Alternative visualisations

are needed to initiate this switch from an 'outsider' to an 'insider' position

to support way-finding, (un)learning, and different ways of relating. It describes four principles: augmented senses for noticing nonhumans, interaction as flux between actors, zooming in and out on nonhumans, and mapping invisible habitats. Research results derive from the main case study: the Arts & Interaction minors programme at St. Joost.

Preface

‘Humans are atmospheric beings, particles, dust, involved in intimate cycles of exchange, actors with an incredible force. We need to become attuned actors with a deeper understanding of all the other particles.’

‘Even though it is intrinsically intangible, dust can expose other invisible forces. It makes rays of light, or currents in the wind and water, materialize. Dust reminds me of the importance of these natural resources. It reminds me of the role of design. Design can reveal invisible but elemental actors.’

— Annemarie Piscaer (2017)

6 | Abstract 7

dust

floating in the light

Dear reader,

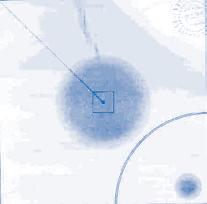

The Pale Blue Dot, an image taken by the Voyager 1 Spacecraft on 14 February 1990, has great significance for those who are fascinated by dust as a material. The image shows planet Earth from a great distance. From this long perspective our planet looks like a small, fragile particle of dust in an immensely vast space. The famous Blue Marble image, taken by the crew of Apollo 17 in 1972, represents the first photograph in which Earth is in full view: it ‘zooms in’ on that pale blue dot. Blue Marble was the first image to invoke what is known as ‘the overview effect’, a significant milestone for the environmental movement, wherein images of Earth from space enable people to perceive it as a fragile ecosystem. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges we humans currently face. It affects our immediate habitat: heating ecosystems, destroying biodiversity, and more. These changes are happening particularly rapidly and intensively in the Global South. In this respect, climate emergency exacerbates existing inequalities between the Global North and the Global South. The former is primarily responsible for causing the crisis, while the latter faces the harshest consequences.

This is a catastrophe that requires us not only fundamentally to change our systems, our habits, and our desires, but more importantly, also to amend our self-image and to acquire humility in our relations with human and nonhuman others. These necessary changes will remain difficult for as long as views that separate the human from the planetary dominate. We need to move from an anthropocentric worldview

This requires us to to amend our selfimage and to acquire humility in our relations with human and nonhuman others

“Pale Blue Dot” taken by the Voyager 1 Spacecraft, on February 14, 1990

milky way

A role for design and design education is to create embodied knowledge that not only enables cognitive understanding but is also experiential

to a post-anthropocentric worldview, from an outsider perspective to an insider perspective… farewell to the Blue Marble. Bruno Latour calls this insider position being earthbound. Alternative visualisations are needed to initiate a switch in perspective. This is a role for design and design education. To create embodied knowledge that not only enables cognitive understanding but is also experiential. To shift away from an understanding of the human as separate from the environment, and move towards a feeling for human entanglement with other interrelated oddkin (Haraway, 2016). A family of actors: some expected, but many more unexpected; familiar and unfamiliar; known and unknown; logical and illogical; convenient and inconvenient. Approaching the garden of St. Joost as a living learning lab assumes that creative practices can learn from nature. However, following Latour’s argument that there is no distinction between culture and nature, this learning emerges from the mergence — or collapse — of subject/object divides. What does this mean for design education?

This pedagogical guide based on case studies outlines how more-than-human perspectives can be implemented in design education curricula. It is not a set of fixed rules, it is open to multiple interpretations. The more-than-human is a general concept that emphasises the inseparability of humans and nonhumans – the various actors. This more-than-human

| Preface

view dances around all actors, but our research, which contextualises the academy’s garden, has a particular interest in the living actors of invisible habitats.

This document sets out four principles: augmented senses for noticing nonhumans, interaction as flux between actors, zooming in and out on nonhumans, and mapping invisible habitats.

Note: I attempt to avoid the word ‘I’ wherever possible. Where it is used, i will not write it in capitals.

...to cultivate the wild virtue of curiosity, to return one’s ability to sense and respond -and to do all this politely!

