E mihi ana ki ngā tohu o nehe o Whakatū

Tū mai rā Maungatapu

Rere atu te Mahitahi

Puta atu ki te Aorere

E mihi ana ki ngā Iwi Mana Whenua

Acknowledgements to the ancestral and spiritual landmarks of Nelson Maungatapu (mountain) stands forever Mahitahi (river) flows

Flowing into Tasman Bay

Acknowledgements to the tribes who connect to this land

The First 20 years of the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary

A history of a significant Nelson environmental project from the first suggestions of the idea through to proof of the concept with the first successful reintroductions of endangered native species 2001 – 2021

Michael Murphy 2024

Foreword

Kia Ora.

Twenty years ago a group of Nelson conservation leaders had a dream: to build a wildlife sanctuary in the hills surrounding Nelson City, to reintroduce new species that were there once and to eventually see those birds fly into the city as a symbol of what could be possible with dedicated conservation leadership and the power of volunteers, corporates, local government, the Department of Conservation, Iwi Whenua and hapu all working together.

When I first met Dave Butler, who was chair of the Sanctuary Trust, we were in a remote part of Fiordland on a photographic mission where he shared this inspiring vision. The idea was to capture the hearts and minds of a whole city to transform the way the locals felt about their patch of steep bush clad hills forming such a superb backdrop to one of New Zealand’s best located cities.

After 20 years of hard work, the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary has done this in droves. From the establishment of the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary Charitable Trust in 2004 to the huge job of building one of New Zealand’s most challenging predator free fences, to being declared pest free in 2019, the bulk of the work has been done above all by an incredible network of volunteers.

The leadership of the Trust must be acknowledged for the fundraising, the strategy and the relationship building that enabled such a venture - quite often in the face of opposition. The venture has survived record floods and threats of fire.

The incredible growth in supporters, the QualMark certification, the revamped visitor centre, the Biosecurity Plan all signal success. You have pulled it off and made so many New Zealanders and international visitors immensely proud of what you have done. Today it is the best place in New Zealand to see orange fronted parakeet/ kākāriki karaka. Soon it will be the best place to see kākā, little spotted kiwi/pukupuku and tuatara all due to the incredible dedication of so many volunteers. Thank you for all you have done for Brook Waimārama Sanctuary - it is so appreciated.

Nga Mihi

Lou Sanson Patron

Introduction

When I joined the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary community project in 2017 I was struck by several distinct characteristics from other conservation activities: the complexity of the Sanctuary project and the dedication displayed by a large pool of volunteers who supported the notion of restoring an ecosystem in the Nelson hills.

Since 2004 the Sanctuary project has benefitted from the dedication to the cause by many individuals and entities that have all helped shaped the Sanctuary and its supporting organisation today. The best way for me to explain this dedication is to reflect that in 2022 the Sanctuary trustees wanted to recognise the long-standing volunteers who have shown consistent commitment to the Sanctuary by creating an honours board and offer lifetime subscriptions as a token of giving something back. Nicknamed the Tuatara Club, one of the criteria to entry into the club was to have served as a volunteer for over 15 years. As of 2024, we have 60 club members, most who still pay their annual subscription regardless. It’s this sort of commitment that makes a strong backbone to an organisation’s framework that in turn helps trustees, staff and supporters achieve the vision of restoring an ecosystem.

The initiative of promulgating this book was based on capturing some of the stories and experiences through volunteers that have been associated with the project throughout its first 20 years and describing the Sanctuary’s evolution over this initial establishment period. This record should acknowledge the hundreds of thousands of hours volunteers have spent working on the project. Not surprisingly the text for the book contents took over a year to compile and edit from many interviews and records. Mike Murphy a long-standing volunteer stepped forward to take on the task and we thank Mike for that. Many volunteers who are quoted requested that they are not mentioned because they thought that would be unfair to so many who are not mentioned but who have given so much.

We do hope you enjoy the collection of stories and recollections that describes the formation of an important regional asset and draws the reader closer to the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary.

Richard (Ru) Collin

Trustee 2017-2019

Chief Executive 2019- present

Overview

This is the remarkable story of the creation of the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary that grew from an idea in a casual conservation to a thriving environmental project enclosed by a pestproof fence more than 14 kilometres long enclosing around 690 hectares of rugged countryside and which carried out its first reintroductions of endangered species 20 years later.

The site that the Sanctuary now occupies was, from 1863 until 1941, Nelson City’s main water supply catchment and it remained in service until 1987. Its Reserve status protected much of it from direct human modification, particularly its upper reaches that are covered with beech forest typical of that found in the neighbouring Richmond Ranges and in the Nelson region in general with small pockets of southern rata, matai, miro and rimu along with a few large totara.

Despite the lower, northern slopes of the valley being heavily infested with invasive introduced plant species and the understory being ravaged by goats, pigs and other ungulates, researchers who conducted a professional vegetation survey of the valley concluded that it could provide “excellent potential habitat for a wide variety of indigenous flora and fauna including species that were currently extinct or very uncommon at the site.” (Van Eyndhoven & Norton, 2004).

Van Eyndhoven & Norton, 2004

In 2023, members of the staff weeding team updated the list of plants found in the Sanctuary from the 250 species recorded in 2014/15 to a total over 330 that include:

• 237 species of native trees, shrubs, mistletoe, vines, ferns, orchids and grasses.

• 100 exotic species.

Sometime in 2001, a couple whose property is on the lower western slopes of the Brook Waimārama Valley in Nelson, had the idea that a fenced ‘mainland island’ wildlife sanctuary could possibly be created next door in the water catchment Reserve. They were conservationists at heart as was he by profession, and he began progressing the idea with his first newsletter circulated in January 2002. Conservationist friends and other interested people began to join them, an article about it appeared in The Nelson Mail and the first public meeting to attract supporters was held at Nelson’s historic Fairfield House.

With the word out, a second public meeting to attract volunteers to work in the project was held at the Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology (NMIT) where the large group who attended were asked to put their names down on lists for a range of activities that would be required. However, on-the-ground operations could not begin until permission was received from the Nelson City Council, which owns the land. Consequently, the enthusiasts who had put their names down on the various team lists heard little for another year or two while the founding group established an Incorporated Charitable Trust that could obtain a lease over the Reserve and gain permission to commence operations. The Trust was established in 2004 with invitations for representatives on the Board from the Department of Conservation (DoC), NMIT, Nelson City Council (NCC) and the several iwi present in Whakatū/Nelson.

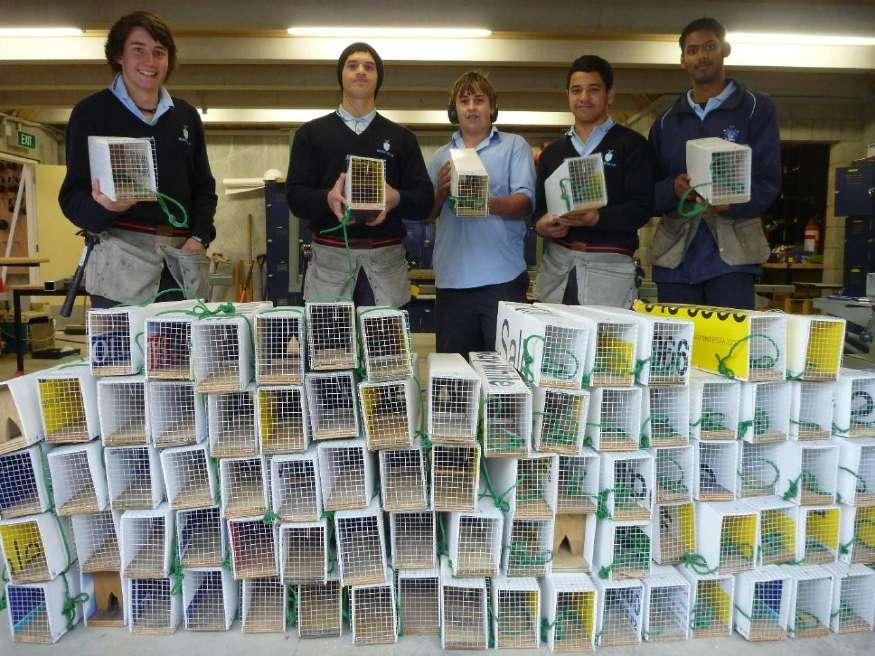

The first trustees then set about the tasks of fund raising, publicising the project and working with the first volunteer teams, the managers of which were volunteers who had simply put their hands up to take those roles. The first teams included track cutters to begin on the operational tracks that are necessary for trapping, pest monitors who established separate tracks along which to monitor predator activity, and trappers to reduce predator numbers. Ad hoc working parties were convened to build traps and monitoring tunnels and the need for other teams became apparent for roles such as to publicise and recruit at public events, monitor the bird life in the Reserve, establish a seedling nursery and begin weeding out the invasive plant species that were abundant in the valley.

