ISBN: 978-1-3999-7937-5

My Wonky Brain

ISBN: 978-1-3999-7937-5

One day, a man called Willy decided to write a story. That might not sound like a particularly unusual thing to do. But this story would be different because instead of writing it himself, Willy decided his story should be told by lots of people. Over 10 people in fact, whose ages ranged from 12-years-old right up to 60!

And it would include pictures – lots and lots of pictures.

Why do this you might ask? Well, that’s a good question. The first reason is because Willy loves drawing and has even won prizes for his art. So having pictures went without saying.

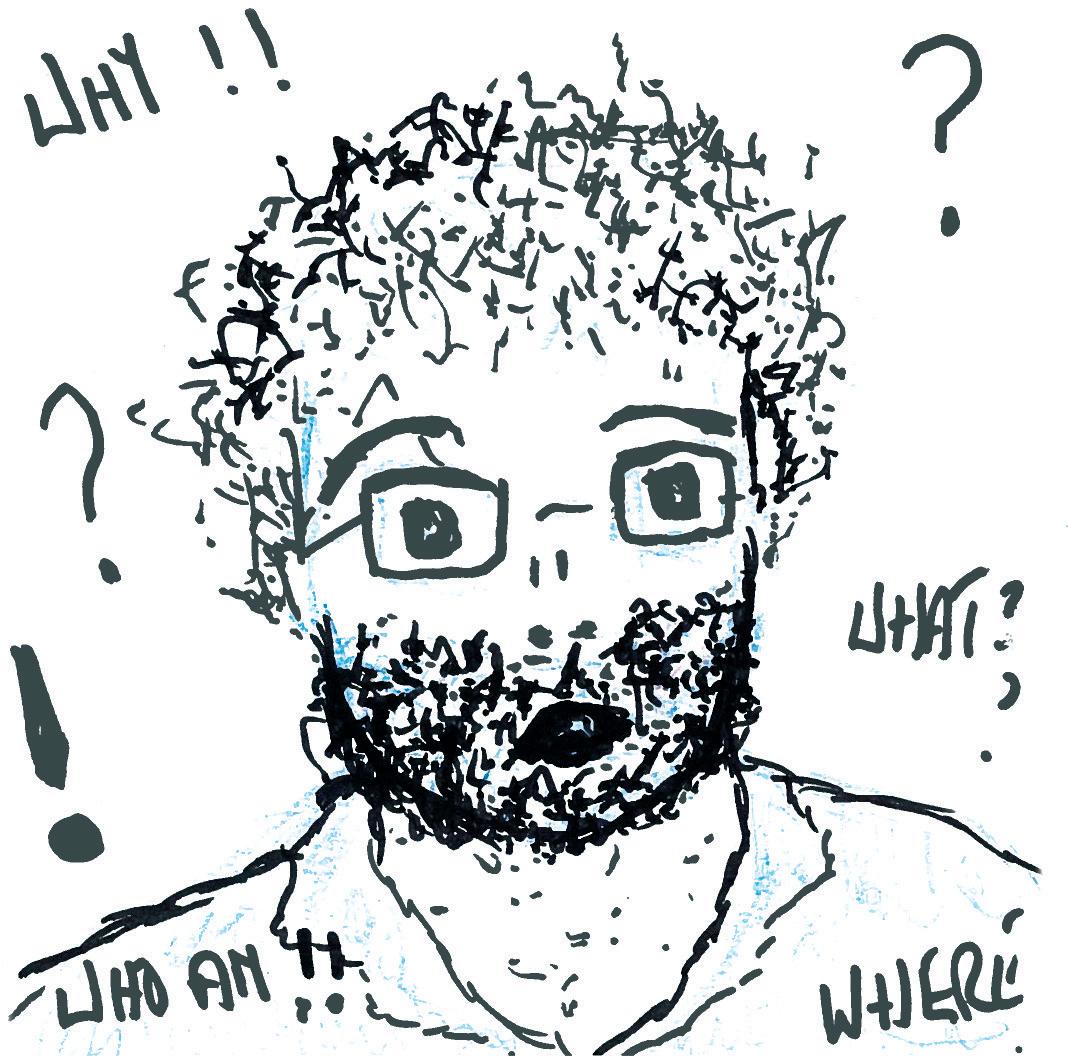

The second reason is that Willy has what he sometimes calls “Wonky Brain Disease.” The proper name for his Wonky Brain Disease is Alzheimer’s Disease which is a form of dementia. In Willy’s case, his Alzheimer’s Disease affects his vision and sometimes his memory. Some people think that people with Alzheimer’s Disease don’t have much to give anymore, because they forget things and often need help with tasks. But Willy disagrees. He thinks people with Alzheimer’s Disease can often do just as much, because each person’s experience of Alzheimer’s is very different. Equally, he knows that there’s a lot of clever technology and kind people about who can assist in helping people living with Alzheimer’s achieve great things!

Thinking that a disease is shameful because of how it makes someone behave is a type of stigma. And Willy hates stigmas. But he’s aware that lots of people think in stigmatising ways about dementia, whether they mean to or not…

So Willy thought it’d be great to get some people to help him make his story into a book. That way they could learn all about his cool life working for the BBC and being an award-winning artist. They might even learn a bit about “Wonky Brain Disease”

along the way, and help others reading the story to think differently about it too!

The names of Willy’s story assistants were Ailsa Tully, Valeria Lembo, Gerry King, Gracie Irvine, Dawn Irvine, Sheila Godman, Robbie and Murray Dickson, Adam Robertson, Maria Stoian, Gabriel Hutchison, Lucie Jeffrey and Alex Howard.

And this is what they had to say…

There once was a little boy called Willy who lived in a place in called Woodbridge, Suffolk. There aren’t many things for wee boys to do in Woodbridge, Suffolk – no cinemas, bowling alleys or playparks, or things like that. For some children, this would be a problem.

But not for Willy because he had an active imagination and loved adventuring outdoors. And this was lucky because Suffolk has a LOT of outdoors, with forests and rivers and a huge, long beach. Willy even had a zip-wire in his own back garden!

