THE UNDERGROUND CITY

The Importance of Dance Music as a Subculture of the Modern City

BLAIR MILLWARD

Declaration of work

Acknowledgements

Glossary

Abstract

Chapter Breakdown

Chapter 01 - A Pandemic’s Destruction

Background, Context and Motivation of Study

Research Questions

Methodology

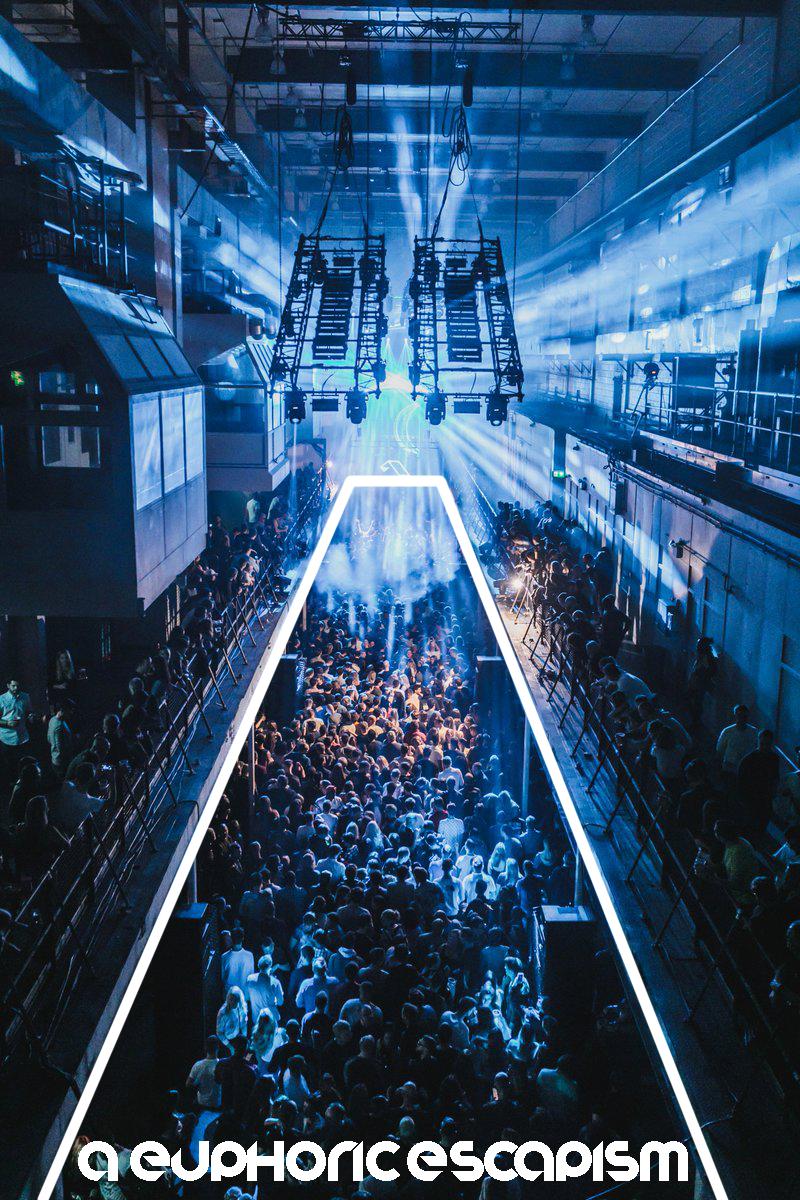

Chapter 02 - A Euphoric Escapism

Introduction

A Liberation from Civilisation

The Underground Community

The Identity of the City

Personal Experience

Conclusion

Chapter 03 - The Desolate City

Introduction

The Fall of the Motor City

The Bellville Three

The Second Wave

From Underground to Festival

The Detroit Identity

Chapter 04 - The Expressive City

Introduction

The Fall of the Berlin Wall

Exploring the East

Love Parade

The Mecca of Techno

The Berlin Identity

Chapter 05 - The People’s City

Introduction

The Fall of the Shipbuilding Industry

The Spirit of Sub Club

The Slam of the Arches

The After-Party

The Glasgow Identity

Chapter 06 - A Cultural Recovery

The Cultural Identity of the techno City Solutions of the Current Climate

The World Will Dance Again

Chapter Summary

Chapter 07 - Final Thoughts

Research Outputs

Limitations

Further Research

References

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my dissertation advisor, Will Gunn, for helping me to structure my research, and for his guidance, as his expertise and knowledge of my chosen topic was of great value.

I would also like to thank David Reat, for his teachings throughout my undergraduate degree within Cultural Studies, as his enthusiasm for the class has inspired me from the initial assignment in First Year, all the way up to this Dissertation.

Abstract

In light of the current global pandemic, the arts have been one of the hardest hit subcultures on the planet. Due to widespread public health policies in response to Covid-19, night-clubs, bars and festivals worldwide have all had to change the way that they operate. Many have been forced to temporarily close their doors or open with restrictions and limited capacity, causing many institutions to close for good due to economic viability. Along with their closure, so too has our cities’ cultural identities.

Music influences countless areas of civilisation, from fashion to the arts, and popular culture to architecture. It gives us a spiritual feeling of belonging and acceptance, ever since the

origins of ancient African tribal music, all the way up to present day rave counter-culture.

Many cities across the globe are facing a mass Exodus of arts venues. This is rapidly changing the identity of our cities. Without such spaces, culturally rich cities’ are vulnerable to losing their unique character.

Therefore, this thesis will analyse the impact that underground dance music has on the modern city. The findings will include detailed research on the sub-genre of Techno and it’s relationship with the post-industrial city. Furthermore, it will assess its impact on these cities’ personalities, and how their identities can recover from the devastation of the Coronavirus Pandemic.

Glossary

Better Off Alone - A 1998 Trance track by Alice Deejay. A timeless song which although was produced in the Netherlands, is revered in Scottish dance culture.

Good Life - A 1998 song by Inner City. It reached number 4 in the UK, causing the sound of Detroit Techno to cross the pond.

Got to be Real - A classic Disco track from 1978, and Cheryl Lynns debut single. It was inducted into the Dance Music Hall of Fame in 2005.

Lost in Music - a 1979 single by the American vocal group, Sister Sledge. Taken from their album, We Are Family, it was produced by Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards.

Step to Enchantment - A 1993 piece of music by Jeff Mills, released on his ‘Mecca’ EP. It embodies the spirit of the Second Generation of Detroit Techno, weaving through emotions of the 808 and 303.

Strings of Life - A 1987 single by Derrick May, under the alias Rhythim is Rhythim. It was a global success and brought Techno to the eyes of the world.

CHAPTER BREAKDOWN

The following is a summary of what will be covered in each of the chapters of this dissertation.

Chapter One will provide a background to the importance of underground dance music to the modern city. This will be portrayed by showing how music interacts with a cities’ architecture and culture, before explaining the progressive journey of dance music. This chapter will end with a brief overview to how Covid-19 has heavily impacted the musical world.

Chapter Two will provide a theoretical framework for the study through primary and

secondary research. Primary research will take the form of personal experience, with secondary research consisting of a literature review.

Chapter Three will cover the first case study, Detroit (The Desolate City).

Chapter Four will cover the second case study, Berlin (The Expressive City).

Chapter Five will cover the third case study, Glasgow (The People’s City).

Chapter Six will demonstrate relationships between the case studies and show ways in which underground artists have continued to perform live music amidst the pandemic. Finally, it will reflect on how the world will dance again.

Chapter 01

A Pandemic’s Destruction

This chapter will be an introduction to the paper, discussing the history of underground dance music, and the impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on the music industry. From this background, it will then set up the primary research questions and methodology used within the dissertation.

Background, Context and Motivation of Study

It encapsulates through an artistic medium what is happening culturally at the time, and, like a time capsule, preserves it for eternity. It has established communities and simultaneously differentiated them from one another. On the flip-side, it also integrates communities together

“I think music in itself is healing. It’s an explosive expression of humanity. It’s something we are all touched by. No matter what culture we’re from, everyone loves they are used (Constable, H, 2020). Throughout time, music has maintained a historical record of identifying with each and every era of civilisation.

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.1: Tribal dance of the Kurtz (Google image altered by author)

Figure 1.2: DJ and Dancers(Google image altered by author)

Figure 1.3: Vincent and Mia’s dance in Pulp Fiction(Google image altered by author)

Music is a necessity to our culture. It is so intertwined within our routines, that silence has become a rarity. Whether listening to an intense Jungle playlist in the gym (Figure 1.4), a Balearic house mix whilst cooking (Figure 1.5), or a

relaxing Indie album whilst studying (Figure 1.6), it is always present. It is used to both up-lift our moods and to drown-out the stress of the world around us when we are down (Skukla, A, 2019).

Music and Architecture

There is a correlating relationship between music and architecture. Many musical genres are often influenced by the architectural fabric of the cities’ that they are born in. Though they may seem like worlds apart, music and architecture have many common characteristics,

such as pattern, texture and proportion (Jencks, C, 2013). Thus, there is an exhilarating and continuous, repetitive tempo which harmonises the feeling of rhythm within both architecture and music (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.4: Headphones in gym (Google image altered by author)

Figure 1.5: Headphones while cooking (Google image altered by author)

Figure 1.6: Headphones during study (Google image altered by

Figure 1.7: Church drawn with musical notes (Google image altered by author)

Music and Technology

Throughout Baroque and Victorian era’s, classical music was the central genre that the world revolved around. This was mainly due to the technology that was accessible at the time, as well as the influence of bourgeoisie and taste (Cowen, T, 2018). However, only those who could afford to attend classical concerts could enjoy it, so, popular music could only be appreciated by the wealthiest in society (A, Arblaster, 2002). Nevertheless, with technological advances following the industrial revolution of the twentieth century, music became more accessible to lower classes. Due to underground communities now having access to a wider variety of music, counter-cultures and

underground sounds was established throughout the course of the 1900’s.

The LP was first introduced in 1931. Following World War Two, a social shift led to the introduction of the Cassette Tape in 1963, the Turntable in 1972, and the Sony Walkman in 1979 (Herzog, K, 2014). Arguably, the biggest impact of technology on music came from the introduction of Roland drum machines and synthesisers in the early 1980’s, which were designed in Japan, by Ikutaro Kakehashi. The Roland TR-808 revolutionised dance music (Figure 1.8), defining the sound of Hip-Hop, Chicago House and Detroit Techno (Leight,E, 2016).

Figure 1.8: The Roland TR-808 (Google image altered by author)

Disco fever

“Disco was like the celebration of music through dance and my God! When you heard the music sometimes it was like, if you don't get up and dance, you aren't human!”

- Grace Jones

“Disco music is the real punk rock” (Chambers, D, 2018). Indeed, just as Punk Rock emerged as a counter-culture expressing youthful rebellion against the political mainstream, Disco combatted the oppression of the LGBTQ community in New York City (Kimutai, K, 2018).

