Then join Business Leader. If you’re a CEO or founder with at least £3m in annual revenue, our community is made for you. This is where you’ll push through boundaries and gain access to the tools and support you need to grow faster and scale smarter.

• Join a CEO forum organised by revenue stage

• Use our proven nine-step framework to grow your business

• Attend exclusive events with experts and business leaders

• Receive targeted one-on-one coaching support

• Learn from our podcasts, masterclasses and case studies

Start your journey businessleader.co.uk/membership

Our celebration of the UK’s fastest-growing companies

How we did it

The largest and most comprehensive work ever done on growing companies

The businesses that added the most money

The top 10 The stories behind the winners

top 100 Vital statistics on the leading businesses

The unicorns Inspiring companies that hit a $1bn valuation

dive: financial services

companies making waves in fintech

Female trailblazers Women setting the pace from films to fashion

An investor’s point of view Why Caspar Lee backed this Growth 500 star

to last Established businesses that have stood test of time

Industry dive: retail & fashion

sportswear to hotshot handbag makers

on and off the pitch

In-depth stories of success and failure from the business world

The secret to Greggs’ success

Members Area

CEO Roisin Currie reveals the recipe that has made the bakery chain one of the UK’s biggest brands

66

Bringing power to the people

Lessons from leading the controversial construction of the new Sizewell C nuclear power station

72

How new Coke fizzled out

An ill-fated product launch by one of the market leaders shows how to deal when disaster strikes 60

84

Bumps on the road can be good for you

Jake Humphrey

86

Advice and inspiration on how to grow your business 76

Success, copied

In this book extract, we explore how businesses can thrive by using the concept of “copy and pivot”

How to avoid slip-ups when going it alone

Catherine Baker

90

Why it’s time to switch off reality TV Ed Smith

92

My Business Leader Secret

Advice on leadership from CEOs and founders

96

Bookshelf

The business books to read in the next few months

98

Member story

Natasha Lyons learnt from problems in her first business to make her second a success

100

Ask Richard Richard Harpin reveals how to grow your business

102

The importance of problem solving How member forums help you overcome challenges

Catherine Baker is the founder and director of Sport and Beyond, which applies techniques proven in sport to the business world. She is the author of Staying the Distance, vice-chair of the Dame Kelly Holmes Trust and chair of the consultancy O Shaped.

Tom Beahon co-founded Castore with his younger brother Phil in 2015 after failing to become a professional footballer. He has since built the sportswear brand, which is based in Manchester, into a global company worth more than £1bn.

Szu Ping Chan is economics editor at The Telegraph. A journalist for almost 20 years, she has previously written about economics, finance and business at the BBC and The Motley Fool. She is an expert on the UK economy and its impact on businesses.

Jake Humphrey is co-host of the High Performance podcast, which explores the stories and secrets behind successful athletes, coaches and business leaders. He co-founded the TV production company Whisper and was previously a TV presenter.

Caspar Lee rose to prominence with his popular YouTube channel, which had more than 6 million subscribers. He has used that experience to start several companies including influencer marketing platform Influencer, and the investment fund Creator Ventures.

Ed Smith is a former professional cricketer who was national selector for the England men’s team from 2018 to 2021 and will become president of the MCC in October 2025. He is director of the Institute of Sports Humanities and a prominent author.

Steven Swinford joined The Times as deputy political editor in 2019, becoming political editor in 2021. He has previously worked at The Daily Telegraph and been shortlisted for political reporter of the year at the National Press Awards four times.

EDITORIAL

Editor-in-chief

Graham Ruddick

Deputy editor-in-chief

Sarah Vizard

Online editor

Josh Dornbrack

Senior correspondent Dougal Shaw

Chief sub-editor

Mark Shillam

Sub-editor

Jayne Nelson

Design

Colm McDermott

Jochen Viegener

Cover illustration

Hit&Run

MEMBERSHIP

Enquiries membership@businessleader.co.uk

Become a member businessleader.co.uk/membership

EVENTS

Enquiries events@businessleader.co.uk

Register to attend businessleader.co.uk/events

COMMERCIAL

Enquiries info@businessleader.co.uk

© 2025 Business Leader is published by Business Leader Limited. Registered in England & Wales. Company no 08070514.

Business Leader has taken every care to make sure that content is accurate on the date of publication. The views expressed in the articles reflect the author’s opinions and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher or editor. This commentary is provided for general informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, tax, legal or accounting advice.

“It used to be what you know. Then it was who you know. Now it’s who knows you.”

This is what Amelia Sordell said at an event for Business Leader members with LinkedIn in May. Given how all the founders and chief executives in the room were frantically taking notes, the words seemed to resonate. The event was a masterclass in personal branding. Sordell has well over 200,000 followers on LinkedIn. It felt like the secrets to success on social media were being shared, where previously they would have kept inaccessible to all but a few.

Sordell’s point was that social media offers an unprecedented opportunity to promote your personal brand and business. So, use it. “Just f***ing post it,” were the words she asked everyone to take away with them. You will probably only get one measly “like” on your LinkedIn posts at the start, she explained. And that will be from you. But keep going.

This sentiment also came up in a recent podcast interview I did with John Roberts, founder and chief executive of AO World, the online appliances retailer. When I asked Roberts what the key to success was for AO, the answer was simple. “A refusal to fail,” he replied. “You find a way.” Is it really that simple, I thought. Well, not quite. Roberts didn’t just put his head down and plough on when things got hard. He sought advice and help from other founders and chief executives around the world. Roberts wrote to them by hand to ask for their time.

A couple of weeks after interviewing Roberts I spoke to Fergal Mullen, one of the leading venture capital investors in Europe. Mullen is the co-founder of Highland Europe, which has €3bn (£2.5bn) of assets under management and has backed some of the most promising businesses in the UK, such as Huel. He told me that when Highland is looking at what business to invest in, the factor it considers the most is whether the founder is “coachable”. Noticing my slightly confused face, he expanded on the point: “It definitely means they are good listeners, that they like to be challenged, they like to challenge us, they like to learn and they’re good fun,” he explained. Roberts, for one, certainly fits that bill. But I had another thought. The words of Sordell, Roberts and Mullen – people from completely different parts of the business world – come together to create an unstoppable force. If you can get people to know you, if you refuse to fail, and if you are prepared to listen and learn from the people you know to solve problems, then you can potentially overcome any challenge.

That, in essence, is what Business Leader is trying to do. If you are interested in becoming a member and attending our events, please check out pages four and five.

This is a special edition of our magazine. We shine the spotlight on the fastest-growing businesses in the UK. The stories behind these businesses are remarkable – and remarkably diverse. I was struck by the businesses that have bounced back from near-destruction during the Covid19 lockdowns to post record results. That is a story that hasn’t really been told in the UK amid the doom and gloom about the economy. Until now. Thanks for all your support and feedback. Please continue to get in touch at graham.ruddick@businessleader.co.uk

Graham Ruddick Editor-in-chief

Archive images from the stories that have shaped the business world

Netflix CEO Reed Hastings sitting in a cart of ready-to-be-shipped DVDs

Netflix has revolutionised how we watch films and shows at home. Founded by Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph in 1997, it started as “DVD rental by mail”, focused on online orders, no due dates and no late fees. It was not, said Randolph in a Twitter thread in 2023, meant to replace the video store.

But that’s exactly what it did. At one time the company synonymous with video rental, Blockbuster, employed more than 84,000 people worldwide and operated in excess of 9,000 stores. Many were found on British high streets and visiting one was a Friday-night ritual for many families.

But poor leadership, the 2008-09 recession and a failure to understand the shift to digital and streaming led to it filing for bankruptcy in 2010, eventually disappearing from the street. Blockbuster’s biggest Sliding Doors moment came 25 years ago. In 2000 and at the height of the dot-com bubble, Randolph and Hastings offered to sell their young and at the time struggling upstart to Blockbuster for $50m. The then-giant passed on the deal and instead chose to partner with Enron on a 20-year deal to create a video-on-demand service. Enron pulled the plug on the agreement a few months later over worries that Blockbuster couldn’t provide enough content for the service. Enron would declare bankruptcy less than a year later.

