SIMPLE / SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES

SECRETS OF THE SALT MARSHES

EAT FROM YOUR GARDEN YEAR-ROUND

A VERY GREEN HOUSE IN THE WOODS Built like a Lasagna

CURRIER + BELUSHI = CRUISING

WHATS SO BAD ABOUT COFFEE?

MARTHA’S VINEYARD / SPRING 2023 MARTHA’S VINEYARD / SPRING 2023

SIMPLE / SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES

Planet-friendly

TM

John Abrams · Fruit Tree Guilds · Finches ·

Toilets

@bluedotlivingmv

BDL 1 marthasvineyard. .com

DEER, TICK & MOSQUITO CONTROL!

(508)627-2928 | MV@oh-DEER.com

oh-DEER.com/locations/MV

• SAFE FOR YOU, YOUR FAMILY & PETS!

• KILLS TICKS & MOSQUITOS ON CONTACT.

• AN EFFECTIVE ‘GREEN’ ALTERNATIVE TO PESTICIDES & CHEMICALS

ohDEER offers you and your family a proven and safe solution to control ticks and mosquitoes so that you can enjoy your yard. Our products are true all-natural repellents that contain no pesticides or chemicals of any kind.

Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. On it everyone you love .” –Carl Sagan

President Victoria Riskin

CEO Raymond Pearce

Editor Jamie Kageleiry, editor@bluedotliving.com

Senior Writer Leslie Garrett

Copyeditor Laura Roosevelt

Creative Director Tara Kenny

Design/Production Whitney Multari

Digital Projects Manager Kelsey Perrett

Social Media/Digital Projects Julia Cooper

Contributing Editors Mollie Doyle, Catherine Walthers Ad Sales adsales@bluedotliiving.com

Contributors, this issue Randi Baird, Geoff Currier, Mollie Doyle, Sheny Leon, Gwyn McAllister, Sam Moore, Alison Shaw, Catherine Walthers

Bluedot and Bluedot Living logos and wordmarks are trademarks of Bluedot, Inc. Copyright © 2023. All rights reserved.

Bluedot Living: At Home on Earth is printed on recycled material, using soy-based ink, in the U.S.

Bluedot Living magazine is published quarterly and is available at newsstands, select retail locations, inns, hotels, and bookstores, free of charge. Please write us if you’d like to stock Bluedot Living at your business. Editor@bluedotliving.com

Sign up for the Martha’s Vineyard Bluedot Living newsletter here, along with any of our others: the BuyBetter Marketplace, our national ‘Hub” newsletter, and our soon-to-be-launched Bluedot Kitchen newsletter: bit.ly/Bluedot-Newsletters

Subscribe! Get Bluedot Living Martha’s Vineyard and our upcoming Bluedot GreenGuide mailed to your address. It’s $40 a year for all four issues plus our Green Guide, and as a bonus, we’ll email you a collection of Bluedot Kitchen recipes. Subscriptions@bluedotliving.com

Read stories from this magazine and more at marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com

Find Bluedot Living on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube @bluedotliving

2 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

BDL • OUR TEAM

• • • • • •

ENJOY MORE

OUTSIDE! “

TIME

14 Secrets of the Salt Marshes

By Sam Moore

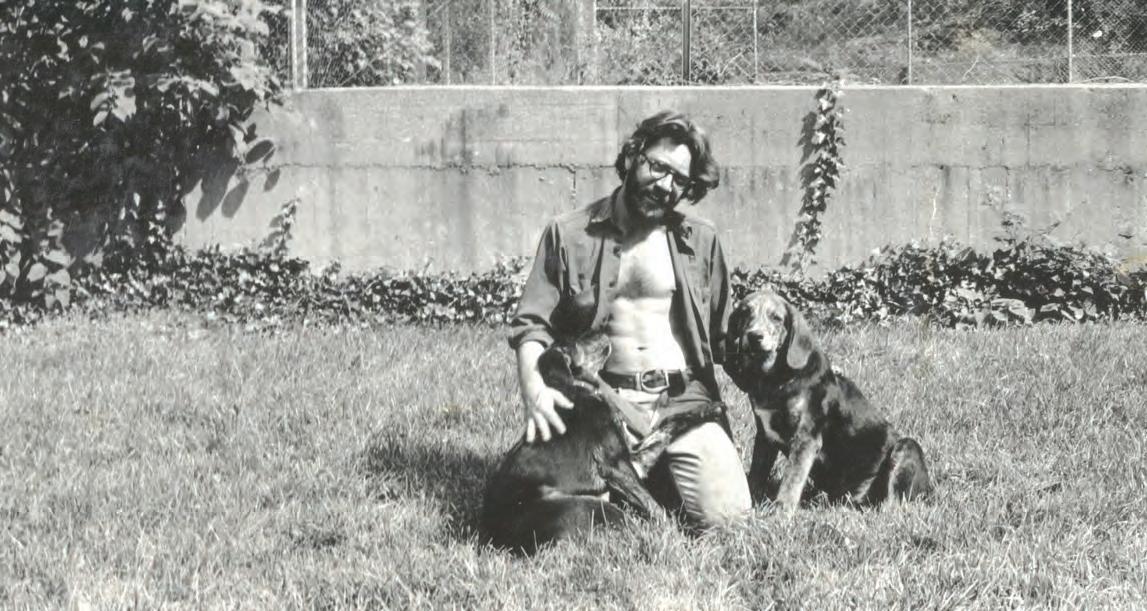

By Sam Moore

The marsh is both boundary and buffer — at the edge of the sea, it dampens wave action from storms, sequesters carbon, filters water, offers finfish and shellfish a protected nursery, and draws a sharp line at the end of many coastal walks.

21 Edible Backyards: How to Plant a Fruit Tree Guild

By Catherine Walthers

Roxanne Capitan describes a better way to grow fruit trees, relying on plants instead of fertilizers and fungicides.

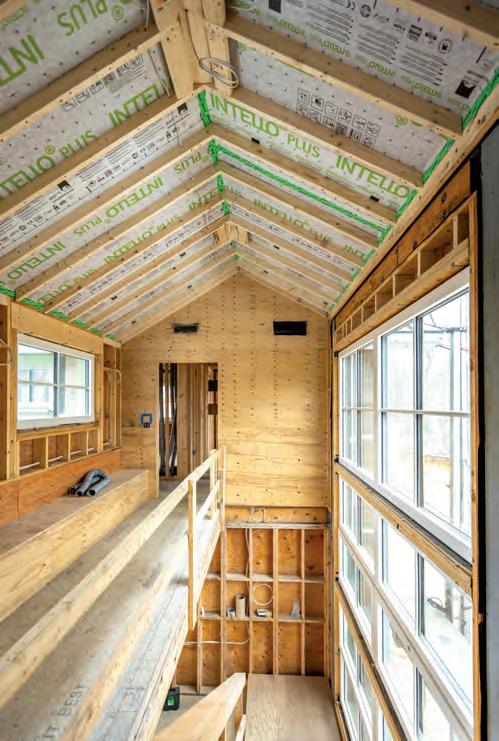

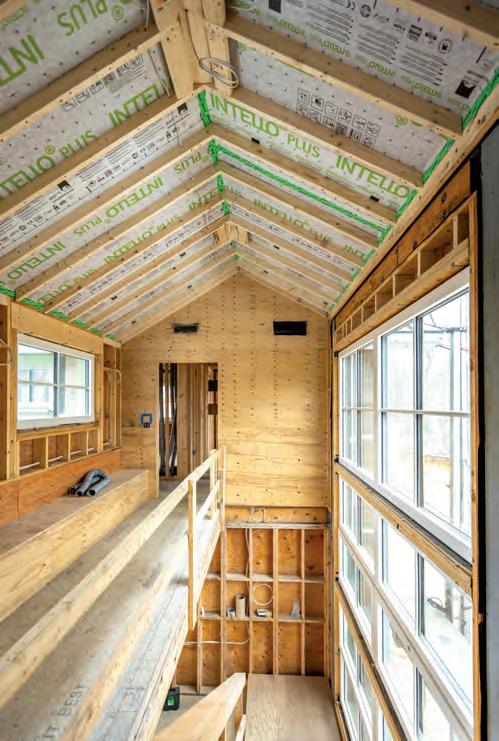

30 The Bones of Green Design

By Mollie Doyle

A delightful, net-zero home in the woods, built like a lasagna.

40 What’s So Bad About Coffee?

By Sam Moore

In the Ottoman empire, where coffee gave rise to hundreds of lively coffeehouses, the drink was periodically outlawed for its rabble-rousing tendencies. These days, we just want to make sure our coffee has been produced sustainably and with fair labor.

Departments

12 Dear Dot Do your House Finches have eye problems? Our eco-advice columnist finds the answers.

26 Garden to Table

By Laura Roosevelt

A new column from an ace gardener (and cook). Here’s how to start planning (and planting) to eat from your garden all year long.

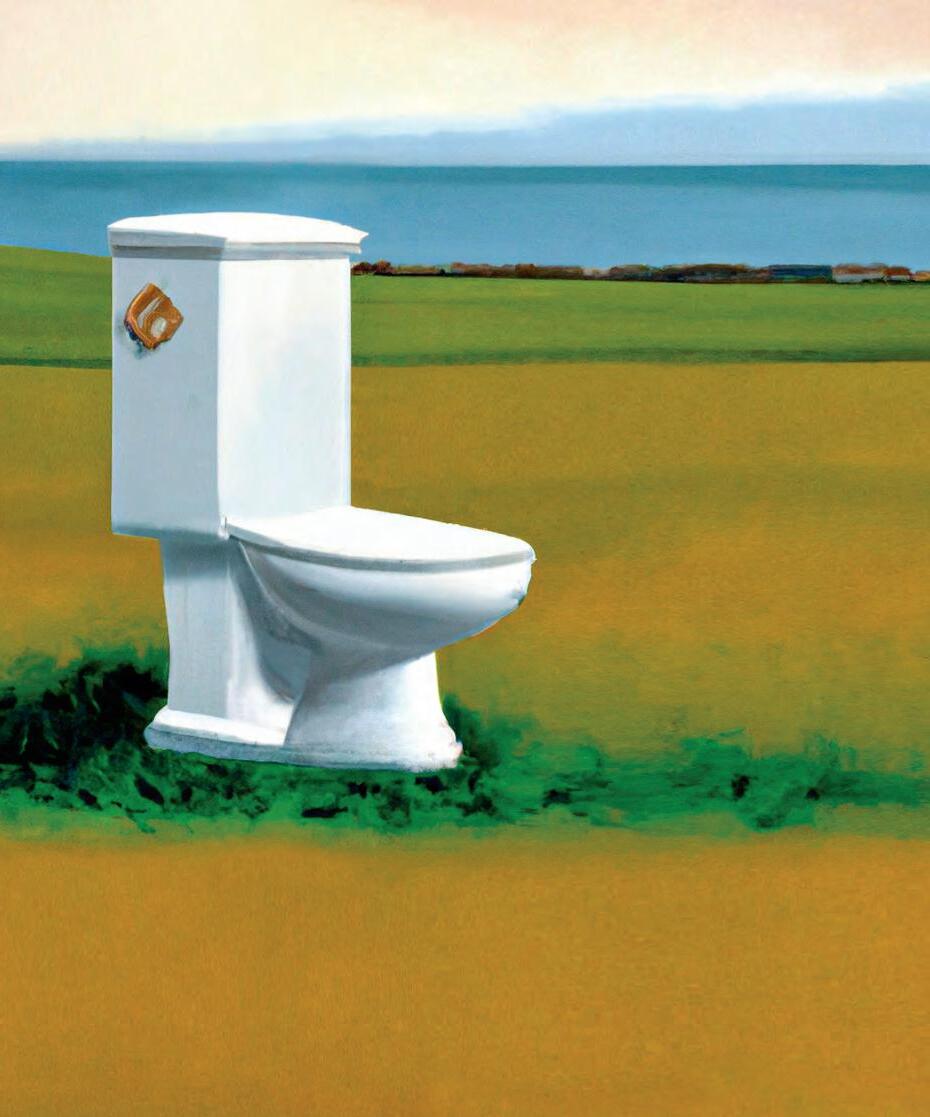

36 Room for Change: The Toilet By Mollie

Doyle

Did you know a single leaky toilet can waste up to 180 gallons of water per week? We have some thoughts.

46 Cruising With Currier

Our intrepid reporter zips around the Island with Judy Belushi and her Chevy Volt.

48 Local Hero: We nominate John Abrams, for the years he has dedicated to building sustainable homes (and communities).

CONTENTS

Upfront 4 Editor's Letter 5 What.On.Earth. Earth Day!

Home

6 Buy Better:

Goods/Homemade on MV 10 Field Note: Climate Action Fair 11 In a Word: Rewilding Features

Find Us! Sign up for our biweekly Martha's Vineyard Bluedot newsletter: bit.ly/Bluedot-newsletter More online At marthasvineyard.bluedotliving.com and Bluedotliving.com How to Get Rid of (Almost) Anything The Bluedot Buy Better Marketplace Lots More ‘Dear Dots’

PHOTO THIS PAGE: ALISON SHAW

Cover photo: Up-Island, by Alison Shaw

Dear Bluedot Living Readers,

“Figure out where your passion really is, and put your time in that passion,” John Abrams says in our “Local Hero” story on page 48. “We don’t have to change big things — we only have to change little things. If a lot of people change little things, that adds up … ”

John’s been working hard on building sustainable housing for years at South Mountain Company, and for almost as long helping to build a sustainable community on Martha’s Vineyard — most recently as one of the driving forces behind the creation of the Housing Bank. Beyond lauding John’s vision and generosity, we agree: A lot of people doing little things can make for big changes.