A Visitor Centre building was completed and opened in 2007, and the Board gradually shifted from management to governance with the appointment of the first paid staff. In 2012, a General Manager was appointed to lead operations and take an active role in fund raising for all activities, the most cost intensive being the proposed pest fence. The data gathered from the monitoring and trapping operations contributed to the process of obtaining Resource Consent for the fence and with the necessary and substantial funds raised, fence construction began in September 2014. It was completed almost exactly two years later.

The next essential stage was the removal of the mammalian predators within the fenced area, which included mice, rats, mustelids and ungulates including goats, pigs and deer. The first group had been being trapped since operations began and the second group had been hunted but substantial numbers of all species remained, and the data indicated that populations of at least the first group would remain unless eradicated with poison bait.

The process of obtaining Resource Consent for an aerial drop of poison bait was obtained but then legal opposition was mounted by a group that represented itself as being residents in the Brook Valley although only some were. That resulted in an unexpected and costly sequence of court cases that took a lot of time, dampened momentum and enthusiasm, and consumed substantial financial resources. The Sanctuary eventually won all the court cases, and the predator removal process was able to proceed, albeit after a violent and destructive protest that delayed the first aerial drop.

Following the pest removal, the process of reintroducing endangered species was begun although they were delayed because of incursions of rats and weasels that took considerable efforts to remove but which provided much learning regarding how to manage such unwanted arrivals because they inevitably occur from time to time in ‘mainland island’ projects. Finally, in 2021, the first reintroduction of tīeke, the South Island saddleback, occurred followed by the highly successful reintroduction of kākāriki karaka which have since flourished. An introduction of one of New Zealand’s rarest snails, Powelliphanta followed in 2022. The goals of the long and arduous project were finally being reached.

The Brook Waimārama Sanctuary project has depended throughout on the manifold and monumental efforts of the many trustees who have served on the board; the Sanctuary staff; the generosity of members of the public, family groups and charitable institutions; corporate sponsors; governmental contributors both local and national; and many hundreds of volunteers contributing many tens of thousands of hours of their time.

Volunteer hours totalled around 28,000 hours in 2023, and a volunteer survey conducted in 2020 found that about half had volunteered for at least four years, the average time spent volunteering averaged ten hours per month, ranging from less than five to more than 30 hours, and around 75 per cent indicated that they expected to stay in the same role for a similar numbers of hours per month.

By that time, the first few volunteer teams had been added to or had differentiated into two of three so that the total stood at 14 teams. In alphabetical order at the time of writing, they were Assets, Bird Monitoring, Events & Promotions, Fence Checking, Fence Maintenance, Guided Walks, Monitoring Support, Pest Monitoring (Perimeter, Response & Sanctuarywide), Planting, Track Maintenance, Visitor Centre and Weeding.

Several volunteers, including some ex-trustees, were among the more than 30 people interviewed and are therefore mentioned along with others, but hundreds who have given immense amounts of time and effort are not mentioned. Similarly, it is almost certain that some smaller projects conducted by some of those volunteers during the first two decades will have been overlooked or not brought to the writer’s attention.

While an appendix of all volunteer names was considered, attempting to compile it would have the attendant risk that some would be unintentionally omitted. Adding to that, some specifically requested that their names were not to be included. Of note, it was not uncommon during the interviews to have the interviewee comment, “I don’t know why you’re interviewing me. I haven’t done much.” Yet, by the end of the interview, they would have disclosed that they had helped on several teams and on many occasions and perhaps led a team or instigated some project of other.

There have been and are hundreds of humble heroes who helped to make a brilliant idea into a magnificent reality, and it can only be hoped that this anonymous reference to them conveys some of the appreciation for their efforts that is felt by so many.

The Concept is Born

David and Donna Butler owned and lived on a property that adjoins the Sanctuary’s lower western boundary. Previously, they had lived in Wellington for a while and had friends who were involved in New Zealand’s first ‘mainland island’ sanctuary, Zealandia in Karori, which was also developed within an old water catchment reserve and reservoir. Donna had grown up in Nelson and was familiar with the old Waterworks Reserve because her family, like many in Nelson, had made regular use of the swimming pool in what had once been the waterworks reservoir for birthday outings and other recreational visits to the bush and the track up to the early dams and weirs.

Dave had had a long involvement with environmental projects and met Derek Shaw when they were both working at St. Arnaud under a Lands & Survey scheme in which Dave was conducting bird surveys and Derek was writing route and track descriptions for brochures. They were both active committee members of the Nelson branch of Forest & Bird and Dave became the chair of the branch for a while. He then became involved in the Mainland Habitat Island Project at Lake Rotoiti/St. Arnaud and learned by disappointing experience how difficult it is to control predator numbers without a fence to keep them out. Although predator numbers could be suppressed at times through trapping, a mast (seed) year in a beech forest provides so much food for them that numbers increase dramatically and can take the project back to where it started.

Regarding the initial idea to develop the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary, Donna recounted, “We were just talking idly when we were visiting my younger brother, who was a birthday boy up The Brook, and I thought it would be a neat place have a sanctuary in Nelson. It would be very similar (to Karori). It's an unspoiled piece of New Zealand native bush. From then on, I did very little but my late husband, David, was very much a conservationist and he got fond of the idea. We had a walk up there, all three of us through the bush and took a dog or two because it was easily accessible. We walked up one of the spurs right through the middle of it early on and saw the huge potential. We also saw how much goat and pig damage, and presumably deer damage, that was done and how many pigs we encountered on that one little walk. From then on, Dave took the bit between his teeth and went for it. I just saw the similarities between the two sites, really. Both are city reserves, and this is a nice, enclosed area.

“I wasn't aware of a lot of the details that seemed to consume an incredible amount of time, but it was virgin ground, really. Nobody had done a similar thing here, so it was breaking new territory, new ground. The people doing it, Dave and the others involved, hadn't done anything like this before. I think one of the first other people on board was Derek Shaw, who we knew anyway. Very early on, they had a public meeting at Fairfield House and to Dave’s surprise it was incredibly well attended. I don't know all who were at that meeting but there were a lot of very enthusiastic people although nobody had any expertise in the field. Derek had been a Nelson City councillor, so he had a bit of an in with the Council, but I think they found working with the Council an extraordinarily difficult process.

“Curiously, the Council had this land sitting there riddled with pests and a private hunting place for a local neighbour and it was just going to rack and ruin. Here was a willing group of

volunteers to look after this land and remove pests, which was a national strategy at that time in New Zealand and an obligation for the Council to do anyway, so the early lack of support was a surprise. However, some councillors really, really wanted the Sanctuary and I am sure some staff did, too.

“That meeting got the ball rolling and then they started fundraising. They had quite a good supporter who really got on to Dave that you couldn't fund-raise for the project unless you had resource consent that the project was available. So, there was all this difficulty - which came first – fund-raising and getting people on board. These were essentially a bunch of amateurs doing this and getting the Resource Consents to use this piece of land was an extraordinarily difficult thing to do. I think they had to change a bit of legislation to use it. All the reserves in New Zealand have different status and what can be done with them and what can't be done with them, so the whole legal thing had to be done by Council. That was a time consuming and tricky process for everybody.”