As for Netflix, after a successful pivot away from its mailorder service to streaming in 2007, it became one of the most visited websites in the world. It has more than 300 million global customers, a market capitalisation of nearly $500bn and revenue of $39bn in the last financial year. The company’s goal is to close this decade with a $1trn market cap and double its current annual revenue.

It ended its mail-order offering in 2023. As Randolph put it at the time: “DVDs are done. Thank you for your service.”

By Steven Swinford, political editor of The Times

A year into his premiership, many questions remain about the prime minister and what he actually stands for

Identity crisis

Starmer welcomes Ursula von der Leyen to a summit on bringing the EU closer, days after taking a tough stance on migration

Sir Keir Starmer is something of a chameleon. The man who once advocated the benefits of free movement and open borders has taken what is arguably the toughest stance on migration since Brexit.

In a Downing Street speech, he warned that Britain risks becoming an “island of strangers” – a phrase some left-wing Labour MPs compared to the rhetoric of Enoch Powell –and unveiled a blitz of measures to reduce numbers. His speech could just as easily have been given by Nigel Farage.

Yet a few days later he welcomed Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, to London for a landmark summit that brings the UK into its closest alignment with the EU since Brexit. The agreement was extensive, with closer ties on agriculture, trade, security and defence – and the promise of more to come. Future discussions will include a youth mobility scheme that will enable under-30s from the EU to live and work in the UK for a limited period.

From the outside, following Starmer can be a bewildering experience. There appears to be no singular ideological thread running through his politics, no lodestar by which he is guided. His critics accuse him of being “Starmer Chameleon”, a man who can change his views as it suits him, and there is some truth in the claim.

The prime minister’s U-turns are extensive and well documented. They include backing a second referendum and then backing Brexit; telling voters he would not raise national insurance and then doing exactly that; and insisting that transwomen are women, only to change his position when the Supreme Court ruled otherwise.

His allies argue that this is entirely the point. The prime minister is at heart an arch pragmatist, taking the positions that he believes will best serve the interests of the British people and, ultimately, the Labour Party as it seeks re-election in three years.

But the result is that Starmer has adopted a myriad of positions, some of which are directly contradictory, amid mounting questions about his political identity.

Take migration. In the wake of the local election results and with many of his MPs increasingly fearful of the threat posed by Reform, Starmer has unveiled the most radical crackdown on migration since Brexit. Foreign students will be allowed to stay in the UK for just 18 months after graduating without getting a skilled work visa, while universities face being charged extra for each student they enrol. Migrant workers will be barred from coming to the UK for graduate-level jobs, while all migrants will have to learn a higher standard of English.

With migration consistently in the top two issues for voters, Starmer’s approach makes sense. But it also cuts across his other priorities. Starmer has pledged to get economic growth going at all costs, yet business leaders are already warning of labour shortfalls, particularly in areas such as hospitality.

The health and social care sector has also raised the alarm amid concerns that there simply aren’t enough workers in the UK to sustain the sector. For a prime minister who has promised to cut waiting lists, this could pose particular problems. Starmer has effectively made

a choice, rejecting what is often described as the “Treasury orthodoxy” that higher levels of migration bring higher levels of growth.

But doing so, given the anaemic state of the economy, is a risk. Last autumn, chancellor Rachel Reeves delivered an archetypal Labour Budget with big tax rises and a big increase in public spending.

The parlous state of the public finances meant that Reeves found herself overseeing a challenging spending review in June, with deep cuts to non-protected budgets, and an even tougher Budget in the autumn.

With economists estimating that the black hole in the finances is now as much as £63bn, further tax rises and deeper spending cuts appear inevitable. That will be controversial. On welfare, Starmer has adopted an approach that bears all the hallmarks of those on the right of the political spectrum. He has announced significant cuts to disability benefits in a bid to stop the ever-rising cost of the welfare state, arguing that if people can work they should.

His own MPs are far from convinced. The prime minister is already facing a significant revolt from backbenchers, one which could see the government defeated when it comes to a vote on the package in the Commons. Eighty MPs have made their concerns known, with more expected to emerge.

During the local elections, ministers and backbenchers alike also reported that the backlash against the government’s decision to end universal winter fuel payments was overwhelming. They are imploring Starmer to reverse the cuts, which they describe as toxic and unnecessary.

Restraint is also the order of the day when it comes to public sector workers. Last year, in one of his first acts as prime minister, Starmer gave nurses, doctors, teachers and other public sector workers bumper pay rises in a bid to end industrial action. He was successful, but the reprieve was brief.

This time the prime minister and Reeves do not have the money for such significant pay rises, with offers of around 4 per cent. Nurses and junior doctors in particular are already threatening industrial action. All of which could see a Labour Party that is funded by the trade unions becoming the victim of a summer of discontent.

For now, Starmer is determined to stick to his guns and to maintain his fiscal rules, which dictate that he must balance the books. How long he is prepared to do so in the face of growing opposition on multiple fronts from within his own ranks remains to be seen.

Then there’s the sentencing review. As director of public prosecutions, Starmer established a reputation for being tough on crime. However, the parlous state of Britain’s prisons means that thousands of inmates will have to be released early from their sentences to stop the jails from being overwhelmed. The decision is one borne of necessity, given that prisons are literally running out of space. That reality will not stop Reform UK from exploiting the situation for all it is worth.

The broader problem of Starmer’s flexible approach is that it means he lacks a coherent narrative. Given the increasingly fractured nature of British politics, that could become an increasing problem.

By Szu Ping Chan, economics editor of The Telegraph

The evidence suggests that Britain is lagging behind on management skills, which makes training and support for businesses vital

The last van rolls off a British production line earlier this year.

At the heart of the country’s 15-year economic stagnation lies a chronic productivity problem

Bad managers are bad for the economy. Whether they’re micromanaging, taking credit for others’ work or failing to listen to people in their team, their behaviour has a big impact. A good manager usually means a happy worker, a bad manager a miserable one.

This is important because managers form the backbone of Britain’s companies. There are millions working up and down the country. Yet very few receive formal training in the tenets that make a good manager: effective communication, sensible decision-making or organisational abilities. And they are often asked to do thankless tasks such as performance reviews and HR compliance, as well as to keep the company on the road.

Rachel Reeves spends a lot of her time extolling the benefits of artificial intelligence and new technologies that she believes will help to grow the economy. The chancellor should spend a bit more of it getting back to basics. After all, good people make good companies. And while it might sound boring, having a generation of good managers will add more value to a company than any machine will. This is because at the heart of Britain’s 15-year stagnation is a chronic productivity problem.

Productivity – which measures output per hour worked – tells us how much the economy can grow without generating too much inflation. When productivity increases, so do profits and pay packets. That creates a virtuous circle of stronger growth, a bigger economy, rising tax revenues and lower borrowing.

In the end, people drive productivity through the investments they make and the tools they use. Even a fully automated factory is programmed by a human being.

The role of managers is to organise companies in the most effective way by hiring the right people, using their skills effectively, giving them the right tools and motivating them. Unfortunately, all the evidence suggests that, as a country, we’re not very good at management.

One of the most famous studies on the topic is by Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom and fellow academic John Van Reenen, who now advises the chancellor. They suggested that more than half the productivity gap between Britain and the US can be explained by poor management.

The Resolution Foundation think-tank recently issued a similar warning. “Only a small proportion of UK firms are as well managed as the best 25 per cent of US firms,” it said, with dire consequences for investment, productivity and growth. “Rising interest rates are biting across borders and bad taxes are found in many countries. Bad managers are, however, an area in which Britain stands out,” it noted.

It added: “Well-managed firms make better investment decisions, being demonstrably better at forecasting the growth of the aggregate economy and of their own firm.”

So where have we gone wrong? One of the problems is that we have so many of what the Chartered Management Institute coins “accidental managers”. A study several years ago estimated there were roughly 2.4 million people promoted into leadership roles on merit who were subsequently left to sink or swim.

While some excel, others become an example of the so-called Peter Principle, which says people are promoted

to their level of incompetence and then left to languish. The OECD warns that this is costing the economy £84bn a year and undermining Britain’s competitiveness. Surely there must be a better way.

For inspiration, we should look to the birthplace of the MBA. The US has made an industry out of professional management qualifications, and, in many ways, it has paid off. Bloom and Van Reenan consistently found that American firms are more efficient and hence more profitable than their British counterparts.

