LEARNING EARNING THROUGH

AT RANDOLPH COMMUNITY COLLEGE, OUR MISSION IS TO TRANSFORM STUDENTS AND COMMUNITIES BY PROVIDING OPEN ACCESS TO AFFORDABLE, EXCEPTIONAL EDUCATION AND WORKFORCE TRAINING THROUGH PARTNERSHIPS AND EMPLOYEE EMPOWERMENT.

Students celebrate during the 2024 graduation ceremony at the Greensboro Coliseum.

LEARNING EARNING THROUGH

“Although RCC has changed tremendously in size and appearance . . ., its commitment to the people of Randolph County has not changed. The college remains committed to its mission: to serve the people of Randolph and surrounding counties by providing convenient, inexpensive and comprehensive educational opportunities; to inspire in the adult student an active desire for continued personal growth and development, enhanced self-worth, occupational proficiency, responsible citizenship and lifelong learning; and to be an educational and cultural resource center involved with and available to the people of Randolph County.”

DR. LARRY K. LINKER President, 1988–2000

“RCC’s fundamental purpose is personally helping our students succeed and enriching our community. We are committed to our students, to quality educational opportunities, to accessibility, to our community, to our employees, and to leveraging technology and to effectiveness.”

DR. RICHARD T. HECKMAN President, 2000–2006

“Every student who comes to us has a unique story and background, but each has his or her dream and is looking to us for the opportunity to become more than they ever thought they could be. What a wonderful calling we have to be here to help them take those next steps and get them started on the journey of a lifetime.”

DR. ROBERT S. SHACKLEFORD JR. President, 2007–2022

“With RCC 2.0, we are building on a proud legacy while leaning into the future by expanding access, embracing innovation, and empowering every student, every employee, and every community we serve.”

DR. SHAH ARDALAN President, 2023–Present

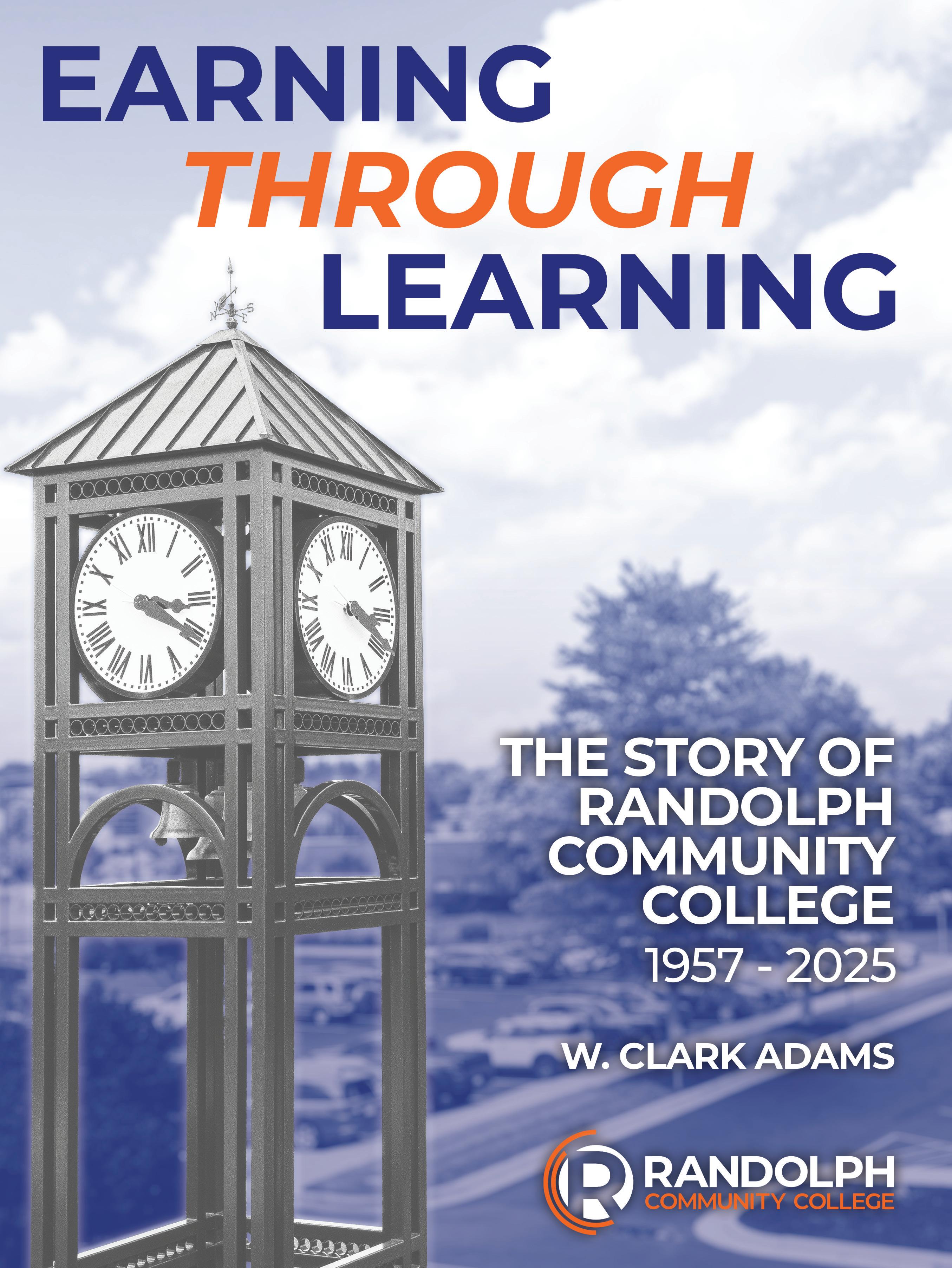

LEARNING EARNING THROUGH

THE STORY OF RANDOLPH COMMUNITY COLLEGE

Copyright 2025 © Randolph Community College

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from Randolph Community College.

RANDOLPH COMMUNITY COLLEGE

629 Industrial Park Avenue Asheboro, North Carolina 27205 336-633-0200 www.randolph.edu

PRESIDENT/CEO

RANDOLPH COMMUNITY COLLEGE

DR. SHAH ARDALAN

AUTHOR

W. CLARK ADAMS

Instructor, English/Communication, Randolph Community College

President, North Carolina Community College Archives Association

BOOK DEVELOPMENT

EDITOR ROB LEVIN

COVER AND BOOK DESIGN

AMY THOMANN

PROJECT MANAGEMENT

STACY MOSER

IMAGE MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION

REN É E PEYTON

INDEX

ALEXANDRA NICKERSON

Covington, Georgia www.bookhouse.net

PRINTED IN SOUTH KOREA

Greensboro, North Carolina, artist William Mangum painted the Foundation Conference Center and its iconic J. B. Davis Bell and Clock Tower for the college's fiftieth anniversary in 2012.

