alick tipoti

Zugubal: ancestral spirits CAIRNS REGIONAL GALLERY

EXHIBITION DATES 10 JULY - 6 SEPTEMBER 2015

SALLY BUTLER, (ED.) 2015.

This exhibition of Alick Tipoti’s art, Zugubal:AncestorSpirits, profiles selected pieces of the artist’s new work against signature pieces from his longstanding art practice. It is the artist’s first solo exhibition at a public gallery and the first exhibition of contemporary Torres Strait Island (TSI) art to pay heed to the region’s significant rock art and the role it plays in inspiring contemporary artists. TSI artists of today connect with their ancestors through creative expressions that translate ancient cosmology into visual stories. These retold stories from the past provide frameworks for TSI perspectives of natural, spiritual, and moral order in the present. Tipoti has been a leading figure in the contemporary TSI art movement since its inception in the mid1990s and remains at the forefront of innovation and diversification in the field.

The inception of Cairns Regional Gallery in 1995 coincided with the emergence of the contemporary Indigenous art movement in North Queensland. The Gallery has partnered with artists and supported their experimentation and developmental work, and led the way in providing formal recognition for outstanding achievements through exhibitions and public engagement initiatives. In recent years, and as leading artists emerge, the Gallery has taken stock of their artistic journey through solo exhibitions that delve into particular themes and aesthetic trends. This exhibition of Alick Tipoti’s art follows on from recent solo exhibitions profiling fellow TSI artists, Janet Fieldhouse and Ken Thaiday Senior, and Aboriginal artists from the region, including Roy McIvor.

Artworks in this exhibition include some of the finest examples of TSI’s unique linocut printmaking, along with new sculptural pieces that Tipoti creates in fibreglass. Tipoti has been instrumental in a TSI art movement, transforming traditional carving techniques (using turtle shell and wood) into new media such as aluminium, bronze, and fibreglass. Fibreglass, in particular, provides Tipoti with the fluid expressive means to characterise his figures. The lightweight quality of fibreglass also helps in creating performance pieces that are used as part of Tipoti’s dance troupe, the ZugubalTraditionalTorresStraitIslandDanceGroup. The troupe gained international recognition recently when it performed in London as part of the program of events supporting the British Museum’s exhibition IndigenousAustralia:enduringcivilisation (23 April–2 August 2015).

The development and presentation of this exhibition draw on a broad collaborative network supporting contemporary TSI art, and Alick Tipoti in particular. We thank Michael Kershaw, Director of the Australian Art Print Network, for assisting with all aspects of the exhibition, and Andrea and Peter Hylands’ Creativecowboy films for providing highlights of Alick’s filmed performance work for the exhibition, as well as video stills for inclusion in the publication.

We are particularly indebted to Dr Sally Butler, Senior Lecturer in Art History, University of Queensland, and Dr Liam M. Brady, Senior Lecturer, Monash University Indigenous Centre, for their scholarly research and outstanding contribution to this publication, and Dr Marian Hill for her editorial support.

Gallery staff, past and present, including Janette Laver, Kelly Jaunzems and Janet Parfenovics, have helped shape both the exhibition and supporting publication, and I thank them for their professionalism and dedication.

Final words of thanks must, of course, go to the artist, Alick Tipoti, who has worked tirelessly over the past year and shared his cultural knowledge, biographical information, and insights into his art practice. We are indebted to him for his generous collaboration in bringing this exhibition to fruition.