2016, p.127

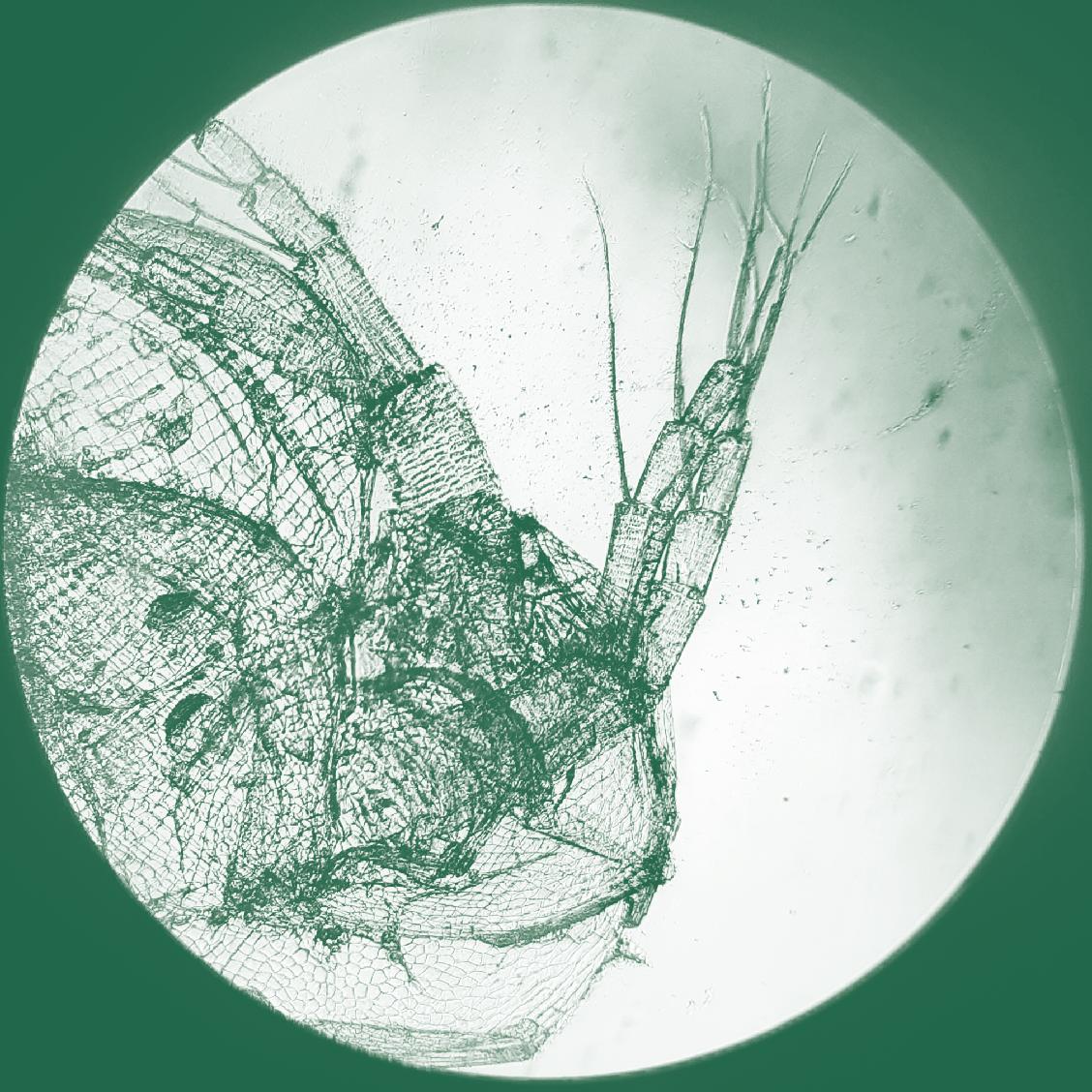

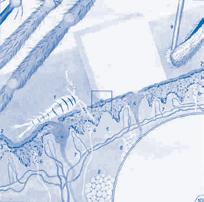

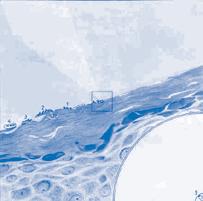

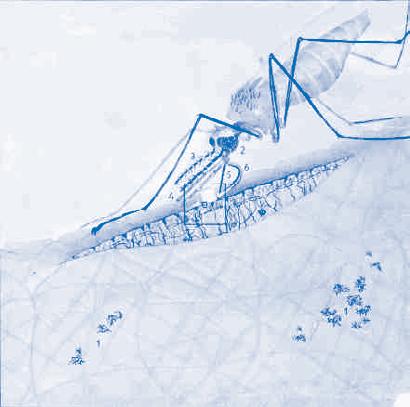

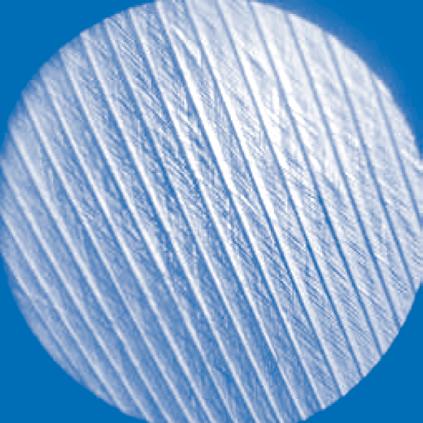

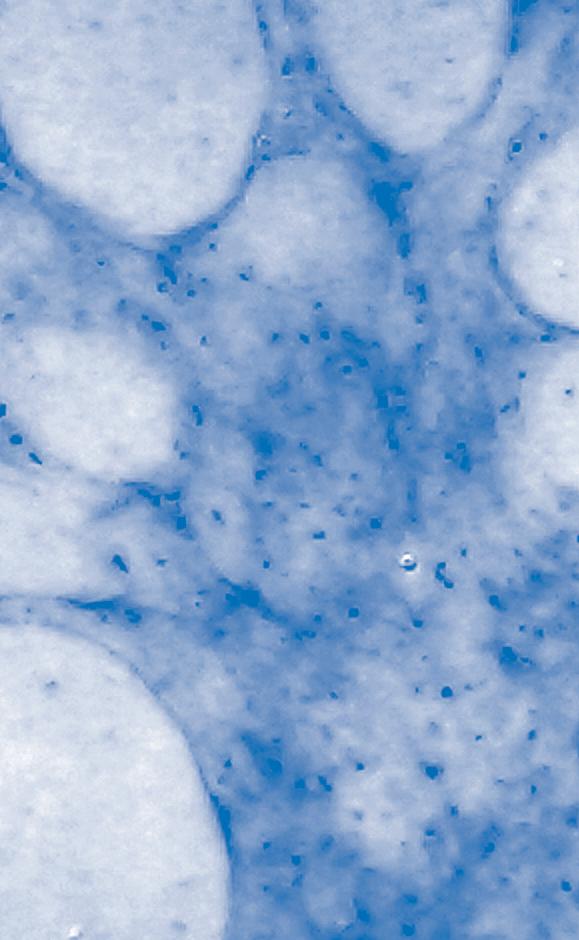

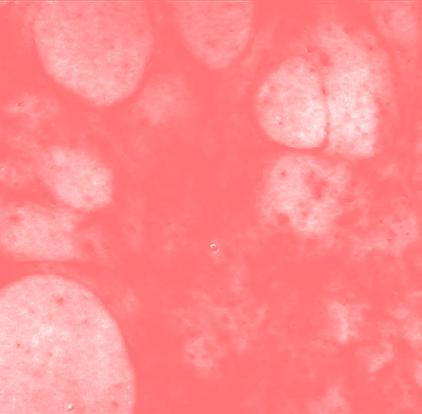

Students found a leaf beetle and observed it under a microscope.

Haraway,

Introduction

‘The Garden as a Living Learning Lab, a Living Sensor. The Garden that Sees, Smells, and Hears’ is a project in the Biobased Art & Design (BAD) research group at Centre of Applied Research for Art, Design and Technology (Caradt). The research project aims to initiate a living learning laboratory in the garden of St. Joost School of Art & Design in Breda.

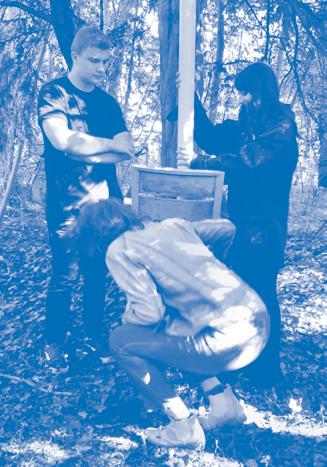

Research results derive from the main case study: the Arts & Interaction minors programme at St. Joost School of Art & Design in Breda. 25 students from a range of disciplines and art academies across the

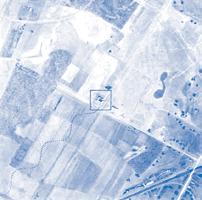

The academy building is situated in the middle of the garden. The front side hosts the official entrance, a neatly maintained area, with classic shaved hedges. Further back, there is a bigger entrance, including parking spots. Here students mostly enter the school. The back side is wildered a low maintained area, with a big variety of high trees.

Netherlands participated in an assignment, ‘Agency to the Actors’, which involved creating a group project over a three-month period. Students were asked to map and visualise the garden’s different actors, their relations and interactions. The students explored the perspectives and agencies of these actors, and created five performative group works for the garden.

Living learning laboratory

In its present state, the garden of St. Joost Breda may appear classically ‘perfect’, its lawn and plants neatly mown and maintained. It stands separate from the academy as such. Education is understood to be something that happens inside the building and the garden functions merely as an aesthetic green surrounding, a place for pastimes. In this respect, the garden is viewed as a place that is menial to our needs. However, this perspective is limited to the human. It is arguably the dominant mode of relating with this ecosystem, which can more broadly characterised as the sum of all relationships, via reference to the three ecologies that were outlined by Félix Guattari: the environment, social relations, and human subjectivity How might we develop dynamic, reciprocal relations with this garden’s actors? What roles can humans play in the ecosystem here? Who and what are the other actors, and how do they interact? Can they see, smell and hear – or are these human modes of perception? How can learning be an entity or actor in this ecosystem? What knowledge emerges here? In what way does this knowledge manifest as an actor? How might we integrate sensitivity to more-than-human viewpoints into higher education?

