ROADWORK

125 YEARS OF E. D. ETNYRE & COMPANY

Bill

Gordon

Melissa

Author

Welcome to the 127-year-old story of Etnyre International! We wouldn’t be here today without all the people who paved the way—members of the Etnyre family starting with my great-grandfather and grandmother, E. D. and Harriet Etnyre, the company members from years past, and those present. To you and to our communities, customers, dealers, and suppliers, we say thank you.

Little did anyone know in the early days we would become one of only about 1,000 American companies to still be running at 100 years. And what a company! As we move ahead, let care, humility, trust, respect, and integrity guide us in improving the lives of people throughout the world.

William S. Etnyre, PhD. Chair of the Board

I have had the honor of guiding this organization through seven years of pivotal transformations. We have embraced significant change, blending the wisdom of our storied past with bold steps into the future. And what excites me is where we are headed.

Etnyre’s foundation was forged through the family’s commitment to its stakeholders—members, customers, suppliers, and the communities. This book captures that story of decades of hard work and creativity.

Our future is one of purpose-driven progress, focusing on improving lives by serving the world’s infrastructure needs. Our roadmap will harness state-of-the-art technologies, global partnerships, and focus on sustainability. Moving forward, we will continue to challenge the possibilities with an eye on making the world a better place.

Ganesh Iyer, PhD. President and CEO

As we pause to recognize and reflect on Etnyre’s anniversary, I am flooded with gratitude.

n Gratitude for all the members past and present.

n Gratitude for our partners, suppliers, and our communities.

n Gratitude for our customers, many of whom are friends.

n Gratitude for the prior Etnyre family members who dedicated their lives to this business.

We know the future will be neither easy nor certain but there remains a desire and dedication to keep going and for that I am also grateful. My heart-felt Thank You to all who have been part of this journey.

Don Etnyre Member of the Board

Second, Etnyre is about family. This means the actual family, of course: the generations of Etnyres who founded and built the company, who worked there and owned shares, who guided its board and charitable endeavors— and still do. But it also means the hundreds of non-family members who have worked with Etnyre and been treated as extended family through employment practices, benefits, loyalty, friendships, and day-to-day camaraderie. Indeed, the company doesn’t call them employees but members.

It is remarkable that any business lasts more than a century and a quarter. It is even more remarkable that it has done so while remaining a private company owned by the same family. These accomplishments are worth honoring and looking back upon.

This farm raised well-hydrated hogs thanks to an efficient, new watering system invented in the late 1800s by

CHAPTER ONE

In the atrium of E. D. Etnyre & Company’s offices in Oregon, Illinois, a display depicts the early history of the business. Most of the items show what you would expect from a company that manufactures and sells road building and preservation equipment: a horse-drawn tanker, a horse-drawn oiler, a 1922 truck that cleaned streets by flushing them with water. But one display looks out of place. In the midst of the carefully restored vintage vehicles, three dummy hogs that seem to be smiling stand facing a watering trough.

This agricultural still life isn’t the outlier it seems. The hogs and the trough are a cherished part of the Etnyre story. Figuring out how to water livestock more efficiently provided the inspiration that led to the founding of the company that has now done business for more than 125 years.

The man who devised the watering system and later started the company was Edward D. Etnyre. He was a fourth-generation descendant of German immigrants who came to America from the hamlet then known as Euteneuen, on the

Sieg River in the Rhineland. His surname, which appears in different spellings over the years, is thought to be drawn from ancient words that mean, appropriately, “new road.”

In pursuit of that new road, Edward’s great-great-grandfather, Johannes, who spelled his surname Eideneier, boarded the ship Queen of Denmark in 1751 and sailed from Rotterdam to Philadelphia, the receiving port for most early German settlers in the American colonies. He gravitated to western Maryland, where he farmed and began a family. Two generations later, his grandson, John Etnyre, a War of 1812 veteran who used a simplified spelling of the name, migrated by steamship and covered wagon to the Northwest Territory of northern Illinois.

