4 minute read

Canada’s North

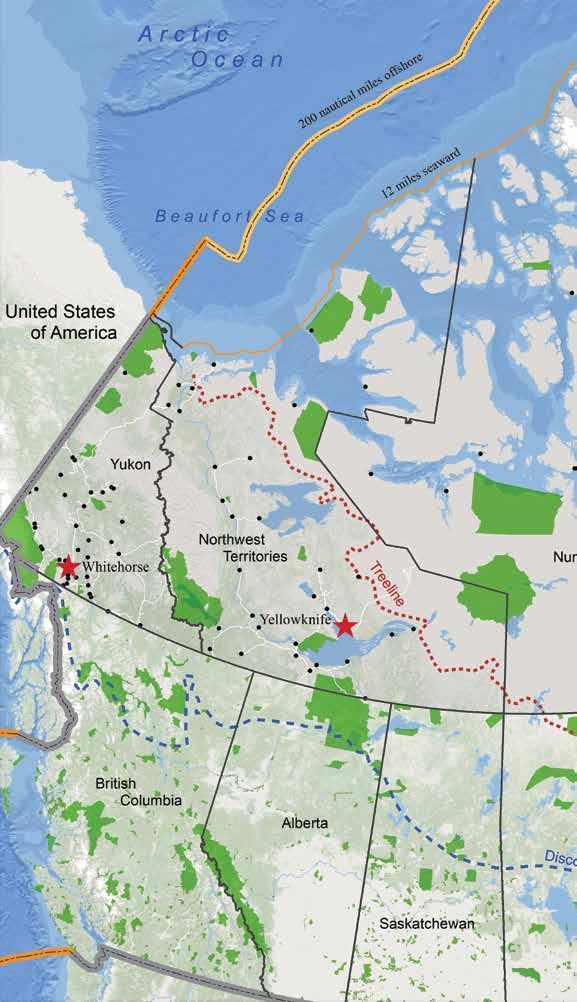

Canada is a northern country; and much of Canada is arctic country. ‘The North’ includes all of Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut, and the northern areas of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador. Canada’s geoscientists are particularly knowledgeable and experienced in dealing with northern issues and opportunities, including climate change, arctic science, water management, sustainable mineral and energy development, and protection of the North’s unique and fragile polar environment. Geoscientific studies help us understand how northern landscapes function and contribute to Canada’s assertion of sovereignty over this vast and important area.

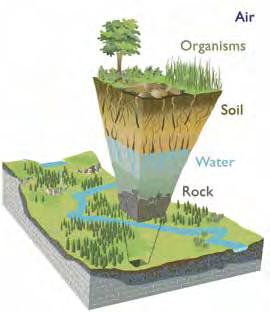

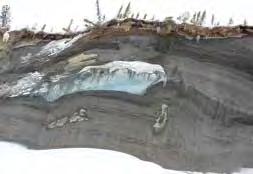

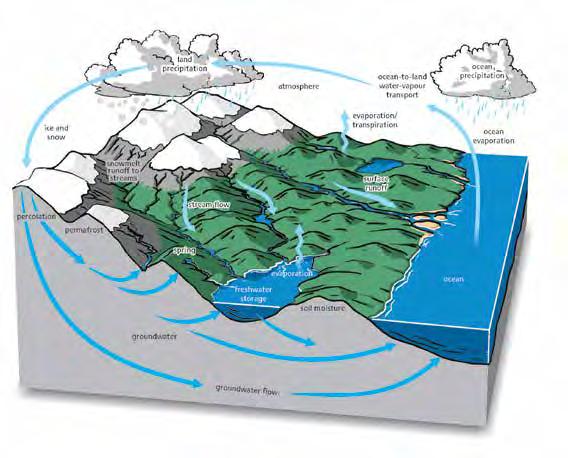

The North, defined by the southern edge of the zone of discontinuous permanently frozen ground (permafrost), is a vast area of land, lakes, sea, and ice in varied landscapes. Ice caps on Arctic islands are vestiges of the continent-covering ice age glaciers. The position of Canada’s treeline, where boreal forest meets the treeless tundra, is largely controlled by the arctic front – the boundary between dry–cold arctic air and warm–moist southern air.

Canada has 162 000 km of Arctic coastline and geoscientists are responsible for mapping and establishing an understanding of surficial and bedrock geology along that coastline. They gather scientific evidence needed to manage Canada’s polar continental shelf, an underwater landmass that extends from the continent, for environmental management, pollution protection, and preservation of the marine environment, as well as resource identification and development.

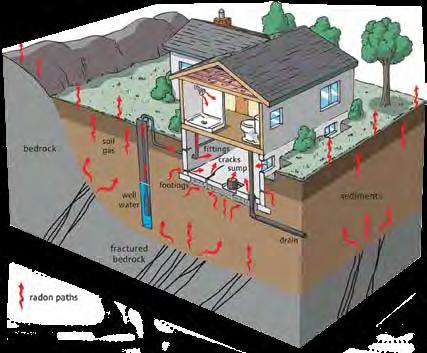

Building infrastructure in the North is challenging because of permafrost, a harsh climate, and vast distances between settlements and from resources. Geoscientists assess construction risks associated with building on permafrost and provide mitigation advice on northern infrastructure development.