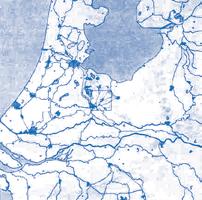

coastal line

About the garden

The garden is more than just a garden. This guide can be transferred to other situations and locations. However, as stated above, its situated context matters. The Academy St. Joost Breda is located in a building which was originally a small castle, the Ypelaer, constructed in the late Middle Ages. Centuries later, around 1878, it was rebuilt as a small seminary, ‘Klein-IJpelaar’. The garden was then used for producing food, as seen in the picture, until around 1970. The old lanes from the castle can still be made out on the ground and it is likely that some trees in the garden originate from the 1878 reconstruction. In 1944 the seminary burned down and an exact replica was reconstructed on the site. Due to the rich archaeological history of the location, digging more than 30 cm below the surface of the garden is not permitted. An interesting note on an official Municipality of Breda document stipulates digging ‘no deeper than 30 cm, even if the area is less than 100 m², is permitted. This rule should not only be set out on the municipality’s policy map, but also actively communicated to the Avans University of Applied Sciences so that unintentional disruption caused by excavation activities events resulting from school projects can be avoided.’

The notion of learning as an insider, contextualised in this garden, relates to Haraway’s situated knowledges, wherein a learner cannot be seen as separate from the learning environment. Therefore the ‘Agency to the Actors’ assignment required students to map the actors in the garden and to create a performative piece in which they themselves would take an active role.

garden especially on the north side you hear traffic from the Franklin Rooseveltlaan. On the south east the garden is connected to a more quiet zone.

Case study

The project’s approach to the garden as a place for learning is inspired by John Dewey’s pedagogical ideas concerning learning while doing, which Dewey developed at Black Mountain College. This liberal arts college, established in North Carolina in 1933, has been an inspiration for other Modernist arts educational movements. The college was known for embracing its natural surroundings as a learning environment and for incorporating the environment into the curriculum. It was place for practice and experimentation. Students worked in the college vegetable gardens and created experimental land art. The Garden Department at the Dutch Rietveld Academy could be considered a new iteration of this pedagogy. The Garden Department is a student-led, self-organising initiative which uses the Academy’s garden as an outdoor classroom. Students grow vegetables and explore gardening principles such as permaculture.

The college was known for embracing its natural surroundings

Both these gardens – at the Garden Department and at Black Mountain College – are utilised for human purposes. Our case study, however, focuses on a morethan-human view.

‘Atelier LUMA investigates the many layers of the bioregion. We gather loose historical, cultural, environmental, social, economic elements, and weave them together into potential projects.’

— Jan Boelen, artistic director of Atelier LUMA

Another source of inspiration for ‘The Garden that Sees, Smells, and Hears’ was Atelier LUMA, an educational project currently running in Arles, France. Atelier LUMA also approaches its surrounding landscape as a living learning environment – a bioregion. It involves mapping the invested actors who are at stake, and draws on local resources and know-how to respond to social, economic, ecological, and cultural challenges. Designers play a vital role: working from within, they map and investigate the various actors through the development of real-world projects. These projects can be seen as samples or material for the ongoing construction of knowledge networks. Materials or matter from the region are intrinsic to their maps of local stakeholders.

The Eco-Nomadic School (among others that are facilitated by Kathrin Böhm) brings together learners within local conditions and a situated context. The school is a network of locally situated projects from across Europe which come together to investigate living learning networks. Participants visit one another to learn, teach, share, and discover the knowledge held

in their communities. This is a non-institutional and non-hierarchical approach to learning. As Böhm says, what is crucial, in ‘learning to act’, is that ‘the roles of learner and teacher are interchangeable. The same applies to the roles of specialist and amateur, local and incomer, doer and speaker, researcher and maker.’

The Floating University also works with a non-institutional framework in a situated context. This ‘natureculture learning site’ was established in 2018 as a self-organised, non-disciplinary space and group, working onsite at the former Tempelhof in Berlin. ‘It is a place to learn to engage, to embrace the complexity and navigate the entanglements of the world, to imagine and create different forms of living – or what we also like to call Fields of Knowledge and Action: from maintaining and developing the site to gardening, cultivating collaborations, and taking care of neighbourhood connections.’

‘The meanwhile begins: fields and grass grow back and animals return to paths they used to traverse for their seasonal needs. What may remain from visit to visit are these fragments that will be recognised by the next arrivals who carve out their own routes in the landscape, modestly creating new traces of inhabitation. This slowness averages during these visits in contrast with the places travelled from.‘

— Kristina

Kotov, Artistic Director, LT Ranch

The LT Ranch project also influenced our case study at St. Joost. A non-for-profit, remote art space in northeast Lithuania, LT Ranch hosts seasonal student

sessions with design / architecture Masters students from the UK. The Ranch is also a facility for ad hoc yet considered residencies concerning the landscape. These can include spontaneous spatial research, experimentation, and cultural events that are related to art, architecture and film. Projects developed by students are characteristically non-invasive and flexibly responsive to the landscape that they read. Summer sessions begin with a pedagogy of listening. Walking in the landscape, listening in near-silence, adopting humility when approaching the landscape: not learning from but learning with. This attitude can be viewed as a pedagogy – of learning as equals, as described in Jacques Rancière’s 1991 book The Ignorant Schoolmaster. While Rancière outlines what ‘learning as equals’ can mean in the human context, his pedagogy can be contextualised for a much wider company of actors (human and nonhuman) with the LT Ranch approach – and so too with that of Atelier LUMA, The Eco-Nomadic School and the Floating University.

Walking in the landscape, listening in near-silence, adopting humility when approaching the landscape: not learning from but learning with

LT Ranch, Atelier LUMA, The Eco-Nomadic School and the Floating University all work from situated contexts. They map local conditions while working cooperatively and with a premise of equality on small-scale projects. Each of these elements is central to this project’s main case study, ‘Agency to the Actors’. The challenge, for us, is to translate the non-institutionalised working methods outlined above into the formal setting of the case study.

amaryllis

In a more institutional context, Tom Emerson, professor and architect of Studio Tom Emerson, developed a garden project of 1300 m2 on the ETH campus at the University of Zürich. Emerson’s garden experiments with new models of learning. He describes it as a project ‘that does not have the parameters of a semester, school year, or degree course. Instead, like a science laboratory, it is a framework for innovation over time. We will learn from growth and decay, the spectrum of natural processes, and the patina of time. Gardens thrive while architecture ages: our site will be an opportunity to explore this reality first-hand. We are the pioneers of this new garden. We will dig holes, realise the weight of soil and the speed at which grass grows. It will change your relationship to nature.’

Thinking about this in the context of our case study –which runs for one semester – means acknowledging that we will need further cycles of case studies if we seek a deep understanding of this ecosystem in which learning is situated. As a continuation of the research, therefore, our central case study, ‘Agency to the Actors’, will be followed by a series of smaller workshops and experiments that take place on an ongoing basis.

