Introduction Northern Lights Programme

In Brief

It’s thrilling for the Brigantes Orchestra to be bringing you another programme of wonderful music so soon after the last. This season, our Musical Grand Tour is visiting the hotspots of classical music, and after a barnstorming Saint-Saëns Organ Symphony, this stop delivers something a little more austere, but no less beautiful.

We have arrived in The Nordics (Norway, Finland, Iceland, Sweden and Denmark) and are excited to showcase our soloist, Tim Horton, in Grieg’s beloved, virtuosic piano concerto. Also on the programme, an elegy for string orchestra from Iceland, and Sibelius’s pivotal Third Symphony, his move away from the romantic sound of music in the early 1900s in Europe and towards a national musical voice for Finland.

As before, the Brigantes are an orchestra of the best professional musicians from Sheffield and its environs, and we are extremely fortunate to have a venue as wonderful as Sheffield Cathedral in which to present every programme.

We would like to thank you for coming and hope to see you again in Russia for Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, and Stravinsky’s magical Firebird on 23 January 2026 in Sheffield Cathedral.

More details of the coming season can be found on page three of this brochure.

THE BRIGANTES ORCHESTRA

Bradley Creswick (leader)

Tim Horton (pianist)

Quentin Clare (conductor)

JÓN LEIFS (1899 to 1968)

Hinsta kveðja (Elegy) - in memoriam 30.09.61 (1961)

I Adagio, ma non troppo

EDVARD GRIEG (1843 to 1907)

Piano Concerto in a, Op. 16 (1868)

I Allegro molto moderato

II Adagio

III Allegro moderato molto e marcato - Poco animatoPoco più tranquillo - Tempo primo - Quasi PrestoAndante maestoso

INTERVAL c.8.15pm for 20 minutes

JEAN SIBELIUS (1865 to 1957)

Symphony No. 3 in C (1907)

I Allegro moderato

II Andantino con moto, quasi allegretto

III Moderato - Allegro (ma non tanto)

FINISH c.9.10pm

Brigantes Orchestra Season 2025/26 Highlights:

FRANCE | L’ARLÉSIENNE

James Mitchell - Organ

Friday, 17 October 2025, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

Georges Bizet L'Arlésienne (extracts)

Maurice Ravel Boléro

Camille Saint-Saëns Symphony No. 3, Organ

GERMANY | REFORMATION

Saturday, 21 March 2026, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

JS Bach / Joachim Raff Chaconne in d

Richard Wagner Prelude and Music from Parsifal

JS Bach / Anton Webern Ricercare

Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 5, Reformation

THE NORDICS | NORTHERN LIGHTS

Tim Horton - Piano

Saturday, 29 November 2025, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

Jón Leifs Hinsta kveðja (Elegy for Strings)

Edvard Grieg Piano Concerto in a Jean Sibelius Symphony No. 3 in C

BRITAIN | PROMS FESTIVAL

Saturday, 16 May 2026, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

Gustav Holst The Planets

a second half including all the traditions of The Last Night of the Proms:

Henry Wood Fantasia on British Sea Songs

Thomas Arne Rule Britannia

Edward Elgar Pomp and Circumstance No. 1

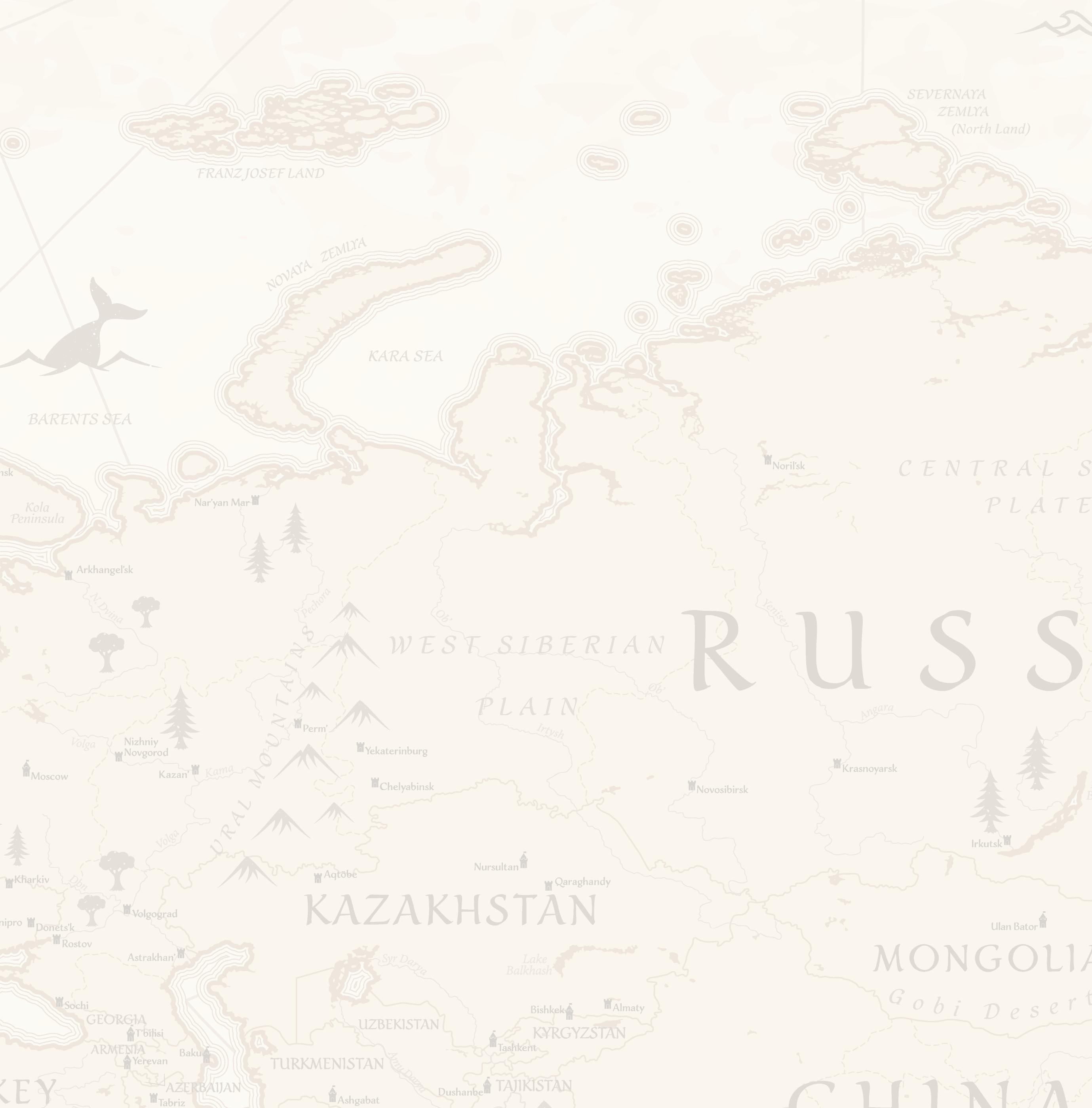

FROM RUSSIA

Wibe-Pier Cnossen - Baritone

Friday, 23, January 2026, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet

Modest Mussorgsky Songs and Dances of Death

Igor Stravinsky The Firebird Suite (1945)

USA | INDEPENDENCE DAY

Saturday, 20 June 2026, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

including

Leonard Bernstein Overture, Candide

George Gershwin Concerto in F

George Gershwin Overture, Girl Crazy

Aaron Copland Rodeo

Jón Leifs (1899 to 1968)

Few composers are as intimately bound to the landscape and spirit of their homeland as Jón Leifs is to Iceland. A musical pioneer, Leifs almost single-handedly forged an orchestral language for a nation that, until the early twentieth century, had little written musical tradition of its own. Educated in Leipzig, where he studied conducting and composition at the Conservatory, he was exposed to the rigours of German late-Romantic craft - Brahms, Reger and Strauss - but his imagination was always pulled northwards, towards the sagas, volcanic terrain and ancient modal songs of Iceland.

