SIMPLE / SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES

CARLOS MONTOYA in His Element

Why Would ANYONE LITTER?

Dot Will Take Your QUESTIONS NOW

What's So Bad ABOUT NUCLEAR ENERGY?

RIGHT AT HOME with Kate Warner

SIMPLE / SMART / SUSTAINABLE / STORIES

CARLOS MONTOYA in His Element

Why Would ANYONE LITTER?

Dot Will Take Your QUESTIONS NOW

What's So Bad ABOUT NUCLEAR ENERGY?

RIGHT AT HOME with Kate Warner

Stunning Chilmark four-acre waterfront paradise. The spacious main house and guest house enjoy wonderful sunsets and unique privacy nestled between a gentle hill and a 200-acre private estate. The property is in the highly desirable Spring Point community with three quarters of a mile of private beach, endless dirt roads, walking trails, and two tennis courts. Exclusively offered $11,995,000.

“ Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was … on a mote of dust suspended on a sunbeam.”

What’s your favorite locally made food or gift?

Publishers

Peter and Barbara Oberfest (publisher@mvtimes.com)

Editors

Leslie Garrett: By the Sea Salt

Jamie Kageleiry: (editor@bluedotliving.com)

MV Sea Salt in special glass containers.

Contributing Editor

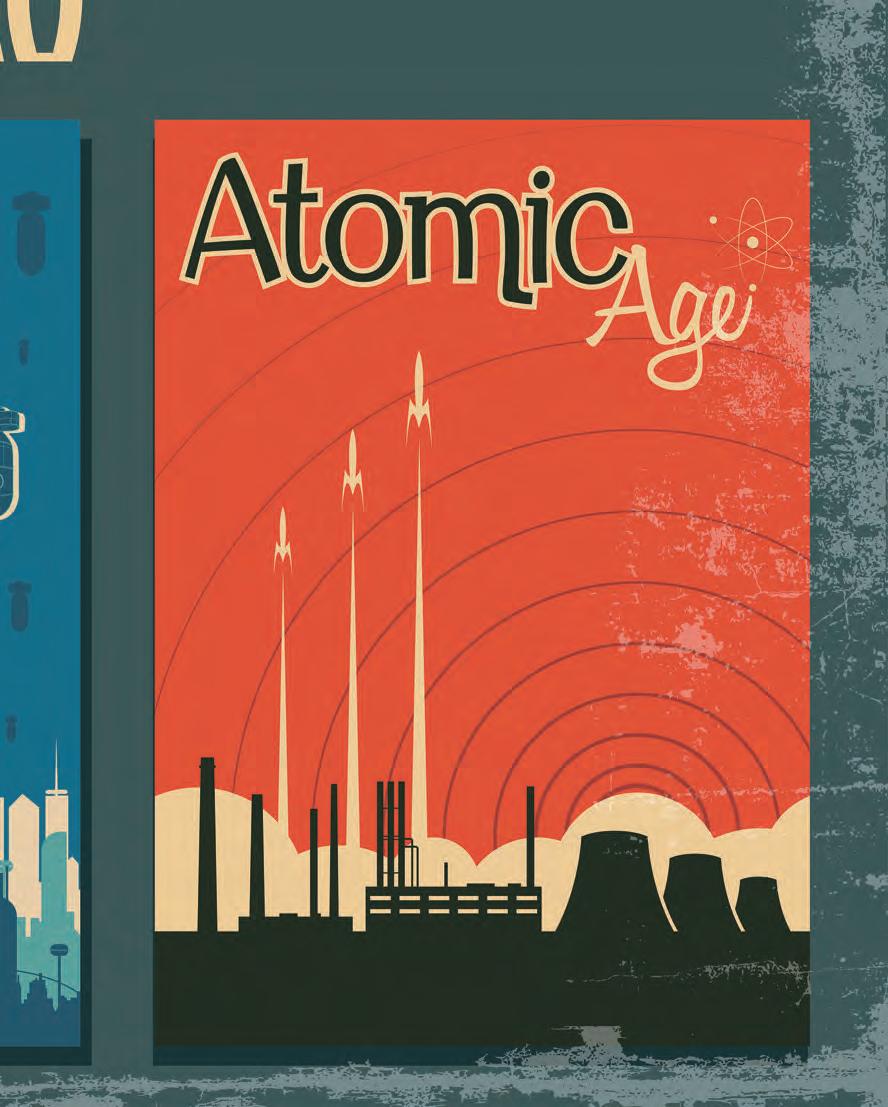

Mollie Doyle

(see contributors’ page)

Creative Director

Tara Kenny

Art Director

Kristófer Rabasca

Design/Production

Dave Plath

Nicole Jackson: Favorite local gift: An online subscription to The Martha's Vineyard Times. Call or stop by the office to purchase a gift card.

Climate Intern

Lily Olsen

(see contributors’ page)

Kelsey Perrett

(see contributors’ page)

Proofreaders Barbara Dudley Davis, Connie Berry

Ad Sales

Jenna Lambert: (adsales@mvtimes.com)

My favorite local, sustainable gift to give for the holidays is a gift card to Jardin Mahoney. They offer supplies and support for growing plants that produce nutrients for us and the wildlife we are surrounded by.

Walter and Nora McGraw

Victoria Riskin: A food basket with bread and cheese from the Grey Barn, and chocolates from Salt Rock Chocolate Co., or an assortment of nuts, honey, coffee, olive oil, or beans from the MVY Coop. Maybe I'll package them in a reusable bowl.

Bluedot and Bluedot Living logos and wordmarks are trademarks of Bluedot, Inc. Copyright © 2021. All rights reserved.

Bluedot Living: At Home on Earth is printed on recycled material, using soy-based ink, in the U.S.

Bluedot Living magazine is published quarterly (three times in 2021) by The Martha’s Vineyard Times, publishers of The Martha’s Vineyard Times weekly newspaper, Martha’s Vineyard Arts & Ideas Magazine, Edible Vineyard Magazine, The Minute daily newsletter, Vineyard Visitor, and the websites MVTimes.com, VineyardVisitor.com, and MVArtsandIdeas.com.

You can see the digital version of this magazine at bluedotliving.com. Bluedot Living is available at newsstands, select retail locations, inns, hotels, and bookstores, free of charge. Find Bluedot Living on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook @bluedotliving.

Subscribe: Please inquire at mvtsubscriptions@mvtimes.com

–Carl Sagan

In early August, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its report, and it told us what so many who work in the climate arena already knew: Climate change isn’t coming; it’s here — and it’s hitting the planet hard and fast.

The IPCC is a U.N. body whose work is the product of 234 scientists (plus 517 additional contributors) from 66 countries. This group reviewed roughly 14,000 scientific papers over three years to come up with their assessment of the state of our planet. It is an extraordinary feat — both the IPCC and its report. As The Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer puts it, “The IPCC ensures, at least in theory, that during international climate negotiations, the science is unimpeachable: Every country has agreed to the same headline findings about climate change.”

The IPCC’s role, however, is to tell us what is, not what to do about it — that's the role of policymakers around the world.

There wasn’t much in the report that could be considered good news. Except, perhaps, this: The window for decarbonizing, and therefore slowing down or stopping the impact of burning fossil fuels, is not yet firmly closed. Or think of it this way. The doctor has told us our cholesterol levels are high, and we’re already feeling the signs of heart disease. But if we follow doctor’s orders, we can still stave off a massive heart attack. We aren’t dead yet.

Which means, of course, that there is hope. Not pie-in-thesky hope, but realistic, roll-up-your-sleeves, be-the-change-youwant-to-see hope. To paraphrase activist and author Rebecca Solnit, there is darkness not just in the tomb but in the womb.

This can be a rebirth, and we can be its midwives.

When we first conceived of Bluedot Living, it was without the specifics of the latest IPCC report, but with an awareness

Geoff Currier

of its basic gist: The time to act is now. The time to connect is now.

It’s why our focus is on solutions. It’s why we want you to see what smart, motivated people are already doing, because it shows what’s possible for us, too. It’s why we want to celebrate what you are already doing. And it’s why we wanted to hone in on communities, specifically this Island community, because though climate change is a global problem, the impacts show up locally, in our ponds and forests, the place we love and call home.

Ultimately, though, the scale of change necessary will have to come from our policymakers. But we play an important role there too. We cannot let up. We must demand our elected leaders at all levels of government respond to this threat with the urgency required. Greta Thunberg tells us she wants leaders to panic. She wants them to act as if our house is on fire because it is.

Grief and anxiety are completely normal responses to the climate crisis. We must tend to our own and others’ mental health. Nature can be healing. So can binge-watching “Ted Lasso.” We must carve time in our lives for rest.

And we must rise again to what this moment requires of us.

We hear the echo of the words of Carl Sagan, who inspired the name of this magazine, that on this pale blue dot is everyone we love, everyone who ever lived. It is our only home.