Andrea May Churcher Director Cairns Regional Gallery

Dr Sally Butler

Senior Lecturer in Art History

University of Queensland

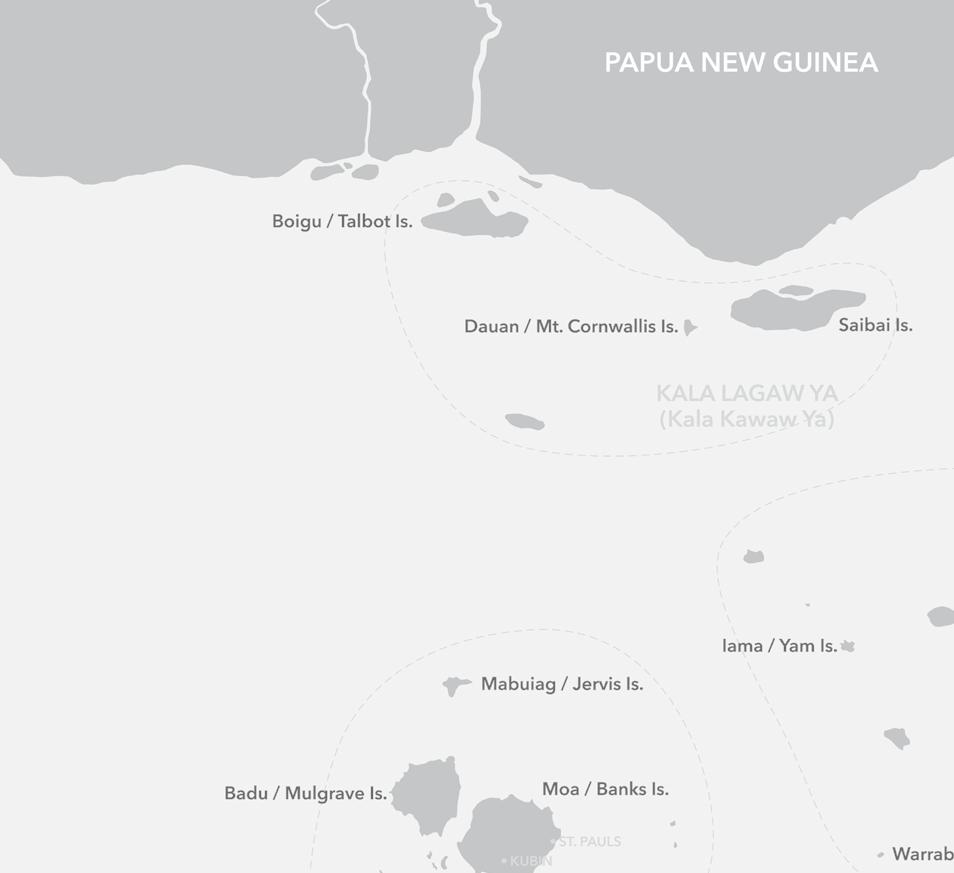

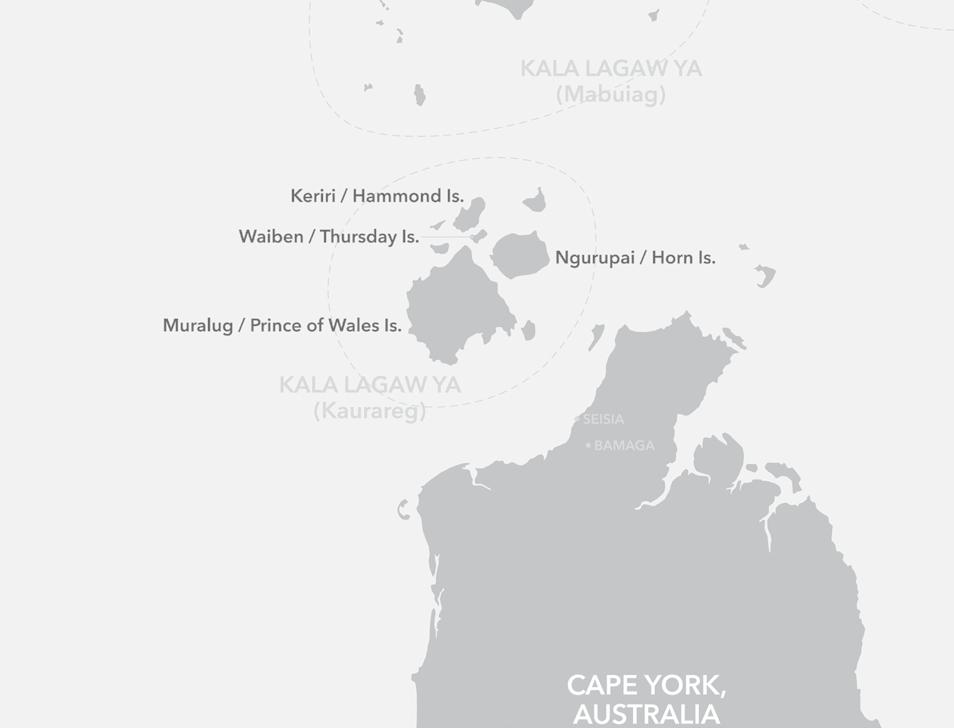

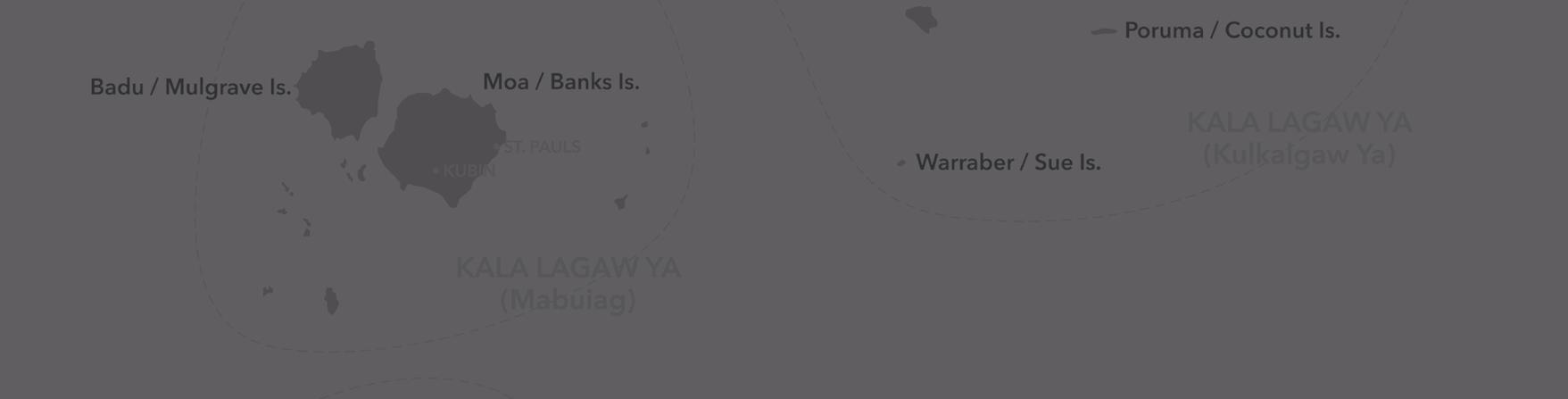

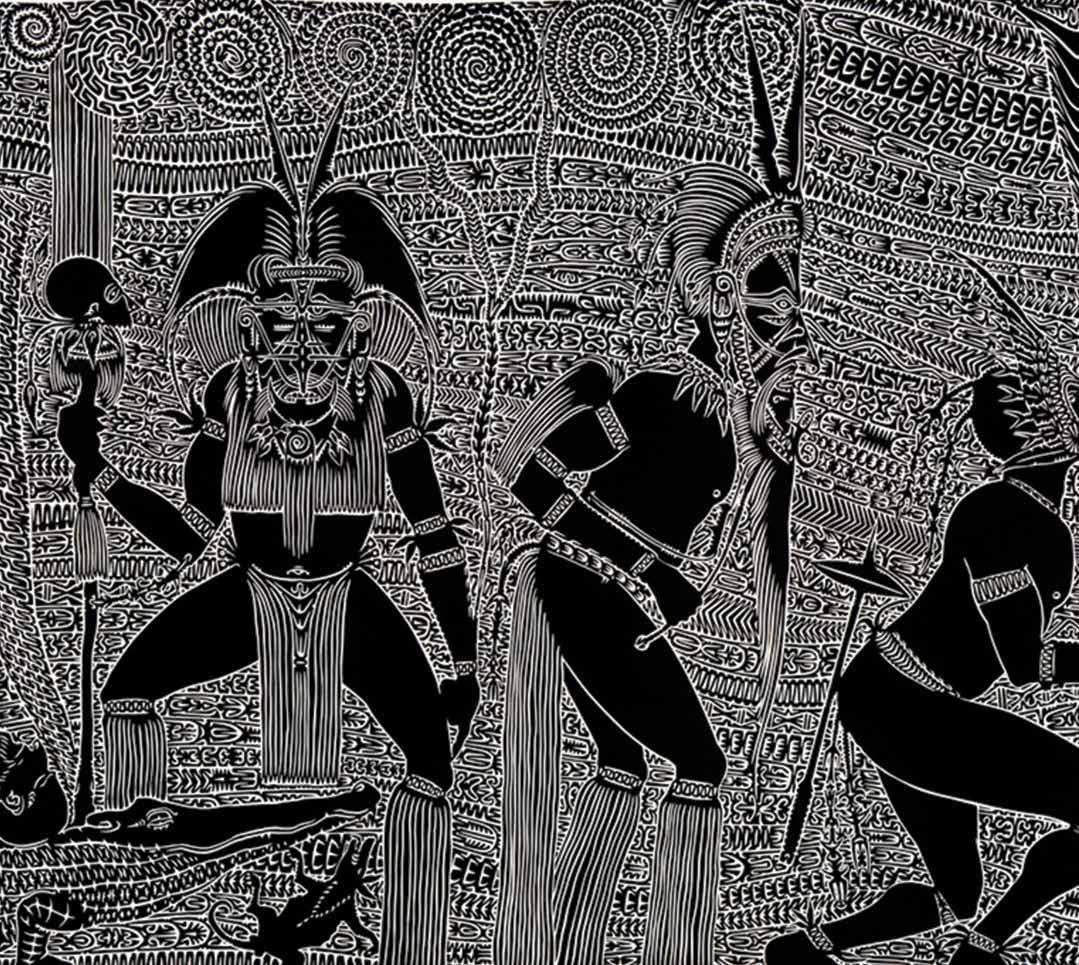

This exhibition explores how Zugubal, the spirits of Zenadh Kes ancestors, live on in the contemporary art of Alick Tipoti. Zenadh Kes refers to the Torres Strait Islands in Tipoti’s KalaLagaw Ya language and means people of the land, sea and sky. A total marine environment, or seascape, is encapsulated in a complex Zenadh Kes cosmology that supports traditional perspectives of natural, social and moral order. Tipoti draws on the creative energy of Zugubal ancestors, and walks in their footsteps, through his cultural practices of dance, chant, and visual art. Relationships between these three practices underpin this exhibition as it resonates with the synchronised rhythms of the dance, drums, chants and visual patterning.

Zugubal:AncestorSpirits is the first exhibition to consider how Zenadh Kes rock art inspires a new generation of artists. Contemporary artists are active in documenting Torres Strait Islands (henceforth TSI) languages and traditional knowledge that relate ancestral stories to everyday life. Imagery in contemporary art anchors this knowledge, just as rock art performed the same function when it was first created. Formal records of rock art in the TSI region originated in 1898, with Cambridge University’s expedition to the Torres Strait Islands. This field study captured a diverse snapshot of ethnographic and scientific data that have proven useful for present-day Torres Strait Islanders in connecting with their past. This nineteenth century archive is also a reference point for archaeologists who are studying rock art in the Torres Strait Islands today.

On entering Zugubal:SpiritualAncestors, audiences experience the synchronised rhythms of Zenadh Kes cosmology through sounds of music and chanting, and through visual imagery that captures traditional knowledge about the natural and ancestral worlds in complex patterns. There is no distinction between the natural and ancestral spiritual worlds because the ancestors have a profound presence in Tipoti’s creative imagination and everyday experiences. Artworks in this exhibition are selected to profile the diversity of Tipoti’s visual art practice, and to demonstrate how contemporary materials and methods help to regenerate a worldview that makes sense of contemporary life in Zenadh Kes

Signature pieces included in the exhibition date back to 2006, when Tipoti commenced the first of an ongoing series of largescale linocut prints that convey the cosmological scale of his subject matter. More recent artworks in the exhibition feature

Tipoti’s growing interest in relationships between cosmology and traditional chants. Fibreglass sculptures of a drum, canoe, masks and dance headdresses recreate the experience of a vibrant cultural seascape that is celebrated and revered by the people who understand its natural and spiritual rhythms. Included in the exhibition are new prints that have not been previously exhibited, and which pertain to waterspouts and moon imagery. These are cosmological themes that relate how Zugubal: the Ancestral Spirits, guide the community to successful and sustainable hunting and fishing by understanding nature’s climatic cycles and evolving ecological conditions.

Links between the visual and performing arts are a feature of this exhibition because they are fundamental to understanding Alick Tipoti’s artistry. This exhibition approaches a concept of art from an Indigenous perspective where, in essence, all things are connected. Tipoti’s role in regenerating traditional knowledge and cultural practices, such as interpretations of rock art in his own imagery, collapse distance between the past and present. The exhibition encourages audiences to experience a circular dimension of time, where the past constantly circulates in the present. The past is simultaneously the present and the future. Ancestral spirits are not simply depicted in the imagery, but are indeed present in the rhythms of Tipoti’s art.

The significance of Alick Tipoti’s art reaches far beyond Australia’s cultural heritage. It belongs to a global resurgence of art practice connected to cultural traditions that are formally protected under the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation’s (UNESCO’s) 2003 ConventionfortheSafeguarding oftheIntangibleCulturalHeritage. This Convention seeks to preserve not just the material aspects of cultural traditions, such as rock art and artefacts, but also immaterial traditions such as song, dance, storytelling, and knowledge. The Convention regards the significance of intangible cultural heritage as a mainspring of cultural diversity and a guarantee of sustainable interdependence between intangible cultural heritage and the tangible cultural and natural heritage. It is the essential interconnectedness of all aspects of life, such as in Zenadh Kes cosmology, that inspires ethical attitudes towards sustainable life for the future.

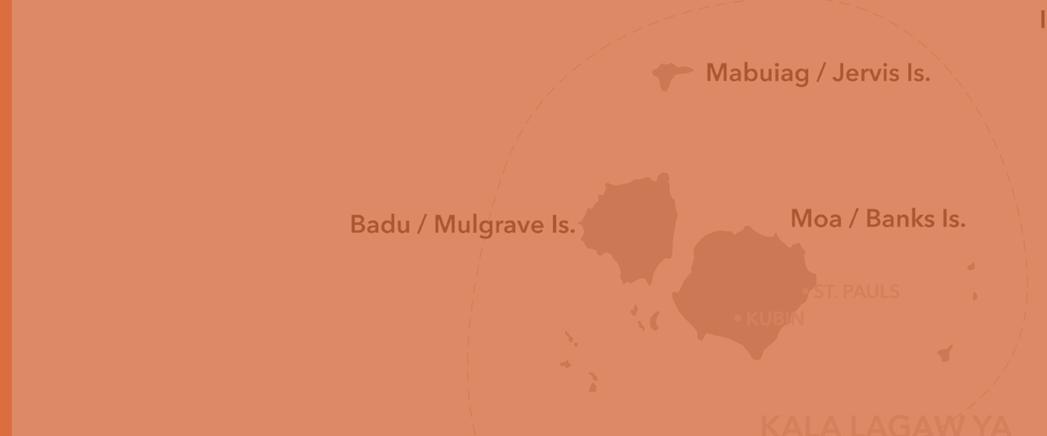

Alick Tipoti was born on Waiben (Thursday Island) in Maluilgal (Western Torres Strait) in 1975. His parents came from Badu (Mulgrave Island), where Alick lived as a child. His father and grandfather were both skilled craftsmen and artists and Tipoti learnt from them whilst watching them work throughout his childhood. The artist’s totems are thupmul (file ray) that relates him to Badu, and koedal (crocodile) that relates him to nearby Mabuiag Island. In 1993 he achieved an Associate Diploma (Arts) from Thursday Island TAFE, followed by an Advanced Diploma (Arts) from Cairns TAFE in 1995. In 1998 Tipoti completed a Bachelor of Visual Arts (Printmaking) at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra. Tipoti’s research into visual traditions of Zenadh Kes expanded during his studies at ANU. At this time he had the opportunity to study items held in Cambridge University’s Haddon Collection, the archival home of fieldwork conducted during the previously mentioned 1898CambridgeAnthropologicalExpeditionto

Torres Straits. Tipoti also initiated a dance troupe for which he designs the costumes and choreography. He explains, “I took my love of culture a step further by establishing a dance troupe, to make sure that our stories are told correctly in that sense. It’s based on the ancient style and is a very protocol-based style of costumes.”

This catalogue expands existing knowledge about TSI contemporary art by incorporating Alick Tipoti’s insights into his art as expressed through an interview with the exhibition curator. An essay about current studies into TSI rock art follows, written by Dr Liam Brady who is an archaeologist from Monash University working with local communities, and Alick Tipoti. The final essay takes an art history perspective of Tipoti’s growing interest in cosmology and chant, and considers how his artistry connects the rhythms of Zenadh Kes across time, and across the spaces of the Torres Strait’s land, sea, and sky.

with Janette Laver Exhibition Curator

Exhibition curator, Janette Laver, interviewed Alick Tipoti in June 2015 to give audiences some background on the artist’s inspirations and aspirations regarding this exhibition.

