Urban Planning & Design Portfolio

JUNE 2023

JUNE 2023

INTRODUCTION

Pg. 4-5

THE STREETCAR SUBURB

Pg. 6-9

CINCINNATI’S WEST END: LAUREL HOMES

Pg. 10-11

ENGLISH WOODS SITE DESIGN PROJECT

Pg. 12-15

HAMILTON TOWNSHIP TOWNE CENTER

Pg. 16-17

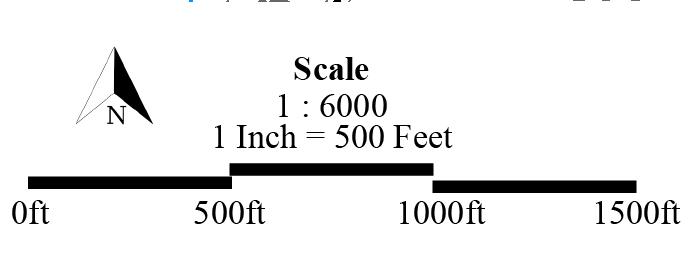

CAMP WASHINGTON NEIGHBORHOOD ANALYSIS

Pg. 18-23

CENTRAL MILL CREEK VALLEY ACCESS PLAN

Pg. 24-27

REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT

Pg. 28-29

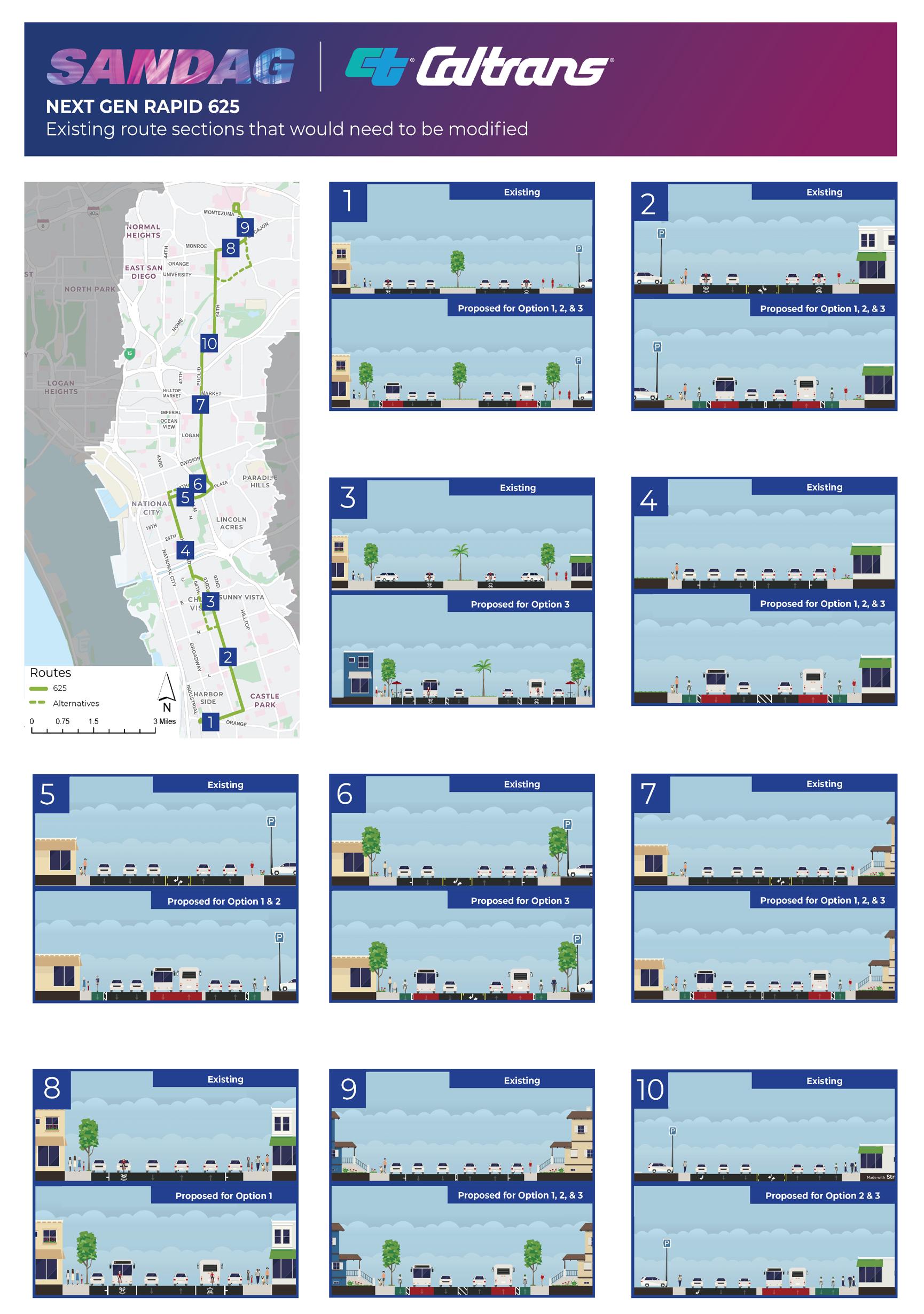

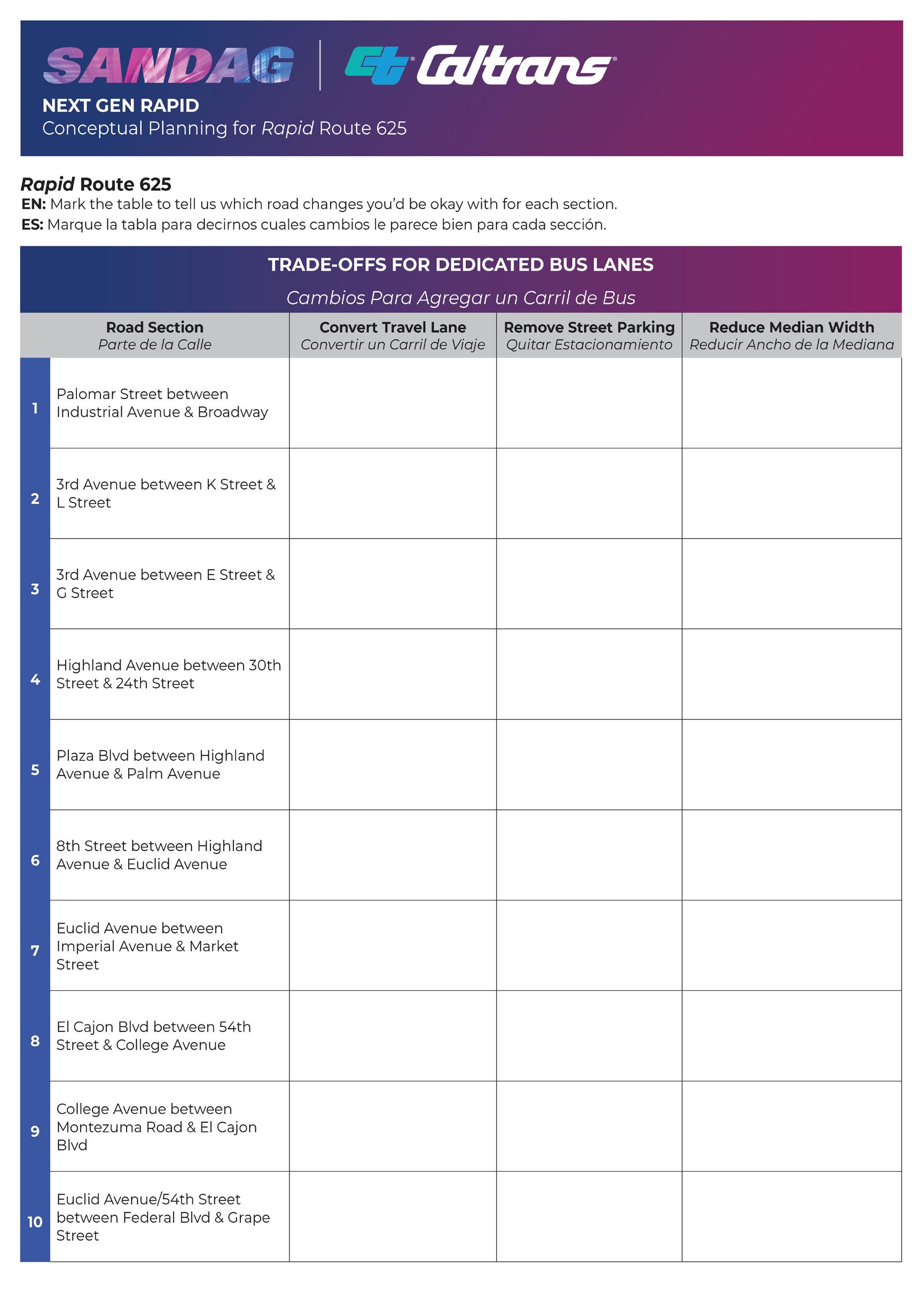

NEXT GEN BRT PUBLIC OUTREACH BOARDS

Pg. 30-33

M/I HOMES ENTRY MONUMENT INVENTORY

Pg. 34-35

WRITING SAMPLES

Pg. 36-37

ADDITIONAL SKETCHUP & V-RAY RENDERINGS

Pg. 38-39

Hi, my name is Brandon Williams. I’m an Urban Planning student at the University of Cincinnati. I have always been inspired by cities, how they function and interact with their surrounding environments. There is something about each city that makes them unique or special, and as a planner I want to have a hand in embracing that uniqueness in today’s modern world.

Phone: (865) 360-3747

Email: branmattwill@gmail.com

Linkedin:https://www.linkedin.com/in/ brandon-williams-7a0a22198/

Interests

• Site Design

• Transportation

• Real Estate

• Preservation

• Recreational Spaces

• Community Dev.

• Graphic Design

My Favorite US Cities

• San Francisco, CA

• Savannah, GA

• Charleston, SC

• St. Augustine, FL

• Boston, MA

• Cincinnati, OH

• San Diego, CA

University of Cincinnati- College of Design, Architecture, Art, & Planning.

Bachelor of Urban Planning / Real Estate Minor (2019 - Present)

• 3.87 GPA

• National Co-op Ambassador

Work Experience

Transportation Planning Intern - HNTB, San Diego, California (May’22 - Apr’23)

Land Development Co-op - M/I Homes, Cincinnati Ohio (Aug’21 - Dec’21)

Econ Dev & Zoning Co-op - Hamilton Township, Maineville Ohio (Jan’21 - Apr’21)

Clubs & Leadership

College:

Operations Chair - DAAP Ambassadors (2022 - Present)

Secretary, Historian - Pi Kappa Phi Fraternity(2021 - 2022)

Co-Op Committee - DAAP Tribunal (2021)

High School:

Team Captain - High School Debate Team (2018 - 2019)

Vice President - High School Junior Class SGA (2017 - 2018)

Technical Skills

Adobe Illustrator

Adobe InDesign

Adobe Photoshop

Adobe Lightroom

ArcGIS Pro

SketchUp & V-ray

Microsoft Office

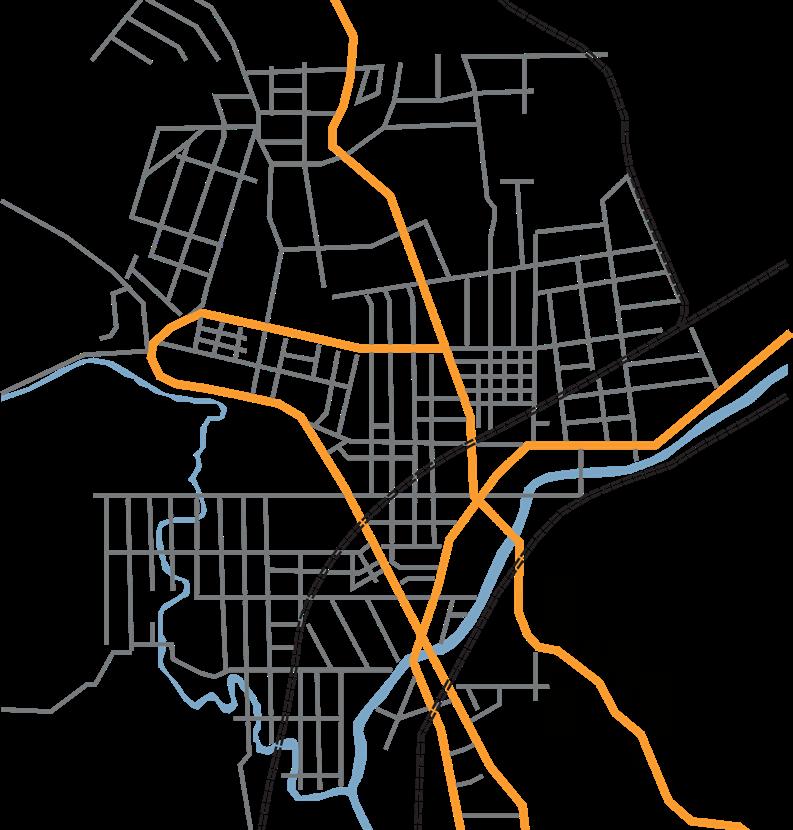

In the Fall of 2022, I conducted a historical study of the streetcar suburb of Cumminsville, a former neighborhood in Cincinnati, Ohio. Today, the area is known as Northside and South Cumminsville. The streetcar, once a dominate mode of transportation now an artifact in America’s largest metropolitan cities, is largely responsible for the growth of our oldest suburbs. Cumminsville is one of the many Cincinnati neighborhoods that benefited from the streetcar, originally founded as a small village six miles from Downtown. In the 1860s, the first streetcar began service to Cumminsville, followed by three other service lines over its 90-year history. By the 1950s, Cumminsville had become an integrated part of Cincinnati’s urban fabric.