We can respond to the climate crisis with despair and handwringing, or we can take this as our opportunity to reimagine how we do everything — from how we grow our food to how we shop, to how we heat and cool our homes, to how we move around on this pale blue dot. We have chosen reimagination. Rebirth.

If you are here with us, we are grateful that you have, too.

– Leslie Garrett (and Jamie Kageleiry)(“Cruising with Currier,” and “Katama Airfield.”) is an associate editor at The MVTimes. “If you’re looking for side dish for a holiday party,” he told us, “Romanesco is not only delicious but a conversation starter as well. It tastes like a cross between cauliflower and broccoli and has a mild, rather earthy taste. And visually it looks like broccoli on acid. My wife brought Romanesco home from Ghost Island the other day, cooked it up with garlic and oil, and it was great.”

We asked our contributors, “What’s your favorite made- or grown-on-MV holiday or hostess gift?” Here’s how they answered.

Mollie Doyle (“Room for Change,” “Cast Iron Skillet Irish Soda Bread”) is a writer, mother, and yoga teacher. Her favorite holiday gift is homemade granola, which she usually makes and gives in glass Mason jars. The only unsustainable aspect of this is the amount: In 2020, she made more than 50 quarts, baking in the early mornings, late at night, and between articles and yoga classes. After

that effort, she didn’t make it again until June.

Jeremy Driesen (photographer, “Cruising with Currier,” “Green Economy,” “Kate Warner”) shoots often for the Times’ magazines. His favorite? Lobster bisque from Net Result.

Kate Feiffer (“Why Do People Litter?”) is the author of 11 books for children, an illustrator, and the event producer for Islanders Write. Books are the perfect

Continued on page 57

8 What. On. Earth. Hungry for food stats?

10 Good News from All Over

14 Field Notes: An Update on Food Waste from Melissa Hackney at Vision Fellowship

16 In a Word: Radical hope

22 Nuclear Energy: What’s So Bad About It, Anyway? By Leslie Garrett.

Nuclear energy has a branding problem. (Accidents! Toxic waste!) A new generation of nuclear reactors could be the energy source we need right now

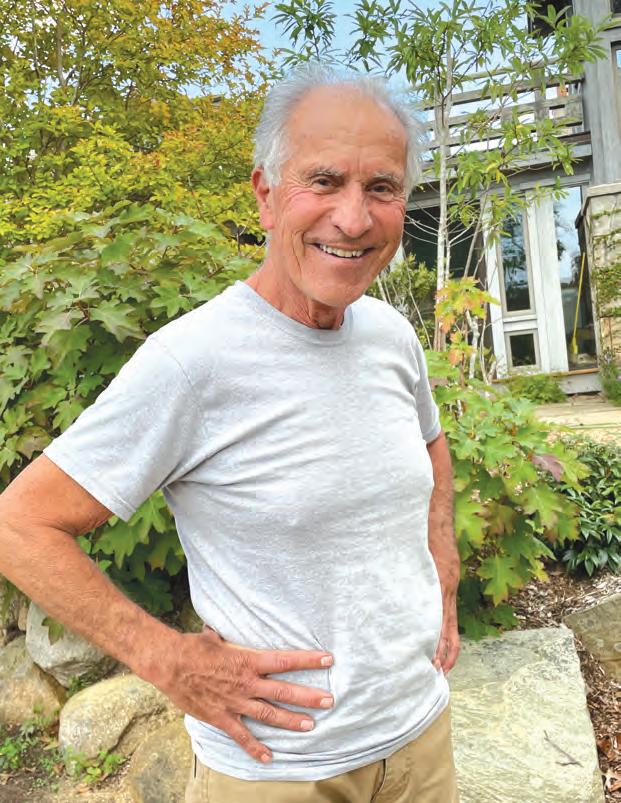

28 Carlos Montoya Relies on Nature’s Bounty By Valerie Sonnenthal

It’s not so much landscaping as managing nature around his home, and not adding much.

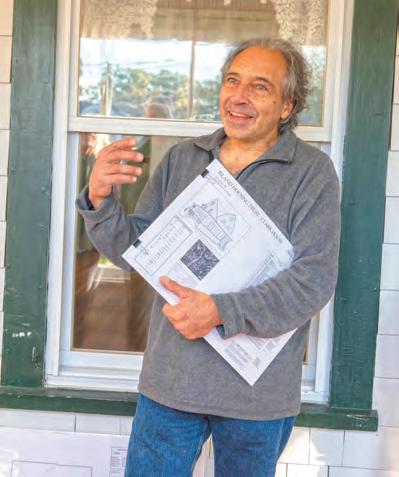

32 How Katama Airfield Escaped the Clutches of Developers By Geoff Currier

To preserve a 128-acre ecological gem, it took a man who loved planes more than money.

40 Buy Less, but Buy Better By Gwyn McAllister

Looking for gifts? Keep it local.

44 A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats

ByLeslie Garrett

There’s a lot of buzz around the phrase ‘green economy,’ but what exactly is it?

47 The Power of Divestment By Lily Olsen

Getting money out of fossil fuels.

50 Kate Warner’s Day in the Sun

By Kelsey PerrettShe was an early advocate for solar energy on Martha’s Vineyard. Now she’s ready to share her vision with the next generation.

38 Tell Me This: Why Would Anyone Litter? By Kate Feiffer

We explore the psychology of those who befoul our beaches and roadways.

4 Editors’ Letter

4 Contributors

17 Dear Dot

Help migrating birds! Humanely evict mice! And more...

19 Cruising with Currier

Behind the wheel of a Kia Niro EV with Greg Milne

48 Good Food

Carb comfort in a cast iron pan

55 Room for Change

Purge the plastic in your pantry (Thanks, Mollie Doyle!)

60 The Keep This Handbook

Useful Composting/Recycling/ Volunteering Info

64 Local Heroes

We Nominate M.V. Commission’s Liz Durkee Cover photo By Valerie Sonnenthal

Photo this page By David Welch

align

OF FOOD PROCESSED ANNUALLY BY THE COMPOSTER AT ISLAND

360 T O N S $

INITIATIVE'S

NINETY FIVE percent of Americans eat turkey at Thanksgiving 3

1

Cost to Vineyard towns to transport and dispose of wasted food in 2020:

720,000 2

Approximate number of Vineyard turkeys: 1,0004

40 cents of every dollar spent on food in 1975 that went back to the farm it came from ¢ 40 14.6

U.S. households that were food-insecure in 2020

10.5% 8

6,500 TONS 10

OF FOOD ARE SHIPPED OFF-ISLAND AS GARBAGE EACH YEAR

Number of Americans at Thanksgiving who will eat the classic six-ingredient green bean casserole created 60 years ago by Dorcas Reilly in Campbell’s test kitchen: 20 million 5 7 increase

14.6 cents of every dollar spent on food in 2018 that goes back to the farm it came from

IN VEGANISM OVER 15 YEARS

APPROXIMATELY

300 percent 9 % 40

OF FOOD EACH YEAR IN THE US THAT GOES UNEATEN 11

“What we’re eating is never anything more or less than the body of the world.”

– Michael Pollan, The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four MealsSOURCES: 1-2 ISLAND GROWN INITIATIVE, igimv.org/foodwaste; 3. REPUBLIC WORLD, bit.ly/turkeynumber; 4. VINEYARD GAZETTE, vineyardgazette.com/news/2018/11/21/turkeys; 5. SMITHSONIAN, bit.ly/casseroleinventor; 6-7 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR SUSTAINABLE SYSTEMS, bit.ly/foodsystemfacts; 8. USDA ECONOMIC RESEARCH SERVICE, bit.ly/foodsecuritystatisics; 9. VEGAN NEWS, bit.ly/newvegans; 10. ISLAND GROWN INITIATIVE, igimv.org/foodwaste. 11: NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL, bit.ly/40percentwaste. GROWN FARM

DELIVERING CLEAN ENERGY BY 2023

Vineyard Wind 1 will reduce carbon pollution by over 1.6 million tons per year, an equivalent of removing 325,000 vehicles from roadways. e project will generate clean, renewable, affordable energy for over 400,000 homes and businesses across the Commonwealth.

Vineyard Wind is committed to ensuring the protection of marine habitats and minimizing any impacts to the fishing industry.

As climate change–induced wildfires worsen across the world, some locations in the U.S. have found a solution: Goats. Lani Malmberg, a goatherder from Colorado, travels the American West,

allowing her herds to graze as a fire prevention method. She is hired by local governments and private landowners. Goats can eat vegetation that other grazers can’t reach — goats can stand up to nine feet tall on their hind legs. Their waste also increases the organic matter in

soil, which means it can hold more water. In addition to reducing brush, the herds can restore land that has been burned by a previous wildfire. And adding to their usefulness, goats are able to graze on steep slopes, areas that other fire prevention methods have trouble reaching.

“And, when you want something, all the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it.”

— Paulo Coelho, The Alchemist

Goats are one of many tools that state and local agencies are employing to prevent or control wildfires, including prescribed burns and herbicide.

