Palace of Westminster’

adviser on organs to the London DAC until his death, his final project for them being advice on a proposed large new organ for St Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield.

He shared with his architecttrained father a passion for church architecture and good organ case design, enjoying singing in the choir of St John the Evangelist, Friern Barnet, a beautiful Gothic church by Pearson, where his funeral service took place on February 28. John had always enjoyed writing. In 1966 he co-authored with his father his first book, The Organ Today, bringing out a revised second edition in 1980. He began writing his column –Soundboard – in Organists’ Review in January 1980 and maintained it until his death. From 1983-2000 he was founding editor of The Organbuilder (the journal of the Institute of British Organ Building) and in 1984 he published The Organs of Britain – a substantial ‘Appreciation and Gazetteer’ of British organs, illustrated, as so many of his writings were, with fine line drawings by his father. His final books, notable for their attractive design and appearance, were The Box of Whistles (2007), about organ cases over the ages and Organ Works (2020), subtitled ‘What is an organ and how does it work?’.

A founder-member of the Association of Independent Organ Advisers, John acted as consultant for numerous significant organs over the last 30 years of his life. The most exquisite of these was for the Undercroft of the Palace of Westminster (1999), the largest was for Worcester Cathedral (2008) and the final one will be a new instrument for St James’s Piccadilly, yet to be constructed.

John Norman will be remembered for his organ projects, his books, and for his generous and warm personality.

PAUL HALE

A captivating collection of sacred choral music commissioned especially for the daily services of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, conducted by Hilary Punnett with organist Simon Hogan.

An enthralling selection of Renaissance choral music, and works by contemporary female composers, sung with clarity, precision and sensitivity by luminatus vocal ensemble.

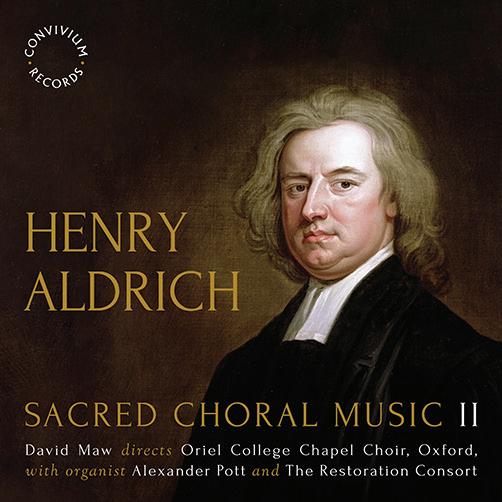

Oriel College Chapel Choir have completed the second instalment of the ongoing Henry Aldrich research project, dedicated to bringing his original works to a wider audience.

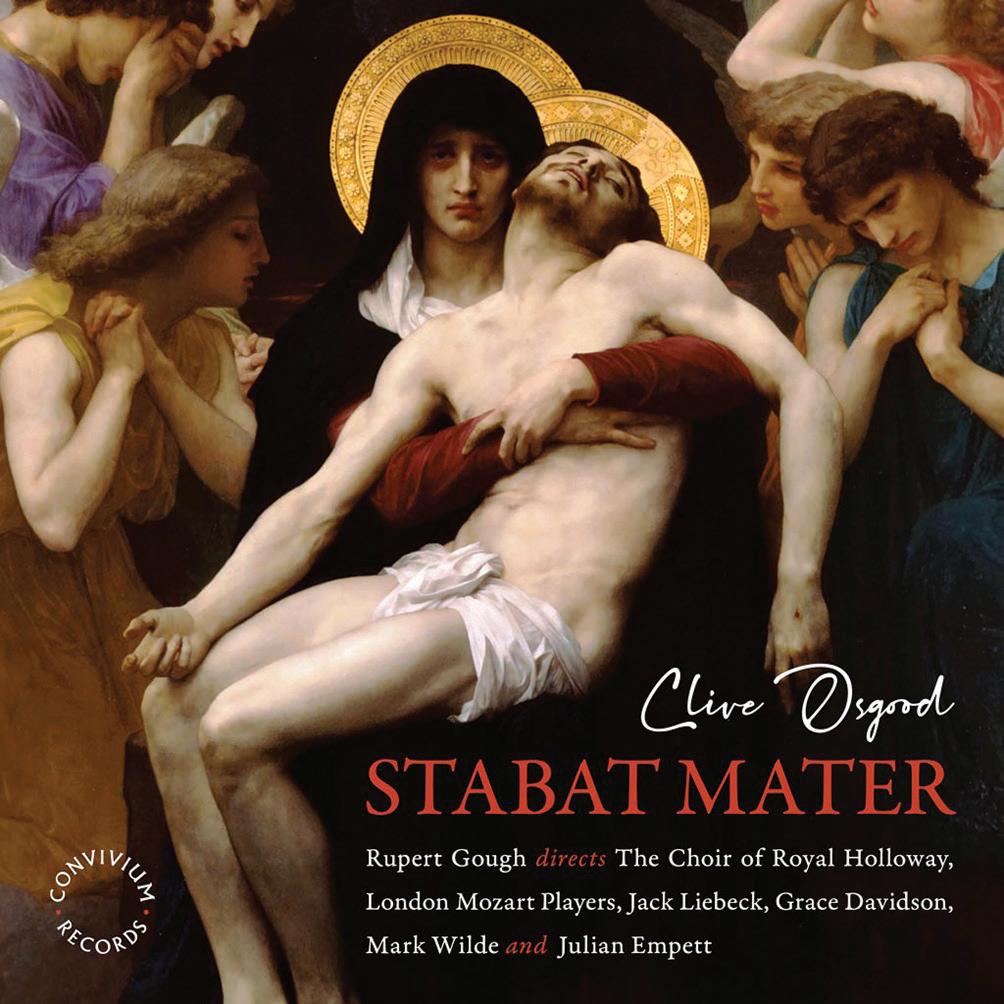

A spellbinding recording of Clive Osgood’s exquisite Stabat Mater, a 13th century hymn to the Virgin Mary, performed by soprano Grace Davidson, violinist Jack Liebeck, the Choir of Royal Holloway and London Mozart Players under conductor Rupert Gough. AS HEARD ON:

Conducted by Stephen Layton, Polyphony sings Clive Osgood’s beautifully reimagined arrangements of English folksongs, continuing the tradition of music handed down through the generations.