Leifs’s music is for the most part elemental. He often described his works not as expressions of personal emotion but as “natural phenomena,” shaped by the same geological forces that built the island itself. His Geysir (1961), Hekla (1961) and Dettifoss (1964) are vast tone paintings of eruptions, waterfalls and tectonic violence, demanding enormous orchestras and unorthodox percussion. Yet within this monumental sound world, works like Hinsta kveðja and the late Consolation, lies an austere lyricism: music that eschews Central European romantic sentiment in favour of raw, primeval energy and ancient melodic contour.

The Elegy, composed in 1961, stands apart for its stark intimacy. It was written in response to the tragic death of Leifs’s daughter, Líf, who drowned while swimming off

the coast of Italy. The work distils Leifs’s grief into a few minutes of haunting simplicity. Scored for strings, its textures are spare and unadorned, built from modal fragments that seem to hover between lament and ritual. The effect is both intensely private and archetypally Nordic: grief rendered not in confession but in the solemn language of nature and myth.

Leifs occupied a difficult position in Icelandic cultural life. His uncompromising individuality and insistence on a distinct Icelandic idiom made him both revered and isolated. During his years in Germany he became estranged from his Jewish wife under Nazi pressure, an episode that left deep personal scars. Returning to Iceland after the war, he found himself regarded as a maverick: too severe for audiences steeped in imported romanticism, too visionary to be ignored. Today, however, his music is recognised as foundational, and the starting point of Iceland’s modern musical identity, paving the way for later generations of composers such as Hafliði Hallgrímsson, Anna Þorvaldsdóttir and Daníel Bjarnason.

In Elegy, Leifs’s characteristic austerity becomes a study in control. There is no extrovert display of emotion, only a deliberate paring back to the essentials of line and harmony. Its restraint and economy of means reveal the composer’s command of structure and sonority, and show how deeply his art was rooted in the discipline of form rather than sentiment. The intent, however, is clear.

ADAGIO, MA NON TROPPO

Edvard Grieg (1843 to 1907)

Piano Concerto in a

(1868)

Few works in the Romantic repertoire announce themselves with such instant authority as Edvard Grieg’s Piano Concerto. From the opening timpani roll and flourish of cascading piano chords, it declares both its lineage and its individuality: a nod to the model of Schumann’s concerto in the same key, yet unmistakably coloured by a Nordic sensibility all its own.

Grieg composed the concerto at the age of twenty-four while living in Denmark, and although he, like Jón Leifs, had been trained in Leipzig and schooled in the Austro-German symphonic tradition, he was already searching for a musical identity that would speak in a distinctly Norwegian accent. Folk melody, rhythm and dance permeate his writing - sometimes through direct quotation, but usually through assimilation. The themes of the concerto are inflected with modal turns and rhythmic asymmetries that evoke the halling and springar of Norwegian fiddle music.

The first movement, cast in classical sonata form, opens with that famous piano declamation before unfolding in sweeping Romantic paragraphs. Yet within the grandeur, Grieg introduces subtle dislocations of rhythm and phrasing that soften the Germanic architecture into something more flexible and spontaneous.

The slow movement offers a contrast of inward calm. Its inflection, gently rocking onto the second beat of three, and lyrical woodwind lines create a chamber-like intimacy that harks back to the Schumann model but with anticipation of the transparency of later Scandinavian music. The piano writing is restrained, the emphasis on dialogue rather than display.

The finale is cast as a free rondo, animated by dance rhythms and bright, folk-like gestures. Its principal theme has the unmistakable swing of the Norwegian halling, and the movement’s alternation between athletic drive and lyrical repose gives it theatrical contrast. The return of the lyrical second theme in a radiant A major transformation near the end provides one of the concerto’s most satisfying moments.

