Greetings, botanists!

Summer is fast underway, and we are gearing up for Botany 2025. In this issue, we include information about the conference, as well as a list of this year’s award winners and our newly elected leaders. I want to highlight the article prepared by BSA’s International Affairs Committee about the experiences of the participants of the International Botanical Congress that took place last year in Spain.

I want to acknowledge that it has not been an easy time for scientists, researchers, and students overall. The past six months have brought a wave of uncertainty, with many notices of grant cancellations and terminations leaving many unsure about the future of the scientific enterprise in the US. BSA has lost the funding for the long-standing PLANTS program, which has provided mentorship and training opportunities to more than 150 undergraduate students. According to the New York Times, there has been an overall reduction of 51% in grants awarded by NSF in 2025, with the BIO directorate having a 52% reduction. Additionally, NSF is likely going through a restructuring that would change how funding is disbursed throughout. Harsh immigration policies and political retribution are impacting the country’s ability to welcome international students and scholars, with a yet-to-be-seen effect on the growth and formation of the next generation of scientists. I want to reaffirm that the PSB is a voice for our community. If you have been impacted by cuts, immigration policies or other effects of the current political situation, please write a commentary or article to us to let your voice be heard. Likewise, if you have found a seed of joy in these dark times, we would be happy to hear from you too.

To end with a positive note, we will soon meet again at Botany 2025. More than 1000 botanists from different parts of the world will come together to celebrate our shared scientific curiosity. Let’s take this opportunity to be open, learn from each other, and strengthen our ties and community.

I hope to see you soon!

Do you aspire to lead in public gardens?

Are you passionate about using your career to make a positive global impact?

The Fellows Program develops tomorrow’s leaders, preparing them to successfully navigate pressing challenges, develop thoughtful strategies, and lead organizations that are equitable and sustainable.

During the fully funded, leadership accelerator, Fellows engage in project-based learning that allows them to hone their professional skills while delving into issues relevant to the public gardens industry today.

Applications for the 2026–2027 Fellows cohort close July 31, 2025.

Apply now at longwoodgardens.org/fellows-program.

On May 9, the Botanical Society of America received notice from the National Science Foundation (NSF) that they were immediately terminating the grant funding that supports our Botany and Beyond: PLANTS III Program ( https://botany.org/home/awards/travelawards-for-students/plants-grants/plants. html). The PLANTS (Preparing Leaders and Nurturing Tomorrow’s Scientists) program supports 20 undergraduate students with a mentored conference experience each year.

For 15 years, this program has supported 195 students from across the nation with a significant percentage going on to graduate school and botanical careers in industry, agencies, nonprofits as well as teaching in community colleges and high schools. This is a very sad and unprecedented action taken by the NSF driven by the current administration’s priorities. Thousands of scientific grants have been canceled in the last few months and the BSA Board was aware and discussed that these terminations could potentially affect us.

The good news is that BSA leadership greatly values the PLANTS program, which has a strong legacy of success after 15 years of implementation. Despite the lack of outside funding, the BSA will use some of its financial reserves to ensure the 2025 cohort of scholars and mentors can continue with plans for a mentored Botany conference experience in Palm Springs this year. We made a commitment to this cohort and we intend to honor it.

The program remains intact for Botany 2025, and we are communicating this news with our undergraduate scholar cohort, the mentors for the program and our partners at American Society of Plant Taxonomists (ASPT) and Society of Herbarium Curators (SHC). We know what a meaningful experience the PLANTS program brings to our community, and we thank all who have served as mentors, principal investigators, and supporters over the years.

We originally shared this unprecedented change in funding to you in mid-May and have already received over $17,300 in donations from our community, as well as several pledges for more. Thank you if you have already given to this program! Annually the program will cost over $75,000 to run in the same capacity as it has been done before, where scholars are fully funded to attend the conference and peer mentors receive partial scholarships for their time and dedication. If you would like to help support the PLANTS program for 2025 and help us plan for its continued success for next year and beyond, we encourage you to make a donation to the BSA PLANTS Grant Fund (https://crm.botany. org/makeadonation). While we are seeking

private foundation grants, we are turning to our community to fill the gap. Donations of any size will be greatly appreciated! A handful of BSA members make annual gifts to BSA from their qualified retirement accounts to help defer their tax liability. Those annual gifts are much appreciated and have mutual benefits. If you are interested in making a planned gift, endowment, or donation of stock, please contact Heather Cacanindin directly at hcacanindin@botany.org. If you know of a company or organization that might be interested in discussing sponsorship of the PLANTS program, we would also love to hear from you about those ideas. Thanks to our community for all the wonderful support over the years!

Dr. Sean Graham began serving as the new editor-in-chief of the AJB in January 2025. He is a Professor in the Department of Botany at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, who has wide-ranging research interests in plant systematics and evolution, and in particular characterizing plant biodiversity from phylogenetic and phylogenomic perspectives. His interests have ranged from addressing challenging higherorder relationships—both across and within the major lineages of land plants—to more focused systematic studies of closely related taxa. Sean has studied the molecular evolution of plant genes and genomes, and the evolution of plant sexual systems. He has strong ongoing research interests in monocots and mycoheterotrophic plants. We wanted to give Sean a chance to describe his thoughts on his new role!

What inspired you to pursue the Editor-inChief position for AJB?

I’ve been a fan of the journal since I was a postdoc in Dick Olmstead’s lab at the University of Washington. (He was the one who really introduced me to the journal.) AJB is highly respected by the botanical community worldwide. It is also a Society-run journal, a huge plus for me. In addition, I am quite nosy and like to see what goes on behind the scenes to better understand how things work. I am generally interested in the processes of writing and editing, from small to large scales. So, chalk some of this up to curiosity and an opportunity for personal growth!

I have deep respect for what previous Editorsin-Chief did for the journal—Pam Diggle being the most recent example—and I aspire to help continue this long tradition. I’ve been an associate editor (AE) at the journal for years, and so I know well that the journal has a lovely and incredibly hard-working staff. It has been such a delight to work with them, which made it so much easier to think about taking on the role as an Editor-in-Chief!

Finally, we live in interesting times: The field of scholarly publishing is changing very rapidly. I want to help the journal and the Society navigate potentially choppy waters, and to contribute to the continuing success of the journal.

What excites you at the moment about working on AJB?

Learning a complex and sometimes difficult new role, and helping the journal to prosper!

What do you see as the main strengths of AJB, and where are areas that could be strengthened?

A major strength is that, as a Society-run journal, our main focus (along with our sister BSA journal, Applications in Plant Sciences [APPS]) is simply on publishing good work. Profit is not the primary motivation, although of course we need to be fiscally responsible.

Funds generated from the journal are returned to the Society to support our community. Thus, a strength is that the journal serves the Society’s members, our authors, and our readers—and not primarily the publisher shareholders.

And although Impact Factor is a serious consideration for all journals, our overarching goal is to be a broadly focused and welcoming journal, for diverse kinds of excellent botanical science from around the world.

We also continue to explore ways to work with our sister journals: APPS and the Plant Science Bulletin (PSB). We’ve been grappling with increasing the number of review articles at AJB, and how best to do that, because these are an impactful form of scientific communication. Along the same lines, the “On the Nature of Things” (OTNOT) articles introduced by my predecessor, Pam Diggle, have been a great addition. I think we should experiment more with new types of articles, and I have some ideas I’d like to explore!

Funds generated from the journal are returned to the Society to support our community. Thus, a strength is that the journal serves the Society’s members, our authors, and our readers—and not primarily the publisher shareholders.

As far as scholarly publishing overall: What do you see as the current challenges and advantages for Society publishers that our community should be aware of?

There are many big challenges. A major one is the rapidly dwindling money we get from library subscriptions and licenses. We are still figuring out how to prosper financially as a Society-run journal in partnership with a major publishing company. So, we are navigating an increasingly Open Access environment that is upending the traditional scholarly publishing model (which may not all be negative!).

For many years, there has been a worldwide push for Open Access, which allows anyone to have access to content—which is good, of course. However, publishing is not inexpensive and this poses exceptional challenges for Society-run journals, especially in fields like ours that often have relatively little money to do research, much less funds to support article publication charges (APCs). Publishers negotiate publishing deals with consortia and institutions (see https://authorservices.wiley. com/author-resources/Journal-Authors/ open-access/affiliation-policies-payments/ institutional-funder-payments.html), but

even these are not available to all of our authors.

