Tony Albert

Paul Bong

Hannah Brontë

Michael Cook

Fiona Foley

Dale Harding

Gordon Hookey

Archie Moore

SOUTH AFRICA

Kudzanai Chiurai Mohau Modisakeng

Zanele Muholi

Athi-Patra Ruga

Berni Searle

Mary Sibande

Buhlebezwe Siwani

EXHIBITION SPONSORS

Andrea May Churcher, Director, Cairns Art Gallery

Carly Lane, Curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, Art Gallery of Western Australia

M. Neelika Jayawardane, Associate Professor of English, State University of New York - Oswego

Continental Drift: Black/Blak Art from South Africa and north Australia is the first major exhibition in a new Gallery program that examines Australian Indigenous race and representation within the context of global black art and culture.

Presented in partnership with the Cairns Indigenous Art Fair, the exhibition Continental Drift aims to challenge the uncomfortable truths that surround the colonisation of Australia and South Africa and how these truths have impacted on and shaped the construction of contemporary black/blak personhood. Australia and South Africa have shared but different experiences of British colonisation, and in this exhibition, it is the way that the artists from both countries have chosen to interrogate and interpret these experiences that is most revealing and challenging.

The decision to focus on Indigenous Australian artists living in the north of the country, with cultural connections to Queensland relates to the Gallery’s research interests and the specific conditions of colonisation that prevailed in Queensland. However, the reality of colonisation and the resulting experience of ‘unbelonging’ in one’s own country has resonance for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists in Australia.

The impacts of colonisation on the artists from Australia and South Africa respectively are examined in this publication through the writing of Carly Lane, Curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the Art Gallery of Western Australia and Professor Neelika Jayawardane, Associate Professor at the State University of New York - Oswego. The depth of knowledge and understanding that these two writers bring to this project provides a powerful framework to explore the cultural, social, political and historical narratives that have informed each of the artist’s work.

From the outset all the artists in Continental Drift enthusiastically embraced the exhibition concept and generously shared their work, stories and experiences. We are indebted to them, their galleries and the private lenders for making such an exceptional body of work available for the exhibition.

Without the generous financial support of The John Villiers Trust, Cairns Indigenous Art Fair and Gerald Sanyangore of Another Antipodes Inc. we would not have been able to bring together such a diverse range of artists and works of art from South Africa and north Australia. We are extremely grateful to them for their commitment to this project.

Finally, I would like to congratulate all the Gallery staff involved with this project, particularly senior curator Julietta Park whose dedication and commitment enabled the Gallery to realise such an ambitious project.

Andrea May Churcher Director

Carly Lane

IMAGE PAGE 5

Michael COOK

Invasion(EveningStandard) 2017 (detail)

61 x 74 cm

Collection of Phil Brown and Sandra McLean, Brisbane, Queensland

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

In Australia, colonisation is a difficult subject to raise. So much has been gained by the advancement of time, technology and being a part of a global community. So much has been lost because of the lasting effects of colonisation. Aboriginal environmental and cultural knowledge about this country is now fragmented; strong in some places and limited in others. Australia, as a society, does not understand the full impact of colonisation, especially on contemporary Aboriginal people who continue to brace themselves against it. Though it is with great pride that I notice that the Aboriginal artists in Continental Drift do much more than brace.

According to the Macquarie Dictionary , ‘continental drift is a theory concerning the move of continents away from an original single landmass to their present position’. (Delbridge & Bernard 1998) If we take the view that colonisation is the original landmass, then the artists in the exhibition must be the people shifting away from a framework that is no longer viable, or in concert with their communities’ ideals.

Featuring works of art by eight Aboriginal (Australian) artists and seven South African artists, the exhibition Continental Drift digs deeply into the subject of colonisation. Tony Albert, Paul Bong, Hannah Brontë, Michael Cook, Dr Fiona Foley, Dale Harding, Gordon Hookey and Archie Moore investigate some of the different aspects of colonisation they encounter, as do the South African artists in the show. The South African artists are Kudzanai Chiurai, Mohau Modisakeng, Zanele Muholi, Athi-Patra Ruga, Berni Searle, Mary Sibande and Buhlebezwe Siwani. Together they present a range of subjects and media such as photography, textile installations, mixed media, painting, video and works on paper. The assembly of Aboriginal works in Continental Drift highlights two salient points about colonisation, which I will address shortly. However, before I examine these two points, it is essential to say a little about why artists engage in colonisation and, after that, briefly review colonisation, the event.

While artists like Fiona Foley and Dale Harding regularly explore the past, many contemporary Aboriginal artists do not directly attend to the subject of colonisation. The influences of colonisation underline much of their work. One reason for this is that colonisation does not manifest solely as a past moment in time, but also as a condition and feature of contemporary life. This is not surprising given colonisation is a foundation stone of Australian society and our present values today. Nonetheless, a good many artists prefer to focus on other more traditional

aspects of Aboriginal art, life, culture and experience, sometimes to the exclusion of all else. Thus, the eight Aboriginal artists in Continental Drift are drawn from a select group of practitioners who engage with the subject of colonisation and other controversial topics. Coincidentally, the chosen artists either work or circulate in the Brisbane visual arts community, as well as nationally and overseas.

The term ‘Blak’ can be ascribed to those artists who touch on colonisation and political affairs in their work. The first use of this term among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists is attributed to Destiny Deacon, a photographer, who used the word and term ‘Blak’ in the title of her 1991 photo series, Blak lik mi, (Croft 1993, cf Perkins 2010) and later again, in 2004, as part of the title of her solo exhibition, Walk and don’t look Blak, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. (Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, 2018) The term has since gained momentum as a reclamation of their mind, body and experience of the world. For them, it is a sign of self-determination and of an empowered self that chooses

to talk, think and act independently of Western prescriptions and stereotypes of how Aboriginal and other people of colour should perform their identity. The term is regularly used by different artists in the exhibition.

In Australia, colonisation began in 1788 with the landing of the British at Sydney Cove, and, although rapid, it spread to other areas of Australia at different times. Often, penal settlements and outposts of the colony of New South Wales were the first institutions to be established outside of Sydney. One example of the rapidity of settlement in Australia is the formation of Queensland. In 1824, the British began a penal settlement south of modern-day Brisbane, with small outposts at Cleveland, Redbank and Limestone (Ipswich). The penal settlement closed in 1839 and later opened as a free settlement in 1842, where newly arriving migrants converged. Also, in 1840 pastoralists began to drive sheep northward, up to the Darling Downs located on the Dawson River, and beyond. In 1859, Queensland became its own colony, and by 1884, the occupation of Queensland by settlers was complete. (Fitzgerald 1982) In this early colonial period, the Aboriginal population in Queensland rapidly declined. C.D. Rowley measured the sharp fall in population numbers from 1788 to 1966. In 1788, 100,000 Aboriginal people were estimated to live in Queensland. By 1901, the population had fallen to 26,670 and then to its lowest figure of 14,454 in 1921. (C.D. Rowley 1972, p. 384) Thus, between 1788 and 1921, there was an 85.5% drop in the Aboriginal population. These statistics reveal how fast and brutal colonisation was for Aboriginal people. Colonisation

decimated the Aboriginal population in Queensland, and across Australia. It set Aboriginal people up to endure the most severe disadvantage and marginalisation in Australian society, which continues through to today.

Aboriginal people are keepers of some of our nation’s colonial secrets. 1 Through personal experience, living memory and/ or investigating the colonial era, Aboriginal people collectively carry stories of some of the most horrific misdeeds done in the name of nation-building. We equally carry the burden of these secrets in our DNA. Our heartache and malcontent are compounded by Australian society’s general resistance to admitting that there is internal strife, whether it be now or in the past. It seems Australians have an unspoken national code of silence where, what happens inside the home, stays in the home. Australia, in general, cannot openly face the shadow side of itself, but as Continental Drift makes clear, individuals can and do focus on elements of this. In reflecting on the experiences within Aboriginal Australia, artists such as Dale Harding, Fiona Foley and Paul Bong examine some of the less glorifying aspects of Australia’s ‘settling-

in’ period. However, each artist takes a different route back in time and combines different subjects and media to do so.

