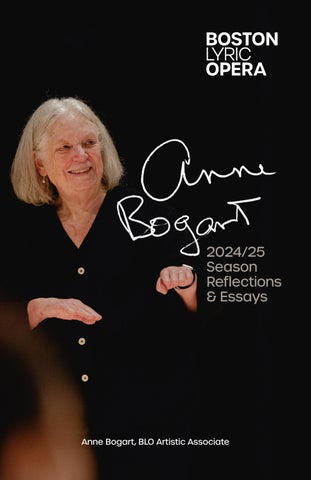

From her iconic interpretation of The Handmaid’s Tale to her masterful fusion of Bluebeard’s Castle with Alma Mahler’s Four Songs, Anne Bogart has brought her imaginative and thought-provoking touch to Boston Lyric Opera’s productions time and time again. As both a stage director and BLO’s Artistic Associate, she has been a frequent and long-standing collaborative partner whom we value deeply.

A central theme in Anne’s work — and in this collection of her dramaturgical notes — is the idea that art and artists act as both mirrors and drivers of cultural change. Her writing allows us to offer some behind-the-scenes insight into not only what made each of this season’s productions stand out, but also the process by which an artist may engage with their work and intended audiences. Please enjoy this special collection of Anne’s astute commentary on the six productions comprising our 2024/25 Season. We look forward to welcoming her — and you, our valued supporters — back for 2025/26!

Anne Bogart is Boston Lyric Opera’s Artistic Associate and most recently worked as stage director for the company’s production of Carousel. Previous notable productions with BLO include Bluebeard’s Castle | Four Songs and The Handmaid’s Tale.

A professor at Columbia University, where she runs the graduate directing program, Bogart is the author of six books: A Director Prepares; The Viewpoints Book; And Then, You Act; Conversations with Anne; What’s the Story; and The Art of Resonance.

Recent theatre works with SITI Company include Falling and Loving; The Bacchae; the theater is a blank page; Persians; Steel Hammer; A Rite; Café Variations; Trojan Women; American Document; Antigone; Freshwater Under Construction; Who Do You Think You Are; Radio Macbeth; Hotel Cassiopeia; Death and the Ploughman; La Dispute; Score; bobrauschenbergamerica; Room; War of the Worlds; Cabin Pressure; Alice’s Adventures; Culture of Desire; Bob; Going, Going, Gone; Small Lives/Big Dreams; The Medium; Hay Fever; Private Lives; Miss Julie; and Orestes. Opera credits include Tristan and Isolde, Croatian National Theatre; Macbeth, Glimmerglass Festival; Norma, Washington National Opera; I Capuleti e i Montecchi and Carmen, Glimmerglass Festival; Seven Deadly Sins, New York City Opera; and three operas by Deborah Drattell: Nicholas and Alexandra, Los Angeles Opera; Marina: A Captive Spirit, American Opera Projects; and Lilith, New York City Opera.

“Part of BLO’s mission is to offer audiences unique opera experiences that are seldom found elsewhere.”

– Anne Bogart

In his gorgeous recent book The Impossible Art: Adventures in Opera, composer Matthew Aucoin details the many impossibilities inherent in the opera experience. From its inception, he writes, opera undertook the daunting task of recreating Greek drama, a form that no one alive at the time had ever heard or experienced. He goes on to elaborate opera’s balancing act throughout history, for performers and spectators alike. Perhaps due to its unique position at the intersection of musical composition, theatrical performance, poetic expression, and visual artistry — not to mention its ability to interweave political, personal, and spiritual themes — opera tends to convey multiple messages simultaneously. This can be both demanding and rewarding for audiences. Other challenges include cultural and language barriers, a reputation for elitism, and the cost of attendance. But what shines through in Aucoin’s book is his profound passion for the art form and his optimism about its present and future.

And this is what is required: optimism and the willingness to embrace the great obstacles that the opera enterprise sets before us. And with great gusto. Obstacles are what define a person and even an organization. It is the impossibilities that catch fire and expand the definitions of what it means to be human.

I recently joined Boston Lyric Opera as their Artistic Associate. I agreed to become part of the company because I have been consistently astonished and inspired by their courage, tenacity, and audacity under nearly insurmountable conditions. Their ambitions and the ways they achieve their objectives are remarkably daring and often highly successful. As Artistic Associate, I am actively involved in the process of shepherding each season’s operas to BLO’s stages.

Before becoming the Artistic Associate, I stage-directed two BLO productions: an adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale by composer Poul Ruders, and Béla Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle intertwined with Alma Mahler’s Four Songs. I am currently in pre-production to direct this season’s Carousel by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein. The complications involved in bringing The Handmaid’s Tale into being were monumental. We transported a gigantic cast, design, and audience to Harvard’s enormous Lavietes Pavilion, a space originally envisioned by Margaret Atwood as the Red Center, where, in her fiction, a fascist theocracy

trained battalions of handmaids. For Bluebeard’s Castle | Four Songs, we constructed an immersive experience for audiences within the massive Flynn Cruiseport in South Boston’s Seaport District. For Carousel, we are bringing a colossal emblem of American musical theatre to the very space of its first performance in 1945: the Colonial Theatre.

