Jae Krueger

PAGES 12-13

Amira Alquraishy

PAGES 18-21

Brenden Rowan

PAGES 28-33

Seyla Ray

Andrew Berger

38-41

Linnea Sundquist

PAGES 44-45

By Katherine Hill

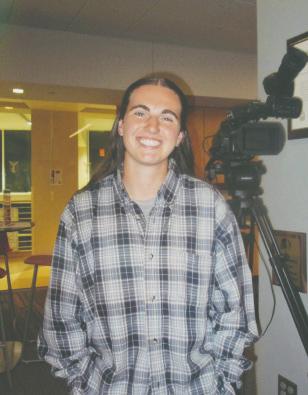

Trinity Rea

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

JESSICA BERGFORS

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

TRINITY REA

CO-ASSOCIATE EDITORS

MACI HOSKINS

LINNEA SUNDQUIST

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

BRENDEN ROWAN

ASSOCIATE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

ANTONIA LIAKAS

PHOTO EDITOR

OLIVIA MCSPADDEN

DESIGNERS

AVA BOWER

ERICA HARTMAN

ANNA HOWARTH

ANTONIA LIAKAS

CHRISTIAN MASON

OLIVIA MCSPADDEN

BRENDEN ROWAN

RAQUEL RUFFIN

EMILY STALLINGS

WRITERS

AMIRA ALQURAISHY

ANDREW BERGER

TATUM HARRIS

KATHERINE HILL

JAE KRUEGER

SIDNEY MILLER

SEYLA RAY

RADLEY RICHMAN

TRINITY REA

BRENDEN ROWAN

LINNEA SUNDQUIST

PHOTOGRAPHERS

ANDREW BERGER

JORDAN BOX

KADIN BRIGHT

OLIVIA MCSPADDEN

TRINITY REA

REAGAN SEXTON-GODSEY

ADVISER

COREY OHLENKAMP

By Jessica Bergfors

“Drive slowly, I know every route in this county. Maybe that ain’t such a bad thing,” is a lyric that has etched itself on my heart. Noah Kahan’s song, “Everywhere, Everything,” shows the intensity of love you can have for someone until the day you both die. It wasn’t until I came to college that I associated this song with people and places I now call my second home.

Most seniors in high school understand the impending, sometimes sinking, feeling of searching for colleges. Some kids have known exactly where they want to attend since they were five years old, others have had lists of possible schools since sophomore year of high school. I didn’t start my search until the beginning of senior year.

It was at a college fair on a random Thursday night where I first heard about Ball State University. I had no idea Muncie, Indiana, existed, let alone where it was located. Growing up in northwest Indiana, near Chicago, I rarely ventured to the central part of the state. I grew up rooting for the Bears, not the Colts. I went to concerts at the United Center, not Gainbridge Fieldhouse.

One thing I did know was that I wanted to go into journalism. I’ve subconsciously known this since middle school, when I dressed up and did a project on Nellie Bly, an American journalist who was a pioneer of investigative journalism, for my school’s “living history” fair.

My mom told me about Ball State’s journalism program and encouraged me to look more into the school. As I went to different college booths at the fair, taking any free merchandise that I could, Ball State’s

giant red pamphlet stuck in my arm. I applied to a handful of other schools, but only toured two: Illinois State University and Ball State. I was waiting for that feeling. The stomach twisting, fluttery feeling in your gut when you know you’re where you’re meant to be. Driving over three hours for my tour, I sat in the car anxious that I wasn’t going to feel that at Ball State.

Finally arriving on campus after hours of trying to figure out the desolate farm roads and a lot of wrong turns, I was in Muncie.

I think everyone in my life at that time knew Ball State was where I was ending up, and I got that feeling at the end of my tour in the Art and Journalism building. In the back of my head, my decision was made.

Over the past three years, August has become my favorite month, and that feeling of hope never left. Instead it only grew.

It grew as I met people who will stand by my side on my wedding day. It grew as I joined student media, writing and designing stories about my community. It grew as I learned about people’s history and childhood, and how they were so different from mine. I’ve met people from places I’ve never heard of and hold their history in my heart. I’ve memorized the Muncie routes and roads. I’ve visited my friend’s hometowns, admiring where they grew up. I’ve left claw marks on everything I love here.

When deciding the theme for Ball Bearings this year, the idea of history was constantly brought up. Ideas like roots, traditions and memories were scattered in messy black writing across a whiteboard.

through my pages of notes, I found myself thinking more about story ideas that related to history. My one-page Google Doc quickly became eight pages with bullet points and topic ideas. It wasn’t until this past summer that we finalized “The Archival Edition,” an edition about history and the archives that make up our community and world. This idea has expanded into stories like how language is an archive and how print media has changed and its importance.

The history of people and places is a vulnerable topic. History holds power. It holds knowledge, and it holds the future. History is kept alive through archives, physical or digital and sharing experiences. We wanted this edition of Ball Bearings to show that.

My appreciation for the history of Muncie and the community is still growing. I hope that through reading this edition, you can share the same understanding and love behind not only the Muncie and Ball State community, but for the archives that shape your life.

For the past three years I’ve been a part of Ball Bearings, these topics were always mentioned, but never settled on. As I scrolled

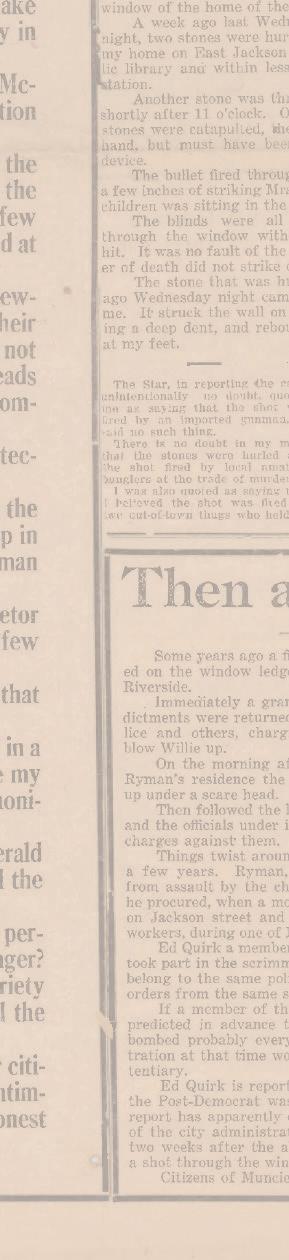

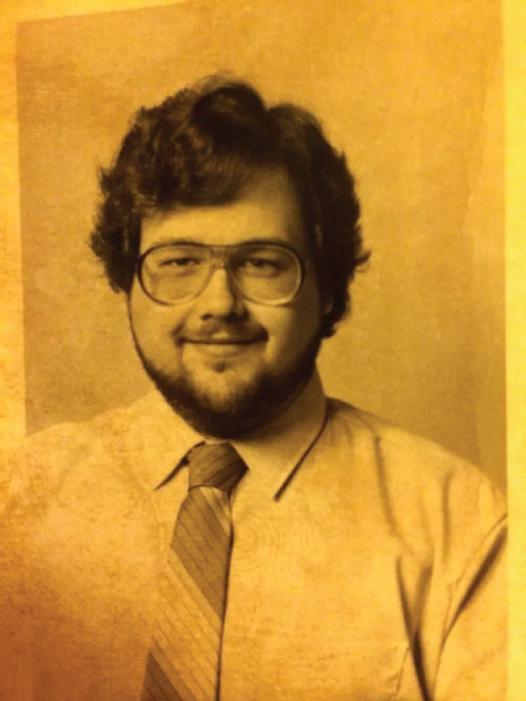

By Jae Krueger

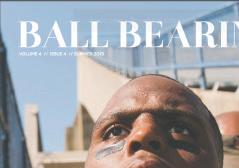

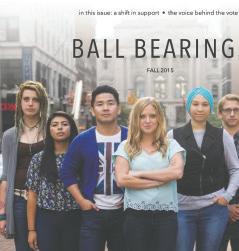

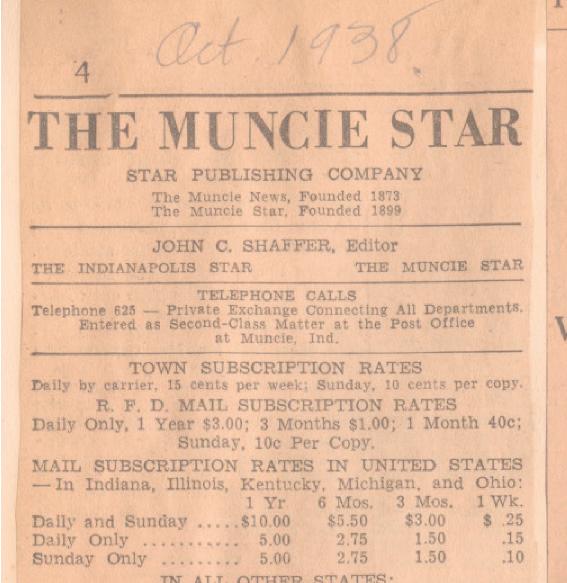

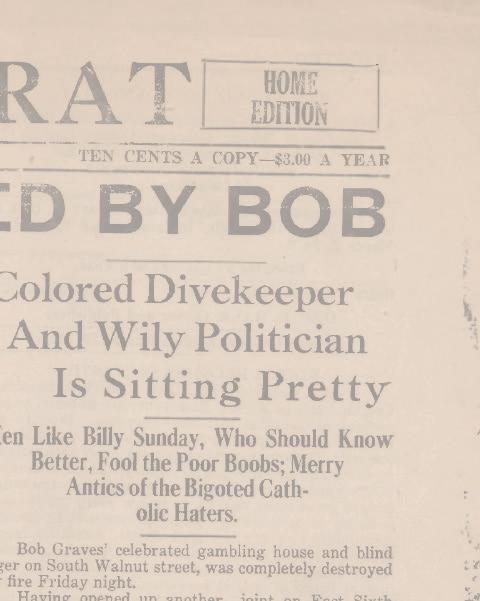

In 1976, “Verbatim” was published as the first student-run magazine at Ball State University. The name would eventually change to “Expo” a decade later, but it wouldn’t be until 2006 that Ball Bearings would start as an online magazine, with “Expo” merging into the new publication, according to Ball State University’s School of Journalism and Strategic Communication.

Since the beginning of Ball Bearings, it has published a range of stories. However, it wasn’t very well-known until Miranda Carney took leadership in the fall semester of 2015 as editor-in-chief, alongside her Executive Editor, Kaitlyn Arford.

“A lot of what I did that senior year was educating people about our magazine. Both in terms of ‘Hey, this [magazine] is pretty cool,’ and also, ‘Hey, you should get involved, because we really need your help,’” Kaitlyn said.

Kaitlyn said the previous process had been really unorganized, describing it as “disjointed in vision.” She said it hadn’t seemed like anyone had the necessary resources or oversight they needed for success.

Alex Kincaid, the Editor-in-Chief for the following school year, said sticking to specific themes had not been as huge of a “local interest.” With the magazine’s revamp, they hoped to focus on national issues.

Miranda said they intended to overhaul the process. She had a specific vision for Ball Bearings, stating that if anyone across the country were to pick up this magazine, “they should be interested in it, whether or not they know what Ball State is.”

