growing food making energy living fully treading lightly

growing food making energy living fully treading lightly

At Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, we believe a healthy Island starts with a healthy environment.

Martha’s Vineyard Hospital is committed to keeping the hospital clean and sanitized to create a healthy environment for patients and staff. Understanding that some cleaning products include chemicals that are harmful to the environment, the hospital switched to using Ecolab products in the Fall of 2022, a cleaning product that that provides infection protection while also protecting our precious environmental resources. We’re proud to be working with cleaning products that put health, safety and sustainability at the forefront for our patients and our employees.

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. On it everyone you love .” –Carl Sagan

President Victoria Riskin

CEO Raymond Pearce

Editors Brittany Bowker, Jamie Kageleiry, editor@bluedotliving.com

Senior Writer Leslie Garrett

Chief Financial Officer David Smith

Associate Editors Lucas Thors, Julia Cooper

Editorial Assistant Emily Cain

Copyeditor Laura Roosevelt

Creative Director Tara Kenny

Designer/Production Manager Whitney Multari

Design and Production Vesna M. Nepomuceno

Digital Projects Manager Kelsey Perrett

Digital Assets Manager Alison Mead

Web Producer Grace Hughes

Contributors this Issue Randi Baird, Geraldine Brookes, Doug Cooper, Hermine Hull, Sheny Leon, Sam Moore

Ad Sales Josh Katz, adsales@bluedotliiving.com

Consumer Marketing Laurie Truitt

•

Bluedot and Bluedot Living logos and wordmarks are trademarks of Bluedot, Inc.

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved.

Bluedot Living: At Home on Earth is printed on recycled material, using soy-based ink, in the U.S.

Bluedot Living magazine is published quarterly and is available at newsstands, select retail locations, inns, hotels, and bookstores, free of charge. Please write us if you’d like to stock Bluedot Living at your business.

Editor@bluedotliving.com

Sign up for the Martha’s Vineyard Bluedot Living newsletter, along with any of our others: the BuyBetter Marketplace, our national ‘Hub” newsletter, and our soon-to-be-launched Bluedot Kitchenr: bit.ly/MV-NEWSLETTER

Subscribe! Get Bluedot Living Martha’s Vineyard and our annual Bluedot GreenGuide mailed to your address.

It’s $24.95 a year for all four issues plus the Green Guide, and as a bonus, we’ll email you a collection of Bluedot Kitchen recipes.

Subscribe at bit.ly/MVBluedotSubs

Read stories from this magazine and more at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

Find Bluedot Living on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube @bluedotliving

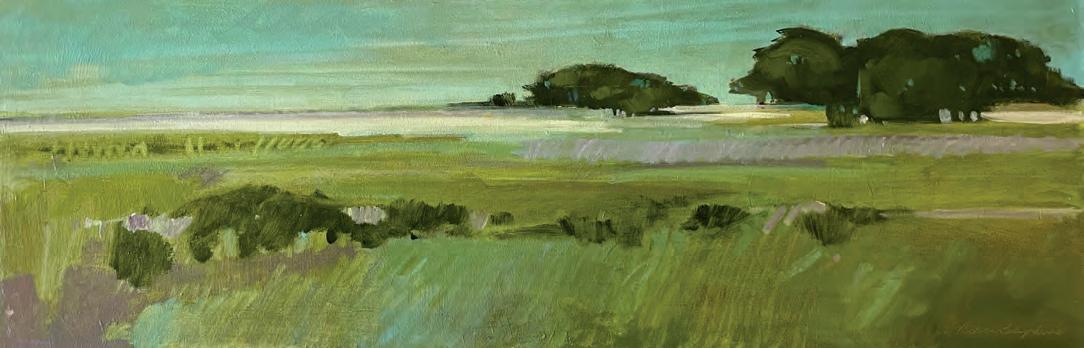

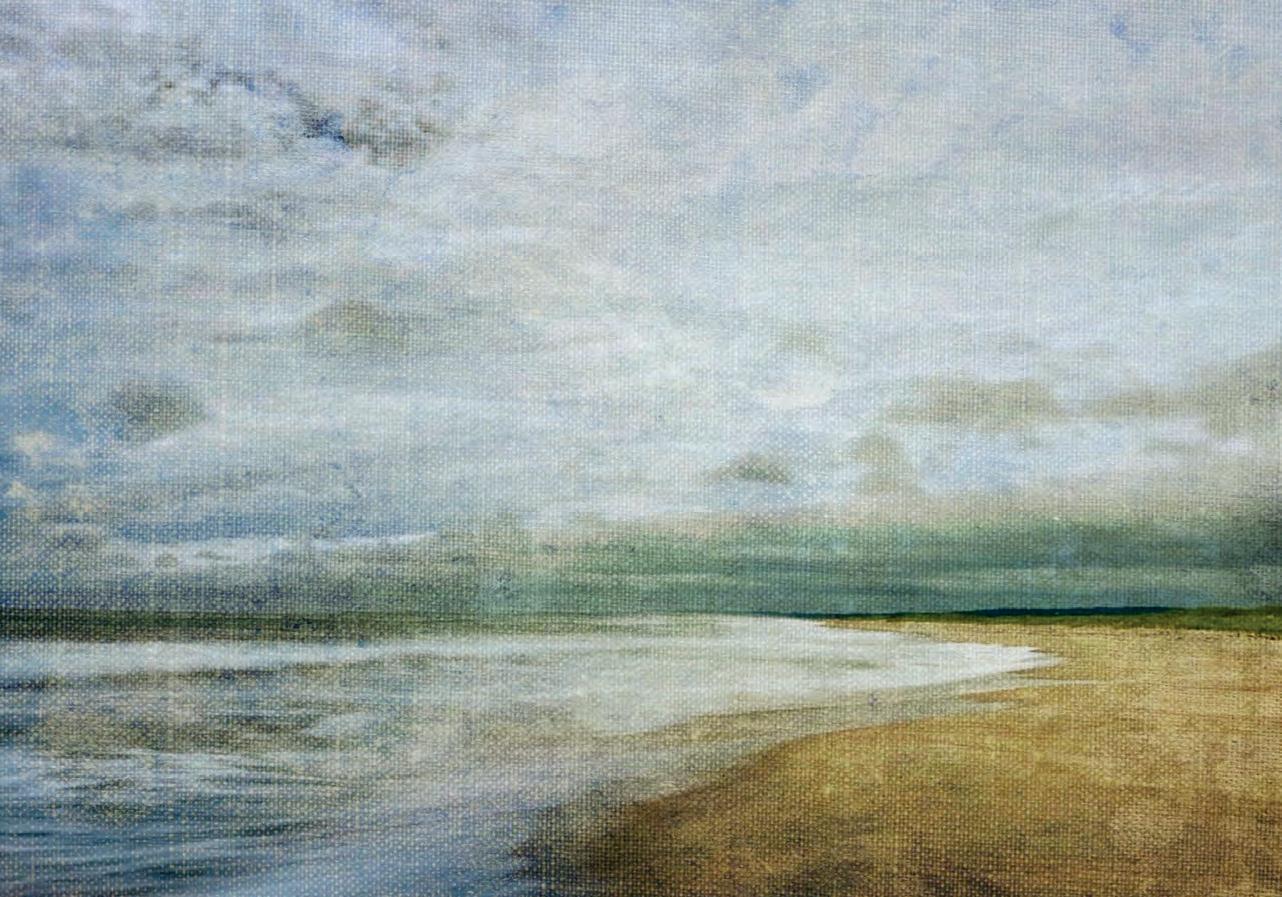

Did you know that the nineteenth-century landscape artists are credited with inspiring the conservation movement, and the creation of American national parks? Here on the Vineyard, our artists memorialize views we might not see on our own, or views that might one day be lost — to the sea (or maybe to development), and maybe encourage us to become better stewards of the land around us.

W hen I mentioned to Art Director Tara Kenny that I wanted to have a lot of wonderful landscape art in this issue, she said, “You should have Doug Cooper write about the geology of those landscapes.” Doug Cooper, father of associate editor Julia Cooper, and an Island soil engineer and geologist, shared his “Island Geology Tour” with many of us Bluedotters last fall. He explained to us how varied and unique MV is, with its sandplains and glacial moraines, great ponds and salt marshes. We asked Jennifer Pillsworth and Chris Morse at the Granary Gallery (and Field Gallery) to select some images that represented the variety of landscapes artists captured over the years. Doug Cooper explains in the text how those features came to be.

Big thanks to Doug, and to Jennifer Pillsworth and Chris Morse for all their help and enthusiasm.

I have a new colleague at Bluedot MV: Britt Bowker will be taking over as editor of this magazine as the year goes on (I’ll still be involved!). Britt worked at the MVTimes, and recently

A year-round business serving the Island of Martha’s Vineyard for their furniture, mattresses, bedding, and home decor needs.

The Boston Globe. Welcome, Britt!

More news: We’ll be launching our Bluedot Kitchen newsletter this fall. You’ll find recipes, tips on avoiding food waste, and good stories about the people who make our food. Sign up here: bit.ly/BDL-newsletters

O ur Late Summer issue, out in August, will be entirely devoted to food on the Island, so you’ll get a taste of Bluedot Kitchen.

Human/Nature, Art and Conservation on Martha's Vineyard will be at the MV Museum from Sept. 19 to Jan. 12, 2025. More info at: bit.ly/MvMuseum

Until then — thanks, as always, for reading.

– Jamie Kageleiry

By Lucas Thors

By Doug Cooper

Hermine Hull

Sam Moore

By Geraldine Brooks

Lucas Thors

By Kelsey Perrett

Vineyard students immersed themselves in backyard foraging, energy resilience, and more at the sixth annual gathering.

Story and Photos by Lucas Thors

Felix Neck Preserve, a sanctuary that spans hundreds of acres and is home to a rich variety of plants and wildlife, was filled with Island students for the sixth annual Martha’s Vineyard Climate Summit. I arrived at the sanctuary early Thursday morning, as sleepy but excited students filed off buses and gathered around Felix Neck

staff members to get familiar with the day’s agenda. Rain was in the forecast for later in the afternoon, so there was no time to waste.