In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs typically receive a neutral to hostile reception. In this climate, the majority tend to be uninterested in the names and deeds of early colonial figureheads who shaped the lives of Aboriginal people. However, they are of interest to Fiona Foley, an artist and academic, who investigates the intersection of Aboriginal and settler relationships. Two such figures feature in her most recent photo series, Horror has a face 2017.

Archibald Meston (1851–1924) and Ernest Gribble (1868–1957) - one a government man, the other a man of the cloth - had long careers in Aboriginal affairs in Queensland. Foley notes these men were ‘central to Queensland’s The Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act , 1897’. (Foley 2017, Martin-Chew 2017) Meston, the central figure in the photographs by Foley in Continental Drift , was the

Southern Protector of Aborigines from 1898 to 1903. As protector he controlled almost every aspect of the lives of people whom he governed.

Five photographs from Horror has a face explore the power of Archibald Meston and men like him in the late 1800s. The control and domination Meston had over Aboriginal people is symbolised by a gun, wooden box and the kangaroo skin in particular. His power is further reflected in the master and servant relationships enacted in the precisely staged scenes. Aboriginal people, including one played by the artist, are seen tending to Meston’s needs - pouring tea, chopping wood or having to sit or stand by his side. Although Foley imagines each scene, they stem from the stories, quotes and images that she collects about this period of colonisation. Moreover, other vignettes in the set of five photographs give us cause to reflect on other forms of power asserted during this period. Opiate of opulence 2017 addresses the widespread use of opium to enslave Aboriginal people in opium dens and on pastoral stations. The impact of Meston’s power on Aboriginal people, families, and their future is also considered. Both Smouldering pride 2017 and Watching and waiting 2017 advance the notions of agency and defiance, as well as loss and intergenerational trauma that have continued into the present.

In contrast to Fiona Foley, Dale Harding explores lesser-known events rather than people in colonial history. On 27 October 1857, and in retaliation for the murder of twelve Iman people, a group of Aboriginal men attacked the Fraser family and their employees at Hornet Bank Station in central Queensland. Twelve people died at what is known as the Hornet Bank massacre. Sylvester Fraser, a fourteen-year-old boy, was the sole survivor of the attack. (His brother, William, also survived on account of being away.) (Reid 1981) But this event is not what Harding, a multidisciplinary artist, explores in his installation Black days in the Dawson River Country, Remembrance Gowns 2014. Instead, he reflects on the aftermath of the attack. Over the course of several months, and as acts of “justice”, William Fraser, paramilitary groups of settlers and the Native Police indiscriminately hunted down and killed upwards of three hundred Aboriginal men, women and children from across several districts. Objects in Harding’s installation signify elements of the reprisal.

Black days in the Dawson River country, Remembrance Gowns comprises several objects. These include a wall painting of red ochre from Ghungalu country, two handkerchiefs, a period dress that serves as a remembrance gown, and ochre splatters that symbolise the blood spilt at Hornet Bank station. In the original showing of this work at Linden Gallery, Melbourne, in 2014, a different set of antique handkerchiefs (as a memento mori) were used, embossed with the names of Sylvester and William Fraser. For Continental Drift , Harding replaces the originals with two new handkerchiefs that instead serve as symbols for Country, solidarity and compassion. About this replacement, Harding says, ‘The original handkerchiefs can be let go to history, just like the two main perpetrators of the brutalities that they identified. My preference is to release those perpetrators from my future’. (Harding 2018)

For Harding, the wall painting registers an important cultural and aesthetic return to the traditional mark making of his people - the Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingal peoples of central Queensland. The painting also represents a tally of the three hundred innocent lives lost. For Continental Drift , Harding invited Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artist and Cairns Art Gallery curator, Teho Ropeyarn, to share in the ritual of remembering Harding’s ancestors. Harding writes:

Teho will perform the tally/composition of stencils in red ochre in remembrance of the Aboriginal victims of those violators [Fraser and company]. And, in the process of making the ochre stencils, Teho will be invited to clean up or to wipe his face/mouth/chin/hands/body/workspace with the two (substitute) handkerchiefs; in the same way, I always use a bath towel to complete the ritual for this wall painting. (Harding 2018)

Overall, Harding’s work is about more than remembering lesser-known colonial tragedies, it is also about contemporary ritual, unity and continuing relationships to Country.

Colonisation has affected the amount of traditional cultural knowledge and practice that the current generation has inherited. This is especially the case for people in the regions and states that were colonised first. Paul Bong, a printmaker, explores this impact in Memories of Oblivion 1–5 2018 which is a series of coloured etchings that depict rainforest shields (bigunu) . Long and wide and carved from soft wood, 2 these decorated shields were traditionally made and used by the Aboriginal peoples who lived in the rainforests of far north Queensland. Still created today, these shields are a symbol of people, place and culture. Interestingly, Bong depicts the back of the shield, perhaps to reinforce that there is a colonial backstory to contemporary Aboriginal life.

In a linear sequence, the shields present a holistic overview of cultural dispossession. One by one, they show the disappearance of Aboriginal motifs and the increasing emergence of the Union Jack across the surface of the shield. For Bong, and others like myself, the etchings illustrate that, over the two hundred and thirty years of colonisation, Aboriginal traditional knowledge and practice have been, to varying degrees,

erased and gradually replaced by Anglo-Australian culture. The artist’s statement for Memories of Oblivion 3 notes, ‘Cutting the heads off is what took place from 1788; all our ancestral knowledge was taken away from us; our language, our songlines all that we heavily relied on was taken away’. (Bong 2018) Moreover, as the unchanging shape of the shields symbolises, cultural conversion has not been done in full, nor can it change our sense of identity. Aboriginal people will always be Aboriginal.

In the face of these cultural changes, but not defeat, Bong optimistically looks toward the future – maybe to a post-colonial era – where healing happens, and equality is strong. About the future, and Memories of Oblivion 5 , the artist says:

From 1770 through to 1990, right up to now, 2018, our hearts will live on and are still strong with the chronicles that once changed Australia forever. We may not be able to change what has taken place, but we must for the next generation acknowledge what has been done, and move forward with respect and understanding toward one another. Healing will come, and the heart will live on to carry on the last bit of knowledge we have of the land. (Bong 2018)

Admittedly, many non-Aboriginal people in Australian colonial history have witnessed and experienced the darker side of nation building. Historians such as Raymond Evans (Evans 2007) and Patricia Crawford (Crawford & University of Western Australia 1983), for example, note various incidents of deceit and oppression, including when scores of English migrants were sold, and sailed on, a dream of prosperity. Upon landing at the Port of Brisbane they found themselves irrevocably destitute. (Evans 2007). And, in Western Australia, Irish Catholic women were sent to the goldfields in Kalgoorlie to work as prostitutes. (Crawford & University of Western Australia 1983). Many miners and workers were exploited, ultimately leading to the formation of unions in Australia. Each one of these incidents was unjust by today’s standards. But I propose they are of a different type of injustice to those that were heaped on Aboriginal people throughout the early colonial period. The difference lies in the power structures that frame these events. To experience difficulty as a settler and inside the same power frameworks as your oppressor is markedly different from the challenges experienced by those being colonised. Imposing a new social and cultural structure on another by force, including genocide, is an incomparable event.

In assembling the stories and works by Foley, Harding and Bong, Continental Drift reaffirms what many Aboriginal people know - colonisation was a brutal exercise, so “cruel” and normalised that mainstream Australia has, through the decades, either left it in the past or developed social amnesia.

But this is not the case for Aboriginal people, especially not artists, who carry and lay bare the secrets of our nation. Together, these artists expose the brutality in an attempt to process it, as well as provoke others to engage in these secrets - to make them secret no more. The artists have done this effectively and creatively: Fiona Foley and Dale Harding investigate the carriage of colonisation and along with Paul Bong demonstrate its overall impact today. Their activities go some way toward transforming the dislocation that Aboriginal people have felt since British settlement. However, their works also relate to a second discursive feature of Continental Drift , which is the contemporary experiences of Aboriginal people, and the legacy of colonisation in particular.