The past summer brought deadly heat waves to cities all over the continent, including the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia. But research shows that there’s a powerful, towering weapon in the fight against urban heat: tree canopy. Communities with more tree cover remain cooler than those without.

But in yet another instance where we see inequity exacerbated by climate change, a study of more than 3,000 communities across the U.S. indicates those with a higher number of nonwhite residents have fewer trees and less green infrastructure.

A new project aims to cool things off, at least in Los Angeles. The USC Urban Trees Initiative “combines advanced mapping technology, air quality research, and landscape architecture to show the best places to plant new trees.” It’s been put to use in two neighborhoods that lack shade, with plans to follow suit with others.

They’re called “forever chemicals” because they accumulate in humans and animals, and don’t naturally break down. Maine has banned the use of all products with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) by 2030, becoming the first state to implement such strict regulations. PFAS cause a range of issues, including birth defects, infertility, cancer, and thyroid disease. And they show up in the blood of 97 percent of Americans, according to studies.

We find these chemicals everywhere from cookware to cosmetics to clothing. By 2023, manufacturers in Maine will be required to report their presence.

While other states ban PFAS in certain products, such as carpeting, Maine is leading the way on a total ban. Let’s hope others aren’t too far behind.

There’s a lot of buzz around a new initiative taking off at Pittsburgh International Airport. When faced with a problem of

honeybee swarms forcing planes to land, the airport decided to coexist with its fellow flyers, rather than eradicate them. Honeybee populations have faced stark declines in recent years. Honeybees are essential to our food supply, responsible for one in three bites of Americans’ food. Many airports, including Pittsburgh, are surrounded by natural habitat suitable for honeybees — woods, overgrown fields, and streams. What’s more, beekeeping has solved the airport’s swarm problems. Swarm traps around the airport perimeter offer a more suitable landing spot. Honeybees also act as “bio-detectives” — their honey indicates to scientists whether the airport’s levels of toxins exceed regulated air pollution levels.

A number of other airports have started similar operations.

While you might have noticed a shift to paper straws in your favorite coffee shop, or reusable bags at the grocery store, single-use plastic is still all around us. New

Zealand aims to change that. The country is paving the way in the global fight against waste with its recent promise to ban most single-use plastics by 2025.

Among the banned plastics are bags, cotton buds, cutlery, straws, and fruit labels. These items will be phased out beginning in 2022.

Despite its reputation as environmentally conscious, New Zealand is currently one of the top 10 per-capita producers of landfill waste. This ban, according to environment minister David Parker, would “ensure we live up to our clean, green reputation.”

The government has also announced funding for businesses to research alternatives to single-use plastic, showing the world that a plastic-free future is within reach.

The steel industry currently emits more than 3 billion tons of carbon dioxide annually in steel production. A new Swedish project, hydrogen breakthrough ironmaking technology (HYBRIT), is employing

an alternative way of steel production that uses hydrogen instead of carbon to remove oxygen from ore. The byproduct is water, instead of carbon dioxide.

There is currently just a pilot plant, but there are plans to build a commercial-scale demo plant that will produce 1.3 million tons of steel a year by 2026. While “green” steel might cost 20 to 30 percent more than traditional steel at first, the cost will come down as the electrolysis process and green energy sources become more efficient. Government subsidies, tariffs, and taxes could also help bring down the price.

Electric vehicles are a godsend in the urgent transition away from fossil fuel. The current problem, however, is that the infrastructure required for an all-electric fleet is lacking—there aren’t enough charging stations. Michigan has a solution.

In a groundbreaking move, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer announced that the state will

construct a wireless, dynamic charging roadway in the U.S. "Michigan was home to the first mile of paved road, and now we're paving the way for the roads of tomorrow with innovative infrastructure that will support the economy and the environment, helping us achieve our goal of carbon neutrality by 2050," said Governor Whitmer.

While you might hear most often about reducing carbon dioxide output to fight climate change, scientists are also stressing the need to extract greenhouse gas from the atmosphere — and a carbon-capturing plant in Iceland is on the cutting edge. The plant, called Orca, was built by Climeworks, and is currently the world’s largest.

The process involves large fans sucking carbon dioxide out of the air and collecting it in filters. After the filters are blasted with heat, freeing the gas, the carbon dioxide is mixed with water and pumped into underground basalt caverns.

Nearly a billion metric tons of carbon dioxide need to be extracted per year by 2050 to reach carbon-neutral goals. While Orca can only capture 4,000 metric tons annually, Climeworks says this capacity will grow rapidly. This plant will serve as a blueprint for more of its kind around the world.

A tiny fish, famous for halting construction of a federal dam in the 1970s, has made its way off the endangered species list. The snail darter, only 3.5 inches long, is native to Tennessee.

Scientists have developed a mapping system that can help track and protect coral reefs. The Allen Coral Atlas creates high-resolution maps of the world’s coral reefs through combining local data with nearly 2 million satellite images. The maps will inform researchers and

government officials about where action is needed to protect reefs.

While only 1 percent of the ocean floor is covered by coral reefs, over a quarter of marine wildlife relies on these habitats. Increasing water temperature and acidity, caused by climate change, have destroyed about 27 percent of reefs. The map could also help scientists discover which coral species are more resistant to increasing temperatures, and could be used to restore damaged reefs.

Several once-endangered tuna species are now in the clear. Two bluefin, a yellowfin, and an albacore were either removed from the endangered species list or categorized as no longer critically endangered in September. This comes after a decade-long effort to mitigate overfishing, and speaks to the success of sustainable fisheries. In 2011, the International Union for Conservation of Nature announced that these four tuna species, among other commercially fished

tuna, were endangered. Since then, reduced quotas and improved data have allowed better tracking and management in order to protect the creatures against overfishing. These impressive species — which can grow up to six feet long and 550 pounds, and reach speeds of up to 40 mph — will remain in our oceans.

The last leaded-gasoline refinery, located in Algeria, shut down in August. Leaded gasoline has caused high levels of lead in human blood, as it pollutes the air, water supplies, crops, and soil. Vulnerable people, particularly children, are most susceptible to lead exposure’s harmful consequences.

The shutdown of Algiers Refinery comes after the U.N. Environment Programme spent decades pursuing a global ban on leaded gasoline. Scientists estimate that ending production of this toxic fuel will prevent nearly a million deaths from heart disease, stroke, and cancer each year.

Martha’s Vineyard’s primary export is not fish, or locally grown food, or Island-made crafts. It’s trash. An estimated 19,000 tons of garbage are shipped off-Island each year. Of that, 6,500 tons is food waste. Over the years, various concerned Islanders have explored ways to collect and repurpose food waste locally into valuable and environmentally friendly compost. They realized that doing this on-Island would keep decaying vegetable matter and the methane gas it produces out of landfills. It would also reduce transportation and disposal costs, and the number of trucks and boats using fossil fuels.

By 2009, the Martha’s Vineyard Commission’s Island Plan, in the works since 2006, had identified a centralized composting unit as a key strategy to transform the Island’s organic waste (any biodegradable waste that comes from a plant or an animal) into useful resources. Selecting a solution can be easier than implementing it, though, especially when the desired outcome requires action by every Islander and every Island town. People must separate their food waste at home, and compost it or regularly take it to a collection site. A site (or sites) for an in-vessel composting unit (or units) must be acquired by purchase or longterm lease. An organization, public, private, or a combination, must step up to run the entire collection, composting, and curing process. Funding — again, public, private, or a combination — must be secured. Each town must approve an agreement for the facility’s use and, potentially, all or a portion of its capital costs.

People are inspired to act when a need is urgent and personal. Massachusetts’ 2014 ban on commercial food waste in the trash stream made the problem personal for at least 18 of the Island’s restaurants and the people who work in them. Any entity that produced one ton (reduced to a half-ton in 2021) of food waste during any week of the year is required to

separate food waste and send it to a proper composting facility. And yet, seven years after the food separation law took effect, the infrastructure does not exist to collect and compost at scale.

Beginning in 2013, in anticipation of the law’s enactment, the Martha’s Vineyard Vision Fellowship, through research and interviews, identified pockets of Islanders who recognized and were discussing the problem. The board of the Martha’s Vineyard Refuse Disposal and Resource Recovery District (MVRD) had been meeting with Jim Athearn, Tomar Waldman, Jessie Holtham, Alan Ganapol, Brendan O’Neil, and others for more than a year regarding food waste composting. The town transfer stations, the town boards of health, the MVRD, the hospital, the commercial trash and recycling businesses, restaurants, and the schools were also interested. But nothing concrete was underway.

Fast-forward to today. The MVRD is well-positioned to acquire an in-vessel composting facility (together with food waste pickup and compost curing operations) for use by all six Island towns. The optimum Island-wide organic waste composting solution is in sight, potentially fully operational by 2025.

