EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

JESSICA VELEZ

MANAGING EDITOR

CRISTAL MARIANO-VARGAS

CO-ASSOCIATE EDITORS

MACI HOSKINS

TRINITY REA

ARTISTIC EDITOR

BRENDEN ROWAN

PHOTO EDITORS

AALIYAH SANSONE

LEXIE HUYS

SOCIAL MEDIA

EDITOR

ENDIA SIMPSON

DESIGNERS

ANNABELLE PRICE

ANTONIA LIAKAS

BRENDEN ROWAN

CHRISTIAN MASON

JESSICA BERGFORS

OLIVIA MCSPADDEN

WRITERS

ANTONIA LIAKAS

CRISTAL MARIANO-VARGAS

DILLON ROSENLIEB

JESSICA VELEZ

LILLY ARNHOLT

LINNEA SUNDQUIST

MACI HOSKINS

TRINITY REA

PHOTOGRAPHERS

AALIYAH SANSONE

ANTONIA LIAKAS

BELLA NORRIS

CRISTAL MARIANO-VARGAS

LEXIE HUYS

OLIVIA MCSPADDEN

TRINITY REA

ADVISOR

COREY OHLENKAMP

April 2024

I walked into my first Ball Bearings meeting as editor-in-chief 30 minutes late and in a full-length dark blue gown. I’d left an awards ceremony early in hopes of catching one of the most crucial meetings of the year — our annual issue planning meeting.

I let my eyes travel along the white board of ideas the staff had brainstormed in the 30 minutes I wasn’t there for, and that’s when I saw it. Elements. A single idea that inspired an entire magazine.

January 2025

I’m not sure if anyone really enjoys coming up with story ideas, but when the opportunity finally came to rack our brains for elemental stories, the ideas flowed out. My staff and I imagined what the magazine might look like if it was brimming with stories on sustainability and the environment. Stories that highlighted the duality of our ecosystems and landscapes paired with breathtaking design and photography. But elemental could mean so much more. The possibilities were endless.

March 2025

The semester is in full swing, and our deadlines are quickly approaching. This is usually when the panic starts to set in a bit. March somehow always feels like the longest and shortest month of the year.

Our staff may be young, but they’re resilient. Interviewing and taking photos of strangers can be extremely intimidating, especially when it’s your first time doing it. Sometimes, designing your first spread can leave you feeling nervous and rattled. As an executive team, we did our

best to ensure that our staff gained confidence in themselves during this process and built bonds with them that extend beyond the Unified Media Lab (UML).

April 2025

In the span of three months, we put in endless hours to prepare for our three print weekends. During these print weekends, we spend 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. (hopefully) in the UML designing and editing our hearts out. We read and reread each page to catch every stray comma, every misspelling, and every design inconsistency. In the span of three weekends, and over 50 hours, we put together an entire magazine, and now you’re reading it.

I could never thank my staff enough for the work they’ve done these past two semesters. They’ve taken every challenge in stride and navigated the world of being ghosted by sources, having creative blocks from looking at designs for hours, and scrambling to book last minute photoshoots. Our writers, designers, and photographers worked tirelessly to make every element we needed to make the best magazine we could. No pun intended. Without them, Ball Bearings would be in shambles. Without them, I would be in shambles.

Thank you all for reading.

By Linnea Sundquist

Career day in elementary school was an exciting day for Jeremiah Mckeighen. He originally wanted to be a taxi driver because he wanted to “help people get around,” but his passion for assisting people soon developed into becoming a firefighter.

“I’ve always had a desire to help people,” Jeremiah says.

Jeremiah recalls attending a funeral for a local firefighter who had passed away, remembering the uniforms that the firefighters were wearing during the ceremony. He wanted to wear that uniform one day.

“I got to the point where firefighting and medical stuff is the best way I can do that,” Jeremiah says, now having worked for the Cowan Volunteer Fire Department in Muncie, Indiana, for about a year as a volunteer firefighter.

In Indiana, 72.6% of U.S. Fire Administrationregistered fire departments are volunteer-based. In 2020, of the 29,452 United States fire departments, only 18% of those departments were career or mostly career departments, according to the National Fire Protection Association.

To become a volunteer firefighter, volunteers need to take two classes in the state of Indiana, Firefighter I and II, in order to get certified. Students are taught fire science, fire extinguishment, search and rescue, ventilation, vehicle extraction, as well as many other topics. This class is taught two nights per week for five months for student certification. Students are also required to complete a medical class to acquire their medical certification.

The Yorktown Fire Department has been a volunteer fire department since 1913. The department has an average of 1,200 calls per year, providing services that range from basic life support, water rescues, structural collapses, emergency medical situations, and many other services.

Public Information Officer Blair Webster has worked at the fire station for two years and is in charge of all public media relations regarding the department. He is also a firefighter and EMT for the organization.

Blair emphasizes volunteer firefighters undergo the same training as career firefighters. However, according to the National Library of Medicine, volunteers do not receive a salary for their work, unlike career firefighters, but may receive certain benefits such as health insurance, life insurance, or other nominal fees.

After taking a public safety class at his local career center as a high school student, Jeremiah grasped an understanding of what it takes to become a firefighter. He says a lot of time is spent preparing to wear and lift the firefighter gear.

“A lot of training involves being able to go from clothes to full gear and ready to go on a truck in two minutes,” Jeremiah says.

Fire and Rescue and EMT instructor at the Muncie Area Career Center and Assistant Chief of the Yorktown Fire Department, Christopher Horner, has been teaching fire safety since 2009. Christopher says 25% to 30% of his students go into volunteer firefighting.

“[Instructors] are passing [training abilities] down in every succeeding generation, just better, and that gives me hope for the future,” Christopher says.

Christopher emphasizes the importance of teaching his students proper fire safety, after recounting a call he and his team took back in 2019 regarding a house fire. Three people lost their lives amidst the fire, causing Christopher to change the way he looked at his job. He shares that in his experience, firefighting was all “fun” until experiencing events that showed him “things are at stake.”

“It was kind of a sobering moment of, if things don’t go well, there are consequences,” Christopher says.

He continues to explain that he doesn’t want his students to go through something similar. To avoid this, Christopher says he does the best job he can to pass his knowledge on to the younger generation of firefighters, wanting to be that person others can “look up to.” Being part of a team and working together is how Christopher knows he can help people.

jobs, and it’s whenever people are available is when they’re able to make runs and make calls.”

Jeremiah shares that many volunteer firefighters with families sometimes have to bring their children to the fire station with them. As a single parent himself, Jeremiah says a personal challenge is making sure he is fit enough to do the necessary work for being a firefighter while also juggling parenting because he has a kid that “looks up” to him.

If things don’t go we , there are consequences.”

- Christopher Horner, Yorktown Fire Department assistant chief

“I need a team, and so my job is to create that team for myself and everyone else out there that needs it,” Christopher says.

Even though 70% of firefighters in the U.S. are volunteers, according to the U.S. Fire Administration, there are still challenges many of these departments face. According to Blair, a prevalent issue is recruiting people for their department.