Derek Shaw recounted his memory of the first meeting with NCC staff, “There was a group of us got together in 2001 in a meeting room at Council. About half the room was full of Council staff and I was a councillor at the time, and other people outside like Dave and several others who had got involved in the project such as Earl Norris who was also on the Forest & Bird committee. Earl had worked as a school science advisor and was leading the weed control efforts and involving various school groups in the Marsden Valley Scenic Reserve project. We thrashed around the idea and agreed that it was a very good idea and then, in good Kiwi fashion, all those that weren’t Council staff were deemed to be on an interim steering committee.

“We kicked off that way because it was a potential conflict for the Council staff. We set up a process of meetings and discussions on how we’d further the idea. It took until 2004 before the Trust was formally established but we started attracting a whole lot of volunteers who started working on various aspects of the project. There were teams that were starting to work on the ground. Peter Hay was probably one of those early ones who wanted to get in there and start doing some tracks, facilitate trapping and all that.

“We gave a lot of thought to what we could provide in the Brook Valley, particularly in terms of making the existing tracks in the valley floor more accessible and adding new tracks, as well as opportunities to see and appreciate the historic dams and other water supply infrastructure. There were close similarities with the Karori Sanctuary (now Zealandia) in a former water supply catchment in Wellington, so we invited Jim Lynch, the founder of the Karori Sanctuary over to Nelson to speak at a public meeting. He's written up his own version of Zealandia’s history. He visited the upper Brook Valley before speaking at a packed meeting in the Council chambers and declared that we were four or five hundred years ahead of Zealandia because we had intact original forests whereas theirs was pretty modified and was just regenerating.”

While Dave Butler and his growing team of supporters embarked on the legal and political processes involved, news of the proposed project began to reach the public domain. On 30 January 2002, Dave produced the first newsletter titled Brook Bulletin No. 1, and on 18 February, The Nelson Mail published an article about a proposal for a ‘mainland island’

sanctuary in the Brook Valley Water Catchment Reserve. That publicity drew around 70 people to a weed control working bee in October.

In January 2003, the second newsletter, titled Leaves from the Brook, appeared and contained evidence of the substantial work that was already being undertaken. Plans to form a charitable trust to govern the project were announced and it was reported that meetings had been held with the Brook Motor Camp management and with NMIT regarding possible collaboration with the Institute’s Trainee Ranger programme. The development of educational resources was mentioned and, looking well ahead but clearly with an informed understanding of what was going to become a major financial and engineering undertaking, discussions had been held with Xcluder regarding the eventual construction of a pest fence around the Reserve boundary. Those who had organised the October 2002 weeding bee that had attracted so many volunteers were mentioned and included a representative from NCC and a weed specialist from DoC.

As Derek Shaw recalled, “They (Nelson City Council) must have been favourable to us doing the work even before we were formally set up as a trust. There was support for the idea from key Council staff. I can't remember what stage it formally went to Council for approval but there was probably provisional approval for the concept initially which gave us encouragement to set up the Trust. We weren't a legally constituted organisation at that point, but they gave us enough positive feedback so that we could get going within the Sanctuary. I think that happened at various levels because there were staff who were responsible for the Council Reserves and there would have been people who would have done the interaction with Council staff regarding conditions for things like cutting tracks because, obviously, it does have its own impact.

“There was a series of papers that went to the Parks and Reserves Committee that I sometimes went along to. I was never on the committee, but I took an active interest and liaised with staff at times. Various staff members were positive and there were some on board who appreciated the biodiversity aspects of it, who were personally supportive of it and helped facilitate it. We had to go through a formal process at one point of getting a lease. One of the reasons for forming the Trust was so that we could take over the lease.”

David Butler became the first chairperson of the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary Trust and held that position until 2019. Derek Shaw took the role of acting Chair at times when David was away.

Issues 3 and 4 of Leaves from the Brook in March and June 2003 give an insight into the breadth of thought and effort that were already being given to the concept. An Orientation Day at NMIT on 2 April was reported and volunteer categories offered listed: weed control, plant propagation, monitoring of birds, invertebrates and reptiles, publicity, membership support (a database had already been created), financial management, construction of equipment and infrastructure, education, research history, pest control, track marking and construction, fund raising, plant survey, tourism liaison, social club, hosting visitors, research liaison and legal, health & safety, insurance and security. Also mentioned was progress with forming the Trust, fundraising and a report that the materials and construction of the pest

fence would total an estimated $2.2 million, an amount that was somewhat optimistic alongside the eventual cost many years later.

In August 2004, Issue 6 reported that the Trust had been incorporated and that those involved could now “get down to business”. A call was put out for volunteers to help with publicity, fundraising and education and it was announced that operational activities could begin including working with Nelson City Council on cutting the first trapping line tracks.

The operational ‘getting down to business’ evolved out of early meetings of several enthusiasts. As Dave Leadbetter recounted, “I got involved with Pete Hay and Tom Brett and Karen Driver. We used to have monthly meetings. They were great because they are all doers. Everyone was a doer. I was a representative of the Trust, and they were volunteers. We were all volunteers. And we used to meet at various pubs around town. That was great. Just ‘to do’ lists. Tom said, ‘I'll do this.’ And Pete the same. We decided we needed to look at trapping lines because we had no idea what was up there.” Dave himself took responsibility for the running the trapping programme and, as an example of the improvisation that was necessary, sometimes taught new volunteers how to operate DoC200 traps during the evenings in his medical consulting rooms.

As Tom Brett recalled, “At the end of the trap making programme, I remember Dave Butler approached us and said that we needed three groups. One was tracking cutting. One was monitoring the traps and doing the training. And the third one was pest monitoring. So, I took the trapping, Karen Driver took the pest monitoring and Pete Hay took the track cutting. There wasn't much democracy. We just agreed that we wanted to do it. We were interested and nobody else was putting their hand up, so we went for it.” As Karen put it, “Tom said to me, ‘Oh, would you like to set up the pest monitoring?’ and I said, ‘I don't know anything about pest monitoring, but I'm interested to talk about it.’ I ended up setting it up in late 2006.”

Peter remembered, “We initially made up it up as we went along. Trustee Dave Leadbetter used to attend to make sure things didn’t get out of hand. That was crudely how it started but it steadily became far more complicated as time went by. I remember going to a field operations meeting and by then it’d built up so something like 20 to 25 people used to come to the meetings. There were about four or five representatives from the trapping fraternity for example, all with slightly different ideas so it could get quite chaotic at times.”

Alastair Wiffen, who took over the role of organising key volunteers from Dave Leadbetter, also recalled those early pub meetings. “Key volunteers used to have meetings I think on a Wednesday night at the pub, usually at Milton Street. That included Tom Brett, Karen Driver, Peter Hay and Torsten (Kather), and a few others like Ro Pope would come and we would say, ‘This is what we're doing’. We were reporting back to the Board in an operational sense of what was going on so that was the first interaction with the Board that we were having or reporting to. Dave Leadbetter was looking after that. It was early days of trying to work out who could have what role. At that stage, Dave (Leadbetter) was being made a trustee.”

The August 2004 newsletter also reported on the launch event held earlier in the year with Mike Ward MP and the Wizard of New Zealand in attendance. Archdeacon Harvey Ruru was

also in attendance and reported that, “They wondered how the Reverend Harvey Ruru would cope with the Wizard being there at the same time channelling his wizardry and me channelling the spirituality. We both got into a banter, and it was a very, very happening, happy opening.”