The project has come this far only because of the combined, years-long efforts of public officials, private citizens, and concerned philanthropists. By 2015, the Vision Fellowship had convened and funded an Organics Committee comprised of local leaders to study the very Vineyard challenge of finding a six-town food waste solution. The Vision Fellowship provided funds so that the committee could hire a project manager, Sophie Abrams, and consultants to help conduct the study. As part of the project, the committee initiated a food waste pickup pilot in 2016 that showed such early promise that Island Grown Initiative (IGI) took it over in 2017. IGI grew the pilot into what is now Island Food Rescue, a distinct program within IGI that works to reduce, repurpose, and recycle food waste.

The pilot’s early success also was a call to local action for the Betsy and Jesse Fink Family Foundation (the Fink Foundation). In 2019, the Fink Foundation donated an in-vessel composting unit and food waste pickup truck to IGI. This enabled Island Food Rescue to expand its capacity to prove that local, at-scale food waste

composting is economically and environmentally beneficial. At the same time, the organization launched an Island-Wide Food Waste Initiative to reduce food waste on Martha’s Vineyard by 50 percent by 2030 (ReFed, a national nonprofit working to end food loss and waste across the food system, created by the Fink Foundation, has also set that goal for the entire country). A component of this effort has been to join the push for an Island composting facility. The initiative’s manager from 2019–21, Eunice Youmans, devoted the majority of her time to developing IGI’s Island Food Rescue program and to supporting the Organics Committee’s efforts toward an Island-wide composting solution.

This year, the Vision Fellowship has awarded a grant, its fourth, to the Organics Committee so that it can continue its efforts for the next two years. Woody Filley has joined as project manager, and James Robinson, a 2017 undergraduate Vision Fellow who is earning his master’s degree in public education from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, is the project intern. Woody and James are working with the Organics Committee and leading the extensive, coordinated public policy activities, including significant engagement with local public officials, and presentations to town officials and at town meetings through 2023, that are necessary to facilitate the creation of an Island composting operation capable of processing all of the Island’s food waste by 2025. For this to become a reality, we must all act now to address the problem with a comprehensive, well-planned Island-wide solution.

• L et your town leaders know that you want your town to participate in an Island-based, in-vessel composting facility.

• Collect kitchen scraps in a small countertop container. To collect multiple full crocks before making a transfer station trip, buy a five-gallon plastic bucket with an airtight lid.

• For easy cleanup, line the bucket bottom with a paper towel. Then the food scraps easily dump out.

• Compost at home, or take your full compost buckets to any Island transfer station, or IGI’s Thimble Farm, where drop-off is free through 2021.

In the summer of 2005, I sat across a table in a restaurant with my friend. We had just heard that Canada, where we both lived, had legalized gay marriage. My friend had marched, petitioned, lobbied for many years, though he insisted he never planned to marry. “We worked so long for this,” he said. “And then …” He shook his head. “It’s like it happened overnight.”

I think of that exchange often when I join those working so hard to address the climate crisis. We march, we petition, we lobby. And then … one day, we hear that Harvard has agreed to divest from fossil fuels. That a species is off the endangered list. That renewables are powering entire countries. And though they might seem like small victories, they point to the possible.

They point toward a future that we can’t yet see, can scarcely imagine.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear calls this “radical hope.” Radical hope requires that we summon the ability to imagine solutions, despite what’s happening around us. Radical hope is not to be confused with more passive optimism. As Lear puts it, “Radical hope anticipates a good,” although we may not yet be able to conceive of how that hope will take shape. Radical hope is not the stuff of pithy phrases or bromides, rather it asks us to exhibit courage and

flexibility and a creativity to respond to challenges. To see radical hope in action, look no further than Greta Thunberg, the Sunrise Movement, Indigenous water protectors, and so many others who refuse to give in.

Radical hope is not about ignoring the grief and fear I and, perhaps, you feel as we absorb the magnitude of the climate crisis. But I take courage in the work being done by these activists, young and old — those who, in Lear’s words, “facilitate a creative and appropriate response to the world’s challenges.”

Feeling both the fear and the promise is what radical hope is. It reminds us that our world continues to hold surprises. Victories that are small until, suddenly, they are big.

[ rad-i-kuhl hohp ]

equivalent to taking 325,000 cars off the road annually — Doba pointed out that wind power remains just a part of our clean energy future. “Each wind farm is a big leap forward but incremental at the same time,” he said. In other words, it’s not a replacement for solar panels so much as a companion for them. As for cost, “bills are complicated,” says Doba. While it remains unclear if energy costs will go down, he says, it’s safe to say that your bill will not increase because of Vineyard Wind.

How can we keep our cars rodent-free? And can I give migrating birds a hand?

Dot answers your thorniest questions from a perch on her porch.

Dear Dot,

I was considering getting solar panels on my roof but with the approval of Vineyard Wind, should I bother? And how will Vineyard Wind affect my power bill?

– Charlotte Duncan, Edgartown

Seems a number of us are confused about how, exactly, Vineyard Wind affects our power supply and our pocketbooks so I took your question to Andrew Doba, a spokesperson for Vineyard Wind. While touting the benefits — the 800-megawatt project will power 400,000 homes and businesses and reduce carbon emissions

About 15 years ago my house sitter threw away all the mouse poison I had left around our barn and the outside of our home. She rightly pointed out that I was potentially killing the wildlife and she feared that our cat might get poisoned too. She needn’t have worried about Jessie the cat since she isn’t a hunter. But it isn’t unusual for us to come home after a trip to a mouse nest in our car or engine. A mouse once popped out of our hood onto the ferry! I assumed they were attracted to our car by the Cheerios our then-toddlers dropped. But now we have teens and a new Cheerio-free electric vehicle and still we came home to a mouse nest in the glove box! What should I do?

– Rona, West Tisbury

hoses and upholstery, are often made of organic materials such as soy, peanut oil, and rice husks, making them a veritable buffet for hungry critters. He recommends adopting more than one solution to thwart tiny intruders. “You can wrap your engine in screening or mesh,” he says, though he admits “that’s a pain.” A bit easier is to stuff any openings in the engine with steel wool. Hanjian recommends snap traps placed on top of your tires, though what if we prefer an, ummm, less violent solution? I ask, side-eyeing Bobcat, who has dispensed with the mouse entirely and is performing his feline ablutions.

Rodenticide, suggests Hanjian. I blanche.

The kinder, gentler Jenna Lambert, the director of marketing and ad sales at The MV Times, had a mouse in her Toyota hybrid Rav4 last year and, on the advice of the dealership, sprayed a homemade blend of peppermint oil and coconut oil, she says. Voila. Adios Mickey. Colleague (and Bluedot contributor) Kelsey Perrett sprayed peppermint on dryer sheets and stuffed them in the glove box, seat pockets, and side doors. Which also eliminated worry about the oil potentially staining or discoloring her car interior.

Dear Rona,

Mice are wily. An adolescent mouse can squeeze into a space roughly the size of a dime. Give them a hint of cold weather and they’re on the hunt for some winter digs that will keep them cozy. And seldom-used cars — so many nooks and crannies! So easy to access! — act like a well-lit vacancy sign. (As appealing, apparently, is my fireplace where, as I tap away at my keyboard writing this, my cat captures a tiny mouse in his jaws. I had wondered about Bobcat’s recent fascination with the fireplace. Now I get it.)

But while utterly adorable — those little ears! those teensy whiskers — mice can be very destructive. Tim Hanjian owner/operator of Eco Island Pest Control in Oak Bluffs gets lots of calls about rascally rodents. Car parts, including wires,

While Hanjian hasn’t personally had much success with peppermint, he’s all for sticking with what works.

Rumor has it that spraying Pine Sol on your wires acts as an effective deterrent too though I didn’t find anyone who’d tried it. (Note to self: Put PineSol soaked dryer sheets in fireplace.)

There are a few other things you can do to make your car a no-go zone for rodents:

• Remove leaf debris near your car, which can create something of a bridge to a more permanent four-wheeled residence. But don’t use a leaf blower.

• Store your car with the hood lifted, thereby making it less cozy, warm and attractive.

• Start your car a couple of times a week or, if you’re off-Island for long periods of time, enlist someone to do it for you.

• Clean out any debris, especially food.

And, if all else fails, Bobcat is by the phone awaiting your call.

Birds will be migrating south any day now. Is there anything I can do to help make their trip better?

– Elle G., Vineyard Haven

– Elle G., Vineyard Haven

Though the Vineyard tends to miss a lot of the spring migrators, fall is a wonderful time to give warblers, sparrows, flycatchers, virios, and others an assist as young ones tend to follow the coast south, says the birdly named Matt Pelikan, an Oak Bluffs-based naturalist whom many of you know as the “Wild Side” columnist for The MV Times. And these guys can use our help! “The nature of migration is really intensive,” says Pelikan. “When birds are migrating, they’re running marathons.”

Metaphorically, of course. Their little legs couldn’t possibly run 26 miles let alone the up to 600 miles the American Bird Conservancy says migrating birds travel daily at approximately the same

speed as a car on the highway.

