Introduction New Season Programme In Brief

Welcome back!

We are thrilled to present the first concert of our new season, A Musical Grand Tour!

Over the coming nine months, the Brigantes Orchestra will drop in on six classical music hotspots including the Nordics, Russia, Germany & Austria, Britain and America whilst performing with brilliant soloists like Tim Horton and Wiebe-Pier Cnossen. This year will see some big scores on our music stands including tonight’s Organ Symphony, Wagner’s Parsifal, Holst’s The Planets and the Gershwin Piano Concerto. There is still time to book a round-the-world trip in the shape of our season ticket which offers 20% off - we’ll upgrade you from tonight’s purchase for an extra £78 for a standard and £48 for a disabled or unemployed ticket.

As before, the Brigantes are an orchestra of the best professional musicians from Sheffield and its environs, and we are extremely fortunate to have venues as beautiful as Sheffield Cathedral in which to present every programme.

We would like to thank you for coming and hope to see you again in the Nordics for Grieg and Sibelius on Saturday, 29 November in Sheffield Cathedral.

More details of the coming season can be found on page three of this brochure.

THE BRIGANTES ORCHESTRA

David Milsom (leader)

James Mitchell (organist)

Quentin Clare (conductor)

GEORGES BIZET (1838 to 1875)

Music from L’Arlésienne (1872)

I Prélude

II Adagietto

III Carillon

IV Pastorale

V Farandole

MAURICE RAVEL (1875 to 1937)

Boléro (1928)

I Tempo di Boléro: Moderato assai

INTERVAL c.8.10pm for 20 minutes

CAMILLE SAINT-SAENS (1835 to 1921)

Symphony No. 3 in c, Organ Symphony (1886)

I Adagio - Allegro moderato - Poco adagio

II Allegro moderato - Presto -

Maestoso - Allegro - Piu allegro

FINISH c.9.10pm

Brigantes Orchestra Season 2025/26 Highlights:

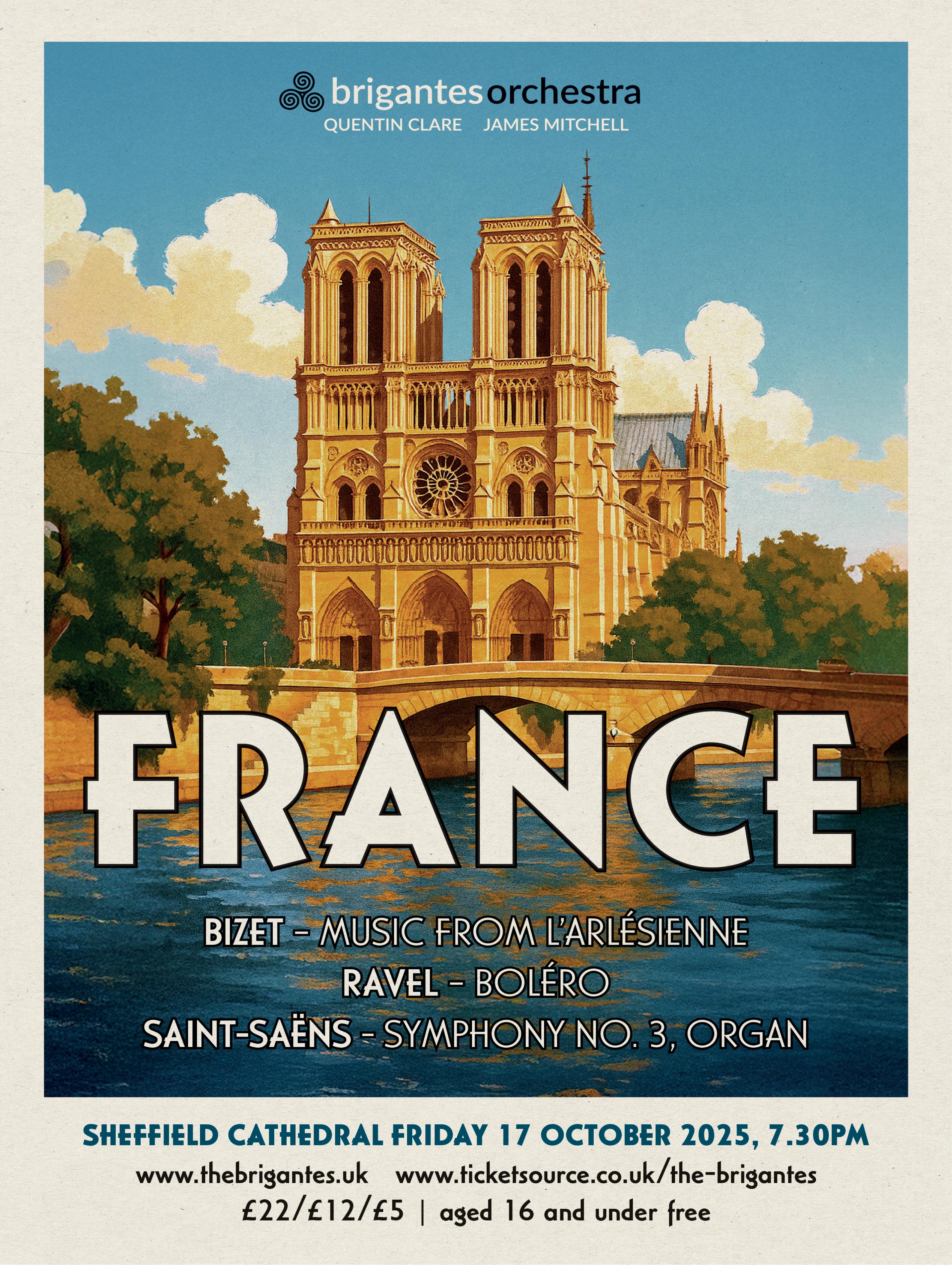

FRANCE | L’ARLÉSIENNE

James Mitchell - Organ

Friday, 17 October 2025, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

Georges Bizet L'Arlésienne (extracts)

Maurice Ravel Boléro

Camille Saint-Saëns Symphony No. 3, Organ

GERMANY | REFORMATION

Saturday, 21 March 2026, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

JS Bach / Joachim Raff Chaconne in d

Richard Wagner Prelude and Music from Parsifal

JS Bach / Anton Webern Ricercare

Felix Mendelssohn Symphony No. 5, Reformation

The NORDICS | NORTHERN LIGHTS

Tim Horton - Piano

Saturday, 29 November 2025, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

Jón Leifs Hinsta kvedja (Elegy for Strings)

Edvard Grieg Piano Concerto in a Jean Sibelius Symphony No. 3 in C

BRITAIN | PROMS FESTIVAL

Saturday, 16 May 2026, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

Gustav Holst The Planets

a second half including all the traditions of The Last Night of the Proms:

Henry Wood Fantasia on British Sea Songs

Thomas Arne Rule Britannia

Edward Elgar Pomp and Circumstance No. 1

FROM RUSSIA

Wiebe-Pier Cnossen - Baritone

Friday, 23 January 2026, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet

Modest Mussorgsky Songs and Dances of Death

Igor Stravinsky The Firebird Suite (1945)