However, my biggest concern is a societal one—the effect of generative AI on writing, reading, teaching, learning, and thinking. I am deeply concerned that genAI will have a net negative effect on all of these, and ultimately on scientific discovery. Of course, machine learning and similar approaches have enormous potential for speeding up and expanding botanical research and data exploration. But humans should be at the “centre” [sic; I am Canadian] of how journals work, and who they are ultimately for!

What suggestions do you have for people who might be thinking about submitting an article to AJB?

Please consider submitting your best work to AJB! We have a fantastic team of staff, associate editors. and reviewers who will help you to produce the best paper possible. Your work will get noticed.

How can BSA members support AJB as a strong and influential journal in our field?

See my previous responses! Also: I would ask that the BSA membership please avoid the alarming subset of for-profit journals out there that have predatory practices, leading to significant shortcuts with reviewing and editing. We need to maintain integrity of the publishing process, and keep it fair and equitable for all.

Keep on doing what AJB does well, while experimenting and innovating with new approaches and content to ensure its longterm success. I also want to encourage earlycareer researchers to serve as reviewers and associate editors, and to keep sending your articles to AJB. You, too, could be the AJB Editor-in-Chief in the future!

The “Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society of America” is the highest honor our Society bestows. Each year, the award committee solicits nominations, evaluates candidates, and selects those to receive an award. Awardees are chosen based on their outstanding contributions to the mission of our scientific Society. The committee identifies recipients who have demonstrated excellence in basic research, education, public policy, or who have provided exceptional service to the professional botanical community, or who may have made contributions to a combination of these categories.

Dr. Tia-Lynn Ashman, University of Pittsburgh

Dr. Mudassir Asrar, University of Balochistan

Dr. Suzanne Koptur, Florida International University

Dr. Tia-Lynn Ashman, Professor at the University of Pittsburgh, has been named a 2025 Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society of America in recognition of her transformative contributions to plant science, mentoring, and global scientific collaboration. With over 220 publications and more than 21,000 citations, Dr. Ashman has advanced our understanding of the evolutionary ecology of plant reproduction—particularly through her work on sex chromosome evolution in strawberries, pollen limitation, and polyploidy. Her colleagues describe her as “a visionary, pushing the boundaries of scientific inquiry while maintaining exceptional rigor,” and praise her as “a leader in the field of plant evolutionary ecology.” Her work has not only opened new avenues in botanical research but also reinvigorated interest in long-standing ecological and genetic questions.

Equally impactful is Dr. Ashman’s dedication to mentoring and community-building. Her former students and postdoctoral researchers now thrive in academia, government, and science communication roles, often citing her high standards and unwavering support as pivotal to their success. “She’s tough, she’ll push you, but you’ll accomplish so much. You will become a great scientist,” one mentee recalled. Dr. Ashman has also led major international collaborations and working groups on pollen limitation, emergent sex chromosomes, pollination in biodiversity hotspots and many other topics that synthesize critical knowledge across diverse disciplines, creating tools and frameworks that will guide plant biologists for decades. In the words of another nominator, “She not only advances our field but also cultivates the next generation of scientists, ensuring that her impact extends far beyond her own work.”

As a Meritorious Professor at the University of Balochistan and a global representative of Pakistan in the botanical sciences, Dr. Mudasir Asrar has made lasting contributions in plant biotechnology, medicinal plant research, and science policy. A widely respected scholar and mentor, she has published over 160 research papers, authored 15 books, and presented work in more than 200 national and international conferences. Her impactful leadership includes chairing the Pakistan Council for Science and Technology and contributing to national STI policy development. One nominator praised her “unparalleled commitment to advancing plant sciences in Pakistan and globally,” citing her as a “trailblazer for women in science.”

Dr. Asrar’s influence extends well beyond academia. She has led the establishment of pioneering scientific infrastructure in Pakistan, including botanical gardens and tissue culture laboratories. As a dedicated mentor, she has supervised hundreds of students across all levels of higher education. Her work in digitizing the flora of Balochistan in collaboration with international partners has opened new frontiers for biodiversity research. As another nominator reflected, “Dr. Asrar’s legacy is defined not only by scientific achievement but also by her unyielding efforts to uplift communities through education and innovation.”

Dr. Suzanne Koptur has been named a 2025 Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society of America in recognition of her four-decade-long career marked by excellence in botanical research, education, and conservation. A Professor Emerita at Florida International University, Dr. Koptur is internationally recognized for her pioneering work on plant-insect interactions, particularly the role of extrafloral nectaries in ant-plant mutualisms. Her influential publication on these interactions has become a foundational resource in the field, with over 500 citations.

Beyond academia, Suzanne’s leadership in conservation initiatives, such as co-founding the Native Plant Network has had lasting impact on the preservation of Florida’s endangered Pine Rockland ecosystem. “Her love for

plants and for their protection has been a gift to the public and scientific community alike,” wrote one nominator. Known for her inspiring mentorship—particularly of women and those underrepresented in science—Dr. Koptur has guided over 30 graduate students, cultivated public engagement through education and outreach, and remains a great favorite among students, staff, and faculty. One nominator stated, “Suzanne has excelled at everything she does, be it academics, research in lab or field, presentation, teaching, professional or public service. Her background is diverse and impressive. Be we student or colleague, Suzanne knows how to cultivate the best in us. She is an engaging persona, upbeat, with exacting standards for herself and others, yet she is compassionate, patient, genuinely kind, and fun. She has trained hundreds of students during her tenure at FIU and elsewhere.” In addition, Dr. Koptur has contributed active leadership to the Florida Native Plant Society, Native Plant Day, the Endangered Plant Advisory Committee of the State of Florida, the Rare Plant Task Force, and through her membership in many other local conservation organizations. We cannot imagine a more deserving awardee than Suzanne.

The Botanical Society of America Impact Award recognizes a BSA member or group of members who have significantly contributed to advancing diversity, accessibility, equity, and/or inclusion in botanical scholarship, research and education.

University of Georgia

(BSA in association with the Teaching Section and Education Committee)

Cartoonist – PlantsGoGlobal.com

Naomi Volain is an innovative nationally recognized high-school science teacher and science communicator. Since 2008, she has engaged her students in PlantingScience activities, earning multiple Star Project Awards. She also advised revisions of the program, impacting hundreds of teachers and thousands of students nationwide. Ms. Volain served on the advisory board for the NSF-funded grant “Digging Deeper Together,” focused on teacher–scientist professional development. She created and taught the first Botany course at her school, revitalizing the greenhouse (still named in her honor). She is a valued mentor to new teachers, and one nominator described her as “the most dedicated teacher, especially in botany.” Ms. Volain has also developed online botanical resources, including the “Plants Go Global” website. As one nominator stated, “She truly is a rockstar educator and science communicator.”

Cal Poly State University, San Luis Obispo

Dr. Jenn Yost, Associate Professor and Director of the Herbarium at California Polytechnic State University, is a dedicated educator and impactful California botanist. She has expanded the herbarium by training students and community members in collection techniques, leading digitization efforts across California, and incorporating cutting-edge digital analyses. Many student research projects and classes utilize the extensive collection. Dr. Yost also engages with local communities through the Urban Forest Ecosystem Institute, gives many public lectures, and leads local tree-planting initiatives. Her well-organized field botany courses have trained hundreds of students, earning praise from nominators for her energy and ability to simplify complex concepts. As nominators note, she “saturates every sentence with enthusiasm” and “being a student with Jenn is like being a kid again—every moment is filled with discovery and delight.”

This award was created to promote research in plant comparative morphology, the Kaplan family has established an endowed fund, administered through the Botanical Society of America, to support the Ph.D. research of graduate students in this area.

Dr. Pamela Diggle University of Connecticut

This award was established in 2006 by Dr. Barbara D. Webster, Grady’s wife, and Dr. Susan V. Webster, his daughter, to honor the life and work of Dr. Grady L. Webster. After Barbara’s passing in 2018, the award was renamed to recognize her contributions to this field of study. The American Society of Plant Taxonomists and the Botanical Society of America are pleased to join together in honoring both Grady and Barbara Webster. In odd years, the BSA gives out this award and in even years, the award is provided by the ASPT.