Why is that? American managers are better at motivating their staff. Targets are clear and performance is usually monitored. Talent is nurtured and success rewarded.

That usually leads to better paid and generally happier staff. “One reason for the predominance of US firms in management scores is that in the US, better-managed firms appear to be rewarded more quickly with greater market share, while worse-managed firms are forced to shrink and exit,” the pair wrote in one of the research papers.

Of course, the economic backdrop also matters. It’s much easier for bosses to find and manage the right team if they can hire and fire people more easily. I’ve always been surprised at how people can quit their jobs without serving any notice in the US. On the flip side, it means companies are freer to find staff that suit them and if it doesn’t work out, they can always start again.

By contrast, state-backed firms in countries with fewer incentives, such as China, perform less well, according to the research, while many firms in India simply do not have performance targets because wages are so low. As a result, both countries have poor management scores.

But there is one area where America does worse than the UK on management – in schools. US schools were found to be bad at promoting and rewarding high-performing teachers and retraining or getting rid of badly-performing ones. Bloom and Van Reenan blame this on strong union representation. Promotions are sometimes more to do with time served, making it more difficult to get rid of persistent underperformers.

By contrast, UK schools were highlighted as some of the best managed. The researchers pointed to education reforms introduced by Labour and embraced by the Tories that started academies. These are funded by the state but managed outside the public sector and local councils.

Governors have a greater say in how the schools are run, including the hiring of teachers, how much they’re paid and what is taught. It’s been a clear success story, raising attainment across the country.

So what should we do? There are lessons to be learnt both from other countries and other sectors on how to improve management. As a country, we need to start paying attention to them.

But you can do that on an individual level too. Are you running a business full of good managers or bad managers? Have you trained them, given them the support they need to listen to and empower their teams? If not, why not?

And if you’re an employee, do you have a boss you would describe as a good manager? If you do, the chances are you’re working at a successful company.

Who is really driving UK economic growth?

We all notice the official GDP figures and have a feel for which sectors are faring better than others. But who are the entrepreneurs and businesses doubling their annual revenues and creating hundreds, even thousands, of jobs? That is what we have looked to uncover in our inaugural Growth 500.

You may ask why Business Leader is doing its own growth index: there are several closely-followed lists already out there. However, few offer a sample larger than 100 companies. Fewer still look across the whole economy (most confine their scope to specific regions or sectors).

We are doing things differently. What you will find here in our inaugural Growth 500 is the most comprehensive look at which companies have increased their turnover by the greatest percentage over the past three years. Our trawl of thousands of documents filed with Companies House has reached into every sector and every region, setting out to build the most authoritative analysis of this kind available in the UK.

Our aim is to be definitive and inclusive. We have looked at companies with a turnover as low as £3m all the way up to FTSE giants. All we ask is that they have audited public accounts for the past three years. We know that

ambitious founders often sacrifice profitability to go big – so we haven’t excluded businesses that aren’t breaking even.

We also believe our time frame of looking at growth over three years strikes the right balance between giving a hotoff-the-press picture of what’s going on in our economy, while rooting out shooting stars who burn brightly but only fleetingly.

The scale of this work is probably its greatest strength. Our collection of 500 companies means if you’re not leading or working for one of these enterprises there’s a very good chance there is one nearby or operating in a similar field to you. Yes, you’ll see challenger banks, unicorn tech firms and biotech start-ups, but you’ll also find potato farmers, soft-toy makers and car dealers. There are even places for a Hollywood actor (Ryan Reynolds, Wrexham AFC, no 119 on our list), some legendary heavy metal rockers (Iron Maiden, Iron Maiden Legacy, no 172) and a pop star (Victoria Beckham, no 411).

Over the following pages you will find the business that came top of the Growth 500, a run-through of the top 10 and a list of every entry in the top 100. The full 500 will be published online. We have also picked out a collection of compelling stories that have emerged from the impressive numbers. Our inaugural Growth 500 has lessons for us all.

Robert Watts Compiler of the Growth 500 and The Sunday Times Rich List

The UK’s fastest-growing companies have lessons for us all but diversity of enterprise and raw ambition are the most striking features of our Growth 500, writes Robert Watts

It’s one thing to survive a global pandemic, another to thrive in its aftermath.

Business Leader’s first attempt to identify Britain’s fastest-growing 500 companies has inevitably been coloured by the Covid years of 2020 and 2021.

Should our rankings have excluded, say, travel agents and airlines who had to pull down the shutters or ground their planes during the pandemic and therefore started from a very low base when we came to measure their latest years of turnover?

We decided against this for two reasons. First, pubs, restaurants, music venues, theatres, high-street retailers and many other businesses were obliged to close for months during the dark days of Covid. If we stripped out the travel industry, where would we stop?

Second, to bounce back strongly after such a global crisis is an achievement worthy of recognition. All travel agents started from that low base, yet some have flourished while others have continued to struggle.

Excluding certain sectors would also counter the Growth 500’s ambition – to give readers the largest and most comprehensive rankings of which UK companies are growing most quickly. This inaugural dataset, compiled

by combing through thousands of filings at Companies House, compared annual turnover reported in the most recent accounts with those reported in the financial year three years before.

We did not ask for – or accept – submissions. We excluded UK businesses owned by foreign companies. Only firms that grew sales across the period counted.

Our list includes companies with turnovers as low as £3m over the latest reporting year. Hundreds of our entries are quiet achievers often little known outside their industry or home town. But you’ll also see much-heralded entrepreneurial success stories of recent years, including Revolut, Ovo Energy, Atom Bank, Starling and Octopus Energy.

“Our research also tells us a good deal about the UK economy and which companies are thriving in the post-pandemic world

Then there are entries with a flash of celebrity, such as Victoria Beckham’s fashion label, Olympic sailor Sir Ben Ainslie’s Athena Sports Group and the West End musical production empire built up by former stagehand Sir Cameron Mackintosh. One of television chef Gordon Ramsay’s ventures also made our final 500.

Few will have expected to see Iron Maiden Legacy, the company that receives the heavy metal veterans’ earnings from touring, music rights and selling merchandise.

Famed for their zombie-themed T-shirts and posters, the band’s accounts showed plenty of life. Turnover climbed to £27.5m in 2023-24, up 258.5 per cent across the three years.

Our research also tells us a good deal about the UK economy and which companies are thriving in the postpandemic world. Financial services, a sector ranging from retail banks to a gold-trading app, accounted for 101 companies – the most of any sector. Business services (71), travel & leisure (65) and construction (61) are also well represented. London (197) and the South East (59) dominate our list, together accounting for more than half the entries. The East of England (55), the North West (39) and South West (35) follow as the next best-represented regions. But all the regions of the UK are represented.

Not far off a third (154) of our 500 did not show a pre-tax profit in their latest accounts. Sportswear label Castore, Euan Blair’s ed-tech venture Multiverse and fellow unicorn Quantexa all showed a loss over the past year. Ambitious founders understand that investing boldly can be critical to growth. Breaking even is often a longer-term goal.

The research also tells us not to assume it’s only startups that can grow fast. Fifteen of our companies were founded more than a century ago. Three – the private bank C. Hoare & Co, the retail consultancy Herbert Group and the horse-racing group Weatherbys – have histories stretching back more than 250 years.

Our researchers found plenty of other impressive and surprising results. Sir Stelios Haji-Ioannou founded not one but two of our 500 companies: budget airline easyJet and hospitality group easyHotel. Fund manager Jeremy Hosking makes the cut not because of his investment expertise but due to his steam train side- hustle.

There are some striking hotspots. Fourteen of our enterprises are based in Cambridge. The Welsh town of Wrexham and Nottinghamshire’s Sutton-in-Ashfield punch well above their weight, each having three companies in our rankings. Their populations number around 40,000.

Wrexham is home to one of three football clubs to appear. Luton Town and Ipswich also feature.

Low-cost and luxury enterprises are both here too. There are seven McDonald’s franchisees and the group behind Michelin-starred London restaurant Quo Vadis.

It’s that diversity of enterprise that is perhaps the most striking aspect of the Growth 500. Yes, you will find founders with ballooning revenues thanks to AI, cutting-edge cybersecurity or innovative payment platforms. But you will also see pig farmers, housebuilders and car dealers. Ultimately, ambition is the most important raw material for high-growth ventures. These are the companies who have it in spades – and they have lessons for us all.