The Stonewall Rebellion of 1969 in Greenwich Village, saw the LGBTQ community stand up to police enforcement who tried to break up their gatherings (Figure 1.9). Following these riots, it became legal for two men to dance with one another, resulting in the evolution of Disco in Manhattan (Lorraine, I, 2019). Clubs such as The Loft and the Paradise Garage, along with DJ’s David Mancusso and Larry Levan made Disco an integral counter-culture of New York City (Figure 1.10).

However, following the 1977 movie, Saturday Night Fever, Disco became very commercialised,

overtaking Rock in radio play (Grogan, S, 2020).

In a country plagued by racism and homophobia, this then resulted in widespread anger and discontent from many white Americans, who wouldn’t accept the fact that the most popular musical genre within the USA had been by gay African-Americans.

A ‘Disco Sucks’ movement gained a massive following. It eventually led to the ‘Disco Demolition Night ‘of 1979, where thousands of people burned their Disco records at the Chicago White Sox stadium, and resulted in a crash of Disco radio play. The ‘Disco Demolition Night’ however has been proven to be an antiBlack music rather than an anti-Disco music protest, demonstrating the racism that marginalised communities faced in America (Petridis, A, 2019).

Figure 1.10: Protestors in the Stonewall Rebellion. (Google image altered by author)

Figure 1.11: Larry Levan DJ’ing in the Paradise Garage (Google image altered by author)

Lets talk about house

“There is always a point in the party where I wouldn't say I have people in the palm of my hands, but when there is a point in the evening... if you have been to any great party, you know when the whole room becomes one.” - Frankie Knuckles

Disco was a style of music that began with a powerful underground, yet suffocated once in a world of commercial attention. As a result, in the early 1980s, dance music lay dormant on the East Coast of the United States, but was ready to reach out of the shadows.

Chicago, the city that was responsible for the death of Disco, was also responsible for the resurgence of dance music, in the underground of the ‘Windy City’ (Figure 1.11). DJ’s began to remix music in new and inventive ways. The legendary Frankie Knuckles would remix songs in a night-club called ‘The Warehouse.’ He rearranged sections, changed the tempo, and extended breakdowns of energetic parts of Disco, Funk and Soul (Warwick, O, 2019). The mixes he created were a revolution to dance music, and is the inspiration of much of what we listen to today (Figure 1.12).

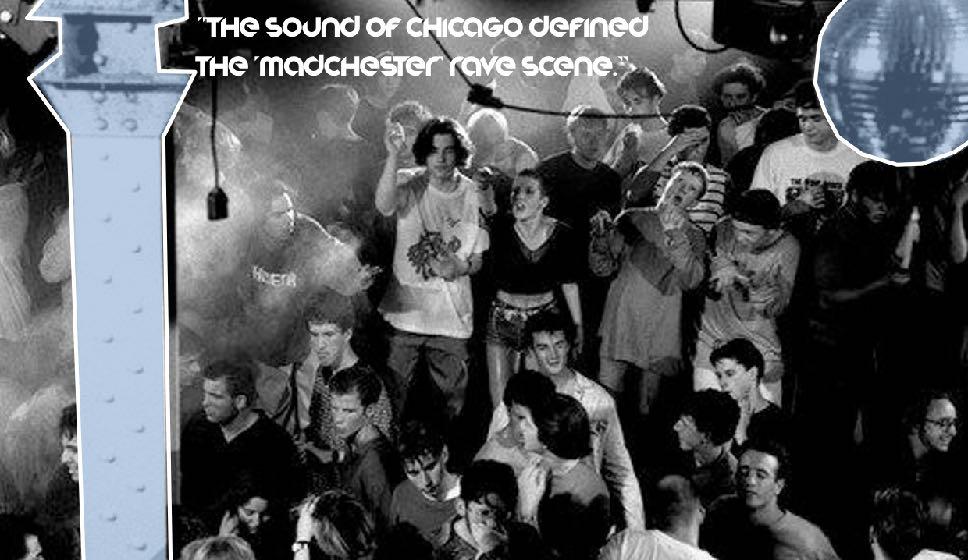

Chicago House and its sibling, Detroit Techno, took the world by storm after crossing the pond to Europe. The Acid House sound created by the Roland TB-303 in Chicago de f ined the ‘Madchester’ rave scene of the 1980’s in the UK (Figure 1.13), finding a spiritual home in the Hacienda night-club (Kirby, D, 2018). Dance music then spread like wildfire across Britain and Europe. It defined communities and sub-cultures on its journey, progressing into further underground genres such as Trance, Jungle and UK Garage (Jenkins, D, 2020). Dance music is still on an expanding journey through the Western worlds cultural character. Although it may have commercialised into mainstream EDM, which dominates the modern chart, underground dance music is still what maintains the tempo of the modern city (Toward, J, 2018).

Figure 1.12:

The Windy City (Google image altered by author)

The Covid-19 pandemic

Underground dance music is the core of many communities, and is the glue of society. Architecturally, the scale of the modern, musical space ranges from small, underground nightclubs to major capacity stadia (Stewart, J, 2019). Although the range establishes a wide scale of environments, from the intimate to the conglomerate, they all produce one paramount atmosphere - euphoria.

However, the euphoria of live music has been paused. The Covid-19 virus has swarmed the globe, affecting the economy, culture and life as we know it. The UK’s live music sector is facing an estimated loss of 170, 000 jobs, which is twothirds of its total work force. The industry is

expected to have an 80% decline in revenue this year (Sweney, M, 2020). This begs the question, where do we go from here?

Without creativity our world lacks spirit, and without live music our culture lacks joy. "You know what music is? God’s little reminder that there’s something else besides us in this universe; (a) harmonic connection between all living beings, every where, even the stars.”Robin Williams.

Thus, it will be the aim of this dissertation is to assess how important underground dance music is to the modern city, and suggest safe solutions to allow the music to play once more.

Figure 1.13:

The Hacienda Nightclub (Google image altered by author)

Research Questions

- How does underground dance music relate with escapism from society?

- How does underground dance music create a community for counter-cultures?

- How does underground dance music establish the identity of a city?

Methodology

The main objective of this dissertation is to investigate the importance of underground dance music towards the post-industrial cities’ cultural identity, and reflect on how the live music industry can reinvent itself in a postpandemic world.

This dissertation will unravel the concept of underground dance music being a euphoric escapism to modern society. This will be demonstrated through primary and secondary research, giving an overview of why clubbing is so important to the underground community.

Case studies of post-industrial cities - Detroit, Berlin and Glasgow - will be researched and analysed. Connections between the cities will be made, and the relationships between these cities’ industrial aesthetic and musical sound will be evident. This will highlight the history of oppression in these cities,’ and how it has led to established counter-culture communities.

Finally, the dissertation will review and suggest possible solutions to how music can be enjoyed within safe environments in the current climate, and discuss how live music will rebuild itself in a post-pandemic environment.

Figure 1.14: Abandoned diskothek in Austria (Google image altered by author)

Figure 1.15: Printworks, London (Google image altered by author)

Chapter 02

A euphoric escapism

This chapter will provide an analysis of how underground nightlife brings a euphoric escapism to everyday reality, through both primary and secondary research. An

overview of the theoretical framework will demonstrate exactly how essential this notion is to the modern city.

Introduction

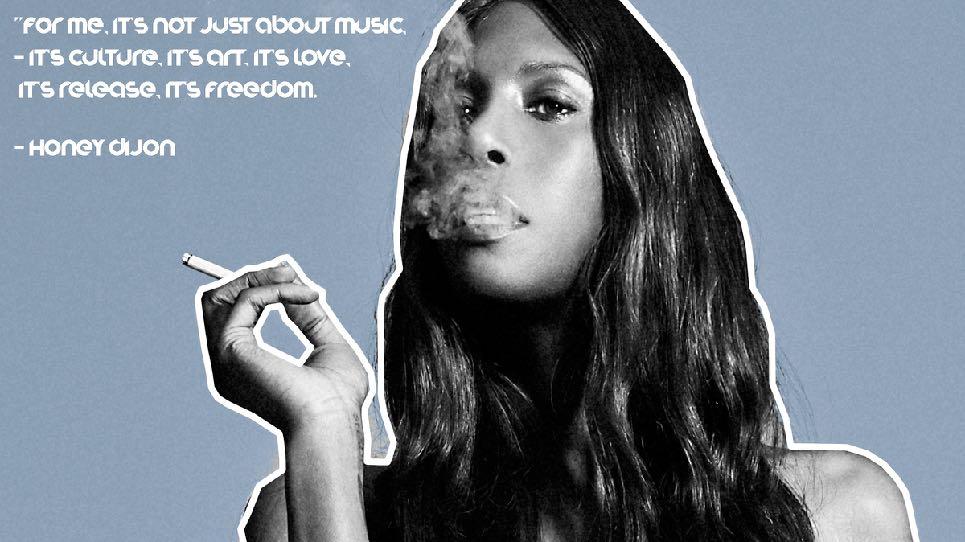

“For me, it’s not just about music - it’s culture, it’s art, it’s love, it’s release, it’s freedom” - Honey Dijon

From a psychological perspective, there are many factors as to why nightlife is such an essential element in modern society. Firstly, it relates to the human beings emotional thrill of dancing, which has been evident since cavemen danced around a fire. Dancing releases oxytocin (figure 2.2) - the love hormone - which relieves

stress and provides positive mental well-being (Salamon, M, 2013). Secondly, night-clubs allow the individual to explore their own medium of expression (Figure 2.3), which facilitates selfdiscovery (Moore, M, 2015). Finally, nightlife is somewhere where you can escape from the struggles of everyday life.

Figure 2.1: Honey Dijon (Google image altered by author)

Figure 2.2: Oxytocin - The Love Hormone (Google image altered by author)

Figure 2.3: Bongo, Edinburgh (Google image altered by author)

A liberation from civilisation

In order to analyse why the underground subculture is so critical to euphoric escapism, the discussion needs to address the appeal of nightlife and why humans want to disappear from the struggles of everyday life (Figure 2.5).

Escapism is defined as the tendency to seek distraction and relief from unpleasant realities. (Koh, V, 2017). This is highlighted by Chicago House DJ, Derrick Carter, who states “Life is hard. You gotta go bust your ass at a job eight hours a day, barely able to pay your bills… You need to be able to have a chunk of time to go somewhere, no matter what.” Furthermore, this is backed up by Peter Shapiro in his book Modulations, (Shapiro, P, 2000) in which he states that dance music is “A relentless four-tothe-floor machine beat, created by a ritual of

outlaw and desire and physical abandonment that existed outside the straight and narrow.” Thus, day to day life can be challenging, so we need somewhere in which we can be free.

