AN OPERA GUIDE TO MACBETH

Dear Opera Curious and Opera Lovers alike,

September 19, 2025

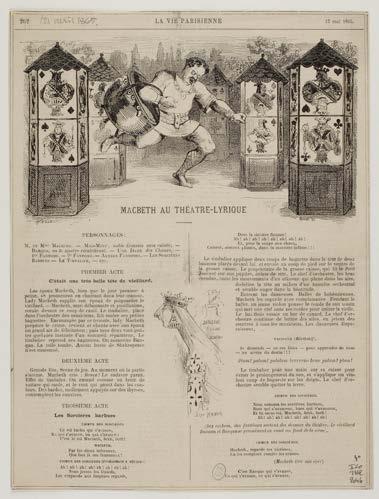

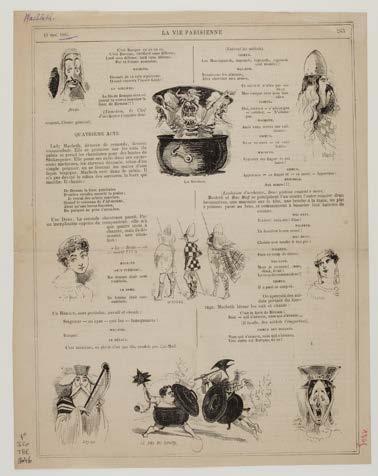

Boston Lyric Opera is thrilled to welcome you to the Emerson Colonial Theatre for our production of Shakespeare’s iconic tragedy with a career-defining score by Giuseppe Verdi: Macbeth.

Opera has a way of tapping into big emotions in a way that’s hard to describe. There’s something incredibly powerful about experiencing the human voice live in the theater, and I believe that whether you’re new to opera or have loved it for years, there’s always something new to discover. To help make your experience even richer, we’ve put together this Guide. It’s designed to give you a little background on Macbeth, its themes, and how these themes resonate today and throughout this production. By providing historical and contemporary context, along with tools to thoughtfully reflect on the opera before or after you attend, we hope to make your experience a memorable one.

Boston Lyric Opera inspires, entertains, and connects communities through compelling performances, programs, and gatherings. Our vision is to create operatic moments that enrich everyday life. As we develop additional Guides, we’re always eager to hear how we can improve your experience. Please tell us about how you use this Guide and how it can best serve your future learning and engagement needs by emailing education@blo.org

If you’re interested in engaging with us further and learning about additional opera education opportunities with Boston Lyric Opera, please visit blo.org/ youth-and-schools to discover our programs and initiatives. We can’t wait to share this experience with you.

Warmly,

Nina Yoshida Nelsen

Artistic Director Boston Lyric Opera

Please note that this synopsis discusses the traditional version of this opera. BLO’s production may be different in some ways.

Macbeth and his friend Banquo, two generals in King Duncan’s army, encounter a group of witches in the woods. The witches prophesize that Macbeth will become king of Scotland, while Banquo – though never to be a king himself – will be the father of future kings. After this encounter, Macbeth and Banquo sing a duet about the prophecies but have very different reactions: Banquo is fearful and distrustful of the witches, while Macbeth becomes curious about this new path towards his future, however bloody it may be.

Verdi then takes us to the Macbeths’ castle. Lady Macbeth has just received a letter from her husband detailing

not only his military successes, but also the prophecy he was given. A messenger announces that King Duncan is accompanying Macbeth home, intending to stay the night. When Macbeth returns, Lady Macbeth persuades him to kill the king in his sleep. After nightfall, Macbeth has a vision of a bloody dagger, which leads him to commit the murder. However, he is immediately remorseful and horrified by what he has done. Lady Macbeth plants evidence to direct suspicion elsewhere. Macduff and Banquo arrive to attend to the king and quickly discover the murder. The castle awakens and, upon the declaration of King Duncan’s death, the chorus calls upon God for vengeance and justice.

Not long after the bloody evening, Macbeth – now king, himself – and Lady Macbeth discuss how they can retain their thrones. Duncan’s son, Malcom, has fled to England from Scotland. The Macbeths realize that since the prophecy about Macbeth becoming king came true, then the prophecy that Banquo’s descendants will be kings must also be true. They decide that Banquo and his son, Fleance, must be killed as well. In a distant park, Banquo and his son are attacked by assassins. While Fleance escapes, Banquo is stabbed to death.

Back at the castle, the Macbeths have prepared a banquet for visiting nobility. One of the assassins appears and tells Macbeth that Banquo is dead. But when Macbeth returns to the banquet, he sees Banquo’s ghost seated in his own place. Lady Macbeth urges her husband to calm down and toast the missing and not-yet-officially-reported-dead Banquo

to avoid arousing suspicion. Banquo’s ghost reappears and Macbeth has another outburst, frightening the guests and making some believe that Macbeth has lost his mind.

The scene shifts to a cave where the witches are gathered around a cauldron. Macbeth appears and begs the witches to tell him of his future. They answer by calling upon three apparitions, each of which gives him a different message. The first apparition warns Macbeth to beware of Macduff, the second declares that no man “born of woman” can harm him, and the third foretells that he will remain in power until Birnam Wood moves against him. A relieved Macbeth celebrates, since “no wood has ever moved by magic power.” Next, he asks the witches if any of Banquo’s descendants will take the throne, and the witches show him a vision of eight future kings, followed by the ghost of Banquo, confirming the original prophecy. Macbeth, either overwhelmed by the information or due to the witches’ manipulation, faints. When he wakes, he is greeted by Lady Macbeth. He tells her what he has learned, and they decide to kill Macduff and his family.

The final act opens on the Scottish/English border with a chorus of Scottish refugees, those who were the most impacted by King Duncan’s war and Macbeth’s violent ascent to power. The chorus sings a sorrowfilled piece, grieving for their war-torn homeland. Malcolm – Duncan’s exiled son – urges Macduff, who is heartbroken by the news of the murder of his wife and children, to lead the English army to avenge their deaths and liberate Scotland from Macbeth’s tyranny. He orders everyone to take branches from the trees of Birnam Wood to disguise themselves as they approach the castle.

Back at the castle, Lady Macbeth is sleepwalking and attempting to clean her hands of blood that isn’t physically there, while the Lady in Waiting and the Doctor look after her. In her sleep, she recounts the horrors of the murders of Banquo, Duncan, and the Macduff family. Meanwhile, Macbeth catches wind that Scottish rebels have joined forces with the English army. While comforted by the witches’ most recent prophecy, he also acknowledges that, even if he wins this battle, he is already hated and feared by the people. The Lady in Waiting rushes in and announces Lady Macbeth’s death. With barely any time to process this, Macbeth also learns that Birnam Wood is in fact moving and that it has arrived at his door. He calls for his shield, sword, and dagger, and joins the fight.

In the final scene of the opera, Macbeth is confronted by Macduff. An overly confident Macbeth declares that “no man born of woman” can harm him. Macduff, however, announces that he was ripped from his mother’s womb early, and Macbeth realizes that he is doomed. The endings of the 1847 version and 1865 version of this opera differ slightly in the details of Macbeth’s death; but ultimately, Macduff emerges triumphant and hails Malcolm as the rightful king. The chorus sings of glory and victory, and Malcolm calls for Scotland to trust him as the new king.

