MARTHA’S VINEYARD / LATE SUMMER 2023 SIMPLE / SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES AN ODE TO GLORIOUS LOCAL FOOD FISH FOR ALL A Conversation with Bill McKibben · Local Hero: Rebecca Haag · Saving Chilmark Pond TM CORN! Sweet, sublime, complicated @bluedotlivingmv Salads from Island Harvests Noah Mayrand, Oyster Farmer FORK TO PORK A Righteous Circle FARMS & FOOD

BDL 1 marthasvineyard. .com

President Victoria Riskin

CEO Raymond Pearce

Editor Jamie Kageleiry, editor@bluedotliving.com

Senior Writer Leslie Garrett

Associate Editor Lucas Thors

Copyeditor Laura Roosevelt

Creative Director Tara Kenny

Design/Production Whitney Multari

Digital Projects Manager Kelsey Perrett

Digital Assets Manager Alison Mead

Social Media/Digital Projects Julia Cooper

Contributing Editors Mollie Doyle, Catherine Walthers

Ad Sales Josh Katz, adsales@bluedotliiving.com

Contributors, this issue Randi Baird, Irina Bezumova, Annabelle Brothers, Daniel Cuff, Jeremy Driesen, Sarah Glazer, Sheny Leon, Laura Roosevelt, Catherine Walthers

Bluedot and Bluedot Living logos and wordmarks are trademarks of Bluedot, Inc.

Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.

Bluedot Living: At Home on Earth is printed on recycled material, using soy-based ink, in the U.S.

Bluedot Living magazine is published quarterly and is available at newsstands, select retail locations, inns, hotels, and bookstores, free of charge. Please write us if you’d like to stock Bluedot Living at your business. Editor@bluedotliving.com

Sign up for the Martha’s Vineyard Bluedot Living newsletter here, along with any of our others: the BuyBetter Marketplace, our national ‘Hub” newsletter, and our soon-to-be-launched Bluedot Kitchen newsletter: marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com/sign-up-for-ournewsletters/

Subscribe! Get Bluedot Living Martha’s Vineyard and our upcoming Bluedot GreenGuide mailed to your address. It’s $24.95 a year for all four issues plus our Green Guide, and as a bonus, we’ll email you a collection of Bluedot Kitchen recipes. Subscribe at bit.ly/MVBluedotSubs

Read stories from this magazine and more at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

Find Bluedot Living on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube @bluedotliving

2 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

BDL • OUR TEAM

• • • • • •

Your Renewable Energy Solution Solar, plus smart, safe and long-lasting battery technology. Power your home with clean energy around the clock with solar and batteries. www.fullers.energy 508.696.3006 info@fullersenergy.com

“ Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. On it everyone you love .” –Carl Sagan

Dear Readers,

“The scent of wild blueberries, sweet and mingled with a humusy musk from the dirt that sustains them, wafting through the woods on a humid afternoon …” writes Laura Roosevelt in her ode to eating what’s grown in your backyard, or picked up at a nearby farm, for this issue dedicated to the bounty of Martha’s Vineyard. “Wild blueberries, like the ones my mother and I would pick together almost daily during that summer when I was eleven.”

I hope most of us have those memories: The burst of sweet summer corn in our mouths, an explosion of velvety tomato, a briny oyster, or fish right off the boat. Our Local Hero for this issue (who else could it be but Rebecca Haag, Executive Director of IGI?), says about food: “It is also love, it is family, it is community, it is tradition and history.”

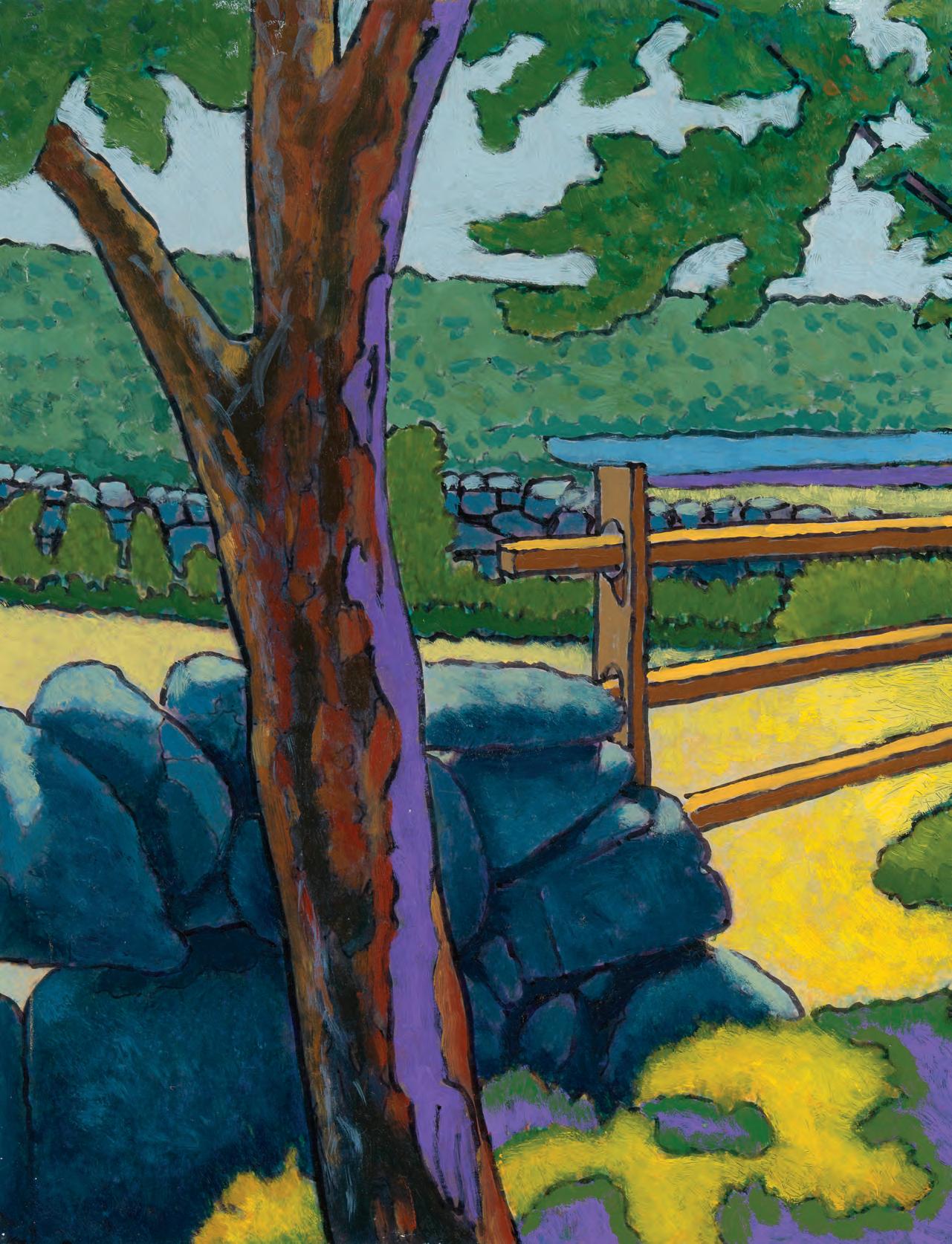

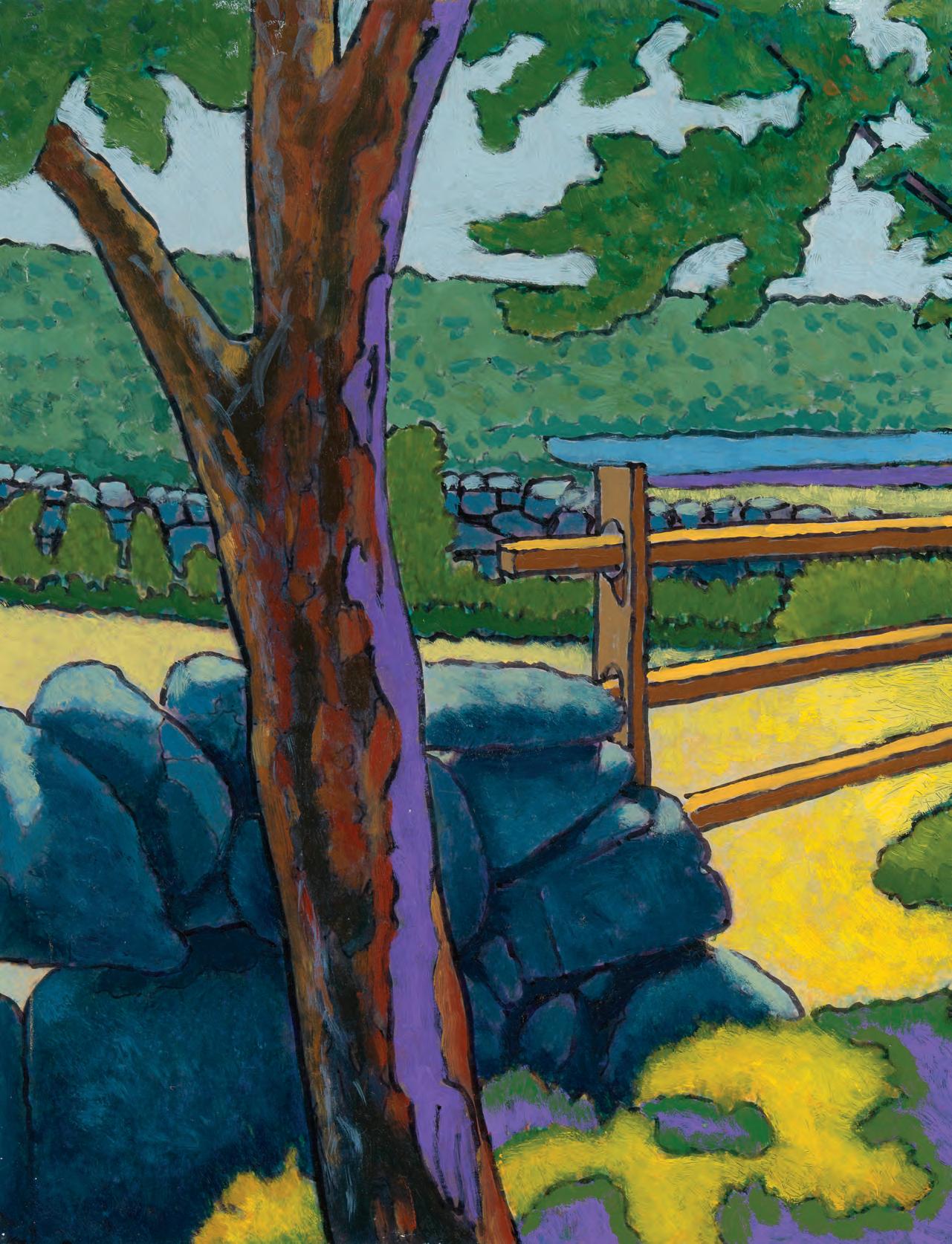

We’re celebrating this abundance with the art of farms and food — gorgeous photographs by Sheny Leon of the sweet corn harvest at Morning Glory Farm; paintings and drawings from Martha’s Vineyard Hospital’s Permanent Art Collection (thank you to the hospital, and Monina von Opel for curating this); Randi Baird’s lovely images of oyster farmer Noah Mayrand visiting his beds in Lagoon Pond. That

story, by the way, was written by MV Regional High School graduate (and Bluedot Institute intern) Annabelle Brothers.