Teachers and naturalists at the preserve have nurtured the next generation of eco stewards for decades by offering naturebased education to students of all ages. The climate summit gives

On our one-year anniversary as the first B Corporation certified bank in Massachusetts, our deep connections to community, local business, and environment continue to inspire our mission of banking as a force for good.

“Felix was a Wampanoag person, and a farmer, and he knew how to care for this land.”

–Alexis Moreis, Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) member

Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School and Martha’s Vineyard Public Charter School students the opportunity to guide their own learning, and let their interests dictate the day of outdoor education. Students led various roundtable discussions on topics like Wampanoag land stewardship, fast fashion and thrifting, and creative ways to reduce plastics. They also worked with their teams to design conceptual garden plots using string as a grid and cards representing the different crops. Students made flower prints, and foraged for native edible plants in other hands-on workshops.

MVRHS science teacher Heather Lochridge spoke to groups about Island Eats, a local organization that’s offering a reusable alternative to single-use plastic takeout containers. (See bit.ly/ IslandEats.) “We all know how bad single-use plastics are. Island Eats offers stainless steel bowls with silicone lids — a bunch of different

restaurants and coffee shops have partnered with them,” Lochridge said. “Some places also have metal soup containers and metal cups.” Students at the climate summit ate lunch in Island Eats stainless steel bowls, giving them a firsthand look at the rapidly-growing program.

At an adjacent table, members of the local renewable energy cooperative Vineyard Power gave students a rundown on the organization’s goals, and how they’re supporting individuals, families, and businesses transition to clean energy. Luke Lefeber, Vineyard Power controller and renewable development manager, said his team is working with the community to build solar installations and integrate them with local battery storage. “Eversource can only do so much, so you need to ensure that the island also has the capacity to create resilience for itself,” he said. “How can the community provide its own energy and store that energy if Eversource has an issue?”

Before the Smith family began farming at Felix Neck around 300 years ago, Wampanoag Tribe member and farmer Felix Kuttashamaquat lived and farmed there. Respect for the ancient indigenous stewards and original tenders of the land — the Wampanoag people — was a central theme of the daylong climate dialogue. Del Araujo and Alexis Moreis, two Wampanoag Tribe members, sat in one shaded area of the Felix Neck campus known as Kuttashamaquat Corner to discuss indigenous land use on Martha’s Vineyard.

Conch, or welk, they said, has a rich gastronomic and cultural history on Noepe (the Wampanoag name for Martha’s Vineyard), and

Webster’s Dictionary defines “cooperation” as: “operating together to one end; joint operation; concurrent effort or labor.’’ This accurately describes VINEYARD HOME IMPROVEMENTS’ culture and approach to every project. Our staff recognize the importance of partnership, and the ability to work as a team, as well as the necessity of being fair and flexible.

• Experienced in all phases of residential and commercial building construction.

• Skilled Craftsmen

• Design & Value Engineering

• Team Approach

Equipped to handle the more complex multi-story/multi-unit new projects, yet agile enough to execute the smaller jobs with the same degree of professionalism.

is very profitable internationally. Moreis said Indigenous sustenance rights are essential to the fabric of the Wampanoag community. Many tribes were forced onto small plots of land to farm, forage, hunt, and fish. Moreis said they are still fighting to reclaim the land they stewarded for millenia. “It’s important to have Indigenous communities steward the land and remain in control of these resources, and have them preserve the biodiversity in some of these natural spaces, like Felix Neck,” Moreis said. “Felix was a Wampanoag person, and a farmer, and he knew how to care for this land.”

The well-groomed trails and unique biodiversity of the Felix Neck woodlands, meadows, ponds, salt marsh, and shorelines make it the perfect outdoor classroom. Forager, cook, and internet personality Alexis Nikole, known online as Black Forager, has been exploring the preserve since she was a child. Nikole, who has more than 4 million followers on TikTok, was the guest of honor at the climate summit, and led a foraging walk where she pointed out common edible plants, and gave tips on how to make healthy and delicious foraged meals. “This is a milkweed plant. These guys only need a quick blanche for them to be rendered edible. At this stage it’s very asparagus-like. If it snaps like this when you break it, that means it’s good eating,” Nikole said.

While Nikole led groups around the campus, she described the connection between foraging and responsible land management. She said that when Europeans first arrived in America, they were surprised to find natural spaces so abundant in wild game and edible plants. “These spaces didn’t look like farms, but they were extremely productive. To them, it must have felt like a magical land filled with bounty,” Nikole said. “The reason for all that bounty and all that diversity was the stewardship practices that occurred in the United States prior to European arrival.”

Some students attended round table discussions where they heard practical tips on how to live more sustainably.

Forager and internet personality Alexis Nikole speaks with students about one of her favorite native edible plants, milkweed.

Executive director of Vineyard Conservation Society Samantha Look told participants that they as consumers have the power to steer the direction of commerce and production away from excessive consumption. “Ever heard of people referring to voting with your pocket book?” Look asked. “We are constantly being told we need the next best thing, whether it’s the latest season of fashion, or the newest phone. But because we can exert pressure on these companies by simply not buying more stuff, we are actually in control — our possessions don’t have to be our jailer.”

Team exercises at the climate summit prepared students to stand up and make their voices heard at town meetings, as so many consequential environmental decisions are made on the town meeting floor. Each team had to defend their stance on how an imaginary plot of town land would be used. Some students advocated for turning it into a public park, while others suggested preserving the land in its original state, and using some of it to create affordable housing.

“Studies have shown that time spent outside in parks can help people fight against mental health issues,” MVRHS student Senique Wilson said as she held a stick that served as her “microphone.”

Additionally, Senique pointed out that people visiting national parks contribute billions of dollars to regional economies, while creating hundreds of thousands of private sector jobs. “I believe we should continue to support the public environment,” she said. MVRHS students Finn Robinson and Brodie Vincent represented the interests of solar developers, and said using the parcel of land to construct a ground-based solar array would increase the community’s access to renewable energy, and reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

Bangii-Kai Bellecourt, a student and member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), suggested that the land be used to create affordable housing and the remainder of it be preserved.

“There is an extreme housing issue on this island, and development is causing an issue with native plants and animals. Land preservation is very important to me and has been important to my people, who have lived here for over 15,000 years, and continue to live there.”

Serving the Community of Martha’s Vineyard 1(833) MV SOLAR (687-6527)

Solar System Installation

New & Retro t Battery Storage Canopies & Pergolas

Commercial & Residential

By Lauren Sinatra, Town of Nantucket; and Gail Walker, Founder of Nantucket Lights

In many communities, people leave on too many outdoor lights at night. This ever-present glow, known as light pollution, is interfering with our ability to enjoy the natural beauty of the night sky and is harmful in other ways. It’s also a huge waste of energy.

Nantucket has had an outdoor lighting bylaw in effect since 2005, and even stronger regulations were adopted in 2023 to address the growing light pollution on the island. In general, unless falling within an exception, all outdoor lighting must meet four requirements. It must (1) be fully shielded (meaning no light can be emitted upwards) if the light is brighter than 600 lumens; (2) have a warm color temperature of 2700K or lower; (3) not exceed specified limits on brightness; and (4) be turned off between 11 pm and 6 am.

To help property owners comply with the new requirements,

proponent of the new regulations — offers comprehensive guidance, and is working with the Town of Nantucket to urge property owners to take a careful look at their own outdoor lighting to ensure that it uses minimal energy and complies with the new regulations. To lead by example, the Town aims to upgrade all outdoor lighting at its facilities, is integrating lighting bylaw requirements in the design of new construction projects, and is investigating converting the streetlights on the island to more dark-sky friendly and energy-efficient models.

Read all about Nantucket’s efforts to save the night at bit.ly/ ACK-dark-skies.

By Corey Burdick

The Intervale, located between the Winooski River and Lake Champlain, is a gorgeous mix of farms and trails. Because the area served as a city dump from the 1930s to the 1990s, the observant trail explorer can spot vintage car parts peeking around the roots of trees. A local entrepreneur led a community cleanup, which restored soil health and inspired the germination of organic farms, gardens, and year-round recreation. But with all of this activity and public use comes the need for

maintenance. Duncan Murdoch, the Intervale’s Natural Areas Stewardship Coordinator, had participated in a trail stewardship program when working as a horticulturist in New York City, and he thought something similar could work in Intervaleas well. Turns out he was right.

Murdoch developed the Burlington Wildways trail stewardship program after collaborating and consulting with Rock Point, a center of the Episcopal Church in Vermont. Rock Point stewards 130 acres of publicly accessible conserved lands and already had a similar system in place. After securing the buy-in of the Burlington Parks and Recreation Department and the Winooski Valley Park District, the trail stewardship program launched in 2020. By 2022, 52 volunteers were logging an annual 484 reported hours in the program, working across the wildways at the Intervale Center, Rock Point, Riverwalk/ Salmon Hole, and McKenzie Park. The primary responsibilities of a trail steward are to identify issues on the trail and, if possible, remedy them in the moment — restocking supplies at information stations, for instance, or picking up trash. When a steward is unable to solve an issue, they use an app to snap a photo and report it.

Learn more about the Burlington Wildways trail stewards at bit. ly/VT-trail-stewards.

DEER, TICK & MOSQUITO CONTROL!

(508)627-2928 | MV@oh-DEER.com oh-DEER.com/locations/MV

By Frederick O’Brien

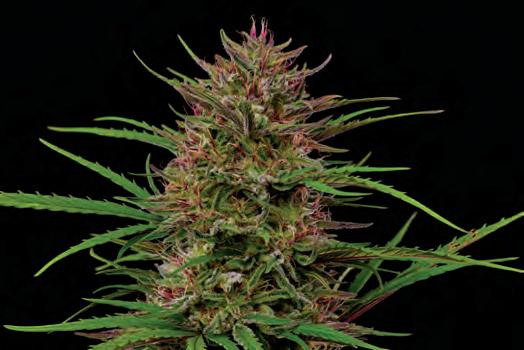

Joseph Haggard’s family has been tending land in Mendocino County, California, since his great grandmother bought property there in 1936. On their farm, Emerald Spirit Botanicals, the family grows fruits, vegetables, and cannabis.