“Some of the biggest challenges we face is getting people to come do this job for little to no money,” Blair says. “[Volunteer firefighters] have full-time

Seeing first hand how volunteer firefighting can impact families, the Cowan Volunteer Fire Department stresses keeping family a priority, and the department typically invites a spouse to come with their partner to the job interview so they fully grasp the impact that this job could have on their spouse.

“It could very easily be a call where a person doesn’t come back,” Jeremiah says.

Along with struggling recruitment for volunteer fire departments, departments often lack funding.

“Our budgets might not be as big as places around us, hence why we’re voluntary fire departments,” Blair says. “We’re blessed in Yorktown, [Yorktown] has funded us very well. There are several departments that don’t have quite the funding that we do.”

The International Fire Chief Association shared the average cost for full equipment is $9,410, not including many of the tools they need.

Christopher explains volunteer fire departments across the country are “nationally in trouble.” He emphasizes factors such as inflation, time management, and prior commitments, such as jobs and families, are making it more difficult to be a volunteer firefighter. Christopher expresses that he doesn’t know how much longer certain volunteer fire departments are going to stay volunteer, explaining that it just “isn’t cost effective.”

In 2023, Governor Eric Holcomb and the Indiana Department for Homeland Security secured state funding totaling $17.7 million for fire training and equipment, according to the Indiana Government website. While not all volunteer fire departments have

received funding, the ones that have are determined by how old their equipment is and if the department has a lowerincome than others.

Since many fire departments do not receive funding from the state, events and fundraisers help raise money for firefighters to get equipment and other things. Currently, the Yorktown Fire Department has no upcoming fundraisers, but the fire department has previously hosted 5K races as well as other fundraising events to raise money.

Blair also comments that the public doesn’t realize that the Yorktown Fire Department is a volunteer fire department. He says that “a lot of it is for at-home response” in regards to volunteers taking calls from their homes, emphasizing that volunteers are doing this work out of the “goodness of their heart.”

“They think that this is a full-time department with staffing 24/7, 365 [days],” Blair says.

Just support your local volunt r fire departments.”

- Blair Webster, Yorktown Fire Department public information officer

Hours for each firefighter vary by department, Jeremiah says. At Cowan, it depends on where you live in regard to the fire station. If a volunteer lives outside Cowan, that individual needs to dedicate around twenty hours a week to the station. If a volunteer lives near or in Cowan, they need to respond to at least 20% or more of calls, Jeremiah says.

While many volunteer departments are still trying to find new ways to improve funding and expand their budgets, Blair shared a little support goes a long way.

“Just support your local volunteer fire departments in any way you can,” Blair says. “Get out and help support these volunteer fire departments and your community.”

My identity isn’t a single story and neither is yours.

By Jessica Velez

Jessica Velez is a fourth-year journalism major and is the Editor-inChief of Ball Bearings Magazine. Her views do not necessarily reflect those of the magazine.

There’s something so beautiful about the crisp air of spring. The smell of flowers and mulch travels with you everywhere, and there’s a sense of new beginnings that feels inevitable. A forceful growth that feels petrifying like a spring-tide storm, but always brings out the brightest post-rain rainbows and with it, a better version of ourselves.

That’s exactly how the spring semester of 2023 felt, like a storm poised to rock my world. I found myself sitting in a small women and gender studies class tucked in the corner of the north side of campus.

We’d covered a plethora of important topics in the four-month span of the class. The kinds of topics that often left a pit in your stomach and brewed an anger that one could only describe as overwhelming. But we also spoke of acceptance and women who inspired generations of feminism.

On that beautiful spring day, sitting at an uncomfortable, small school desk, I learned about a topic that would forever change the way I viewed myself and everyone around me.

On that beautiful spring day . . .I learned about a topic that would forever change the way I viewed myself and everyone around me.”

- Jessica Velez, Editor-in-Chief

A simple word that represents so much.

The Oxford Dictionary defines intersectionality as the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender as they apply to given individuals or groups, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage.

To put it simply, intersectionality is everything that we are and everything we do that gives us privilege or leads to discrimination.

In our class, we were encouraged to dissect ourselves to better understand how intersectionality applies to our lives.

I’m a pansexual, able-bodied, afro-latina female born in the United States. There’s a lot to unpack in just that one sentence, but most of those traits come with their own challenges. Racism, homophobia, sexism and so many more “obias” and “isms” could follow me around for the rest of my life.

It’s incredibly difficult to sit in class and have the realization that everything you thought made you unique and powerful actually makes you vulnerable. The safest dissection for anyone is to be a straight, rich, white male. Everything I am not. Everything I will never be.

That is equally terrifying as it is infuriating.

The United Way of the National Capital Area recognizes that intersectionality has roots in the Black feminist movement of the late 20th century.

Scholars like Kimberlé Crenshaw used intersectionality as a way to highlight how systems of oppression intersect to create unique forms of discrimination that are often overlooked.

Crenshaw identified three distinct types of intersectionality: structural, political, and representational.

Structural intersectionality examines how various social structures and institutions interact to create unique forms of discrimination. For example, Black women are three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related complication than white women. A study done by Vanderbilt University assistant professor Rolanda Lister found that one of the main reasons for the high rate of maternal mortality in the Black community is due to racial bias from healthcare providers.

Political intersectionality investigates how political movements can fail to

address the needs and concerns of individuals with intersecting identities.

The 1920s women’s suffrage movement, which fought for women’s right to vote, excluded the voice of Black women who weren’t truly given the freedom to vote until the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, according to the California Commission on the Status of Women and Girls.

Representational intersectionality tackles how different groups of people are represented in different imagery, such as TV or social media, and maintains or challenges negative stereotypes. In her TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie unpacked how only seeing media coverage on Mexican immigration led her to see Mexicans as the “abject immigrant”.

Recognizing and defining these dimensions of intersectionality allows us to create more inclusive spaces and heal the deep wounds that marginalized communities have worn for years.

I’m now two years removed from that pivotal women and gender studies class, and the lessons I’ve learned on intersectionality will stick with me for a lifetime, but I’ve decided to take a different outlook on it.

We’re all multi-dimensional beings who have been taught that the closer we can be to uniform, the better the world will be. But intersectionality isn’t the problem. Our dissimilarities aren’t the problem. The problem is the people who decided to use intersectionality as a way to treat others differently.

It may seem outrageous for me to say that I love intersectionality because it implies that I love something that has led to the discrimination of people for centuries. But, at its core, intersectionality is simply our differences. It’s the things that make us distinct and extraordinary, and yet, it creates community bonds.

Spring is in full swing again. The crimson tulips on campus have bloomed, and the geese are running wild. The permanent smell of rain is in the air, and the days are windy enough to knock over lawn chairs. It’s time for a new beginning, and I invite you to recognize your intersectionality and celebrate it.

Celebrating intersectionality means valuing all of your identities and the way they shape your experiences and personalities.

I’m a pansexual, able-bodied, afrolatina female. I’m a journalist, a sister, an athlete, a yearner, but most of all, I’m human.