JL:Alick,therehasn’tbeenmuchdiscussioninthepastabout therelationshipbetweencontemporaryTorresStraitIsland(TSI) artandrockart.Canyoutellussomethingaboutwhatkindof knowledgeoflocalrockartyouhadgrowinguponBaduIsland?

AT: I remember going pig hunting and the like where we’d come across the rock art. We knew it was a sacred site, but knew not to investigate because we were young boys, and it was not culturally appropriate for us. But it would be different now as an artist, if I was to sit down to study it. So I had seen quite a few rock art sites when I was a youngfella running around in the bush. But we were always aware of the protocols that we weren’t allowed to touch or go near them. We knew that ancient people made the images. When we told an adult about seeing them, or an Elder, they would tell us to not go near them. Archaeologists started investigating the rock art only in the past 10 to 15 years.

JL:Sowasyourinterestinrockartstimulatedafteryou commencedartstudiesanddelvingintotheHaddonarchive?

AT: Yes, Haddon had some sketches of rock art but it’s different, a sketch is different from a photograph or the images produced by the technology that archaeologists use today. But when you see the rock art from this perspective you almost try to travel in time and think about what they saw when they were drawing the rock art. Was there a ship there when they were drawing it? You almost try to look out to the sea and try to visualise how this was then, and how they tried to interpret these events on rock art. But with the rock art, the main thing that I was interested in was the baywa, the waterspout, because there were a lot of those and they related to stories that we know today. I’ve seen a lot of actual waterspouts out at sea. If there is a dugong on top of the waterspout in the rock art it is definitely a baywa. There are many rock art images of canoes, headdresses, totems, but for some reason I really like the waterspout images. My interest is definitely with the waterspout.

JL:Canyoutellusalittlemoreabouttheculturalprotocols regardingrockartthatareupheldbycommunitiesonBaduIsland today?

AT: When I was a child the protocols were just basically do not interfere or try to alter the rock art in any way. But now with the archaeological people working with communities, we have come to realise how fragile it is. We have taken a further step trying to preserve it. If something is discovered we get the rangers to go and mark it - put a sign there that warns that it is a restricted sacred site or whatever. With the advice of archaeologists, we are looking to preserve it. So where the rock art is on an exposed slope we put a silicone seal on it to protect it from rain and weather. But from a traditional perspective, what the ancestors have drawn - you don’t try and redraw it. It’s like any other ancient artefacts. If it’s masks, you don’t try and use the original mask to do a performance because that was a different time.

JL:WhatdoestheBaducommunitythinkaboutthe archaeologicalstudiesthathavebeenconductedonBaduIsland overthepasttwodecades?

AT: The Elders today want it to be preserved and recorded. As a Director in our Native Title claim, I have been the person talking to both the Elders and archaeologists and meeting with them. The Elders want it recorded. They want all the information documented and preserved, particularly the faded images that only technology can pick up - those ones especially, because otherwise you don’t know it’s there. The Elders realise that it is important for us to know about the rock art, and that we can use it for evidence or educational purposes for the next generation.

JL:Inregardstowheretherockartisonknownsacredsites, howdoesthatimpactonarchaeologicalstudies?Arethereany protocolsthatarchaeologistshavetoabidebywhilethey’rethere?

AT: Yes, no outsiders are allowed there alone, regardless of what you specialise in. No archaeologists are allowed to explore by themselves – there are always Traditional Owners, rangers, or Elders, present. So they will advise where to go, what to look for. Obviously archaeologists have an eye for where there might

be a painting, so they go together with the local people. When something is discovered it’s not touched without permission. The archaeologists have respected that and there is a really good relationship between the community and the archaeologists, especially the ones based at Monash University in Melbourne, who did fieldwork out there.

JL:Inwhatwaysdoesthesymbolisminrockartinfluenceyour ownartpractice?

AT: I think it comes down to the waterspout. The reason I’m really fascinated with the waterspout and lightning imagery is because those designs are on our forearm bands (used in the dances). We call it kadeep and on one edge I’ll have designs representing the sea. On the other end are designs representing the cylinder of the spout. So I’ll have lightning striking down, which is seen in rock art, and a waterspout going up. So basically there is an understanding of spiritual ancestors coming down through the lightning and going up through the waterspout. I use a lot of those symbolic designs or patterns in our dancing gear. The title of the dancing is Zugubal, meaning many spiritual ancestors.

JL:Thewaterspoutsarerepresentedinanumberofprintsinthe exhibition,aren’tthey?

A: Yes, they appear in Gidalal, Zugubal and Four Seasons. Throughout my early work, the waterspout wasn’t a dominant symbol, but it is now that I am more connected with the spiritual ancestors. It sort of came to me more when I started making masks. It’s different when you carve an image of a mask on lino to making the real mask and performing with it. You feel more connected. It’s a different thing altogether. That’s when I embraced the waterspout in images and designs.

JL:Canyoutellusalittleabouthowyouthinkyourarthelps outsiderstounderstandtheZenadhKes(TorresStrait) cosmology?

AT: Obviously we have our own star constellations and they are not just star constellations, because every culture has different star constellations. With our star constellation, it’s not just linked with navigation but it connects to which direction the sea current flows and things like that. And when a bird migrates, when turtles mate, and when the yam is ready to be dug up. They’re all in star constellations as well. For seafaring people like our culture the stars are about navigation. We knew about our star constellations before we learnt about European constellations like the Southern Cross, the Milky Way, and all of those. Europeans know the Southern Cross as a singular star constellation but to us it is the left hand of Thagai, who is a Zugub, in a canoe. So it is actually something small, but it is part of something big. And we have the canoe with Thagai and Kang Kang is sitting at the back, and Thagai stands at the front holding a spear and a branch with leaves. His left hand is actually the star constellation. So for us the Southern Cross is something small belonging to something much larger.

JL:Justchangingdirectionalittle,isthereaspiritualdimension tothehiddenimageryofyourpatterns?

AT: Yes, especially with the masks, or faces of people. I think my mind turns back to one of my early pieces which is called Aralpaia A Zenikula. I have a lot of mask faces with patterns or designs that include something hidden. But it’s all to do with the main images on the block, and being in the presence of spirits, or in other words, the spirits being in the present. They’re all together rather than just the main images. So, it would be different if I were hiding just a bird or something in the patterns. With the masks the hidden image in the pattern is more of a spiritual figure. It’s the same with human beings, there’s more to itthere’s a spirituality that underpins a cultural perspective. It’s the

same thing, what’s hidden is actually not like a spirit of the story, but the spirit of the print.

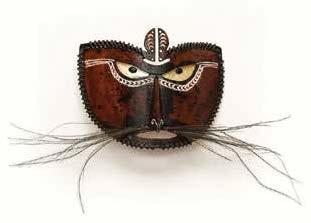

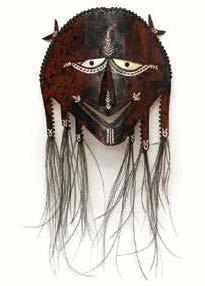

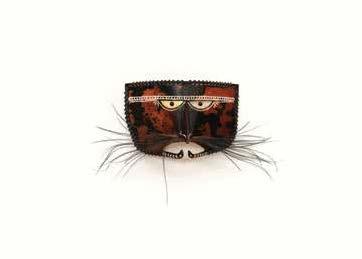

JL:Whydidyoucommencetheumaymasks,thedogmasks?

AT: I’ve always wanted to revive the dog masks since I started the Zugubal dances. I’ve always wanted to revive the ancient story, and how it’s told - not in a modern traditional style of dancing - how Torres Strait Islanders dance today where they stand in a line. I wanted to re-enact the actual story through not only songs and dance, but through re-enacting it, if you know what I mean? So the umay masks were basically the link to the story of Sesserae. We have songs and chants, but I’ve composed and choreographed my own. And I tell it like it was a movie rather than a choreographed dance.

JL:Soitismoreofastory…?

AT: It’s more of a storyboard or story telling in a sense, rather than just singing. And it is more of a chant than song. Because, to me, chants have a closer link to the ancient ways. But the dog mask is all about reviving the story of Sesserae, and obviously, dog (umay) is a totem on Badu Island as well.

JL:ThankyouforsharingtheseideaswithusAlick.

Dr Liam M. Brady Monash Indigenous Centre Monash University

Across the Zenadh Kes (Torres Strait) landscape, granite boulders and rock shelters have been inscribed with symbols that reflect aspects of Islander and Aboriginal history, identity, memories and experience. As one of the most widespread and recognisable forms of visual heritage, rock art allows us to gain insight into the early artistic traditions from the region, a legacy that Alick Tipoti continues through his work today. This essay introduces Zenadh Kes rock art and then explores the sites and motifs from the island of Badu as a way of situating Alick’s work against a backdrop of an earlier artistic tradition that today provides inspiration and guidance to Alick and other Badhulgal artists.

Zenadh Kes rock art

The first known recording of Zenadh Kes rock art was made by Cambridge University anthropologist, Alfred Haddon, in the late 1800s when he used sketches and black and white glass plate negatives to document motifs from two islands: Kirriri and Pulu. In addition to documenting motifs, Haddon recorded valuable