Beyond escaping daily routine, the underground has an appeal because of the outlook it brings to life. This is conveyed in Robert Kronenburgs book, Live Architecture (Kronenburg, R, 2012), in which he states “The immersive experience of the gig, cannot be duplicated by any existing medium.” Hence, being in a crowd at a concert or night-club is a personal encounter which is independent from any other reality. In addition, Frank Owen, who was editor for Spin Magazine, stated that the Paradise Garage in Manhattan was a “Utopian community cut off from the surrounding city.” Thus, night-clubs are the Eden of the modern city, where being lost in music shields you from the outside world.

Figure 2.4: Escaping the life of 9-5 (Google image altered by author)

The underground community

Through the creation of underground dance music, communities have evolved, often through the shared experience of oppression, and coming together through their love of the beat. This is shown in Kronenburgs book ‘This Must Be The Place,’ (Kronenburg, R, 2019) in which he states, “It’s a social event, an afirmation of a community, and it’s also, in some small way, the surrender of the isolated individual to the feeling of belonging to a larger tribe.” Henceforth, nightlife unites people together who would otherwise be strangers, through the medium of music.

Albeit, underground nightlife isn’t the only way that musical communities are conceived. The illegal rave scene in the UK in the 1990’s gave a feeling of community on a larger scale (Mullin, F, 2014). The 1994 Criminal Justice and Public

Order Act attempted to ban free festivals and “music which includes sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats.” With Government policy at the time suppressing culture, it only fuelled the fire for counterculture, creating a united front against the Conservative Government (Figure 2.6).

The power of the community in rave culture is shown by Shapiro - “The rave phenomena is dificult to explain to anyone who wasn’t there.

You could call it an unruly union of disparate influences that proved temporarily explosive.” Due to a misunderstood mainstream, the underground community had such an impact without their realisation. By looking back now, we can see how modern music has been influenced by rave scene counter-culture (figure 2.7).

Figure 2.5: Protestors of the

image altered by author)

Figure 2.6: An illegal rave in a forest(Google image altered by author)

The identity of the city

In context of the overall cultural identity that underground dance music brings, it is important to assess the opinions of people who have experienced the power that music has on a city. It is often the marginalised residents of such cities that fully embraced the underground music scene, as a way of uniting against the oppression and discontent they faced. When a city gains that sense of freedom, the music that erupts in the underground is often revolutionary, and becomes the language that is understood universally. This is what creates the identity of the city.

An example of this occurred when East and West Berlin were separated by the Berlin Wall, between 1961 and 1989. When the wall came down, cultural freedom brought people together for the first time (Vasconcelos, A, 2019). Moreover, German politician, Klaus Wowereit described Berlin as a “Mecca for the creative class.” Furthermore, David Bowie, a musical icon who lived in Berlin, described the city as “the greatest cultural extravaganza that one could imagine.” Therefore, cities like Berlin, where freedom was once limited, are now bursting with culture. This is developed through the music scenes that have been established within the depths of the city, and the excitement and jubilation of being able to explore and re-define its genius loci (Figure 2.8)

Figure 2.7: 1997 Berlin Love Parade (Google image altered by author)

Personal experience

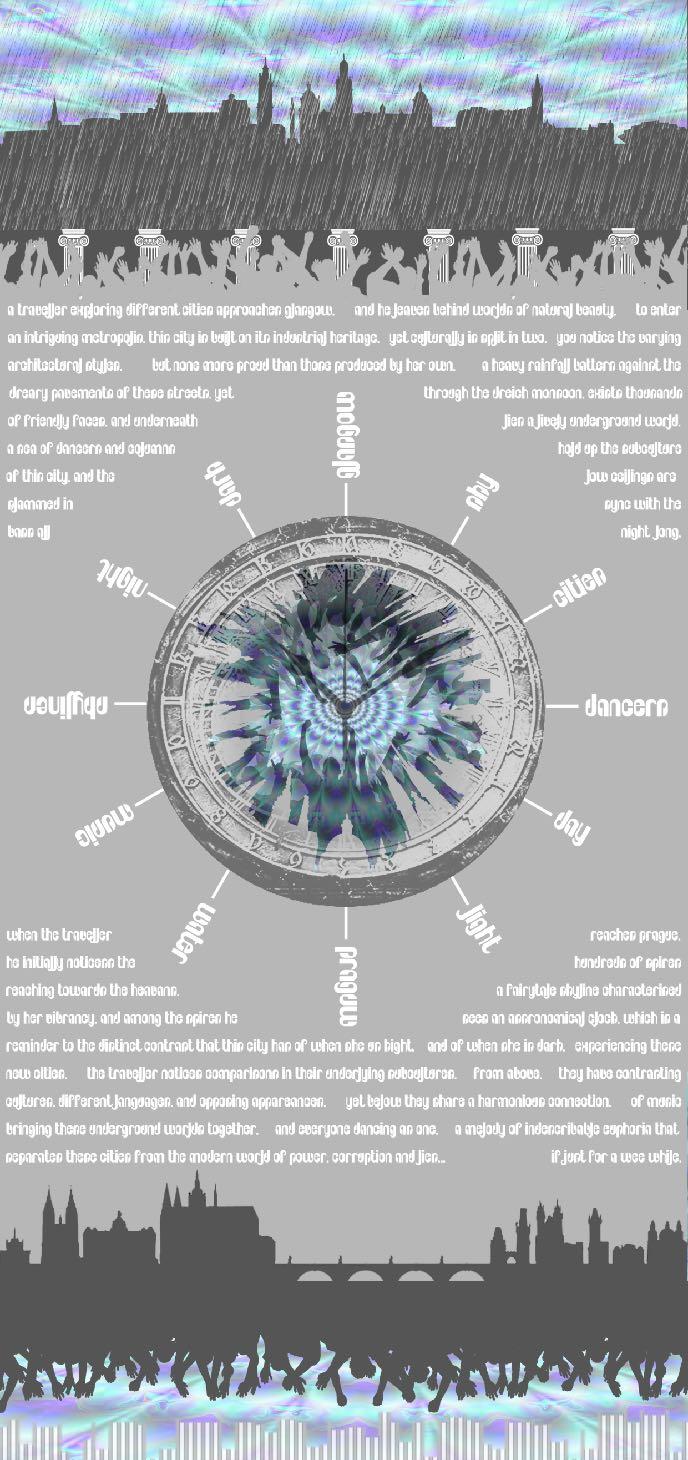

Secondary research has proven pivotal in developing a view on how important underground dance music is to a city’s cultural identity. However, primary research is also essential to gain an understanding at a personal level. As a young person moving to an unfamiliar place, the underground music scene has allowed me to integrate myself into the culture of various cities,’ providing me with a space for freedom and personal development. Indeed, this outlook has been established by my experience as both a student in Glasgow, and as an Erasmus student on exchange in Prague.

LIFE IN GLASGOW

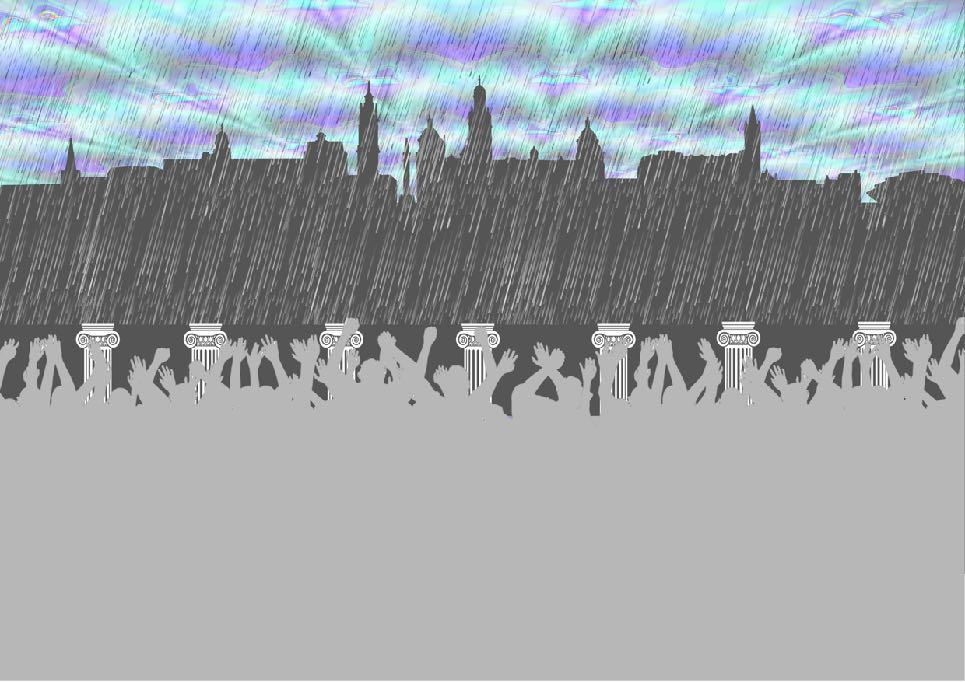

Studying architecture in the centre of Glasgow has been an exciting and educating experience. Unravelling the dimensions of the city through studio projects, sport and nightlife, has enhanced my understanding of what makes the identity of Glasgow. This is portrayed in a poetic exercise which I undertook in the style of Italo Cavino’s ‘Invisible Cities,’ in which I, the traveller, explore the city of Glasgow:

A traveller exploring different cities’ approaches Glasgow. He leaves behind worlds of natural beauty to enter an intriguing metropolis. This city is built on its industrial heritage. Yet culturally it is split into two.

You notice the varying architectural styles. But none more proud than those produced by her own.

A heavy rainfall batters against the dreary pavements of these streets. Yet through the drench monsoon exist thousands of friendly faces.

And underneath lies a lively underground world

A sea of dancers and columns hold up the subculture of this city. The low ceilings are slammed in sync with the bass.

Figure 2.8:

The Glasgow Underground (Authors own image)

Through my own understanding, Glasgow’s post-industrial architectural fabric is a complete contrast to the charming Scottish landscapes that surrounds it. The city’s obvious beauty isn’t a re f lection of its appearance, but of the community’s and culture that inhabits it. This is primarily a re f lection of its underground nightlife, in contrast to the chaotic weather above ground, where a vibrant underworld lies below.