Arts & Interaction minors programme

The ‘Agency to the Actors’ assignment was shaped in alignment with the expertise of the tutors on the minors programme (tutors come from several disciplines including Philosophy, Interaction Design, Art & Technology, and Immersive Design). Some 25 students were assigned a project of three months’ duration and asked to use this period to develop an interactive experience that was based on giving agency to the actors in the garden. The outcome of the group

projects was to be situated in the garden itself. They were required to map and visualise these elements and their interactions, and to give agency to the actors. By observing, looking in detail, analysing, and mapping what happens, the researchers would allow the actors to reveal their own narratives. This was intended to create a found image in new, high-resolution detail, which was to be translated into a final project.

The case study was reviewed through qualitative interviews with both students and tutors. There was peer observation during classes, and post-project review of the students’ documentation and reflection processes.

Conclusion

The case study clarified four principles: augmented senses for noticing nonhumans, interaction as flux between the actors, zooming in and out on nonhumans, and mapping invisible habitats. These will be described in the next chapter. Situatedness, cooperation, and learning as equals are not project principles but key learning conditions. The students had to work cooperatively in groups within the situated context of the garden. The case study revealed that it is a challenge to commission BA students to acquire an understanding of more-than-human perspectives over a learning period of three months. One of the five student projects, for example, operated from an entrenched human perspective, while the other four projects demonstrated a growing sensitivity to morethan-human viewpoints.

Situatedness,

cooperation, and learning as equals are not project principles but key learning conditions

Propaedeutic students work in the garden on a mapping assignment

Students of LT-Ranch performing in a self-invented pagan ritual.

LT-Ranch in Lithuania

Students of Blackmountain college working in the garden, around 1940. Courtesy image: Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina

Augmented senses for noticing nonhumans

‘Take a moment to draw a cosmic breath with your whole body, slower than any breath you have ever taken in your life. Close your eyes. See and hear with your skin as you embody the density that emanates from the seed of your thoughts…You are in an endless state of communication and infinite contemplation with other natural elements and beings. Can you see with your skin and hear with your arms? Can you think together with the air and the sun and the soil? Can you dream with your feet? Imagine with your fingertips?‘

— Eduardo Navarro and Michael Marder, This book is a plant, 2021

As the above quote suggests, the senses are not separable instruments for perceiving the world. Senses intertwine, they are in flux and relate to one another. A sense is not a neutral medium for establishing the truth. Your senses do not merely enable you to notice invisible habitats (this could be understood as a cognitive process), rather, they enable you to become aware of yourself as a part of these invisible networks. The project principle augmented senses for noticing nonhumans is founded in the case study’s key findings, which can be outlined as follows.

Your senses do not merely enable you to notice invisible habitats, rather, they enable you to become aware of yourself as a part of these invisible networks

One of the tutors’ classes focused on sensing. As this tutor explains, sensing ‘plays a huge part in my classes. The human senses – tasting, smelling, hearing.’ The learning experience developed over two workshops which aimed to sensitise students and to augment their senses.

In the first workshop, students worked in pairs. They were asked to isolate a single sense. One student was then guided by their partner while walking through the garden with closed eyes, focussing on their chosen sense (smelling, hearing, feeling, tasting) and the experience it created in their own body. The body functions here as a material or vehicle. This workshop delivered immediate results and ultimately shaped the students’ projects. It enhanced the senses for tuning into the more-than-human. One of the students who created a project titled ‘Roots of Time’ described the role of the senses in its development: ‘the senses brought people back into their own bodies. Feel time. Touch or listen to the tree and the pond. Our project integrated these experiences with a tour which involved walking once around a pond without stimulating the senses. Participants then took a second turn around the pond, during which we did stimulate their senses. Opening your senses is necessary, and the garden is very good for that. You feel a desire to touch the grass, to smell nature, the wetness, and so on. Our participants told us that they experienced time differently after our workshop.’

The second sensing workshop was a performative session focused on presence. The tutor asked students to develop an awareness of the ‘aura’, to consider the tension between self and other. Students were instructed

to approach someone with closed eyes and to notice the point at which they could feel the other person. This process was designed to instil an awareness of the physical body. The outcomes of the workshop also relate to another project principle – interaction as flux between actors – further elaborated below. One of the students who helped to create a projected titled ‘Fuck Nature’ describes the experience of the workshop: ‘I learned to get into a performative mode. You can use your body as a material as well. You are the material, just as everything else is a material. It makes you work in a particular and interesting way – with a better understanding of “the other”.’

You can use your body as a material as well; you are the material, just as everything else is a material

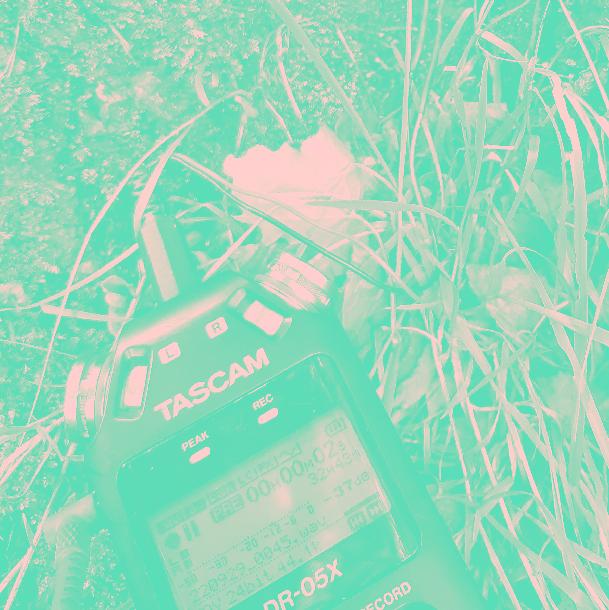

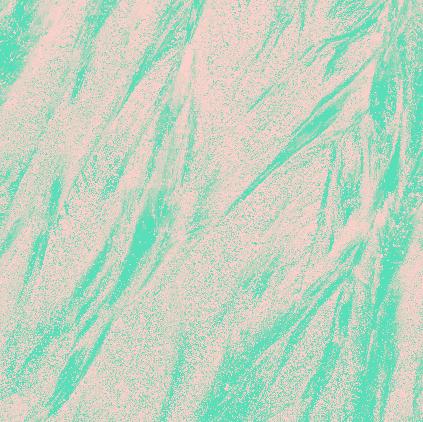

The ‘Whelve’ project can exemplify how this workshop influenced the students’ creative thinking. For ‘Whelve’, students placed a field microphone on a tree to amplify its sounds, and positioned participants as auditors of other living, unseen habitats and actors. You could hear the tree’s juices, its heartbeat, and feel its pulse of life. As one of the students explained: ‘This [can be seen] in contrast to the position of power that man often finds himself in, in relation to other life. This domination is visible and tangible in the garden of St. Joost, for example, in the treetops which have recently collapsed. The trees have been manipulated and modified by man to produce quick-grown timber. By now, weakened, they can no longer adapt to weather conditions. The trees, like humans, have become individualistic and cannot support each other through disease or drought. As a result, the forests are getting younger and breaking down on their own.’

Project ‘Whelve’, amplifying the sound

Project

‘Whelve’

Interaction as flux between actors

As we have seen, an actor is never static – it acts. Things are not merely fixed particles within an ecosystem but rather a mergence — or collapse — of subjects and objects: actors in flux, interacting. As the setting for the case study, the Arts & Interaction minors programme was the formative context for the students’ assignment.