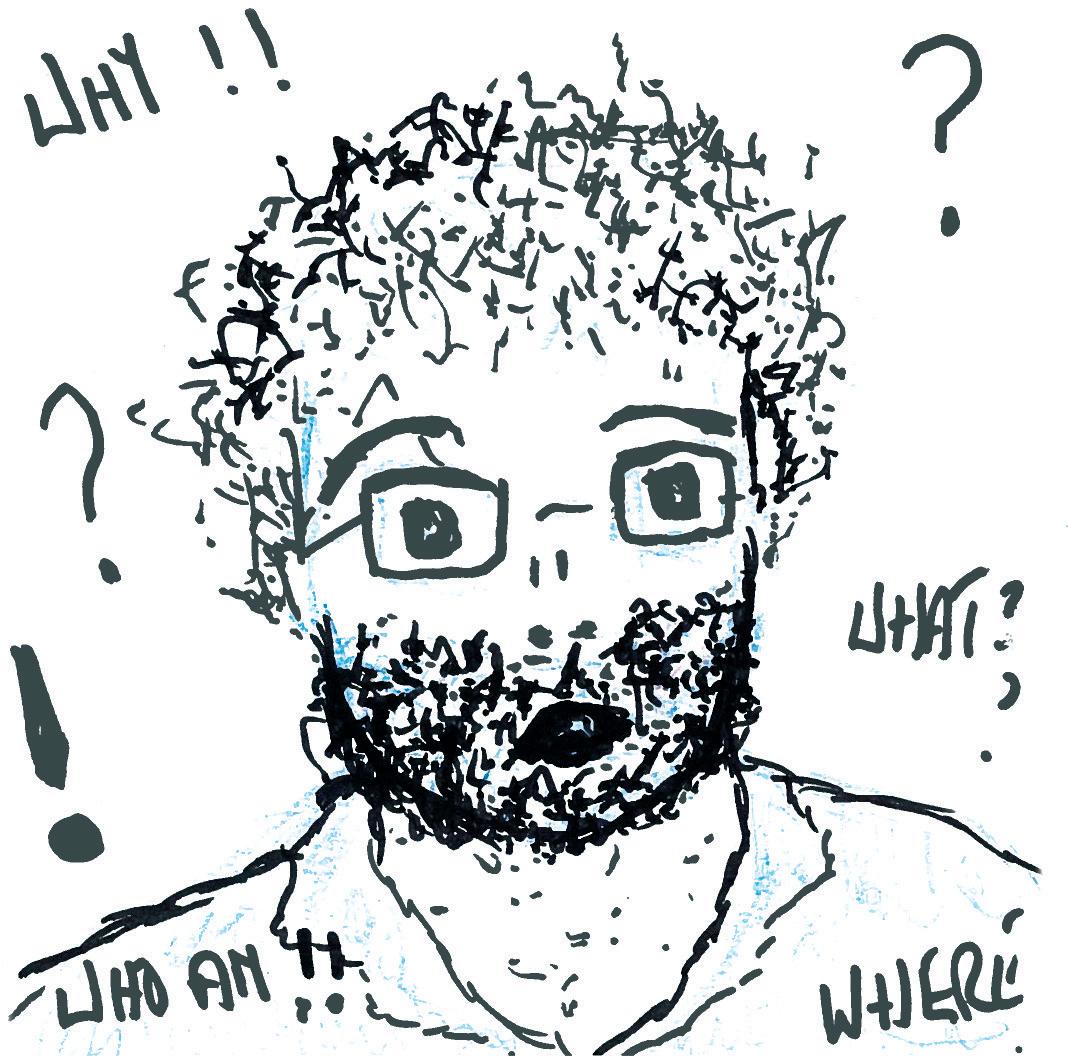

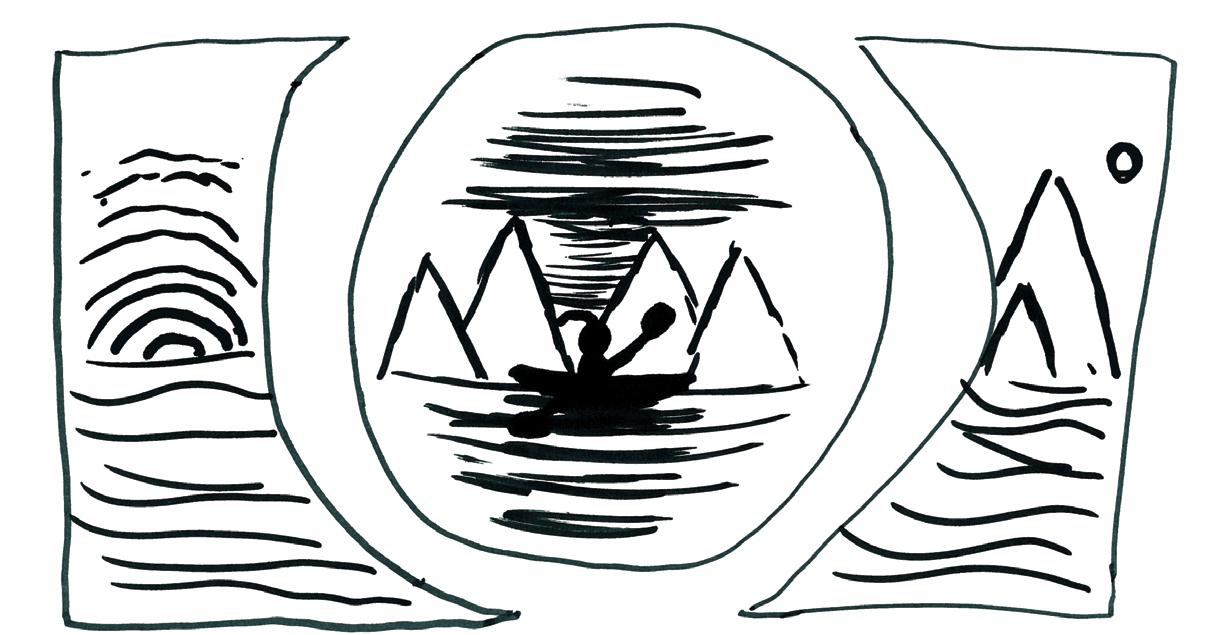

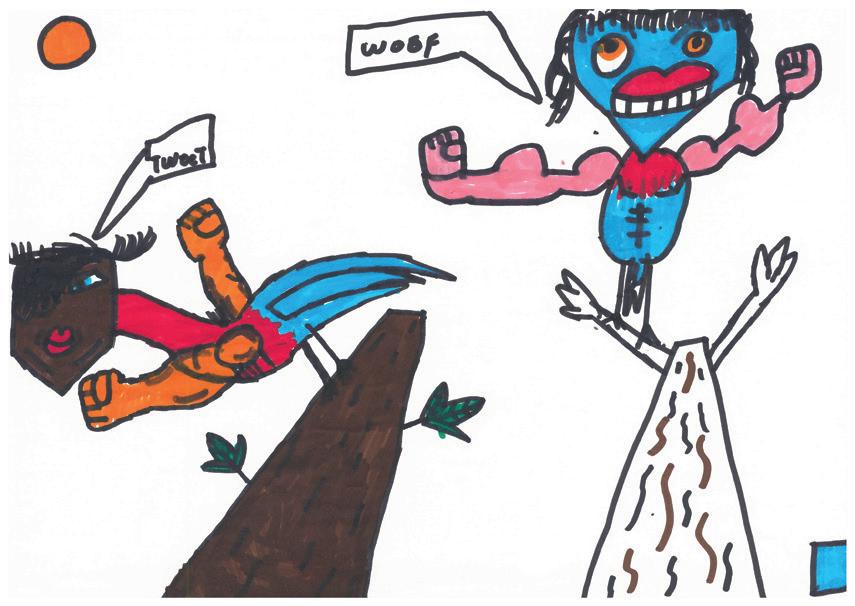

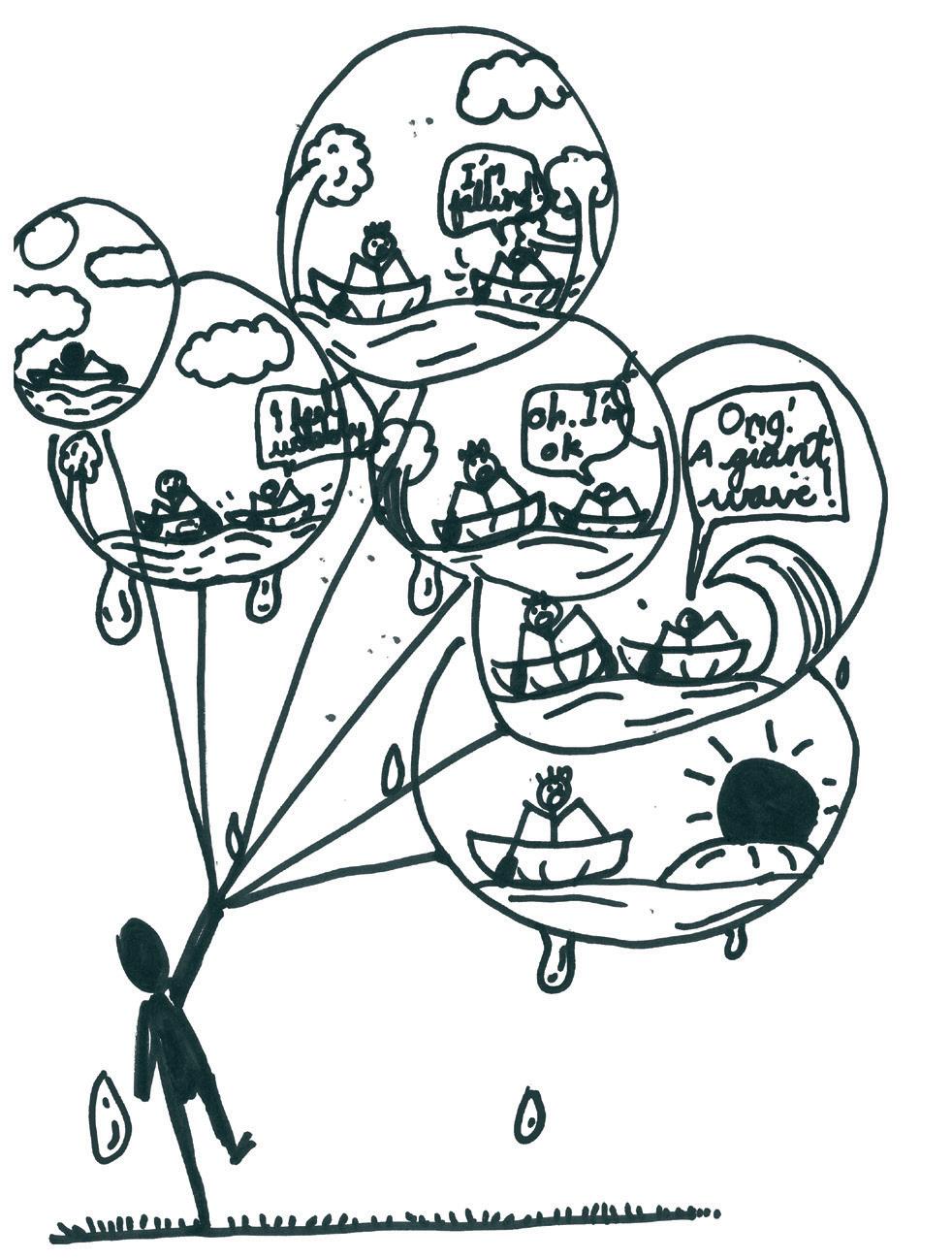

One of Willy’s favourite things to do as a little boy was go kayaking down the river by his house…

A kayak is a type of small boat that you row. Why did he like kayaking, you might ask? Well, there were many reasons… He loved looking at his kayak cutting through the glittering water…

He loved watching his paddle splash through the river’s currents as he rowed around sharp bends…

And of course he loved racing the ducks who always bobbed alongside his kayak like they owned the whole river!