Mitridate, also a remarkable and perhaps nearly impossible choice for BLO, was originally commissioned by Milan’s Teatro Regio Ducale in 1770. It is a serious opera written by a then-callow 14-year-old composer named Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Based upon a little-known Racine tragedy, the work is astonishingly advanced for such a young boy who had inherited the convention-heavy 18th-century style and practices of composition. The score advances the action in vast swathes of recitative interspersed with arias of vertiginous difficulty that equate emotional crisis with vocal athletics. The intense feelings of love, jealousy, and betrayal experienced by the opera’s characters are expressed in frenetic energy and dazzling high notes. This is a young composer’s extraordinary but uneven achievement that hints at the genius to come. An older, wiser Mozart later wrote arias that were more subtly difficult, and fewer of them per opera. Despite its initial run of 21 performances, for years afterward, Mitridate was considered unsingable. For all these reasons, it is an opera that hardly ever sees the light of day.

Part of BLO’s mission is to offer audiences unique opera experiences that are seldom found elsewhere. The world-renowned tenor Lawrence Brownlee, who performs Mitridate in this production, initially suggested that BLO produce this infrequently done opera. While occasionally staged in Europe, Mitridate is rarely performed in the United States. BLO decided to present this work to provide Boston audiences with a high-caliber experience of a largely unfamiliar Mozart opera, chosen for its exquisite music and intense emotional depth.

At the opera’s outset, family patriarch Mitridate — a combustible combination of weakness, vanity and cruelty — is presumed dead. The plot revolves around the intense rivalry between Mitridate’s two doppelganger-ish sons, Sifare and Farnace. The brothers are involved in a bitter feud over Aspasia, their father’s intended bride, who has captured both of their hearts. Aspasia is in love with the noble Sifare and

rejects the amorous advances of the devious, indolent Farnace. Suddenly, Mitridate reappears — not dead — suspicious of the motives of his sons and bent on vengeance for their duplicity. Much anguish ensues and the generational struggle plays out in emotional, political, and personal dimensions. The opera resonates like life, a constant battle between old and new.

What I love most about creating and experiencing opera is its inherent impossibility and extravagance, its extreme nature and disregard for realism. Opera plunges audiences directly into the emotions of people on the brink, emotions that are intricately woven together with magnificent, complex layers of exquisite music. Opera provides a shared, cross-cultural experience that is often exhilarating, blending artistry and athleticism, virtuosity and strength, as well as the grand and the personal. And surprisingly, during the most tragic and bloody moments, the singers as well as the audience seem to enjoy themselves immensely. For these reasons and more, I feel that opera may be the world’s greatest art form.

At the beginning of any process, the obstacles around realizing a production generally feel insurmountable. A tremendous amount of effort, planning, fundraising, imagination, and preparation must be invested in an art form that, in the end, depends upon the delicate vibrations of a singer’s vocal cords. A great deal of care, expense, and time goes into respecting the rules and procedures of the unions that protect our orchestras, singers, designers, and other creative personnel during hiring and production periods. The nature of opera-going itself provides plenty of obstacles as well, including its sometimes off-putting rituals and its inherent extremities of passion and feeling. Then there is the massive presence of the orchestra over which the human voice must soar. All of this feels epic and improbable. And yet, an ease and lightness must rise above all this effort. And this lightness is nothing less than ecstatic beauty.

Opera is an art form that demands constant reimagining and resurrection. We directors are meant to bring a fresh point of view to what is often called a “warhorse,” or a well-known canonical opera. But what happens when the piece is performed in concert, without a director and design team insisting upon one context or point of view? To experience an opera as grand and iconic as Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida without the accompaniment of visual pageantry offers us the chance to reassess the merits of this cherished opera, one that bears the weight of its own complex legacy.

Aida exemplifies the grandiose 19th-century operatic tradition, characterized by lavish spectacle and dramatic intensity. Audiences traditionally expect large-scale grand display, powerful music, military might, religious rituals, a love-triangle, an Egyptian setting, exotic costumes, live horses and camels, perhaps an elephant or two, strong vocal performances, a large chorus, and a tragic ending with the entombed lovers.

However, we live in a cultural and political moment in which we are reconsidering our basic tenets and assumptions. Arts institutions are seriously reexamining their mission and asking how to best serve, intersect with, and grow their audiences. They are asking basic questions. Who are we making art for? What should the art be about and for whom? How can we excavate new and useful meanings from our inherited past? What new significance can contemporary viewers find in a work that feels overly ornate or melodramatic? Viewed through the prism of contemporary cultural awareness, Aida’s depiction of ancient civilizations can strike a discordant note.

Staging Aida in its traditional form risks creating a time capsule of outdated theatrical conventions rather than a living, breathing work of art. The opera’s trademark of extravagance now feels out of step with current sensibilities, especially in the wake of the pandemic. The portrayal of ancient Egypt and Ethiopia, created through a 19th century European lens, can feel stereotypical, inaccurate, reductive, and misrepresentative to today’s discerning viewers who are increasingly cognizant of cultural nuances and authenticity. The opera’s inherent insensitivities have historically included the use of blackface and erroneous Orientalist portrayals of ancient Egypt. The grand scale can overwhelm the more personal, intimate moments and might appear sentimental to a modern audience.