California legalized cannabis in November of 2016, and by 2023, annual sales in the state amounted to $5.9 billion. While legalization has opened the door to many opportunities, it’s also brought challenges. The Haggards are one of dozens of families who own cannabis farms in the “Emerald Triangle” — a region in northwest California renowned for its cannabis produce — who have been feeling the squeeze of an industry with growing big money players.

In many respects, the questions asked by cannabis consumers are the same as those asked by consumers of other products: Where did the product come from? How can I know that it’s good quality? What makes its quality good? Do production methods align with my values?

In the world of cannabis cultivation, such questions revolve around environmental impact, workers’ rights, and the potency of the drug itself. In much the same way that certifications like Fairtrade strive to encourage ethical production practices, Sun+Earth Certified is having a positive impact on grassroots cannabis cultivators.

Read more about regenerative, community cannabis farming at bit.ly/CA-cannabis-agriculture.

Emerald Spirit Botanicals's Pink Boost Goddess strain.

• SAFE FOR YOU, YOUR FAMILY & PETS!

• KILLS TICKS & MOSQUITOS ON CONTACT.

• AN EFFECTIVE ‘GREEN’ ALTERNATIVE TO PESTICIDES & CHEMICALS

ohDEER offers you and your family a proven and safe solution to control ticks and mosquitoes so that you can enjoy your yard. Our products are true all-natural repellents that contain no pesticides or chemicals of any kind.

Toronto, Canada

By Alec Ross

There’s a lot to love about Toronto’s ravines. Their trees still help clean the air and suck CO2 out of it. They provide habitat for countless insects, birds, and small mammals. They serve as havens where people can walk and ride bikes and generally escape the busyness and noise of urban life. And they allow runoff to drain away from city streets into local waterways like the Don River and Lake Ontario.

Over the years there have been major changes in the

ravines. Their dirt paths are now paved over to accommodate the increased foot and bicycle traffic and many of the ravines’ native trees and shrubs have been crowded out by invasive species. One of these species, the Norway maple, is particularly nasty because it is poisonous to insects and other plants. If there are no insects, there are no birds, and if no other plants can grow nearby, the greenery on the forest floor withers away. Thus, if Norway maples and other invasives proliferate, they will ultimately take over and slowly degrade the important ecological services provided by the ravines and the diversity of the wildlife that lives there.

In 2005, in collaboration with a nonprofit organization called Forests Ontario, the City of Toronto launched the Tree Seed Diversity Program. In this program, private seed collectors hired by the city gathered acorns from High Park and the Glen Stewart Ravine, and a couple of nurseries north of the city nurtured the acorns into seedlings in controlled growing conditions. The idea was that as invasive tree species died or were selectively removed by arborists, they could be replaced with healthy young oaks that, over time, would help restore the compromised ecosystem balance.

Read more about Toronto’s Tree Seed Diversity Program at bit.ly/Toronto-Seed-Diversity. On Martha’s Vineyard, Polly Hill Arboretum offers shrubs and other plants grown from local Island seeds.

By Julia Cooper

Bluedot’s Creative Director Tara Kenny

spotted Loren Sipperly in a fabulous pair of patched-up pants at the Chilmark Flea Market last summer. We knew there had to be a story behind these jeans, so we reached out to learn more.

Julia Cooper: Where do you get the materials to make your patches?

Loren Sipperly: I patch mainly with my favorite tiny things that belonged to my daughter. The darker patches on the pictured jeans are from a sweet dress of hers when she was maybe 3. Some of the corduroy is from a pair of her bellbottomed toddler pants. I also use vintage iron-on patches

and souvenir patches from places we’ve been. My family is a bunch of thrift store fanatics so for most other patches, I buy children’s clothes and interesting fabrics at thrifts. My friends give me fabrics from projects they disbanded. I save everything.

JC: How long have these jeans lasted you?

LS: I have many pairs, first of all. Most are 15 to 20-plus years old, but this pair is nine. All of my jeans are patched as they are crazy old, but they are my treasures. They’re wearable art and neat reminders of my tiny kids who are now grown ups. I never throw away a decent pair of fixable jeans.

JC: What’s your favorite part about the process?

LS: I have zero background in sewing, but have found it incredibly soothing hand stitching my jeans.

JC: What advice do you have for people who are interested in repurposing their own jeans?

LS: Save it. Make do and mend. If a pair of jeans is too far gone, make shorts. Or use them to patch other pants. Most of all, be creative. If one patch fades, you can always replace it. Folks looking for advice and tips can reach me at azulikit@icloud.com.

Do you upcycle? Make new treasures from thrifted finds? Write us at editor@bluedotliving.com.

Using less energy is better for your home, your business, and the planet! Start with a no-cost energy assessment to find out how you can save energy and qualify for incentives on efficiency upgrades like HVAC, weatherization, and more.

Visit CapeLightCompact.org to sign up for a no-cost energy assessment.

ASa kid, I thought magnolia trees bloomed in anticipation of my early June birthday. These days, they celebrate those born in May (or even April), their lovely pink petals on the ground by the time my date rolls around.

We see other changes, too. Mosquitoes begin to annoy in early May, when they used to wait ’til Memorial Day. Daffodils pop up weeks earlier than before. Ask maple syrup producers, and they’ll tell you they’re tapping trees — done when daytime temps are routinely above freezing, while nighttime still dips below — earlier each year.

following in the footsteps of his father, whose records went back to the late 1800s. What his data showed was what we’re all seeing: change.

Professor Ed Hawkins at the University of Reading in the U.K. conceived of “heat stripes,” a way to make clear the changes we’re experiencing.

“No words. No numbers. No graphs. Just a series of vertical coloured bars, showing the progressive heating of our planet in a single, striking image,” is how his site describes heat stripes.

By Leslie Garrett

We’re not imagining this. The Washington Post recently put together a chart of how bloom times are changing.

Phenology is the study of these cyclic and seasonal phenomena, our dictionary tells us. The National Phenology Network (yes, it’s a thing!) keeps careful track of these changes. And some of us laypeople keep careful records of these changes too, such as the guy I knew who lived beside a lake who had spiral bound notebooks filled with the dates of when the ice formed on the lake and when it melted. He was

But what phenology doesn’t include are the feelings that accompany these long-relied-upon markers of time — when certain trees bloom, when certain bugs emerge, when certain birds return or leave.

A group of women created the “Tempestry Project,” based on Professor Hawkins’ stripes, as a way for us to process our feelings around these changes and channel both data and emotion into hand-woven tapestries.

The result is lovely. And devastating.

For that, we’ll need another word.

The Community First Partnership helps Island residents and small businesses increase energy efficiency, decarbonize their buildings, and save money.

BY LUCAS THORS

MassSave was established in 2008 to help Massachusetts achieve its energy efficiency goals.

The program provides no-cost energy assessment and helps people upgrade their home's insulation, heating and cooling systems, and add energy-efficient appliances (even electric lawn equipment). Funding for MassSave comes from a surcharge on all Massachusetts ratepayers' electricity bills. Cape Light Compact administers MassSave on the Cape and the Island.

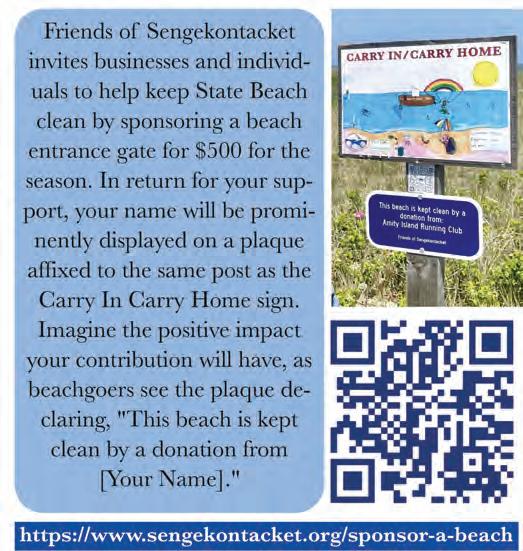

In 2023, the Cape Light Compact selected the Island towns and Vineyard Power for their Community First Partnership to participate in the MassSave programs. The partnership seeks to expand access to energy efficiency and decarbonization funds “through strategic partnership with the Island’s six towns, collaboration with other Island organizations, community-based social marketing, and community-based outreach,” according to Vineyard Power’s Energy Transition Coordinator, Thamiris Marta, whose goal is to connect with all Island ratepayers — renters, landlords, residents whose primary language is not English, low-tomoderate income residents, residents of Environmental Justice communities (such as Aquinnah, Oak Bluffs, and parts of Tisbury), and small businesses.

You can start by getting a no-cost energy home assessment; an energy specialist will assess your home’s insulation, make recommendations for improvements, then present options to convert heating and water systems.

“Participants are matched with an approved insulation contractor if insulation work is recommended, and then given a list of approved local HVAC installers if system upgrades are recommended and desired,” Marta said. Financial incentives cover at least 75 percent of the cost of recommended work, and up to $10,000 for the installation of mini-splits. “The program may cover up to 100 percent of insulation and system upgrade costs for low- and moderate-income households,” Marta said. Costs that are not fully covered may be financed with a zero percent loan called the HEAT loan.

In 2023, approximately 800 households used Vineyard Power’s myriad energy efficiency programs; about 150 of those were low-to-moderate income households. Through the Community First Partnership, Vineyard Power is leading local outreach campaigns, building relationships with Island municipal and non-municipal organizations, and creating multilingual content to promote programming. “We worked closely with each town to distribute tax bill inserts that are sent out to all homeowners as a call to action to sign

up for a no-cost home energy assessment,” Marta said. Vineyard Power has also built relationships with each Island town’s affordable housing committee, with public libraries, senior centers, faith-based organizations, local nonprofits, grocery stores, and the Island Food Pantry to provide educational resources, host regular tabling events, and offer presentations on energy efficiency and electrification.

“Our goal is to make sure each individual, family, and small business on Martha’s Vineyard has access to energy efficiency improvements, the benefits of constantly advancing technology, and the financial incentives surrounding strategic electrification,” said Vineyard Power Program Analyst Sophie Pittaluga.

