Reimagining HPHA Series

of Hawai‘i’s Housing Exploring Housing for All

of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

INVESTIGATORS:

Sierralta, AIA

Strawn,

Future

University

PRINCIPAL

Karla

Brian

AIA

HAWAI‘I PUBLIC HOUSING AUTHORITY

The HPHA is the state of Hawai‘i’s primary housing agency. The Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority is committed to promoting adequate and affordable housing, economic opportunity, and a suitable living environment free from discrimination. HPHA focuses its efforts in developing affordable rental and supportive housing, public housing and the efficient and fair delivery of housing services to the people of Hawai’i.

hpha.hawaii.gov

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I COMMUNITY DESIGN CENTER

The UHCDC is a teaching practice and outreach initiative led by the School of Architecture at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa that operates as a platform for students, staff, faculty, and partnered professionals to collaborate on interdisciplinary applied research, planning, and design projects that serve the public interest. These projects offer service-learning opportunities for students through academic instruction, internship, and post-graduate employment.

uhcdc.manoa.hawaii.edu

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing Exploring Housing for All

PROJECT REPORT

University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS:

Karla Sierralta, AIA

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, School of Architecture

Brian Strawn, AIA

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, UH Community Design Center

The Re-Imagining HPHA Series is an inter-departmental and multidisciplinary initiative conducted by a group of Principal Investigators at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa through the University of Hawai'i Community Design Center aimed at re-thinking public housing programs and facilities in an effort to support HPHA’s mission and long term goals.

Reimagining HPHA Series

CONTACT INFORMATION

Karla Sierralta, AIA, UHM SoA

Brian Strawn, AIA, UHCDC 2410 Campus Road

Honolulu, HI 96822

Email: karlais@hawaii.edu

Email: bstrawn@hawaii.edu

CITATION

Sierralta, K, Strawn, B. 2023. Future of Hawaii’s Housing: Exploring Housing for All. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai‘i

This publication is available free of charge as a downloadable PDF at hawaiihousinglab.org

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This effort was only made possible thanks to the kindness and generosity of the 30 families we interviewed across the archipelago. Team acknowledgments are listed at the end of this report.

IMAGE CREDITS:

All illustrations and diagrams by UHCDC project team. All photography by Sierralta and Strawn unless otherwise noted. The authors have attempted to acknowledge all sources of other images in this report and apologize for any errors or omissions.

GRAPHIC DESIGN CONSULTANT:

Jill Misawa

Distribution of this work is licensed to the UHCDC under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives

4.0 International License (CC BY-ND 4.0) unless otherwise noted. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/.

© 2023 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center

Part V: Prototyping & Piloting

Tools for Engagement 120

Conceptual Underpinnings 122

Sorting Cards 124

Digital Application: Adapting Scout 126

Custom Environment: Lawn Loungers 130

Engagement Pilot: Parking Day 140

Research Feedback: EPIC Conference 150

Delivery Format: Toolkit as Box Set 154

Key Findings 156

Part VI: Supporting Efforts 158

Sakamaki Extraordinary Lecture 160

Building Voices 2019 162

Interview with David Baker 168

Interview with Marsha Maytum 170

Course Integration: Spring 2019 172

Course Integration: Spring 2021 176

Course Integration: Spring 2022 180

Next Steps 184

References 188

Acknowledgments 192

Executive Summary 7 Introduction 8

HPHA

Mapping

Takeaways

II: Foundational User Research 34 Thirty In-Home Family Interviews 36 Research Analysis 40 Thirty-Six Design Actions & Opportunities 46 Twelve Design Strategies 52 Key Findings 54 Part III: Developing a Design Framework 56 Case Studies 58 Depicting Design Opportunities 62 Pandemic Studies 66

Guiding Principles for Holistic Housing 74 An Illustrated Handbook 78 Part IV: Understanding Density 90 Existing Conditions & Future Needs 92 Rural to Urban Core Samples 94 Lots and Blocks Along the Rail 100 Multi Family Residential Typologies 104 Variations of an Average Urban Block 108 Potential Unit Layouts 114 Key Findings 118 Contents

Part I: Background 20 Hawai‘i’s Housing Crisis 22

by the Numbers 24 HPHA’s Role in Solving Hawaii’s Housing Crisis 26

Opportunities 28

32 Part

Five

Executive Summary

6 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

This report documents the findings of three closely related projects conducted by the University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority, including: “Future of Hawai‘i’s Public Housing,” “Understanding Density and Local Typologies,” and “Covid-19 Pandemic Analysis”. Together, these projects, referred to as “Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing: Exploring Housing for All,” aim to inform the design of future development and redevelopment projects by HPHA.

These efforts are part of the “Re-Imagining HPHA Series,” a multi-departmental and interdisciplinary approach to re-thinking public housing programs and facilities to support HPHA’s mission and long-term goals.

The research took place in two parallel tracks:

In the first track, our team interviewed 30 families in their homes across the Hawaiian Archipelago, met with topic experts, and analyzed local & global case studies to develop guiding principles and design guidelines that would serve as foundational knowledge for subsequent studies.

The second track centered on density studies and visualizations, including local multifamily housing typologies and a survey of half-mile neighborhood samples spanning rural to urban contexts. These studies inform the development of strategies for comfortable density across the state.

Our team piloted and tested prototypes with a community engagement approach to refine key concepts and strategies during the process. Our academic setting provided additional opportunities to inform the research, including course integrations, interviews, conferences, and symposiums.

In 2020, amidst the COVID-19 global pandemic, the team re-examined research findings through the lens of the ongoing crisis.

These efforts culminated in the development of the Holistic Housing Design Framework, intended to inspire future designs, inform redevelopment processes, and support community engagement activities in the planning of housing for all in Hawai‘i.

The groundwork generated from this research is intended to inform future work by government agencies, business community leaders, students, design experts, builders, developers, and non-profits alike.

7

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA

University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority 8

Introduction

CommunityBusiness

Government Agencies

Community Residents

Students

NonProfits

Developers

Builders

Design Experts

Holistic Housing Agents Diagram: Active participants in designing, building, supporting, and creating Walkable, Sustainable, and Equitable communities in Hawai‘i.

Hawai‘i has the fourth-highest average cost-of-construction in the world.1 It now takes the average person 40 years to save for a down payment on a median-priced home.2 The state has the highest per-capita homelessness rate in the country, tied with New York City.3 Housing is one of our most pressing issues, and the need for affordable housing, in particular, continues to grow exponentially.

The Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority (HPHA) is the state’s primary housing agency, managing 85 properties spread across five islands. With properties nearing an average age of 48 years, the HPHA is in dire need of renovating or replacing a large percentage of its portfolio.

To address this challenge, the HPHA has begun a major initiative to enter into a series of public-private partnerships to redevelop its low-income public housing portfolio into vibrant, mixed-income / mixed-finance communities.

HPHA’s Executive Director Hakim Ouansafi is spearheading a series of efforts to increase the quality and availability of housing for all in Hawai‘i.

The University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center’s partnership with the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority aims to conduct research in support of these goals.

1. Rider Levett Bucknall, International Report. Construction Market Intelligence, Second Quarter 2019, accessed October 14, 2019.

2. Unison, 2019 Home Affordability Report, accessed October 14, 2019.

3. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, The 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, Part 1: Point-in-time Estimates Of Homelessness, December 2018.

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by

Sierralta, AIA and

Strawn, AIA 9

Karla

Brian

Reimagining HPHA Series

RE-IMAGINING HPHA SERIES

The Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing is a component of the “Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority: Re-envisioning Public Housing - Phase 1 Project”, a collaboration between the UHCDC, housed within the School of Architecture (SoA), along with partners from the Department of Sociology (DOS) and the Department of Urban and Regional Planning (DURP) at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

This collaborative research effort represents a multi-departmental and interdisciplinary approach to re-thinking public housing programs and facilities in an effort to support HPHA’s mission and long-term goals.

A series of studies encompassed qualitative and quantitative assessments through various research, workshop, interview, and other engagement exercises aimed at informing future operations, renovation and capital improvement projects.