DOWNLOAD AUDIO FILES OR PRE-ORDER YOUR CD WITH FREE SHIPPING AT WWW.CONVIVIUMRECORDS.CO.UK

Barbara Jane Owen, 91, the doyenne of American organ historians, died peacefully on October 14, 2024 following a brief decline caused by a broken hip. She had an illustrious career spanning nearly seven decades as a church organist, organ builder, historian, consultant, author and music editor. In 1994, she received the American Musical Instrument Society’s prestigious Curt Sachs Award.

Born on January 25, 1933 in Utica, New York, to Welsh

immigrants, David and Vera Owen, she was the oldest of three daughters. In her early school years, the family moved to New Haven, Connecticut, and attended Plymouth Congregational Church. Singing in the youth choir, she was influenced by the church’s joint music directors, William and Priscilla Mague. Both were graduates of Westminster Choir College, as was their successor, so she enrolled there.

After receiving her Bachelor of Music degree from Westminster in 1955, Owen held appointments at

First Congregational Church in Portland, Connecticut (1955-58) and First Baptist Church in Fall River, Massachusetts (1958-60). In late 1960, she enrolled at Boston University for a master’s degree in Musicology, received in 1962, studying under the eminent scholar Karl Geiringer. She later took summer courses in Europe at the North German Organ Academy and the Academy of Italian Organ Music.

While in high school, Owen developed a curiosity about pipe organs and began exploring instruments in the New Haven area. This blossomed into a passion after she graduated from college and had a car. At the 1956 American Guild of Organists national convention in New York City, Owen and 11 other young organ enthusiasts met to search for historic pipe organs. Thus began the Organ Historical Society, with Owen as its first president. Its founders aspired to locate extant 19th-century American ‘tracker’ organs and create a comprehensive list.

During the summers of 1961-63, she worked at the Craigville Retreat Center, then affiliated with the United Church of Christ, in Centerville on Cape Cod. There, she instigated the first of several ‘organ transplants’, leading to the formation of the Organ Clearing House, which has since relocated more than one thousand instruments. The first organ was the 1881 E & G G Hook & Hastings, Op 1018, originally installed in a studio at Wellesley College. Owen rounded up some friends and a truck to move it to the Craigville Tabernacle, where it is still used and was featured in a July 2022 concert marking the centre’s 150th anniversary.

In 1963, she relocated to Massachusetts’ North Shore, continuing as office manager, and later a voicer, with C B Fisk in Gloucester (1961-79), and starting as music director at the First Religious Society of Newburyport, an appointment she held for 40 years.

In 2002 she moved on to St Anne’s Episcopal Church in Lowell, Massachusetts, where she remained until 2007, thereafter playing substitute engagements.

Owen was a prolific writer, authoring 13 books and monographs about organs, organists and organ builders. Her first book, The Organ in New England (1979), is the bible of that region’s organ-building history before 1900. Her final book, Pioneers in American Organ Music, 1860-1920: The New England Classicists, appeared in 2021. Internationally, she is known for her biography of British American concert organist E Power Biggs (1987), and as coauthor, with Peter Williams, of The Organ (1988). She also edited multiple collections of organ and choral music from various eras.

She served the American Guild of Organists as a regional councillor and chapter dean and established the Boston Chapter AGO Organ Library, located at Boston University. She also served for 34 years (1989-2023) as a trustee and archivist of the Methuen Memorial Music Hall. As an organ consultant, Owen patiently helped organ committees learn about the organ, equipping them to make educated decisions.

Always brimming with helpful ideas, she occasionally made suggestions which changed people’s careers. Among those who give her such credit are Wayne Leupold, founder of the eponymous organ music publishing house; Stephen Pinel, the third and longest serving Organ Historical Society archivist (1984-2010); and this writer, whom she invited to become a Methuen Memorial Music Hall trustee.

A musical celebration of Barbara Owen’s life will be held on October 13, 2025 at the Methuen Memorial Music Hall.

MATTHEW BELLOCCHIO

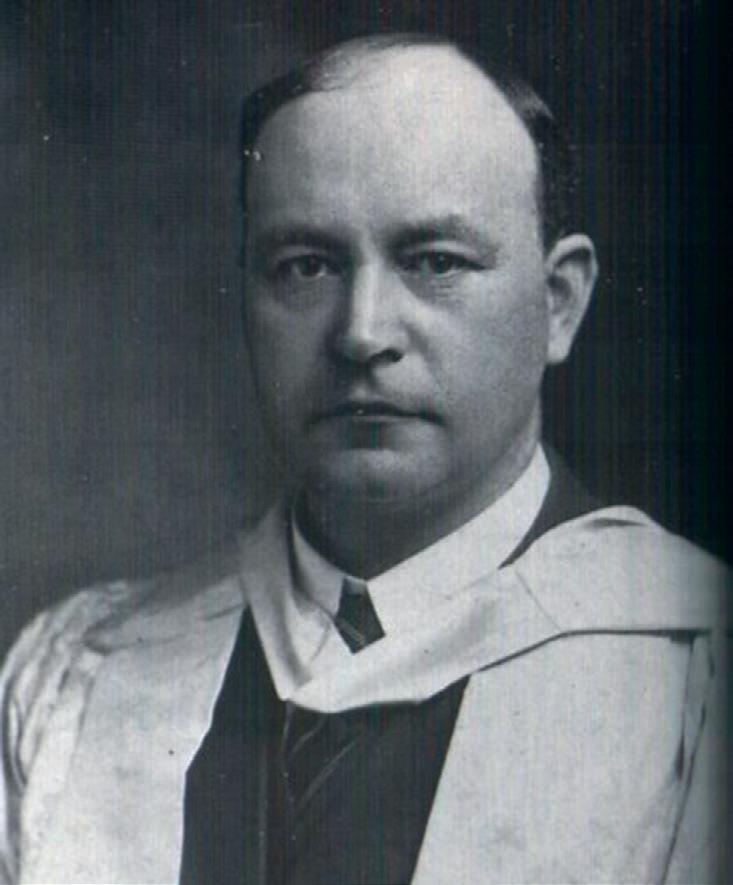

On February 25, 2025, we lost one of the foremost church musicians of a generation, Dr Simon Lindley.