Macbeth – a military general, the Thane of Glamis, future king of Scotland

Lady Macbeth – Macbeth's wife, future queen of Scotland

Macduff – a military general, the Thane of Fife

Banquo – a military general, Macbeth’s friend

Malcolm – King Duncan’s eldest son

Lady in Waiting

Doctor

Duncan – King of Scotland

Three Apparitions

Fleance – Banquo’s son

By Allison Voth, Associate Professor of Music and Principal Coach (Opera Institute) | Boston University

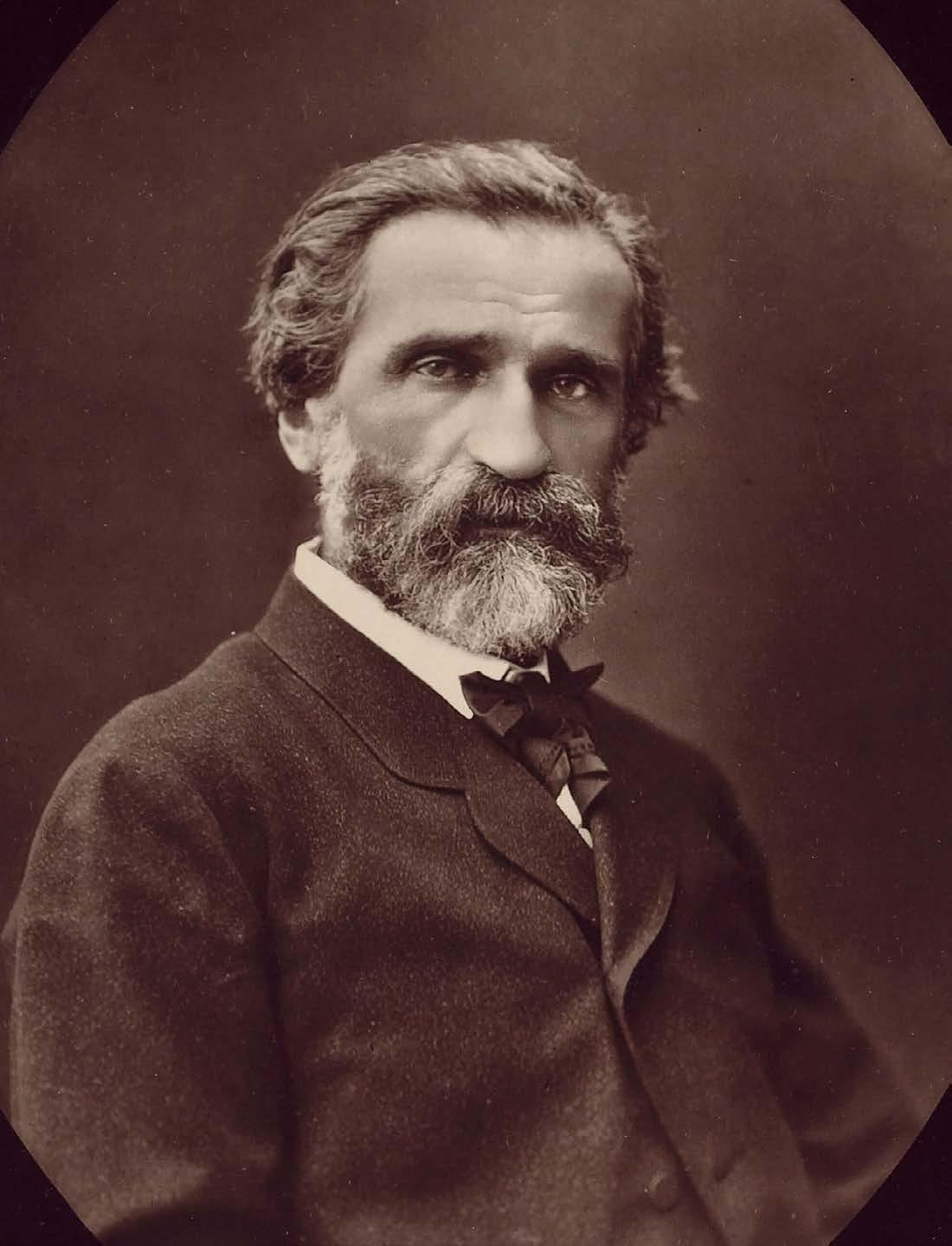

Verdi (“Peppino” to friends) was born on October 10, 1813 in Le Roncole, a small village in northern Italy. Although he was primarily known as an opera composer, he was also a farmer, politician, and philanthropist. His parents were Carlo Verdi, a small land and tavern owner; and Luigia Uttini, a weaver. Curiously, Verdi liked to say that he was from a family of poor peasants and that he was essentially self-taught. All evidence shows that this was not true and that his parents felt strongly about his education from an early age. In fact, when the family’s good friend Pietro Baistrocchi, a schoolmaster and organist, recognized Verdi’s extraordinary intelligence early on, they agreed to let him privately tutor Verdi in Latin and Italian at the tender age of 4. By age 6, Verdi began attending the village school, which Baistrocchi directed.

Verdi’s love for music was also evident at an early age. Any music he heard drew his undivided attention and his enthusiasm led his parents to buy him a spinet, which Verdi kept his entire life. Verdi wrote: “Yes, I did my first lessons on the old spinet, and for my parents it was a large sacrifice to get me this wreck, which was already old at that time; having it made me happier than a king.” Although this is not documented, it is most likely Baistrocchi who introduced Verdi to playing the organ.

In 1823 when Verdi was 10, he was sent to Busseto. Three educated men influenced and guided Verdi during this time in Busseto: Don Pietro Seletti, Ferdinando Provesi, and Antonio Barezzi. Don Pietro Seletti was a well-read priest, Latin and Greek scholar,

Verdi

wrote:

Yes, I did my first lessons on the old spinet, and for my parents it was a large sacrifice to get me this wreck, which was already old at that time; having it made me happier than a king.

archeologist, historian, astronomer, and amateur musician. He was also the director and librarian of the Ginnasio (meaning “school”) that Verdi attended. Seletti recognized Verdi’s musical talents and fully supported his musical studies. Ferdinando Provesi was an organist, composer, teacher of humanities, and head of his own music school that Verdi also attended. Antonio Barezzi was a successful businessman who was also an amateur musician. He took Verdi under his wing and became like a second father to him. He housed Verdi during his last year in Busseto and financially sponsored him on many occasions. Verdi also taught voice and piano lessons to Margherita, Barezzi’s daughter. They fell in love, and Barezzi ultimately became Verdi’s father-in-law.

When Seletti asked him: “Whose

music were

you playing?” Verdi responded:

My own, Signor Maestro. I just played it as it came to me. To which Seletti

replied:

“Go on with it, son. Go on always. Study music. You are right, I will not be the one to tell you to stop. Not after today.”

As mentioned, Verdi attended both Seletti and Provesi’s schools, the former for academics and the latter for music. A rivalry between Seletti and Provesi for Verdi to excel in their respective schools soon grew. To add to the dual school pressure, Verdi also held a church job in his hometown of Le Roncole, to which he walked every Sunday—remember, he was all of 10 when he moved to Busseto! It soon became clear that Verdi was faltering from sheer exhaustion and the pressure of attending both schools, so rather than make Verdi choose between the schools, the two teachers worked together to find ways for Verdi to remain and excel at both schools. Verdi did indeed excel in everything, but as we all know, he chose music as his career.