We love Jo Douglas’s Fork-to-Pork program: She collects food waste from Island restaurants, feeds her passel of pigs (sometimes with Back Door Donuts to their delight); then when it’s time for the pigs to become food, she brings, say, a pork loin, or a pork belly (or both) back to a restaurant. (See the recipe for Pawnee House’s Italian Porchetta on page 31.)

It’s a sweet, “righteous” circle of life, like so much of the food system on Martha’s Vineyard.

3 marthasvineyard. .com EDITOR'S LETTER

PARAMOUNT COW IN FIELD BY WENDY JEFFERS

COURTESY THE MARTHA’S VINEYARD HOSPITAL PERMANENT ART COLLECTION

(508)627-2928 | MV@oh-DEER.com

oh-DEER.com/locations/MV

Reader Jack Connell wrote about Mollie Doyle’s story on induction ranges: "I'm a bit of a blend of energy geek and marketing guy and try to refrain from offering advice unless I really like what I'm seeing — and Blüedot is a somewhat recent discovery for me. Thank you for all you're doing in bringing energy advice to everyone, residents, and visitors alike.

"It’s with that respect for what you’re doing that I might, from time to time, chime in with a technical correction if I think it’s important. The recent email article about induction stoves by Mollie Doyle was very well written and makes a very compelling case (we just replaced our gas stove with induction at home, before heading to the Vineyard for the summer). The statement, ‘My mom’s induction stove is fueled by the solar panels from her roof. If you install an induction stove but do not have solar, there is a good chance you will still be using fossil fuel-based energy to power your electric range.’ is partially correct, but makes it sound like induction is not a good idea without solar on one’s roof. In fact, our electricity on the Vineyard is, on average, produced by about 43% non-carbon sources so the conversion from LP to induction does help, a lot. (Ref: EPA eGRID Power Profiler for 02539)."

• SAFE FOR YOU, YOUR FAMILY & PETS!

• KILLS TICKS & MOSQUITOS ON CONTACT.

• AN EFFECTIVE ‘GREEN’ ALTERNATIVE TO PESTICIDES & CHEMICALS

ohDEER offers you and your family a proven and safe solution to control ticks and mosquitoes so that you can enjoy your yard. Our products are true all-natural repellents that contain no pesticides or chemicals of any kind.

Thanks, Jack! We invite anyone to write to us with corrections, ideas (or praise!). I’m at editor@bluedotliving.com.

We so appreciate our readers (subscribe here to have the magazine mailed to you: bit.ly/MVBluedotSubs), and our newsletter subscribers (you can sign up here for that: bit.ly/MV-NEWSLETTER) for continuing to support our mission to bring you local, solutions-focused climate stories. (You can contribute here: marthasvineyard.bluedotliving. com/become-a-member/)

Bon Appétit!

–Jamie Kageleiry

EDITOR'S LETTER 4 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023 DEER, TICK & MOSQUITO CONTROL!

ENJOY MORE TIME OUTSIDE!

PEARS AND APPLES BY THAW MALIN COURTESY THE MARTHA’S VINEYARD HOSPITAL PERMANENT ART COLLECTION

– Laura Roosevelt

ANDREW WOODRUFF BY BRUCE DAVIDSON COURTESY THE MARTHA’S VINEYARD HOSPITAL PERMANENT ART COLLECTION

BDL 5 marthasvineyard. .com

There’s nothing quite like eating a vegetable that was picked twenty minutes ago.

Art this page: “Tractor,” by Terry Crimmen

Art on opposite page: “Sunset Through the Barn,” by Thaw Malin, Courtesy of the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital

Permanent Art Collection.

BUILT FROM SCRATCH • FEATURE 6 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023 Baird

19 A Climate Conversation With Bill McKibben

By Leslie Garrett

By Leslie Garrett

Upfront Find this magazine online at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com Subscribe! marthasvineyard.bluedotliving. com/magazine-subscriptions/ Cover photograph: Seneth Waterman at Morning Glory Farm, photo by Sheny Leon

During a recent visit to the Island, the longtime climate activist spoke to Bluedot editor Leslie Garrett about “Third Act,”

50 Noah Mayrand: He’s Farming Oysters to Feed an Island

By Annabelle Brothers

And helping make our ponds healthy.

38 What’s So Bad About Corn?

By Leslie Garrett

Local corn on the cob is the sweet summer perfect treat — just check out the crowds around the bins at Morning Glory Farm. But the glorious, sublime crop is also … complicated.

54 Saving Chilmark Pond

By Sarah Glazer

Abel’s Hill neighbors rally to reduce fertilizer use, and help create a blueprint for restoring pond health.

Departments

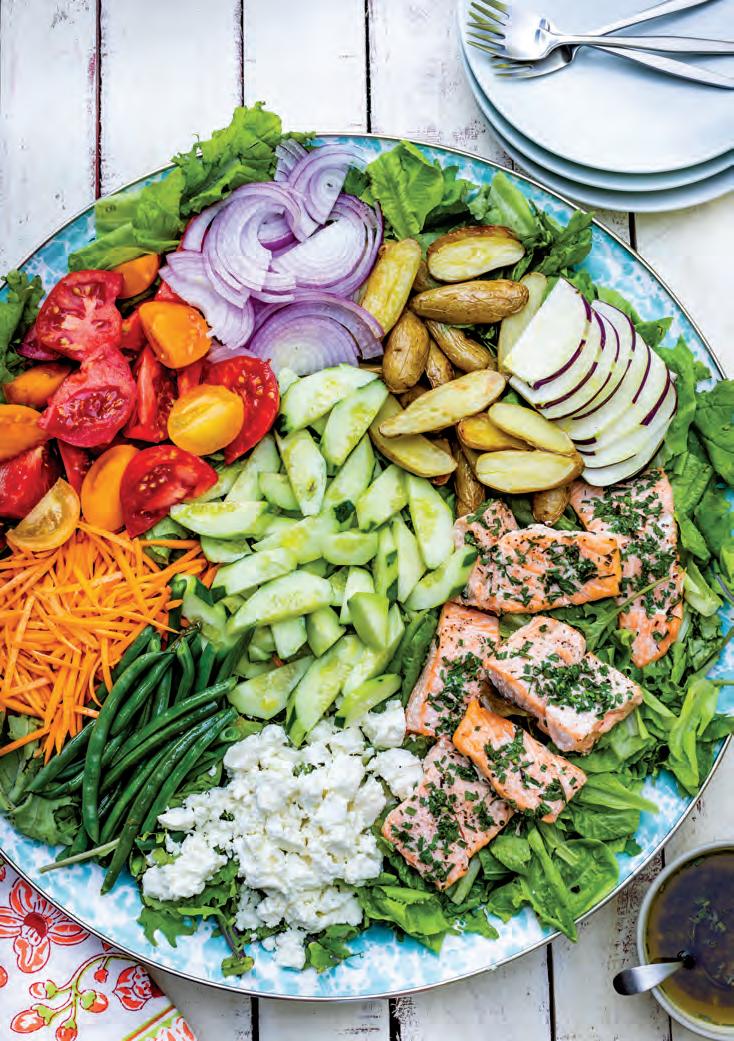

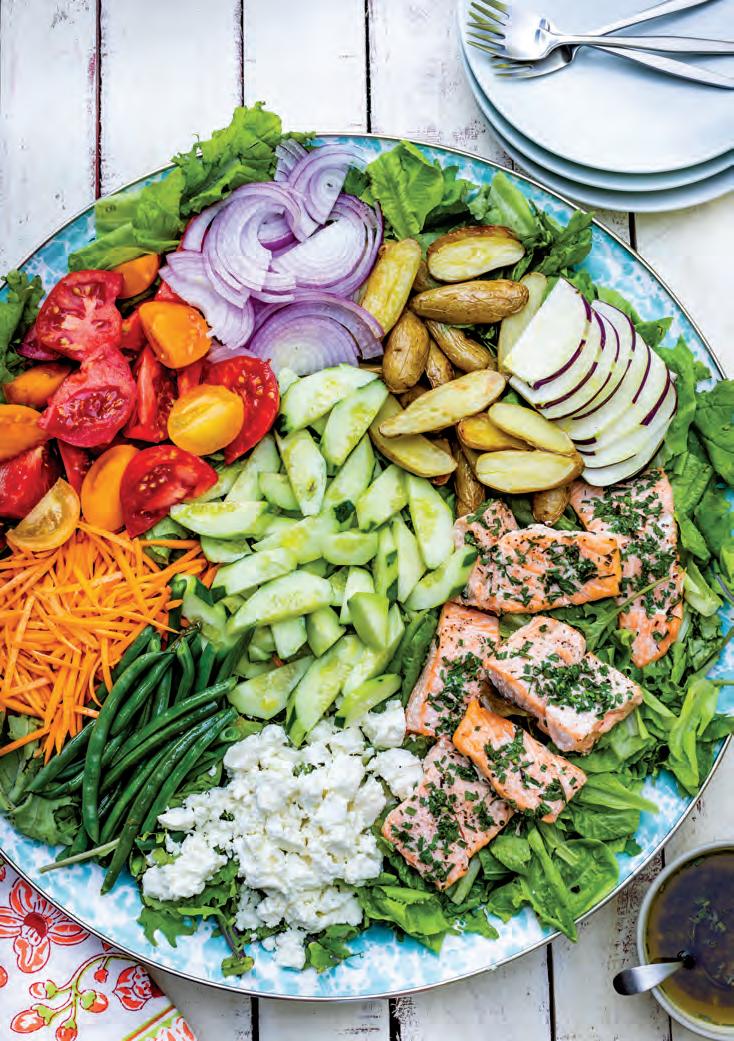

46 The Bluedot Kitchen: Dinner Salads!

Editor Catherine Walthers celebrates the bounty of Vineyard summer.