In addition to the Community First Partnership, Vineyard Power helps income-eligible Islanders reduce their energy cost burdens. Through the Resiliency and Affordability Program, Vineyard Power and Cape Light Compact distribute checks semi-annually to 430 income-eligible ratepayer households on the Island to subsidize electricity costs. These grants — totaling $190,000 in 2023 — resulted in an average savings of $300 to $400 per eligible household.

Income eligible ratepayers must be enrolled in the Eversource Discount Rate (either the R2 or R4 rate class) and the Cape Light Compact power supply program to receive grants from Vineyard Power. Vineyard Power supports enrollment in the Eversource Discount Rate and Cape Light Compact power supply program, as well as enrollment in other programs, such as the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP/Food Stamps), and Low-Income Community Shared Solar programming through Vineyard Power’s Resiliency and Affordability Program partner Citizens Energy.

“It’s critical to ensure that the members of our community who are most in need are provided with a community resource that offers education, support, and guidance regarding these programs, especially for the elderly and English-isolated residents,” said Luke Lefeber, Controller and Renewable Development Manager at Vineyard Power. “Most people are unaware of these programs or don’t believe they qualify. But these programs can make such a difference in the transition away from fossil fuels.”

Vineyard Power office is located at 151 Beach Rd. in Vineyard Haven. Visit vineyardpower.com or call 508-693-3002 for more information about the Community First Partnership, and sign up for no-cost energy coaching at vineyardpower.com/energy-coach.

There are, as I write this, air quality warnings across the U.S. northwest, thanks to wildfires in British Columbia. And there are — no kidding — some social media accounts calling out Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, a Liberal and proponent of a carbon tax, for somehow sending this smoke to the U.S.

Against this tragicomic backdrop, scientists have conceived of a new measure of climate change. Something they’re calling “outdoor days.” The term aims to make the impacts of climate change feel more tangible to average people for whom the standard measures — mean temperature and extreme weather events, such as hurricanes — are less intuitive. Outdoor days are exactly what they sound like: the number of days conducive to outdoor activity. Or, as the research team at MIT put it, “‘Outdoor days’ are defined as the number of days with moderate

temperature, neither too cold nor too hot, that allows most people to enjoy outdoor activities, like walking, jogging, running, cycling, and more broadly enjoy travel and tourism.” Study team member Yeon-Woo Choi and his collaborators at MIT found that the historic trend of more outdoor days in the Global South than the Global North will reverse this century. “In tropical areas, outdoor days have decreased by about 13% in the last three decades compared to the period 1961 to1990,” the researchers write. “Meanwhile, high-latitude countries have experienced a 13 percent increase in the number of outdoor days.”

But before those of us who think we’ll benefit from this trend throw an outdoor party, let’s dig a little deeper into the data. Regions in the Northern hemisphere that have historically enjoyed an outdoor-days-friendly climate might also find themselves driven indoors. Texas, for instance, will see 43 fewer outdoor days, thanks to extreme heat. And, as a Canadian I noted that, while the Great White North is predicted to gain 23 outdoor days, they are mostly in the spring and fall. In fact, we will have fewer outdoor days between June and September than we do currently. Can we blame Justin Trudeau for fewer lovely summer days? The PM loves to paddle on a Canadian lake, so despite what social media would have me believe, I think he’s off the hook for this one.

- Leslie Garrett

Dot tackles your thorniest questions from a perch on her dock.

Dear Dot,

I've heard that it's good to put a bee bath in my garden, because bees get thirsty and need water. I hesitate to leave out any standing water, though, because I don't want to invite mosquitoes to hatch. Do you have any suggestions?

–Thirsty for Pollinators, New York, NY

Dear Thirsty, Dot is delighted to report that your fears are unfounded, assuming, of course, that your bee bath will be well maintained and refilled with fresh water every few days or so.

Consider this, Thirsty: Birds will likely share this bath with the bees (and why not? There’s no harm in a common water source!). And birds love little more than dining on mosquito larvae. If it’s there, they will eat it. What’s more, larvae take seven to seven 10 days to hatch. If birds haven’t consumed all the larvae, you will have dumped it all out when you refill/clean the bee/ bird bath every three or four days. If you remain concerned, you can

add some motion to your (wee) ocean, which will repel mosquitoes, who prefer their water still. A water wiggler (on Amazon) will add ripples to your bath and delight birds. While the sound might still attract bees — gurgling water means fresh water in the apian arena — bees are more likely (and safer) to stick to the edges of the bath where there’s no danger of falling in, while birds will happily frolic. ’

– Splashily, Dot

Dear Dot, How bad is it to use my barbecue? Are there good alternatives?

–Lee

Dear Lee, Your timing, Lee, is impeccable. You reached out to Dot on what is very nearly the eve of Back to Barbecue Day, a holiday (May 27) entirely made up by the Hearth, Patio, and Barbecue Association (it’s a thing, Lee!). And why not! Dot loves a good grill, a backyard barbecue, a patio party.

But, while I’m delighted you’re carbon-curious about your grill habits,

Lee, the fact is that outdoor cooking in North America makes up just a teensy-tiny part of carbon emissions. What’s more, Dot, as I’ve mentioned before, is Canadian: We Canucks have barely a nanosecond of weather conducive to outdoor grilling, so are more than a little wary of anyone who wants to pry those BBQ tongs out of our hands. After surviving a Canadian winter, we deserve to grill, goshdarnit! But even those of you who barbecue more frequently in more temperate parts of the continent aren’t likely to create an outsized carbon cook-print. In other words, Lee, while I’m happy to grill the experts on how to cut carbon, don’t sweat your outdoor cooking method too much.

There are parts of the world, including China, India, and regions of Africa, where cooking over “solid fuel sources” (typically wood) does contribute substantially to carbon emissions, and harms local health. The Clean Cooking Alliance, a U.S.based organization, works to shift

the more than one in three people globally who cook on an outdoor or wood-burning stove toward cleaner, safer methods. So bravo to them! Nonetheless, Lee, when we know better, we do better, as the saying goes, so let’s consider the ways we can put the sustainable in our sizzle. Let’s begin with what we’re grilling. Beef, we know, is particularly bad for the planet — both from massive deforestation for cattle farming, and the methane released when these cows burp and pass gas. Taking beef off your grill is a good idea. Rather than replacing it with another meat product, consider going 100% plant-based. Dot remains convinced that you could grill cardboard and it would taste delicious. Asparagus? Peppers and onions, tossed in garlic? Par-boiled potatoes coated in olive oil, seasoned with salt and pepper, and grilled over high heat in a cast-iron pan until the edges are crispy but the insides are soft? Oh yes, please! (If you’re looking for more inspiration, check out The Gardener

& the Grill, which comes highly recommended by our Marketplace Editor, Elizabeth. Find it on Amazon.)

Regarding what heat source we’re cooking these delectable delights over, while charcoal remains the choice among a select group who turn up their noses at propane or natural gas grills, it is, for the most part, the least eco-conscious choice. For one thing, burning charcoal is essentially burning carbon. And while there is responsibly sourced charcoal, researchers in a paper produced through United Nations Environment Program report that “even so-called ‘renewable’ charcoal has a detrimental effect on the environment through the use of monoculture, which compromises biodiversity.”

As for natural gas, Dot firmly believes it would be more accurately branded as simply what it is — methane. And we know, from another Dear Dot column, just how nasty methane is environmentally. As I wrote, “Drilling and extraction of natural gas leaks a greenhouse gas that

is particularly potent (from a heattrapping point of view) — methane. … And how potent is this leaked methane? About 30% more potent than CO2.”

How does propane stack up?

“Propane is usually more efficient, burning faster and hotter, and thus using less fuel with every backyardcooking session — and unlike a natural-gas line, it doesn’t keep you dependent on the fossil-fuel-delivery industry,” reports The Atlantic.

If you’re determined to reduce even your teensy tiny barbecue footprint, Lee, Dot encourages you to go electric (as with so many other aspects of our homes and lives). Even the heavyweights of the barbecue world, such as Weber and Breville, are offering electric versions (on Amazon). Or tap that sun to put sizzle on your plate with a solar grill, also on Amazon. (Rewiring America offers a guide to electrifying everything in your home — and why it matters. In brief: As we transition our grid to include more energy from renewable sources, we need appliances

that aren’t reliant on fossil fuels.)

Whatever you decide, Lee, remember that backyard grilling is small fish compared to the other ways we contribute carbon to the atmosphere. Changing what you grill (and eat, generally), how you move yourself around, and how you heat and cool your home will have a far greater impact.

- Heatedly, Dot

Please send your questions to deardot@bluedotliving.com

Want to see more Dear Dots? Find lots here: bit.ly/Dear-Dot-Hub

From news about local climate issues to planet-friendly recipes and tips on sustainable shopping, Bluedot Living delivers enlightening and eco-conscious ways to reduce our impact on Earth.

Questions and answers for everyday eco-friendly living.

Strive to buy less, but when you do buy — buy better.

On-the-ground reporting highlighting a universe of ideas and changemakers.

Discover recipes and waste-saving kitchen ideas.

