ROADWORK

125 YEARS OF E. D. ETNYRE & COMPANY

It generally comes as a surprise to even those who are familiar with E. D. Etnyre & Co. that its incredible story had very humble beginnings—it all began when a light bulb went off in the mind of Edward Daniel Etnyre more than one hundred twenty-five years ago on a farm in Oregon, Illinois. Inspired by a common frustration— how to more efficiently provide water for livestock—E. D. and a friend began to tinker with a simple hog trough and hose. The result was an ingenious watering system, a product welcomed by farmers far and wide. That, in turn, led to other inventions by this resourceful young man, notably the motorized Etnyre Patent Sprinkler, designed to spray water to eliminate clouds of dust created by new-fangled vehicles on dirt roads.

As Etnyre’s mechanical inventions proved more and more popular, this visionary realized that his family’s future would not only be inexorably tied to his deep personal commitment to his customers—but also to the burgeoning presence of “horseless carriages” on American roads. Indeed, more automobiles traveling on rough, dirt roads meant more dust and slower travel times, resulting in unhappy travelers and

farmers who clamored for smoother, safer journeys.

Word spread of Etnyre’s roadimproving machines, and his company was awarded government contracts as American highways were established and airfields were prepared during WWII. This growth was carefully shepherded by the Etnyre family, who set a high bar for company performance and reliability.

Fast forward to today—Etnyre has expanded its reach exponentially, innovating to meet the diverse needs of the asphalt road-construction industry across the globe.

But, at its core, the organization’s leadership recognizes that its success relies on its people. In the words of fourth-generation Bill Etnyre, board chair, “It’s exciting to see the enthusiasm from all the generations who want the company to grow and improve lives near and far for many years to come.” In fact, he says, “I’d like to see this family business last another 125 years.”

Bill

Gordon

Melissa

Author

Welcome to the 127-year-old story of Etnyre International! We wouldn’t be here today without all the people who paved the way—members of the Etnyre family starting with my great-grandfather and grandmother, E. D. and Harriet Etnyre, the company members from years past, and those present. To you and to our communities, customers, dealers, and suppliers, we say thank you.

Little did anyone know in the early days we would become one of only about 1,000 American companies to still be running at 100 years. And what a company! As we move ahead, let care, humility, trust, respect, and integrity guide us in improving the lives of people throughout the world.

William S. Etnyre, PhD. Chair of the Board

I have had the honor of guiding this organization through seven years of pivotal transformations. We have embraced significant change, blending the wisdom of our storied past with bold steps into the future. And what excites me is where we are headed.

Etnyre’s foundation was forged through the family’s commitment to its stakeholders—members, customers, suppliers, and the communities. This book captures that story of decades of hard work and creativity.

Our future is one of purpose-driven progress, focusing on improving lives by serving the world’s infrastructure needs. Our roadmap will harness state-of-the-art technologies, global partnerships, and focus on sustainability. Moving forward, we will continue to challenge the possibilities with an eye on making the world a better place.

Ganesh Iyer, PhD. President and CEO

As we pause to recognize and reflect on Etnyre’s anniversary, I am flooded with gratitude.

n Gratitude for all the members past and present.

n Gratitude for our partners, suppliers, and our communities.

n Gratitude for our customers, many of whom are friends.

n Gratitude for the prior Etnyre family members who dedicated their lives to this business.

We know the future will be neither easy nor certain but there remains a desire and dedication to keep going and for that I am also grateful. My heart-felt Thank You to all who have been part of this journey.

Don Etnyre Member of the Board

This book documents and celebrates the history of E. D. Etnyre & Company, one of the most respected names in the manufacture of road building and maintenance equipment. In telling the story of the company’s first 125 years, two themes stand out:

First, Etnyre makes things. It doesn’t simply assemble components constructed elsewhere; it fabricates many of its parts from scratch. While it is a modern manufacturing operation, Etnyre remains at heart a series of old-school craft shops orchestrated to produce sophisticated road machinery. E. D. Etnyre, who founded the company during the 1890s, would no doubt marvel at some of the robotic and computerized equipment now used in the factories that bear his name, but he would still recognize the skilled shop work that drives the process.

Second, Etnyre is about family. This means the actual family, of course: the generations of Etnyres who founded and built the company, who worked there and owned shares, who guided its board and charitable endeavors— and still do. But it also means the hundreds of non-family members who have worked with Etnyre and been treated as extended family through employment practices, benefits, loyalty, friendships, and day-to-day camaraderie. Indeed, the company doesn’t call them employees but members.

It is remarkable that any business lasts more than a century and a quarter. It is even more remarkable that it has done so while remaining a private company owned by the same family. These accomplishments are worth honoring and looking back upon.

This farm raised well-hydrated hogs thanks to an efficient, new watering system invented in the late 1800s by

CHAPTER ONE

In the atrium of E. D. Etnyre & Company’s offices in Oregon, Illinois, a display depicts the early history of the business. Most of the items show what you would expect from a company that manufactures and sells road building and preservation equipment: a horse-drawn tanker, a horse-drawn oiler, a 1922 truck that cleaned streets by flushing them with water. But one display looks out of place. In the midst of the carefully restored vintage vehicles, three dummy hogs that seem to be smiling stand facing a watering trough.

This agricultural still life isn’t the outlier it seems. The hogs and the trough are a cherished part of the Etnyre story. Figuring out how to water livestock more efficiently provided the inspiration that led to the founding of the company that has now done business for more than 125 years.

The man who devised the watering system and later started the company was Edward D. Etnyre. He was a fourth-generation descendant of German immigrants who came to America from the hamlet then known as Euteneuen, on the

Sieg River in the Rhineland. His surname, which appears in different spellings over the years, is thought to be drawn from ancient words that mean, appropriately, “new road.”

In pursuit of that new road, Edward’s great-great-grandfather, Johannes, who spelled his surname Eideneier, boarded the ship Queen of Denmark in 1751 and sailed from Rotterdam to Philadelphia, the receiving port for most early German settlers in the American colonies. He gravitated to western Maryland, where he farmed and began a family. Two generations later, his grandson, John Etnyre, a War of 1812 veteran who used a simplified spelling of the name, migrated by steamship and covered wagon to the Northwest Territory of northern Illinois.

He landed in a new town called Oregon, on the Rock River, a beautiful setting with rolling hills and outcrops that break the level plains running a hundred miles west from Chicago. The area had once been the home of indigenous tribes—the Sauk, Potawatomi, and Winnebago—but they

Oregon’s first mayor, James V. Gale, noted in his diary that Daniel Etnyre bought out the other heirs. “He has been a successful farmer and good citizen. . . . He is a man of few words and much respected by his fellow townsmen.”

were rapidly displaced by new Americans seeking a better life, most of them from New England. In a sign of things to come, one of the pioneer settlers a few miles south in Grand Detour was a blacksmith named John Deere, who would become famous for devising a self-scouring plow that could break up the rich prairie soil.

John Etnyre paid $1,600 for a land claim outside Oregon but he wasn’t able to farm it. He died only a few months after arriving in 1839. Some years later, Oregon’s first mayor, James V. Gale, noted in his diary that Daniel Etnyre, one of John’s sons, bought out the other heirs. “He has been a successful farmer and good citizen. . . . He is a man of few words and much respected by his fellow townsmen.”

Daniel Etnyre was indeed a bedrock of the community. In addition to farming, he worked as a carpenter and opened the Rock River Furniture Company. He also founded the First National Bank of Oregon. Among the children he and his wife, Mary, had was Edward Daniel Etnyre, born in 1859.

Edward Daniel Etnyre—who went by his initials: E. D.—grew up working on the family’s 480-acre farm west of Oregon. By the time he reached young adulthood in the late 1870s, his parents were doing well enough to send him away to college at Northwestern University, where he became an accomplished athlete and helped

In the early days, “road oil” was applied directly to dirt roads to settle the dust— building a base for future road improvements.

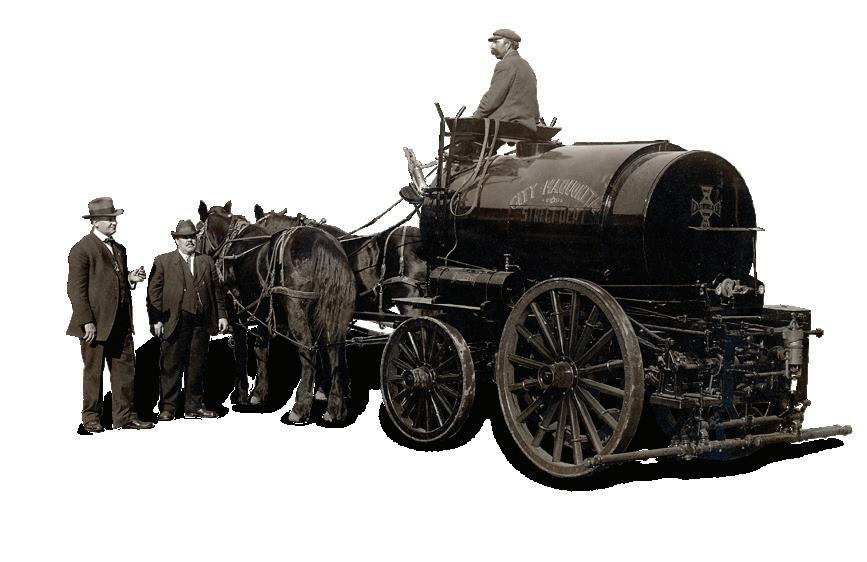

The Etnyre Patent Sprinkler (1900)

This machine, a design extension of the water tanks that serviced steam threshers in the fields, propelled Etnyre into the road business as it sprayed water to keep down dust on dirt surfaces. The sprinkler was soon adapted to spray oil as well. Early models were horsedrawn, then they were redesigned to work with motorized vehicles.

organize its first baseball team. He was a pitcher of relatively small stature, hence his nickname: Bantam.