The object of this analysis was to provide historical evidence and identify key symptoms of urbanization as a result of streetcar services. All maps shown to the right are tracings of original historical maps showing the growth of Cumminsville by street network, urban form, and streetcar service alignments.

Route 15 started downtown and went along Spring Grove Avenue in Camp Washington and then went through Cumminsville along that same road up to Chester Park. This was an amusement park close to Spring Grove Cemetery. It was also known as the Spring Grove Avenue Line.

Route 16 started downtown and went along Colerain Avenue in Camp Washington. It then looped in Cumminsville around Virginia and Chase avenues. It is also known as the Colerain Avenue Line.

Route 17 started downtown and went along Central Avenue, then through Cumminsville on Hamilton Avenue up to College Hill. It is also known as the College Hill-Main Street Line.

Route 61 started downtown and went to the University of Cincinnati, Clifton, and then into Cumminsville on Hamilton Avenue. It is also known as the Clifton Avenue-Cumminsville Line.

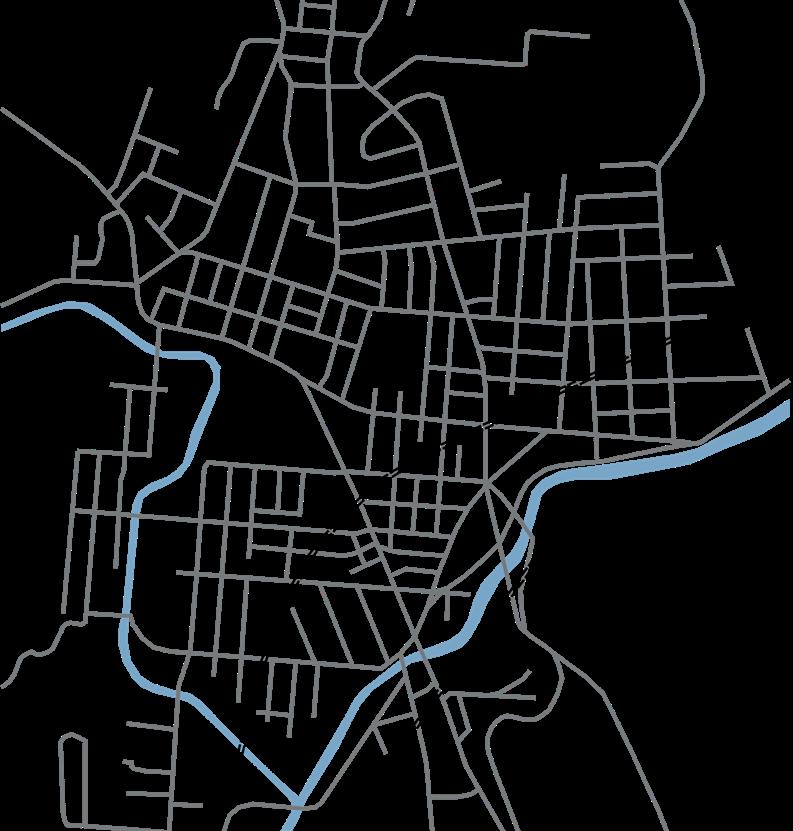

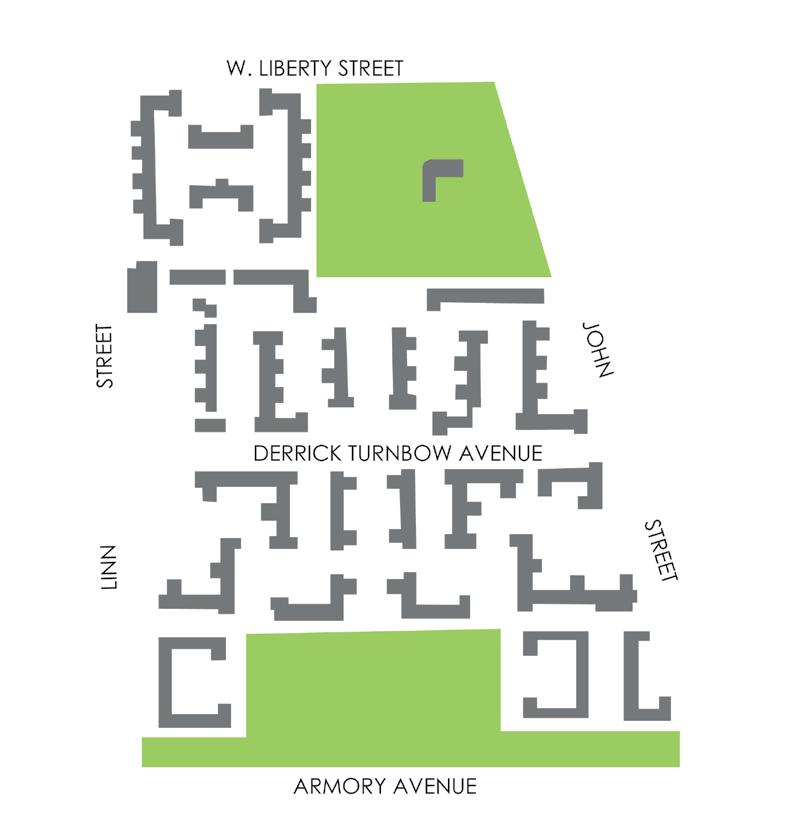

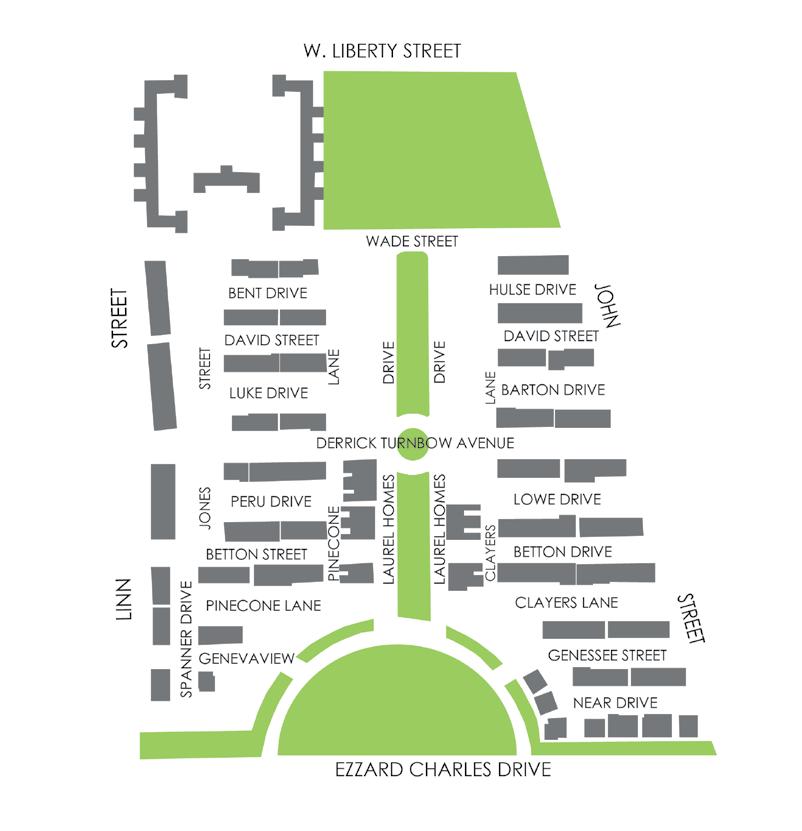

Also in the Fall of 2022, I conducted a historical study of Cincinnati’s West End neighborhood and how it bared the full brunt of urban renewal’s impacts via the construction of I-75. I primarily focused on a contiguous collection of blocks known as Laurel Homes, and its immediate surroundings. The study required an understanding of Cincinnati’s urban fabric, demographic history, the disruption caused by I-75, and the country’s urban form shift. I primarily focused on Cincinnati’s public housing efforts and the demographic to housing form shifts that took place on the collection of blocks.

This analysis aimed to identify acute symptoms of decentralization in urban form, provide a contextual history of Cincinnati’s public housing, and analyze the effects of urban renewal. Similar to the previous analysis, all maps shown to the right are tracings of original historical maps, showing the urban transformation of Cincinnati’s West End by visualizing the changes in the street network, urban form, and historical building footprints.

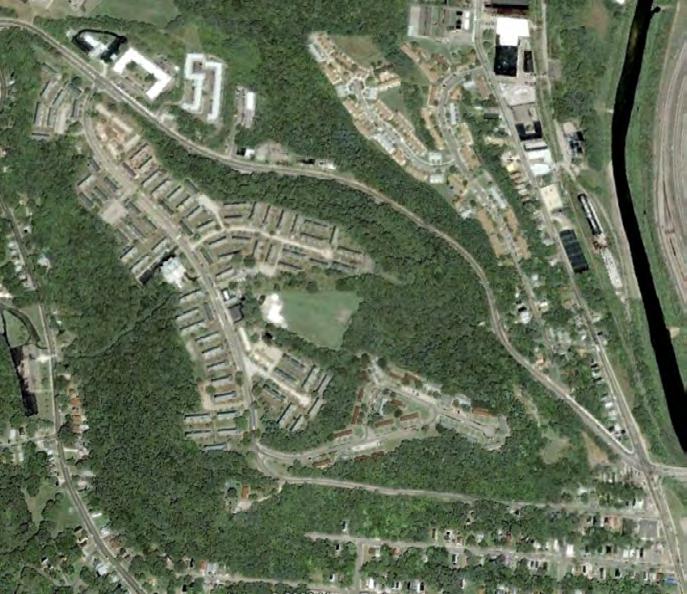

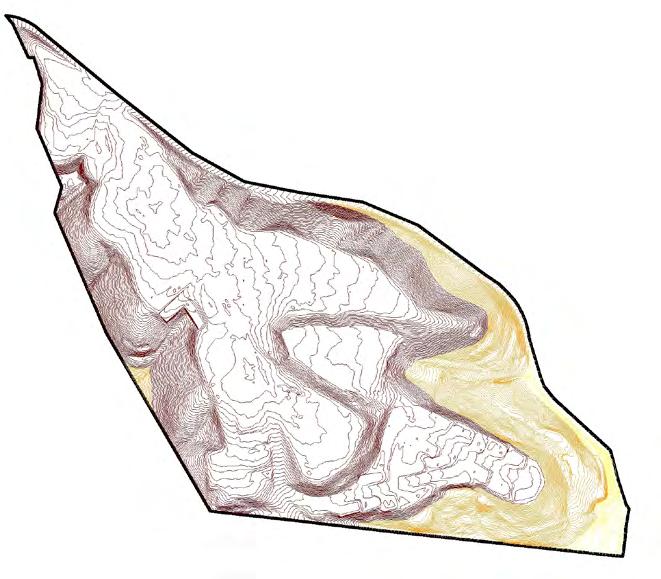

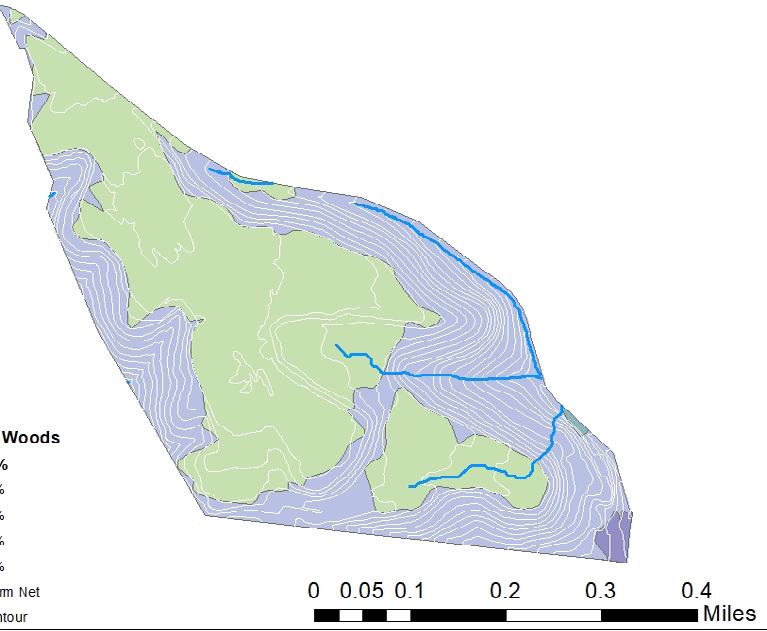

In the Fall of 2020, I studied, designed, and presented a site design plan for the largely vacant neighborhood of English Woods in Cincinnati, Ohio. The neighborhood was once a vibrant new community that featured public housing for returning soldiers from WWII, a community pool, recreation fields, and a small community market. In the 1960s, a senior care facility and more townhouses were added.