Life in Prague

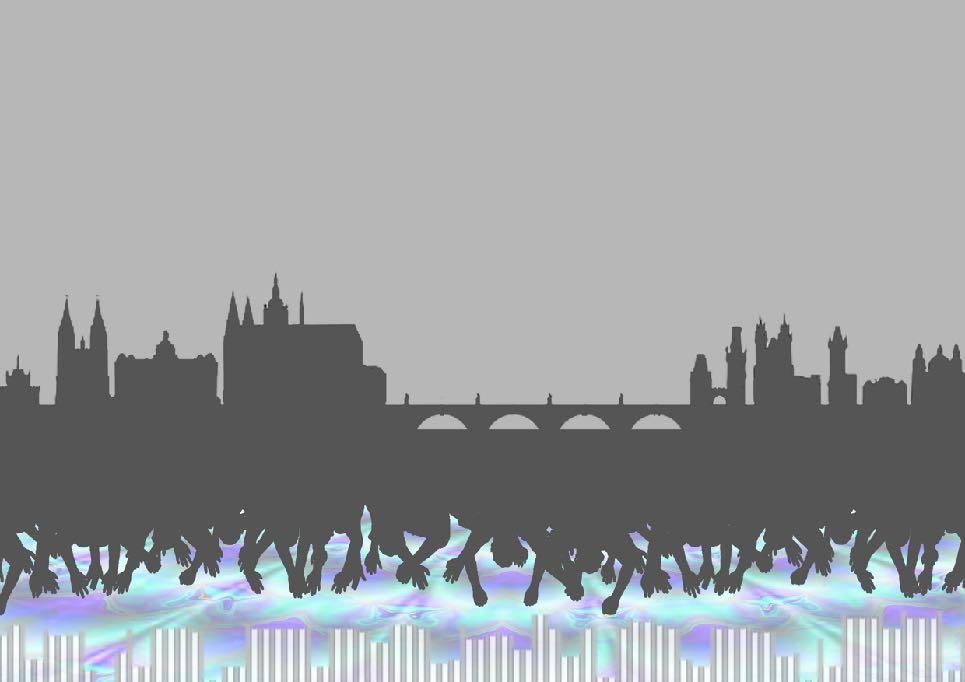

For my third year Erasmus exchange, I studied in the lively, medieval city of Prague. By living in another city with such a focus on nightlife, I gained a deeper understanding of the impact that underground dance music has on a cities’ identity. In a place with a contrasting culture and architecture to Glasgow above ground, underneath they share the same galvanising atmosphere. Through poetry I have enhanced my understanding of this concept:

Reaching Prague, the traveller sees a hundred spires reaching towards the heavens.

A fairytale skyline characterised by her vibrancy.

Above the spires he notices an astronomical clock.

A reminder to the distinct contrast that this city has when she is light.

And when she is dark.

The traveller notices comparisons in these two cities underlying subcultures.

From above they have contrasting cultures, different languages and opposing appearances.

Music brings these underground worlds together, with everyone dancing as one.

A melody of indescribable euphoria.

It separates these cities from the modern world of power, corruption and lies…

Figure 2.9: The Prague Underground (Authors own image)

Figure 2.10: Connections between Glasgow and Prague (Authors own image)

Thus, through my own analysis, Prague is a city which architecturally is much different than Glasgow, and has a di fferent culture and language. However, it is similar in Glasgow in terms of its relationship with nightlife. Therefore, cultural identity of a city through underground music has been proven through my experiences not just to Glasgow, but also Prague.

Chapter summary

Secondary research in the form of a literature review allowed discussion of the elements that creates a euphoric escapism - a liberation from everyday reality, the reasons for counter-cultural community’s in a cities underground, and the identity that is created for these cities as a result from underground dance culture. The researched dialogue brought forward interesting ideas, including that nightclubs are a “utopia” within modern cities, underground communities are created because of the notion of being part of a “tribe,” and when cities that were once oppressed are granted freedom, it generates a “Mecca for the creative class” in the city.

Primary research in the form of poetry through my own exploration of a cities underground elaborates on the concept of euphoric escapism. Through living in both Glasgow in Prague within my architectural studies, I have gained an understanding of what culturally helps these cities groove - underground dance music.

Therefore, through primary and secondary research, an overview of how underground nightlife brings a euphoric escapism to everyday reality has been established. With this analysis in mind, an in-depth discussion will be undertaken through case studies, exploring the postindustrial cities’ connection with underground

Figure 2.11: Techno Cities (Authors own image)

Chapter 03

The desolate city

This chapter will outline Technos birth in Detroit, and explore the journey that the city and its communities undertook to establish its industrial sound.

Introduction

“Techno wasn’t designed to be dance music. It was designed to be a futuristic statement” - Jeff Mills

Techno, the sibling of House, was born and nurtured in Detroit, simultaneously to the development of House music in Chicago. However, where House was associated with a soulful aesthetic of post-Disco, Techno was associated with the avant-garde, sci-fi sound created by Kraftwerk

They differ in that Techno has a higher range of tempo than that of House, giving it a distinct, faster-paced sound (Jukely, T, 2018). However, what differentiated the sound of Techno the most from House, was the darker aesthetic that was produced. This was a reflection of the the city which it was discovered in.

Figure 3.1: Jeff Mills - “The Wizard” (Google image altered by author)

Figure 3.3:

The Motor City (Google image altered by author)

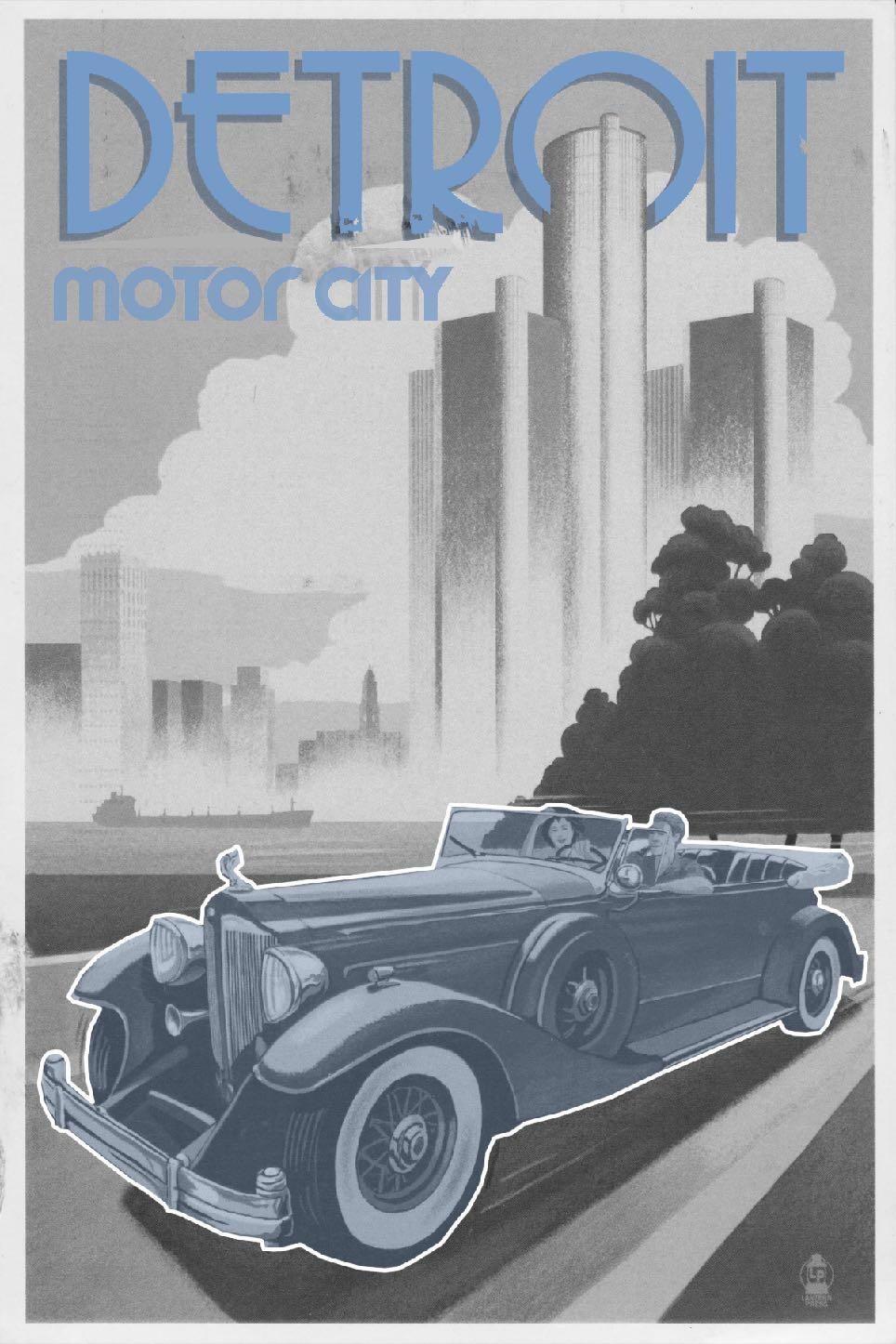

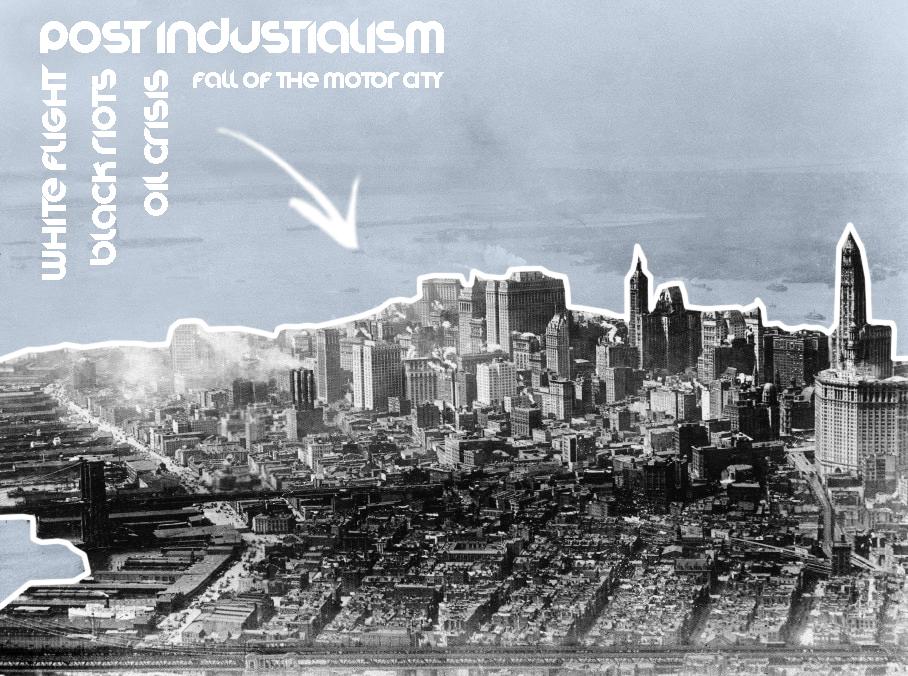

The fall of the motor city

In the early 1980’s, Detroit, a city that was once an industrial powerhouse and the futuristic metropolis of America, was losing its persona. At the beginning of the Twentieth Century, Detroit was home to General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford Motor Company. It attracted the best hands and brains in the US (Lee, S, 2018). The worker’s salary here was twice as high than in other cities of the country, making it a city of industry. Detroit was a force to be reckoned with (Figure 3.2).