He didn’t stay in college long. “He was tired of it,” one of his sons, Robert “R. D.” Etnyre, remembered in a 1973 radio interview. “He wanted to go out West, so his father made arrangements, and he did go out West—riding the plains, buying cattle.”

E. D. had another motivation. His girlfriend in Illinois, Harriet M. Smith, had moved to northern California with her family. While Etnyre experienced the life of a cattleman, he rekindled their romance, and they were married in Sacramento in 1885. The Freeport Daily Bulletin back in Illinois ran a brief about the wedding, describing

Etnyre as “the son of a rich banker” (perhaps exaggerating) and saying that the couple would soon return “to occupy their home of comfort at the pretty little city on the Rock, where their courting began.”

E. D. and Harriet started a family, and he farmed for several years before his restless spirit again altered his fate. Etnyre liked to tinker with things. Sometime during the 1890s, he wondered whether there was a better way to bring water to livestock than getting up early day after day to laboriously fill the troughs by hand. He started working with Chet Nash, an acquaintance and Civil War veteran, who had a mechanical shop in Oregon. They came up with an automatic watering system that operated with

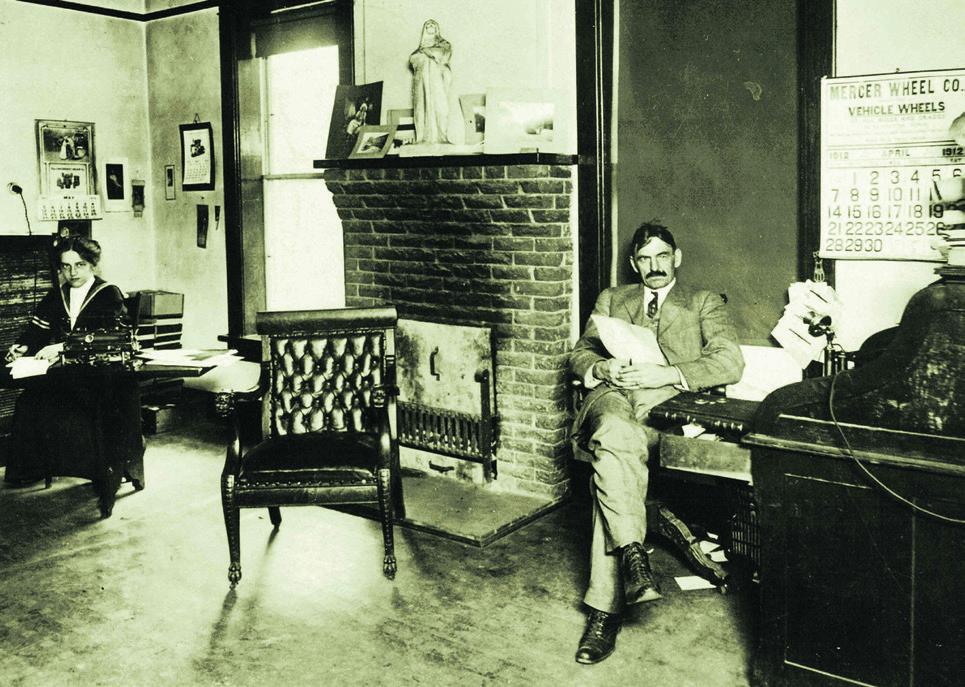

In the fledgling years of the horseless carriage, hundreds of wagon-builders and bicycle shops across the Upper Midwest tried their hand at the new technology. As E. D. Etnyre was already making road equipment, it stood to reason that he would tackle manufacturing automobiles as well. ◆ Etnyre built three “gas buggies,” as he called them, in the early years of the twentieth century. The first models had hard rubber tires and fourteen-horsepower engines that were air-cooled and featured a two-seat bench made of horsehair and leather over springs. He sold one to a local farmer and kept one for his family, which his sons drove hard around Oregon, wrecking it now and then. He sold the third model to John Prasuhn, a sculptor who worked on the Black Hawk statue in Lowden State Park. ◆ More than half a century later, the Etnyre family bought that last buggy from a farm equipment dealer in Indiana and painstakingly restored it. The car

made several appearances in local parades and antique auto shows. Don Etnyre, a great-grandson of E. D.’s who worked at the company for decades, drove it several times.

“It was fun,” he says, “but it was overheating all the time.”

◆ Today the buggy is displayed in the company’s lobby alongside early road oilers and flushers—a picturesque tribute to the road not taken.

a siphon hose, valve, and float, not unlike a modern toilet. When a hog drank enough water, the float would lower, the valve would open, and water would flow from a larger tank into the trough until the float rose again and shut off the supply.

This was the eureka moment depicted by those dummy hogs in the atrium of

E. D. Etnyre & Company’s offices.

Word spread about the labor-saving device, and Etnyre was soon making and selling them to farmers in the area. The automatic waterers led to what modern companies would later call a product extension. Etnyre began building rolling water tanks to service the steam-driven threshers farmers then used to harvest their grain. The first tanks were wooden, but eventually they were made from steel. “THRESHERMEN,” said an 1896 Etnyre ad, “do not spend time with an inferior tank. Get the best tank made which is the ‘ideal.’ It costs no more than the cheaper kind.”

Before long, the tanks led to another product extension: horse-drawn sprinklers that sprayed water on dirt roads to keep down the dust.

“Wasn’t long before people began thinking about oil to settle the dust instead of water,” R. D. Etnyre explained in that 1973 radio interview. Oil did a better job of maintaining dirt roads because it didn’t evaporate like water. So, Etnyre rigged sprinklers to spray oil, and the business grew.

E. D. Etnyre & Company opened shop in 1898 in an old battery factory on the banks of the Rock River. A few years later, it moved to larger quarters at the intersection of Jefferson and Second Streets. In the 1900 census, Etnyre described his occupation as a maker of sprinklers. He was soon to make so much more.

The birth of E. D. Etnyre & Company played out against a crucial period in the evolution of American transportation. In 1898, almost all roads and streets in the United States were dirt. Steamships and railroads had dominated transportation development during the nineteenth century and little attention was given to public thoroughfares outside cities, where a limited number of streets were surfaced in bricks, cobblestones, or other materials.

That started to change during the 1880s and ‘90s when several factors converged to produce a demand for better roads.

First, a bicycle craze swept the country. Everyone has heard the tune “Daisy Bell” (better known for its subtitle, “Bicycle Built for Two”)—one of the big sheet-music hits of 1892, it jauntily captures the popular fancy for two-wheelers. As strange as it seems today, bicycles, not cars, drove the early groundswell for improved roads. In fact, it was the League of American Wheelman, a bicycle advocacy group, that organized the first Good Roads Movement.

Second, Congress passed the Rural Free Delivery (RFD) Act, guaranteeing mail delivery to everyone in the vast American countryside. Until this measure, rural residents usually picked up their mail

continued on page 10

The biggest sightseeing attraction in Oregon, Illinois, is The Eternal Indian, a forty-eight-foot-high concrete statue that looks over the Rock River from a bluff in Lowden State Park. Naturally, Etnyre has a connection to it. The sculptor, Lorado Taft, established an artist colony outside Oregon in 1898, the same year the Etnyre company opened for business, and he befriended E. D. Etnyre. ◆ Taft conceived the statue as a tribute to the spirit of the tribes who had once held dominion over the land. But there was a problem in executing his massive work: It used so much concrete that curing it properly posed a challenge. The monument builders turned to Taft’s engineering-minded friend, and Etnyre devised a heating system to speed drying of the concrete from inside the statue. ◆ The Eternal Indian was dedicated in 1911 and became known over the years as Black Hawk, for the Sauk Native American chief who had fought against the takeover of his tribal lands. In 2018, E. D. Etnyre & Company donated $100,000 to restore the monument, which was cracking and generally showing its age. Today, the statue looks as smooth and sleek as it did more than a century ago.

The pre-dawn rush of water from an Etnyre flusher was one of the most familiar sights and sounds on municipal streets during the mid-twentieth century. The company still makes flushers for other uses, but most local governments have transitioned to the use of street-sweeping machinery.