London is the most common base of our Growth 500 companies

Location by region

No 1 in our Growth 500 is a music promoter to the stars whose down-to-earth approach strikes a chord with industry greats

By Robert Watts & Dougal Shaw

If only Barrie Marshall had stuck with his plans of working as a civil engineer in local government he might have put together a pretty decent career working on building sites and planning bridges and roads.

Instead he has had to make do with travelling the world as an agent and promoter for Sir Elton John, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder and a dazzling cast of music industry greats.

Led Zeppelin. Status Quo. Lionel Ritchie. The Beach Boys. Cher. The Kinks. Whitney Houston. Annie Lennox. Otis Redding. George Michael. Joe Cocker. Pink. Sade. The Spice Girls. A giddying rollcall of stadium-filling acts he promoted over nearly six decades in the industry.

To Beatles legend Sir Paul McCartney, Marshall is “dear old Badger – the coolest promoter in the world” and a “total pleasure to work with”. The late, great Tina Turner would say he was “responsible for the success of my solo career”.

Now the man behind Marshall Arts, his playfully named business, has won another accolade: topping Business Leader’s inaugural Growth 500. Revenues at his Londonbased company have hit more than £68m, with annual growth topping 24,000 per cent over the past three years.

Part-owned by Los Angeles-based entertainment group AEG, Marshall Arts has helped deliver some astonishing tours. During the Covid lockdowns, shows were cancelled and Marshall’s revenues collapsed. But since then the business has soared to record levels thanks to tours such as Sir Elton’s Farewell Yellow Brick Road, a four-year extravaganza that took nearly $1bn at the box office.

Marshall fell into music promotion almost by accident. It started with the death of a friend called Ray Selway whose mother asked if Marshall would take on the job of promoting her son’s band, The Satellites.

“I had no experience whatsoever,” Marshall has said. “I was learning as I went along. I went over to Germany with The Satellites … booked gigs, scrubbed floors and did whatever was needed to keep us afloat.”

He began organising pub gigs for other bands, expanding to shows at American airbases, dance halls and seaside resorts. “I was totally immersed in records and gigs ... I couldn’t believe how music could be so exciting.”

He moved to work for Arthur Howes, then one of the biggest music promoters, who taught him the tricks of the trade. It wasn’t until his mid-30s that Marshall would set up on his own, opening an office in London’s Lower Regent Street in 1976. He had spotted a gap in the market that chimed with his own passions. “I felt the only field of music which wasn’t being promoted properly in the UK was soul and R&B … Luckily, I loved that type of music.”

Early clients would include Stevie Wonder and The Commodores, the band co-founded by the singer Lionel Ritchie, who remains on Marshall Arts’ books to this day. Many of his team have stayed on for years. They include Marshall’s wife Jenny. The pair grew close when she joined The Satellites as a singer. Team spirit is not the only lesson from Marshall’s story. Asked by music industry bible Pollstar for his business philosophy, he said: “Preparation is key,

advancing planning, and visits to meet the personnel we will be working with. It’s important to focus on all aspects and all departments.

“Crucially, attention to details, no matter how small they may seem. On show day they will become very relevant.”

Those founders who recognise the importance of humility will like his modest mantra. “It’s not about me, Barrie Marshall,” he once told Music Week. “I’ve never made a record or written a song. I don’t want to be famous. If I can put the act - using their music, image and artwork - in the right place at the right time, that’s what my objective is.

“Promoters have to remember one thing - we’re only the engine drivers. We’re not the person who gets off the train and entertains people. We’re there simply to support the act. As long as we remember that - and don’t have too much self-importance - things will run smoothly.”

In an age of emails, video calls and Slack, the importance of strong personal relationships can often be forgotten. The affection, as well as high regard, so many of his clients hold for Marshall is an important part of his company’s success.

In 2006 McCartney paid tribute: “Long may the Badger rule!” the ex-Beatle would say. Nearly 20 years later this star promoter remains top of the charts.

The accidental business

Wendy Wu founded her eponymous travel company almost by accident. Four years after moving away from China, she booked a trip for two back to her homeland.

At the last minute her travel companion had to pull out and so Wu placed a small ad in a newspaper offering the place as a 28-day tour of China, billing herself as a tour guide and promising some “hidden gems”. A mass of phone calls ensued, convincing Wu that there was a business to be built from organising holidays to China.

For years, London-based Wendy Wu Tours concentrated on selling trips to Asia but Covid obliged the business to explore new markets.

“Customers said to us: ‘Europe is open, can you please take us somewhere?’” Wu has said. “So we started to select really carefully unique places in Europe and the Middle East because they were already open – and China wasn’t.”

Those new destinations partly explain Wendy Wu Tours’ strong bounce-back from the pandemic. Annual turnover now exceeds £28m, up 19,431 per cent over the period we analysed.

Give it some gas

Unlocking the value in what others discard can make for a great business. Green Create harnesses methane-rich organic waste produced by agricultural sites including poultry farms and fish-processing plants to create natural gas and other products.

These can either be channelled into the domestic supply chain or used to generate electricity. Other byproducts from its facilities include liquid and solid phosphate fertiliser for arable farms and purified water that can be released back into local networks.

Green Create operates and owns sites in the Netherlands, Belgium, Mauritius and other parts of southern Africa. Earlier this year a partnership was announced between Green Create and a major US poultry producer to build 12 more sites across the country.

Financial difficulties at one of its plants in Kent have not hamstrung the company’s fast growth. Annual revenues at the London-headquartered group have climbed to £30.1m, an increase of 20,346 per cent over the past three years.

A chance encounter between Australian Scott Braidwood and Britishborn Jay Lakshman while holidaying in Egypt would lead to the start of this direct-to-consumer tour operator.

On the Go Tours’ first excursion in 1998 would be a tour of the pyramids, not far from where the pair had met that year. Priding itself on combining “culture and adventure with a lot of fun along the way”, this London-based travel company now offers trips to dozens of far-flung destinations, including Guatemala, Bhutan and Madagascar.

With packages offering adventures during the day but “a chilled beer poolside or a soft pillow at the end of the day”, On the Go Tours tries to strike a balance between authenticity and comfort.

There are now offices in Brisbane and Johannesburg as well as operations in New Zealand, Canada and the USA.

Grounded during the pandemic, On the Go Tours has now taken flight again, growing revenues to £17.1m during 2023 – a 16,078.4 per cent rise over the past three years.

This low-profile London outfit is billed as the UK’s largest textile-recycling business. It collects more than 400 million unwanted garments a year from homes in England and Wales on behalf of its partner charities.

After sorting and cleaning at its four processing plants, the clothes and footwear are exported to those in need living in Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa. This work is not only good for the planet but it also helps hard-pressed charities boost their income.

Green Global has now diversified into other eco-friendly areas such as helping business clients design, install and maintain solar panel systems to reduce their carbon footprint and cut their energy bills. More than 1,200 such systems have been fitted by the company so far.

It is also helping to deliver large and secure data centres and other IT infrastructure powered by renewable energy. All this drove revenues to nearly £7.7m in 2023-24, up 9,317 per cent over the past three years.

German national Martin Knuepfer founded Vosaio in 2009 after years working in the British travel industry. His London-based business-to-business agency specialises in designing and arranging bespoke tours across Europe and beyond, from school trips and business conferences to cruises and tours of the Vatican.

For around 95 per cent of its client programmes, Vosaio contracts directly with hotels, restaurants, tourist attractions and its other suppliers, thereby stripping out the cost of intermediaries and ensuring the company can more closely vet the quality of the services.

Turnover climbed to £39.5m in 2023, a growth of 5,998 per cent over the past three years. International travel of course collapsed during the global pandemic and that largely explains this phenomenal growth. Nevertheless, Vosaio is trading well above pre-Covid levels. Turnover in 2023 was 64 per cent higher than in 2019.

Knuepfer now employs teams across 25 countries and last May secured a multimillion-pound investment from BGF, the bank-backed venture capital investor targeting small and medium-sized enterprises.

High-profile and costly cyber attacks on some of the UK’s leading retailers in recent months will only increase the demand for experts offering more robust protection for corporate IT networks.