Issue 6 also reported that there had been a fund-raising event at Fairfield House with an art exhibition of work by Daniel Allen, Marilyn Andrews and Dean Raybould from which the artists donated proceeds. There was a performance by the Mosaic Choir at the launch of the event and wine was donated by Woollaston Estates. Phillip Woollaston, a former Minister of Conservation and Mayor of Nelson City, agreed in 2007 to be the first Patron of the Sanctuary Trust. Also reported was that a local architect, John Palmer, had provided concept drawings for an Entrance Building/Visitor Centre that would also provide a base for Sanctuary staff and volunteer operations.

Following repeated feedback that the proposed sanctuary was one of Nelson’s best kept secrets, the Trust decided to produce a booklet to help outline the vision and provide information on the site’s natural and historical values, the challenges of building a pest-proof fence and the plans for subsequent restoration and reintroductions, plus how people could contribute and what could be seen when taking a walk. Local journalist, Jacquetta Bell, was commissioned to write the text and Derek Shaw agreed to publish it under his Nikau Press publishing business. The result was a 32-page A5 booklet titled Returning Nature to the Nelson Region.

Through the tireless efforts of the growing number of key people, the dream was beginning to be realised.

Historic Structures

The Nelson Waterworks

In 1856, the Nelson Provincial Government enacted the Nelson Improvement Act to establish a Board of Works with powers to construct and maintain, among other things, “wells, tanks, reservoirs, aqueducts and other waterworks as they shall think proper for supplying the inhabitants of the town with water”. An amendment to the Act in 1858 gave the Board powers to borrow money for projects including “supplying the inhabitants with pure water”.

In 1863, the General Assembly of New Zealand repealed The Nelson Waste Lands Regulations Amendment Act, 1861, and relevant sections of the Schedule to the Waste Lands Act, 1858, in order to enact The Nelson Waste Lands Act, 1863, which established a Waste Lands Board consisting of the Superintendent, the Commissioner and the Speaker of the Provincial Council, any two of whom could constitute a quorum. The Board had the power to create reserves for many purposes including “any purpose of public profit advantage utility convenience or enjoyment.” The Board also had powers to sell waste land and to purchase land not open for sale and pay compensation for any existing improvements on that land. It could lease unused land to licensees for prospecting, mining and grazing stock. That same year, the Nelson Provincial Council enacted the Nelson Waterworks Act to “make provision for the making and maintaining Waterworks for supplying the City of Nelson with Water … from the Brook Street Valley”.

On 9 May 1865, The Nelson Examiner published a report by the Provincial Engineer, Mr. John Blackett, in which he outlined his proposal for the Nelson Waterworks to be constructed in the upper Brook Valley. The report refers a reservoir that was to be supplied from a dam that was to be constructed in the Brook Stream. The reservoir, as well as storing a supply of water, had the additional purpose of letting silt settle before the water was piped down to the town. The proposed reservoir, would “contain a supply equivalent to forty days’ consumption at the rate of 40,000 gallons (182m³) per day.”

Blackett’s proposal also included a weir or dam about 42 feet (13m) higher in altitude than the reservoir, with a 12inch (30cm) cast iron pipe down to the reservoir, 7-inch (18cm) pipes from there to the town and a road to the reservoir. “This is not intended to dam back a supply, but to form a basin from which the pipes will lead, and which will keep them always full. The dam will have an overflow channel large enough to carry

the water in time of floods, and a discharge pipe by which the water may be let off for cleansing.”

On 16 September 1865, The New Zealand Government Gazette (Province of Nelson) gave notice that, under The Nelson Waste Land Act, 1863, “all the Crown Land included within the watershed of the gorges of the Brook-street stream and tributaries; bounded on the southward by the ridges of the hills forming the said watershed, and on all other sides by the sold lands” was reserved for the purposes of the Nelson Waterworks. The sold lands referred to a parcel on the western side that was purchased from Alfred George Jenkins and another on the eastern side above the Dun Mountain Railway line that had earlier also been owned by Jenkins but which he had sold to the Dun Mountain Copper Mining Company.

It appears that, at that time, the Reserve did not include the lower northern part of the catchment that includes where the first waterworks facilities were constructed and the present area of the Brook Motor Camp. Jenkins had earlier owned those parcels, but both were later owned by Alexander O’Brien. Deeds relating to the sale of those parcels to Nelson City were not lodged until 17 June 1895 and 6 May 1905. The lodgement dates of Deeds do not necessarily provide the actual date of the transaction but clearly the City had the power to plan and begin construction of the waterworks by 1865 when the Nelson Provincial Government enacted the Nelson Improvement Act to establish the Board of Works.

The entire project of constructing the reservoir, weir/dam, access roads and pipe reticulation to the city was designed and overseen by Blackett who reported on 13 April 1868 that the works had been completed, that the dam had been filled several times and full pressure had been laid on in the pipes. Although costing £300 less than the budget of £20,000, the project had taken around two years longer than expected.

The Waterworks were officially opened on 16 April 1868. The opening was declared a public holiday and was celebrated by a procession to the reservoir and back to the Government Buildings in Bridge Street where a speech was made by the Superintendent of Nelson, Mr Oswald Curtis. Bishop Suter composed a prayer and a hymn for the occasion. The Nelson Examiner of 18 April 1868 reported that, in relation to the dam, the reservoir stood “on a piece of table land about a quarter of a mile lower down the valley and thirty-four feet below it in level.” The eventual form of the reservoir was an oval, in-ground tank that was about half the size originally proposed but which could hold 775,000 gallons (3,523m³)around two weeks supply for the city at the time. For many years after it was decommissioned as part of the city’s water supply, it was used as a swimming pool by Nelson residents and visitors when on outings and picnics. The circular rim of its southern end is still visible in the upper part of the Motor Camp area.

There was a significant earthquake in Nelson on 19 October 1868 and there were reports of damage to the waterworks structures. A noticeboard that once stood by the footbridge below the 1904 Big Dam stated that the original reservoir located in the stream above the Big Dam was shattered by an earthquake shortly after its construction. However, the ‘reservoir’ that was consistently referred to as such by the Provincial Engineer was on the “table land lower down the valley”. To confuse matters more, a pamphlet once available from Nelson City Council stated that the Circular Basin in the Brook Camp was built in 1874 to replace the original, earthquake-shattered ‘reservoir’

However, in his annual report of 4 May 1869, the Provincial Engineer informed the Provincial Council that the earthquake had indeed damaged the reservoir but only enough to “increase the small amount of leakage which had previously occurred. To remedy this …(I) had the whole of the inner surface of the walls well pointed and faced with cement. This was attended to with good results, and the new works appear to stand well.” This is not a description of a structure that was “shattered” and needed replacement. Since the Sanctuary project was launched, the trustees, staff and volunteers assumed that the dilapidated stone weir with its pipes and rusted control valves in the stream some distance above the 1904 Big Dam was the 1868 “stone weir” that had supplied water to the reservoir. However, in 2014 a group of track cutters decided to clear vegetation from some mysterious pits in thick bush near the old track beside the stream and discovered a line of large, shaped rocks laid across the stream directly below. It quickly became obvious that those rocks were part of the foundations of the original, 1868 dam that had been

“shattered” by the earthquake whereas the more intact one further upstream was its later replacement. It is also likely that the Provincial Engineer was consistent in his use of “reservoir” to describe the large, oval settling tank whereas the term was possibly used less precisely on the noticeboard and in the pamphlet to refer to the structure further upstream that was shattered. Furthermore, the pamphlet stated that the replacement structure was completed in 1874 which is a date consistent with the time it would take to plan and construct a second dam/weir in the stream and therefore might well be the date of the weir remnants which still stand.

The remains of the second (c.1874) weir/dam (2012 Sanctuary photo competition)

On 6 December 1900, The Nelson Evening Mail printed a report by Mr R.L. Mestayer, a consultant engineer from Wellington, in which he examined several options for a new, larger dam to supply the City’s increasing demand for water. The option chosen is what became known generally as ‘the Big Dam’, the imposing remains of which still stand beside the Visitor Centre. It was estimated that a dam 50 feet high at that location could hold 40 million gallons (181,843m³). This would be enough to provide 650,000 gallons (2,955m³) per day for 120 days, even during a severe drought such as the city had experienced in 1895.

