who

who

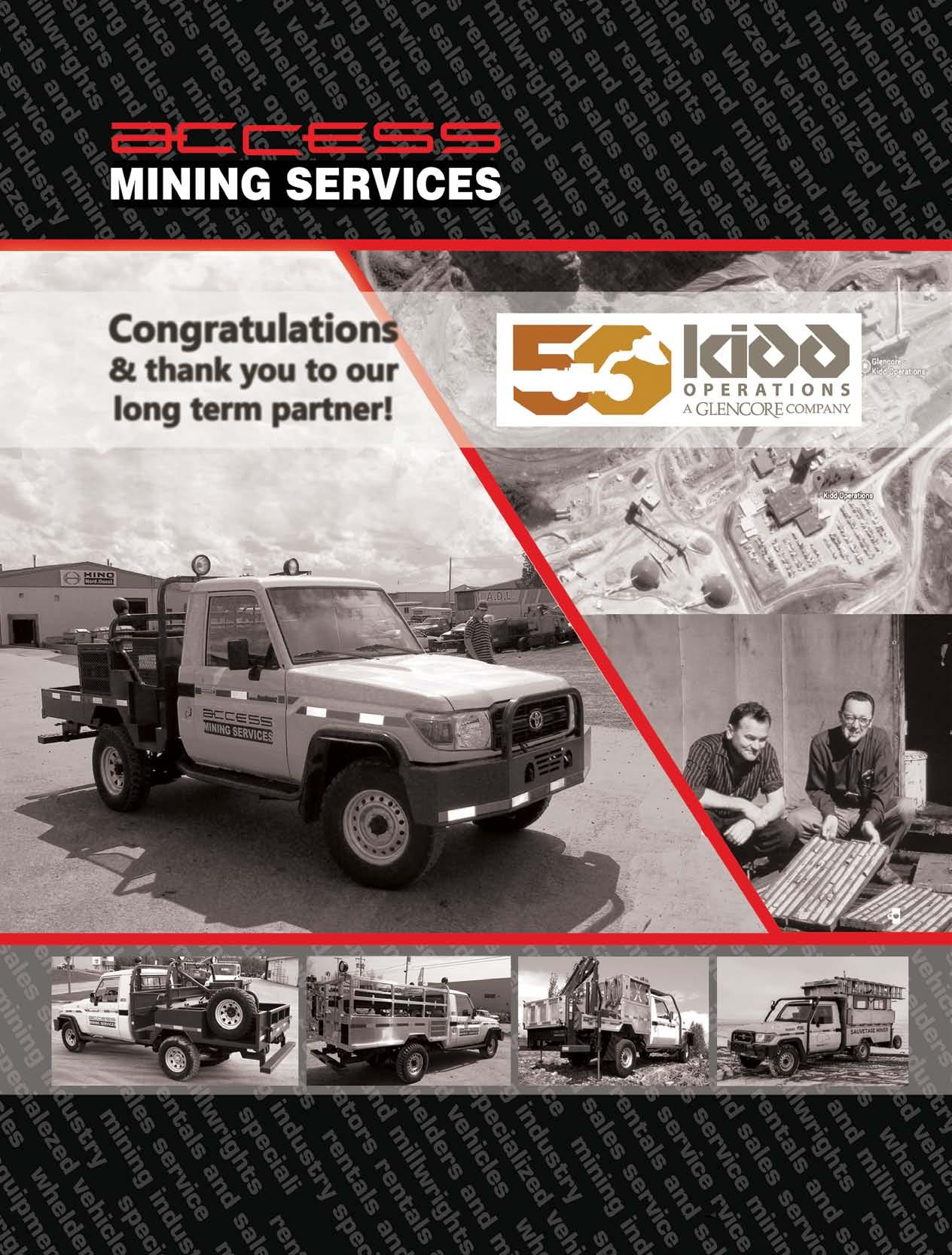

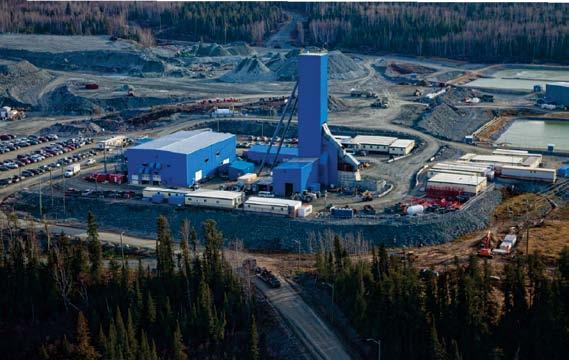

journey from core to ore has many challenges. When engineering commenced on the Kidd Mine D No. 4 Shaft, we knew this was a special project. Sinking concurrently from two horizons in an operating mine made this project as complex as it was technically challenging. Cementation is very proud to have played a key role in the development of Kidd’s Mine Deep operation as the engineering company and sinker for the Kidd Mine D No. 4 Shaft. Congratulations Glencore and everyone at the Kidd Mine on your 50th anniversary.

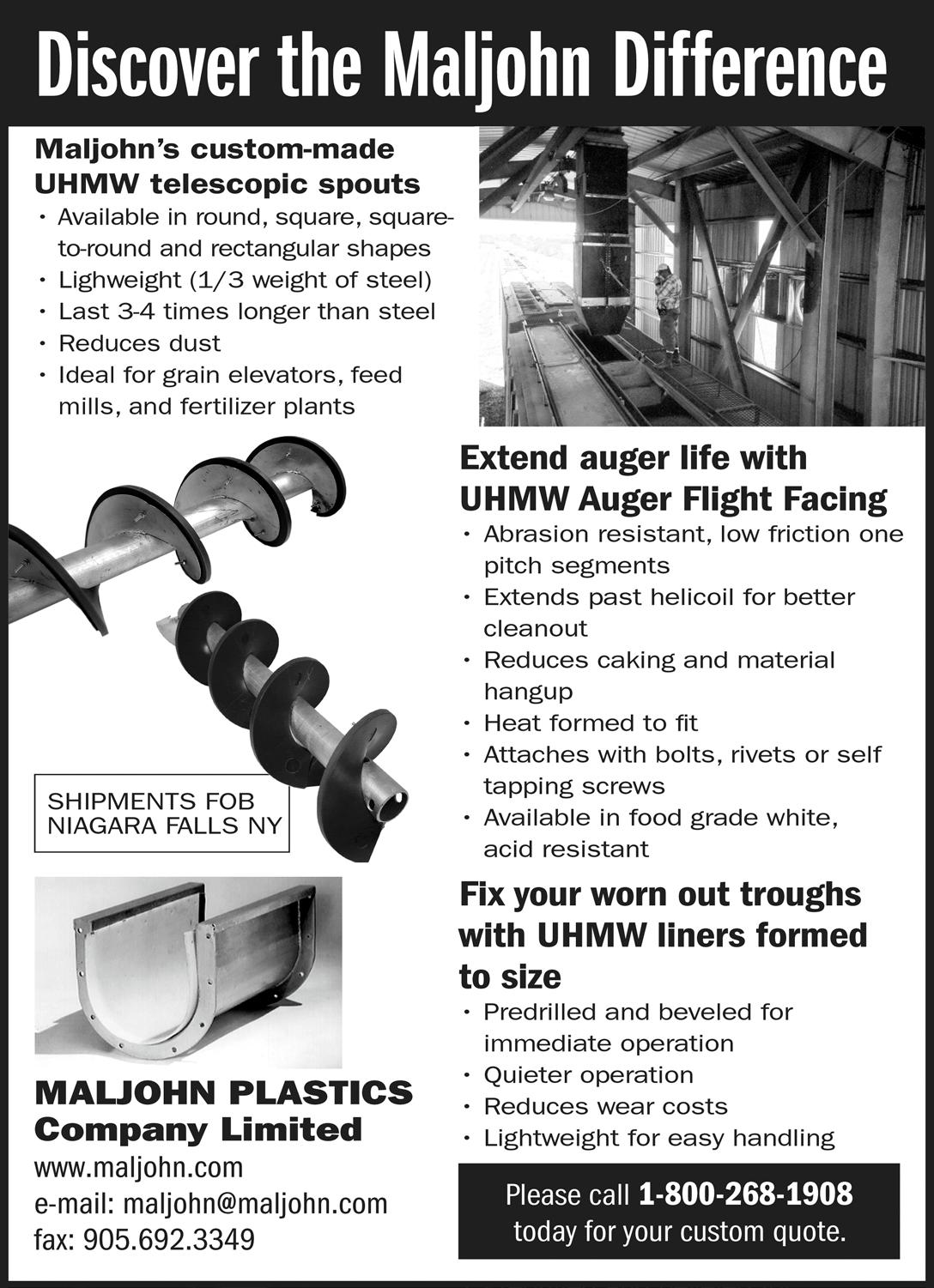

Process

Materials

In-plant,

Most mining executives would dance in the streets if they got 50 good years out of their orebody. With five de cades in its rear-view mirror, Kidd Creek can not only rejoice, but revel in the fact that the world’s deepest base metal mine has life in it still. That life to date has led to an unimag inable production record – extraordi nary engineering accomplishments - homespun expertise that is shared around the world – an unwavering commitment to environmental stew ardship - and a commitment to the highest standards of safety that other industrial operations can merely envy. In the pages that follow you will read about the mine’s discovery in the ear ly 1960s; a royal photo opportunity; a herd of majestic mammals that de lighted children and adults alike; the mysterious prospector who vanished after erecting a ramshackle home stead above the orebody; one of many multi-generational Timmins families who have been part of the payroll; and

much, much more.

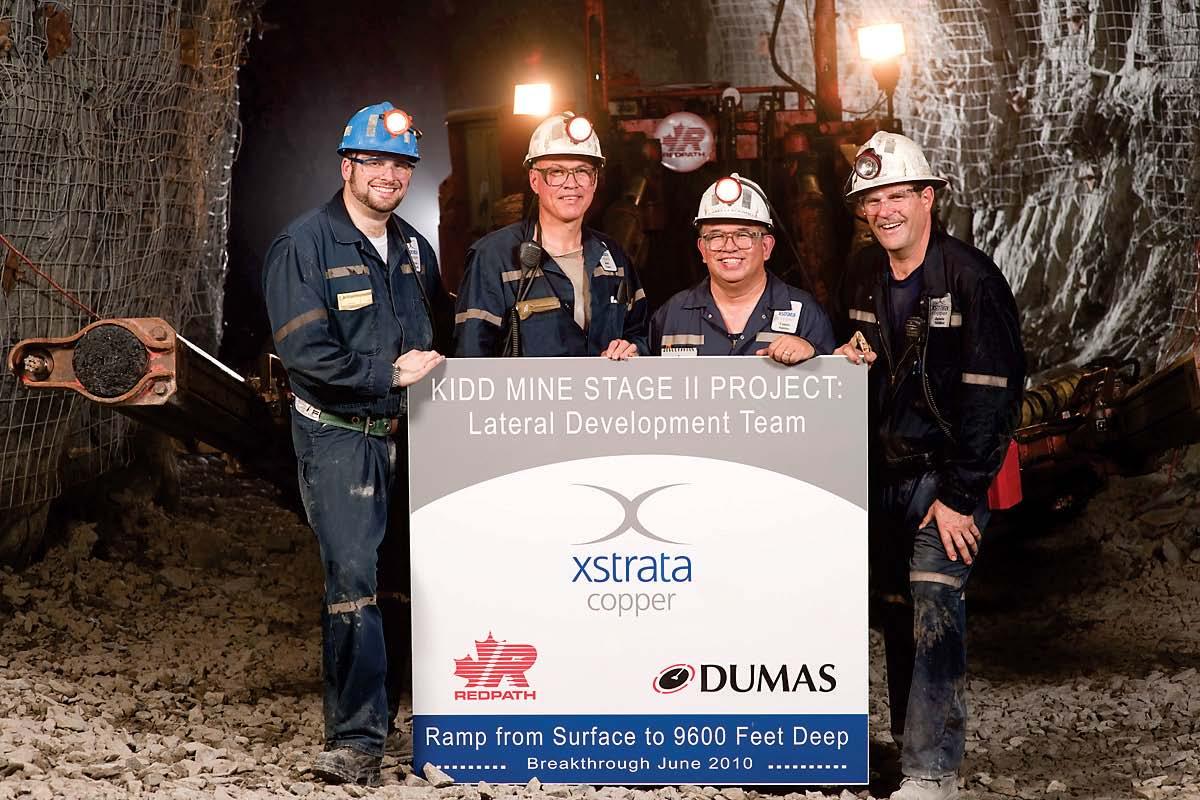

Today, as the company advances deep underground to the 9600 foot level, the man in charge of that undertaking is balancing both short and long term expectations for the workforce and the community.

“A resource has a finite end,” says Kidd Creek’s Mine Manager Steve Badenhorst, who took over the post in January of 2016 from Tom Semadeni. He points out that a decision late in 2015 to target the 9600 level extends the mine’s life an extra year to 2022.

“Unlike an agricultural business, you can’t hope that the gold or copper or zinc from a mine is going to stay there (and sustain itself) forever. After 50 years Kidd definitely has an orebody that extends deeper, but the infrastruc ture was developed to extract the top 1100 feet. We have extended that over a long period of time to where we are now reaching the end of that infra structure.”

Badenhorst says there is more to the

Kidd Creek orebody, but the company would need to develop an expensive new infrastructure and a new hoisting system to go after that material.

Even if prices for copper and zinc rose dramatically, the ore is so deep, and so expensive to extract that it would be counter-intuitive to engage in the pursuit just because it’s there.

In the interim, the company is taking time out in 2016 to reflect on the ex traordinary impact Kidd has made on the city of Timmins and surrounding area over the past 50 years.

And while the final chapters have yet to be written, the opening chapters, all five decades, are remarkable indeed. With more than 20,000 employees over those years, and a staggering in vestment in equipment, contractors, and the community – Kidd Creek has been a multi-generational economic engine for a city that once believed it would live and die on gold and a mod est lumber industry.

“The articles in this magazine are but a fraction of the many thousands of unique and engaging stories that will be shared for generations to come,” says Badenhorst.

While the future of Kidd has an im pending and inevitable finish date – its past is timeless.

There is no other mine in the world like Kidd Creek.

Steve Badenhorst says he recently described the Kidd mine to his 17-yearold son by characterizing it as a large building that takes years to constructbut it’s never finished.

“Imagine a scenario where you keep going higher and higher and adding scaffolding and someone says: ‘Okay, that’s the height’, and someone else says, ‘No, no – with the right technology we can go higher’.” Indeed. The prevailing attitude is “Look what we’ve al ready done – we can do more.”

While the pride, the ingenuity, and the determination may be in abundance, the reality is that the cost of extending the mine’s life would far exceed the return on that investment.

“Even now there are people who are telling us we can go a bit deeper and that’s driven by this sense of achieve ment around the challenge that has al ready been met.

Most of the longer-serving employees have been part of that challenge for many decades,” says Badenhorst who took over as Kidd Operations Gener al Manager in January of 2016 from Tom Semadeni who held the post for eight years.

“They’ve taken Kidd through these major capacity gaps where others sug gested you could never get through that,” he adds. “It’s remarkable.”

When it comes to the short-term fu ture of Kidd, he is careful not to proj ect any false expectations.

“You can’t farm a resource. In essence it’s the next seven or so years that we have to manage to get the best pos sible extraction - and then if we look

wick Mine in Bathurst, New Bruns wick. The lead-zinc-copper mine was discovered in 1953 and started production in 1964 before closing in 2013 just short of its 50th anniversary.

“In the Brunswick case they mined everything out over the course of its life to a point where there are limits to what you can mine economically,” said Badenhorst.

“At the final stage of the mine, they went back and said ‘can we mine what is left and still make money?’ For ex ample, are there any areas above us where we can possibly go through and access economic ore?

I think it gave Brunswick an extra two years of life. Whatever you do, it is still finite, it will end at some point.”

What about commodity prices? “The realistic one (chance of keeping the mine open longer) is if there is a rise in commodity prices. We don’t be lieve that energy prices will drop –

so input costs are largely where they are.

If we go to where com modity prices are now, we are looking at 2005/2006 levels, and when you com pare that to 2015 levels, if you want to be economic you would have to ask staff to undertake paycuts back to 2005/2006 levels and that is not attainable.”

Badenhorst says that on the other hand, if com modity prices were to rise, then you could think about going after the deeper material.

He cautions however, that a jump in prices would be counter-intuitive because the deeper you get, the higher the cost.

“For example, a skip that we use to pull material from the bottom of the mine, if it can handle 40 tons on the upper levels, it might only take 17 tons on the lower levels. You can’t keep mining economically at those lower depths.”

“The second biggest cost we have in terms of energy consumption is our ventilation fan system. It’s very hot down there. To ventilate it to make it safe for people to work is going to consume a lot of energy.”

Badenhorst says you can do many things on the input side of costs. Kidd is always looking for ways to reduce ventilation costs which in turn will re duce energy consumption.