We hope that this magazine helps you make those little, every-day changes that together can make our planet healthier — with the things you plant (see Laura Roosevelt’s new Garden to Table column, on page 26; and Roxanne Kapitan’s plan for growing fruit trees without fertilizer, page 21); the way you drink your coffee (What’s So Bad About Coffee? Page 40); and even what toilet you decide to buy (Room for Change: The Toilet, Page 36). Please send us ideas — for stories you’d like to see, people we should know about, and maybe that cool way you upcycled something you would have tossed. Write me at jamie@bluedotliving.com.

Our Bluedot staff is growing! Ray Pearce has been named CEO of Bluedot, Inc. Ray spent more than 30 years at the New York Times — he was part of the team that launched the Times’s digital subscription business. Alison Mead will help produce our websites and will wrangle the digital assets we need for our rapidly growing stable of newsletters. You might know Ali from her time at Martha’s Vineyard Magazine and the Vineyard Gazette. Lucas Thors, an editor and reporter most recently at the MVTimes, will join our staff as a reporter/ web producer. He’ll to also help us run our Bluedot Institute program, where he’ll be finding cool climate projects by students all over the country. Island poet and writer Laura Roosevelt is our new copyeditor; and graphic designer Whitney Multari creates our illustrations, ads, and newsletters (along with this magazine). Josh Katz is the man you need to talk to if you’d like to get your message across to our many thousands of ecoconscious readers with an ad in this magazine or our biweekly newsletters (write him at adsales@bluedotliving.com). (We really appreciate your support.)

Have a great spring, and we’ll see you at the Climate Fair at the Grange on May 7, from 12 - 4 pm.

Oh — and don’t forget to sign up for the Bluedot Living MV newsletter: bit.ly/MV-NEWSLETTER, and all our other newsletters (LA, San Diego, BuyBetter Marketplace, Brooklyn): bit.ly/Bluedot-Newsletters.

–Jamie Kageleiry

–Jamie Kageleiry

EDITORS' LETTER 4 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

Bluedot Living, right in your inbox! Get more yummy sustainable recipes, BuyBetter suggestions from our marketplace editor, great stories of locals tackling climate change, and advice from Dear Dot. Sign up here for our Martha’s Vineyard Bluedot Living newsletter, or our Hub (national) newsletter or any of our other locations: bluedotliving.com/newsletters ® Every

SIMPLE / SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES

other Sunday, Bluedot Living Martha’s Vineyard will share stories about local changemakers, Islanders’ sustainable homes and yards, planet-healthy recipes and tips, along with advice from Dear Dot. Did your friend send you this? Sign up for yourself here.

What. On. Earth.

Earth Day Matters

“But on April 22, 1970, after years of mounting concern and hard work, the first-ever Earth Day took place, and a new commitment to action took hold. Thanks in no small part to campaigns begun that day, our air, water, and land are in far better shape now than 45 years ago en as our population and economy have steadily grown.”

–John Kerry, April 21, 2015

1. Amount of oil in gallons per hour spilled for the first 11 days of the Union Oil off the Santa Barbara coast in January 1969: ~9,000

2. Amount of oil in gallons that had spread over 35 miles by the time Union Oil stopped the spill: 3 million

3. Where that Union Oil spill ranked in 1969 on list of the worst oil spills in U.S. history: 1

4. Where that Union Oil spill ranked 50 years later on list of the worst oil spills in U.S. history: 3

5. Number of years after Gaylord Nelson (U.S. Senator from Wisconsin) witnessed that Santa Barbara oil spill that he helped launch the first Earth Day: 1

6. Number of birds that died from the oil spill, according to the official count: 3,700

7. Number of birds that died from the oil spill, according to scientists: 9,000

8. Amount of straw in tons that the oil company used to try and mop up the spill: 3, 000

9. Number of citizens in millions who participated in the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970: 20

10. Percentage of the U.S. population that participated in the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970: 10

11. Number of months following the 1970 election that the Clean Air Act was passed unanimously in the Senate with just one dissenting vote in Congress: 1

12. Number of years Vineyard Conservation Society has been holding beach cleanups on Earth Day on Martha’s Vineyard, including this year: 31

13. Amount of trash cleaned up in a typical Earth Day beach cleanup on-Island: “Multiple tons”

SO WHAT CAN YOU DO?

Vineyard Conservation’s Annual Beach Cleanup: Saturday, April 22, 10 am to noon.

VCS will hold the first annual Earth Day Festival at the MV Museum on Saturday, April 22, from noon to 4 pm. More than a dozen local conservation organizations will provide educational presentations, and fun activities for the whole family to enjoy. All beach volunteers are encouraged to come and enjoy hot soup, bread, and other goodies. As a bonus, entry to the Museum is free! (MV Museum will also have food available for purchase in their cafe for those who did not clean a beach.)

Find out where you can meet to clean up those beaches: vineyardconservation.org/events

Sign up for VCS's newsletters to find out how to clean a beach in your town every month: bit.ly/VCS-newsletter

5

.com

marthasvineyard.

1-8: Smithsonian Magazine; 9,10: NOAA; 11: The Seattle Times; 12,13: Vineyard Conservation Society

Sources:

PHOTO COURTESY VCS

Buy Better Beautiful Homegoods

MADE ON

MARTHA'S VINEYARD

The Glassworks is dedicated to offering internship opportunities to local students. They also bring in off-Island glassblowers every summer and run a visiting artist program. “It's beneficial for the community, as well as supporting the glassblowing community at large,” says Sideman, who adds that education is a major component of the business’ mission. “We have lots of different projects and special events going on throughout the year where people can watch and explore,” he says. “There are sometimes visitors — kids or adults — who come and hang out all day.”

Martha's Vineyard Glassworks

Since 1992, a team of professional glassblowers has been creating artisanal work at MV Glassworks on State Road in West Tisbury. The studio/shop offers both standard designs that they developed and make onsite at the studio, as well as unique sculptural works of art. Each piece — from glasses, vases, and bowls to decorative tabletop ornamental pieces like an elegant clear glass pear or a colorful set of pumpkins — is a marvel of design and craftsmanship.

A visit to the studio shop offers a chance to see the artisans at work. The Glassworks currently employs four full-time glassblowers, all of whom have at least fifteen years of experience in the traditional craft. The business is divided into three sections — a shop and two galleries. The lower gallery features production works and design lines in multiple colors and size variations. The upstairs gallery offers a rotating selection of unique sculptural pieces.

Owners Andrew and Susan Magdanz have been in the glass business since the early 1970s. After running a private studio in Cambridge for many years, in 1992 they decided to bring locally made glass to the island that has been their summer home for decades.

In recent years, they have put into place some sustainable practices to reduce the business' carbon footprint. “We used to power our equipment with propane, but the technology for electric furnaces has advanced dramatically, and we switched to electric in 2021,” studio manager Wil Sideman says. “Our primary energy source now is electric.”

Last year the Glassworks added solar panels to the roof to cut back on their grid usage. “It's something we felt very passionate about,” Sideman says.

Carol and Richard Tripp – Woolen Goods

Not only does Carol Tripp hand loom all of her blankets, throws, shawls, ponchos and scarves, but she also handles every aspect of production from farm to market. Tripp and her husband, Richard, start by raising the sheep. Then she spins and dyes the wool and weaves it on a handloom (as opposed to a power loom).

According to Tripp, all of these things make a difference in

BUY BETTER/MADE ON MARTHA'S VINEYARD • UPFRONT 6 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

the look and feel of the finished products. “Part of the cachet is that our wool is hand spun, and it looks hand spun. There's texture and a not perfectly standardized quality to it.”

Hand looming makes for softer, more resilient fabric due to less compact weaving. All in all, with the slight variations in texture and weave, Tripp's products are unique and as close to those made in an earlier era as possible.

The Tripps own a farm in Lakeville, where they are currently raising seventeen sheep. They have six more at their home in Vineyard Haven. The flock is made up of Border Leicester sheep, which Carol prefers for the quality, softness, and luster of their wool. At the off-Island farm, Carol operates a studio for production and also teaches weaving.

The Tripps bought the derelict Lakeville farm in the 1970s, rehabbed it themselves, and started raising sheep for meat and wool. Before that, the two had worked as public school teachers at a Zuni reservation in New Mexico. It was there that Richard learned traditional Navajo weaving techniques. The couple still incorporates Native American patterns into many of their designs.

“I’ve always loved wool,” Carol says. “It's a battle, because people say that they're allergic or that it's scratchy, but if you use really good fleece, that's really not the case.” She also uses quality linens for some products and buys all of her dyes from a small company in Maine that sells non-toxic products, using only vinegar or salt for fixing.

“So much is made from petroleum products these days,” says Carol. “I like to keep everything as natural as possible.” You can get the Tripps’ woolen goods in season at the Chilmark Flea, and the Oak Bluffs Open Market.

SRS Grunden Pottery

Lovers of anything ocean themed will find numerous options for setting a Vineyard table at the SRS Grunden Pottery studio on the Vineyard Haven/Edgartown Road. Sherry Stevens-

UPFRONT • BUY BETTER/MADE ON MARTHA'S VINEYARD 7 marthasvineyard. .com

Interested in making your yard a haven for wildlife?

Grunden has been selling her hand-made ceramic wear from her home studio for more than ten years. There, you'll find a variety of attractive bowls, plates, platters, mugs and pitchers in Islandcentric shades of blue or brown.

Stevens-Grunden's work tends toward the traditional — sturdy and utilitarian. What sets her apart from other potters is the decorative work that embellishes many of the pieces. Fish, scallops, oysters, seahorses, and turtles adorn a series of mugs and pitchers; other designs include a simple heart, an outline of the Island with a wavy border, and a series of images of three different small invasive species — the clinging jellyfish, the vase tunicate, and the clubbed tunicate. Tunicates are small invertebrate sea animals that can be found attached to rocks, pilings and other hard surfaces; the clinging jellyfish clings to sea vegetation and has a potent sting.

These invasive species may seem an odd choice for an artist, but Stevens-Grunden's husband, Dave, is the former Oak Bluffs shellfish constable, and he suggested that these non-native creatures would add something unique to his wife's pottery line. She notes that she is now teaching Dave the ropes, so it would seem that the two have combined their interests in the small cottage business.

The SRS pottery line also features ornamental pieces made by using molds made from actual scallop and oyster shells. These are mounted on bases and used as tabletop accent pieces.

After working for pottery studios in North Carolina and Connecticut, Stevens-Grunden spent six years doing production work in England before moving to the Island. She refers to her designs as “very English shapes,” with trimming on the bottom. These simple designs allow for decorative work, although most of the artist's pieces are unadorned and rustic. The decorative elements are molded separately and added on, providing texture and a three dimensional look.

Join the Natural Neighbors Network

We'll visit your yard and give you site specific recommendations to create shelter, water, and food for pollinators, birds, and other wildlife. A site visit is free, and recommendations are designed to fit your needs and resources.

To sign up, contact Rich Couse rcouse@biodiversityworksmv.org

(508) 338-2939 office

The Oak Bluffs based couple sell their pottery from their studio/shop on their property and also at the Chilmark Flea Market and Oak Bluffs Open Market.

Shady Lady Lampshades

Debbie Kelly offers a unique way to add some personality to any décor. She creates one-of-a-kind lampshades using vintage fabrics in a variety of designs. Under the brand name Shady Lady, Kelly sells shades in all shapes and sizes featuring patterns ranging from mid-century modern to mod 1960s to rustic designs made from old grain and produce sacks.

BUY BETTER/MADE ON MARTHA'S VINEYARD • UPFRONT 8 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

Her most popular design is made from a fabric print of the old Eldridge's map of Martha's Vineyard — the perfect choice for any home with a maritime theme.

“What makes it really fun and challenging is finding interesting fabrics,” Kelly says; she scours yard sales, antique stores and thrift shops for colorful and unique designs. Some of her favorite fabrics include vintage barkcloth (a nonwoven fabric made from the inner bark of trees) and Marimekko fabric.

Kelly sells her shades at the Chilmark Flea Market as well as at Coastal Supply Company in Vineyard Haven. She has earned a loyal following at the flea market, where people often bring in their own lamp shades and/or fabrics for customizing and fitting.

The designer uses techniques that she learned on her own. She starts by molding adhesive styrene into the desired shape and then covers the panels with fabric and finishes with coordinating edging fabric along the seams. The artist notes that the styrene makes the shades heat resistant.

Kelly also sells tablecloths and napkins made from vintage fabrics. Her prices range from $20 for a night light to $80 for a large lampshade.

The self-taught artist loves the fact that she is bringing new life to discarded material. “It's recycling and turning something old into something new and modern,” she says.

