NATIONS, DANUBE, AND THOSE WHO LIVE CLOSE BY (part I)

Landscape Architecture Master Thesis Acacemie van Bouwkunst Amsterdam - 2025

Landscape Architecture Master Thesis Acacemie van Bouwkunst Amsterdam - 2025

Introduction

As a landscape designer, I have learned that a healthy river is one that flows freely, and that over time, it meanders, floods, and recedes. It erodes land even as it builds it up. Its bend grows increasingly pronounced until, eventually, the river cuts its own arm and forges a new path.

On the other hand, a jurisdictional border defines which area is governed by whom. In today’s world, as nations stand shoulder to shoulder, peaceful relations require borders to be precise and static in order to be mutually recognized.

This perception on borders seems to contradict to the nature of a river.

This realization led me to ask: How can a river border be ‘natural’? So that a river’s health is guaranteed while the national borders are recognized.

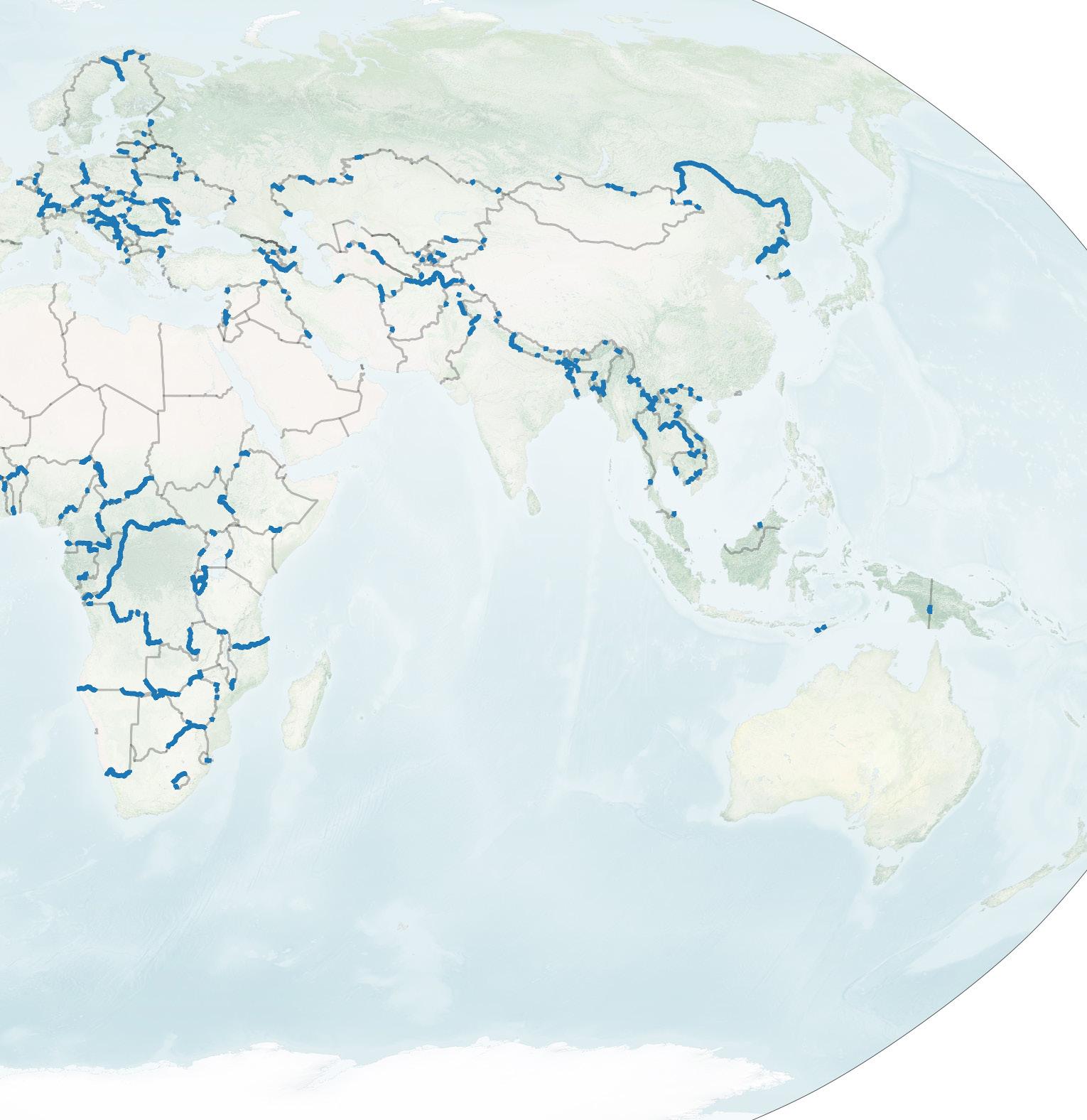

Of the 195 nations recognized by the UN, there are more than 300 land borders between countries. Almost one third of them follow a river.

In Europe, the Danube is a prominent example. It begins in the Black Forest in Germany, flows to the east, crosses or skirts nine countries including Slovakia and Hungary, and empties into the Black Sea. Most of these countries are members of the European Union -- where the border gates are open, but the door frames remain.

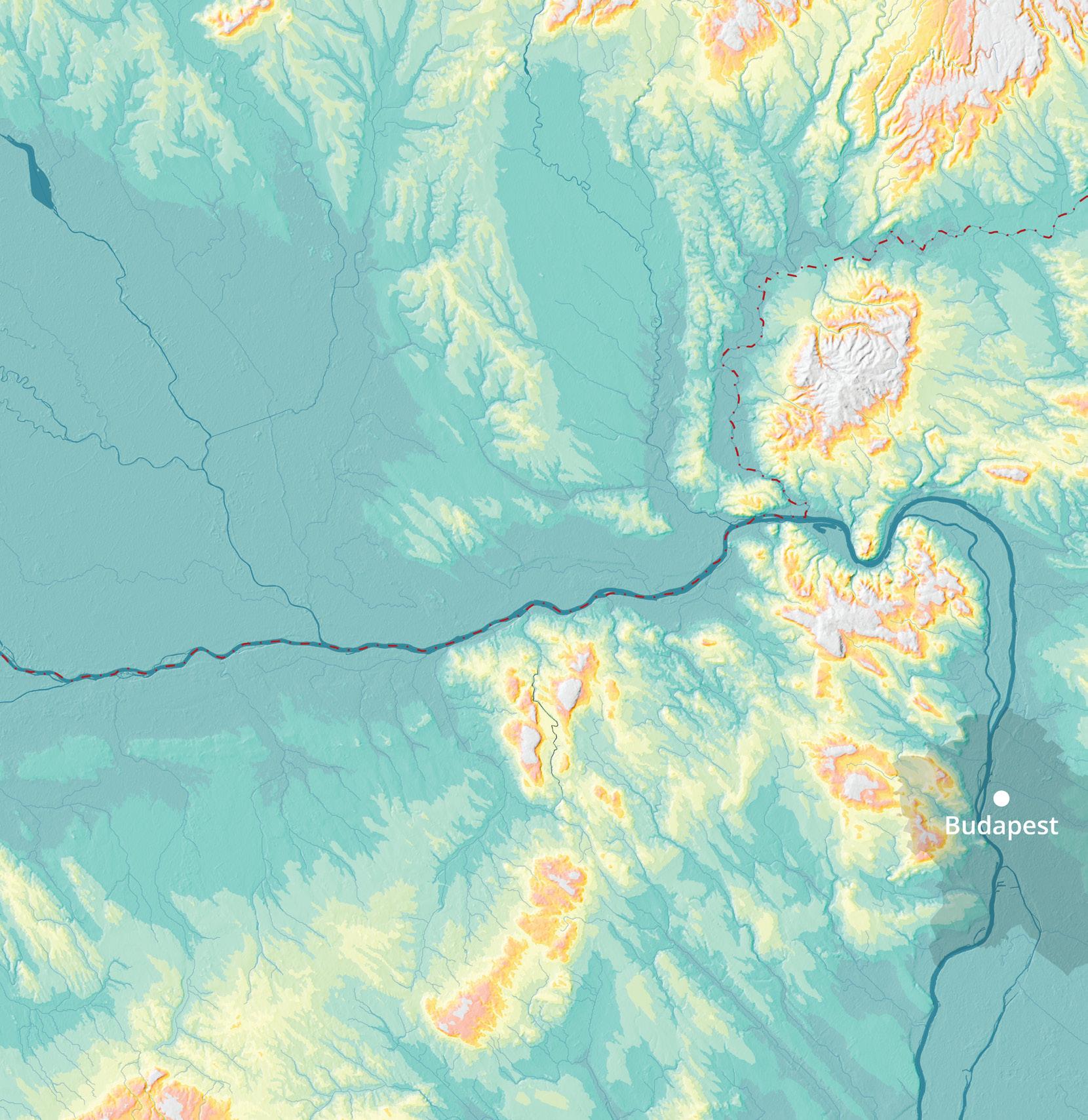

Due to the closed location to the Netherlands and my own lack of knowledge about Central Europe, I chose the Danube border between Slovakia and Hungary as my site of study. I then cycled from Vienna to Bratislava and to Budapest along the Danube to discover, observe and research.

During my two-week journey, I hiked to mountaintops and kayaked in the stream. I walked besides the Danube and through its forests and wetland. I saw the ruins from the Roman Empire and traces from the Cold War.

Along the way, I discovered the fascinating case of the Gabčíkovo Dam, which runs parallel to the Danube border. The realization of the Dam is a story of complex geopolitical relationships entangled with the demands of water engineering—ultimately reshaping the river’s ecosystem and groundwater levels, with consequences for both nations.

It was here that I chose to focus my attention.

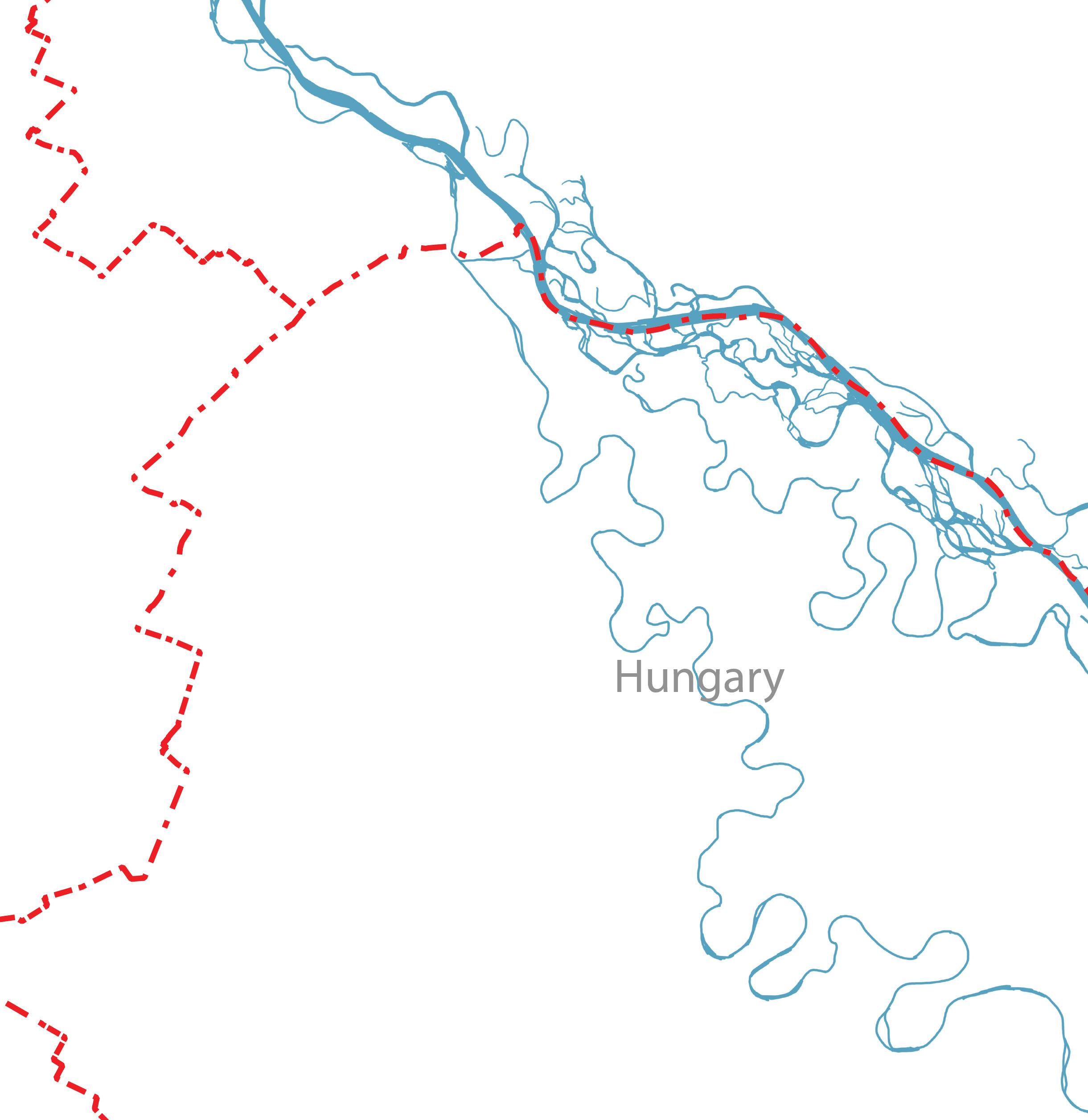

Hungary

In this project, for the sake of simplicity, I refer to the entire Gabčíkovo Dam system—including its reservoirs and water supply channels—as “the Dam.”

(Historical) relationship between human, nation

nation and the Danube

In 1867, following the Austrian defeat in the Austro-Prussian War, The Blue Danube—a waltz brimming with bright, uplifting melody—was composed to lift the nation’s spirit. As its notes echoed through Vienna and across Europe, the Austrian Empire joined hands with the Kingdom of Hungary, forging a new Central European power. Over time, The Blue Danube became one of the most celebrated pieces of music in the world.