He progressed to building more powerful roadsters that he must have thought would become the cornerstone of his company. Why else, in the 1910 census, would he have described his principal occupation as “president, automobile factory”?

continued from page 7

infrequently in the nearest town. As RFD was enacted during the early years of the twentieth century, the US Post Office Department joined the push for better roads so it could carry out its federally mandated mission.

Third, farmers across America began to demand better roads so they could deliver their crops to wider markets, giving them an alternative to shipping by rail, which could be expensive (as monopolies are wont to be). The farm-to-market road movement joined the cause.

The final factor was the most decisive: the coming of the automobile. The first commercial car in the United States, the Duryea, appeared in 1895 and ushered in a technological boom that saw scores of small independent companies making different versions of horseless carriages. After the turn of the century, Etnyre became one of them.

Sometime between 1903 and 1906, around the time Henry Ford was launching his Model A in Detroit, E. D. Etnyre made several “gas buggies” in Oregon. He progressed to building more powerful roadsters that he must have thought would become the cornerstone of his company. Why else, in the 1910 census, would he have described his principal occupation as “president, automobile factory”? He even had an impressivelooking illustration of that factory drawn up.

The same year he gave the census-taker that information, Etnyre took some friends

out for a drive in one of his prototypes, a touring car capable of going a mile a minute. The passenger compartment was a work-in-progress, so he installed ropes for the gentlemen to steady themselves with and instructed them to hold on tightly in case the car hit a rough spot in the road.

It did. When the car hit a bad patch, one of the back-seat passengers, who had stood up to speak with Etnyre in the front, was thrown from the vehicle to the ground. He suffered a broken hip and a gash over an eye. “This is the first really serious automobile accident that has come to any of our citizens,” the local newspaper reported. The accident probably played no part in Etnyre’s decision to exit automobile manufacturing. Scores of companies tried to make cars in those years and quickly faded as the industry consolidated. But that rough

spot in the road does seem significant in hindsight. Even as cars began to proliferate in the early 1900s, almost all roads in the United States remained dirt or gravel. American mobility was still at the mercy of mud and dust. For Etnyre, the future was not in making automobiles, but in building and maintaining the surfaces those automobiles would drive on.

Oregon in the early twentieth century was becoming a hub of industry because of its location on the Rock River and on a main east-west rail line. The town of 2,000 boasted a flour mill, a furniture factory, an oatmeal mill, a piano factory, a grain elevator, a foundry—and the Etnyre works. During those years, Etnyre improved

and modernized its early sprinklers, adapting them for water and oil. Initially the pump was driven by a chain and sprocket attached to the axle of a wagon. Later it was powered by a gas engine that could be hitched to or mounted on a motorized vehicle.

The company also developed a street flusher that could clear roads of dirt, trash, and horse manure, shooting water out at fifty pounds per square inch of pressure.

Next, Etnyre designed bituminous distributors, which sprayed oil, asphalt, or tar evenly across a road’s surface to help seal and pave it. As the world clamored for more

paved roads, bituminous distributors were clearly a key to the company’s long-term prospects. The machinery required considerable technical work to perfect, including a burner system to keep the asphalt hot so it could be pumped and sprayed through nozzles.

Etnyre began by selling its machinery through a distributor in Chicago, but as its product line grew and gained a wider reputation, the company set up its own sales operation. E. D. Etnyre was often the chief rainmaker.

His pitches were aimed at the technical-minded people who bought road

A gathering of the Etnyre family at 510 N. Sixth Street in Oregon, Illinois, circa 1928: (standing L to R) George M. Etnyre, June (Strickler) Etnyre, Horace H. Etnyre, Gladys (Bain) Etnyre, Harriet (Smith) Etnyre, Eloise (Robbins) Etnyre (pregnant with Roger), Robert D. Etnyre, Edward D. Etnyre, Edward A. Etnyre; (seated L to R) William E. Etnyre, Joan L. Etnyre, and Robert E. Etnyre.

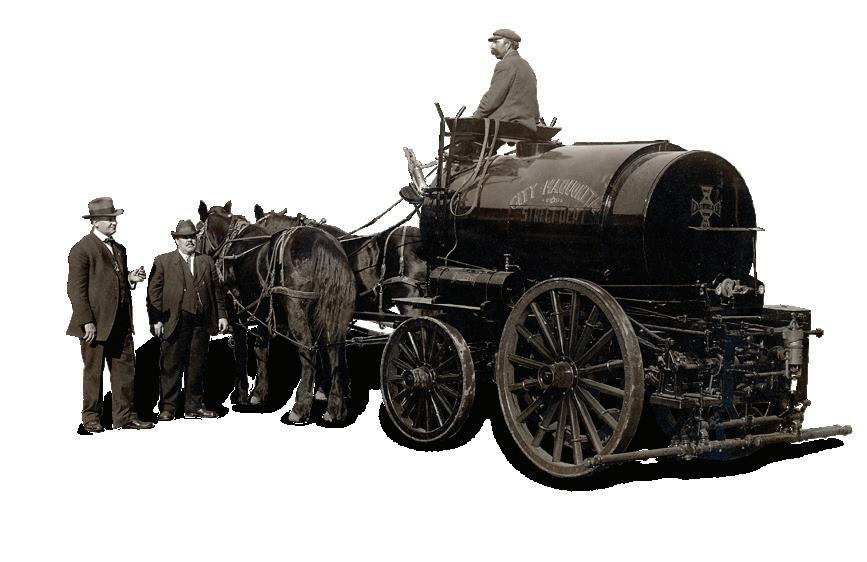

equipment for municipalities. His 1912 letter to the board of public works in Holyoke, Massachusetts—sent on ornate letterhead depicting Etnyre’s original horse-drawn sprinkler—reads like a mechanical drawing in prose. “The Flushing Device,” he wrote, “consists of a powerful centrifugal pump 18 inches in diameter, and mounted immediately under the rear of the tank, the flushing nozzles projecting under the rear wheels close to the street surface.”

In 1916, Etnyre landed one of its largest contracts to date as the US government ordered thirty sprinklers to be used on roads along its southern border. Mexican revolutionaries led by the notorious Pancho Villa had attacked American border towns, and the US Army responded in force. The stakes were particularly high because the US found evidence that German agents were trying to enlist Mexican guerrillas as their allies in the Great War that was then raging in Europe.

The Oregon newspaper sidestepped the international intrigue and lauded Etnyre for bringing credit to its hometown. “The Etnyre product has a trademark that is known all over the world, thereby adding another page to Oregon’s publicity every time a street sprinkler, flusher, or oiler goes out.”

The attention only grew after the United States entered the war against Germany in 1917. Etnyre machinery was shipped overseas to help the US military as it mobilized in the last two years of the conflict.

The Etnyre trademark—a handsome old script in the style of Ford and Coca-Cola’s famous logos—was just beginning its world tour.

CHAPTER TWO

The years after the Great War were the first golden age for American road building. With its growing line of sprinklers, oilers, and bituminous distributors, E. D. Etnyre & Company was well positioned to take part in the highway boom of the Roaring Twenties.

At the beginning of the decade, public roads in the United States were still overwhelmingly unpaved; less than 1 percent of the nation’s 3 million miles of highways were hard-surfaced. But that changed as automobiles spread through the land.

There were about 9.2 million private cars and motorized commercial vehicles in the United States at the dawn of the 1920s. By the decade’s end, the number had tripled and new uses for the internal combustion engine, such as school buses and interstate bus lines, made their appearance. The demand for better roads intensified with the increasing number of vehicles.

Congress passed the first federal aid act for highway construction in 1916 and followed up with much larger appropriations during the 1920s, along with an excise

tax on gasoline to pay for it. But the job of improving American roads was so monumental that government expenditures took many years to catch up with the need.

In the meantime, many of the pioneering long-haul roads were built by private capital and local promoters who marketed their routes as if they were rail lines from the previous century. Some of the roads had colorful names: the Dixie Highway from Michigan to Miami; the Yellowstone Trail from Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts, to Washington State’s Puget Sound; the Old Spanish Trail from St. Augustine, Florida, to San Diego. The best-known route, the Lincoln Highway, passed through Dixon, Illinois, sixteen miles south of Oregon (at about the same time that future President Ronald Reagan was growing up there), on its journey from Times Square in New York City to the Pacific Ocean in San Francisco.

Once lawmakers established the US highway system in 1926, those named roads faded away and became part of America’s early highway lore. Their quaint signposts and directional markers were

Satisfied

replaced by the standardized shield signs we know today.

Throughout this era, Etnyre tinkered with its road machinery to improve it. In the late 1920s, the company introduced a new asphalt distributor, the Model F, which had a wider spray applicator that could pave an entire two-lane road in one pass. Earlier distributors could only cover one side of the road, meaning the machine had to make two passes and could leave an “objectionable center lap,” as one Etnyre sales booklet from the time put it. The booklet also lauded the other attributes of the distributor, like an invisible overflow pipe, kerosene burners to keep the bituminous product hot and liquid, and specially designed spray bars that promised “no slobbering at start or finish.”