Willy never felt lonely, even though he was out on the river all by himself. Why? Because he was very good at thinking up new challenges for himself… like testing out how much he could rock his kayak without capsizing it…

Or how long he could hold a leapfrog pose in the middle of the kayak without falling in.

(It wasn’t very long – about 3 seconds max!)

At other times, when the sun went behind a cloud, Willy switched on his imagination. Instead of going down a river in England, he liked to pretend he was riding the waves around a desert island with lots of palm trees, keeping an eye out for pirates.

Or dodging hungry sharks in tropical waters…

When it was cold and drizzly (and it was cold and drizzly a lot) he imagined he was kayaking between snow-capped mountains in Norway, dressed in a cosy jumper, heading back to a log cabin where he’d have hot chocolate and marshmallows waiting for him…

Other boys might have found blustery days out alone on the river a bit frightening. But not Willy – he could simply not say no to a new adventure out on the water.

Sometimes, when the weather was REALLY bad, Willy’s mum stopped him going out on the kayak because she worried he’d be washed out to sea. On these days, Willy switched on his imagination again. He played with his trains, imagining he was a signalman for a busy commuter line, or drew pictures of fierce dragons and fantastical creatures from far off mythical lands…

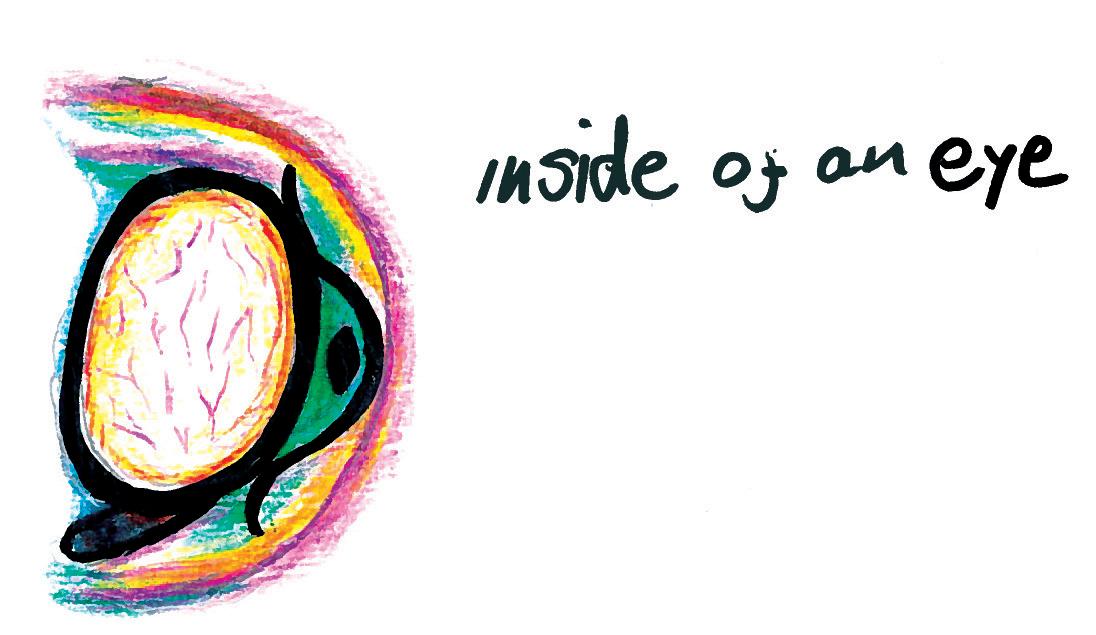

One thing was for sure: Willy LOVED a good story. He was late to start reading, but once he got going, there was no stopping him. And when the other boys were off playing football in the evenings, he would work his way through his library book pile. He particularly liked scaring himself with ghost stories, so his eyes went into big wide orbs like this…

I think you get the sort of boy Willy was. He was the type of boy who liked to go on adventures in real life and in his mind. Like most little boys, he probably had no idea what Alzheimer’s Disease was, or what it did to the brain… or how indeed it made it “wonky”. That was to come much later.

But before that, let’s pay a visit to Willy when he was just a little bit older, after he had left school and found himself a job.

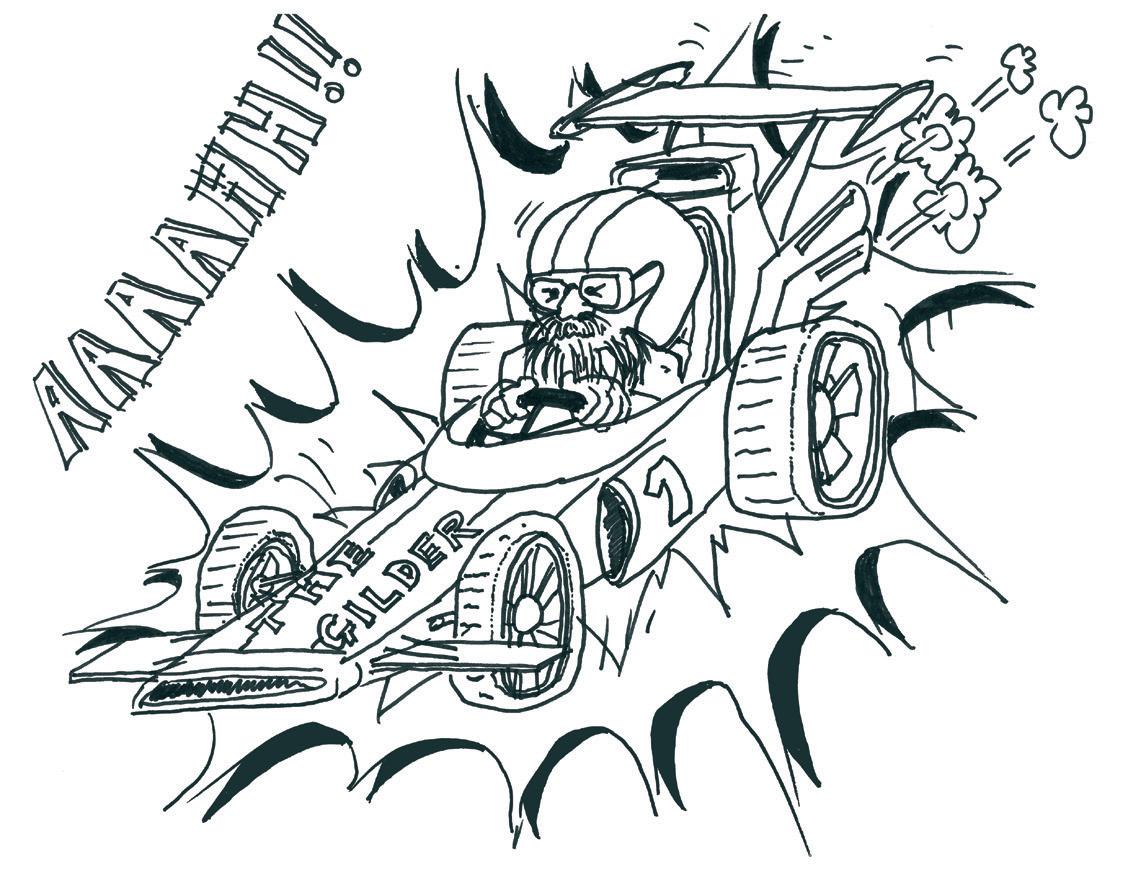

30 years rushed past, and suddenly Willy was all grown up. How did we know he was grown up? Well, for one thing, he had grown a beard and little boys tend not to have beards, unless they’re appearing as Joseph the Carpenter in school plays. He had also got married and lived with his wife and two children in a place called Northampton, and these are very grown-up things, too.

He had also got himself a job… a really cool job. He was now a broadcast journalist for the BBC. A broadcast journalist is someone who finds interesting stories that can be shared on the radio and TV. So in a way, he was still surrounded by good stories, only this time he got them from real people, rather than from books (although he did still love a good book.)