And yet, the music soars. The full orchestra, the eight principals, the expanded chorus, and the on- and off-stage brass instruments all conspire to form a massive musical force that creates a powerful and spectacular sound world and a visceral experience. The singers climb a proverbial Mount Everest to deliver resonant performances to attentive audiences. Aida without the visual grandeur offers each audience member the opportunity to listen deeply to the music, let go of preconceived ideas, and apply their heightened attention and imagination, bringing an inquisitive attitude to the unfolding drama. We can receive the direct impact of Verdi’s vision through the intensity of the music and the sung words. Perhaps, for now, performing the music is enough.

Michael Billington, a distinguished British author and arts critic, is renowned for his vast knowledge of the stage and for his incisive observations about all kinds of performance. In 2019, after a long and illustrious career, Billington stepped down from his role as the lead critic for the prestigious UK newspaper The Guardian. During the COVID-19 pandemic, he graciously accepted my invitation to participate in a Zoom discussion with graduate students in directing, playwriting, and dramaturgy at Columbia University. During our conversation, I asked him about his post-retirement theatergoing experiences, and Billington offered an intriguing perspective. Rather than feeling more relaxed when attending productions without the obligation to write a review, he felt that his former role as a critic had actually enhanced his engagement with performances. He explained that as a professional reviewer, his senses were more finely tuned, allowing him to be more attentive and responsive to every nuance of a production. In essence, Billington felt that his critical faculties made him a more perceptive and engaged audience member.

A concert performance of Verdi’s Aida invites us to engage deeply, bringing our most attentive and discerning selves into play. Such experiences encourage us not simply to passively consume, but to listen actively and imagine collectively. The imagination is engaged to envision the story, the characters, and the world. This can lead to a more personal and intimate experience of the opera.

Attention and imagination are powerful cognitive tools uniquely bestowed upon us humans. The imagination, much like a muscle, requires regular exercise to maintain its strength and agility. Without consistent use, our imaginative abilities can atro-

phy, much as physical muscles weaken without activity. This analogy extends to our capacity for attention as well. When attention and imagination converge, they produce meaning and insight. However, in the modern world, the imagination lies increasingly dormant and underutilized. Over recent decades, corporate interests and the entertainment industry have gradually filled in the spaces once reserved for independent thought and creativity. The constant bombardment of advertisements, social media, film, and television present us with pre-packaged emotions and ideas, encouraging us to think in absolutes. This trend towards rigid thinking can lead to a sort of mental ossification, limiting our cognitive flexibility and — by extension — our freedom.

Imagination allows us to navigate through space, envision our journey on conceptual maps and explore various routes or possibilities. It plays a crucial role in forming new ideas based upon external stimuli. We can creatively integrate past experiences, learning, and information. Attention is the concentration of energy that “makes reality” wherever that focus is directed. What we pay attention to shapes our perception of reality. The creative process involves both imagination and attention bringing ideas into tangible forms. This combination enables us to bridge what is present with what lies below the surface. We use imagination to gain new knowledge, and then use that knowledge to imagine new possibilities. These fundamentally human tools allow us not only to understand our current reality, but also to conceive of new ones. We do this by exercising our capacity to continuously create new meanings.

Experiences that demand our active participation, like listening to Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida, can serve as potent exercises for both attention and imagination. When received with sufficient attention and imagination, opera can be one of the most exciting art forms imaginable. Start by paying attention.

To encounter an opera like Aida requires an act of resurrection. Perhaps this is true for all kinds of creation. The myth of Orpheus and Eurydice is the ultimate expression of this idea of resurrection and even failure. Orpheus descends into the world of the dead to resurrect his love. Ultimately, the journey is a failure. But what a spectacular attempt to storm the citadel. We attempt to rethink the past through the lens of the present. We can try.

“In time of the crises of the spirit, we are aware of all our need, our need for each other and our need for ourselves.” – Muriel Rukeyser

Erich Korngold’s Die tote Stadt (“The Dead City”) is based upon an 1892 novel by Georges Rodenbach entitled Bruges-la-Morte. It tells a haunting story of grief, obsession, and the struggle to move on after a loss. When the opera premiered in 1920, Korngold was only 23 years old, but the theme of overcoming the loss of a loved one resonated with audiences of the 1920s, who had just come through the trauma and losses of World War I.

I wonder what resonances audiences will experience now, in 2025? Will the radical shifts in our own current political, economic, and cultural environment, coupled with the specter of ongoing global conflicts — the lens through which we are now peering — affect the way that we experience the opera? Will its themes of grief, obsession, and the struggle to move forward after loss feel familiar and relevant to us now? Die tote Stadt also presents a complex interplay of gender dynamics that goes beyond simplistic stereotypes, reflecting the complexities of early 20th-century Viennese society, challenging conventional gender roles and expectations. I wonder how the opera’s exploration of the tensions between societal expectations and individual desires will speak to our own ongoing discussions about gender fluidity, identity, and the deconstruction of traditional gender norms.

During the three weeks prior to the presentation of Korngold’s Die tote Stadt, BSO will have presented all of Ludwig van Beethoven’s symphonies consecutively. The reasoning for this programing, and for including Die tote Stadt in the line-up, is to illuminate Beethoven as the source of Romanticism, and Korngold’s opera as a memorializing of its demise: bookends of what historians call the “Long Nineteenth Century” in music.