The concerto was premiered in Copenhagen in 1869 with Edmund Neupert as soloist and was immediately acclaimed. Liszt, who saw the score in manuscript, praised its invention and national character, and the work quickly established itself in concert halls across Europe. For Grieg, it remained his most ambitious large-scale composition and a touchstone for the national style he continued to develop in his later Lyric Pieces and suites of music from Peer Gynt

RONDO: a structure used by many composers, often as the final movement of a sonata, symphony or concerto. The structure is essentially A-B-A-C-A with slight variation of the A-theme on each return. In pop music, the chorus can be seen as the A-theme, much the same as the line “Old MacDonald had a farm, E-I-E-I-O,” in the children’s nursery rhyme. Mozart’s Rondo alla turca or the last movement from his Eine kleine Nachtmusik are other prime examples of Rondo form.

Edvard Grieg

Jean Sibelius (1865 to 1957)

Symphony No. 3 in C (1907)

ALLEGRO MODERATO

ANDANTINO CON MOTO, QUASI ALLEGRETTO MODERATO - ALLEGRO (MA NON TANTO)

By the time Jean Sibelius completed his Third Symphony in 1907, he was already Finland’s foremost composer and, for many of his countrymen, a symbol of national aspiration. His first two symphonies had established that reputation with their expansive romantic sweep and unmistakably Nordic colouring. The Third, however, took a strikingly different path. Listeners expecting another brooding, monumental landscape found instead a taut, clear-edged work of classical proportions: concise, lucid and resolutely unsentimental. In a period when composers across Europe were stretching symphonic form to its limits, Sibelius moved in the opposite direction: towards concentration, economy and abstraction.

Sibelius had received a thorough musical education that bridged provincial beginnings and continental sophistication. He first studied violin and composition at the Helsinki Music Institute (now the Sibelius Academy), where his teachers included Martin Wegelius, who introduced him to the German classical tradition, and the composer Ferruccio Busoni, who became a close friend and mentor. In 1889 he travelled to Berlin, studying with Albert Becker and immersing himself in the city’s orchestral life, and later to Vienna, where he took lessons with Karl Goldmark and Robert Fuchs. These experiences exposed him to the full breadth of European Romanticism - Brahms, Bruckner, and Wagner - while sharpening his technical command

of orchestration and form. Yet even amid this cosmopolitan training, Sibelius’s imagination remained tied to the landscapes and language of Finland, and it was the fusion of those two worlds, continental discipline and Nordic character, that shaped his mature style.

The change of musical direction in 1907 reflected both artistic conviction and circumstance. At the turn of the century Sibelius was emerging from a turbulent decade: personal debt, family responsibilities, and bouts of ill health shadowed a career that had brought him sudden fame but little stability. The Third Symphony coincided with a decisive turn inward; a refining of purpose rather than a withdrawal. Its sound world is lean, its orchestration reduced to classical forces, and its expressive power arises not from overt rhetoric but from the precision of its construction.

The opening movement begins with a rhythmic pulse that feels almost physical: cellos and basses introduce a brisk, muscular motif that sets the symphony in motion. Over this firm foundation the woodwinds and violins trace athletic, diatonic lines - music that seems carved from the same sturdy material as Finland’s granite coastline. The energy is propulsive but never volatile; Sibelius builds his argument through subtle shifts of texture and harmony rather than traditional symphonic confrontation. There is no grand slow introduction, no tragic conflict to resolve. Instead, he creates tension through condensation - by allowing ideas to evolve organically, like growth rings in a tree trunk.

The second movement offers a deceptive sense of repose. It unfolds as a long, winding song for strings, punctuated by brief, questioning gestures from winds and brass, and eventually by the divided cellos who capture the sound of the traditional Finnish male-voice choir. Beneath its calm surface, however, lies a quiet restlessness: the main melody never quite settles, and the harmonies glide through unexpected turns, blurring the distinction between major and minor. The atmosphere is distinctly cool and light, with spacious phrasing, and a sense of landscape glimpsed through mist rather than narrated directly.