‘Agency to the Actors’ fitted neatly with the rest of the minors programme and followed tutors’ expertise. Specifically, this meant guiding students towards developing an experience – an interaction. Interaction, translated into embodied experience, is not considered the end result of the project but one part of a process of learning to inter-act – to change positions – and what it means to understand or sense one’s own position. This, in turn, aligns with our understanding that the more-than-human view is not merely a cognitive process.

Things are not merely fixed particles within an ecosystem but rather a mergence — or collapse — of subjects and objects: actors in flux, interacting

The ‘Roots of Time’ student project focused on inter-active actor time. Students developed a meditative exercise that invited participants to find their own rhythm and pace: ‘During a walk through the garden, we experienced that we were mainly observing with

34 | Interaction as flux between actors

our heads and we realised we were not aware of all the actors within the garden. What rhythms and rituals take place in the garden? Are the trees moving? What processes are there that we don’t immediately see, which seem too slow for us? This insight made us revisit our own bodies and notice how we are not always aware of the signals our body sends. If we could listen more to the body’s own “inner clock”, we would find a better balance.’

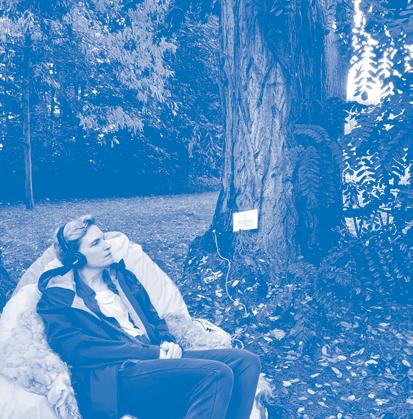

Students who developed a project entitled ‘Nature’s Bedroom’ created a different experience by inviting participants to lie alone in a bed in the middle of the Academy’s forest. This became a place where they could inter-act with the other actors – a process of learning how to connect, to engage, and perhaps even to let go. ‘We designed this project with the assumption that lying in a bed in a forest is not something people get to do every day. It can feel alienating. Our expectations were confirmed when we had people test our different prototypes. Participants’ responses included a sense of being humbled by nature, but also of being privileged to experience nature in this way. However, the experience will be different between participants: some people are used to letting go, while others are absolute control freaks.’

Prototyping: the project ‘Nature’s bedroom’

Another student project, ‘Fuck Nature’, exemplifies interaction as flux between actors in an interesting way. A student says: ‘Our group does not have the best relationship with nature. There are phobias and allergies, and also a prohibitive approach towards nurturing nature that derives from a desire to avoid demolishing or contaminating. Nature plays an important role in human life, but what happens if you become physically sick when you come up close to a forest? Nature is often romanticised by humans: nature is beautiful, gives peace, gives life. We do not agree with this. People forget that nature also brings disease, floods, fires, horror, vermin, irritation, discomfort, and fear. We want to offer an experience in which the participant questions the romanticisation of nature and to put the senses at the centre of this experience. How will we stimulate or prompt the participant’s senses, and instil a sense of discomfort, betrayal and fear? Can we push the boundaries of the other? We want to highlight the true nature of nature and its horror. We can increase the shock factor by gaining the trust of the volunteers. Breaking this trust then becomes our translation of how nature works. It is unpredictable and it does what it does. That uncertainty is what we are responding to.’

Zooming in and out on nonhumans

Thinking of zooming in and out may remind us of the famous Powers of Ten film made by Ray and Charles Eames in 1977. Powers of Ten shows the relative proportions of things, moving across scales by powers of ten from the microscopic to the cosmic. It is based on Cosmic View, a book by the Dutch engineer, educator and pacifist Kees Boeke, whose work relates to our project principle zooming in and out on nonhumans. Boeke believed that society could be reformed through the education of children and in 1926 he established a school, De Werkplaats, in Bilthoven. The school was a sociocracy with a curriculum that treated students and tutors as equals. Workshops at De Werkplaats involved undertaking domestic tasks inside the school and its garden, where the children grew vegetables and fruits. As a pacifist, Boeke believed that humans should be more humble in relation to the cosmos and he created an illustrated school workbook, Cosmic View, with this in mind. The idea for the book germinated in a series of workshop classes which were presented as part of an education exhibition in 1927. Cosmic View takes a voyage outward and inward from the familiar human scale, offering new perspectives and speculating on different levels of reality.

More recently, a creative initiative called Kosmica, based between Berlin and Mexico, bridges arts and humanities, the space sector, and wider society. Kosmica runs open and accessible educational activities such as workshops which take ‘insider’ approaches to contemporary planetary challenges. Almost a century after

insect on sigarette filter

Student: ‘This is a reason i would stop smoking, i’d inhale the burnt body of that sweety (!)’

Pages of the book ‘Cosmic View’ from 1957 by Kees Boeke. Notice that it starts in the Netherlands, Bilthoven, a girl in a chair in the garden with a cat. And that the picture before that shows a imaginary Whale, to get an understanding of its size, and ours smallness compared to it.

Powers of Ten, zooming in and out on nonhumans is not only a matter of space but also of time and context. Kosmica states: ‘As much as we need to discuss new ways to solve our challenges on Earth, we also need to be silent and listen. Throughout recent history, Western narratives have superimposed a single way of understanding the universe and our place in the natural world – narratives that silence ancestral wisdom’.

To contextualise these ideas via Latour’s Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (2018), the insider view does not mean thinking globally to work from a local position. Rather, to address climate change, we must work our way back into material relationship with the Earth. Latour argues that ‘the planet is much too narrow and limited for the globe of globalisation; at the same time, it is too big, infinitely too large, too active, too complex, to remain within the narrow and limited borders of any locality’. Our project principle zooming in and out on nonhumans works with this. Zooming in and out calls for a material canvas: a situated context from which to work. The garden of St. Joost functions precisely as such, whilst also being a sensorial canvas, as Kosmica suggests: a place of beauty that you want to connect with and listen to.

Zooming in and out calls for a material canvas: a situated context from which to work

‘From Outside to Inside’ was another workshop developed as part of the Arts & Interaction minors programme. This workshop uses the situated setting of the garden to evoke a certain embodied knowledge. Participants are invited to experience an overview effect via an imaginary journey to the moon. An immersive session uses YouTube videos from astronauts on the moon and in spaceships, while also raising questions about the actors that we take for granted on the Earth, such as gravity or oxygen to breathe. The YouTube videos show how daily life in the shuttle is made different in the absence of gravity. Simple activities such as combing or washing hair become strange as we watch water droplets float away.

The journey continues when we zoom in. In the second part of the workshop, students are asked to collect objects from the garden and to observe them with a microscope. This invites a sense of amazement at what exists all around us. When magnified 1000 times, solid objects can look loose and invisible nonhuman living

duckweed

beings come into view: bugs on a cigarette filter, larvae in a mushroom, and more. One tutor noted that theory and philosophy classes were an important context for this workshop – an intellectual background which meant that the students could discuss and connect the workshop, actors, and the situated life of the garden, to (real) societal issues. This means zooming in and out through the lens of matter in space but also that of time in context.