Who are you?

It’s the things that make us distinct and extraordinary, and yet, it creates community bonds.”

- Jessica Velez, Editor-in-Chief

F D INSECURITY RUNS D P IN MUNCIE, BUT CO UNITY E ORTS O ER HOPE.

By Cristal Mariano-Vargas

It’s a sunny afternoon in Muncie, and a local is gearing up for a grocery run. Bags in hand, they know this won’t be a quick trip.

“Delaware County has one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the state. . . and food deserts are particularly challenging,” Becca says.

The nearest grocery store is miles away, and without a car, the trip becomes more of a small adventure. A bus, a couple of transfers, a long walk — just to get to a store where fresh produce isn’t an afterthought. By the time they get home, the milk is warm, the bread is squished, and the produce is less than perfect.

The absence of accessible fresh food takes a toll on the community’s health.

Muncie, a city of 65,000 residents, has a growing issue that’s becoming increasingly difficult to ignore: food deserts, defined as an area where little fresh produce is available near residents’ homes.

Approximately 64% of Muncie residents live in areas considered food deserts, according to Muncie Neighborhoods.

Delaware County has one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the state... and food deserts are particularly challenging.”

“Limited access to fresh and healthy foods also contributes to the higher rates of diseases or chronic illnesses like diabetes, obesity, and heart disease,” Becca says. “... and those all also disproportionately affect minority communities.”

Becca Clawson, CEO of Second Harvest Food Bank, sees the impact of food deserts first hand in her work.

- Becca Clawson, CEO of Second Harvest Food Bank

Food insecurity often overlaps with broader health issues, and these chronic conditions are particularly prevalent in low-income and minority populations, according to the American Cancer Society. The society also found that low healthy food accessibility is prevalent in communities with lower life expectancy.

However, the issue goes beyond just the proximity of grocery stores — it is deeply intertwined with larger systemic challenges and social disparities. According to Feeding America, in 2023, it was found that 22% of Black people in the United States experience food insecurity, over double the rate of white people.

Marsh Supermarkets, once a staple in Indiana and Ohio, faced financial struggles that led to their bankruptcy filing in 2017. The closing of multiple Marshes in Muncie left entire neighborhoods without easy access to fresh groceries, further exacerbating the city’s food desert problem, Becca highlights.

Beyond food access, these closures had significant environmental consequences. The loss of nearby grocery stores forced residents to travel longer distances for food.

To help combat food insecurities, multiple organizations in Muncie have made it their goal to provide residents with the food they need.

Second Harvest Food Bank plays a huge role in addressing food insecurity in Muncie and surrounding areas, providing food to local organizations that serve the community in diverse ways.

By collaborating with organizations like the Ross Community Center and Open Door Health Services, Second Harvest helps meet immediate food needs while supporting efforts to address the root causes of food insecurity.

“We’re pushing for systemic change,”

(ABOVE) A worker on a forklift backs out from a trailer at Second Harvest Food Bank in Muncie, Ind. on March 27, 2025. Cristal Mariano-Vargas, Ball Bearings (LEFT) A group of volunteers and workers from the Ross Community in Muncie, Ind. helping unpack and load boxes with food on April 4, 2025. Cristal

Becca says. “Food access is a communitywide issue. It requires a multi-faceted approach to really tackle it head-on.”

Food insecurity exists because there’s not enough sustainable access to food.”

-

Becca Clawson, CEO of Second Harvest Food Bank

Becca highlighted the importance of supporting policies that improve food access, such as expanding Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits and improving public transportation. SNAP provides food assistance to low and no income people and families living in the United States, according to the Indiana Family and Social Service Administration.

Jacqueline Hanoman, the Executive Director of Ross Community Center, takes a distinctive approach to tackling food insecurity by focusing on education and self-sufficiency. Through the center’s community garden, residents not only gain access to fresh produce but also learn about nutrition, food preparation, and sustainable gardening practices.

“Food insecurity exists not because there’s not enough food. Food insecurity exists because there’s not enough sustainable access to food,” Jacqueline says.

This focus on education aligns with Second Harvest’s mission to ensure that food relief efforts are part of a larger strategy for long-term change. The Ross Community Center also aims to foster sustainable solutions.

“We have to get to the point in our society where it’s no longer needed, where lunch does not become an absolute necessity because [residents] can’t have it anywhere else,” Jacqueline says.

One of the initiatives they are launching is a program called “Cook and Thrive,” which focuses on communal cooking and education.

“We’re going to cook together and talk about how easy it is to make healthy [meals],” Jacqueline says.

This program aligns with Second Harvest’s goal of not only addressing hunger but also equipping communities with the knowledge and resources to maintain long-term food security.

To foster long-term food security and combat the negative health effects of food insecurity, Second Harvest also provides food to Open Door Health Services. Open Door is a nonprofit that provides primary, urgent, and preventive health services as well as select specialty services and social support programs.

Bryan Ayars, the president and CEO of Open Door Health Services, approaches food insecurity from a health perspective through its “Food as Medicine” initiative. This program integrates food access into healthcare by screening patients for food insecurity and providing them with nutritious food options to improve their overall health for low-to-no-cost. The initiative is rooted in the belief that nutrition is foundational to preventing chronic illnesses such as diabetes, which

disproportionately affects low-income communities, according to the American Diabetes Association.

“When people don’t have access to nutritious food, they can’t focus on anything else,” Bryan says. “It impacts their ability to go to work, their children’s performance in school, and their overall mental and physical health.”

Second Harvest’s partnerships with organizations like the Ross Community Center and Open Door Health Services represent a holistic approach to addressing food insecurity. Each organization focuses on a different

aspect of the issue — whether it’s providing shelter, supporting education, fostering self-sufficiency, or integrating food into healthcare.

These organizations continue to push for long-term solutions that will reshape food access in Muncie. As initiatives grow and partnerships strengthen, the goal remains the same: to build a network of support that goes beyond immediate hunger relief.

State theater profe ors describe sustainability e orts within the department.

By Dillon Rosenlieb, Cristal MarianoVargas

Ball Bearings Visual Editor Brenden Rowan is a part of the Department of Theater and Dance at Ball State University and approved the final design of this page, but was not involved with editing the story.

according to American Theatre. This initiative emphasizes reducing waste and making productions more eco-friendly, a movement that Ball State has begun to embrace in its own productions.

Sets are built, costumes are sewn, lights are rigged, and after the final performance, much of it ends up in storage or the trash. In an industry rooted in creativity and reinvention, theater programs are now beginning to confront the environmental cost of their craft.

Theatre has a history of contributing to environmental waste. From elaborate sets to staging productions that run for only a few days, the industry generates a significant amount of waste, according to the Theatre Greenbook.

One standout example of sustainable theater at Ball State was the 2023 production of “SpongeBob SquarePants,” directed by Andy Waldron. The production stands as a testament to the creativity that can be achieved and the obstacles that may arise when ecofriendly principles are prioritized.