Born in London in 1948, to an Anglican clergyman and a mother of Belgian heritage, Lindley was educated at Magdalen College School, Oxford, and the Royal College of Music. He held organist’s positions at various London churches before becoming the first full-time assistant to Peter Hurford at St Albans Cathedral in 1970, where he was also director of music at St Albans School. In 1975, he performed Elgar’s Organ Sonata at the BBC Proms, in a concert alongside the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Sir Adrian Boult.

Without doubt, Lindley will be best remembered for his long and accomplished tenure as organist and master of music at Leeds Parish Church (now Leeds Minster) from 1975 to 2016, and as Leeds City Organist from 1976 to 2017. He inherited an established tradition at the Parish Church, dating back to S S Wesley and Bairstow, and it is a tribute to Lindley’s indefatigable character that the tradition of daily Evensongs continued there into the 21st century, the choir appearing regularly on broadcasts. Regular commissions were also a feature of his tenure including new works by Herbert Sumsion, Philip Moore, Francis Jackson and Bryan Kelly.

Generations of choristers, organ scholars and assistants, many of whom now hold major church, cathedral and other professional positions, were nurtured and learnt their trade from Lindley through his skill and encyclopaedic knowledge. One cannot go far within the musical circles of Yorkshire without mention of Lindley’s name. In an

interview for BBC Radio, he once described himself as a ‘general practitioner in music’, manifest by the number of appointments he held over many years: senior lecturer in music at Leeds Polytechnic (now Leeds Beckett University); director of Sheffield Bach Choir, Doncaster Choral Society, St Peter’s Singers and Overgate Hospice Choir; chorus master of Halifax Choral Society and Leeds Philharmonic Society.

President of the Royal College of Organists between 2000 and 2003 and of the Incorporated Association of Organists from 2003 to 2005, Lindley was also secretary of the Church Music Society and a compiler of New English Praise, a supplement to the New English Hymnal. His lyrical and well-loved setting of the Ave Maria is a staple of almost every church choir and has been sung all over the world. Simon was a freemason for many years, combining his passion for masonry and music as grand organist to the Grand United Lodge of England between 2010 and 2012.

On a personal note, I shall be forever grateful to him for his overwhelming generosity to me when I was growing up as a young organist in West Yorkshire, and latterly as his organ scholar at Leeds Parish Church. He spent many hours teaching, mentoring and guiding me gratuitously. There are many anecdotes about him and his legendary character, always told with great affection by those who knew him. He will be missed by many, as shown by the large number of social media posts and other tributes which have been written since his death. Requiescat in pace.

ALEXANDER BINNS

‘One cannot go far within the musical circles of Yorkshire without mention of Lindley’s name’

The composer Sofia Gubaidulina has died aged 93. One of the leading Russian composers of her generation, she pioneered Modernist techniques and religious themes at a time when both were repressed by the Soviet authorities. She spent the last decades of her life in Germany, writing large-scale works to commissions from Western orchestras, but always retaining strong links to her Orthodox faith and Russian roots.

Gubaidulina was born in Chistopol in southern European Russia in 1931. After attending Kazan Conservatory, she studied at the Moscow Conservatory under composers Nikolai Peyko and Vissarion Shebalin. The uncompromising intensity, radical atonality, and dynamic extremes of her later work were already apparent in a series of early piano pieces, including Chaconne (1963) and Piano Sonata (1965), both of

which have retained significant status in the repertoire. Meanwhile, she made a living composing music for films and documentaries, achieving minor celebrity in Russia with her score for the Kipling-based animation Adventures of Mowgli (1971). Her Western breakthrough came with Offertorium, a violin concerto premiered by Gidon Kremer in Vienna in 1981. The religious and ritualistic connotations of the title are also indicative: like many in Soviet Russia, Gubaidulina adopted the Orthodox faith in the 1970s, despite the state repression, and it would go on to inform all her later work. This is particularly evident in her choral music, including Alleluia (1990), Now Always Snow (1993), and Sonnengesang (1997), which set sacred or spiritually reflective texts with a deep sense of personal devotion.

In 1992, Gubaidulina moved to a village near Hamburg, and most

of her later works were written to Western commissions. In 2000, she was commissioned by Helmuth Rilling’s Internationale Bachakademie Stuttgart to set the St John Passion as part of a project to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Bach’s death. In 2002, she followed this with a complementary oratorio, JohannesOstern, the resulting diptych her largest-scale composition.

Her music was championed by leading Western performers, including Anne-Sophie Mutter, who commissioned In Tempus Praesens (2007), which she premiered with Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic.

Andris Nelsons and the Gewandhaus Orchestra have also been important advocates, releasing an album of her recent works – Ich und Du, The Wrath of God, The Light of the End – on DG in 2021.

GAVIN DIXON

We offer our congratulations to the following people, who are on the move

Helen Smee

In February 2025, Southwark Cathedral announced Helen Smee as the next Director of Music. She is currently the Director of Frideswide Voices, the girls’ choir of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford.

George Inscoe

In March 2025, George Inscoe took over as Sub-Organist at St Paul’s Cathedral. Inscoe previously held the same position at Croydon Minster. He continues his career as a recitalist, continuo player and conductor.