‘Yes, it helped us to look back and forth at our theme and concept. By making the concept tangible in the form of a workshop, zooming in and out helped us to question it and to engage with others. The workshop with the microscope was a big inspiration. It made us wonder about the world around us.’

‘Roots of Time’ student project

‘As a tutor, I learned to zoom into the details. And that a tree is living. And that these realities can be used in a creative practice. It made me more aware of living materials.’

— Tutor, Arts & Interaction

Mapping invisible habitats

Mapping is not a new principle in design discourse. It is a general concept, often used in various ways within a design process. It can serve as a research method or it can be an outcome itself. This project approaches mapping as a visualisation or materialisation of various actors – a way of learning about these actors and our intertwined relationships. If mapping is learning, the learning take place through making, through crafting.

Thinking with your hands, learning about the woods, working with wood… the work of designer Christien Meindertsma is exemplary here. Her ‘Bottom Ash Observatory’ project, for example, involved mapping the different elements of the dark residue that is left over following the incineration of municipal waste. Our mapping invisible habitats project principle relates to her thinking. However, using mapping to notice invisible habits requires a more specific approach. Mapping invisible habitats therefore unfolds over four distinct processes. Firstly, the unseen actors and their relationships can be shown rather literally in a map, a form of cartography. Secondly, tools can be used to enhance perception and to map invisible habitats. These tools, integral to that process, also become actors here. Thirdly, mapping the material lives of the actors means translating material into narrative, to reveal and communicate otherwise unseen habitats. Finally, there is mapping of particular correspondences between the actors (Ingold, 2021).

Cartography

Human beings have been making maps since the prehistoric era. The earliest simple charts for understanding and communicating locations and situations have evolved into many forms of cartographic categorisations; grids that make the tangible abstract and the abstract tangible. When students are asked to map a location, it is this kind of mapping that comes to mind. Mapping invisible habitats, though, means more than just making a map of the area. In the garden, for example, it requires more than situating the pond, the trees, and the academy building in the correct ratio and spatial distribution. It is also a cartography of actors and interrelationship from the inside. Other beautiful examples of cartography from within can be found in Terra Forma, a book of speculative maps that focuses ‘on the living and not on a fixed location...living things do much more than move around; they manipulate air and matter in order to create the conditions for their survival, sometimes in cooperation with other living things…this changes the status of the map; it is no longer a fixed image, but rather a provisional state of the world, a working tool in evolution’ (Aït-Touati (Ed.), 2019, p.12).

Grids make the tangible abstract and the abstract tangible

48 | Mapping invisible habitats

the project

takketuin“ The ladder and a persicoop as a tool to get new perspectives up in a tree. Enabeling to see details at higher level. Bottem rigth: a detail of the periscope that emits sunlight from above the trees onto the shirt of one of the students.

Mapping through tools

At first this may seem obvious: tools are necessary. We use our phones as tools, apps such as Google maps to locate ourselves. That’s it – simple, nothing controversial. However, mapping through tools can be examined more profoundly when we follow Latour’s argument that micro-organisms did not exist until Louis Pasteur discovered them with his toolkit (this was in itself a public controversy).

What, then, is a tool, and what is technology in this context? Technology ranges from AI to more basic inventions. ‘I am concerned at a deeper level with how we think with, through and about all our technologies: …their meaning and metaphor, their dialogue and relationships, with the surrounding world. To the ecological thinker, all technologies are ecological’ writes James Bridle in Ways of Being: Beyond Human Intelligence (2022, p.14). Clothing, for instance, is a technology or tool, if not a high-tech one – it was invented many thousands of years ago to keep us warm. Clothing interacts with our bodies and our surroundings: if the sun starts shining we take off our warm jumper; if it rains, we put on a waterproof jacket. The trousers my son is wearing have worn out around his knees because he likes climbing, leaving his traces on his environment and vice versa – changing the garment as a tool. Something

In the context of a mapping project, tools can make the unseen visible, the unheard audible, or make intangible habitats felt

Prototyping of

“Bedrijfsuitje de

similar happens with other tools which are themselves actors, translating their environments and enmeshing more-than-human perspectives. In the context of a mapping project, tools can make the unseen visible, the unheard audible, or make intangible habitats felt. These tools should not be taken for static and merely functional objects. They relate and change because of the other actors they relate to. The ‘Agency to the Actors’ case study focused on technologies which had been approached as part of the minors curriculum over the previous years. Students worked regularly in the TechLab. In the ‘From Outside to Inside’ workshop, students worked with analogue and digital microscopes. The digital microscope, in particular, expanded what they could see of otherwise invisible habitats.

Digital tools are used in the Minor Art and Interaction. Left a high sensitive microphone, documenting the sounds, the juices of a tree.

Sensitive microphones were used in a similar way. One of the students describes a project which involved using these technologies to map the sounds of a tree: ‘For weeks we had been trying to smooth out recordings of the tree that we had captured, in such a way as to draw real emphasis to the juices whose flow is almost a heartbeat of the tree itself. We also captured sounds on a (3FM) radio frequency, because the tree functions as a radio antenna.’

Material as a mapping medium

‘These elements could be seen as communicative instruments coming together to create a ‘”living-artefact” that communicates ideas, beliefs, approaches and compels us to think, feel and act in certain ways.’

Karana, 2020

feather

‘Zooming in with the microscope was nice! To really use it as a tool. To see things you have never seen before, or even was aware of.’

– student project ‘Fuck Nature’

‘The workshop did very much contribute to my thinking. To see things with the microscope was amazing. All the different structure that exist that i would never expect. There is so much more that we cannot see.’

– student project ‘Whelve’

To return to my love of dust: settled dust particles can communicate a diverse narrative. For example, particles of ancient dust, volcanic ash, or soot from prehistoric forest fires, can get trapped in glacial ice for eons. Scientists study these ice cores for the relics of Earth’s historical climates – they are relics that tell a story about how our planet’s climate and atmosphere have changed over thousands of years.

The work of artist and researcher Susan Schuppli, including her collaborations with Forensic Architecture, shows how material could function as a mapping medium. Her research agency at Goldsmiths, University of London, uses research by design to examine material evidence – from war and conflict to environmental disasters or climate change – taking this evidence as material testimony which can be used to reconstruct and analyse violent human rights histories and events. Here, research by design shows how material mapping not only involves transforming or working with matter, but also observing how the material condition can document or reveal a story.

Our own case study found that design students were the only students who had a visual vocabulary for using materials as mapping media. Mapping requires an established skillset of knowledge for working with (living) material conditions, and for using materials as a mapping medium to attune to nonhuman habitats. In the absence of this skillset, what happened was that the students created treated their materials as subjects, rather than using the material conditions of the garden as a perspective or framework. One student said: ‘Yes, we literally looked at all the things that grew

Research by design shows how material mapping not only involves transforming or working with matter, but also observing how the material condition can document or reveal a story

in the garden. We collected them and wrote about it. We observed the pond in detail.’