The definition of ‘legacy’ is the handing down of anything from an ancestor or predecessor to another. (Delbridge & Bernard 1998) The legacies of colonisation for Aboriginal people are many, and indeed too many to represent in Continental Drift Though what occurs to me is that there is a real mix of legacies, which in this case take the form of experiences and social frameworks that can be specific to one generation, or shared across generations. One legacy of colonisation for Aboriginal people has been the continued experience of (institutional) racism in Australian society, while another legacy is the forging of a pan-Aboriginal identity across the Aboriginal nations, including our solidarity with Torres Strait Islander people who are also indigenous to Australia. In fact, one legacy (that of resilience and courage) has been used to challenge the existence of others, which are oppressive at their core. Across at least the last three generations, and certainly before my birth in the 1970s, more and more Aboriginal people and our supporters have been mobilising. Individually and collectively people are protesting against the systemic oppression that Aboriginal people, and other minorities, face in this country. To borrow a phrase used in other discourses, ‘if we have to experience it, then you have to listen to it’. Such actions are no more apparent than through the process of art. Gordon Hookey, Archie Moore,

Tony Albert, Hannah Brontë and Michael Cook are equally inspired to draw attention to the small and large legacies that we have inherited since the coloniser sought to colonise both the land and its people. The hardships seem almost insurmountable and yet Aboriginal people are still here and resilient.

Australian politics, society and culture purport to be about equality for all. People in Australia subscribe to this vision, for it is a good one, yet find it difficult to recognise it as political spin. Fairness in this country is for the most part, skin and gender-based. If you are white - that’s good; if you are white and a heterosexual female - that is still good; and, if you are white and a heterosexual man then, let’s face it, you have won the jackpot of human-lotto. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and others who are equally displaced do not register in the upper quarters of Australia’s sliding scale of values. These structural inequalities of our society are the basis of Gordon Hookey’s painting, Conject jar: Pig-Men-Tatio n 2006.

Hookey, a painter and sculptor, presents some seriously witty, pictorial jibes and text-laden satire in his five-metre painting. Divided into small and large sections, the canvas features a series of eight comic book scenarios which double as metaphors for the different issues he was concerned with at the time. In an organic stream of consciousness, the eight scenes take shape and connect to each other in the same way thoughts can lead from one to another. Hookey confides that the painting starts with the two figures from the children’s (then) all-male entertainment group, The Wiggles, performing on a stage. (Hookey

2018) One man is wearing an orange jersey, while the second man generously fills a green one. The vignette is a metaphor for first and second-class citizenship in Australia.

Hookey points out that the three white members of the Wiggles each wears a jersey in one of the three primary colours of the colour wheel. The fourth member, who is of Asian appearance, is put in a purple sweater, a secondary colour on the wheel. With this in mind, Hookey imagines a fifth and sixth Wiggle - a disabled, gay man and an overweight Muslim. This idea is utterly preposterous and funny, but it is based on remarkable insight about privilege and the social positions that people are assigned to in Australia. The irony in this painting is that the ousted orange and green Wiggles successfully play to a crowd of blonde-haired, blueeyed men and women, and not to children. They are more successful than the original group. Other scenes in the rest of the painting also offer valuable insight.

Djon Mundine notes that ‘political cartoon did not come into being until around the time of the British appearance in Australia’. (Mundine 2008, p. 22) This type of protest art suits Hookey, who completes the painting with words and puns, some of which he creates himself. His words reinforce his scepticism about equality in this country. And, while it (equality) did exist here before colonisation, it is not here now.

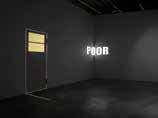

Initially, it takes time to find a connection between the experience of colonisation and the projected text works by multidisciplinary artist Archie Moore. Placed near each other in Continental Drift , Words I heard inside the home 2018 and Words I heard outside the home 2018, punch through words and phrases from the artist’s childhood that are projected onto a large screen. Each word appears in capital letters. Angela Goddard describes Moore’s use of capitals as ‘shouting, but with no sound’. (Goddard 2018, p. 12)

In the 1970s and 80s, Moore grew up in a small country town where his family was one of two Aboriginal families. (Mundine 2018) Both families were treated as outcasts. Moore gives no reason why they stayed. Was it because the families were incredibly tough mentally? Or was it because they were stuck in a lifestyle of poverty and racism that was both safe (read normalised), and hazardous to their health? Or was it both? Whichever it was, Moore existed in a state of social isolation, terrified and terrorised by the non-Aboriginal kids. The names and name-calling he experienced were neither jovial nor inclusive: ‘What colour are you, Archie?’; Michael Jackson; lazy; dirty; poor; and ‘couldn’t drive a stick up a dog’s ass’. Such taunts outweigh the two positive statements he recalls in this work – ‘good at art’ and ‘good drawer’.

Words I heard outside the home consists of twentyseven words, which appears short compared to the string of forty-two words and phrases that make up Words I heard inside the home . The latter work includes a mix of Aboriginal and English words, slang and idioms. The list features some of the words heard

by, and at times directed at Moore, by his brother, his uncle and or his father. These include: ‘everyone thought you were a girl’; ‘take you to the mission’; ‘won’t amount to anything’; and ‘skin your cap back and smell the cheese’. Some of the words featured look garbled, as if said with an accent or drunken slur – gearlee and ‘fruck! gergills a’what’.

Several examples of kindness timidly peek out from among the vulgar ones: ‘handsome young man’, ‘smart’, and nicknames Moore’s mother called him, such as ‘luckrish’, ‘kanoods’ and ‘doorish’. If there were more gentle words in his youth, then Moore has not remembered them. Or, in the spirit of the work, kinder words appear less frequently than the critical ones that Moore packs away in his mind and body.

The anxiety and depression that Moore has come to live with are likely due, in part, to repeated exposure to negative words - the semantic, psychological instruments of colonisation that take root inside and outside the home, trapping scores of people in a cycle of self-disbelief, limited opportunity and often poverty. The status quo of the colonial project stays unchanged.

So far, my examination of the works in Continental Drift has been a gender-neutral exercise, looking beyond the gender of both the artist and characters in a story to convey experiences aligned to cultural membership. However, even if the experience is shared between men and women, there are aspects of any event that are gender specific. Tony Albert’s wall installation, Eyes in the Sky 2018, and video work Moving Targets 2015, together present both shared and gendered stories.

Albert’s Eyes in the Sky is an assemblage of symbols that span different ideas. It includes shared and gendered experiences as it traverses different stories. For example, the presence of the Nike symbol signals Albert’s dislike of global branding, and his inclusion of the ‘British’ bunnies is a general comment on the rabbit as an introduced pest. The playing cards that depict landscapes symbolise the artist’s concept of time as pre-colonial and colonial states. For Tony they also symbolise the frontier violence that beset Aboriginal Traditional Owners. Albert expands on the latter subject using the Pacman motifs. In the electronic game Pacman, a circular entity moves around the maze chasing and eating ghosts. The ghosts try to flee. The bullets represent the Aboriginal men and women who went to war for Australia - men as soldiers and women as nurses.

Moving Targets 2015 is a wholly male experience. The video work is partly inspired by the shooting of two young Aboriginal men (one man died), by police officers at Kings Cross, Sydney in 2012. The video follows on from an earlier work, We can be heroes 2012, on the same subject. (Hagan 2012) The video work is a collaboration between Tony Albert and choreographer Stephen Page, and was directed by David Page, performed by dancer Beau Dean Riley Smith and filmed by James Marshall. The video is the film component of a larger multimedia installation of the same name that pays ‘homage to the vulnerability and strength of Aboriginal men’. (Sydney Contemporary 2018) The video work shows a contemporary dance. A bare-torsoed man in his prime awakens. With divine grace, he pulls himself up to his knees. It is at this point we see the red concentric circle in the middle of his chest. The circle is a symbolic target that ‘marks’ all Aboriginal men when they are born. By this I mean being born Aboriginal and male in Australia – which is even worse if they have dark skin. Aboriginal men and boys are automatically vulnerable to negative racial profiling and heightened public attention. This is a contemporary experience of colonisation in Australia, an experience that goes back to first settlement. Albert, however, lives with the target, noting that its existence does not have to hinder a man’s life experience. But he concedes many Aboriginal men learn to tread carefully.