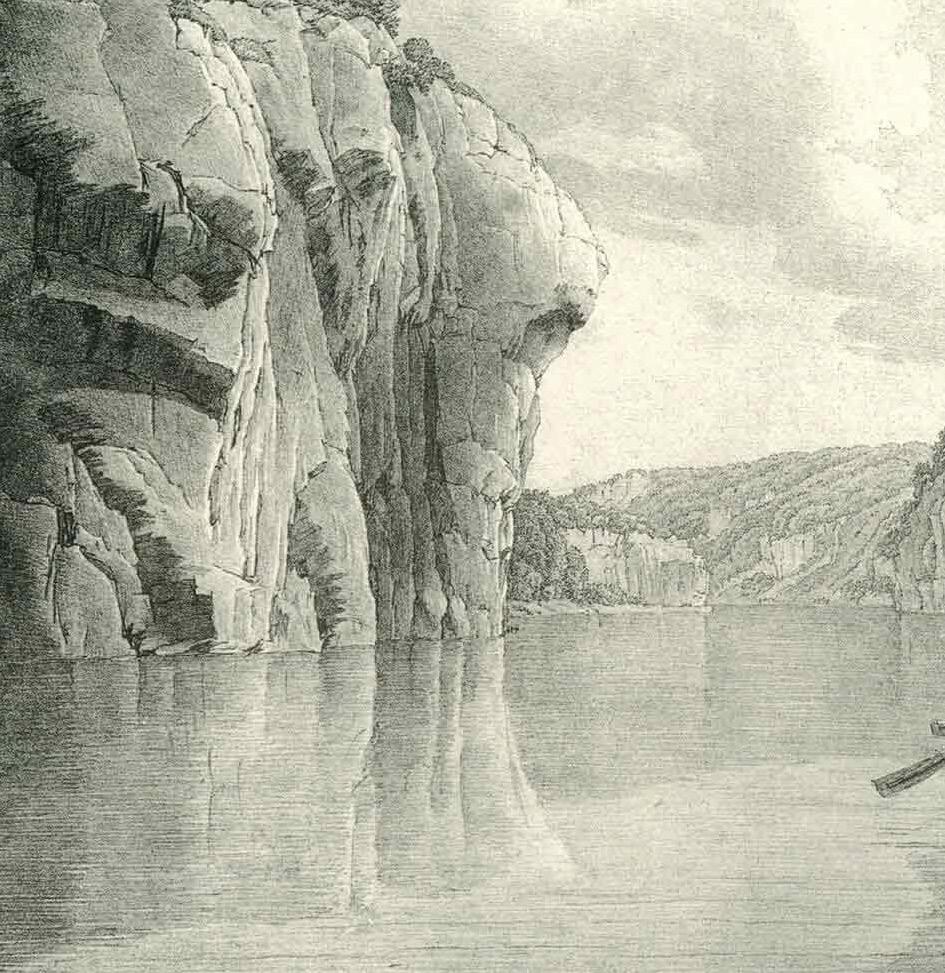

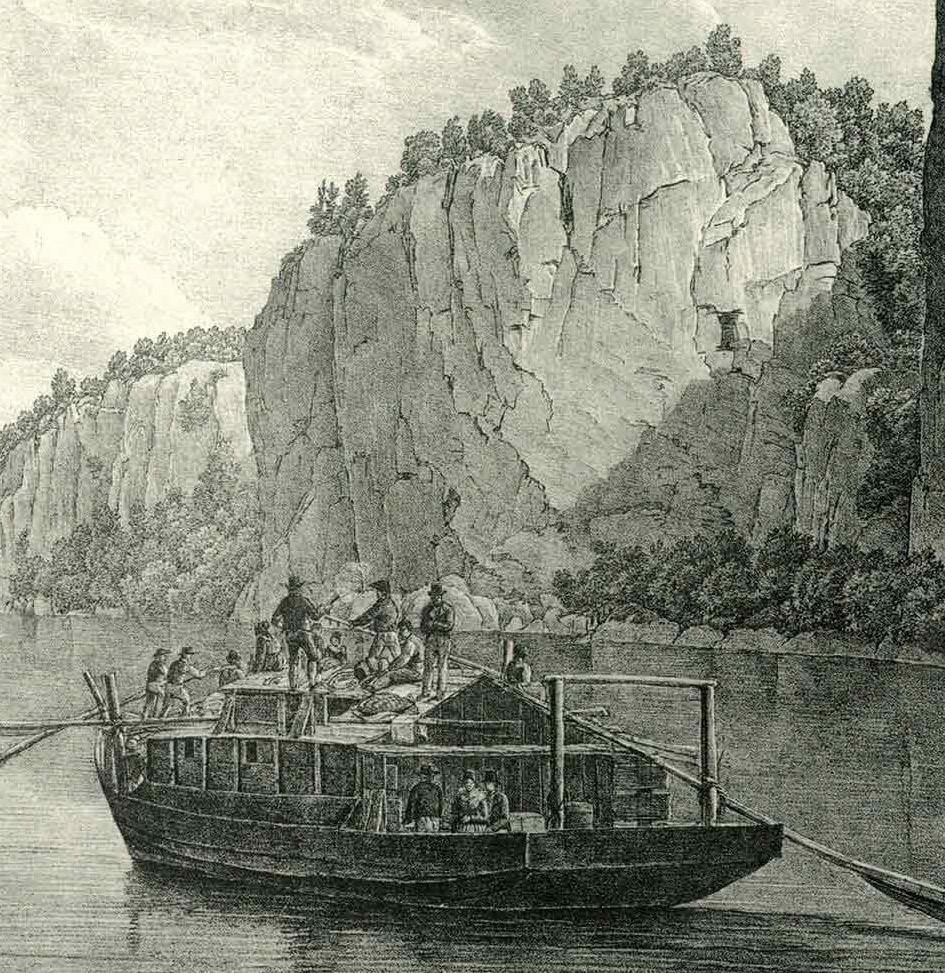

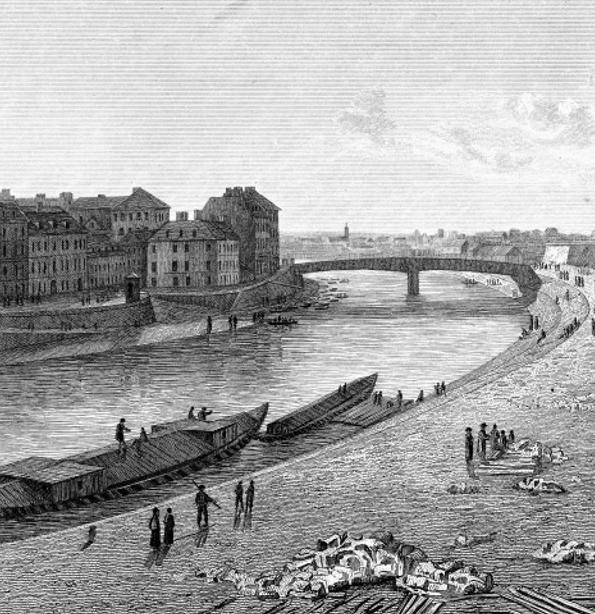

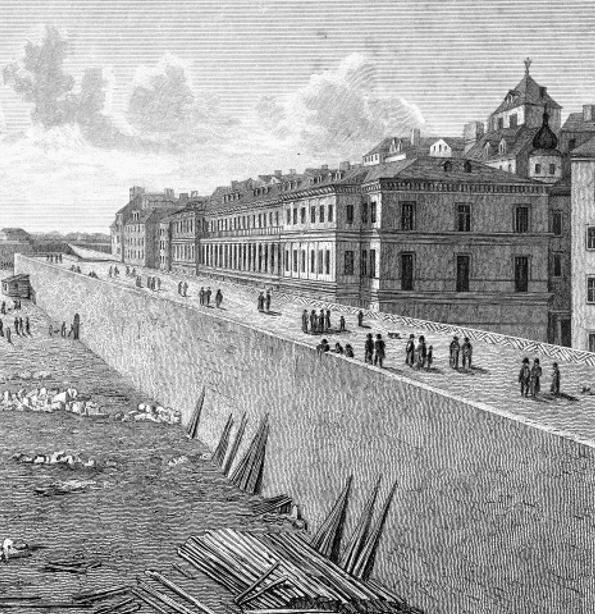

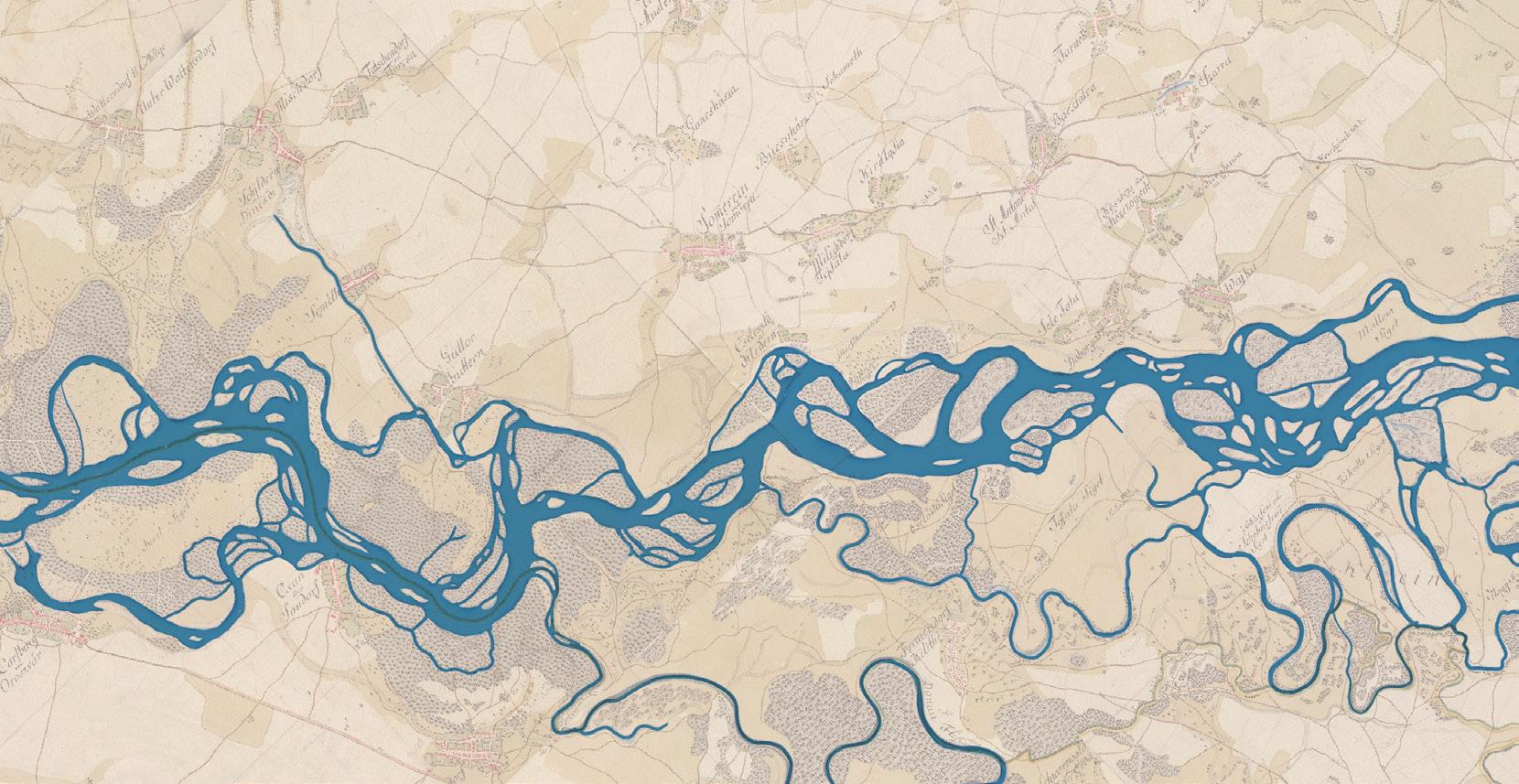

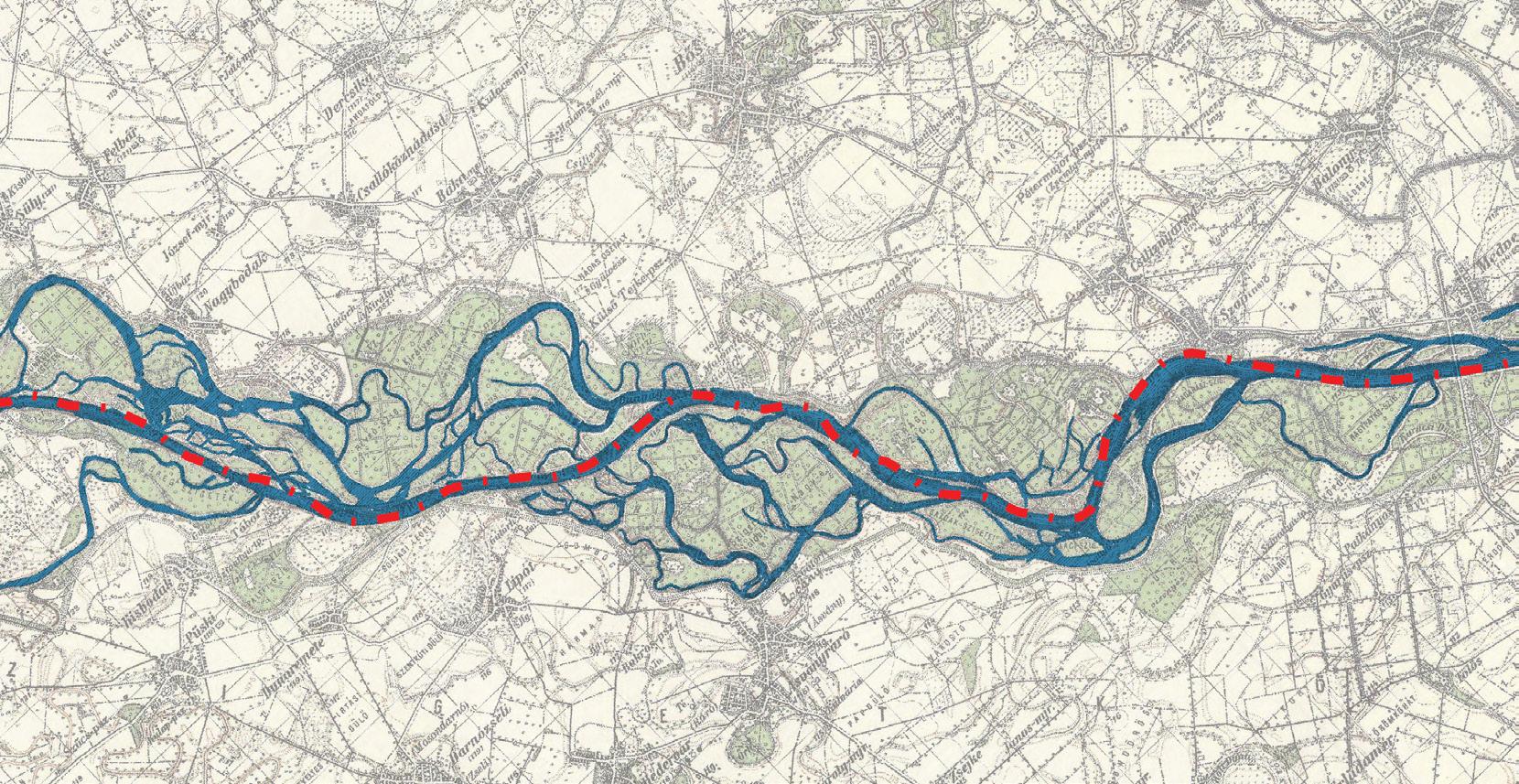

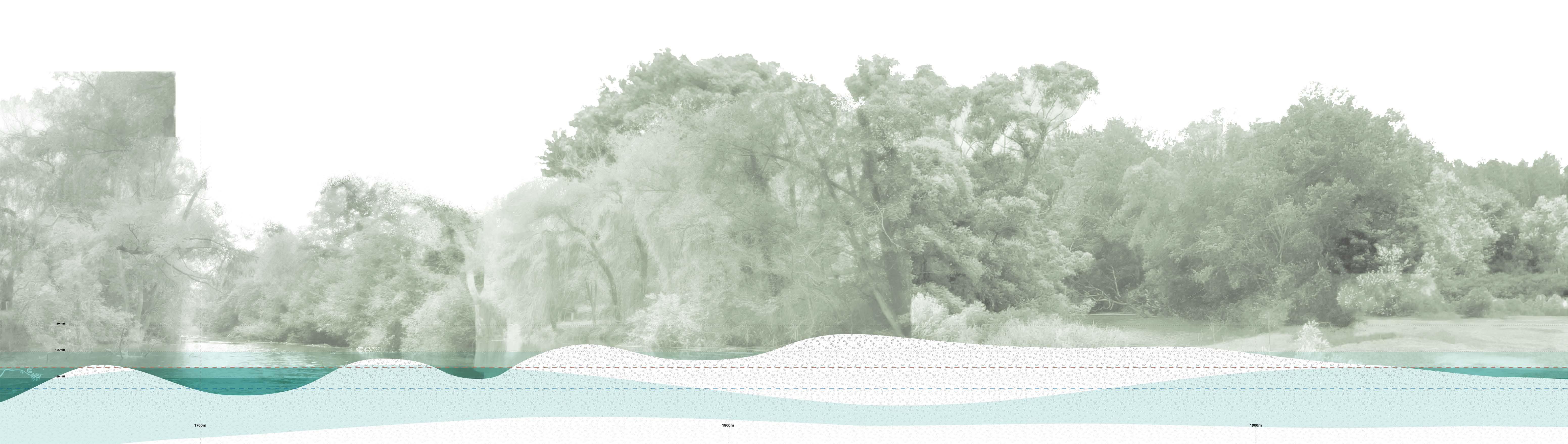

The Danube first wound through the forested hills of Germany, its water shallow, clear and swift. As it flowed between the mountains in Austria, its course broadened and became steadier. After the river passed Pressburg, today’s Bratislava, its character changed once again.

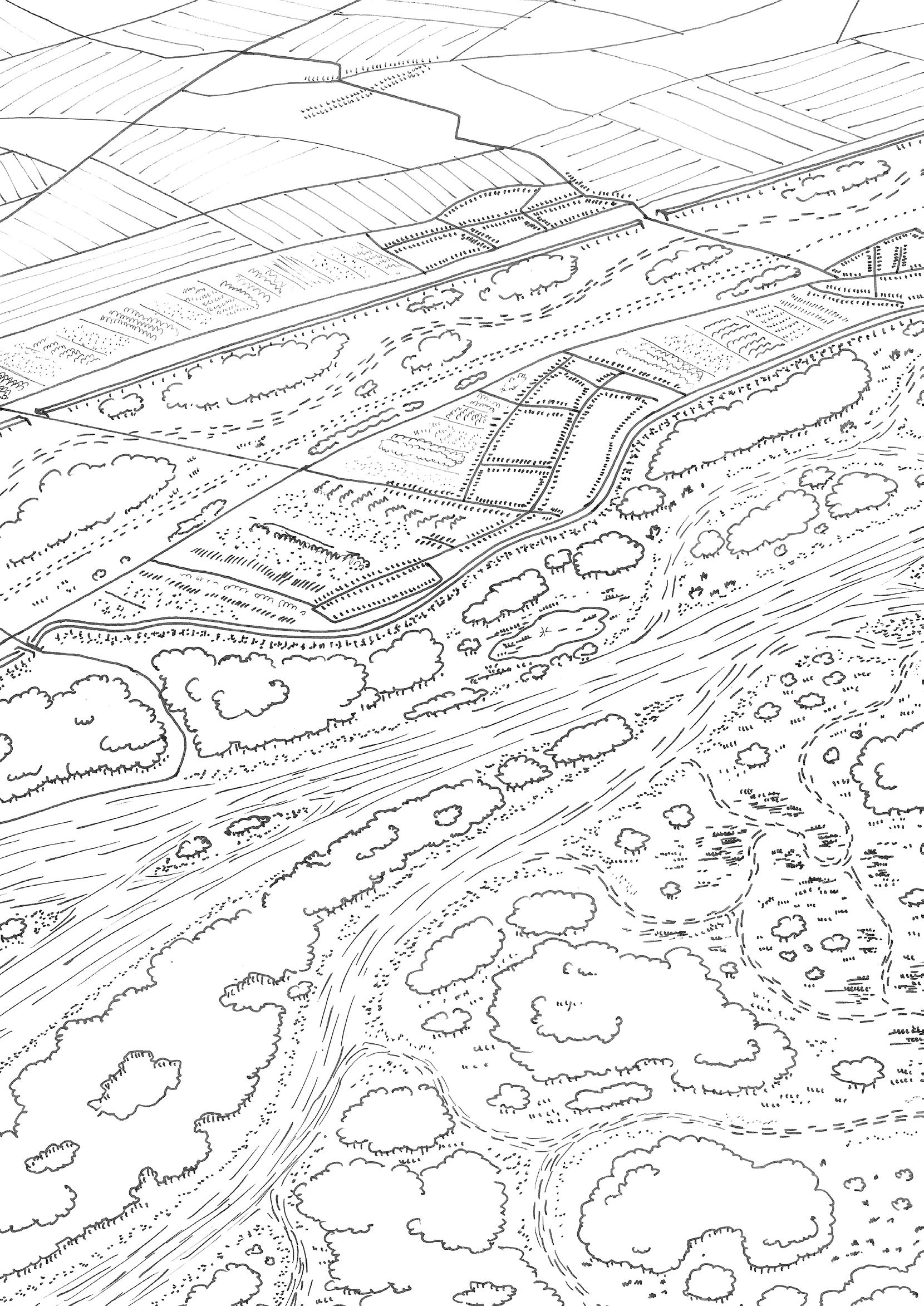

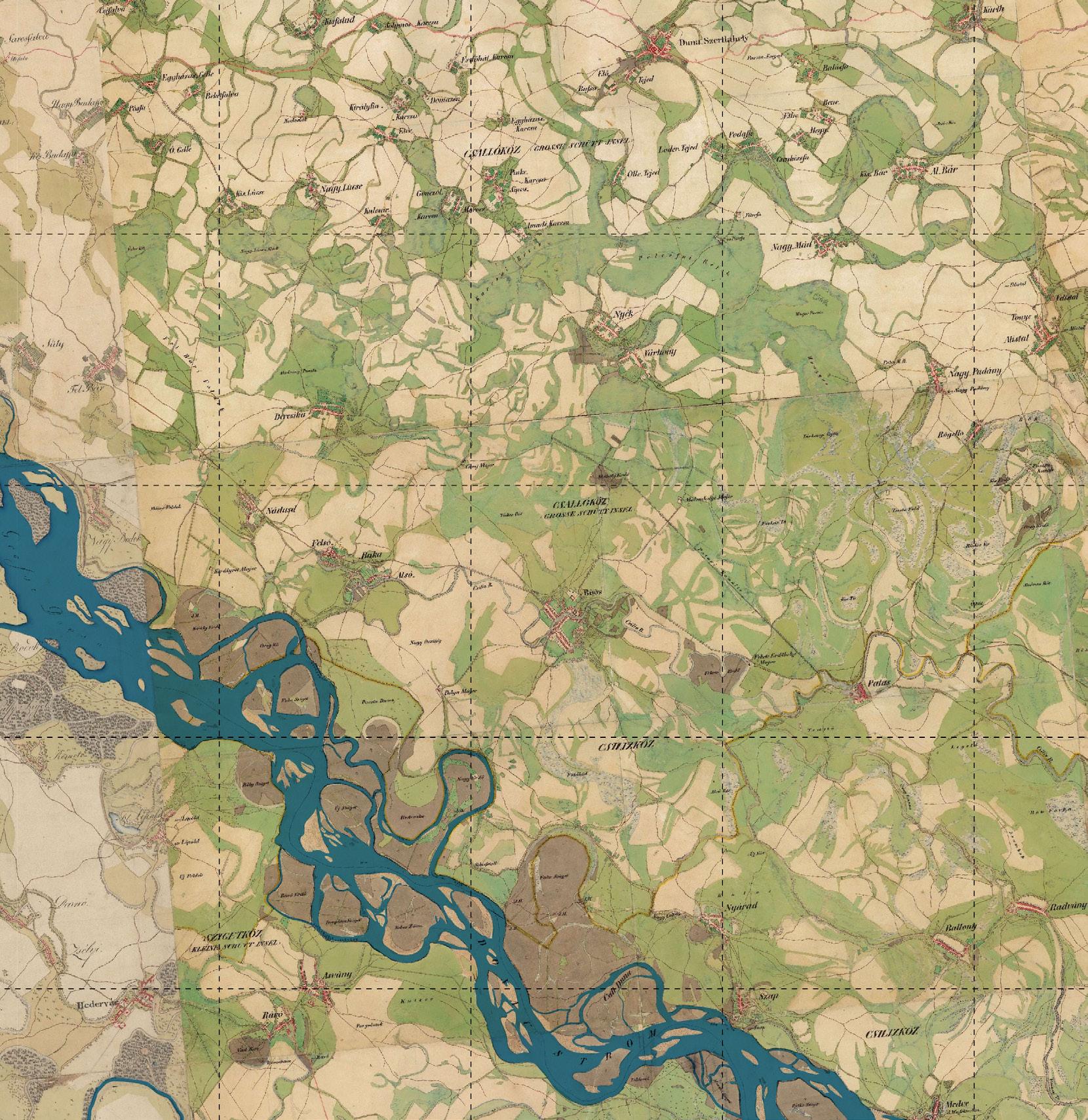

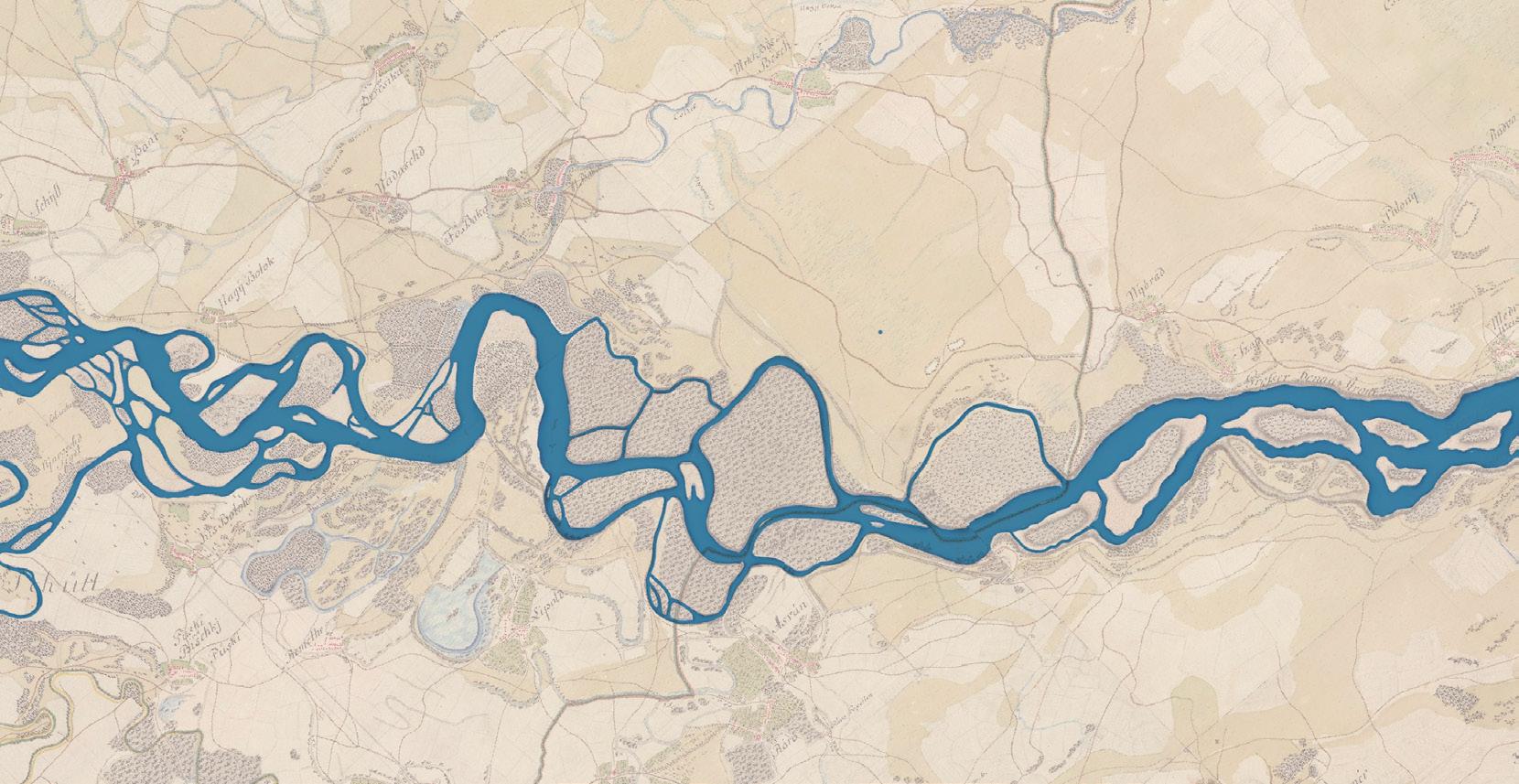

With no mountains to restrain its course, the river ran unbound across a flat land stretching 50 kilometers. Wide and narrow channels fanned out, met, and parted again -- each in turn dominating the other -- endlessly braiding an everchanging pattern across the landscape.

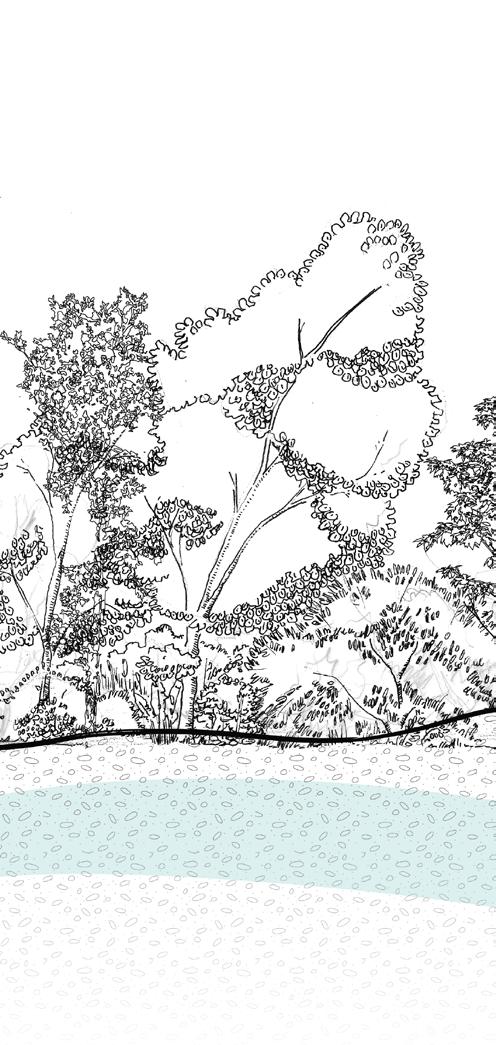

In this stretch, the Danube was not always blue. Its color shifted between dark, inky green and muddy yellow. The water was unpredictable, moody, and haunting. The land was once carpeted by miles of willow forests, and when their leaves rustled in the wind, sounded like ‘a planet flying through space.’

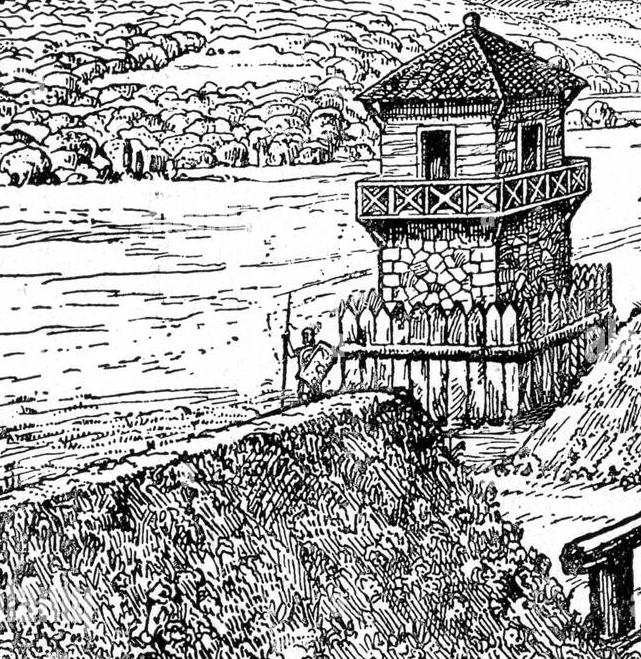

Beyond its romanticized portrayal in music and literature, the Danube has served very practical purposes throughout history. The Romans viewed it as their frontier, establishing military bases to protect the Empire from the ‘Barbaricum.’

The Kingdom of Hungary, year 1593 in this image, saw the river as a land of productivity. Along its banks, they farmed, grazed, and harvested, drawing sustenance from the Danube.

Austria-Hungary (1867-1918) began a chapter of systematic waterworks, stabilizing the riverbanks with massive amounts of rock and constructing higher dikes for flood protection.

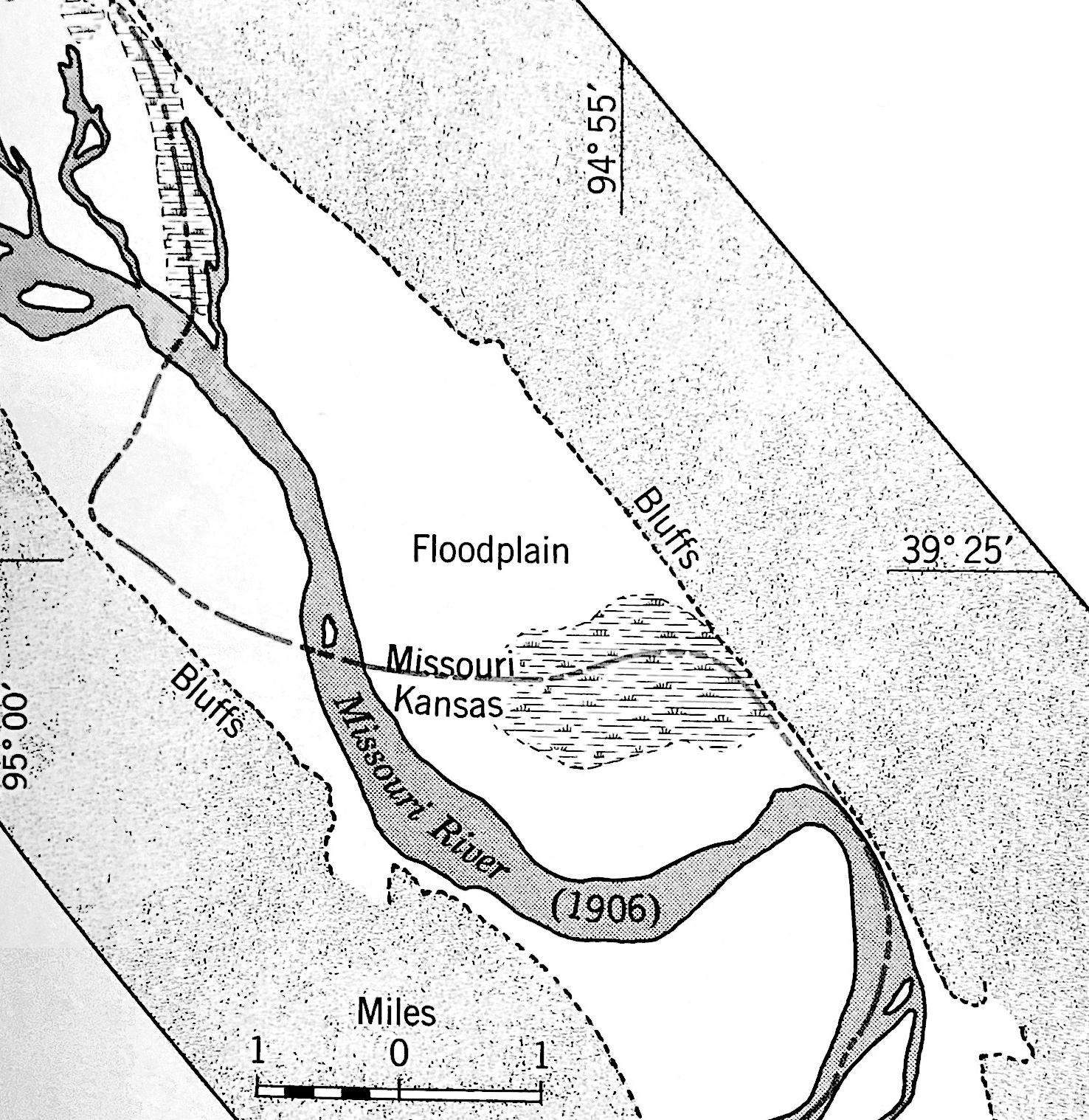

Shifts in geopolitics and the expanding demands of water engineering gradually reshaped the river. The First World War dissolved the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and in 1920, a border was drawn along the Danube. The south-west side of the river kept the name Hungary, and the other side was given to a new nation Czechoslovakia. By that time, much of the river’s course had already been dredged and straightened.

Yet the most dramatic change was still to come.

In the 1950s, after the suffering and destruction of the Second World War, like many nations, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic and the Hungarian People’s Republic sought a swift recovery. Rebuilding what had been lost was not enough—they dreamed of a brighter, faster, and more progressive future. Large-scale infrastructure promised both economic growth and a boost to national morale. Looking to the Danube between them, they saw an opportunity: two jointly funded dams that could improve flood control, enhance navigation, and generate hydroelectricity.