However, after reaching its peak of development in the 1950’s, Detroit began to crumble under the force of its own greatness (Palladev, G, 2015). As a result of a range of factors, primarily white f light, black riots caused by alcohol prohibition and the 1973 oil crisis, Detroit faced a dark decline with the struggles of postindustrialism (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.4: Fall of the Motor City (Google image altered by author)

Figure 3.5: Techno’s sci-fi aesthetic (Google image altered by author)

The Bellville Three

Despite Detroit's descent into darkness, “a phoenix rose from the ashes of the crumbling industrial state.” - Juan Atkins. In 1983, A trio of musicians, consisting of Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson, who met at Bellville High School, experimented with music. Inspired by the post-industrial landscape that surrounded them, they took the sound of House that had been created in Chicago and re-defined it. They raised the electronic content and made it more

futuristic. Indeed, Atkins states that “the music is just like Detroit - a complete mistake. It’s like George Clinton and Kraftwerk stuck in an elevator.”

Atkins, “the originator,” May, “the innovator” and Saunderson, “the elevator,” individually devoted themselves to the new music of Detroit (Figure 3.5). Together, they are “The Bellville Three” and as a trio they brought Techno to the world (Simms, Sara, 2017).

Figure 3.6:

The Bellville Three (Google image altered by author)

The Second Wave

Following the success of “The Bellville Three,” Techno crossed the pond, and helped to define the Acid House and illegal rave culture within the UK. However, the sound had been mutated and misunderstood. On its return to Detroit in the early 1990’s, the sound went back into the city’s underground, with a new range of creative approaches and artists.

Detroit Techno returned with a brutalist, harsher sound, characterised by strong riffs and the feeling of an industrial wasteland. (B, K 2015).

Some of the most important characters of the the second wave was Jeff Mills, Mike Banks and Robert Hood, who founded the group Underground Resistance (UR) (Figure 3.6). Banks brought an aggressive approach to Techno, whereas Hood delivered a minimalist sound to the genre, but Mills, who was known as “The Wizard,” mastered the craft of disk jockeying.

“The Wizard” was an architecture student who took his artistic craft as a Step to Enchantment within DJ’ing. He blew away crowds with his hiphop style of fast paced mixing. DJ John Collins states “No one had ever done what he was doing. I couldn’t believe my eyes and ears.”

UR wanted to establish a means of identification beyond traditional lines of race and ethnicity. By targeting lower class African Americans, they inspired black men to get out of the poverty cycle in the city, helping them to form communities through music (Orlov, P, 2018). Just like Public Enemy with Hip Hop, UR brought a militant approach to Techno, which was directly related to the freedom fighting Black Panthers. In Dan Sicko’s book, Techno Rebels (Sicko, D, 2010), he describes UR as “a kind of covert musical operation set on toppling the industry establishment.”

Figure 3.7:

Due to white flight, Detroit was a ghost town full of empty spaces. The underground community took advantage of the city, by turning abandoned warehouses into illegal, music venues (Glazer, J, 2014). Richie Hawton, a leading exponent of minimal techno was at the forefront of the warehouse scene, throwing parties every weekend (Wo, E, 2018). However, in 1997, the police cracked down hard on the movement, causing its eventual collapse (Figure 3.7).

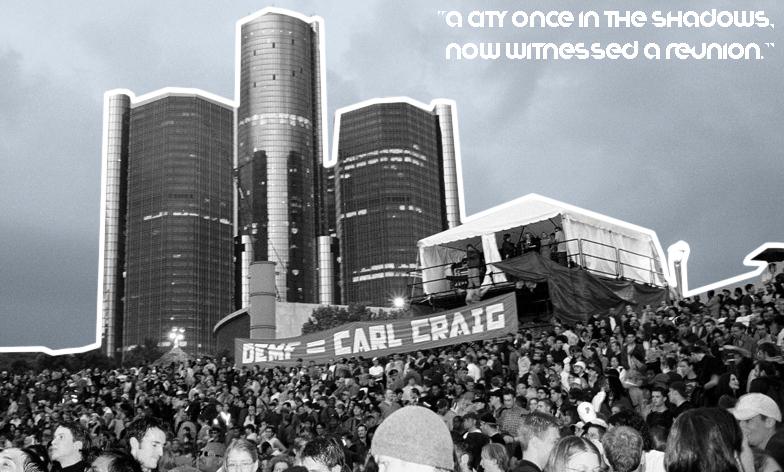

Nevertheless, in 2000, the Detroit Electronic Music Festival (DEMF) was held. It was the first major showcase for electronic music in the city. Yet, its impact was deeper than anyone could have imagined. Detroit, a city that was once in the shadows, now witnessed a reunion of the city with its own, homegrown talent. Hence, this was an emotional and magical time for a city that re-discovered its spirit through underground dance music (Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8:

The Detroit Warehouse Scene (Google image altered by author)

Figure 3.9: Detroit Electronic Music Festival (Google image altered by author)

The Detroit Identity

Detroit is a desolate city. The traumatic consequences of post-industrialism resulted in a withdrawal of vibrancy. The communities of the city went to the underground to escape the harsh realities above.

Nevertheless, Detroit is deceiving. The counter-

cultural communities in her underground have re-invented the cities perception, through the medley of dance music. Despite Detroit’s derelict identity, there is also light within the darkness, and she can rebuild herself from a grim existence, into a Good Life, for the communities within (Figure 3.9).

Figure 3.10: The Desolate City (Authors Own Image)

Chapter 04

The creative city

This chapter will detail the influence of Techno in Berlin, and interpret the history of the city’s cultural freedom.

Introduction

“All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin. And therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words, ‘Ich bin ein Berliner!’ (‘I am a Berliner)” - John. F. Kennedy.

Electronic music has bounced back and forth between Germany and Detroit since 1970, when Kraftwerk created the soundtrack for the digital age (Figure 4.1). Although, the underground artists of Detroit revolutionised Kraftwerk’s vision into the industrial sound of Techno, the music

returned to Germany in 1989, as a sound of freedom following the fall of the Berlin Wall (Omri, 2019).

lourished into an unstoppable ined Berlin as the

Figure 4.1: Kraftwerk - The Pioneers (Google image altered by author)

Figure 4.2: The Berlin Wall (Google image altered by author)

The fall of the Berlin Wall

For almost three decades, between 1961-1989, a man-made barrier divided the city of Berlin (Figure 4.2). The German capital was separated between East and West, in the hope of splitting a capitalist ideology from a socialist enclave (McCartney, W, 2019). The Berlin Wall is one of the most powerful and enduring symbols of the Cold War (history.com, 2019).

On 9th November, 1989, after months of demonstrations and a considerable amount of people fleeing the country, East Germany opened the border crossings and let people pass freely (Figure 4.3). As a result, the barrier which had divided the city for almost three decades was breached and Berlin erupted in celebration (Peter, B, 2019).

Techno was the common musical language that brought young people together after the wall came down. It travelled from Detroit to Germany at the right place, and at the right time to become the first major German youth culture of the post-wall era (Collin, M, 2018).

Techno was to become the soundtrack of reunification, and Berlin was to be its spiritual home.

Figure 4.3:

The Fall of the Berlin Wall (Google image altered by author)

Exploring the east

After the Berlin Wall was demolished, West Berliners were given free rein to explore the Eastern half of the city. Two very different cultures met, and they unified through dance. As West Berliners could avoid military service, culturally they were initially defined as more alternative and creative to East Berliners (Glynn, P, 2019). Due to their creativity, they discovered empty warehouses, factories and power plants left abandoned from the collapse of the East German regime. The spaces were re-colonised to host parties, and the police had no authority to stop them. Ex-punk Thomas Andrezak states that ”Techno was the first youth culture that started at zero on both sides. All of us came together at this zero point and there was no difference where you were from.”

An important venue within this visionary scene was Tresor, opened in 1991 by Dimitri Hegemann, which still runs to this very day. The original space was a Jewish-run department store that closed in Nazi Germany (Figure 4.4). When it was re-discovered it was still full of old contents from the bank’s vaults and old industrial equipment, making it the perfect setting for an underground club that would change the tempo of techno music and turn heads from around the world (Martynov, R, 2016). Hegemann states “It was a perfect location, right near the wall, perfect for kids from east and west to come together. It was symbolic of a new beginning and a new generation of music” Thus, Tresor defined the new sound of the city, which was much heavier than the sound of Detroit (Beattie, A, 2018).

Figure 4.4: Tresor set the tone for the new Berlin (Google image altered by author)

Love parade

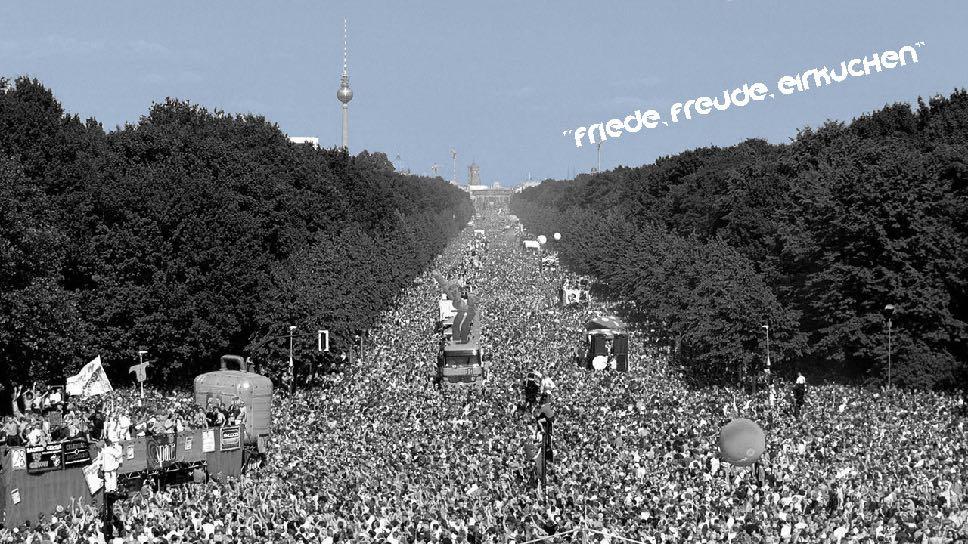

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall and as the Techno scene in the city gained a following, an open-air rave called the Love Parade became the sub-cultures public symbol. The slogan “Friede, Freude, Eirkuchen” was chosen, which means “Peace, Joy, Pankcakes,” (Smith, J, 2016). It was the first open air rave in Berlin for electronic music, promoting the raver’s values of good

Techno venues and labels such as Tresor. By 1997, the Parade had been moved to Tiergarten Park in the centre of Berlin and over a million people had joined the celebration (Brian, S, 2019). Writer Sven Von Thulen states “The Love Parade made it possible to have a million people on the street like that and not think of Hitler. It really changed the perception of Germany and of Germans.” Thus, the Love Parade put the new identity of Berlin on the worldwide map, as a symbolic reclaim of public space for communal

Figure 4.5: 1997 Berlin Love Parade (Google image altered by author)

Figure 4.6: Inside the Berghain (Google image altered by author)