A pivotal moment that helped all to support his choice came when Verdi was asked by Seletti at the age of 13 to fill in for a prominent, influential musician and landowner who had been hired to play for a special event. Verdi dazzled the audience with his virtuosity. When Seletti asked him: “Whose music were you playing?” Verdi responded: “My own, Signor Maestro. I just played it as it came to me.” To which Seletti replied: “Go on with it, son. Go on always. Study music. You are right, I will not be the one to tell you to stop. Not after today.”

During Verdi’s years in Busseto, he gained a great deal of experience from his involvement with the Busseto Philharmonic Society, to which all three of his mentors belonged. Through this society, he was exposed

to a great deal of repertoire, both standard classical music of the time and new works by various composers, including Seletti and Provesi. Verdi also composed many small works of his own, mostly musica l’occasione—music for specific occasions, both religious and secular. He even wrote an alternate overture for Rossini’s opera Il barbiere di Siviglia. Having the Philharmonia Orchestra and singers at his disposal afforded Verdi the opportunity to experiment and learn at an early age and brought him widespread attention and recognition by age 17. It is notable that during this time, Verdi also delved into the works of the great playwrights both Italian and foreign, including Shakespeare, whose works he greatly admired. These plays instilled in him the importance of the dramatic moment and dramatic pacing. Verdi eventually composed three operas based on Shakespeare’s plays: Macbeth, Otello, and Falstaff

By 1831, it was time for Verdi to move to Milan. His father applied for a scholarship for him to study there, but the funds would not be available until 1833. Barezzi, his benefactor, stepped in and offered to support his move to Milan, which occurred in 1832. Verdi applied to the Milan Conservatory but was rejected on the grounds that he was too old (4 years older than the standard incoming age), not from the area, and he had an unorthodox piano technique. Sadly, Verdi did not fit the standard student profile. Undaunted by the rejection, he chose to study privately with Vincenzo Lavigna, who was the maestro concertatore at La Scala, the famous Italian opera house. Barezzi also paid for Verdi’s lessons. In later years, Verdi complained that Lavigna only taught him counterpoint. Even if this is true, perhaps we have Lavigna to thank for Verdi’s brilliant fugal writing at the ends of both Macbeth and Falstaff!

In 1836, after completing his formal studies, Verdi moved back to Busseto to take on the appointment of maestro di musica of the Philharmonic Society after the death of Provesi. He also married Margherita Barezzi and had two children: Virginia and Icilio Romano. He stayed in Busseto for three years. These years were not particularly happy ones professionally or personally. Verdi and his wife were devastated by the loss of their first child, Virginia, in 1838. Additionally, following Verdi’s earlier years in Busseto, the region had developed pro- and anti-Verdi factions, which created a great deal of ongoing strife for Verdi and his wife. Keep in mind that as talented as Verdi was, he had a reputation for being very difficult, and many resented his entitled and demanding personality. Feeling unwelcome by many in Busseto, Verdi constantly worked at maintaining and creating new

connections in Milan in order to return there. Despite the difficulties, Verdi composed several smaller instrumental and vocal works, as well as two larger works: a cantata for conductor Pietro Massini, as well as his first opera, Oberto

Between 1842 and 1853, a span of 11 years that Verdi referred to as his “galley years,” he composed 16 operas (essentially one every 9 months), collaborating with well-known librettists Temistocle Solera, Francesco Maria Piave, Salvadore Cammarano, and Andrea Maffei.

By 1839, Verdi and Margherita finally returned to Milan. It was a trying year: they lost their second child—Icilio—in October, only eight months after arriving. Professionally, though, one month after his son’s death, Verdi’s opera Oberto finally premiered at La Scala, thanks in part to his connections with Massini. It was so well received that the impresario, Bartolomeo Merelli, offered Verdi a contract for three more operas to be composed over the next two years. Despite this generous and positive turn of events, Verdi once again faced ill fortune when his beloved Margherita died in 1840 and his second opera, Un giorno di regno, failed miserably. Bereft and in a deep depression, Verdi vowed to renounce composing entirely. Fortunately for the world, and perhaps due to music being his only true solace, he broke his vow, and 18 months later composed the opera Nabucco, which was a great success. Between 1842 and 1853, a span of 11 years that Verdi referred to as his “galley years,” he composed 16 operas (essentially one every 9 months), collaborating with well-known librettists Temistocle Solera, Francesco Maria Piave, Salvadore Cammarano, and Andrea Maffei. His last three operas composed between 1849 and 1853 were Rigoletto, Il trovatore, and La traviata, beloved operas still performed regularly to this day. This rich period of creativity made him a revered cultural icon in Italy and firmly established him by age 40 as a renowned opera composer.

In the seven years between 1853 and 1860, Verdi composed only three operas, but he revised three others. He collaborated with three librettists during this period: Eugène Scribe, Antonio Somma, and—again—Francesco Maria Piave. This period marked a shift in his composing toward everbigger orchestrations and greater vocal demands. From 1860 to 1887, Verdi would compose five new operas and make seven revisions: four revisions for Don Carlos, and one each for La forza del destino, Simon Boccanegra, and Macbeth. He also composed his Requiem in honor of the revered Italian writer and patriot Alessandro Manzoni, who died in 1873.

During the 11 years between 1842 and 1853, although Verdi still used many bel canto operatic conventions, he constantly strove to balance the older style—which relied on more predictable, formulaic musical structures—with a freer, more text-oriented, through-composed style. His innovative style often included shortened overtures; tighter, more succinct recitatives which demanded a dramatic delivery, sometimes nearing speech; replacing the tenor lead with a baritone with expanded technical demands—later known as the ‘Verdi baritone’ (higher tessitura, fuller sound with next to no ornamental writing)—adding actual spoken passages; expanding the chorus, giving it more prominence; and most importantly, staying truer to the original stories of the source material, especially when setting the works of great playwrights such as Shakespeare. Up to this point, historically, Rossini and Donzietti—who had greatly influenced Verdi—were very cavalier with original storylines, as were their contemporaries. Verdi rued this lack of respect for the dramatic throughline. He cared deeply about the dramatic flow of his stories, especially those of Shakespeare, whom he revered for his uncanny ability to delve into the human psyche. All the above-mentioned changes were employed to serve the drama of a

work, which Verdi felt came first and foremost. He wrote to the librettist Salvadore Cammarano: "If in the opera there were no cavatinas, duets, trios, choruses, finales, etc., and if the whole work consisted… of a single number, I should find that all the more right and proper.” Verdi never stopped searching for more inventive ways to propel the drama forward and to bring contrast, interest, and depth to the characters. Some of these changes were introduced after he lived in Paris from 18471849 with his newfound life partner, Giuseppina Strepponi, a well-known singer at the time. They also developed further when Verdi began accepting commissions by the French impresario Léon Escudier, who introduced Verdi to Arrigo Boito, a bright young librettist and composer who provided the libretti for his last two operas, Otello and Falstaff

If in the opera there were no cavatinas, duets, trios, choruses, finales, etc., and if the whole work consisted… of a single number, I should find that all the more right and proper. — Verdi

After Paris, Verdi and Streppino moved to Busseto, where they lived a decidedly secluded life until 1851, at which time they moved to Sant’Agata, where they remained for the rest of their lives. Verdi finally married Strepponi in 1859.