A further example of gender-specific narratives is seen in Hannah Brontë’s hip-hop style video work, Still I Rise 2016 3 It features an all-female cast, led by Kunibidji woman Noni Eather as the fast-talking Prime Minister, with a deputy and a sisterhood of ministers that proudly serve in the portfolios of Indigenous Affairs, Women, Education and Defence. Brontë explains that this work was born from a great sense of optimism. She asks, ‘what if we did run our country?’ and ‘what if women were in power?’ (Brontë 2018)

It took Brontë some time to imagine this future. She notes that we, as Aboriginal people, are constantly busy with simply surviving, that looking past tomorrow is difficult – even a luxury. About this she is right. Many Aboriginal families struggle to have enough food, school books, rent money. But, in Brontë’s imagined future, having to survive to live would become a thing of the past. As the Honourable Minister for Indigenous Affairs raps, ‘You wanna see us in poverty, not how it’s gonna be, I’m the female embodiment of the change I wanna see’. (Brontë 2016) Brontë’s all-women government spells out a fabulous future, starting with correcting the problems we live with now.

Still I Rise 2016 enlists and demonstrates the power and efficacy of Aboriginal women today. In addition to being ’way-cool’, the women are

‘boss’ in their chic street-wear in hues of pink. Their clothes complement the pink and yellow design of the background that pulses in time with the beat, much like an optical illusion in binaural beat vimeos. Furthermore, in the video work, Brontë’s other art practices are present. For example, she explains that the ‘textile used on the costuming is made from MRI scans of my ovaries and microscopic imagery of my oestrogen cells, mixed with camouflage print’. Her interest in rap music and her DJ practice culminate in a brash and evocative statement about strength, gender equality and human rights. Furthermore, I think there is a deeper issue that her work addresses - the continuing culture of colonisation to disempower and keep the colonised powerless. I find this idea of colonisation as a culture, with its

system of relationships, power structures and institutions that work in unison very disturbing, and well worth changing. But first, as Brontë reminds us, ‘to achieve victory, we must envision it. This is what Still I Rise represents’. (Brontë 2018)

The beginning of British settlement for Aboriginal people is truly difficult to comprehend. It is said that many Aboriginal people throughout Australia believed the British were deceased relatives that had returned from the dead. Equally difficult to measure, or feel, is the emotional trauma Aboriginal people must have felt when the British forcibly made it clear they were here to stay. I suspect Aboriginal people, including photographer Michael Cook, attempt to imagine these events and feelings more than others. In his recent photo series Invasion 2017, Cook explores what these early experiences must have been like for our ancestors. (Cook 2018) There were many such experiences as the “Brits” (British) spread across the continent and Tasmania, marking “their” territory as they went.

Invasion is a highly considered series of photographs with much hope instilled in each image. Three of these photographs are exhibited in Continental Drift , and present as a mockumentary of the invasion of London, England. In scenes reminiscent of 1960s B-Grade films, people are screaming and running in all directions, trying to escape the alien invaders. The invaders take the form of giant kangaroos and lizards, flocks of birds, dark-skinned laser girls who fire lasers from their breasts, and a fleet of spaceships. Cook even created a mock tabloid sheet with ‘INVASION’ headlining the news of the day. In this work, Cook attempts to capture the shock and surrealism of this kind of experience. In an interview with Louise-Martin Chew, Cook explains, ‘I thought about Indigenous people and what they endured 250 [sic] years ago’…It was the first time they had seen… the kind of violence that saw people die beside them’. (Martin-Chew 2018) Across the photos, Cook tries to convey that the entire experience of colonisation, the event, from the mundane to profane,

would have been completely shocking, similar to that of a UFO attack today. Cook’s key motivation was to create empathy for what Aboriginal people experienced.

Contemporary Aboriginal responses to the ongoing influence of colonisation are varied - not only do they highlight the trauma tic legacies of colonisation, but they also emphasise the strength and will of Aboriginal people to live in spite of them. Hannah Brontë envisions an alternate future and so does Michael Cook. Gordon Hookey’s sharp, humorous visual barbs make known that equality should be for all. Tony Albert reveals the prejud ice inflicted on Aboriginal men. Archie Moore highlights the power of words to oppress. By holding a mirror up to these maleficent legacies we can correct them.

Aboriginal Australia has many supporters beyond its own community. Exhibitions like Continental Drift often only speak to the converted. To generalise, non-supporters tend to believe that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are in a position of their own making, and that the past has no bearing on today. Therefore, Aboriginal people should ’get over it’. With some explanation, and luck, people like this might change their position. But, actually, there is a third group of Australians who can benefit from ‘art history’. These people are not automatically opposed to reconciliation and are willing to bridge the social divide. Through engaging with issues raised by exhibitions such as Continental Drift, they can explore Aboriginal perspectives and experiences of colonisation in a safe learning environment. With the right kind of access to information, this group of exhibition visitors can openly absorb and appreciate new information of which they were previously unaware. This could lead to a larger swell of people who are willing to consider and recast a different future, separate and away from the colonial present we live in now.

Continental Drift makes clear that colonisation is not only an event that occurred 230 years ago. Rather, colonisation is a very real and pressing contemporary experience for those on the wrong side of it - the colonised. Aboriginal people live with the trauma of colonisation in various and subtle ways. This is a wrong that needs fixing. Conversations about colonisation go some way toward fixing this, but Australian society must go further if we are to be an inclusive society.

To quote Aime Cesaire:

Colonization… dehumanises even the most civilized man; that colonial activity, colonial enterprise, colonial conquest, which is based on contempt for the native and justified by that contempt, inevitably tends to change him who undertakes it; that the colonizer, who in order to ease his conscience gets into the habit of seeing the other man as an animal, accustoms himself to treating him like an animal, and tends objectively to transform himself into an animal. (Cesaire 1993, p. 177)

Bong, P 2018, Memories of Oblivion: 1–5 Artist statement.

Brontë, H 2016, Still I Rise.

Brontë, H 2018, Re: FW: Brontë, C Lane.

Cesaire, A 1993, ‘From discourse on colonialism’, in Colonialdiscourseandpost-colonial theory:Areader, eds P Williams & L Chrisman, Harvester Wheatsheaf, Sydney, pp. 172–181[2007.02.05].

Cook, M 2018, Michael Cook: Invasion, Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane.

Crawford, P & University of Western Australia. 1983, WomeninWesternAustralianhistory, University of Western Australia Press, [Nedlands, W.A.].

Croft, B. L 1993, ‘Blak lik mi’, in Art and Australia, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 6367.

Delbridge, A & Bernard, J (eds) 1998, The MacquarieConciseDictionary, 3rd edn, The Macquarie Library, New South Wales.

Evans, R 2007, AHistoryofQueensland, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge ; New York.

Fitzgerald, R 1982, FromtheDreamingto1915:aHistoryofQueensland, University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia [Qld.].

Foley, F 2017, FionaFoley:Horrorhasaface, Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane.

Goddard, A 2018, ‘Archie Moore: Memory descriptions’, in Archie Moore: 1970–2018, eds L Michael & H Eriksen, Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane, pp. 10–21.

Hagan, S, ‘King’s cross shooting triggers winning entry’, FirstNationsTelegraph. Available from: <https://issuu.com/first_nations_telegraph/docs/king_s_cross_shooting_triggers_wi>. [23 May 2018].

Harding, D 2018, Re: A chit chat?, C Lane. Hookey, G 2018, Telephoneconversation,24May2018, C Lane.

Martin-Chew, L 2017, FionaFoleydiscusseshernewseriesHorrorhasaface in Art Guide Australia, pp. 1–13.

Martin-Chew, L 2018, MichaelCooktalksaboutstaginganIndigenousinvasionofLondon in Art Guide Australia, pp. 1–6.

Mundine, D 2008, ‘Gordon Hookey’, in WesternAustralianIndigenousArtAwards, ed. C Lane, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, pp. 22–23.

Mundine, D 2018, Archie Moore: 1970–2018 in Artlink, pp. 1–21. Perkins, H 2010 art+soul:AjourneyintotheworldofAboriginalart, Miegunah, Melbourne. Reid, GS 1981, Anestofhornets:ThemassacreoftheFraserfamilyatHornet Bank Station, Central Queensland 1857 and related events, Masters thesis, National University. Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, DestinyDeacon:Artistprofile. Available from: <http://www.roslynoxley9. com.au/artists/2/Destiny_Deacon/profile/>. [24 May 2018].