The finale is where the symphony’s structural ingenuity comes fully into view. It begins almost hesitantly, with fragments that seem unrelated: a sprightly dance-like theme, a contrasting hymn-like idea, brief transitions that appear provisional. Yet, as the movement unfolds, Sibelius gradually fuses this material into a single, unstoppable process. What begins as apparent contrast becomes a kind of evolution: thematic cells recombining, expanding, coalescing into a single forward drive. By the end, the hymn theme emerges transformed into a broad, confident peroration: not triumphal in the Romantic sense, but achieved through logic and cumulative momentum. This final synthesis was one of Sibelius’s great formal discoveries, and it points directly to the symphonic techniques of his later works, especially of the Fifth Symphony.

At its premiere in Helsinki under the composer’s direction in September 1907, the Third Symphony perplexed many who had admired the sweeping lyricism of the First and Second. One critic complained that it was “cold and without poetry,” missing the grandeur they expected from Sibelius. Yet others sensed its radical integrity. The composer himself described it as “a crystallisation - a step forward in the

direction of greater profundity.” That sense of distillation became a hallmark of his mature style: music stripped to essentials, its expressive power derived from internal process rather than surface gesture.

In the broader European context, the Third Symphony stands as a quiet act of resistance. In an age dominated by Mahler’s vast emotional canvases and Strauss’s opulent tone poems, Sibelius turned away from expansion towards concentration. His modernism was not the dissonant rupture of the avant-garde but a rethinking of classical proportion, a renewal of the symphony from within. The clarity of texture, the motivic discipline, and the seamless sense of growth anticipate the organic structural thinking that would later fascinate composers like Nielsen and Tippett.

For Finnish audiences, the work carried additional resonance. Its restraint and inner strength seemed to mirror the national temperament - stoic, resilient, and independent - during a period when Finland was asserting its identity under Russian rule. Yet Sibelius was wary of overt nationalism; what he achieved in the Third Symphony was something broader: the demonstration that a composer from the northern edge of Europe could engage the symphonic tradition on his own terms, with equal authority and without imitation.

Today, the Symphony No. 3 is often regarded as the turning point of Sibelius’s career: the moment he left behind the outward drama of late Romanticism for the compressed, elemental logic of his later masterpieces. Its surface modesty conceals a profound re-imagination of what a symphony could be. Every note seems necessary, every gesture economical, and the sense of momentum from first bar to last is unbroken.

RECOMMENDED LISTENING

Listen again to: Osmo Vänskä conducting the Lahti Symphony Orchestra playing Sibelius Complete Symphonies

Brigantes Beginners Nordic Classical Music

BRIGANTES BEGINNERS

by Anthony Hart

If you don’t know much about classical music, coming to a concert can be intimidating. If that’s you, you’re not alone. This section, along with the timeline in the programme, gives essential information about the pieces, composers, and their historical and social context, and will help you understand what’s going on!

“...music begins where language ends.” Jean Sibelius

“Music begins where the possiblities of language end.” Jean Sibelius.

When people think of classical music and its composers, they may first look towards Germany, Austria, Italy or France. However, the Nordic countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Iceland) have a distinct voice too, shaped not by empire or aristocracy, but by the weather and landscape, by distance and introspection, and by national identity. The music is not the voice of the cities but of silence.

The Nordic countries share deep cultural ties, but very different histories. Denmark and Sweden once ruled empires that fought each other across the Baltic. Norway spent four centuries under Danish and then Swedish control. Finland was part of the Russian Empire for a hundred years before gaining independence in 1917. Iceland was settled by Norse seafarers, only becoming fully independent from Denmark in 1944. The Nordic region’s geography bred both isolation and resilience. Its people were used to enduring long, dark winters and resisting their powerful neighbours. As a result, they learned to define themselves and represent their resilience through language, literature, and music. The latter became a particularly subtle weapon in a struggle for identity. Sibelius’s Finlandia, composed in 1899 during a period of Russian censorship, became a covert protest, and was played to scenes of Finnish history and folklore.