From 1859 through 1879, Verdi was also a passionate landowner/farmer. Additionally, he became a significant political figure as an elected official on the provincial council and later the Italian Parliament and Senate. His role was more symbolic than active, but it was an important one for the people who saw Verdi as symbolic of their political struggle for independence from early on.

It is important to note that the Risorgimento movement—the movement for Italian unification—had been growing during Verdi’s lifetime.

During much of the 19th century, Italy was comprised of small states, many of which were governed by foreign rule, including Le Roncole and Busseto which were occupied by

the French at the time of Verdi’s birth. His early opera Nabucco in 1842 included one of Verdi’s most famous choruses—“Va pensiero”—sung by the exiled Hebrew slaves longing for Jerusalem. The Italian people latched onto this chorus, which symbolized their yearning for Italy’s unification and their desire for independence from foreign rule. In the years leading up to Italy’s actual independence in 1861, Verdi was so closely associated with Italy’s fight for independence that his name was used to rally the forces as they chanted: “Viva VERDI.” His name became an acronym, which stood for “(Long live) Vittorio Emmanuele, Re D’Italia!”— the name of the eventual first king of a united Italy.

Verdi’s final years between 1887 and 1901 were spent on charitable work. Despite his reputation for being difficult and fighting constantly with family, friends, and colleagues, he sought ways to support and fight for the less fortunate. He planned and built the hospital Villanova sull’Arda in 1888 and the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti in 1896. Verdi wrote to his friend, Giulio Monteverde:

“Of all my works, that which pleases me the most is the Casa that I had built in Milan to shelter elderly singers who have not been favored by fortune, or who when they were young did not have the virtue of saving their money. Poor and dear companions of my life!”

When Verdi died in 1901, the entire country went into mourning. He was first buried in Milan, but a month later was moved to the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti. Internationally famous conductor Arturo Toscanini led a chorus of more than 800 singers in performing “Va, pensiero” as Verdi’s body was transported through the streets to his final resting place.

Although Verdi’s operas lost some favor in the 1920s, by the 1930s a renewed interest in them surfaced; and by the 1950s, rediscovered works of his were being performed, along with his famous operas. To this day, Verdi’s operas remain in the canon of every major opera house throughout the world, a testament to his legacy as one of opera’s greatest composers. Viva Verdi!

Of all my works, that which pleases me the most is the Casa that I had built in Milan to shelter elderly singers who have not been favored by fortune, or who when they were young did not have the virtue of saving their money. Poor and dear companions of my life! — Verdi

By BLO Staff

Artists are inspired by other artists all the time. In fact, for stage, lighting, costume, and sound designers, such inspiration is often critical. Other artistic mediums – such as visual art forms like paintings – or more three-dimensional art forms, like sculpture and installation art – can help designers discover and decide what the world of a specific opera will look like onstage. These mediums inform choices like paint color, textures and fabric, or even just the mood and environmental tone. It’s not about mimicking or reproducing the artwork, but rather, as Macbeth director Steve Maler describes it, these are forms of “emotional inspiration.” All of these choices, in collaboration with the ideas of other members of the creative team, come together to not only create the playground for the performers on the stage, but also to immerse the audience in the story in heightened, sometimes intangible ways. They quite literally help to set the scene.

For Boston Lyric Opera’s production of Macbeth, two artists in particular inspired stage director Steve Maler and set designer Amy Rubin. Both artists below are ones whose lives were shaped by war, and their lived experience shows up in their work in prominent, haunting ways. The works of Anselm Kiefer and Zhanna Kadyrova were springboards for our creative team to build the world of Macbeth. But who are these artists, and what informed their own creations?

Anselm Kiefer is a German photographer, painter, and sculptor. Born in 1945, Kiefer grew up in postWorld War II Germany after the collapse of the Third Reich. Kiefer first began studying law and Romance languages at the University of Freiburg; however, he soon switched his focus to art, eventually studying under painter Peter Dreher and earning his art degree in 1969. He later studied with the conceptual artist Joseph Beuys.

Anselm Kiefer himself is inspired by other art forms such as literature, crediting much of his inspiration to poets Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann. Kiefer is also inspired by the mythologies and religious traditions from various countries and regions.

Kiefer often works with a variety of materials, such

as dirt, ash, clay, straw, lead, broken glass, concrete, dried plants and flowers, and more. He plays with textures and processes, manipulating materials with things like acid baths, ax marks, and –more traditionally – techniques like impasto, where paint is spread onto the surface of an artist’s pieces in thick, textured layers.

Kiefer is known for confronting history, mythology, and humanity through his large-scale pieces while also imbuing his work with symbolism of hope and resiliency.

The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art writes that “across his body of work, Kiefer argues with history, addressing controversial and even taboo issues from recent history with bold directness and lyricism.” 1

Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova was born in 1981 and is known for her site-specific installations. A graduate of the Taras Shevchenko State Art School, since her formative years she was inspired by the history and contemporary reality of Ukraine. When asked by the publication Tique about her first experience with art, Kadyrova responded:

It happened when following the accident on the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 1986 we were taken away with my sister to Urals, far from our hometown Kyiv. We spent the summer with our grandparents, in their house in the village. One day we found paint cans in the backyard; they were used for painting floors, window frames and doors. Some paint was left at the bottom of each can, sometimes a lot, sometimes less. We

immediately used it by colouring the inner part of the fence, following the principle of making use of everything that was left in the cans at its maximum. When our grandmother saw it she scolded us, and we remembered it for a long time.2

One of the most poignant pieces for the Macbeth creative team was her 2023 project “House of Culture.” In this installation, Kadyrova constructed a small house from shell-damaged building fragments and a salvaged chandelier, all from various cities and regions in Ukraine. Kadyrova wrote in her artistic statement for the piece that the project

...[r]eclaims the notion of the “house of culture” for the Ukrainian people, turning it into a site for the preservation and restoration of cultural heritage. It stands as a monument to all destroyed Ukrainian cultural institutions and, at the same time, as a beacon of light — a symbol of the resilience and survival of art and culture in times of war.3

Inspiration comes in many forms from many places, whether that be a specific art piece or even something as simple as the color of the sky at a certain time of day. The incorporation of these moments of inspiration is not only necessary for production designers to create work that feels alive and relatable to audiences; it’s also one of the qualities that make opera such a special art form. Opera is one of the few art forms that can interweave numerous and diverse mediums simultaneously.

As you watch Macbeth (or any opera!) notice what the designs evoke in you and what emotions emerge. Is the effect unsettling to you? Beautiful? Do you see the past, present, or future on stage? Maybe you will even be inspired by the designers’ work to create art of your own, allowing the lineage of artistic inspiration to continue forward and evolve.

1. “Anselm Kiefer | MASS MoCA.” MASS MoCA | Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, 15 Oct. 2015, massmoca. org/event/anselm-kiefer/.

2. Tique Art. “Six Questions: Zhanna Kadyrova * Tique | Publication on Contemporary Art.” Tique | Publication on Contemporary Art, 2016, tique.art/interviews/six-questions/zhanna-kadyrova/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2025.