In the interim, technology advance ments are focused on reducing hu man interaction by remote mining or scooping. “We can remove the opera tors and put them on surface (9600 feet above) while the machines are on the lower levels. It reduces the cost of normal breaks and shift change times,” says Badenhorst.

New Mines:

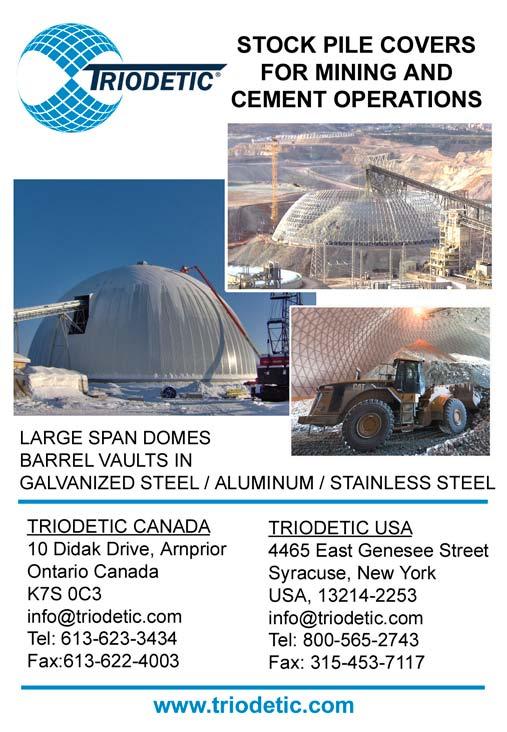

• Research and development laboratories providing customized ready mix, cement and cementitious solutions

• Solutions for quicker construction times for concrete headframes, concrete lined shafts and underground structures

• Worldwide logistics services delivering cement and ready mix to hard to get at locations

• Backfill solutions including: cement products, plant operation, portable plant possibilities and technical support

Mobile ready mix and wet shotcrete services and products provider

Portable crushing and screening plant capabilities

Mine Closure:

• Providing assistance, support and screening solutions for mine tailings reclamation projects

• Products and technical expertise for soil remediation, solidification and stabilization solutions

A strong commitment to health, safety, and environmental standards.

By partnering with Lafarge

to bring innovation, performance and certainty to your new mine, operating mine and mine closure projects.

more information,

years

operations!

There’s an ancient truism about min ing. To find an orebody, pitch your tent in the shadows of another.

On Nov. 8, 1963, a young Canadian geologist, Ken Darke, hauled a 2-ton diamond drill 25 kilometres north of the prolific gold mining town of Tim mins, Ontario into Kidd Township. One of the first holes he spotted was logged as Kidd 55-1; and when the core was pulled the following day, Darke and his drill crew stared in amazement. It contained a foot of solid copper. More than 3,000 kilometres to the south, a struggling American com pany, Texas Gulf Sulphur, was poised to become the operator of one of the world’s richest deposits of zinc, cop per, lead, silver, tin, cadmium and in dium.

When Darke shared the news with senior Texas Gulf officials, they couldn’t get on a plane fast enough. Vice President and Manager of Ex ploration Richard Mollison and Se nior Geologist Walter Holyk quietly

flew to Timmins; arranged a swamp buggy; and headed off to view the drill core at the site.

They were equally amazed. The pair agreed it was a major discovery. They ordered drilling to be put on hold; the discovery site disguised; and the drill moved to the north where a dummy hole was drilled.

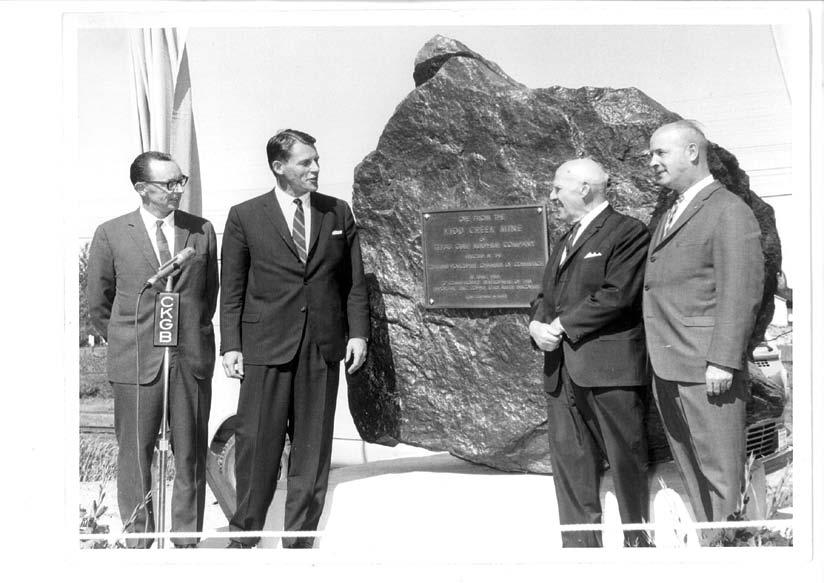

Seven additional holes were drilled in early 1964 before the news was of ficially announced on April 16, 1964.

Only the discovery core was ever as sayed (in a U.S. lab) before the news. It wasn’t until December that assays on 55-1 were released. The official as say was extraordinary. That discovery hole was included 602 ft. averaging 1.18% copper, 8.1% zinc and 3.8 oz./ton silver.

Subsequent drill holes delivered even better results.

In a published interview a decade af ter the discovery of the Kidd Creek orebody was announced, P. Ray Clarke, vice-president, Texasgulf Inc. and Vice-president and General Man

ager of Ecstall Mining Limited, (then Kidd’s name) reflected on 1964.

“The news on April 16 of the large, rich deposit of zinc, copper and sil ver beneath the muskeg near the Town of Timmins created excitement across several nations. It started one of the wildest land rushes ever seen in the quiet Northern Ontario woods. It caused hysterical activity on the American and Canadian stock ex changes. It changed Texasgulf from a sulphur-fertilizer company into one of diversified international magnitude,” said Clarke.

And it changed Timmins in a dozen different ways, all for the better.

The company’s story began in 1909 when a small operation was created to mine sulphur in the southwestern United States.

Texas Gulf Sulphur Company Ltd. grew into a major sulphur producer, but by the 1950s, it faced hard times and declining reserves.

It decided to look elsewhere for sul

Unifor Local 599-T On-site Office

P.O. Box 1931, Timmins, Ontario, P4N 7X1 Tel: 705 235 8121 ext. 7599 Unifor599@glencore ca.com www.timmins599.blogspot.ca/

For a base metals mine, with finite resources at depths seen nowhere else in the world, to exist 50 years is a remarkable achievement. Kidd continues to thrive, and still proves to be a decent and safe place for all to earn a living.

One of the main drivers for Kidd’s success for the past 50 years and counting has been its employees. A more diversified and innovative group you would be hard pressed to find! From the late 1960’s up to the present, whether you worked underground or in any plant, you could always feel a sense of comradery. This is self evident by the numerous generations of families that have enjoyed long careers here. More than 20,000 employees have walked through our gates as this was and still is one of the city’s biggest employers. Both Kidd’s employees as well as our employer have been major contributors in many ways to the success of this community and look forward to continuing that tradition.

On behalf of Unifor Local 599 current and past membership, I would like to congratulate Kidd Operations on reaching this golden anniversary.

Paul Fillion Unit Chairsights on Canada under the Canadian Shield Project.

The program was a failure and had been sharply reduced when Darke was sent to Timmins in early 1963 to supervise a drilling program.

The main target was a large anomaly in Kidd Township. Anomalies occur when material in the ground gives off a reading different from the surround ing area when geophysical equipment passes overhead.

The readings were so strong that for years airplanes and helicopters hired by mining companies in the area used them to set their instruments before flying off to do surveys. Apparently no one thought the anom aly worth investigating until Texas Gulf came along.

Remarkably, Mclntyre Porcupine Mines Ltd. was cutting trees on the site for use in its Mclntyre Gold Mine, one of the largest in Canada and a mainstay of the area economy since its discovery in 1909.

When drill crew foreman Rene Ger vais brought Darke part of the core on that night of Nov. 9th, the young ge-

first was to perform more drilling to prove the first hole wasn’t a ‘fluke’ and the second to keep the find secret until it could acquire the land around it.

What became one of the most impor tant mineral discoveries in the history of the world was on land the discover er didn’t own; Texas Gulf merely had an option on the four-claim, 160-acre property.

In fact, there were three major owners to contend with, as well as numerous small pieces of property to acquire and Crown land to be staked.

In the months that followed, Texas Gulf managed to acquire 60,000 acres by staking and buying property. While Darke confined the drill crew to the site for weeks, the men needed food and other supplies.

Diamond drill core was shipped to the U.S. for storage even though there was a laboratory within 143 km of Timmins.

Still, speculation grew as what was going on in Kidd Township. Eventu ally, prospectors and other companies started to tie up ground near the find

and in the adjoining townships. The Jungle Telegraph in Africa has nothing over the rumor grapevine in mining circles.

The bible of Northern American mining journals, the Northern Miner weekly in Toronto, got wind of the story and managed to put together enough facts that the company agreed

The story was written on April 13 and carried in the edition of April 16. On the same day, Texas Gulf made a for mal announcement in New York City. The news sparked the biggest, wildest mining rush in Canadian history.

That the find was made in an area where gold had been found as early as 1906, where the three giants of Ca nadian gold mining, the Dome, Hol linger and Mclntyre were still in pro duction; and where more than 50 gold mines had been born and died just added color and excitement to events.

There were huge areas that couldn’t be staked because they were held by mining companies, individual pros pectors and veterans of wars around the turn of the century but every square inch of open ground in eight 36-square mile townships was staked or bought (sometimes flipped several times for ever higher amounts) and soon every diamond drill rig in Can ada and the northern U.S. was punch ing holes into the ground.

Darke had managed to stake all the open ground he thought the company needed and he told it as far as he was concerned there was nothing of value on the land he passed up.

History was to prove him right. To day, a half century later, no one has found another major base metal ore body in the Timmins area.

At the time of the rush and with penny stocks soaring in value with the mere announcement that companies had

Whether your equipment is highly complex or fairly simple, you need your machines to work.

NTN has a solution that puts your mine at ease.

Whether you work on top of the world or deep in it…

Cont’d from pg. 14 acquired ground near Kidd Creek (of ten 15 and 20 miles away), the theory was that the orebody was a ‘splash’ and there had to be other parts of it to be found.

A study conducted by the Geological Survey of Canada, the Ontario Geo logical Survey and Falconbridge Ltd. was released in 1995, proving the ore body was a geologic ‘tear,’ a self-con tained and isolated occurrence. The millions of dollars bet in the stock market frenzy of the remainder of 1963 and throughout 1964 on specu lation that there were more Texas Gulf orebodies around Timmins proved pointless.

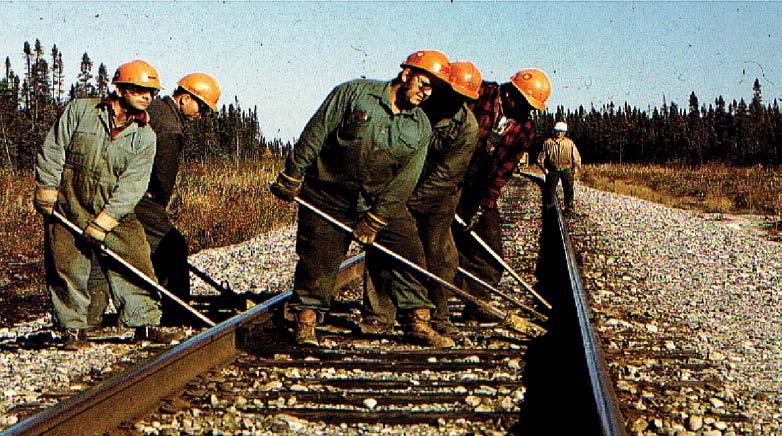

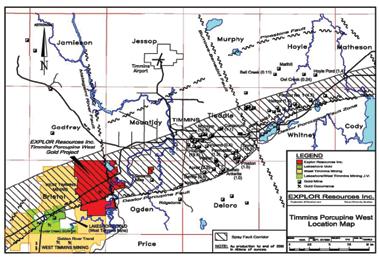

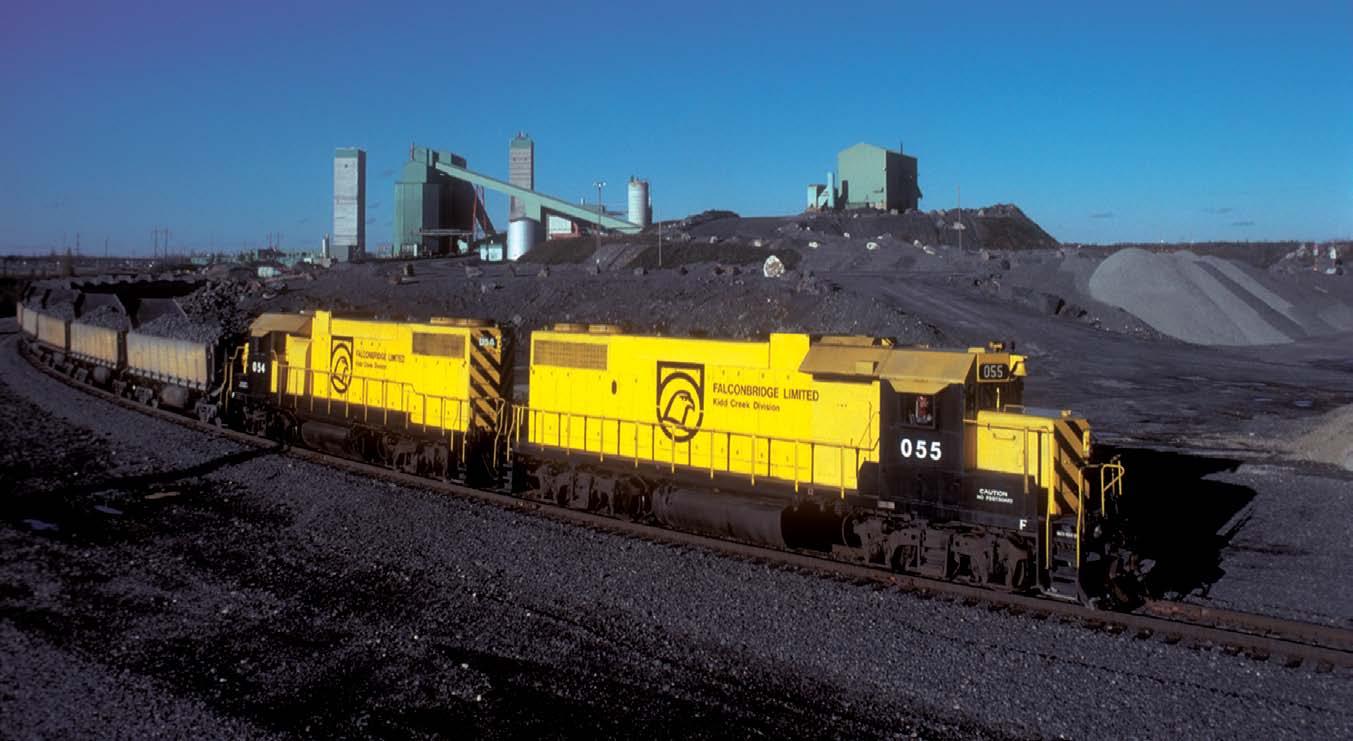

Experts determined the Kidd Creek deposit was originally formed on the seafloor around hot springs 2.7 billion years ago, similar to how black smok ers form on the seafloor today. While exploration was occurring all around it, Texas Gulf was busy se lecting a site for a concentrator 17 miles east of the find. They needed to build a highway from Timmins north through the muskeg to the discov ery, along with a railway between the mine and metallurgical site that would be home to the concentrator and the many good-paying jobs that went along with it.

The railway started hauling ore on November 7, 1966 and nine days later, the first ton of ore went through the new concentrator.

The orebody was so unusual, yielding copper, zinc, lead, silver, cadmium, tin, as well as sulphuric acid and in dium as by-products, that people from Russia, China, Chile, U.S., Mexico

and other mining nations came to study it.

Not surprisingly, gold was found near the metallurgical property and for a few years it created an additional rev enue stream for the owners.

Nothing like Kidd Creek has been found anywhere else but numerous other mining companies continue to explore in and around Timmins and the rest of the Precambrian Shield.

Despite its wealth and reserves, Kidd Creek has had six owners. Texas Gulf (by then Texasgulf Inc.) sold in 1981 to France-based Society National Elf.

It immediately sold the Canadian mineral properties to the Canada De velopment Corporation (controlled by the federal government) and in 1986 Canadian mining giant Falcon bridge acquired the mine.

Swiss-based Xstrata plc acquired Fal conbridge in August 2006.

It merged with fellow Swiss-based Glencore plc in May of 2013 and be came Glencore Xstrata.