But, like any marathoner, they need water. Lots of it, says Pelikan, who urges us to put out a dish of water on the railing of our deck if we don’t have a bird bath. And if we do have a bird bath, we must ensure that it’s kept clean, with fresh water.

But they also need fuel, says Pelikan, because migrating is so energyintensive. “A lot of the migrants that come through here are much more insect eaters than seed eaters,” he says. That’s important during migration because insects are higher in fat, which these birds need. There isn’t much we can do to ensure a steady supply of insects though we could put out a tray of mealworms, he says, which you can get at SBS in Vineyard Haven. A longer term solution, says Pelikan, is to create a bird-friendly yard that supports insect populations. What that means, he says, is getting away from a closely mowed lawn, having as many native plants as possible (Pelikan recommends blueberry, goldenrods, native asters, even sunflowers and coreopsis. Birds

love beach plums and will take a big chunk out of each before moving on to the next, he laughs.) Let your plants grow tall then let them go to seed. For those neatniks among us, perhaps even just a section of your yard could be left a bit more wild looking. If you act fast, you can get native Vineyard plants via Polly Arboretum’s online sale before October 31, 2021. You can also get in touch with Pelikan’s employer Biodiversity Works, which will help you create a bird-friendly yard. (info@ biodiversityworks.com)

For birds who overwinter, your birdhouse can provide a warm place to cozy up but ensure that you’ve cleaned it out so that the new tenants aren’t exposed to parasites.

For this issue's Cruising with Currier, I took to the dirt roads of West Tisbury with Greg Milne, a project architect and co-owner of South Mountain Co. But a few days before our ride, Greg wrote and said that his coonhound, Nessie, had just gotten skunked, and there was a little l’eau de skunk lingering in the car. Greg said he’d work on the odor, and we agreed to meet and go for a ride anyway.

As I pulled into the driveway at South Mountain in West Tisbury, Greg’s 2019 Kia Niro was hooked up to one of four charging stations. He came over to greet me, joined by Nessie,

who was mercifully skunk-free.

“The reason I got an EV,” Greg said as we headed to the car, “was that South Mountain gave us all fuel cards to pick up the cost of fuel, since we all do a lot of driving. Then they gave us the choice of either having a fuel card, or getting a certain amount that would go toward the down payment of an electric vehicle.”

Greg thought that was a great idea, and he got a 2016 Kia Soul, the forerunner of the 2019 Niro that he now drives. As soon as South Mountain rolled out the incentive, several people coincidentally got the same car. “When we were all charging at the same time,” Greg said, “it was like Kia Souls on parade.”

One problem with Greg Milne’s first Soul was that it didn’t

have great range. In the winter, since it takes more to keep the engine warm in cold weather, he got only 85 miles per charge. To put things in perspective, from Woods Hole to Boston is about 75 miles, but even in the summer he only got around 135 miles per charge. So he traded his 2016 Soul for the 2019 Niro model, which he began leasing last September. The new car gets somewhere around 350 miles per charge, one of the best ranges available in an EV today. In fact, he had just returned from a trip up to Mount Desert Island in Maine, and only had to stop to recharge once on the way up.

Greg explained that he has three ways to charge the batteries. He generally uses his level 1 outlet to top off a charge. South Mountain has four level 2 chargers, which are

more powerful and run off solar panels around the back of the building, making it not only convenient, but there’s no charge. That’s where Greg does the bulk of his charging. A level 2 charger can come to a full charge in six or seven hours. Cronig’s also has four level 2 chargers available for free to the public. Sometimes Greg charges when he goes shopping. Level 3 chargers are located at high-powered stations you find on the road; an app can guide you to locations. A level 3 charge generally takes between an hour to an hour and a half, and they’re often found around malls or grocery stores. “I plan my trips off-Island around charging the batteries,” Greg said. “I like to charge around mealtime, and take a natural break where I can get out, walk Nessie and stretch my legs, and get some

Greg said that driving electric cars can be a good influence on kids. He has a 10- and a 13-year-old, and said that having an electric car has heightened the kids' awareness of the environment. “They’ll spot other electric cars,” he said, “and say, ‘Looks like that person is doing good things for the environment too."

food. Charging at these level 3 chargers usually costs around 30 cents a minute, so if it takes 100 minutes, it costs around $30, still cheaper than filling up with gas.”

We set out from the South Mountain parking lot to explore the dirt roads that stretch for miles around the offices, Greg and I in the front seat, Nessie in the back.

Greg grew up in Barre, Vt., and said he misses the skiing, hiking, and traveling around on the dirt roads in his native state. “I think Vermont is one of the few states where there are more dirt roads than paved roads,” he said. The only complaint Greg has about his Kia Niro is that he has been told that the Niro is fairly lightweight, so it doesn't get great traction in the snow, which is a concern when it comes to winter trips to Vermont.

But today was a beautiful August afternoon, no snow in sight, and as we headed out of the parking lot, we took a right-hand turn to look at the South Mountain barns. “Since sustainability is such a critical part of everything we do at South Mountain,” Greg said, “this is where we salvage and reclaim a lot of timber that was used before on other jobs, all over the country.”

When old buildings are being torn down, people will contact South Mountain and have the lumber trucked here. “It’s beautiful to be able to use this stuff,” Greg said. “The lumber can be 100 years old or more, and it comes from barns, hospitals, and various buildings all over the country. We even got the boards from the Oregon State Institution where they filmed One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. Sustainability bleeds into everything we do here; we’re very conscious of the carbon footprint.” Greg explains that as an architect, he loves to walk around out in the yard and see what lumber is available to him, and think about how he can work it into his jobs.

We concluded our back roads ride back at the South Mountain parking lot, where Greg said that driving electric cars can be a good influence on kids. He has a 10- and a 13-year-old, and said having an electric car has heightened the kids' awareness of the environment. “They’ll spot other electric cars,” he said, “and say, ‘Looks like that person is doing good things for the environment too.’ And they’ll start talking about what else they can do for the environment beyond the car, like recycling and composting. Actually, I think the schools on the Island are doing a great job of talking about these issues … we certainly never talked about stuff like this when I was a kid.”

All in all, Greg gives his Kia Niro high marks. He’s pleased with the range of the car, and likes its looks. It has a fair amount of room, enough to get to Maine and back with two kids and a dog — it was a little crowded but they made it.

“It’s also affordable,” Greg said. He leases the car for around $300 a month. A quick check online found used 2019 Niros going for between $15,000 and $25,000, depending on the mileage. He also was able to get a $2,500 federal rebate, in addition to a little less than that from the state.

The operating costs are considerably lower than a gas-driven vehicle as well, starting with the fact that there’s no gas to buy. Greg recently called up the Kia dealer in Hyannis and asked them what he should do for the 10,000mile service, and they said they could look it over, maybe tighten a bolt or two, but there’s no oil to change, so there’s really not much for them to do.

“Add to that what is perhaps the best reason of all for buying an electric vehicle,” Greg said: “You’re doing the right thing.”

Mercifully, neither Nessie, who rode in the back seat, or the car, had any signs of being skunked.Greg can charge the Kia right in the South Mountain parking lot.

In late March 2020, while Eastern Massachusetts — indeed the world — began tracking COVID numbers and fearing trips to the grocery store, the dismantling of Plymouth’s Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station, decommissioned in 2019, continued on schedule.

Dismantling a nuclear power plant is no simple feat, due primarily to its radioactive waste. As Rich Salzberg reported for The MV Times, “Pilgrim has 1,156 fuel rods in 17 dry storage casks. These are giant stainless steel cylinders nested in giant concrete cylinders. In the plant’s spent fuel pool, there are 2,958 fuel rods.”

Many applauded the decommissioning of Pilgrim, and hope to see the remaining 55 commercially operating nuclear power plants in the U.S. follow suit. They insist that nuclear energy is too dangerous; that waste disposal is too massive and longterm a problem; that the materials necessary for nuclear energy could fall into the hands of terrorists or a rogue government. Sure, nuclear energy might have been a necessary evil, they say, but now we have affordable solar. We have wind.

Others, however, argue that to achieve the necessary low-carbon energy future

we require, the U.S. doesn’t have time to wait for renewables to scale up; that renewables require too much land; that their energy output can be sporadic. That nuclear isn’t the answer, but it’s a key part of it. And that the cons of nuclear energy — the radioactive waste, accidents, pluto nium falling into the wrong hands — are exaggerated. While they don’t dismiss the risks that nuclear poses, they argue that the need for rapid-scale decarbonization makes the risks worth it.

But are the risks worth it? And is this debate moot, given the rising costs of nuclear reactors versus the plummeting costs of wind and solar? Is investing in nuclear power another way governments and industry delay acting on climate change, as some critics accuse?

Given that Biden’s climate adviser, Gina McCarthy, according to an April 1 Bloomberg article, said that nuclear energy should be one of the power sources eligible for a national clean energy mandate via the Build Back Better plan, it’s clear the conversation is far from over.