UPFRONT • BUY BETTER/MADE ON MARTHA'S VINEYARD 9 marthasvineyard. .com Native plant specialists and environmentally focused organic garden practices. Design • Installation • Maintenance (508) 645-9306 www.vineyardgardenangels.com Garden Angels Bring beauty to your property

FIELDNote

To: Bluedot Living

From: The Vineyard Way (Connected to our Past, Committed to our Future)

Subject: 2023 Climate Action Fair, Sunday, May 7

Protecting a small Island resort community won’t be a priority when major coastal cities are inundated with sea water. Here on the Island, we need to become as self-sufficient as possible. We can’t stop the sea from rising or the storms from doing damage, but every one of us can make a positive difference.

Reuse, Repair, Renew

• Everything we buy contributes to the climate crisis. Material goods consume natural resources, and shipping them to the Island burns fossil fuels.

• Everything we throw away costs money to take off-Island

and pollutes someplace else.

• Every tree we cut down no longer provides shade or absorbs greenhouse gases.

• Every non-renewable source of energy we use makes matters worse.

• The theme of the 2023 V ineyard Climate Action Fair is Reuse, Repair, Renew.

Come to the fair to learn how to:

• repair your bicycles

• mend your clothes instead of throwing them away

• compost your food waste - help your garden grow and save the towns money trekking it off-Island

• landscape in a way that protects plants, trees and the biodiversity they provide

Talk to experts about:

• how you can afford to put solar panels on your home

• home energy efficiency

• And more:

• talk to electric vehicles owners about their cars

• learn about the Vineyard Climate Action Plan and the more than 200 actions it includes to build a climate-resilient Island

• revel in the beauty of the Vineyard Conservation Society’s student art contest submissions

• eat, drink, dance a bit

• L ooking after the Island doesn’t have to be painful. It can be fun. It’s essential, and it’s everyone’s responsibility.

Climate Action Fair; Agricultural Hall; Sunday, May 7; 12 pm – 4 pm

Support Bluedot!

We love bringing you stories about Islanders addressing climate change. Generous contributions from readers such as you helps us do this. Make a one-time, monthly, or annual contribution here.

https://bit.ly/mv-bdl-member

10 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

FIELD NOTE

we’ll email you a downloadable collection of Bluedot Kitchen Recipes

And

“We must rewild the world,” said none other than Sir David Attenborough, natural historian and creator of iconic nature documentaries.

Which means … what exactly? I think back on a winter visit to Jackson, Wyoming, where an elk was window shopping in the town square, and to the Bangkok market where I watched a monkey wreak delightful (to me!) havoc, leaping from display to display.

An online dictionary uses “rewilding” in this sentence:

folks at Rewilding Britain, whose slogan is “Think Big, Act Wild.” The term itself was coined in the early 1990s by Dave Foreman, co-founder of Wild Earth magazine and The Wildlands Project, according to the podcast Rewilding Earth.

20, 2021. Though I missed the occasion, the rewilding initiative is growing like, uh, rewildfire. Originally conceived as a North-America-wide initiative focused on the three conservation Cs (cores, corridors, and carnivores), rewilding has expanded to South America, Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and more.

Rewilding? Might be a bit of a tough sell.

But in point of fact, rewilding isn’t nature encroaching on our human environment so much as it is giving nature back to its non-human inhabitants. It’s “restoring ecosystems to the point where nature can take care of itself,” say the

The Global Rewilding Alliance, a network of more than 125 organizations, was formed in 2020 to create and promote rewilding projects around the world. “We believe that the world can be more beautiful, more diverse, more equitable, more wild,” reads the group’s charter.

To that end, the Alliance organized the world’s first rewilding day on March

Rewilding typically refers to largescale projects — restoring the natural course of rivers and reconnecting them with floodplains, creating wildlife corridors or moving wildlife to decimated areas to restore biodiversity, cultivating kelp forests and marine ecosystems. But micro rewilding, as it’s called, plays a key role too. Siân Moxon, the founder of Britain’s Rewild My Street, told a reporter that micro rewilding can be as simple as planting a tree, adding a bee bowl or bird bath to your garden, or encouraging vines to climb the side of your home. The good news about micro rewilding is that neatness is out. Nature, says Moxon, is messy. And wild.

–Leslie Garrett

“ IN A WORD 11

.com

marthasvineyard.

Rewild /rē ' wīld/ in a word

C R A F T CA N N A B I S doog h e a l th good co n d ition . LOCALLY GROWN. LOCALLY ENJOYED. 510 State Rd, West Tisbury, MA 02575 • 508.687.0131 • finefettle.com breast-feeding may pose potential harms. It is against the law to drive or operate machinery when under the influence of this product. KEEP THIS PRODUCT AWAY FROM CHILDREN. There may be health risks associated with consumption of this ed by two hours or more. In case of accidental ingestion, contact poison control hotline 1-800-222-1222 or 9-1-1. This product may be illegal outside of MA. WALK-INS WELCOME

PHOTO BY CAROL VEGA

"Talk of rewilding North America gives some people nightmares of wolves running through the streets of Chicago and of grizzlies in LA"

Dear Dot,

I thought the House Finches were wiped out a number of years ago by a disease that made them blind. Have they made a comeback?

Dear Marie,

–Marie, Brooklyn, NY

You write to me from Brooklyn, having seen, no doubt, Bluedot’s Brooklyn Bird Watch (bit.ly/Brooklyn-bird-watch) featuring those red-headed charmers, House Finches.

These perky peepers are indeed prone to Mycoplasmal conjunctivitis, or House Finch Eye Disease, confirms Pat Leonard, who works in media relations at the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology. Finches with the disease show red, swollen, runny, or crusty eyes. And, as you suspected, Marie, in extreme cases, the bird’s eyes swell shut and they become blind.

I will pause here for a moment while we all absorb the tragedy of these birds being unable to see and, therefore, perform any of the functions necessary for survival. I recall the words of poet Mary Oliver, appropriate to this particular anguish, who wrote: “... it is a serious thing/just to be alive/on this fresh morning/in the broken world.” Her subject matter was Goldfinches, who also suffer from this debilitating disease.

The bacterium Mycoplasma gallisepticum has long afflicted chickens and turkeys, though for those fowl, it manifests as a respiratory issue. But in 1994, Pat Leonard tells us, backyard bird watchers around Baltimore began sending the volunteers at Cornell’s Project Feederwatch handwritten reports of house finches with crusty, red eyes almost bulging from their heads.

All About Birds, Cornell’s online guide to birds, tells us that, at that point in the early 90s, house finches were an enormously successful species and a familiar site at backyard feeders. And then, this poultry pathogen leapt across species.

Scientists, acting like scientists and not eco-advice columnists, viewed this as something of an opportunity to watch a disease

dot DEAR

spread in real time and to gather data. (Though I like to think they shed a few tears before getting down to work.) They mailed paper forms to thousands of bird lovers across the country — this was largely pre-Internet, of course. And then they waited.

Finches are rather fascinating, Marie. Cornell University’s All About Birds site (bit.ly/House-Finch-disease) discloses that finches are desert and grassland birds but amazingly adaptive, clearly, to non-desert environs. Around 1940, some enterprising folks in California created an illicit trade in captive finches, branding them “Hollywood finches,” a moniker undoubtedly aimed at conjuring glamor and opulence. But the nascent jig was up when an eagleeyed birder spotted a caged house finch in a Brooklyn pet store and contacted the Audubon Society, who alerted wildlife officials to shut down the illegal trade. Many with caged finches in their possession, fearing prosecution, quickly ushered their avian abductees out the door and into the wilds of New York City, where the birds were delighted to take a bite out the Big Apple — until the wicked winter of 1947/48 left just about 50 finches still alive. But that few dozen offered enough of a foothold that an Eastern population of House Finches was flourishing by the ’60s and making its way west at the same time the Western population was heading east. By the ’90s, the two populations were conquering the continent. All hail the mighty House Finch!

And then [ominous music], enter the mysterious eye illness.

Meanwhile, at Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology, a Belgian guy named André Dhondt had relocated to lead its Bird Population Studies program. He and his researchers spent about a decade gathering several hundred thousand reports from about 10,000 dedicated citizen scientists monitoring their feeders and the finches for evidence of this novel disease. The disease itself was much more expedient, spreading from its first sightings in Maryland into Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and even Canada in just two and a half years. But finally the culprit had a barely pronounceable name: Mycoplasma gallisepticum.

12 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

Illustration Elissa Turnbull

Scientists learned that the birds that survived developed something of an immunity to the pathogen for roughly a year postinfection. But the pathogen would then grow more virulent, causing a greater immune response in the surviving birds, and so on. You ask, Marie, whether House Finches were wiped out. They remain unflinchingly, finchingly stalwart — indeed Pat Leonard assures me that Cornell lists them as “a species of Least Concern with an increasing population” — but that’s not for lack of trying on the part of Mycoplasma gallisepticum

Here on the Vineyard, Matt Pelikan, bird lover and director of the MV Atlas of Life project, says that the disease had “put a crimp in the house finch population but certainly didn't wipe them out, either locally or more broadly in the region.” He’s seen House Finches on the Island that showed what appeared to be symptoms, but, he told me, like a lot of wildlife diseases, this one tends to be cyclical in occurrence, and he hasn’t seen signs of it lately.

But that does not mean we can rest in our battle against this foe, we soldiers of the House Finch army. If you and your friends have backyard feeders, Marie, keep them clean. This eye disease is strongly associated with feeding stations, which bring unnaturally large numbers of individual birds together in a place that basically has a communal dinner bowl, providing, Pelikan notes ominously, “prime conditions for a disease to spread.” Therefore, he adds, “bird lovers who want to reduce the impacts of the disease should practice rigorous feeder hygiene, washing feeders regularly with a disinfectant such as bleach.” (Nine parts water to one part bleach, the Cornell folks recommend.) Indeed, Pelikan says that, while

he’s not personally opposed to bird feeders, we might want to think twice about using them, because, in addition to helping spread disease, feeders, by concentrating birds, “turns them into a rich target for hawks and cats, put birds in proximity to windows, which they can smack into and injure or kill themselves, and alter the natural diet of birds and their pattern of distribution, with effects that are hard to predict but don't reflect what the birds evolved to do,” he says. “One should be aware of the risks as well as the benefits,” he sagely imparts.

If you think the balance leans toward bird feeder benefits, then, to further reduce the potential for disease, rake the area beneath the feeder to disperse any moldy seed. And space your feeders far enough apart that birds have room to spread their wings, metaphorically and literally. It turns out that social distancing helps prevent the spread of viruses in birds as well as people. If you notice sick birds (the eye disease isn’t the only illness, and House Finches aren’t the only birds afflicted), take down your feeders, clean them, and wait a few days for any sick birds to disperse before putting them up again. And calling all citizen scientists! Sign up for Project Feederwatch (bit.ly/ feeder-watch) and help provide valuable data to our bird-loving researchers. Warblingly, Dot

Please

DEAR DOT 13 marthasvineyard. .com

KEEP READING THIS MAGAZINE FROM WHEREVER YOU ARE Subscribe now, and we’ll mail Bluedot Living directly to you Four annual issues plus our Green Guide is $40 and we’ll send you a downloadable collection of Bluedot Kitchen Recipes. Email us at subscriptions@bluedotliving.com Reach 55,000 eco-conscious readers in our print magazine and email newsletters, for as little as $100 a week. Get in touch! adsales@bluedotliving.com Advertise with us! THE HUB / MARTHA’S VINEYARD SAN DIEGO / LOS ANGELES BUYBETTER MARTKETPLACE BROOKLYN / BLUEDOT KITCHEN

send your questions to deardot@bluedotliving.com

Salt Marshes

Learning to treasure

SALT MARSHES • FEATURE 14 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

Story by Sam Moore

“the low green prairies of the sea.”

“one of the most satisfying drinks of color my eyes ever tasted.”

– the Massachusetts naturalist Dallas Lore Sharp

SSalt marshes don’t always inspire affection, but when they do, it can be intense. In 1902, the Massachusetts naturalist Dallas Lore Sharp dedicated an essay to salt marshes in The Atlantic, calling them “one of the most satisfying drinks of color my eyes ever tasted.” There was, he continued, “no other reach of green so green.”

The marsh is both boundary and buffer — at the edge of the sea, it dampens wave action from storms, sequesters carbon, filters water, offers finfish and shellfish a protected nursery, and draws a sharp line at the end of many coastal walks.

“It's a stunningly beautiful and productive habitat, visually, ecologically,” said Suzan Bellincampi, Mass Audubon Islands Director and another disciple of the marsh. “And the fact of the matter is, the land is more useful than most people can even imagine, especially now.”

15

.com FEATURE • SALT MARSHES

marthasvineyard.

Suzan Bellincampi and a volunteer on the shores of Sengekontacket.

Marsh grasses at Sengekontacket.

PHOTO BY ALISON SHAW

COURTESY MASS AUDUBON

Useful is an adjective that has waxed and waned in this landscape. To the Indigenous peoples along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, marshes have been indispensable, with whole ways of living timed to this coastal abundance, fish and shellfish used for food, wildflowers used for dye. Tribes including the Wampanoag continue as stewards in these ecosystems today.