The merger created one of the world’s largest natural resources groups, ex tending through more than 90 com

modities from copper to barley and from oil to vanadium. The company employs roughly 181,000 people across 50 countries.

Glencore Xstrata plc subsidiary, Xstrata Canada Corp., announced that effective July 30, 2013, it had changed its name to Glencore Canada Corporation.

Glencore Xstrata was renamed Glen core plc at the AGM in May 2014. Glencore plc is an Anglo–Swiss mul tinational commodity trading and mining company headquartered in Baar, Switzerland, with its registered office in Saint Helier, Jersey. It is one of the largest commodity traders in the world.

On July 16, 1996, Frank Pickard, 62, president and CEO of Falconbridge told a gathering of Timmins civic and political leaders he hoped the Kidd Creek Mine will be here “30 years from now.

I won’t be here but the mine could be.” He was out by just four years, the fabulous mine is slated to close in the first quarter of 2022, after 56 years of production.

was $270.5 mil lion.

In 1974 more than 60 per cent of the company’s earn ings came from Canada. Yet, Fogarty saw a potential for the mine that would have again changed the com pany. In a speech on July 19, 1974 to the New York So ciety of Security Analysts, Fogarty revealed his vi sion.

“New opportuni ties include ship

Were it not for a tragic plane crash in 1981 and the loss of several senior Texas Gulf officials, North Ameri ca’s most prolific mining community might have been so much more.

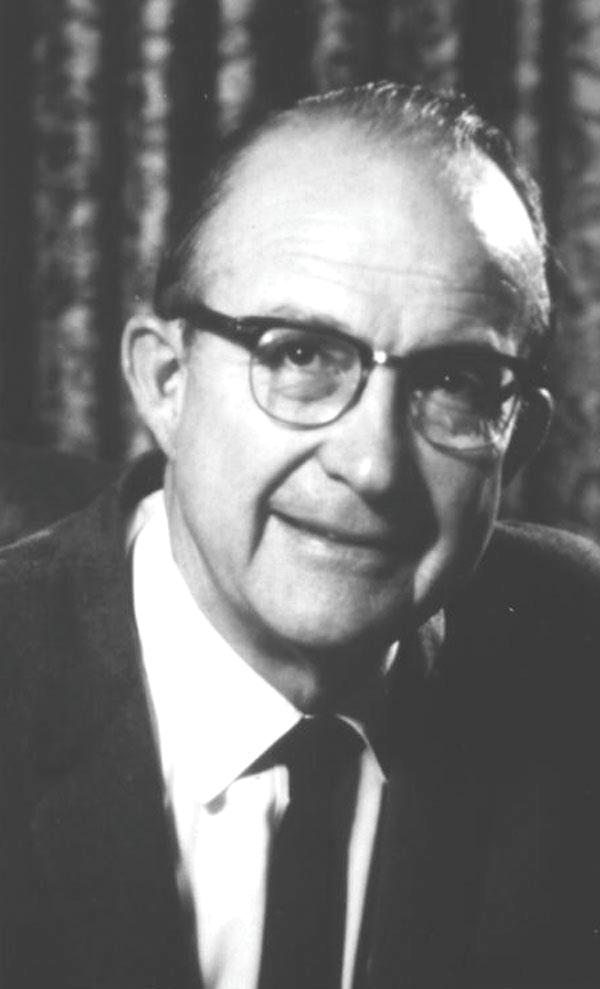

Dr. Charles (Chuck) Fogarty was a vi sionary businessman who spent eight years at the helm of Kidd Creek. His biggest dream would have changed the mining community of Timmins into an industrial giant. Fogarty was chairman of the board and CEO of Texas Gulf Sulphur from October 1973 until 1981, the com pany that had already changed the fortunes of Timmins with the discov ery of a world-class orebody of zinc, copper, silver, lead and several other minerals in 1963. Timmins area gold mines had dwin dled to 13 by 1959 and there were only six left a decade later. To add salt to the wound, several of the town’s sawmills had closed, reducing the size of the region’s second major industry.

Texas Gulf literally pulled Timmins and a number of small nearby com munities out of an economic tailspin, becoming the town’s biggest employ er and largest taxpayer.

In a 1996 public address, then Tim mins Mayor Victor Power said “To those who were responsible for the investment and the exploration that led to this find we all owe a deep debt of gratitude.”

In 15 short years, the Kidd Creek Mine helped transform Texas Gulf from a one product company, sulphur, to a multinational giant with five divi sions, chemicals, metals, oil and gas, international and exploration. The cash flow from the Kidd Mine fu eled a majority of that expansion over the years.

As Fogarty said: “In 1960, sales of our one product, sulphur, were $59 million, net income was $13 million and total assets were $125 million.”

By 1972 the company’s gross revenue

ping pyrite from Timmins to Lee Creek in North Carolina and return ing phosphate rock to Timmins. A Timmins fertilizer complex would be based on North Carolina rock and sulphuric acid from the mine’s zinc and copper smelting facilities. At Lee Creek, Kidd Creek pyrite would be used to produce sulphuric acid.”

He also said, “Plans are in the for mulation stage for further expansion at Kidd Creek to eventually process about 75 per cent of the zinc concen trate production.”

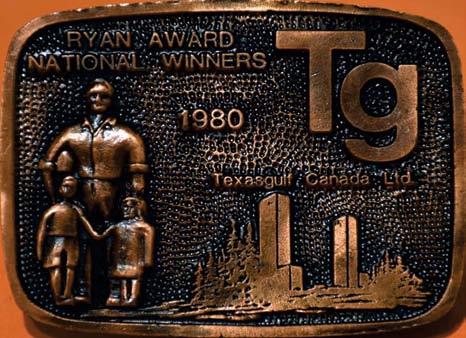

On Sept. 30, 1980, Fogarty spoke in Toronto at the A.E. Ames Metal Conference and once again he talked about vertical opportunities. The company had two gold mines on its property, Owl Creek and Hoyle Pond, and he said a precious metals refinery was planned.

“We would like to build a cement plant at Kidd Creek. Large amounts

of cement are required for un derground backfill in order to achieve 100 per cent ore recov ery,” said Fogarty.

He told the conference that en gineering work and some piledriving was then underway for the expansion of the new copper smelter and refinery to increase capacity from 65,000 to 100,000 tons per year by using more oxy gen in the smelting process.

The project would include “new oxygen and sulphuric acid plants and an expansion of the refin ery. Construction is scheduled to start in early 1982,” he said.

But it was not to be.

A small corporate jet, returning through rain and ground fog to company headquarters in Stam

ford, Conn., crashed on approach to Westchester County Airport on Feb. 11, 1981. Executives had been attending a meeting in To ronto.

Richard D. Mollison, the vice chairman of Texas Gulf, is sued a statement confirming that Charles F. Fogarty, the company’s 59-year-old chairman and chief executive officer, three of the company’s 12 vice-presidents, the chief corporate communications officer and two pilots were killed on impact.

Five months later, Elf Aquitaine, a French development corpora tion acquired ownership of Texas Gulf in a $5 billion deal.

The two gold properties were eventually sold off and Fogarty’s dreams were forgotten.

Did you know that Canada’s most iconic folk country singer wrote a song about the discovery of the Kidd Creek Mine?

Well it’s true, the now legendary Stompin’ Tom Connors was living in Timmins at the time of the nations largest staking boom created by the announcement of the discovery of a rich copper and zinc deposit in Kidd Township.

So in 1965, the 29 year old Tom Con nors sat with Murdo Martin who was Member of Parliament for Timmins,

and Gerry Quinn and the three men wrote a song about the bright future the mine would bring to Timmins, even correctly forecasting a smelter and refinery.

Local radio station CKGB knew Tom was a star in the making and recorded his second 45 rpm single. Side 1 of that vinyl record features “The Birth of the New Dragon Mine” which was the Kidd Creek Mine. When the mine’s name changed from the New Dragon Mine to Kidd Creek Mine, Tom stopped singing the song. He

eventually re-recorded it in 2008 on his album The Ballad of Stompin’ Tom and re-titled it “The Birth of the Texas Gulf Mine”

In addition to Timmins – Birth of the Texas Gulf Mine, other Stompin Tom Songs related to mining include Sudbury Saturday Night (Inco Nickel Miners), Dam Good Song for a Miner (Elliot Lake Uranium Miners), Fire in the Mine (Timmins Gold Miners, 1965 McIntyre Mine Fire), Coal Boat Song (Cape Breton Coal), Long Gone to the Yukon (Yukon Gold).

In Timmins that great northern place of renown

The Hollinger mine was about to close down Was enough to strike fear to the hearts of the bold Wondering just what their future would hold Nobody knew it was time

For the birth of the new Dragon mine

But a copter flew daily from Timmins they say To land in Kidd township just 12 miles away Still no one paid heed as they walked down the streets Engrossed with the problems they’d soon have to meet Then just a few heard it was time

For the birth of the new Dragon mine

There was a mere handful who found out the score

The Texas Gulf Sulfur had struck some good ore

Together they staked every claim to be found Is said some made millions for holding good ground Guess somebody knew it was time

For the birth of the new Dragon mine

At last word leaked out of this rich copper find And the people of Timmins went out of their mind

A well beaten path to the stock brokers door Was trodden by thousands never seen there before

Now everyone knew it was time

For the birth of the new Dragon mine

From Reid to Carscallen and eastward to Teck The bush filled with stakers who daily would trek And the moose had to hide themselves most of the day

While claims stakers rushed in to make the bush pay All the papers proclaimed it was time

For the birth of the new Dragon mine

To Timmins came people from south east and west

From thousands of miles they all came to invest

Some mortgaged their homes just to try out their luck

A few struck it rich while the others got stuck But the hopes of the north made a climb

At the birth of the new Dragon mine

So nobody’s worried the future looks bright

For a smelter in Timmins we’ve all joined the fight

A smelter with lots of rich ore to refine Will start a new life for the old Porcupine

And the eyes of the world are in line Well fixed on the new Dragon mine

They’re all watching this new Dragon mine

Ask anyone connected with the Kidd discovery if luck was involved and you’ll likely get the same answerluck had very little to do with it. The more poignant response would be - it was hard work, it took huge sums of money and a new explora tion theory arrived at separately by four groups of geologists along with several individuals who collectively pursued that theory with an unwaver ing determination. The discovery would not have been possible without Texas Gulf Sulphur Company Limited accepting and ulti mately agreeing to act on the theory. How it all happened was diarized by chief mine geologist Brian W. Hester. He was hired by Texas Gulf on May 1st, 1964 to replace geologist Ken Darke who was leaving. Darke was the man who spotted the famous Kidd 55-1 diamond drill hole that pierced the massive orebody. What follows is an abridged version of events as recalled by Hester, with additions from other documents.

‘replacement.’ At the time, little inter est was shown in volcanic processes. Geology of the Precambrian structure in the Canadian Shield was widely considered to be too complicated and poorly exposed to allow interpretation in anything more than general terms. Work in Japan and Norway led to ge ologists to debate a new theory, that massive sulphides were related to vol canogenic processes (VMS). Corporations that employed geolo gists working on this new interpreta tion of VMS deposits included Fal conbridge, Texas Gulf, Anaconda, and Consolidated Zinc Corporation. Hester worked for each company except Anaconda. His experience al lowed him the opportunity to develop a broad network of contacts. The four corporations regarded their in-house interpretations as confiden tial - but in the field, ideas were often

and routinely exchanged informally. Some geologists argued that drilling records showed that sulphides seemed

Geologists are notorious for jumping from one project to another. After all, they have to go where there’s workand where there is mining work to be done - alcohol and professional banter is sure to follow.

In 1950, Canadian Walter Holyk joined Texas Gulf Sulphur as a ge ologist and was given the mandate to locate pyrite deposits from which sulphur could be produced. He per suaded company management that it would be more beneficial to try to lo cate base metal sulphides than pyrite bodies and with that theory in mind, he initiated exploration in Eastern Canada. Called the Shield Project, the hunt concentrated on the Precambrian Shield.

It was the early development days of electromagnetic (EM) geophysical methods - which had yet to be adapted

posit.

Holyk -Texas GulfRichard Mollison, the Texas Gulf vice president and manager of exploration, quickly arrived and met with Holyk who introduced him to Cheriton. Mollison met with both geologists and they eagerly filled him in about their updated VMS theory. Holyk and Mollison reasoned they now had a powerful exploration model with a more general application. Why not try it out on the Canadian Shield? Texas Gulf had recently hired another geologist, Leo Miller. Holyk briefed him on the plan. Miller was told to make a compilation of Canadian Shield geology. His task was to catalog the areas not underlain by granite between Chibougamou, Quebec in the northeast and Kenora, Ontario in the southwest. With a back ground in uranium, Miller was sent on a tour of base metal mines. It was the winter of 1956-57 so field work was not possible.

to aircraft. TGS’s head geophysicist, Van Donohoo, designed a system that could be used on a helicopter. Working in the old copper district in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, Holyk ran into a former classmate from the University of British Co lumbia, Cam Cheriton. While em ployed by separate companies, the pair shared their ideas and developed a rough concept of VMS. In 1953, a deposit of massive base metal sulphides was discovered using helicopter-assisted e-m near Bathurst, New Brunswick. Holyk and Cheriton raced to the site as soon as they heard about it.

Working independently, they applied their new theory and on the first day, Cheriton found the Caribou deposit for Anaconda and on the second day Holyk found the Half Mile Lake de

As a result of Miller’s research, he recommended three areas for further work - an area near Gowganda, one near Kenora, and another that would become the Kidd Creek Mine site north of Timmins.

The effectiveness of the TGS helicop ter-borne EM system had been proven in New Brunswick, so the unit was moved to Timmins.

Holyk recruited a team of researchers tasked with combing through gov ernment records to pinpoint areas in which he believed massive sulphide orebodies would occur. The geologi cal targets were then surveyed using the Texas Gulf airborne system. Flights were made over the three se lected sites but only the Timmins one responded well to the new equipment. Flying in the Timmins area eventually resulted in about 2,000 anomalies. The

one in Kidd Township was the darling of the day’s geologists - but the area’s land ownership issues forced it low on the priority list.

Work continued throughout the 1950s, and 69 anomalies were drill-tested in the Timmins area alone, with little success.

A slump in the price of sulphur forced TGS to send its exploration crews to Calgary to hunt for oil and gas. There was no money for mineral exploration.

The company’s financial picture im proved and money was found to re sume work in the Timmins area.

For years, Holyk, Mollison and even tually Darke pushed to drill that strong anomaly in Kidd Township.

A number of critics and observers sug gest the discovery of the Kidd Creek deposit was the result of the Canadian Shield program initiated by Holyk for Texas Gulf in 1958.

TGS on the other hand, always took the position that it was a team effort, supported by multi-million dollar budgets and the faith that top officials had in their field personnel. Only the persistence of Texas Gulf staff enabled the company to acquire permission to drill their favoured tar get on Nov.8, 1963, the strong anom aly which, for years had been so dif ficult to option from several owners. In technical terms, drilling revealed that Kidd Creek, a 100 million ton volcanic massive sulphide (VMS) deposit, occurred at a domed rhyolite sediment contact.

In the end, it was the contribution of a great many geologists and an adven turous yet focused corporate board of directors, who had pieced together a working hypothesis that led to the discovery one of the world’s greatest zinc, copper, lead, and silver mines.

66 holes of the Timmins project had

In 1963 when Texas Gulf had cash flow, Darke wrote a memo urging the company to resume its search in the

Mollison, who later became president of the company, flew to Toronto from his Timmins office and got the money

Darke ordered Hole K55-l drilled on

The core that was drawn from that hole on Nov. 9 changed the histories of Timmins, the company, and the

There was much more to the story than just two stubborn and determined

First, Darke was lucky to be alive. Originally from British Columbia, he graduated from the University of BC in 1956 with a degree in geological

In an unusual move, Timmins city council welcomed an “old friend” back to the community on Sept. 12, 1983. Council paid official recogni tion to Mollison for his contribution to the quality of life in Timmins. Mollison was returning after being appointed as chairman of the board of Kidd Creek Mines Limited.

mine - but two men deserve special recognition - mining engineer Richard (Dick) Mollison and geologist Ken neth (Ken) Darke.

It was Darke’s unwavering belief in the potential of the Timmins area to host base metals that allowed him to be the right man, at the right time, in the right place back in 1963.

It was Mollison as vice-president and manager of exploration who had faith in Darke and fought the corporate battle to get the exploration budget restored after the company wanted to give up.

Darke spotted the drill that penetrated the massive copper-zinc-lead-silver deposit in Kidd Township, just 16 miles north of the then Town of Tim mins.

He was a field geologist for Texas Gulf Sulphur Co. when the explora tion budget was exhausted in 1962 and field work was cut back. The first

He went to work for Texas Gulf and in May of 1958 he was sent on a flight over Baffin Island. The plane crashed. Darke’s back was broken and his jaw severely damaged.