Robbie Carroll

In November 2024, Robbie Carroll, former Assistant Organist at Norwich Cathedral, joined Rochester Cathedral as Assistant Director of Music. He is also the Assistant Director of Rochester Choral Society.

Jacob Collins

In January 2025, Jacob Collins was appointed Director of Chapel Music at St Hugh’s College, Oxford. He was previously Director of Music at Crown Court Church of Scotland in Covent Garden.

Adam Field

Announced in February 2025, Adam Field will assume the role of Sub-Organist and Assistant Director of Music at Bath Abbey. Previously, Field was an Organ Scholar at Westminster Abbey.

Hilary Campbell

Associate Conductor of Ex Cathedra, Hilary Campbell was appointed in February 2025 as the inaugural Director of Choral Music at Kellogg College, Oxford. She will lead the formation of Kellogg’s first choir.

Alexander Hamilton

In April 2025 it was announced that CMT committee member Alexander Hamilton will take up the post of Director of Music at the Chapel Royal, Hampton Court in succession to Carl Jackson who retires this year.

Luke Fitzgerald

In April 2025 it was announced that Luke Fitzgerald would replace Anna Lapwood as Director of Music of Pembroke College, Cambridge. He will take up the position next academic year.

The Sibthorp Circle brings together and recognises the support of all generous individuals who have notified us of their intention to remember Cathedral Music Trust with a Gift in their Will. The Circle is named after our Founder, Revd. Ronald Sibthorp, in honour of the far-reaching impact of legacy gifts.

With thanks to

Michael Antcliff

The Revd Sarah Bourne

David Bridges

Michael Cooke

Eric Cox

Stephen Crookes

Robert Frier

Clarendon Gritten

Rodney Gritten

Julian Hardwick

Edward Hart

Rosemary Hart

Tom Hoffman MBE

Sheila Kemp

Dr James Lancelot

Robin Lee

Jonathan Macdonald

Julia MacKenzie

Kate MacLean

Roddie MacLean

Martin Owen

John Pettifer

Denis Roberts

Marc Starling

David Williamson

Margaret Williamson

And several anonymous supporters

To find out more about joining the Sibthorp Circle or to discuss how you can support the work of the Trust, please contact Jonathan Mayes on +44 (0)203 151 6096 or email jonathan.mayes@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk

Don’t miss the opportunity to join a Cathedral Music Trust gathering near you

FRIDAY 16 – SUNDAY 18 MAY 2025

North-East National Gathering

The Spring 2025 National Gathering will be jointly hosted by Newcastle Cathedral, Hexham Abbey, and Durham Cathedral, taking advantage of the proximity of these three ancient places of worship. The programme includes a talk by Ian Roberts, Director of Music at Newcastle Cathedral, a presentation from the Hexham Abbey Music Department including a talk from Michael Haynes, Director of Music, and a short concert and Choral Evensong at Durham Cathedral with and a short talk by Director of Music Daniel Cook.

SUNDAY 21 SEPTEMBER 2025

Sherborne Abbey Local Gathering

Save the date for a service of Choral Evensong at Sherborne Abbey which will be followed by a talk and an organ recital.

FRIDAY 3 – SUNDAY 5 OCTOBER 2025

Canterbury & Rochester National Gathering

Our Autumn 2025 National Gathering will take place at Canterbury Cathedral. Join us for a long weekend of choral services, recitals, talks, and tours over the course of the three days.

For more information or to book, visit www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/events, email info@cathedralmusictrust.org.uk, or call 020 3151 6096 (Mon–Fri, 9am–4pm).

6-8 MARCH 2026

Oxford National Gathering

Save the date for the Spring National Gathering which will take place in Oxford from 6-8 March, 2026

9-11 OCTOBER 2026

The Autumn National Gathering

The Autumn National Gathering will take place between Exeter Cathedral and Buckfast Abbey from 9-11 October 2026.

As a Friend or Patron of Cathedral Music Trust, your generosity allows us to make awards to support the music-making of cathedrals and churches in the UK and Republic of Ireland. In 2024 the Trust made 28 awards totalling nearly £500,000. We speak to some of last year’s recipients to discuss their impact

By HATTIE BUTTERWORTH & HOLLY BAKER

Lincoln Cathedral received a grant of £20,000 to support the employment of a Music Outreach Officer (right)

The current choristers singing at Lincoln Cathedral – 20 boys and 20 girls – come from 20 schools across the city. It must be a logistical nightmare, as the cathedral has also committed to providing transport for all the children. They have three morning rehearsals and three afternoon rehearsals per week, each of which requires transport for the choristers. But could there be a way of finding a larger cohort of children from a smaller pool of schools?

Its grant from the Trust has made it possible to employ Jack Holliday [pictured above] as Music Outreach Officer. Director of Music Aric Prentice says that hiring Holliday was both to provide a recruitment model for cathedral choristers and as part of the cathedral’s commitment to outreach. ‘We’re trying to find the right children who want to commit themselves. We’ve put huge amounts of time into recruiting ever since I’ve been here, so it’s a different thing that we’re trying with Jack, but it’s already proving very beneficial.’

Holliday is a music director with a background in musical theatre, and is delivering a singing programme in four initial Lincoln primary schools. He’s been working with year groups 3 and 4 since November and has already provided the cathedral with a new probationer.

‘He’s got a great little voice on him,’ Holliday says of the young singer. ‘He’s so enthusiastic. In most schools there’s at least four or five other students per class that have the potential of joining the song school.’

It’s hoped that targeting a smaller number of schools will bring in plenty of probationers who already have some sort of musical theory knowledge and base of singing technique. ‘The teaching I’m doing in the schools mirrors fairly closely with how it runs in the song school. They can just slot straight in. We’re doing a couple of the more standard classical musical theatre numbers with them and then mixing in some choral bits.’