Paul Rose and Shannon Simpson already shared more than 50 years of experience safeguarding some of the UK’s most critical commercial and public sector digital networks when they set up their consultancy four years ago.

London-based Cyro Cyber, a spinout from the telecommunications infrastructure outfit Telent, has swiftly grown its revenues to just over £4.2m, a 7,899 per cent increase over the past three years.

Its services range from designing and maintaining secure digital networks to testing a client’s defences from hackers and malware. It even tests physical access to an organisation’s offices and data centres with a team of ex-military operatives.

The National Highways Agency, Network Rail, Royal Bank of Canada and the Police Digital Service are among Cyro’s roster of clients.

Star-studded film-maker

When Matthew Vaughn makes a movie, he can certainly assemble a superstar cast.

Sir Michael Caine, Daniel Craig, Julianne Moore, Ralph Fiennes and even pop queen Dua Lipa are among the household names to have starred in his catalogue of hits.

years, films produced by Vaughn are believed to have taken almost £1.4bn at box offices globally.

Turnover at Marv Studios, his London-based production company previously known as Ska Films, has grown by 3,782 per cent to £246.4m over the past three years. As well as revenues from current film projects, the company also receives a steady income from its back catalogue.

Perhaps best known for the three Kingsman spy capers, his more serious works have included the Sir Elton John biopic Rocketman and a surprisingly compelling dramatisation of the origins of the video game Tetris. Over the

Vaughn and his wife Claudia Schiffer each own half the shares in Marv Studios. The former supermodel has worked closely with her husband on his films for years. Their family cat, Chip, even had a starring role in their 2024 espionage comedy Argylle , garnering plenty of attention at the Leicester Square premiere.

Barny Rayburn organised plenty of trips to the continent in his days as head of modern languages at Derby Grammar School. After he finished teaching, he set out to help other schools pack off groups of students to Europe to improve their language skills. For 19 years, Rayburn ran his small business from his home with three staff. Then in 1984 he approached John Boyden, who until then had been his trusty coach driver, with an idea.

“Mr Rayburn quietly and fatherly-like told me that I was to buy the company, as he was retiring,” Boyden recalls.

Boyden and his wife Brenda obliged and have been running the tour operator ever since. Over the years the business has moved into organising ski trips as well as cricket, football and other sports tours to destinations including the US, Australia and India.

The 100-plus staff also put together concert tours for adult and school orchestras, choirs and bands to places such as Malta, Switzerland and the Czech Republic.

Rayburn Tours is this year celebrating 60 years in business and the 100-plus workforce can certainly raise a glass or two. Annual turnover has climbed by 1,853 per cent to £22.9m over the past three years.

A clever tour operator keeps a close eye on what its customers really like.

Some years ago, Miki Travel’s holiday reps noticed how Japanese holidaymakers touring the English countryside were enchanted by the yellow magnificence of a field full of rapeseed and would cluster around coach windows to take photos.

Before long Miki Travel would start offering tours of fields on the Gloucestershire-Wiltshire border where visitors could happily stroll among the bright-coloured crop, taking pictures to their hearts’ content. The trips didn’t just help banish the UK’s “grey, rainy image”, the tour operator said. They also proved a nice side hustle for farmers.

Founded in 1967, Miki Travel initially did well for Japanese tourists’ fondness for visiting the UK and the European mainland. The London-based business now has 41 offices around the world offering travel to more than 170 countries, operating a business-to-business service to travel agent clients.

Barcelona, Prague, Rome, Kuala Lumpur, Tokyo, Osaka and Bangkok are among the many destinations its website offers. The group prides itself on having “hundreds of multilingual staff”.

Revenues have grown by 2,951 per cent over the past three years, rising to £117.8m in 2023-24.

Inspiring companies that have hit a $1bn valuation with the founders still at the heart of their success

cut above thanks to robots

CMR Surgical is one of the most exciting businesses in the UK. One of its founders is Mark Slack, a South African doctor who worked in an academic hospital in Cambridge where he would treat patients and work on innovations. He was interested in how much keyhole surgery was being done versus how much could be done. Keyhole surgery reduces the risk of complications compared to open surgery and patients recover faster. However, less keyhole is performed than could be because it takes a high level of skill and it is difficult to train surgeons.

Slack thought robots could help, so he teamed up with robotics expert Luke Hares, as well as Keith Marshall, Paul Roberts and Martin Frost, to develop its technology. The story of CMR Surgical highlights the value of ecosystems such as Cambridge, where people can meet and skills come together. “The ecosystem that existed around us contributed hugely to the success of building the robot and getting it out there,” Slack says.

Its surgical robot system, Versius, is now in 186 locations across Europe, the Asia-Pacific, Middle East, Africa and Latin America. Revenues have more than doubled in the past three years, up by 122.6 per cent to £52.8m. And that growth looks set to continue. CMR Surgical recently won regulatory approval for the US – a significant step in its expansion plans – and it continues to innovate, recently obtaining approval for a new service that uses ultrasonic energy.

In August 2024, English band Massive Attack put on a one-day festival with a difference. The concert in Bristol was designed to be net zero, from how it was powered to the transport to get there and the food available. One of the companies helping to power the gig was Zenobē. It provided 19 battery units, as well as eight fully electric double-decker buses to shuttle people between Bristol Temple Meads station and the venue.

This is, on a smaller scale, what Zenobē is hoping to do to the UK – and global – economy. The company is developing electric batteries that can store energy generated by renewable power. These are not the batteries in a remote control or watch; they are more like small power stations. And they will be key to the energy transition.

“I really think it’s up to our generation to address some of the challenges that have been set up by previous generations through the use of fossil fuels,” says co-founder James Basden. “We have a unique opportunity to set up a carbon-free electricity power network and transport system that our children and grandchildren will benefit from.”

That unique opportunity is helping to power its success. Revenues are up 253 per cent over the past three years, hitting £53.6m in its most recent results. And its valuation has passed £1bn, suggesting there is far more growth still to come.

Upstart fintech aims high

Revolut’s rise has been dramatic. Founded just 10 years ago, it is now worth more than $45bn according to a secondary share sale last year – cementing its position as the most valuable private technology company in Europe and the UK’s most valuable fintech firm. It is also the most profitable company on the list, bringing in more than £1bn in its most recent results.

Revolut is the brainchild of founder Nikolay Storonsky, who was born in Russia but came to the UK aged 20. He worked as a trader for Lehman Brothers, losing around £500,000 when the firm collapsed in 2008.

The service which he founded with now chief technology officer Vlad Yatsenko offers app-based payments, undercutting mainstream banks with services such as fee-free foreign exchange. It has since pushed into other areas, including equity, commodity and cryptocurrency trading, helping to spur its growth.

Revolut was granted a UK banking licence last year, after a threeyear wait, and has just announced plans to invest more than €1bn in France, where it will build its western Europe headquarters as it targets yet more growth.

Storonsky is bullish on the company’s prospects. In 2018, he told The Times that “if we do what we do for another few years, we’ll be five times bigger than any bank”. It still has some way to go for that to be true, but with revenues growing by more than 230 per cent over the past three years, you wouldn’t bet against it.

Oliver Kent-Braham, one of the twins behind fintech unicorn Marshmallow, used his early success in tennis to build one of the UK’s fastest-growing companies

By Robert Watts

We are not long into our conversation before international tennis player turned tech founder Oliver Kent-Braham delivers his first winner. “Sometimes,” beams the elder of the 33-year-old twins behind the £1.6bn car insurer Marshmallow, “you need to get comfortable being uncomfortable.”

Meeting at this fast-growing unicorn’s offices, a few moments from London’s Silicon Roundabout tech hub, we have quickly landed upon one of the greatest dilemmas many ambitious founders face. When you’re trying to grow a company at the pace of a Djokovic serve, how much does the bottom line really matter?

“In some markets you will need to be exceptionally aggressive when it comes to attracting customers,” Kent-Braham explains. “You may be building the kind of software that can serve a lot of people, but you just don’t have the customers yet.

“That may mean that you run at a big loss because that monetisation will come later. Some of the biggest business success stories of the past 20 or 30 years haven’t been profitable for a long, long time.”

Uber, for example, took 14 years to break even. Marshmallow, which Kent-Braham launched with his brother Alexander and co-founder David Goaté in 2017, got there in half the time. The next set of accounts will show a profit, I’m told.