C.D. Rowley, CD 1972, TheDestructionofAboriginalSociety, Penguin Books Australia, Ringwood, Vic.

Sydney Contemporary, TonyAlbertandStephenPage,MovingTargets, 2015, Sydney Contemporary. Available from: <https://sydneycontemporary.com.au/tony-albert-and-stephenpage-moving-target-2015/>. [23 May 2018].

1

The concept was inspired by the title of a publication published by the Art Gallery of Western Australia – Keepers of the Secrets: Aboriginal art from Arnhem Land (1991).

2

Bigunu are carved from the buttress roots of the native fig tree.

3

Still I Rise was commissioned for the Next Wave Festival, 2016.

M. Neelika Jayawardane

South Africa is a location that has been passionately theorised and conceptualised as an idealised landscape, one that represents European settlers’ longings for a “homespace”. However, it is also a nation that “un-homed” millions over several centuries of colonial and white supremacist rule. It is a place where colonial, settler, and white-minority-elected administrations made systematic, concentrated efforts to erase or completely marginalise its existing indigenous and black populations using genocide, forced removals, and socio-economic and legal structures intended to exclude and dehumanise. To the majority of its black population, this “homespace” remains a place of profound alienation and unbelonging.

Berni Searle, Mary Sibande, Zanele Muholi, Kudzanai Chiurai, Athi-Patra Ruga, Mohau Modisakeng and Buhlebezwe Siwani use aesthetic methodologies to theorise what happens when people have been violently “un-homed” and repetitively reminded of their otherness. They meditate on the ways in which apartheid strictures controlled, directed, and distorted black people’s bodies, intellects and sexualities; they reveal the ways in which people’s cultural and spiritual practices, and relationship to their environments were erroneously represented, and how those misrepresentations continue to impose themselves on their day-to-day lives.

However, contemporary black South African artists’ practices not only provide them with methodologies for mourning, they also present them with innovative ways to creatively theorise the impact of Southern Africa’s socio-political history on their bodies and psyches. Their work allows them to create new avenues of re-entry and return, and to reconstruct personhood – in power, rather than as supplicants. Through acknowledging the ruptures produced by this

region’s violent history, they are able to speculate about alternative possibilities, and address the necessity of making radical breaks from existing cultural norms and expectations. This extraordinary gift – freedom from previously accepted constraints, and the ability to self-fashion, to forge one’s own set of boundaries and direct the course of one’s life –are the unintended consequence of a society that continues to live with experiences of repressive and violent social conditions.

Appropriate for such a groundbreaking exhibition, Buhlebezwe Siwani’s Imfazwe yenkaba (war of the womb or belly) (2015) is a ritual of renewal. It is an invitation to the ancestors – to welcome them back after a long hiatus so that they are “aware of what is happening on their land,” as Siwani says – and to ask for their blessing. The video was shot in the Eastern Cape Province, in Tamara – some 30km southeast of King Williams Town on rural roads, where Siwani’s family comes from. Siwani, who was trained and initiated as a sangoma – a healer – has always positioned her practice as an artist as essential to her spiritual practice, and vice versa.

During this ritual, Siwani is wearing a skirt, especially made to suit her body, with a golden clasp at the back. She is walking towards the kraal, the central place where communal life happens, where the cattle are kept at night, and where the ancestors were once buried, and where all rituals took place. The skirt she is wearing has special significance. Young men typically wear it during their initiation, a process that takes place in sacred, sequestered locations in the bush. The process of conceptualising this renewed ritual began when a male relative who passed away left his own initiation skirt to her. In addition, she wears a contemporary version of this skirt because “most of the ancestors who I work with [in my spiritual practice] are male,” she says.

Siwani is wilfully engaging in a necessary act of transgression – a rearranging of accepted gendered norms. During their initiation period, the boys, supervised by elders, engage in staged dances called Amakwetha. Boys are also taught how to honour the ancestors, proper etiquette as men, and that their position as men gives them liberties that women will not have. Siwani emphasises, “He is told that he has to try his penis on multiple girls before he finds the right one.” It became important for her to question these accepted notions of what constitutes “honour” for a woman and for a man.

There’s a saying, ‘Inkomo zikaTata’ – your father’s cows, or his wealth and honour, rest within your vagina; if you’ve slept with everyone, the cows will not come home, so to speak. But I think, whether these cows come home or not, I must protect my own sense of honour. And anyway why must a man test his penis out, and I am not considered virtuous if I also test out my vagina? 1

IMAGE PAGE 33

Zanele MUHOLI

Nomthandazo,Orani,Sardinia,Italy 2015 silver gelatin print

50 x 24.32 cm

Courtesy of the artist and STEVENSON, Cape Town/Johannesburg, South Africa

IMAGE PAGE 35

Buhlebezwe SIWANI

Imfazweyenkaba 2015

single channel video, sound

5:10 mins

Courtesy of the artist and WHATIFTHEWORLD, Cape Town, South Africa

IMAGE PAGE 36

Buhlebezwe SIWANI

Ziyayokozela 2017 single channel video

10:45 mins

Collection of the artist

Courtesy of the artist and WHATIFTHEWORLD, Cape Town, South Africa

The ordinary revolution she orchestrates is no different from those that women all over the world – long prevented from having access to ritualised labour that was reserved for men – have also consciously carried out. With a seemingly simple change in costume, she demythologises – like the Rosie-Riveters, soldiers, footballers and healers long before her – the mystique of male privilege and ownership of uniforms that signal their legitimacy in privileged fields. She illustrates, powerfully, that there is no magical barrier that prevents women from doing both the ordinary and extraordinary.

Ziyayokozela (2017) is a record of a different ritual. It is particularly focused on “returning” the troubled spirits of those who perished in the SS Mendi, which sank off the coast of the Isle of Wight in February 1917, when the cargo ship Darro accidentally rammed Mendi’s starboard quarter. It resulted in the deaths of 646 people, the majority of whom were black South African men from The South African Native Labour Corps. In this Siwani wanted to ensure that it was “…women who were primarily participating in this ritual, because, of course, the men whose lives were lost…they left women behind. I wanted to think about what it meant to reunite them in the water, to heal with water, and to dissolve our bodies into the water.”

Kudzanai Chiurai, who uses photography, performance, archival images and other historical documents, playfully reconstructs and critiques colonial cultural narratives in his series, Genesis (2016). He begins by referencing colonial archives – from which black people’s experiences are largely excised, or presented in a manner intended solely to aid the colonial project. He then reconstructs (absent) black histories, subversively inserting black “actors” and agents into his performative re-enactments of history.

The works, shot in Cape Town, explore the roles played by Christian missionaries and the church in opening the way for imperial violence in Africa. In identifying the integral role Christianity played in colonisation, as well as the ways in which European notions of “civilisation” were tied to commercial ventures, Chiurai teases out early Victorian understandings Britain had about its mission in the world. At the time, there was a providentialist certainty in what missionaries imagined was their divine purpose – to propagate Christianity, as well as to further trade. According to historians, that relationship between “commerce and Christianity” was widely believed at the time.2 During his Cambridge lectures, given in December 1857, David Livingstone, a missionary and explorer, also infamously articulated this relationship as the cause for his next mission: “I go back to Africa,” he said, “to make an open path for commerce and Christianity.”3

Chiurai remembers that what piqued his interest was a “really interesting publication about Livingstone; it contained the testimonies of those who went with him, bearing testament to what he did.”4 He then visited the Livingstone Memorial Church, and the David Livingstone Centre in Blantyre, Scotland (Livingstone’s birthplace). He was particularly taken by some stone reliefs made to commemorate Livingstone’s expeditions. The reliefs show Livingstone in various poses: in one, he is seated under the shelter of an open hut structure, reading the bible to enraptured “natives”, all of whom are clearly positioned as pre-modern, wearing minimal clothing, seated outside the shelter of the hut’s thatch.