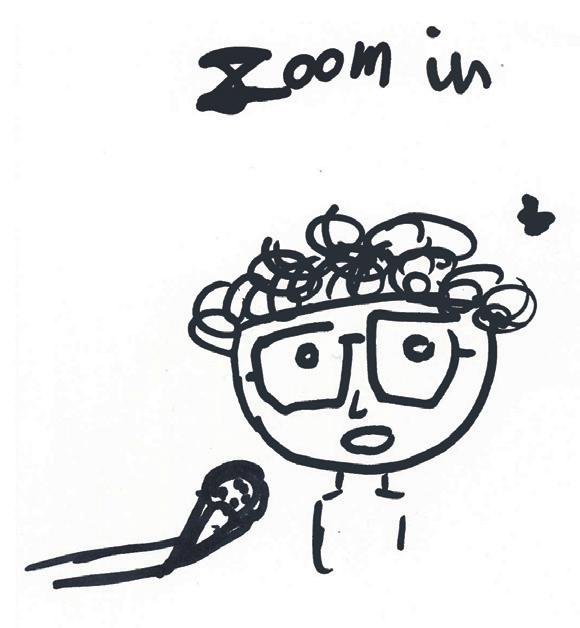

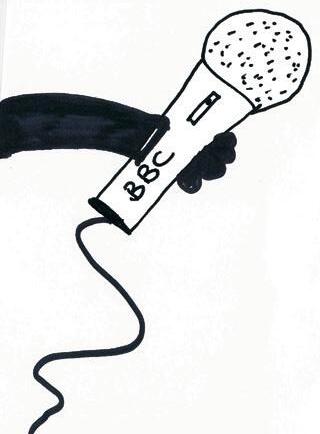

Here’s Willy telling his radio listeners all about some nasty floods that had happened in Northampton city centre...

One morning, Willy and his broadcast journalist friends were alone in the BBC radio studio. The phones were quiet as there weren’t many exciting things happening in Northampton that day. Suddenly, Willy’s producer turned to him and said: “I bet you couldn’t find a real gangster on the streets of Northampton. Someone who’s armed with a weapon, for instance. They’d NEVER want their voice shared on radio!”

But Willy’s producer had forgotten something important about Willy. Just like when he was a wee boy, Willy could not say no to a new challenge… no matter how scary it seemed!

“Ha!” said Willy to his producer. “Challenge ACCEPTED! I bet I can get an interview with a gangster.”

“Bet you £10 you can’t,” insisted Willy’s producer.

“Bet you £20 I can AND be back in 10 minutes! Hold my coffee…”

So with that, Willy left the BBC radio studio and headed out to look for some gangsters in Northampton. His colleagues watched him through the window beside the mixing deck.

Finding a gangster is difficult, because a gangster doesn’t necessarily want everyone to KNOW they’re a gangster all of the time.

So Willy switched on his imagination. He put himself in the shoes of a gangster, just like he used to put himself in the shoes of an adventurer when out in his kayak.

“Hmm, where would I go if I was a gangster?” he thought.

Then, Willy had a brainwave. “I know what I’d do if I were a gangster! I’d find the type of shop where people can sell things quickly for cash! Yes! There are bound to be gangsters hanging around those types of shops.”

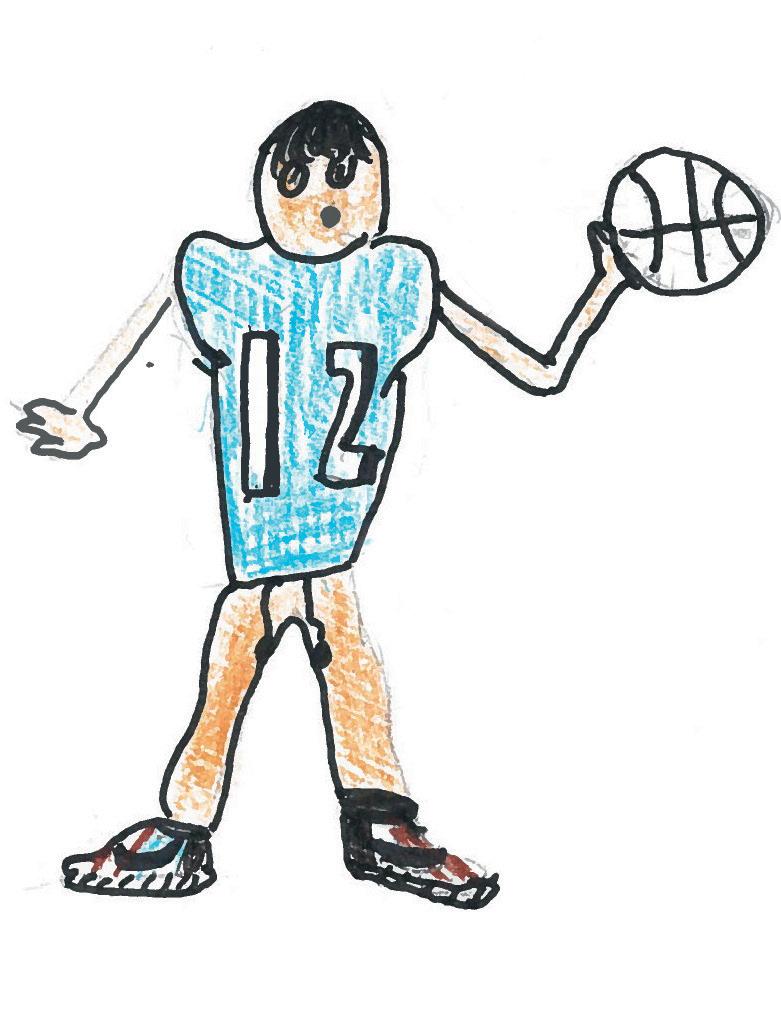

So he headed down the street, his microphone hidden in his pocket, and his eye on his watch. He needed to find gangsters soon or he’d lose the bet. Suddenly, he spied a group of young boys looking like they were up to no good outside a cash-sales shop. One was huge with broad shoulders – he reminded Willy of an American basketball player.

“Ah ha!” thought Willy. “I think we have found ourselves some gangsters!”

Willy took a deep breath. He was excited and nervous. Excited because if they were gangsters, he had won his £20 bet with his producer; nervous because if they were gangsters… well… they were GANGSTERS!

Carefully, he reached into his pocket and pulled out his microphone. He sidled up to them slowly. He didn’t want to cause alarm.

“Um, excuse me, gentlemen…” said Willy tentatively.

One of the boys turned to face Willy and gave him a piercing stare.

Willy gulped. “Um, I would like to ask you a question, please. But don’t tell me your names. It’s going to be on the radio, and I don’t want you to get in trouble with the police.”

Willy held the microphone nervously in front of the boys. “Tell me, if you would… are you carrying any weapons?”

“Yeah, mate,” said one of the boys. “We have weapons. We know it’s wrong, but we have to… because other people carry weapons so we have to protect ourselves.”

They told Willy their story, and it was a very sad one. But they were grateful that they had got to share it. Willy had won the bet! But more than that, he had made a special and unexpected connection with two people who were just happy to share their story with someone who cared.

Willy often thought about this moment, even many decades later when his beard was much bushier. Imagination and challenges had always got him out of sticky situations, and one day they would have their own part to play in helping him through his new life living with Alzheimer’s Disease…

The gangsters had taught Willy a valuable lesson. How people were on the outside didn’t always match up with how they were on the inside. And just because society discounts someone because of who they were, didn’t mean that they didn’t have talents and skills to offer. Willy would often think about this in later life, too, particularly when fighting to remove the stigma around people living with dementia and what they can offer the world.

Willy continued to work at BBC Radio Northampton for many years. He loved finding out about other people’s lives and he quickly learned that everybody has a story to tell, and many even have hidden talents! He could use his imagination to think up interesting story angles and his adventurous spirit to go to places others were too scared to go, or ask the questions others were too scared to ask.

His only regret was that he didn’t start working in radio sooner, immediately after he finished school!

One day, when Willy was 67-years-old, he received some sad news. Someone called him on the phone to tell him had been made redundant. Being made redundant means a company can no longer give you a job because of funding cuts or other big changes in how the company runs. In Willy’s case, the BBC was making cuts to local radio stations, and one of these was BBC Radio Northampton.

Not being able to work at the BBC any more made Willy very gloomy. He adored his job and could have happily done it forever. Then, several things happened at once in his life and he developed an illness called depression.

Depression is an illness which makes you feel sad and hopeless all the time. Even the things that never failed to cheer you up before, like a puppy jumping up to say hello to you, don’t cheer you up when you have depression. Willy completely stopped drawing and reading, because these things no longer made him cheerful. It got so bad he even had to spend some time in hospital.