Correspondence

Mapping invisible habitats should never be a (human) sovereign action. This is crucial: the map that dominates its subject is inherently problematic. The assumption of domination, however, is often unintentional. For example, simplification can result in stereotyping. Just as actors influence one another, so too mapping should be done through the ‘correspondence’ proposed by Tim Ingold in his book Correspondences (2021). Haraway’s ‘response-ability’ (Staying with the Trouble [2016]) is an alternative framework. Mapping in correspondence and response-ability are principles based on the study of literature and philosophy, rather than experiential case study work. As higher education moves towards increasingly formalised learning, this is no surprise. In this context, Ingold’s invitation to open a correspondence as a dialogue of care with the actors around us – a way of noticing them, understanding them, and loving them – is not easily integrated with the curricula of design education. It means, as he describes it, embracing vulnerability, and taking up our work on premises of trust and intuition, of not knowing our outcomes. This proclamation of love is urgent, as he writes, drawing on Hannah Arendt: ‘Only if we fall back in love with the world can there be new hope of renewal or genera-

The map that dominates its subject is inherently problematic

tiger’s

tions to come. And to do that we need to relearn the art of thinking, and of writing, from the heart as much as from the head’. Our subsequent research steps expand on and deepen this process in the context of the project.

We performed Latour’s ‘Parliament of Things’ workshop as part of our attempt to draw the principle of mapping into correspondence with the Arts & Interaction minors programme. Each participant was assigned a chosen actor to ‘voice’ in the speculative parliament. This workshop sensitised the students to the concept of actors, however, it did not result in any expansion of their projects towards correspondence mapping. Reflecting afterwards on this workshop made me realize that participants were speaking on ‘behalf of’ an actor rather than in correspondence with it.

Conclusion

The principle of mapping is considered in detail here, however, the outcomes of our student projects and their post-project feedback interviews revealed that mapping invisible habitats never rose above a superficial level.

One of the tutors states: ‘Mapping is not in the wider curriculum at St. Joost. This means we lack a deeper understanding of the theory and process and we need to develop our vocabulary, find further examples, and so on. Only the New Design and Attitudes students had a basic understanding of mapping’. Further research is needed to achieve a better understanding of how mapping invisible habitats can be integrated into (design) education.

56 | Mapping invisible habitats

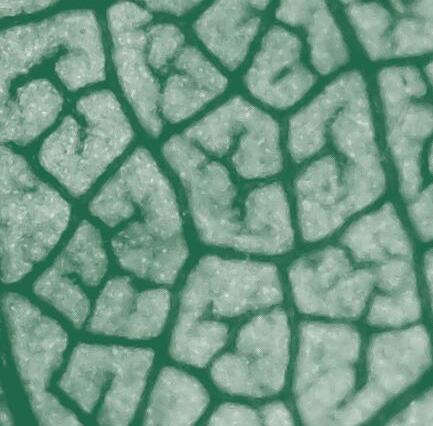

glaze

A paradigm shift is needed in the curriculum of design education; from human-centred design to more-than-human design, collaborative and situated

Conclusion

As we have seen, more-than-human modes of understanding need to be implemented into the curriculum of design education. This means a paradigm shift –from human-centred design to more-than-human design – that is collaborative and situated. The process of sensitising future designers takes time, and needs to start at BA level. This project’s principles – augmented senses for noticing nonhumans, interaction as flux between the actors, zooming in and out on nonhumans, and mapping invisible habitats – overlap, intertwine. Further case studies are required if we seek to better understand how these principles can be implemented through the curricula of institutional design education. This is a matter of learning while doing: not engraving principles in stone, but rather, porous experimentation. To reimagine this, drawing on metaphors used by Haraway in Staying with the Trouble, let’s put this guide into the pile of ‘compost’, to fertilise the hot pile of ‘oddkin’ so that it can transform into nutrient-rich soil. Hopefully, we place this rich earth in the garden of St. Joost, in the long grass and meadows full of life. The garden that Sees, Smells and Hears.

Caradt deploys art, design and technology to explore possibilities for a sustainable future

About Annemarie Piscaer

Annemarie Piscaer is a designer, researcher and educator. She is fascinated by dust, small particles floating in the air, an ever-changing cloud. A scattered seeming mess in a constant flux, with its own logic throughout time. We are made of long-existing elemental particles.

She is currently a researcher at the expertise centre Caradt, working in the Biobased Art and Design research group on the project ‘The Garden as a Living Learning Lab, a Living Sensor. The Garden that Sees, Smells, and Hears’. She tutors on the New Design and Attitudes study programme at St. Joost School of Art & Design, teaching courses including sensing and maker-ship*.

She completed a BA degree at the Design Academy Eindhoven, and an Education in Arts Masters at the Piet Zwart Institute Rotterdam, with the dissertation project ‘As a designer I’m an expert I’m an amateur’. She lectures regularly on her design practice and learning environments at various (art) institutions, and has been external advisor to the Creative Industries Fund NL, among others.

Annemarie founded Studio Dust, a participatory research-by-design studio with the principle that everything has value, even dust: from dust to dust. The studio focusses on material development. She is also co-founder, with Iris de Kievith, of Lab AIR, a design collective addressing aerial issues. Smogware – ceramic tableware coloured with air pollution – was their first project.

Annemarie Piscaer is a designer, researcher and educator fascinated by dust

Annemarie

* Students on this course were taught to develop an awareness of their senses and asked to use this in a project, thus creating embodied knowledge with the body as a material and a context for the work.

About New Design and Attitudes

New Design and Attitudes has two pillars: Situational Networks and Material Ecologies. Situational Networks concerns designing for networks: assemblages that connect people, things, places and situations. It works from a context-specific design question, using authentic and proven research methods to map the values of a specific network or collective. Material Ecologies students unravel and map the material narrative of a design: its systems and human and nonhuman actors. The concept of material is used broadly here – from traditional materials such as wood or clay, to living materials including micro-organisms, to virtual materials, bits and bytes. Material Ecologies emphasises ‘thinking with your hands’, developing craftsmanship (both physical and digital), and mapping through design research.

Material Ecologies emphasises ‘thinking with your hands’, developing craftsmanship (both physical and digital), and mapping through design research

Afterword

Here you find video clips of the performed workshops. The workshop From Outside to Inside was developed during the case study. The workshop From Grassroots to Blueprint took place afterwards. These footages give insights on what happened, but moreover serve as an interactive sensorial touch additional to the written part: sense making.

The immersive workshop From outside to Inside as described in the chapter ‘zooming in and out on nonhumans’ uses the situated context of the garden. It attempts to evoke a certain embodied knowledge. In an imaginary journey to the moon, participants are firstly invited to experience an overview effect. And continues by zooming in. Students were asked to collect things from the garden and observe it under the microscope. Depicting an amazement of what exists all around us, solid things look loose zoomed in 1000 times, nonhuman living things appear, bugs on a cigarette filter, larva in a mushroom etc.. A moment of care.

From Grassroots to Blueprint took place during a workshop week with second year New Design and Attitude students. Unravelling, mapping and questioning, what can be made with what grows and blooms in our own environment? Can design be regenerative, be beneficial to nature instead of harming it? We used a simple process to make green paper from grass and nettles. It is mainly perennial ryegrass that grows in the Academy’s garden, a type of grass that can be seen as an invasive species. If this grass is too excess, other

| About the project

species/herbs will have less space. By removing the clippings of this perennial ryegrass, the soil becomes poorer, which benefits other herbs. In short, using grass clippings as material for a design ensures a more biodiverse garden.