However, a growing movement is changing that approach: Green theater. Green theater is an initiative focused on reducing waste and making performances more eco-friendly,

However, the process didn’t happen without challenges. Waldron noted that while student-made artwork added a unique touch to the set, it also slowed down the production schedule. The timing of when he could enter the art classrooms to gather the pieces was later than expected, which led to a sudden rush for materials.

The production team behind the show directed by Waldron collaborated with the art program at Burris Laboratory School, where students used everyday items — including anything from cans and bottles to paper plates and cardboard — to craft scenic elements.

“I prioritized these elements because I really wanted to engage area youth in the creation of this youth-forward musical. This not only establishes fun elements for the cast, crew and audience, but it also shows young people that their art is important, fun, and they can engage in the theater process,” Waldron says.

Additionally, Waldron made sure to save as much of the youth-created artwork as possible, giving the students the opportunity to take their creations home.

While this level of sustainability was possible through creative reuse and collaboration, there are various challenges that prevent these practices from being applied regularly, says assistant teaching professor of lighting design Corey Lee.

“A lot of what we do is we prep something that runs for a few weeks, and then we tear it apart,” Lee says.

He acknowledges that the custommade set pieces and materials used in many productions often cannot be reused due to their unique nature.

Lighting design also presents challenges, especially in terms of energy consumptions and the non-recyclable plastics found in gel filters, which are used to alter the color of stage lighting.

Lee points out that the energy use of traditional stage lighting fixtures contributes significantly to a production’s environmental footprint. However, with the advent of LED lighting technology, Lee sees a potential shift towards greener practices.

“LEDs save energy, they last longer, and they reduce the need for nonrecyclable gels,” Lee noted.

For Lee sustainability in theatre is about more than just reducing waste — it’s about education and giving back to the community. He not only says there is a place for public awareness about the harmful effects of pollution but also hopes to instill environmentally friendly practices in his students.

His goal is for them to carry these ideas into their work long after they leave his classroom.

“We just have to be aware of what all of this does to our environment so that we can leave a better place on earth for our children, grandchildren, all those that are yet to come,” Lee says.

Beyond Ball State, Lee has taken part in sustainable productions at the Fort Wayne Civic Theatre such as “Every Brilliant Thing,” a story that explores the complexities of mental health over a lifetime.

Behind the scenes, the theater put its best foot forward by being mindful of its material output throughout the production.

“Almost all of our props were paper, and could be recycled at the end of the production. Any paint that was used for the production was left over from other productions, and some things we already had. Our programs or playbills had a digital option so that we were able to reduce waste from paper copies,” Lee says.

For nearly 30 years, John Sadler has been shaping productions as the scene shop supervisor in the Department of Theatre and Dance. Incorporating eco-friendly practices into set design has become a natural extension of his approach.

Sadler teaches different approaches to the creative process while emphasizing the importance of reusability and sustainability in design.

For example, for one of his class projects, he challenges his students to make props out of found objects.

The green theater approach impacts waste management, sustainability, design, and production from a broader perspective, according to The Theatre Green Book. However, for Sadler, it ultimately comes down to the people involved and the materials they use.

“A lot of paints and things that we use are not necessarily great for the environment nor the humans that use them, and there are companies out there that are working on making better products,” Sadler says.

Major cities like New York and Chicago have theater organizations dedicated to sustainability, such as the Broadway Green Alliance. These groups promote eco-friendly practices, advocate for sustainable production methods, and highlight the benefits of incorporating green initiatives into the performing arts.

Sadler says these alliances benefit the

prop world because they encourage more collaboration between theaters.

“[The alliances] are working on creating a prop coalition where they have a shared set of props among multiple theaters. Instead of one theater owning 32 bentwood chairs and another theater owning 32 bentwood chairs, two theaters will own the same set of chairs, and they can kind of cooperate [with] each other,” Sadler says.

John Rawlings, the technical director for the Department of Theatre and Dance, plays a key role in set design for all productions. He oversees students as they piece together the elements of a production like a puzzle, each component contributing to the larger story. For Rawlings, a crucial part of that puzzle is finding ways to incorporate green theater principles.

“There was kind of a joke in grad school where it was like, [green theater] becomes popular about every four years. People like to talk about sustainability … sometimes the practices that you’re trying aren’t actually more green because their carbon footprint is bigger,” Rawlings says.

From a design standpoint, incorporating green practices can be challenging due to the wide range of materials involved in both the design and construction processes, says Rawlings. Balancing sustainability with the structural and artistic demands of a production requires careful planning.

“With scenery, we’re often building things that are not reusable, [meaning at] the end of the production, you end up having to throw out something. The way that I try to manage that is to use what we call stock, which are specific sizes,” Rawlings says. “We keep certain things around, and then we try to manage the build around what we have in stock ... that way, we’re purchasing less, we’re throwing less out, which lowers our footprint.”

Rawlings incorporates eco-friendly practices on set and in his classes, demonstrating various ways to repurpose materials creatively and sustainably.

“It’s not fun to throw away everything. It’s not a fun puzzle if, at the end, you just chuck all the pieces into the trash. I think it’s more fun to figure out how to make it,” Rawlings says.

Illustration by Jessica Bergfors

By Jessica Velez

A D P DIVE INTO HOW MUCH WATER IS USED TO MAKE EVERYDAY OBJECTS. A D P DIVE INTO HOW MUCH WATER IS USED TO MAKE EVERYDAY OBJECTS.

As of 2015, the United States uses 322 billion gallons of water per day, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. These gallons of water aren’t simply depleted from washing dishes or taking a shower. Most individuals have a hidden water footprint that contributes to the increased usage of Earth’s vital H2O. Whether it’s everyday household items, trendy clothing, or the use of artificial intelligence (AI), the amount of water it takes to create a single item or perform a single task may be shocking.

The average office worker uses 10,000 sheets of copy paper each year. The amount of water it takes to transport and wash the pulp used to make a crisp sheet of paper makes a bigger impact that some might suspect. The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has found that it takes nearly 47 gallons of water to make a ream of paper. Reducing paper use would not only save water but also reduces greenhouse gases because it minimizes the loss of forests. 40 reams of paper is around the equivalent of about 1.5 acres of a pine forest absorbing carbon for a year.

Regardless if they’re straight leg, acidwash, or mom jeans, according to the UN Environment Programme, making one pair of jeans takes around 3,781 liters of water. The large amount of water needed to grow the cotton and manufacture the product has left the denim industry known as one of the biggest water guzzlers. When a pair of jeans is being created it goes through four main stages: cutting, sewing, laundry, and finishing. The laundry process is what is usually the most water-consuming. A project led by Brazilian denim specialist Vicunha found that around 362 liters of water are used during the laundry process, and a single pair of jeans will see 460 liters of water solely from being washed by a consumer before it’s retired.

A typical Hershey’s bar is 1.55 ounces of pure sweetness. However, it takes approximately 180 gallons of water to make it. According to California Cultured, the water used in producing chocolate begins with the cultivation of cocoa trees, which are highly water dependent. One third of the water used in the entire chocolate production process goes to transportation and storage of the cocoa. Innovative companies like California Cultured are working to eliminate the need for traditional agricultural practices associated with cacao cultivation by farming inside under controlled conditions.