He landed in a new town called Oregon, on the Rock River, a beautiful setting with rolling hills and outcrops that break the level plains running a hundred miles west from Chicago. The area had once been the home of indigenous tribes—the Sauk, Potawatomi, and Winnebago—but they

Oregon’s first mayor, James V. Gale, noted in his diary that Daniel Etnyre bought out the other heirs. “He has been a successful farmer and good citizen. . . . He is a man of few words and much respected by his fellow townsmen.”

were rapidly displaced by new Americans seeking a better life, most of them from New England. In a sign of things to come, one of the pioneer settlers a few miles south in Grand Detour was a blacksmith named John Deere, who would become famous for devising a self-scouring plow that could break up the rich prairie soil.

John Etnyre paid $1,600 for a land claim outside Oregon but he wasn’t able to farm it. He died only a few months after arriving in 1839. Some years later, Oregon’s first mayor, James V. Gale, noted in his diary that Daniel Etnyre, one of John’s sons, bought out the other heirs. “He has been a successful farmer and good citizen. . . . He is a man of few words and much respected by his fellow townsmen.”

Daniel Etnyre was indeed a bedrock of the community. In addition to farming, he worked as a carpenter and opened the Rock River Furniture Company. He also founded the First National Bank of Oregon. Among the children he and his wife, Mary, had was Edward Daniel Etnyre, born in 1859.

Edward Daniel Etnyre—who went by his initials: E. D.—grew up working on the family’s 480-acre farm west of Oregon. By the time he reached young adulthood in the late 1870s, his parents were doing well enough to send him away to college at Northwestern University, where he became an accomplished athlete and helped

In the early days, “road oil” was applied directly to dirt roads to settle the dust— building a base for future road improvements.

organize its first baseball team. He was a pitcher of relatively small stature, hence his nickname: Bantam.

He didn’t stay in college long. “He was tired of it,” one of his sons, Robert “R. D.” Etnyre, remembered in a 1973 radio interview. “He wanted to go out West, so his father made arrangements, and he did go out West—riding the plains, buying cattle.”

E. D. had another motivation. His girlfriend in Illinois, Harriet M. Smith, had moved to northern California with her family. While Etnyre experienced the life of a cattleman, he rekindled their romance, and they were married in Sacramento in 1885. The Freeport Daily Bulletin back in Illinois ran a brief about the wedding, describing

Etnyre as “the son of a rich banker” (perhaps exaggerating) and saying that the couple would soon return “to occupy their home of comfort at the pretty little city on the Rock, where their courting began.”

E. D. and Harriet started a family, and he farmed for several years before his restless spirit again altered his fate. Etnyre liked to tinker with things. Sometime during the 1890s, he wondered whether there was a better way to bring water to livestock than getting up early day after day to laboriously fill the troughs by hand. He started working with Chet Nash, an acquaintance and Civil War veteran, who had a mechanical shop in Oregon. They came up with an automatic watering system that operated with

In the fledgling years of the horseless carriage, hundreds of wagon-builders and bicycle shops across the Upper Midwest tried their hand at the new technology. As E. D. Etnyre was already making road equipment, it stood to reason that he would tackle manufacturing automobiles as well. ◆ Etnyre built three “gas buggies,” as he called them, in the early years of the twentieth century. The first models had hard rubber tires and fourteen-horsepower engines that were air-cooled and featured a two-seat bench made of horsehair and leather over springs. He sold one to a local farmer and kept one for his family, which his sons drove hard around Oregon, wrecking it now and then. He sold the third model to John Prasuhn, a sculptor who worked on the Black Hawk statue in Lowden State Park. ◆ More than half a century later, the Etnyre family bought that last buggy from a farm equipment dealer in Indiana and painstakingly restored it. The car

made several appearances in local parades and antique auto shows. Don Etnyre, a great-grandson of E. D.’s who worked at the company for decades, drove it several times.

“It was fun,” he says, “but it was overheating all the time.”