Despite two dislocated ankles, ge ologist George Podolsky dragged Darke and two others to safety from the burning plane. The four lay in a snowbank for 87 hours before being rescued.

While recuperating at his home in Trail, B.C. Darke prepared a paper on “type situations” where mineral de posits might be found in the Canadian Shield.

Five years later, K55-1 proved to be the ultimate “type situation”.

Born in Minnesota in 1916, Mollison was a brilliant man who won many awards during his educational period and in his professional life, but it was his personality that earned him friend ships and respect.

Mollison met with council and then with local business leaders, many of whom he had met during a relation ship stretching back two decades when he was with Texas Gulf.

Timmins Mayor Victor Power told other council members that Molli son was “fondly remembered for the many gifts the company bestowed upon the community over the years.” Mayor Power told a VIP reception that “I’m confident under the lead of the chairman of the board of directors that Kidd Creek will continue to in vest in Timmins and take an interest in the community as a good corporate citizen.”

Mollison worked out of Timmins for several years before moving up the Texas Gulf corporate ladder to the po sition of president and director 197379 and then chairman and CEO 198182 after the death of chairman Charles Fogarty.

He visited the mine nearly every month and always kept Timmins council aware of company activities and plans.

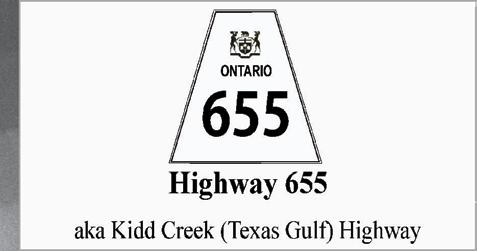

Today Highway 655 is the vital link that interconnects commerce and healthcare in the Cochrane Territorial District of Northern Ontario with over 1,150 vehicles using it per day.

This secondary highway begins at the intersection of Highway 101 and Algonquin Boulevard, near the iconic Hollinger Mine office building in Timmins and stretches 75 kilometres north, generally paralleling a high-volt age transmission line to intersect Highway 11 between the communities of Cochrane and Smooth Rock Falls. It has the distinction of being Ontario’s only secondary highway that features a 90 km/h (55 mph) speed limit due to its importance and high design standards.

This highway we take for granted today, was not always there. The highway’s beginning is a result of the Texas Gulf Sulphur Company building a permanent paved access highway to their Kidd Creek Mine property located 21 kilometres north of Timmins.

Major highway construction by Miller Paving began in June 1965, which allowed pre-production ore to be trucked and milled at Kam-Kotia and Broulan Reef Mines. This pilot plant test work helped figure out the right metallurgical settings to use in the Hoyle Concentrator. The highway to the mine was fully paved by October 1966.

Prior to the Texas Gulf Highway, access into Kidd Township for exploration was primarily by helicopter, Bom bardier bush buggy, or by foot for those who dared to trek through the woods. For many years prior to the dis

covery at Kidd Creek access into those flat swampy lands north of Timmins was from seasonal logging roads and gravel roads originating off the Ice Chest Lake Road near Connaught and Frederickhouse Lake. One could also elect to travel by water craft on the back waters of the Mattagami River created by the Lower Sturgeon Generating station built in 1923.

Highway 655 follows a long esker formation, which actually for much of the length is the watershed dividing line for the Mattagami River to the west, and the Porcupine River system to the east. As a result there are no major creek or river crossings.

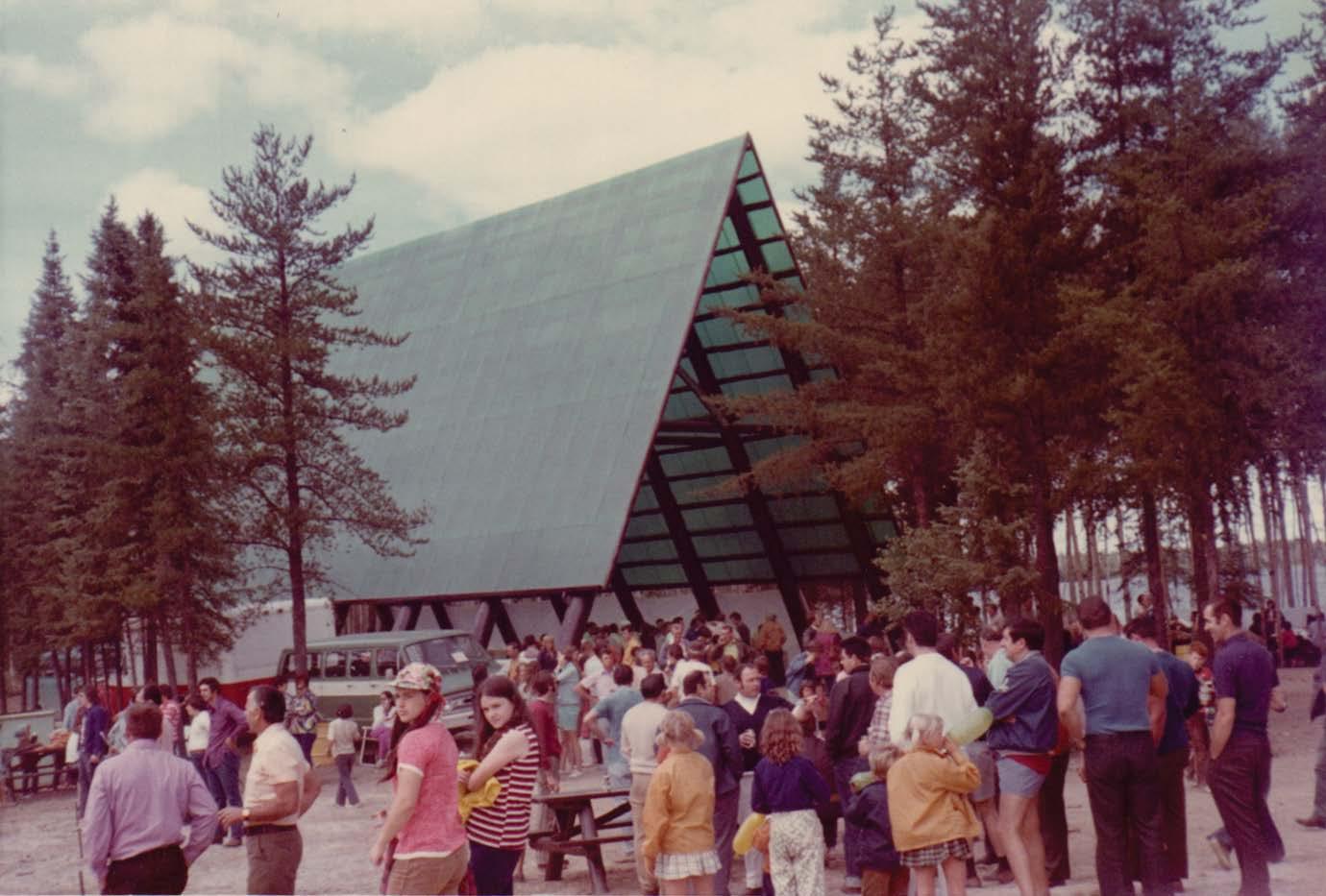

The highway skirts Bigwater Lake where a campground was developed by Texas Gulf for its employees that hosted many summer family picnics.

The route also passes Noted Lake and Feldman Lake, the later serves as the main water supply source for the Kidd Mine and replaced an original 8-inch well system as the operation moved underground.

In 1978, the Ontario Ministry of Transportation completed the extension of the Kidd Creek (Texas Gulf) Highway northwards to Highway 11. With the advent of 911 call services, the mine site address became 11335 Highway 655 North.

No highway construction was required to access the Concentrator in Hoyle because Highway 101 east was pre-existing. Significant work though was required in 1966 within the right of way of Highway 101 for 6 ki lometres to install a 30 inch water pipeline from the Frederickhouse River.

To think of 50 years’ worth of boot prints across both the Kidd mine and concentrator sites is almost unimaginable considering that Kidd has employed more than 20,000 peo ple since 1966. And many of those boot prints have been made by generations of the same families.

When you think of “the family business,” you probably think of a store or an auto dealership. Anything but a mine. However, some of Kidd’s employees working for the opera tions today are following in the boot steps of their fathers and grandfathers. The Spehars are an example of a multigenerational “family business” in mining.

Nearly three kilometres underground, two brothers, Ivo and Mikka Spehar, take turns installing steel bolts into the fresh ly exposed rock walls.

“We’re the first ones in, breaking new ground to extend the mine,” says Ivo. They call it ground support, and 9600 feet above them, their father, Miro Spehar, is part of a team that develops the intricate operational plans that determine, in part, where his two sons will be working on any given day. Miro’s job as a designer is part of yet another operational plan of sorts, keeping the Spehar name attached to Kidd Op erations’ mining legacy.

Miro’s father Ed Spehar was here when Kidd Creek first started in the early 1960’s. He came to Canada as a political refugee and eventually settled in Timmins where he went to work for Kidd as the chief draftsman. Ed was part of the team that developed the early mine models and simultaneously, thanks to his love of photography, became Kidd’s de facto historian.

Ed’s grandson, Ivo started at Kidd Creek as a summer student in 2011. After getting his common core training, he landed a full-time job with Kidd. He and his brother Mikka are not only on the same shift, they are on the same crew. Mikka started at Kidd in 2010 as a “nipper”, the nickname used to describe what amounts to a miner’s helper.

“When the crews needed stuff done, it was our job to go and fetch what was needed,” he says. “You have to start some where and now my brother and I are part of the deep de velopment team. I guess you could say we started from the bottom up.”

Mika and Ivo’s maternal grandfather Matti Kangas also worked as a “shaft man” at Kidd for many years.

Some of the three-generation families that have worked at Kidd include the Rivas, Del Bels, Toners, and Laurins.

Prospectors, geologists, and mine-seekers may not all be spiri tual men and women - but when it comes to mining communities like Timmins, there is little doubt that many prayers were answered when news of the Kidd discovery was shared with the world back in 1964.

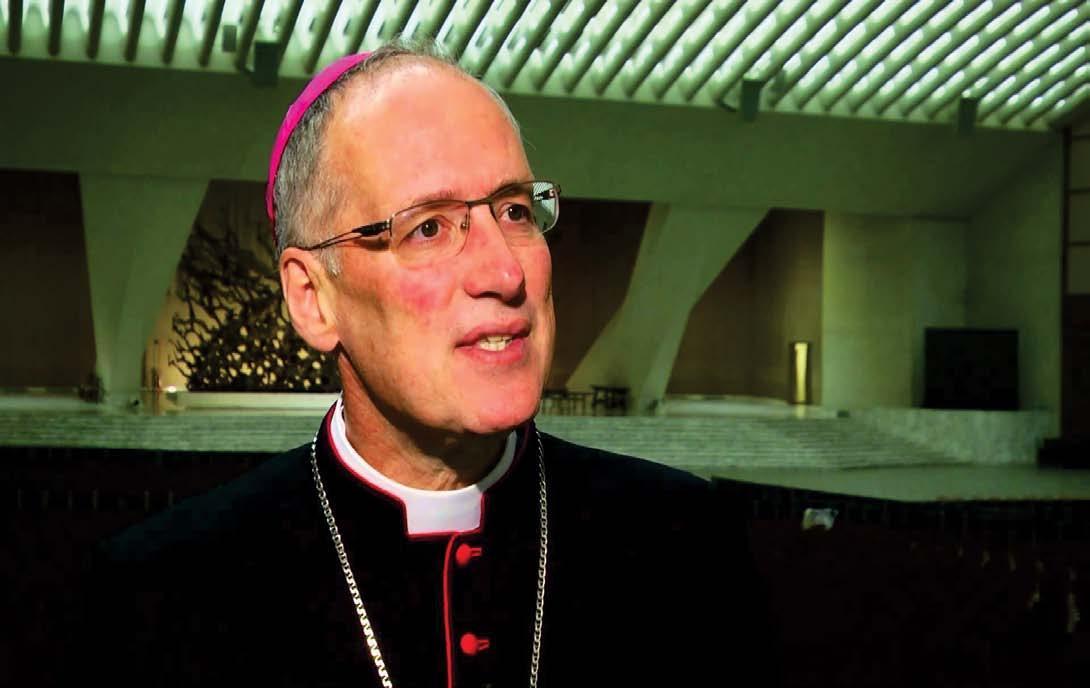

Attendees to a global conference on mining practices in Ottawa on Nov.7, 2014 heard praise about one company in particular. Canadian Conference of Catho lic Bishops president Paul-André Durocher spoke of growing up in the mining town of Timmins, On tario.

The Gatineau, Quebec Archbish op was 10 years old when the town’s largest gold mine, the Hol linger, announced it would close

because it had run out of gold. The mine closure created a “huge economic blow,” said Durocher. Many families found themselves without a source of income and there were genuine fears Timmins would become a ghost town. Not long afterwards, a major dis covery led to the opening of a new mine, Kidd Creek, in the mid1960s.

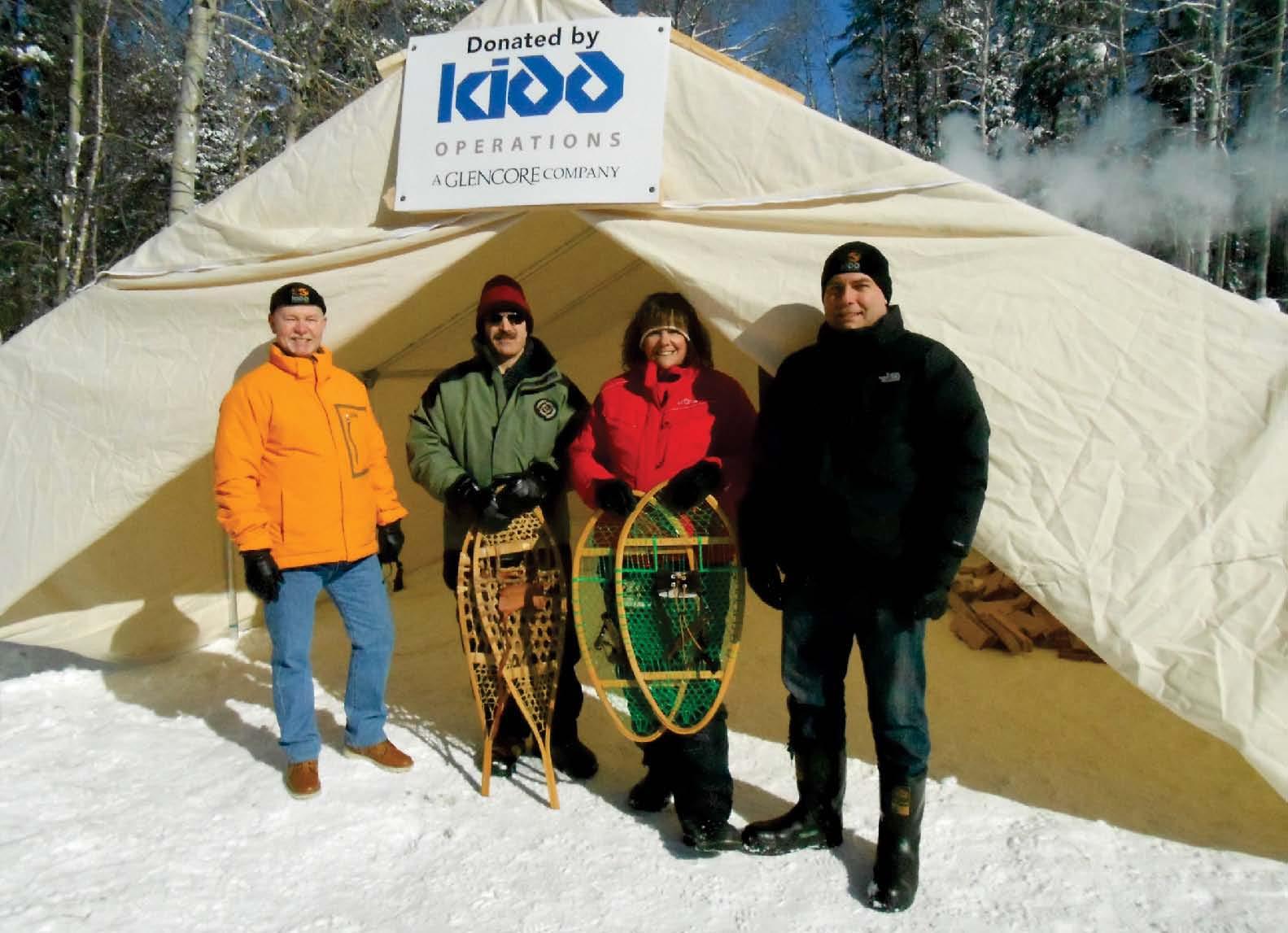

Prayers had been answered. Owner Texas Gulf arrived with the intent of contributing to the overall good of the community, the arch bishop said. Durocher told the con ference how Kidd offered the best salaries; it promised to lay off no one during the course of the min ing operation; and it bought prop erty around a lake (known today as BigWater) to create camp sites its

employees could use. The company then built a metal lurgical facility to process the ore, “integrating the most advanced systems for the ecological treat ment of ore,” he said.