USA | INDEPENDENCE DAY

Saturday, 20 June 2026, 7.30pm

Sheffield Cathedral

including

Leonard Bernstein Overture, Candide

George Gershwin Concerto in F

George Gershwin Overture, Girl Crazy

Aaron Copland Rodeo

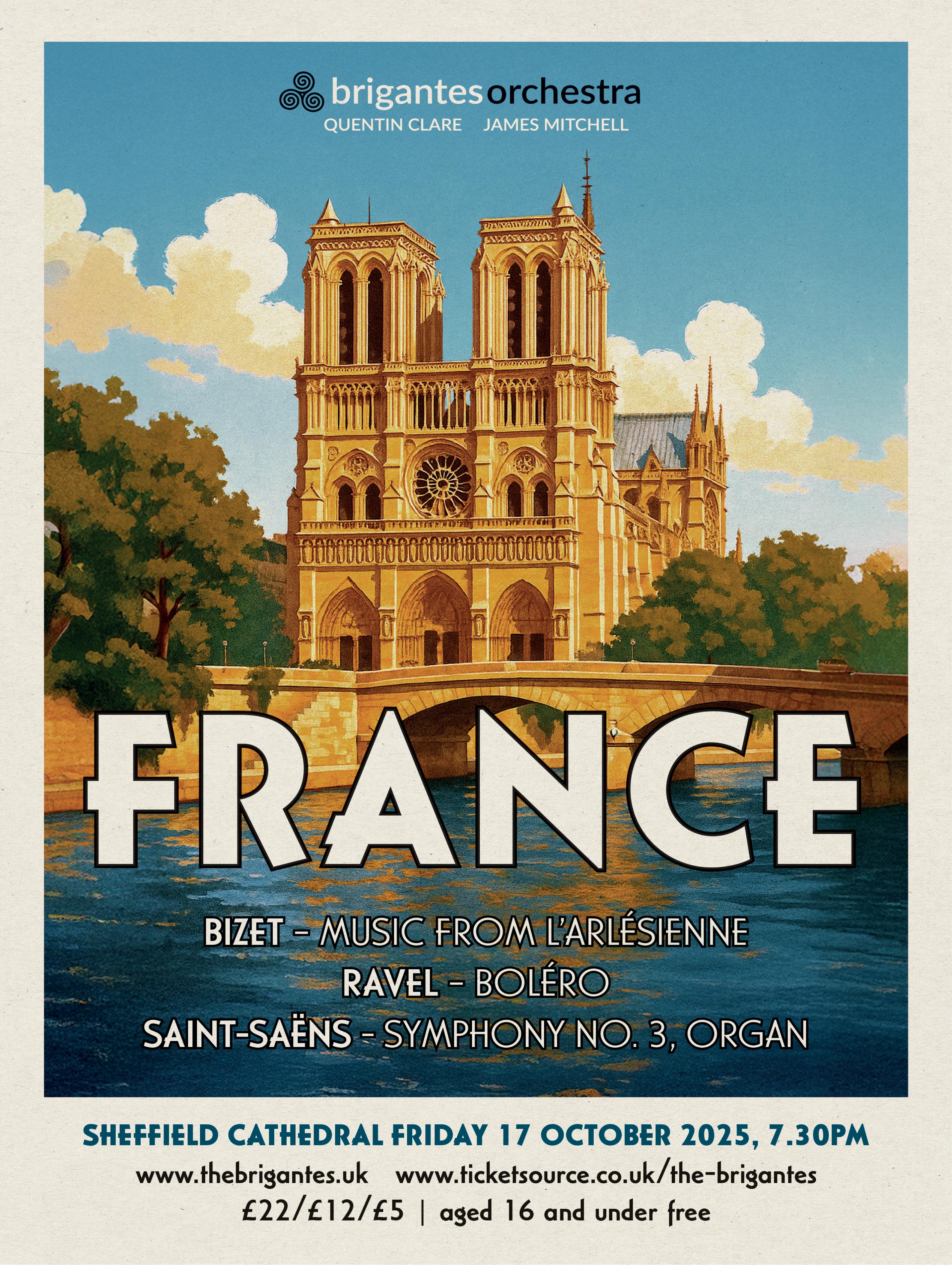

Georges Bizet’s life and career were cut cruelly short. Born in Paris in 1838 into a family of musicians, he displayed prodigious gifts from an early age. At nine he entered the Paris Conservatoire where he studied piano, organ, and composition under some of the most respected teachers of the day, including Charles Gounod. His dazzling technique at the keyboard and his flair for melody quickly set him apart; by his late teens he had already won the prestigious Prix de Rome, which allowed him to spend three formative years in Italy. There he absorbed not only Italian operatic style but also developed an ear for folk colour and atmosphere that would leave a lasting impression on his music.

Despite these early triumphs, Bizet’s professional career in Paris was one of constant frustration. Opera was his chosen field, and he wrote tirelessly for the stage, but the French musical establishment was slow to recognise his genius and as many as thirty operas were begun, abandoned unfinished, or remained unperformed. So many of his works were poorly received that he was left to rely on teaching and piano reduction work to make a living. Only after his premature death at the age of 36 from a heart attack did his reputation truly begin to grow,

fuelled above all by the posthumous success of Carmen (1875). Today, that opera is one of the most performed in the world, and Bizet is celebrated as a master melodist with a gift for drama and colour equal to any of his contemporaries.

Alongside Carmen, the other work that has kept Bizet’s name alive in the concert hall is his incidental music for Alphonse Daudet’s play L’Arlésienne (“The Girl from Arles”), written in 1872. The play tells the tragic story of a young man, Frédéri, whose obsession with a faithless woman from Arles drives him to madness and death. The play itself was not a success - it closed after fewer than 20 performances at the Théâtre du Vaudeville in Parisbut Bizet’s score made an immediate impact. Recognising the quality of the music, he quickly drew together four of its movements into an orchestral suite, which enjoyed great popularity. After Bizet’s death, his friend Ernest Guiraud arranged a second suite from the surviving numbers, ensuring that the incidental music, not the play, became the enduring legacy.

Bizet was at pains to capture the atmosphere of Provence, where the drama is set, and he achieved this by weaving traditional melodies into his own music, and by vivid and brilliant orchestration anticipating that by later composers such as Ravel and Debussy. Most striking is the March of the Kings (heard at the opening of the Prélude), a folk tune that he found in a collection of Provençal carols.