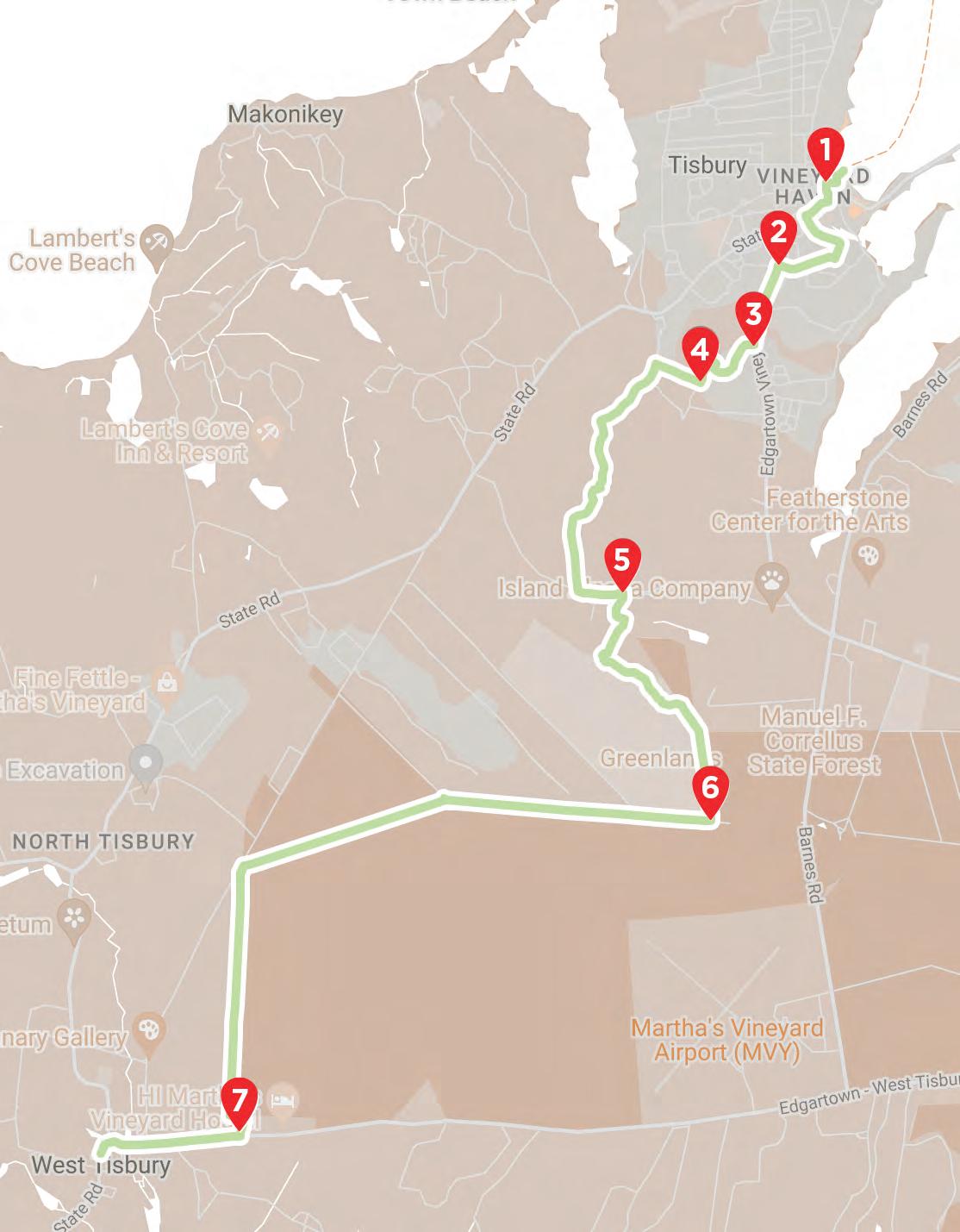

After 10 miles, countless scenic vistas, and a few blisters, I adore the Vineyard more than ever.

Story by Lucas Thors

It was 7:56 am when my girlfriend and I pulled onto Northern Pines Road and filed our way into a line of traffic headed toward the starting area. The annual Cross-Island Hike (XIH) was scheduled to kick off at 8 am sharp.

This was going to be a long day, and the online schedule for this hike explicitly said it would be “briskly led,” so there was no fudgefactor in our timing. Soon, it was time to go, and a stream of hikers meandered up from Hillman’s Point beach amidst a shimmering Lake Tashmoo backdrop. Along with Bill Veno (Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank trail manager, senior planner at the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, and longtime XIH coordinator), a few other familiar faces headed the pack. Photographer and outdoor enthusiast Randi Baird waved hello as she captured the determined smiles of hikers just beginning their journey. Island author and historian Tom Dresser kept pace, ready to take on yet another XIH. “I don’t know if it’s been every year, but it’s been at least 15 times, just not consecutively,” Dresser said. “I love it, it’s a great thing that gets

everyone together; and beautiful weather today, too.”

For 32 years, the Martha’s Vineyard Land Bank has celebrated National Trails Day on June 1 by hosting the Cross-Island Hike — this year exploring 17 conservation properties and five named ancient ways. Approximately 135 people participated in the trek. Some 99 started but didn’t stay for the whole walk, and 42 dauntless folks completed the full 19.2 miles from Hillman’s Point Preserve to the Chilmark Pond Preserve. It was entertaining to watch Veno lead the way on yet another new adventure for him — the route changes each year in order to paint the broadest possible picture of the island for participants. Going from trail to trail illustrated how diverse and interconnected the natural spaces on-Island are. One minute we’d stroll through farmland and along horse paddocks at the John Presbury Norton trailhead, and the next we’d traverse a winding tunnel of tall vines along Ice House Pond on the Manaquayak Preserve.

According to Veno, the only training he does for the XIH

Cross-Island hikers weave along a Chilmark trail.

is walking his dog. “This year felt really good. For some reason it seems like the older I get, the less sore I am afterward,” Veno laughed. Normally, Veno will walk each segment of the hike beforehand, but this year he just figured it out as he went along. With a few minor course adjustments, Veno kept everyone on track. Being able to expose people to the trails and highlight the importance of connecting the island’s natural spaces is an essential part of Veno’s work with the Land Bank. “It’s all about promoting the network of trails that exists here,” Veno said. “and promoting a healthy lifestyle and an appreciation for the island.”

On a hike as long as this one, it’s tough to know what to expect, and there were a few moments along the way that I’ll never forget. The first occurred just a few miles in, when I slowed my stride briefly to grab a water bottle from my backpack. A soft voice came from behind. “Passing on your left,” an older hiker said as she continued briskly down the trail, hiking poles in-hand. I could tell she would be at the finish line, but I likely wouldn’t be seeing her

there. “Man, I really hope I can do the full thing by the time I’m that age,” I laughed to myself. I was impressed to see how many hikers were in their 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s, many of whom would be high-fiving and contemplating a dip at the beach after arriving at Chilmark Pond following a full day of adventure.

When the trail forked at Nip ‘N’ Tuck Farm in West Tisbury, Veno referenced the route map and pointed in the direction of some massive, feather-hoofed black and brown draft horses who seemed nervous about the unusual number of onlookers. As hikers progressed along the trail and snapped photos of the Fishers’ majestic livestock, one of the largest black horses somehow found himself on our side of the fence. My girlfriend, who has a good deal of experience with horses, ushered hikers along so as not to further spook the anxious animal. I grabbed my cell phone and called Nip ‘N’ Tuck. “Hi, we’re participating in the Cross-Island Hike, and it looks like one of your horses might have just escaped his paddock,” I said. “Okay, thanks for letting us know — we’ll send

Farmers might own the land, but the observant walker in time owns the landscape.

-Henry David Thoreau

someone down,” a calm voice said over the phone. That felt like a quintessential Vineyard moment.

We walked cautiously along Lambert’s Cove Road and arrived at the West Tisbury Public Safety Building around 10:30 am for a well-deserved break. Officers at the West Tisbury Police Station took pity on us sweaty hikers and let everyone in for a pit-stop. Meanwhile, peckish participants passed around donated snacks and refreshments — granola bars, raisins, trail mix, and cups of water. Then we got going again. The entrance to Roger’s Path alongside State Road must have looked like a deer trail to anyone driving by, but as we entered the shady section of forest, I saw how expansive the area actually was. Thousands of acres of Up-Island wilderness were hidden just off the main road.

As the group marched past Scotchman’s Lane around noon and began heading toward the West Tisbury Town Hall (the next checkpoint), I looked over at my girlfriend, who seemed like she could go at least another few miles. “I think it’s time for me to throw in the towel,” I told her with a weary smile. She quickly responded, “Beach time?” I nodded. “Yup, I think it’s beach time.”

After about five hours of trekking through the wilderness, I had expanded my repertoire of beautiful Vineyard hikes, and developed a greater sense of appreciation for my home. I’ll surely be back at the Cross-Island Hike next year, with the goal of crossing that finish line.

Targeted Departure Checkpoints (+- 5 minutes)

- 8:00

- 8:45

- 9:45

Start at Hillmans Point Preserve shoreline

A-B segment 2.1 miles

Ripley's Field Trailhead @ John Hoft Rd

B-C segment 3.1 mi (5.2 mi cumulative)

John Presbury Norton Trailhead @ State Rd

C-D segment 1.4 mi (6.5 mi)

Manaquayak Trailhead @ Lambert's Cove Rd

D-E segment .82 mi (7.3 mi)

West Tisbury Public Safety Building

E-F segment 1.4 mi (8.7 mi)

Roger's Path @ State Rd

F-G segment 1.1 mi (9.8 mi)

West Tisbury Town Hall

G-H segment 1.4 mi (11.2 mi)

Tiasquam Valley Trailhead @ Middle Rd

H-I segment 2.1 mi (13.4 mi)

Meeting House Rd @ Middle Rd

I-J segment 3.3 mi (16.7 mi)

Peaked Hill Trailhead @ Pasture Rd

J-K segment (2.6 mi (19.3 total miles)

- 3:20

Finish at Chilmark Pond Preserve shoreline

“The Gay Head Cliffs ... are magnificent beyond description. Here they rose in rugged ribbons of red, white, gray, yellow and black clay, 150 feet above the sea. ... The Wampanoag’s legendary Chieftan, Moshup, and his wife, Olesquant, are said to frequent the area. On foggy days, ‘tis said, you can see him smoking his pipe among the dunes ... and if you listen as the night gathers, you can hear Olesquant sing a lullaby to her children.”

–Wenonah V. Silva, teacher, historian, and former president of the Indian Tribal Council, from On the Vineyard by Peter Simon

“Moshup is believed by our tribe to be responsible for the present shapes of Martha's Vineyard, the Elizabeth Islands, Noman's Land, and Nantucket. From near the entrance to his den on the Aquinnah Cliffs, Moshup would wade into the ocean, pick up a whale, fling it against the Cliffs to kill it, and then cook it over the fire that burned continually. The blood from these whales stained the clay banks of the Cliffs dark red.”

–From Wampanoag Tribe/ Ancientways

TTThe variety of landscapes that comes from the variety in our geology — from sandplain grasslands to glacial moraines, and boulders to beaches — has drawn or inspired artists for centuries (see Hermine Hull’s essay on page 39).

The Vineyard’s community of artists, wrote Sam Moore in a story in Arts and Ideas Magazine five years ago, are a key ingredient in conservation. … “They have a dual role: Many of them are affected by the land around them, and they help set the terms by which other people appreciate it.