For the Fall 2015 edition, the theme

It was just less reporting on college trends and more so, ‘Here’s the bigger national trend and here it is through the lens of Ball State students and [Muncie’s Community].’”

was Millennials. Executives wanted to expand from Ball State’s campus, still hoping to highlight relatable stories for both an on- and off-campus audience. At the time, millennials were the next generation heading into the workforce, according to Miranda.

“Obviously, we don’t want to leave the community out of it completely,” Miranda said. “It was just less reporting on college trends and more ‘Here’s the bigger national trend and here it is through the lens of Ball State students and [Muncie’s community].’”

Ball Bearings’ members worked on several stories for that semester, as they produced weekly digital stories alongside the printed magazine. Digital themes would often branch into smaller topics beneath the theme of Millennials, touching on topics like sexuality, gender, finance, and education.

As the digital themes kept evolving, Miranda wanted to prioritize the theme of Millennials. Members began changing the magazine’s process, introducing new concepts of magazine production and design into the edition.

“We developed a ‘front of book’ section,” Kaitlyn explained, as one of the examples. “Some of our younger journalism members could do a lot more reporting, and then the features went to more upperclassmen.”

For the following semester, the theme was “Our Money, Their Secrets.” This theme focused on college spending; Ball Bearings taking a deeper dive into select programs benefitting from students’

A LOOK BACK AT HOW BALL BEARINGS MAGAZINE’S STORYTELLING AND DESIGN HAS EVOLVED OVERTIME.

tuition. Kaitlyn recalls researching Ball State’s mental health facilities and finding financial struggles. The department hadn’t been doing as well as the athletic program, an effect mirrored by several other programs.

“We knew that ‘Our Money’ was going to be the biggest edition,” Kaitlyn said. “That’s the one we want[ed] to win awards. We want[ed] it to be ironclad. We want[ed] to know all the details.”

Despite the magazine’s broader stories during the previous semester, Ball Bearings’s executive team decided they needed to intensify the magazine’s audience on campus. They had to gain students’ interest in reading the magazine.

For the first time, Miranda and

Kaitlyn worked together to produce something unique.

Ball State’s president had stepped down at the time which shifted the discussion from university spending to finding a new president. Using this topic, they set up a Q&A with the interim president of Ball State, in front of a live audience.

“For me, it was culminating,” Miranda said. “That was a big area of growth for me, because I never would have imagined that I would have done something like that.”

Brad King, Ball Bearings’ advisor at the time, recommended the idea. It was something that national magazines did regularly, and there wasn’t any reason Ball Bearings couldn’t do it, Kaitlyn said.

Brad had just started working as Ball Bearings’ advisor when Kaitlyn and Miranda took control, having experience in teaching long-form journalism and even writing for WIRED, a well-known online magazine focused on technology, business, science and culture.

He no longer works at Ball State, but Miranda and Kaitlyn would often go to Brad for suggestions and advice for magazine production.

“He worked really hard with us,” Kaitlyn said. “For us to understand exactly what we needed to do.”

Alex Kincaid took over as editor-inchief the following semester in 2016.

With this change in leadership, direction fell toward a national topic: political division.

This edition was inspired by the upcoming 2016 presidential election, something executives felt was being discussed across campus. This issue was known as “Why We Think We’re Right.”

“Our entire time focused on this newfound division that the country was seeing with the campaigning for the election,” Alex said.

The semester’s stories focused on a range of political topics, even looking into the cognitive processes and reasoning for the reported division within the country.

“I would say the biggest transformation happened with the transition to [Miranda and Kaitlyn],” Alex said. “We had a new advisor, and he really helped us take [Ball Bearings], which was always more of a local interest, and mirror what a national magazine would look like; localizing [a national theme] to [our] audience.”

She explained that they carried on with the process that the previous executive team had put into place.

“I wish we had that structure in place before my senior year,” Kaitlyn said.

“Looking back, I think I would have benefited as an undergrad to have that opportunity to do some of the reporting Ball Bearings was doing at a young age.”

Similar to the live-audience event that Ball Bearings hosted for “Our Money, Their Secrets,” the fall’s political issue advertised the magazine through a panel discussion about civility and politics. With around one hundred people attending this panel, Alex explained that they drew people to this event for the political discussion. They took that chance to advertise Ball

Bearings, as everyone left with their own physical copy of the magazine.

Soon after, changes in technology began impacting the magazine. The Spring 2017 issue was titled “Our Digital Destiny,” which looked into the impact of social media. Staff even reported on AI, a topic people didn’t know much about at the time.

“It’s kind of interesting that more than about ten years ago, we were looking toward that, and now we’re kind of living it,” Alex said, discussing their story that looked into when artificial

intelligence would cross the threshold into becoming human.

Currently, Ball Bearings magazine continues to focus on stories that can direct national trends towards a local audience. Fall 2024, the Civil Issue touched on community homlessness, addiction and more. Spring 2025, the Elemental Edition covered topics like food insecurity and recycling in Muncie.

According to Ball State University’s School of Journalism and Strategic Communication, the online versions

of Ball Bearings have won National Pacemaker Awards from the Associated Collegiate Press in 2012, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2020 and 2024.

The Ball Bearings website archives published content dating back to Sept. 2009, and will continue to serve as Ball State’s student-run magazine for news, trends, features, photo essays and more.

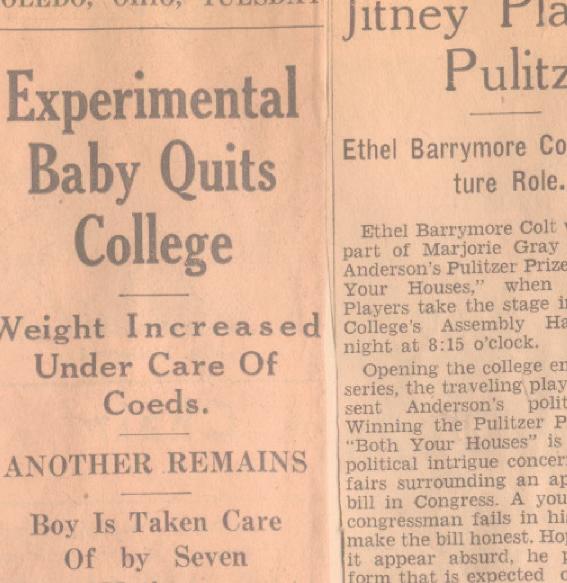

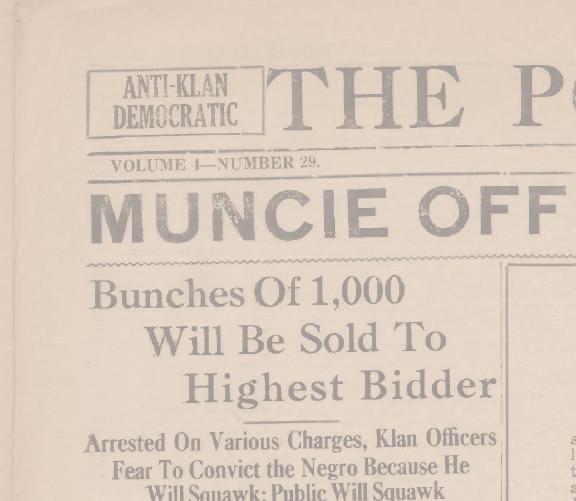

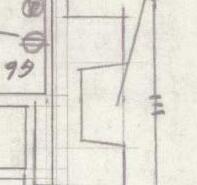

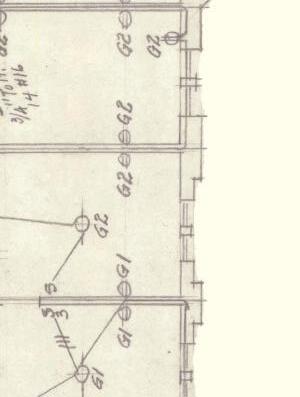

With the fi rst building on Ball State’s campus opening over a century ago, the area has gone through many modifi cations to become what it is today.

Prospective students are starting their journey where Ball State started [its] journey. It’s just a very connected moment.”

- Andrea Sadler, Associate director for the o ce of undergraduate admissions

Frank A. Bracken Administration Building Oct. 14 and students studying on the lawn in front of Lucina Hall May 1969. Kadin Bright, Ball Bearings Photo; Ball State University Digital Media Repository, Photo Provided; Ava Bower, Ball Bearings Photo Illustration

By Sidney Miller

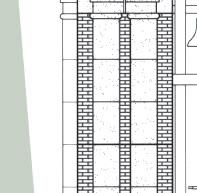

Revitalizing The Village has been a large construction focus of Ball State University. With seven different projects scheduled to be worked on until 2028, according to Ball State University, the campus landscape is steadily changing. But over its century of existence, the school has consistently built buildings, torn them down and repurposed them.

The light yellow bricks and blue accents to the administration building in The Quad stand out compared to the rest of Ball State’s heavily red-brick campus. Finished in 1899, the building opened to house the Eastern Indiana Normal University. At its opening, it offered sixteen different departments with a tuition of $10 per 10week term, according to a 1899 pamphlet issued by Eastern Indiana Normal University.

At the time of its opening, the building was praised as an “architectural triumph,” according to a 1968 Ball State News, now the daily news article. Inside the new establishment, classrooms were found on the first floor, equipped with chalkboards and furniture. Each section of the building had a designated academic department and faculty offices.

From its opening in 1899, the institution had gone through five name changes and a brief closing between 1907 and 1912, when it became the Muncie Normal Institute. A year later it was renamed to the Muncie National institute until 1917 when debt forced it to close, according to Ball State University Libraries. The site was purchased by the Ball brothers later that year and given to the state, marking the beginning of Ball State in 1918.

From the 1920s and 30s, multiple other

academic buildings were completed and opened for the university. The Burkhardt building was completed in 1924 as the “science hall,” while the original campus library was finished in 1926, which is now known as the North Quad building.

While renovations were being done on the administration building in 1964, the school used two houses that they had purchased as temporary office spaces.

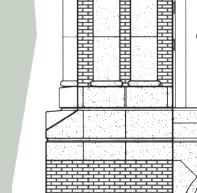

Near the administration building is Lucina Hall, which houses nine different campus offices and departments, with the building acting as a Welcome Center. The building is the first place prospective students visit, and is one of the oldest buildings on campus.

Construction was finished on Lucina Hall in 1927, originally a women’s dormitory for the Ball State Teachers College. It was built to house 110 girls and included a dining hall, which was later relocated to behind Elliott Hall upon its opening.

The building is named after Lucina A. Ball, the oldest sister of the Ball family. Lucina started working as a teacher and eventually became the first secretary of Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, according to Minnetrista Museum and Gardens.

Next to the women’s hall was Ball State’s first residence hall, Forest Hall, which was torn down to make additions of 100 rooms to Lucina Hall in 1941.

During the 1973-74 academic year, the interior of the building was converted from a residence hall to an office building. Twenty years later, another round of renovations were completed. During these changes, the admissions office was relocated from the administration building to Lucina, where it currently resides.

LaFollette Complex Memorial Oct. 14 and Ball State University students reading in LaFollette Residence Hall April 6 1967. Kadin Bright, Ball Bearings Photo; Ball State University Digital Media Repository, Photo Provided; Ava Bower, Ball Bearings

Andrea Sadler, an associate director for the Office of Undergraduate Admissions, spends her days working in the historic building. For her, welcoming future students in the former residence hall is special.