The resulting reports are compiled under the title Re-Imagining HPHA Series, including:

• Public Housing in Hawai‘i, focused on the social realm of public housing by Nathalie Rita, Jennifer Darrah-Okike, and Philip Garboden.

• PHA’s & the Affordable Housing Crisis, an analysis of the role of public housing authorities (PHA’s) in the development of cities by Philip Garboden.

• Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing, exploring the design aspects of Housing for All across Hawai‘i by Karla Sierralta and Brian Strawn.

Reimagining HPHA Series Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing Exploring Housing for All The Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing Exploring Design Public Housing in Hawaii Understanding Residents PHA’s & the Affordable Housing Crisis Advancing Development

Public Housing in Hawai‘i Assessing the Needs of Public Housing Residents Reimagining HPHA Series University Hawai‘i Community Design Center Jennifer Darrah-Okike, Ph.D.

10 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

Re-Imagining HPHA Series - Report Covers

The Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing project sought to examine existing conditions, challenges, and opportunities related to the design of housing for all in Hawai‘i.

The project was charged with:

• Understanding the broad context of housing in Hawai‘i from a design perspective.

• Considering residents currently housed in properties managed by HPHA across the state.

• Developing guiding principles and design guidelines for future developments and redevelopment.

Five key questions guided this project:

1. How might we design housing for all in Hawai‘i?

2. How do we provide more housing without compromising mountain vistas, parks, or farmlands?

3. What attributes should be considered that are unique to our context in Hawai‘i?

4. How do we create walkable density without locals feeling overcrowded?

5. How can current and future residents become more involved in the design process of their communities?

The main outcome of this effort is the Holistic Housing Design Framework, an illustrated handbook intended to inspire future designs, inform redevelopment processes, and support community engagement activities in the future planning of mixed-income / mixed-finance housing in Hawai‘i.

METHODOLOGY & APPROACH

The Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing project was centered on an exploratory, bottom-up, design research approach, rooted in the experience of Hawai’i’s residents.

Exploratory Research4 is a type of inquiry intended to unpack a particular topic broadly. In contrast to providing a final solution to a specific problem, it centers on establishing a better understanding of the problem itself by revealing a variety of factors that may be linearly related or divergent in nature.

Based on this methodology, a series of non-linear activities were conducted over three years (2019-2022). Learnings from each activity informed subsequent phases of the research, generating a complex loop of production, analysis, and synthesis.

Through an iterative process, insights were revealed and refined. Contextual oneon-one interviews, secondary research, affinity mapping, drawing, prototyping at multiple scales, and piloting tools and processes were critical components of this effort.

4. Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6th edition, Pearson Education Limited. Singh, K. (2007) “Quantitative Social Research Methods” SAGE Publications, p.64

FOCUS & OUTCOMES

Future

11

of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA

This report attempts to organize information in chronological order, however, it is important to reemphasize this project was not conducted in a linear fashion and some activities went through multiple rounds of user testing and design refinements.

Research activities conducted by the team included the following:

Foundational Research

• Ethnographic Interviews: Thirty in-home family interviews were conducted at seventeen HPHA properties on five islands (O‘ahu, Hawai‘i, Kaua‘i, Maui, and Moloka‘i) during the Spring of 2019. Qualitative data was analyzed and translated into design opportunities.

Background Research

• Documents related to the housing crisis in Hawai‘i and conversations with HPHA officials provided background information for this effort.

Secondary Research

• Case Studies: Forty-five case studies and analogous exemplars were compiled and analyzed. Twenty of these caste studies were focused on multi-family housing.

• Density Survey #1: Analysis of density and housing in 20 half-mile core samples of urban fabric across the Hawaiian Archipelago, zooming in on typical blocks.

• Density Survey #2: Mapping of lots and blocks along the future rail in Honolulu.

• Density Survey #3: Analysis of seven local multi-family housing typologies, from low to mid to high rise located on Oahu’s urban core.

• Pandemic Studies: A media review of recent resources and publications relevant to the research in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, was conducted during the Spring and Summer of 2020.

Design & Visualization Efforts

• Testing Density #1: Twenty-six low-to-high building volumes on an average 2-acre urban block were generated and studied.

Exploratory Research Diagram: Linear or conclusive vs. non-linear research comparison

12 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

vs.

• Testing Density #2: Ten potential unit layouts for dense housing projects were produced.

• Design & Prototyping #1: Thirty-six drawings were created to communicate design opportunities.

• Design & Prototyping#2: A set of sorting cards were designed to test the communication of values and preferences.

• Design & Prototyping#3: KPF UI Digital App was adapted to the Hawaiian context.

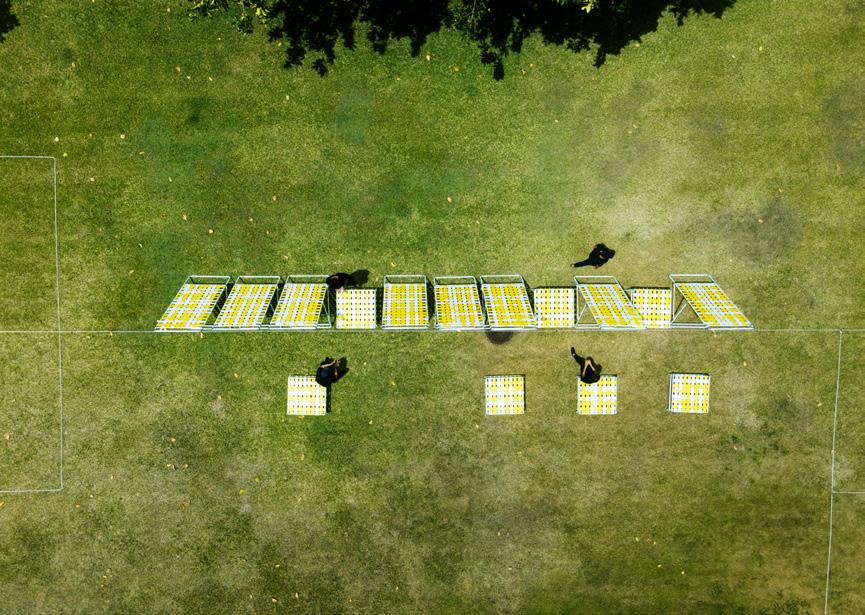

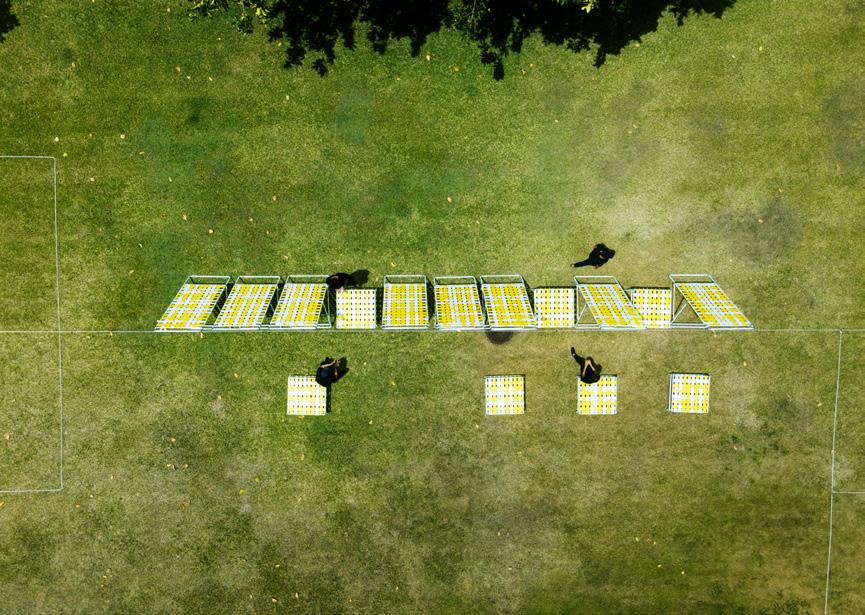

• Design & Prototyping#4: A custom spatial environment for engagement was designed, modeled, and fabricated at full-scale.

• Design & Prototyping#5: A concept for a “toolkit” was developed and mocked-up during the summer of 2021.