“Island artists help us look at the landscape still more closely — to understand what might be at stake, and to imagine what the future holds. Painters, photographers and sculptors represent a middle range on the spectrum between ecologists and everyone else. Artists share this acute sense of detail, but weave it into an aesthetic process that might influence less empirical minds.”

To find out how we ended up with the landscape, we turned to Island engineer and geologist Doug Cooper. We sent him images of paintings and photographs collected by Jennifer Pillsworth and Chris Morse at the Granary and Field Galleries, and by Art Director Tara Kenny, and we asked him to describe for us what, beyond art, we were looking at, how the geology created the landscapes that artists are perpetually inspired by, and the rest of us are moved to preserve.

– Jamie Kageleiry

Gay Head, at the Aquinnah Cliffs, has the oldest exposed geologic materials observed on Martha’s Vineyard, composed of ancient marine (sea bed) deposits that date back well before the glacial periods of more recent geologic time. The variable sands, silts and clays exhibit a wide range of colors that are visible from great distances under the right meteorological and sun angle conditions. As such, mariners were able to identify their location when sighting this brightly

colored headland (hence the name “Gay Head” was derived). The intensity of colors of the cliffs changes over time as erosive forces expose brighter or duskier layers. The cliffs have always been a favorite attraction for artists and sightseers. The headland was also the most logical site for early lighthouse construction. Cliff collapse and erosion can be impressive and has resulted in several relocations of the lighthouse over the years.

“No other landscape known to me has so many contracted slopes in an equal amount of profile; … nowhere else in this country do I know anything like the variety of scenic effect that is exhibited in this hundred square miles.”

–Nathaniel Shaler, Harvard geology professor and founder of Seven Gates Farm

“When we do conserve land for its sheer scenic beauty and provide for appropriate public access, we are able to appreciate nature for its grandeur. This effort matters, because danger always surrounds us, and we need the occasional glimpse of natural beauty to lift our spirits.”

Adam Moore, Executive Director, sheriff’s meadow, from A Year On Martha’s Vineyard

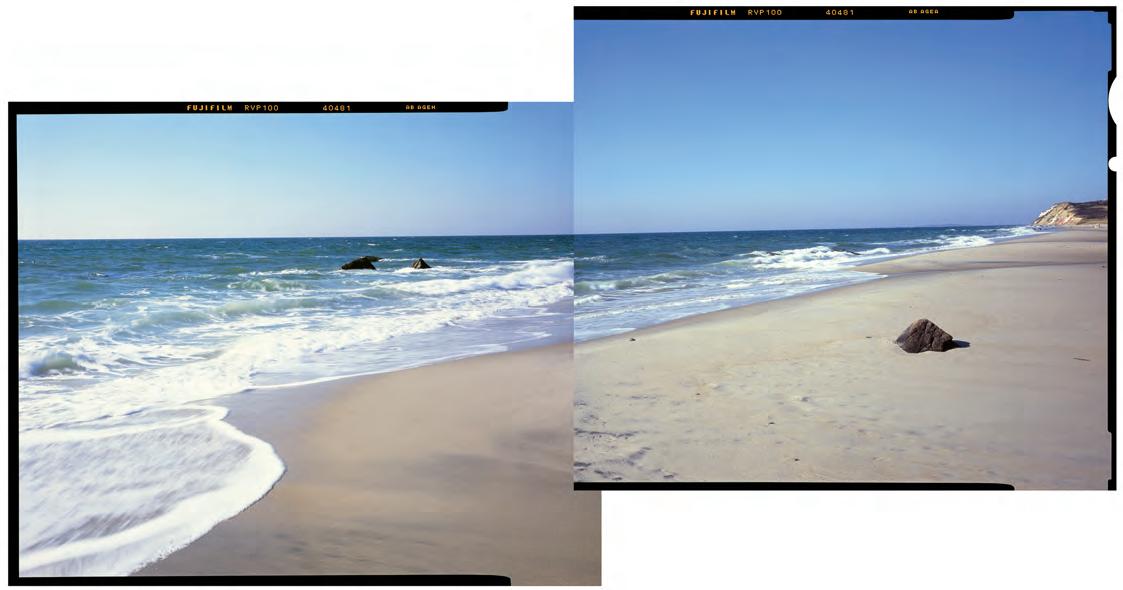

The beaches that surround Martha’s Vineyard are as variable as the landscape from which they have evolved. The exposure to the ocean currents and wave action on the earth materials determines the character of the beach. Erosion rates along the South Shore can be on the order of seven feet per year. Less dynamic settings that are protected from the brunt of coastal storms may retreat less. There are also beaches where transported sediments are

deposited resulting in “accretion” or beach building where the shoreline is extending outward rather than vanishing. There are areas where the shoreline retreat has exceeded 1500 feet since early colonists arrived. Periodic storm events often result in newspaper headlines of the destruction of a particular beach and the need to implement measures to “save” the shoreline. These measures will always prove futile in the long term.

Salt marshes develop along portions of our shoreline where the erosive energy of wind, waves, tides and currents are more benign. Accumulated sediments and organic materials allow the growth of salt-tolerant grasses such as spartina patens and spartina alterniflora to establish root systems. These grasses tend to accumulate even more organic material and fine sediments to form a resilient mat that serves to protect the shoreline and adjacent coastal banks from erosion. The marsh also supports numerous organisms that contribute to the food chain and sustain fin fish, nematodes, insects, shellfish, and birdlife, while contributing to water quality improvement.

Breaches of salt ponds, embayments and coastal estuaries can occur by natural, storm-driven events or by planned “openings” as part of a man-made management strategy. Whatever the mechanism, these cuts, breaches, or openings can profoundly influence the salinity, water quality, currents, sediment deposition, and aquatic life within the pond or embayment. Historically, cuts or breaches were accomplished to create conditions that would stimulate fish or shellfish production. More recently, sluicing of nutrient-rich waters out to sea and introducing a flush of cleaner salt water is viewed as a means to reduce algae blooms in the ponds.

“The happy combination of hill, declivity and plain, extensive regions and vistas of moor, pond, oak woods, windblown copses; of marsh ready to flame into fall color; of high bluffs and broad, sandy beaches; of boulders, old dirt roads; of memory, legend, and history …”

Henry Beetle Hough, founder of Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation, in On the Vineyard by

Peter Simon

The North Shore of the Vineyard is the polar opposite of the South Shore. This upland is dominated by the moraine deposit that identified the terminus of the last glacial advance.

Approximately 25,000 years ago, the rate of advance of the Wisconsin ice sheet slowed, stalled, and began its retreat northward. The accumulated sediments within and under the ice were dropped to form this side of the Island. Raging torrents of meltwater then carried some of the glacier’s load southward to form the outwash plain along the Island’s South Shore. The North Shore in the vicinity of Great Rock Bight shows the steep cliffs composed of unsorted glacial debris being slowly eroded.

Boulders and stones are exposed and sit on the surface as “erratics” or fall to the shoreline, creating very interesting beach and water features. The North Shore moraine is also a source of clay deposits that once supported a brick-making operation. The chimney of the brick kiln still exists, and you can see it from the Menemsha Hills Reservation. The upland forests also provided wood to fire the kiln and were extensively cut for this purpose.

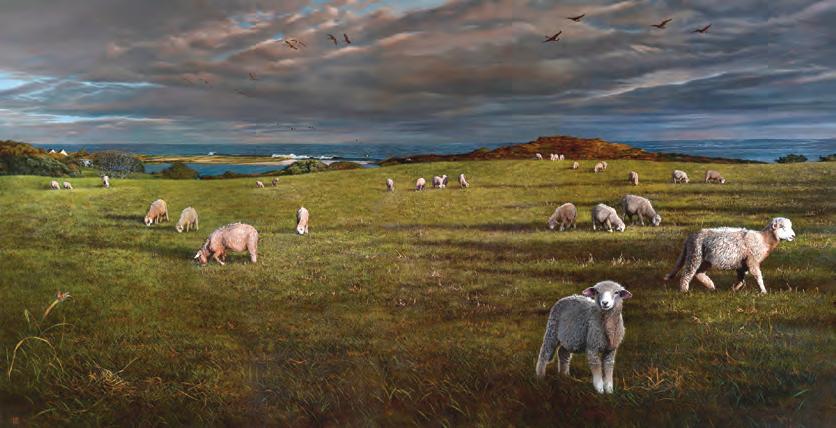

Meadow grasses are a resilient vegetative cover in a harsh maritime environment. These meadows can be a beautiful interlude in the more “scruffy” coastal heath and brush landscape. Human recreation, birdlife, and fauna also benefit from grasslands, whether they are managed by mowing or, occasionally, by controlled burns.

The multi-colored silts and clays of the cliffs around Wequobsque and Aquinnah erode to form sections of beach that depart from the white “sugar” sand of the barrier beaches or the brown beaches at the base of eroding cliffs of the North Shore morainal uplands.

The coastal uplands in the area of Stonewall Beach and the Allen Farm in Chilmark provide spectacular vistas that have drawn tourists and artists for centuries. These uplands are part of the glacial

moraine deposits that form the “spine” of the Island. Moraine deposits are the result of the dumping of the unsorted glacial load of boulders, rocks, cobbles, sand, silt and clay when the ice advance stagnated. The resultant rolling, rocky landscape was difficult for planting crops, but early occupants found that grazing livestock, particularly sheep, could be profitable. As erosive forces proceed, the heaviest constituents of the morainal deposits (rocks) remain in place while sands, silts and clays may be washed out to sea, leaving a very stony beach and plenty of boulders for stone wall construction.

Coastal ponds, particularly the Great Ponds located along the Island’s South Shore, are unique and dynamic features on the Vineyard landscape. They formed in low-lying sloughs and channels in the outwash plain to the Wisconscian sheet. These ponds range in salinity from freshwater to brackish and occasionally saline when the ponds are breached by natural storm-driven or man-

made openings. This range of salinity creates conditions that sustain an abundance of plant, animal, and, particularly, avian life. The ponds are separated from the powerful waves and currents of the Atlantic Ocean by barrier beaches and dunes that act as soft shock absorbers to the ravages of inexorable erosion and storm events. Consequently, the ponds are ever-changing landscape features.