Put simply, when atoms are split — a process called fission — a tremendous amount of energy is released. Uranium and its resulting byproduct, plutonium, are the most common elements in nuclear power reactors. The energy released heats water into steam, which in turn spins tur bines to produce electricity. Paul Hawken, author of Regeneration: Ending the Climate Crisis in One Generation, has called it “the most absurd way humanity has ever invented to boil water.” Histor ically and almost universally, we’ve relied on coal or gas to do the same thing. But where coal and gas emit greenhouse gases, nuclear emits far less — 10 to 100 times less than coal, for instance.

“I see [nuclear energy] as an essential tool,” says Jacopo Buongiorno, TEPCO Professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering, and director of the Center for Advanced Nuclear Energy Systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

We can thank nuclear fusion for the sun and the stars, and here on earth, nuclear fission gives us a zero-carbon energy source. But nuclear’s magic can be dark — there are radioactive waste, weapons, and accidents. Despite those risks, does our urgent need to reduce carbon make nuclear energy our best bet right now?

support in Congress for nuclear.”

Dr. Sweta Chakraborty, a risk and behavioral scientist, agrees with Buongiorno, calling nuclear “the only carbon-free energy source that can deliver electricity 24/7/365,” and noting that it already supplies more than half of the carbon-free electricity in the U.S., though renewables play a necessary and key role too, she says.

Nuclear plants are “prohibitively expensive,” says a 2021 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) titled “‘Advanced’ Isn’t Always Better,” noting the expense makes it unappealing to private investment and fuels public skepticism of nuclear as a viable option.

Ellie Johnston, climate and energy lead with Climate Interactive, a not-forprofit think tank that grew out of MIT Sloan School of Management, and that models the impacts of climate change,

sees nuclear as part of the mix, “but we see renewable energy growing much, much more. And one of the big reasons for that just comes down to the economics of it. Solar and wind costs have been falling precipitously in the past decade-plus. And when we look at nuclear, that’s not the Buongiorno concedes that cost has been an impediment to nuclear’s growth. Projects in the U.S. and Western Europe, he says, have had cost overruns and schedule delays. “These are complex machines,” he reminds us. Consequently, “we need a change,” he says. “And the change is a change in technology toward … small modular reactors, or

The field of nuclear energy is abuzz with, as Buongiorno noted, micro reactors and small modular reactors, or SMRs. The two, while both considerably smaller than a traditional nuclear reactor, have different outputs. “Recently I have seen … less than 20 MW is [a] micro reactor, above 20 MW is a SMR,” explains Buongiorno. Put another way, an SMR could power a city, while a micro reactor could power a large factory or a community.

“You crank [micro reactors] out of a factory a little bit like you would do with cars,” he says, citing his own excitement at the prospect, then you “load them on the back of a truck, and … you get to a site, and that’s your power plant.” These micro reactors would be portable, requiring no onsite construction (which could reduce or eliminate the cost overruns and schedule delays that plague larger nuclear projects), power can be built up in smaller increments, which would reduce capital

risk, and, he says, many projects don’t need the energy output of larger reactors. There’s considerable excitement around these micro-reactors, including right here on the Vineyard.

Norman Foster, an architect focused on high-tech, and a key figure in the modernist movement, who lives part-time on the Vineyard, has been working with Buongiorno. Foster believes we’re moving toward a revolution in nuclear power. “Imagine a 20-foot-long container housing a micro reactor, which when attached to a similar-size generator, could power a small town, or be plugged in to energize a city block,” he described to Bluedot Living in an email. “Another module could convert seawater to jet fuel, and the process would help to deacidify the oceans. Similar units could desalinize seawater.”

These smaller, sealed units, he wrote, would be safe and maintenance-free. The fuel module would be replaced every five to seven years, and the uranium fuel is non-weapons-grade.

SMRs are also on the horizon, the design product of NuScale, an Oregon-based company, with a $300 million investment from the U.S. Department of Energy. SMRs can be also built more quickly and cheaply than traditional nuclear plants, although costs are significant compared with renewable energy sources, and even natural gas. While no SMRs are yet constructed, several are close to completion in Argentina, China, and Russia, according to a Scientific American story, and many more are under consideration around the world.

As always, with nuclear energy, the two as-yet-unresolved issues are nuclear waste disposal and safety. The 2021 UCS report notes that even with considerable interest in nuclear energy, growth has stagnated due, in part, to a chilling effect from the 2011 accident in Fukushima, Japan. It cites the current rate of construction of new nuclear plants around the world as

only barely outpacing the retirements of existing plants, such as Pilgrim. The report goes on to say that “nuclear reactors and their associated facilities for fuel production and waste handling are vulnerable to catastrophic accidents and sabotage, and they can be misused to produce materials for nuclear weapons.” UCS calls on the industry, policymakers, investors, and regulators to address these concerns fully before expanding any nuclear energy projects.

Dr. Ken Buesseler, senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and an expert in radioactivity in oceans, has seen the damage from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident up close. “When things go wrong, they can go very wrong,” he says. And while the nuclear industry likes to point out that there have been fewer than a handful of accidents, Buesseler isn’t so comforted. “If you think of three reactors in Japan, [plus] Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, you can say, ‘Look, five reactors had fatal accidents and meltdowns over something on the order of 450 commercial reactors over time.’ But you know, five out of 450 … you wouldn’t fly a plane if the odds were that bad.” Of course, he says, lessons have been learned. For instance, it’s highly unlikely that a reactor will now be built in a tsunami-prone area. But climate change, he notes, is creating profound changes to the planet, including to sea level rise. A safe site today mightn’t be so safe down the road. “No energy is independent of its consequences,” he says.

To address these legitimate safety

concerns, says Chakraborty, “up-andcoming advanced reactor designs also feature significant safety features — for example, with smart systems that will turn themselves off if any measurements change unexpect edly, without waiting for human intervention.”

Still, says Buesseler, “we have a nuclear waste issue that we’ve never dealt with satisfactorily.” Take Pilgrim, for instance. “That nuclear waste is going to sit in storage pools essentially until forever, or until they come up with someplace where they can collect it and store it in a safer manner.”

He compares it to pro ducers of fossil fuels not caring about its byprod uct, carbon dioxide. And look where that’s got us.

But Chakraborty suggests that concerns about waste are overblown. All the spent fuel used in the U.S. over the past 60 years only takes up one football field, 10 yards deep, she says. She rais es another point, too: “Having a strong nuclear sector allows the U.S. to play a role in international rulemaking on how and which nuclear materials are developed.”

Last year, she says, 38 national security experts wrote to Congress to argue that maintaining U.S. nuclear expertise and exporting new, U.S.-developed nuclear technologies is crucial to nonproliferation and national security over the long term.

Further, those urging the development and adoption of micro reactors, such as

don’t have the luxury of ignoring nuclear’s potential, they say, because, with the escala tion in electric vehicles, as well as popula tion growth, and, of course, the deepening climate crisis, only nuclear energy can meet this demand quickly and cleanly.

Just do the math, urges Foster. “The current rate of carbon dioxide, the prin cipal greenhouse gas, being spewed into the atmosphere is 36 billion tons per year, over 20 percent of which is created by the production of energy,” he says. “The reality

Norman Foster believes we’re moving toward a revolution in nuclear power: “Imagine a 20-foot-long container housing a micro reactor, which when attached to a similarsize generator, could power a small town or be plugged in to energize a city block. Another module could convert seawater to jet fuel, and the process would help to deacidify the oceans. Similar units could desalinize seawater.”

is that … only 2.1 percent of the world’s electricity is produced by solar, which is weather- and battery-dependent. Perhaps more strikingly, the world is dependent on fossil fuels for around 64 percent of its electricity needs — with all the knock-on effects of atmospheric pollution.”

Foster goes further to make a moral argument. “Societies which are deprived of [energy] suffer higher rates of infant mortality, lower life expectancy, less sexual and political freedom, and are more likely to be experiencing war or violence,” he says.

It’s fission — the splitting of larger atoms — that produces the nuclear energy we use now. But there’s growing excitement about fusion, which produces massive amounts of energy by doing the opposite — combining smaller atoms to create large ones. It’s

lasts for many thousands of years. What’s more, there is no chance of a meltdown.

Of course, where there’s promise, there’s investment, and some heavy hitters, including Jeff Bezos, are putting their money behind some fusion projects.

“For the first time in decades, there are serious breakthroughs that might make commercial fusion possible … in fewer than 15 years,” says Buongiorno. Fusion is similar to fission in many positive ways, he says. It’s carbon-free, dispatchable, has a low footprint, produces even less waste than fission, there’s broad availability of fuel (water), and, he says, “the physics of fusion eliminate certain safety concerns of fission, such as runaway reaction [like what happened at Chernobyl] and decay heat.”