“The Long Nineteenth Century” stretched from 1789 to 1914, essentially from the beginning of the French Revolution until the outbreak of World War I. This extended timeframe is used by musicologists and historians to better capture the musical developments and transitions that occurred during that era. The notion of the Long Nineteenth Century allows us to grasp the progressions of ideas and

societal changes during this extended period, encompassing major shifts in musical styles, composition techniques, and performance practices that characterize what is often called the Romantic Era.

In 2025, amid seismic political shifts, wars, social transformation, and technological revolutions, creative expression has become indispensable to navigating our turbulent world. In moments like these, art transcends mere aesthetics, serving as a vital instrument of social cohesion and a bridge across societal divides. When successful, art translates complex ideas into relatable forms, helping us to process change and imagine new possibilities for our shared future. However, the arts and education sectors are currently facing unprecedented challenges with diminished resources and funding cuts exacerbated by the lingering effects of the Covid pandemic. Despite these obstacles, the need for communal artistic experiences has never been more crucial. Gathering in real time, in shared spaces, to undergo collective experiences has become both a challenge and a necessity. As we confront this new reality, joining forces with others, both personally and institutionally, to create and share artistic experiences, is not only an act of cultural preservation, but also a powerful means of societal recovery and renewal.

I am encouraged and inspired by the collaborative spirit and the cooperation between the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) and Boston Lyric Opera (BLO). Through their groundbreaking collaboration, exemplified by this joint presentation of Korngold’s Die tote Stadt at Symphony Hall, the BSO and BLO are pioneering a transformative era in Boston’s arts landscape. By joining forces, they are setting a powerful example of how cultural institutions can thrive through cooperation rather than competition. This collaborative model strengthens their individual positions and creates new possibilities for artistic expression and audience engagement.

Fueled by mutual respect and admiration for one another, the strategic alliance between the BSO and BLO exemplifies a new paradigm for cultural institutions. Moving beyond mere survival, this collaboration charts a course for mutual growth and deeper community engagement. By embracing shared resources and creative synergies, they are not only strengthening their own positions but also enriching the city’s artistic ecosystem, offering a blueprint for cultural resilience and innovation in challenging times.

By leveraging their combined strengths, sharing resources, and developing creative solutions, the BSO and BLO aim to cultivate new programs, engage hard-to-reach audiences, and strengthen advocacy for the arts. This partnership embodies a spirit of inclusion that resonates with former President Barack Obama’s vision of modern pluralism, fostering mutual learning and growth while expanding networks and increasing artists’ visibility. Ultimately, this collaboration demonstrates how cultural institutions can thrive through cooperation, creating new possibilities for artistic expression and audience engagement, leading to a more robust and resilient arts community in Boston.

As we navigate these tumultuous times, I recognize the dual nature of our collective challenge: we must remain vigilant as individuals and as a society. Personally, I am acutely aware that, both as an individual and as part of a community, my role is to maintain a state of conscious awareness while adjusting to the swiftly moving social, political, and cultural shifts, and all without sacrificing my core humanity.

Social systems, societies, and organizations are made of selves. These selves collaborate in acts of the imagination that emanate from a collective conscience based upon this relational constellation of individuals. What is required from all of us is a deep and imaginative sensitivity to other selves, that allows us to envision what it is like to walk in somebody else’s shoes. This balancing act requires from all of us a delicate blend of resilience and empathy, allowing us to evolve with our changing world while holding fast to the values that define our shared human experience. Our empathy for others is the hallmark of our humanity.

My own development as a theatre and opera director has been shaped significantly by collaboration with others. About fifteen years ago, I made the decision to transition from solely directing plays with my theater ensemble, SITI Company, to us embarking together upon a series of large-scale collaborative projects with exceptional artists from different disciplines. Thus began a sequence of creative adventures, first with the Martha Graham Dance Company, then with Bill T. Jones and the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, then with the visual artist Ann Hamilton, then with the composer Julia Wolfe and her ensemble Bang on a Can, and then with Elizabeth Streb and the STREB Extreme Action company. In each

collaborative project, all the artists involved were pushed beyond their comfort zones, blurring the lines between disciplines. For example, actors found themselves navigating intricate choreography, while dancers grappled with delivering nuanced dialogue. The result was a dynamic fusion of talents, where the distinction between actor and dancer became beautifully ambiguous, fostering a rich, multidimensional performance landscape that defied traditional categorization. All these collaborations were challenging and at times stressful, but I am deeply grateful for the engagement and even for the obstacles that they presented. In each process, SITI Company and I were ultimately altered irrevocably, artistically, administratively, and personally, by the chemistry of having joined forces. In each case, it was impossible to be sure about the result, about what we might achieve together, in concert. In the process, I learned that we cannot predict the results until the actual chemistry of engagement happens. It is impossible to completely control where such collaborations will lead, but the commitment to join forces is the conduit to innovation and change.

In art, we seek to communicate, with an emphasis on the root communis which means “in public, common, shared by all.” Through art, we strive to illuminate the threads that bind us together as a society, revealing our common experiences and shared humanity. Art is an instrument of cohesion and translation between individuals as well as between organizations. By weaving together diverse perspectives and individual stories, we create a tapestry that reflects our collective identity. It serves as a universal language, bridging gaps between people from all walks of life and facilitating understanding across cultural and organizational boundaries.