Settlers found use for marshes, too, particularly in fishing and farming. They set their hogs loose to snort around the mud flats for clams, and fished themselves for eels — buckets, baskets and bushels full. “Eels ran so thick that we first thought them sea grass,” wrote a colonist in 1634. “Not of so luscious a taste as they be in England,” he sniped, but “wholesome for the body.”

Europeans harvested salt hay for their livestock and thatched houses with it. The hay harvest was set to the tides, first according to a trusted few with knowledge of the moon, later according to a farmer’s almanac. When the tides ran low, the cut grass would stay dry, and during these times, men with scythes would make hay, as they say, while the sun shone.

The cattle and horses already had a taste for marsh grass, and the colonists figured that “the air of the sea whets

their appetites.” Horses wore special shoes for walking in the marsh muck, wide wooden ones that spread their weight out as they trudged across the spongy peat.

One motivation for opening the great ponds on the South Shore of Martha’s Vineyard was to lower the water enough to harvest the salt hay — which included the soft “black grass,” Juncus gerardii, more accurately called the saltmarsh rush, as well as the plentiful saltmeadow cordgrass, Spartina patens.

Sharp, the naturalist, loved these grasses, which “covered the marsh like a deep, thick fur, like a wonderland carpet into whose elastic, velvety pile my feet sank and sank, never quite feeling the floor. The tints, shading from the lightest pea green of the thinner sedges to the blue green of the rushes, to the deep emerald green of the hay-grass, merged across their broad bands into perfect harmony.” John Greenleaf Whittier called the vast marshes on the mainland “low green prairies of the sea.”

Salt hay was part of a resource-intensive colonial food pyramid, an insatiable need for one commodity, hay, to feed another, cattle, as cheaply as possible. As settlement pressed from the margins of the continent inward, chasing new business models, people in power began to think of salt marshes as a problem that needed solving. One rationale followed another for ditching, draining, and filling them.

In the 19th century, Federal Swampland Acts encouraged the “reclamation” of wetlands for farmland, and developers in booming cities used garbage and gravel to make marshes into new neighborhoods like Boston’s Back Bay. In the 20th century, after mosquitos were identified as a vector for disease, the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps went

16 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

Geese at Farm Pond, Oak Bluffs.

SALT MARSHES • FEATURE

Grasses at Lagoon Pond.

into almost every marsh in the Northeast and dug ditches for standing water drainage — the ruler-straight channels we see today.

In total, Massachusetts has lost 40% of its salt marsh in the last 200 years, according to a study of historical maps. Another estimate, by the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, put the net loss of marsh on Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and the Elizabeth Islands over just the last century or so at about 375 acres, an area about the size of Squibnocket pond.

“Before people really understood the value of salt marshes, we kind of destroyed them,” Bellincampi said. “And now it's a coastal resilience imperative.”

Extensive marshes remain on Martha’s Vineyard on Chappaquiddick, in Pocha Pond and Cape Pogue bay, and between Oak Bluffs and Edgartown, in Senge-

FEATURE • SALT MARSHES 17 marthasvineyard. .com

Sharp, the naturalist, loved these grasses, which “covered the marsh like a deep, thick fur, like a wonderland carpet into whose elastic, velvety pile my feet sank and sank, never quite feeling the floor. The tints, shading from the lightest pea green of the thinner sedges to the blue green of the rushes, to the deep emerald green of the hay-grass, merged across their broad bands into perfect harmony.”

Poucha Pond.

PHOTOS ALISON SHAW

kontacket, where they are protected by a long barrier beach. Other patches can be found all over the island — hugging inlets and shorelines of Menemsha, Katama Bay and Tashmoo, and scattered in

nooks across the Island’s great ponds. These landscapes are more protected now, and their losses have slowed thanks to federal and state legislation. But drawing lines around the marsh doesn’t

prevent it from changing in dramatic and sometimes alarming ways. Marshes are highly adaptable, but one thing they have not evolved to do is stay still.

Sergio Fagherazzi, a coastal geomorphologist at Boston University who studies salt marsh deposition, has written that salt marshes are “ephemeral landforms at the geological time scale,” that are “constantly reworked by coastal processes within a few thousand years, in a rejuvenation process.”

Marshes build up vertically, as vegetation traps sediment and generations of plants die and become peat. They also travel horizontally, as marsh grasses spread their rhizomes underground, send their seeds by wind and tide, or break off pieces of themselves that become new plants. They are eroded by coastal

SALT MARSHES • FEATURE 18 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

Protecting this ecosystem can mean restoring tidal flow and remediating ditches, but it also means making room for the marsh to move — maintaining undeveloped land where new marsh can form as old marsh is lost, rising inland and upland with the level of the sea.

Sengekontacket shoreline.

PHOTO ALISON SHAW

storms, and sometimes even calve like glaciers, splitting off “marsh bergs” that float away to wind up somewhere else.

They expand quickly seaward or landward as conditions allow, and contract even more quickly when conditions require. They can fill in behind a newly formed barrier beach, or inch up a tidal creek as freshwater retreats. They are ecosystems fine-tuned to a changing coastline, to the flux of sediment generated by elemental forces. “Compared to the history of Earth, a salt marsh

resembles a gorgeous butterfly,” Fagherazzi writes. “After emerging from the cocoon, it extends its wings under the morning sun, rises in the sky during the day, and when the night falls, it folds its wings and dies.”

Protecting this ecosystem can mean restoring tidal flow and remediating ditches, but it also means making room for the marsh to move — maintaining undeveloped land where new marsh can form as old marsh is lost, rising inland and upland with the level

of the sea. I read that shoreline change arrives as a “pulse” of big, sudden storms over the “press” of the steadily higher ocean. Together these forces are an “ecological ratchet,” pushing freshwater trees and plants out and up, pulling salt grasses in.

The state has identified upland areas on Martha’s Vineyard that are crucial to protect as marshes rise, and the Martha’s Vineyard Commission is planning and mapping for the future to come. A recent study of Sengekontacket, funded by the Village and Wilderness Project, identified around 170 acres of land fringing the pond that could become marsh in the next 30 years, if preparations are made — enough to offset even a total loss of what’s there now.

Bellincampi often takes preschoolers into the Sengekontacket wetlands around Felix Neck. “They actually love to get their rubber boots on,” she told me. “It’s just amazing watching them stomp through the marsh. You never know what you're going to find out there — all the life, the little fish darting around, the holes for the crabs, the Spartina patens and alterniflora, depending on where you are in the marsh, the salt marsh asters and

FEATURE • SALT MARSHES 19 marthasvineyard. .com

Bellincampi often takes preschoolers into the Sengey wetlands.

Bellincampi and volunteers at Felix Neck, on Sengekontacket.

COURTESY MASS AUDUBON

all the flowers. Damselflies, dragonflies.” I, myself, am partial to seaside goldenrod, Solidago sempervirens, a perennial which grows at the edge of the marsh, blooming in dense bursts of yellow.

“Osprey like to hang out on the edge,” Bellincampi added, “on the beetlebung at Felix Neck. And then they'll just go down and get fish.” There are owls there, too. Sharp, the naturalist, encountered one at dusk and wrote: “What was I that dared remain abroad in the marsh after the rising of the moon? That dared invade this eerie realm, this night-spread, tide-crept, half-sealand where he was king?”

The saltmarsh sparrow is another

bird whose way of life is carefully tuned to the insects, grasses, and tides of this landscape. This bird nests in the high marsh, and races against the moon to lay eggs, hatch chicks, and raise them to fledglings in the few weeks before a big tide returns to drown the whole operation. Four out of every five saltmarsh sparrows have disappeared since 1998.

The sparrow, like the coal mine canary, indicates bigger problems on the horizon, as climate change causes continuing sea level rise and an increase in major storms. If the marsh disappears, a lot more will be lost. “It’s the buffer, it’s the protection zone,” Bellincampi said. “You

think of big strong trees, but the strength of the marsh is these little grasses and mud and detritus.”

“We have to protect and do our best to preserve what we have,” Bellincampi said, “because we've lost so much of it.”

The salt marsh, insect-laden, squelching with mud, has managed to gather a lot of admirers — myself among them. But I can’t do it justice in words like a gilded-age naturalist. “When I catch that first whiff of the marshes after a winter,” Sharp wrote, “the smell of it stampedes me. I gallop to meet it, and drink, drink, drink deep of it, my blood running redder with every draught.”

What you can do

• Check out this StoryMap on Vineyard marshes by Chris Seidel and Dan Doyle at the MVC: bit.ly/story-mapmv

• Take a walk in the marsh

• Read the Sengekontacket case study (great maps): bit.ly/sengey

A SHARING OF MEANS • FEATURE 20 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

Salt marshes on Martha's Vineyard.

Swans at Mill Pond.

PHOTO ALISON SHAW

MAP BY SAM MOORE

EDIBLE BACKYARDS

How to Plant a Fruit Tree Guild And enjoy the fruits of your labor

Spring signals a return to gardening — and also to the time for planting fruit trees.

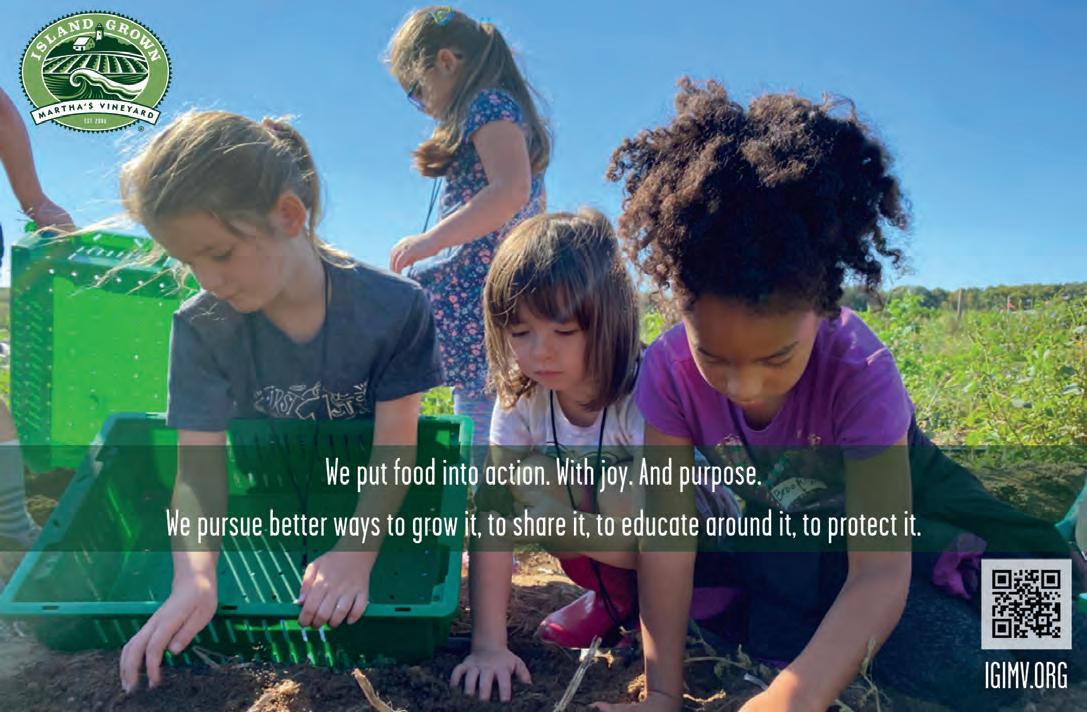

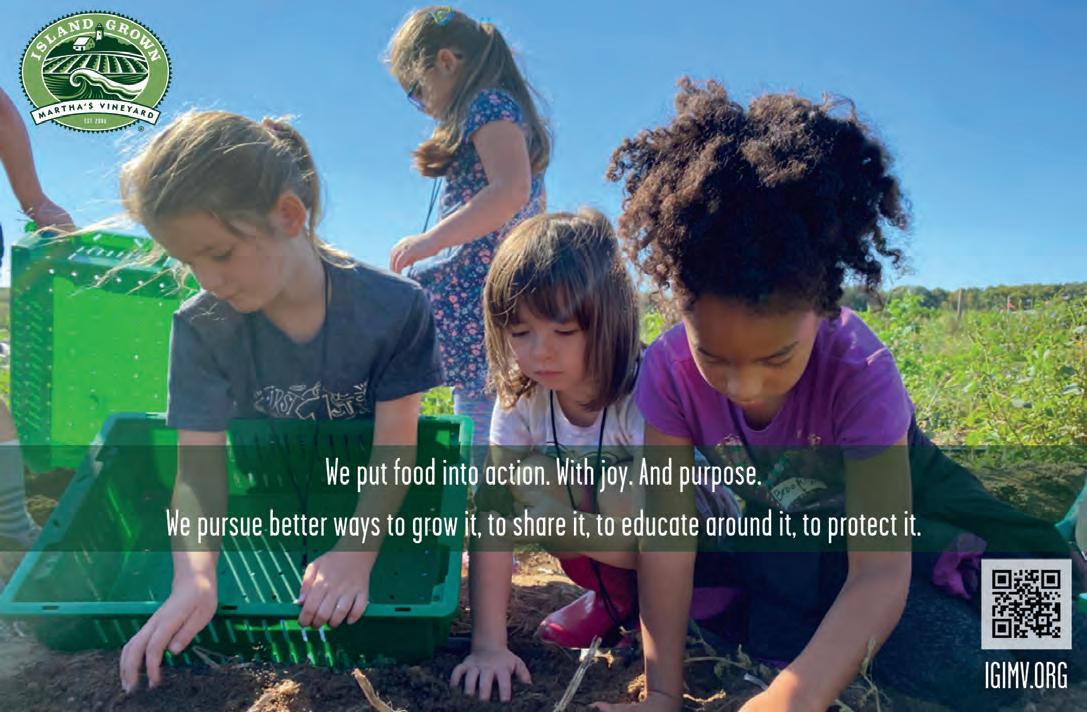

Garden educator Roxanne Kapitan outlines a better way to grow fruit trees, one that ditches traditional fruit tree inputs like fertilizers, fungicides, and chemical sprays, and relies instead on plants. It’s called a fruit tree guild, or companion planting, and it’s a more sustainable approach to planting with a lower carbon footprint.