Even with so much innovation and investment in nuclear energy, it’s a tough sell. Vineyarder Jorie Graham has made understand the potential of this coming generation of nuclear reactors. As a poet, she recognizes the power of language, and thinks that part of the problem with nuclear energy is public perception. Indeed, a doctor recommending an MRI barely

NMRI, for nuclear magnetic resonance cause of its negative connotations). But

the thoughts of many of us straight to meltdown. Graham is not alone in thinking nuclear energy suffers from a messaging problem, which is why, increasingly, we’re hearing references to “quantum reactors.”

Whether security and safety concerns are warranted — and

— “nuclear is bad, but climate change is worse,” she says — there’s far too much opposition to it in the Northeast, though it’s a different picture in various other parts of the country. In New England, “It’s not a conversation worth spending time on,” she says. “I can tell you that the chances of getting [nuclear] sited in Massachusetts are close to zero.” Rather, she thinks the focus should remain, primarily, on wind energy. “I would say there’s no way in New England to address a clean energy future without offshore wind.”

“There is no such thing as perfect technology,” says MIT’s Buongiorno. Renewable energy, which has a whole lot going for it, nonetheless can’t offer a constant and predictable supply of energy. And, while battery storage is improving in terms of capacity and cost, “the system becomes so large and so interconnected that it requires big transmission lines,” which boost cost and vulnerability should the lines become severed due to weather, or terrorism. And Buongiorno points to the vast land use required by renewable energy.

not — nuclear needs to be taken off the table in New England, she says. Whileporter of nuclear energy

With discussion of pros and cons feeling like a game of nuclear football, perhaps wwhe folks at Project Drawdown, which analyzed and compiled the top 100 solutions to climate change, put it most clearly, calling it one of the only “regrets” solutions they proposed. “Nuclear is a regrets solution,” they write, “and regrets have already occurred at Chernobyl, Three Mile Island, Rocky Flats, Kyshtym, Browns Ferry, Idaho Falls, Mihama, Lucens, Fukushima Daiichi, Tokaimura, Marcoule, Windscale, Bohunice, and Church Rock. Regrets include tritium releases, abandoned uranium mines, mine tailings pollution, spent nuclear waste disposal, illicit plutonium trafficking, thefts of fissile material, destruction of aquatic organisms sucked into cooling systems, and the need to heavily guard nuclear waste for hundreds of thousands of years.” Nonetheless, they conclude, it is, indeed, a solution. ”

IIt was a foggy summer morning when I drove up-Island; the fog became denser the farther I drove into Aquinnah. Although I've known Native Plant Associates founder Carlos Montoya for 15 years, I had never paid a visit to his home garden. He warned me over the phone that things were a bit of a mess — his son Josh was in the midst of building his home on the property. When I first moved to the Vineyard, it felt like every time I drove a new dirt road I was in a different state, and it definitely felt that way the moment I began driving on the dirt road into Montoya's 13-acre homestead.

Although mostly a New Yorker growing up, Carlos went to school in Madrid in 1952, and when his family moved back to New York, he loved visiting his mother's family’s Long Island home. At the time, the town of Wainscott was still mostly potato farms. Carlos first saw Moshup Trail in 1971 on a visit to his sisterin-law, who had just moved to the Island. He says the south-facing shore of Long Island has the same plants and feel as Moshup Trail. Growing up, he liked to prune plants and “keep certain areas clear” when visiting Wainscott. As much as plants were of interest to Carlos then (he says he declared that he wanted to be a forest ranger in 10th grade), he explains, “my mother's father was a diplomat, and that's what they wanted me to be. So I was on a track to join the Foreign Service.” Although Carlos studied for four years, and admits that he “wasn't too bad at it,” he said it wasn’t for him. He says he still keeps up on foreign affairs.

After that first visit to Moshup Trail, Carlos knew he wanted to live there. Following a separation from his first wife,

losing his Vermont home (along with other life losses), Carlos moved to the Vineyard in 1982 and started over. He'd been working for the New York Times News Service, but upon arriving here, the Vineyard Gazette had no jobs, so he decided he would find a way to specialize in the native plants and grasses he loved. Through a friend's recommendation, Carlos started working for Nick Freydberg to create a little pond from the stream running beside the Freydbergs’ Chilmark home. Freydberg was the head of the investors for the Oyster Watcha Midlands project in Edgartown. Carlos tears up when he relates how Nick was there for him at the lowest point in his life. The two men are so different, but became close friends.

The first investor on the Oyster Watcha site to build a house turned to Nick, who recommended Carlos, and the rest is history. Carlos’ passion was to preserve the fields, the meadows, the grasses and indigenous plants — he feels so fortunate to work with those who share this passion, first Nick and then others. In those early days, Carlos had no truck, so he hired Trip Barnes, who used a 1948 converted school bus to go to Sylvan Nursery in Westport to get the plants for his first job. It was all a “bit haphazard,” he says. He says he and Trippy were “like Abbott and Costello,” but things gradually got more professional after that.

For his business, Pitch Pine Nursery, which he operated for 12 years in West Tisbury, he was a full-service design contractor doing ornamental work.

Carlos wanted to know more about sandplains grasslands, the ecosystem native to much of Martha’s Vineyard. He

also in bloom during my visit.

5.

6.

known as

began to study, but it was mostly on his own — there isn't much formal education on the topic. In fact, Carlos explains, sandplains grasslands are globally rare and “only exist on Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, Cape Cod, and Eastern Long Island, where I grew up. They were geologically all connected, and grew apart.” Early on in his new career, Carlos says, he was always trying to mix native plants with the ornamentals.

During his time running Pitch Pine, he got Lyme disease, which forced him to take a two-year hiatus as he recovered. When he returned to work, he focused exclusively on sandplain grasses.

Before moving to Moshup Trail, he lived in rentals, and never had a garden of his own. Though he purchased his land in 1995, his Japaneseand Southwest-influenced home was not completed until 1999. There are a number of larger rocks around Carlos's home that came from digging out the foundation. Mostly Carlos manages nature around his home, not adding much. There is a small area planted with ferns around his front patio, then nature takes over. Carlos planted ferns because of the shade, explaining that it’s hard to revegetate around a house that has mostly shade.

Carlos has a wide

variety of native plants (to see the extent of what he has, see the photos on page 29). There are dwarf conifers that he trims back. There's Lysimachia, a genus with over 150 species from summer-flowering to evergreen perennials, according to Fine Gardening. There are volunteer iris, native Joe Pye weed (which can grow to six feet in the sun), boneset (a wetland native), sweet woodruff (a shade-loving ground cover). There’s lowbush blueberry, huckleberry, a stiff aster, lilies Carlos planted. Looking around, Carlos says that he probably planted just four out of everything we saw, and then they repopulated. “This is my favorite of all plants — little bluestem is the core grass of a sandplain grassland,” he explains. Most common in Midwest prairies, it’s also known as beard grass, and according to wildflower.org, is one of the East’s most important native prairie grasses. When I wonder what his family's Long Island place was like, he tells me his parents’ meadow was a “little bluestem meadow with a little bit of sheep fescue,” often used in erosion control. We pass a New England blazing star, a native coastal species that is “virtually pest-free, disease-free, and deer-resistant,” according to gardenia.net. Another of his “absolute favorites

Our native grasses, Carlos explains, are warm-weather grasses that don’t need to be mowed down.Carlos Montoya standing in front of his Moshup Trail home.

is bearberry.” Nearby is the prettiest butterfly weed I’ve ever seen. Carlos harvested rose mallow seed along Moshup Trail, then created plugs that he planted. “A plug is a grown plant that is only five inches deep and two-and-a-half inches wide,” he tells me. To Carlos’s complete surprise, after renting and rototilling an area where the new road runs to his son Josh’s home, still a work in progress, the whole area is sprouting knotweed, and Carlos is still trying to figure out how it survived. There are volunteer asters before we move onto a grassy area. “That’s mainly sedge, a native,” Carlos says, “rescued from a job on Chappy so it wouldn’t be thrown out. You have to hatchet it into plugs; you can't seed it. Once hatcheted, you can plant it, much like a hair transplant. You put a little sheep fescue in between, since it’s a natural companion.”

Carlos has not retired, but he is only doing native plants and native

meadow work. It’s exactly what he wants to be doing. Our native grasses, Carlos explains, are warm-weather grasses that don’t need to be mowed down. Carlos says his website describes it best: "What we do is sandplain restoration, and that’s all we do.”

With that, we've made a full circle around his home, stand on the new driveway, and look out to a pond I learn was once likely “a depression left over from peat harvesting days, of which there was a good bit in Aquinnah in the 19th century, when it was dried and used as fuel.” Carlos shared his deep passion for nature, keeping companion native species sharing growing areas. The landscaping I visited was subtle with deep textures. Visiting Carlos in his element where every detail has both his and nature’s imprint was a welcome delight.

Learn more about what Carlos Montoya is up to at nativeplantassociates. com/sandplaingrassland-community/.

Imagine several hundred homes in this place. Imagine no more sweeping views across the sandplain to the sea.

To preserve an 128-acre ecological gem, it took a man who loved planes more than money.