The ‘Mecca’ of techno

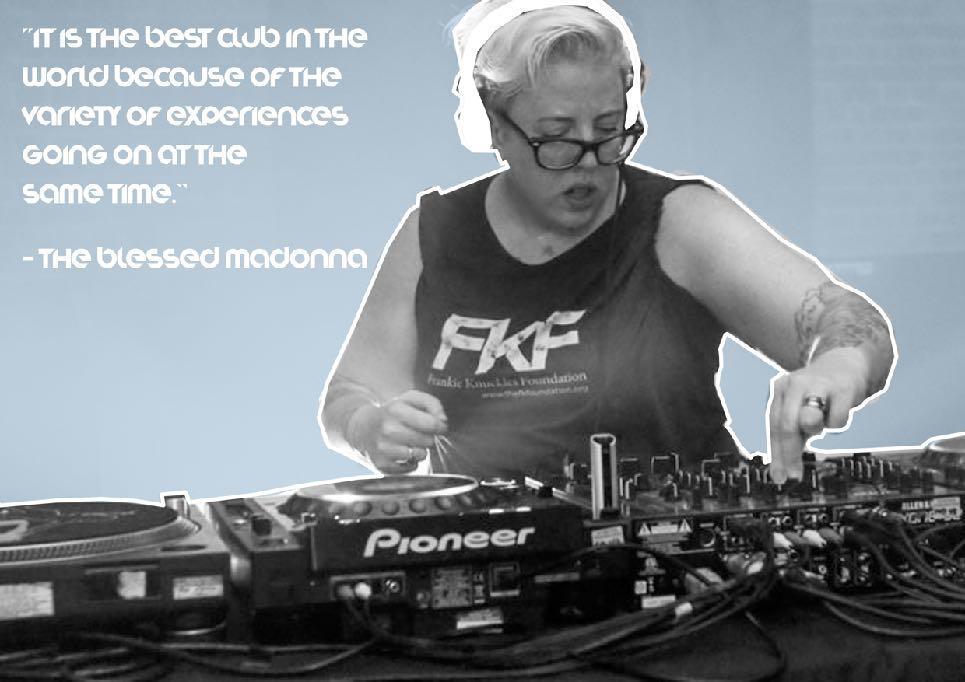

A renovated power plant in East Berlin, the Berghain, opened in 2004, and is widely considered the cultural temple of Techno (Figure 4.6). The musical focus is dark and hardcore, and it is a place to explore freedom and sexuality. Its high ceilings, industrial aesthetic and chaotic bass creates a force of nature that goes beyond the city of Berlin (Wurnell, M, 2016). “It’s the best club in the world because of the variety of experiences going on at the same time” - The Blessed Madonna (Figure 4.9).

Berghain is notorious for it’s selective door policy, most notably by the famous Sven Marquardt, who is regarded as one of the most intense bouncers in club history. Nevertheless, this is to maintain the vibe inside, and to combat the ‘Easyjet Raver,’ in which many Berliners feel that mass tourism is ruining the atmosphere and identity of Berlin’s nightlife which they have created (Poelti, A, 2016).

There is a strict no-camera policy inside, and being caught doing so results in being thrown out. What happens in the Berghain, stays in the Berghain. Hence, it is an environment which counter-cultures to the rigid codes and behaviours that are upheld in mainstream urban life (Carlos, L, 2019). It symbolises the freedom of Berlin and is a religious experience of underground expression (Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7: Queuing outside the Berghain (Google image altered by author)

passion. An escapism from such captivity has allowed communities to weave together, creating an ecstatic underground environment for the new Berlin.

Berlin encompasses an identity of freedom. It is a place of art, music and craft, made possible by the communities within this post-industrial, and historical setting (Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.8: The Expressive City (Authors Own Image)

Figure 4.9: The Blessed Madonna (Google image altered by author)

Chapter 05

The people’s city

This chapter will distinguish the importance of dance music to Glasgow, and the down-to-Earth personality of the communities that produces her sociable culture will be displayed.

The Glasgow of today boasts a wide range of music venues, from the cutting edge SSE Hydro, the sweaty basement of Sub Club, or the grassroots King Tuts Wah Wah Hut. Musical talent is of wide variety here, with successful

bands having emerged out of the city such as Texas, Primal Scream and Simple Minds

“The great thing about Glasgow is that if there’s a nuclear attack then it’ll look exactly and never looked back (Chester, J, 2015).

There is a vast range of dance music that is enjoyed with Glasgow, most notably Trance, House and Techno. Nonetheless, the sound of Techno in particular de f ines the cities’ underground, as just like in Detroit and Berlin, it is largely due to the industrial environment that the music reflects.

Figure 5.1: Glasgow mural for the ‘Big Yin’ (Google image altered by author)

Figure 5.2: Slam outside Livingston Tower

(Google image altered by author)

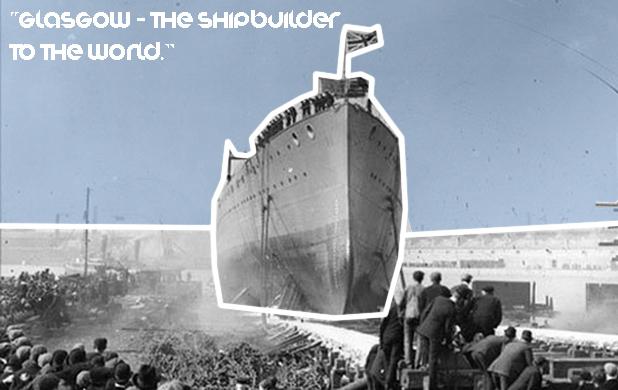

The fall of the shipbuilding industry

Glasgow has a deep history with industry. Scotland was once the shipbuilder to the world and the heart of its industry was in Govan (Figure 5.2). The largest crane in the world, with a maximum lift capacity of 250 tonnes, was built at the Govan yard in 1911. At its peak directly before the First World War, the Fairfield Shipping Yard in Govan directly employed 70, 000 workers in 19 yards (Brocklehurst, S, 2013). Thus, Glasgows industry of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was the envy of the world as a city of hustle.

However, after the Second World War, the Clyde struggled to compete with emerging industries

in Asia. Moreover, due to the rise in the Motor Car, by the late 1960s, there was little demand for passenger liners, ferries or steam locomotives (Moss, M, 2004). By 1988, the Clyde had faced unimaginable decline and the Fairfield yard was sold to the Norwegian Kvaerner group, resulting in Margaret Thatchers Conservative government denationalising the industry (The Newsroom, 2016).

Glasgow, once a city with a thriving industry now faced considerable post-industrial decline. Nevertheless, Glasgows spirit has always shone through, even in her darkest hours. In the late 1980’s electronic dance music arrived in the city, and the character of Glasgow prospered within the underground.

Figure 5.3: Glasgow - the shipbuilder to the world

(Google image altered by author)

The spirit of sub club

Scotland and Glasgow in particular punches well above its weight in atmosphere and musical legacy. Ciordsan Brown states “there is a bonding that happens in a Glasgow crowd when they hear an amazing tune. Everyone just goes nuts.” Combining the essence of the community with licensing laws forcing clubs to shut at 3 a.m. brings an urgency to the night, in which every minute is spent dancing (McDonald, K, 2011).

Sub Club has been the epicentre of Glasgows underground for over thirty years (Figure 5.3). Residing deep below 22 Jamaica Street, its bodysonic dance f loor and unparalleled atmosphere has brought the freshest, electronic dance music to the city.

Launched in 1993, Subculture, ran by Glaswegian DJ’s, Harri and Domenic, is the longest running underground residency in the world. When Jungle was becoming the new trend of dance music, they stuck to the records that they believed in - House and Techno from Detroit - which was imported into the nearby record store, Rubadub. They have set the musical standard for the city, with Sub Club at the heart of their journey (Thomas, B, 2017).

During the Coronavirus Pandemic, Sub Club raised a crowdfunder, ‘Save Our Sub,’ which raised over £170, 000 in under 24 hours, highlighting what the club means to the city (Hinton, P, 2020). Thus, Sub Club is fundamental to the underground communities of Glasgow. It is a place where memories are made, and personifies the spirit of Glasgow.

Figure 5.4:

The heart of Glasgows underground (Google image altered by author)

the slam of the arches

When Glasgow won European City Of Culture in 1990, public money had poured into the city for large-scale projects. One of these, a temporary exhibition called Glasgow’s Glasgow, led to the unused support arches under Central Station being converted. The venue was then turned into an underground music venue called The Arches, and it became the Techno capital of Scotland (Richardson, A, 2006).

Whilst Harri and Domenic brought the sound of Detroit to Glasgow, the darker sound of Berlin was brought to the city by Slam, at their infamous night, Pressure (Figure 5.4). Just like

Detroit and Berlin, the sound of their production was also a reflection of the post-industrial architecture that dominates Glasgows skyline, and the underground went wild for the music (Soma, 2020).

The Arches brought the underground sound to the limelight of the city (Figure 5.5). It had gained worldwide attention, bringing in both homegrown talent and the biggest names in Techno, such as Carl Cox, Richie Hawton and Laurent Garnier on a regular basis (William, C, 2020). However, the venue closed in 2015, leaving behind a gap within Glasgows culture (Gardner, L, 2015).

Figure 5.5:

The Arches (Google image altered by author)

The after party

In the 1960’s and 70’s, thousands of families were cleared from slums into new social housing developments in the outskirts of the city (Figure 5.6). Empty spaces have been left behind, and warehouses have been turned into illegal rave venues within the cities’ underground.

Glaswegian counter-cultures have created one of the largest underground “afters” scenes in the UK (Pollock, D, 2020). These events form the cities culture. The people within Glasgow are persistent, and they do not cave into politics constructing licensing laws (Figure 5.7). They are Better Off Alone.

Figure 5.6: Red Road Flats (Google image altered by author)

Figure 5.7:

‘Checkmate’afterparty in Tradeston (Google image altered by author)

The Glasgow identity

Glasgow is a city for the people. It may appear to be dreary and bleak due to its struggle with the fall of the shipbuilding industry, empty spaces and harsh weather. However, the communities are what makes her so lively and energetic (Figure 5.8).

Glasgow has an optimistic identity. The warm nature of this city make it unique, characterised by the underground communities that co-exist within. A city that has Got To Be Real.

Figure 5.8: The People’s City (Authors Own Image)

Chapter 06

A

cultural recovery

This chapter will analyse the connections made between Detroit, Berlin and Glasgow, to create one overall, cultural identity of ‘The Techno City.’ Furthermore, it will explore the current ideas being used to maintain live music throughout the Covid-19 Pandemic. Finally, it will reflect on how underground nightlife will return in a postpandemic world.

“Tomorrow belongs to those who can hear it coming” - David Bowie

The Cultural Identity of the Techno City Detroit, Berlin and Glasgow complement one another through many factors. They have all experienced post-industrial change, leading to grim periods within their history. However, each of these cities’ have overcame their darkest hours, by uniting through the medium of underground dance music. Initially, the nightlife of these cities was escapism from modern reality. They have gone beyond the underground into creating new cultural identities for these cities, established though freedom and a celebration of music.