The Model F became the industry gold standard for early road work.

During the 1920s, E. D. Etnyre began to step back from managing the company and spent more time overseeing his farms around Oregon, Illinois. He paid particular attention to his cattle, a throwback to his days as a farmer during the 1880s and ‘90s. For decades, the Etnyre family was known for its Herefords along with its road equipment. His offspring took a greater role in factory operations.

E. D. and Harriet Etnyre had six children—five sons and a daughter—and all of them worked at the company or served on its board. Three of their sons took leadership roles: George, R. D., and Horace

E. D. and Harriet Etnyre had six children—five sons and a daughter—and all of them worked at the company or served on its board.

Asphalt is the lifeblood of Etnyre. The oil byproduct that makes most modern road work possible began its life millions of years ago in the prehistoric seas that covered much of the Earth. Algae, plants, and animal life died, decomposed, and compacted under high pressure over the eons, transforming into crude oil locked in strata of rock. ◆

When that crude oil is extracted and refined to make gasoline and diesel fuel, a thick, gooey hydrocarbon called bitumen is left over. Bitumen is the key ingredient in asphalt—the road-paving material that results when aggregate, such as crushed rock, sand, and gravel, is mixed into bitumen. ◆ The bitumen that ends up on American roads is shipped from oil refineries around the US and abroad. It’s processed into asphalt at plants around the country that produce different types with various consistencies and components, suited for different kinds of roads and environments. ◆

That’s where Etnyre enters the picture. Etnyre transport tankers collect asphalt from central sites and deliver it to

highways, airports, parking lots, suburban subdivisions, rural farm roads, and countless other locations in need of paving or repair. Tankers might hit the road in the middle of the night to collect hot asphalt—350oF or hotter—so it is ready at a job site at dawn or before. ◆ An Etnyre tanker often will deliver the asphalt to an Etnyre distributor ready to spread the asphalt. For chipped roads, the distributor first lays down an application of liquid asphalt, then an Etnyre chip spreader follows, spraying out its blanket of gravel. As board member and E. D.’s great-grandson Don Etnyre says, “You’re basically gluing those stones to the road.” ◆ Etnyre’s low-boy and live-bottom trailers might also be part of the picture; a Blackhawk low-boy could have hauled the chip spreader to the job site, and a live-bottom may have delivered gravel or other aggregate. ◆ Later on, when cracks open in the asphalt, crews may arrive with Etnyre crack sealers, using hoses to channel sealant directly into the fissures. Without asphalt, none of it would be possible.

(known as Olie—rhymes with “holy”). Their other two sons, Lee and Eddie, spent less time at the company and went off to other careers. Their daughter, Harriet, was a board member—unusual for the time— and her mother may have also been on the board, although the record isn’t clear on that.

By all accounts, the Etnyre brothers were a boisterous bunch who could be loud and argumentative. Stories of them chasing each other around the factory floor when they were young, occasionally brandishing a ball-peen hammer, have been passed down for generations in the family. According to one tale, a brother had welded a tanker shut with another brother trapped inside.

They all contributed to the company, however—from showing up at 4:00 a.m. to shovel the coal that heated the factory for the early-morning shift to later refining Etnyre’s product line and eventually running the operation.

In March 1933, the children lost their father. E. D. Etnyre died after falling out of a window at his home in Oregon, cracking his skull. He had suffered a series of heart attacks and may have fallen because of another one. He spent his last day touring his farms and meeting with family members, active to the end. He was seventy-three.

“The sudden passing of Edward D. Etnyre early last Friday morning at his home on North Sixth Street came as a grave shock to this community where he had spent his entire life and where he had built from a humble beginning an industry that attained an international reputation,” the Ogle County Republican wrote. “Etnyre road building equipment and street sprinklers are in use in nearly every state in the Union and a number of foreign countries.”

Now it was the next generation’s turn to build on what E. D. Etnyre had established.

After E. D.’s death, his oldest son, George, became general manager of the company, with his brothers R. D. and Olie working as his lieutenants. George was a tinkerer like his father. Under his leadership, the company developed many important advances in bituminous distributors, one being the Fifth Wheel Bitumeter. It had a shut-off nozzle on the spray bar that allowed drivers to control the application of asphalt from the cab of

Many Etnyre inventions through the years were successful (and some were not). This farm fence gate, called the E-Z-Tite, was designed to open and close effortlessly, demonstrated here by Mary Ann Driver (Ploch), the daughter of Harriet “Honey” Etnyre Driver.

the truck, eliminating the need for a separate operator at the back of the Fifth Wheel greatly improved the ability of distributors to accurately control the application of liquid asphalt onto the road surface.

Unfortunately, George and the next generation took over management of the company at the worst possible time. It was the third full year of the Great Depression, and demand for road equipment had dried up because tax revenues had plummeted, along with employment. During the depth of the crisis, the Etnyre factory was shut down for days at a time.

“I can remember my dad being home, no work,” wrote Roger Etnyre, R. D.’s son and later the company’s board chair. “When there was an order, people were rounded up and they worked day and night to get the unit finished. I can remember going to the shop in the evening with my mother and a basket of fried chicken for the men.”

But those orders didn’t occur as regularly as they had during the 1920s. America’s road-improvement project

caught its breath because of a lack of resources.

Still, Etnyre persevered. In the 1930s, the company established a branch office in Boston to handle its business on the East Coast. In 1936, E. D.’s nephew, Samuel R. Etnyre, joined the company as an engineer. His father, a civil engineer who was E. D.’s brother, was an original co-owner of the company but sold his shares to E. D. when times were hard. Business gradually picked up as the ‘30s wore on. A photo from 1935 shows an Etnyre distributor spraying the driveway on the estate of former Illinois Governor Frank O. Lowden, an Oregon resident.

A company report written on Etnyre’s fortieth anniversary in 1938 projected an optimistic future, if only because of the substandard state of most American highways. “Less than 10 percent of the 3,000,000 miles of roads in the United States are improved,” it said, “so the potential seems great.”

Furthermore, a large number of semipaved, gravel roads were going to need reconstruction. “A large section of the 279,238

Etnyre had already developed machinery to distribute road oils and asphalt on surfaces, but this model, improved for the road-building boom of the 1920s, set the standard by allowing operators to pave an entire two-lane width in one pass.

One night George Etnyre awoke in the predawn hours and sketched out a plan on the back of an envelope to reconfigure the factory floor.

miles of Gravel Road, comprising much of the National and State Highways Mileage, will be converted into the more permanent, heavy traffic Bituminous Type Road,” the report predicted. “The Etnyre Model F Distributor, therefore, offers you a means of building and increasing your volume of profitable business for many years to come.”

But before many of those roads could be paved, events elsewhere intervened.

Three years after that report, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II against the Axis powers. Many American manufacturers had to retool their factories to support the war effort; Ford and General Motors went from producing passenger cars and trucks to tanks, ammunition, and military vehicles, while US Steel turned out tons of metal for ships and aircraft.

Etnyre had to reconfigure its plant as well, but in a different way. Its asphalt distributors were crucial for improving airfields and supply roads as Allied troops advanced against the enemy. The military needed all the road-paving equipment it could get, so Etnyre had to figure out how to increase production dramatically.

Solving the problem fell to George Etnyre. One night he awoke in the predawn hours and sketched out a plan on the back of an envelope to reconfigure the factory floor. The company followed his scribbled design and made good on its military contracts. In June 1944, two weeks after D-Day, E. D. Etnyre & Company was presented with the Army-Navy “E” Award for outstanding production contributions

This early sanitary street flusher, used by municipalities to clean streets, was particularly useful when horses were still a common mode of transportation.

to the war effort. The award was created to recognize extraordinary measures by private businesses to support mobilization. Only 5 percent of the more than 85,000

companies involved in producing materials for the US military during World War II received the recognition, so it was a high honor indeed.

Like Hershey bars and Coca-Cola bottles, Etnyre asphalt distributors followed the flag as US troops deployed around the world.

“Many an Oregon boy in military service later told how he felt close to home, though half a world away, when he saw an Etnyre oiler being used on an airport runway,” wrote the Evening Telegraph newspaper in nearby Dixon. Etnyre equipment was especially critical during the 1943 Allied invasion of Italy.

“We could hardly get material for anything else,” R. D. Etnyre said later in an oral history. “Steel was rationed. But the Army could get it. Our [distributor] tanks were sent all over . . . Iran, Turkey, South Africa, Indonesia, Norway, Australia.”

Many Etnyre factory hands served in World War II. On Dec. 7, 1943—two years to the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor— the company sent a joint letter to nineteen

of them, addressed “Dear Boys.” It was part of a care package that included playing cards, $5 money orders, subscriptions to Reader’s Digest—and news that they would all be receiving a pay bonus.

