By Alwyn Dow

My Experiences in East Africa

Rudyard Kipling’s 1899 poem stressed the need to serve those whom Empire took under its wing.

So where did it all go wrong? Maybe Rhodesia is a case in point. I was in the region and I supported the view of the British Government that there should be no independence for Rhodesia before majority rule (NIBMAR). This article is a respectful testament to those who lived and served in East and Southern Africa around those times.

The writing has been on the wall since the 1958 Accra Conference had signalled a shift in British attitudes on the part of Colonial Secretaries Alan Lennox-Boyd and Iain MacLeod whose views

were amplified two years later in Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s “Wind of Change” speech in Cape Town. Failure to secure UK approval for a white dominated legislature and all that went with it had, therefore, led to Ian Smith’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965. This in turn led to Rhodesian actions to prevent fuel supplies reaching landlocked Zambia, causing massive disruption to mining in the Copper Belt around Ndola and Kitwe. That’s where I came in.

But let’s go back a bit. My African adventure had begun somewhat earlier. If you had told me that the London Hospital’s six-a-side soccer tournament in 1959 would change my life, I would have laughed. Yet that turned out to be the case. Not only did I score the winning goal to win the Cup but I met my wife-to-be Judith, a nurse at the hospital. Her parents happened to work in Kenya. Three

years and three children later, we left the UK and made our way to a small town called Eldoret in the White Highland, north of Lakes Nakuru and Naivasha.

My employer was the International Forestal company, with interests in estate management and obtaining

tanning extract from wattle trees. Senior administrative staff positions were held by white Europeans and Afrikaaners. We all lived very comfortably in a securely gated enclosure reflecting the relatively recent Mau Mau crisis. The houses were roomy with the typical red corrugated roofs of the African interior. Anybody who was anybody had three domestic employees. Ours were Fatumah

(children’s Ayah), Ondago (house boy) and Stephen (gardener) and they seemed to get on well despite being from different tribes. To prove the point about racial unity, Jomo Kenyatta visited Eldoret that year and was given a warm welcome.

We did our best to integrate with the white community when racial suspicion and indeed superiority were still rife. When I nominated an Asian doctor and an African policeman to be admitted to the Round Table, the suggestion was regrettably greeted by two black balls (a rather appropriate gesture, one might say).

However the Table did very good work, carrying radio telephones into the deep hinterland. Despite my somewhat radical reputation, I joined the cricket and rifle clubs and, with Judith, the Uasin Gishu Dramatic Society. She appeared in lead roles wile I played jazz clarinet on occasions.