The great sand plains of Martha’s Vineyard are the result of outwash of sediments from the terminal moraine of the last glacial advance. Sediments from lodge rocks and cobbles to gravel, sand, silt and clay were sluiced off the massive dump of moraine by torrents of meltwater as the ice sheet stagnated and then began its northward retreat. These sediments

were sorted by virtue of grain size and water velocity and later re-worked and capped by fine materials deposited by strong “katabatic” winds in the immediate post glacial period. These dynamic forces resulted in an expansive nearly level plain that is unique to New England. Some of the Island's best “tillable soils” are found on this landscape feature.

“Nowhere in the world is there a place more beautiful than this.”

– Alfred Eisenstaedt

The relative tranquility of the salt pond environment allows the development of significant, stable marsh grass habitats that serve to physically

protect the shoreline, remove nutrients that might otherwise harm the pond and provide nesting and food source for numerous forms of wildlife.

In the nineteenth century, landscape painting ignited the conservation movement. On Martha’s Vineyard, our artists inspire us to become better stewards of our lands.

By Hermine Hull

Artists create the visual record that has preserved our landscape.

That thought was in my mind as I began to write this essay. Throughout art history, artists have given us a continuum of pictorial and philosophical description. Certainly before cameras, when artists were sent out to explore the countryside or the

continent, they were expected to return with images of what they had seen. There were etchings or lithographs of country scenes. There was the grandiose wilderness of the nineteenth century Hudson River School, which many credit with inspiring the conservation movement.

I had never been a landscape painter before moving to West Tisbury. My

house is surrounded by woods that I look at every day. The first spring I noticed shadbush blooming in delicate white puffs through the still-bare trees, I was enchanted. I had always painted still life compositions set into interior scenes, often with friends modeling for me, but landscapes began to intrigue me.

My friend, Bill Ternes, had been coming for years to lead plein air painting

workshops on the Island. It was easy to go out painting with him and his group. I had a lot to learn. Landscape painting, especially outside, is a whole different set of skills.

What makes an artist choose a landscape to paint? What is it that attracts an artist to a particular place? What makes it endlessly interesting? I can only speak for myself and tell my own story, although it is probably similar to what others would say.

The Island is endlessly beautiful, an abundance of riches. For me, it is as simple as looking out my windows, walking my dog, driving around on errands or down dirt roads. It’s the dailyness, the observation again and again, arranging compositions in my mind. I am attracted by colors and big shapes, interwoven patterns of light and shadows. Those are ever-changing, endless

For me, it is as simple as looking out my windows, walking my dog, driving around on errands or down dirt roads. It’s the dailyness, the observation again and again, arranging compositions in my mind. I am attracted by colors and big shapes, interwoven patterns of light and shadows.

variations as daylight and the seasons progress. I like this quote from Ursula LeGuin: “Magic can be the fall of light on a place.”

The rhododendron hedge I planted when we moved here has grown into a thicket, the edge between open lawn

and our woods. I watch the earliest progression of coloring buds on spring mornings with skies of palest peach, the shapes of the spaces between branches and heavy trunks of oak trees. By the end of an afternoon, much of the woods will have flattened to deepening shade,

ochre runnels of cut hay that are bound into square or round bales, fields washed orange and purple by summer sunsets, fading to paleness in autumn, turning into twisting, wind-lashed wildlands in a winter storm. For artists who paint animals and farmers and fishermen working, opportunities abound. Our history as a farming community is important to preserve.

Paintings have their stories to tell. The Mill Pond, Parsonage Pond, Lobsterville, Mermaid Farm, Flat Point, Hancock Beach, Lucy Vincent, Quansoo, Red Beach, Polly Hill’s, Sepiessa, Sengekontacket, Moshup Trail, all those fields, all those marshes, all those walks through woods, and along the great ponds with their finger coves. So much to catch an artist’s eye. It always amazes me that a hundred painters could stand on the same

Hayfields, too, with their mounding hedgerows newly greening in the spring, ochre runnels of cut hay that are bound into square or round bales, fields washed orange and purple by summer sunsets, fading to paleness in autumn, turning into twisting, wind-lashed wildlands in a winter storm.

just the remains of daylight picking out patches of bark and leafy haloes. The sky will disappear for the summer once the leaves come out.

Then the marshes draw my attention. Water rising and falling, changing and redefining their edges. Spring rain fills tidal pools that disappear by summer. Sometimes, darkened, watery depths shoot right up the center of my composition, a contrast to brilliant green grasses, mud flats, lavender and blue-green marshes, all windblown. Other days, those same views rearrange themselves in flattened stripes of land, an odd tree making the only vertical to be seen.

Hayfields, too, with their mounding hedgerows newly greening in the spring,

spot and paint a hundred different paintings.

I think about the views that earlier generations of painters chose. There wasn’t much in the way of landscape painting here on the Vineyard before the late nineteenth century, when genteel ladies came in the summer to paint Island scenes, some of them quite good. The real influx of summer artists began in the 1920s and 30s, when a more bohemian cohort arrived in Chilmark, attracted by cheap rents, free or cheap food, sparse landscapes and beaches, and evenings filled with music, alcohol, and intellectual discussions. Thomas Hart Benton painted lush paradises or spare farmlands in which his characteristically stylized figures and animals worked in silence. Julius Delbos painted Edgartown and Menemsha harbor scenes on perpetually sunny days. Percy Cowen’s sheep farms with their rolling hills, broken brushwork, and brilliant skies provided an inspiring tutorial for his grandson, farmer and landscape painter Allen Whiting.

One of the first Island painters I met when I arrived here in 1982 was

Nancy Furino. Her work was strong and colorful, an interesting combination of recognizable places and energetic, descriptive brushwork that danced and raged across the canvas. The sun felt hot in Furino’s landscapes. The wind blew through them, roughing up waves or hayfields and marsh grasses. Her skies were never merely blue; they were intensely cobalt or violet or viridian. She used broad strokes of many colors laid beside one another, brilliant green, red, purple, ochre, combinations of

complementary or analogous colors that gave her paintings an energetic surface. For all the abstract qualities she employed, her landscapes were of the Island.

Rez Williams was another artist who translated what he saw into something more than a representation of what was in front of him. His paintings broke apart the vision of a traditional landscape into stylized shapes and patterns of his imagination, rendered in colors the painting called for, rather than the expected local color.

There is a wonderful story about Wolf Kahn, who occasionally painted on the Vineyard, and Fairfield Porter, two of my favorite painters. Kahn was visiting Porter at his summer home on Great Spruce Head Island off the coast of Maine. Porter was struggling with a boat tied to a pier, trying to integrate the boat into his composition. Kahn said to him, “Just leave it out.” To which Porter heatedly replied, “You don’t understand what I do.”

There are many opinions about whether a landscape painter should work on site or from drawings or photographs or memories in the studio. Ask a plein air

painter and he or she will say, “An artist must be in nature to truly understand it.” A studio painter will offer a different perspective: “An artist must reflect on the experience and refine it in the studio. It is not the relentless slavery to what is there that makes art; it is the artist’s interpretation, what is left in and taken out to render the most perfect distillation of what is seen.” Most landscape painters have done both and made their choices. Artists were unable to easily paint outside until the mid nineteenth century, when paint pre-mixed and put into tubes became available. The French

Impressionists were the first. Leslie Baker often said to me, “Painting a landscape is recording a moment in time.” I think of that a lot, looking at the changes on the Island over the years. Leslie and I had painted

along the south shore looking into Chilmark Pond just before Hurricane Sandy; when we went back after the storm, it had all been washed away. Liz Taft painted the iconic clay headland at Lucy Vincent before it collapsed and washed away. Parsonage Pond has become a flowery marsh, but it remains a pond for all time in Allen Whiting’s paintings and in my own.

A good landscape painting can transcend the simple reproduction of a place, inspiring viewers to preserve the Island's visual and ecological treasures. An unobstructed view. A stormy day or a placid one. Wind rushing through a hot, summer field. An opening beyond a woodland that draws a viewer to wonder where that pathway goes.

Conservation, preservation, the care and stewardship of our Island views and values, our traditions, our community, our history. That is what most of us care about. Art maintains these values. All contributions matter, and all contributors. Our goals are the same.

The writer has been an artist on Martha’s Vineyard since 1982.

Leslie Baker often said to me, “Painting a landscape is recording a moment in time.” I think of that a lot, looking at the changes on the Island over the years.