“If you were back in the old hometown today, you would find that Winter is settling in,” the letter said. “The beautiful coloring of Fall is gone, and colder weather is coming. The folks back home hope and pray that the war may soon end in complete victory so that all of you can be back home once again.”

It concluded: “We want you to know that we are ‘with you’ in thought and prayer. You are an Oregon boy. You are one of us here at Etnyre’s.”

Few things in the company archives better express Etnyre’s familial regard for

continued on page 30

For much of the twentieth century, Etnyre’s most familiar products were the truck-mounted asphalt distributors that paved roads and the flushers that sprayed water to clean streets in towns across the country. They were so central to Etnyre’s identity that for many years the company newsletter was called The Black-Topper (complete with a black top hat in the nameplate) and the company’s bowling teams during the 1950s were christened the Black-Toppers and the Flushers (which must have raised a few chuckles).

◆ The call for flushers has declined as environmental concerns about road runoff have led localities to find other methods to clean their streets, usually street sweepers. But asphalt distributors are still a crucial part of Etnyre’s business and sense of identity. They’re still called blacktoppers; in fact, they’re actually Black-Toppers—capital B, capital T—a registered trademark.

The adaptation of a hydraulic drive system in place of the auxiliary rear engine tied the forward ground speed of the truck directly to the asphalt pump output. The hydraulic drive system increased the accuracy of the asphalt application rates and required less maintenance.

After the war, pent-up demand dating back to before the Great Depression produced the largest roadbuilding expansion to date. The nation’s road system still needed a lot of work.

continued from page 27

the people who work there than this letter.

Like other family letters, this one also shared some bad news: One of those Oregon boys would not be coming home.

Robert C. Gantz, a twenty-twoyear-old Oregon native whose draft card listed his occupation as a metal worker at Etnyre, had enlisted in the Army Air Corps a month before Pearl Harbor. He received his wings the following May and became a flight instructor at a base in north Texas. On July 22, 1942, he died there in a plane crash.

“In his memory and in respect,” the letter said, “let us pause in a moment of silent tribute to this truly fine young man who gave his all in this war. Remember ‘Bobby’ Gantz.”

His remains were brought to Oregon’s Riverside Cemetery, where they were laid to rest in the same hilly patch of home that E. D. Etnyre had been committed to less than a decade before.

After the war, pent-up demand dating back to before the Great Depression produced the largest road-building expansion to date. The nation’s road system still needed a lot of work. Of the 3.3 million miles of roads in the US, the Bureau of Public Roads reported that only 23 percent were paved, 35 percent were topped with gravel, and almost 40 percent were still dirt. What’s more, many of the early roads dating back to the 1920s needed rebuilding because their surfaces had degraded, or they required safety

Details are sparse, but family lore has it that E. D. Etnyre’s other sons decided George was too bossy and difficult to deal with, so they voted him out as general manager.

upgrades to eliminate dangerous curves and perilously steep grades. Etnyre’s road equipment was needed more than ever.

But the company faced this new era of opportunity under new leadership. Details are sparse, but family lore has it that E. D. Etnyre’s other sons decided George was too bossy and difficult to deal with, so they voted him out as general manager. While he no longer was involved in the company’s management, he remained on retainer as a consultant and served on the board of directors until his death in 1968. Always engaged in the family’s farming enterprise, which had grown to 2,000 acres, he stepped up his oversight of its registered Hereford operations, which he owned with R. D. and Olie. Ever the tinkerer, he also continued to invent things and was awarded several patents for devices like a remote-entry system for the automobile.

The job of guiding the company fell largely to his brothers R. D. and Olie. With the post-war expansion of the American road system kicking into gear, the future looked promising for the next generation of Etnyres and the family business as it entered its second half-century.

CHAPTER THREE CHAPTER THREE

Etnyre road equipment was needed more than ever during the years after World War II. The era saw unprecedented road development as the United States built out the original federal highway system and launched an ambitious network of limitedaccess superhighways—the interstates.

There had been stirrings of the seventymiles-per-hour future before the war. A few cities and states began constructing freeways and turnpikes during the 1930s, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed a system of control-access highways during the late part of the decade. Then the attack on Pearl Harbor stopped everything in its tracks.

It was left to one of the heroes of the war, Dwight D. Eisenhower, to actually start building the interstates after he became president during the 1950s. He had seen the need personally. As a young army officer after the end of the first world war, he had served as a military observer during

the First Transcontinental Motor Convoy, in 1919. Eighty-one vehicles took sixty-two days to travel 3,251 miles from Washington, DC, to San Francisco. He saw firsthand how bad US roads were, how poor conditions and frequent breakdowns could paralyze a fighting force. The roads, he observed in a report, “varied from average to nonexistent.”

As the Allied Supreme Commander in Europe during World War II, Eisenhower knew that the German autobahns were some of the most advanced highways in the world. The contrast with American roads couldn’t have been more stark. During his first term as president, Congress passed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, and the United States began construction of the interstates. It was arguably the largest public works project in American history, costing more than $100 billion, lasting for decades, and profoundly transforming the landscape. Work on the interstates—their spurs, loops, and additional lanes—not to

mention incessant resurfacing—has never really stopped.

So, the post-war years were a glorious time for road builders. Etnyre met the challenge with a series of innovations that revolutionized the company’s model line:

◆ 1951 Etnyre introduced a number of advancements, increasing the efficiency and productivity of its distributors.

◆ 1959 The company unveiled its first constant-spray bar-height control for asphalt distributors, boosting accuracy by maintaining the bar at a proper height above the road.

◆ 1962 Etnyre developed the first hydrostatic distributor, linking the forward ground speed of the truck to the asphalt pump output, vastly improving the accuracy and control of the spray application. Until hydrostatic systems, asphalt distributors required two people: a driver in the front and a spray operator in the rear, standing on a platform or, in earlier times, sitting over the roadbed in a tractor seat.

◆ 1963 The company rolled out a self-propelled chip-spreading machine—the ChipSpreader—which distributed a carefully controlled amount of aggregate to the roadbed. It replaced tailgate spreaders and improved application control, productivity, and safety.

The combination of the ChipSpreader and the single-control, hydrostatic asphalt distributor greatly simplified the process of road construction and repair and represented the most significant advance in surface-treating equipment in many years.

To produce the new machinery, Etnyre expanded its Oregon, Illinois, facilities. In 1956, it built a new fabrication plant for transport tanks on the east side of the Rock River on South Daysville Road. In the coming years, more and more of its operations would shift to the new property, and eventually, during the 1980s, the company

The Etnyre Transport Tanker (1950s)

Most of Etnyre’s business revolves around the movement and application of asphalt. The company has made tankers to transport asphalt since the early 1900s, making sure the gooey substance stays hot and mobile. Its tankers were constantly upgraded, but they underwent a rigorous redesign in 1995 to meet new federal standards for transporting flammable and hot products, all while remaining lightweight enough to be practical.

continued from page 37

would donate its old plant at Jefferson and Second Streets to Ogle County. The last remaining building, which had housed the coroner’s office and sheriff’s department, was torn down several years ago.

While its product offerings multiplied, Etnyre’s core business during the postwar years remained its asphalt distributors. They were known the world over.

As a company brochure put it: “Today there are more Etnyre Black-Topper Bituminous Distributors in use than any other kind. In every state of the USA, in Mexico, Africa, Asia, Central and South America, Canada, Cuba, Europe, Australia, and oth-

er parts of the world, Etnyre Black-Toppers are helping build better bituminous roads at lower cost.”

With business going so well, the company turned its attention to acquisitions. For the most part, it targeted firms that dealt in asphalt. It seemed like a sensible strategy, considering how central asphalt is to Etnyre’s business.