3. Kadyrova, Zhanna. House of Culture 2023. 2023, www.kadyrova.com/house-of-culture-2023. Accessed 24 Sept. 2025.

By Kira Troilo, Art & Soul Consulting

“Unsex me here.” With that one command, Lady Macbeth becomes unforgettable. She strips herself of softness, of limitation, of what the world tells her it means to be a woman. But instead of celebrating her clarity of vision and force of will, history has mostly punished her for it. That punishment—psychological torment, madness, death—has been handed down for centuries as the inevitable fate of ambitious women. And that deserves a second (or thousandth) glance.

At Boston Lyric Opera, I planned to sit with the Macbeth cast and do exactly that: to ask what it means to play a character like Lady Macbeth in 2025, how we might choose to study her with fresh eyes, and what responsibility we have to engage in nuanced, thoughtful storytelling.

Preserving Brilliance, Interrogating Bias

Working on stories like Macbeth means holding two things at once: reverence for Shakespeare’s brilliance—and—a responsibility to interrogate the biases baked into these characters.

Lady Macbeth is dazzling—her language, her daring, her presence onstage. Truly any actor’s dream to play. But she also carries centuries of baggage, a shorthand for women who “want too much.” My work with Art & Soul has always been about building brave, creative spaces where we

don’t look away from that baggage. We preserve the brilliance and ask the harder questions: What do we want modern audiences to see in her? What does it mean when ambition in a woman still reads as dangerous?

Lady Macbeth is the embodiment of the double bind women in leadership still face. Be bold, and you’re branded as cold. Be strategic, and you’re calculating. Be vulnerable, and you’re too emotional. Hillary Clinton lived this bind in public view—always either too much or not enough.

The statistics tell us that the bind has real impact: women hold only about 30% of global leadership roles; in Fortune 500 companies, just 10% of CEOs are women. In arts leadership, women of color occupy only 4% of executive seats. Lady Macbeth might be centuries old, but the walls she ran up against still stand tall today.

There’s another piece of the story we need to name: internalized bias. Women themselves have been taught to fear or resent ambition in each other. Research shows that ambitious women are judged more harshly not only by men but by women, too—seen as less likable, less trustworthy. That divide keeps us from solidarity and keeps systems intact. Lady Macbeth reflects this dynamic: a woman both admired and despised, her drive turned against her rather than being recognized as deeply human.

Opera and theatre aren’t just entertainment; they’re mirrors. When ambitious women are constantly written as monsters or martyrs, audiences internalize that message, too. Social justice requires nuance— the courage to show women as whole, complicated, brilliant, and—yes—ambitious, without making their power the poison in the story. That’s the work we must do together: to tell old stories in new ways that honor both the art and the truth of women’s lives. And that’s just one example of the many challenges— and thrills—of live theatre.

I believe this is where the magic of brave space design comes alive most. When artists step into roles like Lady Macbeth, they deserve room to wrestle with the contradictions, the stereotypes, and the humanity, in conversation with their collaborators. When audiences sit down at Boston Lyric Opera, they deserve the chance to question not only Shakespeare’s world, but also their own assumptions. Does Lady Macbeth strike differently in 2025?

Ambition is not the enemy. What we must resist is lazy storytelling that insists women can only be punished for their power. The real task—onstage, in politics, in boardrooms—is to widen the lens, so ambition in women is recognized for what it truly is: human, complex, necessary, and worth celebrating.

While we all love the arias and duets, it is Verdi’s big set piece ensembles that really thrill and move me. He builds up the story and relationships through each act, but the drama culminates with wonderful dramatic finales, featuring several soloists and the big chorus. Both acts 1 and 2 of Macbeth do this, and I know from experience that when we reach these I can just stand in the pit and thank my lucky stars that my job is to be in control of these masterpieces.

I think the act 1 finale is probably my favorite moment in the whole opera, as the cast and crowd react to the death of King Duncan. At first, the soloists sing together a cappella (unaccompanied) and then we move into a huge passionate crowd scene, beginning with a heartfelt unison repeated phrase which builds up and rises to a climax, only to repeat and arrive even more excitingly at the final coda. This all begins at around 2.5 minutes into track 8 of my favorite recording - Shirley Verrett and Claudio Abbado - or about 5.5 minutes before the end of act 1 in any recording you like!

As a bonus, for another huge ensemble showing similar power and passion, listen to the end of act 2, when Macbeth is going crazy about having arranged the death of Banquo, imagining that Banquo’s ghost is still attending his dinner party. Track 15 of the Abbado recording is the last part of the finale, and the big choral ensemble begins about 3 minutes in, or 4 minutes before the end of act 2 in any recording.

We will be performing in the Emerson Colonial Theatre with the orchestra very visible and audible—which can make my job difficult when we are trying to balance to the singers—but which makes it possible for any orchestral sections without singers to be full power and colorful. One of my favorite moments is when Verdi uses the brass to full effect in act 3, when Macbeth is consulting the witches again, and they summon up the powers of darkness with a thrilling sound, using one of my favorite instruments, the cimbasso. A normal tuba has a conical bore—like all brass band instruments such as cornets and euphoniums—and so has a soft, fat sound. Trumpets and trombones have a cylindrical bore, so the sound is tighter and more focused, with an exciting brilliance. The cimbasso is the exact equivalent of a tuba, but with this same narrow bore and brilliance of sound, and it is played by our tuba player. Please have a look for it in the orchestra when you come to see our performances. It is an extra large trombone, supported on a stand. Just listen to the fantastic sound that it makes! On my favorite recording with Abbado, track 18, after 1.5 minutes you will hear a tremendous brass attack. I recommend listening to it on big speakers or headphones, because your phone or computer speakers won’t do it justice! This 50-year-old recording is still spine-tingling.

My final choice of excerpt is another big choral moment, at the opening of act 4. The chorus are Scottish refugees, persecuted by Macbeth and his forces, and this chorus is as moving as anything that Verdi wrote. It begins, as so often with big Verdi choruses, very quietly and simply, but builds up into a very powerful climax before it relents and leads into one of my favorite arias—Macduff’s lament for his family, who were assassinated on Macbeth’s orders. This is track 22 on the Abbado recording.

Macbeth is a relatively early opera in Verdi’s output, but he realized how significant it was. There is no doubt that it is a very powerful and dramatic work with wonderful colors from the orchestra, huge passionate choruses, and of course wonderful writing for the soloists that communicates the depth of the drama and leaves us with melodies and theatrical moments that will linger long after the performances.

• What instruments do you hear?

• How fast is the music? Are there sudden changes in speed? Is the rhythm steady or unsteady?

• Key/Mode: Is it major or minor? (Does it sound bright, happy, sad, urgent, dangerous?)

• Dynamics/Volume: Is the music loud or soft? Are there sudden changes in volume (either in the voice or orchestra)?

• What is the shape of the melodic line? Does the voice move smoothly, or does it make frequent or erratic jumps? Do the vocal lines move noticeably downward or upward?

• Does the type of voice singing (baritone, soprano, tenor, mezzo, etc.) have an effect on you as a listener?

• Do the melodies end as you would expect, or do they surprise you?

• How does the music make you feel? What effect do the factors above have on you as a listener?

• What is the orchestra doing in contrast to the voice? How do the two interact?

• What kinds of images, settings, or emotions come to mind? Does it remind you of anything you have experienced in your own life?

• Do particularly emphatic notes (low, high, held, etc.) correspond to dramatic moments?

• What type of character (romantic, comic, serious, etc.) fits this music?