Over the years, these units deteriorated in quality and desperately needed proper maintenance. The neighborhood became known as a place to avoid as crime and vacancy flooded the area. Many of the units fell into such disrepair that in 2006, its property owner, Cincinnati Metropolitan Housing Authority, demolished all the units except for Sutter View and Marquette Manor which were both constructed in the 1960’s expansion. Today, the remaining units in Sutter View are under extensive renovation and Marquette Manor continues operations as a senior care facility. Before designing the site, I studied and wrote a brief existing conditions report that analyzed infrastructure, soil, climate, topology, historical imagery, and existing transit routes.

• Union Terminal: 18 mins

• Government Square: 29 mins

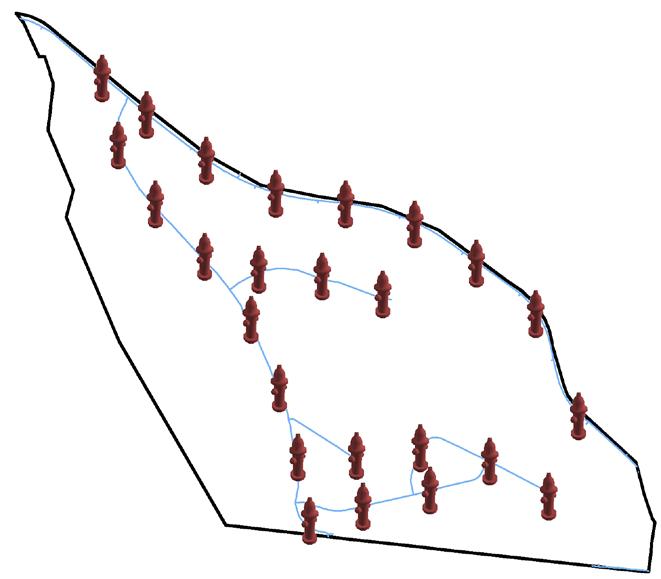

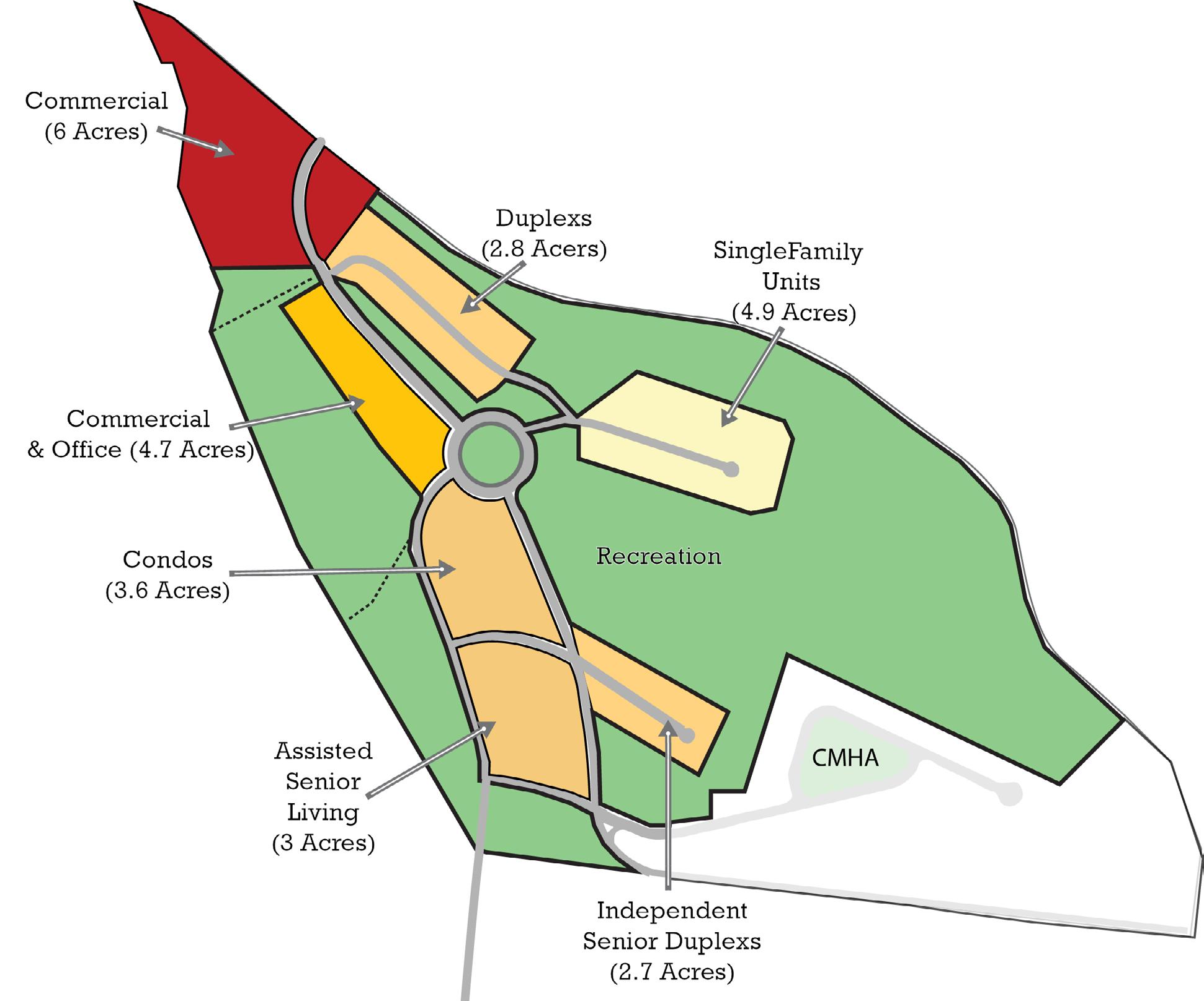

The land use plan below features many types of uses, including a diversity of housing densities, commercial, mixed-use, and ample recreational green spaces. This land use plan does not suggest any change in uses for the Sutter View CMHA development.

The site design plan above was made with the idea of creating a live, work, play community. The site would feature many recreational spaces such as a community recreation center, soccer field, pool, tennis courts, basketball courts, a trail network, and playground. Additionally, there is a diversity of housing types, senior care services, retail, medical offices, and a grocery. As part of the analysis, I did calculate FAR for all structures.

Hamilton Township is known in Warren County, Ohio for being a great place to raise a family and an escape from the bustling city of Cincinnati. The township has a population of about 30,000 residents and is near to regional attractions such as King’s Island and the Lindner Family Tennis Center. Having these assets in close proximity, the township feels confident that a new mixed -use commercial development would be successful.

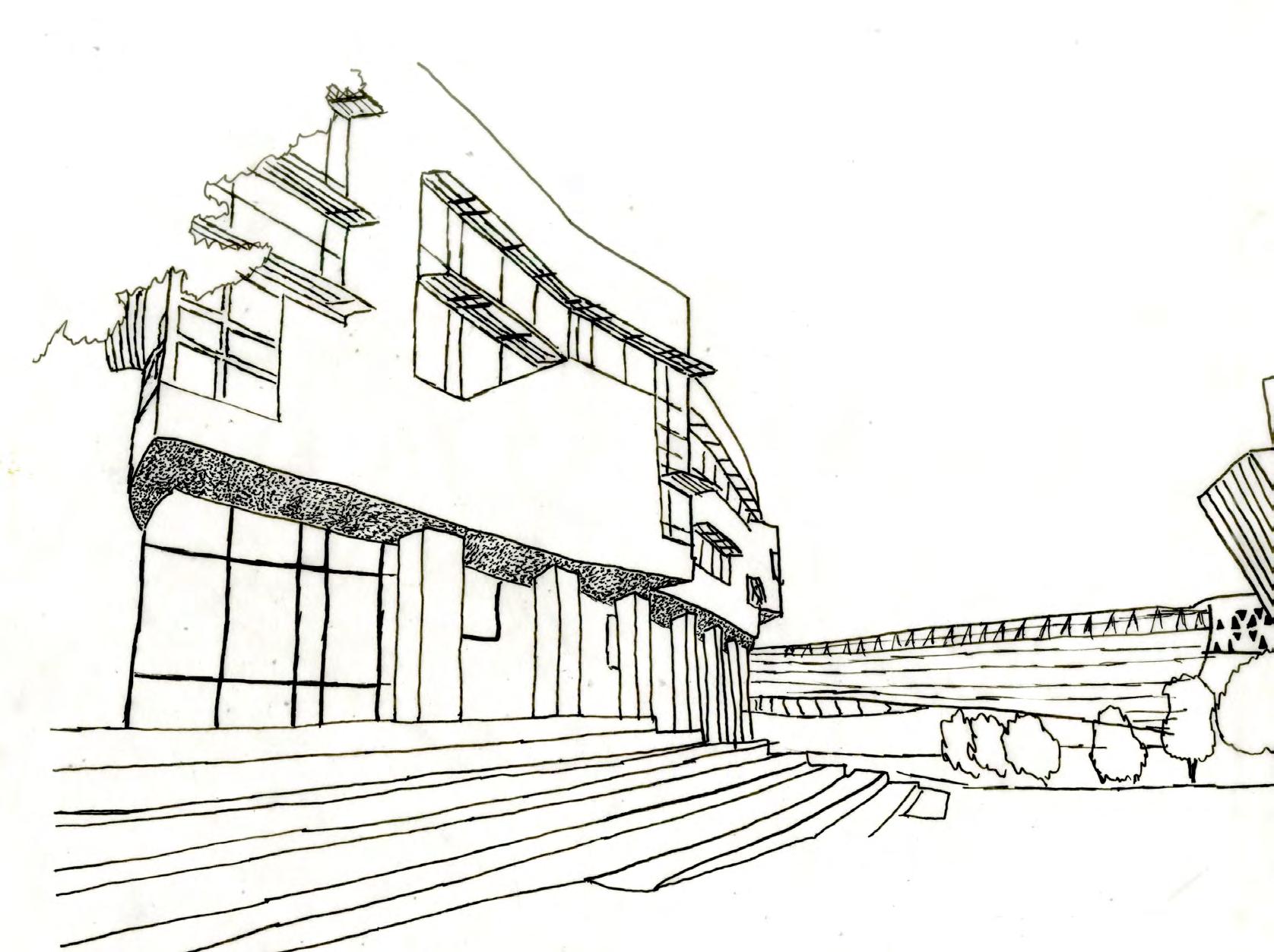

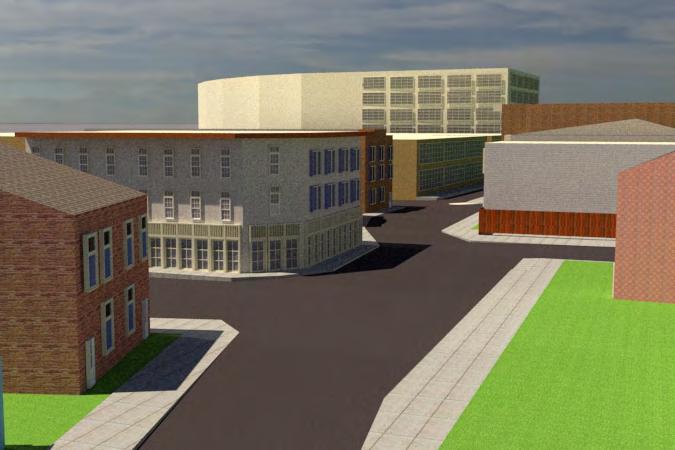

Upon starting my first co-op at Hamilton Township, I was tasked with helping visualize a potential site design for the township’s Towne Center project on a $600 budget. The design shown was the favorite of three variations. This design was determined based on a wishlist handed to me when I first started. The most compelling points on the wishlist were walkability and sense of place. As a result, this design calls for the implementation of a live, work, play community. The site would feature two main mixed-use multi-family buildings, amphitheater, beer garden, and a separate community of apartment buildings. Preferably, the township would like the Towne Center to be designed in American Colonial architectural style, paying homage to the underground railroad houses that once stood along the Little Miami River.