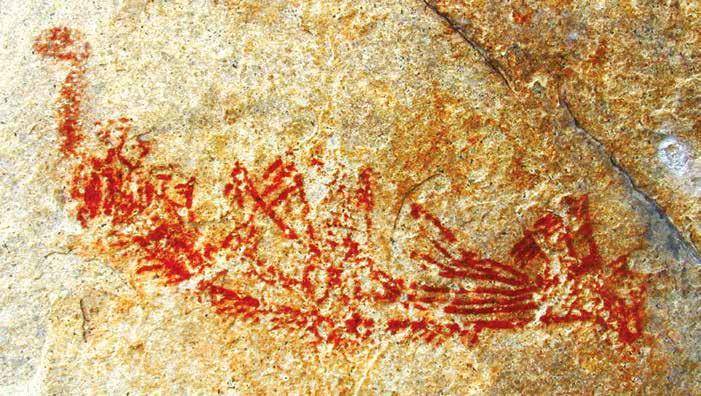

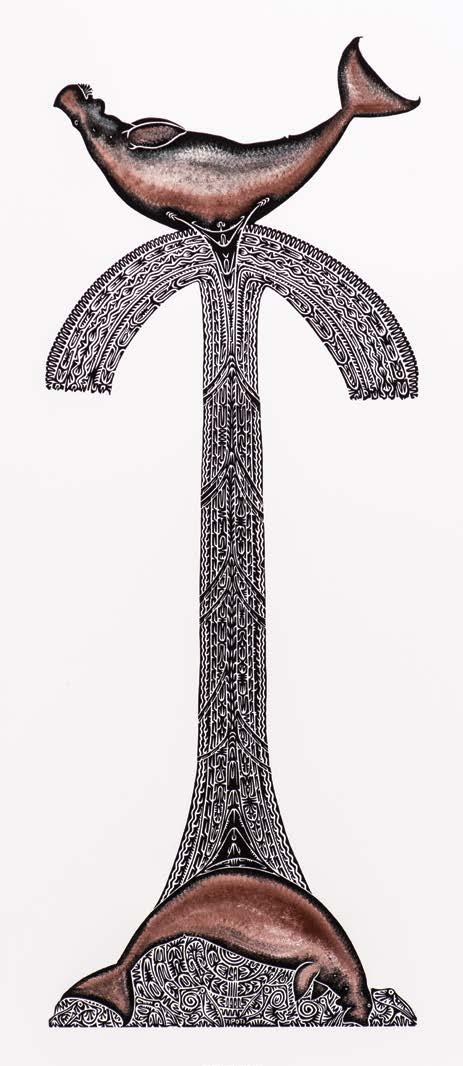

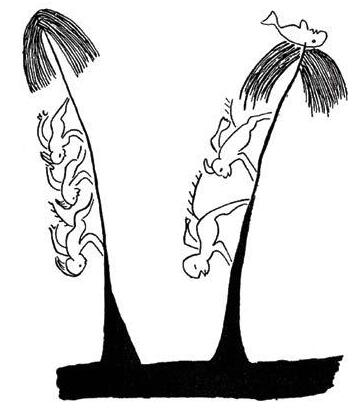

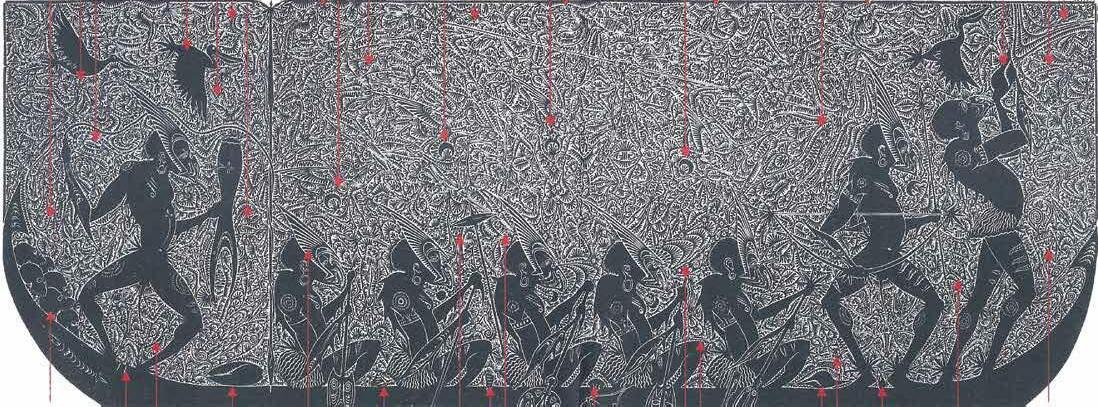

ethnographic data about some images that help to explain their meaning as well as the reasons for production. Based on this ethnographic information, two major themes emerge in Zenadh Kes rock art, namely those of mythology and totems. At Pulu islet’s kod (ceremonial) site in western Zenadh Kes, Islander mythology was clearly visible through the depiction of five red painted spirit figures identified by Haddon as “mŭri” (one panel featuring two mŭri dancing and another beating a drum while the other two figures are depicted in profile at a nearby site), and a distinctive baywa (waterspout) motif drawn with a central line and a series of V-shapes positioned on either side extending the length of the central line (Figure 1, Figure 2). Using information obtained from the Goemulgal (Mabuyag Islanders), Haddon (1904:359) noted a close association between the baywa and mŭri:

[t]he mŭri ascend and descend waterspouts in the same way as sailors do on ropes. The waterspouts are their spears by means of which they catch dugong and turtle and other large marine animals; the mŭri pass dugongs, turtles, sting-rays and other creatures up the waterspout.

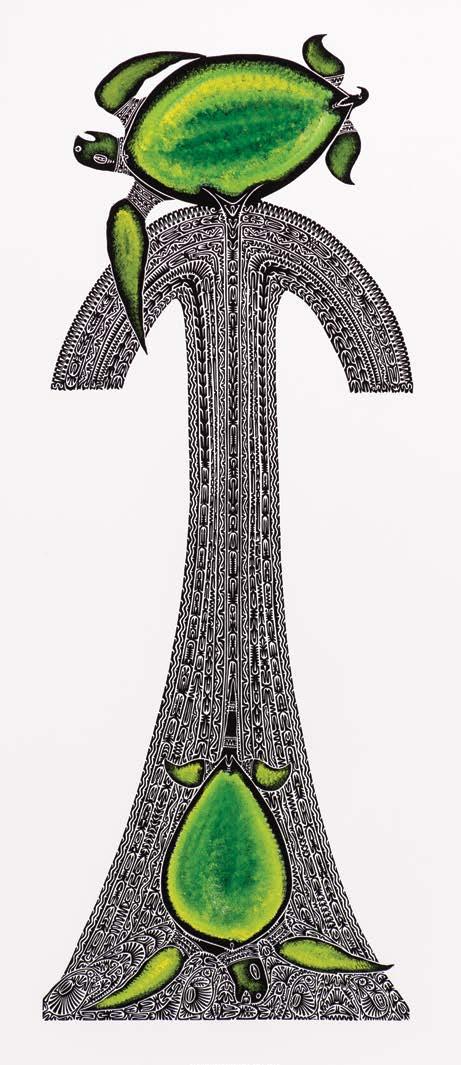

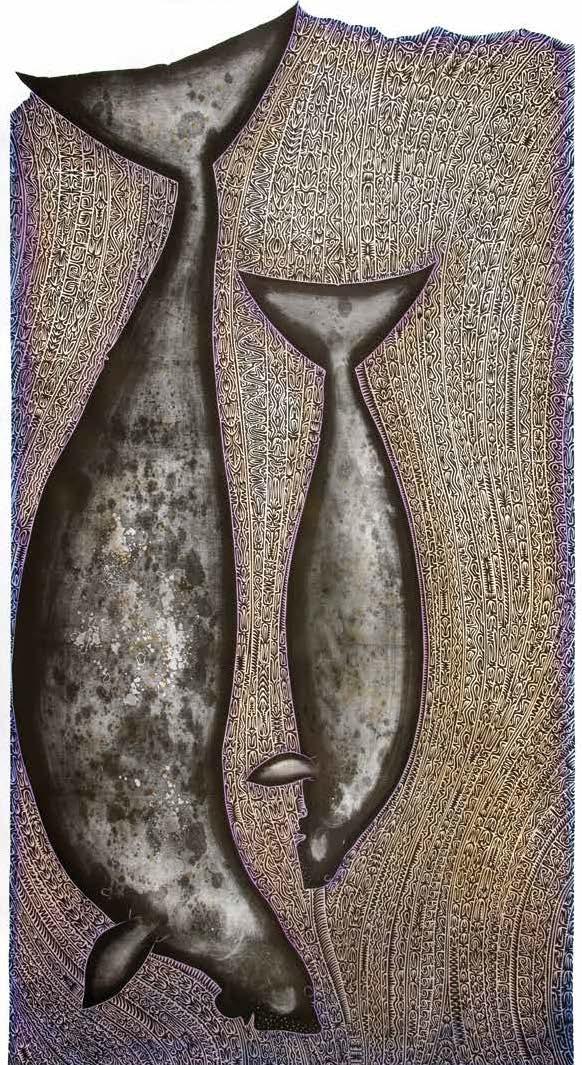

IMAGE LEFT

Baywa(Waterspout-turtle) 2014 single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle, handcoloured 198 x 125cm

Image courtesy of Michael Marzik

IMAGE RIGHT

Figure 2: Drawing by Gizu of Mabuyag of muri spirits climbing a baywa (waterspout) (from Haddon 1904:360, figure 78).

At the island of Kirriri in south-western Zenadh Kes, Haddon recorded how painted canoe motifs were linked to Islander and Aboriginal cosmology. A key part of this relationship was based on beliefs about the conversion of a soul of a recently deceased individual to a markai (ghost or spirit of a deceased person). Haddon (1904:357) recorded that when a person died, their soul or mari is ferried by canoe to Kibu – a spirit-island located somewhere to the northwest of Zenadh Kes. Upon reaching Kibu, the mari is hit over the head with gabagaba (stone-headed clubs) by markai already inhabiting Kibu. The mari is then converted to a true markai and taught how to fish and spear dugong. When Haddon visited the Kirriri rock art site in 1888 he sketched and photographed two painted canoes and described what they represented:

On certain rocks in Keriri [Kirriri], close by the crevices in which we found the skulls…are various pictographs representing totem animals and two canoes…[t]he canoe was taken by the markai from the sara, sea-birds, who formed the crew of the canoe…[o]n ordinary occasions the markai paddle the canoe in the open sea on calm nights to catch turtle, dugong or fish (Haddon 1904:358).

In addition to the relationship between the painted canoes and markai, Haddon’s comments about Kirriri’s “totem animals” (a hammerhead shark, dugong, and a turtle) reveal important insights into the symbolic role these motifs play in the region. In western and central Zenadh Kes, each clan was identified by a major totem and each clan had its own recognised territory on the island. In addition, people visiting another island would be looked after by individuals of the same totem and in cases where there were no totemic relatives, they would stay with individuals whose totems were associated with theirs (Haddon and Rivers 1904). Therefore totems were significant elements used to link people across western and central Zenadh Kes. Additionally, representations of totems found in rock paintings, inscribed on portable material culture objects (e.g. drums, tobacco pipes), and as designs scarred on people’s bodies became part of a broader symbolic referential system that not only reflected clan identity but were also used to signal relationships between individuals from across the region.

Following Haddon’s early work, a small amount of rock art recording was carried out by amateurs, travel writers, anthropologists, and archaeologists (see McNiven and David 2004). While most of this work focused on describing motifs or speculating about their meaning, some researchers recorded oral histories that have shed light on the authorship of some paintings. For example, in the 1960s, Margaret Lawrie recorded a story on the island of Dauan in western Zenadh Kes which indicates that some paintings were made by Kiwai raiders (from Kiwai Island in the Fly River estuary in southwestern Papua New Guinea) who voyaged to Dauan on a headhunting expedition (Lawrie 1970). The Kiwai arrived secretly at night in many canoes and, while waiting to attack the village at dawn, they drew pictures with red ochre on a boulder now known as Kabadul Kula. Although no mention is made in the oral history of which paintings were made, the story provides important details concerning a Papuan (or more specifically a Kiwai) influence on rock art from Dauan.