50 Garden to Table: Keeping Your Tomatoes Free of Pests

By Laura D. Roosevelt

Harvest now to eat all winter.

64 Local Hero: By Lucas Thors

We Nominate Rebecca Haag.

To the IGI chief, food is more than just nutrition: “It is also love, it is family, it is community, it is tradition and history.”

FEATURE • BUILT FROM SCRATCH

Our Team 3 Editor's Letter 4 The MV Fishermen’s Trust Community Supported Fisheries Program

Field Note:

With

What.On.Earth:

of

CONTENTS 2

12

IGI’s Reduced Tillage Project

American Farmland Trust 14

Pick

the Crops 16 In a Word: Speciesism

his new organization for climate warriors over age 60. 22 Essay: Loving Local Eating

Roosevelt’s ode to our local veggies, fruits, chickens, and fish (“flavor that spoke of whitecaps and seaweed and beams of sunlight …”) 28 Fork to Pork

Daniel Cuff

Douglas closes the “beautiful, righteous circle” that combats food waste. With a Pawnee House porchetta recipe.

Laura

By

Jo

Features Newsletters to sign up for The BuyBetter Marketplace: Bluedot’s picks of planet-friendly products Your Daily Dot (daily Dot musings, Climate Quick Tips, and Dot answers your questions — right to your inbox) Sign up for both here: /bit.ly/BDL-newsletters

of the Day Sharing the Catch

Story and Photos By Lucas Thors

At the top of the list of all the attractions that draw visitors to the Vineyard from around the world — up there with the Island’s picturesque beaches and laidback, take-your-time atmosphere — is our seafood. It’s so fresh: A hungry market-goer looking for some lobster or scallops could arrive in Menemsha at the same moment the boat that caught the bounty is pulling away from the dock.

The Martha’s Vineyard Fishermen’s Preservation Trust (MVFPT) and the Martha’s Vineyard Seafood Collaborative are offering a new way for people to purchase fresh seafood directly from local fishermen. The newly established Community Supported Fishery (CSF) program is aimed at providing direct-to-consumer access to the freshest seafood available. At the same time, anyone who buys into the opportunity can be assured that they are bolstering the Island economy and significantly

reducing the carbon footprint caused by shipping fish off-Island. According to Phoebe Walsh, operations manager for the Martha’s Vineyard Seafood Collaborative, the project started

Support Bluedot!

We love bringing you stories about Islanders addressing climate change. Generous contributions from readers such as you helps us do this. Make a one-time, monthly, or annual contribution here.

THE CATCH OF THE DAY • UPFRONT 8 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

we’ll email you a downloadable collection of Bluedot Kitchen Recipes

And

Phoebe Walsh, left, and Adelaide Keene work at the Seafood Collaborative booth at the Farmers Market.

with a small winter CSF as a pilot to see how the community responded. “People were really excited, and we felt like a direct-to-consumer model would help bring in money to keep the [CSF] operation going,” Walsh says. She explains that the CSF initiative is based largely on the Community Supported Agriculture model — the up-front CSF fees help get the program going early in the season and enable the trust to buy fish from fishermen before the summer’s increased demand.

Of course, the CSF includes all the delicious scallops, bluefish, and lobster folks might want. But it also provides members with many other fish and shellfish species that are equally healthy and tasty, including sea bass, scup, and other finfish that are often underutilized in restaurants and family kitchens. “And that’s one part of the education component,” Walsh explains. “So much of this fish goes to waste because people might be unfamiliar with it.” During the planning phase of the project, the CSF team discussed how they could balance the price to make fish affordable and accessible for the Island, but also support local fishermen.

A summer membership can begin anytime June through August and includes three monthly pickups. A fall membership runs September through October and includes two monthly pickups. Seasonal memberships come in small and large sizes, priced at $345 and $675 for sum-

UPFRONT • THE CATCH OF THE DAY 9 marthasvineyard. .com

CSF bundles are a great option for people who aren’t very comfortable with cooking fish, since the MVFPT provides recipes and meal ideas to those who pick up. But the program is also great for the serious chef looking to try something new.

mer and $230 and $450 for fall. A large share includes sixteen to twenty servings of locally caught seafood per pickup (enough for four people to eat once a week, for four to five weeks, so between $11 and $14 per serving). A small share includes eight to ten servings of locally caught seafood (enough for two people to eat once a week, for four to five weeks, so about $11 per serving.)

Although it’s a sizable upfront cost, Walsh said she hopes people appreciate the value they get from the CSF program when they break down the membership on a per-serving basis. “Plus, look what you are getting — very high-quality seafood that is freshly flash frozen and caught by people right here on the Vineyard,” Walsh says. “At the same time, people who aren’t able to commit to that larger sum [can still] buy a little bit at a time and get some of the more affordable options like scup or sea bass.”

This is the first year that the MVFPT has been able to sell fish at a true retail location, and Walsh says the West Tisbury Farmers Market seemed like a sensible option. It’s more convenient for many Islanders than their home base in Menemsha, and it encourages seafood customers to also peruse the rest of the Market’s Island-grown wares. “People seem to really be enjoying it already,” Walsh says, “and it’s fun to provide that connection to food.”

She adds that CSF bundles are a great option for people who aren’t very comfortable with cooking fish, since the

MVFPT provides recipes and meal ideas to those who pick up. But the program is also great for the serious chef looking to try something new. “We have everyone from people who are brand new to cooking fish, all the way to professional, very experienced cooks that want access to high-quality fish in order to broaden their culinary horizons a bit,” Walsh says.

Shelley Edmundson, MVFPT executive director, says that

THE CATCH OF THE DAY • UPFRONT 10 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

Striped bass ready to be processed, filleted, and flash-frozen.

BY SARA CANNON

during their normal operations in the wholesale fish market, a lot of seafood was being exported, and the economic advantage of selling fish locally was being lost.

“The idea of having a CSF kept surfacing,” Edmundson says. “We thought that was such a great way to get fresh catch to everybody, and to tell the story of the catch.” Although there were a number of regulatory barriers to work through and logistical challenges to conquer, Edmundson says that the effort was worthwhile, because getting fish directly to consumers isn’t something that fishermen can always do themselves.

The recent Farmers Market was a great test run, according to Edmundson. She calls the first CSF pick up a “major triumph” that proved the efficacy of their model and illustrated how much the community wants access to this kind of food. She also reiterated that the program will be running through the fall (with pickup continuing at the Farmers Market), so people should look into purchasing their fall shares soon.

Just as a fruit or vegetable that is an odd shape, size, or variety might get passed over in a grocery store, Edmundson says that some sizes and species of fish are often overlooked by everyday shoppers and culinary experts alike. “Oftentimes, a restaurant just wants certain sizes of everything, but that’s just not how it works when you fish,” she says. “It leaves this whole pocket of misfit sizes and species that are otherwise not sold or not consumed.” The CSF program hopes to find a place for all that good food, so it’s not wasted and the fishermen can have a market for their entire haul.

For Edmundson and the rest of the MVFPT, connection to food and people is key. At the farmers market, shoppers or CSF members have access to a wealth of information regarding the boat the fish is from, how it’s caught, and how to prepare a delicious meal. “We want to get people hooked on this kind of food and this kind of awareness, so they can go to another market or restaurant and make those same choices,” Edmundson says. At the same time, she adds, participants and buyers can know exactly who pulled that fish out of the net or off the line. “You might pick up your package and put it in your cooler and see that it’s fish from Johnny Hoy’s boat,” Edmundson says. Eventually, the MVFPT wants to have a page where folks can see all the vessels that sell to the program, and can read their stories. “Who is working hard to catch what you are eating? It all makes buying and making great food a little more magical.”

Visit mvfishermenspreservationtrust.org/csf for more information on pricing, schedules, and more.

UPFRONT • THE CATCH OF THE DAY 11 marthasvineyard. .com Serving the Community of Martha’s Vineyard 1(833) MV SOLAR (687-6527) Solar System Installation New & Retro t Battery Storage Canopies & Pergolas Commercial & Residential

ILLUSTRATION

To: Bluedot Living

From: Island Grown Initiative

Subject: IGI’s Reduced Tillage Project With American Farmland Trust

In February of this year, Island Grown Initiative was chosen to be one of eight New England farms in the American Farmland Trust’s new Farm-Led Innovations in Reduced Tillage project. This program brings together farmers who are working to grow food using organic methods with minimal soil disturbance, to support peer-to-peer learning and spread these practices across farms in New England and beyond.