A. Big Box Store

B. Commercial Sleeve

C. Two Commercial lots (Banks or Restaurants)

D. Two Commercial lots (Restaurants)

E. Towne Center Apartments I (Mixed-use)

F. Towne Center Apartments II (Mixed-use)

G. Hidden Ground-level Parking

H. Amphitheater

I. Beer Garden

J. Apartment Complex

K. Community Clubhouse

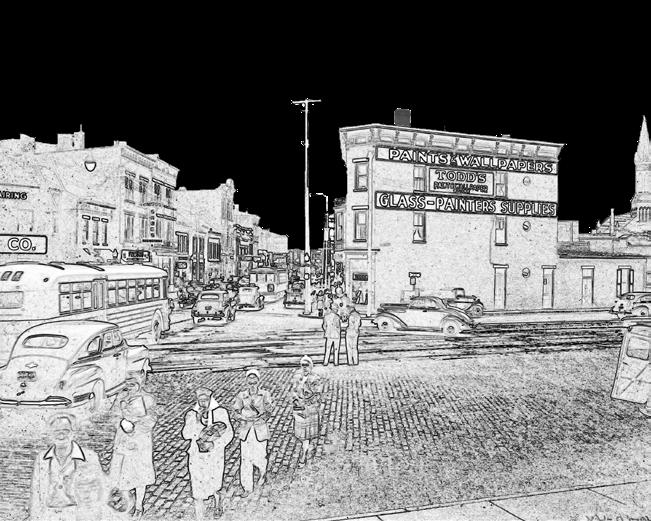

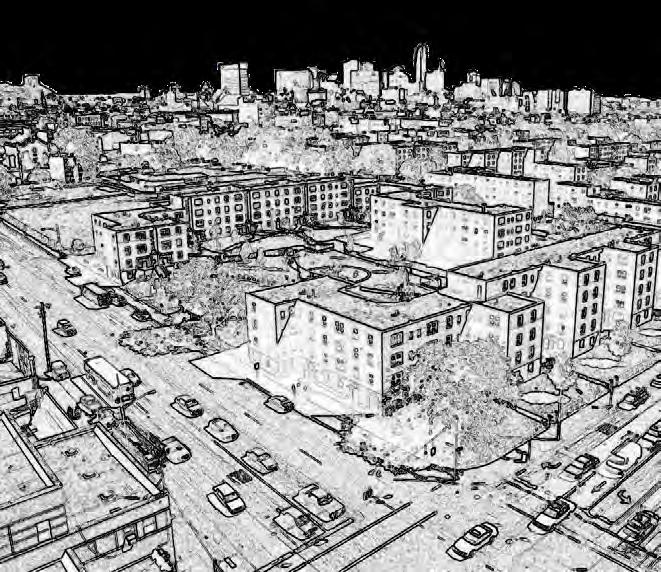

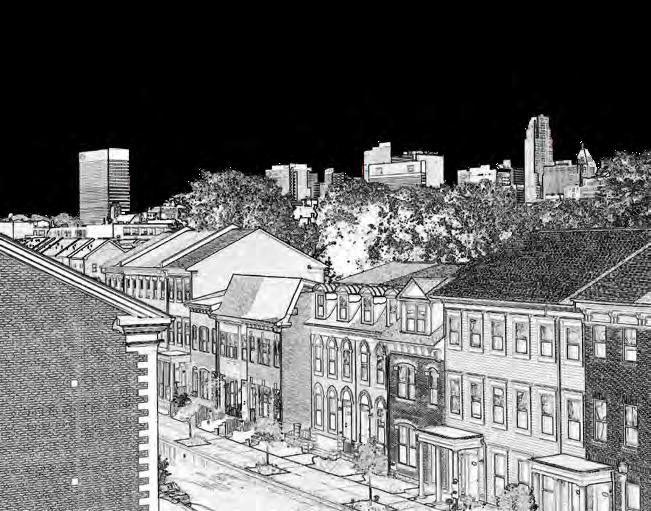

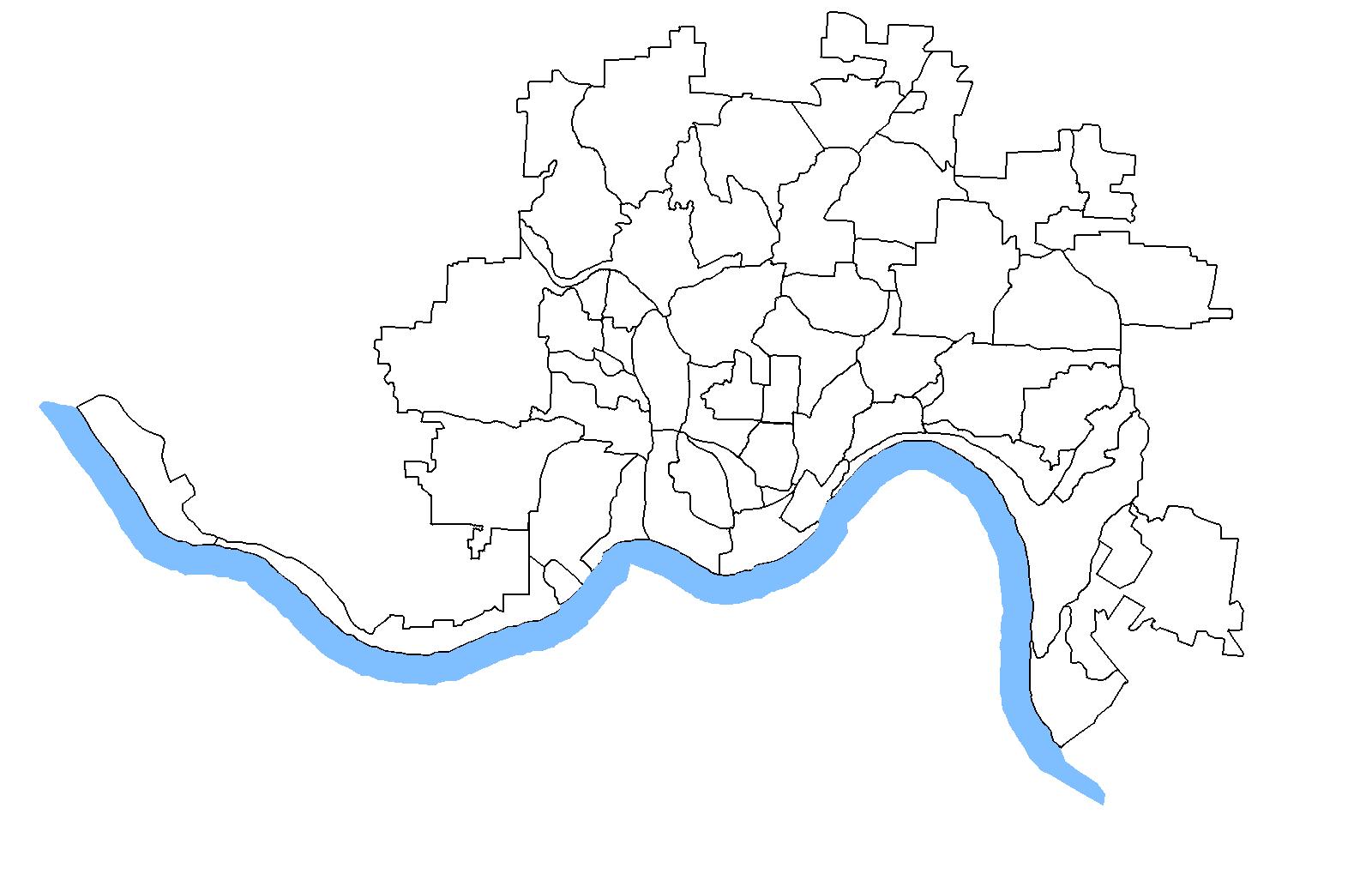

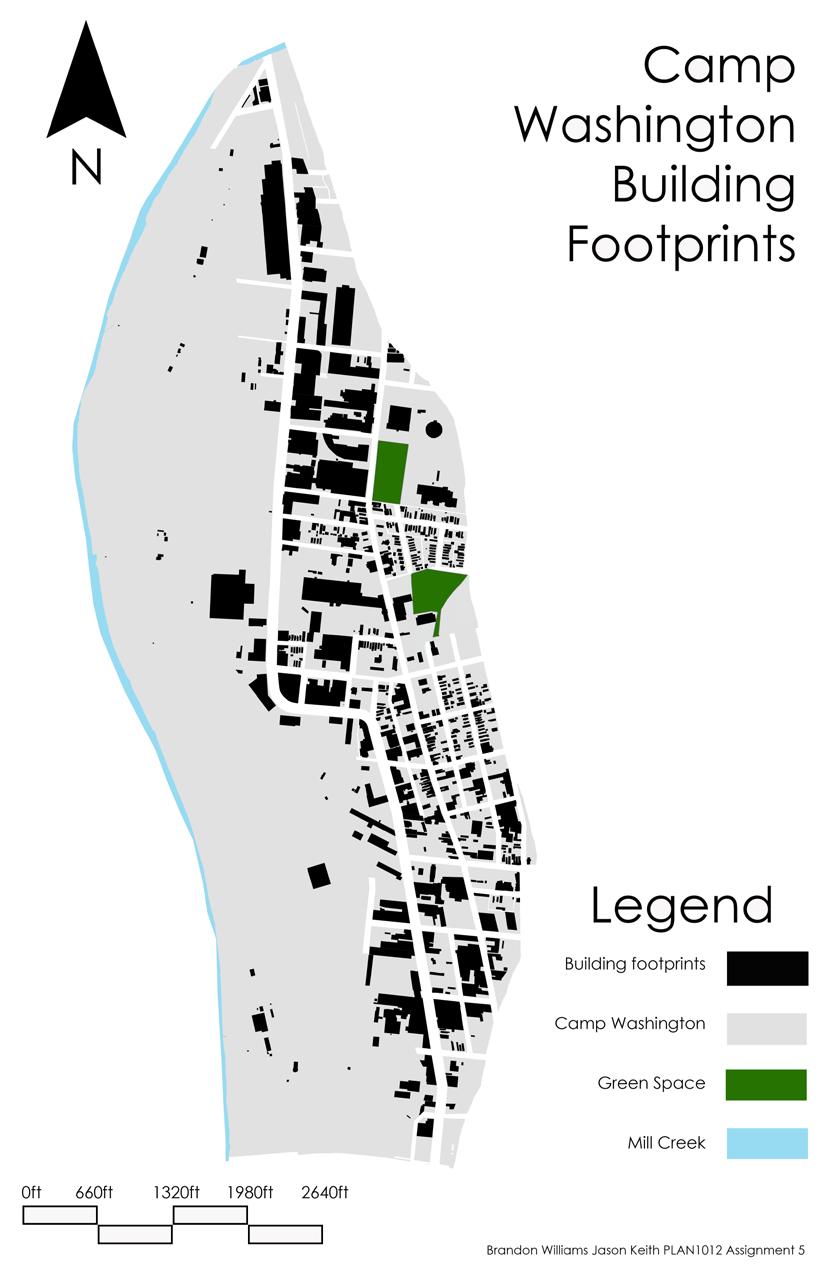

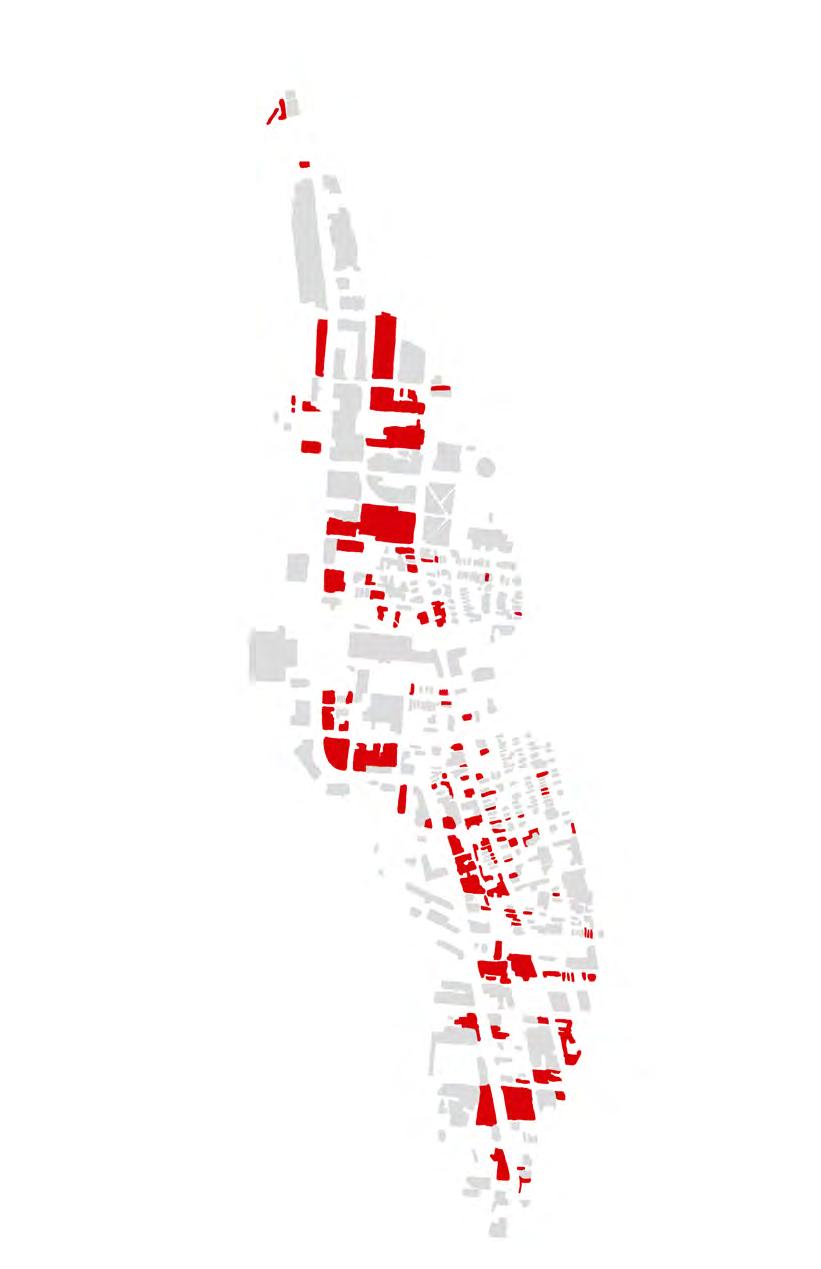

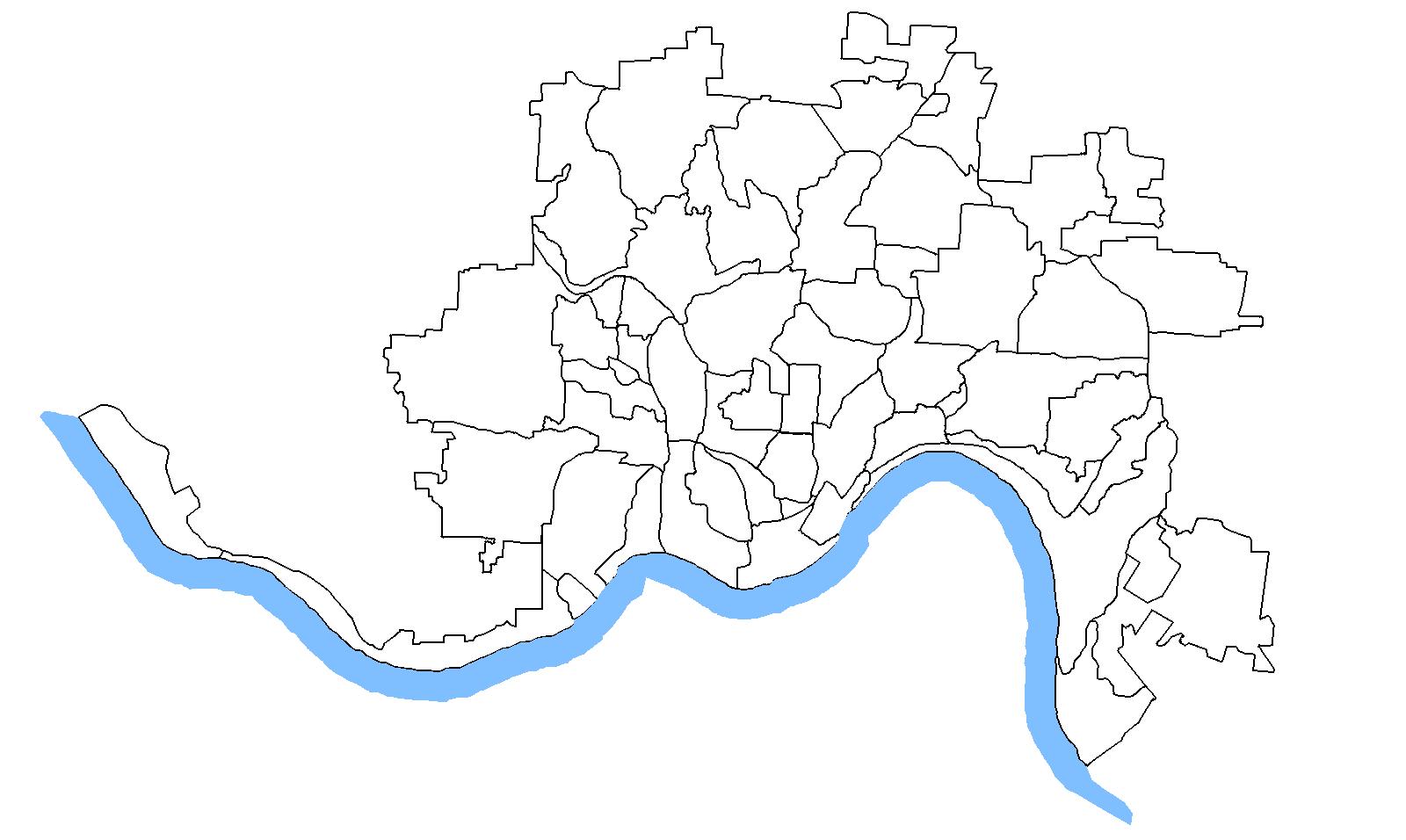

During the Spring of 2020, my group partner, Jason Keith, and I did a neighborhood study of Camp Washington. The neighborhood is commonly referred to as “Camp” by those living there and is one of Cincinnati’s oldest industrial neighborhoods. It is home to many unique establishments, such as the American Sign Museum, Queen City Sausage, Camp Washington Chili, and the Mom’n’em Coffee & Wine.