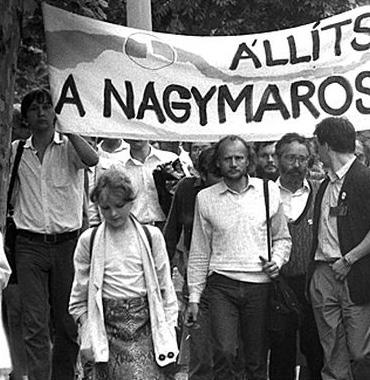

The project was originally called Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros, named after the two towns—Gabčíkovo in Czechoslovakia and Nagymaros in Hungary—where the hydroelectric dams were to be built. The plan alarmed ecologists in Hungary, who, together with the general public, protested for years. Ultimately, Hungary withdrew from the agreement, and nothing was ever built at Nagymaros.

Around the same time, on the other side of the river, Slovakia was completing its Velvet Divorce from the Czech Republic. For the first time in history, Slovakia would appear on the world map as an independent nation. To them, the Dam became a symbol of international recognition and national pride

The Danube’s ecological wetland within Hungarian territory would still suffer severely if Slovakia continued construction. Yet there was little Hungary could do, as the entire dam now lay within Slovak borders.

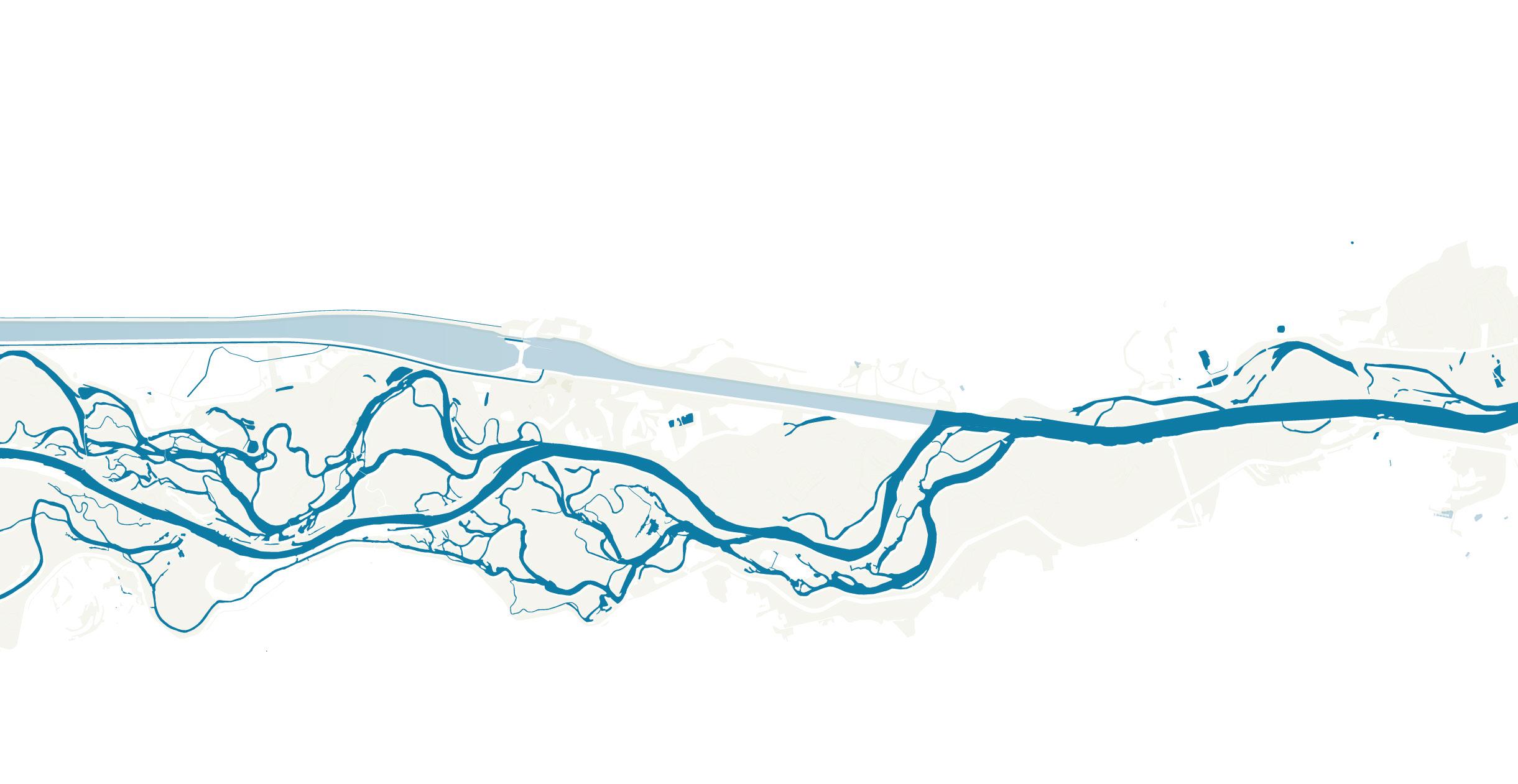

In 1992, after the dam was put into operation and diverted the majority of the Danube’s flow, the once free spirited, intricate labyrinth river streams were drained in a matter of days.

Fig.8 Changesofthemainarm:1991 beforethediversionoftheriver,October1992 afterthe diversionoftheriver,2009 progressofterrestrialvegetationonthedryriverbed

At the same time, the Dam raised Bratislava’s water level. Combined with the effects of climate change, in 2024—32 years after the Dam began operation— the capital was hit by the biggest flood in three decades.

To this day, no study has compared the profits of the electricity generated with the costs of maintaining the Dam, the losses to the ecosystem, the expenses of flood repairs, and the known and unforeseen consequences of changes in groundwater levels.

One study was published in 2010. Experts from both Slovakia and Hungary joined forces to explore the feasibility of rehabilitating the Danube while maintaining the Dam’s functions. The short answer from the 300-page report was : ‘not feasible.’

In other words, to restore the river’s habitat, the dam must “go“.

What if the Dam were removed—or at least stopped operating?

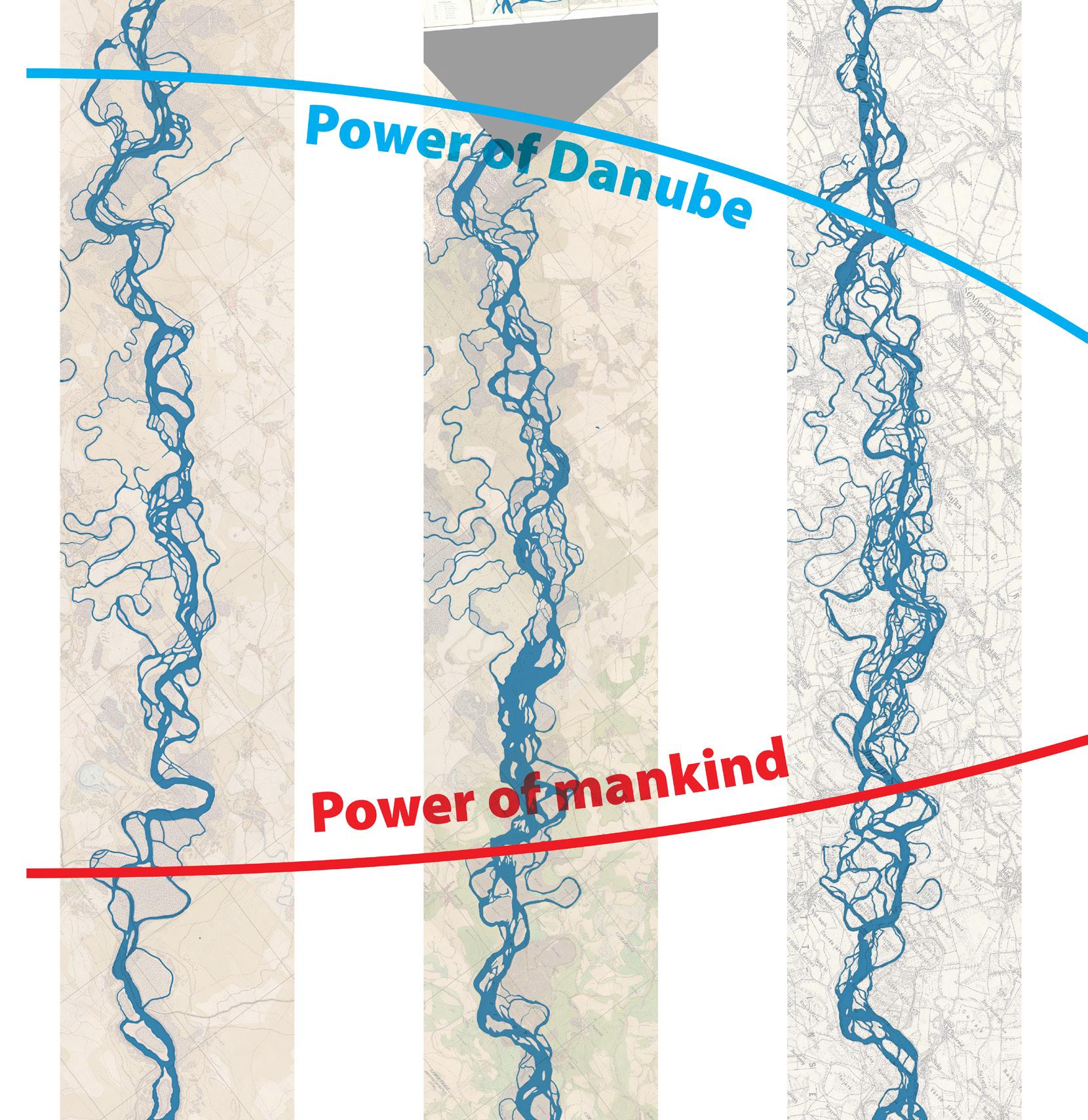

Over the years, among the political turnovers and ambitious water engineering projects, the power of the Danube has been largely diminished. Last year’s flood in Bratislava is just one of its consequences.

What if, in an alternative universe, this flood became a turning point in how Slovakia and Hungary perceive the Dam, the river, and their relationship?

In this imagined scenario, the two nations recognize that the key to their own sustainable future is a healthy river, one with enough water to flow freely. Therefore, the Dam must be stopped, and space must be granted.

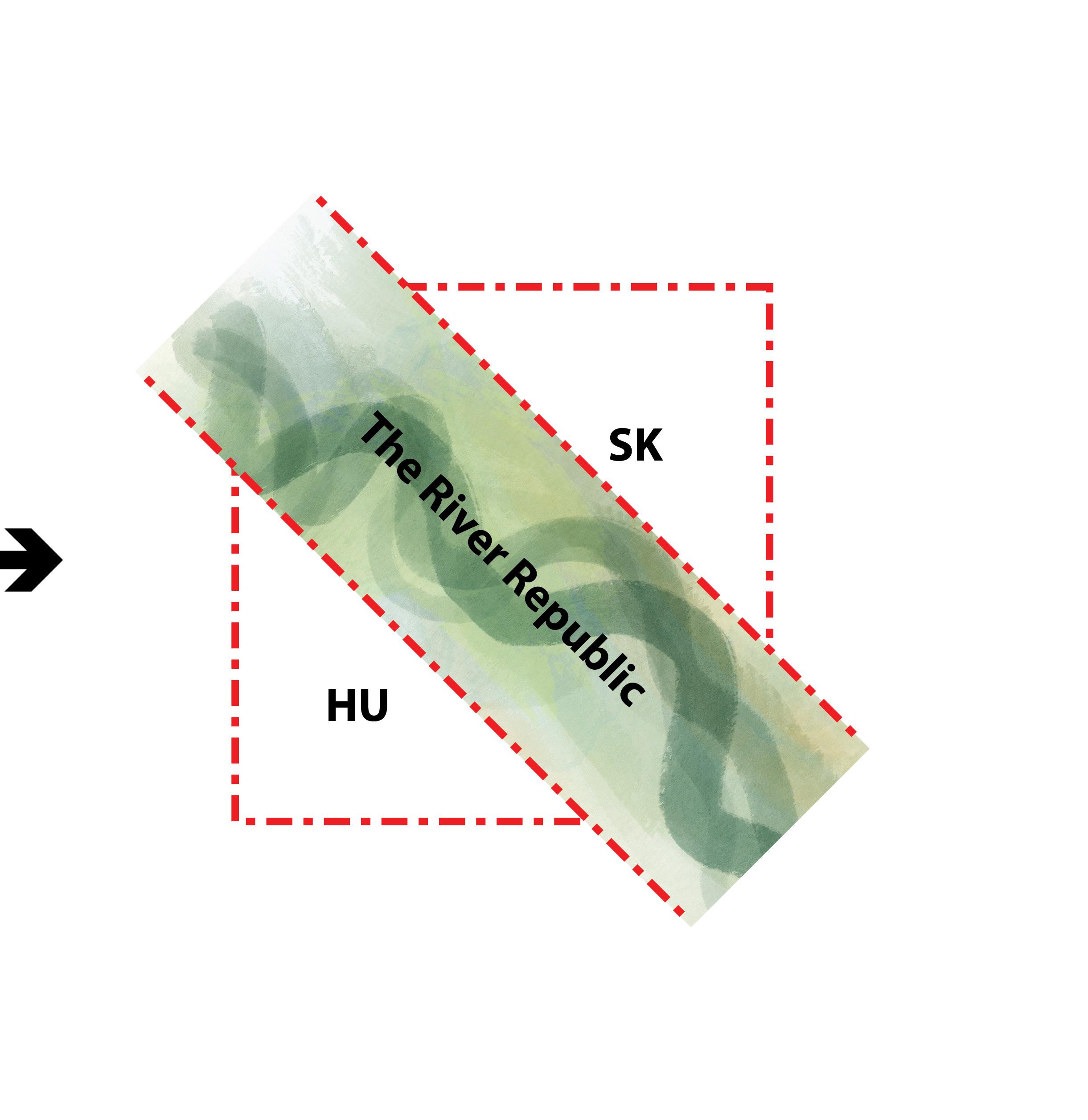

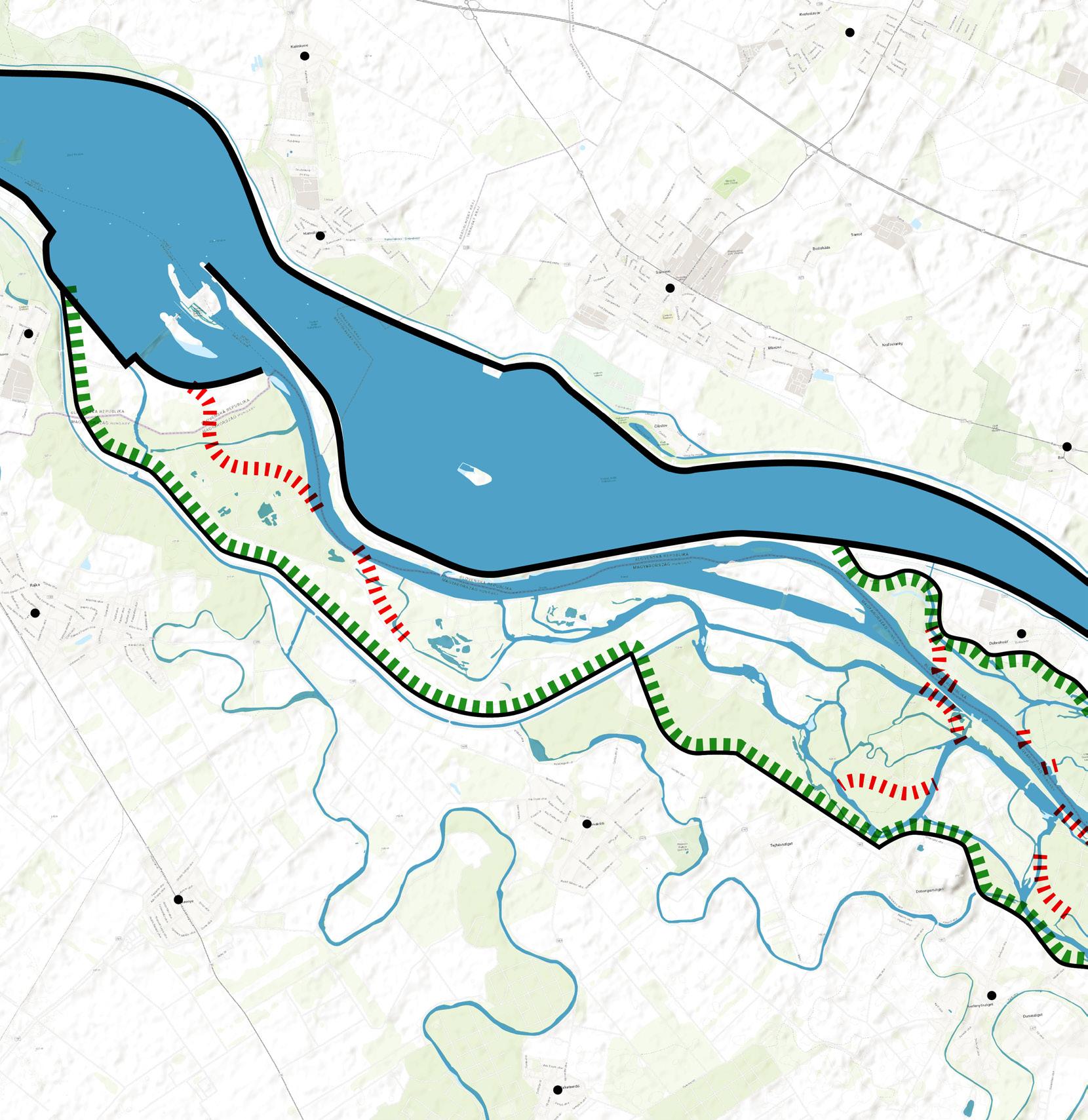

To maximize the river’s future health and rights, the border is re-drawn. The traditional single-line boundary becomes a new region—a territory claimed by the river itself, named “the River Republic.”

To ‘remove’ the Dam, we first need to understand how it functions.