Regenerative farming, which prioritizes both environmental health and abundant food production for people, is not a new idea. This is the traditional

approach to farming that many indigenous cultures across the world have practiced for millennia. But today in our country, there are very few mid-scale farms growing vegetables without relying on heavy tillage or chemical inputs to prepare beds for planting, reduce weed pressure, and transition between cover crops and vegetable crops. By reducing tillage and forgoing the use of chemicals, these farms help support

healthy soils, the foundation for nutrient-dense food and biodiversity on working farmscapes. Because few farms are engaged in these practices at scale, there is limited access to commercial equipment for

IGI'S REDUCED TILLAGE • FIELD NOTE 12 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023 Native plant specialists and environmentally focused organic garden practices. Design • Installation • Maintenance (508) 645-9306 www.vineyardgardenangels.com Garden Angels Bring beauty to your property

FIELDNote

Low- and no-till practices produce healthier soils.

these growers, leading farmers like those at IGI to build custom tools or modify farm equipment themselves. There are also not many other growers to turn to workshop ideas, share challenges and successes, or spread innovations beyond individual farms. Enter American Farmland Trust, which put together this cohort of four Massachusetts farms and four Maine farms that now has been meeting regularly for six months. Each farm was granted $5,000 over two years to advance a reduced tillage project on their land. At IGI, regenerative farming consultant Andrew Woodruff customized a “zone tiller,” a machine that allows for minimal soil disturbance before planting. They are now using this equipment to plant fall brassicas, including cabbage, broccoli, and kale into cover crops with different types of field preparations to measure plant health and yields. They will be planting

into trial plots that have been prepared using tarps, rolled cover crops, compost applications, and organic fertilizer, gathering data about which practices work best to minimize soil disturbance while maximizing food production.

AFT’s aim is to help other growers

learn from these farmers’ innovations by hosting walking tours, publishing articles, and sharing videos. IGI’s walking tour will take place in early October. For more information, or to schedule a tour of IGI’s regenerative farm, please contact office@igimv.org.

LOCALLY GROWN. LOCALLY ENJOYED. breast-feeding may pose potential harms. It is against the law to drive or operate machinery when under the influence of this product. KEEP THIS PRODUCT AWAY FROM CHILDREN. There may be health risks associated with consumption of this ed by two hours or more. In case of accidental ingestion, contact poison control hotline 1-800-222-1222 or 9-1-1. This product may be illegal outside of MA. 510 State Rd, West Tisbury, MA 02575 • 508.687.0131 • finefettle.com WALK-INS WELCOME

Tim Connelly, IGI Farm Director, on a tractor with a zone tiller attachment built by Andrew Woodruff.

FIELD NOTE • IGI'S REDUCED TILLAGE

PHOTOS BY JEREMY DRIESEN

What. On. Earth. Pick of the Crop

Is it ever thus, at the end of things? Does any woman ever count the grains of her harvest and say: Good enough? Or does one always think of what more one might have laid in, had the labor been harder, the ambition more vast, the choices more sage?

—Geraldine Brooks, Caleb’s Crossing

1. Percent of carbon emissions globally from agriculture: 24

2. Number of dead zones in seas around the world due to agricultural runoff: 405

3. Percent of fertilizer lost into the air from each application: 40

4. Percent of the Earth’s ice-free land that is used for agriculture: 34

5. Percent of the Earth’s ice-free land that is urban: 1

6. Percent of the world’s agricultural land that is used for beef cattle: 60

7. Percent of the world’s calories provided by beef cattle: <2

8. Percentage of CO2 emissions sequestered by Earth’s forests, farms, and grasslands: 25

9. Percent of rural American farms operated by families: 98

10. Number of people one U.S. farm feeds (domestic and abroad): 166

11. Percent of U.S. grown food that never gets eaten: 40

12. Number of acres Morning Glory Farm plants in corn: 27.45

13. Distance that would cover if planted in a single row: 57 miles

14. Number of acres of corn and pumpkins Morning Glory has in no-till farming: 23

15. Percent of acres of crops at Island Grown Intiative’s farm that is planted using regenerative practices: 100

16. Gigatons of CO2 or its equivalent that must be reduced (referred to as the emissions gap) in order to halt global warming at 1.5 degrees celsius above pre-industrial levels: 23

17. Anticipated worldwide growth in acres in regenerative agriculture by 2050: ~900 million

18. Impact this growth could have on reduction of CO2 emissions in gigatons: 23.2 (thus closing the emissions gap)

WHAT ON EARTH 14 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

Sources: 1 EPA 2 NBC News 3 Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education 4, 5 Global Eco Guy 6, 7 Grazing Facts 8 UC Davis 9 USDA 10, 11 American Farm Bureau Federation 12, 13, 14 Morning Glory Farm 15 IGI 16 UN report 17, 18 Project Drawdown

BY JULES WORTHINGTON

WHAT ON EARTH 15 marthasvineyard. .com

BROOKSIDE FARM

COURTESY THE MARTHA’S VINEYARD HOSPITAL PERMANENT ART COLLECTION

Speciesism

Speciesism. Try to say that five times. Or once. It doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, does it? While it might sound a bit like someone speaking with marbles in their mouth, in fact, speciesism is more about someone with a chunk of cow in their mouth, or perhaps chicken, or octopus.

Or … not exactly.

As defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary, speciesism is:

• prejudice or discrimination based on species, especially discrimination against animals

• the assumption of human superiority on which speciesism is based.

Speciesism is a surprisingly new word — its first known use was in 1970. But speciesism as a concept has been around for as long as humans have, one surmises, and certainly for as long as we have felt ourselves superior to other species and therefore free to

eat, dominate, subjugate, or otherwise exploit them.

Indeed, speciesism is so ingrained in being a human that a word to define it hardly seemed necessary. It was just the way things were, integral to the survival of the one most equipped with tools and opposable thumbs, the one most hungry for a burger.

But speciesism is in plenty of people’s mouths these days — part of a philosophical discussion about our role in the planetary web, and the price the planet has paid for humankind’s domination. Perhaps no one has brought the concept of speciesism to public consciousness as much as Peter Singer, the moral philosopher and Princeton bioethics professor whose first book, Animal Liberation, published nearly fifty years ago in 1975, started a conversation around meat-eating and the farming of animals that hasn’t stopped since. (That book has been updated and reprinted; see below.)

His proposal was simple: Afford animals the same rights and consideration we offer ourselves. It isn’t so much the eating of animals that troubles Singer, it’s the suffering. And there’s no question that our industrialized farming of animals creates great suffering for them.

But while he thinks his views are morally correct, he doesn’t condemn those who don’t hold the same views. “I have lots of friends who eat animals,” he told a reporter for Vogue magazine. “You’ve got to accept that some people will be persuaded, and others will alter their consuming habits to some degree, but not as much as I would like. I don’t want to live in the ghetto of only people who think and act exactly like me.”

Rather, he urges all of us to think about what we put on our plates and how it got there, noting that “if everyone who now eats meat were to be genuinely conscientious, I would feel my battle on behalf of animals was 80 to 90 percent won.”

These days, with the recent publication of a new book, Animal Liberation Now, Singer’s motivations for encouraging a plantbased diet are no longer exclusively about animal suffering but also about the impact that eating meat has on our planet. If everyone on the planet replaced meat with plants for half the meals they eat, he wrote in a New York Times op-ed, “we would have fewer animals suffering, and a tremendously better shot at avoiding the most dire consequences of climate change.”

Leslie Garrett

16 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

in a word

spe·cies·ism 'spē-shēz-,i-zəm

ADVICE LOCAL NEWS FOOD/RECIPES CLIMATE NEWS HOME & GARDEN MARKETPLACE marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com MARTHA’S VINEYARD Sign up for our bi-weekly newsletter! SIMPLE / SMART SUSTAINABLE / STORIES

CHARY CHICKEN, WHITING FARM, BY LYNNE WHITING COURTESY THE MV HOSPITAL'S PERMANENT ART COLLECTION.

dot

Dear Dot,

I recently read that grass-fed beef is not better than grain-fed for greenhouse gas emissions and, in fact, may be worse. What does Dot know about that?

—Robert, Chilmark

Dear Robert,

What Dot knows is that, many years ago, after four years of a meat-free diet, I decided to re-introduce beef, but only from humanely-raised, grass-fed cows. Research at the time indicated that grass-fed cows farted less because grass was better for them and, therefore, methane emissions were reduced. (Our lovely Bluedot copyeditor urged me to use the term “flatulent” but I believe my readers to be a hardy bunch. Besides, the word “fart” makes me giggle like a schoolgirl.) I was also deeply concerned about animal welfare and understood that grass-fed, pastured cows were typically happier and healthier. I found a local farmer who delivered grassfed beef to our home every few weeks. It cost more, but we ate less, which balanced our budget. And when I took that first bite, I moaned with pleasure and asked my husband: “Does this taste so good because I haven’t had meat in four years? Or is this just really good?”

He nodded. “Yes,” he said, “it’s really good.”

So, there’s that — our admittedly subjective assessment that grass-fed beef tastes better.

You reference research that concludes that grass-fed cows do not, in fact, produce lower methane emissions than grain-fed cows. It isn’t that grass-fed cows produce more belches or farts, but rather that grass-fed cows grow more slowly and are slaughtered at an older age; therefore, over a longer lifespan,

they produce more belches and farts than shorter-lived cows, emitting methane with each digestive eruption.

What’s more, comparing greenhouse gas emissions from grass-fed vs. feedlot cattle is just a part of the picture.

For one thing, pastures of grasses themselves absorb greenhouse gasses, which offers some mitigation. In a climate like the northern U.S., however, where grass only grows a few months each year, the carbon benefits are reduced.

For another, grass-fed animals, which eat and poop on the land, contribute to soil health. And healthy soil, a product of this regenerative farming, absorbs more carbon than less healthy soil.

Simon Athearn, CEO and farmer at Morning Glory Farm, says that soil health is a key motivation behind his dedication to grass-fed. “On a feedlot,” he explains, “the animals are on a hard, biologically dead surface, conglomerated together instead of spread out, and fed an aggressive diet of very high-density foods that process less efficiently in the rumen and create more flatulent gasses. A ruminant’s natural diet is grasses.” As well, he says, the grain industry has to produce the grain fed to those cows, often via a monoculture, which causes erosion and depletion of soil. And processing the grain creates a greenhouse gas trail: Grain must be harvested, processed, bagged, and distributed, generally by large machinery and trucks.

Athearn also touts the benefits of local grass-fed cattle. Much of what we see on

store shelves that’s labeled grass-fed comes from animals as far away as Australia and New Zealand. If it’s processed or inspected at all in the U.S., the label will look like it’s from the United States.

Which is reason number a kajillion why it’s important to get your food from a local farmer. Not because food miles have a significant impact on carbon emissions (they, surprisingly, don’t), but because it’s far easier to discern the agricultural principles of a neighboring farmer, and because it’s smart to support those with whom you share a community.