The shoe industry is the world’s largest user of leather, according to Is It Leather? Whether it’s a pair of combat boots or oxfords, a single pair of leather shoes can need up to 2,113 gallons of water to be created, according to the Water Footprint Network. While the actual creation of the shoes may not be the most demanding of water, The China Water Risk found 91% of the water used during the leather process actually comes from raising the cattle. The total water footprint of raising cattle for leather is 17,100 liters of water per kilogram of leather meaning one pair of leather boots uses enough water for a person to drink for 17 years.

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has estimated that there are around 11,000 data centers around the world. This surplus in data centers reflects the large increase in computational demands for AI. These data centers use water for a variety of reasons including cooling, electricity generation, and microchips. Because of AI’s inflated popularity, research has projected the global AI demand will account for 4.2 to 6.6 billion cubic meters of water withdrawal in 2027. That’s more than the total annual withdrawal of Denmark or half of the United Kingdom.

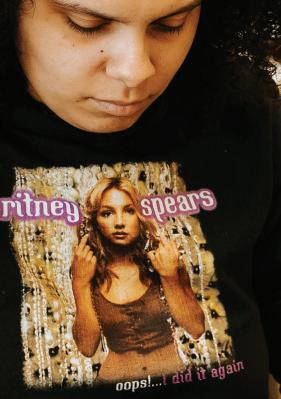

F.I.S.C. members capture the complexities of fashion.

By Jessica Velez

A strip of fabric. A single button. An extra zipper.

Living in a world where those items have creative value feels like a foreign concept, but for one special class, those scraps make all the difference.

Assistant lecturer of fashion industry studies Audrey Robbins saw a need for a creative hands-on construction course. Her students were constantly striving to reuse the clothing they had to construct new designs.

“Students were already saying ‘Can I reuse this pair of jeans and turn it into a skirt that I want for my line?’” Robbins says.

When the dean’s office opened up the opportunity for a one-time course to be pitched, Robbins wrote the proposal that eventually led to the creation of Fashion 299X — otherwise known as Recycled Runway.

The concept of Recycled Runway directly competes with fast fashion, the marketing of clothing fashions that emphasize making trends quickly and cheaply available to customers, according to Merriam-Webster.

Robbins emphasizes the average closet has enough combinations of clothes to never repeat an outfit in a three and a half year span. However, around 62 million metric tons of apparel are

consumed globally in a given year due to the popularity of trends, according to the Princeton Student Climate Initiative. When new trends are introduced and old ones are thrown out, 57% of all discarded clothing ends up in landfills.

“We are one of the biggest polluters in fashion,” Robbins says. “Not only are we wasting our original design, we’re wasting at the end of what we believe is the shelf life of a product.”

To combat this, Recycled Runway has taken a unique approach to fashion designing.

Using 100% free resources including donated clothing, swap and shops, and left over materials from previous projects,

students in the class are challenged to create two different looks from already existing clothing and fabric.

This has proven to be no easy feat. Junior fashion industry studies major Ivy Summerlot has created a clothing line titled “Trash is Art”, which aims to take someone else’s trash and give it another life. She shares that the class has taught the students how to be resourceful. If they can’t find the right fabric or thread color they need, students must get creative. Regardless of the challenges, Ivy shared that in her eyes, sustainability “is the future” and is slowly becoming the new normal.

“I’ve come to a point where I don’t really buy ‘new’ clothing anymore,” Ivy says. “Everything is thrifted, upcycled [or] bought second hand from Depop or resellers.”

As students become more conscious of the environmental impact of fast fashion, thrifting — or buying second hand — has gained traction in recent years as an alternative way to elevate a wardrobe. Junior fashion industry studies major Emily Hayes says the trial and error that students face with different creations in Fashion 299x has taught them how to be better thrifters.

Emily Hayes says the trial and error that different be

quality of clothing that already exists

“It’s really looking at the production quality of clothing that already exists and seeing what truly is great quality and what came from fast fashion,” Emily says. “[The class] helped me build my skills of identifying that.”

industries studies major Jakota Fischer. Both students played a large part in the planning and preparation for the class.

Emily works as a student assistant under Robbins along with senior fashion industries studies major Jakota Fischer. Both students played a large part in the planning and preparation for the class. conscious impact thrifting — or buying second hand —

During their research, they dissected the availability of textile recycling in the United States and learned there’s slim pickings.

Cities on the east coast, including New York, Maine, and Connecticut, have put the most money and effort into textile recycling, according to Promo Leaf, a environmentally conscious promotional product producer. While clothing can be shipped to these locations, the distance makes it more difficult for individuals in the Midwest who want to recycle their old clothing to have access to the resources they need for a responsible price.

For any true scrap fabric Fashion 299X can’t use, they’re recycling through a company called Check Sammy. The class paid for a box that can be filled with as much material as possible, and when it’s full, it’ll be sent back to the nearest Check Sammy location. Although the company offers free shipping, that singular box cost the class $300.

Despite the high cost, Emily

acknowledges the importance of having companies that are dedicated to recycling textiles because even donating your clothes to thrift stores could land them in a landfill someday.

As the semester comes to an end, as does this once-in-alifetime class. Having acquired 21 students to sign up for it in its first year, Robbins wants to pitch that it’s held every few years, if funds allow, to grant students an opportunity to explore the world of sustainable fashion.

“Sustainability can just be a buzzword, but we really have enough of this generation that really wants to invest in it,” Robbins says. “They want to learn more about it. They want to participate in it. They want the opportunity to learn more [and] to do better with it.”

“Sustainability can just be a buzzword, invest opportunity to learn more [and] to do

By Lilly Arnholt

Reduce, reuse, and recycle. This is something that many people have heard since elementary school, and, in some ways, they’ve taken it to heart.

While thrifting isn’t new, small businesses have begun thriving off of hand-me-downs, vintage aesthetics, and discounted pricing. According to a study conducted by Comillas Pontifical University economics and business administration professor Carmen Valor, used garments were seen as a low-status good, and, therefore were stigmatized.

After American thrift stores were first established in the late 19th century, the Salvation Army and many other Christian ministries found that they could use this as a funding source for their outreach programs. Today, well-known thrift stores like Goodwill, as well as the Salvation Army, contribute to the $53 billion that second-hand products supply to the United States economy, according to the Salvation Army.

During the time of World War II and the Great Depression, there was an influx of discounted clothing, which tended to be used. Poor economic conditions forced Americans to rely on thrift stores because it was the only affordable option.

After overcoming the economic depression, the Salvation Army records a decline in a desire to thrift. Being able to purchase new goods quickly became a reflection of success and wealth.

Today, the boom in popularity for thrifting can be attributed to three main causes: a crave for a unique style, a desire to be more sustainable, and, much like during the Great Depression, a need for affordable clothing, according to Haven House Thrift Store.

Because of the rise of the internet, the Salvation Army has found it’s easier than ever to buy second hand. Thrifting can be done online, thanks to apps such as Depop, Poshmark, and Thredup.