Jacob S. Suissa, Andrews A. Agbleke, William E. Friedman

A bump in the node: The hydraulic implications of rhizomatous growth

American Journal of Botany, January 2023 110(1): e16105

(These include the BSA Professional Members Travel Awards, the Developing Nations Travel Awards, and the Hardship Travel Awards)

Ellie Becklund, University of Connecticut and Ohio University

Timothy James Biewer-Heisler, Indiana University

Betsy Justus Briju, G.S.Gawande College

Marco Chiminazzo, São Paulo State University (UNESP)

Israel L. Cunha-Neto, New York University

Hilary Rose Dawson, Australian National University

Jenna Ekwealor, San Francisco State University

Jessamine Finch, Atlanta Botanical Garden

Vikas Garhwal, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata

Ash Hamilton, University of Chicago / The Morton Arboretum

Wen-Hsi Kuo, Missouri Botanical Garden

Isabela Lima Borges, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

Oranys Marin, University of Utah

Mason McNair, Michigan State University

Damilola Odumade, University of Kansas

Rebecca H. Penny, Aquinas College

Diana Karen Pérez Lara, EAFIT University

Malka Sava, Quaid-i-Azam University

Nathália Susin Streher, University of Pittsburgh

Mariana Vazquez, Connecticut College

Yannick Woudstra, Stockholm University

Eric Yee, University of Pittsburgh

Wenbin Zhou, UNC Chapel Hill

The Samuel Noel Postlethwait Award is given for outstanding service to the BSA Teaching Section.

Kyra Krakos, Maryville University

This award organized by the Environmental and Public Policy Committees of BSA and ASPT aims to support local efforts that contribute to shaping public policy on issues relevant to plant sciences.

Kimberly Brown

For the proposal: Creating Accessible and Educational Native Plant Gardens

The Public Policy Award was established in 2012 to support the development of of tomorrow’s leaders and get a better understanding of this critical area.

Rina Talaba, Chicago Botanic Gardens and Northwestern University

Katherine Wolcott, University of Miami

This award is named in honor of the late Dr. AJ Harris whose research spanned traditional specimen-based science, paleobotany, phylogenomics, biogeography, and computational biology. This award is given in conjunction with the Graduate Student Research Awards and is given to a graduate student whose research is representative of one of the areas above.

Nora Heaphy, University of Vermont

For the Proposal: Adaptive introgression and demographic structure in a keystone northern forest tree

This award was created to promote research in plant comparative morphology, the Kaplan family has established an endowed fund, administered through the Botanical Society of America, to support the Ph.D. research of graduate students in this area.

Oluwatobi Oso, Yale University

For the Proposal: Comparative Morphology of Leaf Development: Bud Packing and Cellular Mechanisms Driving Evolution Across Latitudinal Gradients.

Honorable Mention:

Christopher Joaquín Muñoz, The University of Texas at El Paso

For the Proposal: Trait Evolution in Hebecarpa (Polygalaceae).

This award supports the Ph.D. research of graduate students in the area of comparative plant biology, broadly speaking, from genome to whole organism. To learn more about this award click here.

Sara Sofia Pedraza Narvaez, University of California–Los Angeles

For the Proposal: Comparative phylogeography and thermal performance of four clades of montane tree species: an integrative approach to study diversification of tropical plants

The BSA Graduate Student Research Awards support graduate student research and are made on the basis of research proposals and letters of recommendations. Within the award group is the Karling Graduate Student Research Award. This award was instituted by the Society in 1997 with funds derived through a generous gift from the estate of the eminent mycologist, John Sidney Karling (1897-1994), and supports and promotes graduate student research in the botanical sciences.

Anthony Garcia, University of Washington

For the Proposal: Developmental genetics of carpel innovations mediating pollination

Katherin Arango-Gómez, Louisiana State University

For the Proposal: Exploring Montane Forests to Unveil Patterns of Range Sizes in the Neotropical genus Cavendishia (Ericaceae)—A phylogenetic approach

Shawn Arreguin, University of Illinois at Chicago

For the Proposal: Urbanization and its impact on reproductive strategies: A case study of cleistogamy in Lamium amplexicaule

Louisa Bartkovich, University of Toronto

For the Proposal: Decoupling the effects of warming and canopy cover on reproductive phenology in the spring ephemeral Erythronium americanum

Rachel L. Benway, Syracuse University

For the Proposal: Fungal Community Shifts Across the Temperate-Boreal Ecotone

Lena Berry, University of Wisconsin-Madison

For the Proposal: Physiological Function of Transfusion Tracheids in the Cupressaceae

Charles Boissavy, Claremont Graduate University (California Botanic Garden)

For the Proposal: Phylogenetics, Taxonomy, Trait Evolution, and Biogeography of the Latifolia Clade in Eriogonum

Rachel O. Cohen, Columbia University

For the Proposal: An investigation of haustoria-associated genes in the facultative hemi-parasite Pedicularis groenlandica

María Cuervo-Gómez, University of Florida

For the Proposal: Influence of autopolyploidization on the phenotype and vulnerability to drought and heat in Arabidopsis thaliana

Cael Dant, Northwestern University

For the Proposal: Understanding the impact of prey type and the pitcher microbiome on physiological success of the carnivorous plant Sarracenia purpurea

Mahima Dixit, Claremont Graduate University

For the Proposal: Phylogeny, Phytochemistry, and Taxonomy of Eriogonum subg. Ganysma with a Focus on the E. deflexum Complex (Polygonaceae)

Sanika Goray, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) Bhopal

For the Proposal: A multifaceted approach to explore the taxonomic identity of an endemic, polymorphic Balsam from the Western Ghats, India

Anupreksha Jain, University of Wisconsin – Madison

For the Proposal: Plant-pollinator interactions after drought: integrating plant physiology, floral rewards, and pollinator behavior

Jeffrey Keeling, University of Texas at El Paso

For the Proposal: Eriophorum vaginatum phytobiome in central, northern Alaska

Kyla Knauf, Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden

For the Proposal: From Flowers to Seeds: Understanding the Effects of Climate Change on Rocky Mountain Wildflower Phenology and Reproduction

Kiona A. Leeman, University of Wisconsin - La Crosse

For the Proposal: Aphyllon assembly: elucidating the phylogenetics of a genus of non-photosynthetic angiosperms using the Angiosperms353 probe kit

Benjamin Lloyd, University of Washington

For the Proposal: A Deep Learning Approach to the Phylogenetic Placement of Fossil Grass Silica Short Cell Phytoliths

Victoria Martinez Mercado, Northwestern University

For the Proposal: Multi-omic Approach for Pollen Banking in Asimina triloba: A Model for Conservation

Charli Minsavage-Davis, Georgetown University

For the Proposal: Testing for adaptation in the clonal salt marsh grass Spartina patens with a novel coalescent model and DNA-sequence polymorphisms

Whitney A. Murchison-Kastner, Tulane University

For the Proposal: Investigating parallel evolution in two Mimulus species using comparative quantitative trait loci mapping

Nicole Phelan, University of Vermont

For the Proposal: Resolving Hybrid Origins in a Wild Sunflower (Helianthus) Species Complex

Riya Rampalli, Columbia University

For the Proposal: Consequences of sexual dimorphism on the evolution of amaranths: insights from hybrid recombination maps and genetic incompatibilities

Yanã Rizzieri, Cornell University

For the Proposal: Investigating genome evolution in the water ferns (Salviniales) and its relationship to heterospory

Rhuthuparna S B., Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Bhopal, India

For the Proposal: Outcrossing to selfing: Understanding the functional and evolutionary implications of herkogamy in an enantiostylous genus

Yogesh Sharma, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra, Haryana, India

For the Proposal: Floristic Studies of The Diversity of Grasses (Agrostology) in Haryana, India: A Comprehensive Survey and Digital Documentation

Sarah Ellen Strickland, University of Florida

For the Proposal: How do they handle the heat? A Comparison of allopolyploid Tragopogon miscellus and its diploid parents under heat and drought stress

Daniel Wehner, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry

For the Proposal: An Uphill Battle: Seed dispersal and mycorrhizal constraints on the climate-driven upslope migration of trees species in the northeastern U.S.

The BSA Undergraduate Student Research Awards support undergraduate student research and are made on the basis of research proposals and letters of recommendation.