Real cities produce real people, and their personality shines through negativity. Although the Covid-19 Pandemic poses an astronomical threat to the identities that have been shaped within cities like Detroit, Berlin and Glasgow, it cannot shatter their dynamic charisma. Cities with personality have the ability to rebuild themselves. Therefore, when the Coronavirus is a mere flashback of the past, the modern city will move their body once again (Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.1:

The late David Bowie - an artist ahead of his time (Google image altered by author)

Figure 6.2: The underground of the postindustrial city.

(Authors own image)

Solutions of the current climate

In a musical world now dominated by the streaming service, an artists primary source of income is through live concerts. Indeed, technological developments have always influenced the music industry, from the LP to the CD. However, online music streaming has now considerably overtaken physical sales and digital downloads of music (Smith, S, 2019). Thus, an artists focus on income is now primarily within live musical performance. However, artists have been locked in their homes, with few ways to generate income. (Ravens, C, 2020)

Nevertheless, over the course of the Covid era, the arts have attempted to make safe solutions to allow live music to play to some degree.

Live streaming

As a community, underground DJ’s have been extremely hard-hit by the global pandemic. However, history shows that in periodic

collapses to the global system, new ideas can be catapulted into the world (McDaniels, R, 2020). Thus, the livestream has invented a new way for music to reach fans (Figure 6.3).

For example, on Beatports Twitch channel, over 100 million people have tuned in to watch hundreds of DJ’s perform live (Bain, K, 2020).

The CEO of Beatport, Robb McDaniels states

“While the closing of nightclubs and festivals around the world has irreparably harmed so many hard-working people, the bright spot is that music fans are finding new ways to connect and dance in smaller groups and more socially distanced locations.” Therefore, although it is not the same experience of live music face to face, the live stream has created a unique atmosphere, with many people dancing to a live DJ at the same time, all over the world.

Figure 6.3:

stream for Boiler Room, March

Socially Distanced raves

On 26th August, 2020, Patrick Topping organised the UK’s first legally organised socially distanced dance event. Set up by Toppings own Trick label, the event took place at the Virgin Money Unity Arena in Newcastle (Figure 6.4). It was organised safely to perfection, with 2000 people set up in 6 person bubbles, and with a high quality sound-system and strobe lighting, the vibe was kept intact (Bennet, M, 2020).

In addition, festivals are following suit, such as Fly Open Air - an electronic dance music festival in Edinburgh. In the event of Coronavirus restrictions still being in place in Summer 2021, Fly have issued a Plan B solution, in which they will have a socially distanced crowd, yet still unified through the quality of music being played (Robb, E, 2020). Therefore, despite the restrictions that Coronavirus has to experiencing live dance music, there is still ways to work around it, whilst maintaining safety (Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.4: Patrick Topping at the UK’s first socially distanced rave in Newcastle (Google image altered by author)

Figure 6.5: Fly Open Airs Plan B (Google image altered by author)

Figure 6.6: The benefits of the “gig” economy (Authors own image)

The World Will Dance Again

The future is hard to predict, but as we enter the digital age, it is evident that there will be a social shift within all aspects of society. Underground dance music is no exception to that. Nevertheless, worldwide circumstances bring innovation and new ideas to civilisation. The pandemic is a time of reflection, and to re-build the world. (Guta, M, 2020).

Economic factors

The music industry is fundamental to the British economy (Figure 6.6). In 2019 alone, the music industry contributed £5.8 billion to the UK economy (Eede, C, 2020). However, due to the lack of support from the UK Government for the “gig” economy, the arts face an alarming hope of survival. In contrary to supporting the arts, the Government have brought forward an initiative “Rethink. Reskill. Reboot” (Figure 6.8).

Rishi Sunak, Chancellor of the Exchequer stated that "musicians and others in the arts should retrain and f ind other jobs.” Indeed, such comments and initiatives are a disgrace to the industries that maintain the culture of the country (Peat, J, 2020). Thus, the government’s attitude to the arts will put them on the wrong side of history – they just don’t know it yet.

Figure 6.7: The Lone Wolf (Google image altered by author)

Figure 6.8: “Rethink. Reskill. Reboot” (Google image altered by author)

Cuiltural factors

Although it is essential for the live music scene to return due to the economic benefits that it brings to the world, it will primarily restore itself because of its necessity to culture (Figure 6.9). Without culture, humankind is worthless. The economy is a social construct created by humans, that beyond our race, has no literal meaning. It is culture which creates spirit within our world (Henrich, J, 2011). Culture acts in many different ways. However, it can be worrying. It makes us feel as if we need to act in a certain way to f it into society (Cannon, J, 2016). Nevertheless, this can be challenged by thinking differently to what is considered as “the norm,” (Figure 6.7).

Along its journey, underground dance music has been a counter-culture to the standardised civilisation that our world has known. By

escaping into new forms of music within the depths of our cities, culture has developed across the world, creating new identities for the cities that they are discovered in. If we are fearful that the music industry will struggle to rediscover itself amidst a battle against an invisible virus, then I am worried for society. Ultimately, it is culture which will rescue music from the darkness of a global pandemic… even it means that we will be dancing around a fire (Figure 6.10).

Figure 6.9: THE WORLD WILL DANCE AGAIN (Authors own image)

Figure 6.10: Humankind dancing around a fire (Google image altered by author)

Final Thoughts

Research Outputs

This paper set out to find out how important underground dance music is to the postindustrial city, understand the extent to which Covid-19 has had an impact on our cities’ identity, and reflect on how as a society we can recover in a post-pandemic world through music and culture.

Initially, it unravelled a background of the subject, gauging firstly how music engages with culture, architecture and technology, and then consulting the evolution of dance music from Disco, into House, into Techno. This then led onto asking three primary research questions, being how does underground dance music relate with escapism from society, create a community for counter-cultures, and establish the identity of a city?

To answer these questions into detail, both primary and secondary research was carried out. Secondary research was established in the form of a literature review, in which existing information produced a theoretical framework of

escapism’ to everyday realities. Primary research then critiqued my own experience of living in new cities that have an emphasis on underground music.

Once a theoretical framework was created, three case studies were undertaken, looking at how Techno relates to the post-industrial city into detail. By researching the history of underground dance music within Detroit, Berlin and Glasgow, it was made clear through the connections made between the three cities, that there was a common theme - each of these cities experienced the disorder of post-industrial change, but bounced back through the character of their underground communities through electronic dance music.

Finally, research looked into ways solutions underground communities have been making to continue live music through throughout the current pandemic, and reflected on how once the pandemic is a distant memory, that live music will un-pause, partly due to the economy,

Figure 7.1: The Glasgow Barrowlands (Google image altered by author)

Limitations

Just as Covid-19 has constrained live music, so too did it limit the research in which I was able to pursue within this dissertation. The University Architecture Library being closed was a barrier to investigations with my topics. Furthermore, primary research was limited in how I had to use past experiences rather than new experiences

within nightlife to determine how important underground music is to the modern city.

Finally, the restrictions that responded to Covid-19 as I undertook research and wrote this thesis was harmful to my work flow, as I was deprived from my familiar routine of exercise, social work-space and escapism through music.

Further research

The subject of music influencing a cities’ cultural identity is an ever-growing evolution. It will be interesting to discover exactly how the music industry rebuilds itself following the Covid-19 Pandemic. Technology is a permanently expanding aspect of human civilisation.

With the Coronavirus era bringing a time of reflection and innovation to the world, it will be intriguing to witness how new ideas develop music within this generation. Thus, there is scope for extended research into how the world rebuilds itself, and how music and culture will be at the heart of a new era in humankind.

Figure 7.2:

A sea of dancers side by side (Google image altered by author)

Bibliography

References

Figures

All figures are authors own unless stated otherwise.

References

- A, Arblaster, (2002): Self-Identity and National Identity in Classical Music. (Online) Research Gate. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/293590551_Selfidentity_and_national_identity_in_classical_music

- Bain, K, (2020): Beatport Announces 24-Hour Live Stream (Online) Billboard. Available at https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/dance/9340792/beatportannounces-24-hour-live-stream-with-rufus-du-sol-carl-cox-more-exclusive

- Beattie, A, (2018): Tresor - A History of Berlins Iconic Music Venues 002. (Online) Love From Berlin. Available at http://www.lovefromberlin.net/tresor-a-history-of-berlinsiconic-music-venues/

- Bennet, M, (2020): ReviewL: Patrick Topping at the UK’s First Socially Distanced Dance Event. (Online) Mixmag. Available at https://mixmag.net/feature/patrick-topping-jaguar-sally-c-newcastleclubbing-arena-review

- Brian, S, (2019): 1989: How Reunified Berlin Birthed a Club Culture Revolution. (Online) Made For Minds. Available at https://www.dw.com/en/1989-how-reunified-berlin-birthed-aclub-culture-revolution/a-51017498

- Brocklehurst, S, (2013): Govan: A Shipbuilding History. (Online) BBC. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-24820573

- Bryce, J, (2020): ‘It’s Like The Prohibition Era Again.’ (Online) The Press and Journal. Available at https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/lifestyle/food-anddrink/2548393/its-like-the-prohibition-era-again-dismay-as-pubs-and-restaurants-are-banned-fromselling-alcohol-and-told-to-close-indoors-at-6pm/

- Cannon, J, (2016). We All Want to Fit In (Online) Psychology Today. Available at https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brainstorm/ 201607/we-all-want-fit-in

- Carlos, L (2019): The Myth of Berghain: The Berlin Underground. (Online) Offramp. Available at https://offramp.sciarc.edu/articles/the-myth-of-berghain-the-berlinunderground

- Chambers, D, (2018): The Blindboy Podcast - Episode 34 (06/06/2018): Devitos Teapot. (Podcast). Available at Spotify.

- Chester, J, (2015): Why Glasgow’s Iconic Barrowland Ballroom Continues to be the Go-To Venue for Touring Artists.

(Online) The Daily Mail. Available at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/travel/article-2881858/WhyGlasgow-s-Barrowland-Ballroom-continues-venue-touring-artists.html

- Collin, M, (2018): Rave On - Global Adventures in Electronic Dance Music. (Novel) Available at Waterstones Bookshop.

- Constable, H, (2020): How Do You Build a City for a Pandemic. (Online) BBC Future. Available at https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200424-how-do-you-build-acity-for-a-pandemic

- Cowen, &, (2018): The Symphony Orchestra and the Industrial Revolution. (Online) Marginal Revolution. Available at https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/ 2018/04/symphony-orchestra-industrial-revolution.html

- Doward, J, (2018): Has it all gone Pete Tong for electronic dance music? (Online) The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/may/27/electronicdance-music-edm-has-it-all-gone-pete-tong-sales-plateau

- Eede, C, (2020): Music Industry Contributed £5.8 Billion to UK Economy in 2019. (Online) DJ Mag. Available at https://djmag.com/news/music-industry-contributed-58-billion-ukeconomy-2019

- Gardner, L, (2015): The Closure Of The Arches Will Be Felt Around The World. (Online) The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/stage/theatreblog/2015/jun/10/ arches-glasgow-theatre-closure

- Glazer, J, (2014): Craving the Rave - Detroit’s Electronic Music Scene in the 90’s. (Online) Red Bull Academy. Available at https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2014/05/detroitelectronic-music-scene-in-the-90s

- Glynn, P, (2019): Berlin Wall - Germany was First Reunited on the Dance Floor. (Online) BBC. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-49892553

- Grogan, S, (2020): “From Saturday Night Fever to Monday morning hangover: why did the world turn on the Bee Gees?”