The company continued to moni tor water downwind of the site, even though no one lived there. It also kept a herd of bison - because bison are so sensitive to air pollu tion, he said.

Their presence was a sign of the quality of the air.

Durocher went on to praise the way Texas Gulf and its successive owners have spent untold millions of dollars to protect the environ ment around its mine.

Today, Glencore carries on that commitment to environmental legacy.

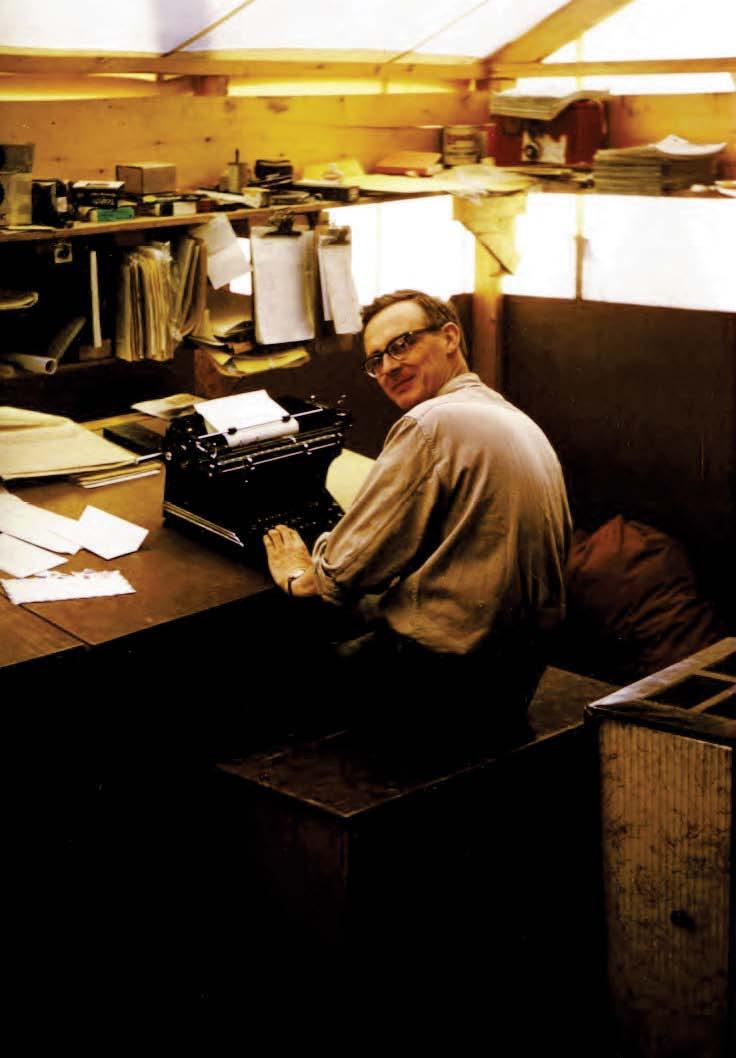

I arrived on the job on the third day of January, 1964.

The company had been doing a lot of drilling in the area, and they had struck that good hole back in Novem ber of 1963. After that, they moved off the property; because they didn’t have all the holdings yet; all the deals weren’t closed.

We started moving equipment back in to the property on Good Friday, which I believe that year was the 27th of March. We continued to move equipment in over the Easter holiday, by equipment, I’m talking drills and camp equipment.

We got into the property through the back of Dugwall, out by Hoyle. A winter road went out to the hydro line on which we could go by truck, an ice road. They were hauling pulp (cut

trees) out at the time. From there we used swamp buggies to pull the drills across country to the property, about two-and-a-half-miles.

Throughout the winter months we were staking. I had a bunch of guys staking for me, laying out the claims. And I had to spend a lot of time at the mining recorder’s office, registering the claims.

That winter, we staked about 240 claims, but scattered about the area. You must remember that the mine site was not staked land. Much of it was patented land. Much of the mine site land was in the hands of different fam ily estates, which the company had to negotiate with. This was land that was given to veterans of the Boer War back around the turn of the century. I doubt if anybody ever lived on the land. There was nothing there but bush. We

put up the tents immediately, at least to get going, I think there were four of them. We eventually ended up with 12 tents. Then we hauled in plywood and built a cook room, a totally wooden room.

A core shack came in a little bit later, about a month later, and that was ply wood too. That was where we stored the core and split it. But all the sleep ing quarters were all tents.

The drilling contractor was Canadian Longyear from North Bay. We kept the crews in the bush until the an nouncement was made.

But before that happened, one of the guys took sick, and I personally es corted him to the Bon-Air Motel, took him to see a doctor, then took him to a drug store to get a prescription, then back to the Bon-Air Motel to spend

the night, and back into work the next day.

I never let him out of my sight. That was so nobody could talk about the drilling results. We kept it that way until the 16th of April (date of the official announcement of the find by Texas Gulf).

But it wasn’t such a long period. We only moved in at the end of March on this particular property. We set up the first drill to start working on April 1, in the morning.

It was a late spring, so we didn’t get too much water. In fact, we moved in and set up even before the snow start ed to melt.

We got set up with one drill and in about a week or so we had seven drills at work. And we had seven drills go ing all spring, and all summer, right up until about November. They pro duced a lot of core, and I’d say about 90 per cent of that core produced was ore.

I was kept pretty busy that first sum mer because I had the seven drills to look after. Our geologist was only out to the site a few times after we got started and then he quit. It was a lot of activity concentrated in one small area, considering that the company had catalogued more than 2,000 anomalies in its Canadian Shield Project. Out of that, only sev en, including Kidd, were picked for more study. Aerial surveys were car

ried out over Kidd in 1958 and 1959, and I believe even in 1960.

And this was the one of seven select ed for further study that turned out to be an orebody.

My first affiliation with Texas Gulf Sulphur was back in 1954. They had contracted a geophysical survey through Newmont Explorations, and I worked as a contractor for them cut ting picket (mining claim) lines. This was in New Brunswick.

My family came up here in February of 1964. Up to the end of March I was with them, but from the end of March throughout the summer, I was lucky to get home briefly once a week.

Every Tuesday afternoon I’d take a load of split core to the airport, and stay there until it was actually loaded on the aircraft, and the aircraft had taken off. It went to the Colorado School of Mines for assay.

There were a lot of rumours going around then, actually, they had started after the first hole drilled the previ ous November. The drillers had gone away, and you couldn’t stop them from talking.

Most of the core was kept hidden from them, but the initial footage wasn’t. Some of them recognized it as good ore.

When we were drilling that summer, the geologist would log the core, turn it over to me, and I would section it off. Then my splitters would split it in two, put half of it back into the core

box, and put the other half into canvas bags.

Life was interesting in the camp. We didn’t have too good facilities, so we’d just get up and go straight for breakfast at 6:15 in the morning. We took a bath when we got out.

I would never stop working before 9 or 9:30 at night, about 14-hour days, seven days a week, for a six-month period. I was younger then, I don’t know if I’d want to work like that again.

From about the time I arrived here Jan. 3, until about a week before Christmas, I hadn’t had a day off. Never had a day I didn’t work. But a week didn’t go by that Richard Mol lison (vice-president of exploration) wasn’t up here too. And decisions were made very quickly.

Dick came in to see me one morning, we had a coffee, and then he said we were going to take the helicopter to see where we could put a road.

We flew over the area with mosa ics and plotted the road pretty much where it is now. By the end of June, Miller Paving had started building the road. By working 6 days a week from day break to dusk, Miller Paving rushed the highway’s construction to completion.

By the 10th of October of that same year, the first Texasgulf employee was me, who drove a company truck right up to the core shack.

That was how things got done.

For more than 100 years people from all walks of life have found their way to the Timmins area. Some turned around and left. The majority stayed. None more interesting than long-time Kidd employee Wayne Kidd. He told his story in 1984 and recounted how he was asked by a helicopter company to snoop around the Town of Timmins for a single day while delivering a chopper to the nearby Town of Co chrane.

A fevered mining rush was happening in and around Timmins thanks to the April 16, 1964 announcement by Tex as Gulf Sulphur Company of the huge Kidd Creek base metal find. Dozens of companies were scrambling to send men into the bushland but there were very few roads and planes and heli

copters were scarce.

I didn’t know all that much about mining, but I did know how to pilot a helicopter, and that’s how I came to Kidd Creek. I learned to fly in the air force, going in in 1955 and coming out in 1959. Then I went to Dominion Helicopters.

In April 1964, I came to Timmins on the way to deliver a helicopter to Co chrane. The machine was due there May 1 so I was ordered to stop in Tim mins on the way through to see what was going on in the mining scene. There were rumours about something big in a mining rush going on. Domin ion had a helicopter here on contract. It had arrived in November of 1963. Texas Gulf had drilled its big hole in early November, then set out to cov er its tracks. They put drills back in

Prosser Township to look like they were going back where they had been. They were actually drilling anoma lies, so they weren’t really dummy holes.

Texas Gulf originally didn’t have its own helicopter here. It had one in the Arctic and one in storage in Churchill, Man. The one in the Arctic was on Baffin Island, where Nanisivik is. I was at the Bon-Air Motel and got commandeered (hired) by a bunch of (mining claim) stakers.

Texas Gulf then brought in one heli copter, and sent a pilot to Churchill to bring back the one in storage. Then they offered me a job, about the third week in April. I started May 7.

At that time there wasn’t much at the discovery site except trees and

swamp. There was a little communi ty of tents for the drill crews and the slashers (tree cutters).

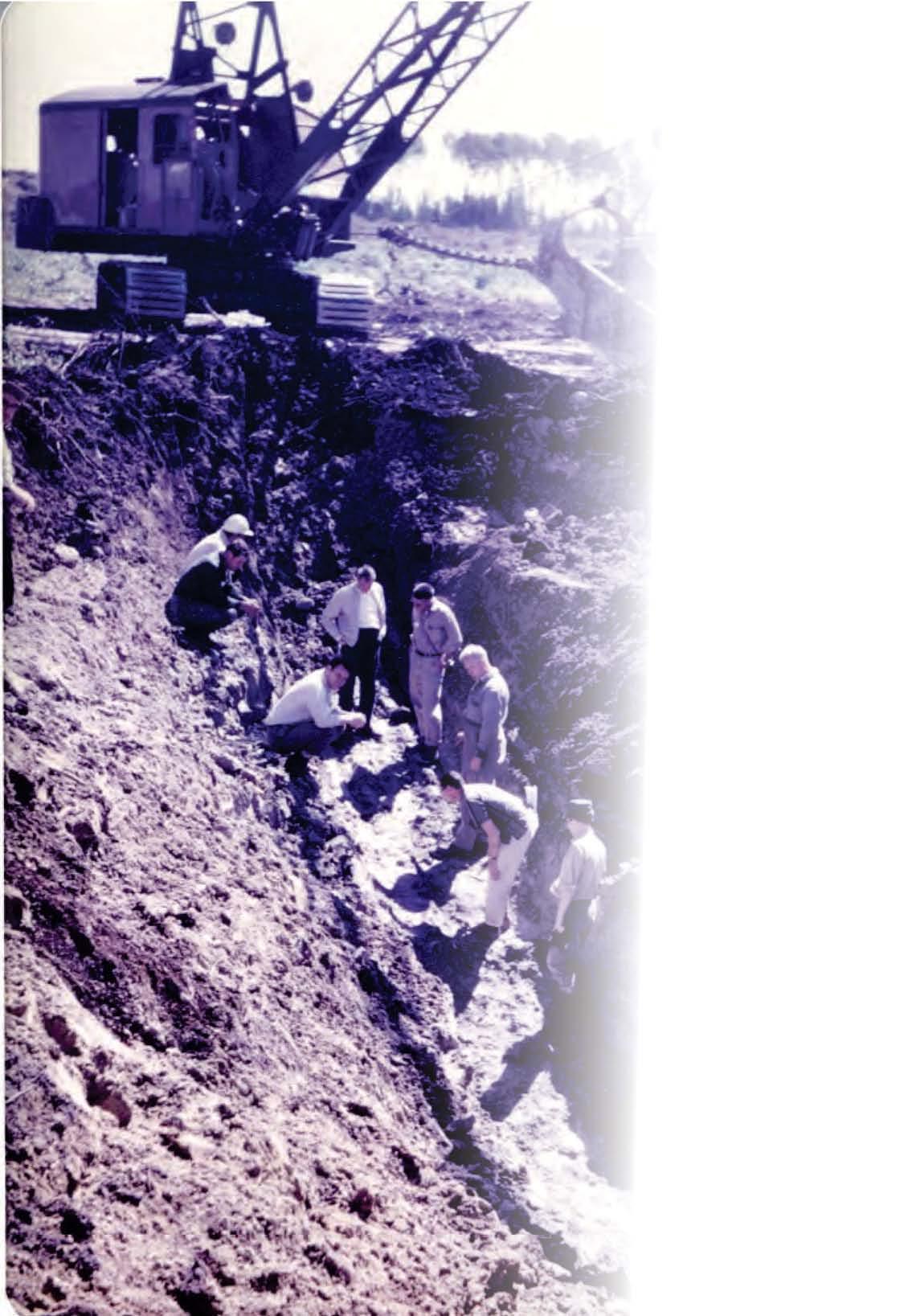

The centre of the orebody domed and came to within 12 feet of surface, so a dragline was brought in one day be cause Dick Mollison (vice-president and manager of exploration) wanted to have a look at the orebody. All we had seen was (drill) core. The dragline cleaned off just the dome. Some holes were put in and they blew off the top of the dome.

On September 18, 1964 Mollison walked the trench and then told me to fly into town and buy two cases of #1 Mumm’s champagne. Then the others were allowed into the trench.

By the first of June I was on my way to Nanisivik to bring the other heli

copter back.

I was supposed to fly right back into Timmins, but the helicopter wasn’t in very good shape. It had been sitting there all winter. It had a canvas han gar on it, but it had blown off.

I talked to my boss in New York and he said since I was there to do what I thought best. I had it taken apart and shipped to Montreal and had it back together in two days and on its way to Timmins.

I was up in the Arctic until July and when I got back they had started to survey the road, and it was probably into the property by September. They built it awfully fast.

Before the road was built, everything went in through the muskeg from the power line, all the food and that. I

used to fly in some of the people in volved, such as geologist Hugh Clay ton and the surveyors.

I’d service the drills and fly in and out seven days a week. I think I went for something like two months without a day off.

Then I had a day off and went for an other two months.

We built the hangar behind the BonAir that Fall and did all the flying out of there until 1971. Finally, we had to move to the airport.

I moved to Timmins in the summer of 1964. I had been living in Bramp ton, but the company said I had a per manent job, based in Timmins. Been here ever since.

I had come up here for one day, and never left.