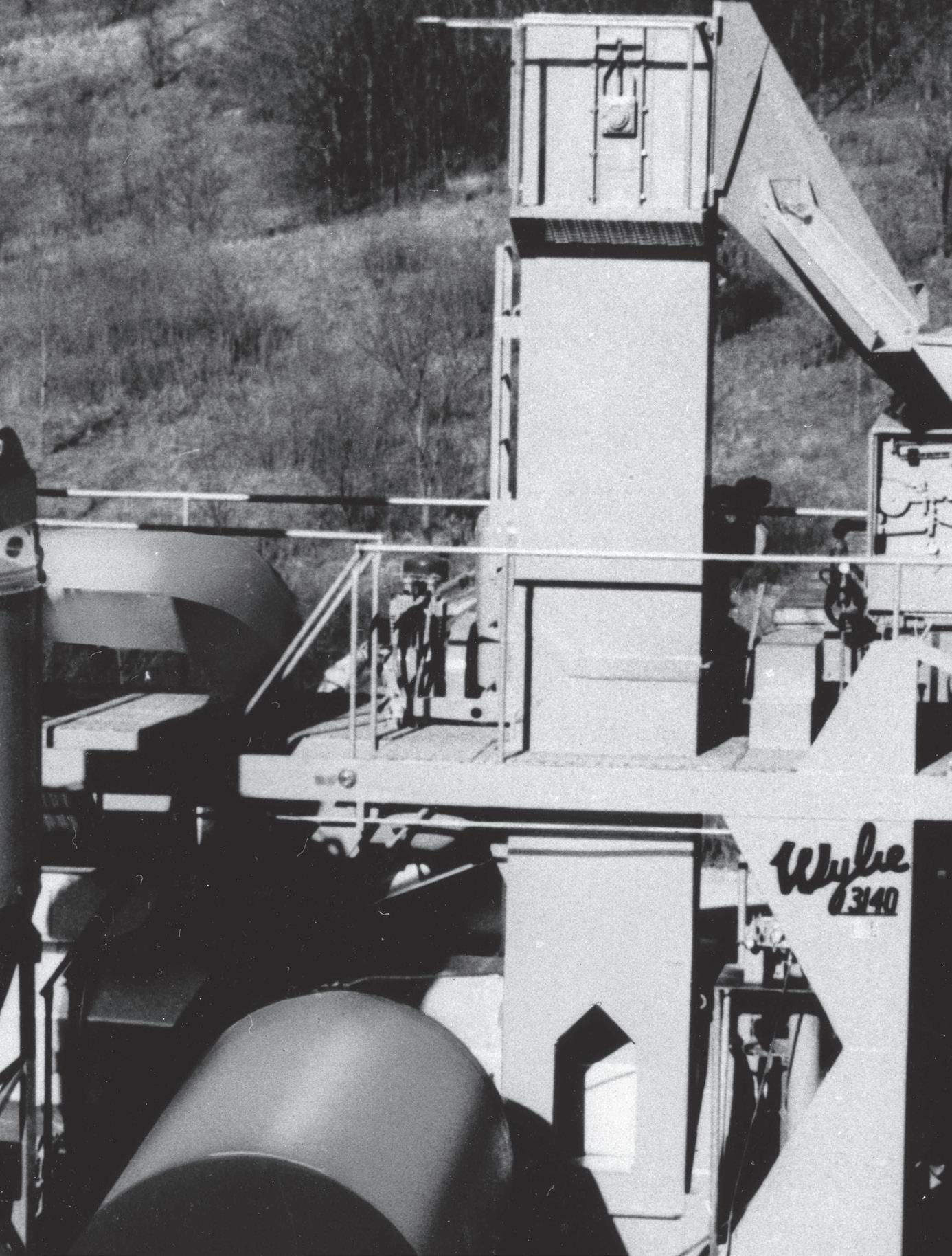

In 1965, Etnyre bought the Wylie Corporation in Oklahoma City, which made portable “batch mix” asphalt plants

continued on page 45

Etnyre wagon sprinklers and road oilers first appeared outside the United States during the 1910s, thanks to US military purchases during World War I. Since then, the company has sold equipment and parts in more than one hundred countries around the world on every continent but Antarctica. ◆ One of the most noteworthy early sales came in 1932 when the Soviet Union purchased fifteen bituminous distributors mounted on trucks. “We often wondered why they just ordered fifteen,” Olie Etnyre recounted in a 1973 radio interview. “Apparently, they just copied them and made their own.” So much for intellectual property rights. ◆ International business has always contributed significantly to Etnyre’s sales. In the company’s archives, there sits a cabinet that seems to go on forever, containing file folders labeled with names from Afghanistan to Vietnam, and a few countries that now go by different names. ◆ Given

that much of the world is paved with road systems less developed than in the United States, it would seem to be an area with growth potential. But the sometimes-higher cost of American-made machinery complicates things. ◆

“I think we can really grow that part of the business,” says Board Chair Bill Etnyre, “but it won’t be through selling finished products overseas. With the high costs of shipping, we’re simply too expensive for most international markets. One exception currently is a version of our live-bottom trailer that has been designed to fit into standard cargo containers. And we are already finding new markets and creating partnerships abroad. That’s a growth opportunity.” ◆ CEO Ganesh Iyer predicts that international business will become an increasingly important part of Etnyre’s portfolio.

“We’re going to be more of a global company in the next ten to fifteen years.”

The Etnyre Self-Propelled ChipSpreader (1963)

Chip-sealed roads require fine rock aggregate to be glued to the pavement with one or two layers of asphalt. The self-propelled ChipSpreader replaced tailgate spreaders and advanced the surface-treatment process, improving the production and quality of the work and, most importantly, worker safety.

This completely new design included cab controls, operator enhancements, and automation. The SAM incorporated solid state and eventually microprocessor controls that allowed the operator to change forward ground speed and spray bar widths while maintaining consistent application rates.

continued from page 40

that could produce the paving material at work sites. In 1968, it purchased the TracMachinery Corporation in Nunda, New York, which made specialized asphalt and contour pavers. A decade later, it acquired the design for an asphalt drum mix plant. Drum mix plants were becoming popular and replacing the more traditional batch plants of the day.

Etnyre also bought a small company in Fresno, California, that manufactured custom trailers for agriculture. Renamed Edeco West, it was intended that the firm would make asphalt distributors and transport tanks on the West Coast, where Etnyre had less presence. However, Edeco West struggled to become established and was closed down.

Taken as a whole, these efforts amounted to an extensive expansion for a company that remained relatively small and family-owned.

If anyone worried that the investments might not pan out, they didn’t show it. When Etnyre celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary in 1973, R. D. and Olie Etnyre— the brothers who had helped run the company since World War II—sat down for a radio interview with WRHL in Rochelle, Illinois, along with longtime employee Connie Kolpak. The brothers reminisced about their father’s adventures out West, the company’s beginnings with livestockwatering systems, and the yeoman service the factory performed for the US military during the Big War. In the same interview, Connie joked about Olie’s foghorn voice. “We didn’t need a public address system because you could hear Olie from one end of the shop to the other.”

Current Board Chair Bill Etnyre, who worked in the shop during the ‘60s, agrees with Connie’s assessment and says he has

continued on page 48

The Etnyre Self-Propelled Hydrostatic Drive ChipSpreader (1980s)

This was the first ChipSpreader to utilize a hydrostatic drive system, moving forward from conventional mechanical drive systems. The hydrostatic drive improved operator control and allowed for the eventual adaptation of computer control. A variablewidth model permitted the aggregate hopper to spread up to a maximum width of twentyfour feet, increasing productivity and the quality of the finished result.

R. D. was the cigarsmoking chair of the board who much preferred working at his personal lathe in the shop to sitting in the office.

never forgotten the many times his Great Uncle Olie bellowed: “Howard (or whatever name it was), I need you! Where are you?”

To complete the seventy-fifth anniversary festivities, the local community was invited to tour the Etnyre plant and enjoy a buffet meal as part of Oregon’s Autumn on Parade festival.

The brothers had teamed well in their years at Etnyre.

R. D. was the cigar-smoking chair of the board who much preferred working at his personal lathe in the shop to sitting in the office. Olie served as president and general manager. The anniversary celebration marked the end of the era for E. D. Etnyre’s sons’ work as a management tandem.

To show how business had grown in their years at the company, Connie Kolpak contrasts the size of its workforce. “I began in 1935,” she says, “and the total complement of Etnyre employees was about 35. A vast difference from today, where it is 265. That is a big Etnyre family.”

continued from page 45 continued on page 53

An anniversary brochure published during the seventy-fifth anniversary—The Etnyre Road—made clear how much the company remained a family affair. Six of seven board positions were held by family members, and four of five company officers were named Etnyre. The 1970s marked a turning point for the US road system. Late in the decade, for the first time in American history, the

The Etnyre Live-Bottom Trailer (1990)

Live-bottom trailers serve the same function as dump trucks but use a conveyor belt to offload contents in a more controlled and much safer fashion. Etnyre started from scratch and developed a live-bottom trailer in-house, introducing two innovative features that set it apart from competitors. The first was an over-the-fifth-wheel conveyor design that improved weight distribution, allowing more payload. The second was a unique belt-drive system that was wider and reduced weight and complexity.

majority of the nation’s 4.1 million miles of public roads were finally paved. The job of getting the country’s transportation network out of the dirt and mud was so large that it had taken three-quarters of a century since the advent of the Model A to achieve.

Those years marked a turning point for Etnyre too, as the company transitioned past the second generation of family leadership. Olie Etnyre died in 1977, followed four years later by his brother R. D. Non-family members had been involved in running the company since the late 1940s, but after the brothers’ deaths, they would become increasingly important to the firm’s fortunes. It happens with any family business successful enough to endure so long.

As it happened, those transition years were some of the most difficult ones for Etnyre. Problems started to pop up with some of the new products, especially one of the mobile asphalt-makers: the drum mix plants.

The drum mix process produces lots of dust and usually requires a filtering system to control it and meet environmental regulations. The prototype version Etnyre invested in was designed not to need traditional filters; the technology was supposed to be clean and would filter itself. It worked if optimal conditions were met. But in the real world, the system was temperamental and almost proved disastrous for Etnyre.