◆ Today the buggy is displayed in the company’s lobby alongside early road oilers and flushers—a picturesque tribute to the road not taken.

a siphon hose, valve, and float, not unlike a modern toilet. When a hog drank enough water, the float would lower, the valve would open, and water would flow from a larger tank into the trough until the float rose again and shut off the supply.

This was the eureka moment depicted by those dummy hogs in the atrium of

E. D. Etnyre & Company’s offices.

Word spread about the labor-saving device, and Etnyre was soon making and selling them to farmers in the area. The automatic waterers led to what modern companies would later call a product extension. Etnyre began building rolling water tanks to service the steam-driven threshers farmers then used to harvest their grain. The first tanks were wooden, but eventually they were made from steel. “THRESHERMEN,” said an 1896 Etnyre ad, “do not spend time with an inferior tank. Get the best tank made which is the ‘ideal.’ It costs no more than the cheaper kind.”

Before long, the tanks led to another product extension: horse-drawn sprinklers that sprayed water on dirt roads to keep down the dust.

“Wasn’t long before people began thinking about oil to settle the dust instead of water,” R. D. Etnyre explained in that 1973 radio interview. Oil did a better job of maintaining dirt roads because it didn’t evaporate like water. So, Etnyre rigged sprinklers to spray oil, and the business grew.

E. D. Etnyre & Company opened shop in 1898 in an old battery factory on the banks of the Rock River. A few years later, it moved to larger quarters at the intersection of Jefferson and Second Streets. In the 1900 census, Etnyre described his occupation as a maker of sprinklers. He was soon to make so much more.

The pre-dawn rush of water from an Etnyre flusher was one of the most familiar sights and sounds on municipal streets during the mid-twentieth century. The company still makes flushers for other uses, but most local governments have transitioned to the use of street-sweeping machinery.

He progressed to building more powerful roadsters that he must have thought would become the cornerstone of his company. Why else, in the 1910 census, would he have described his principal occupation as “president, automobile factory”?

continued from page 7

infrequently in the nearest town. As RFD was enacted during the early years of the twentieth century, the US Post Office Department joined the push for better roads so it could carry out its federally mandated mission.

Third, farmers across America began to demand better roads so they could deliver their crops to wider markets, giving them an alternative to shipping by rail, which could be expensive (as monopolies are wont to be). The farm-to-market road movement joined the cause.

The final factor was the most decisive: the coming of the automobile. The first commercial car in the United States, the Duryea, appeared in 1895 and ushered in a technological boom that saw scores of small independent companies making different versions of horseless carriages. After the turn of the century, Etnyre became one of them.

Sometime between 1903 and 1906, around the time Henry Ford was launching his Model A in Detroit, E. D. Etnyre made several “gas buggies” in Oregon. He progressed to building more powerful roadsters that he must have thought would become the cornerstone of his company. Why else, in the 1910 census, would he have described his principal occupation as “president, automobile factory”? He even had an impressivelooking illustration of that factory drawn up.

The same year he gave the census-taker that information, Etnyre took some friends

out for a drive in one of his prototypes, a touring car capable of going a mile a minute. The passenger compartment was a work-in-progress, so he installed ropes for the gentlemen to steady themselves with and instructed them to hold on tightly in case the car hit a rough spot in the road.

It did. When the car hit a bad patch, one of the back-seat passengers, who had stood up to speak with Etnyre in the front, was thrown from the vehicle to the ground. He suffered a broken hip and a gash over an eye. “This is the first really serious automobile accident that has come to any of our citizens,” the local newspaper reported. The accident probably played no part in Etnyre’s decision to exit automobile manufacturing. Scores of companies tried to make cars in those years and quickly faded as the industry consolidated. But that rough

spot in the road does seem significant in hindsight. Even as cars began to proliferate in the early 1900s, almost all roads in the United States remained dirt or gravel. American mobility was still at the mercy of mud and dust. For Etnyre, the future was not in making automobiles, but in building and maintaining the surfaces those automobiles would drive on.