Chiurai says that it was “through reading Livingstone’s companions’ testimonies and seeing the stone reliefs, particularly the one “about the ‘converted’” – as well as an abundance of archival images staged to invent the African as ridiculously “other” for European consumption – that he began to conceptualise what he wanted to do in the Genesis series. He also realised, that despite the fact that many of the societies into which Livingstone journeyed were matrilineal –with women in positions of authority – all of the narratives that he read “referenced some male authority – a chief”. That got him thinking about how narratives about Africa are re-tooled and re-invented to fit European frameworks of patriarchy and social norms. In his own performative stills, he re-positions these “encounters” to reflect a more realistic history, where “Livingstone” negotiates with a woman. The iconography of supplication, and the European’s inherent superiority, are markedly absent.

Around the same time that Chiurai researched Livingstone, he also came across a photograph, titled, A Zulu Dinner Party (circa 1905) in Cape Town.5 It was a studio photograph of a constructed scene, replete with a group of costumed “natives” sitting in a semi-circle around a three-legged iron potjie, with what looks like pieces of unidentified food in their hands. Oddly, though there is a pot in front of them – one that would have, just before this supposed repast began, sat over a fire – a furry, living room rug also lies at their feet. The fact that this was shot at Budrick’s Art Galleries on

Adderly Street in Cape Town – where “Zulu” people were not known to frequent – betray the fact that this was obviously a staged photoshoot. Like hundreds of other images intended for the postcard trade, this bit of theatre – created by a white photographer in his studio – was meant to project and perpetuate the existence of a backward, picturesque native who stood still in time and space, unable and unwilling to be a part of the capitalist modernity that white Europeans enjoyed.

This “dinner party” of supposed Zulus has a recurring role in the wallpaper that Chiurai often employs. In the background, the wallpaper has Cecil Rhodes’ face – framed in an oval cameo and the three roses reminiscent of Three Roses English tea packets – on repeat, over a map of the vast territory Rhodes wished to conquer. In the foreground, layered over this repeated motif, is the scene from the Zulu Dinner Party. Their gazes – blurred by distance, time, and the veil of colonial positioning – are mostly inscrutable. Yet their presence is always present, as if to remind black South Africans that no matter how much they try to don the customs, clothing, the politics and poetics of whatever Europeans consider “civilised”, they remain seen through the same old lens. They remain the backward “natives” in that postcard, objects of curiosity and pity, the impetus behind great European expeditions, and so devoid of basic tools that all their attempted imitations of European practices fall ridiculously short.

IMAGE RIGHT

Mary SIBANDE

CaughtintheRapture 2009

digital print

90 x 60 cm

Collection of the artist

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Gallery MOMO, Cape Town/Johannesburg, South Africa

IMAGE INLEAF

Mary SIBANDE

I Decline. I refuse to Recline 2010

mixed media

180 x 193 x 250 cm Collection of the artist Courtesy of the artist and Gallery

South Africa

between madams and maids – created, supported, and maintained by colonial and apartheid structures – remains central to visualising and experiencing the ways in which unbearable social relations continue to be made normative and acceptable in the sequestered, privileged realm of family and household, largely out of view. Because of the private nature of this relationship, as well as the shame associated with exploiting those labouring in one’s domestic spaces, the troubling aspects of this relationship are usually made invisible.

Mary Sibande’s Work series similarly signals the ways in which the “old” colonial practices and relations in South Africa haunt the present. Through many iterations of “Sophie”, as she calls her uniformed, aproned figures, Sibande explores domestic workers’ inner lives. The Sophie sculptures are made to human scale and moulded using Sibande’s own proportions; they are thus “genomic avatars” or performative alter egos.6 She is always cast in a highly polished black plaster. Her face: blank impassivity. Her body: a monumental mystery under a great half sphere of Victorian dress. Her costume is stripped of decoration, and the apron is bleached so white that it reminds one of a Hollywood starlet’s teeth. For those in South Africa, it is instantly recognisable as a maid’s uniform. But in each incarnation, Sophie’s uniform has been hybridised with versions of voluminous Victorian costume. The folds of a bustle accentuate her bottom in one, a Carolina’s frame emphasises her waist in another, and an enormous train signifies her ceremonial significance in a third. Wherever she appears, Sophie presides over the floor space, doling out equal degrees of comforting familiarity and blue terror.

To recognise Sophie’s significance, we must, first understand the complex relationship between labourers (“maids”) and employers (“madams”) in South Africa. Du Plessis et al. argue that its historical roots are in colonial era spaces; that history became a central feature of “the apartheid social imaginary.”7 The location of encounter

This history of black women’s servitude – signifying their erasure from history, as well as rare possibilities of agency – informs Sibande’s sculpture-making. Although the images of the Sophies’ faces and bodies suggest uniformity and invisibility, their imposing size, and the girth of their voluminous blue dresses declare something converse to disempowerment: they are here, immovable against all assault, immobile against any attempt to remove them from being present in our collective consciousness.

Sophie is partly embedded in Sibande’s family history: she is an amalgamation of several generations of women in Sibande’s family who worked as “domestics” with little recourse for changing their economic circumstances, who, nonetheless, found ways to transport themselves out of those constraining conditions. Sibande also stresses that rather than Sophie being a direct “representation” of her female family members, the sculpture “encompasses desire and aspiration”; as a representation of aspiration, “Sophie’s most powerful gift is her ability to dream. She goes to work wearing her maid’s uniform. But then she closes her eyes and starts to imagine things…”8

In some iterations of Sophie, she is only able to acknowledge, to herself, the exhaustion and despair she feels during the liminal moment between her two primary modes of service: the interminable wait for the bus that takes her from her labour in her madam’s wealthy, white neighbourhood to the domestic duties waiting for her in her own home.

Achille Mbembe has noted that it is through “dreaming” that those in labouring positions may – in invisible, yet subversive and powerful ways – contest their objecthood, despite the confining structures that help construct and maintain them as labouring-objects.9 But dreaming may not be the only possibility through which Sophie – reduced as she is to an instrumentalised position of a labouring-thing – can return to her personhood. At times, she rears up, completely undomesticated, liberating herself from the constraints set by madam and neo-apartheid.

Zanele Muholi’s series of performative selfportraits, titled Somnyama Ngonyama – meaning ‘Hail, the Dark Lioness’ in Muholi’s first language, isiZulu – are illustrative of the deep fractures racism produces in our psyches. Muholi’s selfportraits are a departure from her previous work as a “visual activist”, and her portrait series titled Faces and Phases – which she began creating back in 2006 – commemorating and celebrating the lives of the black gay, lesbian and transgender people she met on her journeys throughout her home country. This activism, and the constant travel it requires, left little time for self-reflection, or space to think about the damage on her own psyche as she absorbed the stories that each of her participants related.

The series began as way to deal with ordinary and extraordinary instances of racism that Muholi encountered while she was at Civitella Ranieri in Umbria, Italy, for an artist’s residency in 2012. She began documenting herself, every day; in so doing, she took on the most difficult journey – an introspective record of her own person that gave her an opportunity to get to know her own faces, so that she would not feel so empty – nor so full, perhaps, of others’ poisonous projections. Selfportraiture offered her an outlet to nourish herself with ironic laughter, while defining herself on her own terms.

In each of her self portraits, Muholi purposefully heightens the contrast, emphasising as high a glossy darkness to her skin as the silver gelatin technology will permit. She does not achieve this “blackface” – this mask – using paint, as did racist caricatures that remain troublingly persistent today. But like the paint used in constructing blackface, the various props Muholi employs –from metal scouring pads to take-out Chinese chopsticks, blobs and streaks of face paint and hair weaves – also signal stereotypical and racist constructs of blackness. They reinforce the notion that this is a mask that we are seeing, and that these are various roles she inhabits.

Each “Zanele” reflects back to us – her audiences – that it is we who carry these ideologies, and that it is we who are responsible for projecting these caricatures onto black people. In playing with mock props and skin shade in order to emphasise a sort of “performative blackness”, Muholi gamely references stereotypical notions that continue to be imposed on black and African bodies. She also reflects on the ways in which these preconceived notions stamp themselves on the psyches of black people, so much so that they absorb and follow these views as though they are instruction manuals. They reproduce their injurious messages, despite the obvious damage they do to their physical and mental health, and to their relationships with each other.