But remember, too, Robert, that because of the deforestation required to provide land for cattle, not to mention the loss of biodiversity, beef (no matter what it’s fed when it’s simply a cow) has an outsized impact on the warming of our planet. So, if you’re going to eat beef — grass-fed or otherwise — do so sparingly, and savor every bite.

Ruminantly, Dot

Dear Dot,

I’m looking for bed sheets that are both happy to sleep on, and aren’t bad news for our environment. What should I look for?

—Dawn

My dear Dawn,

Are you the same Dawn who wanted to deter pigeons from perching on your balcony (and pooping on your patio?), but only in a kind way? Or are all Dawns

DEAR DOT 17 marthasvineyard. .com

DEAR

Illustration Elissa Turnbull

gentle souls who want happy pigeons and happy sheets? I’m going to assume that’s the case and endeavor to help you find sheets that would be delighted to envelop you in slumber while being good news (or at least not bad news) for our planet, and while pigeons coo happily on someone else’s balcony.

Lucky for Dot (and Dawn), Bluedot has its very own sheet expert — our own Marketplace editor, Elizabeth, who makes it her mission to find the happiest, most earth-friendly sheets (and other products!) and bring them to our readers. Indeed, Elizabeth recommends sheets from Coyuchi, Boll & Branch linens, and Cariloha, all of which can be found on Bluedot's online Marketplace. And Bluedot’s Room for Change columnist Mollie Doyle, offers up a (ahem) cheat sheet, with an eye to only earth-friendly materials.

Let’s start with Elizabeth’s sage and sleepy advice: Let others do the work for you. She’s referring, of course, to certifications that give you a shorthand. Third-party certifications mean that peo-

ple and organizations with a (usually but not always) robust list of eco-conscious requirements have examined the product and assessed it according to (usually but not always) rigorous standards. I say “usually but not always” because not all third-party certifications are equally legit. Who can you invite into your sheets? Both Mollie and Elizabeth urge you to look for the following respected certifications:

Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS); Fairtrade; 1% for the Planet; Certified B Corporation; OEKO-Tex; Cradle to Cradle; among others. Mollie turns to the “About Us” section of companies’ websites to uncover information, looking specifically for how the materials for the sheets are grown, chemicals/dyes used in the manufacturing, a traceable supply chain, labor standards, water use in manufacturing, and how the products are shipped and in what packaging.

Of course, even if your sheets meet a scrupulous eco agenda, you want them to offer comfort and ease of use.

Dot, for instance, loves linen sheets and pillow cases. Linen is a low-impact fabric (environmentally), but Mr. Dot considers it a high-discomfort fabric so … no linen sheets in the Dot household, though our duvet cover is a lovely, rumply linen that I adore.

It’s pretty much a case of “trial and error,” Mollie Doyle says. “Bed linens are personal.”

Indeed. I’m not sure it gets any more personal than what we snuggle up against night after night.

Dreamily, Dot

Want to see more Dear Dots? Find lots here: bit.ly/Dear-Dot-Hub

Check out our new Daily Dot newsletter and get a Climate Quick Tip each weekday, and an answer from Dot each Saturday. On Sunday, Dot rests. Sign up here: bit.ly/BDL-newsletters

Sign up for the BuyBetter Newsletter here: bit.ly/BDL-newsletters

In a world of disposable goods, it’s hard to know which products are sustainable. At Bluedot, we do the legwork for you by selecting items made with regard for the planet and its people.

DEAR DOT 18 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

less, but when you do — buy better. Shop the BuyBetter Marketplace Sign up for Bluedot Living’s BuyBetter Marketplace, a biweekly newsletter that navigates the confusing world of stuff. bluedotliving.com/marketplace

Buy

Climate luminary Bill McKibben hardly needs an introduction, but his new project does. Now 62 years old, having participated in numerous pivotal environmental campaigns over the past forty years, McKibben has created a new program called Third Act (thirdact. org) to mobilize 60-plus-year-olds to use their political and financial clout and stand alongside the young people fighting for their future. He’s optimistic about his generation stepping into this moment. “People,” McKibben says, “are ready to go.”

Bluedot Editor Leslie Garrett talked with Bill McKibben after he spoke to an overflow crowd at the West Tisbury Congregational Church in July.

Interview edited for brevity and clarity.

Leslie Garrett: You mentioned you spent time on Martha’s Vineyard when you were a kid. My editor would kill me if I didn’t get a bit more detail about your experiences here.

Bill McKibben: We’d come for a week every summer, every year for eight or ten years. There was a house … someone said it’s still there. Multi-colored panels, sort of halfway on the beach on Gay Head, nothing around within a mile or two on either side. It was the high point of the year.

LG: When you think back, what stands out?

BMcK: So many things that are familiar and unchanged. We would go to Menemsha to get bluefish in the afternoon. We used to love running down the dunes and climbing through the clay cliffs. (I sort of hope that they tell people not to do that anymore.) Mostly we just played in the ocean hour after hour. I got to go into the ocean yesterday, and it brought back many memories. I mean, I chose to live up in the mountains, and I love the mountains and the forests, but it was a powerful dose of nostalgia to be here. And very nice to see that, in certain ways, this place has changed less than other places.

CLIMATE CONVERSATION

19 marthasvineyard. .com

with Bill McKibben

CLIMATE CONVERSATION •

c KIBBEN

Interview by Leslie Garrett Photos by Randi Baird

BILL M

McKibben spoke at the West Tisbury Congregational Church in July.

LG: From what I’ve read, it sounds like your childhood was pretty rooted in the natural world, including coming here. Do you trace that to the work you do now?

BMcK: Yes, my father grew up out west, loved the outdoors, and loved to hike. [The outdoors] was important to me growing up, but I didn’t think it was going to be my life’s work. I was interested in homelessness and other urban questions. A week after I graduated from college, I went to the New Yorker to write the Talk of the Town, a quintessentially urban thing. But in the late 1980s, when I was in my mid late 20s, reading the early science about climate change, I became convinced that this was the overwhelming story of my lifetime. I’ve been on it ever since. That first book in 1989 [McKibben’s “The End of Nature”] was … about climate change. It was excerpted in the New Yorker and came out in twenty four languages, and that sort of sealed my course.

LG: I came to climate writing through a social justice lens … and very quickly learned that companies that could care less about their workers could care less about the environment. Do you think people have made that sort of connection with climate? That climate issues include homelessness and racial injustice?

BMcK: Yes, people talk much more about climate justice now than they used to. And the basic understanding that the people who are suffering the worst did the least to cause it is an important revelation.

LG: The conversation taking place around the UN and the Green Climate Fund [the fund to help developing countries respond to climate change] … I’m immersed in it, yet it still feels kind of remote. It feels sort of like it’s happening over there.

BMcK: I don’t think our Congress will be quick to pay loss and damages to the rest of the world. But I do think there’s momentum building to at least make it easier for people in the Global North to finance the kind of work that needs to be done in the Global South.. Figuring out how to free up that money, take the risk out of those investments so people can make them at a reasonable rate — that kind of thing is really important. Your neighbor John Kerry is really leading the work on that.

LG: Where else do you see leaders right now?

BMcK: Young people. I think we were extraordinarily lucky that Greta Thunberg appeared when she did. And our first real climate rockstar was not a diva, she was a good soul. Happily, we’re now seeing a lot of older people stepping up to help. The growth of this work at Third Act has been much more explosive than we’d imagined. That’s a good sign, I think.

LG: I have young adult children. I see a lot of anger in young people.

BMcK: Rightly so. It’s the sense of having been abandoned to figure this out on their own. And anger that we got to live through a relatively easy period, and they’re not going to.

LG: And that was part of your thinking with Third Act — to say “we’ve got your backs?”

BMcK: It’s good for people to be able to say that, and for kids to hear it. It offers some relief, anyway. That sense of being abandoned is a difficult thing.

LG: You mentioned that people over age sixty lived through the civil rights movement. How does this fight feel different from the civil rights movement? Or maybe it doesn’t.

BILL M c KIBBEN • CLIMATE CONVERSATION 20 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

McKibben and Bluedot Living's Leslie Garrett.

BMcK: One way in which it’s easier now is that, at least in this country so far, people aren’t killing you or blowing up your churches. One way in which it was easier then is that ’there was no multitrillion dollar industry that depended on segregation. By the end [with civil rights], business was more or less on the right side. In this case, there is a trillion dollar industry using a huge percentage of its money to make sure it can continue its business model indefinitely.

LG: When you created 350.org, you gave a vocabulary to the climate issue. You literally gave it a number. What is the power of that?

BMcK: One of the reasons we did that was because we needed to organize globally. We were organizing demonstrations in every country except North Korea, and it would have been much harder if we’d been using English words. Arabic numerals cross linguistic boundaries more easily. But people said it was too depressing a number, because we’re already past 350 parts per million in the atmosphere. A point I took, but I think that’s actually been helpful. It’s like cholesterol: if your doctor says, ’Keep eating like this, and someday your cholesterol will be too high,” you just keep eating until your cholesterol gets too high … but if the doctor says, ’You’re in that zone where people have heart attacks, and you might have had a little stroke yourself already,’ then it’s like, ’What pill do I take now?’ Urgency concentrates the mind.

LG: You have said, “we become most fully human when we don’t put ourselves at the center of everything,” and that the most important thing an individual can do right now is not be such an individual. What do you want people to take away from that?

BMcK: Well, given the scale of the challenge, it’s not practical to imagine solving it one person at a time; it won’t add up fast enough. You need to figure out how to leverage your efforts, and the only way to do that is to find other people and form movements that can shift real power. If five percent of people

lived responsibly in their own homes, it’ would be good, but it wouldn’t really change the trajectory. But if you can get five percent of Americans really engaged, that will be more than enough to win most of these fights, because there’s so much apathy that five percent of people turn out to be a huge force — enough to stand up to all the money in the world. But we’re not there yet. We’re at about two percent.

LG: We’re such an individualistic society.

BMcK: And much more so than when I was growing up. The election of Ronald Reagan represented a decision to become hyper individualist. He said, ’government is not the solution, it’s the problem.’ Hence, working together was the problem. His theory was that markets solve all problems. We’ve now tested that rigorously, and the Arctic is melting.