Pilots and Mock-ups

• Pilot#1: The spatial environment, sorting cards, and the app were tested with the general public in Kaka’ako (Parking Day Honolulu 2019).

• Pilot#2: Sorting cards and the digital app were tested with professionals at the EPIC conference ‘Agency’ in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 2019.

• Pilot#3: Configurations of the full-scale spatial environment were tested at the UH campus in 2020.

Other Supporting Activities

• Public Lecture: Density Done Right by Allison Arieff on May 2, 2019.

• Symposium: The 2019 Building Voices Symposium centered on Housing for All on October 1, 2019, included local and national experts and professionals.

• Expert interviews: Two experts were interviewed during the Fall of 2019.

• Course integrations: Three UHM SoA third-year undergraduate studios were aligned with this research project during the Spring semesters of 2019, 2021, and 2022 taught by Associate Professor Karla Sierralta, AIA.

A series of meetings with HPHA representatives to discuss ongoing/planned initiatives, preliminary findings, and draft deliverables also informed the work.

PUBLIC DISSEMINATION & FEEDBACK

In an attempt to disseminate and broaden the conversation surrounding the research topic and develop the concepts presented in this report, the team participated in public presentations, publications, and award submittals centered on design concepts, prototypes, visualizations, and other proof-of-concept elements of this project.

As a result, critical feedback from experts, academic peers, and community members contributed to the evolution of the work, and components of this project have been honored with various awards.

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and

Strawn, AIA 13

Brian

Public Presentations

• “The Future of Housing in Hawai‘i” was presented at the Building Voices: Housing for All in October 2019, together with key partners and collaborators. The event was held at the Hawai‘i Convention Center as one of the seminar tracks in the CSI Pacific Building Trade Expo in partnership with the American Institute of Architects.

• “Hawai‘i Housing Lab” was presented at the ACSA 108th Annual Meeting OPEN in June 2020 and published in the peer-reviewed conference proceedings.

• “Mobile Platform for Community Engagement” was displayed during the UIA 2021 Rio 27th World Congress of Architects and published in the peer-reviewed conference proceedings.

Awards

• 2020 AIA Honolulu Honorable Mention Award in the Institutional category for the design of “Lawn Loungers: Portable Spaces for Community Engagement.” American Institute of Architects Honolulu Design Excellence Awards.

• 2021 ACSA Course Development Prize for “Just Play” with Professors Priyam Das, Cathi Ho Schar and Phoebe White. Just Play included a teaching module based on the Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing project.

• 2022 ACSA Collaborative Practice Award for “The Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing, a bottom-up exploratory research collaboration”. This research project was recognized by the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture in thier Annual Architectural Education Awards in 2022.

The Hawai‘i Housing Lab wesbite was launched to document, collect, share and communicate the knowledge derived from this project and future efforts rooted in the research and collaboration between UH and HPHA. This ongoing researchbased design platform is intended to continue to explore Holistic Housing for the Hawaiian Archipelago.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized into six sections:

• Part I introduces key background knowledge, including an overview of the housing problem in Hawai‘i and HPHA’s current challenges and opportunities with a short essay by topic expert Philip Garboden.

• Part II focuses on foundational user research and key findings resulting from 30 in-home interviews at properties managed by HPHA across Hawai‘i.

• Part III provides a summary of key efforts conducted to develop the design framework including case studies, the analysis of the COVID-19 global pandemic, and resulting guiding principles.

• Part IV describes a series of analytical and design exercises focused on understanding density.

• Part V illustrates key pilots and mock-ups conducted during the design process.

• Part VI summarizes supporting efforts and learnings.

14 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

Hawai‘i Housing Lab Diagram illustrating the Future of Hawaii’s Housing project as foundational research for future work.

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing

15

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing Stakeholders & Deliverables Diagram: illustrates the FOHH project’s deeply collaborative process and the parallel work flows that form its overall approach.

Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

PHA’s and the Affordable Housing Crisis Urban & Regional Planning Faculty + Graduate Student Assistant

Public Housing in Hawai‘i Urban & Regional Planning Faculty + Sociology Faculty + PhD Student

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing (FOHH) SoA Faculty + Community Design Center Researcher + 5 Project Staff +11 Student Employees)

Card Sets

Citizens feel left out of the design processes that build their communities.

Residents have a nested understanding of domesticity and desire more walkable, sustainable, and equitable neighborhoods.

Locals hold a general skepticism toward density.

Ethnographer / Design Strategist

Integrated Studio Arch 342 Spring 2019 (11 students)

MOU was signed between the University and the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority aiming to conduct research in support of increasing the quality and availability of affordable housing in Hawai‘i (2018).

Work by three teams began in the Spring of 2019.

Director Urban Data Analytics Urban Innovation Architect, Urban Data Analyst / Web Developer

PUBLIC LECTURE & EXHIBIT

Topic expert lectures about Density Done Right for the Extraordinary Lecture Series open to students from the entire campus.

May 2019

SUMMER SHARE OUT

Teams share in-progress research findings with each other and HPHA leadership to crosspollinate ideas.

June 2019

PARKING DAY HONOLULUPrototypes for community engagement are tested in the field at a public event in Kaka‘ako (estimated to be Honolulu’s densest neighborhood by 2030).

September 2019

EPIC CONFERENCEPrototypes tested at international conference on ethnography in business at RISD.

November 2019

HOUSING FOR ALL SYMPOSIUMFOHH PI’s Co-chair event where local and national experts discuss strategies to achieve Housing for All in Hawai‘i.

October 2019

PANDEMIC PORTALCovid-19 Pandemic triggers urgent need for an HPHA online portal. Team works on pop-up website, informing decision to revise developed design framework to incorporate learnings from the pandemic.

April 2020

Visualizing Density Catalog Plan Your Neighborhood App Lawn Loungers Mobile Platform Nested Domesticity Framework for Walkable Sustainable Equitable Communities

Case Studies & Precedents Local Density Studies 30 In-Person Interviews Expert Interviews + + +

2019 2020 Spring Spring Summer Fall 16 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Development Perspective

Social Perspective

Toolkit as box-set Concept

Proposal of Ideas for Community Engagement

Design Perspective

Re-Imagining HPHA Report Series

Revisions with learnings from the pandemic

Holistic Housing Design Framework

Development of a Design Framework Density Visualizations from Rural to Urban

Design & Architecture Writer

Integrated Studio Arch 342 Spring 2021 (19 students)

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing

Online platform created to document, collect, share, and communicate knowledge derived from the FOHH project.

Integrated Studio Arch 342 Spring 2022 (9 students)

Spring Spring Summer Summer Fall Fall

PILOTLawn Loungers is piloted to test deployment process and potential configurations.

June 2020

2021

GRADUATE THESIS PROJECTS

Student thesis projects chaired by participating faculty have also contributed to these conversations.

• AY 19-20 “Exploring Low Rise Density Housing in Hawai‘i”

• AY 20-21 “Urban Agriculture and Housing as Agents for Social Change”

• AY 21-22 “Improving Quality of Life for Kupuna in Urban Honolulu”

Fall 2019+

AIA AWARDLawn Loungers honored with an AIA Honolulu Design Award as a mobile platform for community engagement.

November 2020

SUMMER BRAINSTORM

SoA and DURP Principal Investigators generate concepts for visualizing and communicating complex development financing process for inclusion in report series.

July 2021

STUDIES & EFFORTS

-

2022

Generated by the FOHH

• HPHA Digital Transformation

• Density Study for an existing 15-acre site

2021+

CONTINUED STUDIO INTEGRATION

Future housing studios to build on the work of previous studios and focus on designs that will help expand visualizations for denser, walkable, sustainable and equitable communities in Hawai‘i.

Spring 22+

ACSA COURSE DEVELOPMENT PRIZE

Equity-focused game centered on teaching high school students about housing in Hawai‘i based on the FOHH project awarded by Columbia University’s Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture and the ACSA.

January 2021

ACSA COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE AWARD

FOHH project recognized by the ACSA for “community partnerships in which faculty, students and neighborhood citizens are valued equally and that aim to address issues of social injustice through design.”