Maurice Ravel (1875 to 1937)

Boléro (1928)

1

DI BOLÉRO: MODERATO ASSAI

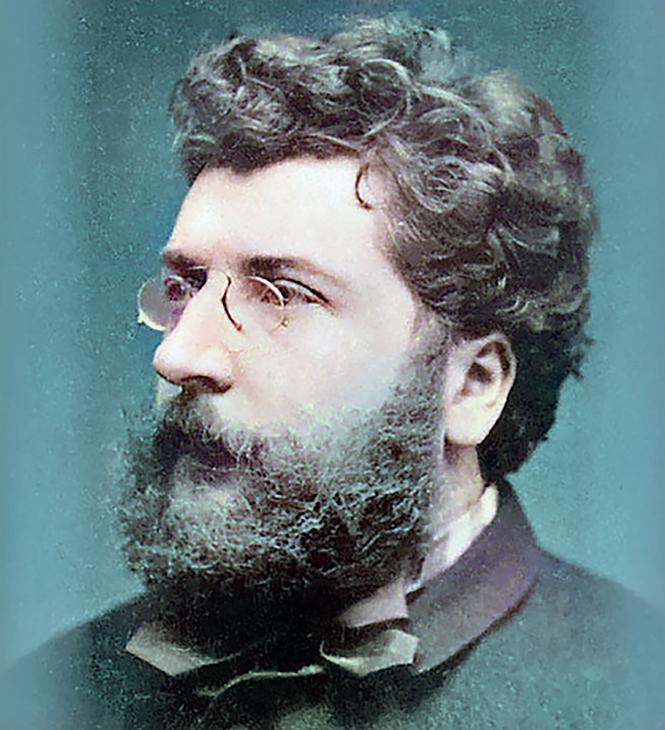

Few pieces in the orchestral repertoire are as instantly recognisable as Ravel’s Boléro. Written in 1928, it is at once hypnotic, audacious, and astonishingly simple in design: a single snaking melody, repeated again and again over an unchanging rhythm, gradually clothed in ever more sumptuous orchestral colours until it culminates in an overwhelming blaze of sound.

Maurice Ravel was one of the most refined craftsmen of the early twentieth century: a French composer admired for his fastidious ear, his mastery of orchestration, and his ability to combine clarity of form with modern sonority. Born in the Basque town of Ciboure, Ravel grew up amidst the musical influences of both France and Spain - a heritage that frequently colours his work. He trained at the Paris Conservatoire and, though he never won the coveted Prix de Rome despite several attempts, by the time of the First World War had established himself as one of the most original voices of his generation. His output is not vast, but it is extraordinarily polished: from the delicate impressionism of Jeux d’eau and Miroirs for piano, to the glittering orchestrations of Daphnis et Chloé and La Valse, and finally the stark originality of Boléro.

The Boléro was composed at the request of the Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein, who wanted a new ballet from Ravel. He admitted to friends that his intention was quite experimental: to write “a piece consisting wholly of

orchestral tissue without music - of one long, very gradual crescendo.” To achieve this, Ravel constructed the work from the barest of ingredients. A side drum taps out its distinctive, insistent rhythm throughout, never varying. Above it unfolds a single melody of two 16-bar phrases, repeated again and again. What gives the work its power is not melodic or harmonic development but the ingenious orchestration: each time the theme returns, it is entrusted to a new soloist or section: flute, clarinet, bassoon, oboe d’amore, trumpet, saxophone, and beyond - each colour adding to the cumulative effect.

The piece rises inexorably, almost mechanically, until the final repetitions pile up with brass fanfares and full percussion, forcing the music to the edge of collapse. Only at the very end does Ravel permit the harmony to break away from its C-major trance, plunging into a sudden shift that brings the work to its cataclysmic conclusion.

When Boléro was first performed in Paris in 1928 it created a sensation - half scandal, half triumph. Some listeners were outraged at what they considered its blatant repetition, while others marvelled at its daring conception. Today, it remains Ravel’s most famous work, a paradoxical masterpiece that demonstrates the composer’s supreme control: an experiment in minimal means to achieve maximum impact.

FURTHER LISTENING

If you liked Boléro, then you might like: Ravel Daphnis et Chloé

TEMPO

Maurice Ravel

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835 to 1921)

Symphony No. 3 in c, Organ Symphony

(1886)

ADAGIO - ALLEGRO MODERATO - POCO ADAGIO

ALLEGRO MODERATO - PRESTO

MAESTOSO - ALLEGRO - PIÙ ALLEGRO

Camille Saint-Saëns was one of the great figures of French music in the later 19th century: a prodigy pianist and organist, admired conductor, and an astonishingly versatile composer whose career stretched from the era of Berlioz to the dawn of jazz. He cultivated a reputation for clarity, elegance, and impeccable craftsmanship, sometimes downplaying his own emotional involvement with his works. Unlike his contemporaries such as Wagner or Tchaikovsky, Saint-Saëns did not see music as a vehicle for turbulent autobiography. He preferred to present himself as a craftsman - polished, elegant, respectful of tradition. Yet in his Symphony No. 3 in C minor, the so-called Organ Symphony, he produced a work that is not only an original construction but also stirring and grandly ambitious. He himself considered it his finest achievement in the symphonic field, remarking, “I gave everything to it I was able to give. What I have here accomplished, I will never achieve again.”