When the trio cheekily – and cheaply –started their venture from the lobby of a Virgin Active gym near London’s Embankment Tube station, did they set out to build a big insurance player, one that could shake up the somewhat fusty world of no-claims bonuses and third party, fire and theft?

“We wanted to build something big and impactful, but really we had identified a problem. We thought someone should go and solve that issue – and why shouldn’t that be us?”

That market failure was the high price people who move to the UK from overseas often pay for car insurance. Premiums for these motorists were often 50 per cent higher than for British-born drivers. Marshmallow’s founders felt that more sophisticated profiling by state-of-the-art IT would make it possible to price these groups more effectively, potentially offering significant savings. “We also

had a belief this customer group would grow because the fertility rate within the UK is low. There is an increasing retired population and a decreasing working population, so it looked like the UK would try to solve that problem in part by migration.”

What followed was not an overnight success story. The brothers waited 18 months to sell their first insurance policy. Over the next eight months it would still be a novelty whenever they got an alert notifying them of another customer sign-up.

Turnover jumped from £7.7m in 2019 to £37m in the following year, doubling to £79.3m for 2021. Attracting investment at an early stage – something many founders are wary of – was critical to Marshmallow’s success.

“The companies that inspired us 10 years ago were those that tended to raise capital to grow,” Kent-Braham says. “To achieve scale as an insurer you need lots of capital, and so that was always going to be part of the equation.”

Taking on investment, he stresses, does not necessarily mean losing control. “We believe that founder-led, management-led companies, especially private ones, are in a position to outperform because they can be longer-term focused.”

Marshmallow’s investors include Passion Capital, Hedosophia and Scor. The twins retain almost half of the shares. A fundraising in September 2021 secured a $1.25bn (£930m) valuation and unicorn status. Another investment round in April this year put a $2.1bn (£1.6bn) price tag on the company.

Rising sales help explain this year’s higher valuation. Revenues climbed to £184.1m in 2023, growth of 358.2 per cent over two years, sufficient to put Marshmallow into the top quarter of Business Leader’s Growth 500.

More than half of customers remain drivers who have moved to the UK from overseas, but the proportion of British-born motorists is rising. “These are normally people who have a bit less driving experience, lower credit scores and move around a lot – attributes that they share with our customer base.”

It’s not just Marshmallow’s customers that have similar attributes, of course. What’s it like running a company with your identical twin? “Alexander and I have a deep trust and understanding of each other. We really believe

There’s no better time to invest in a conversation.

Whether you’re growing your business, preparing for an exit or planning your post-sale future, we can support you at every stage of your journey.

Get in touch to start building a plan that helps you achieve your ambitions. brewin.co.uk/businessowners

The value of investments can fall and you may get back less than you invested.

“With sport, you lose a lot. Sometimes you don’t have your best day, sometimes the other person is better than you. The next day you still have to get up, go to training and play another match

in the same mission for this company.” Born to a Jamaican father and British mother, the siblings grew up in the affluent west London suburbs of Barnes, Richmond and Surbiton. They both attended the Surrey private school Reed’s, as did four-time Wimbledon semifinalist Tim Henman.

By their mid-teens the Kent-Brahams were both representing Great Britain at tennis. After sixth form, the pair headed to the University of the West of England in Bristol. Apart from a year at different companies, the twins have always worked together.

“Alexander and I are very similar,” Oliver chuckles. “So many companies fail because the founding team falls out. Alexander and I are very aligned for what we want to achieve here for a very long period.”

So how do they divide up their responsibilities? “I honestly see my job as making sure Alexander can be very focused internally,” the elder of the pair continues. “Alexander is very urgent, he’s a good manager, he’s very diligent. Anything that’s more external is what I tend to pick up.”

This means Oliver concentrates on the outward-facing aspects of the business, such as working with the chief legal officer and chief finance officer. Alexander is more involved with product, software engineering and human resources. Despite those delineations, Kent-Braham emphasises that “in fast-growing

companies things need to change rapidly all the time”. “We’ve only ever reorganised too late,” he says. “Changing the structure of the organisation, changing the reporting lines … it can’t make sense to have the same structure when you are 20 people as it does when you are 200.

“You either accept that things need to change or you are going to be a bit of a burden on a company. Be prepared to change things. If it’s wrong, you can always change it again. You should be proud whenever you’re changing things, it’s progress.”

This optimistic, resilient approach must have served the Kent-Brahams well on the tennis court over the years. Alexander still plays, while Oliver says he has been enjoying the fastgrowing racquet sport padel.

“With sport, tennis especially, you lose a lot. Sometimes you don’t have your best day, sometimes the other person is better than you. The next day you still have to get up, go to training and play another match,” he says.

“That’s what life is like – and running a company too. You can still enjoy the process, even if you lose. The most successful people in history have been unsuccessful at things. Sport really teaches you to get up again after you’ve lost, but after a while you do come to see that people who work their hardest do the best. The world is not perfectly meritocratic but if you give it your all, you have much better outcomes.”

Sounds like the ping of another ace.

These three companies are taking centre stage in the booming fintech industry in the UK

A big believer in best practice

Richard Davies says he is a magpie. “I love to see what others have done,” he explains. “I may have experienced it firsthand, I may know someone who has been there, or I have read about what has been done. I am a big believer in trying to assemble what best practice looks like.”

But don’t be fooled into thinking that Davies is some kind of traditionalist. The next thing he says is eye-opening. “I am also a big believer that [best practice] often doesn’t look like traditional management theory. I think a lot of that stuff is wrong. Over the last decade companies have very rarely followed traditional management practice as they have been built.”

What makes this comment particularly noteworthy is that Davies has been at the centre of the blossoming UK fintech industry and played key roles at three of the companies on the Growth 500. He was chief executive of OakNorth, chief operating officer at Revolut and is now chief executive at Allica Bank, the digital bank for small and medium-sized businesses. He arrived at Allica in 2020 to what was effectively a blank

sheet of paper. Allica had just won a banking licence from UK regulators and it had investment from venture capital firms. But its founder had departed and Allica had loaned just £5m to businesses.

Since then, Allica has been one of the fastest-growing companies in the UK. The company’s appearance in the Growth 500 reflects its stellar performance. Our data shows its revenue has grown by 268 per cent, or £213m, across the period we measured to £292m. What’s more, Allica also reported healthy pre-tax profits of £29.9m in its most recent financial year.

Allica has grown quickly, says Davies, by “doing a dramatically better version of what already is out there”. By that, he means that Allica is trying to offer a far better service to medium-sized businesses in the UK than the traditional high street banks.

“Sadly, this space has been vacated by most of the major banks,” Davies says. “They’ve been cutting back on all their client-facing staff. They haven’t really invested properly in the digital services for this segment. I’d say part of the reason we’ve seen such fast growth is that the bar is fairly low.”

But, as his initial comments demonstrate, Davies is also thinking about how to run a business in a different way to others. He recommends the book The Geek Way: The radical mindset that drives extraordinary results by Andrew McAfee as something he has learnt from.

“One of the things I think a lot of large companies, but also many start-ups, get wrong is that execution is such an important thing and iterative execution is super crucial,” Davies says. “The view that you can get decisions right via lots of upfront analysis and brainstorming I think is fundamentally wrong.

“Get the thing live. Get it working with some clients, then iterate it very fast with those clients to develop it. That ability to execute – to get something live, to get feedback and to iterate – is often what sets companies apart. It is very different to the classic process of ivorytower thinking.”

The speed of Allica’s progress since Davies arrived there five years ago shows he is on to something.

Payhawk’s co-founder and CEO Hristo Borisov experienced at firsthand the headache of managing corporate expenses – and decided to do something about it. After roles in engineering and product management, he quit and, needing to cut unnecessary expenses, cancelled all his subscriptions.

He found it so hard to do so that he thought there might be an opportunity there. So he founded Payhawk, in 2018, to enable companies to manage their spending, from corporate cards and expenses to subscriptions, more easily.

The company was rejected by more than 60 venture-capital firms before getting funding. But within six months of launch it had customers in 16 countries. Recent growth suggests Borisov is definitely on to something. Revenues are up 1,681 per cent in the three years we monitored, hitting £10.9m in its most recent annual results.