Ultimately, the new dam constructed in 1904 was three quarters the size of that recommended by Mr. Mestayer. On 13 February 1905, The Colonist reported that the new water supply had been connected into the newly completed eight-inch (20cm) main on 11 February 1905. The concrete dam was 12 metres high and 94 metres long and cost £11,571. It was one of the first of its kind in New Zealand and was the tallest until the 27m high Upper Karori dam was built in 1908.

The 1904 dam (Nelson Provincial Museum)

By 1908, the dam had developed serious leaks and on 12 February 1908, The Colonist reported that it had been emptied for repairs and the old, higher dam had been cleared of debris so that it could once again provide the town’s water supply. During the new dam’s construction, the concrete had been hand mixed using crushed rock from the stream and a nearby quarry, and contained many voids that led to the leakage. It remained empty until 1911, by which time the inner face had been re-mortared at a cost of £2,418. Unfortunately, it continued to leak, although not as badly as earlier.

By March 1909, a dam had been constructed 150 feet (46m) above the level of the 1904 Big Dam at a cost of around £2,000 and it supplied the city while the repairs to the Big Dam were completed. It is commonly referred to as the ‘Top Dam’ or the ‘1909 Dam’ and was described as 71 feet (22m) wide and 39 feet (12m) high. The water was 23 feet (7m) deep at the weir and 12 feet (3.7m) deep at the top end, which was five and a half chains (110m) upstream. It provided a reservoir of four million gallons (18,184m³). Water was delivered via an eight-inch (20cm) asbestos pipe and the added altitude enabled water to be delivered to higher levels in the town.

There are also the remains of a smaller weir, generally referred to as the ‘Top Weir’, further up the stream and connected with riveted spiral iron pipe that is covered by a concrete path in places. It is thought that it was constructed around the time that the 1909 Top Dam was the sole water supply. It is possible that it was used to divert water from the 1909 structure while it was being built and that diversion enabled later maintenance of the dam which

repeatedly filled with gravel. Both structures filled with gravel during the 1970s floods rendering them unusable for water storage.

The remains of the top weir with pipeline leading from left of picture

During the 1920s the water supply from the Brook Dam was proving inadequate and bores were sunk near Normanby Bridge (Aratuna) in Bridge Street near the Queen’s Gardens to

provide additional supply. In 1922, a £20,000 loan provided for new water mains from the Brook Dam, which increased the dam’s output fourfold but emptied it four times as rapidly.

On 27 July 1934, The Nelson Evening Mail reported the Brook scheme’s delivery capacity at 682,000 gallons (3,100m³) per day.

On 29 January 1937, The Nelson Evening Mail reported that the Brook Dam could supply 600,000 gallons per day and the weir could supply 500,000 gallons (2,273m³) per day. At the time, an additional 200,000 gallons (910m³) per day were obtained from a pumping station in Hanby Park, although there were concerns about the quality of the water taken from the Maitai River. Once again, residents were complaining of poor supply, and it was asserted that larger mains were required to deliver more water from the Brook Dam.

An article in The Nelson Evening Mail of 25 August 1938 mentions that Cummins Creek, which is the first tributary into the Brook Stream below the Brook Camp, was also brought into the system at some ‘later’ time and provided an additional 80,000 gallons per day. The remains of a dam or weir, along with valves to control the supply are still evident up in the creek. Iron pipes were run from there back up to the reservoir to supplement the supply to the city.

The Roding River water supply scheme was chosen as the next water source and was completed in 1941. On 2 April 1947, The Nelson Evening Mail reported that the Brook scheme was capable of 700,000 gallons (3,182m³) per day, of which 500,000 gallons (2,273m³) could be delivered in 12 hours. At that time, the combined output of the Roding and Brook schemes averaged 15 per cent overcapacity for the water requirements of Nelson, Stoke and Richmond.

As a further source of water for the rapidly growing city, the Maitai South Branch project was completed in 1963, by which time that supply and the Roding scheme provided three quarters of Nelson’s water. Because of safety concerns, the level of the Brook Dam was lowered by two metres in 1964. It was lowered a further three metres in 1980 and the completion of the Maitai Dam in 1987 rendered it obsolete. In 2000, it was totally decommissioned by a further lowering of its level.

The Dun Mountain Railway

The eastern boundary fence of the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary is positioned below and more or less parallel to the walking and cycling trail along the old Dun Mountain Railway from near Third House in the south-east to where the trail crosses an old firebreak known as The Classic that goes up the Fringe Hill. Appropriately, that intersection is known as Four Corners and from there, the Sanctuary fence follows the downhill section of The Classic to not far above the Brook Motor Camp and the Sanctuary Visitor Centre.

The history of the Dun Mountain Copper Mining Company and its railway are well documented, but a brief summary is given here because of its prominent history in the Brook Valley and its proximity to the Sanctuary fence.

In 1854, capital was raised in England to improve access via the Maitai Valley to the mineral belt that includes the Dun Mountain. In 1856, 16 tons of high-quality copper ores and 15 tons of chrome ore were brought out by pack horse. In 1857, the Dun Mountain Copper

Mining Company was registered in London, with capital of £75,000. In 1858, materials for the railway line from the Brook Valley began to arrive in Nelson, although construction was delayed due to the extent of the copper deposits being questioned.

The extraction of chromite, which was used for dyeing cotton yellow and mauve, continued by packhorse via the Maitai Valley but in 1860, the price of chromite rose significantly and the decision to build the railway was taken. Construction of the 13.5-mile (21.7km), threefoot-gauge (914mm) line began in March 1861. The point where it began to climb from the Brook Valley is well marked and from there it climbed the eastern side of the valley at a gradient that enabled empty wagons to be pulled uphill by horses. From the Tantragee Saddle, it continues above the valley until it crosses the Third House Saddle (also known as Wairoa Saddle) into the Roding Valley, around Wooded Peak and ultimately to Coppermine Saddle. It was New Zealand’s first railway. The full wagons travelled down in pairs under gravity with brakes to slow their descent. There were seven houses along the line, with stables at Third House.

The extent of the chromite deposits was considerably overestimated and barely 40 per cent of the railway’s carrying capacity was utilised during the first year. Output diminished significantly so that by 1865, the extraction of chromite had ceased. The company used the railway to deliver firewood, timber, slate and limestone to Nelson, and operated a passenger omnibus service from the Brook Valley, through the town to the port. However, its affairs were wound up in 1872, although the passenger service continued for many years, including excursions to the mines. The lines through the town were pulled up in 1907.

A conservation plan was prepared by Ian Bowman in 2011 and updated in 2022 for the purpose of recording and preserving the water structures. In 2023 a walking trail called the ‘Heritage Walk’ was initiated to highlight the infrastructures and their history.

Coal Mining

There was coal mining in the Brook Valley on two sites just below the Waterworks Reserve during the 1890s and some of the land on the eastern end of the 1904 Big Dam was earlier leased to one of the coal mining ventures.

In 1858, Alfred George Jenkins opened a coal prospect on his Enner Glynn property on the southern foot of Jenkins Hill and it was realised that the seam followed the Waimea Fault into the Brook Valley where coal had been found as early as 1853.

In 1894, several citizens who lived in the Brook Valley formed the Brook Street Coal Prospecting Association to prospect on a farm owned by James Wilson Newport on the eastern side of the Brook Stream north of the waterworks reservoir. Several drives were started into the hillside on Cummins Spur below older workings but only the first one was continued, a two-and-a-half foot (76cm) seam having been found. However, the coal proved to be of limited quantity and the company had difficulty raising further capital. It wound up on 29 April 1895.

Meanwhile, another prospecting venture, known as the Jenkins Hill Prospecting Association, was launched in October 1894 to prospect on the western side of the Brook Stream opposite the reservoir. The property had been formerly owned by Alfred Jenkins but was by then

owned by a relative, Alexander O’Brien. A steeply dipping seam five feet (1.5m) thick was discovered and by the end of January 1895, a timbered shaft went in 130 feet (40m) and 30 tons of coal had been stockpiled. By March, the drive extended 162 feet (49m), but the most profitable seam was located 70 feet (21m) in although it was almost vertical. The coal was of good quality, but a horse-drawn whim was required to lift it out.