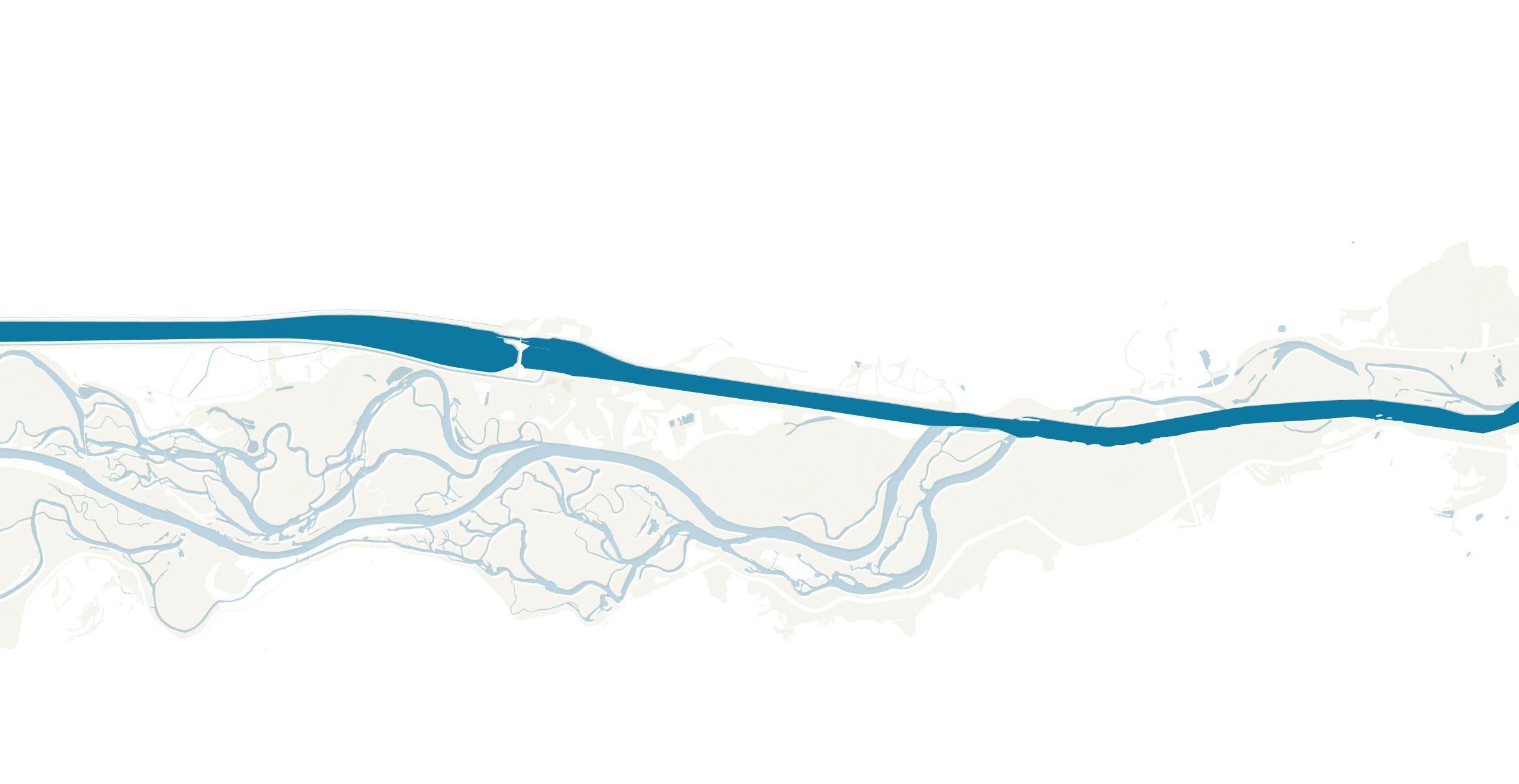

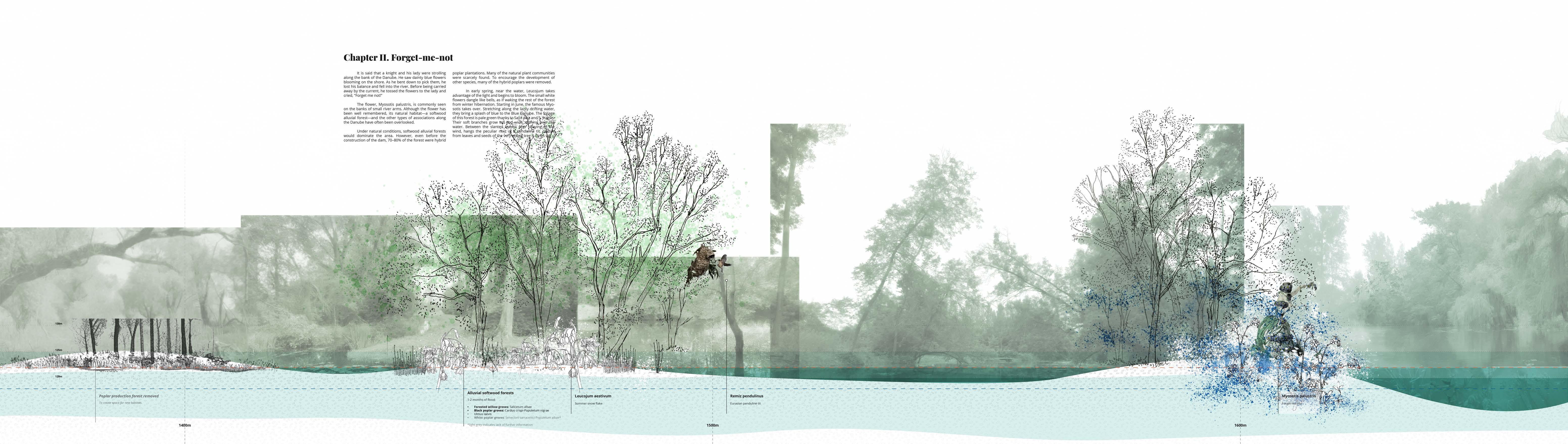

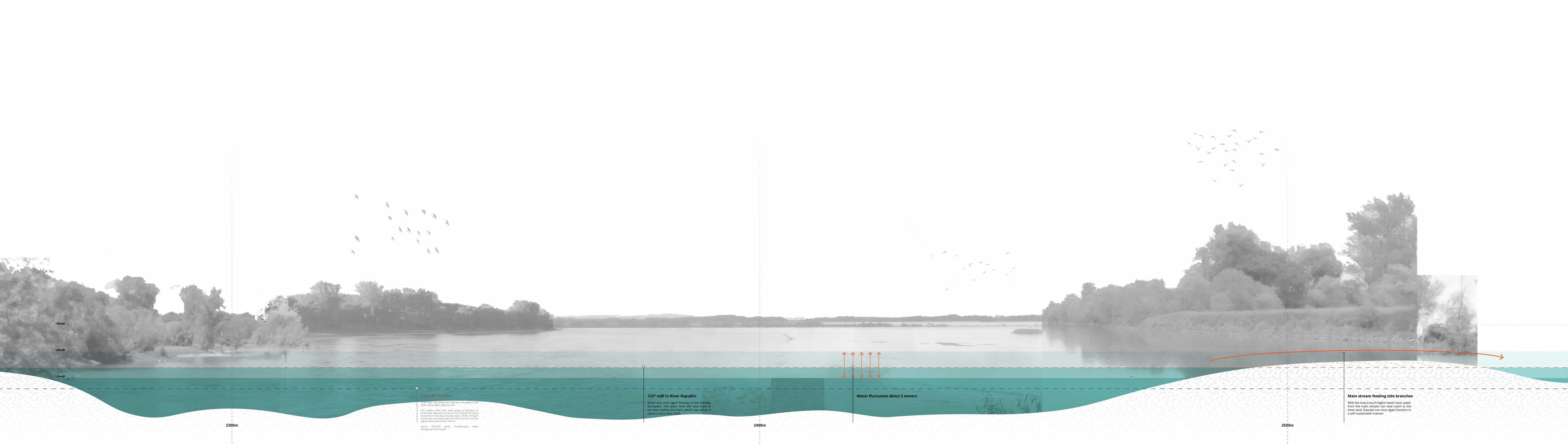

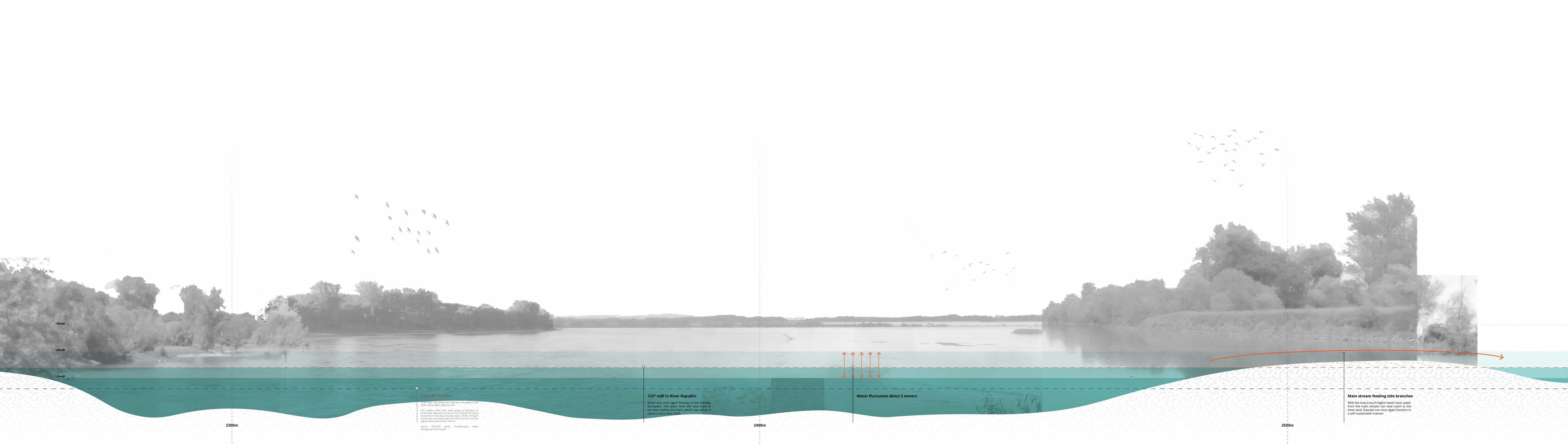

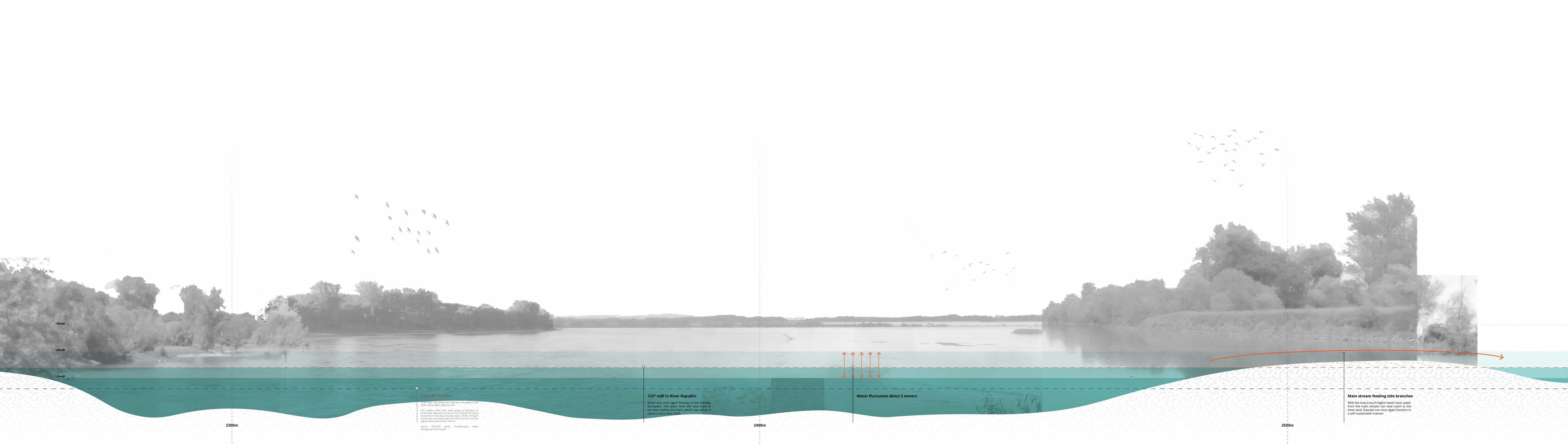

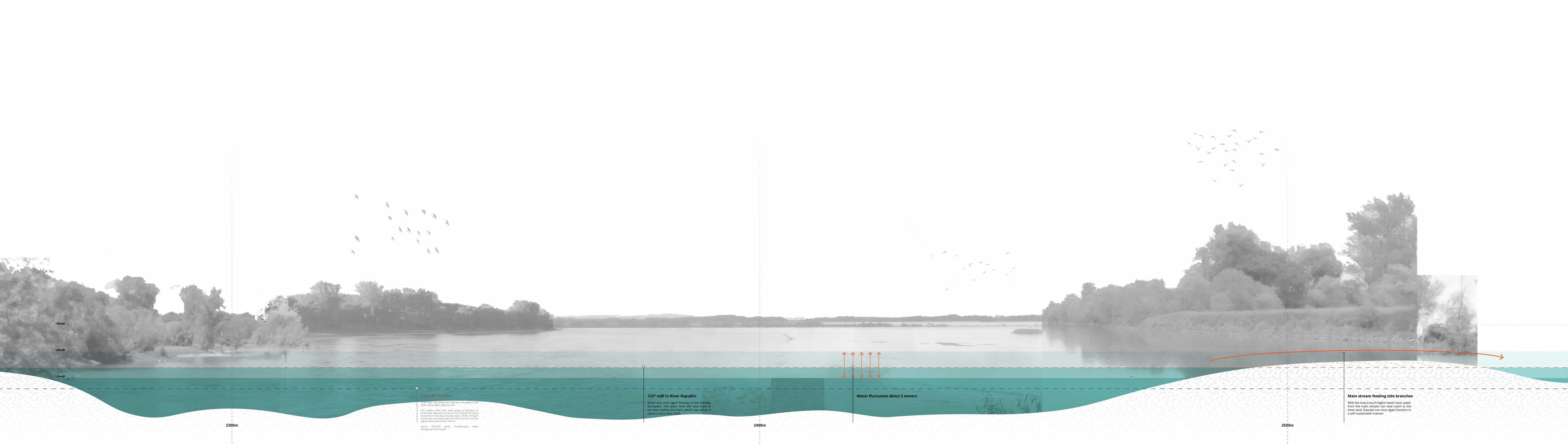

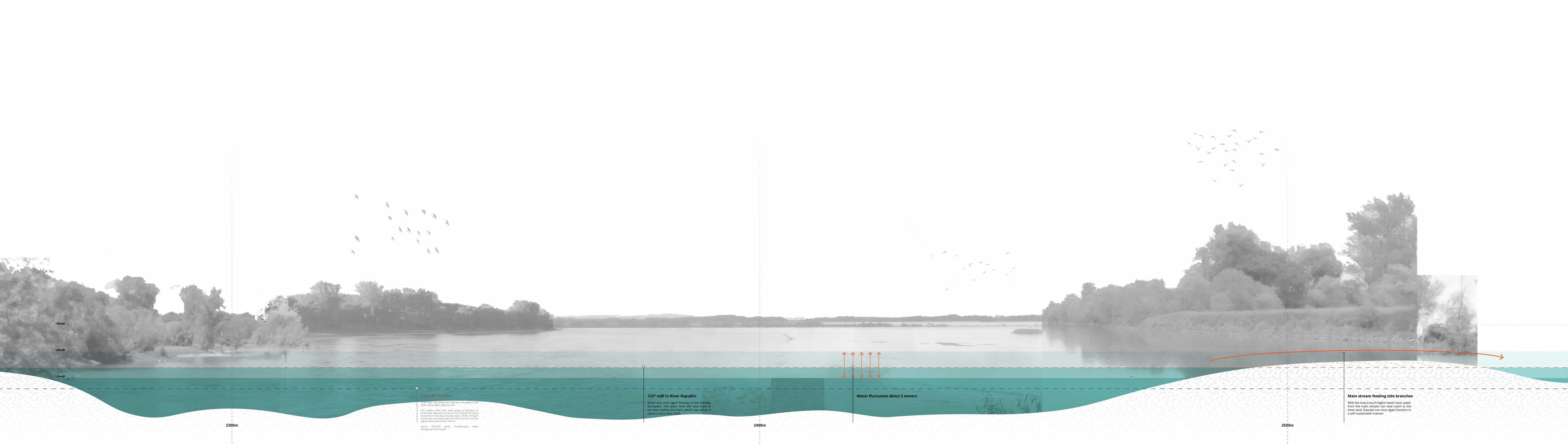

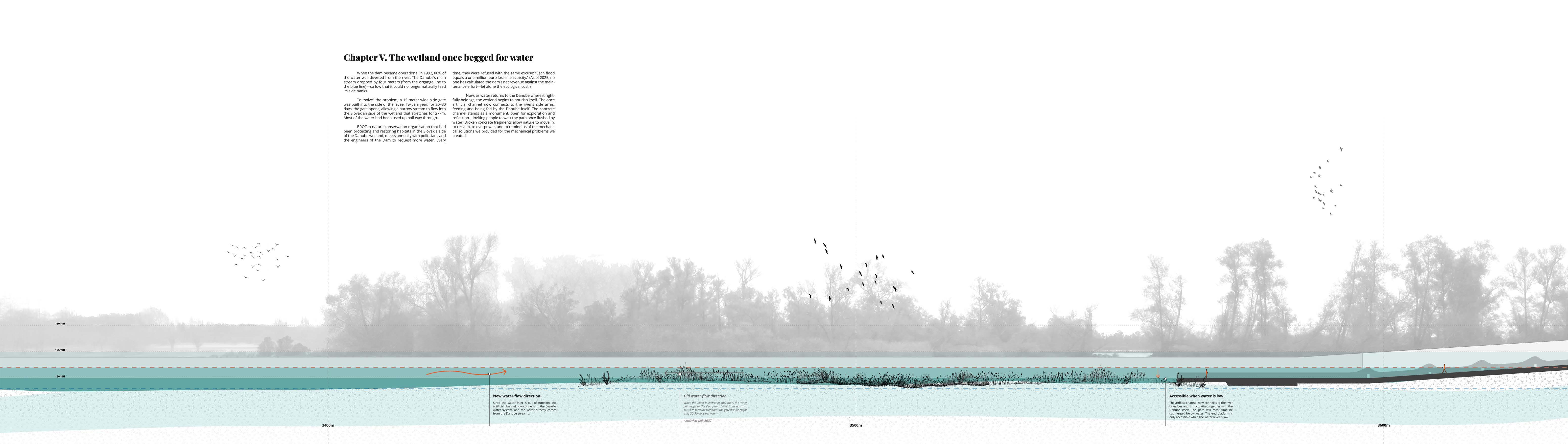

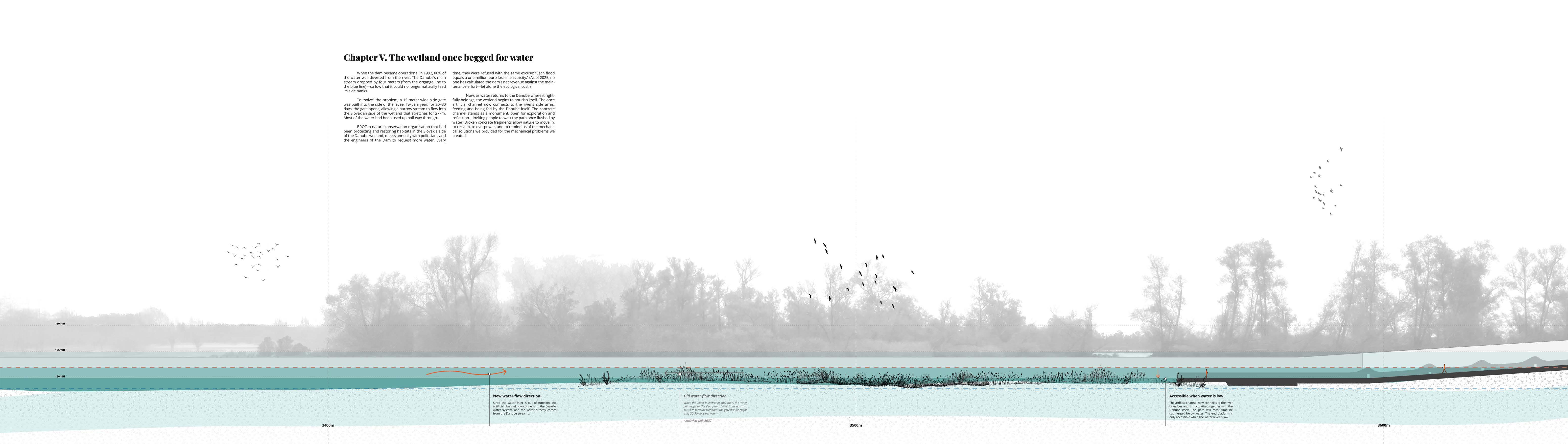

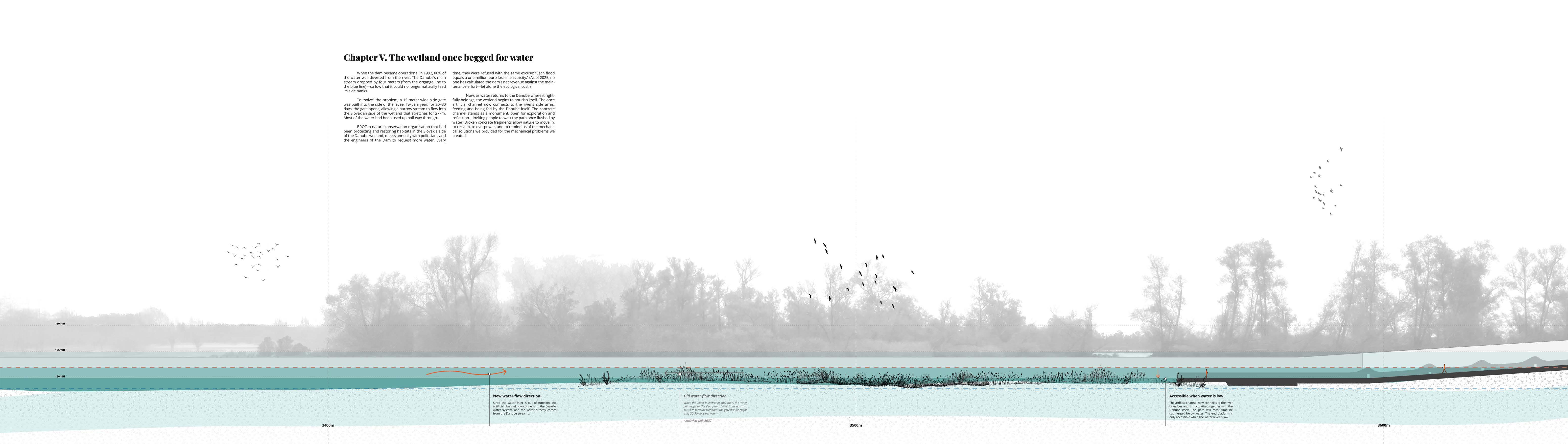

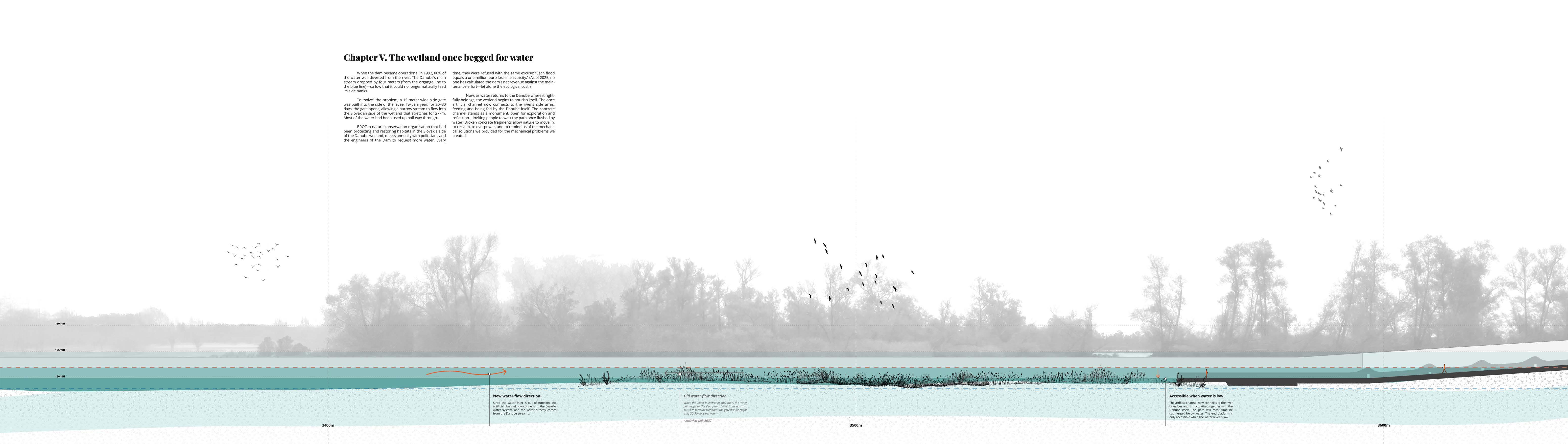

Before the dam was built, the Danube had already lost its braided pattern, flowing instead as a clear main stream. While it was not in a fully ‘natural’ state, it still carried enough water to sustain its side branches.”