LG: It’s also the case that when there is a natural disaster, people come out of their houses, pick up shovels, and help.

BMcK: There’s a wonderful book that Rebecca Solnit wrote called A Paradise Built in Hell, on just that subject. I think about it often.

LG: On an island, there tends to be a greater sense of interdependence. I don’t know how familiar you are with some of the work the Island is doing, but I’m wondering if you’ve seen things that you think we’re getting right.

BMcK: Clearly, land preservation is something that people have taken seriously and done well. Of course, it’s particularly hard to do in a place where real estate prices are as high as they are here, so that’s a really powerful step. And now, the Vineyard is poised to be playing an important role: the wind resources around here are

Continued on page 60

21 marthasvineyard. .com

CLIMATE CONVERSATION • BILL M c KIBBEN

Overflow crowd on a July Sunday in West Tisbury.

My mother valued freshness and local-ness

above all else, skewing always toward homegrown vegetables, our own chickens or birds and game my father brought home from his shooting outings, honey made by a beekeeper in the neighborhood, eels or shad from the door-to-door fish monger.

Root vegetables harvestedf romthefeldsatMorningGloryFarm

.

is Local Eating Good Eating

Story by Laura D. Roosevelt

Photos by Alison Shaw

Story by Laura D. Roosevelt

Photos by Alison Shaw

It was the summer of 1996, my first on Martha’s Vineyard as a year-rounder, and I was standing on the worn pine steps outside the kitchen door of a house in the woods of West Tisbury. I breathed in, and, all of a sudden, I was thrown back to 1970, the summer after my parents’ divorce. I was overwhelmed anew with all the feelings that had characterized that summer — sadness about my broken family, apprehension regarding my mother’s and my upcoming move to a different state, delight and relief at being again on Martha’s Vineyard, where we’d come for a month every summer since I was six. What brought on this bout of intense nostalgia? The scent of wild blueberries, sweet and mingled with a humusy musk from the dirt that sustains

them, wafting through the woods on a humid afternoon; wild blueberries, like the ones my mother and I would pick together almost daily during that summer when I was eleven.

My mother was a foodie long before the term was coined. She valued freshness and local-ness above all else, skewing always toward home-grown vegetables, our own chickens or birds and game my father brought home from his shooting outings, honey made by a beekeeper in the neighborhood, eels or shad that the door-to-door fish monger in Washington, D.C. told her he’d caught just that morning in the Potomac River. And she was a forager. We found blueberries together all over the Island. We’d be driving along, say, State Road between Vineyard Haven and West Tisbury, when, abruptly, she’d pull over

onto the shoulder, grab a couple of paper bags from the back seat (my mother was always prepared), and say, “Let’s go! I smell blueberries.” We’d head into the woods, where, sure enough, we’d find a swath of wild, low bushes, and we’d pick until our bags were bursting. The berries were small, blue-black or a dusty lighter blue, and packed with flavor. (The darker berries may actually have been huckleberries, I now suspect.) We ate them on our breakfast cereal, spooned over vanilla ice cream at lunch, and — my favorite — cooked up in one of her famous blueberry crisps for dessert after dinner, blue juices bubbling up around the edges of the buttery, sugary topping. That summer, my mother and I were staying in a rented house in Chilmark that came with access to a little beach in a deep cove. To my mother’s delight, the boulders that poked up from the water in that cove were covered in mussels. She taught me to pick only the largest ones (“Leave the smaller ones for next summer!”), and she had a theory that the ones growing below the low-tide mark were preferable (though I’ve since read that mussels that get exposed to air when the tide goes out are fine, too, since they hold water inside their shells to stay hydrated.) We’d take colanders to the beach with us when we were musseling, and then we’d bring our catch home, and she’d steam them in white wine, garlic, and herbs, and serve them alongside a cup of melted butter for dipping. They were deep orange, flecked with green bits of parsley, and they tasted like little pillows of ocean-ness.

My mother’s daughter in more ways than I ever imagined I’d be, I’ve become just the kind of foodie she was: local and fresh are my guiding principles. I have a tennis-court-sized vegetable garden at my home in West Tisbury, and for the past two years, I’ve been growing with a view to preserving my garden bounty so that I can eat my own, home-grown produce as much as possible year-round. (See my Garden to Table columns here:

Blueberries and strawberries at the Farmers Market.

LOCAL EATING IS GOOD EATING • ESSAY 24 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

summer when I was eleven.

bit.ly/Garden-Table) I freeze peas, beans, grated zucchini, and pesto; pickle and can tomatoes, beets, cucumbers, and carrots; store onions, garlic, and butternut squash on shelves in my basement; and keep cabbages, kohlrabi, and daikon radishes in the fridge, where they last for many months.

But despite the environmental and pocketbook benefits of eating one’s own canned tomatoes in February, there’s nothing quite like eating a vegetable that was picked twenty minutes ago. Arugula fresh out of the garden is an entirely different green than what you find in stores — so peppery it’s almost hot. Justpicked asparagus are so sweet, juicy, and crisp that my husband and I eat them raw, usually while the rest of dinner is cooking. And a big, pink Brandywine tomato still warm from the sun? Slice it, throw it on a piece of garlic-rubbed toast with some fresh basil, a sprinkling of salt, and a drizzle of good olive oil, and you might as well be in Italy. Or maybe Heaven.

I almost never visit the produce section of the grocery store during the months

ESSAY • LOCAL EATING IS GOOD EATING

The scent of wild blueberries, sweet and mingled with a humusy musk from the dirt that sustains them, wafting through the woods on a humid afternoon; wild blueberries, like the ones my mother and I would pick together almost daily during that

when my garden is yielding its gifts; rather, I plan meals around what’s ripe at the moment. But I don’t grow everything, and some years, certain crops don’t do well for one reason or another. That’s when I visit the Island’s farms. Rusty at Ghost Island Farm has managed to extend his tomato season on both ends using greenhouses, so I’m a regular at his farmstand when he’s got tomatoes and I don’t. Last summer, when an explosion of chipmunks ate more of my tomatoes than we did, I frequented Ghost Island all summer long to make up for my shortfall.

I gave up on growing potatoes after a few years of worm-ridden harvests, so now I get my potatoes from Morning Glory Farm. Their purple potatoes are my favorites, for both their eye-catching color and their nutritional content (as a rule, the darker the vegetable, the higher it is in nutrients.) Our favorite way to eat potatoes comes from my friend Injy, who twice-cooks them to crispy, decadent perfection. First, she boils them until they’re tender. Then, she smashes them into thick little pancakes with cracked edges, puts them in a baking dish with some generous glugs of olive oil, and bakes them until they’re crunchy on the outside but pillowy soft on the inside. I could live on those.

many other people believe the opposite), but that turns out to be a myth: Corn color is caused by the presence of more (or less) beta carotene, which does not affect flavor (though it does increase the corn’s nutritional value, since beta carotene turns into Vitamin A when digested). Sweetness is most affected by time: The more hours elapse after picking, the starchier (and less sweet) an ear of corn becomes. But since people have been cross-breeding corn since the early 1800s to create varieties that hold onto their sweetness for longer, most corn you buy these days — even supermarket

They’re also quickly perishable, so you need to eat them right away… which, I promise, is never a problem.

Our absolute Number One favorite local fish is bonito. The first time I had it, a neighbor who’d just caught one brought it over, sliced it raw, and served it with a drizzle of soy sauce; it was the best sashimi I’d ever eaten, melt-in-your-mouth tender with a mild but distinctive flavor that spoke of whitecaps and seaweed and beams of sunlight streaming through the water into the depths.

Morning Glory Farm is also almost everyone’s go-to place to buy local corn when it’s in season. (See our story on corn on page 38.) Corn salads seem to be on the menu at every late summer dinner party I attend, and that makes me a happy guest; because really, who doesn’t love a good corn salad, say, laced with fresh basil and some halved sungold tomatoes? But my favorite way to eat fresh corn is on the cob, slathered in butter and sprinkled with salt. I always thought white corn was sweeter than yellow corn (though evidently

corn — is pleasantly sweet. And strawberries? I’ve been losing mine to squirrels and birds for the past couple of summers, but this year I found them in June at North Tabor Farm, and they were so delicious that I went back every few days for more while they lasted. (Morning Glory Farm also has them, I’ve since learned.) Grocery store strawberries have been bred and modified to be huge, extra-firm, and long-lasting, but they’ve traded away a lot in terms of flavor and texture in order to be able to withstand shipping and several days of sitting in the produce aisle. Local berries, in contrast, are small, deep red, tender, and oh-so-juicy.

In addition to eating as much as possible from my own and other Island gardens, I’ve resolved to eat local protein whenever I can. So far, nobody here is making tofu; but fish? Chicken? In both cases, you can’t go wrong eating local. Island-raised chicken (I’m partial to Mermaid Farm’s and North Tabor Farm’s) is hormone- and antibiotic-free, cage-free, and all (or most) of those other good things conscientious buyers look for on grocery store chicken packages. And, as with local vs. grocery store strawberries, the flavor of a local chicken is richer, more complex, more … chicken-y. When I ate chicken from grocery stores, I always thought of it as a largely neutraltasting vehicle for sauces, rubs, and other accompaniments. Not so with local chickens. Our favorite way to prepare a bird from North Tabor or Mermaid Farm is to cut it in half and roast it in a smoky grill. My husband, the grill master in our household, does this to perfection. The smoke permeates the meat deliciously, and it’s always tender and moist with the oils from its own fat. No sauce is required (though we do often serve it with chimichurri on the side, made from my own garlic, oregano, and parsley.)