Each guild involves one fruit tree and includes 6 or 7 species planted around it. Those companions — often edible themselves — each fulfill a particular job such as mulching the wide circle around the tree, adding nutrients to the soil, repelling unwanted insects, and attracting beneficial insects.

"Instead of having one type of plant, such as an apple tree, each tree has a community of plants around it that support the tree in a variety of ways,”

says Kapitan, who explains that this type of planting in permaculture gardening mimics nature. “You rarely see monoculture in nature; you see a community of plants. Most of the fruit trees in guilds do remarkably well.”

Kapitan, a former science educator turned gardener and landscaper, is turning back to educating again, and using her own Oak Bluffs property as a teaching

model. Over the past three years, she’s transformed her moderately sized backyard (125x70 feet, formerly filled with a mix of grass, weeds, poison ivy, and tangles of vines) into an educational and edible landscape or food forest where she holds some of her classes, many sponsored by Island Grown Initiative. The size of her yard shows homeowners that they don’t need acres of land or a traditional orchard, but can enjoy the

21 marthasvineyard. .com

Story by Catherine Walthers Photos by Sheny Leon

“Instead of having one type of plant, such as an apple tree, each tree has a community of plants around it that support the tree in a variety of ways.”

– Roxanne Kapitan, Garden Wisdom

fruits of their labor, so to speak, with just two or three or five fruit trees. Kapitan also has another educational garden on a private property in West Tisbury which she calls a “Garden of the Future.'' There, she is experimenting with growing only edible perennials in an eight-sided plot.

“People are looking at the idea of edible landscapes much more seriously than they ever have,” she explains. "It’s the fastest growing gardening trend there is.”

Six fruit guilds form the backbone of Kapitan’s new backyard landscape, slightly overlapping circles or guilds lining a short curvy path that ends at her newest addition, a pond with a waterfall. There are three apple guilds with Macoun, Empire, and Liberty apples, each supported by the chosen helpers. “Those are the three apples I love to eat,” she says. She first learned about Liberty apples, a wonderfully crisp, sweet-tart apple that grows well in New England, when she owned her first plant nursery on Summer Street in Tisbury. She also planted two pear guilds, one with Bartlett pears and the other with Anjou.

The sixth guild features a self-pollinating mulberry bush producing black berries from late June into summer, which are “delicious,” according to Kapitan. Mulberries taste and look a bit like blackberries, and are a good source of iron, Vitamin C, and several plant compounds linked to lower cholesterol, blood sugar and cancer risk. “I just eat them,” she says. "I go out there and graze."

Kapitan hasn’t bought a single bag of fertilizer or mulch, nor sprayed anything

EDIBLE BACKYARDS • FEATURE 22 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

Kapitan hasn’t bought one bag of fertilizer or mulch, nor sprayed anything on her trees. And that’s the point.

Roxanne Kapitan in her backyard, where she is planting species to create a fruit tree guild.

Fruit Tree Guild Companion Planting

Suppressors

Plants that help suppress grass

Daffodils, Iris, Chives, Leeks, Garlic

Attractors

Plants that attract a variety of beneficial insects, and that help pollinate Dill, Fennell, Coriander

Repellers

Plants that repel potentially damaging insects

Nasturtium, Marigold, Rue

Mulchers

Plants that naturally provide mulch Rhubarb, Comfrey, Borage

Accumulators

Plants that increase nutrient content of the soil

Yarrow, Chicory, Dandelion

Fixers

Plants that increase the amount of nitrogen in the soil

Clover, Beans, Alfalfa, Peas

Classes can help you learn all about edible back yards. Read about them here: bit.ly/41ajEMK

FEATURE • EDIBLE BACKYARDS 23 marthasvineyard. .com

IRIS

FENNEL

BORAGE

ALFALFA

NASTURTIUM

DANDELION

on her trees. And that’s the point. She planted young fruit trees from a nursery (rather than bare rootstock, which can take three to five years to produce fruit), and as a result, she picked apples the first year and has since enjoyed a modest harvest each fall as the trees grow and thrive.

The first thing to understand about fruit trees, Kapitan explains, is that they don’t fare as well with grass growing beneath them, despite all the bucolic images of apple orchards amidst grass. Grass competes with fruit trees for nutrients, especially nitrogen, which is the second most important element for an apple or fruit tree after water. "Grass needs lots of nitrogen, so do fruit trees," says Kapitan. Perennial plants such as irises or daffodils, called suppressors in this type of planting, keep grass and weeds from encroaching near the tree base, as their shallow root rhizomes spread and help suppress grass growth. As an added bonus, these bulbed plants go dormant in the summer and so do not take valuable water and nitrogen away from the thirsty apple tree when rainfall is likely to be scarcer.

don’t need to irrigate, because you have all this mulch on top of the base of the fruit trees.” Natural mulch also decomposes, adding additional nitrogen back into the soil, helping to negate the need

Kapitan planted young trees, rather than rootstock, and has enjoyed a modest harvest each year since.

turn feed on the codling moth, a medium-sized light brown pest which attacks both pear and apple trees by laying eggs on the fruit as well as tunneling inside the fruit to feed on the seeds.

Traditional orchards use a variety of sprays with chemicals like malathion or carbaryl to prevent insect damage such as this, as well as fungus and other infections that can wreak havoc in an orchard. “Spraying, right away, has a large carbon footprint. This is not sustainable.”

Finally, you also need plants known for drawing nutrients from deep in the soil. “Those are dynamic accumulators,” Kapitan explains. "It's a big word, but their long taproots simply go down and bring up minerals deep within the soil and make them accessible to the fruit tree. All of this is so you don’t have to go out and buy granulated fertilizer.”

Kapitan appreciates that her fruit trees and the accompanying guilds provide her with both fresh food right from her backyard and a lovely, serene landscape. “Starting with iris, then comfrey, then marigolds, there’s a constant flowering,” she says. The gurgling waterfall in her pond not only blocks out traffic noise but also makes it “Zen and very peaceful.” The pond performs an additional function of attracting different bird species and frogs that help keep insect populations balanced, further protecting her fruit trees.

The mulchers around the tree, including plants like rhubarb with large leaves that drop after a spring harvest, or borage with good-sized leaves and edible blue or white flowers, act as other mulches do, holding in moisture and keeping out weeds.

“This chop-and-drop plant mulch is very important,” she notes. “Now you don’t have to buy mulch, and maybe you

for purchased fertilizer. “All that stuff from outside your yard is another huge carbon footprint,” she emphasizes.

In this permaculture guild system, some plants, such as edible nasturtiums or lemongrass, repel potentially damaging insects, while others attract beneficial ones, including those that pollinate the trees. Plants like dill, fennel, and cilantro attract beneficial wasps which in

Fruit trees take some dedication and work, she says, and that includes learning to prune branches sometime between November and early March when the tree is dormant to keep the trees healthy and productive. “It’s much easier to grow raspberries,” she says, half jokingly.

Thanks to her role as the landscape manager at Oak Leaf landscaping for the past 12 years, Kapitan’s handiwork

EDIBLE BACKYARDS • FEATURE 24 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

“Permaculture is the harmonious integration of plants, animals, and human systems that create a closedloop system.”

–Kaila Binney, permaculture instructor

can be seen around the Island, including some beautiful high-end herb gardens, enclosed blueberry and raspberry patches, and managed vegetable gardens. She has always been a proponent of organic growing and of making and using compost from discarded food and yard materials, but in recent years, she also began studying permaculture, food forests, and her newest experiment, a fully perennial edible garden. It inspired her to start her own business, Garden Wisdom, through which she hopes to install more edible landscapes Islandwide and to continue teaching better, more sustainable growing methods.

She studied permaculture here on the Island with teacher and Chilmark resident Kaila Binney, who first studied it in Malaysia and elsewhere, and lived in an eco-village that practiced its methods. Binney describes permaculture as the harmonious integration of plants, animals, and human systems that create

a closed-loop system. Binney eventually moved to Martha’s Vineyard to share her knowledge, and she now runs the Woods School, a cooperative, nature-based homeschool on the Island.

Homeowners can start small and still make a big difference — that’s the good news, Binney says. By simply drawing a circle and plugging in a couple things like clover instead of grass, you can begin to create the microclimate fruit trees need to survive. And, she adds, you don’t need to start from scratch with new fruit trees. In her own

yard at Allen Farm, she did an experiment with two established peach trees, two inside the garden and two others elsewhere on the property. She planted two comfrey plants around the trees in the garden.

“The ones in the garden are exponentially more productive, and it’s really so simple,” she said.

Kapitan expands on this: “When I first started gardening, I used to think I was growing the plants,” she says. “Now, after 30 plus years, I realize that the plants are growing me."

25

.com

marthasvineyard.

“People are looking at the idea of edible landscapes much more seriously than they ever have. It’s the fastest growing gardening trend there is.”

– Roxanne Kapitan, Garden Wisdom

Kapitan appreciates that her fruit trees and the accompanying guilds provide her with both fresh food and a lovely, serene landscape.

Garden to Table,

All Year

Long

Spring’s the time to start planning. And planting!

Story by Laura D. Roosevelt

Story by Laura D. Roosevelt

GARDEN TO TABLE • ALL YEAR LONG 26 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

““My goodness!” a guest remarked at dinner, looking out through the windows of my screen porch toward my vegetable garden. “It’s so lush! What are you growing?”

I didn’t hesitate. “Weeds,” I replied. That was twenty years ago, when I had young children, a job freelancing for one of the local newspapers, and nowhere near enough time to keep up with my garden, which is the size of a tennis court.

Happily, now that my kids are grown, my garden gets neater and more productive with each new summer. For the past several years, I’ve been proud to tell anyone who’ll listen that from July to the end of October, I pretty much don’t set foot in the supermarket’s produce section, instead planning meals around what’s ripe and ready just outside my back door.

Inspired by Barbara Kingsolver’s Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, a memoir of a full year she and her family spent eating locally (the output from their own farm and garden, supplemented by goods from other producers within a 100-mile radius), last summer I took things to the next level: I decided to plan my garden with a view to eating its bounty all through the winter and following spring. Like Kingsolver, I was troubled to learn that the average item of food on an American’s plate has traveled over 1,500 miles to get there, in vehicles that burn fossil fuels and emit carbon monoxide all along the way. And I dislike the idea of genetically modifying fruits and vegetables to make them less perishable — a measure that often results in less flavorful (and sometimes less nutritious) food. (Try comparing a supermarket strawberry to one from a local farm and you’ll see what I mean about the flavor.) Even worse is the common food industry practice of picking produce before it’s ready and then gassing it after transport to “ripen” it, and/or using preservatives and irradiation to keep it stable for travel. To lessen my incidental support for all these procedures, I made a goal of eating at least some produce from my own garden all year long.

I started small, selecting just over a half dozen items that I expected would last well, either in the relative cool of my

basement (the closest thing I have to a root cellar), in my freezer, or in mason jars. For basement storage, I planted garlic, red onions, and butternut and red kabocha squashes; for freezing, sugar snap peas and string beans; and for pickling, cucumbers and shishito peppers. I’d hoped also to can some tomatoes, but my crop was diminished by blight and a horde of hungry chipmunks, and I didn’t get enough fruit. Better luck next year.

My “root cellar” foods have held up wonderfully. I’m writing this in late February, and I still have about 50 heads of garlic that show no signs yet of sprouting or shriveling (though both will occur sooner or later). Ten braids of red onions (with a dozen or so onions per braid) remain hanging from nails I drove into the basement’s ceiling joists. Some individual onions have begun sprouting, which is the beginning of the end for them. Once the sprouts get long, the body of the onion itself is starting to rot and is not something you want to eat. (When this happens, I cut off the green sprouts and use them as scallion substitutes, so at least I get something out of it, and the rest of the now inedible onion goes into my compost.) The larger onions tend to sprout first, but I’ll probably be eating the smaller ones for at least another month. As for the squashes, I still have about 20 left, and they look as good as any you’d find in Stop & Shop.

I’ve used up almost all of the beans and sugar snaps I froze, whereas the pickles … well, it turns out I don’t eat pickles very

often, so these may still be languishing in my pantry when it’s time to start pickling next year's cukes and peppers.