Andrew Conlon, Emory University

For the Proposal: Determining Selective Cytotoxic and Antibiotic Properties of Teucrium flavum L. for Public Safety and Medical Advancement. Co-authors: Dr. Cassandra Quave, Dr. Tharanga Samarakoon, Nadia Aziz, Marco Caputo

Lena Kadau, University of South Carolina

For the Proposal: Seed Mucilage Trait Evolution Across Populations and Species of Linum.

Will Pearce, University of Utah

For the Proposal: Intraspecific Variation and Species Boundaries of the Desert Gooseberries (Ribes series Microphylla). Co-author: Dr. Rodolfo Probst

Alex Risdal, Loyola University Chicago

For the Proposal: Habitat Evaluation and Species Distribution Modeling for Michigan’s Bladderworts (Utricularia spp.). Co-authors: Dr. Brian Ohsowski, Dr. Mike Grillo, Shane Lishawa

Nicole Stark, The University of Alabama in Huntsville

For the Proposal: Uncovering the Origin and Genomic Mechanism of Dioecy in the Family Fabaceae.

Brooke C. Tillotson, SUNY Cortland

For the Proposal: Investigating the correlation between homeolog bias and differences in phenotype and pigment composition in Nicotiana quadrivalvis and N. clevelandii allopolyploids.

The PLANTS (Preparing Leaders and Nurturing Tomorrow’s Scientists: Increasing the diversity of plant scientists) program recognizes outstanding undergraduates from diverse backgrounds and provides travel grant.

Ormary Alvarez, Lehman College, Advisor: Cecilia Zumajo

Mickie Barraza, New Mexico State University, Advisor: Sara Fuentes -Soriano

Abbigale Baum, Utah Valley University, Advisor: Michael C. Rotter

Kathryn Bourlier, Old Dominion University, Advisor: Erik Yando

Leo Case, Oregon State University, Advisor: Gail Langellotto

Gianna Claude, Old Dominion University, Advisor: Nicholas Flanders

James Davis, Oklahoma State University, Advisor: Cody Howard

Muriel Draper, Old Dominion University, Advisor: Erik Yando

Marissa Falla, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, Advisor: Mare Nazaire

Nova Hodgson, Oregon State University, Advisor: Gar Rothwell

Abigail Kohn, University of Michigan, Advisor: Selena Smith

Jada Martinez, University of North Texas, Advisor: Elinor Lichtenberg

Marissa Mc Lean, SUNY Cortland, Advisor: Elizabeth McCarthy

Victor Melendez Maldonado, Christopher Newport University, Advisor: Janet Steven

Maylin On, Cal Poly Humboldt, Advisor: Alana Chin

Tyler Radtke, University of Florida, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Advisor: Pam Soltis, Doug Soltis

Andrew Ruegsegger, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Advisor: Maribeth Latvis

Charlotte Saltsman, Murray State University, Advisor: Ingrid Jordon-Thaden

Icyss Sargeant, Louisiana State University, Advisor: Laura Lagomarsino

Alysha Schjelderup, University of California Santa Cruz, Advisor: Jarmilla Pitterman

Dailyn Wold, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire, Advisor: Nora Mitchell

The purpose of these awards is to offer individual recognition to outstanding graduating seniors in the plant sciences and to encourage their participation in the Botanical Society of America.

Sabilah Alibhai, Connecticut College, Advisor: Rachel Spicer

Sofía Elizabeth Báez, Old Dominion University, Advisor: Lisa Wallace

Edie L. Banovic, Connecticut College, Advisor: Rachel Spicer

Tori Barrow, Colorado College, Advisor: Rachel Jabaily

Rebecca Beneroff, Bucknell University, Advisor: Chris Martine

Ana Bermudez, Connecticut College, Advisor: Rachel Spicer

Kendall Cross, St. Cloud State University, Advisor: Angela McDonnell

Olivia Demetrakopoulos, University of Guelph, Advisor: Edeline Gagnon

Madison N. Dimarco, University of South Carolina, Advisor: Eric LoPresti

Andy Dorsel, Bucknell University, Advisor: Chris Martine

Sebastian Fernandez, University of Florida, Advisor: Makenzie Mabry

Addison Gensch, University of Minnesota - Twin Cities, Advisor: Alexandra Crum

Alise Catherine Griffiths, University of Guelph, Advisor: Christina Caruso

Kaitlin Henry, Bucknell University, Advisor: Chris Martine

Lena P. Kadau, University of South Carolina, Advisor: Eric LoPresti

Aspen Mazzatta, University of Tennessee, Advisor: Jessica Budke

Caelen McCabe, University of Guelph, Advisor: Christina Caruso

Anna Mele, Portland State University, Advisor: Mitch Cruzan

Elisabeth Moore, Barnard College, Advisor: Hilary Callahan

Abigail Motter, Bucknell University, Advisor: Chris Martine

PJ Newhart, Bucknell University, Advisor: Chris Martine

Diandra Polt, Brown University, Advisor: Rebecca Kartzinel

Tyler Radtke, University of Florida, Advisor: Makenzie Mabry

Charlotte Saltsman, Murray State University, Advisor: Ingrid Jordon-Thaden

Yash Kumar Singhal, University of Toronto, Advisor: John Stinchcombe

Isabel Smalley, University of Minnesota Duluth, Advisor: Amanda Grusz

Torrance Wagner, Connecticut College, Advisor: Rachel Spicer

Winners were selected by lottery

Dan J. Coles

Amadeu dos Santos-Neto

Vandana Gurung

Kiona A. Leeman

Whitney Murchison-Kastner

Kasey K. Pham

Mia Stevens

Marisa Blake Szubryt

Yannick Woudstra

Matthew Yamamoto

The following winners were selected from the Association of Southeastern Biologists meeting that took place at the end of March 2025.

Daniel Stanton, UF IFAS Citrus Research and Education Center

Southeastern Section Poster Presentation Award

Annabelle Mayes, Georgia Southern University

Jeremy W. Howland, City University of New York, Advisor: James Lendemer

For the Presentation: Karinomyces (Pilocarpaceae), a new genus for the Appalachian endemic Schadonia saulskelleyana supported by molecular and phenotypic data

Zoe Ryan, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Advisor: Ken Cameron

For the Presentation: Open-source software integration: A tutorial on species distribution mapping and ecological niche modeling

Sarita Munoz-Gomez, Auburn University; Advisor: Daniel S. Jones

For the Presentation: Dioecy and sex determination across the development of the dioecious genus Baccharis (Asteraceae)

Austin Nguyen, University of Kansas; Advisor: Kelly Matsunaga

For the Presentation: Duplication and subfunctionalization of AGAMOUS genes in the cypress family (Cupressaceae)

Arezoo Fani, University of Kansas; Advisor: John Kelly

For the Presentation: Transgenerational Plasticity Enhances Offspring Fitness in Competitive Environments Through Epigenetic Mechanisms

Jill M. Love, Tulane University; Advisor: Kathleen Ferris

For the Presentation: Investigating the adaptive significance of leaf shape plasticity in a California endemic plant, Mimulus laciniatus

Alex Risdal, Loyola University Chicago; Advisor: Brian Ohsowski

For the Presentation: Modeling a Murderer: Determining the Ecological Requirements of Michigan’s Bladderworts

Tabassum Tamima, St. Cloud State University

For the Presentation: Management of Chilli Leaf Curl Virus (ChLCV) of Chilli using selected Agrobotanicals, Raw cow milk, Bioagent and Insecticide under field condition

Seongyeon Kang, University of Arizona, Advisor: Michael S. Barker

For the Presentation: Inferring ancient tetraploidy and hexaploidy using a machine learning approach. Co-authors: Michael McKibben and Michael S. Barker

Max Botz, University of Minnesota Duluth, Advisor: Amanda Grusz

For the Presentation: Does abiotic environment shape patterns of polyploidy and reproductive mode in ferns?

Dusty Prater, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Advisor: Jacob S. Suissa

For the Presentation: Putting ferns on the map: global patterns of wide-ranging fern species

Mahima Dixit, Claremont Graduate University/California Botanic Garden

Jared B. Meek, Columbia University

(BSA in association with the Developmental and Structural Section)

This award was named in honor of the memory and work of Dr. Vernon I. Cheadle.