January 2022

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA

17

Core Projects

Problem Discovery & Definition Analysis & Concept Generation DISCOVER DEFINE Foundational Research Background Research Secondary Research Design and Visualization Supporting Efforts 1 2 6 7 4 5 3 21 20 19 18 Understanding the topic area & Learning from residents and experts Synthesizing the research & Translating findings into concepts BACKGROUND RESEARCH 1 Understanding HPHA FOUNDATIONAL USER RESEARCH 2 Ethnographic Interviews SECONDARY RESEARCH 3 Case Studies 4 Density Survey #1 Archipelago Micro Samples 5 Density Survey #2 Urban Lots and Blocks 6 Density Survey #3 Multi-Family Typologies 7 Pandemic Studies Insights and Pandemic Portal DESIGN AND VISUALIZATION 8 Testing Density #1 Variations of an Average Urban Block 9 Testing Density #2 Unit Layouts 10 Design & Prototyping #1 Illustrating Design Opportunities 11 Design & Prototyping #2 Sorting Cards - Imagine Your Community & Design Your Home 12 Design & Prototyping #3 Digital App - Plan Your Neighborhood 13 Design & Prototyping #4 Spatial Environment - Lawn Loungers 14 Design & Prototyping #5 Toolkit as Box Set Proof-of-Concept PILOTS AND MOCK-UPS 15 Pilot #1 Parking Day 16 Pilot #2 EPIC Conference 17 Pilot #3 Spatial Configurations SUPPORTING EFFORTS 18 Public Lecture Allison Arieff 19 Symposium Building Voices 2019 - Housing for All 20 Expert Interview #1 David Baker 21 Expert Interview #2 Marsha Maytum 22 Course Integration #1 Holistic Housing Studio S19 23 Course Integration #2 Holistic Housing Studio S21 24 Course Integration #3 Holistic Housing Studio S22 PUBLIC DISSEMINATION & AWARDS 25 Building Voices 2019 Panel Discussion 26 ACSA 108th 2020 Peer-Reviewed Paper & Presentation 27 AIA Design Award 2020 Honorable Mention Institutional 28 UIA Congress 2021 Peer-Reviewed Project 29 ACSA Award 2021 Course Development Prize 30 ACSA Award 2022 Collaborative Practice 31 Hawai‘i Housing Lab Online Research-Based Design Platform

Value Adds 18 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

Prototyping multiple iterations & Selecting final ideas for testing

Piloting with users & Packaging the final products

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing Design Process Diagram based upon the Triple Diamond Diagram by Zen Desk, which is modeled after the Double Diamond Model developed by the British Design Council in 2005, which itself builds upon the work of the renown linguist Béla H. Bánáthy from 1996.

Design & Development Assessment & Refinement Public Availability Future Projects & New Applications DEVELOP VALIDATION ROLLOUT FUTURE Background Research Pilots and Mock-Ups Supporting Efforts Public Dissemination 31 12 13 14 9 10 11 8 30 27 28 29 26 23 24 25 22 15 16 17

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA 19

Part I: Background

University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority 20

Hawai’i’s Housing Crisis 22 HPHA by the Numbers 24 HPHA’s Role in Solving Hawai‘i’s Housing Crisis 26 Mapping Opportunities 28 Takeaways 32

21

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA

Hawai‘i’s Housing Crisis

Hawai‘i is known around the world as a tourist destination and is beloved for its spectacular beaches, volcanic landscapes, and unique culture of aloha. This global adoration has resulted in a series of astounding realities.

Honolulu, the state capital, has the fourth-highest average construction rate in the world at $196 sq/ft, only Oslo ($251 sq/ft), San Francisco ($212 sq/ft), and New York ($207 sq/ft) are more expensive to build in.5 Today, $93,300 or less is considered “low income” for a family of four on Oahu6 and it now takes 40 years to save for a down payment on a median-priced home on a median income in Honolulu, matching San Francisco as one of the most expensive markets in the country based on income.7 Not coincidentally, Hawai‘i has the highest per capita homelessness rate in the country, tied with New York City.8 Honolulu is also the fourth densest city in the US, with 11,548 people per square mile, and its 953,207 residents live in just 600.7 square miles.9

Geographic location, scarcity of land, astronomic construction costs, and speculative investment have led to an unattainable market. The need for affordable housing continues to grow exponentially. By 2025, Hawai‘i needs approximately 65,000 affordable housing units.10

Housing is Hawai‘i’s most pressing issue.

CONSTRUCTION

4th densest city in the US

Honolulu is also the fourth densest city in the US with 11,548 people per square mile, and its 953,207 residents live in just 600.7 square miles.11

4th highest construction cost in the world

Honolulu, the state capital, has the fourth highest average construction rate in the world at $196 sq/ft, only Oslo ($251 sq/ft), San Francisco ($212 sq/ft), and New York ($207 sq/ft) are more expensive to build in.12

HIGHEST HOMELESSNESS RATE IN THE US

Not coincidentally, Hawai’i has the highest per capita homelessness rate in the country, tied with New York City.13

BACKGROUND

22 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

AFFORDABILITY

40 years to save for a down payment

$93,300 is now low-income for a family of 4

Today, $93,300 or less is considered “low income” for a family of four on O’ahu14 and it now takes 40 years to save for a down payment on a median-priced home on a median income in Honolulu, matching San Francisco as one of the most expensive markets in the country based on income.15

5. Rider Levett Bucknall, International Report. Construction Market Intelligence, Second Quarter 2019, accessed October 14, 2019.

6. Anita Hofschneider, “$93K Is Now Considered Low-Income For Honolulu Family Of 4,” Honolulu Civil Beat, April 23, 2018.

7. Unison, 2019 Home Affordability Report, accessed October 14, 2019.

8. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, The 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, Part 1: Point-in-time Estimates Of Homelessness, December 2018.

23.8% elderly population in Hawai’i by 2045

By 2045, the share of elderly population in Hawai’i is projected to increase to 23.8 percent, up from 7.9 percent in 1980.16

AGING POPULATION SHRINKING HOUSEHOLD

77%

83% of US household growth will be over the age of 65, more than half of this growth will be 75 and older.17

9. Wilson, S. et al “Patterns of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Population Change: 2000 to 2010, 2010 Census Special Reports,” United States Census Bureau, Issued September 2012.

10. Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism, Measuring Housing Demand in Hawaii, 2015-2025 Report, March 2015.

11. See note 9

12. See note 5

13. See note 8

14. See note 7

15. See note 6

16. Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism, “Population and Economic Projections for the State of Hawaii to 2045”.

17. Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, “ Updated Household Projections, 20152035: Methodology and Results” (https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/ sites/default/files/household_ growth_projec- tions2016_jchs. pdf)

18. Ibid

83% of US household growth will be 65+ years old

US household growth will be single-person and married couples without children

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA 23

77% of US household growth will be made up of single-person households and married couples without children.18

HPHA by the Numbers

As the state’s primary housing agency, HPHA manages 85 properties spread across five islands with a total of 6,270 housing units. In addition to managing Hawai‘i State and Federal Public Housing units, HPHA houses residents through subsidy and rental assistance programs including the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program and State-Aided Elderly Public Housing.

These properties serve over 35,000 residents, many of which are vulnerable seniors and children. The agency works to ensure accessibility for all residents, including communicating information in 20 languages and developing digital offerings that streamline processes for residents.

With properties at a 98% occupancy rate, and a priority to help in preventing homelessness, increasing the housing inventory is a critical need. In addition, many of HPHA’s properties are nearing the average age of 48 years old and are in need of renovating or replacement.

HPHA has begun a major initiative to enter into a series of public-private partnerships to redevelop its lowincome public housing portfolio into vibrant, mixedincome/mixed-finance communities.

The agency is seeking to redevelop its aging property inventory through dense, mixed use projects that piggyback on the Honolulu Rail Transit project (HART) and the City’s TOD incentives. This strategy will enable HPHA to expand the inventory of affordable housing units on Oahu, leveraging financing through public private partnerships, and create more livable, vibrant, and integrated communities for public housing residents and the community at large.