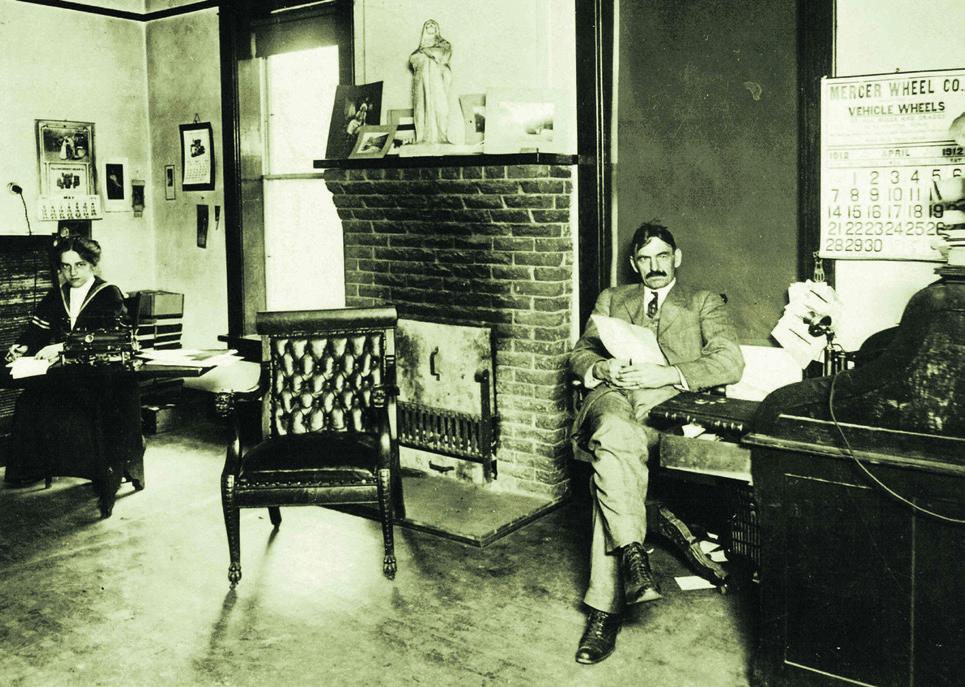

Oregon in the early twentieth century was becoming a hub of industry because of its location on the Rock River and on a main east-west rail line. The town of 2,000 boasted a flour mill, a furniture factory, an oatmeal mill, a piano factory, a grain elevator, a foundry—and the Etnyre works. During those years, Etnyre improved

and modernized its early sprinklers, adapting them for water and oil. Initially the pump was driven by a chain and sprocket attached to the axle of a wagon. Later it was powered by a gas engine that could be hitched to or mounted on a motorized vehicle.

The company also developed a street flusher that could clear roads of dirt, trash, and horse manure, shooting water out at fifty pounds per square inch of pressure.