Essays and Articles:

Sound and fury, signifying something: singing

Verdi's Macbeth

Verdi's Macbeth: "The opera without a love affair!"

James Conlon: Why Verdi's "Macbeth" Is Important

Verdi's Favorite Opera: Macbeth

The witches and the witch: Verdi's Macbeth

Macbeth by William Shakespeare: a timeless exploration of violence and treachery

The Curse of the Scottish Play: Royal Shakespeare Company

The Tragedy of Lady Macbeth

The Role of Lady Macbeth in Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Lady Macbeth's Night Walking With Dissociative Symptoms Diagnosed by the First Sleep Medicine Record

Books:

Oxford Literature Companions: Macbeth by Su Fielder and Peter Buckroyd

Shakespeare on Stage: Thirteen Leading Actors on Thirteen Key Roles by Julian Curry

Women of Will: Following the Feminine in Shakespeare’s Plays by Tina Packer

Macbeth: A True Story by Fiona Watson

Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics by Stephen Greenblatt

PODCAST: "Is there a Real Macbeth Curse?"Stuff You Missed in History Class Podcast

PODCAST: Approaching Shakespeare: Macbeth

The Scottish Play: Race and Nation in "Macbeth"

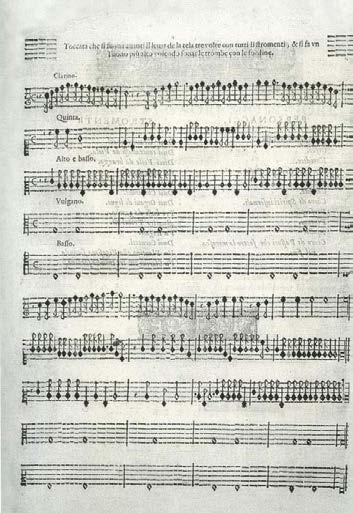

People have been telling stories through music for millennia throughout the world. Opera is an art form that is over 400 years old, with roots in Western Europe. Here is a brief timeline of its lineage.

Please note that all date ranges for these time periods are approximate, and notice that some even overlap.

1573 The Florentine Camerata was founded in Italy, devoted to reviving ancient Greek musical traditions, including sung drama.

1598 Jacopo Peri (1561-1633), a member of the Camerata, composed the world’s first opera –Dafne – reviving the classic myth.

1607 Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) wrote L’Orfeo, the first opera to become popular, marking him as the premier opera composer of his day and bridging the gap between Renaissance and Baroque music. His works are still performed today.

1637 The first public opera house, Teatro San Cassiano, was built in Venice, Italy.

1673 Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687), an Italian-born composer, brought opera to the French court, creating a unique style, tragédie en musique, that better suited the French language. Blurring the lines between recitative and aria, he created fast-paced dramas to suit the tastes of French aristocrats.

1689 Henry Purcell’s (1659-1695) simple and elegant chamber opera, Dido and Aeneas, premiered at Josias Priest’s boarding school for girls in London.

1712 George Frederic Handel (16851759), a German-born composer, moved to London, where he found immense success writing intricate and highly ornamented Italian opera seria (serious opera). Ornamentation refers to stylized, fast-moving notes, usually improvised by the singer to make a musical line more interesting and to showcase their vocal talent.

1750s A reform movement, led by Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787), rejected the flashy ornamented style of the Baroque in favor of simple, refined music to enhance the drama.

1805 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), although a prolific composer, wrote only one opera, Fidelio. The extremes of musical expression in Beethoven’s music pushed the boundaries in the late Classical period and inspired generations of Romantic composers.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) wrote his first opera at age 11, beginning his 25-year opera career. Mozart mastered and then innovated in several operatic forms. He wrote opera serias (serious operas), including La Clemenza di Tito; and opera buffas (comedic operas) like Le Nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). He then combined the two genres in Don Giovanni, calling it dramma giocoso (comedic drama). Mozart also innovated the Singspiel, a German sung play featuring spoken dialogue, as in Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute).

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) composed Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville), becoming the most prodigious opera composer in Italy by age 24. He wrote 39 operas in 20 years. A new compositional style created by Rossini and his contemporaries, including Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini, would, a century later, be referred to as bel canto (beautiful singing). Bel canto compositions were inspired by the nuanced vocal capabilities of the human voice and its expressive potential. Composers employed strategic use of register, the push and pull of tempo (rubato), extremely smooth and connected phrases (legato), and vocal glides (portamento).

1853 Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) completed La Traviata, a story of love, loss, and the struggle of average people, in the increasingly popular realistic style of verismo. Verdi enjoyed immense acclaim during his lifetime, while expanding opera to include larger orchestras, extravagant sets and costumes, and more highly trained voices.

1842 Inspired by the risqué popular entertainment of French vaudeville, Hervé (1825-1892) created the first operetta, a short comedic musical drama with spoken dialogue. Responding to popular trends, this new form stood in contrast to the increasingly serious and dramatic works at the grand Parisian opera house. Opéra comique as a genre was often not comic, tending to be more realistic or humanistic instead. Grand opera, on the contrary, was exaggerated and melodramatic.

1865 Richard Wagner’s (1813-1883) Tristan und Isolde was the beginning of musical modernism, pushing the use of traditional harmony to its extreme. His massively ambitious, lengthy operas, often based in German folklore, sought to synthesize music, theatre, poetry, and visuals in what he called a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). The most famous of these was an epic four-opera drama, Der Ring des Nibelungen, which took him 26 years to write and was completed in 1874.

1871 Influenced by French operetta, English librettist W.S. Gilbert (1836-1911) and composer Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) began their 25-year partnership, which produced 14 comic operettas, including The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado. Their works inspired the genre of American musical theatre.

Johann Strauss II, (1825-1899) influenced largely by his father, with whom he shared a name and talent, composed Die Fledermaus, popularizing Viennese musical traditions, namely the waltz, and further shaping operetta

1896

Giacomo Puccini’s (1858-1924) La bohème captivated audiences with its intensely beautiful music, realism, and raw emotion. Puccini enjoyed huge acclaim during his lifetime for his works.

1911 Scott Joplin, (1868-1917) “The King of Ragtime,” wrote his only opera, Treemonisha, which was not performed until 1972. The work combined the European lateRomantic operatic style with African American folk songs, spirituals, and dances. The libretto, also by Joplin, was written at a time when when African Americans in the southern United States rarely had access to literacy resources and education.

1927 American musical theatre, commonly referred to as Broadway, was taken more seriously after Jerome Kern’s (1885-1945) Show Boat, with words by Oscar Hammerstein II (1895-1960), tackled issues of racial segregation and the ban on interracial marriage in Mississippi.

Alban Berg (1885-1935) composed the first completely atonal opera, Wozzeck, dealing with uncomfortable themes of militarism and social exploitation. Wozzeck is in the style of 12-tone music, or serialism. This new compositional style, developed in Vienna by composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), placed equal importance on each of the 12 pitches in a chromatic scale (all half steps), removing the sense of the music being in a particular key.

British composer Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) gained international recognition with his opera Peter Grimes. Britten, along with Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), was one of the first British opera composers to gain fame in nearly 300 years.

John Adams (b. 1947) composed one of the great minimalist operas, Nixon in China, the story of Nixon’s 1972 meeting with Chinese leader Mao Zedong. Musical minimalism strips music down to its essential elements, usually featuring a great deal of repetition with slight variations.