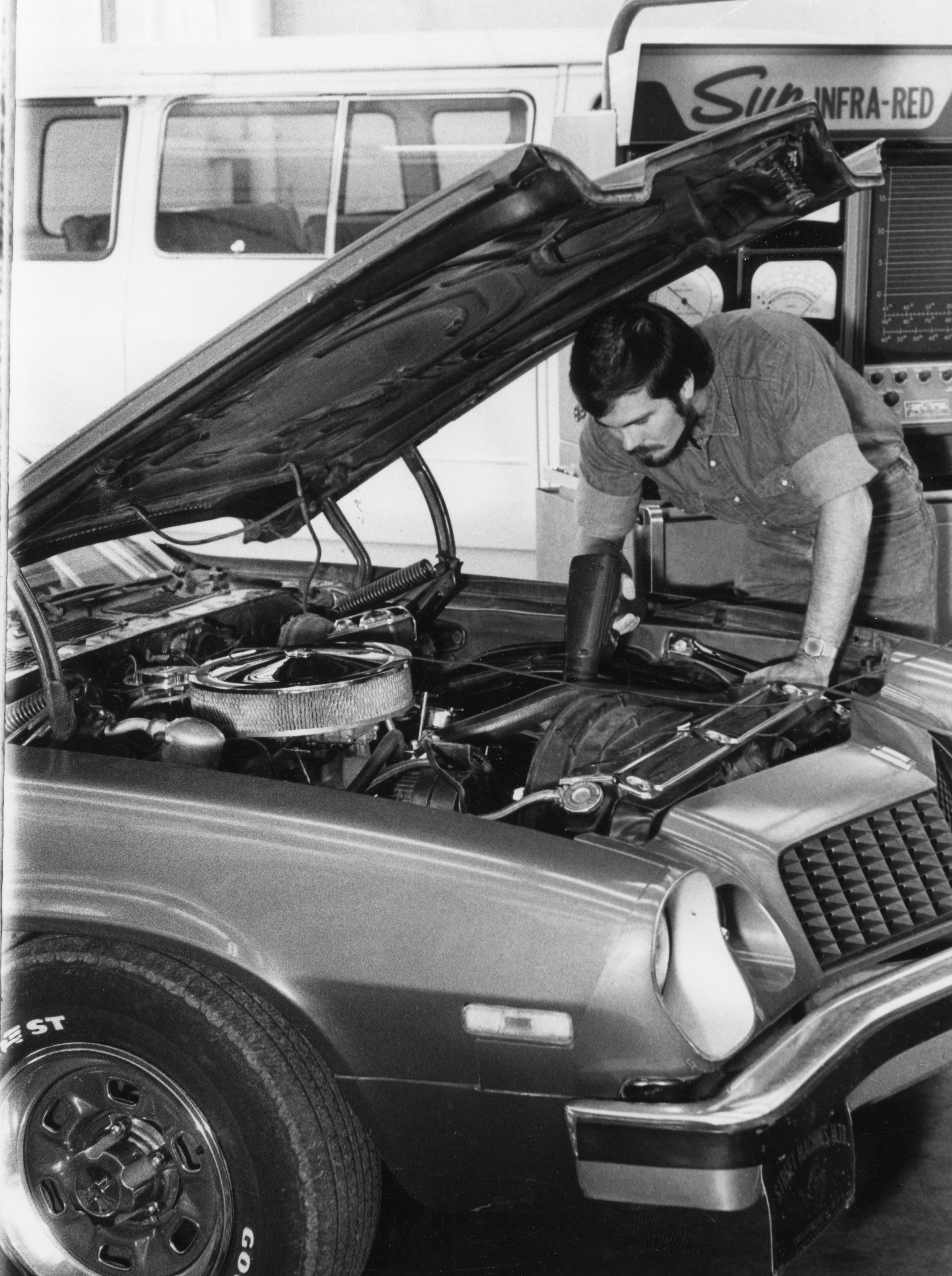

An Automotive Mechanics student works in the shop in the 1970s.

FOREWORD

PREFACE

CHAPTER 1

From Idea to Reality ■ 1957 to 1961 A Seed Is Planted

CHAPTER 2

Randolph Industrial Education Center ■ 1962 to 1965

Training Students for Industry

CHAPTER 3

Randolph Technical Institute ■ 1965 to 1972

Establishing a Force in Technical Education

CHAPTER 4

Randolph Technical Institute ■ 1973 to 1979 Bursting at the Seams

CHAPTER 5

Randolph Technical College ■ 1979 to 1988 A Solid Foundation for Success

CHAPTER 6

Randolph Community College ■ 1988 to 2000 The Community’s College

CHAPTER 7

Randolph Community College ■ 2000 to 2009 A New Millennium

CHAPTER 8

Randolph Community College ■ 2010 to 2022 Creating Opportunities, Changing Lives

CHAPTER 9

Randolph Community College ■ 2023 to 2030 The Dawn of a New Era

APPENDIX I

Randolph Community College Board of Trustees Members

APPENDIX II

Randolph Community College Foundation Board of Directors

APPENDIX III

Randolph Community College Retirees

APPENDIX IV

Excellence in Teaching Award/Staff Person of the Year Award

Adjunct Faculty of the Year

A student in the Radiography Program examines an x-ray.

FOREWORD

The dream that community leaders shared in 1957 for the establishment of a local technical school has since been a part of the growth and development of Randolph County for the past sixty-two years.