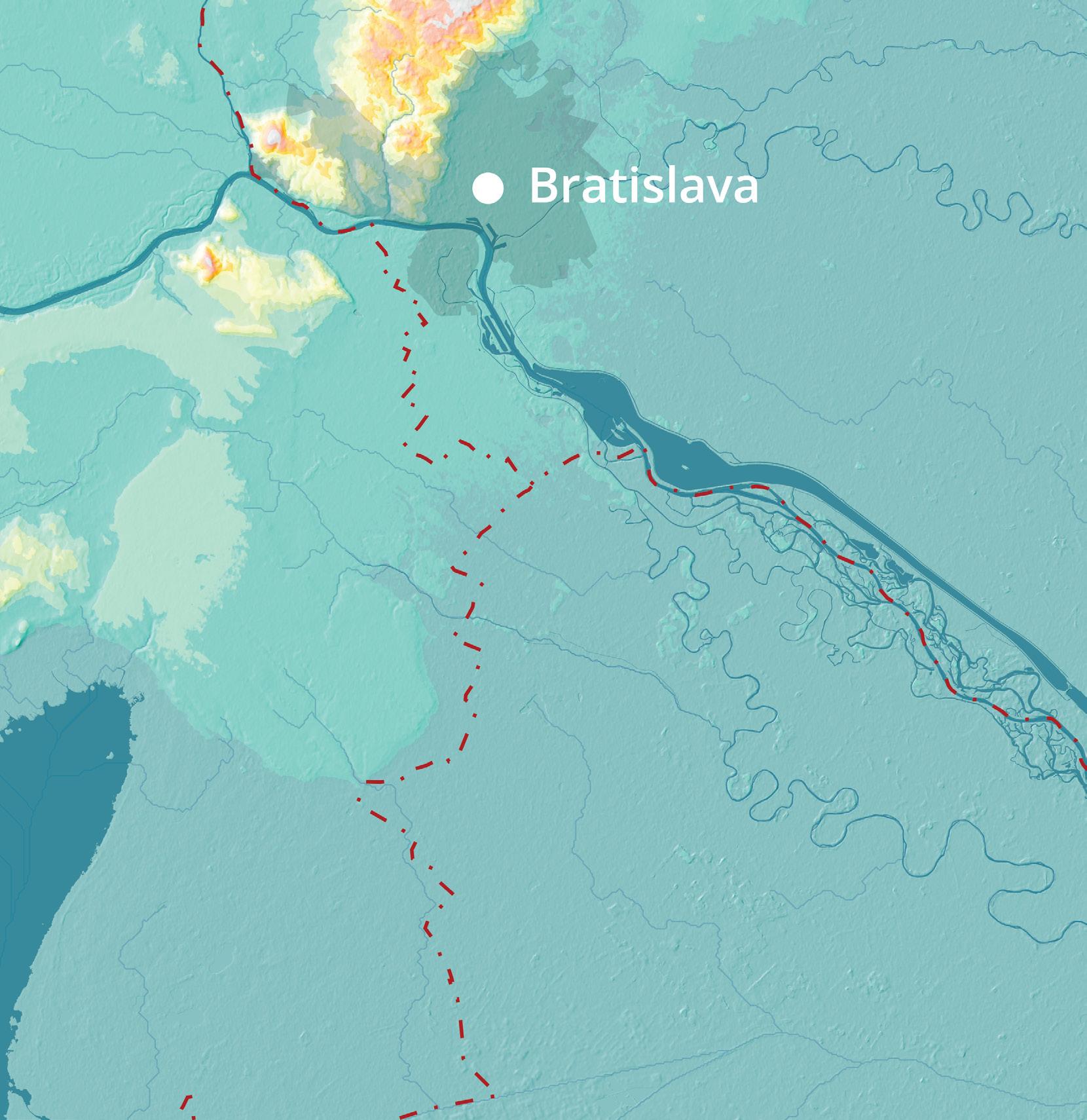

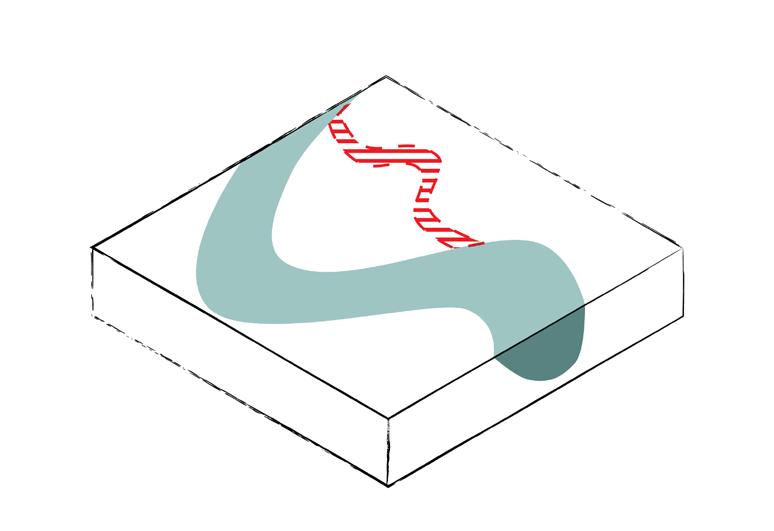

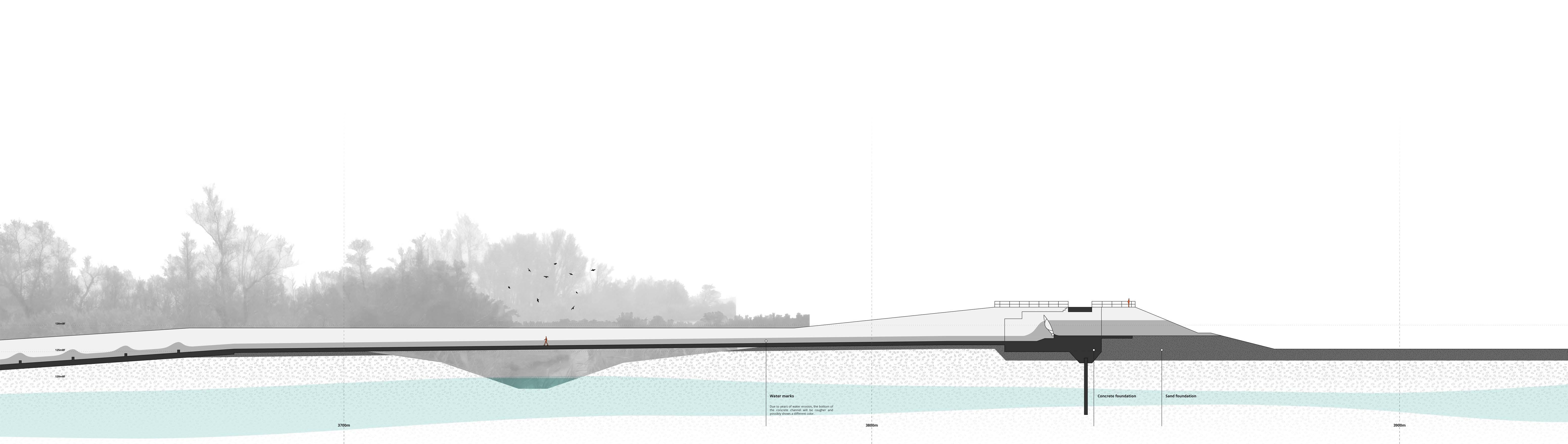

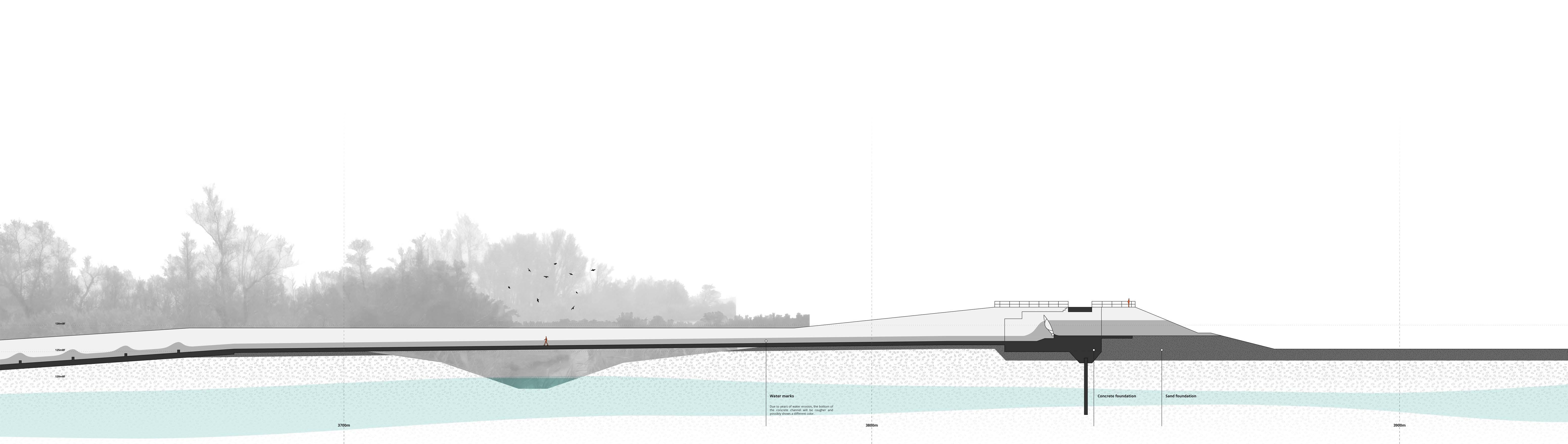

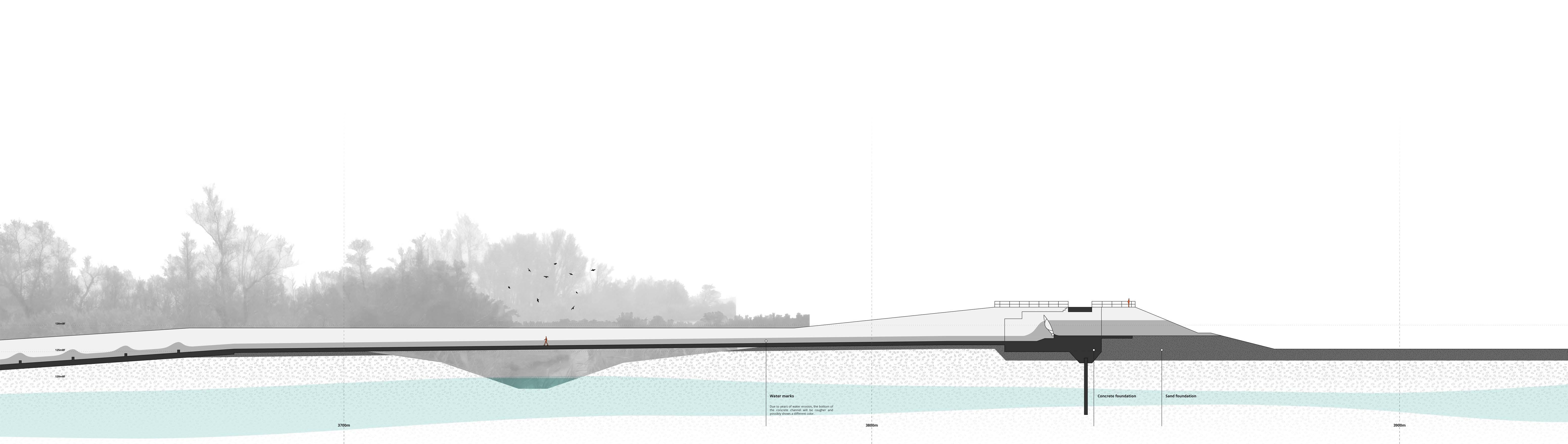

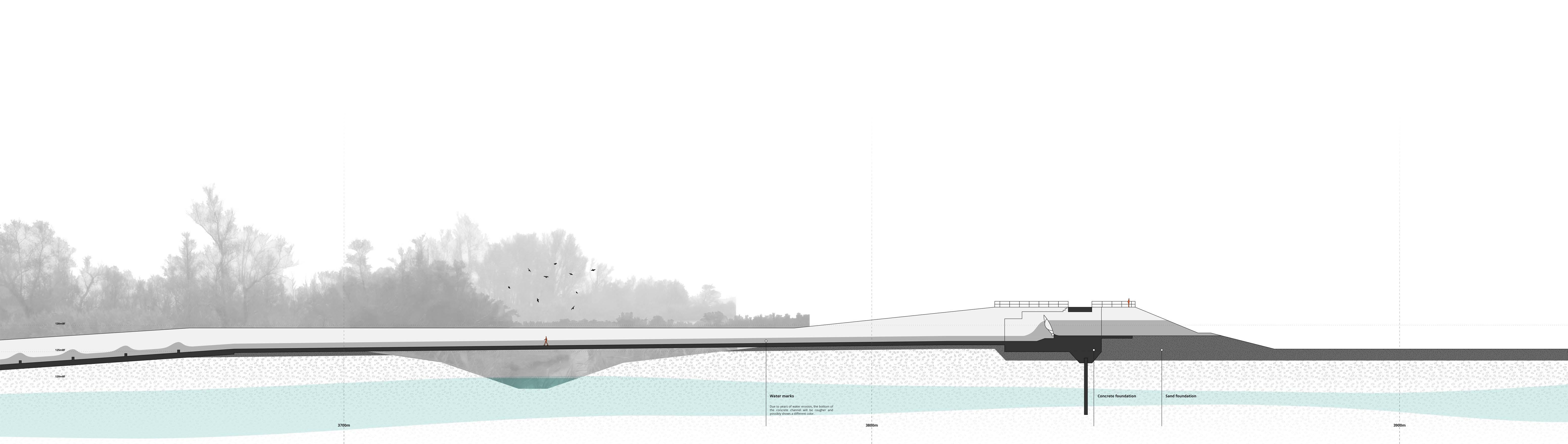

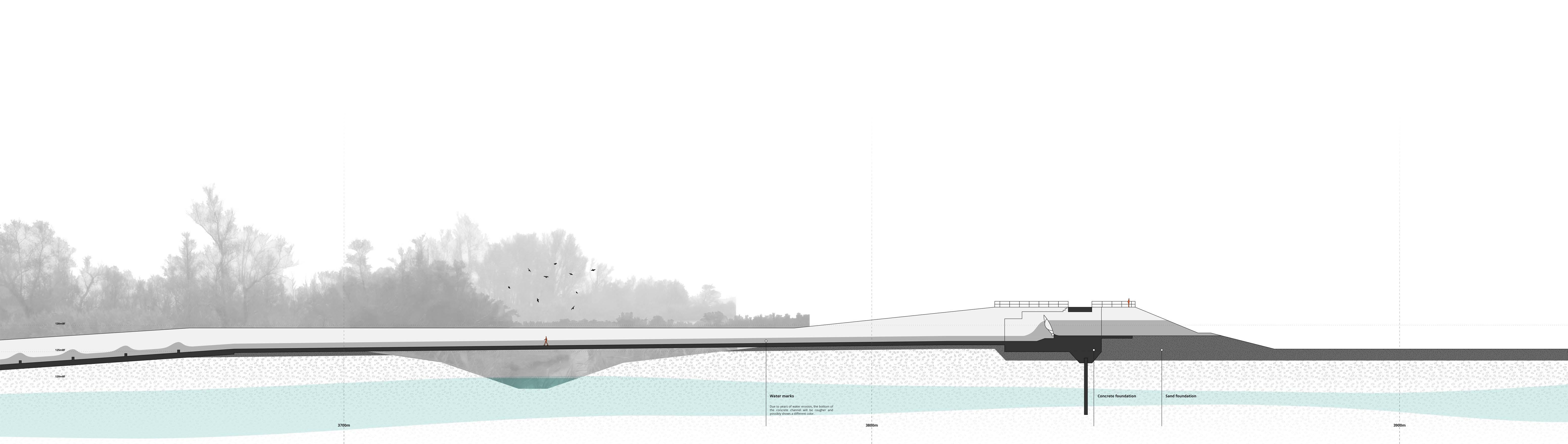

To harvest hydroelectricity on flat land, an artificial drop in height must be created, which in turn requires the construction of a system of reservoirs and levees.

At Hrušov, a reservoir was created to slow the water’s flow. A small dam at Čunovo was built to allow only 20% of the water to enter the Danube, while generating a modest amount of electricity.

The remaining 80% of the water travels through a 27-kilometer-long supply channel, drops 20 meters at Gabčíkovo, generate electricity, and then rejoins the Danube.

water supply channel

27km

The Gabčíkovo Dam is the largest hydroelectric plant in Slovakia. As of 2025, it supplies about 8% of the country’s electricity. Last year, Slovakia approved plans for a new nuclear reactor, which could potentially provide twice that amount of power. In this project, I assume that both current and future electricity demand can be met by this nuclear plant.

270m 540m

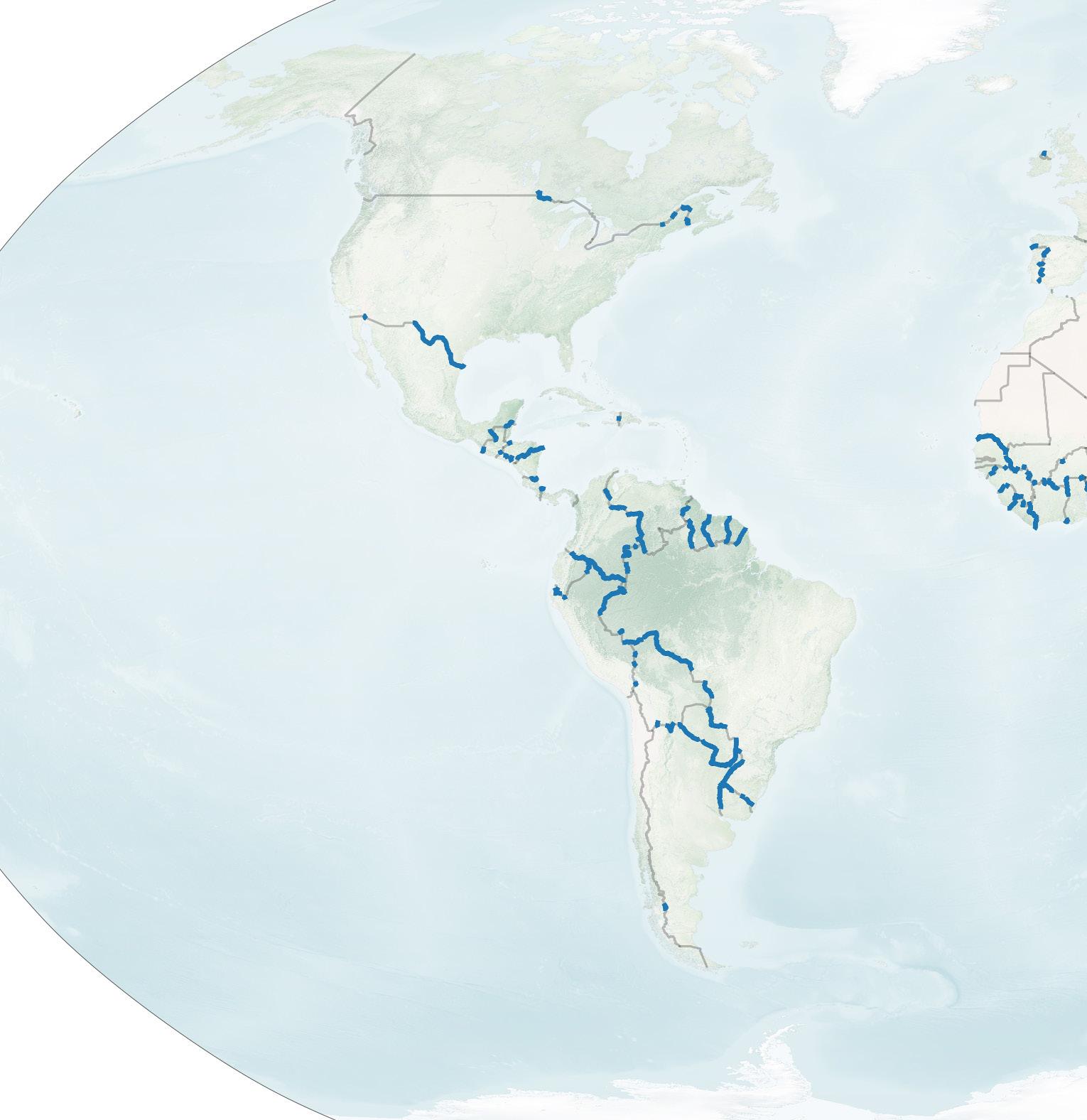

Inspired by successful river lawsuits in Colombia and New Zealand, the Earth Law Center, a U.S. based organization, drafted a Universal Declaration of River Rights in 2020, identifying six fundamental rights of a river:

We can also interpret a healthy river as one that fulfils all six of the criteria. At present, the Dam has deprived the Danube of nearly all of these rights.

ecosystem

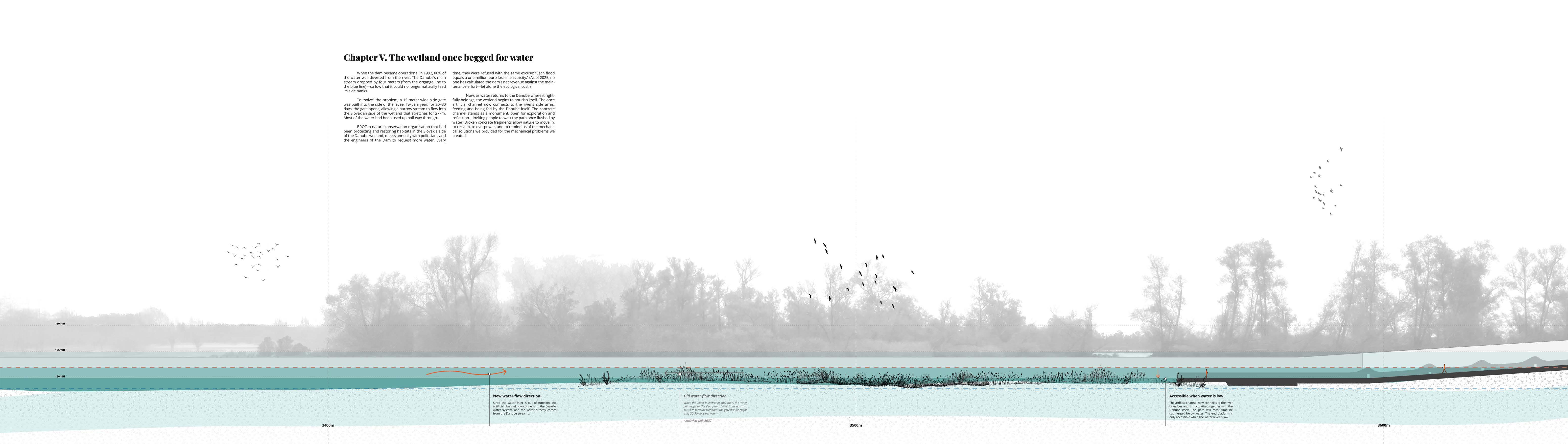

The current 20/80 water distribution needs to change in order for the Danube to be healthy again. This project is not about simply recreating the ‘good old days’ or erasing the Dam entirely from the map. It is also about acknowledging what the Dam represents: a decision made at a specific moment in history. Therefore, instead of returning 100% of the water to the Danube, I propose leaving 10% of the water within the levees to create new spaces.