Boosted by building from scratch

In 2017, ClearBank became the first new clearing bank in the UK for more than 250 years. Its USP, says founder and former CEO Charles McManus, is that it has been able to build its offering from scratch, unencumbered by the legacy platforms that limit its rivals. That means it can focus on being efficient, cost effective and fast, all areas the other clearing banks are criticised over.

A clearing bank is one that verifies a financial transaction, ensuring for both the payer and the payee that everything goes according to plan. Services include Faster Payments, Chaps and Bacs payments, with the market dominated by the big four of Barclays, NatWest, Lloyds and HSBC. ClearBank counts Chip, Tide and Wealthify among its customers, which total more than 240.

Its 1,175 per cent growth rate over the past three years has been fuelled by expansion following the approval of its European banking licence. To fund that, it received £150m from investors including Apax Digital, and is spending around £70m on its European moves. It became profitable in the UK for the first time last year.

McManus, who is now a non-executive director, believes key to its success has been a focus on product, which is critical to business success. “You really must make sure there is a market – and you can compete and win. Your product has got to be brilliant, and you have to understand what your customers are buying off you.”

Standout performers that generated the biggest absolute increase in revenue over the past three years — not in percentage terms, but in real money

Spreading its tentacles overseas

In less than 10 years, founder and CEO Greg Jackson has powered Octopus Energy from plucky green start-up into the UK’s largest domestic energy supplier.

There are now almost 13 million household meters measuring electricity and gas served by Octopus, analysis by Cornwall Insights has found. This works out at almost a quarter of the market and a touch above British Gas, until now the dominant player.

Jackson, a member of Greenpeace since his mid-teens, initially set up and ran businesses making mirrors and trading property. He did not start Octopus until his early 40s.

“We became Britain’s biggest energy supplier by relentlessly delivering better services, lower costs and more innovation,” Jackson says. “We’ve

invested heavily in technology to deliver this rare combination of rapid growth and outstanding service.”

Raising hundreds of millions in capital from investors, including former US vice-president Al Gore, is a critical part of the Octopus story. This gave Jackson the financial firepower for a succession of game-changing acquisitions that were also partly made possible due to the energy crisis that began when Russian President Vladimir Putin launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022.

Later that year, Octopus was able to snap up Bulb, until then the UK’s seventh largest supplier with 1.5 million customers.

A year later the company bought Shell Energy Retail, the fuel giant’s UK household electricity and gas arm. This brought in another 1.3 million customers.

Octopus’s tentacles have also spread overseas by buying German green energy outfit 4hundred and France’s Plüm Énergie. Jackson now runs a group operating across 26 countries. Annual turnover has ballooned to £12.4bn, up 194 per cent in three years.

Stephen Fitzpatrick set up Ovo in 2009 with a vision to shake up the UK’s domestic energy market, then long dominated by six large players.

It must have seemed quite the gamble. The son of a Belfast grocer, Fitzpatrick had until then been working in investment banking and his entrepreneurial endeavours were largely limited to a property freesheet he ran while studying at Edinburgh University.

Nevertheless, he and his then-wife Sophie sold their home and used £350,000 of the proceeds to set up their Bristol-based green energy supplier.

It took 11 years before they hit the big time. Shortly before the Covid pandemic began, Ovo bought FTSE 100 giant SSE’s domestic energy

business for £500m. The acquisition saw Fitzpatrick’s customer base leap from 1.5m to 5m – and suddenly Ovo was the UK’s third largest energy supplier.

“He went from David to Goliath with one deal,” one industry chief executive says of Fitzpatrick.

Although now overtaken by fellow new market entrant Octopus, Ovo’s revenues have continued to rise, partly due to the recent energy crisis. Over the past three years, sales growth is up 750 per cent, with annual profits exceeding £1bn. Fitzpatrick still controls the company, despite selling stakes to Mitsubishi Corporation, Mayfair Equity Partners and Morgan Stanley Investment Management.

An admirer of Sir Richard Branson, Fitzpatrick shares the Virgin billionaire’s eclectic mix of entrepreneurial pursuits. The Ulsterman has floated his flying taxi venture Vertical Aerospace on the New York stock exchange and dabbled in Formula One. He has also bought Kensington Roof Gardens, a London nightspot previously owned by Branson.

These are the 100 fastest-growing companies in the UK. The table below shows their growth rate over the period we measured and their annual revenues in the final year.

We spotlight some of the women leading the UK’s fastest-growing businesses

Making waves in a man’s world

Sophi Horne is quickly making a name for herself in the world of yachting. Born in Norway but raised in Sweden, she is the designer behind the electric powerboat RaceBird, which is used in the championship racing E1 Series, as well as the founder of Seabird Technologies.

to spend hours in bed, she worked on one of her two tech companies – a platform where people could hire power boats. She wanted to add electric foil boats but couldn’t find any so she thought she would design one herself.

Things really took off when Alejandro Agag, chairman of both Formula E and E1 Series, said he would back her project – and then asked her to develop race boats. She turned her hand to that, while at the same time helping development of E1. That has helped to drive revenues to £12.5m, a 620-per-cent increase over the past three years.

Her journey into yacht design started as a side hustle at school. She won a few awards and, aged 18, was hired by a mega-yacht company. She left to go into banking but soon quit to focus on her passion. The inspiration for Seabird came when she was recovering from Lyme disease. Forced

Horne admits it can be a man’s world, particularly in the marine industry. The key to success, she says, is finding the right backers. “As a woman, you need to find people who believe in you, respect you and let you do your thing without coming in and taking over,” she told Fortune magazine.

Victoria Beckham needs little introduction. A fifth of the Spice Girls, the best-selling girl group of all time, and married to one of the world’s most famous footballers in David Beckham, she is one of the most famous and photographed women on the planet.

Alongside this fame, she is also a successful businesswoman. She had a passion for fashion and made her debut as a model at London Fashion Week in 2000, before designing her first fashion line for Rock & Republic in 2004. When she left Rock & Republic, she launched her own denim label dVb Style, before expanding into eyewear.

However, it is her eponymous label that has put Beckham on the Growth 500. Founded in 2008, it was initially known for dresses but soon added separates and luxury handbags to the collection, as well as denim, eyewear and fragrance. In 2011, she won Designer Brand of the Year at the British Fashion Awards.

Revenues at the company are up 118 per cent over the past three years, hitting £89m in its most recent accounts. But in an interview with Nicole Kidman for Vogue Australia she admits she was “naive and innocent” when she began working on her label and if she knew then what she knows now, she might not have had the “courage” to launch it.

Sister has had a bumper few years. Founded in 2015, the independent production company is behind hit TV shows including The Split and This is Going to Hurt for the BBC, Black Doves and Chernobyl for Netflix, and Broadchurch for ITV.

Its three female founders are heavyweights of the media industry. Jane Featherstone was the chief executive of Kudos and co-chair of Shine UK; Elisabeth Murdoch, daughter of Rupert, who founded Shine Group; and Stacey Snider, who was previously chair and CEO of 20th Century Fox, chair of Universal Pictures and co-chair and CEO of DreamWorks.

Featherstone believes its independence has been “critical” to its success. Speaking to Variety magazine, she revealed: “We’ve expanded, we’ve grown and we have investments, but [Sister] can still partner with anybody and work with any talent and create our own deal structures.”

The challenge, of course, is getting a share of the increasingly tight budgets in the media landscape. But its results would suggest its focus on independence, storytelling and stories with international appeal is paying off. Revenue has increased by 680 per cent, to £207.1m, over the three years of our analysis, as it looks to expand both internationally with the opening of its US studio and by taking stakes in smaller businesses.

Those who have generated £250m or more in annual revenues for the first time, making them large companies

Bright idea

Bayford is backing Raw Charging, which has EV chargers at Thorpe Park

All aboard for tech transformation

We’ll never know quite what the founders of Bayford Group would make of the technologies this Yorkshire-based business has been investing in over the past decade.

A group of former soldiers from Leeds who fought in the First World War set up the business in 1919, naming their outfit after the Hertfordshire village where their military service officially came to an end when they were “demobbed”.

Bayford began by selling and delivering coal. By the 1960s the Wetherby-based group had moved into oil distribution and petrol

retail, before pushing into property and hospitality. Jonathan Turner led a family buyout of the other shareholders just over 20 years ago and has since driven the company into new areas.