The work was commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society of London, which had a long tradition of inviting leading continental composers to supply new works for British audiences - Beethoven and Mendelssohn among them. Saint-Saëns travelled to London in 1886 to conduct the premiere, which was warmly received. He dedicated the symphony to the memory of Franz Liszt, who died shortly before its first performance. Liszt had been a

friend and a great champion of Saint-Saëns’ music, and his influence is palpable here - not least in the way themes are transformed across movements, and in the bold harmonies and colours that Saint-Saëns draws from his orchestra. The use of the organ itself, together with the piano (sometimes four-handed), was also a Lisztian gesture: a willingness to expand the symphonic palette into new territories.

Although known as the Organ Symphony, the work is not a concerto for organ, nor is the instrument present throughout. Rather, the organ is used sparingly but tellingly - as a deep foundation of sound in the slow movement and as an overwhelming force in the finale. This makes its entrances all the more powerful, whether glowing softly under the strings or resounding with majestic brilliance. Combined with Saint-Saëns’ mastery of orchestration, it gives the piece a sonic profile unmatched in the 19th-century symphonic repertoire.

The symphony is laid out in two large parts, each containing two movements. The first begins with a dark, restless introduction in the strings, gradually building momentum into a vigorous Allegro. Here Saint-Saëns’ contrapuntal skill is on full display, themes chasing one another in intricate textures, yet always with clarity of line. This drama subsides into a Poco adagio, where the organ makes its first appearance. Far from thundering, it enters quietly, sustaining luminous chords over which the strings unfold a broad and tender melody.

The effect is one of still serenity, as if time has been momentarily suspended.

The second part opens with a scherzo full of energy and rhythmic drive. Here the piano comes to the fore, its glittering passagework adding sparkle and bite. The music brims with nervous vitality, interrupted by darker undercurrents that hint at something monumental waiting to unfold. When this comes, the effect is unforgettable: a fortissimo C-major chord on the organ, blazing with almost cosmic force, launches the finale. What follows is jubilant to the point of exultant. Themes are treated to fugal development, the orchestra resplendent with brass fanfares, timpani and cymbals, and surging strings, all crowned by the organ’s grandeur. Saint-Saëns builds his material with unflagging energy until the final pages blaze with triumphant affirmation.

The symphony’s impact was immediate and lasting. Audiences were captivated by its sonic splendour, its mixture of drama and poetry. It is a piece that satisfies both head and heart: formally sophisticated, yet viscerally thrilling in the concert hall. For listeners, the combination of orchestra and organ is overwhelming; for performers, it is a work that tests and rewards in equal measure. It has remained by far Saint-Saëns’ most popular symphony and one of the cornerstones of the Romantic orchestral repertoire.

It was also, in a sense, a farewell. Though Saint-Saëns lived until 1921 and continued to compose prolifically, he never returned to the symphonic form. The Third Symphony was both a culmination and a leave-taking, a declaration that he had reached the summit of what he could achieve in the genre. And indeed, few works have

matched it for grandeur or for an exhilarating sense of scale.

In his lifetime, Saint-Saëns was regarded as the embodiment of French musical taste - lucid, elegant, technically impeccable. Yet posterity has judged him more unevenly. While pieces like The Carnival of the Animals, Danse macabre, and the Organ Symphony remain hugely popular, other works are heard less often. His reputation for detachment has sometimes led listeners to underestimate the warmth and invention of his finest music. Still, his command of form and orchestration placed him among the most accomplished composers of his era, admired by figures as different as Liszt, Tchaikovsky, and Fauré.

Remarkably, Saint-Saëns lived into the 1920s, long enough to hear jazz and the early experiments of Stravinsky and Schoenberg. He remained sceptical of the radical new directions of the 20th century, insisting on the values of clarity, balance, and craftsmanship. Yet even in old age he continued to compose prolifically, producing music up to the year of his death. His life, which spanned from the reign of Louis-Philippe to the aftermath of the First World War, made him one of the last great representatives of 19th-century tradition.