Despite thrifting apps becoming more prevalent, small thrift shops are

still popping up around the country. In Muncie, this is no exception.

Lily Brannon opened up Lily’s Labyrinth in the McGalliard Square Shopping Center in the spring of 2022 to “make some extra cash.” However, her experience with thrifting started long before that. With encouragement and donations from her friends, Lily was able to start building one of the most popular thrift stores in Muncie.

“I’ve hand-picked every piece and decided that it was cute enough for me to sell,” Lily says.

Another thrift store, Well Made Vintage is located in The Village. Anthony Edwards is one of the co-owners, and emphasizes that living a sustainable lifestyle means avoiding buying clothing from fast fashion websites such as SHEIN, a global fashion online retailer.

Muncie thrift stores work to give used items a second chance.

Being able to purchase all your kids clothes at a thrift store, as opposed to Walmart or Target . . . you’re definitely going to experience significant savings.”

- Leigh Edwards Vice president of community engagement at Muncie Mission

According to Earth.org, fast fashion is clothing that is made in mass quantities and follows a certain trend for the time it’s being made. It is meant to be sold for cheap and fly off of shelves quickly.

“I see when people do reels with their SHEIN hauls or [shopping] hauls from whatever other fast fashion brand, and those clothes not only are made by essentially slave labor, [but] those clothes within the first year, a lot of times, are already taken to a thrift store,” Anthony says.

In 2023, 24 U.S. Congress members wrote a letter to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, asserting that there was “scientific evidence” that SHEIN utilized cotton from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, claiming that it can be assumed to be forced labor.

Anthony also noticed that the quality of the clothing made through fast fashion, isn’t what thrifters are seeking. Their customers are looking for clothing that is made to last. Earth.org found that of the 100 billion garments produced in a single year, over 1 billion tons end up in landfills.

Despite the rise in more stylisticfocused thrift stores, there are many Christian-based organizations that run thrift stores. According to their website, Muncie Mission Ministries provides faithbased homeless shelters as well as family services, community meals, and addiction recovery. They also have five thrift stores located in and around Muncie.

Attic Window, their thrift store, accepts many donations, including household items, clothing, and even cars.

Leigh Edwards, Vice President of Community Engagement at the Mission, shared thrifting helps community members save money. When trying to help people get back on their feet, Leigh says saving money on clothing can be the difference between buying canned or fresh groceries for someone who lives below the poverty line.

“Let’s say we’re talking about a family

with kids, being able to purchase all your

with kids, being able to purchase all your kids clothes at a thrift store, as opposed to Walmart or Target . . . you’re definitely going to experience significant savings,” Leigh says.

Most of the clothing that is donated to the Mission goes to their programs and community members that may need it. Leigh says retail “gets second dibs.”

With the clothing that is too tattered to be brought into the programs or sold, Muncie Mission has a palletizer. It is used to make rags that are sold to bigger companies, which also fund the various programs.

It is used to make rags that are sold to set up programs that allow Ball State that are not given to the programs or are not sold in the thrift stores. One of the people she works with is assistant

Leigh also works in collaboration with Ball State Fashion Industries Studies to set up programs that allow Ball State students to work with the thrifted items that are not given to the programs or are not sold in the thrift stores. One of the people she works with is assistant lecturer of fashion industries studies Audrey Robbins.

Robbins is currently working on two different projects with Attic Window. One is a styling class, and the other is a special topics class. The styling class is focusing on taking pieces from Attic Window and turning them into outfits.

campaign

Window and turning them into outfits.

fashion social media pages,” Robbins

“Each group has a social media campaign they are creating, and they’re going to be shared on the Ball State fashion social media pages,” Robbins says. “It will be noted that you can buy those pieces at Attic Window.”

The special topics class is taking unrecyclable and unwanted items and completely changing them into something new. Robbins says, everything is 100% “recycled, upcycled, reimagined, [and] redesigned.”

The special topics class is taking unrecyclable and unwanted items and completely changing them into something new. Robbins says, everything is 100% “recycled, upcycled, it’s

Whether it’s a pair of shoes, clothing, or home furniture, the clothing that finds its way to thrift stores used to be loved by someone else and is getting a fresh start, says Leigh.

“Everyone and everything deserves a second chance,” Leigh says.

By Trinity Rea

In the heart of Muncie’s Blaine neighborhood on the southeast side of the city, 13 acres of overgrown land, garbage, and cracked slabs of leftover foundation lie behind a 12-foot barbed wire fence.

To the right of a padlocked entrance, a sign, defaced by graffiti, reads, “Future site of the Urban Training Farm. Please respect our boundaries while we clean up. Thank you!”

This sign has been hanging on the site for almost 10 years.

The site is home to a nearly 130-year-old history known locally as “Frank’s Foundry.”

While some members of the community experienced the challenges of the foundry first-hand, others who only know the now desolate site are hopeful that the once-booming foundry can again contribute to the east side in a new way.

I THINK IT’S AN AMAZING PART OF MUNCIE’S HISTORY. I JUST CAN’T WAIT TO SEE THE FUTURE.”

- Natalie Yates, President of Farmished board of directors

In 1898, Muncie Foundry and Machine opened on this site, owning only a fraction of the land now occupied today. Frank’s Foundry, which made iron castings for trucks, tractors, forklifts, and off-road construction equipment, purchased the original building in 1942. By 1948, the foundry had expanded to its current property.

Between 1959 and 1985, the foundry went by the name “Frank’s Foundries Corp.” Throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s, neighborhood residents began to complain that their homes and cars were being ruined by the foundry’s emissions. Because of this, Frank Foundry installed a scrubber system to reduce the site’s emissions around 1973.

A few years later, in 1977, the foundry experienced its first set of fires in the plant due to a small explosion, resulting in no injuries.

closed, leaving all 105 of the workers at the time jobless.

In 1989, Muncie Iron Works began operating at the site via loan but defaulted in 1991 and closed again, prompting the Blaine neighborhood to petition the city of Muncie to demolish the site.

After a few changes in ownership years later, the foundry was deemed “unmarketable” by a local appraiser.

Sometime between then and 1998, ownership was transferred again, this time to a felon who used the site to store waste, later being convicted for his crimes.

In 1999, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) deemed the site as an “imminent and substantial endangerment to public health, welfare, and the environment” and began to clean up the area.

In the end, the EPA removed more than 100 55-gallon drums of hazardous waste

THERE WAS A MI LE SCH L ACRO THE STR T, AND PEOPLE COMPLAINED ABOUT THE RESIDUES AND EMI ONS THAT CAME FROM THE FOUNDRY.”

-

James Walsmith, Former plant manager at Frank’s Foundry

In 2007, after the site had been left abandoned for a handful of years, the foundry experienced its second fire, which appeared to have been sparked by the use of a cutting torch, forcing firefighters to respond.

Two years later, a third and final fire broke out, prompting the city to issue a demolition order for the 10 acres of buildings on the site after they stood abandoned for decades.