Throughout our study, we discovered many unique features about the neighborhood by analyzing the street layout, land uses, building footprints, linkages, and road hierarchy. We considered what Camp Washington does well and what it lacks, what challenges it faces, and then recommended changes. Among the changes we suggested were neighborhood branding, better connectivity, and green space access.

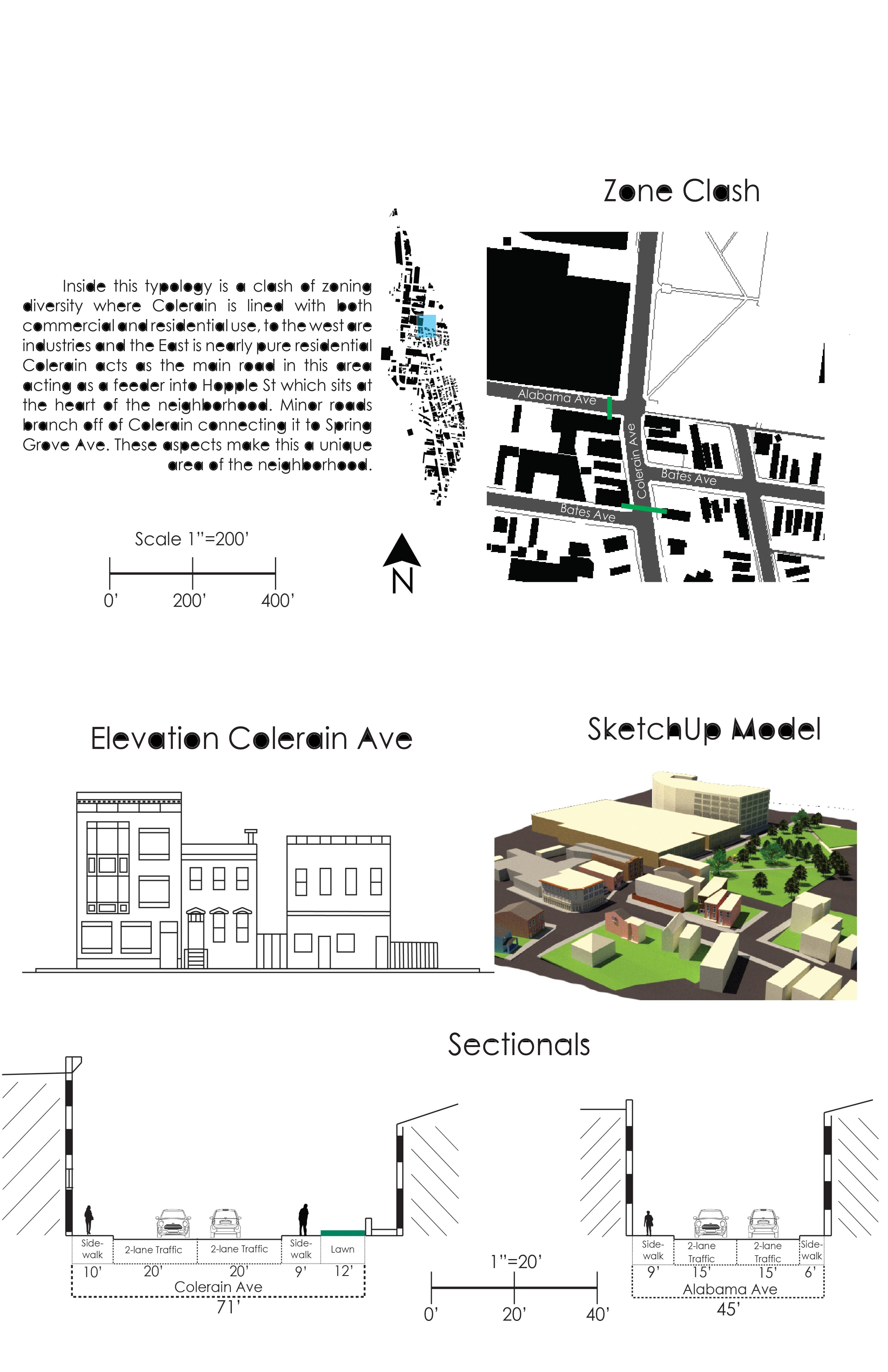

The analysis shown to the right features a small collection of blocks and streets displaying a transition of land use and zoning controls. For example, within the square highlighted below are commercial storefronts, coffee shops, warehouses, a park, and residences. All of which line a 300ft stretch of Colerain Avenue.

The section and elevation views characterize this area’s streetscape, architectural aesthetics, and density. Additionally, I replicated the look and feel of this area using SketchUp to gain a spatial perspective.