“Prospective students are starting their journey where Ball State started [its] journey,” Andrea said. “It’s just a very connected moment.”

Andrea and the Welcome Center staff value the historical space and hope to maintain it in the best shape they can.

“We’re constantly straightening the lobby. We’re constantly making sure the restrooms are cleaned,” Andrea explained. “… I feel like we’re the caretakers of the history that’s in this building.”

Faith du Toit, the Welcome Center and group visit coordinator, works closely with Andrea and shares the same passion for the building.

“Just seeing the history and how far we’ve come, that’s kind of a motivator for us,” Faith said. “This is where we came from, we’re the start of campus, but then also the start of a lot of these families’ journeys that they’re starting as well.”

Andrea and Faith both agreed that students’ connection with Lucina does not end after admission but continues through the other services provided in the building.

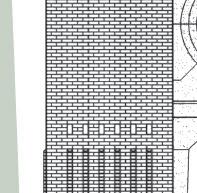

Two years before Lucina was completed, Ball Gymnasium was the newest building on campus, with construction finishing in 1925. The gym was a gift from the Ball family, which resulted in the university’s name being changed to Ball Teachers College, Eastern Division Indiana State

Normal School in 1922, according to Ball State University Libraries. One hundred years after the gymnasium complex was completed, it is no longer Ball State’s main arena. In the 1960s, Irving Gymnasium was finished, taking Ball Gymnasium’s spot for home athletics events. The school continued to update its athletic facilities, completing Worthen Arena 30 years after Irving’s opening. Currently, it serves as Ball State’s official sports arena with a capacity of 11,500 fans, according to Ball State University.

Just seeing the history and how far we’ve come, that’s kind of a motivator for us.”

- Faith du Toit, Welcome Center and group visit coordinator

Irving Gym became part of the Jo-Ann Gora Recreation Center, which was completed in 2010. Just outside The Quad is Burris Laboratory School. The K-12 school was established in 1929 as a part of Ball State Teachers College. Home games for Burris’ basketball and volleyball teams are currently played at Ball Gym. The facilities are still used for some Ball State physical education classes and

nearly 2,000 students. A year before its completion, a fire broke out during construction due to a gas line leakage, according to a 1966 Muncie Evening Press article. Despite this setback, construction on the hall continued to prepare it for opening. The 10-story building included housing for undergrad and graduate students, kitchenettes, lounges and laundry rooms on each floor, with an accompanying dining hall. Women’s and men’s halls and lounges were separate, as well as separate housing for graduate students when it opened. Eventually, the area surrounding the complex blossomed with the addition of the Johnson Complex and Carmichael Hall. In the decades that followed LaFollette’s opening, it stayed open and housed thousands of students, but eventually aged as central air became more standard and other dorms on campus received renovations. Instead of renovating the 50-year-old building, the university decided to start over completely with new residence halls.

In the dorm’s 50 years of being open, many Ball State alumni have memories living there, being with friends, or the dining services of the building. Becky Nickoli lived in Woody Hall in the LaFollette Complex in 1966. Because the rest of the building was still being finished at that time, only Woody and Shales floors were open in LaFollette that year. Even though they opened the floors

to students, Becky remembers seeing the finishing touches being made during move-in.

“There were people actively working and still things along the hallway, like doorknobs and showerheads and shower curtains in the bathrooms,” Becky said.

For a couple of days, she had a hole in the wall where a phone would eventually be placed to go back and forth between her room and the one next to her.

“If the people in the next room were still up, but you wanted to go to bed, the light from their room would shine right into your room,” she explained. “You had to, like, stuff a towel or something in the hole to keep the noise and the lights out.”

While the student living spaces were quickly completed soon after move-in, the rest of the building, including dining and lounges, would not be finished. The only dining option for Becky was at Noyer Complex, across campus. It wasn’t until homecoming weekend when she was able to see the hall fully finished and ready for guests.

While her family was visiting in the newly completed lounge, the repercussions of the complex being under construction became clear to her and her family.

“I remember that my dad saw a mouse run across the floor in the lounge,” she recalled. “It was just kind of funny. He’s like, ‘What did I just see?’”

After her first year in the complex, Becky was assigned to the dorm again the next year. During this time, she was able to utilize the amenities that weren’t open the year prior, such as the dining services in the building. During LaFollette’s years, not only did Becky herself live there, but her son and grandson

Ball Gymnasium Oct. 28 and Burris Laboratory School students participating in gym class Jan. 24 1981. Kadin Bright, Ball Bearings Photo; Ball State University Digital Media Repository, Photo Provided; Ava Bower, Ball Bearings Photo Illustration

were able to experience the complex as well.

In 2017, demolition began on parts of the LaFollette complex, which would continue until the last pieces were razed in 2022. This decision was made as part of a plan that included the new residence halls, North West and Beyerl residence halls, and North Dining. North West was built to replace Carmichael Hall, and North Dining would become a replacement for LaFollette’s services.

Despite its destruction, the building is not completely gone. The LaFollette Brick Project was created to give former residents a piece of their history and raise money for the Thelma Miller Scholarship fund. It allowed people to buy a brick from the building for $75. Not only have some bricks found new homes, but limestone from the dorm was repurposed to create the pillars of its memorial.

Ball State continues to make changes to campus, reviving older spaces and creating new ones. Even with the addition of new buildings or renovations on older ones, the history of and experiences of students still remain. As the university works on The Village, current students will keep the memory of how the area looked during their time. The memories, photos and stories keep the older spaces of campus alive

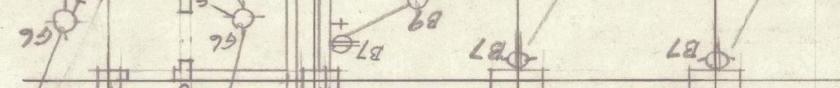

Kadin Bright, Ball Bearings

1899

Eastern Indiana Normal University builds administration building 1918

Ball Brothers donate Eastern Indiana Normal University land to the state, marking the beginning of Ball State

1925

Ball Gymnasium opened

1927

Lucina Hall is opened as a women’s dorm 1967

LaFollette Complex is built

1972

Lucina Hall turns into an office space

1990

Worthen Arena opens; Ball Gymnasium is used for Burris basketball and volleyball games

2017 Destruction of LaFollette Complex begins

Ava Bower, Ball Bearings Design Fall 2025 | Ball Bearings | 11

many forms of communication to garner universal understanding without words.

communication to garner universal understanding Preserving languages greatly benefits oral histories.

join the program in first grade, even if not enrolled during kindergarten. He explains that the program develops “sibling-like relationships and interpersonal relationships” that help the program feel like a family, since many students are in their specific cohort with their peers from kintergarden to fifth grade.

By Amira Alquraishy

seamlessly with Spanish as students switch between subjects, learning not just words, but the worlds they represent.

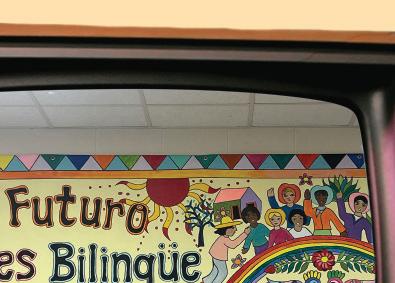

The school’s dual-language program integrates both Spanish and English instruction to strengthen bilingual learning and cultural understanding among students in Muncie.

The Indiana Department of Education has grown the Dual Language Immersion Pilot Program from four schools in 2014 to 42 schools in 2022. West View Elementary is the only participating program in the Muncie Community School District.

Throughout time, civilization’s preservation of language can be described as an evolutionary journey. Various creative techniques, like art and music, allow for

A large contribution to language preservation is teaching various languages to the next generation. West View Elementary School’s Dual Language Program is actively encouraging Spanish-speaking in Muncie by sustaining linguistic diversity and cultural empathy as a product of its success.

in a 50/50 or 80/20 model, to achieve

Dual-language programs immerse students into learning two languages, commonly in a 50/50 or 80/20 model, to achieve bilingualism, biliteracy, academic excellence and sociocultural competence, according to the Center for Applied Linguistics.

West View is now in its ninth year of the program. Initially, the initiative started with kindergarteners on an 80/20 model, in which kids were only using the spanish language 20 percent of the time they were in the class. As the program grew, they expanded into a 50/50 model, where students kindergarten through fifth grade learn in each language 50 percent of the time.

West View principal Eric Ambler notes that it is not uncommon for new students to

“The empathy that those kids show each other… I think it’s magnified by being in that setting,” Eric said.

Students can continue their learning at Northside Middle School, with the first cohort from the Dual Language Program now entering eighth grade at the school.

In the classroom, Kira Zick teaches Spanish all day through subjects like third and fourth-grade math, Spanish

third and fourth-grade math, Spanish and Spanish language arts. The third graders switch from English learning in the morning to learning Spanish-related subjects with Kira in the afternoon.

One of Kira’s teaching methods includes using music to immerse the students. By picking out key vocabulary and learning about the artist, students learn different dialects.

“It’s impactful to witness the growth throughout the semester,” Kira said. “... Learning another language, it seems like it opens up so many doors.”

Over time, students become more

comfortable speaking Spanish confidently and even spontaneously. With Kira finding fulfillment in exposing students to different cultures and the benefits of learning other languages, she sees firsthand the positive outcomes in how students interact with

“I think it’s really neat that they are

“I think it’s really neat that they are exposed to other cultures [and] people that aren’t like them. They’re excited to learn about places all around the world,” she said.

Eric describes the program as one that “preserves and honors cultural and linguistic heritage, fostering a diverse and inclusive school culture.” He explained that the dual-language initiative serves both native Spanish speakers and English learners, and that “significant language acquisition” has been observed among all students.

program’s growth impacting both native

Eric and his staff have witnessed the program’s growth impacting both native Spanish and English speakers. The program’s success has led to community recognition and a growing waitlist at West View Elementary.

As West View Elementary and Northside Middle School look ahead to expand their Dual Language programs, teachers and administrators continue to see the impact beyond the classroom. Each new cohort of students help construct a bridge between English and Spanish that grows within the Muncie community. each other.