The following section presents an overview of current facts, challenges, and future potential with a short essay by topic expert Philip Garboden.

HOUSING HAWAI’I

35,000 people served

In 2019, HPHA was able to serve over 35,000 people with safe, decent and affordable housing through the efficient and fair delivery of housing services.

20% with disabilities

HPHA is dedicated in providing housing for all. Better assisting persons with disabilities by providing decent and safe rental housing is one of HPHA’s goals.

28% children

HPHA strives to provide housing for families. Today, the HPHA Federal and State Low Income Public Housing programs combine to serve over 5,100 families.

12% adults older than 71

Since the mid 1960’s, the HPHA (then the Hawaii Housing Authority) had been providing housing specifically designed for the special economic, social and physical needs of Hawaii’s senior citizens.

BACKGROUND

19 24 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

10% homeless at admission

HPHA works to reduce homelessness. Across the State of Hawai‘i, housing for our residents in the low-income to workforce income spectrum is on the top priority list at all government levels. HPHA works closely with Federal State and County partners to find solutions to increase our housing inventory and prevent homelessness.

HOMELESSNESS UNITS

6,270 housing units

HPHA manages 6,270 units spread across 85 properties. The mix of these units consist of 933 studios, 1,583 one bedrooms, 1,656 two bedrooms, 1,551 three bedrooms, 487 four bedrooms, and 60 five bedrooms.

EXPANDING IMPACT

13,598 people housed with rental assistance

There is increased federal support. Subsidy programs at HPHA have increased. Eight years ago the number of individuals housed through subsidy programs was only 8,296.

98% occupancy rate

HPHA achieved a record high occupancy of 98% in its public housing programs. The Section 8 Program is rated a high performer under the Federal Assessment System.

2100/20

translations in 20 languages

HPHA ensures the programs and activities operate according to Federal and State requirements, agency policies, fair housing laws and regulations. In the past years HPHA has improved language accessibility for limited English proficient program participants and worked to provide written translations of vital documents in different languages.

Future

25

19. The facts and figures presented on this page were provided by HPHA at the initiation of this project in 2019.

of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA

HPHA’s Role in Solving Hawai‘i’s Housing Crisis

by Philip M.E. Garboden

When people think of Public Housing Authorities, indeed if people think of Public Housing Authorities, the image in their head is rarely inspiring. PHAs are viewed as the caretakers of a dying era, tasked for decades with maintaining a nation’s aging public housing stock with grossly insufficient resources. The stock itself isn’t viewed particularly favorably either, with many critics suggesting that not only is it ugly, but that its poor design is at least partially responsible for its well-publicized and somewhat catastrophic failures.

And yet, while the above narrative has calcified in the minds of the general public, it falls far short of reality. First and foremost, the vast majority of public housing in the United States did not fail and continues to provide safe and secure housing for millions of poor families.

Right now in Hawai‘i, dozens of public housing sites sit inconspicuously in communities across the islands, offering deeply subsidized housing that neither the market, tax credits, nor any of the myriad “workforce” housing plans can even hope to approach. These units, along with housing vouchers, exist as the only permanent housing available to the State’s most vulnerable residents.

But more to the point of this document is that PHAs have not spent the last forty years simply administering housing vouchers and winding down the clock on public housing. Instead, many have responded by taking an active role in expanding the stock of affordable housing. They’ve done this either directly as developers or by serving catalytic roles within larger public-private partnerships.

Indeed, in a recent study of a random sample of Public Housing Authorities, we found that at least 58 percent of PHAs (and 80 percent of large PHAs) have partnered in some form mixed-finance redevelopment, generating thousands of new units of subsidized housing.

Based on our interviews, it seems that the idea of “Public Housing Authority as developer” dates back to the 1990s and HUD’s HOPE VI program, which was designed to reduce the amount of

“A recent study found that... 58 % of PHAs (and 80% of large PHAs) have partnered in some form with mixedfinance redevelopment, generating thousands of new units of subsidized housing.”

BACKGROUND

26 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

severely distressed public housing through demolition and conversion to mixed-income communities. While the program is largely viewed as a failure due to its inability to replace the demolished affordable housing stock (instead using vouchers, which many families failed to use), it nonetheless generated a set of best practices for mixed-finance development that would become a durable part of the PHA toolbox.

In the decades that followed, many PHAs continued to push into mixed-finance development, often leveraging their land assets in combination with Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) units, Project Based Section 8 units, and market rate housing. In recent years, this process has accelerated due to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD).

In a nutshell, RAD converts public housing to Project Based Section 8, guaranteeing a one-for-one replacement of hard-unit deeply-affordable housing. While some RAD conversions simply transition the existing stock, many PHAs have taken the opportunity to leverage RAD authority in combination with other subsidy programs to increase density and create mixed-income communities that, unlike HOPE VI, do not push poor families out of the area.

Put together, all this suggests that Public Housing Authorities in general, and HPHA in particular are in a uniquely powerful position when it comes to the affordable housing crisis. By proactively fighting to increase the subsidized housing stock, particularly those units that serve our most vulnerable residents, PHAs can, have, and will continue to be partners in the fight for a housing system that leaves no one out.

The pages that follow present a vision for how HPHA can not only preserve and expand Hawai‘i’s affordable housing stock, laudable goal on their own, but do so in such a way that embraces human-centered design endogenous to Hawai‘i’s unique cultural and ecological context.

Philip M.E. Garboden

Professor

“Public Housing Authorities in general, and HPHA in particular are in a uniquely powerful position when it comes to the affordable housing crisis”.

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by

AIA and

Strawn, AIA 27

HCRC

in Affordable Housing Economics, Policy, and Planning. Department of Urban and Regional Planning. University of Hawai’i Economic Research Organization.

Karla Sierralta,

Brian

(Right) Properties

Managed by HPHA

Along the Future Rail diagram: illustrating existing and proposed dwelling units per acre.

Future HART Stations:

1. East Kapolei

2. UH West Oahu

3. Hoopili

4. West Loch (Farrington / Leoku)

5. Waipahu Transit Center (Farrington / Mokuola),

6. Leeward Community College

7. Pearl Highlands

8. Pearlridge

9. HālawaAloha Stadium

10. Makalapa - Pearl Harbor Naval Base

11. Lelepaua - Honolulu Airport

12. Āhua - Lagoon Drive

13. KahauikiMiddle Street

14. Mokauea - Kalihi

15. Niuhelewai - Kapālama - HCC

16. Kūwili - Iwilei

17. Holau - Chinatown,

18. Kuloloia - Downtown

19. Ka’ākaukukuiCivic Center

20. Kūkuluāe’o - Kaka’ako

21. KāliaAla Moana Center

Key development projects are marked with an asterix.

Mapping Opportunities

Providing safe, decent, affordable housing plays a key role in improving lives and communities and is the primary mission of the HPHA.

The majority of HPHA’s annual budget is federally funded through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). To protect this federal interest, HUD attaches restrictive covenants, through a declaration of trust, on HPHA properties requiring their continued use as public housing, but also limiting the debt that can be placed on them, thereby limiting HPHA’s ability to finance capital improvement or redevelopment.

Additionally, as Federal resources for public housing continue to come under pressure due to declining appropriations and insufficient subsidies, the operating resources required to effectively manage and maintain existing Federally subsidized housing have come under increasing pressure, resulting in an urgent need to preserve existing low-income housing stock and to ensure that it is managed efficiently for the long term.

These challenges, combined with the acute shortage of affordable housing in Hawaii generally, compel HPHA to embrace innovative approaches to redevelop, preserve and manage affordable housing that is sustainable and cost-effective, while also guaranteeing the best possible living situation for residents.

To achieve this, the formation of public and private partnerships that can maximize the leverage of both public and private capital resources is desperately required. HUD encourages this approach through programs such as Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) and Mixed-Finance strategies, that remove HUD’s declaration of trust, replacing it with a use agreement that is much more user-friendly in the private sector, better positioning HPHA properties to access the private capital and financing necessary to revitalize and maintain these communities.