Bayford has become a major shareholder in Raw Charging, a fastgrowing network of electric vehicle chargers now found at shopping centres, National Trust properties and other family-friendly attractions such as Thorpe Park and Chessington World of Adventures.

Turner has also led the move into software used in smart meters, heat pumps and other green infrastructure through an investment in Jumptech, a Cambridge-based tech firm. Plus, Bayford has a 30 per cent holding in Fulcrum, a Sheffield-based busiess helping design and maintain data centres and electric vehicle charging points. It’s all a long way from coal but it is paying off, with revenue growth at 145 per cent over the past three years.

Jo Bamford could have spent his career working at JCB, the construction equipment behemoth built up by his father Lord (Anthony) Bamford. But instead of selling those iconic yellow diggers, the younger Bamford is building up a stable of green businesses under the HydraB banner.

So far, he is best known for buying the bus-maker Wrightbus in 2018. Many of the Northern Irish manufacturer’s vehicles are now powered by either hydrogen or electric batteries.

Oxford-based HydraB also wraps in hydrogen distributor Ryze Power and Hygen Energy, an H2 producer. “I first started talking about hydrogen in 2019, and ever since then we’ve been steadily building a network of companies who can get this industry on its feet,” Bamford has said.

“Now we are focusing on the infrastructure to bring it all together … we are putting the ecosystem in place to help businesses realise that hydrogen is a vital part of the UK’s energy mix.”

His father certainly seems to agree. JCB has so far invested more than £100m in a range of hydrogen combustion engines at its plant in Derbyshire. Its growth also shows its success, with revenues up 193 per cent to £290.9m over the past three years.

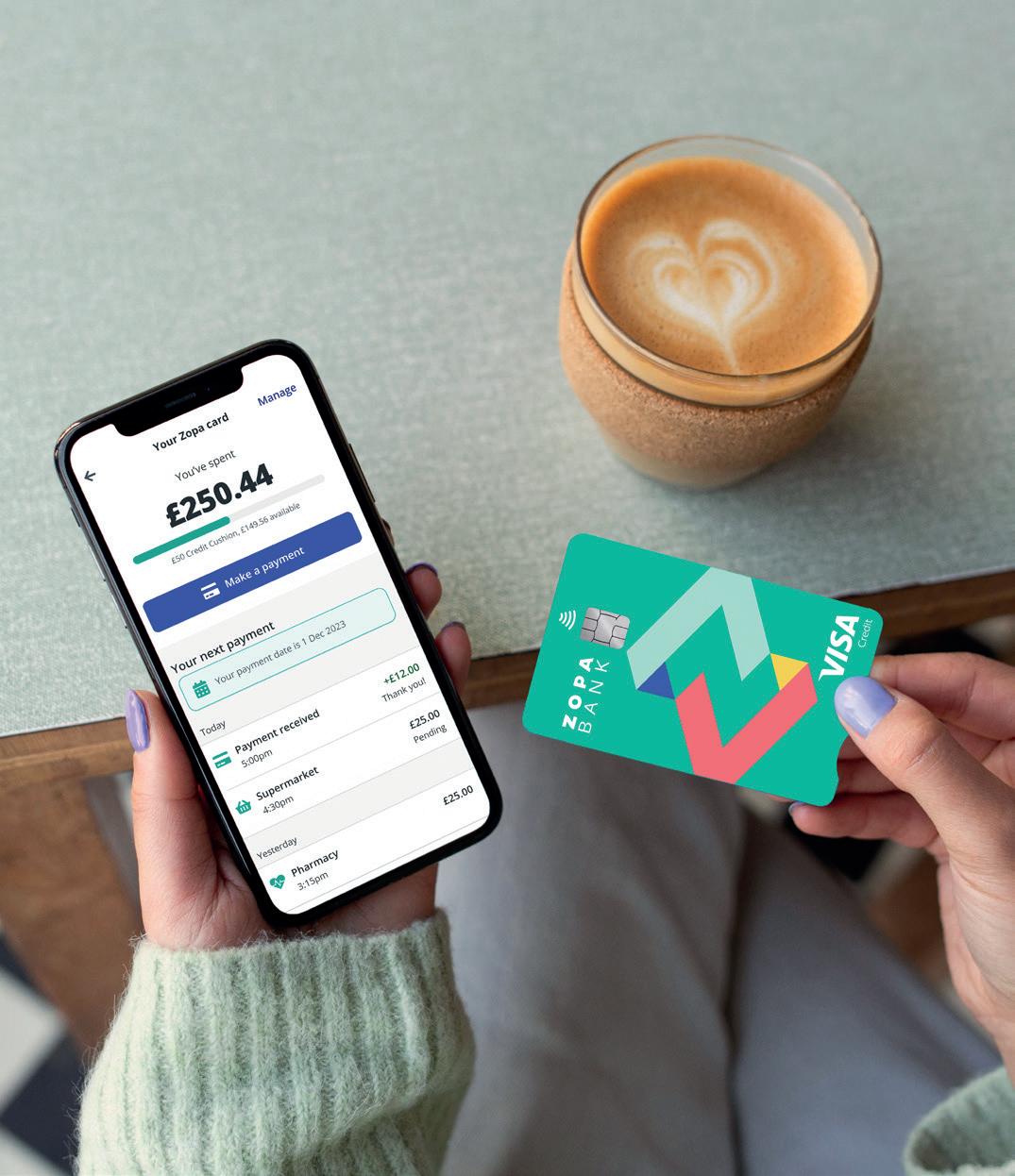

Few companies have pivoted quite as well as Zopa. Starting out 20 years ago as the world’s first peer-to-peer lender, the London-based fintech wound up this operation in 2021 after transforming itself into a digital bank – jumping through all the hoops necessary to win a full banking licence from the Financial Conduct Authority.

This change of direction was spearheaded by chief executive Jaidev Janardana, who feared that the tough regulatory environment was making it hard for peer-to-peer lenders to grow.

Janardana’s timing is interesting. Zopa began rolling out personal loans, credit cards and car finances in June 2020, soon after the start of the Covid pandemic. By the end of last year, the bank had around 1.4 million customers, lending more than £10bn and taking in more than £5.5bn of deposits.

Partnerships with Britain’s largest electricity supplier Octopus Energy and the retailer John Lewis have helped boost revenues. Growth over the past three years has hit 674 per cent, with revenues at £588.9m.

Zopa, which owes its name to an abbreviation for the lending jargon “zone of possible agreement”, plans to launch current accounts later this year and Janardana is on a mission to grow the customer base to 5m by 2028.

A stock-market float remains on the cards.

By Caspar Lee, co-founder of Influencer.com and Creator Ventures

Natural deodorant brand Wild went from start-up to one of the fastest-growing companies in the UK and a sale for £230m

Green appeal

Wild’s refillable products chime with a world moving away from wasteful packaging of the kind highlighted by Whale on the Wharf, a new art installation at Canary Wharf in London, created from recycled plastic waste found in the ocean

“They managed to turn deodorant into something you could give your sister for Christmas without her being offended

The founders of the natural deodorant brand Wild recently sold their business to Unilever in a deal thought to value the company at £230m. Freddy Ward and Charlie BowesLyon founded the business less than six years ago. That is rapid success in a space not known for moving fast – or for £200m-plus exits.

My cousin and investment partner Sasha Kaletsky discovered Wild five years ago when it was raising seed capital. Although we weren’t keen on direct-to-consumer (D2C) products, we thought Wild could be successful, so we invested and brought in relevant creators to do the same. A few years later, once we had raised our own fund in Creator Ventures, we wrote a large follow-on cheque as the company continued to grow.

The Wild story has great lessons, from launch to exit. To start with, Ward and Bowes-Lyon saw that while reusable products were becoming more common in daily life, the bathroom was still dominated by single-use plastics. They figured that by introducing more sustainable, refillable deodorants made from natural ingredients, they could carve out a market that would interest a growing segment of environmentally conscious consumers.

What is even more impressive is that the first product didn’t really work. When it launched in 2019, there was a lot of negative feedback. Instead of ignoring it, Ward and Bowes-Lyon paused, reworked their idea and came back in 2020 with a better version. That’s not easy to do. Most brands don’t recover from a bad first impression, but Wild did.