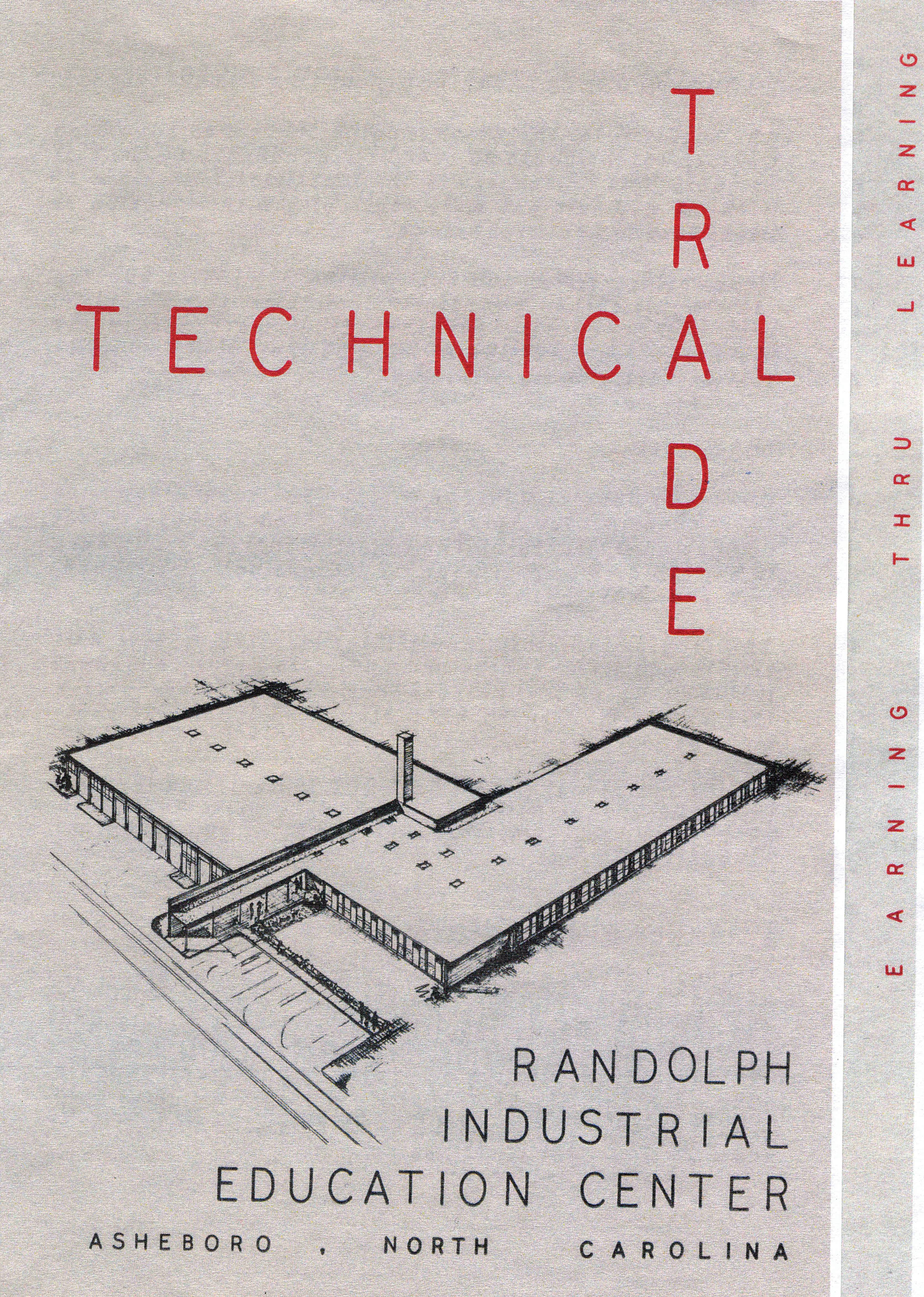

In 1961, Randolph Community College’s first slogan, “Earning Through Learning,” was printed on the first brochure to publicize the new Randolph Industrial Education Center, which opened its doors to students on September 4, 1962. When It opened, the mission of our college was to provide pre-employment and up-grading training for trade and technical occupations for both high school students and adults. Sixty-two years later, Randolph Community College remains committed to our mission as an integral engine of socioeconomic prosperity through significant workforce development services to business and industry, extensive college-transfer programs, technical and trade programs, and community development. Our nationally recognized Apprenticeship Randolph Program is a prime example of “Earning Through Learning,” as students in this program truly do earn while they learn. Randolph Community College has supported local business and industry since 1962 and is now also serving as a lead workforce development partner with Toyota North Carolina, with their $14 billion investment in the county.

Randolph Community College’s story is one of perseverance, pride, and growth, from one L-shaped building in 1962, to twenty-one buildings on the Asheboro campus. Offsite locations include the Archdale Center and the Emergency Services Training Center, with plans for a new Applied Industrial AI Center of North Carolina on the Asheboro campus, a new center in Liberty—which will open in a few years. Randolph Community College has grown from seven faculty members, five staff members, ninety students, and six curriculum programs in 1962 to over two hundred employees, over thirty curriculum programs, and an estimated enrollment of more than ten thousand students in curriculum and continuing education courses in 2024.

It’s an exciting time at RCC! Randolph Community College has many firsts to its name, and it has earned many local, state, and national awards; however, the pride of RCC is the countless lives we have changed for generations, the partnerships we have built, and the community we have served and continue to serve. Our new 2024–2030 Strategic Plan embodies building on more than six decades of legacy and transformation of RCC into RCC 2.0, which stands for relevance, careers, and commitment. As we move into the next chapter of the college’s story, we will stay relevant to the needs of our community and industry. Careers will be at the core of our mission. We are renewing our commitment to each other and to our students, partners, and community. Building on a glorious track record of success, RCC is uniquely and strongly poised for a bright and exciting future.

This magnificently authored book is the history of an extraordinary college, county, and people. I am grateful that Clark Adams, one of RCC’s own faculty members, accepted my invitation to write it because nobody could do it better.

Dr. Shah Ardalan President/CEO, Randolph Community College

Dr. Shah Ardalan

PREFACE

My journey into the field of education began at an early age as I sat under the branches of a towering old oak tree at my grandparents’ home and listened to my grandfather, W. H. Adams Sr., reminisce with his former students, who often stopped by to visit him. My grandfather was a retired vocational agriculture teacher who spent nearly forty years (1935 to 1974) in North Carolina public high schools (Harmony High School, Maiden High School, North Cove High School, and Bunker Hill High School). As a child, I spent countless Sunday afternoons at his home, entertained by stories of his many years in the classroom. My grandfather died in 1998; and, in the years since his death, I wish I would have captured more of his stories from his years as an educator. I began to realize there were so many other educators, just like my grandfather, whose stories were never documented.

My father, Dr. Bill Adams, followed in my grandfather’s footsteps and began teaching agriculture at Western Alamance High School in Burlington, North Carolina, in 1965. In 1969, he became department chair of the Agricultural Technology Program at Davidson County Community College in Lexington, North Carolina, where he spent the next thirty-four years, retiring as chair of continuing education in 2003. He came out of retirement and worked at Randolph Community College, RowanCabarrus Community College, and Central Carolina Community College, before retiring as director of occupational extension at Forsyth Technical Community College in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in 2018, after forty-nine years in the North Carolina Community College System and fifty-three years in North Carolina education. My father was an early employee at Davidson County Community College, as the college had only been in operation for six years when he was hired. Over the years, an immense

amount of rich history has been lost as these early faculty and staff members at community colleges across the state have passed away.