Educational Studies students working in Northside Middle School, February 20. Samantha Blankenship, Ball State University, Photo Provided

Educational Studies students working in Northside Middle School, February 20 . Samantha Blankenship, Ball State PhotoUniversity, Provided

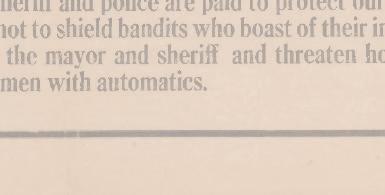

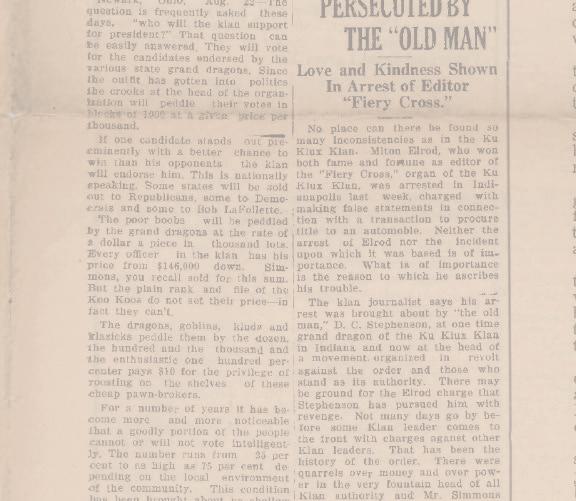

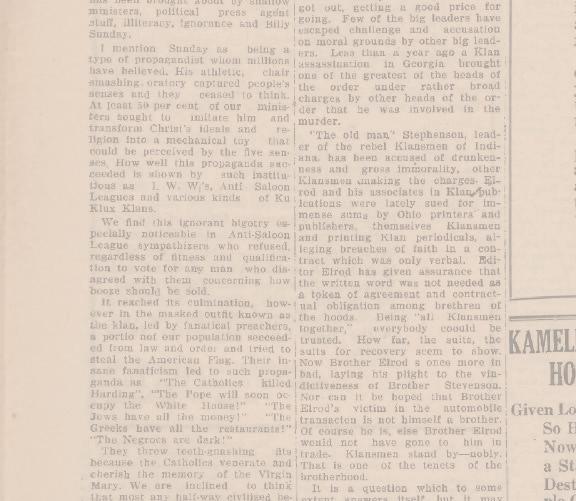

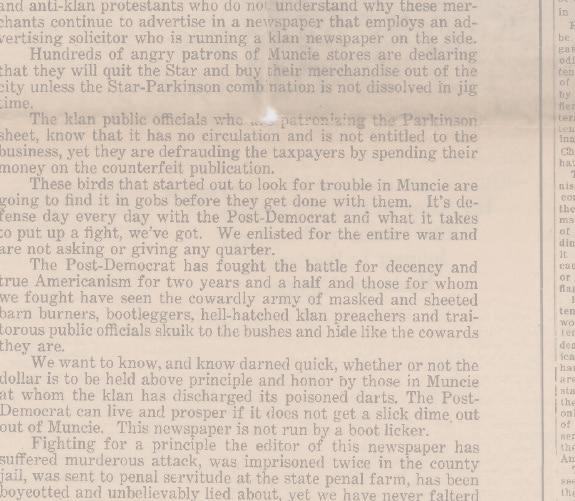

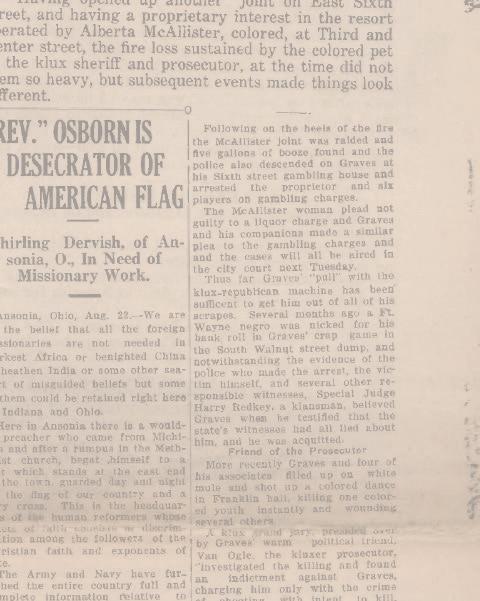

The evolution of digital media has cast a shadow over print media.

Martin Smith-Rodden waits while on assignment in Balad Iraq in 2004, while he was a sta photographer at The Virginian-Pilot. Hastings McIver, USN, Photo Provided

By Seyla

Ray

During an Aug. 2012 daily editor’s meeting at The Virginian-Pilot, Daily Sections Photo Editor Martin Smith-Rodden presents the options for photos for the next day’s newspaper and online content. Hyunsoo

Leo Kim, The Virginian-Pilot, Photo Provided

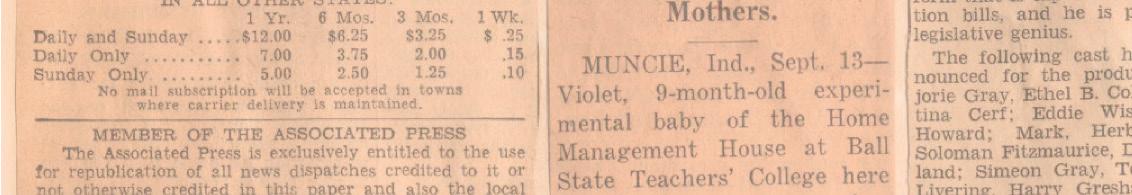

In 2025, different kinds of media are fast-paced and easily accessible to the masses. Between TV broadcasts, news websites and social media, information travels faster now than ever before.

However, it wasn’t always that way.

According to a 2018 Pew Research Center article, print media dominated the news world up until the 21st century. Stories travelled by word of mouth or by ink, and although printing newspapers was slower than word of mouth, the information was preserved by doing so.

From the invention of movable clay type printing in China in 1041 to the invention of the World Wide Web in 1991, media and modes of communication have changed drastically throughout human history.

This time period has been coined as “The Digital Revolution,” and followed the shift from print news to digital news as a primary form of communication.

There are people who think we should have never gone online and miss the days of print so much. I understand that, but you can’t look back; you need to move forward.”

- Keith Roydson, Former Star Press journalist

I think people always kind of have the assumption that digital will last longer, and that is actually not true. The web and born digital media are a lot more ephemeral than we realize.”

-

Lindsey Vesperry, Digital and physical records archivist in the Bracken Library Archives and Special Collections department

Since the 1990s Digital Revolution, not many people still read physical newspapers or magazines. U.S. newspaper circulation reached its lowest level of production since 1940 in 2018, continuing to decrease steadily through 2022, according to Pew Research Center.

Print media is still relevant, though it now serves a different purpose, acting as an archive of information.

Dr. Martin Smith-Rodden, an associate teaching professor in the School of Journalism and Strategic Communication at Ball State University, has worked in the field of media since 1980. He has worked in many different locations throughout his career, including 29 years at The VirginianPilot newspaper.

“Being a business and being a bureaucracy, those two silos did not talk to each other very well,” he said. “They were almost in competition, which sometimes happens, and that was an area of dysfunction that was sustained for several years.”

Martin worked at The Pilot until 2015 as a photographer, including the last decade there as a photo editor. Martin explained that those last 10 years were also the time when the organization was moving from a “traditional print newspaper paradigm to a digital-first paradigm.”

Martin said the organization was geared predominantly toward online news, stating that they put out the physical newspaper “almost as an afterthought.”

The switch from print media to digital was very gradual, he recounted. There was no big “lightbulb moment” when he realized that times were changing, but he did notice the differences.

Martin noted that he was open to the evolving modes of media, while some others around him weren’t quite as keen.

“I’ve never been someone to be hung up on change, but there’s a lot to like about print, with the elements and opportunities for design and presentation,” Martin said. “It is natural for humans to be nostalgic for the technology and workflows that they learned during their formative years.”

The switch from print media to digital caused strong feelings across the media landscape, but evidently, not all were negative.

“When these changes happen, it tends not to be instantaneous. It might feel instantaneous when we look back on it, and we give it really cute names like ‘The Digital Revolution,’” Martin said.

Martin stated that his organization “certainly talked about the pace of change.”

He added that within an organization, those sorts of changes spark lots of internal conversations, both formal and informal.

Other issues came with a switching paradigm, as well. Martin explained that his particular news organization had two different subdivisions, one exclusively concentrated on the print product and the other exclusively concentrated on the online product.

Keith Roysdon, a journalist of almost 50 years, published his first article as a high school student in 1977 and began work for the Muncie Star Press fresh out of high school. He then later went on to work for the Knoxville Sentinel newspaper. Keith said that throughout his time working in media, the transition from print journalism to online publishing was “probably the biggest change in any of our lifetimes” when it came to modes of communication.

Even though Keith’s beginnings were founded in print, he prefers the practicality of digital publishing.

“There are people who think we should have never gone online and miss the days of print so much. I understand that, but you can’t look back; you need to move forward,” Keith said. “You need to give people what they want, and there has never been a greater demand for news and information than there is now.”

As both Martin and Keith said, print media isn’t necessarily used in day-to-day life anymore, now finding its place and purpose in history.

Lindsey Vesperry, digital and physical records archivist in the Bracken Library Archives and Special Collections department, said digital pieces aren’t always easy to recover.

Keith

Keith Roysdon (right) reporting at a job fair in 2010.

Keith Roysdon, Photo Provided

“I think people always kind of have the assumption that digital will last longer, and that is actually not true,” Lindsey said. “The web and born-digital media are a lot more ephemeral than we realize.”

On paper, as explained by Lindsey, it may seem like, since the internet is so all-encompassing, it would be easy to find just about anything. However, finding the content isn’t the issue.

“We could, for example, get a donation from someone who might have made a Microsoft Word document in the 1980s,” she said. “There might be a chance we can’t even open that document anymore because new versions of Microsoft Word can’t recognize it.”

Lindsey said media that is only published online with no physical content is harder to archive. Print media offers a unique preservability that something intangible does not. She added that preservation has become more difficult as manuscripts are made with less care, as technological developments like the printing press increased production rates.

pages had to be done by hand, by scribes.

Lindsey explained that the mold was broken with the Industrial Revolution and the creation of paper. Paper was a lot cheaper than the materials previously used, but the automation of paper creation also helped. This was not without drawbacks, though.

“The automation made things that were not really meant to last,” said Lindsey. “With newspapers, you read it for a day and you toss it out.”

As explained by Lindsey, the short lifespan of newspapers is very characteristic of an ever-changing world, as there are always new stories to be told. There is charm to creating a newspaper in a rush, and it’s something adored by many journalists.

the end of the day. He also added that a side effect of the changed times is that deadlines are earlier now than they were “back then” because papers are printed further away.

There are pros and cons to printed media and digital media alike, and as times evolve, a common concern is that print news will cease to exist entirely. However, Lindsey said, humans are more adaptable than we’re credited for.

Lindsey explained that news, just like everything else, evolves with the times, and she is optimistic for the future.

Keith explained that he understands the appeal of a newsroom rush. He recounted a pre-digital age plane crash in Muncie, and used his experience of covering that event as an example for a news race.

She explained that up until the industrial era, literacy rates were very low. People who could read were the clergy or aristocracy, so books at the time were also very expensive. The work was considered difficult, as all the

“We had to get there fast. But we also had to be fast in doing a couple of quick interviews,” he said. “At the time, we had to get on the phone back to somebody in the newsroom, and they would start adding to the story.”

Keith explained that this process was necessary in order to get an article done by

“I understand cutting print news, practically speaking. I think it might be a bit harder [in a sense of archiving],” said Lindsey. “But I will say I have a lot of faith in how students and young people can evolve to understand the new concepts around them.”