“The failure of drum mix to meet environmental standards led to many

As it happened, those transition years were some of the most difficult ones for Etnyre. Problems started to pop up with some of the new products, especially one of the mobile asphalt-makers: the drum mix plants.

The Blackhawk Lowboy Trailer (1995)

Etnyre acquired a lowboy trailer line from Hyster in 1989. A few years later, it introduced a fifty-ton trailer with a removable gooseneck that it christened the Blackhawk. Over the next few years, the whole lowboy line was redesigned and updated. Eventually, all Etnyre trailers carried the Blackhawk name.

“There

were a couple of years when we really had our hands full. I spent a lot of time in the field, mainly in Texas, trying to keep those portable asphalt plants going.”

continued from page 53

lawsuits and nearly drove the company into bankruptcy and the brink of foreclosure,” says Bill Etnyre, one of E. D.’s great-grandsons, writing about the tumultuous period years later when he became board chair.

Don Etnyre, another of E. D.’s great-grandsons and a future board member, began his long career in sales and marketing at the company during this time and remembers what a challenge the asphalt operations could be. “There were a couple of years when we really had our hands full. I spent a lot of time in the field, mainly in Texas, trying to keep those portable asphalt plants going. Bottom line: We bit off more than we could chew, executed poorly, and simply did not fully appreciate the complexity of the process.”

The lawsuits and settlements dragged on the company’s bottom line. Etnyre didn’t make a profit for several years during the late 1980s and early ‘90s. It didn’t help when a short economic recession struck the nation and forced the company to do something it absolutely hated: lay off workers. The move provoked some angry feelings toward the company and the family—which came as a surprise considering how long Etnyre had been seen as a source of local pride. The emotions soon passed, leaving the memory of an experience no one wanted to repeat.

Righting the company’s ship fell to Don’s father, Roger Etnyre, who rose to board chairmanship during the ‘90s, and to a new president and CEO named Dave Abbott. They refocused Etnyre on

its core products—its road-preservation equipment—which remained very popular. The company continued to improve the machinery.

In 1988, Etnyre introduced the industry’s first computerized controls on an asphalt distributor. In 1993, it redesigned microprocessor controls and incorporated them into the newest distributor, the Series 2000 Black-Topper, and reconfigured its chip spreaders and street flushers with the latest technology.

The company also entered a new field: low-boy trailers, buying a low-boy model line from the Hyster Corporation of Oregon in 1989. Low-boy trailers proved to be a smart addition to Etnyre’s playbook. Of all the acquisitions of the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, it was the only one that panned out. Etnyre no longer makes any of the other products.

When the company celebrated its centennial in 1998, Roger Etnyre expressed his gratitude for the company’s members. “People with myriad talents and skills— people with hopes and dreams. Above all, people who dedicated themselves faithfully to holding this company together through the tough times and people who remain determined to continue the success we enjoy today,” he wrote. “We look forward to the coming century with confidence that we will maintain our association with the type of people who will ensure our prosperity.”

Etnyre still had debts, but it was making steady progress toward retiring them. Gradually, painfully, the company put its books in order. At one of its first board meetings in the new millennium, the leadership was able to make a long-waited announcement: We paid off the loans!

CHAPTER FOUR

In the years after Etnyre celebrated its centennial on the brink of the twenty-first century, the business underwent an eventful time of growth and change, despite one of the nation’s sharpest economic downturns in decades. How the company handled that difficult passage revealed much about its culture and the values it strives to live by.

Etnyre began the new millennium on a high note as it landed its largest contract ever to supply mobile water tankers and fuel storage to the US military during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Other big military orders followed. By the time the contracts concluded, Etnyre had built 543 water distributors and 843 palletized fuel tanks for American forces in the Middle East.

Back home, the company’s line of trailers became a more important part of the business—especially live-bottom trailers, with conveyor systems that offload their contents in a more controlled fashion than dump trucks. With no need to raise the bed, a company brochure said, there were “no worries about low wires, trees and bridges— all the things that could snag a dump truck.”

As the business grew during the early 2000s, Etnyre’s presence in Oregon, Illinois, expanded. The company filled its hundredacre campus on South Daysville Road with one structure after another, ringed by big parking lots to hold inventory for customers. Inside, state-of-the-art laser cutters, computerized controls, and robotic welders brought a high-tech edge to the old manufacturing process.

Then came trouble. In 2007, the housing bubble burst, causing a banking crisis, and the United States descended into the Great Recession, the gravest economic crisis since the 1930s. Demand for Etnyre’s products dropped, and layoffs seemed to be unavoidable.

Much of corporate America responded to the sudden reversals by cutting jobs. Not Etnyre.

“We didn’t want to lose our people, and we didn’t want them to lose so many hours that they couldn’t take care of their families,” explains Bill Etnyre, then a board member. Instead of furloughing workers, the company trimmed the number of weekly hours to

Etnyre workers never forgot that their employer, during the worst economic crash of their lifetimes, avoided layoffs.

thirty-six and required its office staff to take a 10 percent pay reduction. Members were put to work on deferred maintenance and building up stocks of parts that would be needed when the economy rebounded.

“These are not the best of times,” company president Tom Brown wrote in an open letter to members in 2009. “But with all things considered, and relative to others less fortunate, we are not doing badly. As a team, we have placed ourselves in an enviable position and by holding that team together, and doing our best, we will minimize the effect of the current downturn.”

The company returned to full operations seven months later and was even able to pay bonuses and contribute to the decades-old profit-sharing program by year end.

Etnyre workers never forgot that their employer, during the worst economic crash of their lifetimes, avoided layoffs. It just confirmed for them that their employer had a heart and a long-term vision that wasn’t tethered to the quarterly earnings reports of a publicly traded company.

“That’s what my brother-in-law told me before I started here thirty-seven years ago: Etnyre is a great place to work because they don’t lay you off and they treat people right,” says Dale Boomgarden, who manages the tank manufacturing line. “The family really cares about the members. You can tell it with our health insurance, which is very good, and the way we have profit-sharing in our 401(k) plans.

“And you could really tell it when the economy was bad. They kept us on payroll, and we did things like build those little

storage buildings you see around here. It probably cost more for us to build them instead of having a contractor come in from outside. But they wanted to keep their people here. They cared.”

In riding out the storm, it helped enormously that the company had retired its debt and was building a cash reserve. When business picked back up after the recession, Etnyre was able to strengthen its position in the industry with several acquisitions. Some of the moves were vigorously debat-

ed among board members, but they have so far worked out much better than the acquisitions of several decades ago.

In 2015, the company bought BearCat Manufacturing, its major competitor in the distributor and chip spreader sector. Like Etnyre, BearCat was a private, family-owned business. It traced its roots to the 1960s in Klamath Falls, Oregon, where one of the founders, Ken Hill, started out driving asphalt distributors, jumping in and out of the cab up to 500 times a day to manually set the width of the spray bar. He started a company that merged with another, and when he was ready to sell, Hill didn’t want

Etnyre has long donated to local charitable causes. In 2018, the company created The Etnyre Foundation to formalize and expand its philanthropic efforts. ◆ The first round of grants in 2019 went to five Oregon-area organizations. The following year, the scope was broadened to causes in the other three communities where Etnyre companies have manufacturing facilities: Minonk, Illinois; Wickenburg, Arizona; and Anderson, South Carolina. Recipients have included public schools, Habitat for Humanity, a hospice care facility, and a blood bank. One grant helped the Arizona Elk Society provide camping equipment for veterans with disabilities. Another helped the Nachusa Grasslands in Illinois acquire animal skins and other supplies for close-up environmental learning. Another went to the Oregon-area Boy Scouts to build a pavilion for merit badge training in all weather. ◆ To date, The Etnyre Foundation has given more than $500,000 to charitable causes. “Etnyre’s success would not be what it is without our communities,” says family member Nicholas Davis, who, along with cousins Melissa Masters and Brooke Etnyre, served as the foundation’s coadministrator for four years. “We need them to thrive so the company can thrive.”

to do business with some venture capital firm; he sought out another family-owned business with similar values: Etnyre.

“I did my best to assure them that we had the deepest respect for BearCat,” says Tom Brown, who negotiated the deal just before retiring from Etnyre. “We really weren’t planning to change anything, we weren’t going to relocate the factory, we weren’t going to change the personnel, we weren’t going to change the product.”

BearCat agreed to terms, and it continues to manufacture distributors, crack sealers, and chip spreaders under its branded name at its plant in Wickenburg, Arizona. Its equipment is well-known in the West, where Etnyre had less market penetration. The combination of the two firms leaves Etnyre as the maker of the vast majority of asphalt distributors and chip spreaders in North America.

In 2017, Etnyre transitioned into a new generation of leadership as its beloved board chair of twenty-five years, Roger Etnyre, died at the age of eightynine. Roger was a hands-on executive who loved the manufacturing process and carried the keys to the factory buildings in his pocket like a janitor at a school. He seemed to know every worker by name—and usually something about their families—because he worked at it. He thought it was important to maintain a human connection to the people who made the company’s products, so he took notes of his conversations as he walked around the factory floor and drove around the campus.