In this process, students had to observe, have a detailed look. We found tiny mushrooms, stunning shapes in leaves, traces of animals. We collected these, played with them -layering, composition. And used it to make cyanotypes. Printing things through sunlight. Understanding light also as a source, an actor. Botanic Anna Atkins, one of the first to apply it as a form of photography, used it to map and document knowledge of various plants. You could see the results as a blueprint of a place, revealing the narrative of the garden.

Note: In case the QR codes do not function, have a look at studiodust.nl.

Bibliography

Abdulla, D., ed. (2018). Design as learning; a school of schools reader. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Abdulla, D., ed. (2019). Modes of crisis; radical pedagogy. Eindhoven: Onomatopee.

Aït-Touati, F.; Arenes, A.; Gregoire, A. (2019). Terra Forma. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Bieling, T., ed. (2019). Design (&) activism ; perspectives on design as activism and activism as design. Mimesis International.

Black Mountain College Foundation. Black Mountain College [online] https:// www.blackmountaincollege.org/history/ [accessed September 2018].

Boeke, K. (2021). Wij in het heelal, een heelal in ons. Zutphen: Walburg Pers B.V., Uitgeverij.

Boelen, J.; Sacchetti, V. (2019). Design as a Tool for Transition: The Atelier LUMA Approach. Self-published.

Boelen, J.; Kaethler, M. (2020). Social Matter, social design. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Böhm, K.; James, T.; Petrescu, D. (2017). Learn to act, Introducing the eco nomadic School. Paris: aaa/peprav.

Bridle, J. (2022). Ways of Being: Beyond human intelligence. UK: Penguin Random House.

Cluitmans, L., ed. (2022). On the necessity of gardening. Amsterdam: Valiz. Cosmological Gardens [online] http://www.centerartsdesign.org/ projects/COSMOLOGICAL%20GARDENS [accessed June 2022].

Cultural Geographies Vol. 16, No. 2, Special Issue: Indigenous cartographies (April 2009), pp. 207-227 (21 pages).

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. Indianapolis: Kappa Delta Pi. Dietachmair, P.; Gielen, P.; Nicolau, G. (eds.) (2023). Sensing Earth: Cultural Quests Across a Heated Globe. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Dittel, K.; Edwards, C. (2022). The Material Kinship Reader. Eindhoven: Onomatopee.

D’Olivo, P; Karana, E. (2021). Materials Framing: A Case Study of Biodesign Companies Web Communications. The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation Vol. 7, No. 3.

Forensic Architecture. Forensic Architecture [online] https://forensicarchitecture.org/ [accessed March 2023].

Forlano, L. (2017). Posthumanism and Design. Tongji: Tongji University Press. Guattari, F. (1989). The Three Ecologies. new formations, No. 8, pp. 131- 147. Hamers, D.; Bueno de Mesquita, N. ; Vaneycken, A.; Schoffelen, J. ( 2017). Trading places; practices of public participation in art and design research. Barcelona: dpr-barcelona.

Haraway, D., (2016). Staying with the Trouble. London: Duke University Press. Haraway, D. Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 575-599.

Hildyard, D., (2017). The Second Body. London: Fitzcarraldo Editions. Ingold, T. (2013). Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge.

Ingold, T.; Palsson, G., ed. (2013). Biosocial Becomings: Integrating Social and Biological Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ingold, T. (2021). Correspondences. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Jaque, J.; Verzier, M.; Pietroiusti, L. (2020). More-then-human. Rotterdam: Het Nieuwe Instituut.

Kahn, R. (2010). Critical pedagogy, ecological literacy, and planetary crisis. New York: Peter Lang.

Karana, E. (2020). Still Alive: Livingness as a Material Quality in Design. Breda: Avans University of Applied Sciences.

Kasteel IJpelaar [online] https://docplayer.nl/166146739-Kasteel-ijpelaarte-breda-gemeente-breda.html [accessed June 2022].

Koskentola, K.; van der Loo, M. (2023). Enfleshed: Ecologies of Entities and Beings. Eindhoven: Onomatopee.

Kotov, K., (2022). LT Ranch Summer Session. self-published.

Latour, B. (2018). Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-networktheory. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Latour, B. (1991). We have never been modern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B. Inside a performative lecture [online] http://www.bruno-latour.fr/ node/755.html [accessed January 2019].

Learning with the garden, learning from the land [online] https://www.wdka.nl/ news-events/learning-with-the-garden-learning-from-the-land [accessed June 2022].

Nahum, R. Kosmica Institute [online] https://www.kosmicainstitute.com/ about-us/team/ [accessed June 2022].

Navarro, E., ed. (2021). This book is a plant. London: Wellcome collection. New Materialism [online] https://newmaterialism.eu/almanac/s/ situated-knowledges.html [accessed June 2022].

Nicolescu, B. (2013). Methodology of Transdisciplinarity. Paris: CIRET.

Nigten, A.; Piscaer, A. (2018). Fluid environments for transdisciplinary learning. Proceedings Balance-Unbalance 2018 conference, Rotterdam.

Nigten, A.; Piscaer, A. (2019). Colliding systems: formal and real-life learning. GwanJu, Republic of Korea: Lux Aeterna.

Piscaer, A. [online] https://studiodust.nl/?page_id=257 [accessed June 2022].

Ranciere, J. (1991). The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Schuppli, S. [online] https://susanschuppli.com/ [accessed June 2022].

Strauss, C. (2021). Slow spatial reader; chronicles of radical affection. Amsterdam: Valiz.

Staal, G., ed. (2021). New material award 2009-2018. Rotterdam: Het Nieuwe Instituut.

The Garden Department [online] https://www.extraintra.nl/initiatives/ nomadic-garden/ [accessed March 2023].

Thwaites, T. (2016). Goatman: How I Took a Holiday from Being Human. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Urgent Pedagogies [online] https://urgentpedagogies.iaspis.se/buildingspaces-for-learning-together-in-freedom/ [accessed June 2022].

Wakkary, R., (2021). Things We Could Design For More Than Human Centered Worlds. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Research Departement

Biobased Art and Design (BAD), Caradt

Biobased Art and Design Caradt Professor

Elvin Karana

Content Editing

Daisy Hildyard

Publication Design SIVK — sivk.nl

Printing and binding

De Kijm | Bijzonder drukwerk

Contact

Caradt (Centre of Applied Research for Art, Design and Technology)

Avans University of Applied Sciences

Post Office Box 90116

4800 RA Breda (NL)

caradt@avans.nl | +31 (0)88 525 73 70 | caradt.nl

Thank you all, human and nonhuman.

Case study minor tutor team:

Jeroen van de Korput

Sarah Lugthart

Michiel van Opstal

Michel Gutlich

Annelies Herfst

All students:

Miles, Nynke, Sebastian, Davey, Elisa, Sammie, Sander, Jomane, Jet, Eli, Dauphine, Manon, Lisa, Larissa, Luuk, Noor, Laura, Eva, Chris, Emiel, Lisanne, Lieke, Friederike, Celina, Noami

Caradt Biobased Art and Design group: Elvin Karana

Caradt: Wouter Meys

And Ilse van Klei, Bas Rellum, Daisy Hildyard

Annemarie Piscaer 2024 Rotterdam

astronomic nebula

the garden as a living learning lab