Pursuing such strategies with HPHA-managed and/or state owned properties located along the light rail corridor, creates an exceptional opportunity for the state to maximize the value of existing, obsolete public housing communities by transforming them into higher-density, mixed-use projects by leveraging both TOD incentives and efficient financing through public/private partnerships.

HPHA has identified nine properties that could immediately benefit from this approach whose redevelopment could also expand the inventory of critically needed affordable housing units on O‘ahu.

BACKGROUND

28 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

1 2 3 4 5 7 6 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 A B C D F G H I E PUUWAI MOMI 99-132 Kohomua Street Acres: 11.54 Current Dwelling Units 260 (23 D.U/A) Proposed Dwelling Units 1,500 (130 D.U/A) HALE LAULIMA 1184 Waimano Home Road Acres: 3.96 Current Dwelling Units 36 (9 D.U/A) Proposed Dwelling Units 1,000 (256 D.U/A) KAMALU HOOLULU ELDERLY HOUSING 94-943 & 94-941 Kauolu Pl Acres: 4 Current Dwelling Units 221 (55.25 D.U/A) Proposed Dwelling Units 1,000 (250 D.U/A) A B C KPT PHASE 2 1430 & 1449 Ahonui Street Acres: 9.78 Current Dwelling Units 174 (18 D.U/A) Proposed Dwelling Units 425 (43 D.U/A) KAMEHAMEHA HOMES & KAAHUMANU HOMES 1629 Haka Drive & 760 Mcneill Street Acres: 23.37 Current Dwelling Units 373 (16 D.U/A) Proposed Dwelling Units 2,500 (107 D.U/A) SCHOOL STREET PROJECT 1671 Ahiahi Place Acres: 12 Current Dwelling Units 0 (0 D.U/A) Proposed Dwelling Units 800 (67 D.U/A) D E F MAYOR WRIGHT HOMES 521 North Kukui Street Acres: 14.85 Current Dwelling Units 364 (25 D.U/A) Proposed Dwelling Units 2,448 (165 D.U/A) KALANIHUIA HOMES 1220 Aala Street Acres: 1.89 Current Dwelling Units 151 (80 D.U/A) Proposed Dwelling Units 500 (265 D.U/A) KALAKAUA HOMES, MAKUA ALII, PAOAKALANI 1541, 1545, 1583 Kalakaua Avenue Acres: 9.15 Current Dwelling Units 583 (64 D.U/A) Proposed Dwelling Units 1,000 (109 D.U/A) G H I * * * Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA 29

Three key projects are currently being planned for redevelopment in proximity to the Kalihi-Kapālama-Iwilei stations.

KPT PHASE 2 (D)

An existing site that currently houses 174 public housing units. The project will add 251 new units; resulting in a rehabilitated community totaling approximately 425 new, mixedincome residential homes. The project will revitalize, modernize and increase the existing housing stock available at the site while improving the quality of life and encouraging a sense of community within the Kuhio Park neighborhood and among its families, residents and stakeholders.

SCHOOL STREET (F)

A six-acre site that currently houses HPHA’s existing, inefficient and outdated administrative office and maintenance facilities. The project will consolidate HPHA’s existing 13-building administrative campus into a single, efficiently designed, 30,000 square foot office building, occupying a significantly smaller footprint on the existing site. The balance of the remaining land will be more effectively utilized to develop a new, mixed-use project containing 800, age-restricted, affordable housing units.

30 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

MAYOR WRIGHT HOMES (G)

An existing mixed-income and mixed-use housing development. The proposed project will total approximately 2,448 residential rental units; including the replacement of the existing 364 public housing units on site, on a one-for-one basis with similarly deeply subsidized units. The majority of the remaining units shall be affordable units. In addition, up to 80,000 square feet of commercial space is also proposed for the project, which may include a mix of retail, office space, and community services to support the new residential units and complement the surrounding neighborhood.

31

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA

32 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

BACKGROUND

Takeaways

1. Programs such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) allow PHA’s to leverage existing assets to redefine their role beyond administration and management of public housing. Opportunities exist to improve and reinvest in housing through mixed-finance, mixed-income developments.

2. With access to existing housing properties and other state-owned lands, which represent a large percentage of sites near the new HART light rail stations in Honolulu, the HPHA is in the unique position to make a significant contribution towards helping solve Hawai‘i’s housing problem through redevelopment of existing properties.

3. The development or redevelopment of housing properties offers an opportunity to re-examine existing urban fabric and density. Determining the right amount of dwelling units per site to help meet the demand of units needed while maintaining good quality of life will be critical in this process.

4. A comparison of the existing and proposed Dwelling Units per Acre on the identified sites suggest the planned redevelopments would provide more than double the number of dwelling units by increasing an average of four times the density. Existing density ranging from 0 to 80 Dwelling Units per Acre would increase to approximately 67 to 265 Dwelling Units per Acre.

33

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA

University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority 34

Research Thirty In-Home Family Interviews 36 Research Analysis 40 Thirty-Six Design Actions & Opportunities 46 Twelve Design Strategies 52 Key Findings 54

Part II: Foundational User

35

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA

Ni‘ihau

Kaua‘i

Eleele Homes

Kawailehua

Kalihi Valley Homes

Hookipa Kahaluu

Kauhale O’hana

Palolo Valley Homes

Maili I

Kaahumanu Homes

Makamae

Puuwai Momi

Kalakaua Homes

Kahale Mua

Lāna‘i

Piilani Homes

Kahekili Terrace

Kaho‘olawe

Lanakila Homes

Hawai‘i Maui Moloka‘i O‘ahu

36 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

Thirty In-home Family Interviews

This study began by assessing the spatial needs of the most vulnerable population currently living in public housing in Hawai‘i.

Our team conducted thirty in-home interviews at seventeen properties owned/ managed by HPHA in partnership with ethnography and digital strategy expert Rebecca Buck. Housing structures were located in a variety of sites ranging from rural to urban on five islands, including Kaua‘i, O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, Maui, and Hawai‘i.

Families were recruited through invitations and introductions made by individual Property Managers via email, phone calls, and hand-delivered letters. The opt-in process, coordinated directly by the UHCDC team after initial introductions, resulted in a varied cross-section of residents that included single parents, senior citizens living alone, heads of households that faced a spectrum of mobility and healthcare issues, grandparents raising their grandchildren, lifelong residents, and new residents alike. No translators were required by final interviewees, but there were family members present for interviews that did translate portions of the conversations for their family. While the majority of interviews took place on O‘ahu, 35% of the properties visited were on the outer islands.

A discussion guide organized by scales of engagement and revolving around residents’ use of space and preferences, in general, guided the conversations. Residents spoke candidly about their life in public housing, describing both tangible and intangible characteristics of place. They voiced challenges and desires, and offered memories and hopes for their future.

Conversations with residents also explored current realities and future aspirations for family life, career trajectory, education, community engagement, environmental stewardship, and long-term housing plans. A final walk-through aided in documenting spatial settings and preferences. Interviews ended with the open question: “What does home means to you?”

Inquiries were focused on spatial attributes, programmatic or operational aspects and other non-human subjects. It must be noted this part of the research did not request identifiable private information or information regarding individuals and their thoughts about themselves.

FOUNDATIONAL USER RESEARCH

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by

Sierralta, AIA and

Strawn, AIA 37

(Left) Diagram of selected properties owned/managed by HPHA in Hawai‘i.

Karla

Brian

Discussion Guide

The discussion guide shown on this page was not intended to be read verbatim but was instead to serve as a framework for our conversations.

Note-Taking

A series of prompts for taking notes with sample tags (#) for data input.

Community notes

Notetakers listen for:

What local amenities do they use most frequently? (eg. grocery store, pharmacy, school, university, church, employer).

How do they define the boundary of where community?

What transportation methods do you use to get around?

(Bus, car, Zipcar, informal car share, bike, walk?)

#Subject tags in Validately:

#community

#transportation

Prompts

Organized by scale, with possible follow-up questions.

Community 10 min

Website redesign 10 min

Tell us about living in this community.

20. As of June 19, 2019, Validately was acquired by UserZoom (https://www. userzoom.com/).

How long have you lived in this community?

How would you compare it to other communities you’ve live in?