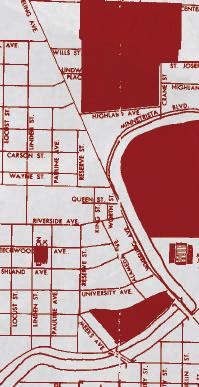

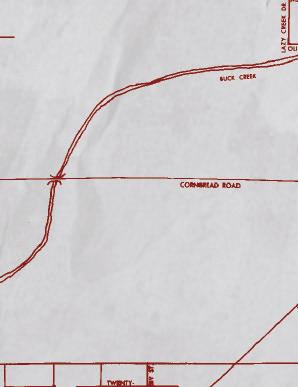

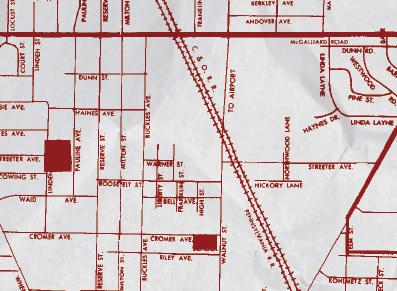

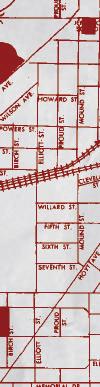

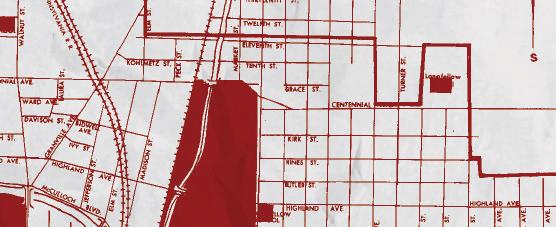

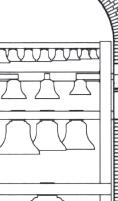

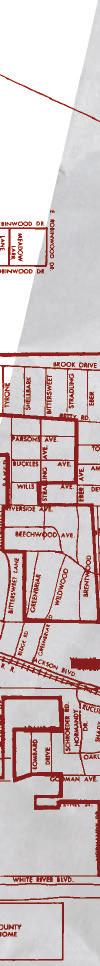

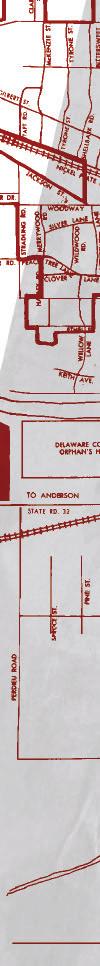

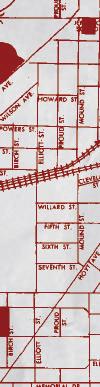

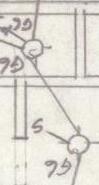

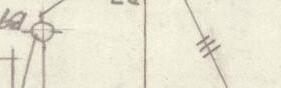

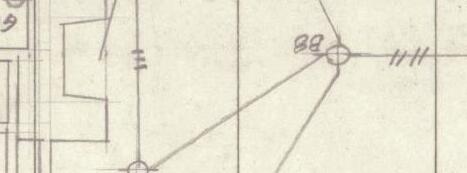

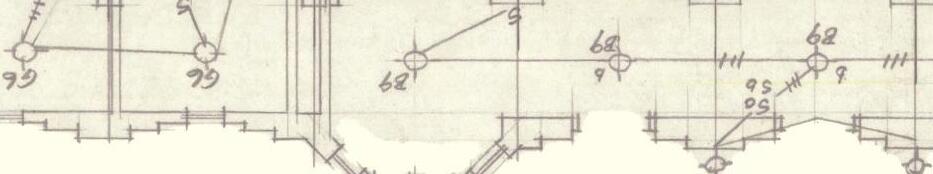

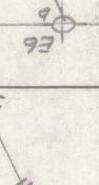

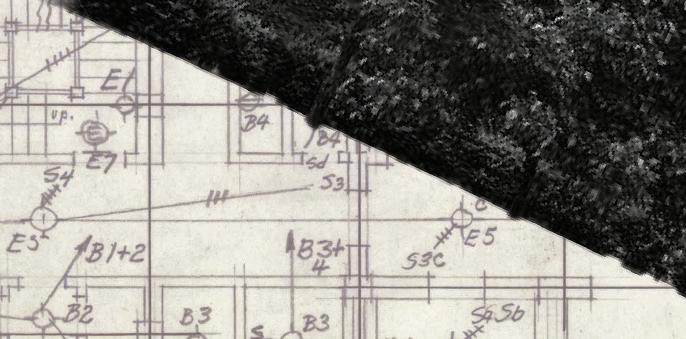

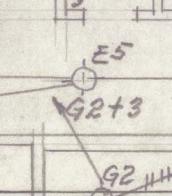

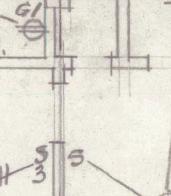

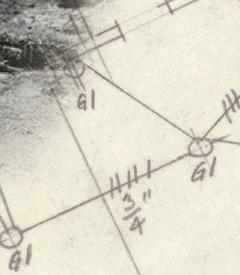

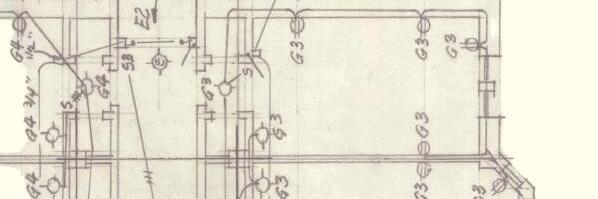

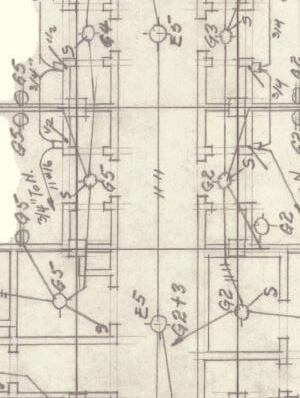

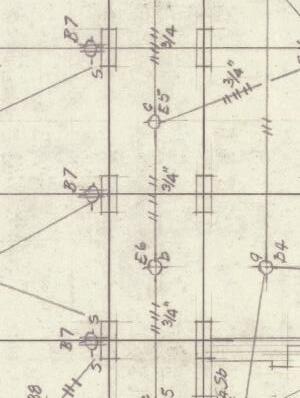

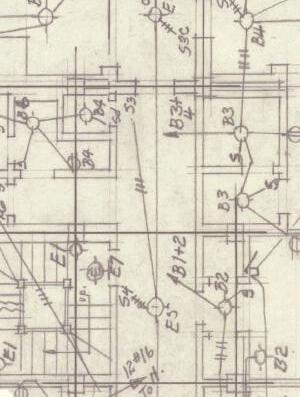

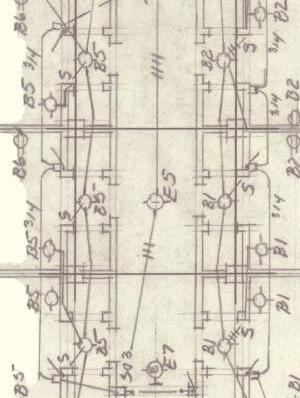

Looking at campus maps can give us a deeper appreciation for Ball State’s history.

By Brenden Rowan

When Chris Flook attended Ball State University in the early 2000s, he wasn’t able to see the bell tower out his classroom window, attend a performance at Sursa Hall or walk through the Foundational Science building.

“[Campus] was ugly,” he said. “It [had] a utilitarian, mid-20th-century kind of look for everything.”

Chris, who’s now a senior lecturer in the Department of Media on campus, has witnessed campus flourish. He enjoys sitting in his office, looking out his window at the beautiful view in front of him.

Ball State has evolved considerably since the university opened in 1918. Each time a major moment of evolution occurred, whether it be the removal or addition of a structure, a cartographer was tasked with capturing that moment on a map.

At the turn of the century in around 1900, Chris said there was a movement called “City Beautiful,” as towns hoped to revitalize their communities in response to the Second Industrial Revolution. During this, factories were dumping polluted waste into the rivers, streets were filled with trash and the air was filled with smog.

There’s always been an effort to make the natural space good.”

- Chris Flook, Local historian and senior lecturer of media in the department of media

When Ball State’s campus was built, they wanted to create a space for students to congregate, so they designed the campus Quad.

“There’s always been an effort to make the natural space good,” Chris said.

Comparing what he sees now to when he was a student at Ball State, Chris said that there are more hubs on campus for students to “just exist.” When he was a student, all they had was the library.

For over 20 years, Melissa Gentry has been the supervisor of the Paul W. Stout map collection in Bracken Library.

She said that maps are more than just for navigation; they are an “archive of the world.’ Not only do we see changes in the physical world

around us, but also how political climates and society have changed through time.

In 1976, the collection started with 8,000 maps, but now holds over 140,000. The collection grew in part because of a federal depository, meaning any map made by the government was automatically entered into the collection. Paul Stout, the originator of the collection, attended summer workshops at the Library of Congress, where he would trade maps for the collection.

Maps can be used for much more than navigation. We can use them as resources in our history or as visual aids in presentations. Melissa said that maps are also great for visual learners when it comes to research.

“You can write a paper that’s thousands of words, but you can have that same topic represented on a map,” Melissa said.

The Paul W. Stout map collection has the entire set of Muncie’s maps and Melissa said it is interesting to see its changes over time.

One example she pointed out was in Muncie’s early history. There were “horserelated buildings” such as barns, stables and liveries. Years later, those buildings went away as the bicycle became popular. Now they are replaced by gas stations.

When discussing the evolution of Ball State’s map, Melissa said some may believe that the campus started from the Quad and moved north, but it actually evolved nonlinearly, partially due to former university president John Emens.

During his time in the role, the Teachers College, Hargreeves Music building, Arts and Communications building, and LaFollette Hall were built. This left a large empty field between the Teachers College and LaFollette Hall that would later be filled in by other campus buildings, like Bracken Library in 1972.

Dean of the Estopinal College of Architecture and Planning David Ferguson has worked at Ball State for over 35 years and is trained as a landscape architect, an alum of the Ball State College of Architecture and Planning (CAP) program.

David said before the 1980s, campus was planned “haphazardly” until landscape architecture became intentional. It wasn’t until the 1990s that we began seeing pathways that are curvilinear lines.

“Most of the impact on our footprint has been generated by landscape architecture and master planning firms,” David said.

We as human beings have an intuitive sense for spaces that have energy to them.”

- David Ferguson, Dean of the estopinal college of architecture and planning

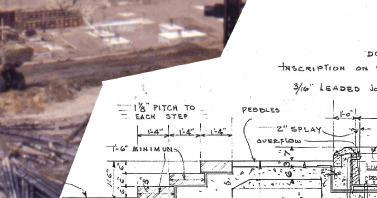

One of the first gathering places on campus came with the addition of the Frog Baby Fountain in 1993. Eric Ernsperger, a Ball State CAP alum, opened a design firm in Indianapolis whose team has designed many features on campus, such as the Schafer Bell Tower and the Frog Baby Fountain.

“We as human beings have an intuitive sense for spaces that have energy to them,” David said. “We can tell when there’s a good design in front of us.”

David said campus is not the same place as it was when he was in undergrad. When he attended Ball State, the CAP program was in what was then called the Quonset huts,

former army barracks turned into classrooms. After the original CAP building was built in 1972, the College of Business then took over the Quonset huts until the Whitinger Business Building was erected in 1979.

For some time, David said, he felt that the east side of McKinley would never be developed. At the time, that area was a path now referred to as “The Cow Path.” It wasn’t until 1984 that all of that changed, when Robert Bell was built and the University Green became an official quad. In 1988, Ball Communications and the Letterman building, were built, starting the central cluster of the current campus.

Currently, Ball State is moving into The Village, starting with a new performing arts center. This will serve as a catalyst to start The Village Revitalization Project.