The rapid and often troubling changes in the world present us with challenges and obstacles that necessitate a collective effort to broaden our embrace, break down silos, and rediscover common purpose by drawing upon our diverse talents. We can help one another to stay awake. As a society we are more polarized than ever before, and staying awake feels extremely challenging. The stakes are high, and everyone appears to be far apart, feeling either angry or scared about what is happening, finding refuge in isolation. I believe that shared creative acts between both individuals and institutions are the solution to our current situation. We can stay awake together. We must stay awake together. We cannot afford to be passive, waiting until conditions improve.

“We have thrown an entire planet out of balance, and now we are suffering the consequences — weather patterns so severe we have no idea how to combat them, and the resulting fires, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, more severe than anything we’ve known before.” – Patti Davis

Artists have long been recognized as cultural barometers uniquely positioned to respond to and interpret the realities of their time, no matter how challenging. Their role extends beyond mere representation or creating aesthetically pleasing works; they are tasked with creating spaces for reflection and associative thinking that allow society to examine itself critically. By providing a mirror through which we can examine ourselves, artists play a crucial role in shaping cultural discourse, challenging societal norms, and inspiring change. In doing so, they help us to navigate the complexities of our world and envision new possibilities for a shared future.

It might be useful to consider the creation of art as occurring in three complexly interconnected phases: raw encounter, cognitive processing, and artistic reflection. These stages engage our senses, intellect, and emotions in distinct yet intertwined ways, offering unique perspectives on how we, as observers and participants, might perceive and process life events.

The first stage is the immediate experience: a raw encounter with reality. This is the most primal level of perception where we meet life directly without filters, deep thought, or analysis. “My house is burning, and I must escape.” We simply react to what is happening. This is a deeply personal phase. In time, and with adjustment, eventually one might move to some semblance of “normality.” In the second stage, we step back and attempt to make sense of what happened. This is the cognitive processing of the experience and involves rationalizing the event. In other words, we shift out of a feeling-space into more of a thinking-space in an attempt to understand the broader context and implications of our experience: “Climate change is wreaking havoc on the planet.” The distance between the first and second stages, between the experience and the intellectualization of the experience, often feels insurmountable. The emotional intensity of lived experiences often clouds our

ability to objectively analyze their significance. The proximity to our own trauma can create a fog through which deeper understanding struggles to penetrate. Time and distance may be necessary to unravel the complex threads of meaning woven into life-altering events.

The third stage, artistic reflection, provides a space for processing experiences through artistic engagement. Art can offer a stillness within which we can explore our experiences in ways that neither raw encounter nor pure intellectualization will allow. It can provide a bridge between the visceral and the cognitive, allowing us to investigate our emotions and make unexpected connections, leading to a more holistic understanding of our experiences. Yet this stage is perhaps the most challenging. German philosopher Theodor Adorno struggled with the idea of artists making art after the Holocaust, going so far as to say that to do so would be “barbaric.” Later he insisted that in saying so, he was not trying to silence poets or artists; instead, he was grappling with the ethical and aesthetic challenges of creating art in the aftermath of such immense human suffering. To produce cultural artifacts without acknowledging or responding to the horrors of what happened risked perpetuating the very barbarism that made it possible, suggesting that traditional forms of representation may be inadequate for capturing the magnitude of certain events.

Art can create a safe space with boundaries where thoughts and feelings that are difficult to articulate verbally can be unpacked, considered, and reconsidered. The artistic process acts as a mediator, allowing us to engage with our innermost selves in a tangible, yet metaphorical way. Even painful experiences or difficult issues can be confronted at a safe distance. The artistic medium becomes a bridge between the real world and the intangible world of emotions. But how to begin? Generally, artists start by clearing mental and physical spaces, akin to a farmer preparing a field for planting. This act of clearing serves as a crucial first step, creating a blank canvas ripe with potential. Next, ideas are planted, often with an eye toward finding the universal in the specific. Through dedicated attention, effort, and thoughtful cultivation, these ideas gradually take root and flourish. Simple concepts transform into rich, multilayered metaphors. Recurring themes emerge, forming expressive tropes that give depth to the work. Ultimately, metaphor and allegory can anchor abstract concepts in reality and make monumental subjects more relatable and

perhaps less threatening. In theater, familiar scenarios or relatable characters can serve as vehicles for the audience to connect emotionally with complex social, political, philosophical, or scientific issues such as global warming. For example, portraying Earth as a patient on life support can convey the urgency of climate change. This approach transforms abstract macro concerns into personal, intimate experiences, making the risks and implications of environmental challenges more immediate and relevant.

The complex relationship between art and climate change demands a nuanced examination of artistic practice in our current environmental context. While art alone may not have the power to halt climate change, its role in addressing this global crisis remains significant yet challenging. Perhaps what is needed is a radical rethinking of artistic practice considering the world we live in now.

Here are a few examples of artists who are working to address powerful global issues:

• In a recent exhibition, Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei displayed large iron structures — cast from fragments of the giant roots of Brazil’s endangered pequi vinagreiro tree — to illustrate the destruction of the Amazon rainforest and the decimation of Earth’s lungs.

• Composer Ludovico Einaudi performed “Elegy for the Arctic” on a floating platform in the Arctic Ocean, drawing attention to the urgency of melting of polar ice.