In 2003, I began teaching English at Davidson County Community College and, in 2004, became an English instructor at Randolph Community College. In May 2005, Dean of Library Services Debbie Luck and I realized Randolph Community College’s history had not been well preserved and we established a College Archives Collection to collect, maintain, and preserve the college’s history before it is lost and forgotten.

This book is dedicated to the many pioneers of the North Carolina Community College System, the founders of Randolph Community College, the countless number of faculty and staff members who dedicated their lives to RCC to make it what it is today, and the many students whose lives were forever changed by the education and training they received here. Special thanks go to my parents, Dr. Bill and Libby Adams, for their support during this project; Debbie Luck, now retired, for her encouragement; Dr. Mark Brumley for his technical assistance; and RCC President Shah Ardalan, PhD, for his support of this project. This, the first history written of Randolph Community College, would not exist without the historical materials made available through the RCC Archives Collection that document the college's history and without the assistance of the marketing staff. This book is not meant to serve as a comprehensive history of Randolph Community College but to provide a mere overview of its first sixtytwo years of operation. So many more people have played important roles in our history and many more significant events have occurred, which perhaps will be documented in a future history of the college.

W. Clark Adams Author and Instructor English/Communication

The first building on campus—now known as the Administration/Education Center— shown in early 1963.

Shown here is the Fayetteville Street School, formerly Asheboro High School, where Directors

Al Farkas and Robert Carey worked out of a temporary office until the Randolph Industrial Education Center was constructed.

CHAPTER 1

From Idea to Reality A Seed Is Planted

1957 to 1961

In the late 1950s, Randolph County stood at a crossroads as its economy transitioned from one of agriculture to one of highly mechanized industry— yet many of its residents did not have the training or education necessary to adapt to that changing economy. Under the leadership of Governor Luther Hodges and State Board of Education Chair Dallas Herring, the board undertook an intense study of trade and industrial education throughout the state in 1957. On August 2, 1956, Charles W. McCrary Sr. had been appointed by Governor Hodges as the board’s chair of the committee on terminal education to conduct this study. A Randolph County native, Asheboro High School graduate, Davidson College graduate, leading Asheboro industrialist with AcmeMcCrary Co., president of Randolph Hospital, former Asheboro City School Board member and chair, McCrary was the leader Randolph County needed. One of the first public discussions about the establishment of a technical school occurred at the Asheboro City Board of Education meeting on

January 16, 1957, where McCrary explained that the state board of education would soon create several community technical schools throughout North Carolina and Asheboro and Randolph County would be considered as one of the locations if a request for such a school came from either or both boards. Plans indicated that State funds should be available for all equipment and two-thirds of salaries, with building and operation plans and one-third of salaries a local responsibility. Board members discussed possible sites and the needs of the community for this type of institution. McCrary was asked to inform the state board of education that Asheboro was interested in setting up a technical school and wished to submit a proposal when legislation was enacted. McCrary was also asked to discuss the matter with the Randolph County Board of Education, especially concerning the possibility of a jointly operated school.

On May 6, 1957, it was announced that McCrary made the formal request for the establishment of a technical training institute for Asheboro and Randolph County, the first to be received by the state board of education. He pledged the support of the county and said local aid would be forthcoming for building and operating the school. The Asheboro and Randolph Boards of Education scheduled a dinner meeting for May 13, 1957, to discuss the matter. R. Lynn Albright, chair of the Randolph County Board of Education, and W. Frank Redding Jr., chair of the Asheboro City Board of Education, sent letters that read:

The object of this meeting is to discuss the proposed vocational-technical school, which we are hoping to have located in Randolph County. These new technical schools are subject to final approval by the General Assembly, but it is felt that at least three schools will be established in the state during the next biennium. The proposed schools will operate on a twelve-month year, and the subjects taught will be those most urgently in demand by students and the industries located in the county: such as Machine Shop; Electronics; Drafting; Radio and TV Servicing; Sheet Metal,

Charles W. McCrary Sr. of Asheboro led the efforts to establish the college from 1956 to 1962 as a member of the state board of education.

The McCrary Boardroom in the Administration/ Education Center was named in his honor in 2014.

Tool, and Die Making; Instrument Making; and Quality Control. Students will have an opportunity to study the theories involved and to learn the actual techniques of making and operating the equipment used in modern industry. We need the advice and support of our business leaders, and we urge you to be present at this meeting, which can mean much to the future development of our county. Decision on the location of these schools will depend a great deal on local interest.

A May 6, 1957, editorial in The Courier-Tribune entitled “For a Technical Training Institute,” explained:

On May 13, 1957, an enthusiastic group of more than forty leaders in business and industry, as well as city and county officials and members of the two school boards, filled Acme-McCrary Recreation Center to voice their support for a vocationaltechnical school in Randolph County.

For some time, businessmen of Asheboro have been discussing the need for an intermediate educational institution between high school and college, or university, levels in which men might be trained as foreman, mechanics, technicians, etc. Recognizing the fact that most industries in Randolph county are small in size and limited in their economic ability to employ the technically-trained men required to carry on diverse manufacturing operations, it has been thought that a Technical Training Institute—such as has been located in the Gastonia area— might be the answer to this problem locally. . . . In addition to being a tremendous help to the smaller industries, larger manufacturers are in desperate need of such technically-trained men and at the present time are trying to find them elsewhere in the state, only to learn that they are about as scarce in other quarters as they are in Randolph county. The need for trained tool and dye makers, workers in electronics, mechanics in various fields, and others with technical training sufficient to enable them to handle supervisory and other important tasks, has become acute in this area. In view of all this, the city and county boards of education jointly have filed a request for a technical institute, if any are made available in this session of the State Legislature.

On May 13, 1957, an enthusiastic group of more than forty leaders in business and industry, as well as city and county officials and members of the two school boards, filled

Acme-McCrary Recreation Center to voice their support for a vocational-technical school in Randolph County. Speaker after speaker from virtually every community in the county spoke out for the school as a means to develop Randolph’s industrial potential, bridge the gap between the production worker and engineer; increase the per-capita income of the county, and stimulate interest in new and expanding industries. McCrary explained that possibly three vocational-technical schools would be established in the state—one in the west, one in the east, and another in central North Carolina. If Randolph County was selected as a site, the school would be operated jointly by the Randolph County Board of Education and the Asheboro City Board. Local communities would be expected to provide funds for the land and building (approximately $75,000), but operational expenses would be furnished by federal, state, and local funds. The State would provide the equipment needed. Courses would be mostly taught on the high school level, offering instruction to high school students, graduates, and dropouts, and night classes would be offered for adults. No tuition fee would be required for any student residing in Randolph County, but out-of-county students would be charged a nominal fee. Some of the course subjects that could be offered were Basic Machine Shop, Blueprint Reading, Tool and Die Making, Electronic Control and Maintenance, Air Conditioning, TV Maintenance, Refrigeration, Metalwork, Drafting, Instrument Making, and Quality Control. McCrary explained the purpose of the school was not “. . . to develop workers for a hosiery mill or for a textile plant, but to turn out technicians who will be of value in almost any industry.” J. O. Devries, manager of the General Electric plant in Asheboro, said his company had long felt the need for such a vocationaltechnical school. “Industry today is reaching for men with a partial technical education,” said Devries. “We have our public and private institutions for engineers and higher education, but we feel the need for men with some technical skill. We are now going out of the state for our own [employees] because we can’t find them here. We find that Randolph County people learn and learn rapidly. The boy coming out of high school has a better chance in industry if he has some technical knowledge or skill. Industry is becoming more and more mechanized . . . more engineering . . . more blueprints . . . more electronics . . . more tooling. There are not enough people to take up the gap.”