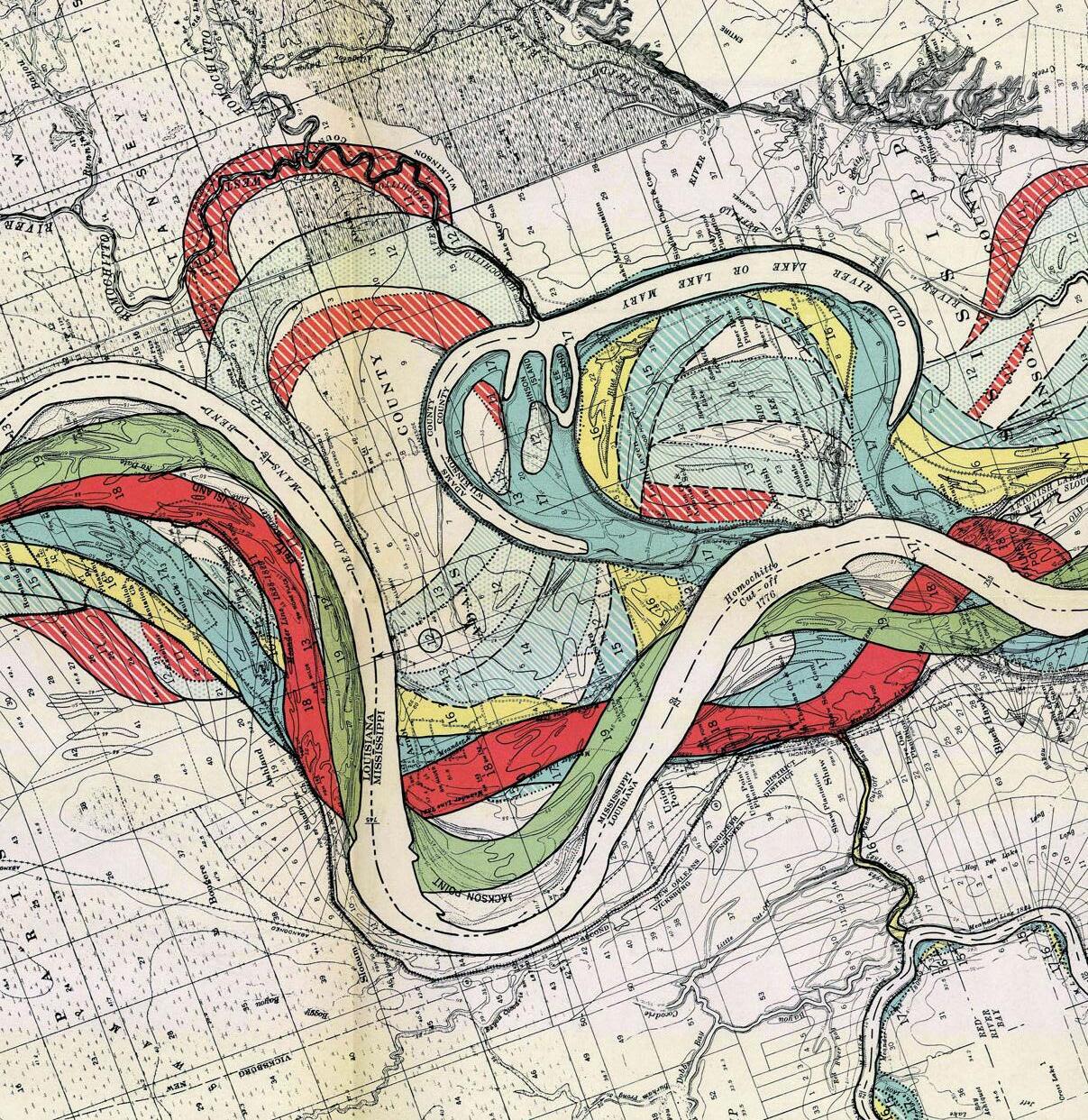

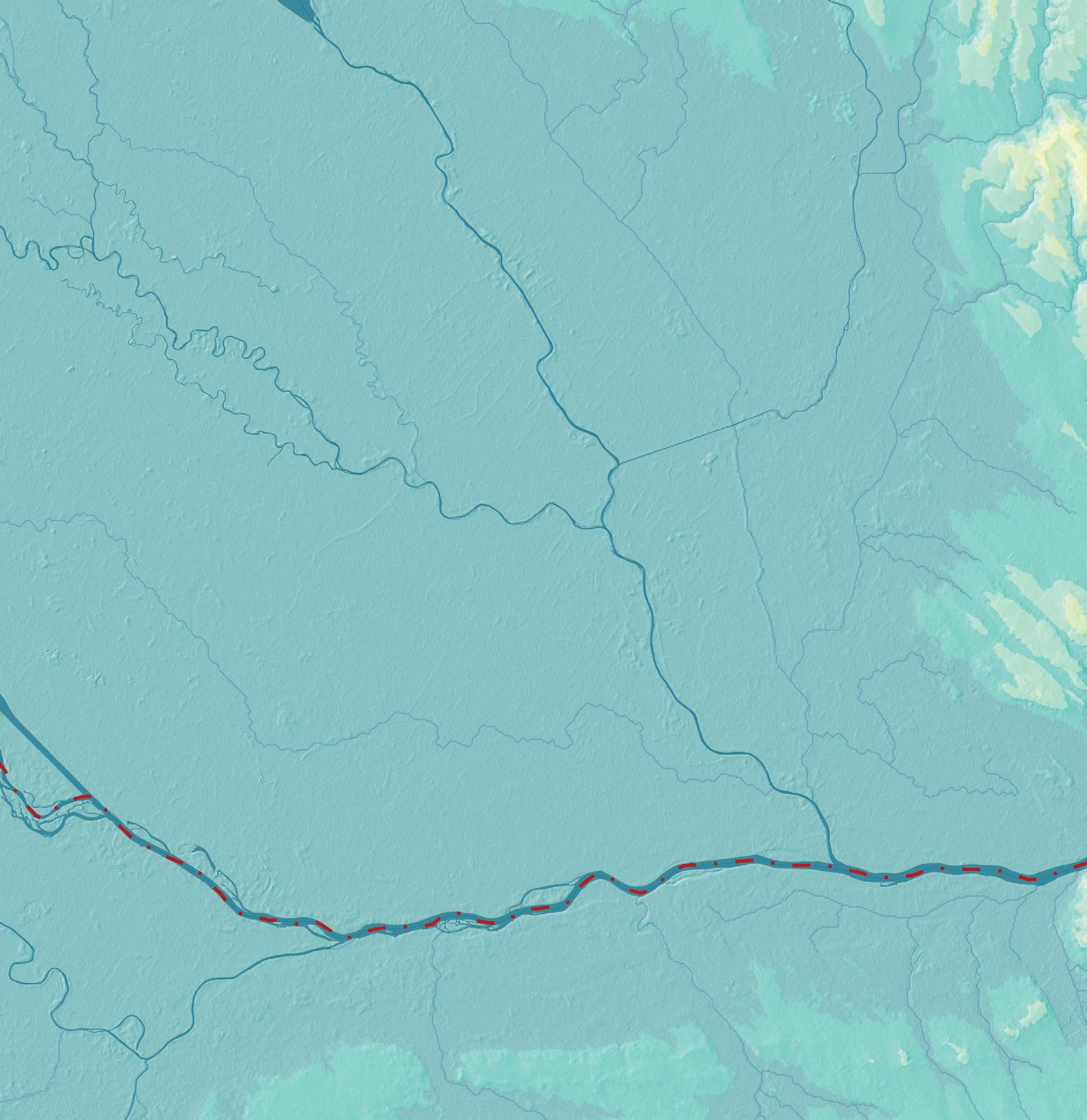

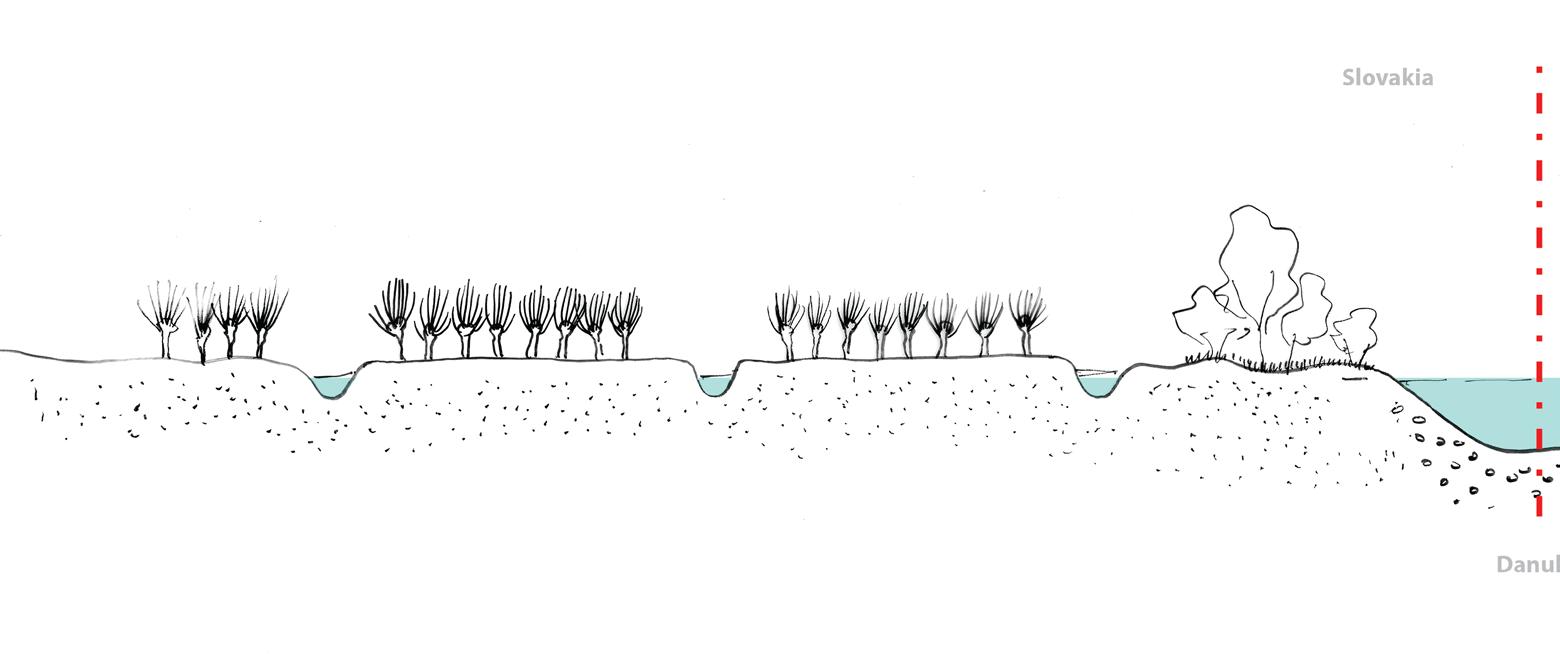

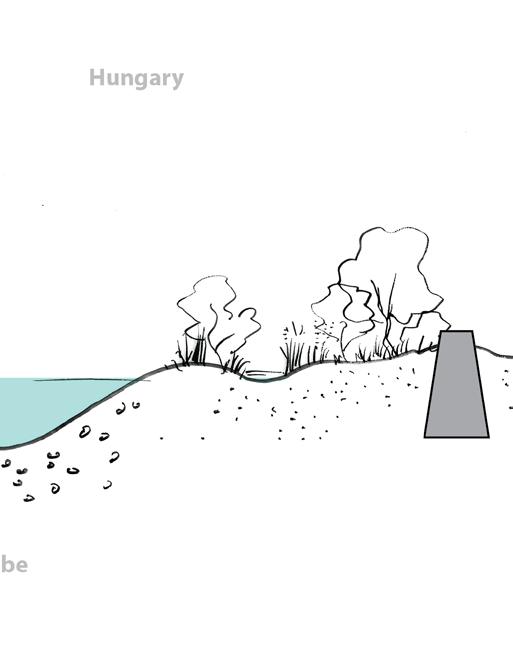

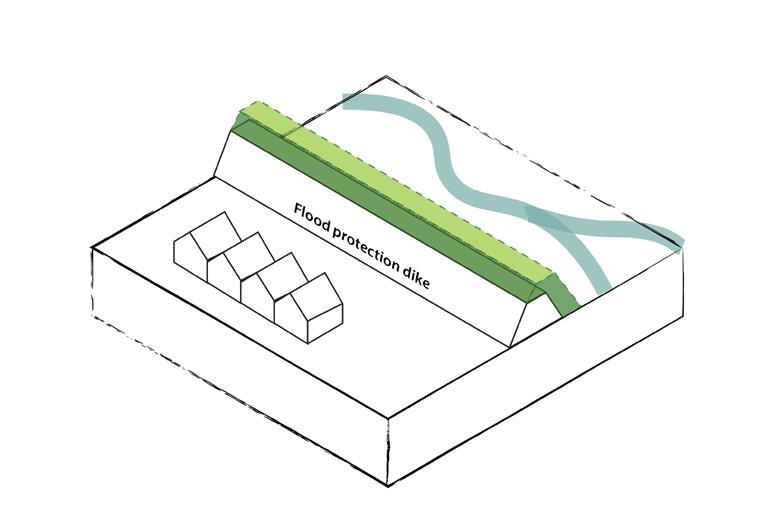

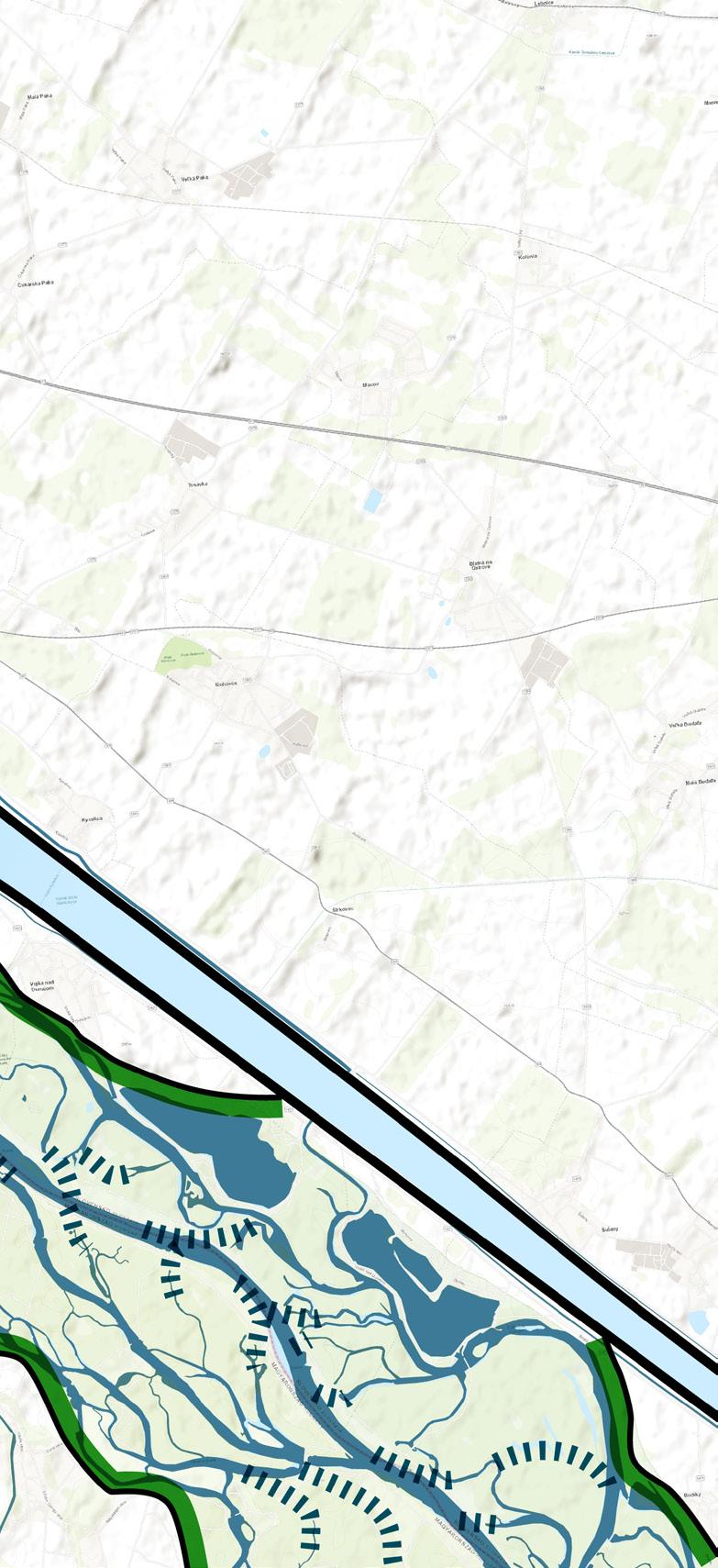

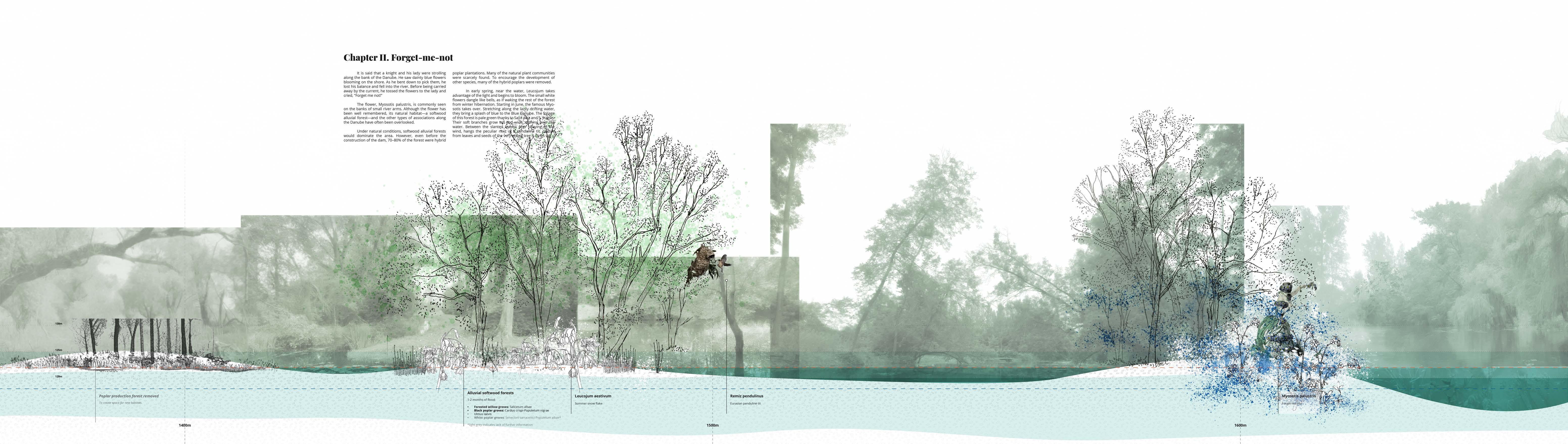

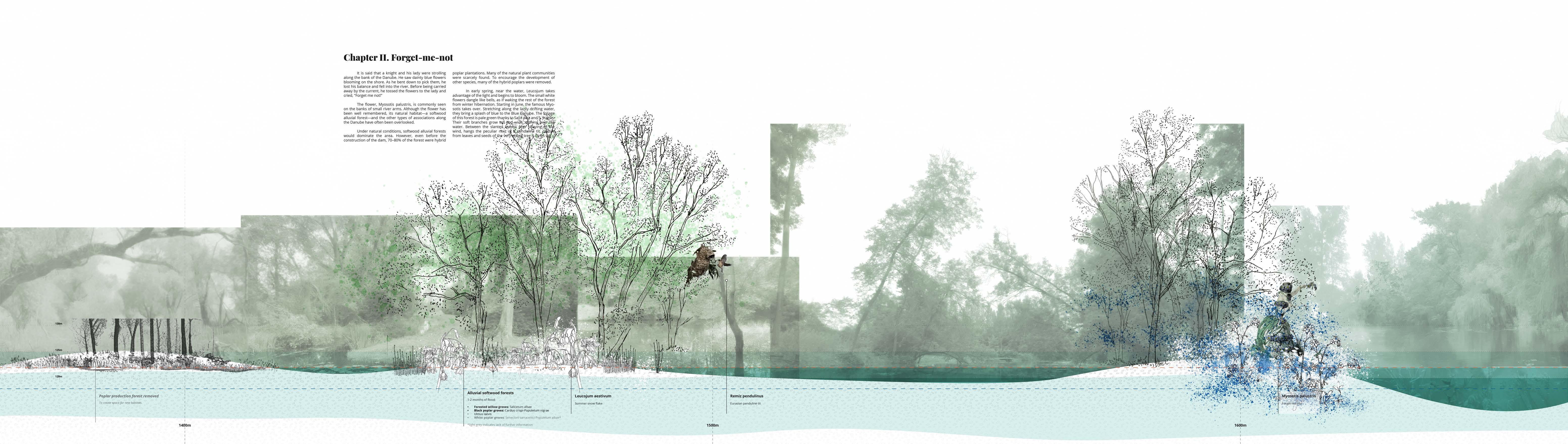

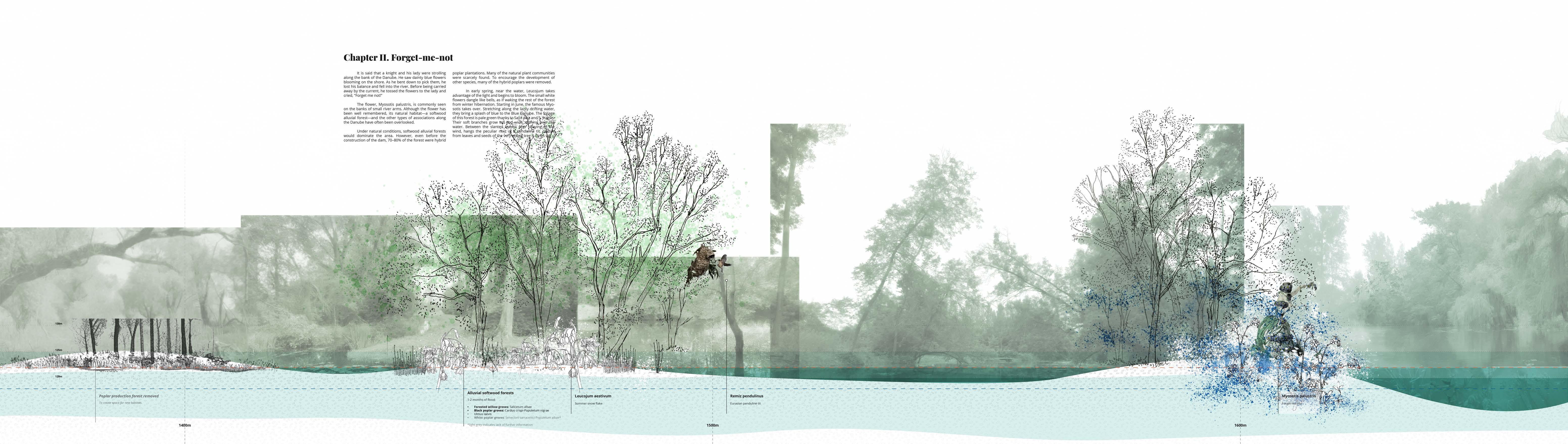

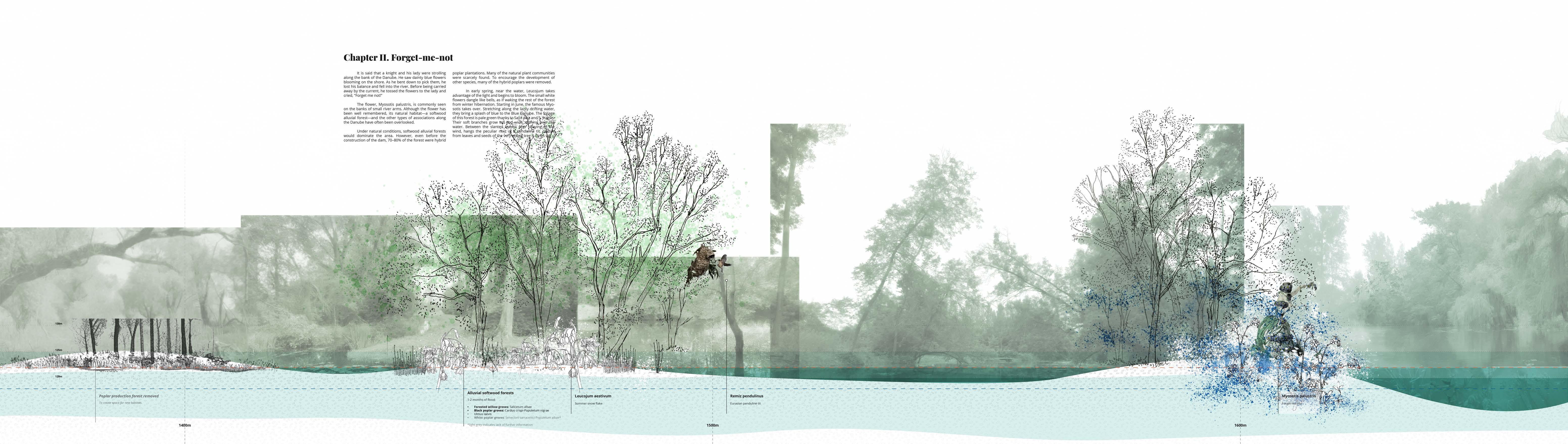

With the new water allocation, the river requires a larger space. By overlaying historical river courses from the past 300 years, it becomes clear that the area between the flood protection dike in Hungary and the outer levee of the Dam in Slovakia can provide the Danube with sufficient space to flow.

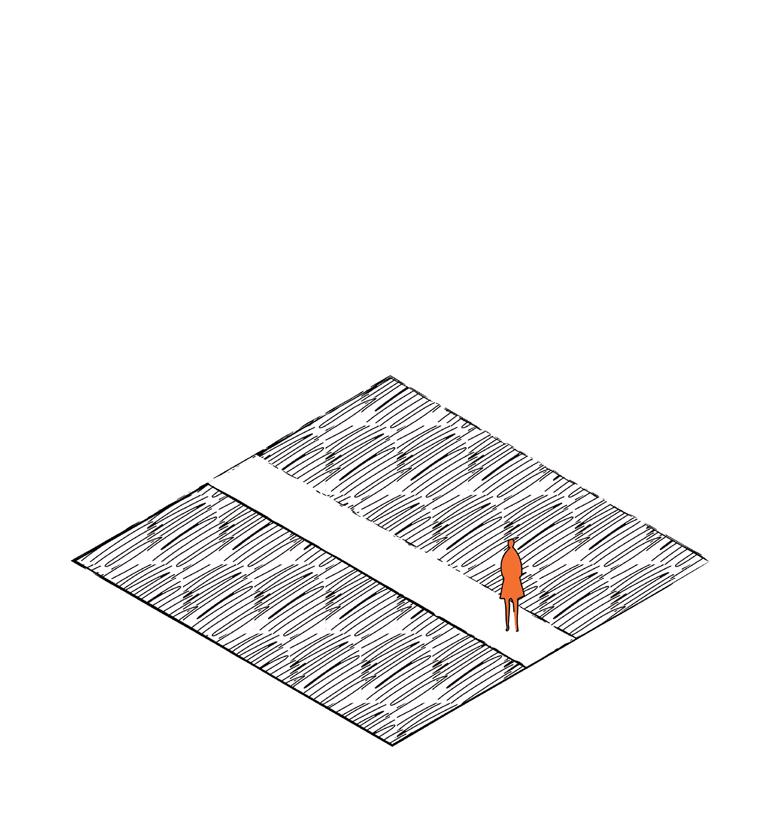

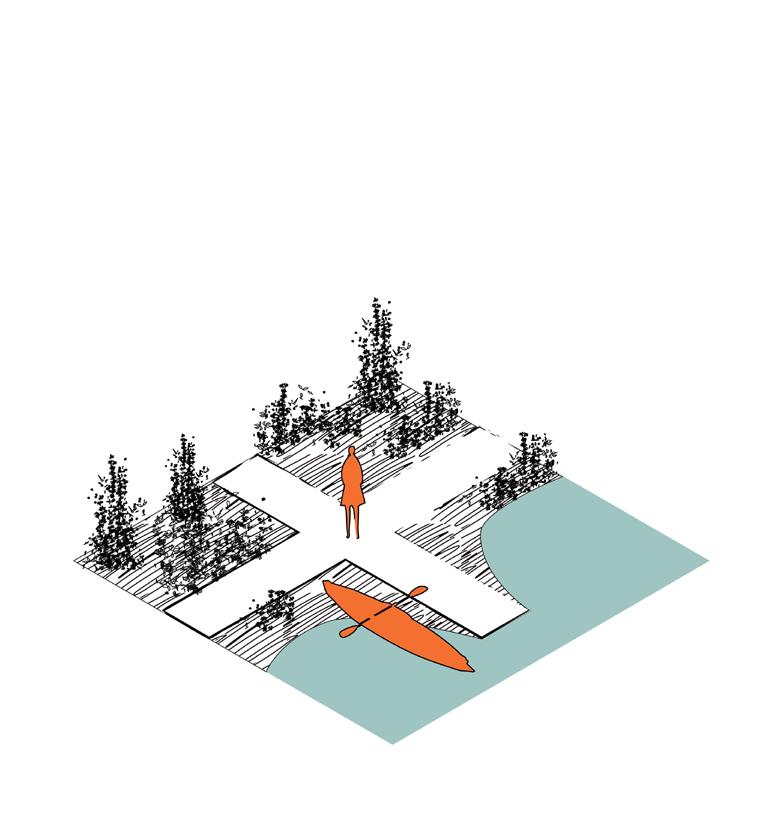

These two existing physical barriers would then define the edge of a new, independent territory: the River Republic, where the Danube and its alluvial ecosystem are the rightful owners and the river’s six rights are guaranteed. The River Republic encompasses not only the Danube’s floodplain but also three Slovakian villages, which, together with their Hungarian counterparts, serve as human representatives of the area—tasked with observing and protecting the land.