RECOMMENDED LISTENING

Listen to (and watch!) again Kazuki Yamada conducting the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra playing Saint-Saëns Organ Symphony at digitalconcerthall.com

FUGUE: a melody constructed in such a way that when played underneath itself it creates harmony. The round London’s Burning or Row, Row, Row Your Boat are simple examples of this. In a complex fugue, the same melody could start again at multiple points and in alternative keys, could be played backwards or turned upside-down, and be slower or faster than its initial version. JS Bach is widely acknowledged to be a master of the structure.

Brigantes Beginners French Classical Music

BRIGANTES BEGINNERS

by Anthony Hart

If you don’t know much about classical music, coming to a concert can be intimidating. If that’s you, you’re not alone. This section, along with the timeline in the programme, gives essential information about the pieces, composers, and their historical and social context, and will help you understand what’s going on!

“...a pleasure rather than a duty...” George Bernard Shaw

“The French are the only people who can make art seem like a pleasure rather than a duty.” George Bernard Shaw

When people think of classical music, their minds may turn first to the German or Austrian composers, like Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and Mahler, or the Italians, like Verdi and Puccini. Yet France has its own remarkable tradition of classical music.

The roots of French classical music reach back to the Middle Ages, when Paris was the beating heart of musical innovation. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, composers at Notre-Dame were the first to experiment with polyphony (the intertwining of independent melodic lines at the same time), which subsequently shaped all Western music. These early experiments were supported by the Church, whose patronage provided stability and resources for composers and musicians. The French monarchy and aristocracy soon recognised that music could be a powerful symbol of authority and taste. During the reign of Louis XIV, the “Sun King” 1643-1715, his court composer, Jean-Baptiste Lully, effectively created the French style of opera, the tragédie lyrique, an elegant counterpart to the flamboyant Italian opera. In these works, music, poetry, and dance were perfectly fused, reflecting the discipline and grandeur of Versailles itself.

Patronage underpinned this creative flourishing, and The Académie Royale de Musique (the future Paris Opera) was established under royal privilege, allowing composers like Lully and Jean-Philippe Rameau to thrive. France

was also a hub of European cultural exchange, attracting foreign musicians. Mozart, for instance, spent time in Paris in 1778, where he encountered the cosmopolitan artistic life of the city and met important musical figures.

The French Revolution of 1789, however, changed the country forever. The aristocratic structures were dismantled, churches closed, court theatres shuttered, and the incomes of musicians cut off. In destroying the old order, the Revolution opened new possibilities. Music now had the potential to speak to the citizen. Public concerts replaced private salons, patriotic hymns and large civic choruses replaced courtly entertainments, and the revolutionary ideal of liberty and fraternity inspired a new sense of artistic freedom. Music became accessible. Ultimately, this upheaval ushered in Romanticism, a movement that prized emotion and individuality over rules and restraint.

Symphonie Fantastique

By the 19th century, French music still had something of an inferiority complex. French composers responded in two ways. Some embraced the German and Austrian model of structure and form wholeheartedly. Others adopted the French revolutionary zeal and developed their own voice, such as Hector Berlioz, whose of 1830 was a feverish tale of love, despair, obsession, and hallucination.

Camille Saint-Saëns walked a delicate tightrope between both these responses. A child prodigy and dazzling pianist, he was steeped in the traditions of Bach and Mozart, yet he had a gift for melody and orchestral

colour that was unmistakably French. His Symphony No. 3 in C minor, known as the Organ Symphony, composed in 1886, is both a homage to German symphonic grandeur and a declaration of French independence. It combines meticulous architecture with sumptuous orchestration, culminating in the thrilling blaze of the organ’s finale. Saint-Saëns himself remarked that he had “given all he could” to this work, and it remains one of the most popular of all French symphonies.

At the same time, Georges Bizet was transforming the sound of the French theatre. His incidental music to L’Arlésienne (1872), written for a play by Alphonse Daudet, brims with vitality and Mediterranean colour. Though the play itself is long forgotten, Bizet’s music endures as a jewel of concise expressiveness. Unlike the sprawling operas of Wagner or the melodramas of Verdi, Bizet’s music is concise, vivid, and irresistibly tuneful. Sadly, he tragically died at 36, leaving behind tantalisingly few works.

The late nineteenth century continued to be a period of institutional renewal. The shock of France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 prompted artists to reassert national pride. That same year saw the founding of the Société Nationale de Musique, whose mission was to champion French composers. Its concerts premiered works by Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Franck, and later Debussy, offering a home for music that sought to define itself against the heavy Germanic tradition. Out of this environment arose a new generation of composers who embraced music’s colour, texture, and atmosphere rather than structure. No one embodied that transformation more than Claude Debussy (1862-1918). Influenced by French symbolist poetry and impressionistic paintings, Debussy broke decisively from the rules of German music. In Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894) and La Mer (1905), harmony expressed colour and atmosphere, like dabs of paint on a canvas. Debussy’s revolution was quieter than Berlioz’s but more far-reaching. For many, he was the composer who finally freed French music from German dominance, proving that France could lead Europe with its own distinctive voice.