• The Walkabout Theater Company created a participatory work in 2012 which invited people worldwide to write letters to disappearing ice formations, engaging them with the reality of global ice loss.

• Visual artist Anselm Kiefer’s focus on transformation and decay in his artworks parallels the changes occurring in our environment due to global warming. His artworks frequently feature barren landscapes, referencing deforestation and habitat destruction.

• Sean Yoro (HULA) creates murals on melting icebergs or underwater on coral reefs, highlighting the fragility of these ecosystems.

• Susie Ibara and Michele Koppes’s “Water Rhythms” installation allowed people to listen to the sounds of melting glaciers, providing a sensory connection to climate change.

• The Australian physical theater company Legs on the Wall created a piece entitled “Thaw” featuring a 2.5-ton block of melting ice at the University of East London’s Docklands Campus. This performance, inspired by Australia’s 2019/20 bushfires, aimed to bring Londoners face-to-face with the urgent need for global climate action.

• Conceptual artist Gavin Turk, nicknamed “the laureate of waste,” reimagines the purpose of disposable objects, using throwaway items to comment on our relationship with waste and worth.

• In 2013, composer David Crawford translated climate data into a piece for cello and piano entitled “A Song of Our Warming Planet,” with each note representing a specific year’s global temperature.

• A 2020 street exhibition in Madrid entitled “We Are Frying!” by Luzinterruptus used potato chips to represent autumn leaves burned to a crisp by global warming, reflecting on how climate change affects foliage.

The list goes on. And I am grateful that it does.

How can aesthetically pleasing works coexist with the often-devastating consequences of environmental degradation? Perhaps traditional forms of artistic expression are inadequate to capture or describe the reality that is happening. This tension challenges artists to reconsider the purpose and presentation of beauty in their work. Ultimately, art’s role in addressing climate change is not just about representation, but about fostering a deeper, more holistic understanding of our relationship with and impact on the environment and each other.

Staging a new or relatively unknown theatrical work differs significantly from reviving a beloved classic that has achieved chestnut status. When Bradley Vernatter, the General Director & CEO of Boston Lyric Opera, approached me about directing Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s Carousel for the company, I responded with immediate and wholehearted enthusiasm. Chestnut! The appeal of Carousel extends far beyond its powerful music and compelling narrative. It is a production that resonates deeply with audiences, evoking personal connections and cherished memories. Upon mentioning my involvement with the show, I am invariably met with a flood of personal anecdotes and spontaneous musical recollections. Some people share stories of their own high school performances, while others recount transformative experiences of watching the show at pivotal moments in their lives. The music of Carousel, particularly “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” has transcended its theatrical origins to become a cultural phenomenon. The song has been adopted by several football clubs, most notably Liverpool, where the tradition of singing the song before every home game has become an iconic part of football culture. In some areas of the United Kingdom and Europe the song became the anthem of support for medical staff, first responders, and those in quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic. This universal response underscores Carousel’s enduring impact and its status as a true theatrical chestnut. The musical has woven itself into the fabric of cultural memory, with its songs and themes that continue to evoke strong emotional responses decades after its 1945 Broadway premiere.

A chestnut in theater is more than just a play; it is a cultural artifact steeped in its own rich history. When staging such a well-known work, directors and actors face a unique set of challenges that go beyond the typical demands of production. Firstly, the audience does not arrive as a blank slate. They bring with them a tapestry of memories, expectations, and preconceptions woven from previous encounters with the work. These might be personal experiences, iconic interpretations they have seen, or simply the play’s reputation in popular culture. This collective memory creates an invisible but palpable presence in the theater, one that the production must acknowledge and engage with.

The word chestnut carries with it negative connotations such as hackneyed or overused, or a story that has been repeated so often that it has become stale, trite, or uninteresting. James Parker, a staff writer at the Atlantic Magazine, cited the example of the infamous poems of Robert Frost, including “The Road Not Taken,” or “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” These, he says, are not really poems anymore. Decades of mass exposure have done something to them, inverted their aura. He said that they are now more like “recipes, or in-flight safety announcements.” Moreover, chestnuts often come with specific moments or lines that have transcended the play itself to become cultural touchstones. Think of Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy — these words carry a weight far beyond their role in the play’s narrative. They have become part of our shared cultural language, referenced and parodied countless times across various media. To stage a production of Tennessee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire, which has over time become a chestnut, where do you put Marlon Brando’s portrayal of Stanley? What do you do with the expectations that audiences bring with them about how Stanley should look and sound? Do you pretend that Marlon Brando never played Stanley?

In staging a chestnut, the creative team must walk a delicate tightrope. On one side is the pull of tradition — the desire to honor the work’s history and meet audience expectations. On the other is the drive for innovation — the need to breathe new life into the familiar and make it resonate with contemporary audiences. This tension between reverence and reinvention is at the heart of staging a chestnut.

With a chestnut, it is useful to consider the zeitgeist of the moment of a play’s premiere and compare it to that of the current moment. In 1945, the year of Carousel’s premiere, the United States was engaged in a massive war both in Europe and the Pacific. Young men were returning home with what we now might call PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder). The character Billy Bigelow may have been an example of such a young man — violent and lost and full of unexplored aggressions. Imagine how “You’ll Never Walk Alone” was received by audiences in 1945, many of whom were struggling, picking up the pieces of the war. Children were being raised in fatherless homes. A lot of these were encapsulated by the characters Julie and Louise. Rodgers and Hammerstein connected the source material of Liliom, the Hungarian play upon which the musical is based, and what

audiences required in 1945. Billy has serious issues, but the play’s ultimate messages of hope, breaking cycles of trauma, and working towards a promising future are still meaningful and potent.