In the classical period, the north was largely an importer of musical style. Composers like Joseph Martin Kraus in

Sweden (1756 – 1792), the so-called “Swedish Mozart,” or Christoph Weyse in Denmark (1774 – 1842) wrote elegant symphonies that would not have sounded out of place in the German concert hall. The notion that music could sound of a place, expressing the landscape, people, and myths, only took hold in the nineteenth century when the Romantic era started. For a period, music, literature, and poetry became more emotionally expressive, using broad brushstrokes rather than intricate detail, and often tied to the landscape or weather. At the same time, a sense of national pride and identity came to the fore.

It was in Norway that this awakening found its clearest voice. Edvard Grieg (1843 to 1907), a fiercely determined man with a mane of hair that looked permanently windblown, gave his country its musical identity. Having studied in Leipzig, he could easily have stayed within the polite boundaries of German romanticism, but he returned home, determined to make Norway sing in its own voice. Folk melodies, alongside the sound of mountain air and fjords, were found in almost everything he wrote, such as the miniature Lyric Pieces, Peer Gynt, and his Piano Concerto. That concerto, from its famous opening crash of piano against orchestra, feels like a declaration of independence. It is both confident and yearning, rooted in the Romantic tradition and unmistakably Norwegian. It has become one of the best-loved concertos, though for some listeners its reputation has been slightly compromised by Morecambe and Wise, who performed “all the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order.” For those who grew up with that

Jóhannes Sveinsson KjarvalLava at Bessastadir (1947)

sketch, it is almost impossible to hear the concerto without a smile, which is a curious fate for such a majestic, heartfelt piece. Perhaps that says something about Grieg’s music: it has so completely entered the popular imagination that it can even survive a skit featuring “Andrew Preview” and Eric Morecambe.

If Grieg gave Norway its melody, then Sibelius gave Finland its architecture. Born when his country was still a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire, Sibelius transformed the struggle for national identity into music of profound dignity. He was fascinated by the Kalevala, Finland’s vast epic of gods, warriors, and swans, and he made myth a metaphor for survival. His Symphony No. 3 in C marks the point where the grand romantic gestures of his earlier works fall away and something leaner, purer, more elemental takes their place. The music seems to carve itself from ice, chiselled, and clear. Gone are the sweeping Wagnerian harmonies; in their place are taut rhythms, austere melodies, and an almost classical balance. It is a symphony that looks both backward and forward; backward to Mozart’s clarity, forward to modernism’s restraint. The ending, where two themes finally merge into one, feels like a metaphor for Finland itself, finding its footing between east and west, between oppression and independence.

Sibelius’s later silence is almost as famous as his music. After his Seventh Symphony in 1924, he published nothing more, although he lived another thirty years. It was said he burned sketches for an Eighth Symphony one autumn night in despair. It is possible that the man who said music began where language ended had said everything he wished to. As the Norwegian writer, Knut Hamsun said, “In the north, silence is not emptiness. It is expectation.”

Across the water in Denmark, Carl Nielsen (1865 – 1931) was fighting his own battles. Like Sibelius, he refused to believe that the symphony had outlived its purpose, even as Europe slid into the chaos of the First World War and the rules of music were being abandoned by 20th century composers. His music is muscular, bracing,

sometimes argumentative, like a man wrestling ideas into shape. His six symphonies are a journey from youthful confidence to weary self-knowledge, the later ones darker and more elusive.

The Icelandic story came later. Jón Leifs (1899 – 1968) grew up on an island without an orchestra. He studied in Leipzig but returned, determined to write music that sounded like Iceland itself. He created music that roared like volcanoes and cracked like glaciers, full of primitive energy and moral conviction. Yet among his tempestuous works lies something astonishingly still: his Elegy (Hinsta kveðja) was written after the death of his daughter and contains a lifetime of grief. It feels like the act of mourning itself: unadorned, dignified, and devastating. It is hard to think of another piece that captures the Nordic temperament so completely, with emotion held tight, the landscape vast, and the silence eloquent.