Article: The Development and Importance of French Classical Music 9

Maurice Ravel followed Debussy. He is often thought of as another great “Impressionist” composer, although he disliked the term himself. Ravel was a craftsman of extraordinary precision. His Boléro (1928), originally a ballet score, is one of the most famous pieces in the entire repertoire. Built upon a single unchanging rhythm and an endlessly repeated melody, it grows solely through orchestration: each repetition adds new instruments, new colours, and new weight, until the tension that has built up bursts and collapses in on itself in the final seconds, like Torvill and Dean collapsing onto the ice in the Winter Olympics in 1984, for which the piece will primarily be remembered by a certain generation. Boléro can be hypnotic or maddening, depending on your view, but it remains a masterpiece of simplicity through the genius of Ravel’s orchestration.

By the early twentieth century, France was a centre of innovation. After the devastation of the First World War, a group of young composers including Darius Milhaud and Francis Poulenc, came to be known as Les Six. They rejected both the seriousness of German Romanticism and hazy Impressionism, preferring clarity, brevity, and wit. Their music was sometimes inspired by jazz and cabaret and sought to reconnect art with everyday life. It was playful, urbane, and often gently subversive, expressing the French desire to balance intellect and charm. A few decades later, Olivier Messiaen transformed the French organ tradition into something transcendent. His music used birdsong, complex rhythmic cycles, and vibrant harmonic colour. Works such as Quartet for the End of Time and Turangalîla-Symphonie stand among the towering achievements of twentieth-century music. His pupils included Pierre Boulez, who would also push French modernism into more radical and avant-garde terrains.

So, what is the legacy of French classical music compared to other countries? If Germany and Austria gave classical music its intellect, Italy its drama, and Russia its soul and boldness, then France lent it beauty, colour, atmosphere, and elegance. It allowed music to be a pleasure, rather than a duty. The French gave classical music its heart.

FURTHER LISTENING

Try this recording of Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time

Quentin Clare Conductor

The British conductor Quentin Clare made his professional debut at the age of just 25 when he conducted the Hallé Orchestra in the Bridgewater Hall, Manchester. Since then, he has worked with many orchestras in the UK, including the BBC Philharmonic , Royal Northern Sinfonia , Orchestra of Opera North and Ensemble 11 , as well as having performances broadcast on British and European television and radio.

Quentin’s international career has seen him conduct orchestras in Europe, such as the Danish National Symphony , Dutch Radio Philharmonic , Symphony Orchestra of Nancy , and the Nürnberg, Würzburg and Bochum Symphony Orchestras. He is equally experienced in the opera house, working in France, The Netherlands and Germany on productions including Stravinsky's The Rake’s Progress and the French premiere of Robert Carsen’s acclaimed production of Richard III by Giorgio Battistelli.

Much in demand as an inspirational conductor of young musicians, he has conducted the orchestras at the conservatories in Ghent, Birmingham, Den Haag and Weimar.

He has been guest conductor with Young Sinfonia in Newcastle and is music director of The New Mannheim Orchestra and The Brigantes .

James Mitchell Organ

James Mitchell is Organist and Head of Keyboard Studies at Sheffield Cathedral where he is responsible for the organ programme and for training and developing the next generation of cathedral musicians. In addition to accompanying the cathedral’s regular round of services and major liturgical occasions, he contributes widely to its musical life through recitals, education projects, and collaborations with the Cathedral Choirs.

Originally from Crediton in Devon, James was educated at the University of Cambridge, where he read Music at Girton College, graduating with a Double First, before completing an MPhil in Musicology at Emmanuel College. As Organ Scholar at Girton he accompanied the choir on tours to Israel, Singapore and Italy, made two commercial recordings, and appeared on broadcasts for BBC Radio 4 and Cam FM . He has also held organ scholarships at Ely and Manchester Cathedrals and performed at the Royal College of Organists’ Winter Conference.

James has a particular interest in contemporary music and in expanding the reach of the organ to new audiences. His book on composing for the instrument was published by Oxford University Press, and he continues to be active as a recitalist, writer and advocate for new organ repertoire.