How has Carousel evolved in meaning and interpretation over time as society changes? In 2025, connecting its themes to contemporary issues and audiences requires a nuanced approach that goes beyond simply recreating the original production. Perhaps the key question to ask is not “How do we recreate the original?” but rather, “Who needs to perform this play now and who needs to hear it?” This opens new possibilities for interpretation and relevance. When Carousel first premiered in 1945, it was groundbreaking for its sophisticated integration of music and drama. The musical tackled darker themes than previous musicals, exploring complex characters and relationships. However, over time, certain aspects of the story have become contentious, particularly its handling of domestic violence and abuse. The key is to balance respect for the original work with the need to address its problematic elements. By doing so, Carousel can continue to evolve, offering insights into human nature and societal issues that remain relevant 80 years after its premiere.

Our Carousel is happening in the same theater as its final out-of-town tryout in 1945. This leads to intriguing questions about the presence of the past and about how memories and patterns might be stored and transmitted across time and space. Do physical spaces like theaters hold memories of past performances? Do the ghosts of the performers who originally played those roles lurk nearby? Do buildings store memories? The scientist Rupert Sheldrake proposed that there is a collective memory inherent in nature, allowing similar patterns to influence subsequent ones from across time and space. He calls this phenomenon morphic resonance. His theory offers an intriguing perspective on the idea of “ghosts of past performances” in theater buildings. Morphic resonance suggests that the building itself might “remember” past performances, creating a resonant field that new productions and audiences unconsciously tap into. Sheldrake is a controversial figure in the scientific community, and his theories remain debated. But they do provoke a framework for speculation about how past performances might subtly influence current productions in each theater space, creating a unique atmosphere or energy.

In essence, directing a theatrical chestnut is not just about putting on a play. It is about entering into a dialogue with history, audience expectations, and the cultural significance that the work has accrued over time. It is a complex dance between the past and the present, between the familiar and the fresh. But by reframing chestnuts as valuable cultural artifacts rather than tired cliches, we open new possibilities for interpretation, connection, and relevance. I see them as repositories of collective memory and shared cultural experiences. This shift in perspective invites us to appreciate the depth and richness that comes with works that have stood the test of time.

Ultimately, my interest in Carousel is not simply to the answer to the question “who needs to perform this play now and who needs to hear it?” The aim is to tap into the power of the original without altering its content. We are not changing or eliminating any of the words or music. In our version of Carousel, a group of refugees arrive from a great distance to perform the play, seeking to gain access and acceptance. The show’s exploration of forgiveness and community aligns with the refugees’ quest for acceptance. As the performance unfolds, it is my hope that the original power and alchemy of Carousel takes hold. Through this process, two separate communities, that of the audience and that of the performers, may transform into one, united in the intrinsic power of the piece.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as audiences cautiously began returning to live theater, my colleague Leon Ingulsrud attended a production in New York City. When I later asked him about his experience, he expressed disappointment, shaking his head and remarking, “No one said hello to the audience.” His sentiment struck a chord with me, highlighting a missed opportunity for connection in a time when audiences craved acknowledgment and warmth after such a prolonged absence from communal experiences.

In today’s theater environment, I feel that there is a growing need for audiences to be more than passive observers — many want to feel like active participants, or even collaborators in or contributors to the theatrical experience. This goes beyond immersive theater, where the boundaries between performer and spectator are intentionally blurred, allowing interaction with the environment, actors, and narrative. Instead, it questions the very idea of the fourth wall, which feels increasingly less relevant in the current cultural moment.

Now, in the face of the escalating climate crisis, widespread displacement of populations, erratic and volatile markets, and the relentless flood of distressing news delivered through traditional media and social media platforms, many people today find themselves grappling with a profound sense of being overloaded and emotionally drained. This relentless exposure to global crises often leads to two common emotional responses: cycles of intense anxiety, where individuals feel consumed by fear and helplessness; or states of emotional numbness, where detachment becomes a coping mechanism to avoid being overwhelmed. These reactions reflect the psychological toll of living in an age of unprecedented challenges and information overload, where the sheer magnitude and quantity of the issues affecting us can make it arduous for individuals to process their emotions or take meaningful action. Theater can provide a unique alternative to these responses. It offers a space to be present with others — free from the isolating effects of digital distractions — to engage deeply with timeless stories that can resonate across generations, teaching us ways to live, what to value, and how to find courage to persevere in the face of adversity. These great narratives — whether drawn from history, mythology, or contemporary experiences — serve as mirrors for our own lives. By creating an

environment where people can be fully present with others and with themselves, theater becomes a sanctuary for emotional renewal, intellectual growth, and collective healing.