Over the next year, I’ll be writing about what you should be doing at given points in the year in order to maximize off-season eating from your own gardens. Note that I am writing from Martha’s Vineyard, which is in hardiness zone 7. Planting schedules, soil temperatures, and even what you can successfully grow will vary according to your region’s hardiness zone, so be sure you know your zone and how it affects what you can do in the garden. See Planting zones to find your zone, and plants in your area for a good introduction to what you can plant in your area. In zone 7, it’s too late for you to enjoy homegrown garlic this year, since it’s planted in the late fall for harvesting the following summer, but everything else I

ALL YEAR LONG • GARDEN TO TABLE 27

.com

marthasvineyard.

Over the next year, I’ll be writing about what you should be doing at given points in the year in order to maximize off-season eating from your own gardens.

preserved for this winter (and much more) can be planted at various points from now to midsummer. A few tips:

SUGAR SNAP PEAS (and snow peas, if you prefer them or want both) should be in the ground by the end of April, as they don’t like hot weather. If you’re running late, there’s a trick that makes them emerge faster: Start by soaking the seeds overnight in a bowl of water. The next day, drain them, then fold them in dampened newsprint. Keep the newsprint moist for the next two days, then check the peas daily. When they’ve started to sprout, plant them, and they’ll be up before you know it. Peas need to grow on trellises, to which they fasten themselves with their own tendrils. (Sometimes a twist-tie or two is helpful to keep vines grown heavy with pods attached to the trellis.) My “trellis” is chicken wire stretched between tall stakes — at least six feet high, as peas are vigorous growers.

STRING BEANS come in many varieties. I’m partial to the purple ones (which turn green when cooked), because they’re easier to see amidst all the foliage. Pole beans need trellises or other supports, since they’re vines and

grow upward. Bush beans don’t, but they require a lot of bending or squatting when picking, which your knees and back may not enjoy.

Don’t plant beans until there’s no danger of frost and the weather is getting warm for good. The soil needs to be at least 48°. I usually estimate this, but this year, I’m going to buy a soil thermometer. (Shirley’s in Vineyard Haven carries them, or you can get one online for under $20.) Soil that’s too cold and moist delays germination and can cause the seeds to rot in the ground, which I’ve learned from painful experience. You can speed germination by sprouting beans in newsprint as described for sugar snaps above.

LIMA BEANS You might believe you hate lima beans, but that’s just because you’ve never had them fresh out of the garden. Homegrown lima beans are absolutely delicious; think succotash, think briefly boiled and slathered with butter, think sautéed with garlic. Trust me on this.

Like string beans, lima beans come in both climbing and bush varieties. They take sixty to ninety days to mature, with the bush beans coming in before those grown on a trellis. Do not try my damp newspaper method of germinating. I’ve

attempted it twice, and both times, when I checked on the seeds after two days, they were covered in white mold and rotting, without even a trace of germination. Plant your lima beans directly in the ground three weeks after the last frost, once daily temperature has been consistently 65° for a week or so, probably mid to late May.

ONIONS can be planted from seed, but you need to start seeds indoors six weeks before planting them outdoors, so we’re too late for that. A faster, surer method is planting from “starts,” which are essentially very small onions, about the size of your fingertip. My starts always grew a bit and gave me onions, but they were always on the small side, probably because I planted them too late; starts, I’ve learned only recently, like to be planted in cool soil, probably in late March or early April. Again, we’re a bit late; starts will still work, just not as well as they would have if planted earlier.

Two years ago, I ordered onion seedlings online (you receive a big clump of them held together with a rubber band), and now I’ll never grow onions any other way. Last summer, some of my onions grew to the size of softballs. Onion seedlings should be planted when the soil is about 50° — usually early May. There are a number of other preservable vegetables that you can plant from seed before the end of May, including beets, cabbage, carrots, cucumber, and peppers. Early crops of these can be pickled or canned (canning preserves vegetables in brine, without vinegar). In a couple of months, I’ll write about crops planted later in the season, as well as second plantings of some of those already mentioned. Here’s a useful planting calendar for Zone 7 .. Peruse this to get a sense of what you should be planting when, and don’t hesitate to use Google to find out the optimal soil temperature for planting anything specific.

I’ll leave you with a recipe I made in early February, using my own garlic, onions, and butternut squash, along with collard greens that were still growing in my garden right up to the weekend when we had those below 0° temperatures.

GARDEN TO TABLE • ALL YEAR LONG 28 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

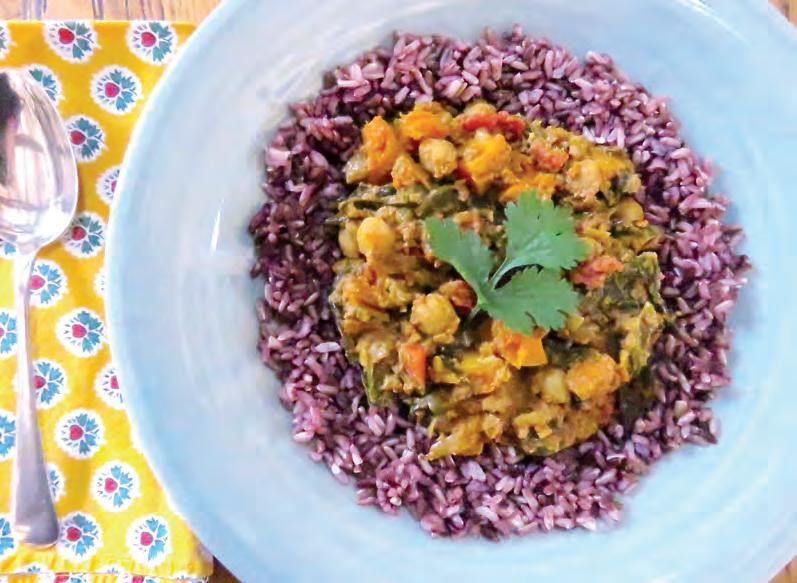

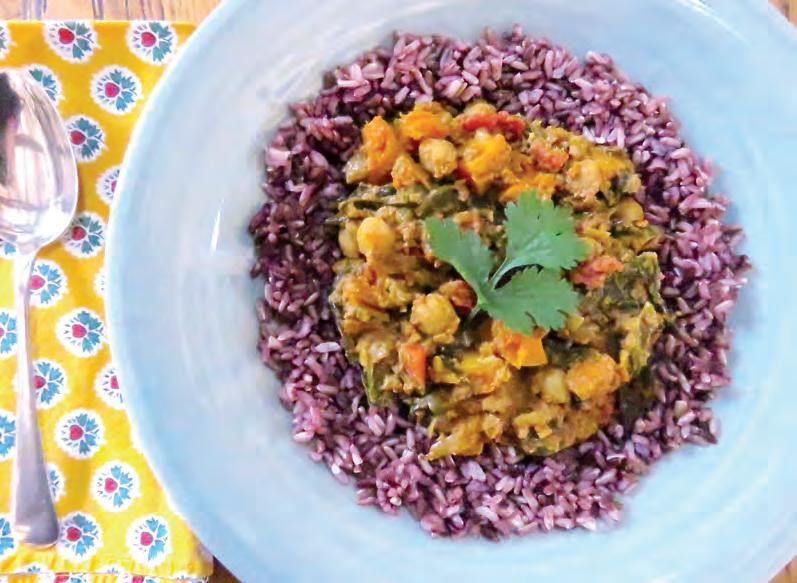

GARBANZO STEW WITH COLLARDS AND WINTER SQUASH

Recipe and Photo by Laura D. Roosevelt

Serves: 3–4

This is a meal-in-one recipe I’ve been making — and modifying — for nearly 25 years. I first had it at a friend’s house on Halloween night, after we took our young children trick-or-treating. I was still new, back then, to cooking with Indian spices, and I thought this dish was the most delicious thing I’d ever eaten. All these years later, I continue to make it several times a year, but I particularly like making it in winter, when I can still use squash, onions, and garlic harvested the previous summer and stored in my cool basement, along with collard greens that remain growing in my garden throughout the winter unless there’s a severe freeze. It’s a meal that can be made in advance and quickly reheated, and the recipe can easily be doubled or tripled to feed a crowd.

INGREDIENTS

1 tbsp. olive oil

2 tbsp ghee or butter

1 tsp. turmeric

1 tbsp. garam masala

1 tsp. ground chili

1/3 cup plain yogurt

2 onions, chopped

2 cloves garlic, minced

2 cups peeled butternut or other winter squash, cut in ½" dice

½ cup chopped cilantro (leaves and stems), plus more cilantro leaves for garnish

1 (2") piece ginger root, peeled and finely chopped or grated

1 (15 oz.) can diced toma toes, or 2–3 medium fresh tomatoes, chopped, juices reserved

1 (15 oz.) can garbanzo beans, drained

1 medium bunch collard greens or kale, stems removed, leaves chopped into bite-sized pieces, or one

5 oz. bag baby spinach

Cooked rice or quinoa for serving

Pinch of salt

DIRECTIONS

1. Preheat oven to 375°. In a medium bowl, mix the diced squash with the olive oil and salt until evenly coated. Spread the squash in a single layer on a baking sheet, and roast in the oven for 15 minutes. Remove from the oven, stir and turn over the pieces, then return to the oven. Roast 15 to 20 minutes more, until the squash is easily pierced with a fork.

2. Meanwhile, in a Dutch oven or a frying pan with high sides and a lid, sauté the onions and garlic in the ghee on medium heat until translucent, about 5 minutes, stirring occasionally. Stir in the turmeric, garam masala, chili powder, and ginger, then add the tomatoes (and reserved juice, if using fresh).

3. Remove half the garbanzos and purée them with yogurt in a food processor or blender until smooth.

Stir them into the tomato-onion mixture, along with the whole beans. Bring the mixture to a boil, then reduce heat to low. If using chopped collard greens, place them on top, cover, and simmer for 5 minutes. Remove the lid, stir the greens (now wilted) into the stew. If the stew seems too thick, add a little water. Replace the lid and simmer for 15 more minutes, stirring occasionally.

4 Remove the pot from the heat and stir in the cilantro, roasted squash, and baby spinach (if using). Taste, and add a little salt if needed.

5 Serve over cooked rice or quinoa. Garnish with the cilantro leaves.

Notes: There is salt in canned garbanzo beans and in canned tomatoes. Therefore, the only additional salt I use in this recipe is a pinch stirred into the squash before roasting.

ALL YEAR LONG • GARDEN TO TABLE 29 marthasvineyard. .com

Net zero homes take advantage of technology such as heat pumps, high efficiency windows, renewable energy generation (solar panels for example ), fresh air systems ... under slab foundation insulation, and more impactful insulation practices overall.

RIGHT AT HOME • FEATURE 30 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

RIGHT AT HOME:

THE BONES of DesignGreen

Healthy for the planet, healthy for the people.