Roger was a hands-on executive who loved the manufacturing process and carried the keys to the factory buildings in his pocket like a janitor at a school.

A completely new design for Etnyre’s flagship asphalt distributor streamlined the product while offering customers the chance to customize individual units to their liking. The S-2000 eventually evolved into the Centennial model with a variablewidth spray bar that could extend to twenty-four feet. Working with the twentyfour-foot variable ChipSpreader, the two pieces of road equipment set standards for the surface-treatment process.

One of the board’s first jobs under its new leadership was to hire a president and CEO. It chose Ganesh Iyer, a rising executive who had been posted in Singapore with Caterpillar.

continued from page 67

“He loved the factory and the people who worked there,” says his son, Don Etnyre. Characteristically, Roger Etnyre was at work on the day before he died.

After Roger’s death, Bill Etnyre, a senior member of the family’s fourth generation since E. D., became board chair. A longtime college professor specializing in social work, he had spent five summers working at the factory as a young man during the ‘60s, earning $1.65 an hour, and remembered the experience fondly, from making jigs to assembling spray bars. His life path had taken him far from Illinois, first with the US Air Force and ultimately with a teaching position at the University of Washington in Seattle.

“I always kept up with the company and tried to attend annual meetings, even when I was hundreds of miles away,” he remembers. “When they asked me to join the board, I took some business courses to get prepared.”

One of the board’s first jobs under its new leadership was to hire a president and CEO. It chose Ganesh Iyer, a rising executive who had been posted in Singapore with Caterpillar, the construction equipment giant. One of the reasons he was attracted to Etnyre was its family ownership and its interest in the well-being of its members. “This family has always been very kind and generous—that’s the secret recipe,” Iyer says. “A lot of companies get hung up on short-term profitability all the time and lose sight of the big picture. If you take care of people, the future will take care of

A BearCat ChipSpreader applies aggregate chips during a surface chip-and-seal process.

itself. Money is the byproduct of doing the right thing.”

Longevity of family companies that are as old as ours depends on having strong engagement from current family members. This can be challenging as the generations become further removed from the early builders of the company. To generate involvement of current family members, Etnyre leadership formed the Family Council in 2019. Since its informal beginnings and now formal organizational structure, many fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-generation family members have attended FC meetings, participated on its board and committees, and organized special events. “It’s exciting to see the enthusiasm from all the generations who want the company to grow and improve lives near and far for many years to come,” says Bill Etnyre, founder of the FC.

Since taking the reins in 2018, Iyer has stressed purpose-driven capitalism. The company has adopted a statement of values, started leadership academies for all its members, and set up Purpose Councils at all its plants to more fully involve all levels of workers in the process. Etnyre has also adopted more stringent safety protocols and taken measures to recruit women for factory leadership roles.

Iyer refers to this way of thinking as optimizing profits instead of merely maximizing them. Much of his philosophy isn’t that different from what Etnyre has always done in regard to its workforce, but the new emphasis represents a more intentional way of setting goals and focusing on all the company’s stakeholders: its members, customers, suppliers, and communities.

As Iyer sees it, Etnyre occupies a valuable niche in the road industry. Its equipment is geared more toward pavement preservation than construction, which helps explain why much larger corporations like Caterpillar or Komatsu, which specialize in bigger road construction machinery, have not swept in as competitors.

In the past six years, Etnyre has significantly diversified its business portfolio by acquiring SMF and Hendrick— metal-fabricating companies serving a wide range of customers in the areas of electric power, mining, commercial buildings, industrial water intake, and mineral screening. Etnyre also purchased Rayner Equipment Systems (RES) a California business that makes machinery for asphalt pavement maintenance. The new companies retained their trade names

and were grouped under the corporate umbrella Etnyre International.

With revenues from BearCat and these recent acquisitions, Etnyre has seen its revenues double and profits grow nicely in the past six years. Iyer envisions the company more than doubling in size again by 2030 due to new markets and the persistent requirements of old ones.

The need for road work never ends. Even today, almost 130 years after the first horseless carriages puttered down dirt roads in the United States, only about twothirds of America’s 4.1 million miles of public roads are paved, according to the Federal Highway Administration. And the ones that have been paved never stop requiring

maintenance and repairs—which plays to Etnyre’s strength.

The market, it seems, stretches to the horizon.

On a brisk winter morning, Don Etnyre, now retired from sales but still a board member, walks a visitor through the manufacturing process at the main facility on South Daysville Road. As he passes from building to building, he greets one worker after another, many by name. He’s definitely the son of Roger Etnyre, the longtime chair.

The Etnyre facilities do not look like a factory as many Americans

might imagine it. The common image of a factory most closely resembles an automobile-assembly plant, with a main building that seems to go on forever and a central conveyor line where everything comes together.

Etnyre has no Grand Central Assembly Building. Its campus is occupied by some eighteen structures that vary greatly in size and function. It all grew organically, building by building, over half a century as the company’s product line and process evolved. The end result: a collection of interwoven shops where skilled workers make intricate modifications to every piece of ordered equipment.

“Everything we do here is custom-built,” Don Etnyre explains over the hum of the shop. “We don’t usually make fifteen of something. Everything is tailored to the customer’s specifications.”

He pointed to an asphalt distributor truck nearing final assembly, looking shinier than it ever will again after it’s put into road service. “This one is going to the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. It has thousands of parts. By the time it’s fully equipped, you’re probably looking at $200,000 of road machinery there.”

The manufacturing process starts when raw materials such as sheet metal, bar metal, or steel beams arrive at the plant. A never-completed railroad spur still runs onto the property, but it was outdated even when it was built and has never been used. Everything is trucked in and then driven out by customers.

Don Etnyre demonstrates the process with one of the company’s most enduring

“Everything we do here is custom-built,” Don Etnyre explains over the hum of the shop. “We don’t usually make fifteen of something. Everything is tailored to the customer’s specifications.”

products: asphalt tanks, used on distributors and transports. There’s a clear and logical fabrication and assembly process here, but it doesn’t run along a linear assembly line.

Tanks go to several different buildings as aluminum sheets are cut, bent, joined, welded, and riveted, a process that involves robotics and good, old-fashioned manual labor. When a craftsman disappears inside the curving walls of a tank, its end opened like the mouth of a whale, an eerie blue light fills the inside as an arc welder sparks to life. It’s rather beautiful to watch.

“That’s hot, hard work there,” Etnyre says.

Once the tanks are formed, they’re taken to another building to be sand-blasted and primed, and another to be sealed. Then they’re ferried to a final building where they’re mounted onto trucks and customized. Forklifts carry the tanks from each step to the next, accounting for the constant traffic darting around the Etnyre campus.

“We make things here,” Etnyre concludes. “This is hard-core manufacturing from the bottom up.”

It has been that way since 1898. That hog watering trough in the atrium of the Etnyre office building? It wasn’t purchased

from some agricultural supply house. It was fashioned on site, just like the company’s tankers and distributors.

“I made that,” said David Bolhous, who now works in parts sales but started out doing various jobs on the factory floor during the late 1970s. “Roger Etnyre asked me to work on that old horse-drawn oiler you see out there, get it working again, and then he asked me to make that trough. So, I fabricated it from sheet metal.”

In true Etnyre fashion.

E. D. Etnyre & Company reveres its history. Any visitor to the head office walks past E. D. Etnyre’s roll-top desk in the main lobby. Just beyond the reception area is that atrium display of vintage road equipment. And many customers and newly hired staff attend training and orientation sessions in the Roger Lee Etnyre Training Center, which was named for the late board chair but also functions as a place to remember his father, R. D. Etnyre. In his later years, R. D. liked to work on a lathe as he did during his youth. On his seventy-fifth birthday, the company had the lathe painted gold; it’s now displayed prominently in the training center as a tribute.

Taken together, these nods to the company’s past memorialize three generations of Etnyre stewardship. The question is—how much longer can that lineage continue?

More than a century and a quarter after its founding, Etnyre employs more than 1,100 people at seven facilities in five states. Three family members currently hold seats on the board, one serves as corporate secretary and another family member is actively working in the business. Several other fifth-generation

family members and a sixth-generation family member have worked at Etnyre fulltime or during the summer months.

But employment of family members is harder to swing now that so many family members have spread across the country and no longer live near Oregon.

“I’d like to see more Etnyres working here, and I’ve tried to make that happen,” says Bill Etnyre, who has reached out to far-flung kin across the country and instituted a Family Council that meets virtually.

“I think more family members are expressing an interest now. Even if they don’t work here, there are other ways to take an interest and be involved.”

However they’ve been involved, Etnyre has been well served by the many family members who have helped run and manage the company over the years. At Etnyre, family—in all the senses of the word—has always meant so much.

As Bill Etnyre says, “I’d like to see this family business last another 125 years.”

Etnyre’s Centennial Black-Topper distributor applies tack coat on an asphalt paving project.