In 2000, a new phase of rock art recording began in Zenadh Kes, this time as part of partnership-based projects between individual Islander and Aboriginal communities and archaeologists from Monash University led by Prof Ian McNiven and Dr Bruno David with a team of PhD students. As part of the broader Western Torres Strait Cultural HistoryProject, a total of 56 sites consisting of 983 motifs were recorded between 2001 and 2004. A key finding of the project was that rock art designs were being shared across western and central Zenadh Kes and into southern Papua New Guinea and the tip of Cape York Peninsula. Furthermore, many distinctive designs recorded in rock art could also be found in other decorative media (e.g. scarred designs on people and carved on wooden objects) which suggests that design conventions were being transferred across mediums thereby demonstrating how Zenadh Kes rock art was only one part of a much larger and widespread artistic system.

An important part of the project’s recording methodology was the use of advanced computer enhancement techniques. Owing to the harsh coastal conditions in the region and the exposed nature of many sites, the pigments used to produce the images deteriorates rapidly making it difficult to see many motifs. As a result, computer enhancement – the saturation of faded colours (e.g. red, white, yellow) using photo-editing software to make images more clearly visible – was applied to each painting (including any trace of pigment on

the rock surface) documented during the project (Brady 2006). Digital photographs were then imported to Adobe Photoshop and enhanced using a series of interchangeable commands (e.g. saturation, hue). A significant outcome from the use of computer enhancement was that of the 983 rock paintings recorded during the project, 113 (11% of the total assemblage) could be identified onlyafter computer enhancement was applied, meaning these images would most likely have remained too deteriorated/faded to properly identify without computer enhancement.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the first Badhulgaw rock art site was documented at Badu. During a visit to the island, anthropologist Jeremy Beckett recorded at least one rock art site at Argan, noting the abstract style of the paintings and the depiction of what looked like a suckerfish (gaapu) (Beckett 1963). A more detailed understanding of the nature and breadth of Badhulgaw rock art became available when Monash University archaeologists began working in partnership with the BadhulgawKuthinawMudh (Torres Strait Islander Corporation) to document and learn more about Badhulgaw rock art. From 2001 to 2004 a total of 24 rock art sites consisting of 188 pictures were identified and recorded from across Badu, often in clusters at places such as Ikis, Kiyanplay, Kotheydh, Kusaran Pad, and Kowtinab, while a smaller assemblage (two sites, 15 paintings) was recorded at Zurath, a small offshore island 10km south of Badu (Brady 2010) (Figure 3, Figure 4).

The images recorded across the Badhulgal landscape reveal a complex and diverse assemblage. Badhulgaw rock art is composed of painted abstract motifs such as geometric shapes (diamonds, circles, triangles), lines (straight, curved, parallel, rayed), chevrons, zigzags, and fern-shapes as well as figurative or naturalistic imagery such as animals, e.g. fish, dugong, (Figure 5), human figures, faces/masks, and material culture objects such as canoes and a drum (Figure 6). Whilst information about the exact age of Badhulgaw rock art is unknown, it is likely to be

fairly recent in age given its exposed settings and subsequent rate of deterioration. When compared to elsewhere in Zenadh Kes, Badhulgaw rock art is unique in that it features the only hand stencil known from the Zenadh Kes region, while also incorporating a diverse range of colours and techniques (red, yellow, white; monochrome, bichrome).

Using different forms of knowledge (Badhulgal, archaeological, anthropological), several themes have been identified in Badhulgaw rock art. An important component of the Badhulgaw rock art assemblage is the relationship between some motifs and Badhulgal maritime or “Saltwater” identity. This relationship is most visible through the striking depictions of canoes and marine animals. The large ocean-going double outrigger canoes (up to 70 feet in length) were a vital part of the Badhulgal toolkit, but their importance was not limited to a transport role. Canoes also had social and ceremonial significance through their involvement in the “canoe traffic” exchange network with south-western Papua New Guinea, as well as featuring in many oral histories from the region (Lawrence 1994). Canoes were commonly encountered and described by Europeans during the early contact period and many of the features they recorded are visible in the rock art from Badu and Zurath. At a site near Wakaydh on Badu are two elaborately decorated red painted canoes with striped hulls, distinctive hooked bows, a grass fringe, and flags projecting from the middle and stern. One of the Wakaydh canoes also features the only known occurrence in Zenadh Kes of people depicted inside the painted vessel (Figure 7). Other canoe motifs from Kiyanplay (Badu) and Zurath are simpler in design yet still feature some combination of the many distinctive features of Zenadh Kes canoes. Among the most common marine animals featured in Badhulgaw rock art are fish, fish/dugong, octopus, and crocodile/ lizard. One notable fish motif from a site at Kowtinab is the gaapu (suckerfish) – a small fish that Islanders used to attach to dugong and turtle during the pursuit and hunting of these two important food sources.

Badhulgaw rock art also features shared designs between Badu, other islands in Zenadh Kes, and southern Papua New Guinea. At Dhelalbibi on the north-west side of Badu, and a shoreline

site on the south-east side of Zurath are distinctive red triangle shapes with two small downward curving lines extending from the triangle’s tip (Figure 8, Figure 9). These motifs are similar to others found at rock art sites on Pulu, yet are found more broadly on material culture objects such as decorated tobacco pipes collected from Mer and Kiwai Island at the mouth of the Fly River, as a design carved on the mouth of warup drums collected from across Zenadh Kes and south-western Papua New Guinea, and as a scarred design recorded on women at Mer in the late 1800s. Likewise, paintings of faces/masks from Badu displaying distinctive concentric circle eyes can be linked to similar rock paintings from Dauan and Mua but are also a common feature on carved wooden boards, decorated with faces, from Kiwai Island and the Papuan Gulf region (Figure 10). These similarities reveal that the distinctive triangle shape and concentric circle eyes found painted in the Badhulgal landscape are widespread design forms which reflect some form of interaction between people and objects from these locales.

A broader look at Badu’s rock art reveals an intriguing pattern that highlights the role rock art played in marking the Badhulgal landscape. At Ikis, on the west side of the island, is a cluster of 12 rock art sites. The motifs located here are almost entirely abstract in nature whereas other sites on the island feature a mixture of abstract and figurative/naturalistic imagery. To understand what this pattern means relies on Badhulgal knowledge and additional archaeological evidence. Senior Badhulgal identified Ikis as a special or sacred place, while in 2001 a fragment of a turtleshell mask – an important piece of ceremonial paraphernalia – was rediscovered at Ikis, further enhancing the special characters of Ikis (David et al. 2004) (Figure 11). This knowledge, combined with the obvious change in the graphic content of rock art at Ikis, suggests that rock art played an important role in defining Ikis as a special place in the Badhulgal landscape.

The information generated about Badhulgaw rock art over several years of collaborative work reveals that the images are meaningful in different ways and are capable of casting light on many aspects of Badhulgal life. This rich artistic history and heritage provides an important setting with which to engage and understand Alick’s

work. A survey of Alick’s work reveals that many of the themes he incorporates into his artworks can also be found in rock art, particularly in the areas of Islander and Aboriginal cosmology through the depiction of spirit figures and baywa. By drawing on these themes, Alick continues this important legacy of Badhulgal artistic endeavour, linking the past with the present in new and innovative ways, and charting a future that embraces creativity, imagination and contemporary Badhulgal identity.

References

Beckett, J. 1963, ‘Rock art in the Torres Strait islands’, Mankind, 6(2): 52-54.

Brady, L.M. 2006, ‘Documenting and analyzing rock paintings from Torres Strait, NE Australia, with digital photography and computer image enhancement’, JournalofFieldArchaeology, 31(4): 363379.

Brady, L.M. 2010, Pictures,patternsandobjects:rock-artofthe Torres Strait islands, northeastern Australia, North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing.

David, B., McNiven, I.J., Bowie, W., Nomoa, M., Ahmat, P., Crouch, J., Brady, L., Quinnell, M., and Herle, A. 2004, ‘Archaeology of Torres Strait turtle-shell masks: the Badu Island cache’, AustralianAboriginalStudies, 1: 18-25.

Haddon, A.C. 1904, ‘Reports of the Cambridge anthropological expedition to Torres Straits’, Sociology,magicandreligionofthe western Islanders 5, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haddon, A.C., and Rivers, W.H.R. 1904, ‘Totemism’, Reports of the Cambridge anthropological expedition to Torres Straits, Sociology, magicandreligionofthewesternIslanders 5, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 153-193.

Lawrence, D. 1994, ‘Customary exchange across Torres Strait’, Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 34(2): 241-446.

Lawrie, M. 1970, MythsandlegendsofTorresStrait, St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

McNiven, I.J., and David, B. 2004, ‘Torres Strait rock art and ochre sources: an overview’, Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage, 3(1): 209-226.

Dr Sally Butler Senior Lecturer in Art History

University

of Queensland

If something is ‘off beat’ we expect it to not follow a standard beat musically or, more generally, to be unconventional. Therefore, ‘on beat’ would mean the opposite: following a standard beat or an essential rhythm, and reinforcing a convention. Alick Tipoti’s art falls firmly into the ‘on beat’ category in the manner that it exploits essential rhythms and conventions of time and space. His visual and performing arts re-establish and strengthen continuity between the ancestral past and the present through the rhythmic connectivity of Zenadh Kes cosmology. Traditional designs, ancient rock art, chants, dance, and music find a new vibe of inter-relationships that inspire contemporary life in his homeland. Rhythm in Tipoti’s spiritual seascapes and performances makes sense of his world, and gives shape to Zenadh Kes principles of natural, social and moral order. This ‘beat’ resonates across all of his art.