By October 1895, mining consultants estimated that there were up to 4,320 tons of coal immediately available and the seam had been widened to 13 feet (4m). The Jenkins Hill Prospecting Association formed the Enner Glynn Coal Mining Company (the Brook Valley name was already taken) in order to raise capital. A new shaft was sunk 60 feet (18m) lower and nearer to the Brook Stream. It was taken down to 183 feet (56m) and a drive was started from the 160-foot (49m) level. Although some coal was extracted, the new shaft was not a success until early in 1897 when good quality coal was found in workable quantities. However, sales did not go well and the company remained short of capital for development and, to make matters worse, the seam pinched out a short time later.

A fire destroyed the coal shed and screen on 15 January 1898, and on 21 June a fire broke out in the mine so that it had to be flooded. When the mine was pumped out, it was discovered that the main drive had collapsed. On 29 August, an extraordinary meeting of shareholders voted to sell the mine which was eventually purchased by another coal mining interest which did so only to obtain the plant. The company was wound up in March 1899. The mine had produced 1,337 tons of coal.

The entrance to the lower mine is within the northernmost corner of the Sanctuary’s pest fence across the Brook Stream from the Brook Motor Camp on the flat area near the bottom of the old Western Firebreak.

The Big Vision

From the very beginning, the founders saw the Sanctuary they were planning as part of a much bigger picture that included the halo effect it could have on the surroundings including the Mt. Richmond Forest Park to the east and south, the Bryant Range/Dun Mountain area to the east and Nelson City to the north, south and west. They also discussed ideas regarding how the Brook Motor Camp could complement the Sanctuary project and how plans to work with NMIT and its Trainee Ranger programme could lead to a Conservation Education Centre nearby.

The ’Halo Effect’ and Beyond

Derek Shaw elaborated on the envisioned ‘halo effect’ and beyond. “Part of our vision was not only the wildlife corridor from the Sanctuary down the Brook Valley, but it was also about birds flying out of the Sanctuary and repopulating Mt Richmond Forest Park. We were promoting those points at the Nelson Biodiversity Forum, of which the Sanctuary Trust was a founding member, and Dave and I were regularly going along to the Tasman Biodiversity Forum as well. We were trying to spread that bigger picture vison across the Top of the South. Dave spent quite a bit of time thinking about that and talking to the Project Janszoon people. They were similarly wanting to undertake restoration in Abel Tasman but also to have that spill over in all directions.

“Our vision of a corridor down the Brook Valley was to link the Sanctuary to people's backyards so that you might experience some of the birdlife that they didn't see at that point. There was a conscious effort to try and encourage people to do trapping and restoration projects, on the Grampians, the Centre of New Zealand and some of the other Council land on the eastern hills. We always saw it as a community project. I think Dave articulated that really well when speaking to outside people, telling them that this was a community project because it was so close to the city and depended on hundreds of volunteers. That was the labour force.

“Some of the Council owned eastern hills adjacent to the Sanctuary and down the Brook Valley were in pine plantations, so we made representations to try and ensure after the pines were harvested that they were replaced with native vegetation.

“I kept having ideas about linking large areas of native forests with biodiversity corridors. When a member of the Nelson Conservation Board, I had prepared a Board submission to The Tasman District Council that focused on the St Arnaud area and how corridors could link Nelson Lakes National Park with the Big Bush Forest and the southern end of Mt Richmond Forest Park, including maintaining or re-establishing links through the areas of private land between these large areas of public conservation estate. The concept of corridors came out of the controversial proposed Beech Scheme on the West Coast during the 1970s, when they were referred to as ‘wildlife corridors. They were essentially the same thing as biodiversity corridors, an area where native wildlife could move back and forth between large areas of indigenous habitats.

“Dave and I would often have discussions about such linkages and after ear-bashing people over several years, I ended up putting a paper to the Tasman Biodiversity Forum. This

detailed how the large conservation areas across the Top of the South, including Mt Richmond Forest Park, Nelson Lakes National Park, Kahurangi National Park and Abel Tasman National Park could be linked through biodiversity corridors. Then along came even bigger picture thinking – Kotahitanga mot e Taiao Alliance which involves iwi, five councils, the Nature Conservancy and central government agencies, such as DoC, and various community agencies such as Forest & Bird and the Sanctuary Trust working collaboratively to restore and enhance nature across the top of the South Island, including Kaikoura and Buller.

“The Nelson Biodiversity Forum came about when I was chairing the Environment Committee at Council. It involved some 25 interested organisations including NCC, DoC and the Sanctuary Trust, who I represented, working together to come up with an agreed strategy for enhancing biodiversity within the NCC administered area and take responsibility for actions where they could. The strategy was reviewed every two to three years and eventually Council and DoC started working together and the Nelson Nature programme was established. One of the projects was termed the Halo Project around the Sanctuary and was designed to improve the habitat around the Sanctuary’s pest fence so that birdlife that flew over the fence had a better chance of surviving. Fortunately for the Trust and Council, the Dun Mountain mineral belt area to the east was ranked by DoC as a site of national significance and they put resources in to help get rid of the pest animals like deer, goats, pigs and some of the pest plants.”

Rachel Reese, who served as a Nelson City councillor for six years from 2007 and then became Mayor from 2013 through to 2022, also talked about a bigger vision within the region. “I started to have some conversations with Eugenie Sage (Minister of Conservation and Associate Minister for the Environment from 2017 to 2020) around whether there was interest in seeing whether we could have a Regional Park established across the full Sanctuary and the Maitai right up to the mineral belt. I still think that's got legs. I think that area has the potential, just as the Abel Tasman has with the Nelson Lakes and Kahurangi, and that would be a big process as part of Kotahitanga mō te Taiao. It fits well in there. So, we started the move from seeing the Sanctuary in isolation to seeing the Sanctuary as part of that bigger landscape transformation.”

Kate Fulton, who served as a Nelson City councillor for 12 years up until 2022, commented on how such expansive visions during recent years have been accompanied by a major shift in how many people see environmental protection compared to years ago. Her grandfather was instrumental in helping establish the Abel Tasman National Park and she said, “Conservation was around setting aside pieces of land to remain pure and untouched but then you could exploit other pieces of land and that was OK. This piece of land’s being put aside from my fishing or my hunting or my nature walks. That was the mindset of the 20thcentury environmentalist, and I think it's shifted because now we think about the environment in our backyard. How much concrete have we got? How many indigenous plants have we got in our garden? How many bee-friendly plants have we got? How many of those are pests? What are we doing with our road reserve? That's quite a big shift. It was that you protect stuff which is still worth protecting - just - and then the rest of it we don't really care about what happens and we don't realise how important it is for humans to be connecting into the natural world environment every day.”

Nick Smith, who served as Nelson’s Member of Parliament for many years and at times was Minister of Conservation and Minister for the Environment, also discussed how the wider understanding of conservation in New Zealand has shifted over the years. “I remember in the 60s, 70s and 80s, the biggest issue was habitat protection. For 100 years, the biggest threat was loss of habitat and then people were saying, ‘Well, it’s actually the stoats, the ferrets, the possums, the cats becoming the greatest threat.’

“We'd started from the 1970s with the idea of eradicating pests on small islands and New Zealand was at the forefront of the technology internationally and gradually growing that, and then this idea came about what are called ‘mainland islands’. Could we develop either what are called ‘soft barriers’ or ‘hard barriers’ to create mainland islands? One of the mainland islands was at Lake Rotoiti and when I talk about soft barriers, it was around having intensive trapping around the margins of an area to create an island free of pests. So, you can imagine, having been up to my eyeballs in all of that work nationally, when a group of enthusiasts approached me around 2000 to say, ‘How about the opportunity in Nelson up the Brook?’, I became a convert for the proposal right from the word go.