Andrea D. Appleton, Harvard University, Advisor: Elena Kramer

For the Presentation: Morphological and developmental novelties within the intricate androecium of Loasaceae

Jaxon Reiter, University of Lethbridge, Advisor: Dr. Elizabeth Schultz

For the Presentations: “Alles ist Blatt ” —The role of auxin in gynoecium development: insights from leaf patterning genes and ovule defects in Arabidopsis thaliana PIN localization pathway mutants lead to reduced seed set

Niall S. Whalen, Florida State University, Advisor: Gregory Erickson

For the Presentation: Phytolith morphological diversity across the gymnosperm phylogeny—implications for phytolith evolution and their paleobotanical applications

CHRISTOPHER MARTINE BUCKNELL UNIVERSITY

President Elect

ALLISON MILLER

ST. LOUIS UNIVERSITY

DANFORTH PLANT SCIENCE

CENTER

Treasurer

THERESA CULLEY UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI

Director at Large for Publications

SARA PEDRAZA NARVAEZ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES

Student Representative

The Botanical Society of America is thrilled to announce a new podcast series with interviews from a variety of botanical science researchers: “A Botanical Podcast!” The podcast will focus on research and topics found in the BSA’s publications—American Journal of Botany, Applications in Plant Sciences, and Plant Science Bulletin—along with other unique topics. BSA member Dr. Shiran Ben Zeev serves as this season's host/producer of the “A Botanical Podcast,” which will feature discussions with botanists explaining their research and their passion for plants (and allied organisms). Download episodes from the main streaming platforms (Apple, Spotify, etc.) or from our hub at https://www.buzzsprout. com/2446995 Here are the four episodes of season 1:

Dr. Shiran Ben Zeev

Dr. Andrea E. Berardi: “Paradigm Shifts in Flower Color”

Dr. Berardi from James Madison University discusses the evolution of flower color and why plants change their colors. The role of plantpollinator interactions and environmental relationships is also raised. This topic ties into the upcoming “Paradigm Shifts in Flower Color” special issue of the American Journal of Botany. Berardi is an Assistant Professor at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. She is a plant evolutionary biologist whose research focuses on evolutionary, genetic, and ecological processes underlying speciation, specifically focusing on how floral traits play a role in reproductive isolation and adaptation to the environment. Her favorite traits to study are floral color and plant secondary/specialized metabolites.

https://www.buzzsprout.com/2446995/ episodes/16526788

Jordan Dowell:

“Plants Communicating Through Chemistry”

In this episode, Shiran and Jordan Dowell nerd out on a discussion of how plants choose to defend themselves against predators and/ or manipulate other organisms to help them live their best lives, and how plants use chemistry to communicate—and what we can learn from that. They talk about the special challenges of surviving and thriving in harsh environments and touch on the evolution of chemical diversity and the effects of chemical diversity on organismal interactions across spatial and temporal scales. Dr. Dowell is an assistant professor at Louisiana State University and an Associate Editor of the BSA's Applications in Plant Sciences. He studies the evolutionary ecology of plant-plant chemical communication and the impacts of multifunctional traits on biotic interactions from single-cells to landscapes using various techniques, from metabolomic and genomic approaches to remote sensing and field-based studies.

https://www.buzzsprout.com/2446995/episodes/16564616

Erica Lawrence-Paul:

“Let's Look at Vegetative Phase Change”

Is it better/more advantageous to be a juvenile or an adult? As with humans, in plants, "it’s complicated"! In this episode, Erica Lawrence-Paul discusses vegetative phase change in plants, i.e., the transition between juvenile and adult phases of vegetative growth. This transition can be visually subtle and easy to overlook in many species; however, morphological and physiological differences between juvenile and adult phases can lead to meaningful differences in plant and tissue function. Dr. Lawrence-Paul is an NSF postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Jesse Lasky’s lab in the Department of Biology at the Pennsylvania State University. She earned her doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania, studying the ecophysiological significance of the plant developmental transition, vegetative phase change, with a particular focus on photosynthetic and leaf carbon economic traits. Her current work focuses on understanding how natural variation in the timing of vegetative phase change and phase-specific differences in stress tolerance contribute to plant abiotic stress response and local adaptation.

https://www.buzzsprout.com/2446995/episodes/16870080

In this episode, Shiran and Dr. Jessica Savage have a wide-ranging conversation about how flowering plants respond to shifting seasonal changes in temperatures, especially when those changes are unpredictable—early warming periods (false springs), followed by light or hard freezes. What is the difference between plants that flower and those that wait? What is the impact of freezing on plants in flower? Dr. Savage draws on research by her and people in her lab who are working to help us better understand the physiological

basis of plant phenology and seasonality. Dr. Savsage is a whole plant physiologist with expertise in vascular physiology, floral physiology, phenology, and physiological ecology in seasonally cold climates. She has a strong disposition toward research tied to the phloem. She is an Associate Professor at a primary undergraduate institution and has a passion for mentoring undergraduate and graduate students (especially master’s students). She developed and runs a community-engaged research program focused on tree phenology in coastal forests around Lake Superior and is the Chair of the Physiological and Ecophysiological Section of BSA. Before starting as a faculty member, she was a Putnam Research Fellow at the Arnold Arboretum and a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University. She received her PhD from the University of Minnesota in Plant Biological Sciences.

https://www.buzzsprout.com/2446995/episodes/16870555

From Acorns to Species and the Tree of Life

Andrew L. Hipp

Illustrated by Rachel D. Davis

With a Foreword by Béatrice Chassé

“Hipp comes closer than any other author that I’m aware of to making sense of this bafflingly complex story.”—Quarterly Journal of Forestry

Cloth $35.00

A Story of 24 Hours and 24 Floral Lives

Sandra Knapp

Illustrated by Katie Scott

“Knapp masterfully intertwines the botany, plant biology, history, evolution, and ecology of twenty‑four species.”—Allison Miller, Donald Danforth Plant Science Center and Saint Louis University

EARTH DAY

Cloth $18.00

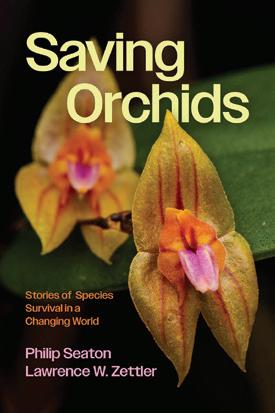

Stories of Species Survival in a Changing World

Philip Seaton and Lawrence W. Zettler

“Seaton and Zettler outline the many mistakes made over the last few centuries that landed us in rather dire straits as well as some of the modern solutions that could be employed by diverse stakeholders.”—Tom Mirenda, coauthor of The Book of Orchids

Cloth $35.00

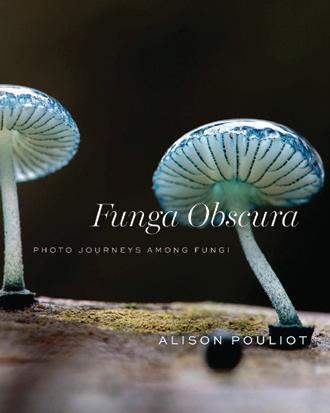

Photo Journeys Among Fungi

Alison Pouliot

“Ecologist and environmental photographer Alison Pouliot has a focus on fungi and her pictures take us across continents and hemispheres.”—Canberra Times

Cloth $28.00

Editorial Committee of the Madrid Code

Contributions by Nicholas J. Turland, et al.

The latest, updated edition of the essential, authoritative reference for botanical, mycological, and phycological names.

REGNUM VEGETABILE

Paper $45.00

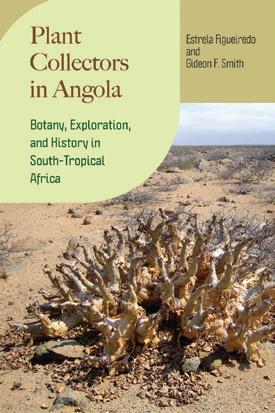

Botany, Exploration, and History in South‑Tropical Africa

Estrela Figueiredo and Gideon F. Smith

“This book fills a serious void in the current knowledge of the botanical history of Africa and will serve as the reference for botanical exploration in Angola.”