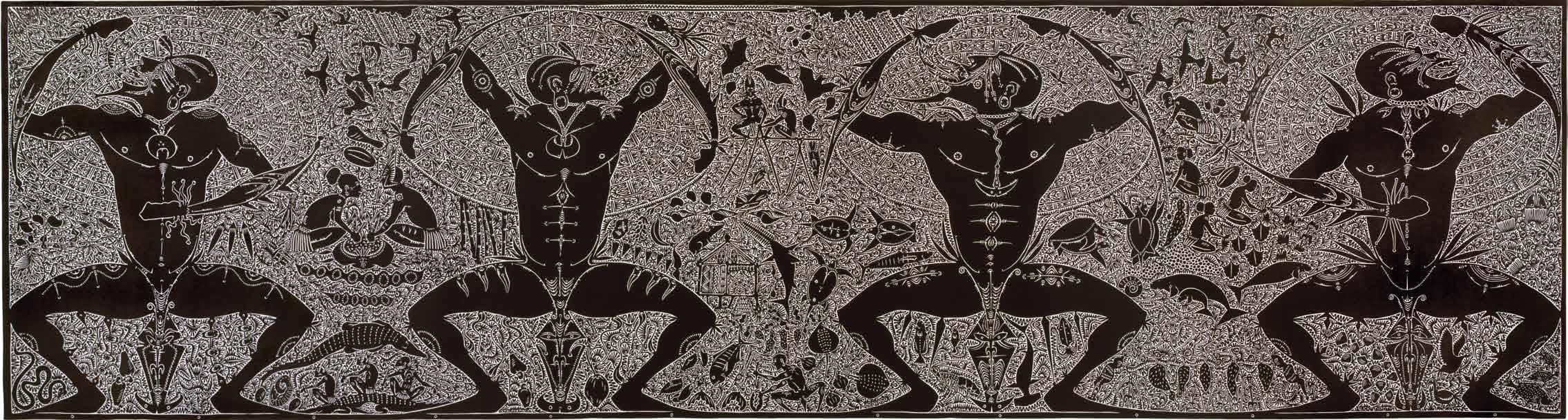

The Zugubal:AncestorSpirits exhibition aims to immerse audiences in a Zenadh Kes experience of essential rhythms that connect the land, sea, and sky; the past and present; and spiritual and everyday realms. Tipoti’s art exalts the principle that rhythm is the pattern and performance of life. The screened performance, Zugub,themark,thespirits, and the stars 2012, takes centre stage in the exhibition as it consolidates fundamental links between visual and performed rhythms in Tipoti’s art practice. Chants and drumbeats activate and energise visual symbols and totemic figures. Even when viewed in isolation, his artworks offer an experience of cultural performance. Visual rhythms perform the presence of ancestral spirits and vibrate with the energy of silent chants.

Rhythm plays an important role in the translation of Indigenous cultural traditions into ‘global’ contemporary art across the world. This is because rhythm involves cultural perspectives of time, and patterns for connecting with the past. Indigenous cultures frequently function within a tradition of ‘lived’ time that

differs to the ‘measured’ time of modern western life. (Bergson, 1911, 1994) European society after the Industrial Revolution organised itself on the basis of measuring time down to minutes and seconds because of the commercial principle that ‘time is money’. Hours of labour equalled volume of production, and everyday life ticked over to the ‘beat’ of the clock. This affected attitudes to the past, where the developing culture of consumerism accompanying industrialisation spawned a cult of the new. The past, the old, grew ever more distant from the now, the new. ‘Measured time’ has become so entrenched in modern life that few realise it is a choice, and just one of various methods used to order and understand human experience.

Tipoti’s rhythms engage audiences with the beat of ‘lived time’. His art foregrounds an experience of time rather than a measure of time, and facilitates simultaneity of different times at once. The past and the future can be present, and the future can precede the past. It is a non-linear and cyclic conceptualisation that privileges what connects us over time rather than that which divides us. This is why rhythm is so important. It is an abstract linking device, a kind of aesthetic glue that maintains the dynamics of a cyclic world of time.

The arts have always played a significant role in Indigenous cultural traditions because they assist in developing this ‘lived’ consciousness of time by activating the audience’s creative imagination. An artist’s creative imagination is only ever effective if it stimulates a sympathetic creative imagination in the audience. We engage with art’s illusions, we suspend disbelief, and we enter the world of the artist. In many ways, this is the definition of art across the history of humankind. In Alick Tipoti’s art we engage with a coming into presence of ancestral spirits through the performed rhythms of sounds, movements, and images.

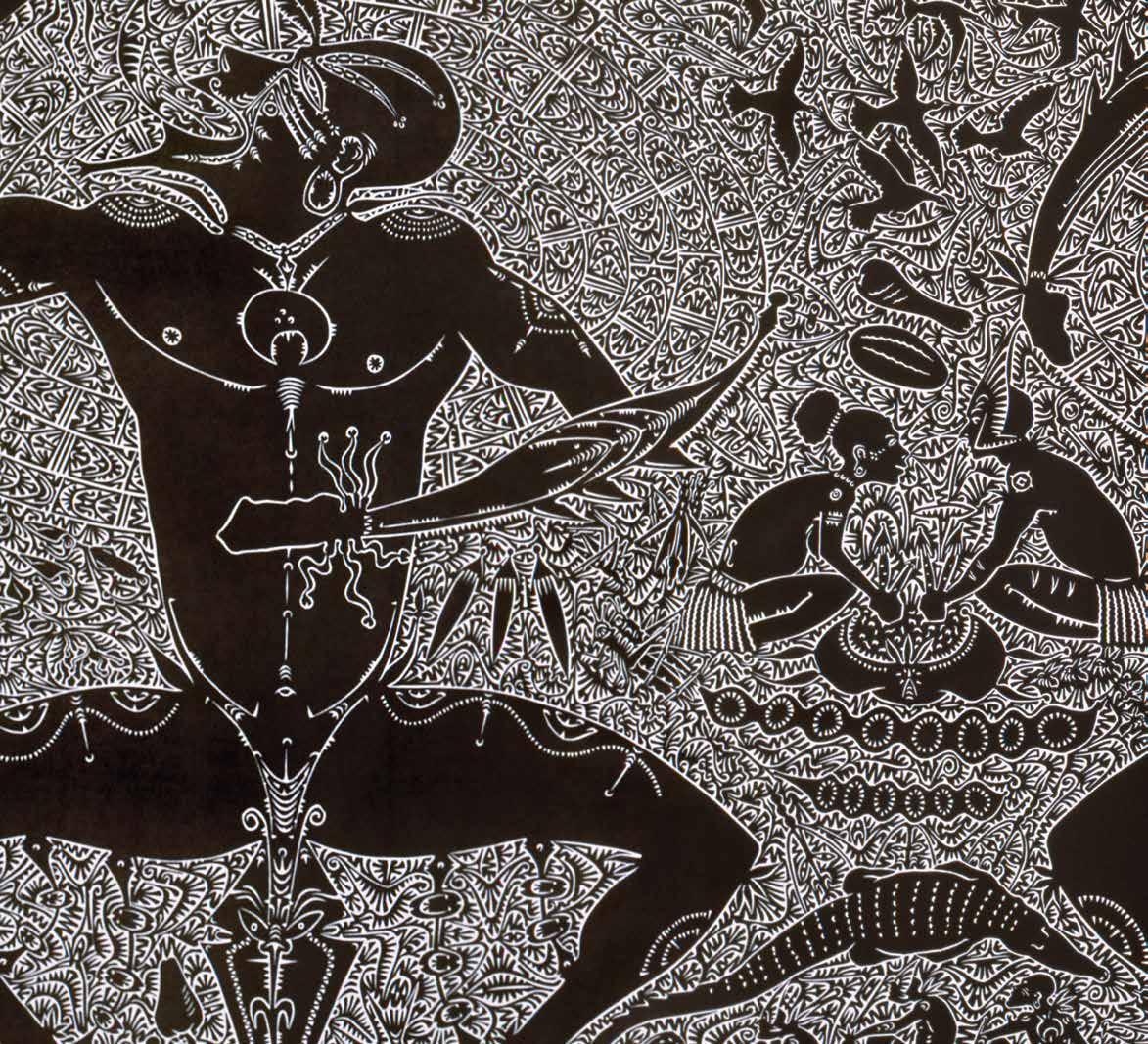

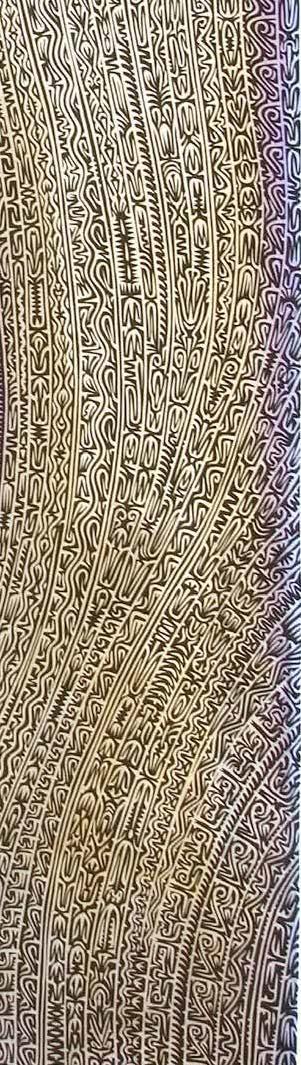

Optical illusion in Tipoti’s visual patterns stimulates the creative imagination to experience this sense of ancestral spirits coming into presence. Intricate visual patterns from traditional Zenadh Kes wood and turtleshell carving have today migrated to the medium of linocut printmaking. These patterns symbolise the complex array of ocean currents throughout the Torres Strait, but they also provide a matrix for visual magic. Tipoti’s Girelal 2011, is an example. The image of a shark lying between the birds at the top left of the image and the sea creatures below only becomes apparent on closer observation. The process of dormant images coming into view simulates the hidden presence of spiritual ancestors in Zenadh Kes everyday life. They are present in the fabric of everyday life, but remain largely invisible. Tipoti referred to this when he spoke of the spiritual presence that guides him in creating art late at night:

When I work late at night carving traditional designs, I can sense the presence of the spirits who I verbally acknowledge and thank in language for their guidance and help in visualising the words they have given me. I vividly remember an unusual event late one evening when I was guided to resketch and change the interpretation of a block I was about to carve. This was just one of the many occasions when I have connected with the Zugubal who have instructed me on the proper ways of our cultural traditions. (NewWorksbyAlickTipoti, Australian Art Print Network, 2004, 1-2)

Tipoti’s visual patterning, like that of all contemporary Zenadh Kes artists, and those of the past, is densely interlocked and conveys a sensation of connectivity that is palpable. It is almost impossible to separate off any part of the image because the part is always continuous with the whole. Distinctions between background and foreground fall away as hidden figures advance from background patterns. The imagery is grounded in an essential rhythm that manifests the connectivity of all things in Zenadh Kes cosmology.