“The key elements that I have been involved in, and I never want to take away from David Butler and the founding team who did the hard mahi, but always saying, ‘You're on the right track. This is absolutely what Nelson needs. This is achievable.’ Then in terms of helping persuade the Council to do the agreement about the management of the reserve. Then helping satisfy both funders and the community that the technology could work to could create a predator-free fence. Then persuading Prime Minister John Key and the team for us to put in some serious money to assist with the fence.

“Probably the most controversial or difficult part was in advocacy and to change the law around the use of poisons for pest control. To change the law was not driven by the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary. It was driven by a policy position that said the number one threat to a native species is pests and you’ve got to give the guys the tools to be able to do it. The penny drop moment for me was being in Fiordland and looking at 2,000-meter-high cliffs, looking at a huge density of stoats and the DoC workers telling me, ‘When people in Wellington tell you that I can put traps up there, I wish they could tell me how I’m meant to do it.’ So, I became a strong convert for the responsible and effective use of pesticides for controlling these pests.”

The Brook Valley Motor Camp

Derek Shaw also talked about ideas that were discussed regarding how the Brook Valley Motor Camp could be included in the Sanctuary project and utilised. “The Motor Camp was discussed as part of the big picture vision for the Sanctuary and the adjacent Brook Reserve, which included the Motor Camp and Council land to the north of the Camp entrance. We saw tremendous opportunities for the Camp to be developed and integrated with the Sanctuary to provide additional quality experiences for visitors, both local and those from elsewhere in New Zealand and overseas. We had received a lot of feedback that it did not present a very attractive entrance to the Sanctuary with such features as the ‘sentry box-like’ building at the entrance and the assorted collection of motorhomes, tents, huts and other structures that were occupied by semi- and permanent residents. It had received very little

capital investment over many years and its use was largely during the summer. We felt that there were great opportunities to develop improved facilities for visitors that could provide benefits to the Camp operation and the Sanctuary. Where else in New Zealand’s two largest islands could you camp or stay in accommodation units adjacent to a pest-free sanctuary and wake up to a dawn chorus of bird song that would get better as the pests were eliminated and lost bird species were reintroduced? We also considered the possibility of one or two remote, off-grid eco-lodges located deep within the Sanctuary that could provide an enhanced experience for up to ten guests. A preliminary design and specifications were prepared and a couple of possible sites were identified.”

Alastair Wiffen recalled his early thoughts and discussions about utilising the campground area. “There was a meeting with an architect from Dunedin about where the bus turning circle was, where the cafe was going to go. We had some visions of grandeur. I remember working with Ian Jack and working out where the gates were. It just went on and on. Where the cafe was going to go, the new caretaker, the Education Centre. That was pretty visionary, and it needed to have that vision but unfortunately, money was always a hassle.”

Derek Shaw also mentioned Ian Jack’s involvement along with another architect, Tim Heath. “It was part of a project we did with Arrow Strategy. They ended up doing us a strategic plan and feasibility study and Ian and Tim put into that because he was very good at doing concept drawings of what the Camp could look like if we did up the units and lifted them out of the 1950s. These documents included a new entrance building that incorporated a visitor centre, shop and café, plus an interesting and informative walk along the upper terrace passed the old reservoir and wildlife attractions to the entrance building and gate through the pest fence. They also included relocating existing cabins to form an eco-village a new manager’s house, staff cabins, additional parking, children’s playground, performance stage, and a new multi-purpose conference centre that could be used by schools, community organisations and corporates. Very exciting ideas that could be developed over time as funds were obtained.”

We were constantly thinking about that. We were having discussions with Council staff, with Pat Dougherty in particular, because it was under his sphere. The whole future of the Camp was up in the air as it had been for quite a few years. That involved discussions with the Tahunanui Beach Holiday Park Board. The Brook and the Maitai camps weren't financially viable on their own whereas Tahunanui was quite financially viable so there were discussions with them about how we might work to try and improve what was on site for visitors coming here.

“There were lots of ideas, including maybe starting again with different units and inviting different builders of different sorts of buildings to come in and trial things. If you were doing straw bale houses, you’d come and build a little unit out of straw bales that locals could come and experience as well as visitors. You might have one that was totally passive solar, another one that was made of mud bricks or whatever different kind of building type.”

Dave Leadbetter also talked about the breadth of the Trust’s vision for the Camp, “It was almost as if you're thinking you're entering Disneyland with some of them. One that I would love to eventually see come to fruition would be to obtain some or all of that camping

ground and make it into a school camp. Have accommodation for the kids and involve them with a week-long or five days involvement with the Sanctuary. That was discussed a lot and we put it to the Council over and over but, of course, one of the big problems was the residents in the campground. If the Council gave the campground to us for a nominal amount so that we could develop it, it would probably involve outing them which was very politically delicate.”

Rachel Reese shared her thoughts on the vision the Trust members were entertaining for the Camp. “I was always really inspired by that vision of the Sanctuary having the opportunity to bring people really close to the Sanctuary and seeing that of part of the ecotourism opportunity for the city. Not just for people coming in from other places but as a mechanism for building connections for tamariki who don't have the opportunity to go into wonderful, wilderness places. Many of them have never been on a farm Connecting to ‘What is this place and why should we care about this place?’ When we're trying to message the value of our environment and why we need to look after it, there's no better experience than being in it.”

Following his appointment as Sanctuary co-ordinator in 2007, Rick Field’s work increasingly involved his role as an educator, leading parties of school children through a range of activities in the Sanctuary. That became the basis of an active education programme connected with local schools through which hundreds of school children visit the Sanctuary every year.

Sharon McGuire, who served for two periods as a trustee, also talked about the ideas of utilising the Camp. “I don't know how many times it's been to Council and I don't believe there's a Reserve Management Plan that's been signed off. It's been some years and you've got this fantastic motor camp at the entry to a sanctuary that you could activate for educational tours. You could make it something pretty special that would differentiate it from the other two Council-owned motor camps so rather than just being a motor camp, it could be an educational conservation centre of excellence. That was always our vision.”

Kate Fulton commented on how tensions between the Sanctuary and the permanent camp residents were exacerbated. “Council, almost overnight, made the decision to close down the campground because it wasn't returning a profit and one of the reasons it was losing money was that it had quite a large permanent community and slowly, they had been leaving. But in closing it down, Council created even more animosity from the permanent residents towards the Sanctuary because, in their minds, there must have been some link. There wasn't a link. It was completely, randomly separate. But I think a lot of the permanent residents felt like somehow the Sanctuary was engineering the closure of the campground to get rid of them.

“It's the gateway to the Sanctuary and if you've invested a whole lot of money in the Sanctuary, you need to make sure your gateway fits and connects. It shouldn't exclude certain groups of people. We have a housing crisis in New Zealand and we have a social justice issue. If you care about the environment then you should also care about people. You should be thinking of ways that your project can support better outcomes for vulnerable communities as well.

“It seemed to me to be this real opportunity that you create a small community village for those who are vulnerable and you have your glamping and your tourists camping and you allow those two groups of people to come together but visually it works much better. I think Tahunanui Campground has done that quite well. It has a thriving community of permanents (campground residents) and the permanents say they feel very safe. They have quite good rules in place to make sure that safety is paramount and that the behaviour there is at a high level. I think you can achieve that.”

Rachel Reese shared similar concerns about the threatened closure of the campground. “They're the vulnerable populations, people that live permanently in campgrounds with the constraints on finding any housing at the moment and the number of people that are living in really dire circumstances. Campgrounds are an integral part of how we live in New Zealand. It’s home for many people.”

Derek Shaw summed up how the Trust thought about a possible relationship between the Sanctuary and the Camp. “It was trying to see that as something that was compatible with the Sanctuary so it'd be of mutual benefit and working together. We did have thoughts about whether we try and establish a board of people who might be prepared to take over the Camp and run it and we could, hopefully, clip the ticket so we saw it as also a way of earning a bit of money for the Sanctuary because we were constantly looking for how we were going to fund this project.