McCrary explained the purpose of the school was not ‘. . . to develop workers for a hosiery mill or for a textile plant, but to turn out technicians who will be of value in almost any industry.’

Cleveland Thayer, district manager for Carolina Power & Light Company, who later served as chair of the school’s first senior advisory committee and the first vice chair of the board of trustees, claimed, “We have lost many, many industries because we did not have these technicians.” Those in attendance at the May 13 meeting gave their unanimous approval for a

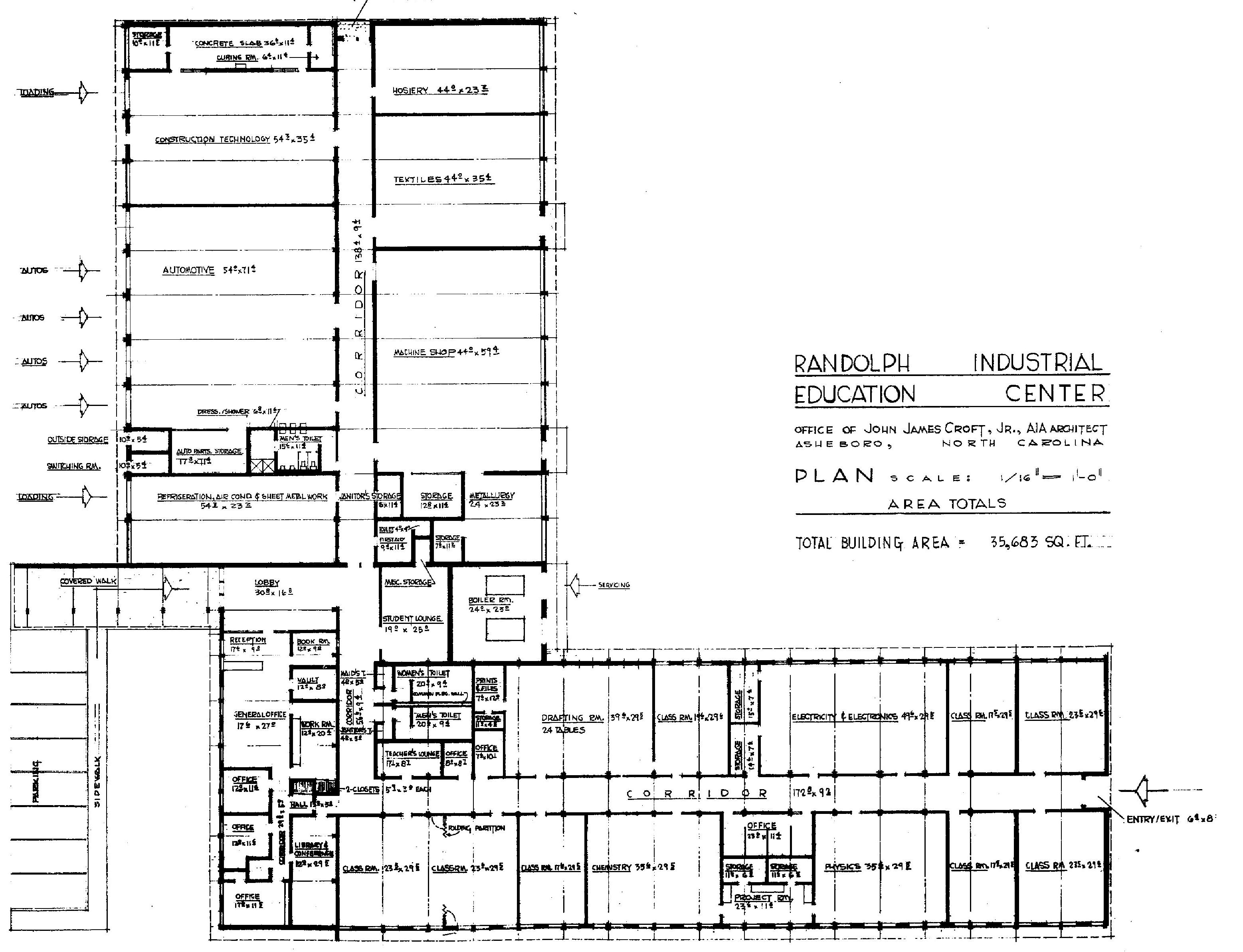

By September 1960, design plans for the new Industrial Education Center were being finalized by J. J. Croft, a local architect, and a tentative curriculum was developed.

technical training institute and felt Randolph County was ideally situated for one due to its central location in the state.

On June 12, 1957, the North Carolina General Assembly passed State Bill 468, which provided $500,000 to initiate a statewide system of industrial education centers. The state board of education had sought $1,000,000 from the legislature to establish the three schools, but the legislature cut that amount in half, so plans for the school in Randolph County had to be reconsidered.

On January 8, 1958, J. Warren Smith, state director of vocational education, explained the purpose and operation of an industrial education center to the county board of education, and also how to make a formal application to be selected as a site. Many local school units across the state submitted applications to the state board of education between February and March 1958, including Randolph County. On April 3, 1958, the board approved six sites: Leaksville-Rockingham, Guilford, Burlington, Wilmington, Durham, and Goldsboro. Wilson was added to the list on April 11, 1958. Eleven areas approved for the next biennium were: Asheville, Sanford, Davidson, Lenoir, Winston-Salem, Hickory, Raleigh, Fayetteville, Charlotte, Gastonia, and Randolph.

On May 11, 1959, McCrary described the progress being made in securing an industrial education center for Randolph County at an industry-seeking session of business leaders. Randolph County was in the second group of communities scheduled to receive State funds from a special statewide bond issue scheduled for October 27, 1959, for the school and to benefit educational institutions, mental hospitals, local hospitals, and a state center for the blind, yet the bond issue was defeated locally.