This brings us to BLO’s current production of Noah’s Flood (Noye’s Fludde). By being here, you become part of the historic trajectory of an ancient tale about a flood which, in this version, was resurrected by Benjamin Britten in the mid 1950s. Around the same time, T. S. Eliot — poet, essayist, playwright, and contemporary of Britten — became passionately interested in medieval mystery plays. He believed that modern drama should incorporate poetic forms and ritualistic elements to achieve a deeper resonance with audiences. He drew inspiration from medieval plays such as Everyman that emphasized themes of faith, conscience, and divine purpose. Eliot’s ideas had a notable influence on Britten and most likely encouraged him to explore these older biblical and iconic forms of storytelling, emphasizing their communal and ritualistic aspects, blending religious themes with artistic innovation. Britten based Noah’s Flood upon the Chester Mystery Play Noah’s Flood and the biblical story of Noah’s Ark, a timeless narrative of survival, renewal, and divine intervention. What makes the work distinctive is that it reflects Britten’s admiration for the dramatic simplicity and spiritual depth of medieval texts, combining this with his interest in community-oriented music-making and his desire to create works that were accessible to amateur performers, especially children. He specified that the opera should be staged in churches or large halls, not in a theater.

The idea of a “Great Flood” is a recurring theme in the mythologies of hundreds of cultures around the world, reflecting humanity’s shared experiences with natural disasters and their symbolic interpretations. While each culture’s flood narrative is unique, they often share common themes of divine wrath, survival, human resilience, and renewal. In the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, which predates the biblical flood narrative in Genesis, Utnapishtim is warned by the god Ea about a flood meant to punish humanity for its corruption and noise. He builds a seven-deck boat, saving his family, animals, and craftsmen, and releases birds to find dry land after six days of storms. Upon succeeding, Utnapishtim sacrifices to the gods and is granted immortality. In Hindu mythology, Manu is warned by Matsya, an avatar

of Vishnu, about a flood that will destroy all life. Guided by Matsya, Manu builds a boat, preserves seeds of life, and re-establishes creation after the waters recede, emphasizing divine intervention and humanity’s role in renewal. Australian Aboriginal cultures also feature flood narratives tied to spiritual beliefs and nature. One story describes Goonyah angering a Great Spirit by eating forbidden fish, causing a deluge that overwhelms him. Another tale involves lizards summoning destructive rains through rituals. These myths reflect the sacred relationship of the First Peoples of Australia with weather patterns and their environment.

The Bible’s Book of Genesis tells of a time when humanity has become corrupt and wicked, prompting God to cleanse the Earth with a great flood. However, Noah, a righteous man, finds favor with God. He is instructed to build an ark — a massive wooden vessel — and to bring aboard his family and pairs of every animal species to preserve and rebuild life. For forty days and nights, rain falls, and floodwaters cover the earth, wiping out all living creatures outside the ark. After the rain has stopped, the waters gradually recede. Noah sends out a raven and then a dove to find dry land; when the dove returns with an olive leaf, Noah knows that the Earth is renewing. Once the flood has ended, God makes a covenant with Noah, promising to never again destroy the Earth with a flood and setting a rainbow in the sky as a sign of this promise.

This ancient story resonates with our own contemporary challenges that include climate change, social and political corruption, and global crises that threaten life as we know it. The ark represents salvation and renewal in the midst of destruction. Ultimately, the story is about the preservation of life in dark times. Does this sound familiar?

Imagine yourself in Noah’s position today — faced with the monumental task of deciding what to bring aboard an ark to survive a catastrophic flood. This scenario prompts profound questions about our values, priorities, and relationship with the natural world. What would be essential to preserve? Which species or resources hold the greatest importance, and how might these decisions shape the future for generations to come? Who would be saved and who or what would be left behind? The choices would not only be difficult — but also, they would reveal much about our collective values and vision for the future.

The concept of the flood — whether literal or metaphorical — resonates deeply in today’s world. On one hand, it serves as a stark warning about the consequences of environmental degradation, with escalating sea levels caused by rising global temperatures reminding us of the urgent need to address climate change. On the other hand, the flood can also symbolize the overwhelming inundation of information in the digital age. This “flood of information” raises critical questions: How do we navigate these virtual deluges? What do we preserve, and what do we discard?

In the realm of theater and storytelling, perhaps what we should discard are the distractions that cloud our lives — those fleeting concerns that prevent us from focusing on deeper truths. What we might choose to save are the stories we pass down through generations, narratives imbued with wisdom meant to guide us toward richer, more meaningful lives. These inherited tales carry timeless lessons that can help humanity confront contemporary challenges with resilience and purpose.

By revisiting these narratives, we can perhaps find elements to create a foundation for more inclusive and humane solutions to global crises rather than succumbing to despair and resignation. These stories remind us that humanity has always faced adversity, and that survival often depends on collective action, faith, and responsibility. Stories can inspire us to act before reaching a point of no return, urging us to preserve life and envision a better world even — perhaps especially — in the aftermath of a disaster.

Perhaps today’s metaphorical ark is not a physical vessel, but rather a framework for addressing global challenges — a way to safeguard what is essential while charting a course toward sustainability and renewal. This ark could embody resilience, cooperation, and creativity, enabling humanity to weather both literal floods and the virtual torrents of information that threaten to overwhelm us. By drawing from past narratives while reading the signs of the times, we can build a future rooted in hope and responsibility, ensuring that life thrives even after the storm has passed.

Thank you for supporting Boston Lyric Opera’s 2024/25 Season! Your generosity ensures that we can continue shaping the future of opera in Boston.