Somnyama Ngonyama is also a performative conversation with apartheid’s racist machinery, and its use of photographic technologies to dehumanise and restrict black South Africans. For instance, during the 1950s, South Africa’s “pass laws” – which helped formalise apartheid policies by requiring that all black persons over the age of 16 carry a “reference book”, a “pass” – were aided by new photographic technologies designed to produce an instant image. Polaroid’s ID-2 camera, with its “boost” button to increase the strength of the flash – supposedly allowing it to better photograph dark-skinned people – was the chosen technology for photos used in dompasses 10 as passbooks came to be known. Inevitably, the photograph within a dompass often projected a two-dimensional caricature.

Muholi’s self-portraiture, I argue, is a way to dialogue with that history, and to challenge the ways in which photography was instrumental to the creation of black identity in South Africa: as a fixed, flat and stultified identity. These are her responses, often tragi-comical, to the constraining narratives of history and the effects of that history on her present. Through the release that (nervous) laughter provides, Muholi facilitates our passage towards a necessary, difficult dialogue.

However, in many of the portraits, her gaze “roars” through the two dimensions of the photograph. Once we have walked into that room housing her experiences, we have to face the weight of what she must live with every day. While we are here only for as long as we are willing to engage, we know that this is a room in which she remains locked, stamped by the weight of the social, political and personal complexities that her body and her psyche cannot escape.

IMAGE PAGE 46

Zanele MUHOLI

MaID,Brooklyn,NewYork 2015

silver gelatin print

30 x 21.74 cm

Courtesy of the artist and STEVENSON, Cape Town/Johannesburg, South Africa

IMAGE LEFT

Zanele MUHOLI

Khwezi,Songhai,PortoNovo,Benin 2015

silver gelatin print

50 x 34 cm

Courtesy of the artist and STEVENSON, Cape Town/Johannesburg, South Africa

Similarly, Mohau Modisakeng’s Inzilo (widowhood, in Zulu) is a performance that highlights the impossibility of peeling away the effects of racism on one’s skin and on one’s body. In the film, we see the artist attempting to peel off a layer of a thick, black coating that covers the skin of this hands and feet. It is a slow, and meticulous process. Though he is successful in discarding this rough, horny coating, the rims of his fingernails remain stained by the pigment; it is a greasy, clinging blackness projected on to him, impossible to remove completely, so that there is no trace left on the body. When he finally stands up with a flourish, the bits of “skin” he peels off scatter in a cloud around him, and settle in a mess on the floor.

Modisakeng says that as he was growing up in Soweto, during the early 1990s, there were violent clashes between those affiliated to rival political parties, particularly the African National Congress and Inkatha Freedom Party. The staccato sound of AK-47s and the burn of teargas were not uncommon. Much of the violence was underhandedly stoked by so-called third forces – shadowy figures employed by the apartheid National Party – in order to create fear about an impending dystopia under black rule; however, at the time, it was not clear that the machinery of apartheid was behind much of this violence. Modisakeng, who was born in 1986, just remembers “seeing people who had just been killed, their bodies still in the street. Death was part of my every day.”11 And death arrived at his home, too; the older brother, Sthembiso – who cared for him whilst his mother worked as a nurse in the city of Johannesburg, and his father at a local school –was killed. He still remembers the image of his mother holding a white sweater that belonged to his brother –now with a small hole, and a russet stain around it. After that moment, nothing about this death was spoken in his home.

In Inzilo, Modisakeng works with the idea of being in a transitional process of mourning, of having to face starting over. He references widowhood, to begin to think about mourning as a private and personal process,

but by re-enacting the process in the public domain, he links the ritual of mourning with the history of South Africa – which includes the history of blackness, and the history of violence. Mourning, he says, is an “… ambiguous transitional process…that takes between 6 – 12 months. You are stuck with it, and there are no real ‘results’; it’s just a process that you have to go through.”12 He points out, “If you think about what South Africa has been through in the past 20–plus years, it has been stuck in this transitional process, and we cannot imagine to what end.”

Modisakeng notes, about the marked presence of palpable violence, the weight of death, and the atmosphere of mourning in his work, that they are “… filtered through my own memories and emotions.”

As such, his artistic practice continues to draw from his own experiences of loss and trauma. As an artist, he is interested in the history of South Africa, and of the impact of violence and trauma on black people’s bodies and psyches. Much of that violence, and its long lasting, intergenerational effects have not been dealt with, he argues. Although the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, for instance, attempted to have a public catharsis, it achieved little but to position black South Africans as repositories of a special brand of forgiveness, and as people with a magical ability to grant absolution. That “magic” was expected to be trotted out every time a white person “confessed”, with little expectation for justice or reparation.

Though unacknowledged, supressed, and swept away – partly because of the necessity of survival, partly because there were no feasible avenues for expressing that grief and anger, and partly owing to pressures from political leadership to put on a happy face and choose celebratory narratives – that violence remains under the surface. In referencing dominant, white supremacist narratives that continue to impact black South Africans’ relationship with their skin, their bodies, their subjectivities, Modisakeng does not pretend to minimise history’s impact. Yet there is something beautiful, unapologetically powerful, about the black aesthetics in Modisakeng’s works.

PAGE 48

MODISAKENG

xv 2014

the Ditaloa series, 2014

inkjet print on Epson UltraSmooth

200 x 150 cm

of the artist and WHATIFTHEWORLD, Cape Town, South Africa

IMAGE LEFT

Mohau MODISAKENG

Inzilo 2014

single video, sound, 4:56 mins

Courtesy of the artist and WHATIFTHEWORLD, Cape Town, South Africa

Berni Searle’s works may be seen as spectral hauntings, as unresolved business that refuses to be ameliorated or suppressed. Black smoke rising (20092010) prompts us to recognise the spectre of violence in post-apartheid South Africa, against the backdrop of an idealised, idyllic landscape. Lull begins with a lush scene – a riverbank with overgrown greenery, and the honking sounds of geese and other birdsong. Trees, too, are lined up to drink deeply from this abundance. A woman – with her back to us – swings slowly in the foreground of this scene, on a swing made from a cut tyre; presumably, it is hung from one of the tree branches. She is humming gently to herself, looking out at the river. But after a short while, she stops swinging, and gets up to walk towards the riverbank. The swing keeps lilting a little, and we hear her humming continue for a brief period, as white water birds – egrets, perhaps – fly by lazily, scanning the river.

The artist and cultural critic Sharlene Khan reminds us that the “picturesque and the idyllic as represented in landscape art…are veneers which hide scenes of grotesque violence and inequalities.”13 Searle’s work begins by referencing that idealised imagery, but then, it brings all the unspoken violence – that which is intended to remain out of the frame – to the foreground, shocking us out of our idyll. In the space of a few seconds, the swing fades away. Then, just as suddenly, we hear the crackling noises of fire. In the next instant, a burning tyre replaces the swing; it

Gateway 2010

Lull 2009

series 2009 -2010

sways violently, back and forth, spewing grey smoke. We observe the tyre as it slowly comes to rest, and burns to its end; the smoke then becomes thicker, and pitch black. We can almost smell the acrid rubber burning, and the petroleum fumes. Finally, the tyre falls off the rope, out of our view, but continues to burn. Through gaps in the smoke, we can see that the river – and whatever life might be happening on the opposite bank – continues to flow, as though nothing of the fire burning on this side has infringed on its ordinary movement.

In South Africa’s recent history, the burning tyre is a visceral reminder of the possibility of erupting violence. It is associated with townships on fire; residents used to pile up entrance roads with tyres and set them alight to prevent Casspirs – the tanks that the South African Defence Force used. And who can forget – of all the spectacular images journalists captured during the 1980s – “necklacing”? It was the punishment meted out to those suspected of being impipis (informants to the apartheid state police): a tyre was filled with petrol, forced around the chest and arms of the victim and set on fire. A crowd – and there was always a crowd – would gather to watch. A journalist would have a camera rolling. And so, through those disseminated images, a whole world watched. From their armchairs, they imagined that the fire and smoke would never touch them, or spread to the safe locations from which they watched.

Like Modisakeng, Searle reminds us that, despite the euphoria of the decade immediately following the country’s first democratic elections, violence remains ever-present, swinging lazily like a tyre on a rope, about to set fire to our idyll.