1935 American composer George Gershwin (1898-1937), who was influenced by African American music and culture, debuted his opera, Porgy and Bess, in Boston, MA with an allAfrican American cast of classically trained singers. His contemporary, William Grant Still (1895-1978), a master of European grand opera, fused that with the African American experience and mythology. His first opera, Blue Steel, premiered in 1934, one year before Porgy and Bess.

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990), known for synthesizing musical genres, brought together the best of American musical theatre, opera, and ballet in West Side Story, a reimagining of Romeo and Juliet in a contemporary setting.

Anthony Davis (b. 1951) premiered his first of many operas, X: The Life and Time of Malcom X, which reclaims stories of Black historical figures within the theatre space. He incorporated both the orchestral and vocal techniques of jazz and classical European opera in his score for a distinctly American sound, and a fully realized vision of how jazz and opera are in conversation within a work.

Still a vibrant, evolving art form, opera attracts contemporary composers such as Philip Glass (b. 1937), Jake Heggie (b. 1961), Terence Blanchard (b. 1962), Ellen Reid (b. 1983), and many others. Composers continue to be influenced by present and historical musical forms in creating new operas that explore current issues or reimagine ancient tales.

Opera is unique among forms of singing in that singers are trained to be able to sing without amplification, in large theaters, over an entire orchestra, and still be heard and understood! This is what sets the art form of opera apart from similar forms such as musical theatre. To become a professional opera singer, it takes years of intense physical training and constant practice — not unlike that of a ballet dancer — to stay in shape. Poor health, especially respiratory issues and even allergies, can be severely debilitating for a professional opera singer. Let’s peek into some of the science of this art form.

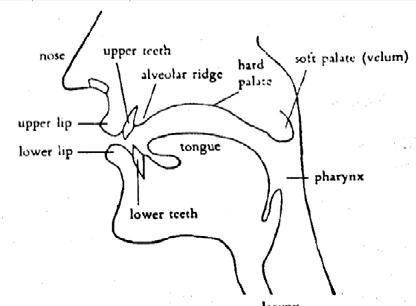

Singing requires different parts of the body to work together: the lungs, the vocal cords, the vocal tract, and the articulators (lips, teeth, and tongue). The lungs create a flow of air over the vocal cords, which vibrate. That vibration is amplified by the vocal tract and broken up into words by consonants, which are shaped by the articulators.

Any good singer will tell you that good breath support is essential to produce quality sound. Breath is like the gas that goes into your car. Without it, nothing runs. In order to sing long phrases of music with clarity and volume, opera singers access their full lung capacity by keeping their torso elongated and releasing the lower abdomen and diaphragm muscles, which allows air to enter into the lower lobes of the lungs. This is why we associate a certain posture with opera singers. In the past, many operas were staged with singers standing in one place to deliver an entire aria or scene, with minimal activity. Modern productions, however, often demand a much greater range of movement and agility onstage, requiring performers to be physically versatile, and bringing more visual interest, authenticity of expression, and nuanced acting into the storytelling.

If you run your fingers along your throat, you will feel a little lump just underneath your chin. That is your “Adam’s Apple,” and right behind it, housed in the larynx (voice-box), are your vocal cords. When air from the lungs crosses over the vocal cords it creates an area of low pressure (Google The Bernoulli Effect), which brings the cords together and makes them vibrate. This vibration produces a buzz. The vocal chords can be lengthened or shortened by muscles in the larynx, or by changing the speed of air flow. This change in the length and thickness of the vocal cords is what allows singers to create different pitches. Higher pitches require long, thin cords, while low pitches require short, thick ones. Professional singers take great pains to protect the delicate anatomy of their vocal cords with hydration and rest, as the tiniest scarring or inflammation can have noticeable effects on the quality of sound produced.

Without the resonating chambers in the head, the buzzing of the vocal cords would sound very unpleasant. The vocal tract, a term encompassing the mouth cavity, and the back of the throat, down to the larynx, shapes the buzzing of the vocal cords like a sculptor shapes clay. Shape your mouth in an ee vowel (as in eat), then sharply inhale a few times. The cool sensation you feel at the top and back of your mouth is your soft palate. The soft palate can raise or lower to change the shape of the vocal tract. Opera singers often sing with a raised soft palate, which allows for the greatest amplification of the sound produced by the vocal cords. Different vowel sounds are produced by raising or lowering the tongue, and changing the shape of the lips. Say the vowels: ee, eh, ah, oh, oo and notice how each vowel requires a slightly lower tongue placement and slightly rounder lips. This area of vocal training is particularly difficult because none of the anatomy is visible from the outside!

The lips, teeth, and tongue are all used to create consonant sounds, which separate words into syllables and make language intelligible. Consonants must be clear and audible for the singer to be understood. Because opera singers do not sing with amplification, their articulation must be particularly good. The challenge lies in producing crisp, rapid consonants without interrupting the connection of the vowels (through the controlled exhalation of breath) within the musical phrase.

Perfecting every element of this complex singing system requires years of training and is essential for the demands of the art form. An opera singer must be capable of singing for hours at a time, over the powerful volume of an orchestra, in large opera houses, while acting and delivering an artistic interpretation of the music. It is complete and total engagement of mental, physical, and emotional control and expression. Therefore, think of opera singers as the Olympic athletes of the stage, sit back, and marvel at what the human body is capable of!

Opera singers are cast into roles based on their tessitura (the range of notes they can sing most comfortably and effectively). There are many descriptors that accompany the basic voice types, but here are some of the most common ones:

The lowest voice, basses often fall into two main categories: basso buffo, which is a comic character who often sings in lower laughing-like tones, and basso profundo, which is as low as the human voice can sing! Doctor Bartolo is an example of a bass role in The Barber of Seville by Rossini.

A middle-range lower voice, baritones can range from sweet and mild in tone, to darker dramatic and full tones. A famous baritone role is Rigoletto in Verdi’s Rigoletto. Baritones who are most comfortable in a slightly lower range are known as Bass-Baritones, a hybrid of the two lowest voice types.

The highest of the lower-range voices, tenors often sing the role of the hero. One of the most famous tenor roles is Roméo in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette. Sometimes, singers with lower-range voices also cultivate much higher ranges, singing in a range similar to a mezzo-soprano or soprano by using their falsetto register. Called the Countertenor, this voice type is often found in Baroque music. Countertenors replaced castrati in the heroic lead roles of Baroque opera after the practice of castration was deemed unethical.

Each of the voice types (soprano, mezzo-soprano, tenor, baritone, bass) also tends to be sub-characterized by tone descriptors such as “lyric” or “dramatic.” Lyric singers tend toward smooth lines in their music, sensitively expressed interpretation, and flexible agility. Dramatic singers have qualities that are attributed to darker, fuller, richer note qualities expressed powerfully and robustly with strong emotion. While it’s easiest to understand operatic voice types through these designations and descriptions, one of the most exciting things about listening to a singer perform is that each individual’s voice is essentially unique, so each singer will interpret a role in an opera in a slightly different way.

The lowest of the higher treble voices has a low range that overlaps with the highest tenor’s range. This voice type is less common.