—Gerry Moore, botanist

REGNUM VEGETABILE

Paper $45.00

The University of Chicago Press www.press.uchicago.edu

This article, prepared by the International Affairs Committee of the Botanical Society of America, shares personal impressions and valuable insights from attendees of the XX International Botanical Congress (IBC) in Madrid, Spain, which took place in July 2024. The IBC is a pivotal event in the botanical community, drawing researchers, educators, and enthusiasts from around the globe. Held every six years, the IBC provides an environment for discussing the latest advances in plant science and updating the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants—the rules governing the naming of these organisms (Turland, 2025). The XX

By

Shengchen Shan1, Veronica Di Stilio2, Shelley A. James3, Julie F. Barcelona4, Oluwatobi A. Oso5, Funmilola M. Ojo6, Allyssa Richards7, and Elton John de Lirio8

1 Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, United States.

2 Department of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States.

3 Western Australian Herbarium, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Kensington, Australia.

IBC was a large scientific meeting, with 3011 attendees from 95 different countries, 267 symposia, and more than 3000 talks and posters (Gostel et al., 2024)—a daunting event for even a seasoned scientific professional. By summarizing experiences of the meeting from undergraduate and graduate students to senior scientists attending the IBC, we aim to provide guidance for botanists at all career stages for future international scientific

4 School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand.

5 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States.

6 Department of Biological Sciences, Olusegun Agagu University of Science and Technology, Okitipupa, Nigeria.

7 Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA, United States.

8 Instituto Nacional da Mata Atlântica, Santa Teresa, Brazil. Author for correspondence: Elton John de Lirio: lirioeltonj@gmail.com

events. The participants were invited to answer questionnaires before and after the IBC. Key themes include preparation, networking, and navigating the conference’s diverse offerings.

Attendees expressed great excitement about the opportunity to meet global experts and engage with the latest research in plant science. The Congress also offered a unique chance to network with professionals from diverse fields and regions and meet old friends. For example, Natalia Ruiz-Vargas, a graduate student at the University of Illinois at Chicago, hoped to connect with botanists from other countries at IBC, noting, “I have mostly interacted with researchers from the U.S. and Latin America.” In addition, some participants expressed interest in meeting colleagues with specific research interests. David Hoyos, a PhD student at the National University of Córdoba, Argentina, shared, “The most exciting part for me was meeting the most influential botanists in the study of the family Solanaceae.” Similarly, Raúl Pozner, an Independent Investigator with CONICET at the Instituto de Botánica Darwinion in Argentina, said he looked forward to “meeting colleagues that I know by their research articles.”

Preparation is key to maximizing the IBC experience. Participants highlighted the importance of developing talks and posters well in advance, ensuring all travel documents were in order, and managing personal arrangements, such as childcare. Creating a flexible schedule at the Congress that allowed for both planned sessions and spontaneous activities, such as opportunistic conversations

and social interactions, was also crucial. “I’ll prepare my talks, make sure my documents for international traveling are accepted in Spain, and make sure my daughter is fine with us leaving her with her grandparents for a week,” said Thais Vasconcelos, an Assistant Professor at the University of Michigan. Carolyn Ferguson, curator of the K-State Herbarium at Kansas State University, also emphasized, “I’ll catch up with other parts of my work as best as possible so that I can leave that behind and focus on the Congress.”

For large meetings such as the IBC, schedules can be overwhelming, with numerous concurrent sessions. Attendees recommended focusing on a mix of familiar topics as well as areas outside one’s expertise. Flexibility and openness to unexpected discoveries can lead to enriching experiences and new insights.

The attendees noted the difficulty of choosing between simultaneous sessions and managing the physical demands of the event, such as navigating large crowds and adapting to the local climate. Effective time management and prioritization of sessions are essential for overcoming these challenges. Attendees also recommended allowing time for rest and reflection to maintain focus and engagement throughout the Congress. Many participants ventured into sessions outside their primary fields of interest, discovering new techniques and concepts applicable to their research. This willingness to explore unfamiliar areas broadened their scientific thinking and sparked creativity.

“I will try to decide beforehand the sessions I am more interested in. It is a difficult task, because many times there are at least two concurrent sessions that I would like to attend,” said Verónica Di Stilio, Professor at the University of Washington. Carolyn Ferguson mentioned that “using the IBC APP and setting up a schedule” can help navigate the busy program. In addition, participants expressed their desire to support friends and colleagues at IBC, leaving room for those friends who asked you to show up at their talks.

For some participants, learning new research methods was a major factor in deciding which sessions to go to, as well as attending talks that spark excitement and inspiration. Natalia Ruiz-Vargas planned to join sessions that “will be covering methods that I can apply to my research.” Verónica Di Stilio also noted that amongst her goals for attending IBC were “learning new approaches and becoming inspired,” while Raúl Pozner mentioned that he planned to attend talks that “spark his curiosity.”

Networking is also a vital component of any meeting. Informal interactions with fellow attendees at the IBC often led to potential collaborations and new research ideas. These conversations underscore the importance of networking and highlight the unexpected benefits of engaging with a diverse group of botanists. Attendees suggested prioritizing interactions with both peers and senior scientists while remaining open to spontaneous meetings. Techniques such as preparing questions for specific individuals and leveraging informal gatherings can enhance networking outcomes.

“I will prioritize certain colleagues I definitely need to talk to, to start a new collaboration or foster an ongoing one, and I will also allow room for spontaneous encounters. At these meetings, everyone is open to meeting new people, so I think being open and not afraid of introducing oneself to other attendees works well and can lead to pleasant and productive unplanned outcomes,” said Sophie Dauerman, an undergraduate student at Yale University.

Lastly, networking can be challenging for those attending any meeting for the first time. Jay Edneil Olivar, a Filipino postdoctoral researcher at Leipzig University in Germany, reflected on the experience, saying, “To experience it for the first time… I will just try to be myself.”

Attendees shared stories of memorable talks that significantly influenced their perspectives. These presentations often featured innovative research methods and engaging delivery styles, inspiring participants to consider new approaches in their work. The IBC’s setting also offered a rich cultural and professional diversity. Attendees valued the opportunity to learn from colleagues with different backgrounds and approaches, enhancing their understanding of global botanical issues.

“One of the most memorable presentations was Douglas Soltis’ talk about the history of APG (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group), and the way to the upcoming APG V. It represents a huge collaboration effort that impacts the area of plant taxonomy and systematics,” said Gustavo Shimizu, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Campinas, Brazil.

For David Hoyos, the most exciting and memorable talk was by Dr. Hanna Tuomisto on “species-soil relationships and their evolution in Amazonian ferns.” He shared, “I liked that presentation so much because it integrated climate data with evolutionary history in an interesting and important ecosystem like the Amazon.”

Sophie Dauerman really liked “one presentation on the impact of rock climbing on cliff plant communities—something I haven’t thought or heard about before.” And for Jay Edneil Olivar, the most exciting presentation was about “using Taylor Swift’s music videos to teach about botany.”

Participation in such a large-scale event fostered personal growth, with attendees gaining confidence in their communication skills and expanding their professional networks. The experience also highlighted the importance of adaptability and openness in scientific endeavors. David Hoyos, whose research focuses on the Solanaceae family, appreciated the opportunity to speak with Sandra Knapp. “I am sure that it will positively impact my future work because collaborations with her will be possible,” he added. David also saw IBC as a valuable opportunity to “practice and improve his skill in English.” Natalia RuizVargas said that she was able to meet her future postdoctoral principal investigator at IBC.

Following IBC, many participants—despite thorough preparation—shared that the most challenging part of their experience was choosing between overlapping presentations. For example, Sophie Dauerman mentioned the hardest part was “deciding which talks to

go to!” In addition, several attendees reflected on how the IBC differed from conferences in their home countries. David Hoyos noted, “The Madrid IBC has been the biggest academic event in which I have participated.” Similarly, Natalia Ruiz-Vargas said, “IBC was so much more diverse. It was great to meet people from so many different places and learn about their issues, successes, and approaches to problem solving.” Besides the conference itself, our interviewees appreciated their time in Spain. For example, Thais Vasconcelos said, “The cultural experiences in Spain were enjoyable—food, language, and architecture.”

The insights shared by IBC attendees emphasize the importance of preparation, flexibility, and networking in maximizing the Congress experience. Future participants are encouraged to embrace both the opportunities and challenges international conferences present.