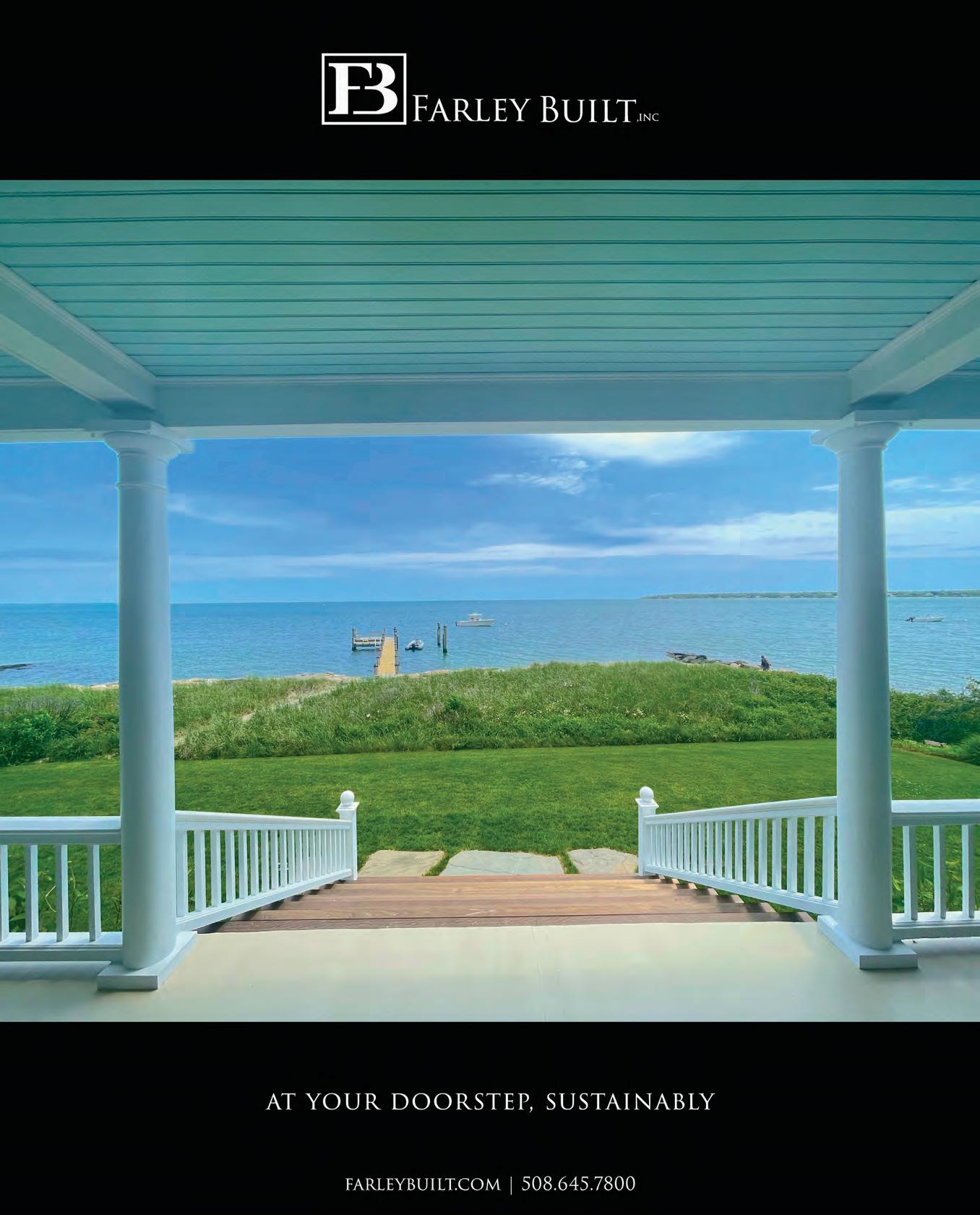

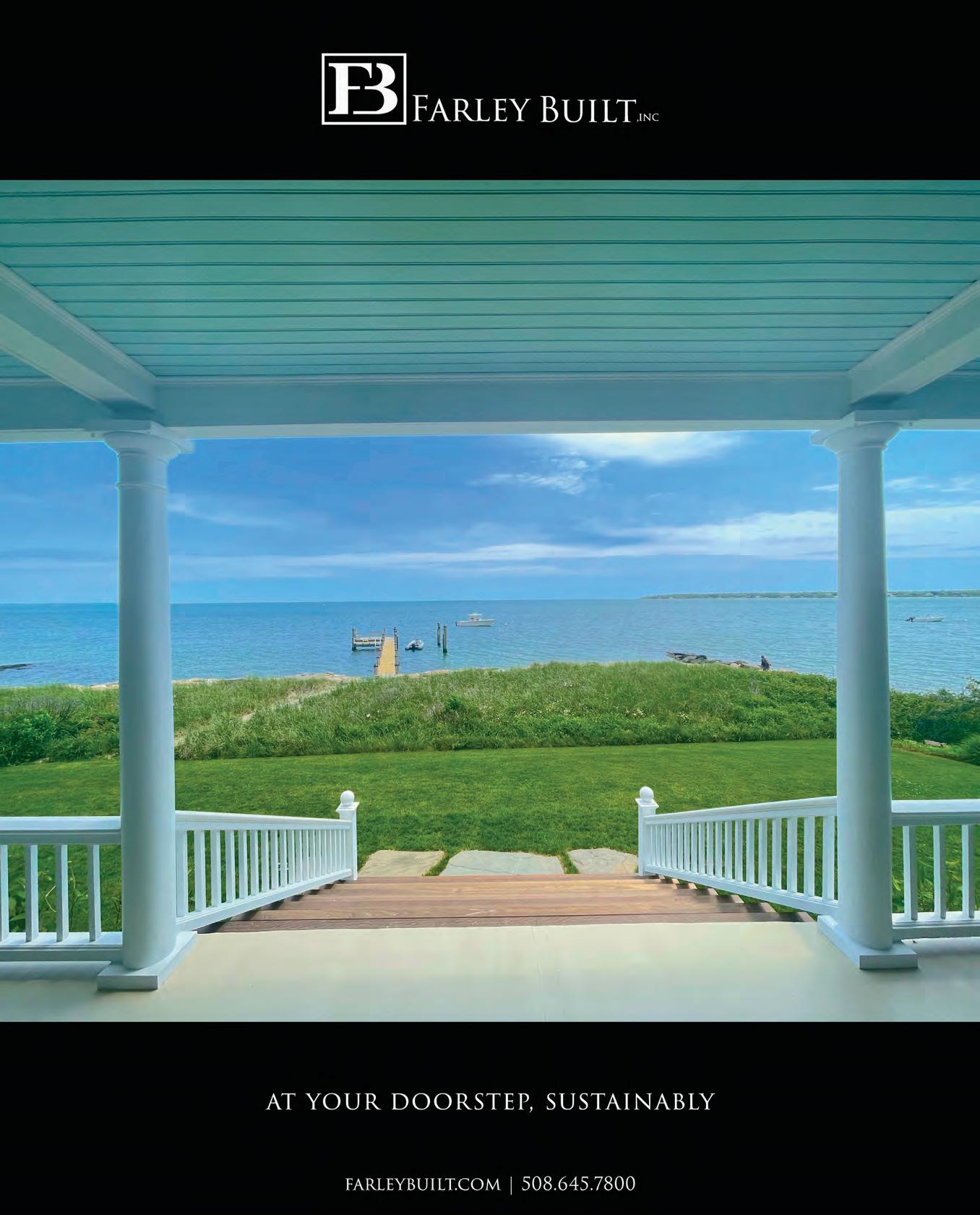

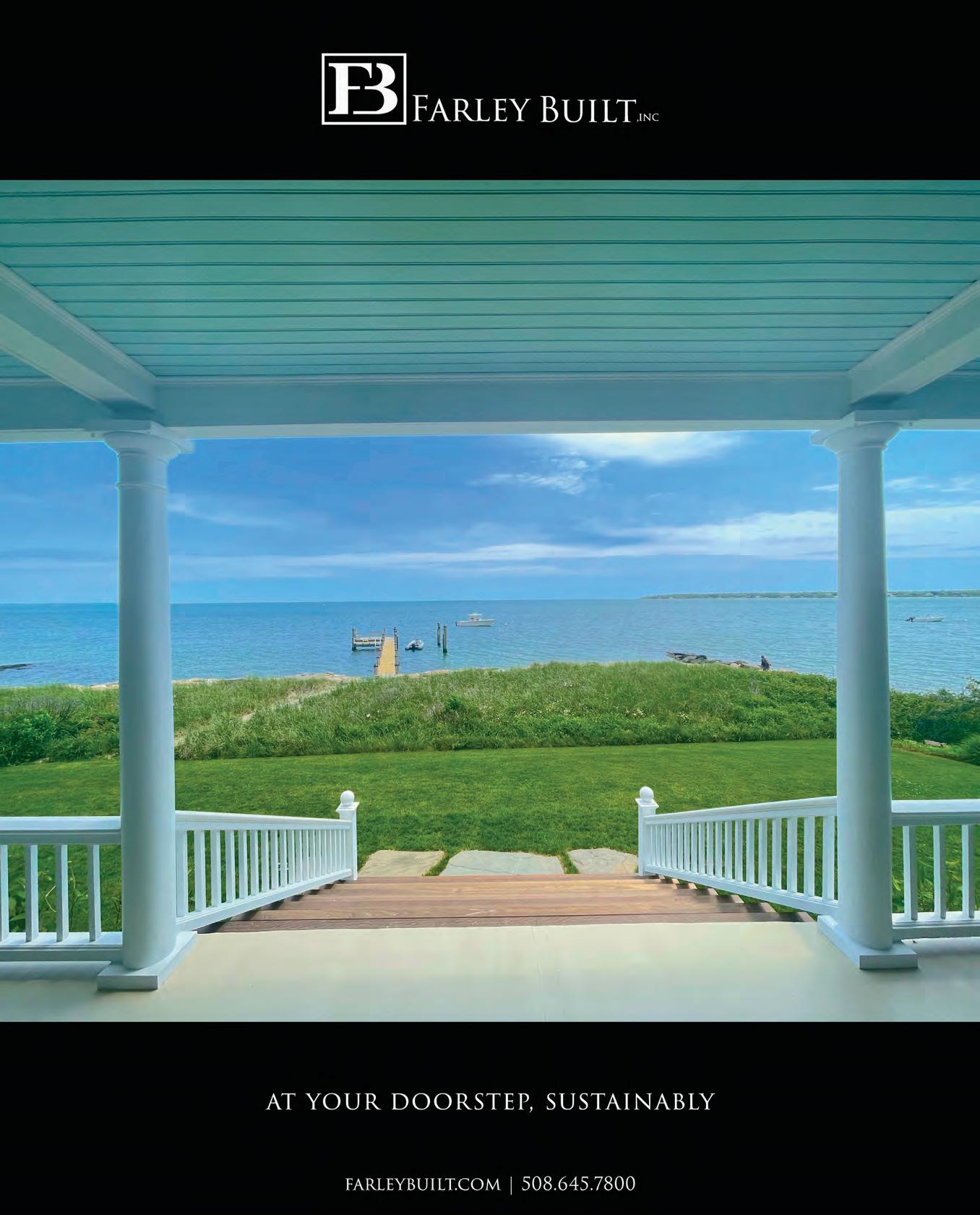

Story by Mollie Doyle Photos by Randi Baird

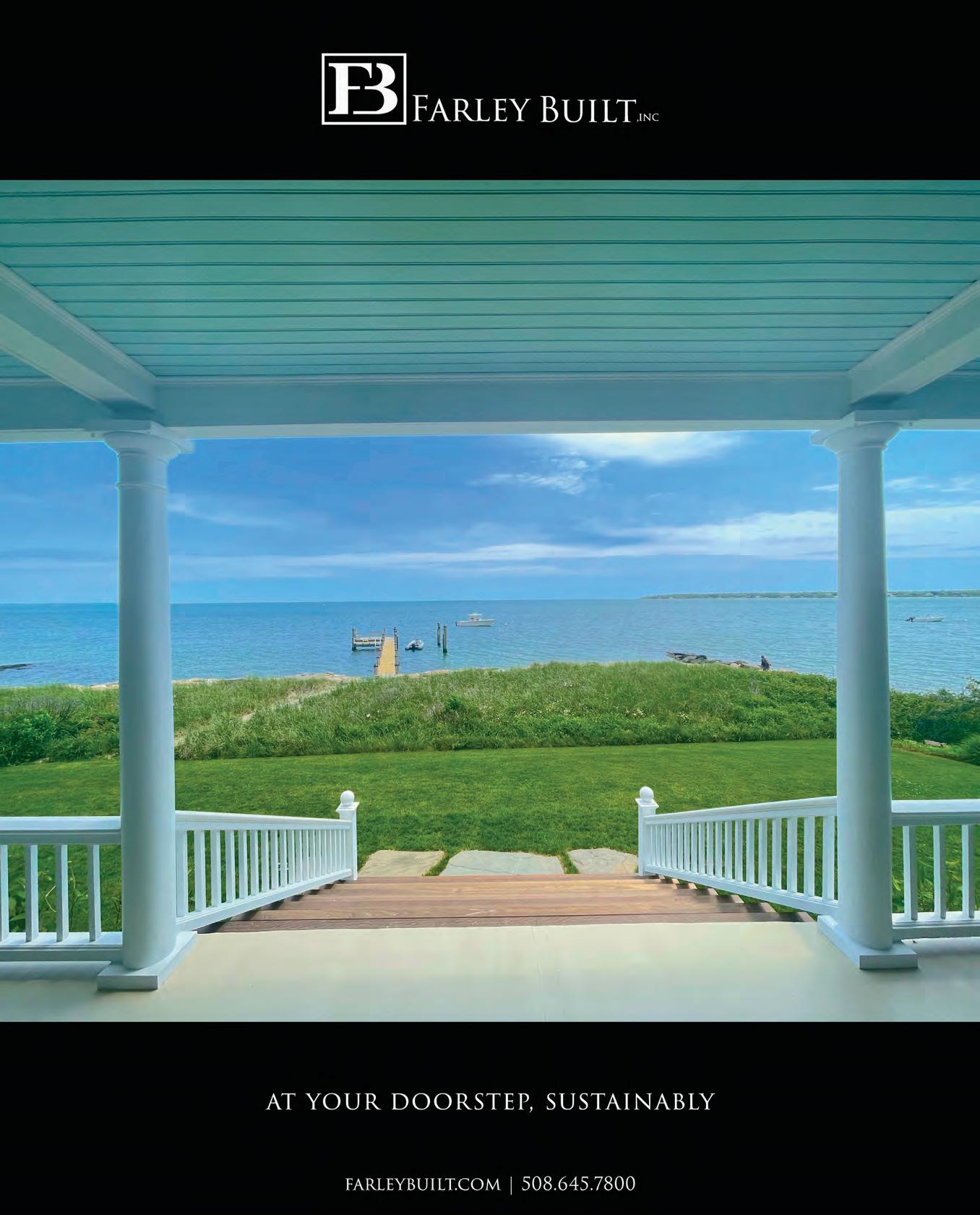

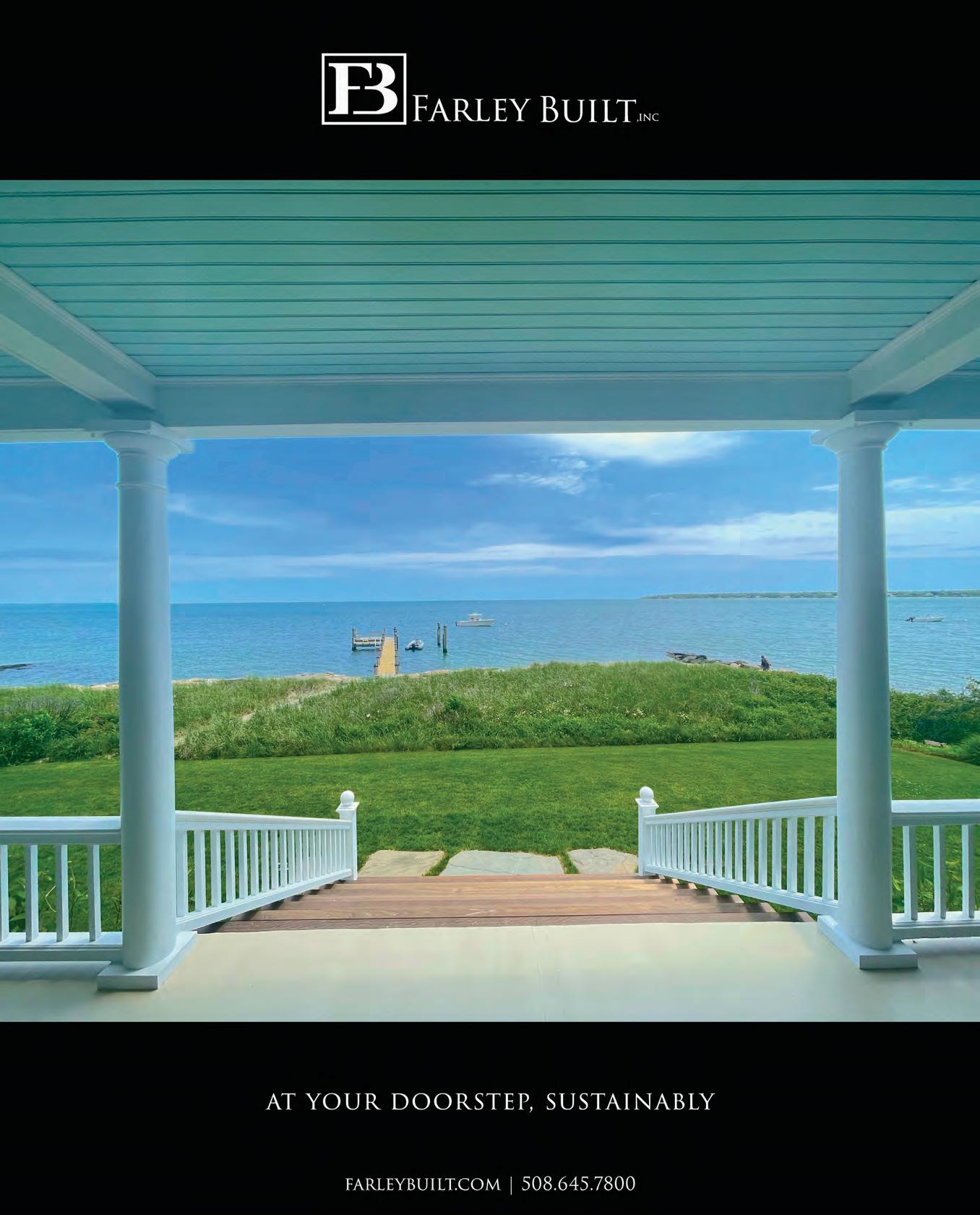

As most of my friends know, I frequently practice “R to R,” a term my daughter Emma and I invented, which means looking at real estate magazines to relax. Our top picks are Architectural Digest, Dwell, ID, Elle Decor, and English Home. But one story I’ve always found missing in these publications is a full-length feature on the high performance green home-in-progress. Sure, Dwell or AD will highlight a net zero energy or LEEDcertified home, but more often than not,

the images and the story are mainly about the furnishings and the client’s desires for how they want to live in the space. While this is a valid focus, I yearn for an in-depth look at a home from a purely green design standpoint. Tell me about the engineering! How does it dictate design? What parts of the building process differ from those used in constructing a home that will use fossil fuels? Are elements of the design and engineering visually married?

I decided that if I wanted these questions answered, I’d have to write the

story myself. And this meant finding a green house while it was in the process of being built.

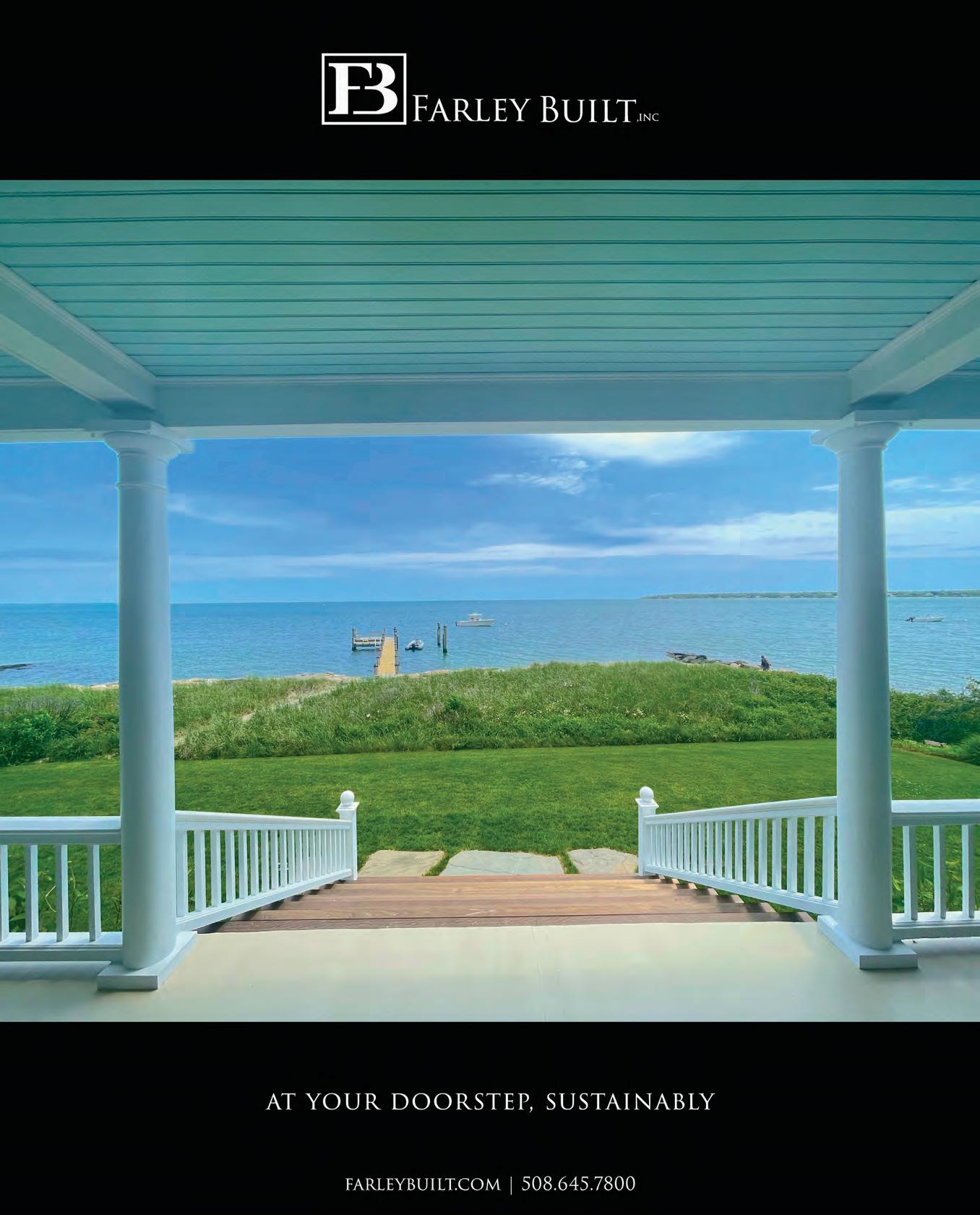

On an early morning winter walk in the woods, I came across a job site with a gorgeous house going up. I did a little trespassing (occupational necessity) and saw the name Farley Built on a machine outside. Farley Pedler’s contracting company is one of this island’s best high performance home builders. And, fortunately, the owners of this Farley Built home-in-progress

FEATURE • RIGHT AT HOME 31 marthasvineyard. .com

The house, shown here in architectural renderings, doesn't scream "high performance house."

ARCHITECTURAL RENDERING ZEROENERGY DESIGN

generously agreed to let BlueDot use it as an example of what green design can be, and how it works. I was delighted to learn that the home was designed by the Boston architectural firm ZeroEnergy Design, which, since its inception, has been dedicated to the practice of green building design — so dedicated to it that ZeroEnergy Design’s principal and coFounder, Stephanie Horowitz, refers to herself as a “stick in the mud.”

Farley and Stephanie are each delighted to be partnering on this project, to be collaborating with someone equally steeped in the technology of the green design world. “It’s really lovely to be working with someone with shared values,” Farley tells me. “I hear builders and clients alike complain about the energy code requirements. My feeling is, we can all be doing better. Our building code is the bare minimum requirement. Why aren’t we doing better? I see so much exquisite craftsmanship in the homes here. Why is this not extended to what we do with a home’s energy use?”

One of ZeroEnergy Design’s missions is “Designing homes and buildings that use 50% less energy than building code requires, in pursuit of energy independence.” Stephanie expands on this: “The reference to building code is a moving target as the code continues to improve. With a significant reduction in energy use, paired with roof-top solar, many of our single family homes produce as much energy as they use in a given year.”

The home I found in the woods will be a net zero building — the amount of energy used by the building on an annual

basis will be equal to the amount of renewable energy created on the site or obtained from a renewable energy source offsite. Net zero homes take advantage of technology such as heat pumps, high efficiency windows, renewable energy generation (solar panels for example ), fresh air systems, Energy Star appliances, WaterSense certified fixtures, efficient LED lighting, low VOC paints, under slab foundation insulation, and more impactful insulation practices overall.

Stephanie and her team worked with the homeowners to define their program of living and articulate their aesthetics — from the basics of how many bedrooms and bathrooms they’d want to what kind