The common thread through all this music is not a shared style but a shared temperament. The result is a music that values simplicity over display, suggestion over statement. But, for all its austerity, Nordic music is not cold. There is modest and sincere warmth beneath the frost. Perhaps that is why the Nordic sound has resonated so strongly with later generations. Sibelius’s organic way of building a symphony from tiny cells influenced everyone from Vaughan Williams to John Adams. Grieg’s lyrical harmonies found their way into Debussy, Ravel, and countless film scores. And Jón Leifs, largely unknown in his lifetime, prefigured the elemental landscapes of later Icelandic composers, even the atmospheric pop of Björk.

So, what is the legacy of the Nordic composers? If the French offered colour and heart, Germans and Austrians brought structure and intellect, then the north reflected a stillness, honesty, and humility. Nordic composers taught Europe that beauty can whisper as well as sing and that strength can reside in simplicity. As a Finnish proverb says, “We are not accustomed to shouting our joy from the rooftops. We whisper it - but it is joy nonetheless.”

RECOMMENDED LISTENING

Listen to Peter Donohoe playing the Grieg Lyric Pieces

CLASSICAL: within the whole of classical music are agreed eras (see our timeline). The Classical Era, with origins roughly in the 1720s and running until around the 1830s, can be compared to the idea of classical architecture with its features of symmetry and proportion.

Neo-Classicism in the early 20th century sought the ideals of the Classical Era. To say a piece of music has ‘classical features’ is to define it as unfussy, well-proportioned and symmetrically balanced.

Tim Horton Pianist

Tim Horton is one of the UK’s leading pianists, equally at home in solo and chamber repertoire. He is a founder member of both the Leonore Piano Trio and Ensemble 360 and has been a regular guest pianist with the Nash Ensemble . He was invited to make his solo debut at Wigmore Hall in 2016 and presents his Chopin Cycle there over the 2024-2025 and 2025-2026 seasons. Following two performances of Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and Sir Simon Rattle at Symphony Hall, Birmingham, Tim was asked to give concerts with the RLPO , Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra , Birmingham Contemporary Music Group and Trondheim Symphony Orchestra

With the Leonore Piano Trio , Tim has given concerts throughout the UK, Scandinavia, New Zealand and Europe. They have performed a cycle of the complete Beethoven Trios at King’s Place, London and have repeated the cycle at various venues since then. They have produced seven discs for Hyperion , including the complete Parry Trios and the Piano Quartet with Rachel Roberts.

Tim has performed with many of the world’s leading chamber musicians including the Elias, Vertavo and Talich Quartets, Paul Lewis, Imogen Cooper, Robin Ireland (with whom he has released two discs), Peter Cropper, Adrian Brendel and Rachel Roberts.

Quentin Clare Conductor

The British conductor Quentin Clare made his professional debut at the age of just 25 when he conducted the Hallé Orchestra in the Bridgewater Hall, Manchester. Since then, he has worked with many orchestras in the UK, including the BBC Philharmonic , Royal Northern Sinfonia , Orchestra of Opera North and Ensemble 11 , as well as having performances broadcast on British and European television and radio.

Quentin’s international career has seen him conduct orchestras in Europe, such as the Danish National Symphony , Dutch Radio Philharmonic , Symphony Orchestra of Nancy , and the Nürnberg, Würzburg and Bochum Symphony Orchestras. He is equally experienced in the opera house, working in France, The Netherlands and Germany on productions including Stravinsky's The Rake’s Progress and the French premiere of Robert Carsen’s acclaimed production of Richard III by Giorgio Battistelli.

Much in demand as an inspirational conductor of young musicians, he has conducted the orchestras at the conservatories in Ghent, Birmingham, Den Haag and Weimar.