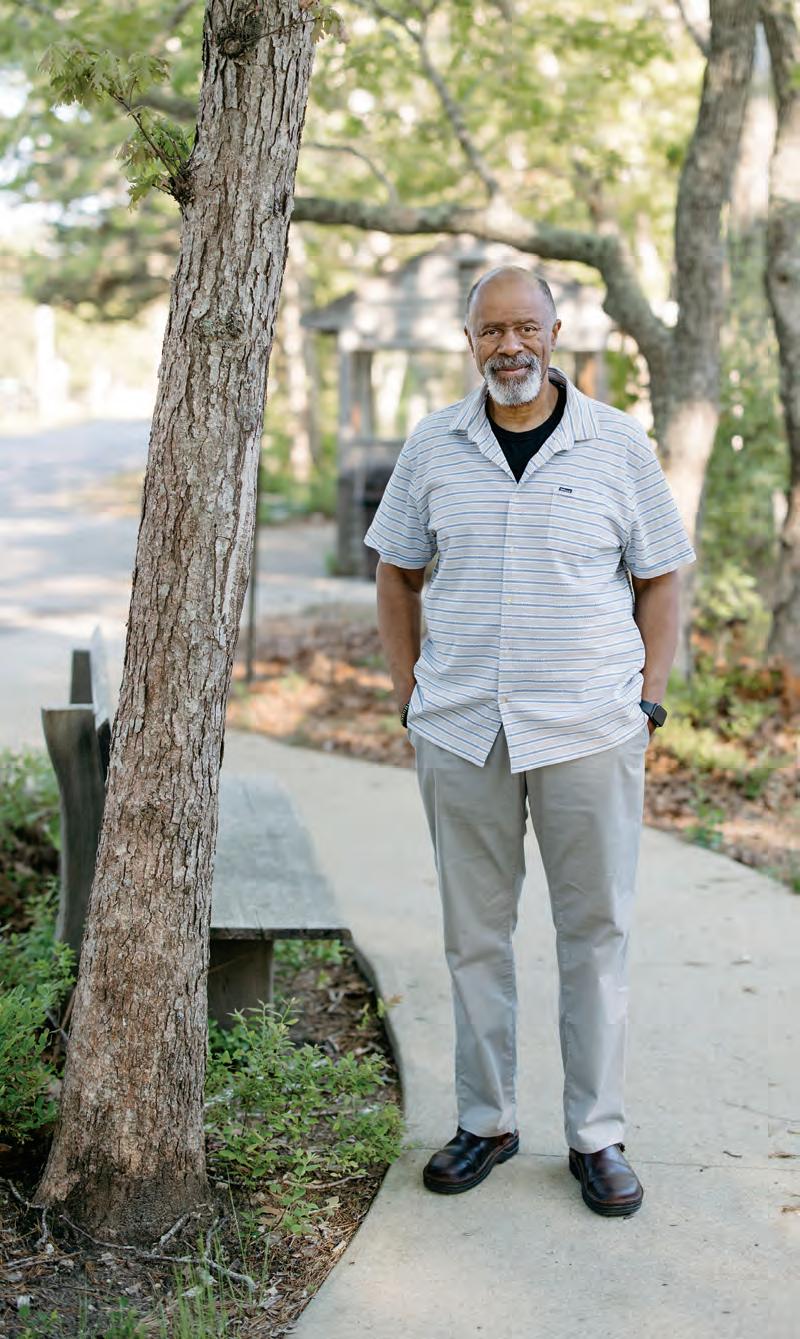

A conversation with David Foster about the past and future of landscapes on Martha’s Vineyard.

David R. Foster was the director of the Harvard Forest, a 4,000 acre field laboratory in Petersham, Massachusetts, from 1990 until 2020. As an ecologist and forest historian who is also a Vineyard resident, he’s a keen observer of this landscape’s past, present, and possible futures. You might know his book, A Meeting of Land and Sea: Nature and the Future of Martha’s Vineyard (see page 48), for its deeply textured profile of the Island’s ecosystems and human history, and for its coffee-table illustration and readability.

In 2005, Foster helped found Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands & Communities (wildlandsandwoodlands.org), an organization which set ambitious targets for forest conservation in New England. In 2017, their goal became even more ambitious: protecting 80 percent of New England by 2060, in a mixture of strictly protected wildlands, productively-managed woodlands, and working farmlands, a mosaic landscape intended to support people and nature. (Visit the dashboard on their website at bit.ly/WildlandsProgress to see where we stand now and find land use breakdowns for each state.)

This vision calls not only for accelerating the pace of conservation, but for setting aside at least 10 percent of New England as wildlands, protected in perpetuity and with strict limits on management by people. Under the definition Foster laid out, wildlands currently make up just 2 percent of the landscape in Massachusetts; on the Vineyard, despite 40 percent of the land being in some form of conservation, there are none.

I spoke with Foster about the future of Vineyard landscapes, and what the WWF&C vision might look like on the Island.

Interview edited for brevity and clarity.

Sam Moore: Can you give us a broad overview of Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands and Communities?

David Foster: Wildlands and Woodlands initiated out of a recognition that very few planning agencies, conservation organizations, or state leaderships actually define where they're headed or what their goals are. And this is especially true in terms of land protection goals. Most of these groups are trying to protect more land. But what does that mean? What's the vision that ties land protection together with, for example, land use planning? Without that kind of thinking, there wouldn't be a way to balance the different uses of the world out there. We started in Massachusetts with much more of a focus on forests. But over time we ended up developing not just a vision for the forests of Massachusetts, but a vision for the entire landscape of New England that tried to integrate land conservation and planning. When you first state those goals, conserving 50 percent of Massachusetts in forest or conserving 80 percent of New England in forest, they sound bold. But when you look at them from the other perspective: how much of Massachusetts would

you like to see developed? And how much of New England would you like to see developed? It turns out that they actually are quite reasonable.

SM: Martha’s Vineyard has more land conserved by percentage than many other communities, but is still facing substantial development. Could you talk about the status of conservation on the Island and how that relates to the Wildlands and Woodlands vision?

DF: We love the natural landscape of the Vineyard. We love the cultural landscapes, the farming landscapes, and other places that have been intensely shaped by people. And we need to have places to live. So what is that mix?

For a very long time, conservationists and others have been suggesting that we should define those limits. What is the capacity of the Vineyard, how do we define that through planning, and how do we reinforce that through conservation?

You want to conserve the forest. It probably makes sense to conserve a lot of it as wildlands, where you're just letting nature prevail, because that's the most efficient way to do things like store carbon and grow big trees and diversify the landscape. And then there’s the need to manage some of that for diversity, and for aesthetics, and a variety of other things.

The Vineyard has also been successful in developing remarkable farm communities. Farming actually ties into conservation objectives really strongly, and farm landscapes are tremendous places to breed biodiversity in nature. So clearly there's a big role for farming.

And then you have to plan your communities. So those are the three big elements, right? Forests, farms, and communities. If you're actually going to define what the remaining naturalized and cultural landscape would look like on the Vineyard, you want to define that now, because development is proceeding rapidly.

SM: I just read the 2023 Wildlands Report (bit.ly/ NEWildlands) that you co-authored. Could you talk about working forest lands as part of that landscape mix, and how that applies to the Vineyard?

DF: Our idea right from the beginning was that forest protection was essential because forest is the natural state of most of New England. But you can't talk about either preserving forests as guided by nature in wildlands, or conserving forests to be used in different ways to produce products, without talking about the other. They're kind of like the yin and the yang, and they're mutually supportive.

You've got cores of nature which are intact and not actively disturbed. And you want to buffer those from the developed world and the agricultural world with forests that are intact but are being used in a variety of ways. So you have this kind of gradient of use.

The Vineyard could make more use of its forests. There are a lot of people who continue to use wood for a variety of purposes, whether that's heating their homes or making boardwalks for Sheriff’s Meadow Foundation. You can do it in a sustainable way. You can do it in a way where people can hardly even tell that the forest has been managed. Yes, we are using resources. Those resources have to come from someplace. We better do a really good job of making sure we do that well. Everybody can benefit from understanding that our timber doesn't just come from Home Depot.

So I think there's a role for that — but there's a much bigger role for it off of the island. Wood has always been shipped into the Vineyard. You can go back to the earliest days of the Vineyard Gazette in the 1840s and find records of lumber being brought in from Maine.

SM: And in the Island’s case, maybe agriculture provides more of that working-landscape buffer around core areas of preservation.

DF: Yeah, that’s true. And it’s also true that in the history of the Island, there are a lot of areas that were never cleared, that were always kept in forest. I just came back from Seven Gates Farm, and there are trees there that are over 300 years old, and there are old forests that are just beginning to get into that very mature, almost-old-growth characteristic. But on the periphery of all of those areas are all these old farm fields that have been abandoned and have become forests. In a sense, those secondary forests provide a buffer to the agricultural lands or to people's backyards.

So I think there always will be that kind of tension zone, buffer zone, and that's one of the reasons that it's really important early on to define: what are your permanently preserved areas, where are your wild lands? And right now on the Vineyard, as you can see from that report, there are none.

SM: I spent a lot of time looking at your definition of wildlands, which I found interesting and a bit contrary to the kinds of active ecological restoration people may associate with conservation work.

(“‘Wildlands’ are tracts of any size and current condition, permanently protected from development, in which management is explicitly intended to allow natural processes to prevail with “free will” and minimal human interference. Humans have been part of nature for millennia and can coexist within and with Wildlands without intentionally altering their structure, composition, or function.”)

Could you talk a little bit about why most of the protected areas on the Vineyard might not qualify as wildlands?

DF: Everybody's familiar with, ‘we can buy a piece of land and conserve it. We can put a conservation easement on it and we can conserve it.’ But all that means is we're conserving it from

being developed. It doesn't mean that the forest couldn't be turned into a field, or the forest couldn't be actively managed.

The wildlands criteria say it's not a wildland unless there is a definite intent to make it a wildland. In other words, it’s an intent to allow the area to develop naturally with as little human impact as possible. And backing that intent up with a strict approach to conservation, either a conservation easement or bylaws establishing it, or some other guarantee that the management plan from this decade is going to work in the next decade and so on. And then there needs to be proof on the land that you're doing it. There are plenty of places on the Vineyard where people are not actively managing. And maybe they have decided they're not planning to manage, but they never made that intent known.

SM: One piece of your definition that I found really interesting is this concept of not managing in pursuit of a desired state, whether that's trying to reclaim a past landscape, whether it’s the pastoral Vineyard of yesteryear, or some imagined landscape in the future.

DF: Yeah, that's key. The test is: did they try to move the landscape in any particular direction? I benefited incredibly by reading this interagency wilderness group that works in the federal government and has spent decades on these issues. That's where I came up this notion, which I think makes great sense, which is: if you're trying to maintain a rare species, or inhibit another species, or if you're trying to selectively increase one thing over another, or trying to make it more healthy by doing this, that, and the other thing — you are trying to impose your

own values and your own future onto that landscape. That's when it stops becoming a wildland. And that's not bad, as long as you recognize that and are comfortable with it.

SM: For example, if we look at the state forest on the Vineyard, which you don’t consider a wildland, compared to the state forests out in Western Massachusetts that you do — what's the distinction?

DF: The big distinction is intent. The Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation has management plans for every forest and all of its forest reserves. There's a long history in most of those areas of not being managed, and people recognizing they are really special and we need to leave them the way they are. The only two that call for active management are Corellus and Myles Standish. The state would like to manage them, they'd like to burn the scrub oak, they'd like to manage the forests to make them more diverse. They would love to do more, and the fact that they haven't managed the landscape much so far doesn’t make it a wildland.

If you look at some of the really beautiful sand plain forests across Massachusetts, most of them have been really actively managed now by the Division of Fisheries and Wildlife or by DCR for habitat, for their idealized thought as to what that should be.

So the point is, on the Vineyard no one has yet stepped forward and said, okay, we don't intend to manage our forests, and we're not going to manage in the future. They haven't done that and maybe they won't, because they worry about the future and want to have their options.