The connections and knowledge gained at the IBC have the potential to significantly impact attendees’ future careers and contribute to advancements in the field of botany. As participants reflect on their experiences, they are inspired to continue exploring new ideas and collaborations.

We thank all interviewees (Sophie Dauerman, Verónica Di Stilio, Carolyn Ferguson, David Hoyos, Jay Edneil Olivar, Raúl Pozner, Natalia RuizVargas, Gustavo Shimizu, and Thais Vasconcelos) for their valuable contributions and insights. Some quotes from interviewees were edited for grammar and clarity, without altering the intended meaning. The authors also thank Amy McPherson, Heather Cacanindin, and Susanne Renner for helpful discussion.

Gostel, M. R., R. Deanna, and G. H. Shimizu. 2024. Report from the XX International Botanical Congress, Madrid, Spain, 21–27 July 2024. Taxon 73: 1332–1335.

Turland, N. J. 2025. From the Shenzhen Code to the Madrid Code: New rules and recommendations for naming algae, fungi, and plants. American Journal of Botany 112: e70026.

Madroño - Research Grants - Student Symposia

Madroño is a leading source of research ar ticles on the ecology, systematics, floristics, restoration, and conser vation biology of Western American flora, including those of Mexico, Central and South America.

Society membership includes free online access to Madroño, discounted publication fees per volume year, and much more!

Botany360 is a series of programming that connects our botanical community during the 360 days outside of Botany conferences. The Botany360 event calendar is a tool to highlight those events. The goal of this program is to connect the botanical science community throughout the year with professional development, discussion sessions, and networking and social opportunities. To see the calendar, visit www.botany.org/ calendar. If you want to coordinate a Botany360 event, email aneely@botany.org.

• Prepping for PLANTS: An Informational Webinar about the PLANTS Travel Awards for Underrepresented Undergrads (January 24, 2025) https://youtu.be/wIF6Kbu0XM?si=cIee1JPoeO2jEJJs

By Amelia Neely BSA Membership & Communications Manager

E-mail: ANeely@ botany.org

• BSA Listening and Discussion Session (March 5, 2025)

• Botany on a Budget (May 8, 2025)

• Careers in Botany: Beyond Academia (June 6, 2025)

• Make the most out of Botany 2025: A student conference guide (June 30, 2025)

• And more to come!

Don’t forget that there are more than 20 recordings available for free to access anytime at https://botany.org/home/resources/ botany360.html

The BSA Spotlight Series highlights early-career and professional scientists in the BSA community and shares both scientific goals and achievements, as well as personal interests of the botanical scientists, so you can get to know your BSA community better.

Here are the latest Spotlights:

• Jeffrey James Keeling, Graduate Student, University of Texas at El Paso https://botany.org/home/careers-jobs/careers-in-botany/bsa-spotlight-series/jeffreyjames-keeling.html

• Aaron Lee, Graduate Student, University of Minnesota https://botany.org/home/careers-jobs/careers-in-botany/bsa-spotlight-series/aaron-lee.html

• Joyce G. Onyendeum, Faculty, New York University https://botany.org/home/careers-jobs/careers-in-botany/bsa-spotlight-series/joyce-gonyenedum.html

Would you like to nominate yourself or another BSA member to be in the Spotlight Series? Fill out this form: https://forms.gle/vivajCaCaqQrDL648.

Do you know a business or organization that would benefit from being in front of over 3000 botanical scientists from over 70 countries, and over 48,500 followers on social media? The BSA Business Office has many opportunities for sponsorship including:

• Sponsored Membership Matters newsletter articles and footer ads

• BSA website banner ads

• Hosting Botany360 events

• Sponsored social media ads

• Advertisement space in the Plant Science Bulletin

• Botany360 event logo advertisement during event, a slide before/after event, or time to discuss product at beginning or end of event

Because we value our community, the above opportunities are limited with the hope of being informative without being intrusive. Sponsorships will allow BSA to fulfill our strategic plan goal of being financially responsible during this time of economic shifts.

To find out more about sponsorship opportunities, email bsa-manager@botany.org.

Thank you to all of our Legacy Society members for supporting BSA by including the Society in your planned giving. We look forward to hosting you at this year’s Legacy Society Reception at Botany 2025 in Palm Springs, CA. If you are interested in joining the Legacy Society, you are welcome to come to the event, scheduled for the evening of July 31, and sign up in person. You can also join the Legacy Society at any time during the year by filling out the form at https://crm.botany. org/civicrm/profile/create?gid=46&reset=1 .

The intent of the BSA’s Legacy Society is to ensure a vibrant scientific Society for tomorrow’s botanists, and to assist all members in providing wisely planned giving options. All that is asked is that you remember the Botanical Society of America as a component in your legacy gifts. It’s that simple—no minimum amount, just a simple promise to remember the Society. We hope this allows all BSA members to play a meaningful part in the Society's future. To learn more about the BSA Legacy Society, and how to join, please visit: https://botany.org/home/membership/thebsa-legacy-society.html.

This year marks a special milestone for PlantingScience, a BSA-led educational outreach program that has been inspiring students and supporting science educators for two decades. Since its launch in 2005, PlantingScience has connected middle school, high school, and undergraduate college students with plant scientists in an innovative online mentoring program. Through handson investigations and online conversations

By Dr. Catrina Adams, Education Director Jennifer Hartley, Education Programs Supervisor

with professional scientists, students experience the process of science firsthand while deepening their understanding of and appreciation for the amazing world of plants.

PlantingScience was designed to bring plant scientists into middle- and high-school classrooms so all students have a chance to meet and work with scientists

In 2011, PlantingScience won the SPORE award from the journal Science. The essay “Building Botanical Literacy” (Hemingway et al., 2011; DOI: 10.1126/science.1196979) from that year describes the early history of the program, which was inspired by a 2003 call to action by Bruce Alberts, then president of the National Academy of Sciences, who challenged the BSA to enhance K-12 science classroom experiences. The platform, which

was originally developed and supported in-house by BSA IT Director Rob Brandt, Education Director Claire Hemingway, and Executive Director Bill Dahl, was redeveloped on the HUBzero platform in 2017 (https:// www.rcac.purdue.edu/news/932) to enable larger cohorts, put more tools in the hands of teachers, and enhance the community. Subsequent HUBzero customized updates have improved tools available to participants and streamlined administration and datacuration capabilities (https://www.sdsc.edu/ news/2024/PR20240221_PlantingScience. html). Many of the new features and tools developed for use in PlantingScience have been used by other HUBzero-supported science community hub sites as well.

“I look forward to PS project time every year - it is something that the kids remember and take pride in. Thank you for all that you do! My students loved working with their mentors and hopefully we’ve inspired some future plant scientists!” - PlantingScience teacher

PlantingScience has built a strong community of teachers and scientist mentors who have shared their passion for plants and science with tens of thousands of students

Since its start in 2005, the program has supported over 900 student teams, approximately 36,000 students, and almost 500 teachers. Classrooms in all 50 U.S. states and 9 countries have participated in PlantingScience. Over 1000 plant scientists from 50+ countries have volunteered with the program over the years. The current site’s mentor gallery includes over 700 scientist profiles showcasing the diversity of who plant scientists are and what they do.

In each session, star projects are nominated by mentors, teachers, mentor liaisons, and staff. The best are selected to be shared in the project’s Star Project gallery where they can serve as exemplars and inspire future student teams: https://plantingscience.org/projects/br owse?filterby=archived&featured=1&limit=50

PlantingScience has benefited from generous support from multiple sources

The program has been primarily supported by an $8.35M investment over three National Science Foundation grants from the Division of Research on Learning’s DRK-12 program (DRL 0733280, 2007–2013; DRL 1502892, 2015–2021; DRL 2010556, 2020–2026). This support allowed development and maintenance of the online platform, staff support, research on the effectiveness of the program and student-teacher-scientist partnerships more generally, and professional learning opportunities for teachers and early career scientists.

Generous support from program partners, donors, and sponsors have enabled us to send basic materials to teachers to make the program free to classrooms, and provided prizes to Star Project winners and enabled teacher recruitment (https://plantingscience. org/getinvolved/partners). Partnering scientific societies have provided recruitment and dissemination support, and the American Phytopathological Society (APS), American Society of Agronomy (ASA), American Society of Plant Biologists (ASPB), Canadian Botanical Association (CBA/ABC), Crop Science Society of America (CSSA), Ecological Society of America (ESA), and Soil Science Society of America (SSSA) have joined BSA in supporting the program’s early career scientist liaisons through our Master Plant Science

Program. New module development has also been supported by the American Society of Agronomy (“Agronomy Feeds the World”) and American Phytopathological Society (“Plants Get Sick, Too!”).