(Online) The Telegraph. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/music/artists/saturday-night-fevermonday-morning-hangover-did-world-turn/

- Guta, M, (2020): How Epidemics Spur Innovation. (Online) Small Business Trends. Available at https://smallbiztrends.com/2020/04/innovations-duringepidemics.html

- Hasnain, Z, (2017): How the Roland TR-808 Revolutionised Music. (Online) The Verge. Available at https://www.theverge.com/2017/4/3/15162488/roland-tr-808-musicdrum-machine-revolutionized-music

- Henrich, J, (2011): A cultural species: How culture drove human evolution. (Online) American Psychological Association. Available at https://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/ 2011/11/human-evolution

- Herzog, K, (2014): 24 Inventions That Changed Music. (Online) Rolling Stone. Available at https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-lists/24-inventionsthat-changed-music-16471/

- Hinton, P, (2020): Sub Club Launches Crowdfund To Save Itself From Permanent Closure. (Online) Mixmag. Available at https://mixmag.net/read/save-our-sub-club-glasgow-crowdfund-news

- History, (2009): Berlin Wall. (Online) History. Available at https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/berlin-wall

- Jencks, C, (2013): Architecture Becomes Music. (Online) The Architectural Review. Available at https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/ architecture-becomes-music

- Jenkins, D, (2020): Out of the melting pot: The origins and evolution of drum’n'bass (Online) Red Bull. Available at https://www.redbull.com/gb-en/history-of-drum-and-bass-music

- Jukely, T, (2018): Is it House? Or is it Trance? A Beginner’s Guide to Electronic Music Genres. (Online) Four Over Four. Available at https://www.fouroverfour.jukely.com/culture/electronic-musicgenres/

- Kimutai, K, (2017): What Was Disco Dance Music, and Where Did it Begin? (Online) World Atlas. Available at https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-was-disco-dance-musicand-where-did-it-begin.html

- Kirby, D, (2018): Old ravers are wanted to tell the story of the iconic 1980s Manchester acid house dance scene (Online) I News. Available at https://inews.co.uk/culture/music/manchester-northern-england-acidhouse-dance-music-madchester-216443

- Koh, V, (2017): The Psychology Behind Why We Enjoy Clubbing. (Online) Campus. Available at https://www.campus.sg/the-psychology-behind-why-we-enjoyclubbing/

- Kronenburg, R, (2012): Live Architecture - Venues, Stages and Arenas for Popular Music. (Novel) Research Gate. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 295126200_Live_architecture_Venues_stages_and_arenas_for_popular_music

- Kronenburg, R, (2019): This Must Be The Place. (Novel) Available at Bloomsbury.

- Lee, S, (2018): This Is The Story of a Techno Revolution. (Online) Red Bull. Available at https://www.redbull.com/gb-en/quickfire-history-of-detroit-techno

- Leight,E, (2016): 8 Ways in Which the 808 Drum Machine Changed Pop Music. (Online) Rolling Stone. Available at https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/8-waysthe-808-drum-machine-changed-pop-music-249148/

- Lorenzo, I, (2019): The Stonewall Uprising: 50 Years of LGBT History. (Online) Stonewall. Available at https://www.stonewall.org.uk/about-us/news/stonewall-uprising-50years-lgbt-history

- Maddison Moore, (2015): This is Why Cities Need Nightlife. (Online) Thought Catalouge. Available at https://thoughtcatalog.com/madison-moore/2015/07/thisis-why-cities-need-nightlife/

- Martynov, R, (2010): Tresor, Berlin - The Techno Club That Made History. (Online) Epic Productions. Available at http://www.damnthatsepic.com/dte-blog/tresorberlin-thetechno-club-that-made-history

- McCartney, W, (2019): How the Fall of the Berlin Wall Forged and Anarchic Techno Scene. (Online) Mixmag. Available at https://mixmag.net/feature/30-years-since-the-fall-of-the-berlin-wallanarchic-techno-scene

- McDaniels, R, (2020): DJ’ing through the pandemic: How the Electronic Dance Community is Leading the Industry into Livestreaming. (Online) Music Business Worldwide. Available at https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/djingthrough-the-pandemic-how-the-electronic-dance-community-is-leading-the-industry-into-livestreaming/

- McDonald, K, (2011): Clubbing in Glasgow. (Online) Resident Advisor. Available at https://www.residentadvisor.net/features/1377

- Moss, M, (2004): The Glasgow Story - Industry and Technology. (Online) The Glasgow Story. Available at https://www.theglasgowstory.com/story/?id=TGSFE

- Mullin, F, (2014): How UK Ravers Raged Against the Ban (Online) Vice. Available at https://www.vice.com/en/article/vd8gbj/anti-rave-act-protests-20thanniversary-204

- Omri (2019): Short History of Techno in Berlin. (Online) Techno Station. Available at https://www.technostation.tv/short-history-of-techno-in-berlin/

- Orlov, P, (2018): How Underground Resistance Became the Public Enemy of Techno. (Online) Vulture. Available at https://www.vulture.com/2018/10/how-underground-resistancebecame-the-public-enemy-of-techno.html

- Palladev, G, (2015): Detroit Techno. (Online) 12” Edit. Available at https://12edit.com/detroit-techno/

- Peat, J, (2020): Government’s ‘rethink reskill reboot’ campaign sparks outrage. (Online) The London Economic. Available at https://www.thelondoneconomic.com/politics/ governments-rethink-reskill-reboot-campaign-sparks-outrage/12/10/

- Peter, B, (2018): Berlin Wall: How Techno Music United Germany on the Dance Floor. (Online) The Conversation. Available at https://theconversation.com/berlin-wall-how-techno-musicunited-germany-on-the-dance-floor-125280

- Petridis, A, (2019): Disco Demolition: the night they tried to crush black music. (Online) The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/jul/19/discodemolition-the-night-they-tried-to-crush-black-music

- Poelti, A, (2016): Berghain: Berlin’s Mysterious Techno Temple. (Online) Culture Trip. Available at https://theculturetrip.com/europe/germany/articles/berghainberlins-mysterious-techno-temple/

- Pollock, D, (2020): Why a Tabloid Storm Won’t Crush Glasgows Famous ‘After’s’ Scene (Online) Mixmag. Available at https://mixmag.net/feature/glasgow-checkmate-afters-scene-weshould-hang-out-more-tabloid-scotland

- Ravens, C, (2020): The Gig-less Economy - What Could a Post-Pandemic Dance Music Scene Look Like. (Online) Mixmag. Available at https://djmag.com/longreads/gig-less-economy-what-could-postpandemic-dance-music-scene-look

- Richardson, A, (2006): History Of The Arches (Online) The List. Available at https://www.list.co.uk/article/189-history-of-the-arches/

- Robb, E, (2020): Fly Open Air 2021 is Happening, With Potentially Major Social Distancing. (Online) The Edinburgh Tab. Available at https://mixmag.net/feature/patrick-topping-jaguar-sally-cnewcastle-clubbing-arena-review.

- Salamon, M, (2013): 11 Interesting Effects of Oxytocin. (Online) Live Science. Available at https://www.livescience.com/35219-11-effects-of-oxytocin.html

- Sicko, D, (2010): Techno Rebels - The Renegades of Electronic Funk. (Novel) Research Gate. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 297082456_Techno_rebels_The_renegades_of_electronic_funk

- Simms, S, (2017): The Belleville Three & How Techno Was Born (Online) Ask Audio. Available at https://ask.audio/articles/the-belleville-three-how-techno-was-born

- Shapiro, P, (2000): Modulations - A History of Electronic Music. (Novel) ABE Books. Available at https://www.abebooks.co.uk/Modulations-History-Electronic-MusicThrobbing-Words/30339984145/bd

- Shula, A, (2019): The Importance of Music - Why and When we Listen to Music. (Online) Cognition Today. Available at https://cognitiontoday.com/the-importance-of-music-whenand-why-we-listen-to-music/

- Smith, J, (2016): What Ever Happened to Love Parade. (Online) Stoney Roads. Available at http://stoneyroads.com/2016/12/what-ever-happened-to-loveparade/

- Soma, (2020): Slam. (Online) Soma Records. Available at https://www.somarecords.com/artists/slam/

- Stewart, J, (2019): Timeline: Music Is About Venue (Online) VPR. Available at https://www.vpr.org/post/timeline-music-about-venue#stream/0

- Sweney, M, (2020): 170,000 jobs in UK's live music sector 'will be lost by Christmas’ (Online) The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/oct/21/jobs-uk-livemusic-industry-lost-decline-revenues-covid

- The Newsroom, (2016): Everything You Need to Know About Clyde Shipbuilding. (Online) The Scotsman. Available at https://www.scotsman.com/whats-on/arts-and-entertainment/ everything-you-need-know-about-clyde-shipbuilding-1479789

- Thomas, B, (2017): ‘Be The Maddest One In The Room’: How To Make A Nightclub Last For 30 Years. (Online) The Guardian. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/aug/22/30-years-subclub-nightclub-glasgow

- Warwick, O, (2019): What is house music? A brief history of the eternally relevant club genre. (Online) Red Bull. Available at https://www.redbull.com/gb-en/house-music-FAQ

- William, C, (2020): Incredible Memories of the Arches from a Former Manager of Glasgows Iconic Nightclub. (Online) Glasgow Live. Available at https://www.glasgowlive.co.uk/news/history/the-arches-glasgowclub-nightclub-18331951

- Whitney, K, (2019): Why Glasgow is Britain’s Best City for Music Lovers. (Online) The Guardian. Available athttps://www.theguardian.com/travel/2019/nov/17/why-glasgow-isbritain-best-city-for-music-lovers

- Wurnell, M (2016): The Berghain Backstory: Building Berlin’s Most Legendary Nightclub. (Online) Cuepoint. Available at https://medium.com/cuepoint/the-berghain-backstory-buildingberlins-most-legendary-nightclub-87ad2d901ee9

- Wo, E, (2018): The Golden Years - Detroit Techno’s Warehouse Scene. (Online) Maekan. Available at https://maekan.com/article/the-golden-years-detroit-technoswarehouse-scene/

- Vasconcelos, A, (2019): freedom: the Berlin Wall, thirty years on (Online) Open Democracy. Available at https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/ fragile-lightness-freedom-berlin-wall-thirty-years/