SketchUp & V-ray Rendings

Elevation View

Section View

SketchUp & V-ray Rendings

Elevation View

Section View

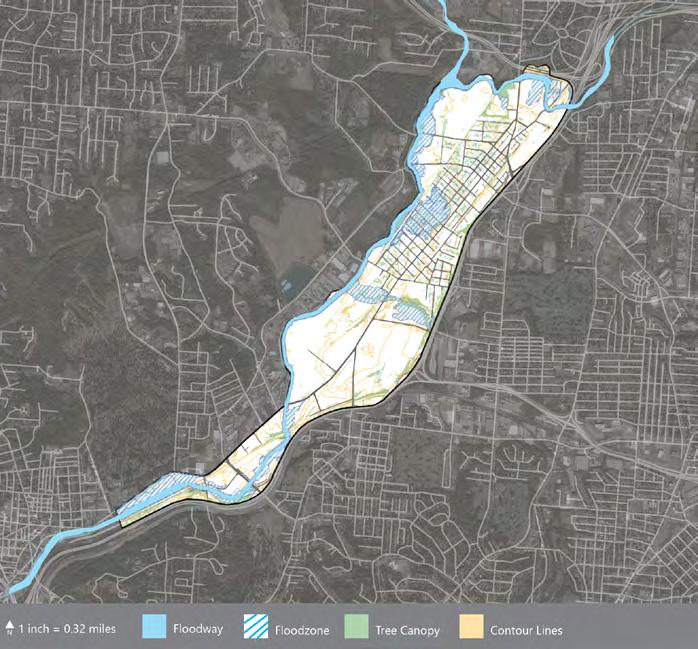

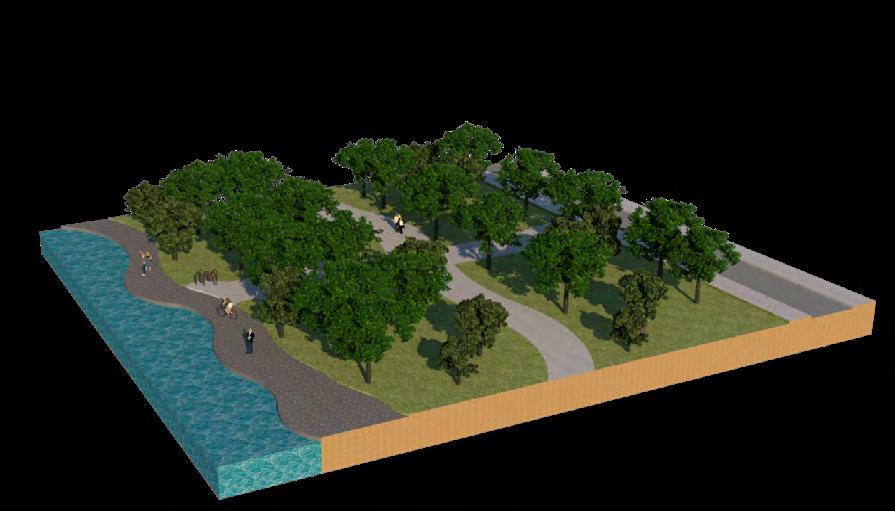

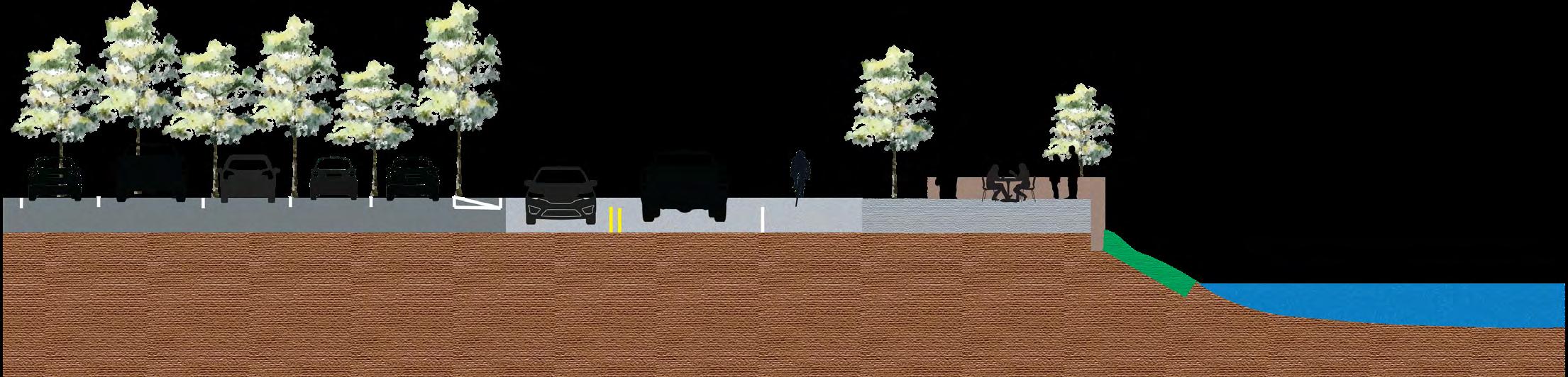

The Mill Creek is the only water feature in Camp Washington and has little to no community access. Once an endangered urban waterway, is now a opportunity for a unique urban blueway and greenway spanning through multiple Cincinnati neighborhoods. Existing today is a small paved bike trail along the northern tip of the neighborhood that starts on Mill Creek Rd and runs through other Mill Creek Neighborhoods. The trail is rarely active and is partially used to store leftover construction material.

I recommended redesigning and extending the bike trail to increase pedestrian use, neighborhood branding, provide access between Millvale and Camp Washington, and improve neighborhood green spaces. The site plan to the left features a redesigned trail, park, and a pedestrian-friendly entrance into Millvale. In addition, street parking should be provided along Mill Creek Rd.

The site plan is consistent with The Crown Cincinnati, the city’s first urban bike-loop, plans to provide an urban bikeway along the Mill Creek corridor.

• Modern design

• Mill Creek access

• Increased tree canopy

• Camp Washington banners

• Light posts

• Bike and pedestrian facilities

Installing wrought-iron fencing instead of the existing chain-link fence will make the park more inviting and encourage use in the area. It also continues to provide public safety from the busy rail yard.

A pedestrian bridge connecting the trail to Millvale would increase connectivity between the two neighborhoods, making the border between the two less of a challenge.

This addition also provides an opportunity for more tree canopy and an outdoor running, biking, walking trail, and much needed increased access to a waterway.