“Thanks for the chance to be a liaison again, I’m learning a ton from this experience, from both mentors and their methodology, from students and how they view plants and formulate experiments and the planting science team ability to coordinate something so big each semester and follow through to the end.” - PlantingScience MPST earlycareer liaison

Many, many BSA members and leaders have supported the success of the program by developing, leading, and participating in PlantingScience professional learning with teachers, developing and refining inquiry-based curricular modules on big ideas in plant science, writing support materials, suggesting and testing website improvements, helping teachers to manage mentors, recruiting new mentors, providing financial support, and mentoring students directly.

Research studies show that the program is effective at improving key student outcomes

A number of research studies have been conducted over the years to understand how the PlantingScience student-teacher-scientist partnership program works and to better measure and understand the outcomes of the program. Research has shown that the PlantingScience program can positively affect students’ engagement in inquiry, motivation, and attitudes toward science (Scogin, 2014; Scogin and Stuessy, 2015; Scogin, 2016). A discourse analysis of student-mentor conversations found that online scientist mentors often model for students how scientists integrate

science content and practices in their work (Adams and Hemingway, 2014). A text-based analysis of student responses to an open-ended question found that PlantingScience students most value working with plants, scientist mentors, and having control over their research question (Hemingway et al., 2015). Key insights from previous research highlight the need for professional learning for PlantingScience teachers and mentor liaisons. LeBlanc et al. (2017) found that experienced PlantingScience teachers skillfully talk their students through the inquiry cycle, introducing and emphasizing different science proficiencies at each phase of inquiry. Orchestrating such student experiences requires practice and support. We’ve also learned that differences in the amount, content, and timing of mentoring causes differences in the student experience in PlantingScience (Adams and Hemingway, 2014; Scogin, 2014; Scogin and Stuessy, 2015; Scogin, 2016; Peterson, 2012; Desy et al., 2018).

“[Working] with this team was an incredibly rewarding experience. Not only were they bright, kind, and polite, it was extremely rewarding to see the advice that I was giving them be put to use almost immediately. I loved to see that they readily absorbed and utilized what they learned and that their project turned out to have great results in the end to top it all off.” - PlantingScience mentor

In 2015, BSA was awarded a research grant, “PlantingScience Digging Deeper (DIG),” to conduct a large-scale efficacy study of the program’s Power of Sunlight (photosynthesis and respiration module). Grant partners at BSCS Science Learning helped to develop and deliver collaborative professional learning summer workshops where teachers and early-career scientists could work together to prepare for implementing PlantingScience in

the teachers’ classrooms in fall. Approximately 65 teachers and 3000 students from across the U.S. took part in the randomized control study.

“The more we worked on the projects the more interesting it got. I continued to wonder more and more about plants and had a new question everyday. My mentor constantly asked questions and ideas on how to improve the project. Which kept me more interested throughout the experiment.”

- PlantingScience student

Schools in the study were very similar to the overall U.S. population with respect to student composition. Partners at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs (UCCS) conducted the research analysis and found that students in the PlantingScience treatment group showed greater gains in content knowledge and attitudes about scientists than students in the comparison group (Taylor et al., 2022; Westbrook et al., 2023). The research team produced several videos explaining this study, including quotes from participating teachers and scientists: https://stemforall2017. videohall.com/presentations/922.html ; https://stemforall2018.videohall.com/ presentations/1086.html.

In 2020, BSA received a new research grant, “PlantingScience F2 (F2),” to replicate and extend the results of DIG with a three-arm randomized controlled study to compare the efficacy of online vs. in-person professional learning for teachers and early-career scientists for participation in PlantingScience with students. In addition to studying the impacts of the program on content knowledge and attitudes about scientists, we added an instrument to better understand the program’s impact on students’ interest in studying

plants. We are in the final years of this grant and have just finished data collection and are moving on to analysis, led by the program’s UCCS partners. We intend to have several presentations to share preliminary findings and to get feedback from the PlantingScience community in the next year. Very early results on the impacts of the program on students’ interest in studying plants and how students’ ideas about who scientists are and what they do changed as a result of the mentoring they recieved will be shared at this year’s Botany conference: Monday, July 28, 10:45AM Education and Outreach Paper Session “New Research Supporting the Efficacy of the PlantingScience.org Online Mentoring Program”

As we celebrate the past 20 years of PlantingScience, we’re reminded that the success of this program depends on the support of the incredible community of scientists who make up the BSA and its partners. Thank you to everyone who has shared their time, knowledge, financial support, and passion for plants to support our students! If you’ve never been a mentor, consider joining us and spreading the word to colleagues and friends in the plant sciences. Together, we can cultivate a deeper appreciation for plants in classrooms across the US and around the world. Learn more at www.plantingscience.org.

“[Our mentor] made me have more interest in plants and science because she tells us bout flowers that we didn’t know existed and that shows there is alot more to learn in science.” - PlantingScience student

Adams, C. T., and C. A. Hemingway. 2014. What does online mentorship of secondary science students look like? BioScience 64: 1042–1051.

Desy, E. A., C. T. Adams, T. Mourad, and S. Peterson. 2018. Effect of an online, inquiry- & mentor-based laboratory on science attitudes of students in a concurrent enrollment biology course: The PlantingScience experience. The American Biology Teacher 80: 578–583.

Hemingway, C., W. Dahl, C. Haufler, and C. Stuessy. 2011. Building botanical literacy. Science 331: 1535–1536.

Hemingway, C., C. Adams, and M. Stuhlsatz. 2015. Digital collaborative learning: Identifying what students value. F1000Research 4: 74.

LeBlanc, J. K., B. Cavlazoglu, S. C. Scogin, and C. L. Stuessy. 2017. The art of teacher talk: Examining intersections of the strands of scientific proficiencies and inquiry. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology 5: 171–186.

Peterson, C. A. 2012. Mentored engagement of secondary science students, plant scientists, and teachers in an inquiry-based online learning environment (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (Dissertation No. 3532223).

Scogin, S. C. 2014. Motivating learners in

secondary science classrooms: Analysis of a computer-supported, inquiry-based learning environment using self-determination theory (Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A&M University). Available at: https://oaktrust.library.tamu. edu/handle/1969.1/153419

Scogin, S. C., and C. L. Stuessy. 2015. Encouraging greater student inquiry engagement in science through motivational support by online scientist-mentors. Science Education 99: 312–349.

Scogin, S. C. 2016. Identifying the factors leading to success: How an innovative science curriculum cultivates student motivation. Journal of Science Education and Technology 25: 375–393.

Taylor, J., C. T. Adams, A. Westbrook, J. Creasap-Gee, J. K. Spybrook, S. M. Kowalski, A. L. Gardner, and M. Bloom. 2022. The effect of participation in a student-scientist partnership-based online plant science mentoring community on high school students’ science achievement and attitudes about scientists. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 59: 423-457.

Westbrook, A., C. Adams, and J. A. Taylor. 2023. Digging Deeper into Student-TeacherScientist Partnerships for Improving Student Achievement and Attitudes about Scientists. American Biology Teacher 85: 378-389.

The Master Plant Science Team (MPST) is a unique opportunity for early-career scientists to make a lasting impact on 6th- to 12th-grade science education! As part of the MPST, you’ll provide essential support to teachers as they bring PlantingScience into their classrooms. MPST members share their expertise, facilitate communication between teachers and their students’ mentors, and moderate online student-scientist conversations to ensure students get the most out of the experience! It’s a rewarding way to grow your science communication and leadership skills, connect with a national network of educators and scientists, and champion the next generation of plant thinkers. Learn more (and apply) at https://plantingscience.org/getinvolved/ joinmpst.

The ROOT&SHOOT National Science Foundation Research Coordination Network, a collaboration of six plant science organizations including the BSA, has sponsored a student-organized, free online seminar series titled “Cultivating a Culture of Inclusive Excellence in Plant Sciences.”

The series has included four talks so far in 2025. The first, “Perspectives from Black