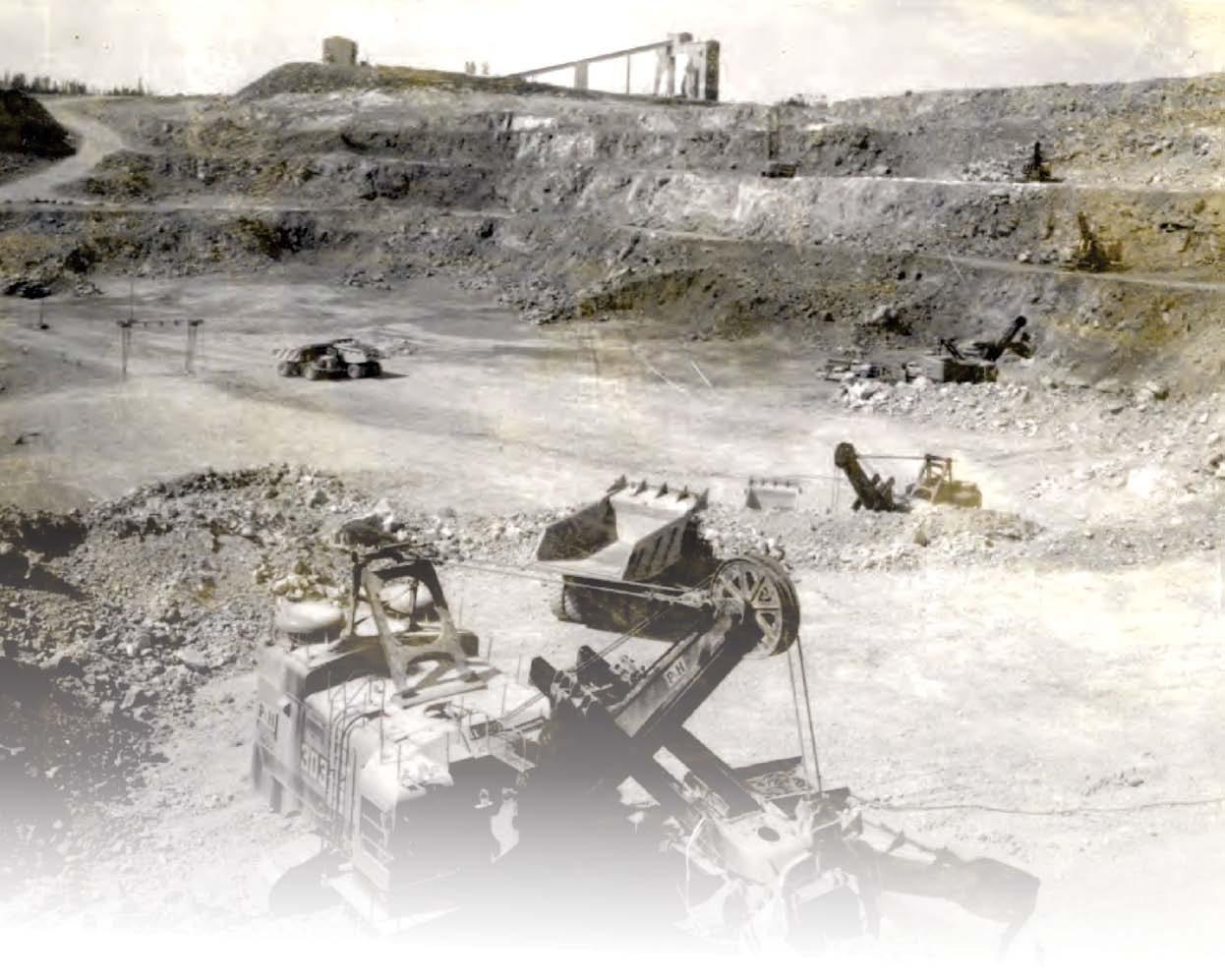

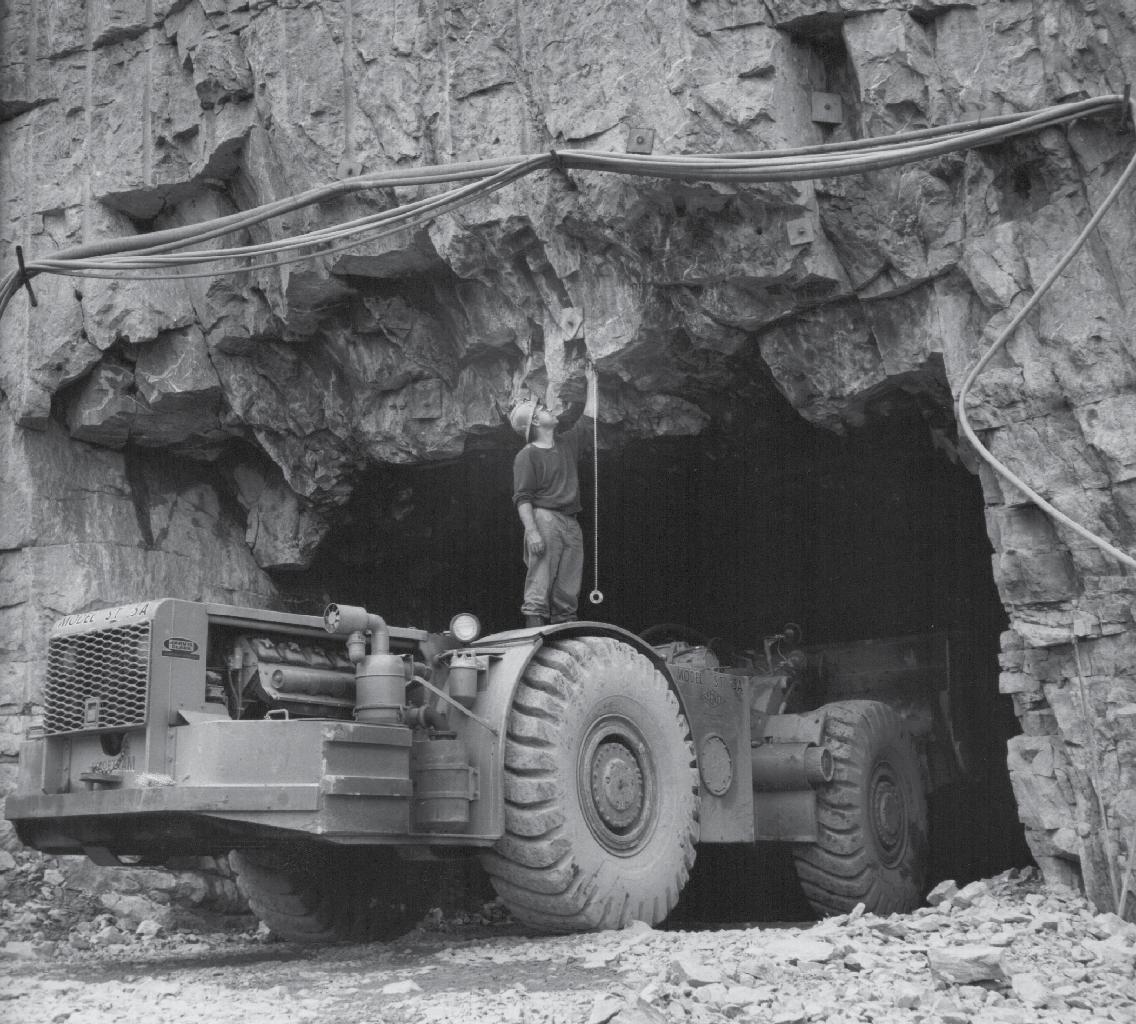

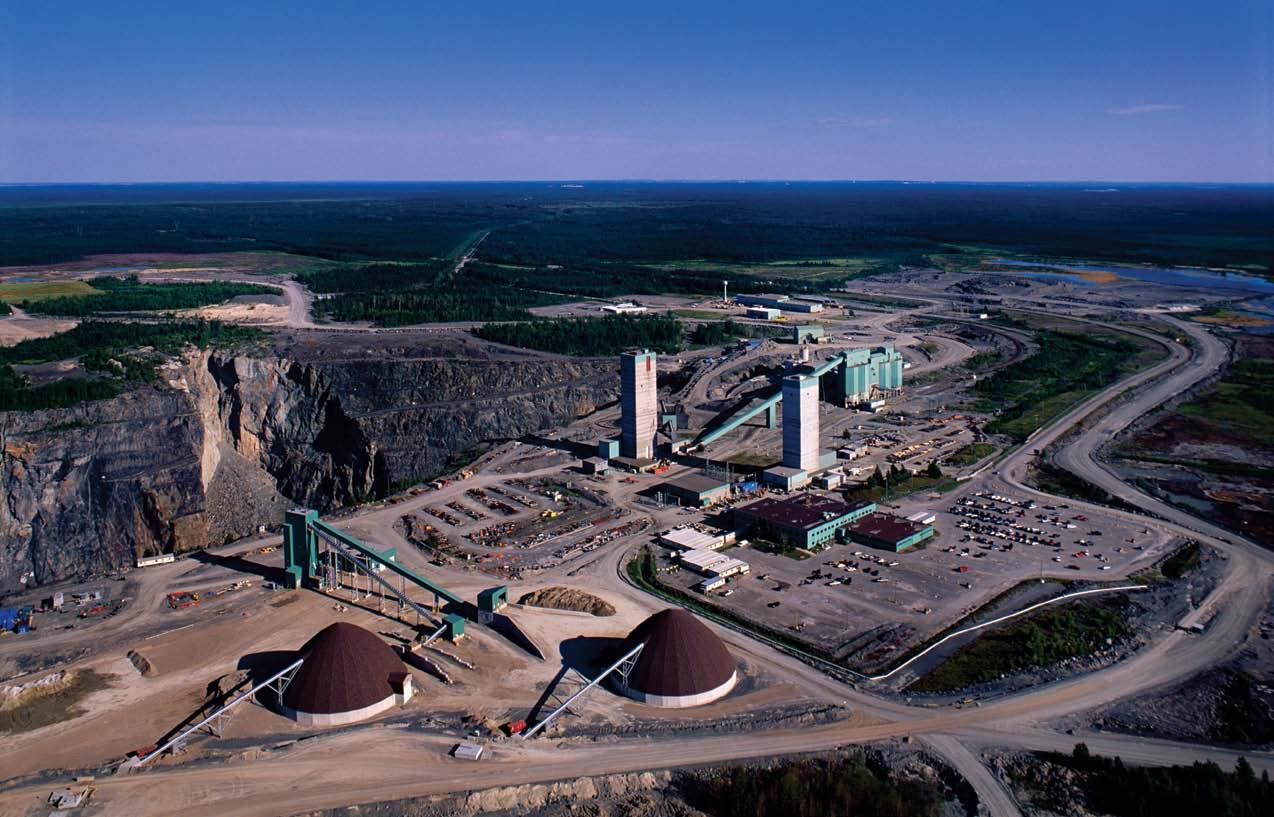

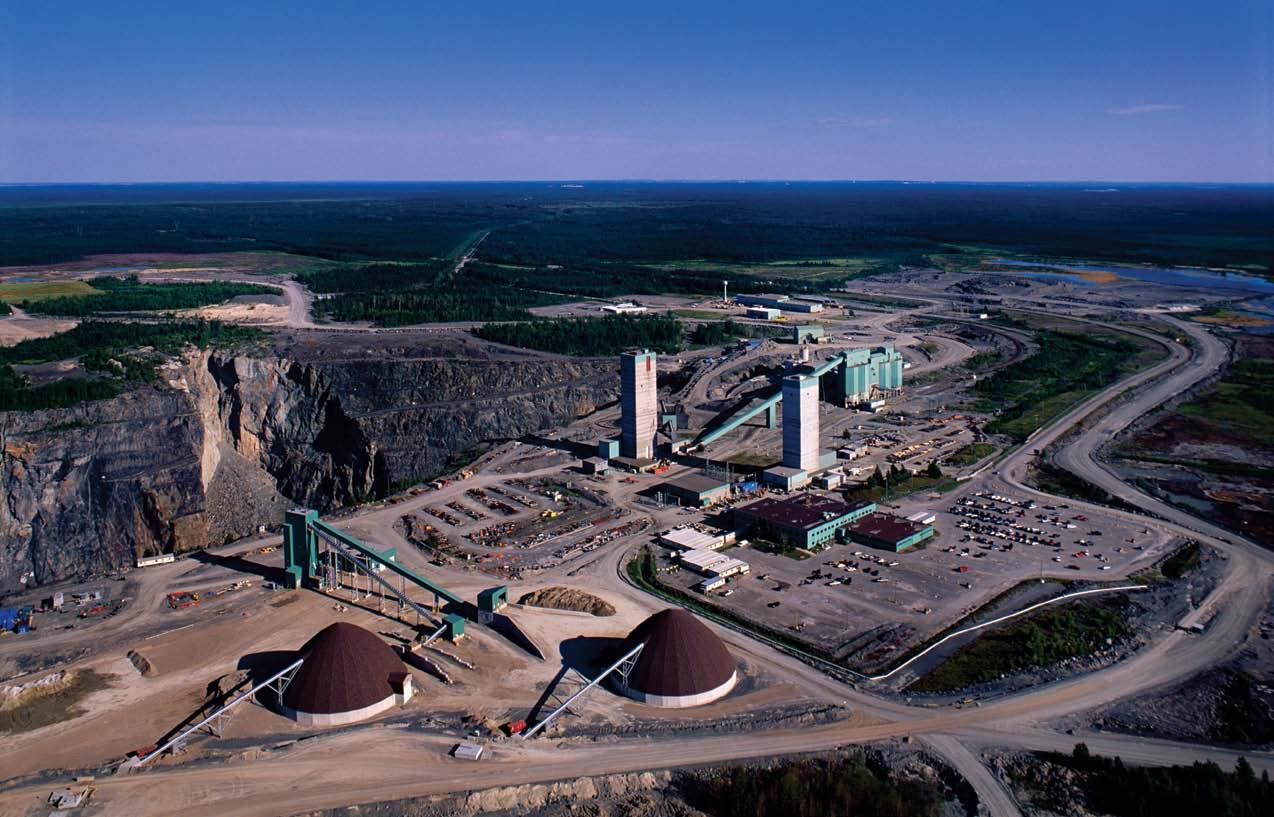

highly-skilled workforce to run a mine, but it also takes some type of safe and technically-sound hole in the ground, whether that is an open pit or a mine shaft. At Kidd Creek, you will find both those types: pit and shafts.

“Kidd Creek was twice blessed when the gigantic orebody was discovered in 1963,” said Keith Youngblut, a former mine manager for the Kidd Creek One, Two and Three Mines. “For one thing, the ore was close to the surface and for another, since the orebody was virtually vertical, mining could begin right at the sur face. Open pit mining, of course, is infinitely less expensive than un derground mining. That’s why most mine developers hope against hope that there will be an open pit mine developed, at least for the first few years.

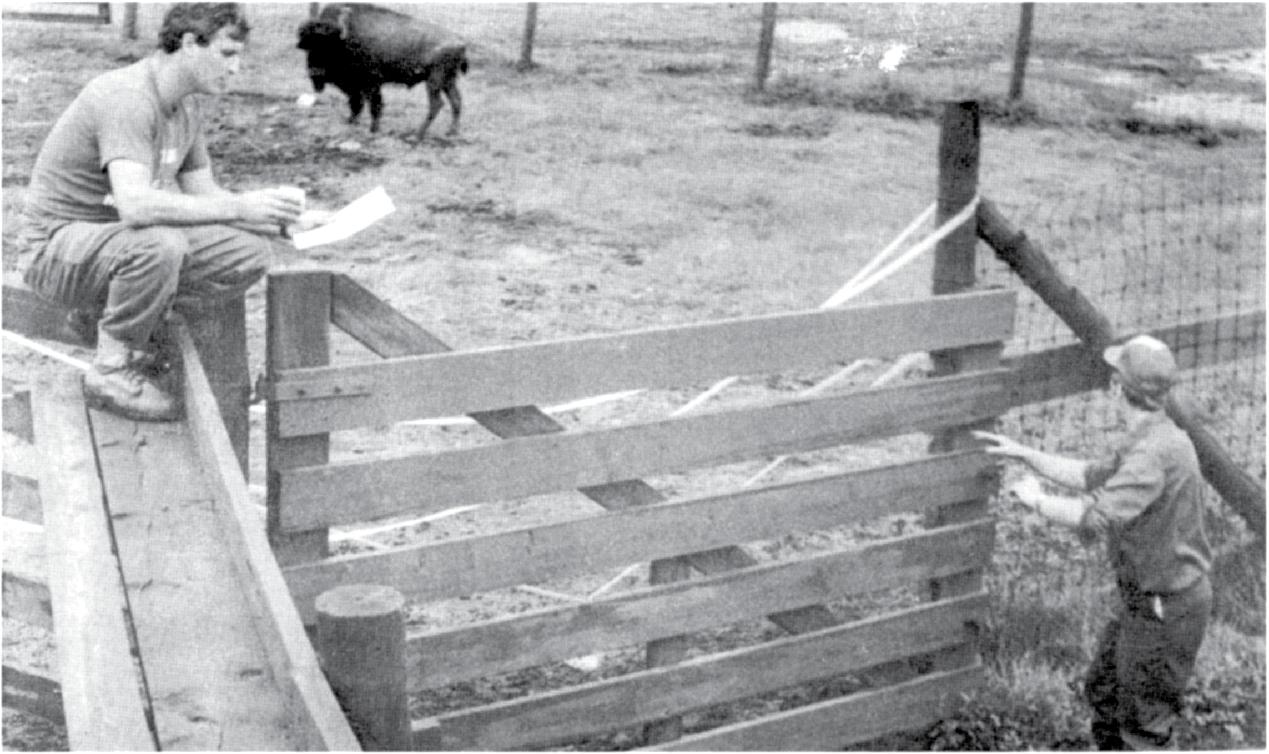

Because the pit area was covered with muskeg and dense spruce forest with no rock outcrops, the first task was to clear the trees and excavate

The 1.5 to 1.8 metres of muskeg at the surface was underlain by considerable depths of brown boulder clay, varved clays and silty material at the rock sur face. Overburden depths ranged from 3.6 metres at the center of the pit area to 27.4 metres at the north and south rims of the pit. Finished clay banks were to have a 5:1 slope, with a 3:1 back slope on the 12.2 metre berms, giving an over-all slope of 10:1, which would be was a major undertaking due to the large volume, the instability of the material and the containment of the stripped material to prevent environ mental damage to surrounding streams. First the muskeg was removed down to the clay around the perimeter of the proposed stripping area. A water-tight dike of rock and clay was constructed in this trench and the stripping area was drained.

A fleet of fifty-five large motor scrap ers, twelve bulldozers, three draglines and ten 35-ton trucks were used. Strip ping took place mainly in the winter when the frozen clay could be ripped,

more economically by scrapers. The draglines were used during the summer by building rock roads over the soft clay. Final clean-up in the hollows of the rock surface was com pleted with the draglines and a 6-cu. yd rubber-tired loader.