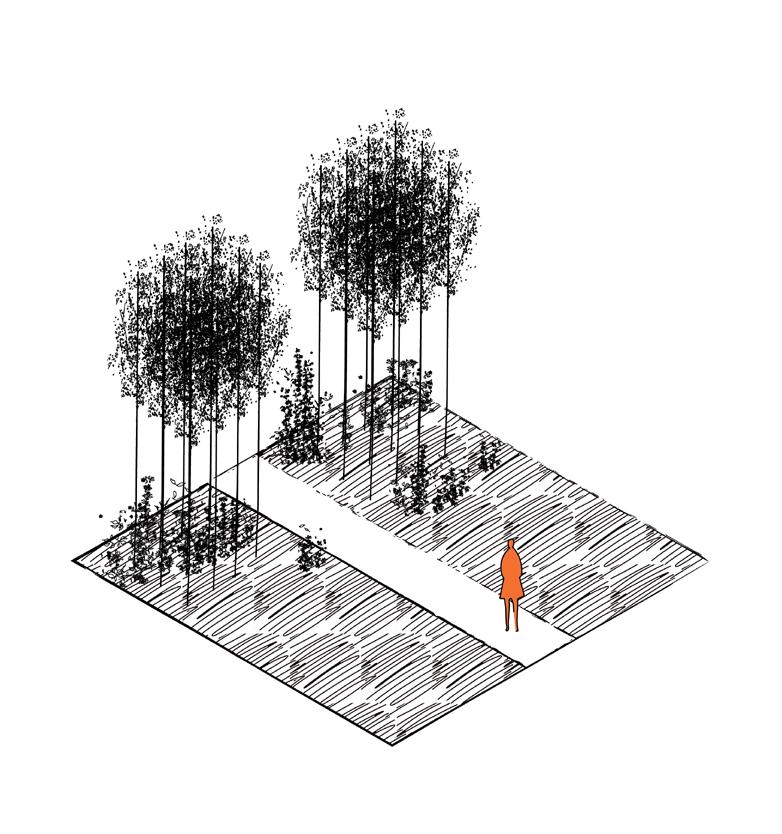

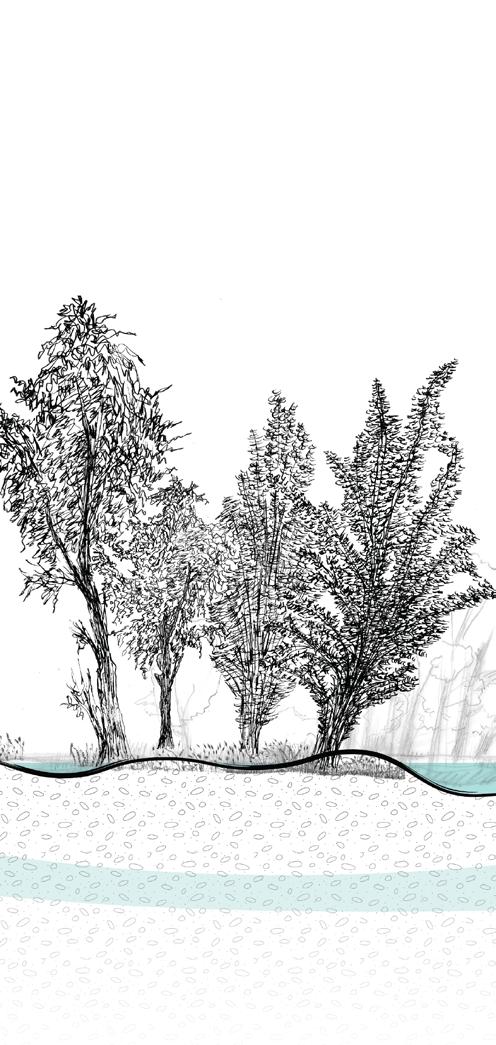

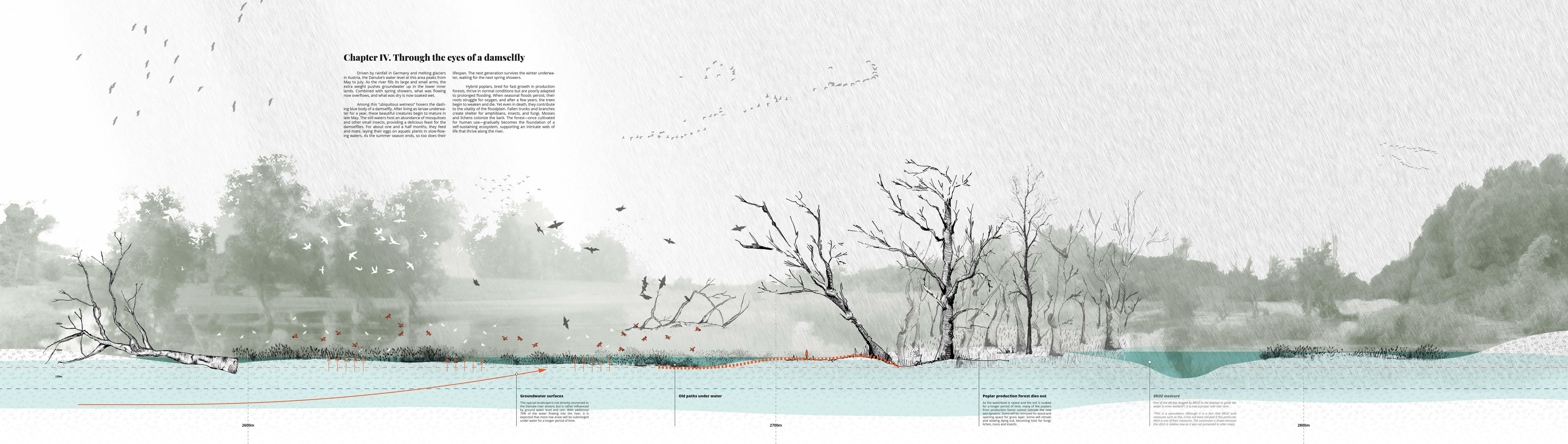

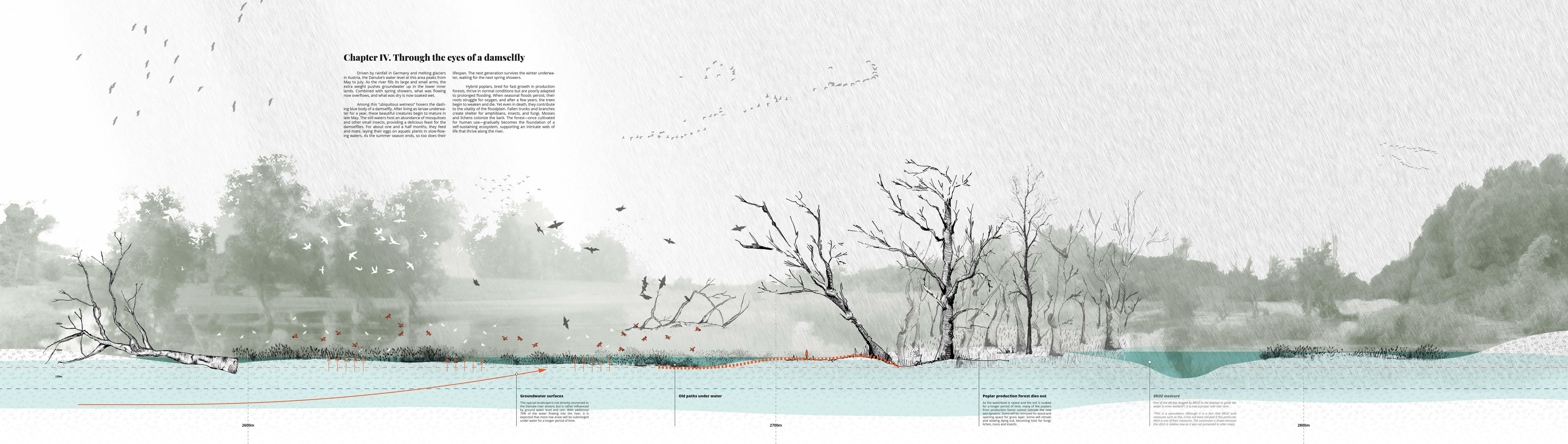

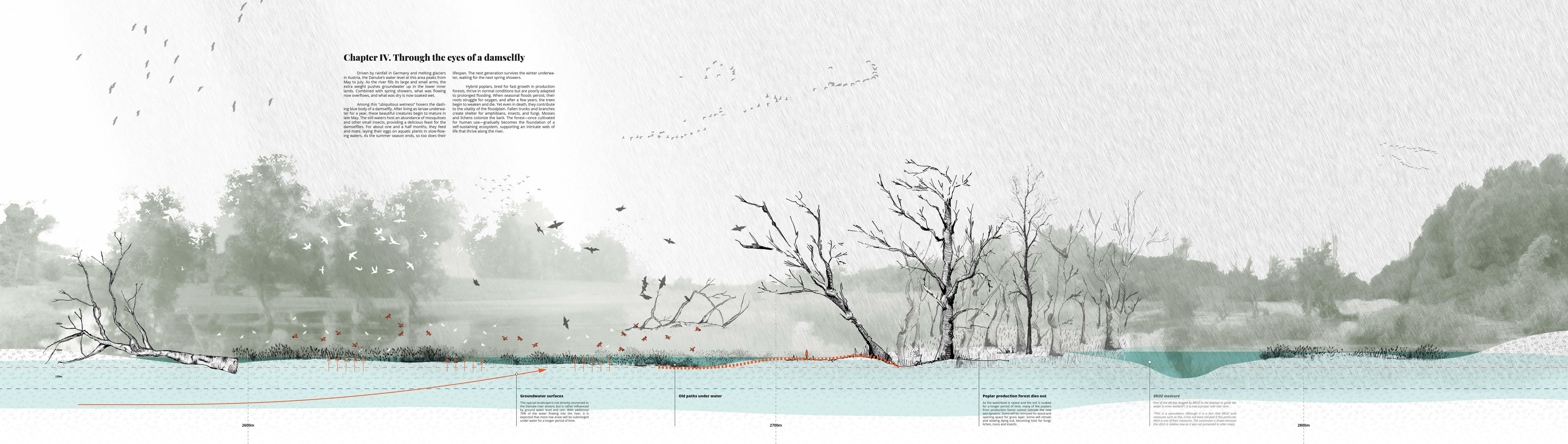

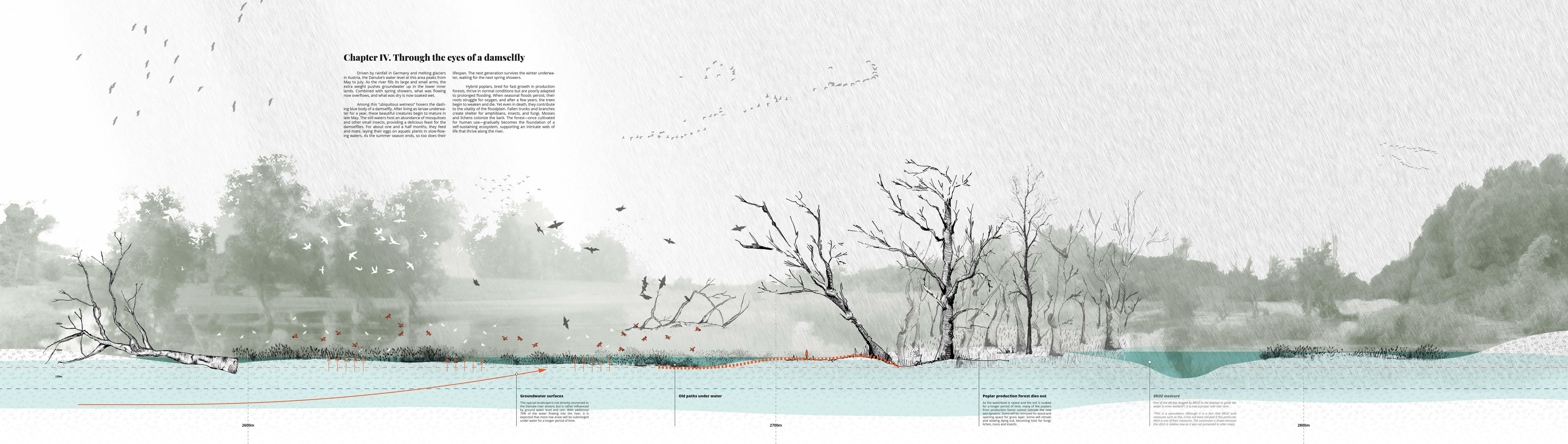

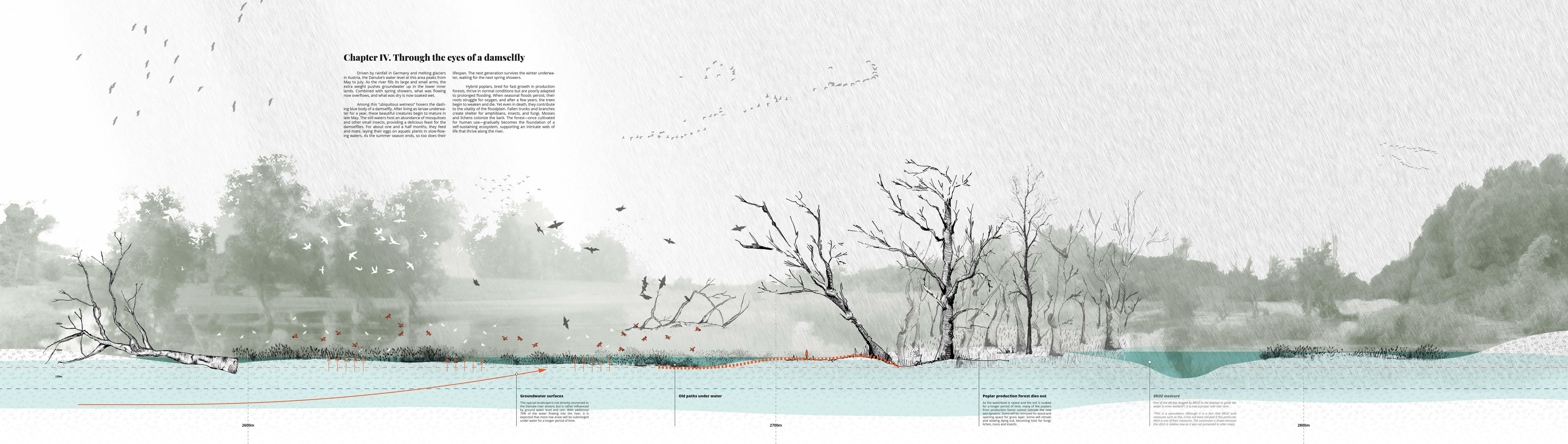

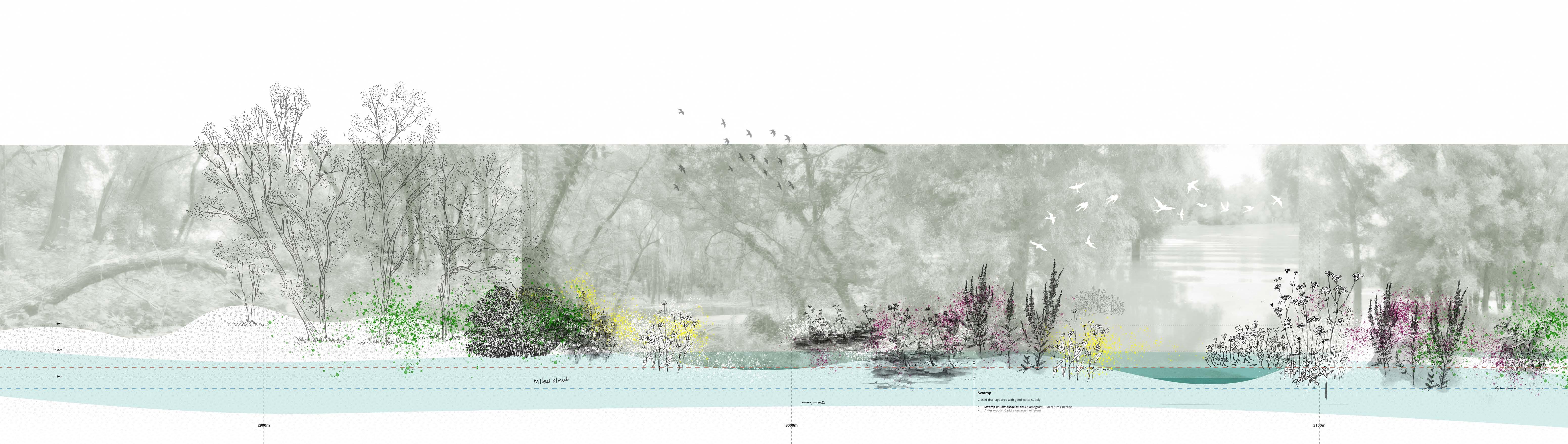

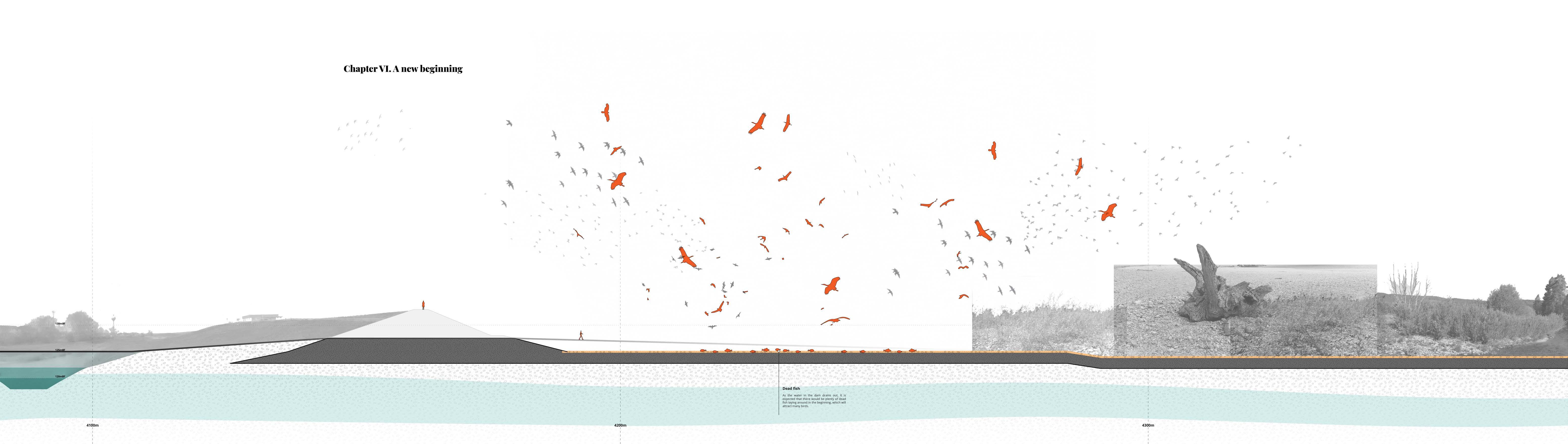

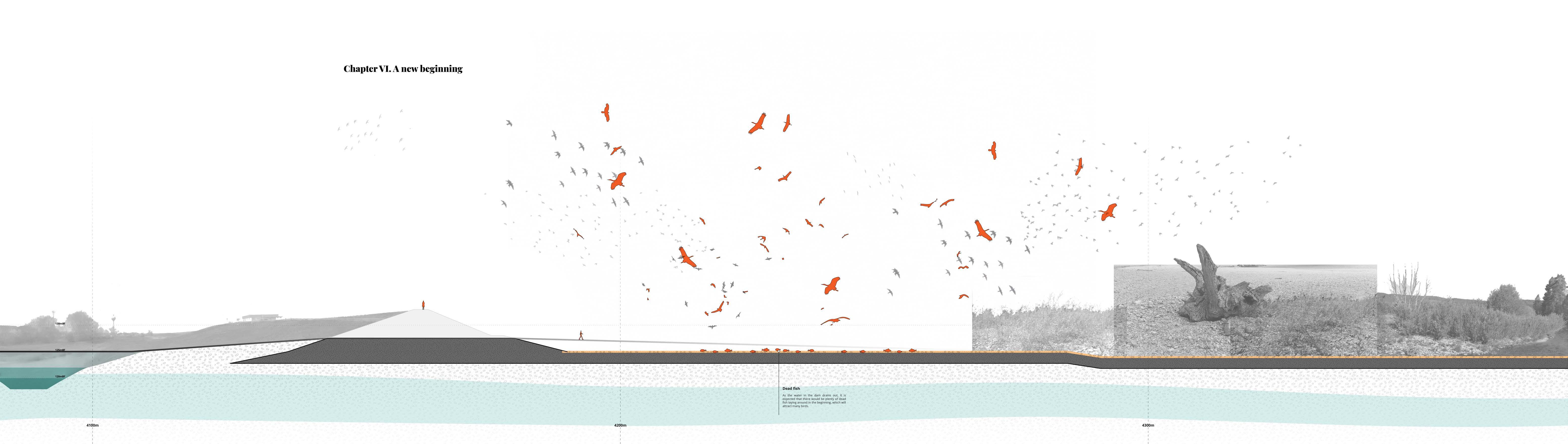

The primary residents of the River Republic—the Danube’s surface and groundwater, seasonal floods, fauna, and flora—possess an extraordinary capacity to flourish when given sufficient time and space. This space is created through subtraction: removing the Dam’s function, clearing poplar production forests, and scaling back man-made objects maintenance.

Some of the old connections are dissolved, while new ones are shaped.

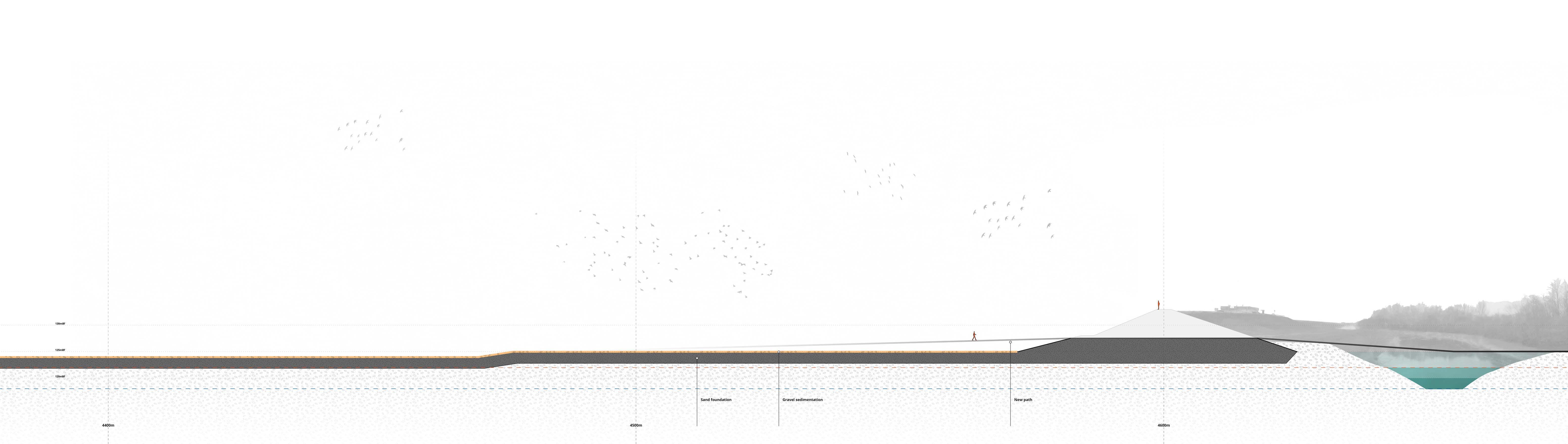

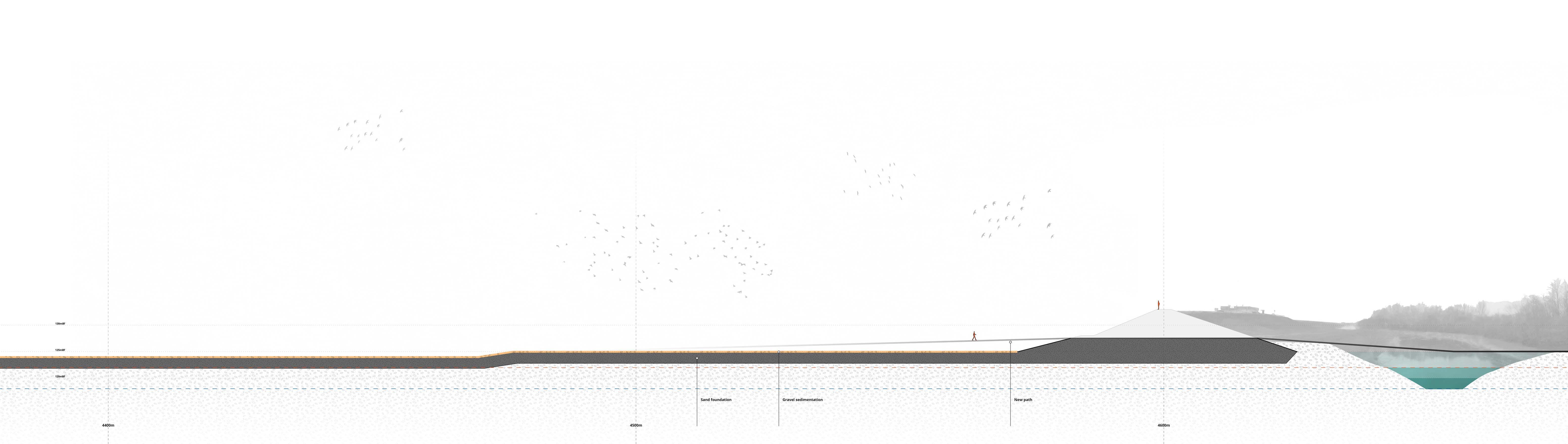

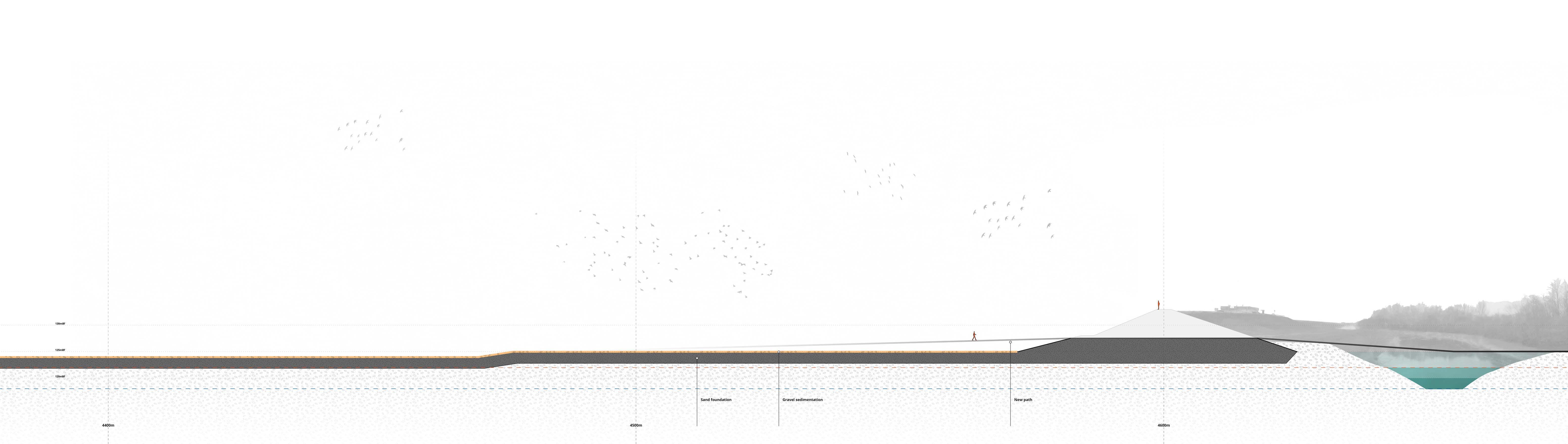

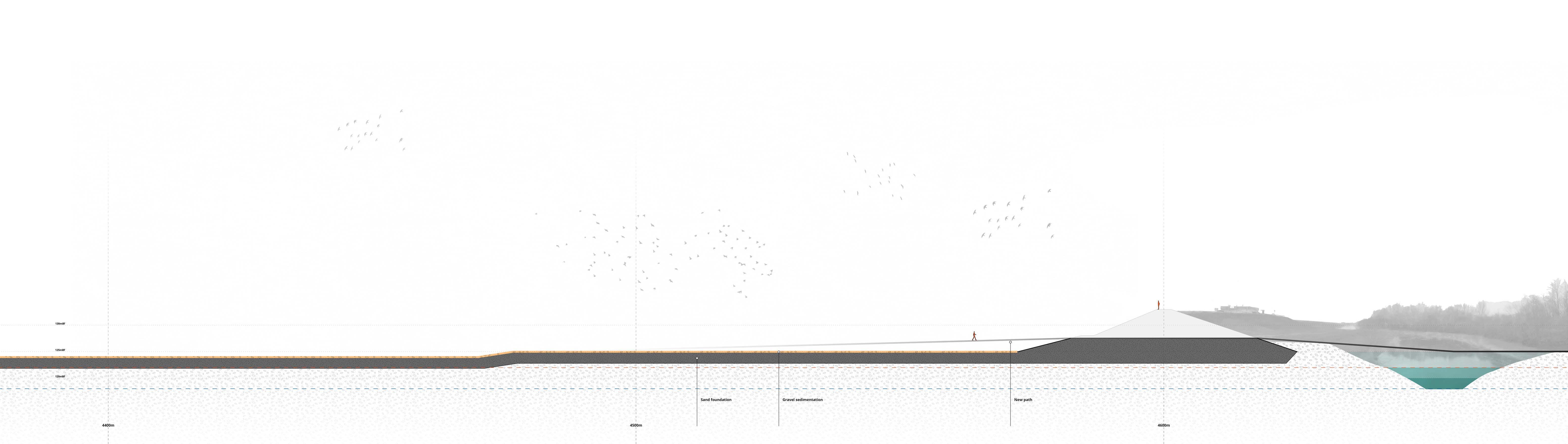

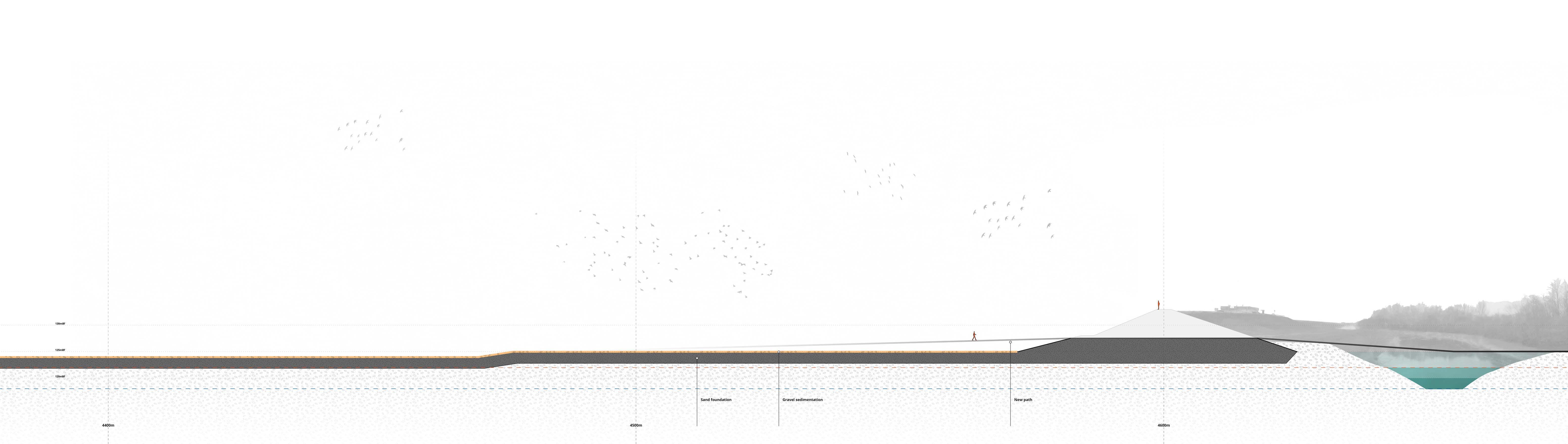

To ensure the safety of the nearby villages while realizing the River Republic, several steps must be taken. First, the landscape needs to be prepared. By digging and connecting side arms, and creating new branches, the water is provided with sufficient channels to flow and reach the inner land. The material excavated can then be used to reinforce the existing flood protection dike.