Icaught Mike Creato on a good day. Good day for me, but not so good for Creato. That’s because Mike Creato co-owns Classic Aviators, which takes people up for biplane rides from Katama Airfield, and because the weather was looking iffy — fog was creeping in over the dunes of South Beach — he wouldn’t be giving any rides that day. And I would have a chance to talk to him about the Katama Airfield, which his family has had ties to for generations. I specifically wanted to know about how this little gem of an airfield, carved out of some of the most expensive and desirable real estate on the East Coast, hadn’t been snatched up by developers years ago.

We sat down at Creato’s desk in a wooden hanger that housed a 1940 Waco UPF-7 biplane. This fire-engine red aircraft sat staunchly on a cement floor behind Creato’s desk, surrounded by all forms of spare parts and paraphernalia, and hanging on a wall in back of the plane was a large rack of moose antlers and an old poster of Winston Churchill proclaiming “Victory.” I felt like Eddie Rickenbacker was about to walk into the hangar at any minute.

Creato told me the improbable story

of how this little grass airfield by the sea came to exist in the first place. Today it’s the largest grass airfield in the country. Formerly pastureland, it was established in 1924 (making it one of the most enduring grass fields in the country), and used by the Curtiss-Wright Flying Service, one of the first flying schools in the nation, and later by the Martha’s Vineyard Flying Club, among others.

In a personal journal kept by Steve Gentle, Creato’s grandfather, Gentle wrote, “Many well-known aviators put their wheels down at Katama — Roscoe Turner, Howard Hughes, and Max Conrad — and there is some evidence that the Spirit of St. Louis was photographed at Katama.” In another entry Gentle wrote, “Many people still remember the air meet that was held in 1928, and was attended by around 10,000 people.”

Steve Gentle made his name as a masterful flight instructor, giving lessons to people at the airfield pretty much from day one. But when the stock market crashed, things got pretty quiet. Creato remembers his grandfather telling him that in the ’30s, a man came out from Florida every summer in a biplane and put on an airshow.

“The way he got things started,” Creato said, “he would throw a chicken out of the airplane as he flew by, and whichever local kid caught the chicken, got a free ride — there were no rules back in those days.”

The airfield was closed during WWII; the Navy used it for target practice, and had a rocket range and a gunnery range there. Then in 1944, Steve Gentle bought the airfield — the day before the Hurricane of 1944, which left pieces of the hanger scattered all over the field.

Gentle wrote in his journal, “The corrugated sheet metal was strewn all over the area, with the hanger doors blown across Herring Creek Road and into the pines.”

With no hangar and no electricity, Gentle was nonetheless undaunted, and reconstructed the hangar. From then on, he and his family had a hand in running it continuously until 1985. The story of the airfield is interesting enough, in and of itself, but even more fascinating is the story of the land upon which the airfield rests.

The area around the airfield is known as the Katama Plains, a remnant of the Great Plains that once covered much of the Vineyard’s south shore.

Naturalist and MV Times “Wild

Conservation groups were interested in preserving the flora and fauna, and realized that their interests were aligned, ironically, with the peoplePhoto by David Welch

Side” columnist Matt Pelikan wrote in an email, “Katama Air Park is one of the best examples of coastal sandplain grassland/ heathland anywhere in the world. The airfield preserves populations of specialized plants and insects that are adapted to storm winds, salt spray, and periodic fire. Even by the Vineyard’s high standards, Katama is an ecological gem.”

Creato takes me through a little of the geological history of the plains. He explains that it’s basically a washout from the glaciers. “Sometimes I’ll get to fly around with a geologist,” Creato says, “and they’ll tell me stories about how the Island was formed.”

Apparently, when the glacier rolled across the Island, it stopped near the north shore, piling up boulders and debris almost a mile high. When the ice melted, there were no boulders left anywhere to the south, just sand; and that’s what contributed to the forming of the plains.

“What gets me even more,” Creato says, “is that this was all dry land after the glaciers melted and reced-

ed. There was no seawater between the Cape and the Vineyard until about 5,000 years ago, and the ocean was 30 miles off South Beach back then, out by the edge of where the continental shelf is.”

With the airfield back up and running after the war, and many aviators returning to the Island, Gentle felt he had found his true calling. He ran a charter business and gave flight instruction, and his wife Dorothy ran the snack bar. While no one was getting rich, at least Gentle was doing what he loved most in the world.

“My grandmother would say,” Creato

recalled, “‘You have a year where you’re starting to get ahead, then one of the airplanes would need a new engine, and there would go your whole profit for the next two years.’ Then somewhere in the early ’60s my grandmother said, ‘You know, real estate is starting to take off; why not get a real estate license?’ They hung out a shingle, ran an ad in the paper, and after 30 days sold four houses, more money than they had made in the previous 10 years.”

With real estate giving Gentle a financial cushion, he stepped back from the airfield and leased out the operations to others. “People would come in and run it for a few years and see if they could make money,” Creato said. “Although I doubt many of them did.”

It was during this period that the airport came onto the radar for two special interest groups in particular — real estate developers and conservation groups. Conservation groups were interested in preserving the flora and fauna, and realized that their interests were aligned, ironically, with the people at the airfield.

at the airfield. They were both interested in managing the property, and the conservation people appreciated that the airfield maintained the land.Katama Airfield is one of the oldest grass fields in the country. Poster courtesy of M.V. Museum.

They were both interested in managing the property, and the conservation people appreciated that the airfield maintained the land.

Without the airport clearing and burning back the brush, the pastures would be carpeted in forests, much like it is today elsewhere on the Island. Creato says that he’s seen old aerial shots from the ’30s showing that from Squibnocket to Menensha, there was all pastureland, while today it’s mostly trees and houses.

In the ’70s Gentle made it known that he was interested in selling the airfield (to be run as an airfield), and he was approached by developers who were willing to pay him a fortune to buy the land. With quarter-acre zoning in Edgartown at the time, the 128-acre field could have potentially resulted in 120 units of housing. “My grandfather wouldn’t even entertain that idea for any amount of money,” Creato said, “because he would lose the airport and everything it stood for.”

Creato, just a young man at the time, suggested that rather than selling the airport, his grandfather could develop the 12 waterfront lots and sell them for three times more than he could get for the whole airport.

“Nope,” his grandfather insisted, “I’m not going to do it.”

But in 1979, the town of Edgartown formed an alliance with The Nature Conservancy and the state that would

prove to be the best of all possible worlds. In 1983, Edgartown, backed by a bond from The Nature Conservancy and a grant from the state, would offer to buy the airfield and operate it in the future. This would keep developers from potentially building 120 units of housing on the land. The town would hire a manager for the field, and lease it out to tenants in the future. And T

he Nature Conservancy would oversee the cutting and burning between the runways. The town offered Gentle $1.5 million for the purchase of the 128-acre tract. The deal was somewhat complicated because Gentle had leased some parcels of land to several small farmers, and had to spend about $700,000 getting the property through land court. That left

“Katama Air Park is one of the best examples of coastal sandplain grassland/heathland anywhere in the world. The airfield preserves populations of specialized plants and insects that are adapted to storm winds, salt spray, and periodic fire. Even by the Vineyard’s high standards, Katama is an ecological gem.”

–Matt Pelikan

“When you see Katama from the air, the only thing that’s left of what Katama used to look like is this swath of open field where the airfield is — everywhere else is houses and pine trees.”

–Mike CreatoMike Creato pilots the red biplane for Classic Aviators. His grandfather, Steve Gentle, helped preserve the land. Photos this page by Alison Shaw.

Gentle with around $800,000, a pittance compared to what he might have made had he sold it off to developers.

But as Mike Creato said, “It wasn’t all about the money; my grandfather added $800,000 to his retirement, so he knew he’d be OK, and he knew the airfield would live on in the future.” In 1986 the deal was finalized, and was the cause of much celebration. It was one of those deals where everyone — except the developers — seems to have come out ahead.

“When you see Katama from the air,” Creato said, “The only thing that’s left of what Katama used to look like is this swath of open field where the airfield is — everywhere else is houses and pine trees. I think everyone is pretty glad it’s here, environmentalists, aviators, and families who just love to sit outside and have breakfast at the diner and watch biplanes take off and land. And all because Steve Gentle liked airplanes more than money.”

Hanging on the wall in a hangar at the Katama Airfield, up by the moose antlers, is a piece of a P-15 Mustang WWII fighter plane, “the best-looking piece of metal you’ve ever seen,” Mike Creato said. In June of 1975,

people up for rides all day Saturday, but at the end of the day he said he was tired and would come back the next day. Creato, who was just 14 at the time, asked his grandfather if he could get a ride when he came back.

the Oxford Warbird Club, a group of military airplane enthusiasts, decided to come to the Katama Airfield and put on an airshow — and they were bringing the iconic P-15 Mustang.

“Everyone who saw the plane was captivated,” Creato said, “The pilot was a WWII veteran, and flew it like he’d been flying it all his life.” The pilot took