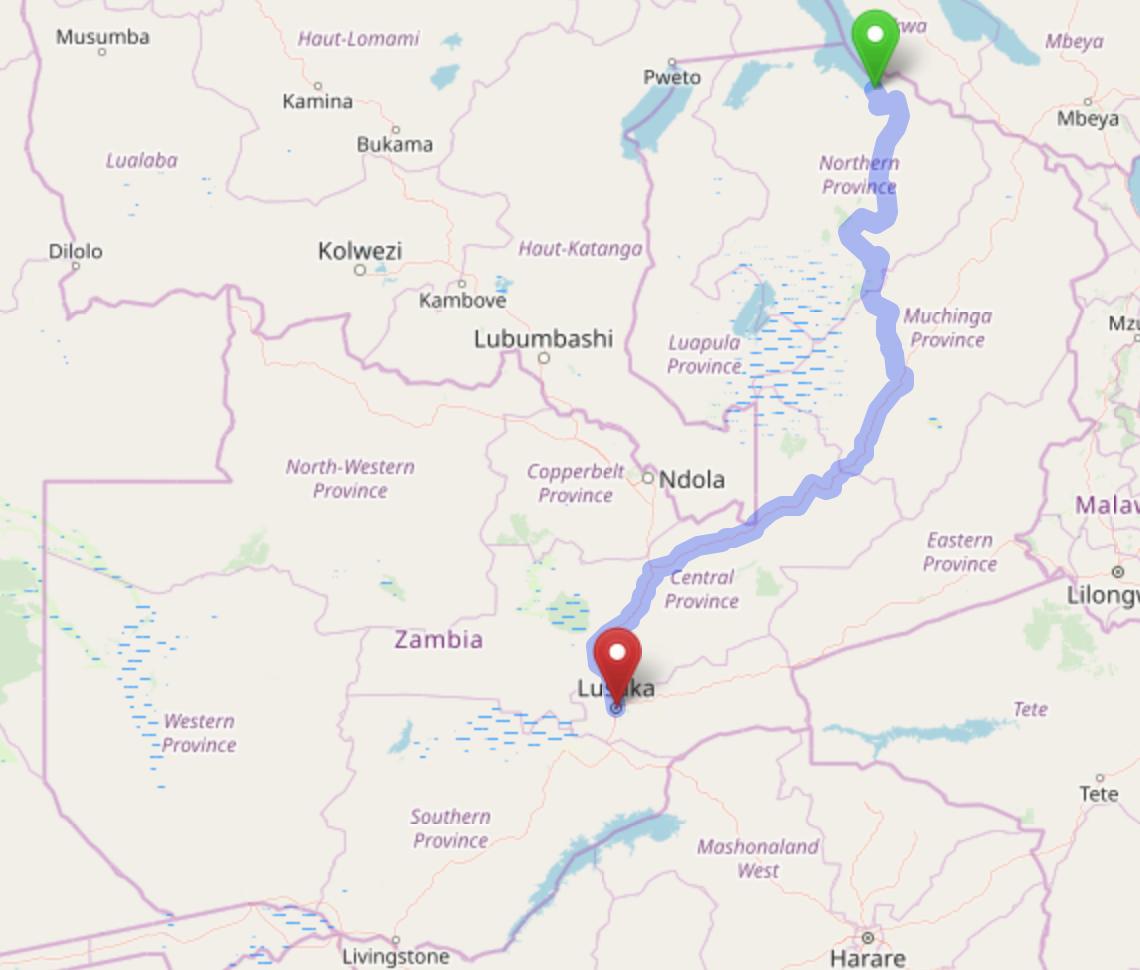

Great North Road of Zambia - ‘The Hell Run’ : Wikipedia

Tackling the Hell Run

In 1965, with our time in Kenya nearly up, I received a rather surprising offer.

We had heard of the drama unfolding in Southern Rhodesia but most people just got on with their lives, as we did. I was very

surprised, therefore, to receive an urgent message to come to Nairobi to meet with agents of DTD, the main Mercedes dealer in East Africa, to consider a matter “to my advantage”.

At the palatial Mercedes HQ I met the directors and financial comptroller. I was told that DTD were in a consortium with others in Tanzania to deliver oil to the Copper Belt from Dar Es Salaam. To do so, trucks would drive as best they could along a dirt track of around 1,000 miles. The consortium needed a chief accountant / administrator and I had been recommended by the Mercedes Benz dealers in Eldoret with whom I was on friendly terms.

Getting oil to the Zambian copper belt: Mr Dow sets off to administer it.

Would I like the job?

What? Had I heard correctly? Well, apparently I had because terms were laid out there and then, a double salary, school fees, a beach house at nearby Bagomoya and a sparkling Mercedes 220SE as my company car. It was an offer I couldn’t refuse. The job details were sketchy at that early stage but “in for a penny in for a pound”. I accepted and we were soon on the move to Dar Es Salaam.

On arrival in Dar, I met DTD’s consortium partner, a charismatic Greek Sisal farmer called Andreas Cretan, and Paul Rodriguez, Director at the Petroleum Finance Board (PFB) with whom we were to do business. Initially, we had twenty-five 618 MB trucks, another twenty-five MB 2620s, Cretan’s own 20 and another 50 or so, sub-contracted from Arab and African traders. Most were converted farm trucks, resplendent in our red and white livery. We had a spotter plane to cover the route and six Datsun pick-ups to patrol it day and night.

We were not the only kids on the block as international vested interests vied with commercial ones to do the business. Agip (Italian Petroleum) were there with a large fleet of Fiats, as were other nations, including Aeroflot from Russia with feet firmly on the ground. The Chinese were there, as was to be expected from

such a strong ally of President Nyerere of Tanzania. Sundry other trucks represented an international potpourri of nations.

Copper Belt & Kariba

I visited Lusaka, Ndola and Kitwe as well as Victoria Falls and the Kariba Dam. I saw evidence of Rhodesian Air Force tracer shells that had been used on villages near the border as well as overturned trucks that had been strafed from the air. I was not encouraged to spend much timein Salisbury (Harare), not least

because the prospect of unwelcome attention from the Police Reserve and Intelligence Corps.

I took trips in our spotter plane and as co-driver on forays up country through Iringa, Dodoma and other towns on the route. It was never pleasant as the “murram” track seemed to be too dusty or too wet. Accidents were frequent and I witnessed a number of overturned trucks.

Rodriguez had been only too happy to accept our terms in the early stages and didn’t ask too many questions about our reliability and trustworthiness. With hindsight, I should perhaps

have done so in the light of bogus insurance claims. My naïve belief had been that an accident was an accident, and that lost oil cargo was covered by insurance.

However, an investigation by the PFB revealed wholesale fraud as truck drivers, including some of ours, sold the so-called accident losses on the market. DTD in Nairobi was not at all happy. Fortunately, a pipeline and railway were under construction so the days of the “Hell Run” were numbered. I finished working for the Consortium in 1967 and returned with the family to dear old Blighty.

Polite to a Fault

I met Nyerere, Kaunda (Zambia’s President, and Mugabe but not Nkomo. They all favoured the

high collar Chinese style of dress and were polite to a fault in my meetings with them.

This brings me to the crisis for the white settlers after the 13-year Zimbabwe War of Liberation. I have discussed this matter at some length with a Rhodesian veteran. In my view, the war was fought for independence and land distribution but it was not a war of African making. If there were culprits, I would blame the old Colonial “Scramble for Africa” that left white minorities in charge of the welfare of millions of Africans.

UK Prime Minister Harold Wilson put his foot down eventually but offered no substantial compensation to farmers. Nor, apparently, did the Zimbabwe Government. I hope the farmers recognise that individual excesses were not as a result of Mugabe policies but the failure of British ones over a very long period in which Kipling’s concept of a “white man’s burden” of service was laid aside for political expediency and commercial gain.