Incorporating the traditional knowledge of Indigenous people into geoscientific studies, resources development, and environmental management decisions across the North is important. Community engagement, education, and outreach with First Nations, Inuit, and Metis benefits from geoscientists as key participants.

In the Northwest Territories, mining contributes (directly and indirectly) more than 40% of the Gross Domestic Product. The North contains iron ore, nickel, gold, and diamond mines. Canada is the third-largest diamond producer in the world, with four mines, all located in the North. Relatively under-mapped and under-explored, the North offers opportunities for new discoveries coupled with responsible development.

H. Falck

J. Ryan/NRCan

H. Falck

H. Falck

R. Fensome/NRCan H. Falck

H. Falck R. Fensome/NRCan

H. Falck H. Falck The Beaufort-Mackenzie Basin hosts immense petroleum resources and significant potential for the discovery of natural gas and gas hydrates. In order to meet Canada’s future energy requirements, geoscientists are needed not only to find the resources, but also to identify safe transportation corridors to bring these energy supplies from production sites to their users.

Isostatic rebound is a significant geological phenomenon of the North. While most of the world is contemplating rising sea level, much of the land mass in the North is still rising in adjustment to the loss of the weight of glaciers from the last ice age. The most rapid land uplift is at Hudson Bay, at an average of about 10 cm per decade. Geoscientists ensure adaptation to this uplift is appropriate for communities and developments in these areas.

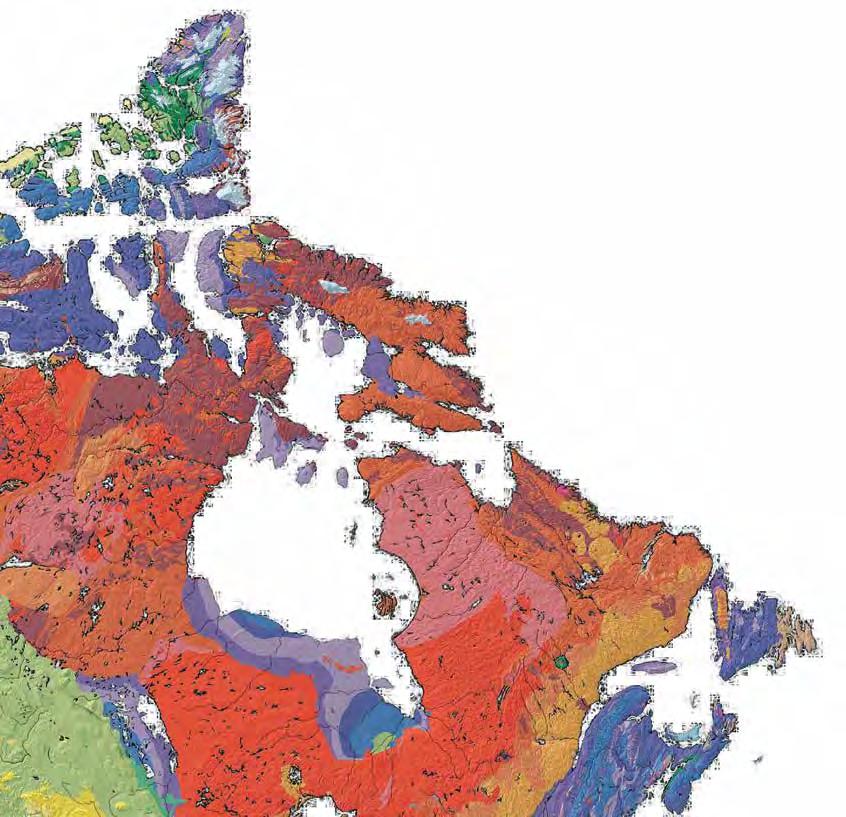

Canada’s North is home to a vast network of national parks, shown in green on the map, and protected areas. These parks seek to protect the ecosystems of outstanding natural landscapes and manage them for visitors. Many of the largest Canadian parks, including the largest, Wood Buffalo National Park, were established in the North and are being augmented by the three candidate marine protected areas. Geoscientists are integral to the parks’ establishment process, helping to define their extents and interpreting the landscape for the appreciation of visitors.

As we consider adaptation to the changing modern climate, it is important to understand climate change in the past. Lush forests existed well north of the Arctic Circle 45 million years ago. Geological reconstructions of the region show a warm, ice-free environment, with high humidity. Research by geoscientists provides a basis for understanding the history of natural climate change.

The North Magnetic Pole (used for compass navigation) moves or “wanders” over time. Changes to the position of the magnetic north pole and other polar phenomena, like the aurora borealis (or northern lights) and magnetic storms, are studied by geophysicists. Magnetic storms can disrupt power grids and damage electronic infrastructure.

The Northwest Passage is one of very few sea routes through the Arctic islands, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The melting of Arctic sea ice raises the possibility of new trade routes, energy production, and tourism, as well as the potential for geopolitical conflicts and environmental damage. Geoscientists continue to work closely with hydrographers and other specialists to chart, map, and understand both the landforms and the seafloor in our northern regions.