Athi-Patra Ruga’s The purge (2013) and The Future White Woman of Azania (2012) reveal the ways in which white women are positioned as precious, coddled objects of desire within patriarchal and white supremacist societies. However, they are also precarious and fragile repositories of the woundedness of such societies – carrying poison and infectious pus that can only be released through violent, messy ruptures. Ruga says, in the introduction to this work, “The Future White Woman of Azania is a character made up of liquid paint filled balloons…I wanted the action to revolve around two acts: that of engaging in the catharsis of walking and that of ‘weeping’ – a purging that here is represented by the popping.”14

In The Future White Women of Azania is also about the process of getting to a utopian ideal – the utopian fiction of Azania, which was a homegrown, decolonialised version of arcadia. Azania seemed more achievable back when the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), in 1965, appropriated the Greek

term to signify an idealised possibility for South Africa. However, this ideal – once so promisingly within reach – seems far less achievable as South Africa passed twenty years of “democratic” rule.

In the stills, Ruga’s “future white woman” walks through a dusty, unpaved township street on enormous stripperheels, as locals and children stand aside and gape at this fantastical figure. In some ways, this figure signals the power of a powerful, white version of femininity even (and especially) in marginalised spaces to which black people have been relegated. The colourful balloons that cover her “real” body and face, masking form and expression, bob in obeisance to the load it carries –often unquestioningly and uncritically. She is a flouncing spectacle – unable to see where she is walking, at once childish and overtly sexual – from which we cannot avert our eyes.

In The purge, Ruga’s balloons rupture, releasing a viscous liquid akin to pus. This rupturing creates feelings of aversion and fascination at the same time. The rupturing of these bulbous blisters also seems to communicate that this toxic form of femininity – which aids and benefits from the power and violence of white masculinity whilst hiding behind it – does have a chance to heal. It tells us that the racialised and gendered identities to which we have slavishly devoted ourselves must release their poison before we can get to the Promised Land. Until then, the “future white woman”

will remain in profound pain, directing all the conscious energy she can muster into the balancing act that white supremacy requires of its female representatives.

Cairns Art Gallery’s exhibition allows us to consider the remarkable possibilities produced by South Africa’s history. The artworks are radical departures from what we might be used to in works that explore colonialism, apartheid, and the politics of race. They move away from simply accepting or lamenting the effects of racism; instead, they broadcast powerful black subjectivities that not only return the gaze, but sometimes have no interest in engaging with or attempting to correct racist gazes. This is an exhibition that will force audiences to acknowledge their complicity in racism, but also call on them to move beyond defensiveness, shame, and silencing as the only responses to a troubling past –and, instead, to forge new passages towards accepting responsibility.

1

Interview with Jayawardane. 25 April, 2018.

2 Stanley, Brian. “‘Commerce and Christianity’: Providence Theory, the Missionary Movement, and the Imperialism of Free Trade, 1842-1860.” The Historical Journal, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Mar., 1983), pp. 71-94.

3 W. Monk, (ed.). Dr. Livingstone’s Cambridge Lectures 1860, p.24.

4 Interview with Jayawardane. 26 April 2018.

5 “Zulu Dinner Party”. Shot at Budrick’s Art Galleries on Adderly Street in Cape Town.

5 https://www.delcampe.com/en_GB/collections/ item/259429865.html.

6 Bidouzo-Coudray, Joyce. “Mary Sibande: Triumph Over Prejudice.” Dec 13, 2013. Art & Culture, http://www. anotherafrica.net/art-culture/mary-sibande-triumph-overprejudice [accessed 23 June 2014].

7 du Plessis, Irma. “Nation, Family, Intimacy: The Domain of the Domestic in the Social Imaginary.” South African Review of Sociology. 42: 2. 2011, p. 46.

8 Wellershaus, Elizabeth. “Sophie is Not the Only Strong Woman Populating Our Art Scene at the Moment.” http://www.contemporaryand.com/blog/magazines/ sophieis-not-the-only-strong-woman-populating-our-artscene-at-the-moment/ [accessed 23 June 2014].

9

Mbembe, Achille. “Raceless Futures in Critical Black Thought.” Johannesburg Workshop in Theory and Criticism (JWTC). 30 June, 2014. http://wiser.wits.ac.za/ event/raceless-futures-critical-black-thought.

10

Passbooks were derisively referred to as dompass (dumb passes).

11

Seymour, Tom. “Mohau Modisakeng: Memories of a murder.” Financial Times. September 27, 2016. https://www.ft.com/content/2ff46368-4f2e-11e6-8172e39ecd3b86fc.

12

Mohau Modisakeng, in conversation with Thembinkosi Goniwe. “Inzilo”. FNB Joburg Art Fair. Feb 13, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4bwAQ7PRO_Y.

13

Khan, Sharlene. “Black smoke rising: Under the influence of … Berni Searle’s video ‘Lull’”. The Conversation. November 27, 2016. https:// theconversation.com/black-smoke-rising-under-theinfluence-of-berni-searles-video-lull-68599.

14

“Future White Women of Azania.” Vimeo. https://vimeo. com/73056807.

Tony ALBERT

Girramay, Yidinji and Kuku-Yalanji peoples

Born Townsville, North Queensland, 1981

Movingtargets 2015 video, sound, 6:35 mins

Courtesy of the artist and Sullivan + Strumpf, Sydney, New South Wales

Photograph: Alex Wisser

EyesintheSky 2018

vintage playing cards, coasters and matchboxes on board

150 x 200 cm

Collection: Cairns Art Gallery, commisioned and donated through the Cairns Art Gallery Foundation, 2018.

Photograph: Simon Hewson

Paul BONG

Yidinji people

Born Cairns, Queensland, 1963

Memories of Oblivion 1 (50,000yearsofpeace) 2018 etching, ed. 1/25

120 x 70 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Photograph: Michael Marzik

Memories of Oblivion 2 (Invasionday1770/1788) 2018 etching, ed. 1/25

120 x 70 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Photograph: Michael Marzik

Memories of Oblivion 3 (Cuttingtheheadoff1877) 2018 etching, ed. 1/25

120 x 70 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Photograph: Michael Marzik

The list of works includes all works from the exhibition CONTINENTAL DRIFT:black/blakartfromSouth Africa and North Australia

Works are listed in the order of artist surname.

All work dimensions are height x width in centimetres.

Cataloguing conventions of lending institutions have been adopted.

Hannah BRONTË

Wakka wakka / Yaegel peoples

Born Brisbane, Queensland, 1991

Memories of Oblivion 4

(Cuttingoffthefeet1900) 2018 etching, ed. 1/25

120 x 70 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Photograph: Michael Marzik

Memories of Oblivion 5

(Theheartwillliveon2000/2016) 2018 etching, ed. 1/25

120 x 70 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Photograph: Michael Marzik

Still I Rise 2015

single channel video, sound 3:52 mins

Courtesy of the artist

Michael COOK

Bidjara people

Born Brisbane, Queensland, 1968

All works from the Invasion series 2017

Invasion(EveningStandard) 2017

61 x 74 cm

Collection of Phil Brown and Sandra McLean, Brisbane, Queensland

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

Michael COOK

Bidjara people

Born Brisbane, Queensland, 1968

All works from the Invasion series 2017

Invasion(Possums) 2017

inkjet print (TP 1)

135 x 200 cm

Collection of Tony Denholder and Scott Gibson, Brisbane, Queensland

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

Invasion(Lasergirls) 2017

inkjet print (TP 1)

135 x 200 cm

Collection of Tony Denholder and Scott Gibson, Brisbane, Queensland

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

Invasion(Finale) 2017

inkjet print (TP 1)

135 x 200 cm

Collection of Tony Denholder and Scott Gibson, Brisbane, Queensland

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

Fiona FOLEY

Badtjala people

Born Maryborough, Queensland, 1964

All works from the Horror has a face series

Badtjalawarrior 2017

60 x 45 cm

digital print

Collection of Paul and Louise Greenfield, Brisbane, Queensland

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

Protector’scamp 2017

digital print

40 x 80 cm

Collection of International Education Services, Brisbane, Queensland

Image: Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

Smoulderingpride 2017