Chris hopes to see a stronger connection with The Village in the coming years. He said that ideally, a grocery store or a movie theater would be added so students could live on campus without the need for a car.

As campus continues to grow, we will continue to see additions to its map. As we look towards the future, we can ensure that it will be captured in history.

By Tatum Harris, Trinity Rea

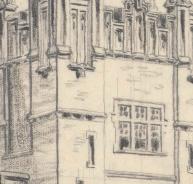

In the lobby of Elliott Hall, illuminated by a dim overhead lamp, sits a lone portrait of Frank E. Ball. Crimson walls surround the painting, glowing under the room’s ornate white molding. The lobby’s original 1940s furniture sits in near-perfect condition.

Everything remains exactly as it was, except for the students.

Around Ball State’s campus, the stories about Elliott Hall never seem to fade. Students trade whispers of ghosts, echoing traditions and long-told rumors.

But behind the lore lies a different story, one rooted not in hauntings but in history and community. Elliott Hall was something simpler, a cornerstone of campus life, built to house generations of Cardinals with roots that trace back to when Ball State was still defining its identity.

Frank Elliott Ball Hall, later shortened to Elliott Hall, opened in 1938 as a men’s dormitory on campus. The hall was named after Frank E. Ball, the assistant treasurer of the Ball Brothers Company, after his unexpected death in 1936. Frank was the son of Frank C. Ball, the company’s president.

Frank Sr. and the rest of the Ball family funded Elliott Hall’s construction as a memorial. Built in a Tudor-Gothic style, the hall was inspired by the design of Frank Jr.’s former college dorm at Princeton University.

While Elliott opened as an all-male dorm, its use would shift over time. During World War II, Elliott housed female students and nursing trainees as school enrollment dropped overall, reflecting the United States’ entrance into World War II. Upon the war’s ending, Elliott reverted to an all-male dorm, but post-war enrollment growth placed the university in a housing crisis.

In 1947, a decade after the halls’ opening, Elliott Annex, a wood-frame barracks-style housing unit, was built behind the hall, holding about 64 total students. The annex

primarily served veterans during the GIBill boom, but was torn down in 1960 once larger dorms were built. Apart from the annex, Elliott Hall has seen no large-scale expansions. The hall has also avoided any major renovations, preserving the exterior and interior woodwork.

After a brief closure around the early 70s, Elliott Hall reopened as a coed residence for seniors, with men and women on alternating floors. This was Ball State’s first coed dorm. The hall remained coed throughout the rest of its time in operation, housing approximately 120 students when at maximum capacity.

Elliott Dining, an all-you-can-eat buffet dining facility, existed in the basement of the hall. During a time when resident halls had designated dining halls, Elliott Dining was catered specifically to the small group of residents.

The dining space would eventually move into the Eliott Wagner building, located behind the residence hall. The facility has since been repurposed as the

university’s Office of Risk Management.

In the late 1980s, Ball State’s Indiana Academy for Science, Mathematics, and Humanities moved into the basement of Elliott Hall. This resulted in a repurposing of the space for office use.

Through the COVID-19 pandemic, Elliott housed quarantined students. However, upon the opening of North Hall, now named Beyerl Hall, in 2020, Elliott was no longer needed as on-campus housing.

Marissa Thompson thought someone had put a castle on campus when she first saw Elliott Hall during her sophomore year at Ball State. Though she’d never heard of the building tucked away by Beneficence, she was thrilled to be offered a resident assistant (RA) position in the hall.

Marissa quickly found her place on campus after moving into Elliott. She described the hall’s culture and environment as “eccentric,” drawing in all kinds of students with various backgrounds and interests.

From aspiring art students to former service

If you get an opportunity to go to and see Elliott, take it, because [in] Elliott, it’s like walking into a time capsule.”

- Marissa Thompson, Former Elliott Hall resident

members, the students who came into Elliott Hall made for an eclectic group. This was one of Marissa’s favorite parts of her job as an RA.

“It’s like Elliott just transported you somewhere completely different than anything that you had ever seen before,” Marissa said.

Marissa worked as the female RA on the third floor at Elliott Hall for three years. With a limited number of students at Elliott, each floor required only one RA.

She still remembers her unique introduction to the male RA on the floor below her, Kyle Thompson.

Marissa said, “It was kind of funny, because he opened up his door with the director there, and he was just in his underwear. That was it.”

Kyle, a student-athlete studying business at Ball State, quickly became one of Marissa’s best friends while they worked together at Elliott. And eventually, after the two had graduated, that friendship turned into something more.

Marissa and Kyle have now been happily married for 15 years and have three children together.

“We absolutely loved Elliott. It made Ball State for us,” Marissa said.

For their 15th wedding anniversary, Marissa and Kyle returned to Elliott, where they found scrapbooks on the fourth floor containing photos from their RA days.

“It was definitely a walk down memory lane,” Marissa said. “... If you get an opportunity to go to and see Elliott, take it, because [in] Elliott, it’s like walking into a time capsule.”

For those who lived there, Elliott Hall was never just a building. It was where friendships formed over card games, traditions brought floors together and people met to build lives together.

Former resident Jaimee Barr graduated from Ball State in 2017 and lived in Elliott during her last year of school. She remembers the dorm as a hub where everyone supported one another.

The ceiling inside Elliott Hall’s main lobby, Sept. 12. Olivia McSpadden, Ball Bearings

Community (LLC) was located within Elliott. As Academic Peer Mentor for the LLC, Jaimee ran programs designed to connect transfer students to the wider campus.

At Ball State, LLCs place students amongst others in the same field of interest and provide them access to LLC-exclusive experiences like peer mentoring, resource rooms, makerspaces and other majorspecific experiences.

She said Elliott felt like home, recalling everyday comforts and rituals that provided her with a “different residential experience.” These small moments, Jaimee said, were central to the hall’s identity and longstanding traditions.

floor haunted house that charged admission for charity.

“Elliott was really big on Halloween,” Marissa said. “…We carry [the tradition] on with our kids now — we decorate our whole front yard. Halloween is huge for us as a family; it really connected my husband and I because we had a lot of fun memories [in Elliott].”

The Hall became a hub for tradition as students grilled on the hall’s back patio, perched on its ledges and shared stories that blurred the lines between myth and memory. Staff, students and administration agree that Elliott Hall now stands as a memento of the early times at the university.

As of now, nothing is slated to change with the historic building.

“There are no current plans for Elliott Hall beyond housing the administrative offices of the Indiana Academy,” said Vice President of Student Affairs, Ro-Anne Royer Engle.

I spent a lot of time in my room by myself with the door closed during my first three years on campus, but the culture in Elliott encouraged me to spend more time in common areas of the building.”

- Jaimee Barr, Former Elliott Hall resident

“It was the best residential community I ever had the privilege of living in,” Jaimee said. “There was always something going on in the first-floor lobby or the second-floor study lounge, or even outside when the weather was warm.”

Jaimee said Elliott’s small size helped people form close bonds. During her time at the hall, the Transfer Living-Learning

“I spent a lot of time in my room by myself with the door closed during my first three years on campus, but the culture in Elliott encouraged me to spend more time in common areas of the building,” Jaimee said.

Events like homecoming and volleyball tournaments brought the students living in Elliott Hall together. Traditions such as putting togeher the annual haunted house on the fourth floor of Elliott bonded the students who lived there together.

Halloween brought forth Elliott’s most signature tradition: an elaborate fourth-

Today, Elliott sits silent. Rsooms still have their bay windows, and the fourth-floor library still holds its books. Although the dorm no longer houses students, resides in the memories of those who called it home and in the stories Cardinals continue to tell.

“Ball State has a lot of history that I hope all the students get to experience,” Marissa said. “It’s not just these modern, beautiful buildings. I hope they can appreciate those old stories and those old memories.”

The next time you take a stroll through Ball State’s campus, don’t forget to explore beyond The Quad. Just past Beneficence stands the formidable Elliott Hall, an embodiment of Ball State’s long and luminous legacy.

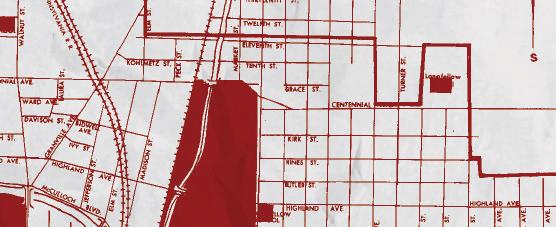

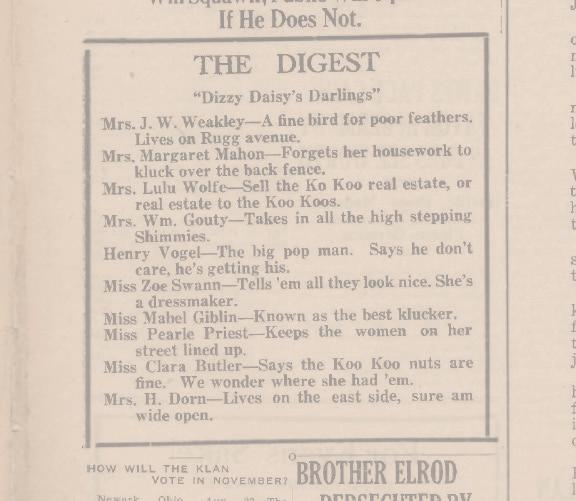

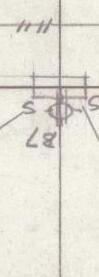

From gas boom mansions to a highway’s intrusion, one neighborhood’s 140-year story reaches a turning point with planned roundabouts.

By Andrew Berger

Editors note: The Indiana Department of Transportation was contacted for this story, but did not respond to a request for comment.

In the fall, when burning leaves scent the air along East Washington Street, it’s easy to imagine Emily Kimbrough as a girl, watching gas lamps flicker to life from the porch of her Victorian home.

The author, born in Muncie in 1899, would grow up to write about her childhood in what locals called the “East End.” Today, the historic district that bears her name stands at a crossroads, caught between preserving architectural legacy and accommodating modern traffic demands.

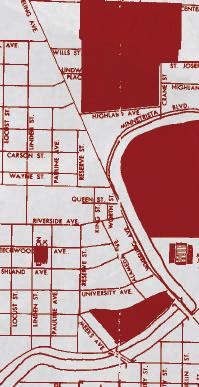

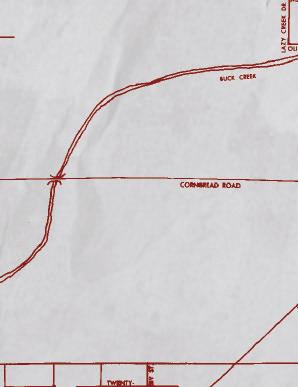

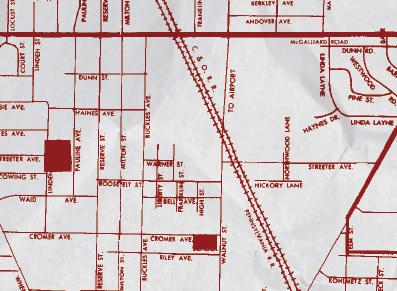

The Indiana Department of Transportation (INDOT), along with the City of Muncie, plan to install four roundabouts along State Road 32 (SR 32), cutting through the heart of the Emily Kimbrough Historic District. The proposal has placed the neighborhood on Indiana Landmarks’ 2025 endangered list and revived long-standing tensions about a state highway that residents say should never have been routed through their community.