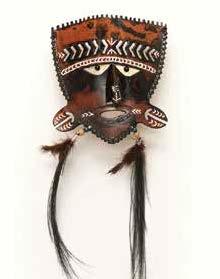

Tipoti’s mawa masks and dhoeri headdresses worn in dances are a key device in the performative illusion of ancestral spirits coming into presence. In the preceding ‘Interview with Alick Tipoti’ the artist describes how wearing a mask differs to drawing one in his artwork. When wearing the mask, he says “You feel more connected”. The rhythm of traditional chants emerges from the masks during a performance, and creates the presence of ancestral spirits. By wearing the dhoeri, performers become ancestral spirits, as they do when wearing the mask. Styles of dhoeri are unique to particular regions and feature totems through the bome (forehead framework) of the headdress.

Zenadh Kes cosmology is passed down through generations in mythological narratives that preserve, among other things, knowledge about biophysical life cycles; wind patterns and ocean currents; and the celestial positioning of stars at various times of the year. Human sustainability on islands of Zenadh Kes depends

on this knowledge of nature’s rhythms. It is imperative to know the sources for fresh water, the right time of the year to hunt marine and bird life, and when to collect shells and plants used for food and medicinal purposes. Celestial navigation is necessary in plotting a course for trading expeditions with other islands, and as far afield as the Papua New Guinea coast and Cape York peninsular mainland. Contemporary art in Zenadh Kes plays a significant role in preserving this knowledge.

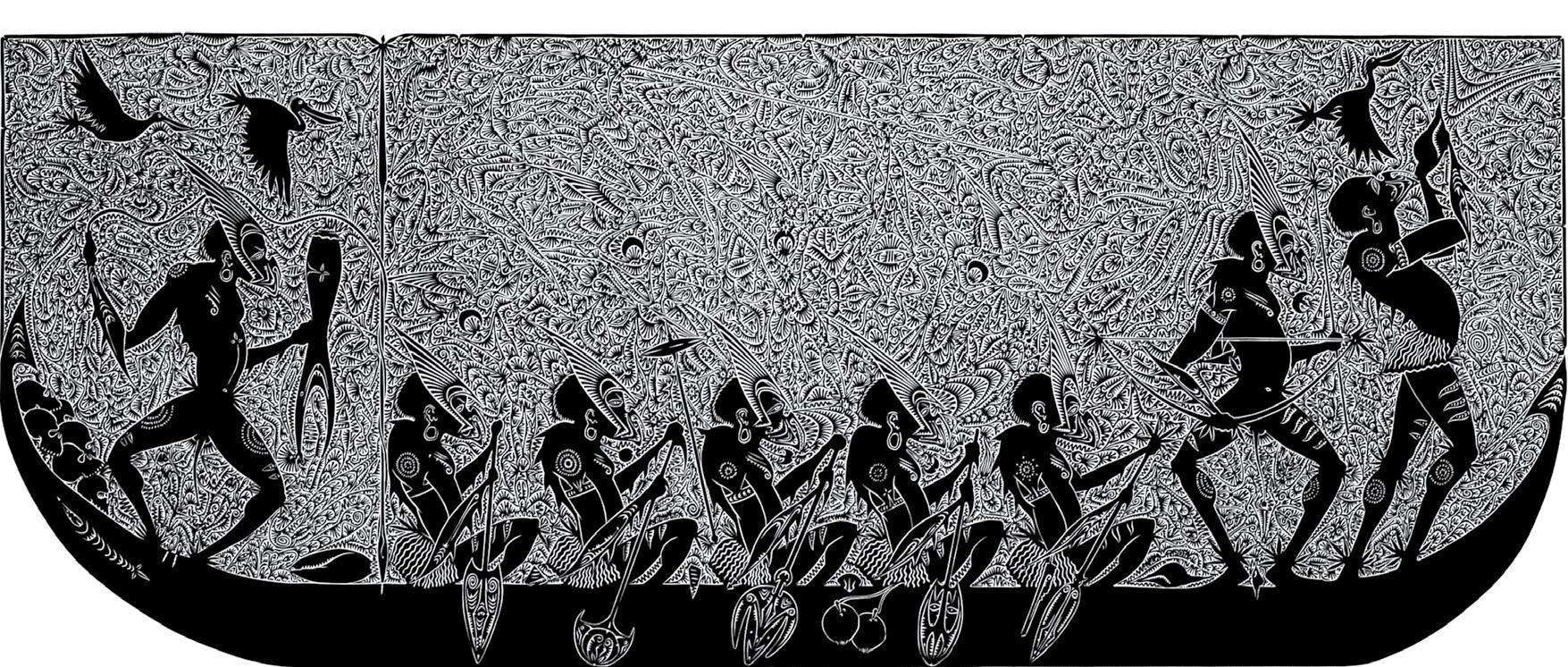

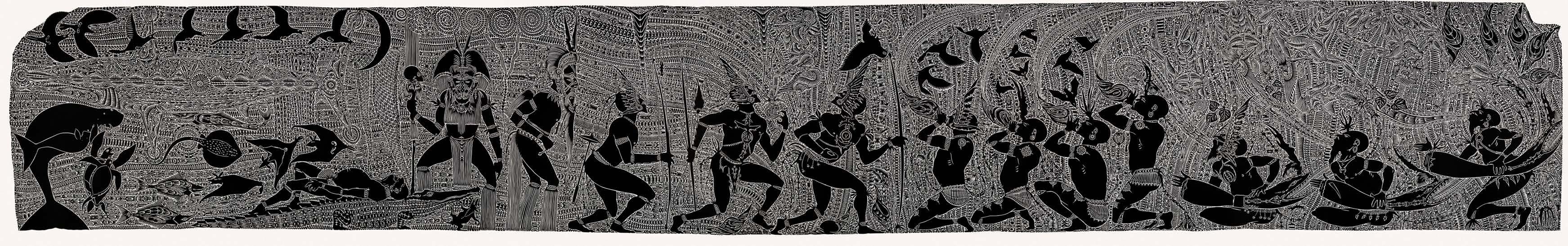

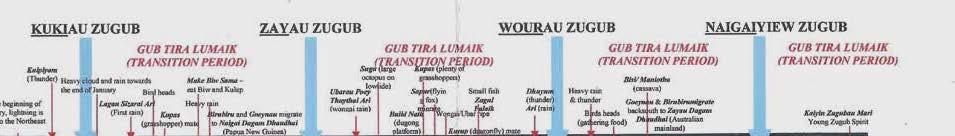

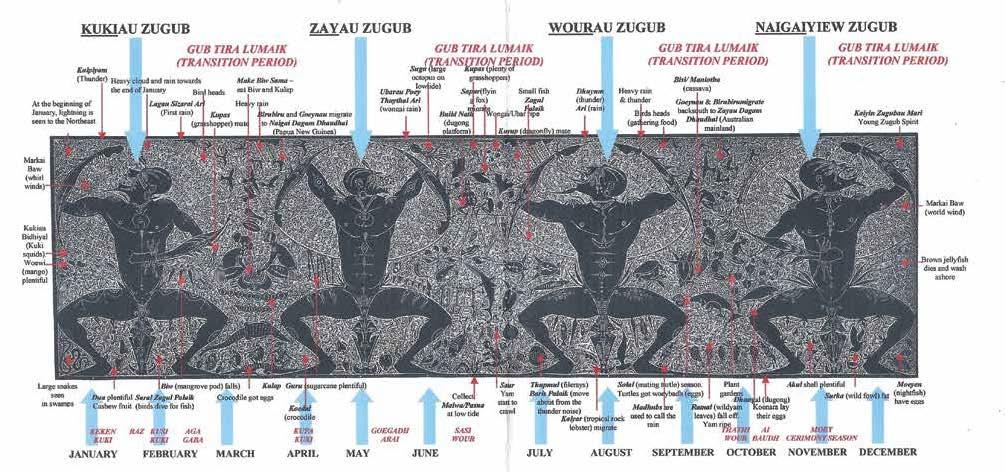

Tipoti’s print titled GubauAimaiMabaigal (windmakers), 2006 is virtually a calendar of nature’s rhythms over the course of four seasons that are determined by four different ‘characters’ of the wind. Tipoti has created a diagram that informs outsiders how the life cycles of flora and fauna are mapped into weather patterns and Zugubal activities. Stories about the activities of Zugubal in relation to nature’s habits help in remembering important survival knowledge.

In the diagram created for Zugubal 2006, Tipoti indicates different phases of the moon and star constellations used for celestial navigation. The two great Zugubal ancestors, Thagai and Kang, guide Zugubal in their canoe. An image of Thagai is embedded in the

rhythmic patterning. His left hand holding the spears is the Southern Cross. Thagai’s right hand is the constellation of Corvus.

The image illustrates how the gul or canoe, acts as a key symbol of connectivity in Zenadh Kes cosmology. It is the symbolic vessel for navigating all of the cycles of Zenadh Kes land, sea and sky, and spiritual life. Canoes maintain the Islanders’ seafaring lifestyle, although giant trees required for hulls were sourced from the east coast of Papua New Guinea in return for a trade in skulls and shells.

(Alick Tipoti, Artist Statement, 2015)