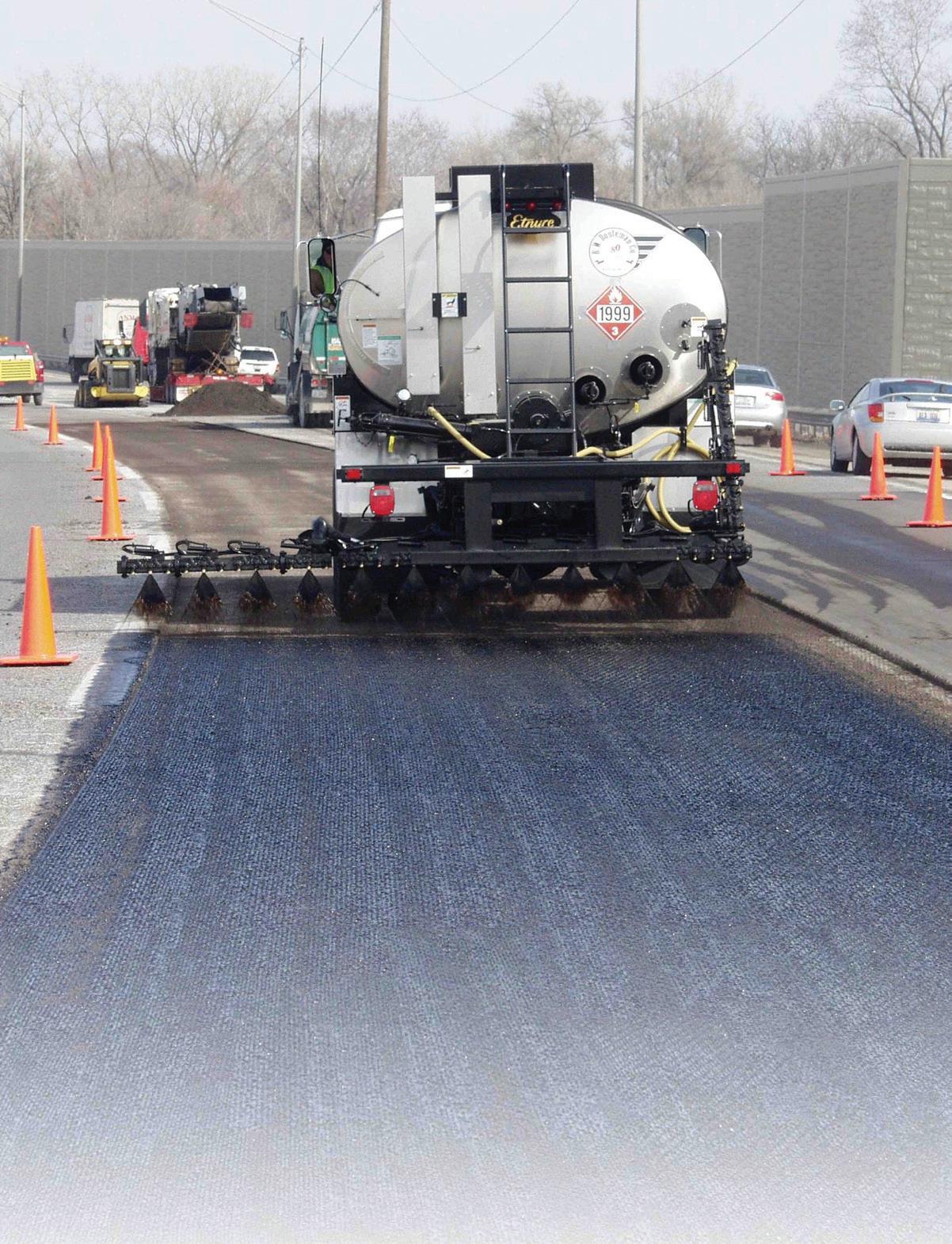

Next, Etnyre designed bituminous distributors, which sprayed oil, asphalt, or tar evenly across a road’s surface to help seal and pave it. As the world clamored for more

paved roads, bituminous distributors were clearly a key to the company’s long-term prospects. The machinery required considerable technical work to perfect, including a burner system to keep the asphalt hot so it could be pumped and sprayed through nozzles.

Etnyre began by selling its machinery through a distributor in Chicago, but as its product line grew and gained a wider reputation, the company set up its own sales operation. E. D. Etnyre was often the chief rainmaker.

His pitches were aimed at the technical-minded people who bought road

A gathering of the Etnyre family at 510 N. Sixth Street in Oregon, Illinois, circa 1928: (standing L to R) George M. Etnyre, June (Strickler) Etnyre, Horace H. Etnyre, Gladys (Bain) Etnyre, Harriet (Smith) Etnyre, Eloise (Robbins) Etnyre (pregnant with Roger), Robert D. Etnyre, Edward D. Etnyre, Edward A. Etnyre; (seated L to R) William E. Etnyre, Joan L. Etnyre, and Robert E. Etnyre.

Etnyre’s Centennial Black-Topper distributor applies tack coat on an asphalt paving project.