Randolph County’s dream of building an industrial education center was later revived when Ira L. McDowell, chair of the Randolph County Board of Commissioners, reported on

January 27, 1960, that the board was contemplating a call for a $3,500,000 school bond election to benefit both Asheboro and Randolph County schools. The first $350,000 would be used to construct a building for the Randolph Industrial Education Center (IEC). A seven-acre tract of land near the intersection of Albemarle Road and Park Street northwest of Asheboro High School was provided at no charge to Randolph County taxpayers by the Asheboro School Board. The industrial education center was described as filling a critical need for the area, as it provided technical training in industrial skills for high school students and night classes for adults who desired to “upgrade” their skills in their current positions or train for a new vocation. The county and city school administrative units would provide a building on land provided at no cost to the County, and the State would equip the building with $150,000 worth of equipment, pay for its operation, and provide trained technicians as instructors. The IEC would provide training in basic industries (oriented to local manufacturing) for county high school graduates who were unable to attend two- or four-year colleges or business schools, or whose employment prospects were only as unskilled laborers or in military service. An editorial titled “School Bond Issue Incorporates Vast Improvements to Schools” in the May 26, 1960, edition of The Courier Tribune expressed, “There would be a ready market for services of young men with one or more years of special training with industrial machinery. The benefits of the industrial training center would be felt county-wide.” Admission would be open to county residents on an equal basis. No tuition would be charged to residents of Randolph County, while residents of Anson, Montgomery, Stanly, and other counties would be charged a tuition fee. Both day and night classes would be available, and adults desiring to learn a certain trade would be eligible to attend as well as high school students.

advisory committee

the Randolph Industrial Education Center from 1961 to 1963 and as the first vice chair of the college's board of trustees from 1963 until his death in 1973.

An editorial in The Randolph Guide on February 17, 1960, titled, “Jobs—Today and Tomorrow,” emphasized:

We must provide a building. More important is the fact that we must have trained technicians if new industry is to be attracted to Randolph County. The Educational Training Center would be flexible enough in its curriculum

Cleveland H. Thayer, retired district manager of Carolina Power & Light Company, served as chair of the senior

for

and scope to include training in those skills which are most needed. We are in a transition period caused by the mechanization of farming operations and a slump in the full-fashioned hosiery market. Most of our people will be forced into going into other lines of work at a time in their careers when they had hoped to be able to ‘take life a little easier.’ Randolph County’s Technical Education Center would provide both adults and students of high school age an opportunity to learn professions of a technical nature. The school is needed and is needed now.

Randolph County School Superintendent W. J. Boger Jr. and Asheboro City School

Superintendent Guy B. Teachey promoted the bond issue along with school board members of both school systems who saw the industrial education center as an opportunity to provide technical training and attract new industry. A May 18, 1960, editorial in The Randolph Guide titled “An Expanding Population” made it clear that: “Our future growth, however, will be measured in our ability to continue to expand our present industries and to attract new ones.” It urged voters to support the bond for school construction, part of which would go toward building the new Randolph Industrial Education Center. “Can we afford to let this opportunity pass by?” asked the editor.

The fate of the Randolph IEC rested on the May 28, 1960, bond issue vote that local educators claimed was the most critical decision on education ever to come before Randolph County citizens. It was expected to draw one of the largest groups of voters ever to cast ballots in an election in Randolph County, with some estimates asserting there would be more than 15,000 votes. As it happened, the turnout was smaller and the bond issue passed, with 6,295 for and 2,711 against. Randolph County would soon have the industrial education center for which so many had worked so hard since 1957.

The fate of the Randolph IEC rested on the May 28, 1960, bond issue vote that local educators claimed was the most critical decision on education ever to come before Randolph County citizens. It was expected to draw one of the largest groups of voters ever to cast ballots in an election in Randolph County, with some estimates asserting there would be more than 15,000 votes.

On June 16, 1960, Asheboro City Schools Superintendent Guy B. Teachey announced that a survey, sponsored by the state division of vocational education and the city and county school boards, to determine necessary training and curriculum for the IEC, would begin in August. The survey was distributed throughout larger local industries, and as many smaller firms as time permitted, by Merton H. Branson, a distributive occupations coordinator at Asheboro High School, who tallied its results. Teachey also announced that a joint city-county committee, appointed from

the membership of both Randolph County and Asheboro City School Boards to serve in a policy-making capacity, would be formed to begin planning for the school. R. Lynn Albright of Coleridge, Ernest C. Routh of Randleman, Wade H. Harris of Seagrove, and Randolph County Schools Superintendent W. J. Boger Jr. composed the “county half” of the committee. On August 29, 1960, the “city representatives” of the committee were named—W. Frank Redding Jr., chair of the Asheboro City School Board; Superintendent Teachey; and ex-officio members

Robert L. Reese and T. Henry Redding. The first task of the committee was to appoint an architect for the new industiral education center.

The joint city-county committee met with Wade Martin, state supervisor of trade and industrial education, on September 12, 1960, to discuss construction plans. Tentative approval of the general overall design of the 30,000-square-foot building was given, and it was hoped that it would be completed by January 1, 1962.

The committee announced there would be a three-phase program at the industrial education center. The first would be for select high school juniors and seniors pursuing vocational work—this would supersede the city school program but would offer far wider opportunities to rural students. Second, a technical course for adults would allow them to upgrade presently possessed skills or receive instruction in new fields. The third phase would consist of a two-year technical course, which would comprise a thirteenth to fourteenth high school grade for graduates.

Branson’s August 1960 survey results identified several fields of instruction needed: Auto Mechanics (diesel and farm mechanics); Machine Shop-Metalwork; ElectricityElectronics; Welding; Air Conditioning-Refrigeration-Sheet Metal; and Drafting and Design.

On September 15, 1960, Superintendent Teachey explained, “The school program will be flexible and closely allied with the industrial community for frequent upgrading. Supervisory subcommittees in each field, composed of specialists in each particular subject, will be named at a later date.” Based on the curriculum study, architects would begin planning general building design to accommodate each type of training. For instance, interior walls would be designed so that they could be changed to suit the needs of a particular

T. Henry Redding served as chair of the joint city-county advisory committee that led the school from 1960 to 1963, prior to the formation of the board of trustees.

is

course. The committee noted that part-time instructors could be employed from within the community and possibly from industry, too.

In October 1960, the joint city-county committee began searching for a director for the center, preferring someone with experience in vocational training and administration of such a program. T. Henry Redding was unanimously chosen as chair of the committee, which selected local architect J. J. Croft Jr. to prepare sketches of the proposed building and to orient the building based on the center’s curriculum, possible future expansion, and parking requirements.