What places do you go most often?

In addition to designing future apartment buildings, we also have an opportunity to redesign the HPHA website. That could include everything from learning about and applying for programs, to paying rent, or even other digital services. We have a few questions that could help us understand what to improve. But, we don’t need to know anything about your finances, and if anything feels too personal, or your not sure how to answer, it’s okay to not to any any questions.

- Where do you get groceries?

How did you find out about HPHA programs?

Where do you go for fun?

If you work, is that near by?

Do you remember going to the website?

First impressions?

How do you get places you need to go?

Did you find the information you needed?

Dive? Walk? Bus?

How did you know if or what you’d qualify for?

- Did you apply there on line?

Do you have friends or family in this community?

- Do you know any neighbors by name?

How much time passed between you applying and then getting an apartment?

Are there any amenities do you need nearby that are not currently here?

How did you know what to expect?

What is your favorite thing about your neighborhood?

What would you change about the neighborhood?

Process would be? - How long to expect to wait? - What building or apartment you’d be in? - How the move in process would go?

What the are the building policies? (Paint? Hang things on the walls?)

How to pay rent?

How does this system for paying you rent work today?

Pay by check?

- On line?

Ideally, how should that system of work?

Conversations were recorded and documented while maintaining privacy and anonymity. Qualitative data was collected using Validately20, an online digital ethnography tool that allowed both on-site and remote team participation.

Each 90-minute conversation was structured as follows:

- Introduction (10 min)

- Community (10 min)

- Buildings (10 min)

- Unit (40 min)

- Other (10 min)

- Wrap-up (10 min)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

38 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

Summary notes

Community

Listen for:

Building 10 min

Summary 10 min

Listen for: A quote about what home means to them.

What makes a building desirable?

What amenities are most important to them?

What design elements or affordances make each type of building space useful?

#TAGS in Validately: #HomeQuote #FutureGoals

#TAGS in Validately: #building #amenitites

Tell us about living in this in this building.

How would you describe what “home” means to you?

How did you come to live here?

We’re almost done…

What spaces around the building do you use most often?

Tell us about some of your hopes for the future?

- Laundry?

- Are there any personal goals that you're working towards?

- Shared community spaces?

- Listen for: physical health, financial health, social goals, skills or hobbies.

- Outside space?

- Parking?

What are some hopes that you have for your family in the next 2-5 years?

- Storage?

For each space:

How about hopes for your career?

- How would you describe success in your job or career?

- What makes that space helpful?

- Are you planning on skills training to get the job you really went?

- What could be better about that space?

- For your education?

- Anything preventing you from using it?

- For your home?

- For Hawaii? (if no answer, make it smaller and ask about their community).

What do you like best about living in this building?

Is there anything about the building you wish you could change?

Thank them and pack up.

What would you look for in an ideal building?

ACTIVITY: #AmenitiesCardSort

Apartment / Unit Notes Apartment / Unit

Listen for: What makes a unit desirable?

What amenities are most important to them?

What changes do people want to make when the move in?

#TAGS in Validately: #unit

40 min

Tell us about living in this in this apartment.

What is you favorite thing about your home?

When you first moved in, was there anything you changed or added to make it feel like home?

When you first moved in, was there anything you wished you could change?

How would you compare this apartment to other places you’ve lived before?

ACTIVITY: #HomeTimeline

ACTIVITY: #HomeTour

#AmenitiesCardSort notes Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA 39

Observations Insights How might we... Design Opportunities 40 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

Research Analysis

Over thirty hours of recordings were tagged and analyzed, generating thousands of data points. Hashtags were utilized to sort information.

The following words/phrases offer a glimpse of the topics that were discussed:

Community #community

#transportation

#futuregrowth

#playground

#walkability

#programs

#healthycitizens

Building #building

#amenities

#management

#lighting

#safety

#proximity

#trash

#activities

#garden

#lighting

#maintenance

#sitelayout

#repairs

Unit #unit

#disability #storage

#flooring

#bathroom

#ventilation

#laundry

#unittypes

Other #whatahomemeans

#kids

#journeymap

#technology

#rentpayment

#hometour

#persona

#offboarding

#safetynet

Observations varied from hyper specific to broad aspects of inhabitation. For example:

- Residents long for flexibility in their home so they are able to adapt to changing needs and reduce hassle when moving.

- Residents enjoy talking with and spending time with neighbors, and feel the more they know each other the more respect they have for one another.

- Residents are willing to work in a community garden and share what they produce with others in need.

- Residents are vulnerable because they are living paycheck to paycheck. Any emergency situation could deplete savings and result in eviction.

These observations lead to insights, which were ultimately translated into design opportunities.

FOUNDATIONAL USER RESEARCH

(Left) Observations to Design Opportunities Research Analysis diagram

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA 41

Representative Statements and Shared Resident Needs

The scales of community, building, and unit were used as an initial filter for organizing quotes and observations, revealing a rough outline of emerging themes. The representative statements on this page were paraphrased because their sentiment was heard, in one form

or another, across multiple interviews. The “why” of each example is supported by summary resident profiles and their individual reasoning, revealing how a single need can be shared across a multiplicity of household types.

Community Building

What we really need is a place for kids to play. The park they play in is not on our property so we have no control over it.

• Single parent - Living at a property where the on site playground is closed, forcing the kids to go to another park where they can't be seen.

• Senior citizens - Had raised their children on a property with access to a playground and they felt bad for families raising kids without access to an on site play area.

It was perfect, everything was in walking distance.

• Senior citizen, living alone - Raised their family at Mayor Wright and now lives in studio apartment in a senior building with no walkable amenities, like a pharmacy or grocery store, nearby.

• Senior citizen, living alone - Entered public housing after raising a family. The first property they were at had nothing nearby and they don't drive, isolating them. The property they now live at has multiple community amenities within a close walking distance.

I wouldn’t want to live in a high rise.

• Senior citizen - Previously lived at a property where the elevator was broken for long periods of time and had difficulty with taking the stairs.

• Family with children - Wanted their kids to be able to access the outdoors at the unit. They have never lived in a building that has access to a secure amenity deck with play areas.

We could use another laundry room.

• Senior citizen with mobility issuesRegarding the difficulty they have carrying laundry to the far side of the property.

• Single parent - Not wanting to leave the child alone or take child with them on the elevator multiple times.

• Handicapped head of household - Spouse has to leave them and their child unattended while doing laundry.

42 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

Cross ventilation is important. Need to move the breeze through the house and keep it cooler.

• Senior citizen, living alone -Previously lived at Mayor Wright with great cross ventilation and now lives in a studio in a senior building with little cross ventilation and no air conditioner.

• Family with children - The cross ventilation in their living room is blocked by a partial height wall, making it uncomfortable in the summer. This results in the family sitting in the parking lot area right in front of their unit.

Built in storage is great. It makes moving easier when you need to change units.

• Senior citizens, living with adult childRetired couple's son and his child are about to move out and they are being shifted into a smaller unit. They are glad they have less big pieces of furniture to move because both spaces have built-ins.

• Single Parent - Has moved between properties and built-ins have allowed them to do this alone, making the process a bit less painful.

Taking time to go to the bank to pay the rent is a burden while raising children and working.

• Single parent/part-time college studentFinding time to drop the paper-based rent slip is an inconvenient and they would prefer to pay it through their phone.

• Single Parent - Working full-time and living in a rural area makes going to the bank difficult during the week and eats up time on the weekend when time could be spent with kids.

It can take a long time to get something repaired.

• Single parent - Likes the jalousie windows in their unit because of the air control, but when the louvers or the cranks break the process of getting them fixed can take a lot of time to coordinate.

• Family with children - Kitchen cabinet hinge got broken and they have been waiting several months for a repair. Waiting for this repair and their upcoming unit inspection was a source of stress for the family.

Unit Other

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing |

AIA

Strawn, AIA 43

Selected photographs during the interview process.

by Karla Sierralta,

and Brian

In-Process: Research Analysis Example

The interviews and home tours resulted in thousands of data points. These include resident statements and visual observations made by the research team, both those inperson and those at UH remotely monitoring the interviews online. Several rounds of affinity

clustering, organizing data points into meaningful categories, took place by manually sorting handwritten Post-It notes and with digital spreadsheets. Below is a representative example of how data was processed from a set of discrete observations into more universally

Insights Observations

A resident wished that the lānai space was bigger so she could spend time there with her daughter.