As for fish, we tend to buy whatever the fishmonger tells us was caught locally that day. Sea bass, bluefish, tautog — they’re all scrumptious when super fresh and simply cooked. One of my favorite local seasonal catches is squid. We tried jigging for squid once with a friend, with no luck. Evidently you have to be in the right place at the right time, and we weren’t. Fortunately, the fishermen who

LOCAL EATING IS GOOD EATING • ESSAY 26 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

supply our local markets seem to know better than we did, and when fresh local squid comes in, we snatch it up. Again, we like it best done in our smoky grill, seasoned only with a little lemon brine (from the ever-present jar of homemade preserved lemons in my fridge), olive oil, and pepper. When it’s really fresh, squid is

tender, not chewy, and it goes very nicely on a bed of white beans cooked with rosemary and lightly mashed. Our absolute Number One favorite local fish is bonito. The first time I had it, a neighbor who’d just caught one brought it over, sliced it raw, and served it with a drizzle of soy sauce; it was the best

sashimi I’d ever eaten, melt-in-your-mouth tender with a mild but distinctive flavor that spoke of whitecaps and seaweed and beams of sunlight streaming through the water into the depths. That’s still our preferred way to eat bonito, but we’ve discovered that it’s also great very lightly seared, sliced, and served drizzled with both soy sauce and truffle oil, which turns it into a richer dish that can only be described as luxurious.

Meanwhile, since I haven’t found any wild lowbush blueberries near my house, I planted several highbush varieties in my yard. Most of them have grown nicely and yield quite a lot of berries… which, every year, the birds get to before we do. Year after year, I vow that next summer I’ll wrap them in netting to deter the avian gourmands, and year after year, I fail to do it. There’s so much to occupy me in my vegetable garden that I simply run out of time. Maybe one day I’ll get to it, but for now, I’m happy just remembering the blueberry crisps of my childhood.

ESSAY • LOCAL EATING IS GOOD EATING 27 marthasvineyard. .com

We’d take colanders to the beach with us when we were musseling, and then we’d bring our catch home, and she’d steam them in white wine, garlic, and herbs, and serve them alongside a cup of melted butter for dipping. They were deep orange, flecked with green bits of parsley, and they tasted like little pillows of ocean-ness.

Have You Seen the

Little Piggies Eating All the Scraps?

Fork to Pork’s pigs upcycle Martha’s Vineyard’s food waste.

Story by Daniel Cuff Photos by Irina Bezumova

Story by Daniel Cuff Photos by Irina Bezumova

Come most spring summer days, Jo Douglas will drive her black Toyota Tundra around Martha’s Vineyard, and stop at more than thirty restaurants to collect leftovers and food scraps. She’ll cart about fifteen barrels back to her farm on the Land Bank Wapatequa Woods property that straddles the Oak Bluffs, Vineyard Haven line — and lay out a feast for her passel of Idaho pasture pigs.

When she pulls up with a truck full of carrot tops, beet greens, lettuce, tomatoes, avocado pits, scrambled eggs and a new discovery, yucca, the pigs squeal. (They are also known to enjoy the occasional Back Door Donut.) Jo’s pigs survive entirely on leftovers, until the time inevitably comes for her to slaughter them, and return them to many of those restaurants as pork.

Thus is the circular, righteous beauty of Fork to Pork.

Anyone who’s worked in a restaurant knows how much food gets thrown out — salad greens showing a bit of browning, prepared sides like vegetables and potatoes that can’t be used for a second service, or baked goods that lose their charm after a day or two, never mind the unfinished meals that diners leave on their plates.

Unlike restaurant patrons, Jo’s pigs never leave scraps behind.

Since eighth grade, Jo has wanted to be a farmer. In high school and while she was earning her degree in sustainable agriculture and food production (with a minor in animal studies) from Vermont’s Green Mountain College, she worked on farms as a farm worker, apprentice, intern, and manager. Summers, she’d come to Martha’s Vineyard.

Five years ago, she started her own farm.

“I was looking for a farm model that would work, where I could have my own animals,” she told me on a day I visited last summer, while pigs ate ravenously all around us. “I had worked on a couple of farms where we fed pigs some food scraps but not entirely on scraps.” A lot of farmers told her that feeding pigs a healthy diet completely from scraps couldn’t be done. “But I thought it could,” she said.

Most of the food she picks up around

the Island would have been shipped offIsland to a landfill along with all our other waste (if it wasn’t composted). And at the same time, ferries coming back to the Island bring large amounts of hog feed. Why not raise pigs on food that would have otherwise been thrown away?

It’s a win-win-win, no matter how you look at it: Save the carbon impact of trucking wasted food off-Island, save the methane created by putting organic waste in a landfill, save the impact of transporting food for pigs back to the Island.

And the pigs seem to love the entire dining experience. “You are what you eat, and around 95 percent of the pork in the US is from factory farms where the pigs are on cement floors and never get to exhibit their natural pig behavior of rooting for food,” Jo says. “That’s what pigs want to do. They’re smarter than dogs, so you have to kind of entertain them, so every day I come with my truck and I have 300 gallons worth of food, and they get to practice their natural behavior, rooting through all the food scraps and getting what they like. So they’re never bored, they’re always excited, they eat so much and then they take a few steps back and just pass out in a food coma.”

She says that when she first started, she collected from about fifty restaurants in all six towns, working twelve- to fourteen-hour days. “I was starting my own business,” she says, “so I said yes to everything.” In the past few years, she says she’s been able to strike a healthier balance.

When I asked if there were any particular challenges she faced, she shrugged. “It’s a lot of work. It can be very physically demanding, and it’s seven days a week. But I love it. I don’t treat it as a job, it’s my life.

“I get to collect all this great food for [the pigs] and I get to see these thirtythree happy animals that are growing well and eating really good food.”

FEATURE • FORK TO PORK 29 marthasvineyard. .com

C

They’re always excited, they eat so much and then they take a few steps back and just pass out in a food coma.

Jo Douglas with one of her passel of pigs.

Jo’s pigs survive entirely on leftovers, until the time inevitably comes for her to slaughter them, and return them to many of those restaurants as pork. Thus is the circular, righteous beauty of Fork to Pork.

THE FULL, RIGHTEOUS CIRCLE

Pawnee House, in Oak Bluffs, is one of the restaurants that sends its scraps to Jo for pig food. And Pawnee often has pork on its menu. Alex Cohen, co-owner of the restaurant with his wife, Deborrah (the chef), sent us this:

“We think Jo is an extraordinary human being! Here is the recipe for Debbie's Italian-style Porchetta dish that we ran as a special after receiving our pig from Jo. We ran it as both a sandwich, as well as a dinner plate with various sides — it was out of this world!” – Alex

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Check out Jo’s instagram (@forktopork) to see which restaurants help feed the pigs.

Consider ordering a pig for your family’s meals from Jo: She’ll pick up your food waste scraps to feed it! Write her at forktopork@gmail.com. Find more info at forktopork.com

FORK TO PORK • FEATURE 30 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

5. Place the pork loin on top of the herbs and spices on the pork belly and roll. Tie the Porchetta with kitchen twine about 2 inches apart. Score the tough side of the skin like crazy. First left or right, then top, about 1 inch apart. This will help to render out the fat and crisp the skin when cooking.

6. You will need to dry the Porchetta in the refrigerator uncovered for 24 hours. This helps get that wonderful crispy skin.

DEBBIE'S Italian-Style PORCHETTA

Pork Belly ½ lb per person

Pork Loin (with Italian-style porchetta you actually wrap the pork loin around the pork belly)

INGREDIENTS FOR THE RUB

6 crushed Garlic Cloves

Rosemary

Sage

Nutmeg

Thyme

Zest of an orange

Fresh Fennel

Pinch of chili flakes

Generous cracked pepper

SERVING SUGGESTIONS

Ciabatta

Arugula

SALSA VERDE

parsley

capers

vinegar

evoo

s&p

DIRECTIONS

1. Score the inside of the pork belly with diagonal lines about 2 inches apart using a crosspatch pattern. This is so the herb mixture can penetrate the inside of the pork belly.

2. Freshly zest an orange and about a half grated nutmeg.

3. Chop fresh sage, rosemary, and thyme to cover the base of the pork belly.

4. Press all the fresh herbs into the belly. Fennel leaves are optional. Add cracked pepper, kosher salt, and six crushed garlic cloves. If you like a little heat, do a few pinches of red chili flakes. Press all of the herb spices into the belly, again.

7. Preheat the oven to 250°. Line a baking sheet with tinfoil then place the Porchetta on the rack and bake for 3 to 8 hours depending on the size until the pork reaches a temperature of 160 Fahrenheit.

8. Let rest for 30 minutes, then it’s ready to serve.

FEATURE • FORK TO PORK 31 marthasvineyard. .com

COURTESY PAWNEE HOUSE RESTAURANT

Noah Mayrand on the raft that is surrounded by buoys — his oyster farm. Each buoy marks a submerged cage lying twenty feet beneath the Lagoon.

FARMING OYSTERS TO FEED AN ISLAND • FEATURE 32 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 20 23

Noah grew up on the Island and has been connected to the ocean and sea life for as long as he can remember.

He’s Farming Oysters to Feed an Island

Noah Mayrand: And helping our waters thrive.

Istep out onto the beach, and the familiar southwest winds running down the length of Lagoon Pond welcome me. Though I have spent many afternoons on these waters with my high school sailing team, I was barely aware of the flourishing shellfish farms a short distance from where we typically launch our boats — until I was invited to see one for myself.

I look behind me to see oyster farmer Noah Mayrand making his way down to the beach. He helps me onto his skiff, and we depart the dock. I have no idea what it takes to grow shellfish, but I’m eager to find out.

Noah grew up on the Island and has been connected to the ocean and sea life for as long as he can remember. “I spent so many hours on the jetties,” he tells me. “That was my babysitter — playing around, fishing, snorkeling.” Mayrand's father, a plumber, would barter his services with fishermen who would take Noah and his father on chartered fishing trips to catch striped bass. Noah was only four or five when he began fishing, but he quickly became addicted. His mom often took him to Tashmoo Beach where he’d climb the jetties with his

friends and scrape seaweed off the side of rocks or find small shrimp. He tells me matter-a-factly, “We would eat it. That’s where I gained a taste for ocean.”

He knew he wanted to keep this early, deep connection to the sea for the rest of his life. He learned to sail at Sail MV; later, he learned to build sailboats during a high school internship at the Five Corners boatyard with the Charter School. Both of these experiences, he believes, helped prepare him to be an oyster farmer. “My workshop was the boatyard,” he says. “That’s kinda why I know how to build rafts.”