This model is not entirely new, and

something the Trust has had experience in facilitating. Prentice explains that the Trust’s advice and guidance has been as beneficial as the financial element: ‘Cathedral Music Trust has been very helpful in guiding us to set it up and explaining how it’s worked in other places. Things such as what age groups we should be targeting. We’ve also had a lot of help from Choral-Hull, which is the Hull Minster scheme, and [Director of Music] Mark Keith,’ Prentice continues. ‘They have a very similar thing which has only been running for about three years, but has already produced huge results.’

For the majority of the school children Holliday works with, singing in Lincoln Cathedral won’t be on the cards. So how can he make sure that the sessions delivered aid the general music education of young kids?

‘My main aim with most sessions, alongside obviously trying to gain students, is making sure that they’re having fun,’ Holliday replies. ‘It’s so important that they’re enjoying it and are engaging in the lessons whether they like singing or not.’

Prentice adds, ‘I think that’s a very powerful thing for the cathedral to be doing – using music of course, but also partnering with schools in a completely different way. Getting children much more engaged with the cathedral and making that connection.’

‘Funding for us is absolutely essential,’ Prentice concludes. ‘We wouldn’t be able to do it otherwise. With the Trust’s expertise and willingness to find the funding for us to be able to do this work. Hopefully it will be wonderful for the schools – it’s already wonderful for us!’

St Ann’s Church, Manchester received a grant of £5,500 to support a project recruiting post-graduate singing students and to provide vocal coaching for associate choir members

St Ann’s Parish Church in Manchester is incredibly focused on the quality of sound of its choir. In October 2023 their previous Director of Music Alexander Rebetge proposed a vocal coaching scheme in partnership with the Royal Northern College of Music. Helen Lacy, Church Warden, explains: ‘He came from a background of high-quality choral teaching and was very focused on improving the sound that the choir makes, as well as an increase in the range of music the choir sings.’

Rebetge put together a plan for two students from the RNCM to come and provide vocal coaching to members of the choir, in order to improve personal confidence and techniques within the choir, as well as delivering the students valuable teaching experience.

Lacy continues: ‘The funding from the Trust has enabled us to realise this ambition. We have been able to offer two vocal studies students from the RNCM an award towards their continued studies to offer coaching

sessions as well as provide equipment and our Director of Music’s expertise to expand their practical experience of teaching.’

‘It’s a two-way process, where our choir benefits but also the students get really beneficial feedback. Our Director of Music can give them advice on the process, help them reflect on their learning and develop their coaching skills.’

Lacy says they have seen a positive universal uptake from the choristers as well. ‘There was a little bit of doubt to begin with,’ she admits, ‘but every single member has given us positive feedback and have said they have learnt a lot from the experience.’

The options for the future of the project are either to continue funding out of church resources or collaborating with RNCM and incorporating this opportunity as part of their course. The students would then get credits towards their pedagogy module rather than a financial payment.

Lacy says: ‘Although we’re not a cathedral, we aim to offer cathedral style worship. We may be an amateur choir but we’re aiming for that perfect sound. We have people from all walks of life, ages, backgrounds that come together and contribute to this path towards it. Achieving a high quality of music but also broadening access to the choir and extending our reach to people who don’t necessarily have a background in church music is at the forefront of this project.’

Guildford Cathedral received a grant of £6,600 to support their Schools’ Evensong Project

When Guildford Cathedral began its Evensong programme aimed at schools, it was hoped that through it the music team could inspire confidence in singing together as a group, and for young students to experience the magic of the cathedral’s space.

The project was initially piloted during the academic year 2023/24 with a local state secondary school and sixth-form college. Throughout the pilot, it was clear that the students and staff were keen to experience more of what Evensong offers: the chance to sing beautiful music and to be part of something bigger. ‘As we have interspersed our lay clerks amongst the students, they have felt more empowered in what they are doing,’ says Katherine Dienes-Williams, Organist and Master of the Choristers at Guildford Cathedral. ‘We hope that the schools with which we work will be inspired to a continued interest in church music and may want to approach other venues to sing Choral Evensong as a visiting choir,’ adds Rebecca Cunningham, administrator of the Schools’ Evensong Project.

The funding from the Trust was offered over two years to expand the opportunity to a current total of six schools, and involve

them in other concert opportunities within the cathedral. Cunningham explains that this project is just the start of the cathedral’s outreach ambitions: ‘We aim to become a partner school with the Surrey Music Hub as part of that effort, alongside working with the Trust.’

‘The services have been extremely popular,’ Dienes-Williams continues. ‘The Quire is full of parents, supporters and regular worshippers.’ Following the most recent Evensong, students from Farnborough Sixth Form College were asked to describe their experience of singing alongside the full-time cathedral choir: ‘It fills you up with a feeling that’s quite indescribable,’ one of them said. ‘I felt very lucky to have the opportunity to take part in something so special... A lot of music students like myself would pay for a similar experience,’ said another.

Looking ahead, one of the biggest hopes for the music staff is to grow the cathedral’s visibility within the musical community: ‘By engaging with Surrey Music Hub we hope to become part of the regional offer in schools, as we know that there is a hunger out there for the experience we are offering,’ concludes Cunningham. ‘Seeing the student engagement with the process, culminating in their own Evensong with our full choir, supported by the professional lay clerks, our changed voices (former boy choristers) and the girls’ choir never fails to be uplifting for everyone involved – me included.’

Leeds RC Cathedral received a grant of £29,500 to support the Cathedral’s choral and organ scholarship programme

‘We’re really delighted to have the support from the Cathedral Music Trust’ says Thomas Leech, Director of Leeds RC Cathedral’s Schools Singing Programme. ‘It’s been really invaluable over the years having this relationship which allows us to offer as much as we can to the children we’re working with.’

The programme works with over 7500 children a week in 75 of the Diocese’s schools. It is this outreach into the community which is at the heart of Leeds’ work. ‘We’re not seeing children who have had prior exposure to cathedral music or children who have

previous knowledge or a cultural background of choir singing,’ Leech explains. Through these sessions Leeds Cathedral Choir introduces the students to choral music and then offers places into their choirs to any students who show enthusiasm and aptitude, regardless of skill level. ‘It’s our job to put the skills there; it’s not the children’s responsibility to know anything, it’s for us to give them the opportunity to learn.’