Step two is to open the Čunovo Dam and return 90% of the water to the Danube.

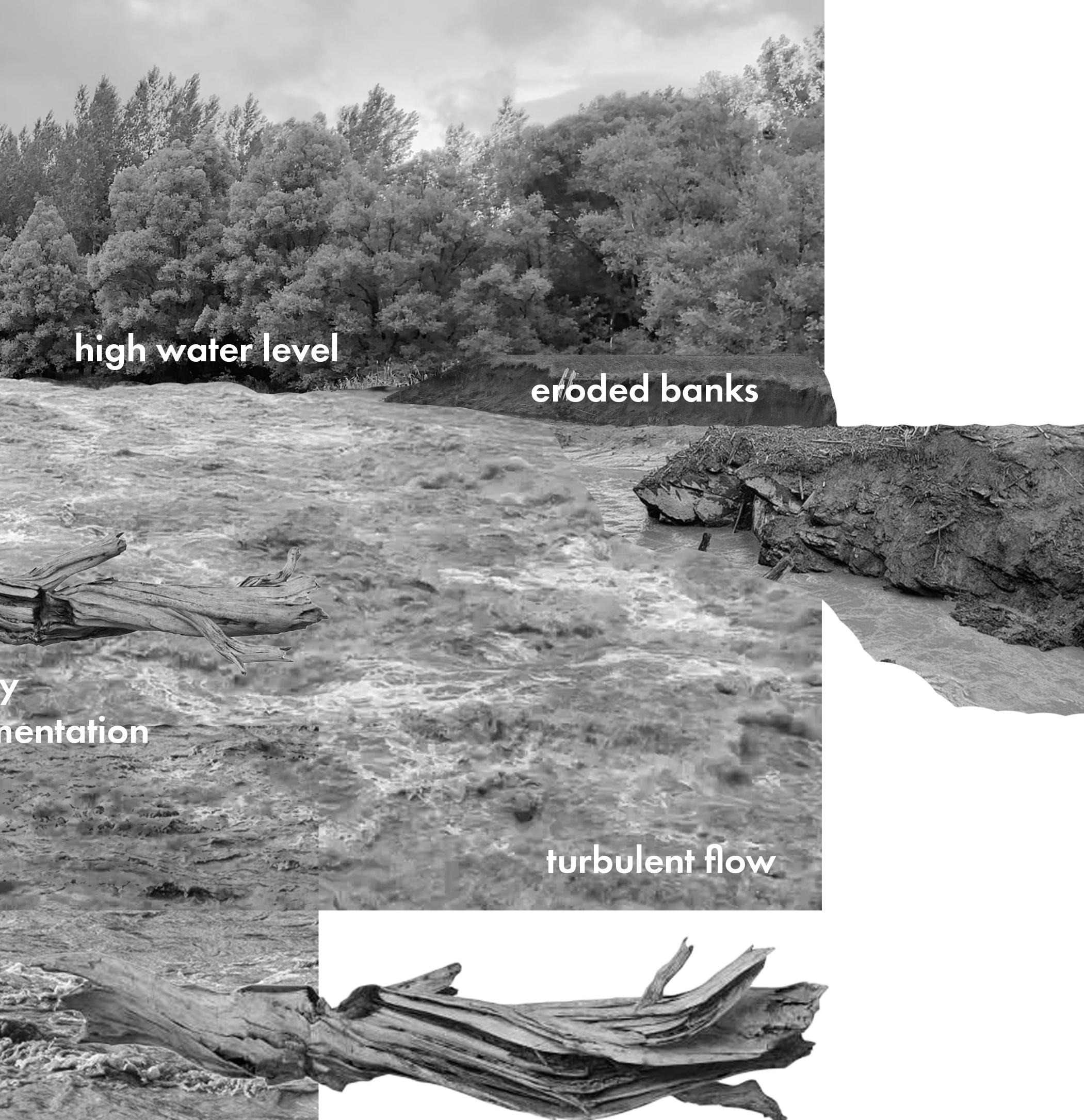

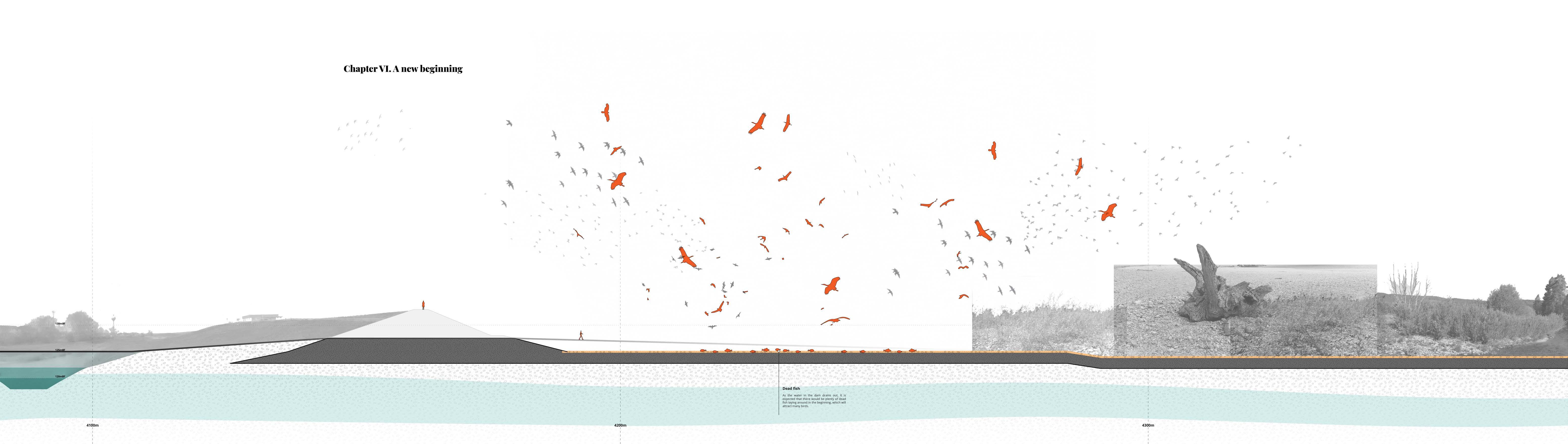

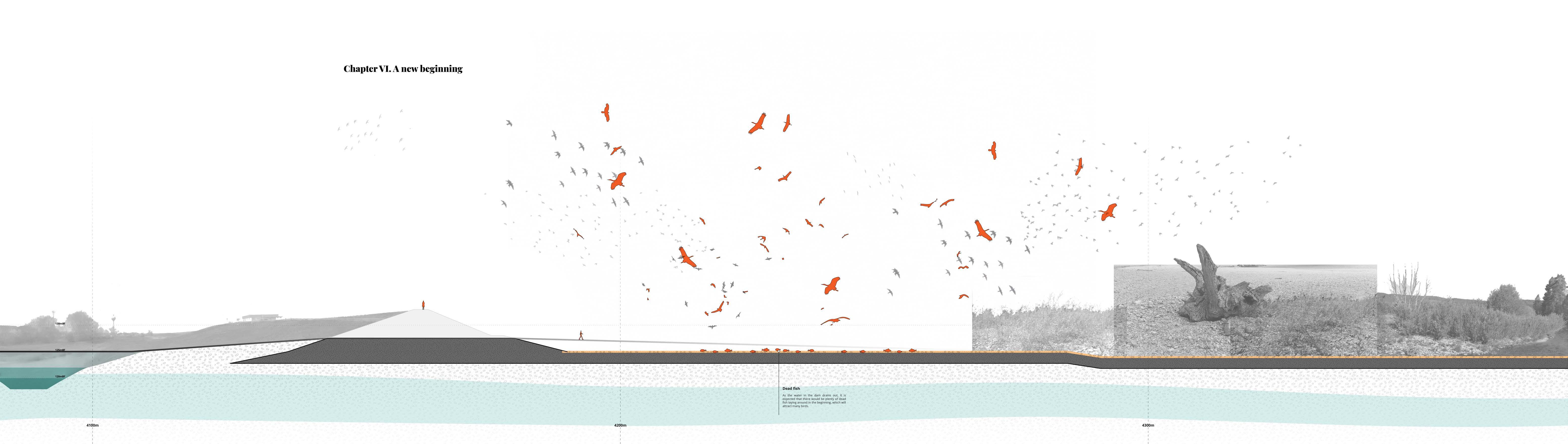

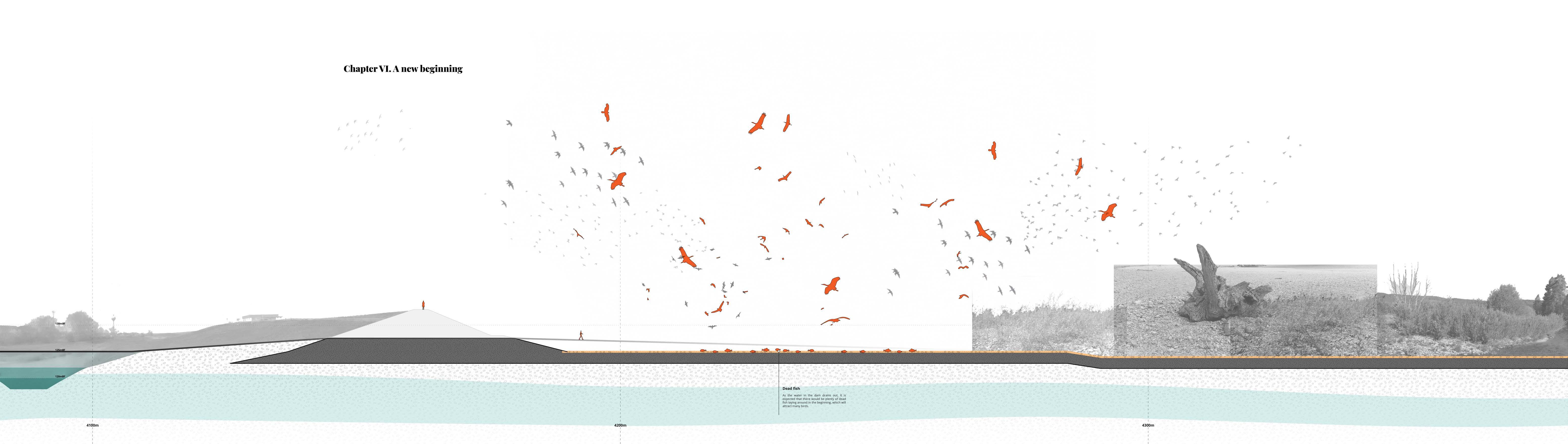

At first, the force of the water will be strong. The landscape will undergo dramatic changes under the renewed currents. Water levels and flow speed will rise, carving out much of the riverbanks. The water will turn muddy and turbulent, washing away much of the vegetation along the shore.

Finally, once the water has receded between the levees, openings can be created to allow new connections to form—providing even more space for movement and interaction for both the ecosystems and the villagers.

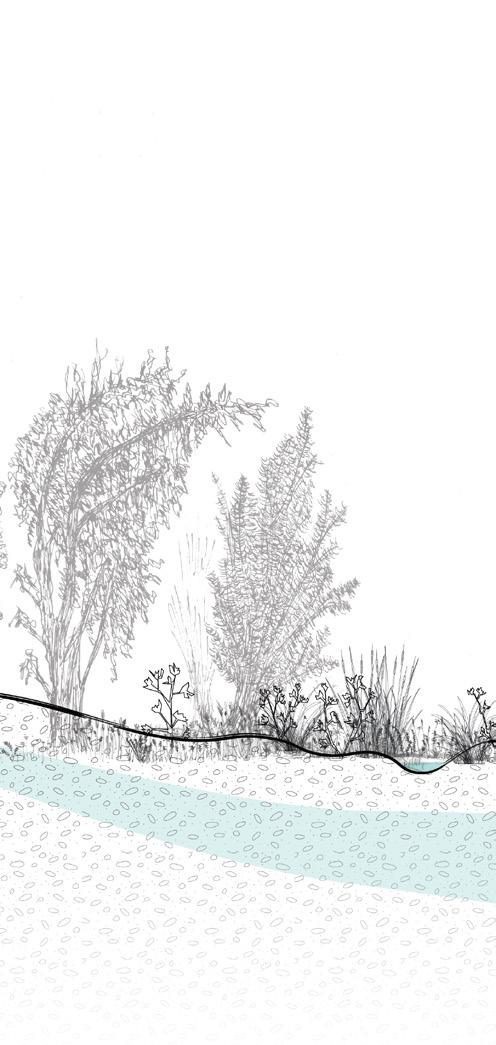

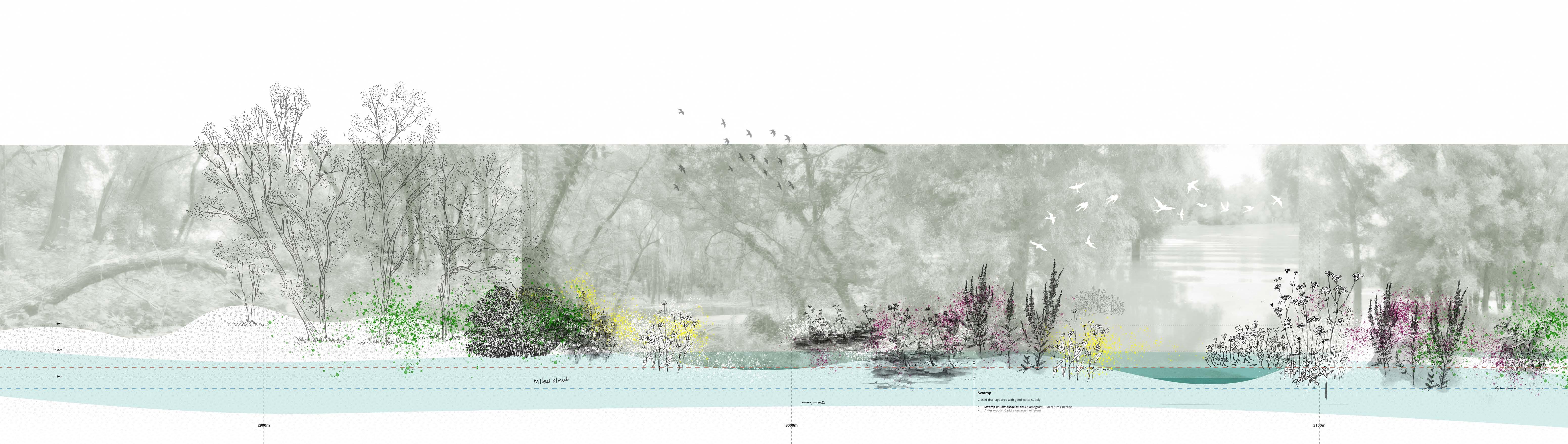

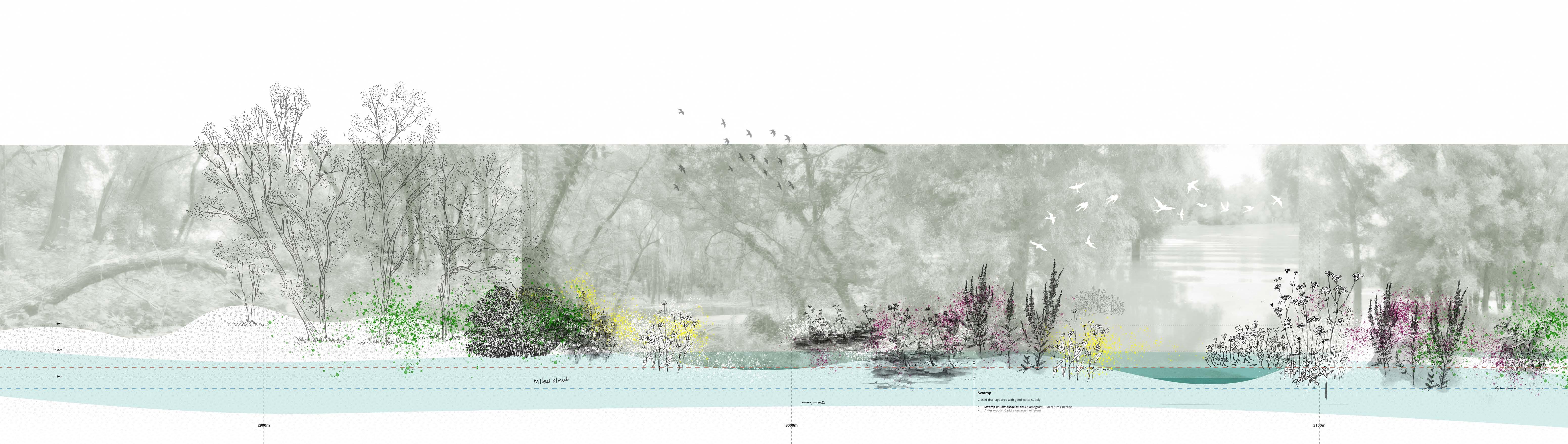

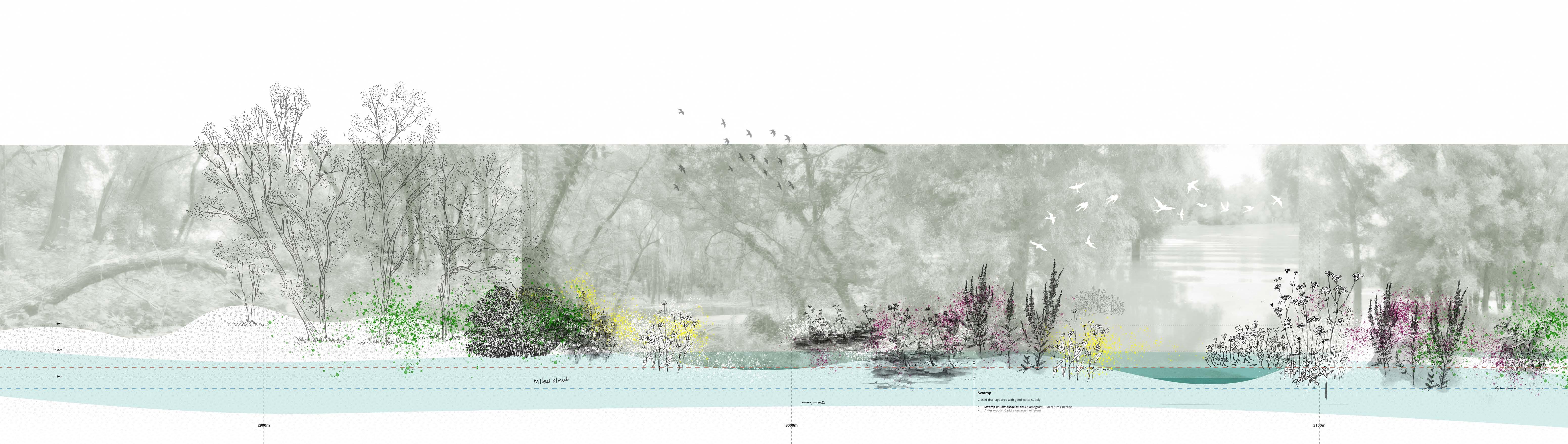

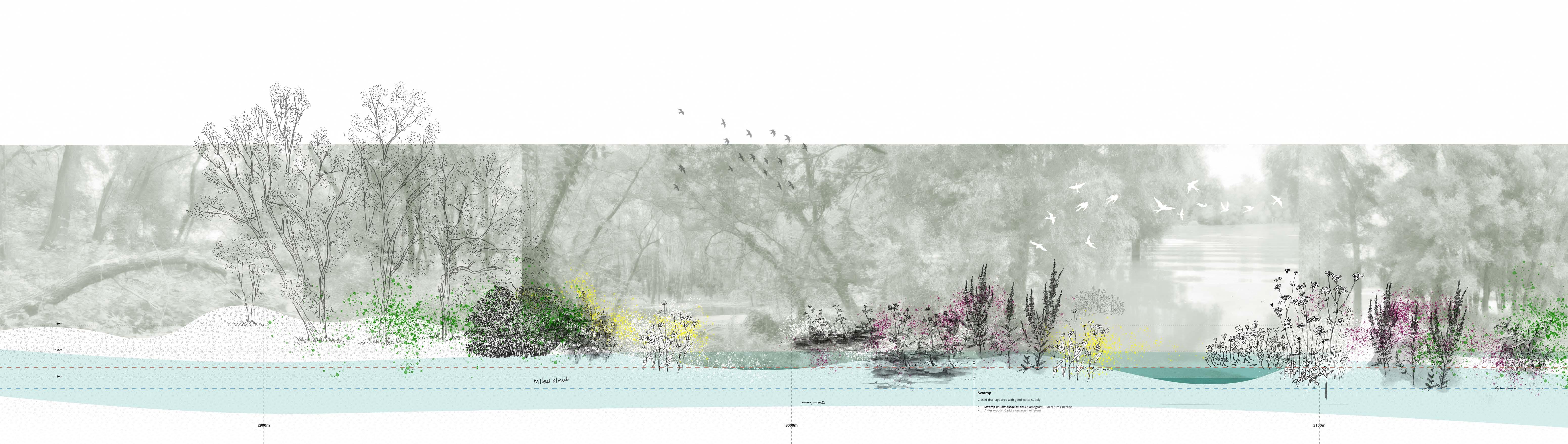

Sand/silt land with dense shrub layer

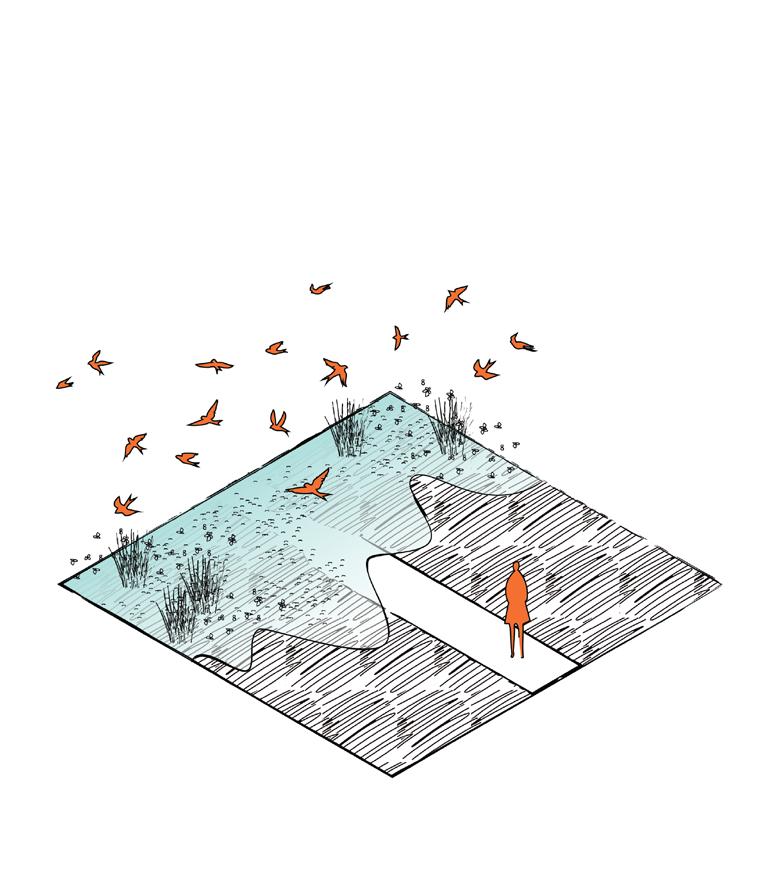

Within the River Republic, a rich variety of habitats emerges, shaped by the frequency of flooding. Roughly six distinct groups can be identified:

Gravel Islands/shore line with low pioneer vegetation

Using rivers as national borders was nothing new. As our obsession with dividing land grew, and our capacity to reshape the landscape became stronger, there came a point in history when borders stopped being shaped by nature. Instead, this “imagined reality” became ever more powerful—so much so that today the very survival of rivers is often suppressed, neglected, and denied.

In this project, by acknowledging the Danube as a third party and transforming the border between two nations into a healthy river landscape, the new borderland emphasizes what Slovakia and Hungary share, rather than what sets them apart.

“Have you ever learned the secret of a river—that there is no such thing as time?”

The Danube seeps out of the Black Forest at the same moment it pours into the Black Sea. It feeds the willow leaves while bathing a kingfisher. It is the rapid current that swallows everything in sight, and at the same time, it is the white gravel drying in the blazing sun.

The river is not merely a volume of water capable of generating power, but an entity of ebb and flow, wet and dry, on which a rich variety of lives depends.

The sound of the Danube was likely never the famous waltz, but the voices of all of those who live nearby.