On November 22, 1960, Randolph County commissioners gave full endorsement for the establishment of an industrial education center in Asheboro. On December 10, 1960, a new twenty-two-acre site at the city’s industrial park, which was countyowned, was chosen to provide for future expansion. That property, nearly one hundred acres in size, had been acquired by the County from the airport commission in 1955, when it ceased to be used as an airport. County commissioners requested that educators use only what land was needed of the site, which was highly desirable for new industries, as it offered railroad facilities and was close in proximity to four major thoroughfares: US Hwy. 64, US Hwy. 311, US Hwy. 220, and NC Hwy. 49. Redding explained the new location not only provided space for future expansion, but also adequate areas for parking and grounds landscaping. The engineering/surveying firm Moore, Gardner, and Associates of Asheboro, North Carolina, began work on grading plans for the property.

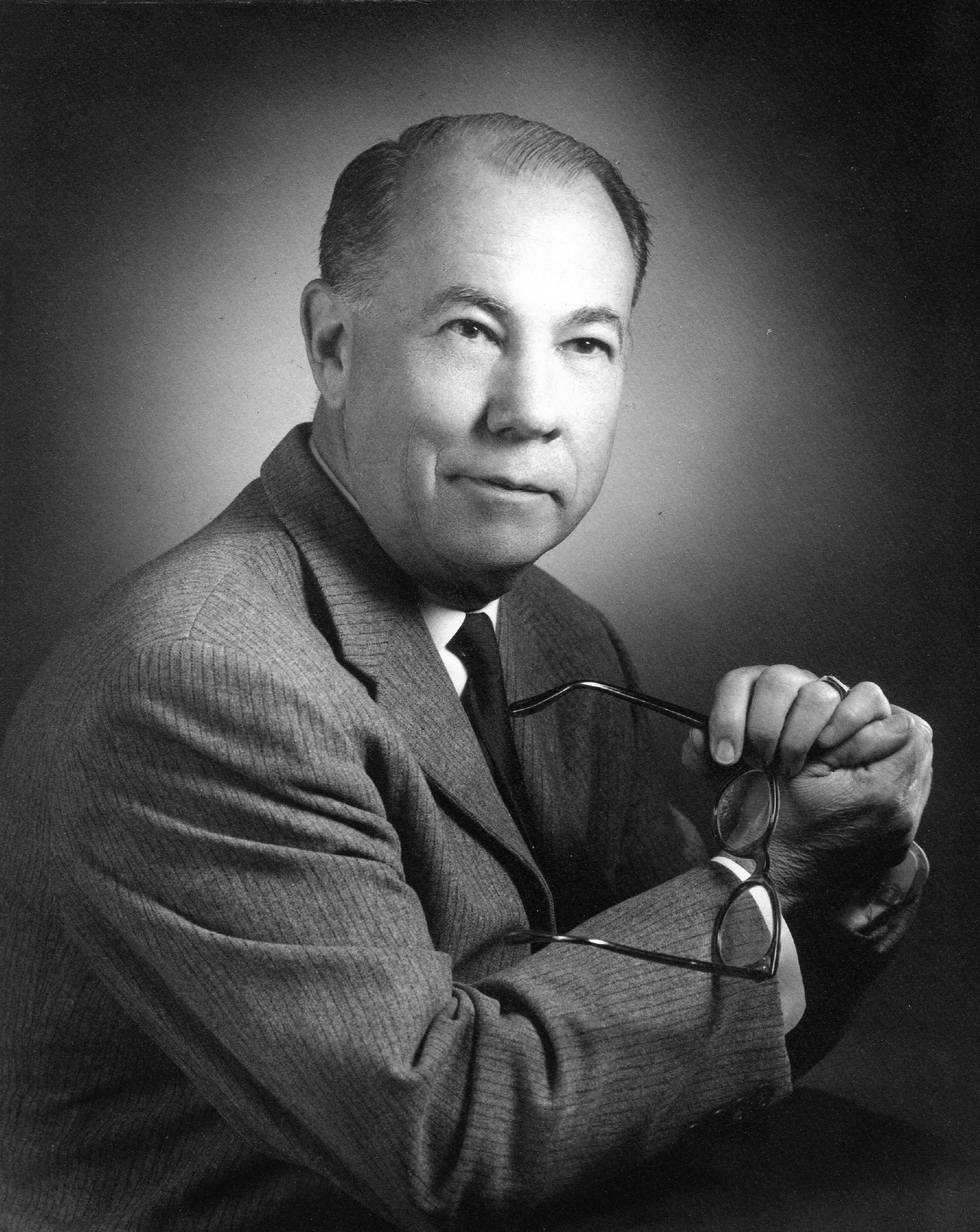

Al G. Farkas was the school's first director from 1960 –1961. The chief administrators of Industrial Education Centers were designated as directors instead of presidents, but the duties of the position were identical.

Forty-two-year-old Alois (Al) G. Farkas, an associate professor of civil engineering at North Carolina State College since 1955, was hired as the first director and employee of the industrial education center on December 1, 1960. Upon accepting the position, Farkas said, “Through an intensive two-year program, such as this Industrial Education Center can offer, we shall be able to give advanced training to both men and women which would prepare them for a more productive life in our modern industrial community. This should increase per-capita income and consequently benefit the individual and his community as well as the local industry.”

Because the first building had not been constructed on the campus, Farkas worked out of an office in Fayetteville Street School, near downtown Asheboro, with only a desk and ideas for what the new school could be. “We’re trying to learn from experience . . . from the mistakes of others . . . and, in the long run, drawing from the many sources of information available, we

should construct a fine school in Asheboro,” said Farkas in January 1961. In March that year, T. Henry Redding, W. J. Boger, and Farkas toured the industrial education center program in Connecticut to obtain ideas for the development of their own industrial education center. Farkas explained that the curriculum “must be justified by demand in the area and, even once the school’s shell is built, we’ll continue to study our present curriculum needs.”

Farkas distinguished between the concepts of the center as a “technical” rather than a “trade” school—he envisioned that it would largely provide a wider base of training for the student as a technician, rather than merely offer education in the operation of a single machine—specialization. “We’ll be prepared to set up ‘crash’ programs in specific fields, when necessary,” said Farkas. “These short courses provide skill only with the operator’s hands, though, with no background instruction in related subjects, physics, mathematics.” Evening classes for adult students were to be the first classes offered to upgrade skills of those

This image shows the original floor plan for the first building on campus, now known as the Administration/ Education Center.

who were presently employed, in addition to supervisory-development courses. Terminal classes, roughly a thirteenth and fourteenth grade, would be available for post-high school training, and later a system could be worked out where selected junior and senior students would attend their high school classes for half the day and then they would attend classes at the center for the remainder of the day. “But our primary purpose is to serve Randolph

Alois (Al) George Farkas (August 10, 1918–February 14, 2011) Director (December 1, 1960–November 10, 1961)

Al G. Farkas, born in Vienna, Austria, on August 10, 1918, immigrated to the United States, arriving in New York in 1927. Farkas grew up in Maplewood, Missouri, and obtained his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in civil engineering from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. He also studied nuclear reactor engineering at Argonne National Laboratories in Illinois and completed a short course in nuclear engineering at North Carolina State College. He served in the U.S. Army from 1944 to 1946 at Harlingen Air Force Base in Texas as a draftsman and remote-control turret mechanic and rose to the rank of sergeant before being honorably discharged on May 4, 1946.