It is the ‘unevenness’ of opportunities which Leech describes that the Cathedral’s Schools Singing Programme wishes to combat. ‘Some of the schools are drawing their catchments in the worst one per cent of poverty in the UK, and these kids have the potential to really engage with music at a high level, but the opportunities are so uneven.’

Leech continues: ‘Choristers at King’s College Cambridge or St Paul’s are getting a

huge number of resources thrown at them as a result of being a chorister, and we just don’t have access to that financially. So, with the Trust helping us, we can really develop these opportunities for the children and fulfil that potential.’

The opportunities on offer for Leeds Cathedral Choir are indeed impressive: collaborations with singer-songwriter Gabrielle and The Sixteen as well as BBC Radio 3 and Radio 4 recordings. ‘These are the opportunities that then give those children confidence and experience within the musical world. Regardless of what pathway they follow, this will equip them for later life.’

Leeds Cathedral has seven choirs – a pyramid from the Cathedral Children’s Choir (for KS1 children), the Junior Boys and Junior Girls Choirs, Senior Boys and Senior Girls Choirs, Schools Scholars (emerging tenor and bass singers) and Choral Scholars (students in higher education in the city). Then there are a further 12 after-school choirs meeting weekly across the Diocese.

All choristers – and Choral Scholars – have either individual lessons or group coaching (in the junior choirs) through the Trust’s support, as well as having the opportunity to develop conducting and leadership skills (the

older choristers/choral scholars) and organ lessons (organ scholars/choristers). Leech explains: ‘The money from the Trust allows us to really advance the choral scholarships we offer. Our core funding goes into our programmes, because it’s an investment into the future of the cathedral choir, but we don’t generally have very much for resources beyond the day-to-day staffing. That’s why this money has been really transformative.’

‘In fact, two of the choral scholars have now developed enough so that they’re delivering professional work for us. One of our choral scholars conducted in our Remembrance Day concert and is now working with our junior choirs. She works with the seven and eight-year-old girls and gives them a role model. And that’s what’s so important. If you don’t see someone like you achieving it, it’s very hard to imagine yourself in that world.’

‘Our scholarships are not just about getting children into choral music, but a long-term investment into these children, whatever their professional path may be.’

For more information on the Trust’s grant programmes and on recipients of awards, visit www.cathedralmusictrust.org.uk/programmes

Choristers continue to bring sacred music to life in cathedrals and Choir Schools across the UK. But with the government’s removal of private school VAT exemptions, a number of these institutions face uncertainty

By ROBERT GUTHRIE

How can it be that so many child choristers in the British Isles still uphold the tradition of daily sacred choral singing that first developed here around the seventh century?

Amid social media, growing faithlessness and reduced funding, the fact that they number over 3,000, according to Cathedral Music Trust’s 2023 Chorister Survey, is a wonder.

But it is perhaps explained by the existence of a unique choral ecosystem comprising not only parish choirs and a range of local-level school partnerships but also nearly 40 choir schools, attended by around 1,000 choristers.

‘We maintain 40 choristers: 20 boys, 20 girls,’ says the Revd Canon Andrew Stead, Precentor of Lichfield Cathedral. ‘We make sure it’s absolutely clear in terms of equality.’

The boys’ and girls’ choirs sing on respective Tuesdays and Wednesdays while alternating Fridays and Sundays, with the senior choristers of both choirs singing on Thursdays. All choristers, aged 7-13, attend

Lichfield Cathedral School, an independent day choir school.

‘It’s a game-changer to have everyone in one place and wraparound care that works in conjunction with the cathedral and the school,’ says Ben Lamb, Director of Music at Lichfield Cathedral. ‘It also means that we can have daily rehearsals before school.’

‘We’ve attracted a more diverse range of people since we moved to being a day school,’ Lamb adds. ‘Even though we offered a massive offset to fees when it was a boarding school, I think that it was still seen as a barrier by a lot of people that their children would have to go and sleep somewhere else.’

The cathedral and cathedral school also take music beyond the choir stalls through MusicShare, an award-winning outreach programme involving collaboration with The Music Partnership, which supports four West Midlands authorities. ‘It reaches tens of thousands of children,’ says Susan Hannam, Headteacher of Lichfield Cathedral School and a Trustee of the Choir Schools’ Association. ‘There’s been enormous underfunding for years in music education in the state sector.’

The programme runs music projects with 150 primary, secondary and SEND schools annually and has received Department for Education and Arts Council England funding. Workshops involve current and former choristers as ‘Young Singing Leaders’ and culminate in schools giving a concert in the cathedral. ‘This tradition of English choral music is so important,’ Hannam says.

‘Culturally, artistically, musically and historically, it’s so rich.’

Westminster Cathedral epitomises that too.

Aged 8-13, its 20 boy trebles sing five times weekly for its Roman Catholic liturgy.

‘We live and breathe the liturgical year through sacred music,’ says Simon Johnson, Master of Music at Westminster Cathedral. ‘Recently we made a new album. In March we went to the USA. The week before that we sang JS Bach’s St John Passion. In April we commemorated the 500th birthday of Palestrina with a concert in Palestrina and in June we’ll travel to Hungary. This is all within a six-month period and is not unusual.’

Westminster Cathedral’s choristers attend the independent boys’ Westminster Cathedral Choir School, and have boarded from Sunday to Friday since 2019. ‘Choir boarding, with choristers on site, makes it easier to rehearse,’ Johnson adds. ‘There wouldn’t be enough time to fit in rehearsals and services, music practice and instrumental lessons, homework and school activities if there was an unpredictable London commute thrown in.’