Brigantes Orchestra On Stage

FIRST VIOLIN

David Milsom

Emily Chaplais

Jacob George

Michael Walton

Anne Whittaker

Charley Beresford

Helen Tonge

James Warburton

Emily Blayney

Clare Pitchford

Sarah Razlin

Sarah Marinescu

SECOND VIOLIN

Tamaki Hagashi

Hannah Thompson-

Smith

Mabon Jones

Rosie Nicholson

Joanne Atherton

Libby Sherwood

Holly-Rayne Bennett

Lynne Wadsworth

Lucy Thomson

PIANO / CELESTA

Jonathan Fisher

Harvey Davies

VIOLA

Barnaby Adams

Ben Kearsley

Paula Bowes

Jonathan Kightley

Elizabeth Lundie

John Hird

Helen Parkes

CELLO

Gemma Wareham

Tim Smedley

Clara Pascall

Catherine Strachan

Greg Morton

John Parsons

Jonny Ingall

DOUBLE BASS

Pietro Lusvardi

Imogen Fernando

Ria Nolan

Andrew Monk

Matt Barks

HARP

Angharad Huw

ORGAN

James Mitchell

FLUTE / PICCOLO

Laura Jellicoe

Amy-Jayne Milton

Leila Marshall

OBOE / D’AMORE

COR ANGLAIS

Matthew Jones

Nicola Hands

Manon Lewis

CLARINET / BASS CLARINET

Marianne Rawles

Steph Yim

Bethany Nichol

BASSOON / CONTRA

Alex Kane

Alice Gwynne

Beatriz Carvalho

SAXOPHONE

Toby Kelly

Carys Nunn

HORN

Simon Twigge

Abbie Young

Kelly Haines

Jeremy AinsworthMoores

TRUMPET

Anthony Thompson

Gordon Truman

Andrew Dallimore

MIranda Woodward

TROMBONE

Christopher Gomersall

Nicholas Hudson

Garrath Beckwith

TUBA

Willliam Burton

TIMPANI / PERCUSSION

John Watterson

Aidan Marsden

Peter Matthews

Simone HerbertMoores

Shef eld’s Pro Orchestra About Us

The Brigantes (Bri-gan-tez) were a collection of Celtic tribes ruled by Queen Cartimandua in 1st-Century Northern England who populated what is now Yorkshire. Literally meaning “high ones”, Brigantes could refer to nobility or to highlanders living on the Pennines or in Hillforts. The Brigantes were cultured, enjoying theatre and music.

The name Brigantes was chosen for a new orchestra because it encapsulates location, culture and unity: the idea that an ensemble is, roughly speaking, a tribe of musicians.

The Brigantes Orchestra was formed in Sheffield in 2019 in response to the observation that Sheffield did not have a professional symphony orchestra of its own, despite a wealth of local talent. The Brigantes aim to bring highquality orchestral music to the city and surrounding areas, as well as to engage new audiences, those who would not otherwise visit the classical concert hall. This includes a growing population of young musicians in Sheffield’s schools.

All photography with thanks to Eduardus Lee

SOCIAL MEDIA

Instagram: @brigantesmusic

Twitter / X: @thebrigantes

Facebook: facebook.com/brigantesmusic

WITH THANKS

Brigantes Music is a registered charity, and as such benefits from the generous time our supporters give for jobs like flyering, marketing and front-of-house. Thank you to: Anthony Hart, Ruth Milsom & Jonny Ingall.

MADE POSSIBLE BY...

The Brigantes Orchestra would like to thank NEURONATAL LTD

CREDITS

Programme notes: Anthony Hart & Quentin Clare Photography: Eduardus Lee

BECOME A MEMBER

We are pleased to announce new ways you can support the work of The Brigantes Orchestra with a membership programme offering lots of benefits, special offers and exclusive opportunities. These are tiered and, depending on your donation, can include free season tickets, branded Brigantes merchandise (like the polo shirts some of our front-of-house team are wearing, or a framed poster), reductions on tickets for your friends and family, a printed acknowledgement of your support in each programme booklet of the season, free interval drinks at our concerts, opportunities to sit in the orchestra during rehearsals and see the pieces put together, chances to meet the players, invitations to VIP receptions...

Further details are available at contact@thebrigantes.uk.

BECOME A VOLUNTEER

We are looking for volunteers who would like to be involved in the promotion and development of the orchestra so that it can continue to realise its charitable aims. Those willing to distribute flyers in suitable places in their neighbourhood, add us to local newsletters and social media groups, help with fundraising, or take on some roles in front-of-house should email us at contact@thebrigantes.uk.

THE BRIGANTES ORCHESTRA

Sheffield, S11

Brigantes Music is a Registered Charity: 1187752

© 2025 The Brigantes Orchestra