Ninety-five-year-old James Walsmith worked at Frank’s Foundry as a plant manager for most of his life.

Walsmith started out at the foundry as a trainee, where he says he “unknowingly learned” the basics of casting manufacturing, climbing the foundry’s ladder to quality control superintendent, then plant manager.

“We had roughly 110 people in three or four departments. The core room, foundry, molding, melt, and grinding cleaning,” he says.

Walsmith lived roughly 18 miles away in Dunkirk, Indiana, traveling to and from the foundry every weekday, and on the occasional Saturday. While he says it’s hard for him to construct the details of most things during his time at the foundry, he remembers being consumed with union relations and strikes in the plant quite often.

In the ‘70s, Walsmith remembers when Frank’s installed its scrubber system to reduce emissions.

“The neighborhood didn’t appreciate [us]. We were in a neighborhood where there were houses and residents within a block or two, and there was a middle school across the street, and people complained about the residues and emissions that came from the foundry,” he says.

Walsmith said community relations at the time were rough. While community members “didn’t appear at the front door with complaints,” he said he would

know when complaints were being spread among neighbors.

When it comes to Farmished’s efforts to make the site something for the community, he remembers discussions of Frank’s economic impact being questioned, and is unsure of how practical a plan to reform the site can be.

“I wish I had a cheerier story for you, but people were probably glad to see it close,” Walsmith says.

After again passing through the hands of various owners, in 2014, the foundry’s then-owner donated two-thirds of the site to the nonprofit organization ‘Farmished,’ which acquired the last third of the land from the city of Muncie two years later.

Natalie Yates is an assistant professor of landscape architecture and planning at Ball State University.

With her research focusing on postindustrial landscapes, urban food systems, and technology in landscape design, Yates was drawn to Farmished and Frank’s Foundry a couple of years ago.

After being introduced to the board of directors`, she quickly began introducing her design students to the site, holding studio sessions and encouraging them to create proposals for what the site could become.

“My interest has always been about these abandoned spaces that have potentially problematic soil conditions and how we can think about remediating,” she says.

“People have ideas about what [Frank’s Foundry] should be and what it shouldn’t be … I want to see what we could do.”

photo of what remains of a structure on the former site

Gathering these proposals, Yates and her students held a presentation at Madjax Maker Force and spoke to community members and Ball State University President Geoffrey Mearns. She says “they were all very interested” in the potential of the site.

Because of this success, Yates was offered a position on the board, acting as a liaison between Ball State and Farmished. However, around 2017, while work on the site was running smoothly, the nonprofit started to falter internally.

In April of that year, the foundry was officially declared an “EPA Superfund Cleanup” site and the remaining buildings were condemned. Within a month, the structures and contaminated materials were removed.

Various other debris and objects were removed, including drums of wood stripping solution, asbestoscontaining roofing material in the soil, and buried waste containers.

A well on the property revealed that the site’s water had maximum lead contaminant levels, requiring capping, a process that doesn’t remove the water but isolates it to avoid the spread of contamination.

The cleanup effort resulted in 5,648 tons of material debris removed. In addition, 110 gallons of wood stripper solution, 10 gallons of waste capacitor oil, and 31 capacitor carcasses were removed. 500 gallons of liquid were pumped from an underground storage tank as well.

Two years later, in the fall of 2019, Farmished was issued a letter from the

Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) confirming the cleanup was successful and that, with restrictions, the site met “applicable residential cleanup criteria.”

PEOPLE HAVE IDEAS ABOUT WHAT IT SHOULD BE AND WHAT IT SHOULDN’T BE.”

-

Natalie Yates, President of Farmished board of directors

stepped down.

Yates didn’t want to see Farmished or the foundry project end and agreed to take on the role of President at the nonprofit. She then formed a new board a few months before the pandemic, which has gained and lost members fairly consistently.

Yates says, “everything just kind of fell off,” and that she and her board haven’t been able to get anything going again.

On the Farmished website, this is where the nonprofit ends its updates.

Between cracked foundations, vegetation has grown rampant over time on the site. Cottonwood trees litter in and around the property, some atop 30 to 34-foot hills of cast-off foundry sand. Remnants of site walls are left over here and there.

To Yates, this means that currently, the site is in its “eyesore phase.”

Farmished got its name from a play on words, farm and famished, aiming to address Muncie’s food insecurity in hopes that Frank’s could become a community garden. Overall, the organization wants to provide some of the missing links in the local food network.

Meanwhile, Yates said the board of directors slowly began to disassemble.

“There [weren’t] a lot of meetings. The current president was out of town a lot, so it just kind of began to slow down … it was kind of unsure where [Farmished] was going,” she says.

Soon after receiving the letter from IDEM, the president of the board

Farmished has begun to operate with some other local organizations, taking advantage of the holes on the site left from the EPA cleanup.

Yates said one of the holes is filled in and will be used theoretically for composting of organic matter.

However, Yates says due to regulations and city ordinances, it’s not a feasible strategy, which isn’t the organization’s only problem with its vision.

“Moving forward, there are some more stipulations, of course. If you want to plant in the ground, you have to bring in clean soil, 18 inches, or it has to be in raised beds on top of the [leftover] foundations, which are serving as a cap. If you want to remove any of the soil from the site, then that has to be disposed of properly,” Yates says.

Fifth-year landscape architecture student at Ball State, James Durango, is basing her master’s comprehensive project on the foundry site’s potential. Durango knew before landing on the foundry that she wanted to tackle Muncie’s food insecurity with her project.

“I’m aware that, in my life, I’ve been very privileged to have access to fresh food and vegetables. When I was a kid, my mom had vegetable beds, and we would eat fresh tomatoes and fresh cucumbers, and that was really nice,” she said. “Not everyone has that, so it’s something I’ve been passionate about for a long time.”

According to Second Harvest Food Bank, 16.7% of Delaware County residents face food insecurity. This means that every day, 18,760 people don’t know where their next meal will come from.

With this in mind, and the fact that Muncie is a food desert, meaning parts of the city either lack the income or the accessibility needed to eat healthy

foods, Durango took on the project with three goals: cultivating, cooking, and community.

“[The plan is] to educate people on how to grow their own food, educate people on how to take that food and cook with it or preserve it, and then also making the space into a community space,” she says.

She quickly discovered that reforming industrial sites into something like a community garden has not been done before. Similar projects mainly consisted of taking industrial sites and turning them into parks.

Regardless of whether or not Durango had somewhat of a blueprint, she was ready to tackle the project and its issues of cracked foundation, unplantable soil, and present habitats on the site.

“Do I really want to tear [trees] down just to grow food there when it’s already being productive [for the environment]?” Durango says.

have all spent on the site cleaning up,” Yates says. “... It’s a fairly cumbersome job, money’s an issue, and it’s hard to ask for donations of any sort when you don’t really know your way forward.”

Yates is exploring different options of how to move forward, funding-wise and is hoping to get the nonprofit back off the ground again soon.

Durango hopes that Farmished will be able to move forward, but in the meantime, she says she hopes activity on the site doesn’t inspire anything dangerous.