‘The advantages of being a choir school are that choristership becomes holistic, encompassing: musical education; personal development, including teamwork, responsibility, perseverance, confidence, resilience, a strong work-ethic and attention to detail; and a fully immersive engagement with a rich repertoire including, in our case, much outstanding polyphony and plainsong, and within a community of choristers from many backgrounds.’

St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh, is Scotland’s only cathedral to sing regular choral weekday services. Choristers sing Evensong on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays, as well as two services on Sundays, and rehearse every

morning from Monday to Friday. Lay clerks alone offer Evensong on Wednesdays.

‘The ‘choral tradition’ is far less well-known in Scotland and so it is always even more a priority to let people know about the opportunity to be a chorister, choral scholar or lay clerk, or to drop in and listen to Choral Evensong,’ says Duncan Ferguson, the Cathedral’s Director of Music.

The cathedral’s current 15 choristers attend St Mary’s Music School, Scotland’s only independent specialist music school, which is day and boarding. ‘It enables joined-up timetabling and planning, which helps maintain the routine of regular weekday services,’ Ferguson adds. ‘There is also the proximity of the school, with all the choristers needing to be at the same place at the same time.’

Cathedral musicians continue to reach new audiences. St Mary’s is home to Benedicite, a youth choir launched last year, and there’s a primary-school singing programme and nursery-age singing classes. ‘The interest that is generated in the building and its music can only strengthen awareness of weekday choral services and the cathedral choir,’ Ferguson adds.

While many choir schools are independent, there are a few institutions like Bristol Cathedral Choir School which became a state-funded academy in 2008. Eight choristers from across the city join annually as probationers for years five and six, becoming full choristers for years seven to nine.

Bristol’s 21 boy choristers sing Evensong on Mondays, while its 20 girl choristers sing on Tuesdays. The choirs combine for Wednesday Evensong, alternating full Sundays. Probationers rehearse in respective groups in ▷

the afternoons while full choristers rehearse mornings from Monday to Friday.

‘We make extra time for the probationers in the afternoon,’ says Mark Lee, Director of Music at Bristol Cathedral. ‘They all have a half-hour’s dedicated time before the other choristers join the afternoon rehearsal.’

‘There’s no bar to anyone being a chorister as long as they have musical skills,’ Lee adds. ‘The fact that the school is much bigger is helpful. Music is very highly regarded. We have made massive efforts for the choir and school to function together really well. It’s a proper partnership.’

However, the state model requires careful prioritisation. ‘There are trade-offs,’ says Dr Wade Nottingham, Headteacher of Bristol Cathedral Choir School. ‘We don’t offer necessarily the range of subjects you would see in other comprehensive schools, so that affords us the additional provision for choristers and music.’

Might more independent choir schools turn state-funded? ‘Who knows what will happen following the changes to the VAT?,’ Nottingham says. ‘That avenue may become more attractive.’

Or might they diversify links with state schools? Leeds Cathedral’s choristers come entirely from state schools recruited through the diocesan Schools Singing Programme while Canterbury Cathedral announced in 2023 that its boys’ choir would open to children from other schools.

Costs have risen for independent choir schools since the UK government abolished the 20 per cent VAT exemption on independentschool fees in January. The Department for Education says funds will ‘improve standards and opportunities for the nine out of 10 children who attend state schools’.

It adds: ‘We don’t expect that raising VAT will cause private school fees to go up by 20 per cent. This is because private schools don’t have to reflect the VAT increase in the amount fee payers are charged. On average, we predict the measures are likely to see fees rise by around 10 per cent.’

‘It will be some time before the full effect of the tax is known, as it will influence parental choice for years to come’

But Hannam of Lichfield Cathedral School describes this notion as ‘absolute nonsense,’ saying that they have managed to offset about one per cent. Parents will pay the remaining 19 per cent. Choristers will still receive cathedralfunded bursaries of at least 20 per cent. She adds that while their January ‘Be A Chorister For A Day’ workshop was ‘hugely well attended,’ several prospective families for general school entry last September ‘disappeared into the ether’ following the VAT news.

Edinburgh’s conclusions are similar. While the Scottish Government Aided Places Scheme covers 100 per cent of a few choristers’ fees, others receive a cathedral-funded bursary of at least 33.3 per cent, with parents paying the rest. St Mary’s Music School’s Dr Kenneth Taylor says: ‘We’re fortunate that the Scottish government is able to pay the VAT on its contributions.’ But he says that the school had ‘no option’ but to increase fees by 20 per cent. ‘It’s fairly obvious that if you increase fees you are going to automatically decrease diversity.’

The Very Revd John Conway, Provost of St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh, says: ‘The cathedral has agreed to pay the VAT on its contribution. That will add between £12,000 and £13,000 per annum to our costs. The rise in VAT threatens to undermine what we can financially offer to those from challenging socioeconomic backgrounds.’

Neil McLaughlan, Head Master of Westminster Cathedral Choir School, says: ‘It will be some time before the full effect of the tax is known, as it will influence parental choice for years to come.’

As Hannam of Lichfield concludes: ‘Some families have never considered independent schooling. We try hard not to allow finance to be the reason why a child with potential and a supportive family can’t do it. The English choral tradition is a beautiful and precious thing that needs the people who are working hard to keep it going.’

The Trust will be exploring multi-school cathedral choirs in the next issue.