He had previously served as chief field design engineer for Stone and Webster Engineering Corporation on the construction of the Roanoke Rapids hydroelectric power station and he served as structural design engineer in its main office in Boston. He served as structural design engineer on steam power plants, a chemical plant, and other hydroelectric works; construction field engineer, office engineer, and construction supervisor for a synthetic rubber plant for Stone and Webster and several steam power plants; and as construction field engineer for M. W. Kellogg Company on two one hundred-octane gasoline catalytic cracking units.

His work on the Roanoke Rapids hydroelectric project is what brought him to North Carolina in the early 1950s. When he began as director of the Randolph Industrial Education Center, Farkas’s job was to contact local businesses and industries and develop and conduct surveys to determine the vocational training needs of the area. He also traveled to Texas and Connecticut to visit vocational-technical schools and study those programs in preparation for the design and development of the Randolph Center. Farkas worked closely with local architect J. J. Croft Jr. in the planning and design of the first building on campus, now known as the Administration/Education Center, and he also worked with S. E. Trogdon and Sons, general contractor, on the initial construction of the building in 1961.

Farkas developed the initial programs the school could offer by proposing and developing materials for such occupations and industries as Automotive Mechanics; Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Heating; Machine Shop; Welding; Technical Drafting; Electronics; Radio and Television Repair; Construction Technology; and an operator-type program for the area hosiery-textile industries. In 1963, Farkas was hired to start the Civil Technology Program at the new Central Piedmont Community College in Charlotte, where he later became the department chair and retired in 1984.

After a forty-six-year separation, Farkas reconnected with Randolph Community College in 2007 via English Instructor Clark Adams and attended its forty-fifth anniversary ceremony, where he was recognized for his contribution to the initial development of the college. Farkas died at age ninety-two on February 14, 2011.

County—we hope for all these people [the center’s students] to have a job when they graduate, requiring close cooperation with industries largely located nearby. We’re depending upon this industry,” Farkas remarked.

On April 24, 1961, Culp Brothers Inc. of Gold Hill, North Carolina, cleared the site’s underbrush in preparation for construction of the new center and Farkas began accepting student applications in May for evening classes to begin in September. If enough interest was shown, daytime classes could be started. Unfortunately, due to a lack of interest, no classes took place.

In August 1961, after S. E. Trogdon and Sons was selected as general contractor, a senior advisory committee was formed by the joint citycounty committee, consisting of Chair Cleveland Thayer, John Rentz, Ernest Berliner, Buick Woodley, Fred A. Thomas, T. A. (“Cap”) Johnson Jr., Robert Reese, and Wallace Renfroe.

In what is likely the first brochure ever created to publicize the Randolph Industrial Education Center in 1961, an architect’s rendering of what is now known as the Administration/ Education Center is included, along with the words Technical and Trade, and the slogan “Earning Thru Learning” is printed on the cover. Inside, the purpose of the IEC is described:

This is believed to be the first brochure to publicize the new school. It was printed in early 1961 before the actual opening of the college on September 4, 1962.

Our rapid developments in science and technology have been accompanied by equivalent rapid changes in our occupational structure. The requirements for proficiency in any field of employment are increasingly comprehensive and exacting. The programs of this Industrial Education Center will enable qualified youths and adults to obtain advanced training, which will prepare them for a more productive life in our modern technological and industrial community. For the individual and for both new and existing industry, this type school will provide a pre-employment or an up-grading type of training for the trade and technical occupations.

On November 1, 1961, Robert E. Carey began work as the new director to replace Al Farkas, whose resignation was effective November 10, 1961. Mrs. Eugenia Gardner was hired as secretary on November 13, 1961. Carey and Gardner were the center’s only employees until Erman S. Cox, the first maintenance supervisor, was hired on January 1, 1962. They spent several months working in the Fayetteville Street School office as construction of the original building on campus continued. In December 1961, Carey began to appoint craft committees to assist in planning curriculum and to recommend equipment needed for each program.

During his first month, Carey oriented himself to Randolph County, contacted newspapers, and went on a lecture tour, speaking to numerous civic groups, business and industry leaders, and high school students. Carey also met with state board of education representatives to obtain assistance in setting up the center, from equipment to a publicity program.

Mr. Robert Elezer Carey (February 1, 1908–February 27, 1985) Director (November 1, 1961–December 31, 1963)

Robert E. Carey was born on February 1, 1908, in Mountain Top, Pennsylvania, received his BS and MA in Industrial Education from Penn State University, and spent approximately thirty-three years in the fields of education and industrial training. From 1933 to 1942, he was employed as a high school teacher in Mountain Top, Pennsylvania, then in Royersford, Pennsylvania, and Pitman, New Jersey, where he taught English, General Science, Mechanical Drawing, and Woodworking. He also taught Industrial Organization and Management at the University of Detroit.

Carey served in the U.S. Navy from 1942 to 1945, where he organized induction programs for recruits entering aviation training school. He taught hydraulics and wrote and edited training manuals on electricity, hand tools, dope dyeing and fabrics, engines, and hydraulics. From 1945 to 1949, he worked for the Dodge Division of Chrysler Corporation in Detroit as a conference leader and foreman trainer. Carey was also employed as a training director for the Motor Products Corporation in Detroit, training foremen and college students for junior executive positions, from 1949 to 1954.

From 1954 to 1961, Carey was employed by the Arabian American Oil Company of Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, and Sidon as a lecturer, senior trainer, and teacher. He prepared and delivered lectures for the induction of new employees, improving American employees’ qualifications to work in Saudi Arabia. He also organized and conducted informational sessions for foremen and taught English and mathematics to Arabs. Carey was highly recommended to serve as director by the North Carolina Department of Education and by members of other industrial education centers in the state. He and his wife, Elisabeth, were known for their lectures throughout Randolph County, illustrated with photos of the people, ruins, progress, and conditions in Saudi Arabia. Carey left Asheboro in 1964 and moved to Orlando, Florida, where he died at age seventy-seven on February 27, 1985.