Then the surface of the ore was washed, removing all traces of clay to minimize problems in the concen trator. A total of 8.5 million yards of overburden was removed during the five winters of stripping.

The finished clay areas were seeded with a mixture of timothy and rye grasses and crown vetch for stability and the prevention of erosion.

“We started mining the open pit in the fall of 1966,” said Youngblut. “The first copper-zinc circuit in the concen trator started in November, 1966, and two more circuits were added in early 1967.”

Little by little, a gaping hole was be ing dug into the earth - and the hole would keep getting bigger and deeper

“We stopped open pit mining in the spring of 1977,” said Youngblut. “By that time, we had already removed more than 30 million tonnes of ore from the pit. Added to that, we ex tracted 69.8 million tonnes of waste.”

When the decision was made to de velop an underground mine, access was made by drifting from the second bench of the open pit to where the No. One Mine shaft was to be collared. The pit, upon its closure, ended up be ing 792.6 metres long by 400 metres wide and over 200 metres deep.

Cont’d from pg. 36 as time went on.

In the end, the pit went down over 200

metres. There were 18 benches, each about 10 metres higher than the one below it.

On the technical side, Kidd had to fig ure out how to mine the two orebod ies discovered – the North and South orebodies, as well as how to blend the different ores prior to sending them to the concentrator. The two orebodies had a combined length of 670.6 me tres and a maximum width of 192.9 metres. They strike almost due north, dip about 85 degrees east and rake to

Cont’d from pg. 38

the north.

Mining plans were based on comput erized analysis of the drill core spac ing and the location of the mineraliza tion data.

The ores at Kidd Creek are massive, stringer and disseminated sulphides varying widely in metal content and distribution.

The South Orebody, which contained sphalerite, chalcopyrite and a minor amount of silver, provides most of the higher-grade zinc and some highgrade copper for the copper-zinc ‘A’ ore milling circuits. The North Ore body had both ‘A’ type ore and the lead-zinc-silver ore which provides feed for the ‘C” milling circuit.

On the hanging-wall side, a cherty breccia containing chalcopyrite and minor amounts of sphalerite is mined as ‘A’ ore and a massive to semimassive sulphide material containing galena, pyrite, sphalerite and silver is mined as ‘C’ ore.

The two distinct ore types are handled and treated separately throughout the entire operation. In addition, each ore type is blended within itself to provide ore feeds for the concentrator with rea sonably consistent grades and mineral characteristics.

The preliminary evaluation of the two orebodies was computerized for tonnages and grades on a 6.1 by 6.1 metre grid. The evaluation was based on drill-core intersections over 12.2 metre vertical projections coinciding with the proposed bench intervals, taking the deviations of the drill holes into account. The computer print-outs gave an ore distribution and evaluation bench-by-bench and indicated the areas of varying mineralization.

For every truckload of ore, two-andhalf to four truckloads of waste rock needed to be removed.

The pit was tear-drop shaped, with the narrow end to the south, and at the surface was 792.5 metres long by 400

metres wide. Ramps were 30.5 me

tres wide, with a 10% grade.

The south ramp was left-handed, started at the southeast and contin ued to the bottom of the pit. A second ramp on the west and north walls ran from surface to join the south ramp at No.7 bench. The surface crusher was in close proximity to the south ramp minimizing the hauling distance to the crusher. This ramp handled the total pit pro

duction when part of the south ramp, from No. 4 bench to surface, was lost due to the underground operation. Over-all wall slopes were 53 degrees, and were laid out to avoid prominent protuberances which could relax and become unstable and potentially dan gerous.

In the years 1969 and 1970, with a peak waste rock stripping ratio of four waste to one ore, the relatively small

Cont’d on pg. 40

complicated by the forced mining of certain ore types to maintain orderly pit development.

By operating the pit 21 shifts per week and doublehandling some ore on and off stockpiles, the tight period was traversed very successfully. During 1972, the situation re versed itself as the waste-ore ra tio dropped dra matically and massive stock piles were built outside of the pit, resulting in a much simpler situation with regard to grade control and a re turn to a 15-shift work week. The open pit was relatively dry, even though it was located in a muskeg area.

This was probably because the rock surface was sealed by the overlying clays, giving the surface waters little chance to penetrate to bedrock. The normal inflow of water was about 325 gallons per minute, however, during the spring thaw or at times of heavy rainfall several million gallons of water may enter the pit.

A series of pumps with a capacity of 3,000 gallons per minute were used to lift water out of the pit.

A unique feature was the location of de-watering pumps and electrical substations in underground excavations in the walls of the pit. All pumps were controlled automati cally by float or probe switches. Even though pit ceased operation in 1977, it still plays an important role in Kidd’s underground mining pro duction. Through the pit, Kidd draws some fresh air for ventilation as well as for maintaining the ice stopes that help cool the deeper levels in the sum mer. An automated system monitors any movement of the pit walls. Upon closure, plans are to allow the pit to naturally fill with water. In the interest of public safety, a several-metre high boulder fence will be erected around the entire perimeter of the open pit.

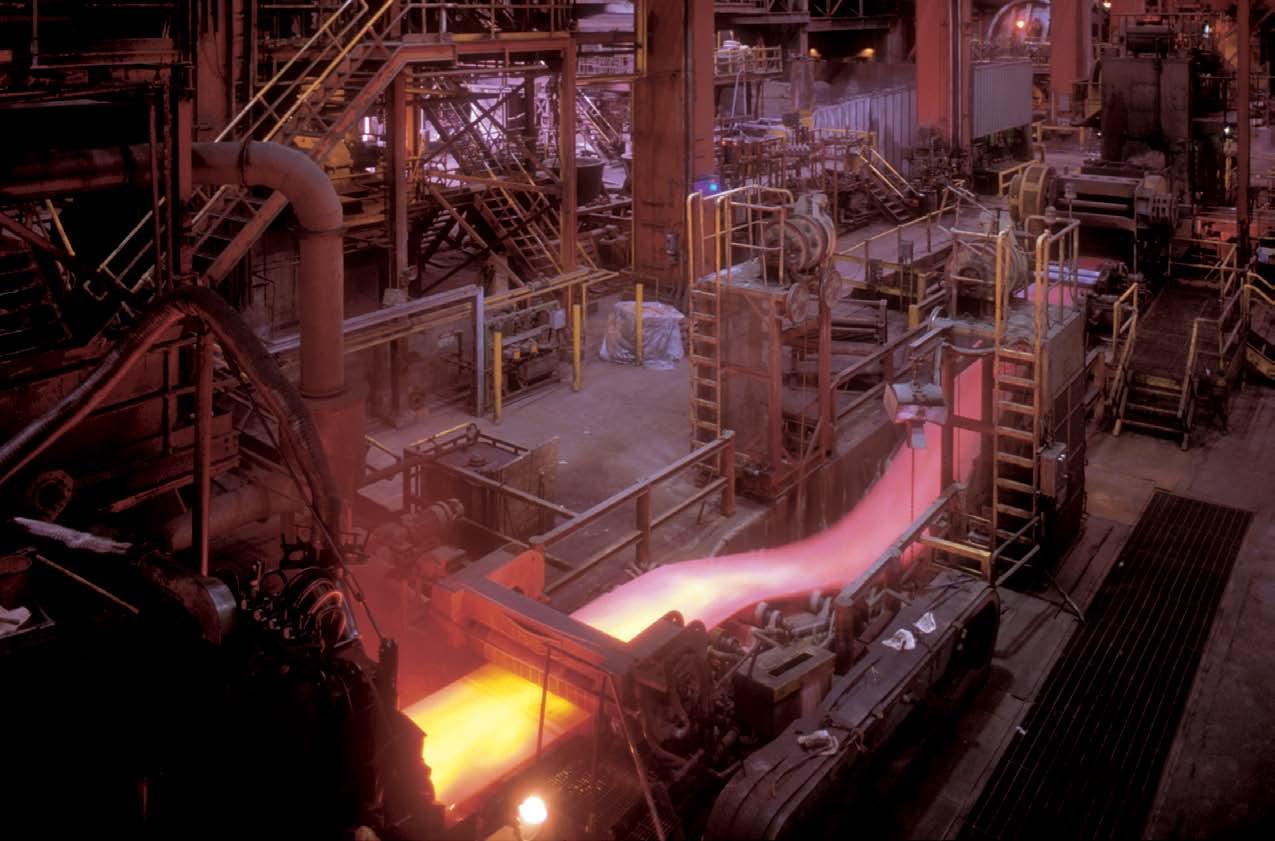

An orebody as large and complex as Kidd Creek presented developers, engineers and the mine’s ownership team with a unique set of challenges. The realization that the Kidd Creek orebody was actually two deposits with different values forced the com pany to undertake extensive testing before decisions were made regarding a concentrator.

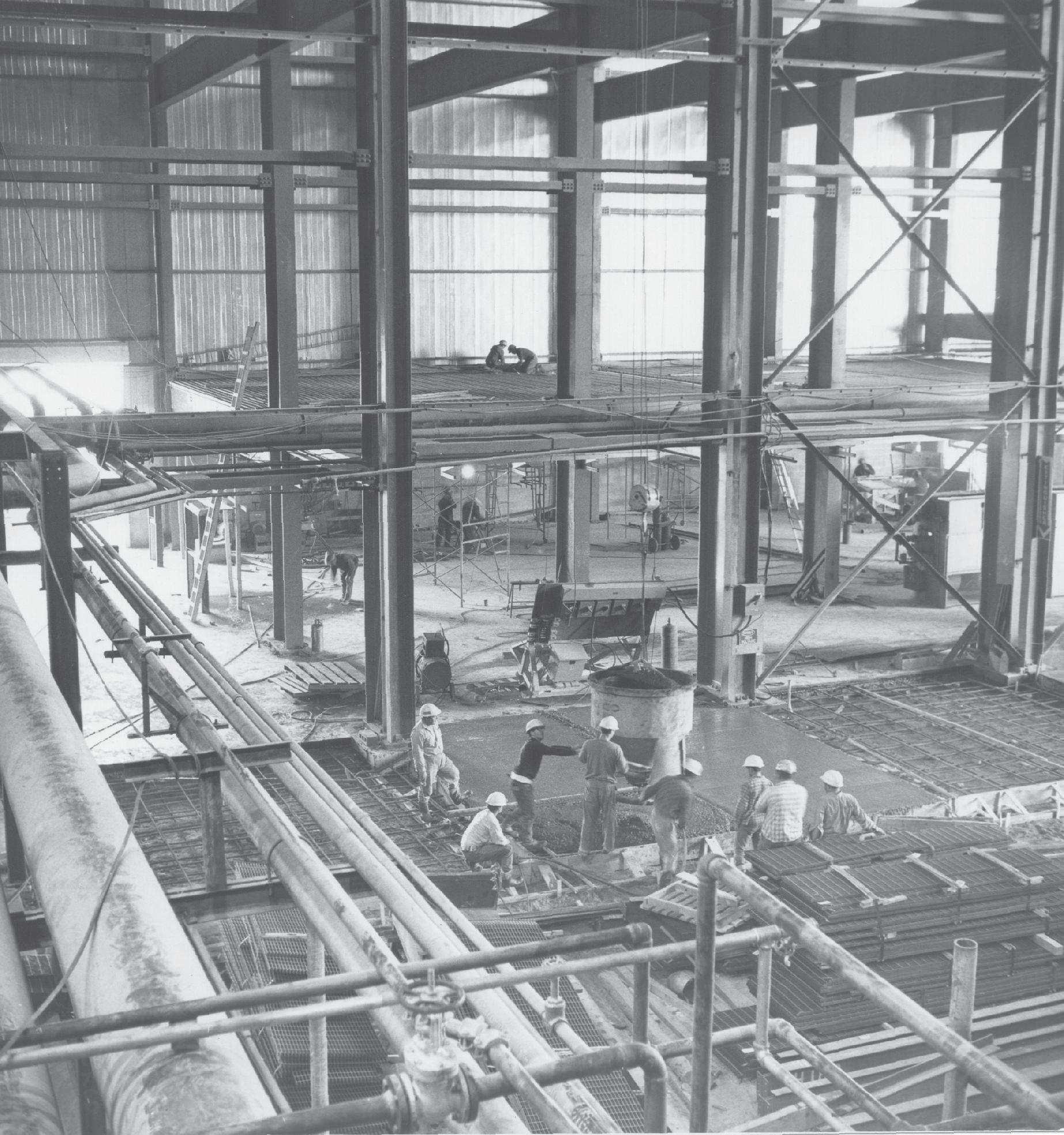

Following the announcement of the discovery on April 16, 1964, limited testing was done by several companies as soon as drill core was available. During 1965, bench-scale and pilotplant programs were pursued at Lake field Research of Canada Limited and at the federal Mines Branch in Ottawa. When the bench-scale testing was fin ished, the decision was made that the company would mine two types of ore. By then, enough information was available to start designing the con centrator (more commonly known as a mill).

When the decision was made in March 1965 to go ahead with the pit-railwayconcentrator complex, it soon became obvious that two of the major prob lems were soils and transportation. The whole vicinity of the pit was cov ered with muskeg, glacial till and clay. Soil tests proved the clays to be very weak and inclined to flow. In most cases they were deeply de

posited on steeply inclined sub-strata. Only two small bedrock outcrops, one on each side of the pit, were found. One of these had to be reserved for the pit primary crusher.

It soon became evident that there was no site near the pit suitable for the large building and equipment identi fied for the concentrator.

Furthermore, the transportation of large quantities of cement, steel and machinery would be impossible, be cause neither the permanent road nor the railway had been started.

The choice of a concentrator site was therefore primarily dictated by the proximity to an existing railway and highway and the presence of a suit able expanse of surface bedrock for foundations.

An area of stable bedrock situated adjacent to Highway 101 and the On tario Northland Railway, inside the City of Timmins but 15 miles east of City Hall was picked. The location would eventually become commonly known as “The Met Site”, a nickname for what would more technically be called the metallurgical complex. The good news is that there was suf ficient bedrock for the entire con centrator and for future expansions. The main pipeline of Northern and Central Gas was only a few hundred yards away and an excellent source of

power was close at hand.

The site was 17 miles from the pit by railway but the company already knew that a railway would have to be built regardless of which site was chosen.

Thus, the metallurgical site 34 miles by road from the pit was selected.

On completion of the Lakefield pilotplant testing, two full-scale produc tion pilot-plant programs were started in the Timmins area, at the Kam-Ko tia copper mine and Broulan Reef gold mine.

At Kam-Kotia, 1,100 tons per day of copper-zinc ore was milled for 10 days a month between October, 1965 and October, 1966.

At Broulan Reef, a 400-tpd flotation plant was installed to process silverlead-zinc ores. The Broulan Reef operation was run from April to De cember, 1966. Production started at the Kidd concentrator in November, 1966.

The Kam-Kotia and Broulan Reef programs proved to be quite valuable, because the information obtained was used to verify and modify the concen trator design.

They also served as an excellent train ing ground for the staff being acquired to operate the concentrator. A wel come bonus was that the concentrates

Cont’d from pg. 42 produced at the two local mines were sold at a profit. Primary crushing was performed at the Kidd Creek Mine, also inside the city. Run of mine ore was delivered to the concentrator at the metallurgical site by train Power and fuel were obtained from the hydro and natural gas lines which pass close to the concentrator site. Water was obtained from the Frederickhouse River, 6 miles east of the concentrator.