“Ultimately, there were thoughts of even trying to have a place where corporates might come and do retreats and use the forest area as a kind of ‘nature bathing’ place that we could have made some income from. Small-size conferences and events that would have helped with the cash flow and would also get more support for the Sanctuary. We were looking at sites within the Camp for that kind of thing even before we got to the Conservation Education Centre. There was a lot of that big picture, dream stuff. Nice-tohaves that would have been compatible with what we were trying to achieve.”

The Conservation Education Centre

Through negotiations with Nelson City Council about the use of the land and with NMIT and DoC about sharing aspects of the Trainee Ranger programme, several prefabricated classrooms were moved onto the lower eastern hillside to the north of the Motor Camp and opposite the new housing subdivision on Upper Brook Street.

Derek elaborated, “There were a lot of discussions involved but we negotiated a lease with Council for the land and then we spoke to NMIT, which was contracting to DoC to deliver their Trainee Ranger course. NMIT was involved in the Trust as well so we had MoUs with everybody. There was a plan to have a track that would run back through the redwood forest and past the Camp to the Sanctuary so that could be a way of leading people in. And the DoC trainees were a potential volunteer force for working at the Sanctuary while doing the work that they needed to do.

“After the necessary consents were obtained, a sealed driveway, a parking area and a building platform were formed. Three classrooms and a workshop were relocated on to the site by NMIT. The net result was two classrooms for the Trainee Ranger course and the third one was able to be utilised for the Sanctuary’s education progamme which was mostly undertaken by Rick Field in conjunction with his Sanctuary Coordinator role. That classroom was also used for various community meetings and also for Trust meetings.”

Unfortunately, after about 18 months, the land above it on the hillside was discovered to be at risk of slowly slipping and although the risk was considered low, it was closed. Sharon McGuire outlined some of the complexities of that situation. “The frustration was that we were not masters of our own destiny in terms of land ownership and land use. It came down to, ‘If the slip all comes down, whose land and whose responsibility is it?’ I was in NMIT at the time, but it wasn't about NMIT. It was about ‘Can we get agreement with Council and NMIT?’ We'd not got the ability to do the earthworks, and neither should it be our responsibility as the Sanctuary. We were tenants on the land. There'd been a slump or slip and did you want to be the one that's responsible for that coming down on the building? Neither NMIT or the Sanctuary were going to take that risk and Council were not entertaining the idea of any remedial works or any participation in it.”

Rick Field outlined how the Trust investigated the possibility of moving the buildings into the Camp Ground land. “We couldn't afford to move the buildings, even. That was when Bo Stent was employed. That was part of his remit, to sort that out and get the buildings in different places. We got almost to the point where everything was priced out for a building to be shifted to right by the caretaker’s office. We were going to have buildings there and then the whole facility was going to be replicated there. That was pulled at the last minute.”

Derek Shaw outlined the Trust’s thoughts about losing the Conservation Education Centre. “It was really unfortunate that it wasn't put in a place where it could have stayed because it would have been really useful. At the time, we were working with Project Janszoon. We signed an MoU with them and DoC and NMIT. The Museum had, and still has, an education component funded from central government which is for learning experiences outside the classroom (LEOTC) so we worked in with them. Some of the programmes they offered were in the Brook Sanctuary or Rick would go and talk to them at the Museum if a group wasn't able to travel to the Visitor Centre. We did quite a lot of that with lots of kids. That was all to get community support. Start with the kids because a lot of parents come along with their kids to those things and the kids go home full of enthusiasm. It was a great way to build the groundswell of community support for the project.”

The Centre and its buildings were abandoned in 2013 and, following a second geological report on the land, the Trust exited the land lease in 2019 and worked with NMIT to remove the transportable buildings. Since 2021 the land has been planted out as part of a recreational reserve.

The Reserve Management Plan

Kate Fulton talked about issues with the Reserve status of the different parcels of land in and around the Sanctuary. “It turned out that our Reserve status for the campground didn't necessarily allow us to do all the things we were going to do. We had the NMIT classrooms up there, we had the Sanctuary up there and we had the permanents so we needed to change the status. Some of it was Recreation Reserve and some of it was Road Reserve so there was this hodgepodge of different bits that had different status and we needed to redesignate it all as Reserve status.

“I sat on both of those panels and at the last minute it was all going to become Recreation Reserve. The community submitted and said, ‘You've got the cart before the horse. Why are you doing this first? You have to come up with the vision plan first.’ And it turned out they were right. Council had gone about it the wrong way and at the last minute, DoC or someone put in a submission saying, ‘You can't designate it as Recreation Reserve. You've got to designated as Local Purposes (for Recreation).’ So, that's what we designated it as and then it turned out that you couldn't designate it as that.”

Hudson Dodd, general manager of the Sanctuary during that period elaborated. “I think someone had realised at some point but it had been forgotten and it certainly wasn't on my radar, that there's a paper road up the Brook Valley. Well past the dam. About one and a half kilometres past the dam. You can't block public access to a road. Our argument was that the City Council built a dam there but the legal argument was that ‘People can walk around the dam but you're talking about a locking gate.’ So then, the argument was that we were talking about having open days so for at least a day or two a year, people can go in. Anyway, we had to convince the Nelson City Council legal team to tackle going through a road closure process in court and they were a reluctant partner all the way. But we got them to do it and they did it.”

Rachel Reese added further insight into that issue. “When you're a trust trying to engage with a local authority through those complex legal processes, it’s expensive so it's important

that you do have it right. Sitting down and openly working your way through to ‘What is the endgame? How are we going to get there? What are the steps that we need to take?’ I think we lost quite a few years in that process.

“It created uncertainty. With any project where you're trying to work within the whole consultation processes of the Local Government Act, you need to make decisions about funding and it was a significant sum of money that the Council had in its Long Term Plans to put towards the Sanctuary. It wasn't the bulk of the funding, but it was still a significant contribution and when uncertainty arises during those processes the public can get a bit rattled and decide that it’s not the project to support.

“We suddenly had to face a section of the community who were absolutely opposed, vehemently opposed, to the Sanctuary.”

The Nelson Cycle Lift Society Derek discussed another of the Trust’s ideas about including other recreational activities that could be linked to the Sanctuary. “When we went through the Reserve Management Planning process, that was a pretty intricate process with Council. We had a good consultant involved and the Reserve Management Plan had an option for another tourism activity. We were also talking to the Nelson Cycle Lift Society because there was a base there for the gondola when that idea first came along. They put in the Christchurch Bike Park gondola and had done others in Canada. Our entry point could be a joint one so you could go into the Visitor Centre and buy a ticket to go up on the gondola or buy a ticket to go into the Sanctuary.

“It could have gone up to Third House was one option and there was a move to base it around on the other side of the Tantragee Saddle. They weren't going to go right up to the top of that ridge. Two thirds of the way up, I think, and maybe establish a big base. They came up with drawings and there were some places where they thought they could establish a café and they might have luges and other fun activities as well as tracks. There was an opportunity to put a track around the contour which would take it pretty close to Third House. We can obviously put a gate in the fence and open it up on occasions to people who wanted to use the lift to go up and then walk down through the Sanctuary. That's the kind of idea that was bandied around. But then Covid came and the whole thing was put off”

Offices in Nelson City

During the fence fundraising campaign in 2014, through ongoing support from the Bowater Motor Group that included the use of vehicles for operational activities, the Trust set up a central city office in the Bowater Honda showroom on the corner of Hardy and Rutherford streets. The high-profile site assisted significantly with engaging community support and helped to achieve a very good result with the Sponsor a Fence Post campaign. Following a reorganisation of the Bowater Group, the central city office moved to a vacant office space in the Morrison Square complex. Through the ongoing generosity of the Morrison Square management, the office has relocated several times within the complex.

The Trust Board, Management and Governance