While in hospital, Willy was convinced something was up with his brain that the doctors didn’t know about. Something physical. He told the doctors this, but they insisted it was just depression, because he kept passing all the tests used to diagnose other brain diseases. After he left hospital, he moved up to Scotland to be closer to family. It was up here that Willy finally got a very special brain test that would change his life forever…

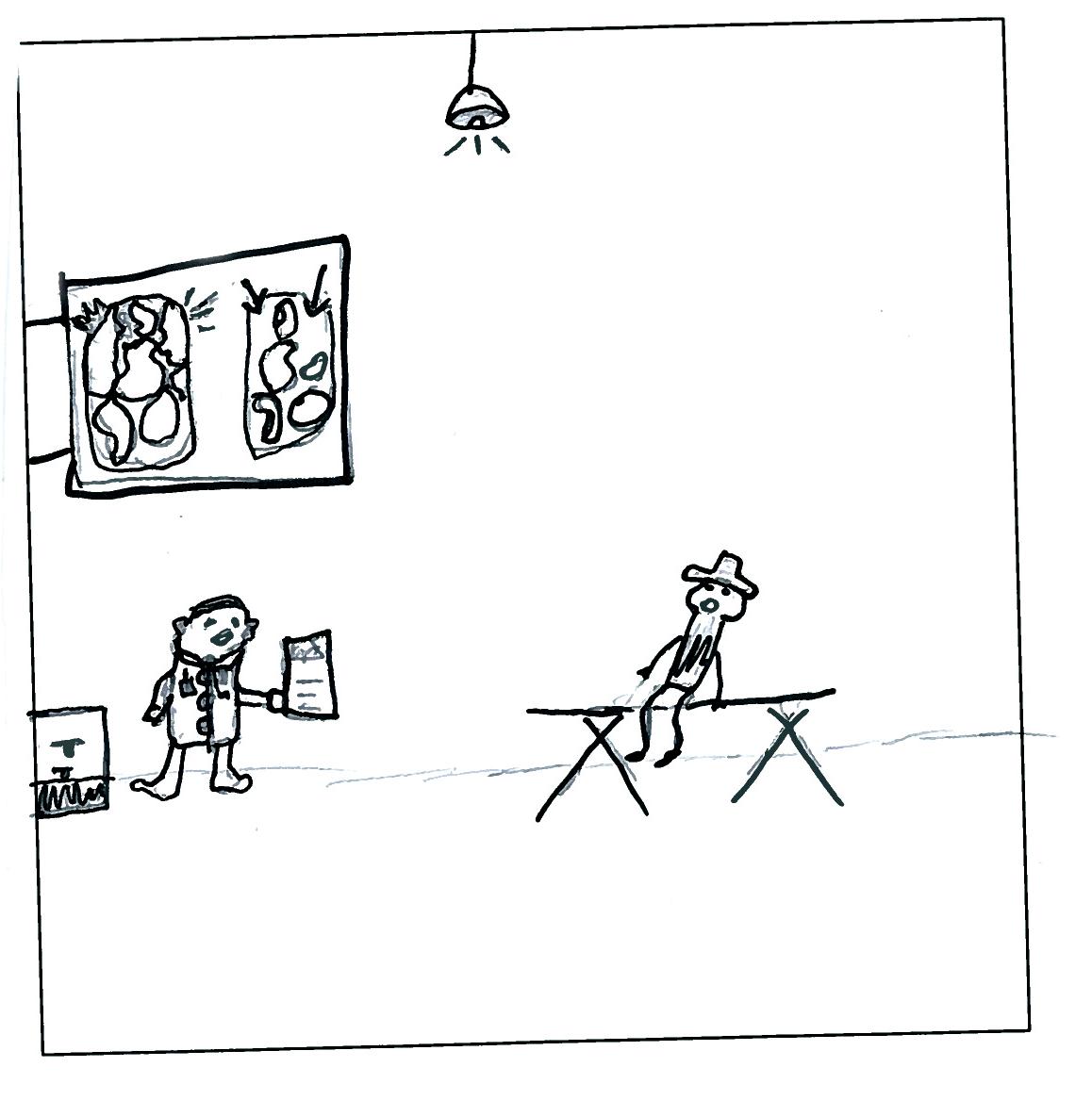

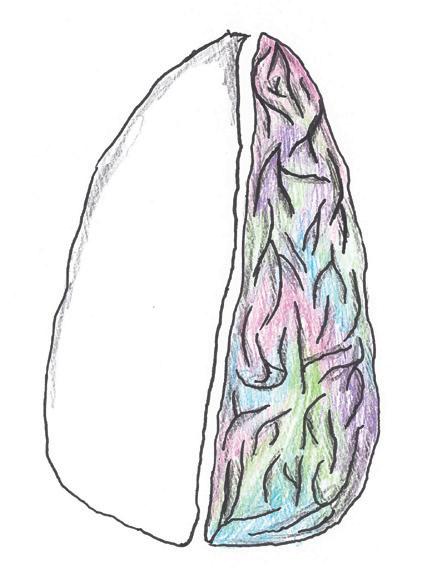

One day, a doctor in Edinburgh offered Willy a scan called a SPECT scan with a very high-tech machine. This machine was so clever that it was able to show what was going on inside Willy’s brain on a screen.

The doctor then pressed a button which made different parts of Willy’s brain light up in various colours. It all looked very pretty!

Suddenly, the doctor turned serious. When a doctor turns serious their face can look big and scary.

The doctor said the scan of Willy’s brain showed that some parts weren’t lighting up in quite the way they should be. This meant they weren’t working as busily as they should; they had shrunk down like a tightly squeezed bit of paper. This was caused by pesky proteins that shouldn’t be there. The doctor said that these pesky proteins were called amyloid plaques and tau, and that they were warring with Willy’s nerve cells like alien mutant warriors!

The pesky protein warriors were attacking a part of Willy’s brain called the parietal lobes, which help you see and judge space. This explained something else strange that Willy was experiencing – a black dot floating across his eyeline.

Unusually, the pesky plaques were leaving Willy’s hippocampus alone – the part of the brain that makes new memories. This was strange because the pesky plaques usually liked attacking this bit of the brain first in Alzheimer’s Disease.

But Willy’s memory was pretty good – he could remember things that happened a long time ago, like kayaking as a little boy, as well as most things that happened very recently.

But the pesky plaques were definitely there – the doctor’s screen showed them. And since Alzheimer’s Disease is a progressive disease, their attack on his brain cells was likely to increase over time…

The thought of his brain going wonky gave Willy lots of emotions. He felt scared, angry, frustrated, and alarmed. Back then, he thought Alzheimer’s Disease would mean the end of his life as he knew it. This, of course, didn’t help his depression.

After he left the doctor with his new diagnosis, Willy got in his car and whizzed back home around the Edinburgh Bypass, imagining an alternative life as a Formula One racing driver.

This made him forget about things for a minute.

And then he realised something – he still had his imagination!

Over the next few months, Willy made a big effort to meet new friends and take part in new creative activities. This took some courage, as having both Alzheimer’s Disease and depression made Willy really not want to do either of these things sometimes. He met people online, through websites like Twitter, who also lived with dementia. Some of these people were dementia activists. An activist is someone who believes so strongly in something that they are happy to shout about it very loudly in the hope others will change their opinions.

Meeting these new inspirational people living with dementia gave Willy hope that he might still lead a good life with the disease. He got an Alexa smart speaker which was great at helping him listen to music without having to use phones and computers which could play havoc with his wonky-brained vision.

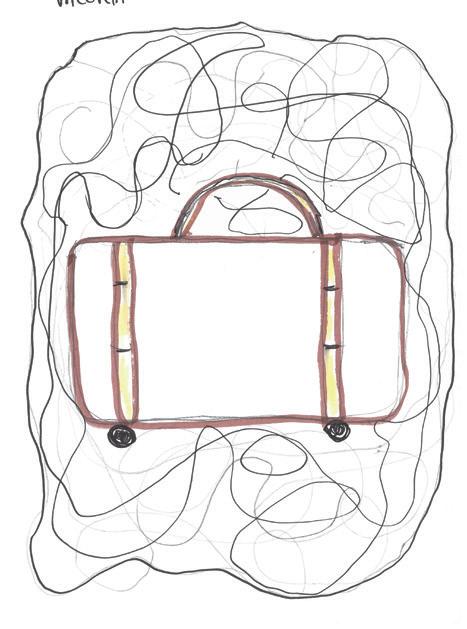

However, he did have moments when he struggled, particularly where suitcases were involved…

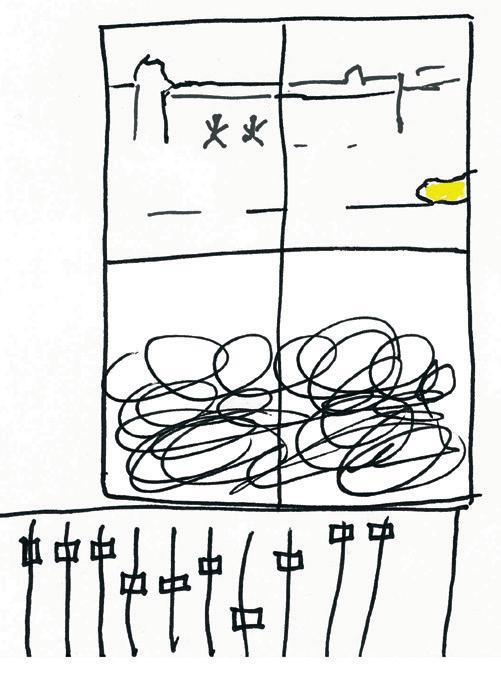

You see, Willy had trouble finding zips. It was a particular problem on suitcases and bags that had lots of patterns on them. Sometimes, to make matters worse, if the suitcase was positioned on a white table, Willy’s Alzheimer’s Disease would play tricks on him. He would see thin, squiggly lines all over the table, as if it was covered in hair! This was, of course, all because the pesky proteins had nibbled through the neurons that controlled Willy’s ability to see patterns clearly.