of kitchen they like to cook in and whether or not they want to eat in an open space that relates to a kitchen or have the dining space be its own room. All of this was then folded into everyone’s ultimate goal: net zero energy.

The first thing I appreciated about this house in the woods is that from the outside, it doesn’t scream, “I am a high performance structure.” In fact, when I first came across the home and saw its classic roof lines and green window trim through the trees, I thought it almost looked like a classic old Vineyard home undergoing a gut renovation. I appreciated the way ZeroEnergy Design sited the home between towering oak trees and incorporated some of the Vineyard’s more classic architectural lines to make it feel as though it’s been here for a while, rather than like a spaceship that recently landed. (This said, I do also believe there are places in our landscape for modern lines.)

“The technical aspects of an energy efficient design do not have to dictate the aesthetic,” says Stephanie. “It can be a traditional New England vernacular or ultra modern. With this home, the design is recognizable — aspects of it are familiar and rooted in materials and in details that speak to a more traditional home on the Vineyard. We design with a commitment to making homes air-tight and super insulated so that they use a fraction of energy of a conventional home, and create a healthy and thermally comfortable environment. But it also has to delight the owner. This said, design that respects the planet and limits the amount of energy we use to operate it is, in itself, timeless.”

And when it comes to eliminating excess energy use, ZeroEnergy Design and Farley Built share a central idea: the primary mechanism for heating and cooling the home is the building envelope itself. First and foremost, they make the house air tight so that it can be

RIGHT AT HOME • FEATURE 32 MARTHA’S VINEYARD /SPRING 2023

How does the engineering in a green home dictate design? What parts of the building process differ from those used in constructing a home that will use fossil fuels?

The heating, cooling, and air circulation systems play a supporting role to the building's envelope.

a hyper-efficient body, holding in hot or cold air while circulating fresh air for its inhabitants. If there are drafts or punctures (such as a fireplace) in the structure, then it is less effective at holding heat and cool air. Concurrently, they design and install active systems — heating, cooling, air circulation — to play a supporting role to the building’s envelope.

building background. He started working with a framing company on the Cape during the summers in high school. (See our story from two years ago: bit.ly/farleypedler). "We would frame a house in a week; house, windows, doors, roof shingles, decks and then move on to the foundation next door." After graduating from UMass Amherst, he moved to the Vineyard

when it came to construction. That is when my journey started with more intention to what eventually became Farley Built. It wasn't until I did an affordable housing project with Island Housing Trust that I experienced working with another entity with aligned values. It completely reaffirmed what I had been working towards for so many years. It provided healthy, well-built homes that respected the environment and were affordable. That’s when I thought, ‘It's ok to bring your values to a higher standard with construction. This is what we all need to be doing more of.’”

For the last 18 years, Stephanie and her team have been working on their recipe for the best and healthiest high performance house. “Of course the technology has evolved, but we have grown up with it. This is the only way we have practiced architecture. We know of but have never actually practiced the energy wasting habits of traditional design and detailing.”

Farley comes from a more traditional

and “bounced around a little,” working at the Gannon and Benjamin boatyard, the South Mountain building company, and a small cabinet shop in West Tisbury. “I was trying to figure out what my path was going to be. It took a few years before I realized I had all the makings for becoming a builder.