“Gravel has been put there to fill in the trenches and, well, yes, they’re mainly stable, but there’s a possibility of air pockets, and if you step on the gravel, those air pockets could cave in,” Durango said. “... Be aware that, while it looks abandoned and mainly all the structures are gone, it’s still dangerous.”

Additionally, the site runs right along the Cardinal Greenway, which Durango details connecting to in her project. Realistically, she faces a barrier in doing so because of the abnormally large hills between the trail and the site.

She says that she hopes something will be done on the site in the near future, but the lack of funding hinders the foundry’s potential to do so.

In terms of the ‘What now?’ question, Yates says Farmished needs to step back and start over.

“We just need a reconfiguration, we’ve spent the majority of the time that we

Wherever Farmished takes the foundry project, Yates just hopes the site can one day become something special for the community.

“I always have high hopes and high love for that area and that particular site. I think it’s an amazing part of Muncie’s history. I just can’t wait to see the future,” Yates says.

BA STATE HAS A COMPLEX RELATIONSHIP WITH RECYCLING.

Illustration by Antonia Liakas

By Antonia Liakas

Less than a mile south of Ball State’s campus lies the White River where over 65 tons of trash have been removed in the past 13 years, according to the Muncie Sanitary District (MSD).

All around Ball State’s campus, located near trash cans, are bins lined with bright blue bags, serving as visual reminders to students that they can choose to recycle any paper, plastics, and styrofoam.

But Ball State’s relationship with recycling is complex. While the university website encourages students to recycle, it emphasizes that if any of the materials in the recycling bins are contaminated with leftover foods, liquids, or chemicals, they will be rejected from the recycling process.

David Williams, a senior animation student at Ball State joined the oncampus organization called the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), along with a handful of other students. The organization’s mission is to host audits, assessing Ball State’s sustainability using a system called S.T.A.R.S. — Sustainability Tracking Assessment and Rating System.

common throughout the landscapes he has explored, including a recent trip he took to Florida.

“There was litter and trash everywhere,” Ben says. “I saw a crab carrying a piece of trash with him like a bottle cap … I thought that was a little sad.”

If you think about it all... where is that going to go?”

- Ben Jones, Wildlife biology and conservation major

Great Lakes every year, which provide drinking water for 40 million people.

Mathew Simpson, assistant lecturer of natural resources and environmental management at Ball State University, studies pre-production microplastics and their distribution across various ecosystems.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, microplastics are tiny plastic particles, less than five millimeters in size, that originate from either the breakdown of larger plastic items or are intentionally manufactured as small particles.

One of Simpson’s main concerns is that plastic particles are being lost in transit between facilities and enter the environment. Simpson describes a time he visited the Great Lakes and says around the coastline “every step you take, you see them on the beach.”

David highlights Ball State’s grade for S.T.A.R.S. is gold, which is ranked as the second-most efficient class. However, according to the ranking, there is still room for improvement.

Wildlife biology and conservation major Ben Jones says recycling plays a big part in how humans interact with animals’ habitats. Ben has spent years immersed in the outdoors through camping, hunting, and fishing. Although he’s enjoyed several remarkable, upclose encounters in nature, he expresses the upsetting reality of litter being

Ben brings attention to the ample amount of plastics essential to our everyday lives. This includes temporary items such as plastic silverware, sunglasses, phone cases, straws, plastic wrap, toothbrushes, and credit cards.

“If you think about it all … where is that going to go?” He asks. “A lot of it is going to end up in the ocean, unfortunately.”

For those residing in the Midwest, like Ben, it’s easy to overlook the major impact these plastics have on oceanic environments, considering their disconnection from coastal biomes. However, copious amounts of litter still impact Midwest communities.

According to the Rochester Institute of Technology, more than 22 million pounds of plastic pollution end up in the

Muncie is no exception. A study conducted by Notre Dame doctoral student Blessing Yaw Adjornor and various Ball State professors, found 2,499 microplastic particles per kilogram of sediment in the White River.

“There is no place on this planet that microplastic has not been discovered,” Simpson says.

micro-scale, it is ever-present in Muncie.

takes a small step to recycle, it can positively impact the

Whether or not the plastic is on a micro-scale, it is ever-present in Muncie. However, Simpson asserts if everyone takes a small step to recycle, it can positively impact the planet in large ways.

Recycling has proven to be much more complex than some might think, David says.

“The reason why is not because Ball State is not trying to recycle,” suggests David. “It’s that the recycling system, almost nationwide, is confusing.”

David also suggests that recycling is very “nuanced” and students that are new to campus may struggle with getting into the habit of recycling. He emphasizes that it’s difficult to get it right every single time.

Almost every one of these reusables require a bit of prep before tossed in the recycle. Food and beverage containers must be emptied completely, rinsed, and dried prior to entering the bin, otherwise they are no longer suitable for the recycling process.

The same goes for cleaning products or detergent containers. It is crucial for them to be free of any soapy, chemical residue. Oftentimes, recyclable components are accompanied by plastic or paper labels that need to be cut or peeled off prior to the bin.

Different organizations such as Republic Services provide helpful tips on how to contribute from home. They encourage consumers to identify if the item can be reused or broken down in a landfill. Most recycling services accept plastic, cardboard, glass, metal, aluminum, and paper.

The MSD also provides a “how-to” guide for recycling where they not only share what items they will recycle, but they also share how the recycling of one item can positively impact the environment.

Notably, the MSD only recycles number one and two plastics and discourages recycling ceramic mugs, plates, crystal, and window glass.

While recycling may take conscious decision making, David stresses the importance of learning the ritual of recycling.

David says.

“Education is the first step,” David says.

By Maci Hoskins

Charlie Cardinal is stuck out in the elements! Fi in the blanks to help him return to The Nest.

(CAMPUS LOCATION)

(PRESENT TENSE VERB)

(ADJECTIVE)

(BALL STATE FACULTY MEMBER)

(ONOMATOPOEIA)

(VERB ENDING IN -ING)

(VERB ENDING IN -ING)

(PAST-TENSE VERB)

Charlie is on his way to _________. He just left the Brown Family Amphitheater when it started to rain! He reached into his _________ to grab his rain jacket. He _________ when his feathers get _________. Out of nowhere, a __________ lightning bolt flashed right next to __________, and he knew he would need more than a rain jacket. Hurriedly, he _________ behind the recycling bins near Bracken Library. Thankfully, Charlie spotted __________ coming to his aid. Together, they were ___________ when they got stuck behind the Ball State bus. To get their attention, Charlie yelled, “__________!” The bus stopped, ________ the __________ and they hopped on. Outside, leaves were __________ and the sky was getting _________. As they drove off, Charlie _________ his feathers and sighed. Thank goodness for the Ball State Bus!

(NOUN)

(ADJECTIVE)

(CAMPUS LOCATION)

(PAST-TENSE VERB)

(VERB ENDING IN -ING)

( PLURAL NOUN)

(ADJECTIVE)

DOWNLOAD THE MITSBUS APP TO STAY CONNECTED