The outdoor space is big, benches and tables should be available to enjoy the sun.

Residents believed that if they had lived in a regular house, they wouldn’t know their neighbors.

Anybody can just walk past their windows. They felt it would be better if each unit had their own yard to increase privacy.

A resident feels that home is a place that is safe, a place they love, a place with nice neighbors.

Once a year the community would have a ho’olaulea, where different nationalities would participate, and all of the people in the housing would get to know each other.

It would be helpful for residents if there was a space the for the neighborhood board to meet.

Monthly meetings are very important, so people know what is going on in the project and why.

Individual lānais provide residents with the opportunity to connect with friends and family, as well as connect to the surrounding public space (at a comfortable distance).

Large and open communal spaces can be made more inviting by adding benches, tables, and a grill area, creating a flexible and structured environment for neighbors to interact.

A meeting and celebration space for large family gatherings, community celebrations, and neighborhood board meetings will promote social interaction between family, friends and neighbors.

44 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

applicable Insights, to generative “How might we” statements, and into Design Opportunities that are precursors to the design framework that future agents could utilize to design environments for residents.

How Might We's... Design Opportunities (Draft)

How might we provide residents with outdoor space that is private, yet connects to the surrounding public space?

Provide units with lānais that have visual access to surrounding communal spaces.

How might we enhance social connections in large communal spaces?

Offer programed furniture in community spaces that support multiple functions/activities such as picnics.

How might we promote social interaction between family, friends and neighbors?

Provide each building with a range of multi-functional communal spaces.

Selected photographs during research analysis.

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA 45

Thirty-Six Design Actions & Opportunities

Affinity clustering exercises were used to process and clarify the emerging framework.

This section presents the thirty-six design opportunities that were generated from the research.

FOUNDATIONAL USER RESEARCH

46 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

TABLE 1: List Summary of Design Actions and Opportunities

Generous shared spaces and common amenities support comfortable co-living and multi-generational households. Plan for multiple entryways, cooking zones, bedrooms, and bathrooms to allow for privacy and independence or to accommodate isolation needs.

Open floor plans and movable elements allow residents to organize their spaces to accommodate changing needs. Spaces should be designed to host multiple functions, allow alternative sleeping arrangements, or acoustical separations.

Adjustable, built-in elements make moving easy and provide a more flexible living space within compact footprints. Consider a variety of storage and built-in options such as closets, nooks, hanging shelves, and Murphy beds, as well as expanded entryways that can accommodate slippers, packages, and decontamination routines.

A variety of spaces can enrich neighborly relations and allow for improvised and dynamic conversations. Include shared spaces at both the scales of building and block. Consider outdoor scenarios, such as common lanais, porches, and other sitting or playing areas.

Social platforms keep neighbors updated on current issues, community events, and resource availability. Provide digital opportunities for sharing real-time information about daily activities within buildings and neighborhoods.

While maintaining privacy, direct sightlines onto common spaces, and access points improve the sense of security. Configure buildings and units to allow for uninterrupted views to the street and other public or semi-public areas.

The possibility of living, working, and playing within the same community increases productivity and reduces long commute times. Avoid isolating residential uses from other functions of the city. Plan a blend of small businesses, live-work opportunities, and other resources within walking distance.

1 Enable co- and multi-generational living 2 Propose adaptable spaces 3 Offer smart storage 4 Facilitate friendly interactions 5 Sync-up the community 6 Open sight lines 7 Promote hybrid neighborhoods DESIGN ACTIONS

DESIGN OPPORTUNITIES

Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing |

AIA 47

by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn,

Access to outdoor public spaces connects residents to nature, provides opportunities for social interaction, and improves physical and mental health. Reclaim under utilized spaces within every neighborhood for public parks, plazas, and gardens of all types.

Civic spaces serve the community and provide a forum for celebrations, traditions, culture, freedom of speech, and other public events. Plan indoor and outdoor civic spaces that are approachable to all and can accommodate multiple uses, including emergency pop-ups.

Neighborhoods scaled to human dimensions create comfortable and inviting spaces. Carefully plan building proportions, street-width to building-height ratios, shading, vegetation, and ground floor functions, including small businesses, to contribute to a pleasant urban experience.

Streets designed with pedestrians and cyclists in mind provide safe, active spaces for moving and socializing. Prioritize pedestrians and cyclists. Increase safe opportunities for moving on foot that encourage mobility and promote healthy lifestyles.

A network of transportation options such as bus, rail, bike, and rideshare increases connectivity. Plan for safe, multimodal transportation services and spaces, where hubs serve as catalysts for public life.

Designs that integrate natural cycles for water regeneration throughout buildings and sites minimize environmental impacts and increase resiliency. Consider sustainable water inputs and outputs, as well as climate-related vulnerabilities while planning new developments or redesigning existing communities.

Site, building, and unit layouts that take advantage of cross breezes naturally cool interior spaces. Avoid climate-controlled inner hallways and provide cross ventilation for all spaces.

The building’s position and its materials or components contribute to the design of comfortable spaces and energy consumption/generation. Orient buildings to minimize heat gain, provide shade, and maximize solar power generation or other sun benefits.

8 Weave in parks and plazas 9 Blend civic spaces into daily life 10 Respect human scale 11 Democratize the street 12 Amplify community mobility 13 Foster water consciousness 14 Leverage cross breezes 15 Mind the sun

DESIGN ACTIONS DESIGN OPPORTUNITIES 48 University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center for the Hawai‘i Public Housing Authority

Gardens allow residents to grow and share the food they produce and foster community interaction. Provide spaces for growing at all scales, including homes and neighborhoods, such as planting beds, greenhouses, community gardens, and orchards.

Reducing, reusing, and recycling minimize waste and extend the life of existing products and buildings. Design for known material flows, provide adequate space for waste collection, separation, and management, including opportunities for composting, and support adaptable reuse projects.

Learning opportunities allow residents to remain active and connected to their communities as life circumstances change. Consider spaces that can facilitate these activities such as classrooms or maker spaces and support lessons or training programs that allow residents to teach or learn from each other.

Easy and accessible opportunities to exercise outdoors promote health and wellbeing. Design spaces that allow residents to play, walk, run, and bike within walking distance of their homes.

Outdoor living is an integral part of Hawai‘i’s culture. Units with lānais provide residents with indoor/ outdoor experiences, views, and fresh air. Consider outdoor spaces as essential for all residents.

Balconies are spaces in between private and public realms, offering views of the sky or surroundings, but where residents still feel a need for privacy. Consider physical and acoustical boundaries between spaces and units such as privacy walls, sunshades, planters, or trellises that allow privacy while maintaining views.

Materials sourced regionally and locally decrease construction costs and carbon emissions. Specify local, regional, and sustainably harvested materials. Re-imagine material logistics to reduce supply chains.

Carefully planned construction processes and locally appropriate building techniques provide easy, cost-effective construction and long term maintenance solutions. Rethink construction processes to reduce material costs and timelines.

16 Multiply productive lands 17 Redefine waste 18 Spark skill-sharing 19 Power active lifestyles 20 Provide lānais for all 21 Protect views and privacy 22 Source regional materials 23 Aim for efficiency

DESIGN ACTIONS DESIGN OPPORTUNITIES Future of Hawai‘i’s Housing | by Karla Sierralta, AIA and Brian Strawn, AIA 49

Design with local trades and labor in mind. Consider the prefabrication of building components off-site to save time and reduce waste.

Buildings designed with flexibility in mind facilitate adaptive reuse and serve communities longer. Plan for spaces, circulation and structural systems that are able to respond to future needs and uses.

Alternative systems such as rent-based investment, enable ownership opportunities for more citizens. Provide alternative paths towards owning.

Residents might need help keeping a roof over their head in moments of crisis. To prevent homelessness, create programs that offer just-in-time financial assistance programs in critical moments of need.