Sometimes, all of this even made Willy feel like suitcases were taunting him!

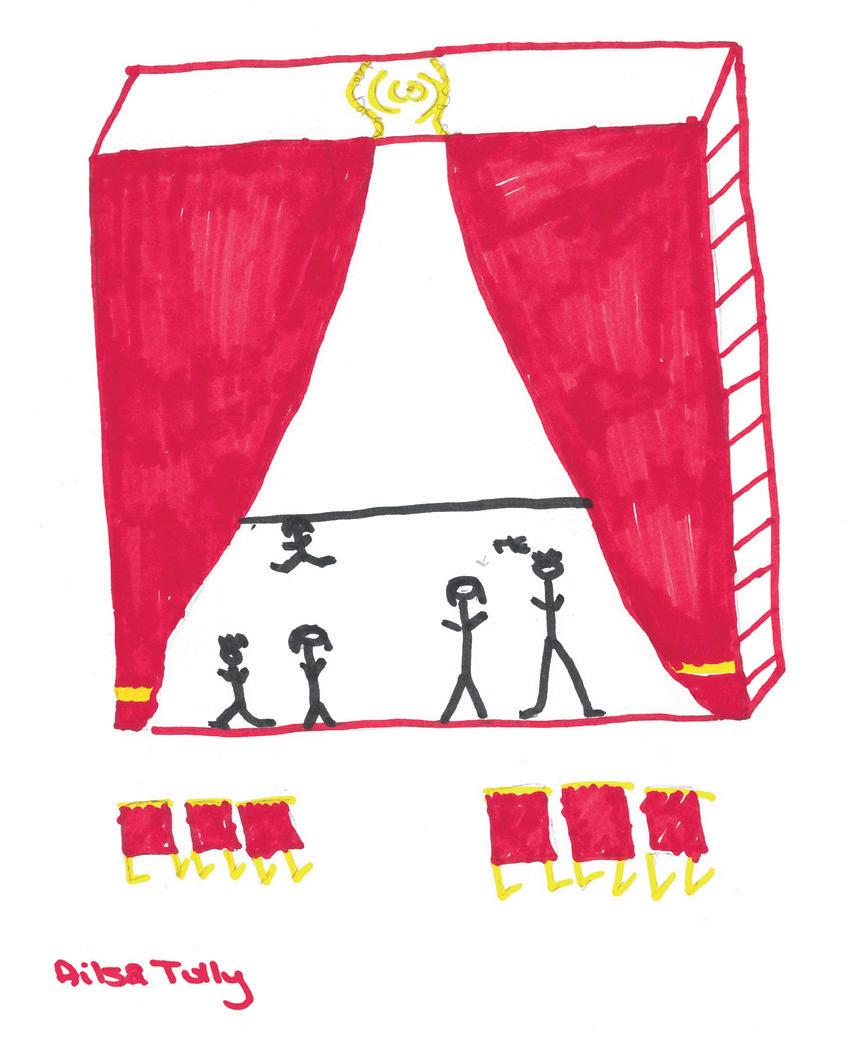

Some of these things were a challenge. (But, remember, Willy has never been scared of a good challenge!) Eventually, with his new friends, Alexa smart speaker, new activities and a proper diagnosis, Willy started to enjoy life more. Several months passed and the Covid lockdown happened. Luckily, at around this time, Willy found out about the dementia-friendly activities at Capital Theatres, as well as other great dementia organisations, like bold, Deepness and STAND.

At Capital Theatres, he got involved with the theatres’ DementiArts magazine, writing articles to help people better understand dementia. He even introduced a podcast to the airwaves. He got to interview famous people like Sally Magnusson MBE and even the author Sir Ian Rankin!

One day, while listening to the Beatles on his Alexa speaker, Willy noticed his foot tapping the floor. His depression was beginning to disappear.

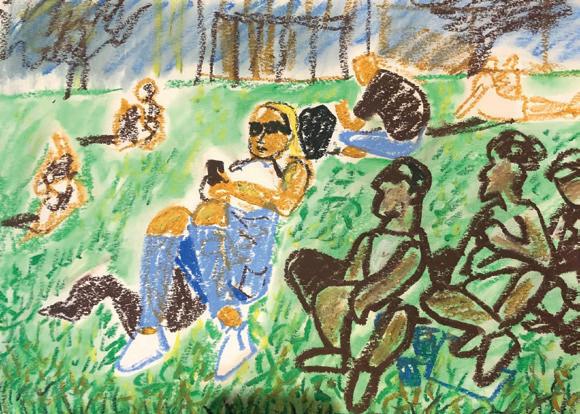

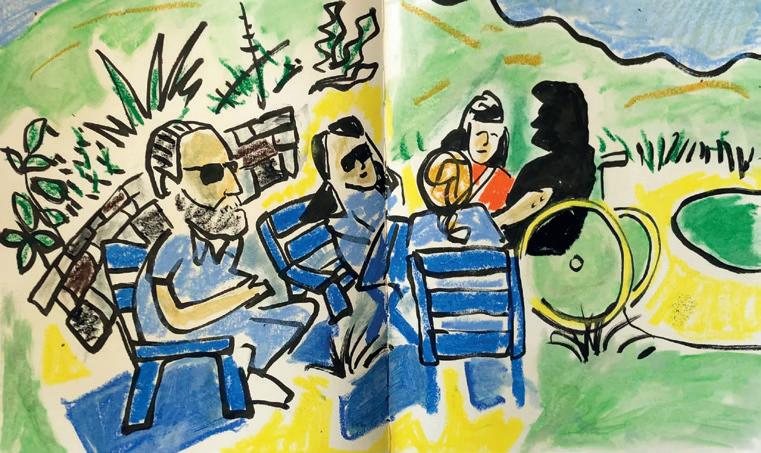

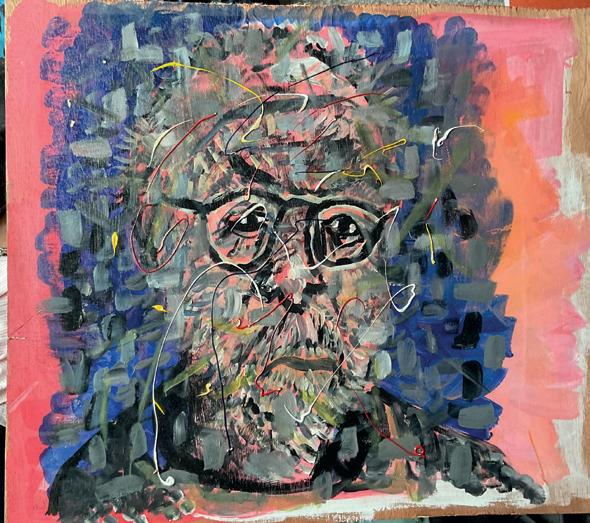

Around this time, Willy’s desire to start drawing came back too. He began drawing every day – scenes and people from around the great city of Edinburgh and beyond.

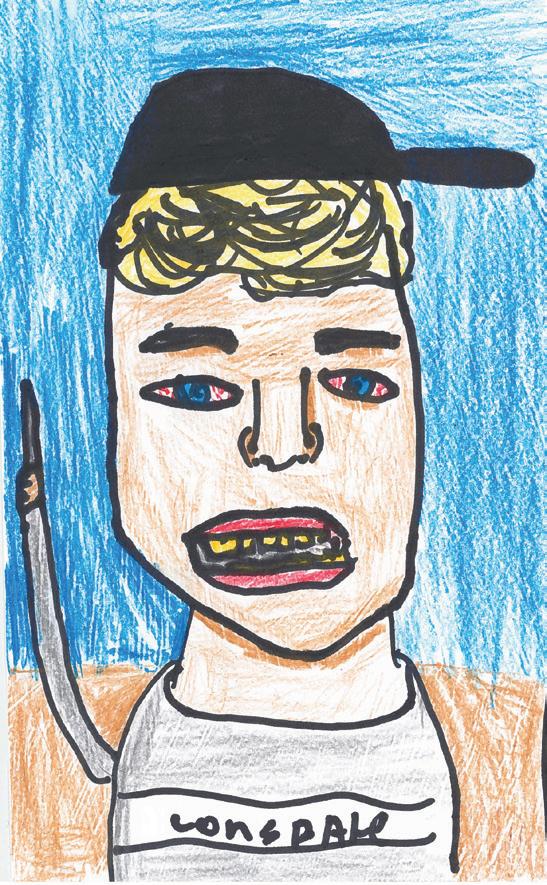

Here is a picture Willy drew of the doctors gathering outside his room when he was in hospital for an operation…

And here’s one of Greyfriars Bobby…

And of Willy himself, dressed as a clown…

His excellent art even won him the Outstanding Older Artist Award at the Luminate Creative Ageing Awards!