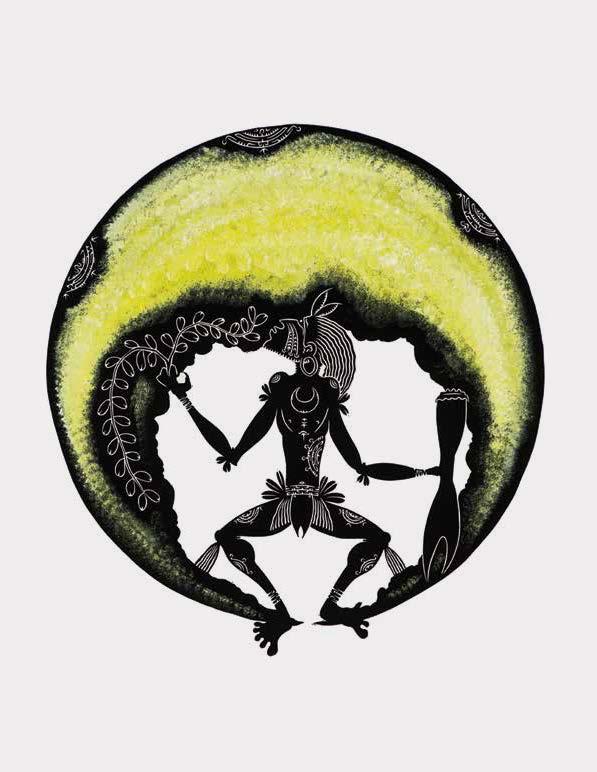

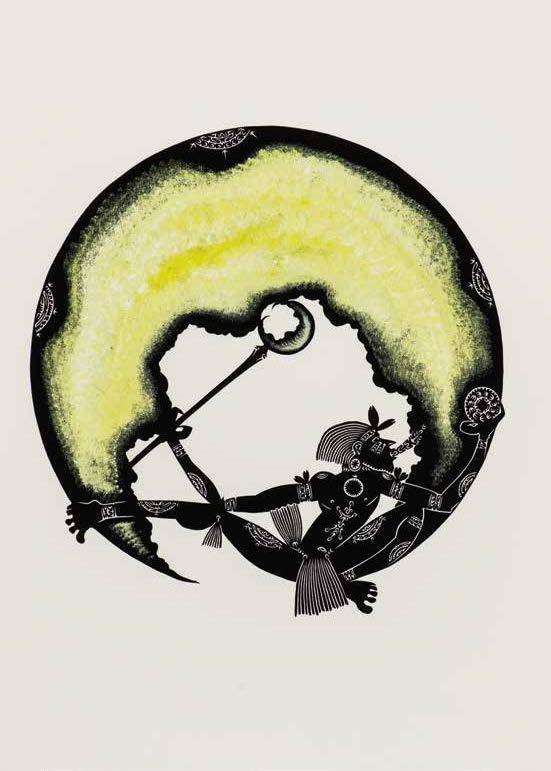

Celestial symbolism is a particularly powerful sign of connectivity. The span of the sky absorbs everything in its frame of reference. Tipoti’s three Kisay (moon) 2015 prints involve the spiritual presence of moonlight. Kisay is the maternal figure that protects Zenadh Kes at night. KisayDhangal 2015 depicts nocturnal rituals of hunting dugong. Below the nath (the hunting platform that is built in the shallow waters offshore), hangs the wooden charm of a dugong carved in wood. Tipoti describes the significance of the charm:

The hunter would carve the back of the charm hollow as if it was a canoe. He would then place some ancestral bones and some sea grass obtained from a dugong’s mouth he had previously killed. When the light of the moon shines on the charm the hunter waiting with his wap (harpoon) whispers a sacred chant that will lead the dugong to the nath. When there is no moon, a different chant is whispered to acknowledge the phosphorescence created by the dugong when exhaling underwater. (Alick Tipoti, 2015).

Moonlight that transforms in its absence into phosphorescence is represented in the image by an almost psychedelic yellow colouring. This colour has a rhythm of its own in the fizzing sensation of white bubble-like forms that arc around the image. Colour offers a different realm of abstraction in translating the presence of spiritual ancestors. There is vitality to the colour, or an aura, that makes it seem like a magic substance out of which the ancestral spirits emerge. Attention to Tipoti’s printmaking usually focuses on his carving techniques in creating the linoleum block. However, the colouring of the print is a separate process in itself. In other words, the colouring is a different phase of the image, or an image within an image. Tipoti collaborates with Cairns-based Master Printmaker, Theo Tremblay, in advancing the language of linocut printmaking in its capacities of cultural translation. Their experiments with the printing process have pushed the limits of linocut technique in terms of scale, sophistication and application, and the Kisay prints represent a new phase of this creative cycle.

Artistic innovation is also inspired by recent rock art studies in the region, as described in Liam Brady’s preceding chapter. Ancient rock art is a reference point for contemporary art around Australia. Arnhem Land bark paintings follow in the footsteps of local rock art galleries, and numerous Cape York artists regenerate the Quinkan figures from rock art located at Laura. Representations of petroglyph (engraved) rock art also appear in contemporary art from South Eastern Australia. Rock art imagery was traditionally retouched, refreshed or overpainted as an apparent method of connecting with the past. (Cole, 1995) This practice of retouching is no longer possible

in most cases due to heritage preservation, but connections with the past still occur through contemporary art making. The past loops into the present when rock art totems and symbols come into presence with a new generation of interpretation and innovation in art. Brady describes how totems are a connecting device, linking individuals and communities across western and central Zenadh Kes. Contemporary art’s application of totems and symbols from the rock art also connects people across time.

Tipoti’s recent interest in the baywa (waterspout) imagery exemplifies the practice of contemporary art reinterpreting rock art. Baywa are yet another device in connecting the spiritual and everyday worlds. Waterspouts are a reasonably common feature of tropical marine environments and have a fascinating, albeit short, life cycle of their own. They begin as a dark circle that forms into a spiral in the water. The water spiral vaporises, lifting and swirling into a funnel or spout before the whole process reverses. In Zenadh Kes cosmology ancestral spirits send dugong and turtles up to sea-hunters when they fail with their catch. In his baywa (dugong) 2015 print Tipoti decorates the funnel with triangle or vertical arrow shapes that appear in the rock art. The spout thus registers the transition of the dugong, that is both food and totem, from spiritual ancestors to sustenance for the hunters. There is a beautiful cyclic rhythm to the formation of the waterspout as it rises magically from the sea in a tower of vapour and then vanishes without trace. The symbolism of nature’s creative spiritual energy obviously was not lost on ancient artists, just as it inspires Tipoti today.

There is an interesting moral embedded in a world of total interconnectedness. It means that you are never totally alone, and that you are always in some way accountable to others. Tipoti’s slightly sinister umay (dog) masks represent the ever-watchful eye of this accountability. Umay belong to the Sesserae legend that is unique to Tipoti’s Badu Island community. Sesserae was the man who invented the wap (dugong/turtle spear) and would secretly enjoy the spoils of his innovation. Neighbouring villagers grew curious about the smell of delicious meats cooking and sent sorcerers, disguised as dogs, to discover his

secret. Sesserae transformed into a willy wagtail to escape retribution. He did not entirely evade punishment however, because he was henceforth condemned to never again take human form. If Tipoti’s umay masks have a sense of the austere sentinel about them, this is perhaps because they are watching you! Umay masks are now part of Tipoti’s dance choreography and represent a new chapter in reinterpreting ancient stories to sustain a moral framework for the present.

Intrinsic connections between Tipoti’s visual and performing arts gained international recognition when his dance troupe performed at the British Museum in London as part of their 2015 ground-breaking exhibition titled IndigenousAustralia: enduringcivilisation. The show was promoted as the first major UK exhibition to present a history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples through objects. It profiled a message of continuity, with the Director, Neil MacGregor, opening the exhibition with the claim that, ‘The history of Australia and its people is an incredible, continuous story that spans over 60,000 years’. (British Museum, 2015) This is very different to the story of looming extinction that pervaded museum displays of their cultures until recently. But contemporary artists like Alick Tipoti have made a significant impact in suffocating that story of loss with their dynamic aesthetics of connectivity. Tipoti’s performing and visual arts demonstrate that isolated objects in far away museums still have the silent beat of continuity with his people today, and demand their right to perform again.

References

Bergson, H. 1911, 1994, CreativeEvolution(L’Evolutioncréatrice 1907), New York: Dover Publications. 1994.

British Museum 2015, ‘Indigenous Australia: enduring civilisation’, 23 April–2 August 2015. Website: https://www.britishmuseum.org/about_us/news_and_ press/press_releases/2015/Indigenous_australia.aspx.

Cole, N. 1995, ‘Rock art in the Laura Cooktown region S.E. Cape York Peninsula’, QuinkanPrehistory:TheArchaeologyof AboriginalArtinS.E.CapeYorkPeninsula, Horwood, M. and Hobbs, D. (eds.), Australia: 51-70.

Tipoti, A. 2015, ‘Artist Statement’, Cairns: Cairns Regional Gallery.

Tipoti, A. 2004, NewworksbyAlickTipoti, Sydney: Australian Art Print Network.

GubauAimaiMaibaigal(Fourwinds) 2006

single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle 350gsm

81 x 300cm

Cairns Regional Gallery Collection.

Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Editions Tremblay NFP, 2012

Zugubal 2006

single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle 350 gsm

81 x 199.7cm irreg. (block) 106.5 x 220cm irreg. (sheet)

Courtesy of the artist

ApuKaz 2008

single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle 350 gsm, hand-coloured

220 x 114cm

Courtesy of the artist

Girelal 2011

single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle 350 gsm

120 x 825cm

Cairns Regional Gallery Collection.

Donation through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Editions Tremblay NFP, 2012

Mawa masks (x5) 2012

fibreglass, resin, fibre, beads, rope & feathers

210 x 90 x 45cm

Courtesy of the artist

AlickTipoti:Zugub,themask,thespiritsandthestars(filmstills) 2012

running time 70 mins

Courtesy Creative cowboy films © MMXII Creative cowboy Pty Ltd.

Baywa(Waterspout-turtle) 2014

single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle, handcoloured

198 x 125cm

Courtesy of the artist

Baywa(Waterspout-dugong) 2014

single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle, handcoloured

198 x 125cm

Courtesy of the artist

KisayGirer 2014

single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle, handcoloured

70 x 70cm

Courtesy of the artist

KisayMabayg 2014

single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle, handcoloured

70 x 70cm

Courtesy of the artist

gal 2014

single block vinyl cut in black ink printed on Hahnemuhle, handcoloured

70 x 70cm

Courtesy of the artist

Umay(dogmasks) 2014/15 fibreglass, pearlshell and cassowary feathers various

Courtesy of the artist

Warup(drum) 2015 fibreglass & string

80 x 200cm (approx)

Courtesy of the artist

Nath(huntingplatform) 2015 bamboo, rope & natural fibres

190 x 60 x 130cm

Courtesy of the artist

Sesere(Bushell) 2015 fibreglass

160 x 55cm

Courtesy of the artist

Lagalayg(face) 2015 fibreglass

170 x 165cm

Courtesy of the artist

Poenipaniya 2015 fibreglass, natural fibres, beads, resin, rope & feathers various

Courtesy of the artist

Dhoeris 2015 feathers, twine various

Courtesy of the artist

Gul(canoe) 2015 fibreglass, cassowary feathers, natural fibres and rope

60 x 240 x 200cm

Courtesy of the artist

Sally Butler, (ed.) 2015 Alick Tipoti, Zugubal: Ancestral Spirits, Cairns Regional Gallery, Cairns

ISBN 978-0-9757635-6-8

Photography: Michael Marzik

Video stills: Creative cowboy films

Map of the Torres Strait Islands reprinted with the permission of the Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art

Writers and advisors:

Dr Sally Butler (University of Queensland), Dr Liam M. Brady (Monash University), Andrea May Churcher, Janet Parfenovics and Janette Laver (Cairns Regional Gallery), Michael Kershaw (Australian Art Print Network) and Alick Tipoti

Catalogue design: Dinergy Intergrated Marketing Catalogue production: Kelly Jaunzems

© Cairns Regional Gallery

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.