Roundabouts only facilitate greater automobile and truck traffic; it does not make it more pedestrian-friendly.”

-

Mark Dollase, Preservation specialist for Indiana Landmarks’ central regional o ce

The Emily Kimbrough Historic District owes its existence to an accident of geology. When drillers struck natural gas in Delaware County in 1886, Muncie transformed almost overnight from a modest agricultural center into an industrial powerhouse.

Those who profited from the gas boom built mansions in the “East End,” the preferred address of Muncie’s social elite. The architectural ambition of these industrialists still defines the neighborhood today.

When the neighborhood was designated as a local historic district in 1976, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, residents chose to honor Emily Kimbrough’s connection to the area.

Kimbrough eventually left Muncie, leaving her house on East Washington Street. The house was then converted into the Emily Kimbrough Historic Museum, honoring her legacy and the neighborhood’s rich turn-ofthe-century history.

In 1958, SR 32 was routed through the neighborhood along Main and Jackson streets, converting what had been two-way streets into paired one-way highways.

According to INDOT, the stated goal was to expedite traffic flow through the city.

J.P. Hall, an associate professor of historic preservation at Ball State University and a member of the Indiana Main Street Council, sees this decision as a critical inflection point.

“For decades, the neighborhood lived with the consequences, increased traffic speeds, pedestrian safety concerns and the general sense that a highway rather than a street ran through their community,” J.P said.

In recent decades, renewed interest in historic architecture has brought new energy to the Emily Kimbrough District. This has resulted in groups like The East Central Neighborhood Association, which works to improve the area through maintaining traffic islands, organizing a community garden, coordinating neighborhood-wide alley cleanups and more.

Tom Collins, an associate professor of architecture at Ball State, is a resident of the historic neighborhood and a past president of the East Central Neighborhood Association board. Tom explained that over the years, residents and city officials

recognized that traffic on SR 32 posed ongoing safety concerns.

To address this, the state completed a ‘road diet’ along SR 32 in 2024, a project designed to make the road safer by reducing lanes and adding pedestrian infrastructure. The reconfiguration reduced the two lanes of one-way traffic in each direction to a single lane per direction, added bike lanes separated by buffers, and improved handicapaccessible ramps at intersections.

“The traffic does move slower,” Tom said. “You do not see people driving down SR 32 going 60 miles an hour anymore, which they used to.”

of highway, the stretch of SR 32 running through Muncie from the bypass to Yorktown, to municipal control. INDOT also provided funding to support long-term maintenance and improvements.

This included projects such as the road diet; however, embedded in this road relinquishment agreement was something the neighborhood did not know about: four roundabouts. The roundabouts would be situated in the heart of the Emily Kimbrough Historic District, along Main and Jackson streets where they intersect with Madison and Hackley.

A lot of the discussions happened long before anybody in the neighborhood ever knew about it.”

- Tom Collins, Associate professor of architecture at Ball State

For the first time in decades, the neighborhood appeared to be gaining ground in managing the traffic that had divided it.

The road diet project resulted from a deal between the city and INDOT in 2023. A levee wall protecting the city from flooding, located near an INDOT bridge where SR 32 crosses the White River, was not in compliance with federal flood protection standards.

Rather than undertake the repairs themselves, INDOT offered an alternative: they would give the city the road. The agreement transferred roughly six miles

Tom eventually discovered the deal. INDOT and the city had locked in the roundabouts before any federal historic preservation review began – a sequence that Tom argues violates the core principle of Section 106, the review process designed to prevent exactly this kind of situation. Section 106 is a federal process mandated by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. J.P. explained that it emerged as a response to decades of federal highway and urban renewal projects that demolished and divided city neighborhoods without community input. J.P. said that by the 1960s, public frustration with these destructive practices reached a breaking point.

“People were finally fed up and said, ‘This is enough,’” J.P. said.

According to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Section 106 requires federal agencies to identify historic properties, assess the effects of their projects on those properties and work with stakeholders to mitigate the impact. However, the review does not mandate a specific outcome.

“What it does do is slow a project down and afford stakeholders an opportunity to voice their opinions,” J.P. said. “That, in many cases, can change a project.”

Mark Dollase, the preservation specialist for Indiana Landmarks’ central regional office, emphasized the State Historic Preservation Office’s (SHPO) role in this process. If consulting parties can demonstrate sufficient concern, the SHPO may refuse to sign off on the project agreement. Mark said that this can create leverage for communities. Yet in practice, the process can feel like a formality when things appear predetermined, as they do in Muncie.

According to INDOT material, the roundabouts are needed to address safety concerns. In the agency’s project documents, 157 accidents occurred at the four intersections between 2018 and 2020.

INDOT’s stated goal is to reduce overall crashes by at least 20 percent while maintaining stable traffic flow through 2047. At a May 2025 consulting party meeting, INDOT stated that the initial 2024 road diet did not accurately address these numbers.

But there is a critical issue: this data was collected before the 2024 road diet.

“So why did we do the road diet if it didn’t totally solve the problem?” Tom asked. “Did we know while we were doing the road diet that it actually wasn’t going to be 100 percent effective?”

During the consulting party meeting, INDOT officials acknowledged they are collecting new crash data but said only five months of post-diet data had been collected.

While INDOT and the City of Muncie believe that roundabouts are the best option to fix things, residents and outspoken voices, like Tom and J.P., argue otherwise.

“There’s a whole range of different things you could do,” Tom said, referencing raised

traffic tables, extended curb cuts, stop signs and speed bumps as options.

Mark also advocates for alternatives.

“Roundabouts only facilitate greater automobile and truck traffic; it does not make it more pedestrian-friendly,” Mark said.

Each year, Indiana Landmarks compiles a list of the state’s most endangered historic places. The designation is not a death knell, but a call to action. Properties usually stay on the list for two years as the organization works to find solutions.

Indiana Landmarks added the district to the list for two reasons; the first is disinvestment. Mark shared that two years ago, Landmarks staff walked the streets of the Emily Kimbrough District and said they saw both restored properties that had been maintained for decades and houses in distress.

“If we lose those properties, if they become vacant lots, they’re only going to diminish the overall character of the neighborhood that much more,” Mark said.

The second is the roundabout proposal.

“When any project affecting a historic area, in this case, a transportation project, has such a major effect on that area, Indiana Landmarks is going to step up and voice our concerns about what those changes look like,” Mark said.

Mark worries the roundabouts would discourage people from choosing to live in the district. He believes that walkable neighborhoods are what people want when investing in urban areas.

“Doing what is being proposed by the city of Muncie and INDOT is sort of counterintuitive to what people would want to live in this neighborhood,” said Mark.

The local historic district designation is also more than symbolic. It is the law.

“In order for my neighborhood to become a locally designated historic district, 50 percent or more of the residents had to vote in favor of making it a local district,” Tom said.

He explained that this law mandates that any change to anything ranging from the streetscape or the homes — all must go

through a federal review process.

Beyond the specific issue of roundabouts, residents and preservation professionals are frustrated by how the project unfolded.

I don’t think neighborhoods like solutions to be imposed on them without any discussion.”

- Tom Collins, Associate professor of architecture at Ball State

“A lot of the discussions happened long before anybody in the neighborhood ever knew about it,” Tom said. “I’m not even sure anybody would have ever mentioned it until we got to the point where they have to do these public meetings.”

Tom believes this matters as much as the project itself.

“I don’t think neighborhoods like solutions to be imposed on them without any discussion,” Tom said. “They don’t like to find out after the fact the city’s been planning something with the state for years, and they’ve never been told.”

Mark shares this concern.

“The people that are speaking out in Muncie are people who live there and have invested in this neighborhood for decades,”

Mark said. “The fact that they’re being steamrolled right now and not being listened to is certainly concerning to us.”

According to INDOT materials, a public hearing has been scheduled for late 2025, with environmental document approval and right-of-way acquisition planned for early 2026. The consulting party meeting summary indicates construction has been delayed until early 2028.

For now, the Emily Kimbrough Historic District waits. The street pattern established before cars existed still connects neighbors to downtown. The historic homes still stand.

What the neighborhood will not see, its residents hope, is a solution imported wholesale from state highway engineering standards — a solution designed for cars, not for people. Whether Section 106 can protect that neighborhood’s future, nearly 60 years after a state highway first divided it, remains to be seen.