He has been guest conductor with Young Sinfonia in Newcastle and is music director of The New Mannheim Orchestra and The Brigantes

Horton by Andrei Luca

Brigantes Orchestra On Stage

FLUTE / PICCOLO

Laura Jellicoe

Jennifer Dyson

OBOE

Manon Lewis

Bethan Roberts

CLARINET

Helen Blamey

Matthew Wilsher

BASSOON

Alex Kane

Alice Gwynne

HORN

Simon Twigge

Janus Wadsworth

Kelly Haines

Abbie Young

TRUMPET

Seb Williman

Gordon Truman

TROMBONE

Christopher Gomersall

Nicholas Hudson

Garrath Beckwith

TIMPANI

Peter Matthews

FIRST VIOLIN

Bradley Creswick

Emily Chaplais

Rachael England

Charley Beresford

Anne Whittaker

Josh Simms

Helen Tonge

Clare Pitchford

Sarah Razlin

Emily Groom

SECOND VIOLIN

Tamaki Hagashi

Amanda Gillham

Holly-Rayne Bennett

Rosie Nicholson

Joanne Atherton

Michael Walton

Ailsa Burns

Hannah Thompson-

Smith

VIOLA

Barnaby Adams

Ben Kearsley

John Hird

Jonathan Kightley

Elizabeth Lundie

Paula Bowes

Ann-Marie Shaw

CELLO

Gemma Wareham

Clara Pascall

Tim Smedley

Adrianne Wininsky

John Parsons

Jonny Ingall

Greg Morton

DOUBLE BASS

Pietro Lusvardi

Richard Waldock

Matthew Clarkson

Matt Barks

Sheffeld’s Pro Orchestra About Us

The Brigantes (Bri-gan-tez) were a collection of Celtic tribes ruled by Queen Cartimandua in 1st-Century Northern England who populated what is now Yorkshire. Literally meaning “high ones”, Brigantes could refer to nobility or to highlanders living on the Pennines or in Hillforts. The Brigantes were cultured, enjoying theatre and music.

The name Brigantes was chosen for a new orchestra because it encapsulates location, culture and unity: the idea that an ensemble is, roughly speaking, a tribe of musicians.

The Brigantes Orchestra was formed in Sheffield in 2019 in response to the observation that Sheffield did not have a professional symphony orchestra of its own, despite a wealth of local talent. The Brigantes aim to bring highquality orchestral music to the city and surrounding areas, as well as to engage new audiences, those who would not otherwise visit the classical concert hall. This includes a growing population of young musicians in Sheffield’s schools.

All photography with thanks to Eduardus Lee

SOCIAL MEDIA

Instagram: @brigantesmusic

Twitter / X: @thebrigantes

Facebook: facebook.com/brigantesmusic

WITH THANKS

Brigantes Music is a registered charity and as such benefits from the generous time our supporters give for jobs like flyering, marketing and front-of-house. Thank you to: Anthony Hart, Jonny Ingall, David Watkin-Holmes, and to all who have helped today scanning your tickets or making sure you have this programme.

BECOME A MEMBER

MADE POSSIBLE BY...

The Brigantes Orchestra would like to thank NEURONATAL LTD

CREDITS

Programme notes: Anthony Hart & Quentin Clare Photography: Eduardus Lee

We are pleased to announce new ways you can support the work of The Brigantes Orchestra with a membership programme offering lots of benefits, special offers and exclusive opportunities. These are tiered and, depending on your donation, can include free season tickets, branded Brigantes merchandise (like the polo shirts some of our front-of-house team are wearing, or a framed poster), reductions on tickets for your friends and family, a printed acknowledgement of your support in each programme booklet of the season, free interval drinks at our concerts, opportunities to sit in the orchestra during rehearsals and see the pieces put together, chances to meet the players, invitations to VIP receptions...

Further details are available at contact@thebrigantes.uk.

BECOME A VOLUNTEER

We are looking for volunteers who would like to be involved in the promotion and development of the orchestra so that it can continue to realise its charitable aims. Those willing to distribute flyers in suitable places in their neighbourhood, add us to local newsletters and social media groups, help with fundraising, or take on some roles in front-of-house should email us at contact@thebrigantes.uk.

THE BRIGANTES ORCHESTRA

Sheffield, S11

Brigantes Music is a Registered Charity: 1187752

© 2025 The Brigantes Orchestra

Tim Horton’s piano kindly loaned to us by SHACKLEFORD PIANOS