By CHARLOTTE GARDNER

ALDEBURGH FESTIVAL

June 13-29

Choral highlights include Blythburgh Church playing host at sunset to EXAUDI’s first live performance of its Book of Flames and Shadows programme. Another is the BBC Singers and Chief Conductor Sofi Jeannin with lockdown and liberation-themed works by, among others, Britten, Poulenc, Musgrave, plus festival featured artist Daniel Kidane’s The Song Thrush and the Mountain Ash brittenpearsarts.org

BATH FESTIVALS

May 17-25

A celebration of books and music mixing inspirational speakers, consummate storytellers and music in Bath’s historic churches. Bath Music Festival’s choral jewel

As the UK prepares for a summer of music festivals, we highlight some of the finest choir concerts throughout the season, to be found in urban arts centres, cathedrals and rural churches alike

for 2025 is The Marian Consort under Rory McCleery bringing its William Byrd: Singing in Secret programme (including Byrd’s Mass in Four Parts) to Bath Abbey. bathfestivals.org.uk

FESTIVAL

May 3-26

England’s largest curated multi-arts festival this year welcomes Harry Christophers and The Sixteen to perform a programme juxtaposing music composed by a 12th century German abbess, with the ‘holy minimalism’ of Arvo Pärt, plus two contemporary British pieces. Another choral highlight sees the Brighton Festival Chorus join the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra for a nature-inspired programme. brightonfestival.org

ABOVE Blythburgh Church will host one of Aldeburgh Festival’s standout concerts: the first live performance of EXAUDI’s Book of Flames and Shadows

Cheltenham Music Festival celebrates 80 years in 2025, with choral music centre-stage

July 10-27

Concerts running alongside the opera programme this year include The Tallis Scholars bringing a programme pairing the works of 500th anniversary composer Palestrina with those of Victoria. buxtonfestival.co.uk

July 4-12

Cheltenham celebrates 80 years in 2025, with choral music centre-stage. Berlioz’s Te Deum at Gloucester Cathedral, the sacred music of Orlando Gibbons at the Pittville Pump Room, and Mozart’s Requiem at Cheltenham Town Hall all feature. Top-flight performers include Dame Sarah Connolly and the Choir of Merton College, Oxford. cheltenhamfestivals.org

June 14-July 20

May 12-24

Always a festival to make a springtime beeline for, Chipping Campden’s choral highlight this year is Tenebrae’s May 19 concert, I saw Eternity, in St James’ Church – a dramatic programme contrasting JS Bach’s motets with the sacred music of Sir James MacMillan. campdenmayfestivals.co.uk

May 24-26

Based at Dunster Priory Church, the Somerset festival this year has the transcendent voices of The Marian Consort celebrating Palestrina’s 500th anniversary, and joining period instrument ensemble Spiritato for the all-Bach Festival Finale. Other events include an afternoon cream tea concert, a late-night vocal recital, a choral workshop and an inaugural Festival Fete with children’s entertainment. dunsterfestival.co.uk

May 24-June 1

Celebrating Elgar’s legacy in the places that were familiar to him, the Worcestershire festival this year has the English Symphony Orchestra and Festival Chorus filling Worcester Cathedral for a special gala concert with Elgar’s Symphony No 2 and John Ireland’s ‘These Things Shall Be.’ Also celebrated is the 70th birthday of Worcester’s finest living composer, Ian Venables. elgarfestival.org

June 11-15

ABOVE The Choir of Merton College, Oxford are among the top-flight visitors to the Cheltenham Festival

This multi-arts festival’s 2025 classical music programme notably features Chichester Chorale concluding its 20th anniversary celebrations by singing Vivaldi’s Gloria and Buxtehude’s Magnificat, among other works, at Boxgrove Priory Church. Also being celebrated is Orlando Gibbons’s 400th anniversary, through Portsmouth Baroque Choir presenting a viol consort-accompanied concert of his and his contemporaries’ music. festivalofchichester.co.uk

Based in Bridgnorth’s 18th-century Church of St Mary Magdalene, this festival’s periodinstrument English Haydn Orchestra is led by Simon Standage and conducted by Steven Devine. Its major choral event, on 15 June, is Joseph Haydn’s The Creation, featuring soprano Ana Beard Fernandez with Covent Garden Opera singers, tenor Timothy Langston and bass Eugene Dillon Hooper. englishhaydn.com

September 18-21

Praised for its ‘superb combinations of sound and vision’ [Vox Carnyx], in the city’s 850th anniversary year, the Glasgow Cathedral Festival is celebrating community and innovation. There’s a world-premiere commission from Roxanna Panufnik. Roger

Sayer’s Interstellar 10 showcases the majestic cathedral organ, and Fritz Lang’s iconic 1927 film Metropolis is screened with a live score by Cork composers and sisters Irene and Linda Buckley. gcfestival.com

August 17-24

This year’s honouring of the Welsh tradition begins with the festival-opening Cymanfa Ganu, a traditional festival of sacred hymns, with Côr Meibion Aberystwyth. Famed Welsh male voice choir Côr Godre’r Aran also visits, as does Côr Bro Meirion with a performance bringing together the worlds of Welsh and classical music. moma.cymru

June 26-July 13

If you’re yet to see Gaia, Luke Jerram’s touring 3D art installation depicting our planet, visit this eclectic festival for 10 days, at St Wilfrid’s Church, with one especially atmospheric opportunity to experience it at a candle-lit concert by The Marian Consort who will sing underneath it. harrogateinternationalfestivals.com

July 3-13

Set across the medieval churches of Kent’s Romney Marsh, just one hour from London, JAM’s eclectic 2025 programming includes three concerts celebrating Coronation composer Paul Mealor’s 50th birthday, including the BBC Singers performing the UK premiere of his The Light of Paradise for choir and saxophone quartet, and The Chapel Choir of Selwyn College, Cambridge with The Farthest Shore jamconcert.org

August 1-10

Lake District Music celebrates its 40th birthday this summer with a couple of notable choral highlights. Kantos Choir performs its Elements programme, complementing works such as Katerina Gimon’s Elements and Herbert Howells’s Take Him, Earth, for Cherishing with poetry and prose. Then Beethoven’s ‘Choral’ Symphony No 9 is paired with his ‘Emperor’ Piano Concerto No 5. Paul Lewis is the soloist. ldsm.org.uk

May 12-July 14

Featuring Leeds Cathedral’s four-manual Klais organ and some of the finest players from around the world, this festival presents admission-free Monday lunchtime recitals (with a retiring collection, and excepting May 26), and this year includes David Pipe giving a children’s recital as part of the Royal College of Organists’ Play the Organ Year 2025. leedsiof.org

July 8-20