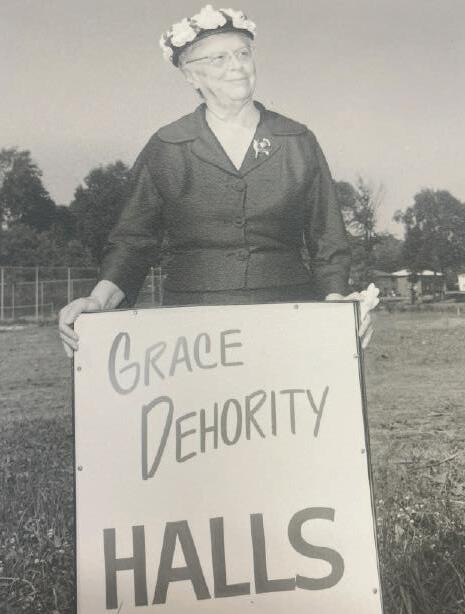

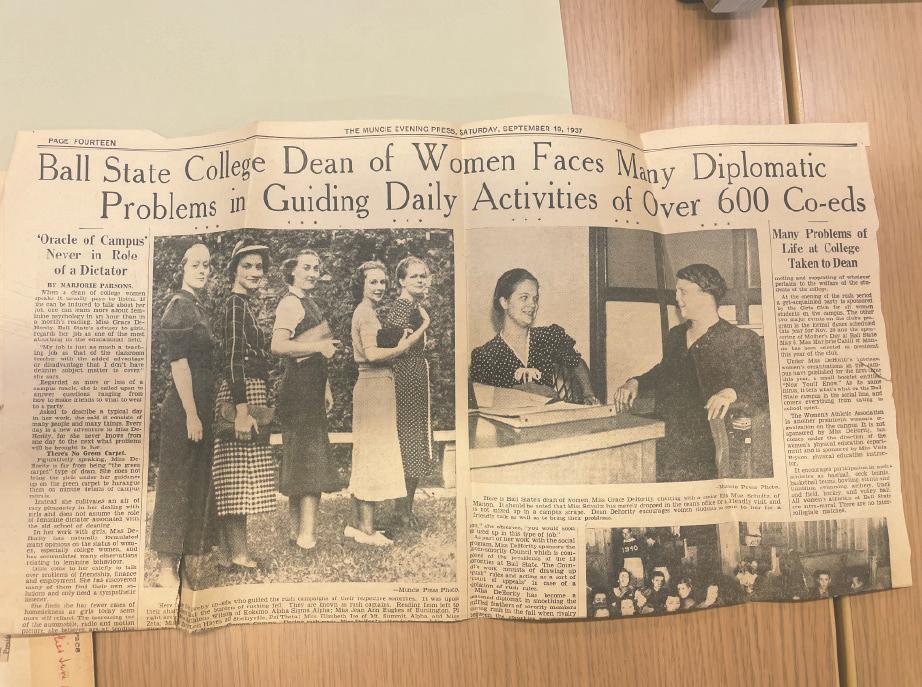

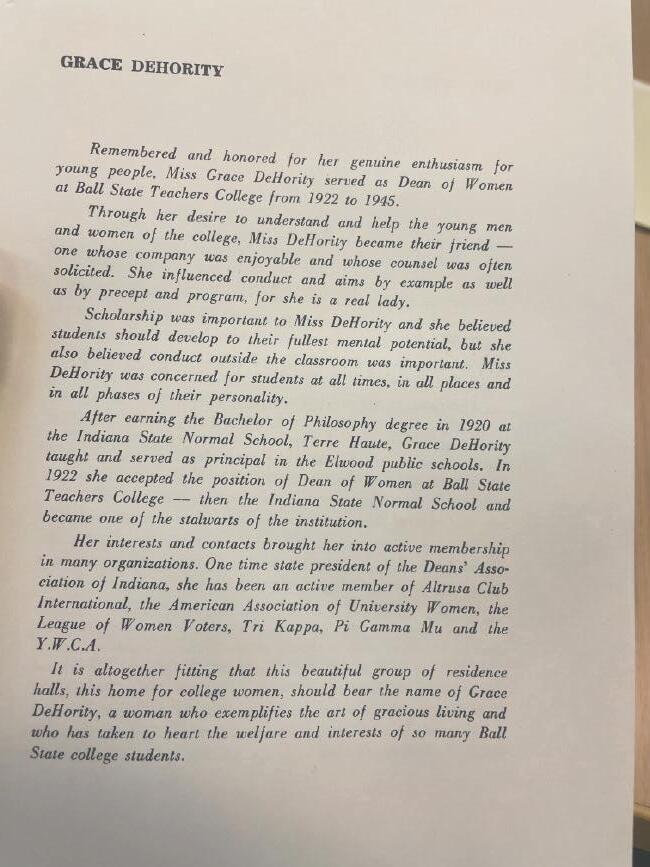

The namesake of DeHority Hall was more than just a faculty member.

By Radley Richman

Editor’s note: This article reflects on the life and influence of Grace DeHority based on archival information and the writer’s reflections. His views do not necessarily reflect those of Ball Bearings Magazine.

“Fill all blanks, please.”

Such was Grace DeHority’s “favorite saying,” according to the 1923 edition of the Ball State Orient, the official university yearbook, which is no longer in production. This line reads less as a pleasant instruction at an appointment you’d rather skip, but rather as a challenge raised to every student.

Grace was a testament to the fact that one’s legacy can never truly be measured by the power of their name alone.

An editorial published in the Muncie Evening Press after her death declared, “Here was a woman of staunch character, a living example of the ideals that were always her guiding stars, a good woman. She set a high standard for herself and continually urged others, particularly the women who came under her, to live full lives.”

Miss DeHority served graciously and with dignity and a deep appreciation of all with whom she came in contact. She leaves us a rich legacy for which we are all grateful.”

- John Emens, Ball State University president from 1945-1968

Grace’s legacy is more than just the dormitory complex where students occupied their freshman year; her legacy lies within the thousands of women who were under Grace’s tutelage during her 24 years as Dean of Women.

On Aug. 2, 1879, Grace DeHority became one of fewer than 800 in the quaint town of Elwood, Indiana. Born to James and Louisa DeHority, she lived in a house of eight. Grace was the eldest of her siblings. Throughout her early years, Grace matriculated through the Elwood public school system, graduating at age 19 in the summer of 1899.

Right after graduation, she began teaching at Elwood schools, earning a $360 annual salary to start. Grace taught at Elwood Elementary for ten years until 1910, when she moved to the junior high. It was here that she taught science and geography, improving her earnings to a $1,100 annual salary. However, in 1907, at the age of 28, Grace DeHority’s life as a teacher became far more complicated. Her father, a small grain and implement dealer, passed away just one year after her mother. This left her to raise her youngest sibling, twelve-year-old Anna, on her own.

Her sisters, Ethel and Alice, were married off, and her brothers Glen and Chester went off to find their own wives soon after.

It was only after Anna’s coming of age, six years following their father’s death, that Grace found the time to attend the Indiana State Normal School in Terre Haute, earning a bachelor’s degree in philosophy in 1920, at age 41.

After graduation, Grace found herself as the principal of her alma mater, the junior high school in Elwood. She only occupied this position for two years, as in 1922, she took the vacant position formerly filled by May Klipple: Dean of Women at Ball Teachers College. The position had only existed for four years, beginning in 1918, with Viletta Baker operating as the first Dean of Women until 1921, when May took over for a year.

Viletta and May, who went on to become professors of foreign languages and English, respectively, each had a hall named after them; these halls would complete what would become the Noyer Complex, a dormitory that still stands today.

In 1946, when Grace retired after 24 years at Ball Teachers College, the position retired with her. No longer would there be a Dean of

After World War II, when soldiers came back from war and resumed their education, students would be under one dean, regardless of gender. In the years following her retirement, the Ball Teachers College community made Grace’s name a hallowed one. Fourteen years after her retirement, in 1960, Grace’s work at the university was honored with a brand new dormitory in her name: the Grace DeHority Residence Hall.

In interviews published in the Muncie Evening Press, students spoke of the impact Grace had on their lives. A former student said of Grace,

Grace’s colleagues in the student personnel department at Ball Teachers College praised her dedication deeply, detailing in a statement in the Muncie Evening Press: “Through her desire to understand and help the young men and women of the college, Miss DeHority became their friend – one whose company was enjoyable and whose counsel was often solicited. She influenced conduct and aims by example as well as by precept and program.”

Between fulfilling her duties as dean, she found the time to earn her master’s degree at Columbia University, which she completed in 1928.

As Dean of Women, Grace held the advancement of women’s rights as top priority. In her time, Grace was one of the most active members of the local feminist community, supporting young women in embracing their independence and their power all throughout her time in Muncie.

Ball State is what it is today because of a loyal, hard-working and dedicated faculty who had faith in a young institution. Miss DeHority was one of the leading members of this rather small, but stellar group.”

- John Emens, Ball State University president from 19451968

“When I think of all I got from her in college, I don’t know how any woman could give so much. She expected good conduct and even insisted on it; yet, she was kind but firm when people did not live up to [her] high standards.”

At Ball State, she sponsored several sororities, while also taking on the Girls’ Club, founded by her predecessor, Viletta Baker. By her final year at Ball State in 1946, she had grown the Girls’ Club to be the largest organization on campus, with over 500 girls being members of the club.

In the spring of 1945, as most young men in the country were still overseas, there were only 550 students at Ball State. Nearly every single student at Ball State was female at the time, and nearly every single Ball State student belonged to Grace DeHority’s Girls’ Club.

The president of Ball State from 19451968, John Emens, once said, “Ball State is what it is today because of a loyal, hardworking and dedicated faculty who had faith in a young institution. Miss DeHority was one of the leading members of this rather small, but stellar group.”

Grace didn’t stop there; she also had a deep involvement with the Central Indiana chapter of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), heading a leadership committee of 18 girls, serving as president of the organization and later as the president of the board of directors. She was also the head sponsor of a Ball State chapter of the YWCA, heading a leadership committee of 18 girls, with a president, vice president, secretary, treasurer, and a cabinet consisting of 14 female students.

The Ball State YWCA would host a variety of events, including its Morning

The 1964. Repository,

Prayer with and its World Student Service Fund. What gained Grace the most notoriety within the Muncie community, however, was her involvement in the Altrusa Club. Now, Altrusa International of Muncie, Indiana, the Muncie division was founded on Oct. 17, 1923, with Grace present as a founding member.

From 1923 until she died in 1964, she was an extremely active member of the club, often using the home she shared with Ms. Barcus Tichenor, Ball State librarian from 1921 to 1945, as a home base for Altrusa Club meetings.

On the morning of June 19, 1964, Grace was seen picking flowers from her garden hours before that night’s annual meeting. That afternoon, she fell ill and was rushed to Ball Memorial Hospital, where she died shortly after. The Altrusa Club annual meeting on June 19 occurred without a single flower from the DeHority garden.

The people of Muncie refused to see another Altrusa Club meeting without the presence of Grace’s flowers. In 1965, her YWCA colleagues used funds raised from the YW Thrift Shop, which she had personally supervised, to build the Grace DeHority Memorial Garden, located on the east side of the Muncie YWCA.

“Miss DeHority served graciously and with dignity and a deep appreciation of all with whom she came in contact. She leaves us a rich legacy for which we are all grateful,” John said of Grace in a statement published after her death in the Muncie Evening Press.

In an article published in the Muncie Evening Press by Marjorie Parsons, she was described as a “campus oracle.”

In Grace’s eyes, when asked what she believed her job was, she believed it was

“just as much of a teacher of the classroom with the added advantage or disadvantage that I don’t have a definite subject to cover.”

For decades, Ball State women would come to Grace asking what dress to wear to a party and how to make friends.. Through it all, Grace DeHority was a teacher and she taught everything she knew to the women of Ball State University.

In an unaddressed letter signed by Grace, she stated her opinion on the characteristics of what makes a good teacher.

“A good teacher should have: Vigorous mind and body, much knowledge, great wisdom, tact,

sense of humor, pleasant voice, ability to get on with people, ability to inspire effort, ability to make people make themselves

A Mother Carey, as it were. Grace DeHority.”

Older forms of media have a long-lasting e ect on individuals.

By Linnea Sundquist

“You pick your album, you pull it out, you brush it off, put it on, drop the needle. I mean, there’s a whole process to it,” said owner and operator of the Record Parlor of Muncie, Derek McNelly.

Upon entering the Record Parlor of Muncie, customers see a variety of used vinyls, with a wide range of genres and artists. While the establishment does carry newer releases of music, the owner wanted to focus on used records. He said the promotion of newer artists’ music “kind of does its own thing” regarding mediums that can easily advertise their work, such as social media.

Listening to records has always been a passion for Derek. He recalled his father teaching him and his brother how to play pool after dinner most nights, while records played in the background. Derek explained how those albums he listened to were the first ones he became “connected with,” making him want to start his own collection.

Older forms of media have made a “comeback” over the past couple of years, with cassette tapes increasing in sales by 440 percent from 2015 to 2022, according to a 2023 PBS News broadcast, with mainstream artists such as Taylor Swift, Harry Styles and Billie Eilish “capitalizing on the fad.”

“I feel it’s a part of my duty as a shop owner to promote and preserve old music,” Derek said. “As well [as] make sure it doesn’t get lost or forgotten.”

- Derek McNelly, Record Parlor of Muncie owner I feel it’s a part of my duty as a shop owner to promote and preserve old music.”

collecting items has “worn off” and now views this as his everyday job.

-

Regardless, Rob said he has had many favorite encounters with customers, describing Dave’s Video as a “blast of nostalgia.” He explained that Dave’s Video has been here “forever,” saying the business “minds their own business” and “just treats people right.”

Upon entering Muncie’s Dave’s Video, the space is filled with a vast collection of film and music. Rows along the wall feature older film and video games and columns of bins are filled to the brim with CDs and cassettes. Customers line up with old pieces of media of their own to sell to the establishment, East Central Indiana’s largest selection of these materials, according to Dave’s Video’s Facebook page, hoping they one day become an item in someone else’s collection.