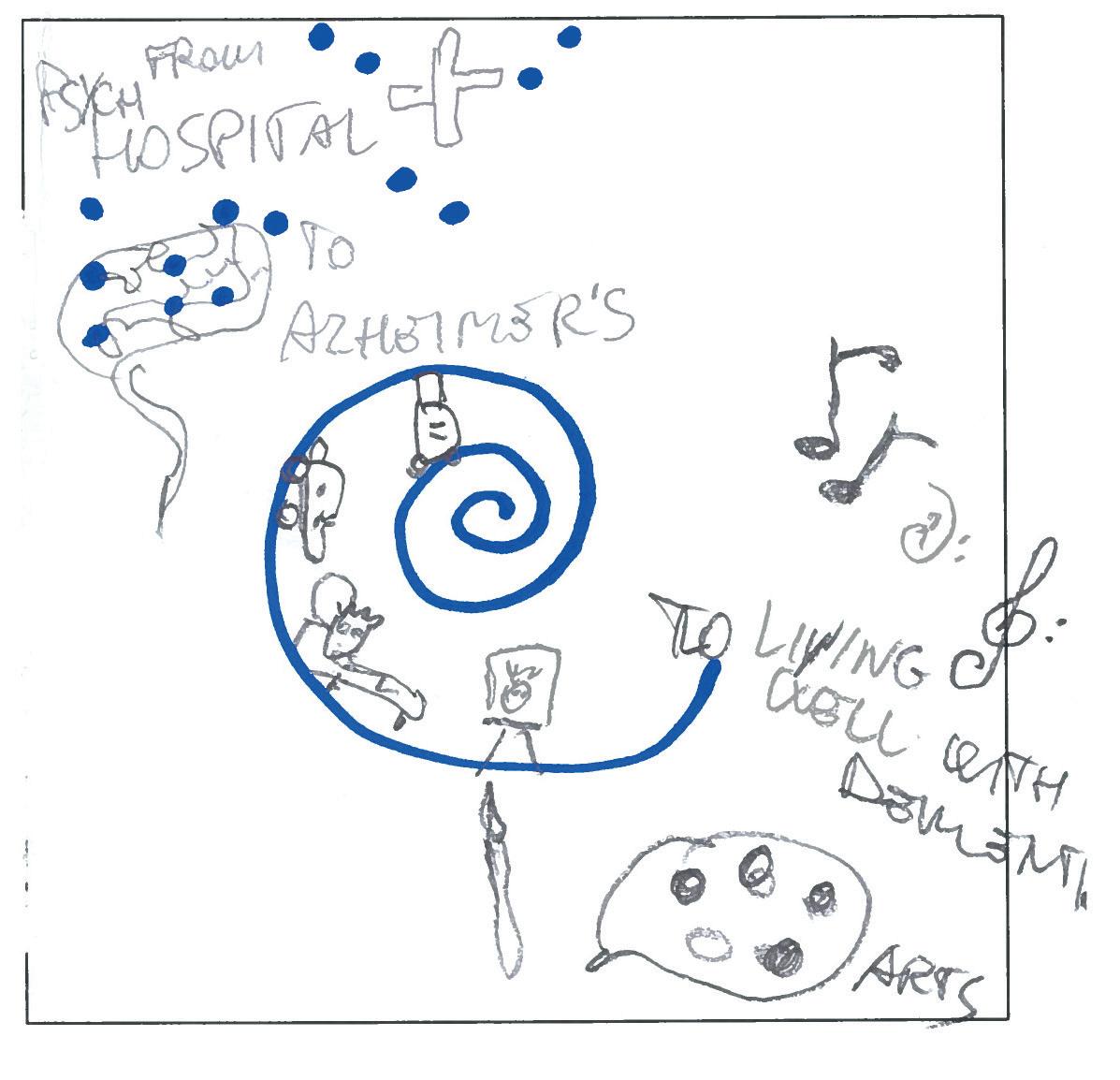

Looking back, Willy’s dementia diagnosis journey had been a twisty-turny one to be sure, with a fair deal of emotional and physical hardship…

And while it was true that Alzheimer’s Disease had taken some things from him, like his ability to see some things clearly, it had still left a lot behind. Willy still loved challenges and a good story; he still enjoyed painting; he still loved meeting new people and hearing their stories; and he still enjoyed the outdoors (although he avoided kayaks).

Also, he was still excellent at telling the stories that others were too scared to tell… and this made him a great person to talk about both the good and bad of living with Alzheimer’s Disease.

And the best thing? His imagination still worked! With Alzheimer’s, Willy could still imagine he was a Formula One racing driver, just as he could imagine he was a pirate fighting away sharks on a desert island when he was a wee boy in Woodbridge!

This has been Willy’s story. It is a story told in an unusual way, but then it is an unusual story! We hope you have enjoyed it. If you have, why not give this book to a friend or family member? We’d love it if you did!

But before we say goodbye, here’s some more of Willy’s own artwork for you to enjoy.

Thank you for reading!

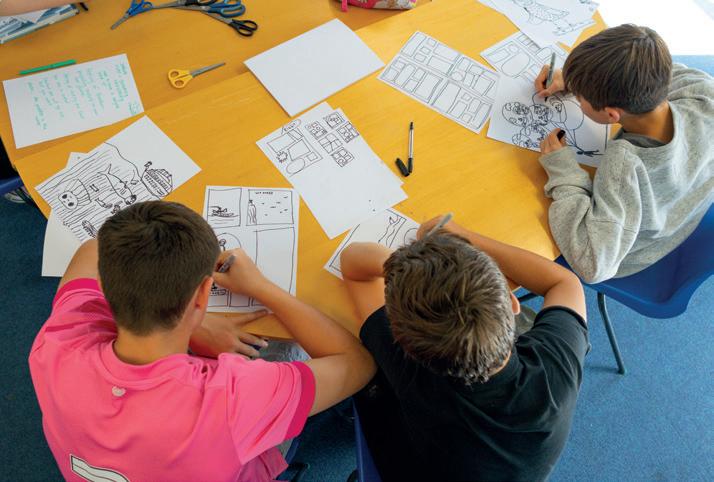

GRAND (Graphic Novels and Dementia) was an intergenerational project that involved a group of five young participants aged between 12 and 17 years old. Of these, the two girls were 13 and 17, and of the boys, two were 12 and one 13. Of the adults, we worked with one person living with early onset dementia (Gerry, who travelled in from Fife); one adult volunteer with lived dementia experience based in Edinburgh (Sheila), and a core team of practitioners, including Willy himself who lives with Alzheimer’s.

Through a collaborative-creative approach, the project sought to construct a graphic novel of Willy’s life, as narrated by Willy himself, through a series of interviews. The process required the children involved to mobilise a broad mixture of skills in order to extract, and artistically present, the story of Willy Gilder’s life before, and during, dementia. These skills included drawing, interviewing, offering prose ideas, and responding to the prompts given by visiting creative professionals, including a professional comic illustrator, author and theatre practitioner.

Through deploying these skills, the project hoped to achieve its core aim: to create a cross-generational ferment for the exchange of ideas, experiences and knowledge. While there was no explicit agenda to this creative-collaborative approach, it was hoped that the process would help undermine, and redirect, received narratives centring around dementia. Equally, by challenging stereotypes and sowing the seed for a more inclusive, de-stigmatised dementia society, the project hoped to build bridges between the generations and foreground what can be achieved when doggedly pursuing a bold, creative approach to intergenerational collaboration.

During lockdown, Valeria Lembo, a PhD researcher on arts engagement and dementia, became an avid reader of graphic novels. These novels brought back into her life the joy of reading for pleasure as opposed to scholarly study. This made her reflect upon the power of graphic storytelling which led to a dream of producing graphic novels that would tell the wonderful stories of people living with dementia who she had met

Being aware of Willy Gilder’s love of art, stories, dementia activism and intergenerational work, she invited Willy to brainstorm ideas for a collaborative project centring on graphic storytelling and dementia, and apply to the Bold mini commission fund.

Willy responded enthusiastically and also suggested orienting the project in an intergenerational direction. Willy and Valeria then invited Alex Howard, writer, editor and dementia-friendly engagement officer at Capital Theatres to come on board for collaboration. The project also benefitted from the input of Adam Robertson (theatre practitioner) and Maria Stoian (comic artist).