I spot a ten- by fifteen-foot wooden raft surrounded by a dozen buoys — Noah’s oyster farm. Each buoy marks a submerged oyster cage lying twenty feet deep on the Lagoon floor. He docks his skiff and helps me onto the raft.

I want to know what has kept him motivated in the risky aquaculture business. How does someone decide to become an oyster farmer? For Noah, it stemmed from his career as a cook.

Though he studied art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Noah found himself drawn to cooking after he got out of college. The farm-to-table movement was taking

FEATURE • FARMING OYSTERS TO FEED AN ISLAND 33 marthasvineyard. .com

Story by Annabelle Brothers Photos by Randi Baird

off in California, and he wanted to be a part of it. Seeking a change from the Island, he left for San Francisco, where he experienced “life-changing meals.” He found a job at a restaurant called Beast and the Hare, where he learned the art of butchery. “It became, ‘how do we butcher it and how do we make a menu out of this,’” he tells me — as opposed to, “What can we make and where are we going to get it?” They used the whole animal, nose to tail, and built the menu around it.

Later he got a job at a big technology company in San Francisco, working as a corporate sous chef. While he often made sandwiches for interns, he also

got to work upscale dinners for CEOs and other private events. He had the budget to buy quality food, and he did just that.

Noah knew how to break down whole animals — pigs, lambs, goats, sheep. “We would go to cow farms and purchase a live cow,” he tells me. “They would be killed later in the season and then I’d butcher them.” Because he’d worked so closely with the farmers, he grew to appreciate the quality of local food. “I found this product was so far better than something that was sitting [in stores].” He adds, “The speed with which I could bring it to these people made it fresher — it just sat in that

many fewer refrigerators.”

After almost four years, he was ready for a change. “I was always talking about home. I was always saying ‘my island, my island.’” When he inherited some land on the Vineyard, he decided to return home. At the same time, he realized that he didn’t want to just cook fresh food; he wanted to grow it. He wanted to become a farmer — any kind of farmer. “I just needed a place to grow things,” he said.

Seeing the ocean as an extension of the Island, and noticing the growing aquaculture business on the Island, he did some research. Beyond the “howtos,” he learned about oysters’ ability to clean ocean water while capturing carbon, combatting some of the effects of climate change. This sealed the deal for him: He would grow oysters.

He hit a snag when he discovered that there was no process to obtain a permit for aquaculture in Tisbury, his town of residence. Undaunted, he went to his first town select board meeting in February 2015 and told the town “I wanna start an oyster farm. How do I do this?” At the board’s suggestion, he attended some shellfish board meetings, and along the way found others

FARMING OYSTERS TO FEED AN ISLAND • FEATURE 34 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

Now, working as his own boss, he finds that what keeps him going is his commitment to respecting nature and being a role model in his community. “I wanna be that different fisherman who gives more than they take,” he says.

When Noah harvests oysters, he's taking nitrogen out of Lagoon Pond.

Noah harvests and sorts oysters.

who also wanted to create aquaculture regulations in Tisbury that would allow for permitting down the road. It took years of hard work to get aquaculture regulations finally passed.

In the meantime, he set about learning the oyster farming trade by working as a farmhand with shellfish companies in Katama. His employers knew he wanted to start his own farm in Tisbury; they supported him and ensured, during his “four years of oyster college,” that he acquired all the know-how he’d need.

For his part, Noah hoped the regulations in Tisbury could reflect what he’d seen in practice in Katama. It had worked for 25 years, he figured, so it seemed like a good model. But “I didn’t feel like I was being heard,” he tells me, and it was difficult to get the community to reach an agreement. Finally, after four years, in November 2019, Noah became the first oyster farmer to secure an aquaculture permit in Vineyard Haven. He was relieved and happy — and ready to get started.

Through it all, Noah found motivation in other people’s doubt; he knew he could prove them wrong. “When they say you can’t,” he says, “you absolutely will.” Now, working as his own boss, he finds that what keeps him going is his commitment to respecting nature and being a role model in his community. “I wanna be that different fisherman who gives more than they take,” he says.

As Noah looks back on when he first anchored in Lagoon Pond, he is amazed by the diversity of species that have become a part of his farm. He was determined to grow oysters to benefit the waters, so he was happy to find new species of seaweed, mussels, and fish benefitting from his farm. His farm has built the foundation for a new ecosystem. Daily, he sees more and more fish feeding off an environment he contributed to. “It brings me back to my childhood,” he says, “where I saw [nature] as plentiful and diverse.”

FEATURE • FARMING OYSTERS TO FEED AN ISLAND 35 marthasvineyard. .com

He learned about oysters’ ability to clean ocean water while capturing carbon, combatting some of the effects of climate change. This sealed the deal for him: He would grow oysters.

FARMING OYSTERS TO FEED AN ISLAND • FEATURE 36 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

Annabelle Brothers just graduated from Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School, where she served as the president of the school’s environmental group, Protect Your Environment Club. She is also a student advisor at Bluedot Institute. In 2022, she became involved with the Martha’s Vineyard Commission’s Climate Action Plan which developed goals and strategies for Martha’s Vineyard’s future to mitigate the effects of climate change while building economic and infrastructural resilience. Annabelle will attend Yale this fall to study Environmental Engineering. She hopes to eventually take her skills overseas and help promote green urbanism in developing countries.

How Do Shellfish Help the Ponds?

The Martha’s Vineyard Shellfish Group grows “tens of millions of baby shellfish,” says shellfish biologist Emma Green-Beach. These are returned to the Island’s ponds, where they eat phytoplankton, which have absorbed some of the nitrogen in the ponds, and that then becomes the shellfish tissue. “When we harvest and eat those shellfish, we’re taking nitrogen out of the ponds,” she says.

The shellfish themselves are nitrogen fighters in a number of ways, explains Green-Beach. They improve water quality by filtering it, absorbing tiny critters as food and using nitrogen and phosphorus in their shells and tissue. The cleaner water allows sunlight to better penetrate the water column, boosting growth of submerged aquatic vegetation — which in turn provides habitat and sequesters nutrients. When shellfish poop after eating phytoplankton, their waste is buried in the sediment, where bacteria turns it into dinitrogen gas, which is benign in the atmosphere.

In addition to seeding ponds (including Lagoon Pond, where Noah Mayrand has his oyster farm) with baby shellfish, the M.V. Shellfish Group has been active since 2011 collecting shells — oysters, clams, mussels — from Island restaurants and returning them to the Tisbury and Edgartown Great Ponds, a project sponsored by the Martha’s Vineyard Vision Fellowship. Given that acidification is one of the consequences of nitrogen in the ponds, the shells, which are made of calcium carbonate, “act like Tums,” says Emma Green-Beach. “[The shells] raise the pH, they release calcium back into the water, which the shellfish need, and then the shells themselves act as substrate for the oysters to settle onto.” What’s more, she says, the project keeps the shells out of the trash and gets them back into the Great Pond ecosystem.

Win, win, win.

This MV Shellfish information first appeared in a Bluedot Living story “What’s So Bad About Nitrogen” in May of 2021.

GRILLED OYSTERS WITH SWEET BUTTER AND CLASSIC FRENCH MIGNONETTE

Makes 36 oysters

FOR THE MIGNONETTE

1 cup red wine vinegar

1/2 tsp raw sugar

2-3 finely chopped shallots

1/4 cup chopped fresh parsley

Lots of fresh cracked black pepper (6 turns of a pepper mill)

FOR THE BUTTER

1 stick of butter at room temperature

1/4 cup honey or agave syrup

Zest of 1 orange

Pinch of salt

36 fresh oysters, shucked

1. In a small bowl, mix together the ingredients for the mignonette and set aside.

2. In a separate bowl, whip the butter with the honey, orange zest, and salt. Top each shucked oyster with a generous ½ teaspoon of the butter mixture, then place the oysters on a hot grill and cook until the butter has melted and the oysters start bubbling, about 3 minutes.

3. Spoon a little of the mignonette onto each cooked oyster, and serve.

FEATURE • FARMING OYSTERS TO FEED AN ISLAND 37 marthasvineyard. .com

WHAT’S SO BAD ABOUT

CORN?

For a few sweet weeks each summer, corn on the cob from your local farmstand is the perfect treat — just check out the crowds around the bins at Morning Glory Farm. But corn is also grown to feed our cars and our cattle, and make the corn syrup that sneaks into so many of our processed foods. Meaning … corn is good, corn is not-so good, corn is complicated.

WHAT'S SO BAD ABOUT CORN • FEATURE 38 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

Story by Leslie Garrett Photos by Sheny Leon

Simon Athearn juggles corn in the fields at Morning Glory Farm.

FEATURE • WHAT'S SO BAD ABOUT CORN 39 marthasvineyard. .com

Simon Althearn starts his day at his family’s Morning Glory Farm by taking a bunch of bites out of raw corn. “Every single morning,” he says, “us and the crew are out in the field nibbling … You’ve got to test it to know what batch you’re in and what ripeness level to pick it.”

Ask him about the best way to cook corn on the cob, and his voice takes on a tone of reverence. “I love this question,” he says. While he enjoys seawater-soaked corn cooked in its husk over a grill, his and his family’s favorite method is to steam the cobs in about an inch of water. Four to six minutes, he says, depending on the size of the ears. Other corn lovers swear by boiling, and still others prefer to cook it in a microwave oven.

But although how to cook corn is a question that elicits plenty of strong opinions, it is far from the most contentious corn-related topic. “We hear the word corn, we think of our grandmother's garden, and corn on the cob, and that's all lovely,” says Jonathan

WHAT'S SO BAD ABOUT CORN • FEATURE 40 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /LATE SUMMER 2023

“Every single morning [we] and the crew are out in the field nibbling … You’ve got to test it to know what batch you’re in and what ripeness level to pick it.”

–Simon Athearn, Morning Glory Farm

Clayton Williams at the morning harvest.

Foley, Executive Director of Project Drawdown, a non-profit dedicated to advancing science-based solutions to climate change. “But when you get to the industrial scale, which corn really operates in, it's the single biggest crop in America. It covers roughly 100 million acres of land in this country, about the size of Montana. And hardly any of it is used for food.”