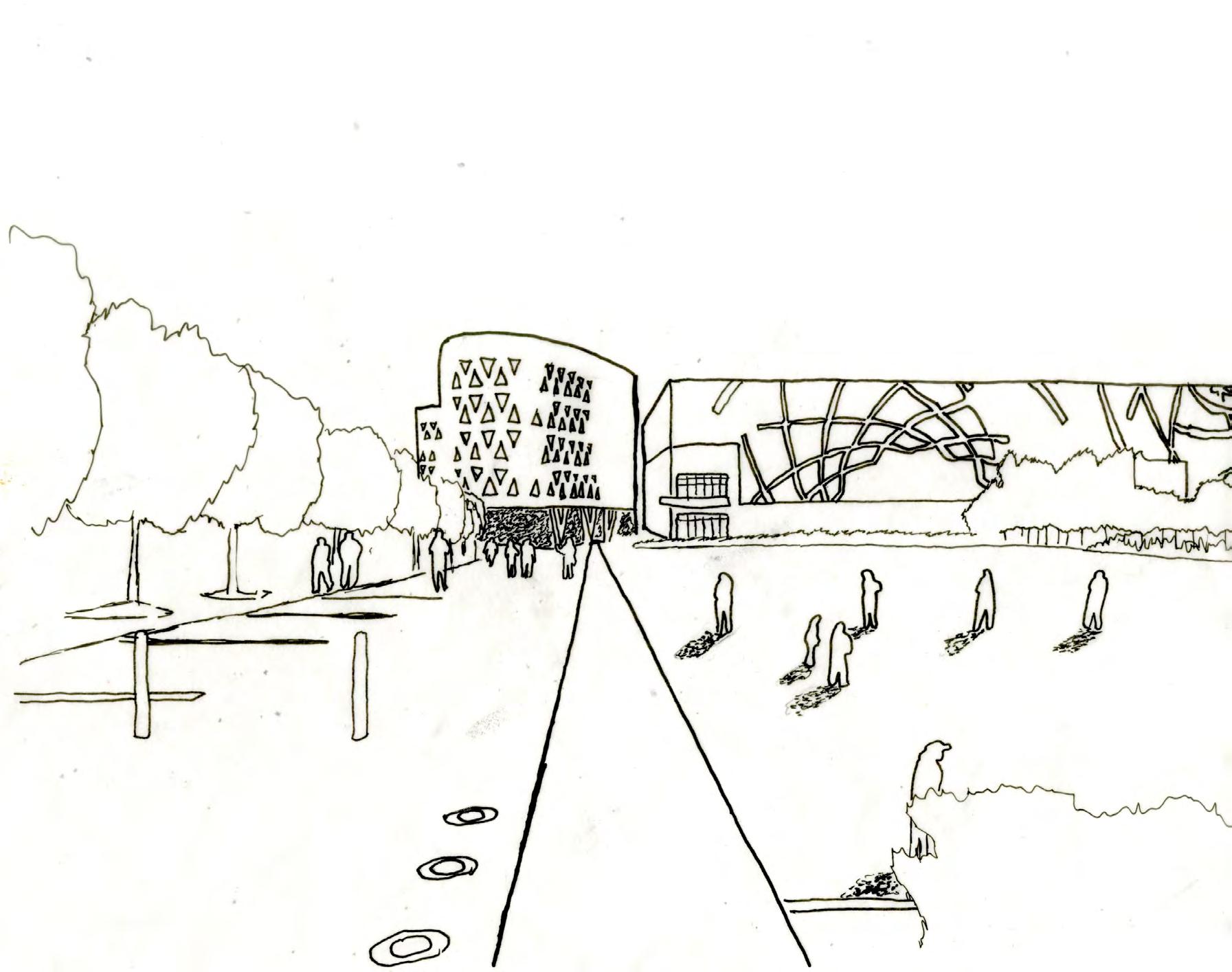

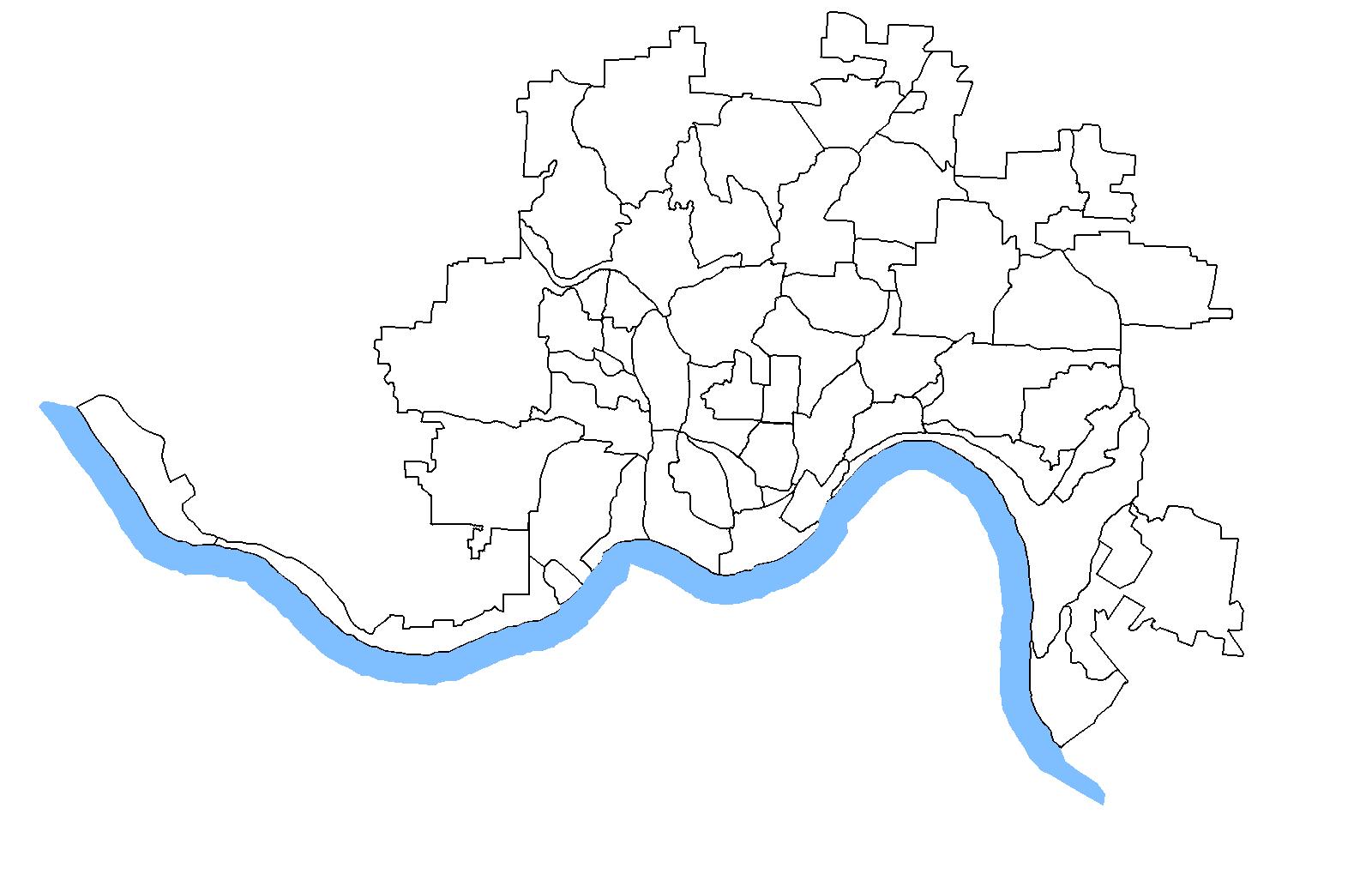

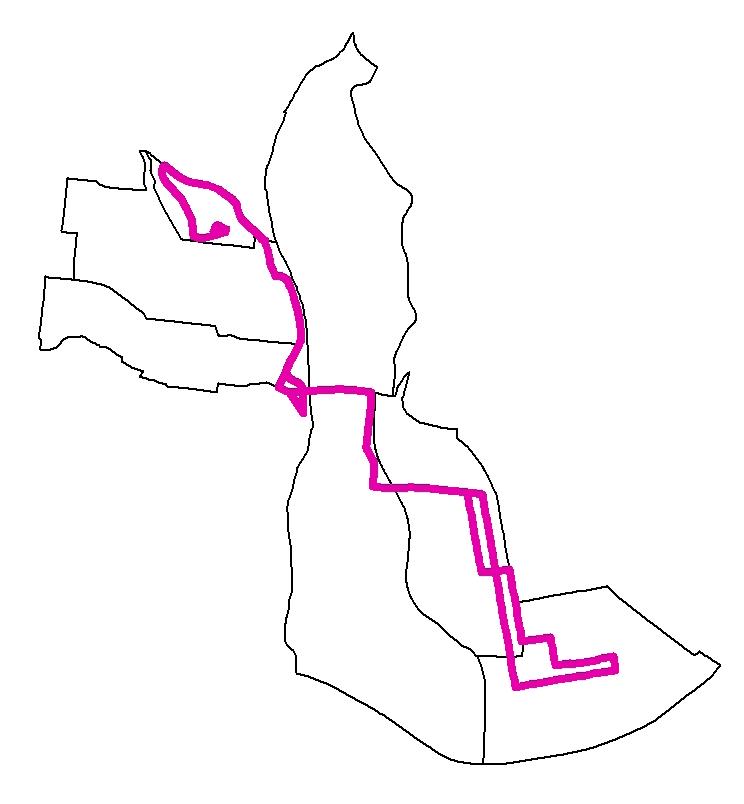

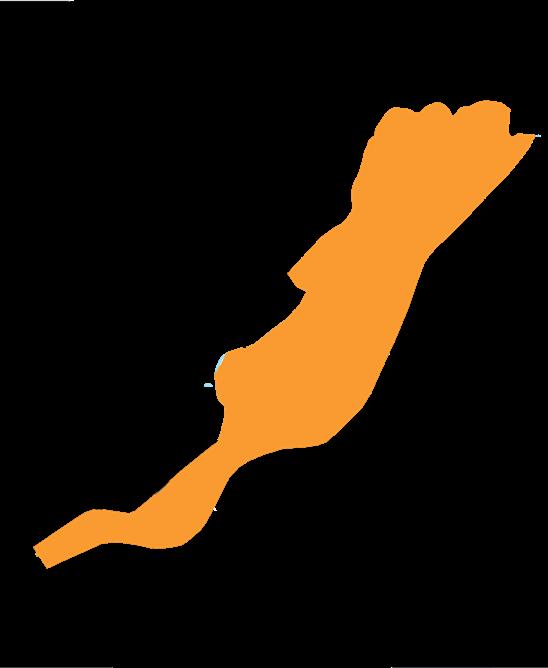

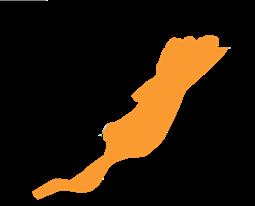

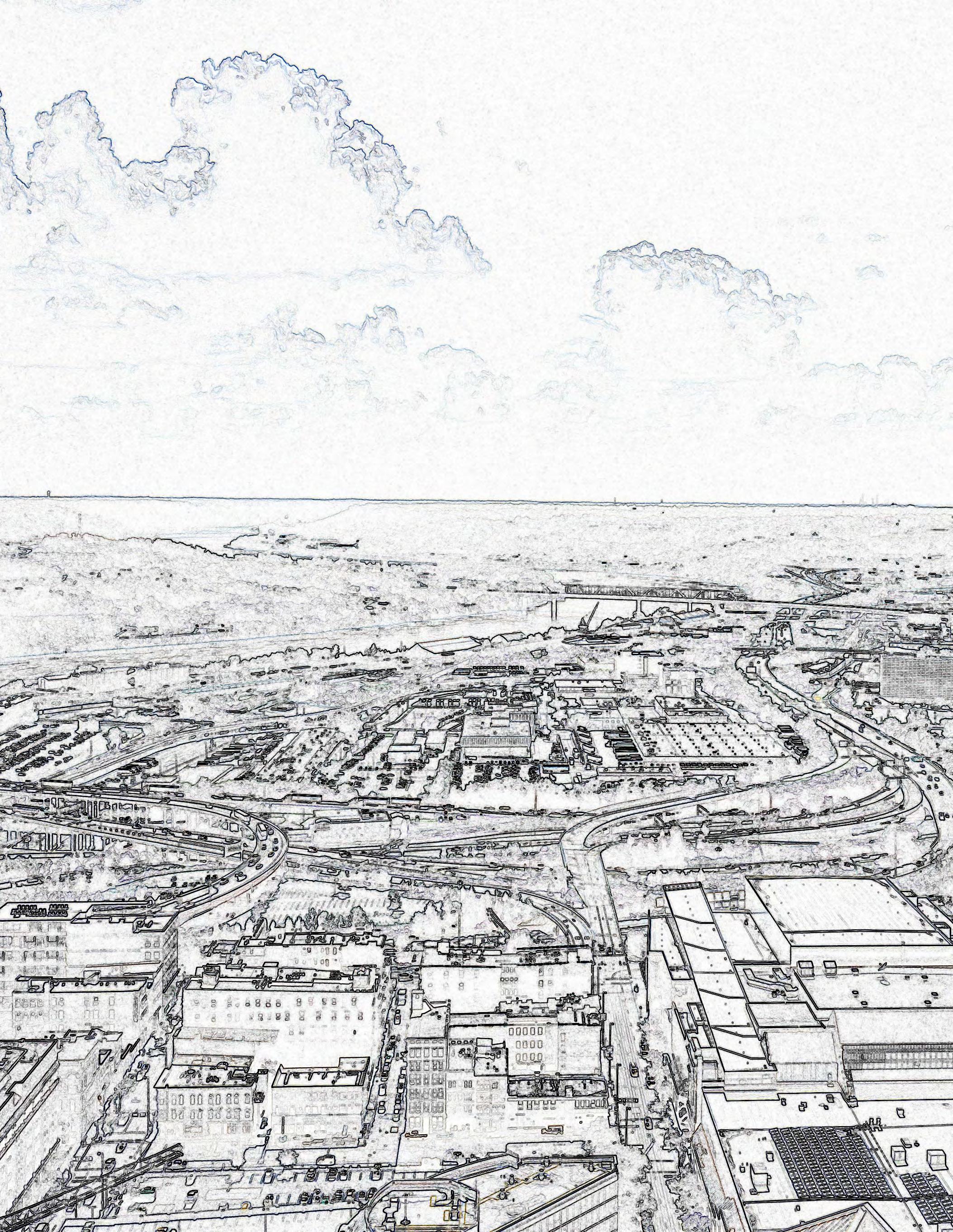

During the Summer of 2021, my partners, Jason Keith, Nick Heaton, and I developed a Mill Creek Access plan spanning from Salway Park in Cincinnati’s Spring Grove neighborhood to the neighborhood of Carthage. We began our analysis by evaluating the corridor’s current conditions and locating issues and opportunities throughout. We then developed a framework for our analysis and set our goals and objectives. This process allowed us to develop a set of strategies (Shown to the right) which we’d recommend throughout the corridor.

Carthage

• Implement designated/protected bike lanes on arterial roads.

• Implement crosswalks on arterial roads and nearby access points.

• Promote economic development near access points & fairgrounds site.

• Program new amenities nearest to the creek.

• Use signage, lighting, and trees to draw attention to creek access and amenities.

• Highlight Arterial-Connector intersections to promote development.

• Use bridges and tunnels to connect greenway.

• Update land use along the Mill Creek

• Incorporate Vine Street

• Ensure that actions reflect inclusivity.

• Ensure residents have access to green space.

• Create a resourceful community using thoughtful development methods.