The first workshop focused on getting to know each other as a group through icebreaker games facilitated by Adam Robertson. The games slowly moved us from familiarising ourselves with each other to understanding simple and collaborative storytelling methods; for instance, the creation of a whole story by saying one word or a short sentence. Later, Adam introduced a drawing exercise, after which Willy invited participants to draw something meaningful to themselves and their identity. We then shared these drawings with each other. The main feedback received was that participants very much enjoyed the session. Young participants particularly enjoyed the games and the time spent drawing. One participant wrote that they wanted more games.

For the second workshop, we focused on sharing stories more broadly. Our initial plan centred around prompting the recruited participants with dementia to share their stories with the young participants through short interviews. Unfortunately, two participants with dementia who planned to attend were ill and we had to change plans. In the first half of the session, Alex interviewed Willy about his life, loosely dividing the interview into three sec-

tions: Willy’s life as child; his life as a career-aged adult; and his ‘new’ life with dementia. The young participants were then invited to take graphic or written notes. In the second part, the young participants asked questions to Willy through a game. Participants said that they particularly enjoyed the opportunity to ask questions to Willy directly, and enjoyed learning about his life.

For the third workshop, we focused on comic drawing and story layout, delving more deeply into the modes and styles of graphic storytelling. The workshop started with Willy himself facilitating a drawing exercise. The comic artist Maria Stoian facilitated the rest of the workshop which focussed on turning Willy’s life history into a comic. Starting with the drawings and notes about Willy’s story made in the previous workshop, participants were then asked to select what they believed were the most significant scenes to use for the final story. Maria shared techniques about her creative process, how to work on the story layout graphically, and how to make specific creative choices. In their feedback, participants wrote that they enjoyed drawing very much; that they enjoyed the process of turning stories into comics, and that they wanted to know more about this.

Willy, Alex, and Valeria facilitated the fourth workshop. Responding to previous feedback, we started with more physical-based games, like using a ball game as a prompt for speaking, before gently moving the focus towards narrative editing. We invited

participants to position themselves in front of laminated comic-style prose extracts about Willy’s life, written and collated by Alex based on conversations from earlier sessions. These were to be divided into the three main parts phases of Willy’s life (childhood, adult life, new life with dementia). Participants then decided, in turn, what narrative fragments they would like to keep and what they wanted to omit for the final printed novel. Timelines were discussed, together with the importance of the relationship between image and caption. Once all in agreement, we then invited all participants to choose one more drawing that they wanted to refine, colour, improve, or work on if they wished –their ‘best’ drawing. In the last part of the session, we all drew and coloured together by listening to music and having chats and refreshments. In this session, we also had the opportunity to listen to Gerry King, a participant living with dementia, who shared some snippets of his own life before and after a dementia diagnosis. This also allowed Gerry to draw his own pictures of both his and Willy’s dementia journey, and allowed the young participants to ask more questions.

As Alex often says, these workshops were full of many ‘little moments of magic’, where participants immersed themselves deeply into the flow of the creative process. There were also many moments of pure joy, and laughter, as well as deep listening and sharing. From the feedback received, participants particularly loved the opportunity to draw; to get to know new people; to learn about graphic storytelling and the process of turning stories into comics, and the possibility of knowing more about Willy and Gerry’s stories by asking questions. Physical and creative games were a very important part of this process, in order to facilitate a fun atmosphere where the group could know each other better and establish connections. Quiet moments, however, were very important too.

It was important to leave a margin of flexibility to adapt to the group’s needs, for instance changing plans at short notice if a participant living with dementia was unwell that day, or if participants needed extra time to get to grips with their own creative expression through theme-free drawing. Participants showed enthusiasm towards the final goal of the project, which is publishing the graphic story with their illustrated snippets, and towards learning the tools from a team of experts on how to tell stories graphically. Willy and Gerry particularly relished the opportunity to share their stories with younger participants while having these participants ask questions directly. This shows that projects of this type can facilitate encounters among different generations where dementia is approached through genuine listening and curiosity rather than stigma.

GRAND was an ambitious project that sought to pilot an intergenerational graphic storytelling series of workshops and activities. As a team, we all believed it had great potential to be carried forward and proposed as a creative activity within a range of different settings. Below, we will detail some challenges and recommendations for the future after this experience:

Recruitment for this project was challenging, especially finding participants living with dementia. For successful recruitment and sustained participation, we advise working with existing groups of young participants and people living with dementia; for instance, matching a class, or an after-school group with a Meeting Centre group. This would prevent participants having to add extra commitments to their diaries and would simplify the administrative setup of the project.

• Age

Because of recruitment constraints, we had a group of young participants of very different ages (from 12 to 17-years-old). For the future, we would advise having more homogenous groups with smaller age gaps. Conversational activities work very well with older groups (15-18-years-old) while younger participants (12-14-years-old) often prefer an activity structure organised around a blend of more physical games.

• Engagement

We chose to have one monthly workshop session so as to not overload participants with extra commitments. However, a reduced time gap between sessions might allow a more sustained engagement between one session and the next. We also advise that future practitioners find simple ways to encourage engagement at home between one session and the next that can adapt well to their groups’ needs. Icebreaker games at the beginning and at the end of each session work

very well for group bonding. Participants appreciated both moments of laughter, silly stories, and physical games as well as the quieter moments where they would just sit and listen to the music while colouring and drawing. Funding allowing, we would advise having the same team of practitioners attend the whole project. Equally, flexibility, at session-level, is really important, to adjust to participants’ needs and health issues on the day. Consultation with a childhood psychologist would also be useful, to help advise on how to debrief participants in case difficult topics arise during the workshops. Furthermore, we advise Dementia Awareness training and Intergenerational Practice training for all facilitators.

A selection of feedback quotes

Q ‘What did you enjoy today’?

A ‘I enjoyed all of the stories that we made and I also liked the art part of it and the games were very fun’

‘Meeting new people. Amazing storytelling from the use of simple words’

‘I really enjoyed the encouragement for everyone to find their creative side and the opportunity to tell silly stories’

‘Meeting new friends. Loved the creative storytelling. It felt so peaceful and mindful when we drew pictures’

‘Drawing and the games at the start’

‘The drawing’

‘Producing a page so quietly’

‘Making comics’

‘Talking to Willy and Drawing’

‘Hearing about Willy’s experiences and thoughts’

‘Drawing the three pictures and listening to the interview’

‘I enjoyed hearing Willy’s story but I also really enjoyed having the opportunity of asking questions about advice and regrets and changes in his life’

Q How could things have been better?

‘More drawing’

‘Getting to start quicker’

‘I really enjoyed all of the activities and things to do but I do wish we could have done more games’

‘Nothing. It was really fun’

‘More people. Room is always a bit chilly’

Q ‘What else would you be interested in’?

‘More drawing’

‘Drawing anything we want in a comic’

Participants’ questions to Willy and Gerry (selection)

- ‘What is some advice, something you’d want to say to people newly diagnosed with dementia?’

- ‘What made you realise you could still live with dementia?’

- ‘What age did you start to draw?’

- ‘What is something that you’d do that dementia stopped?’

- ‘Do you have any pets right now?’

- ‘What’s your biggest regret in life?’

- ‘What’s your biggest achievement?’

This project has given me the opportunity to share my story with young people, who’ve asked me the most searching questions. It’s been a delight to be challenged, and to have a chance to explain how a diagnosis of dementia has affected my life. My brain disease has compromised my verbal memory but left my visual memory intact. Here are, literally, some of my visual memories.

It was such an honour to work on this ambitious project and I hope this can inspire more people and groups to write and illustrate their stories about dementia. I am deeply grateful to Willy and Gerry for sharing their stories and to the young participants for their curiosity, attention, engagement and creativity.

It was fantastic to be involved in such a bold and ambitious creative project where the fruits of our creative labours can be memorialised in print. Giving legitimacy to each dementia journey is a fundamental right for all those living with the disease, and there’s no better place to instil this idea than in the young. There are things we would do differently – notably around the selection of age groups, group activities and practitioner delivery – but I truly believe we’ve started something which can be built on and nurtured by others.

Made possible with mini commission funding from Bold (Bringing Out Leaders in Dementia), with support from Capital Theatres.

GRAND (Graphic Novels and Dementia) was a Bold mini commission by Valeria Lembo, Willy Gilder and edited by Alex Howard, in collaboration with Adam Robertson and Maria Stoian. Design, space and workshop support from Capital Theatres.

If you have any questions for Willy, or would like to know more about this project, contact Valeria Lembo at valeria.lembo@ed.ac.uk, or Alex Howard at alex.howard@capitaltheatres.com

For more about the work of BOLD (Bringing Out Leaders in Dementia), visit: ed.ac.uk/health/news/2020/bold

For more about the Capital Theatres dementia-friendly programme, visit: capitaltheatres.com/take-part/dementia-friendly-work