Somewhat equivalent to an alto role in a chorus, mezzo-sopranos (mezzo meaning “middle”) are known for their full and expressive qualities. While they don’t sing frequencies quite as high as sopranos, their ranges do overlap, and it is a “darker” tone that sets them apart. One of the most famous mezzo-soprano lead roles is Carmen in Bizet’s Carmen

The highest voice. Some subtypes of the soprano voice include coloratura, lyric, and dramatic sopranos. Coloratura sopranos specialize in being able to sing fast-moving notes that are very high in frequency, often referred to as “color notes.” One of the most famous coloratura roles is the Queen of the Night in Mozart’s The Magic Flute.

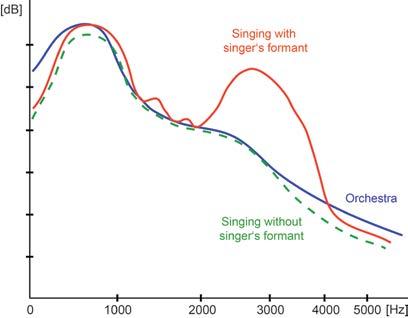

What is it about opera singers that allows them to be heard above the orchestra? It’s not that they simply singing louder. The qualities of sound have to do with the relationship between the frequency (pitch) of a sound, represented in a unit of measurement called hertz, and its amplitude, measured in decibels, which the ear perceives as loudness. Only artificially produced sounds, however, create a pure frequency and amplitude (these are the only kind that can break glass). The sound produced by a violin, a drum, a voice, or even smacking your hand on a table, produces a fundamental frequency as well as secondary, tertiary, etc. frequencies known as overtones, or as musicians call them, harmonics

The orchestra tunes to a concert “A” pitch before a performance. Concert “A” has a frequency of about 440 hertz, but that is not the only pitch you will hear. Progressively softer pitches above that fundamental pitch are produced in multiples of 440 at 880hz, 1320hz, 1760hz, etc. Each different instrument in the orchestra, because of its shape, construction, and mode in which it produces sound, produces different harmonics. This is what makes a violin, for example, have a different color (or timbre ) from a trumpet. Generally, the harmonics of the instruments in the orchestra fade around 2500hz. Overtones produced by a human voice—whether speaking, yelling, or singing— are referred to as formants

As the demands of opera stars increased, vocal teachers discovered that by manipulating the empty space within the vocal tract, they could emphasize higher frequencies within the overtone series—frequencies above 2500hz. This technique allowed singers to perform without hurting their vocal cords, as they are not actually singing at a higher fundamental decibel level than the orchestra. Swedish voice scientist Johan Sundberg observed this phenomenon when he recorded the world-famous tenor Jussi Bjoerling in 1970. His research showed multiple peaks in decibel level, with the strongest frequency (overtone) falling between 2500 and 3000 hertz. This frequency, known as the singer’s formant , is the “sweet spot” for singers so that we hear their voices soaring over the orchestra into the opera house night after night.

that are specific to each particular

like a

When two people sing the same note simultaneously, the high overtones allow your ear to distinguish two voices.

The final piece of the puzzle in creating the perfect operatic sound is the opera house or theater itself. Designing the perfect acoustical space can be an almost impossible task, one which requires tremendous knowledge of science, engineering, and architecture, as well as an artistic sensibility. The goal of the acoustician is to make sure that everyone in the audience can clearly understand the music being produced onstage, no matter where they are sitting. A perfectly designed opera house or concert hall (for non-amplified sound) functions almost like gigantic musical instrument.

Reverberation is one key aspect in making a singer’s words intelligible or an orchestra’s melodies clear. Imagine the sound your voice would make in the shower or a cave. The echo you hear is reverberation caused by the large, hard, smooth surfaces. Too much reverberation (bouncing sound waves) can make words difficult to understand. Resonant vowel sounds overlap as they bounce off hard surfaces and cover up quieter consonant sounds. In these environments, sound carries a long way but becomes unclear or — as it is sometimes called — wet, as if the sound were underwater. Acousticians can mitigate these effects by covering smooth surfaces with textured materials like fabric, perforated metal, or diffusers, which absorb and disperse sound. These tools, however, must be used carefully, as too much absorption can make a space dry — meaning the sound onstage will not carry at all and the performers may have trouble even hearing themselves as they

perform. Imagine singing into a pillow or under a blanket.

The shape of the room itself also contributes to the way the audience perceives the music. Most large performance spaces are shaped like a bell – small where the stage is and growing larger and more spread out in every dimension as one moves farther away. This shape helps to create a clear path for the sound to every seat. In designing concert halls or opera houses, big decisions must be made about the construction of the building based on acoustical needs.

Even with the best planning, the perfect acoustic is not guaranteed, but professionals are constantly learning and adapting new scientific knowledge to enhance the audience’s experience.

You will see a full dress rehearsal – an insider’s look into the final moments of preparation before an opera premieres. The singers will be in full costume and makeup, the opera will be fully staged, and an orchestra will accompany the singers, who may choose to “mark,” or not sing in full voice, to save their voices for the performances. A final dress rehearsal is often a complete run-through, but there is a chance the director or conductor will ask to repeat a scene or section of music. This is the last opportunity the performers have to rehearse with the orchestra before opening night, and they therefore need this valuable time to work. The following will help you better enjoy your experience of a night at the opera:

• Arrive on time! Latecomers will be seated only at suitable breaks in the performance and often not until intermission.

• Dress in what you are comfortable in so you can enjoy the performance. For some, that may mean dressing up in a suit or gown; for others, jeans and a t-shirt is fine. Generally, “dressycasual” is what people wear. Live theatre is usually a little more formal than a movie theater.

• At the very beginning of the opera, the concertmaster of the orchestra will ask the oboist to play the note “A.” You will hear all the other musicians in the orchestra tune their instruments to match the oboe’s “A.”

• After all the instruments are tuned, the conductor will arrive. You can applaud to welcome them!

• Feel free to applaud or shout "Bravo!" at the end of an aria or chorus piece if you really liked it. The end of a piece can usually be identified by a pause in the music. Singers love an appreciative audience!

• It’s OK to laugh when something is funny or gasp at something shocking!

• When translating songs, and poetry in particular, much can be lost due to a change in rhythm, inflection, and rhyme of words. For this reason, opera is usually performed in its original language. In order to help audiences enjoy the music and follow every twist and turn of the plot, English supertitles are projected. Even when the opera is in English, there are still supertitles.

• Listen for subtleties in the music. The tempo, volume, and complexity of the music and singing depict the feelings or actions of the characters. Also, pay attention to repeated words or phrases; they are usually significant.

The singers, orchestra, dancers, and stage crew are all hard at work to create an amazing performance for you! Here’s how you can help them.

• Lit screens are very distracting to the singers, so please keep your phone off and out of sight until the house lights come up.

• Due to how distracting electronics can be for performers, taking photos or making audio or video recordings is strictly forbidden.

The theater is a shared space, so please be courteous to your neighbors!

• Please do not take off your shoes or put your feet on the seat in front of you.

• Respect your fellow opera lovers by not leaning forward in your seat so as to block the person’s view behind you.

• Do not chew gum, eat, or drink while the rehearsal is in session. Not only can it pull focus from the performance, but the ushers are not there to clean up after you.

• If you must visit the restroom during the performance, please exit quickly and quietly.

Otherwise, sit back, relax, and let the action onstage pull you in. As an audience member, you are essential to the art form of opera — without you, there is no show!

Have Fun and Enjoy the Opera!