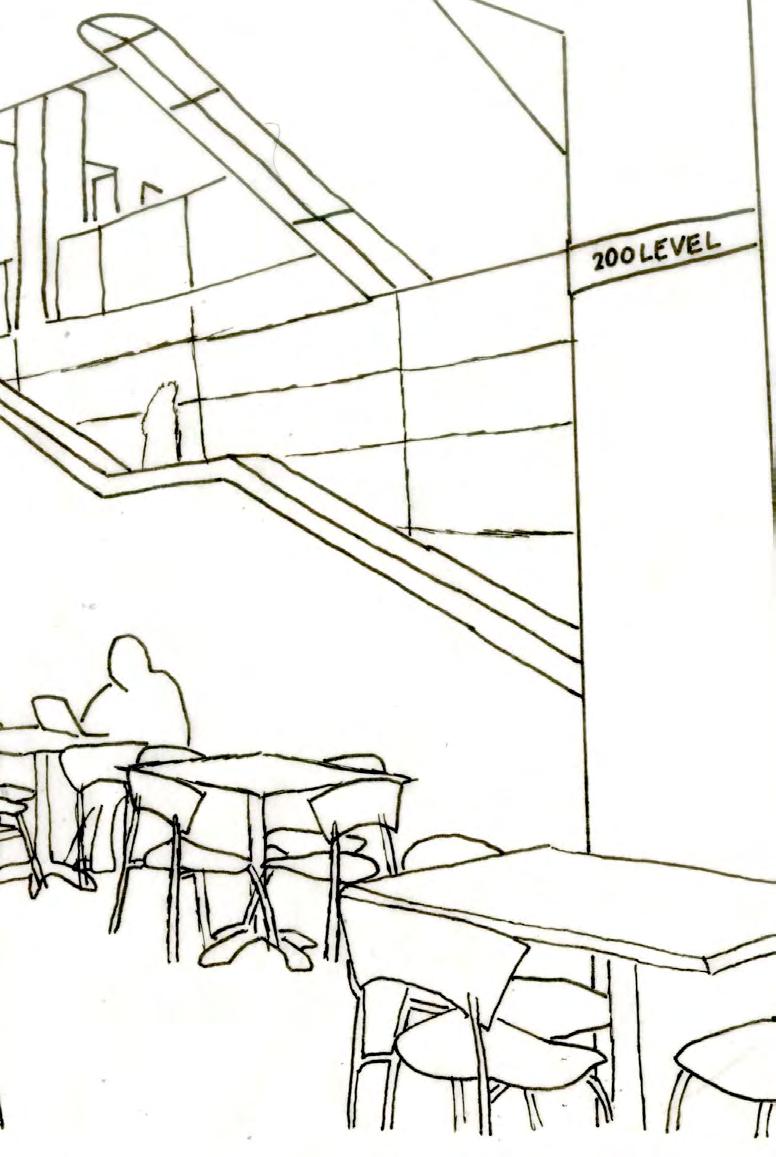

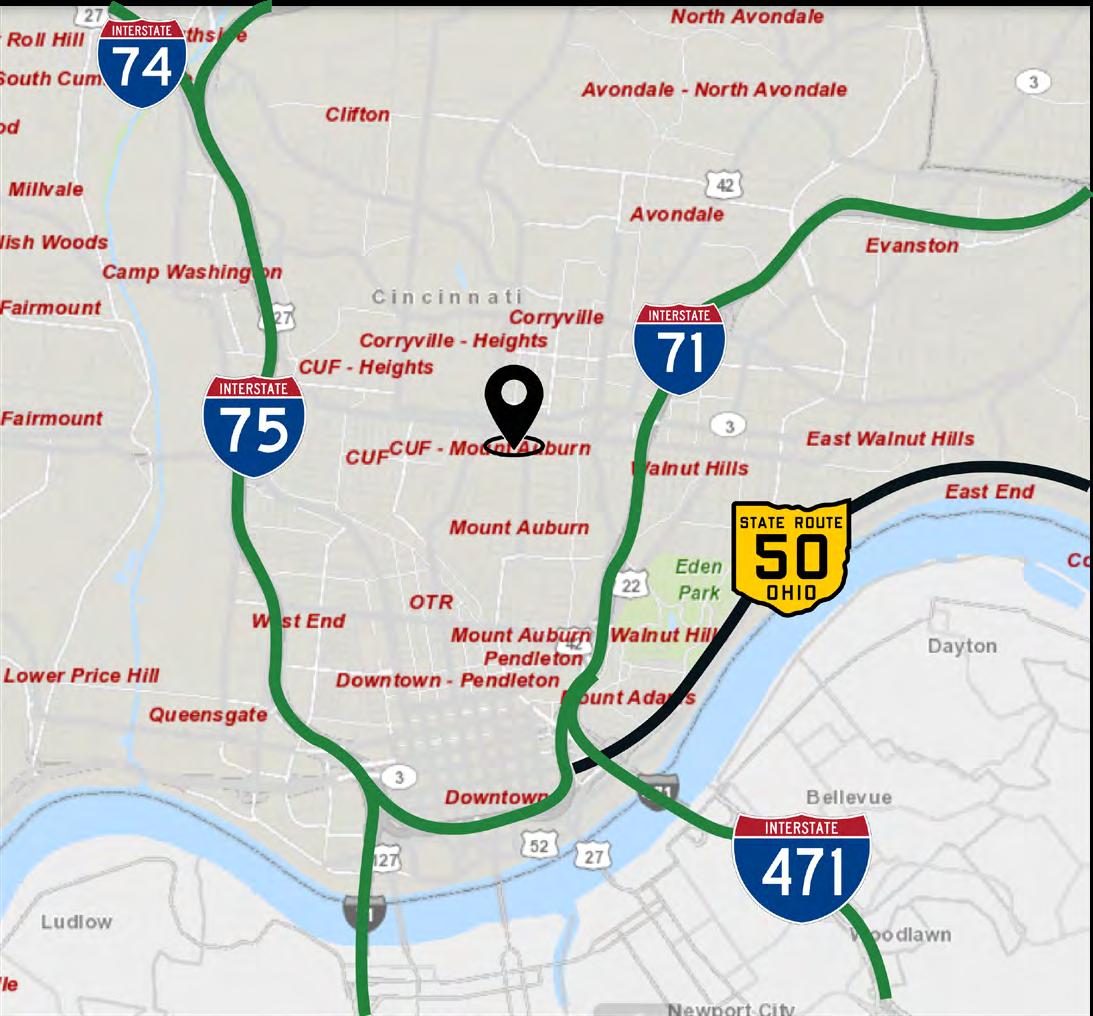

Fall of 2021, I began taking real estate courses to better understand property rights, values, and management from a developer’s perspective. In the course “Real Estate Development,” the class was tasked to analyze any property for any development project. The project was to be accomplished in teams, with each team designating roles for Project Manager, Accountant/ Financier, Architect/Planner (me), and graphic designer. As a team, we presented a three-story fifty-unit apartment building located at the corner of Auburn Ave. and E McMillian St. in Cincinnati, Ohio. This unique location is within a 1-mile radius of the University of Cincinnati, three regional hospitals, shopping, dining experiences, and bars. Our development, The 24 at Auburn, was supported by student housing research, demand in the CUF and Mt. Auburn neighborhoods, comparable land acquisition and development cost. We also researched zoning changes, on-site infrastructure, and nearby transportation around our desired location.

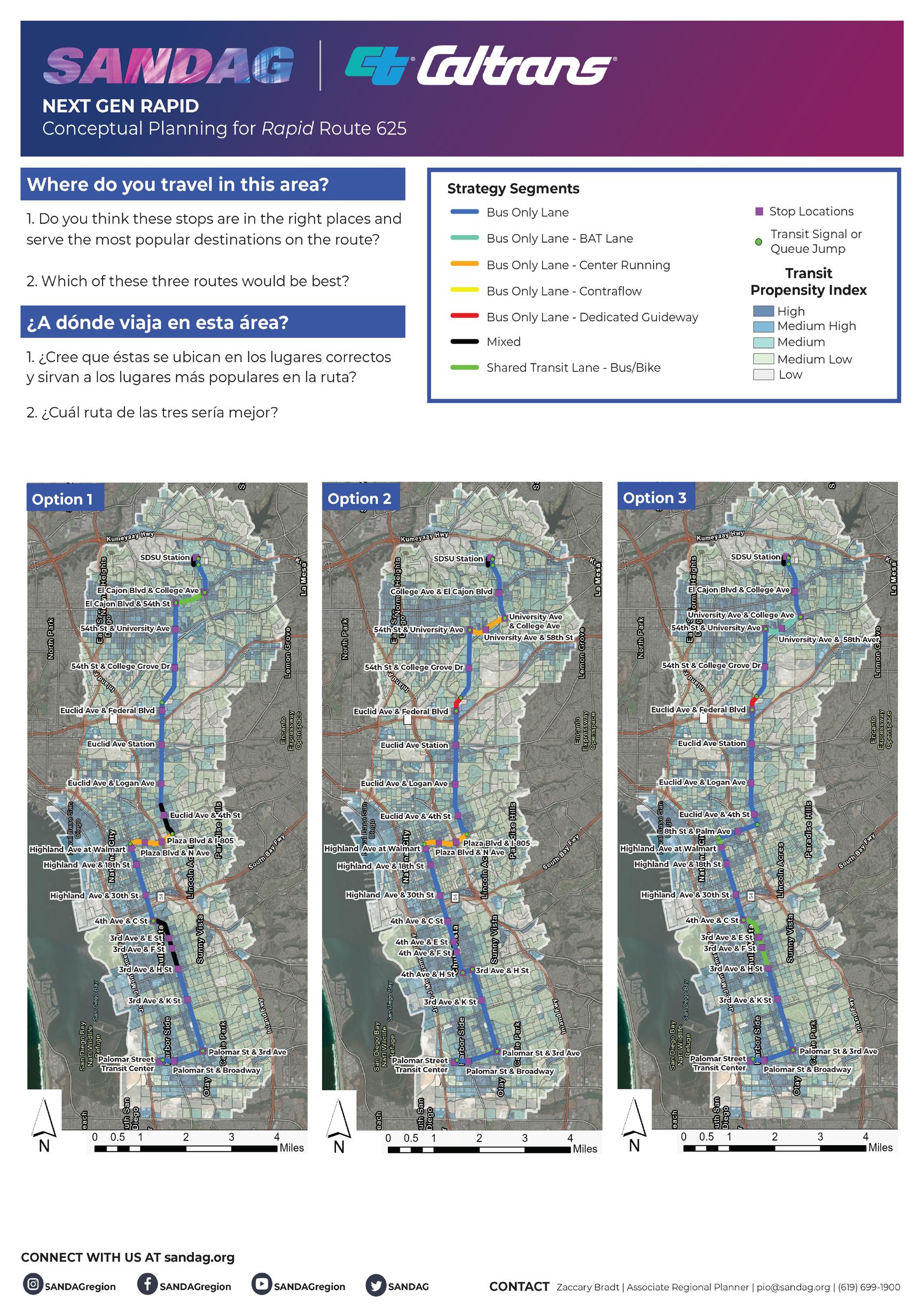

Spring of 2023 while co-oping with HNTB in San Diego, I was tasked with putting together interactive public outreach boards for our Next Generation Rapid Routes 41, 471, and 625 task order. Our client, SANDAG, was seeking public input on the most recent updates to the conceptual routing and road treatments for three bus rapid transit (BRT) routes. Throughout this term I worked in depth in the development and analysis of these routes, including being involved in developing road treatments, routing alternatives, and station locations. For the public outreach component of this project, SANDAG, HNTB, and our sub-consultants attended three pop-up public engagement events, which utilized the public outreach boards shown to the right and the next page. These were primarily designed by myself with edits and assistance from colleagues within HNTB and SANDAG.

1 2 3

Residents are asked to evaluate each routing alternative and their treatments. Then to select a preferred alternative.

Residents are provided an opportunity to evaluate potential road treatments along a selected set of segments.

Residents are able to suggest alternative trade-offs to road treatments along each segment from board 2.

In the Fall of 2021, I developed an inventory of M/I Homes’ community entrance monuments within Cincinnati that detailed design aesthetics, materials, landscaping, and architectural elements. I repeated this process of documenting and providing specifics, including cost estimates, for twelve community profiles.

The purpose of this document was to assist M/I Homes of Cincinnati, LLC, in the monument and amenity selection process. Creating these community profiles has enabled a better internal understanding of the types of monuments and amenity pairings desired by the buyer in the design development process. In addition, the profiles allow us to review what has worked well in the past and will assist in planning future M/I Homes communities. Shown to the right and below is one of the twelve community profiles.

Cincinnati relies heavily on the ownership and usage of personal vehicles to move around the city and the metropolitan area. When you zoom out, this is seemingly an issue for cities across the Midwest and the entire United States. Unfortunately, this has led to terrible traffic congestion in our cities. On average, people will spend 27.6 minutes in traffic/ commuting one-way daily in the United States as of 2019 (Friedrich, 2021). In Cincinnati, people spend 25.2 minutes in traffic commuting one way (Stacker, 2022). While this seems like a significant amount of time in our vehicles, not every American can afford or want to maintain a personal vehicle and instead rely on public transit to commute around cities. Unfortunately, the average public transit commuter spends 45-47 minutes in commute oneway, far longer than independent drivers (Maciag, 2021). In Cincinnati, bus commuters spend upwards of 50 minutes commuting one-way for work as of 2018 (LaFleur, 2018). One common solution suggested is electric cars. However, electric vehicles have two main issues of their own. First is the affordability of electric vehicles, and the second is the availability of electric charging infrastructure. According to Kelly Blue Book, the average cost of an electric vehicle in August 2022 was $66,000 in the United States (Ahmad, 2022). The most inexpensive electric vehicle on the market is the Chevrolet Bolt EV and Chevrolet Bolt EUV, with asking prices for the 2022 models starting at $25,600 (2023 Bolt Ev: Electric Car). While this is considered a high cost to expect families to carry, green plans, state laws, and federal policies are seeking to curb the cost for everyday Americans and manufacturing production, including Cincinnati’s green plan. The second major issue of charging infrastructure is also being addressed in green plans and federal policies to curb costs and encourage investors to build more charging stations. However, an overwhelming majority of the vehicles we drive are gasoline-powered, leading to lower air quality in our cities. Approximately less than 2% of personal vehicles on the road are electric vehicles in the United States (Kopestinsky, 2022).

Dear Resident:

As the owners of (Address), this letter serves as notice that staff has observed junk vehicles constituting a nuisance located in the Rear Yard. Additionally, there is a camper and trailer parked on the property that needs to be stored either on a driveway or in a garage (see attached photos). These vehicles are not permitted to be parked in the rear yard and appear to be junk vehicles as defined by Ohio Revised Code section 505.173.

Owners must obtain a permit to have a pool structure according to the Hamilton Township Zoning Code: Table 4-5: Permitted Accessory Uses

Additionally, the pool structure must be fenced (at least 4 foot tall) with a self-latching gate or surrounded by walls (at least 4 foot tall) with a pull up ladder:

4.9.5. Accessory Use and Structure Regulations

(2) The swimming pool, or the entire property on which it is located, shall be walled or fenced to prevent uncontrolled access by children from the street or from adjacent properties. Said fence or wall shall not be less than four feet in height and maintained in good condition with a self-closing, self-latching gate that can be locked. Above grade pool walls may be counted toward the height of the required fence

Finally, there are two recreational vehicles on site. Hamilton Township Zoning Code only permits for one recreational vehicle be on site:

7.9.1. Use Specific Standards In any residential district, a recreational vehicle, travel trailer or boat trailer shall be prohibited, except:

A. One recreational vehicle, one boat on a trailer, and one trailer may either be parked on the property or stored in a garage or other accessory building or rearyard.

Therefore, we ask that you come into compliance with the Hamilton Township Zoning Code junk parking requirements and private swimming pool requirements, by DD/MM/YYYY (within the 14 day time period granted to you in the Ohio Revised Code, Section 505.871). If action is not taken by that time, the Hamilton Township Board of Trustees will provide notice via certified mail and remove the vehicles and campers at your expense.

“There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”

-Jane Jacobs