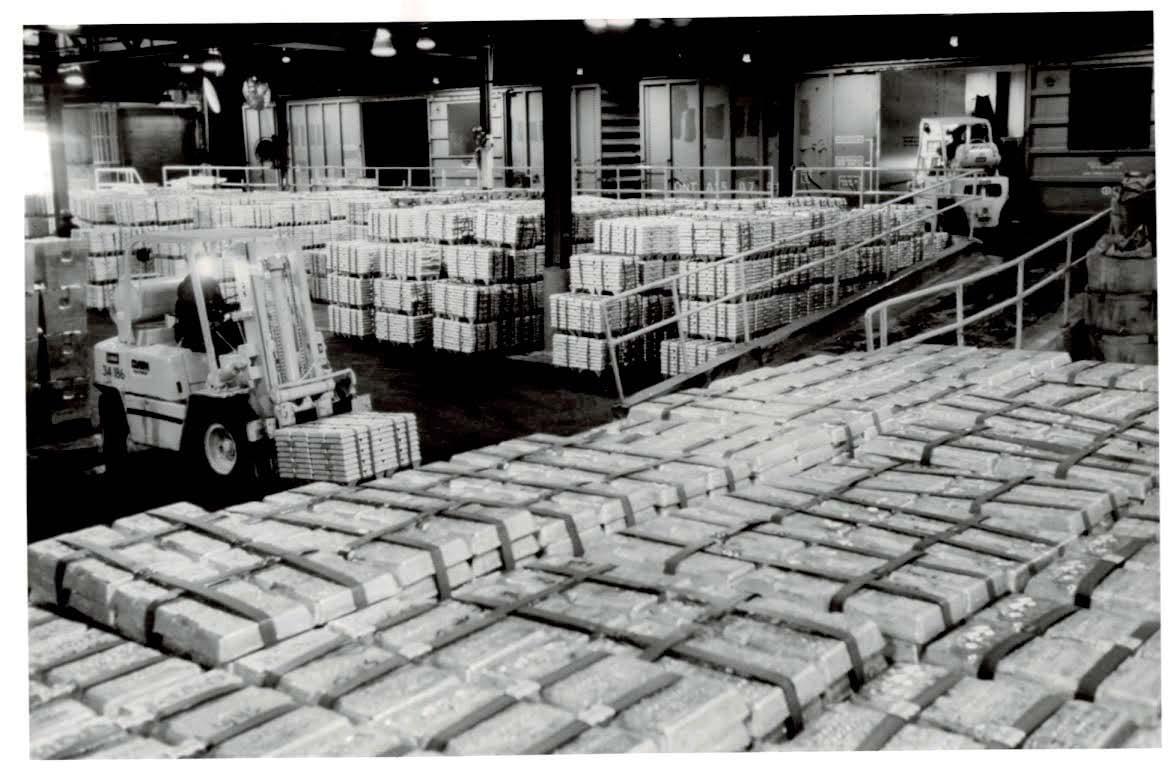

The main concentrator building was a large structure 500 by 640 feet by 90 feet high and contained facilities for fine crushing, crushed ore storage, grinding, flotation, concen trate handling and reagent handling.

Located in the same building were the machine shop, ware house, metallurgical laboratory, pilot plant, men’s change room, sample preparation area and an assay laboratory. The first copper-zinc circuit was started up in November 1966 followed shortly after by the second copper-zinc circuit the following January and the lead-zinc circuit in February.

It was operating at capacity by March 1967.

Originally designed to handle 9,000 tons per day, the con centrator was quickly expanded to treat 10,000 tons per day.

Two different ore types were processed by selective flota tion in the three individual circuits to recover copper, lead and zinc concentrates.

In 1973, a smaller circuit was added to recover pyrite and tin concentrates from the combined zinc tailings of the three main circuits.

A fourth circuit was completed in May 1978 to handle in creased feed tonnage from the expanded mining operation.

By 1981, the concentrator treated 12,250 tonnes per day. Normally, three circuits treated copper-zinc ore at a com

Cont’d from pg. 42 bined rate of 6,500 tons per day; the third circuit treated 3,500 tpd of sil ver-lead-zinc ore.

With the start-up of the tin plant in December 1973, seven concentrates were produced: high silver copper, low silver copper, lead, low silver zinc, high silver zinc, pyrite and tin. At 1974 market prices, the pyrite con centrate had no value so it was stock piled for future use. Concentrate pro duction, exclusive of pyrite, averaged 2,400 tpd.

Recycling of mill water was imple mented in 1975. The concentrator underwent many revisions and improvements since it was built.

Some of the changes in the concentra tor made after start-up were anticipat ed in the original design. Here are the highlights: •1982 tin plant decommissioned •1985 hit peak throughput of 4.53M tonnes ore •1988 ‘C’ ore depleted, all divisions

treating the same ore •1993 Distributed control system (DCS) installed •1993 Custom milling of a copper-gold ore from Wisconsin (Flambeau) begins; ends in 1997 •1995 Outotec high rate thickener in stalled in the tailings area to increase underflow density for spigotting on cone •1996 PI System installed for sharing of process information •1998 ore tonnage drops to 2 division demand, A division shut down •2001 Pond E water polishing pond in stalled in tailings area •2004 Begin custom milling a Copper, nickel ore in D division after re-design of process and equipment (Montcalm ore body)

•2009 Custom milling of Montcalm ore body ceases •May 2010 Copper and Zinc Smelters on Kidd Metallurgical Site close, con centrates shipped by rail for further pro cessing in Canada. •2014 Dropping tonnage results in 2nd division cycling on and off

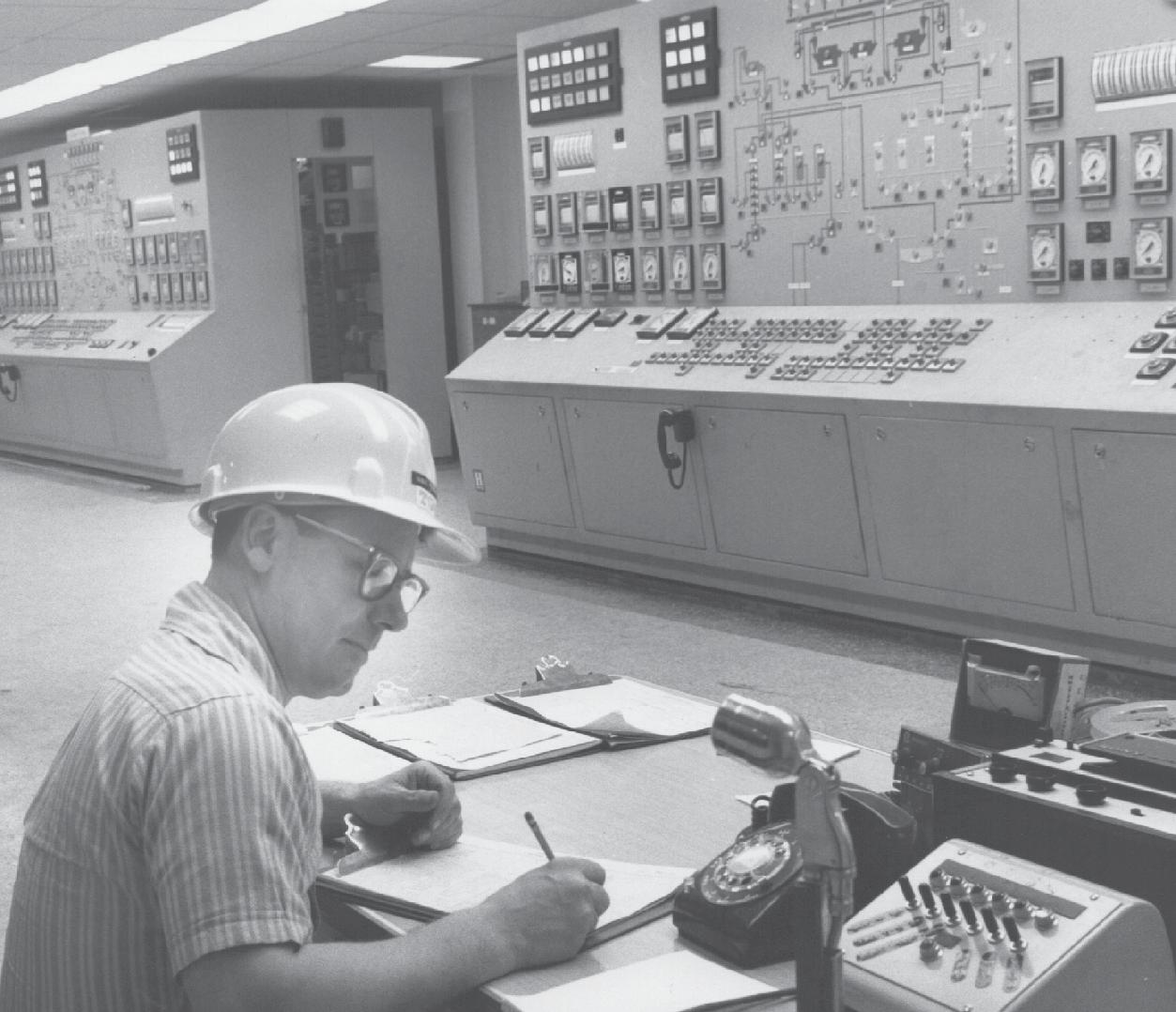

The whole plant was highly automat ed and control was coordinated from a central control room.

The treatment process followed con ventional practices, although fine grinding was required for optimum flotation recoveries.

Central control, located between the grinding and flotation sections, housed the main control room, the shift foreman’s office, the rotameter room, the X-ray analyzer room and an instrument repair shop.

With the exception of the concen trate drying section, all functions of the concentrator are operated and coordinated from the central control room that contained the essential control panels, operator’s desk, Xray read out typewriters, remote con trols for the mill water pumps, and tailings thickener, process computers and their auxiliary equipment.

Today, the Kidd Operations’ concen trator remains an efficient operation with a blend of old and new technol ogies working hand in hand.

Most mining companies are faced with an either/or decision as it relates to the extraction of their orebody. It boils down to two basic choicesopen pit or underground. It is unusual to see both choices executed at the same time.

Then again - Kidd Creek was not your typical mine property. The massive amounts of copper, zinc and other base metals mined until 1972 from Kidd Creek were extracted by open-pit methods. To assure continuity of production, preliminary planning for an under ground operation was started in 1968 only four years after the start of the

open pit and a full-time planning staff was in place by the following year.

The Kidd Creek No. 1 Mine shaft was located on the footwall of the ore zone, about 400 ft. from the edge of the pit.

The company wanted to use the under ground operation to replace the high ore tonnages, about 10,000 tons per day, that were coming from the Kidd Creek pit. The challenge and ultimate goal was to execute the underground operation without interfering with or disrupting operations in the pit.

In order to achieve a balanced ore mix to the concentrator, engineers de cided in 1971 that some of the under

ground ore would be mixed with ore from the open pit.

Underground development began in mid-1969. Vertical access to the mine was to be through a single vertical shaft and a 17% declining ramp from the second bench of the open pit. The need for early development of un derground ore was important. It was a significant factor in the selection of a ramp as one way to access the mine.

The single shaft was chosen because it offered the lowest construction and operating costs of all the options at that time.

Yet the tremendous value of the ore

vided free laundering of work clothes. In the dry, clothes baskets were sus pended beneath the change benches instead of being pulled up to the ceil ing, giving the changing room an open, brightly lit appearance. The room beneath the dry was heated and well ventilated to remove cloth ing moisture and odors.

body allowed planners to provide for a high degree of mechanization in a completely trackless operation. The company spent millions on equipment, rubber-tired jumbos, loading and hauling equipment, raise borers, and a large fleet of utility and service vehicles.

The fleet of mostly diesel vehicles presented the company with another challenge. The high degree of diesel ization prompted planning for a ven tilation system that would eventually circulate up to 750,000 cfm of air per day.

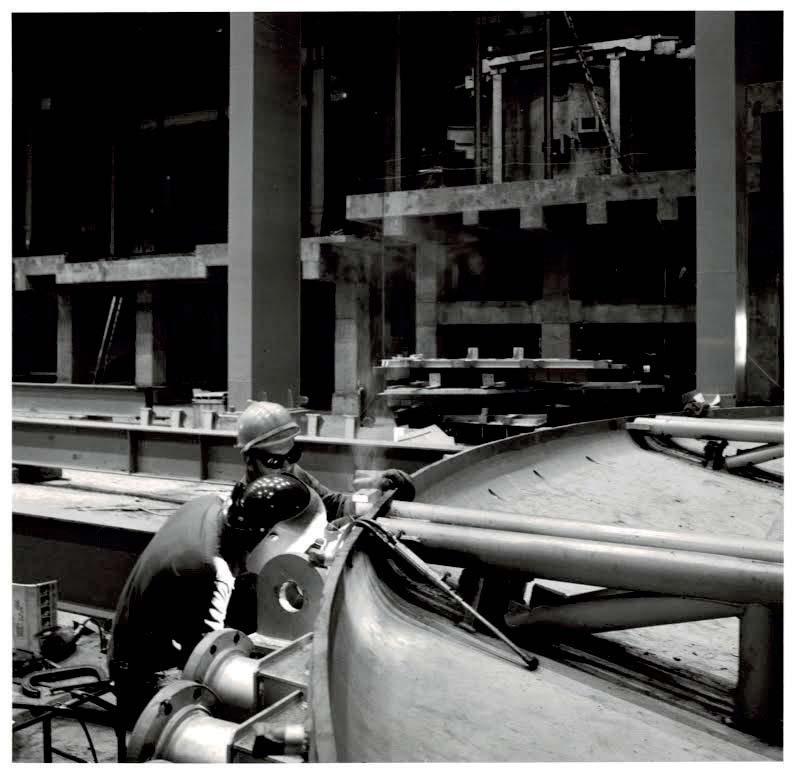

Once the major pieces of the planning puzzle were assembled, shaft sinking began in March of 1970. What follows is a detailed description of how the underground mine was fo rumlated.

The 24-ft diameter concrete-lined shaft was 3,050 ft. deep and was com missioned in March 1972. The 17-ftwide x 10-ft-high ramp was advanced to the 1,200 level and eventually reached the bottom of the shaft. Some production ore began to move in the shaft in June 1972 through skip loading from a lip pocket on the 800-

ft level.

Prior to the commissioning of the shaft, as much as 20,000 tpm of de velopment muck was moved out of the ramp in 20-ton Wagner MTT-420 Teletrams.

Engineers were given another task. An underground crushing plant was com pleted by the end of 1972. That way, all underground ore and development waste would be crushed underground before being hoisted to surface. Mining manager Bart Thompson had been specifically hired in 1965 by Texas Gulf to phase out the open pit and to develop underground opera tions. He served as general manager from 1974-80.

He spoke enthusiastically in 1972 of service facilities the company was providing for its underground work ers. Each main level service area in the mine included a heated lunchroom with fluorescent lighting, a washroom with hot and cold running water, and flush toilets - a vastly different envi ronment that Kidd’s mining brethren in nearby gold mines were unaccus tomed to.

Above ground in the change house, there was a laundry facility that pro

Shaft hoisting units included two 27V4-ton skips traveling at 3,250 fpm; a main cage, 17 ft. 9 in. x 7 ft. 9 in. x 24 ft. 6 in. high, on steel guides; and an auxiliary cage on wooden guides. Galvanized steel compo nents were used throughout the shaft to minimize the effects of corrosion, wear, and oxidation.

The minimum thickness for the con crete lining of the shaft was 12 inches. The Kidd Creek ramp was collared in the wall of the second bench of the open pit, 80 ft. below surface. The ramp broke through to the shaft at the 800 and 1,200 levels. (Main levels for the underground operation were de veloped at 400-ft. intervals). When it reached the bottom of the shaft, the ramp heading had required an advance of 21,000 feet. Development ore and waste were moved up the ramp prior to the com missioning of the main shaft.

Ventilation at the ramp face was sup plied by 34-in., 30-hp axial vane fans pulling through a 30-in. ventilation duct.

Concreting was used on main road ways to provide clean surroundings and low maintenance costs - it also al lowed higher-speed haulage. The mine shaft and headframe were equipped with three hoists supplied by Canadian Westinghouse. The production hoist was a 168-in. four-rope friction winder powered by

a 6,000-hp dc motor that lifted a 27.5-ton skip at a rate of 3,250 fpm. A second four-rope friction winder powered by an 800-hp motor handled the main cage. A small drum hoist handled the auxiliary man cage.

The headframe was a 235 ft. 6 in. high concrete structure. Construction began in June 1969 and the slip-formed walls were completed in October of that year.

The headframe included a large hydraulically powered ship-type crane on the top floor to erect and service equipment, eliminating the need for heavy steel and crane rails that would normally be used in this application.

The shaft and hoists were rated at about 1,000 tph. The 24 ft. diameter shaft was collared beginning in June 1969. The shaft was sunk to 3056 ft. and the headframe was slip-formed to a height of 235 ft. 6 in. The first 300 ft. of the shaft were sunk full face with a 10 boom jumbo beneath a Galloway stage. The remainder of the shaft was benched with hand held machines and mucked with two wall-mounted Cryderman units.

The shaft was equipped with two Westinghouse friction hosts to provide 15,000 tpd hoisting capacity, 20 ton main cage service and a small auxiliary cage. Levels were established at 400 ft. intervals and a single loading pocket built at the 2860 level.

The haulage system and the 42 x 65 in. Allis-Chalmers gyratory crusher became operational in June 1973. Two addition al 5000 ton loadout bins, a new change-house, office, compressor and powerhouse facilities were also built at this time. All in all, the underground operation is an engineering marvel and a testament to the determination of the mine’s owners, the talent and ingenuity of staff, and of course, the star of the show, the orebody itself.

The extraordinarily unique Kidd Creek orebody tested some of the best mining engineers in the world. Its abundant mineral content led to some of the most innovative operational plans the industry has ever witnessed. Who in their right mind for example, would ever contemplate building a mine under another mine?

November 3, 1978 was a special day in the history of Kidd Creek as it marked the completion of the shaft for Kidd’s No.2 mine.

Today, the 50-year-old operation is comprised of four mines, No.1, No.2, No.3, and the Deep or ‘D’ Mine. The first two are traditional mines topped with familiar headframes while the third is an internal mine that starts on the 4700-foot level. ‘D’ Mine, as it is known, is also an internal mine, it sits under the other mines.