Philipp Zitzlsperger

Design’s Dilemma between Art and Problem-Solving

Birkhäuser

Basel

Philipp Zitzlsperger

Birkhäuser

Basel

‘You cannot brush your teeth with art’,1 declared Dutch Dadaist Theo van Doesburg (1923), and his rallying cry is almost impossible to refute. At least in the European cultural sphere, society is calibrated so that art is detached from everyday life and cannot be an object of use. Art demands distance and contemplation. Design, by contrast, is all about application, use, consumption. Exponents of both design and art have tended to acquiesce in this supposedly incontrovertible distinction, and by doing so have drawn a cognitive and institutional dividing line between their respective disciplines. While critics such as Gottfried Semper raised objections as early as the nineteenth century and the avant-gardes of the 1910s and 1920s were fervent champions of art in everyday life, ultimately it was the mentality behind van Doesburg’s aphorism that won the day. And although there are countless examples of the design-art synthesis even today,2 they are powerless in the face of this culture of segregation, which is also the cause of today’s profoundly conformist, efficient and solution-based design. This book attempts to reconstruct the history of this parting of the ways. To do this will entail revisiting those momentous decisions on the part of individuals or institutions (academies, business enterprises, and such like) that over the centuries have (up) set the balance in the relationship between art and design. This review of design’s ‘Ideen- und Problemgeschichte ’, that is, of the history of ideas and of the historical problem posed by design and art,3 will also enable us to look forwards. Yet if deconstructing the myths and narratives of design history opens up scope for what is actually the ur-concern of design, the design-art synthesis, the perspective is bound to differ from those adopted hitherto. The book can therefore be read as a plea for a rather different rapprochement of design and art and for an approach that may enable their respective protagonists to take a different ‘Haltung ’ or attitude, even in an age of market conformity and solutionism. The book does indeed recall the past unity of design and art, and hence is indeed a reminder of how design grew out of art. But what it does not do is wistfully hark back to some Golden Age of arts and crafts or the romanticism of the early Bauhaus, while deliberately ignoring the realities of Western economic systems. On the contrary, to be worthwhile, any critical assessment of the constantly changing relationship between art and design has to be related not as a tale of progress, but rather as one of conflict and problems, in which rival claims to judgement and discernment were constantly vying for the upper hand. In the course of this process, moreover, the ideas of Vasari, Kant, Semper and Dewey on the origin of the aesthetics of design and art have been constantly reminted to the point of being rendered unrecognizable and translated into successful narratives. This kind of myth-making through the reduction of complexity is something we must familiarise ourselves with if, following a deconstructivist approach to cultural history, we are to arrive at a rather different design-art synthesis.

After all, the design dilemma of our times is the narrative of the design-art dichotomy. It also rests on a design-art antithesis, which is a construct as much of the system of design as it is of the system of art. The design-art dichotomy has long been part of the collective view that while ‘high art’ is to be revered, the ‘lower’ arts – the ‘servile arts’, that is – are to be consumed; that while the fine arts are autonomous, design is bound by economic factors. This narrative rests on myths that deracinated design from its artistic origins. There are myths that tell of heteronomous design as a product of industrialisation, as an adjunct of technical progress, as fit for serial production, as a

solution to a problem, whereas autonomous art is all about self-fulfilment, rebellion, critique. This explains design’s expulsion from the paradise of art, its ‘deartification’. These myths obscure our view of the true reasons for art and design’s parting of the ways and will therefore have to be deconstructed in what follows. For the deartification of design was caused not by materialistic constraints, but rather by the change in its aesthetics, which here is used to include aisthesis, the Old Greek term for perception and sensation. The deartification of design is thus a history of design aesthetics that not only has not yet been written, but that also exposes a hitherto disregarded strand of the history of ideas and the historical problem of design and art.

Telling it will require an analysis of some of those key conflicts of the past 600 years in which designers, architects, artists, philosophers, economists, sociologists, entrepreneurs and politicians searching for a way to advance the aestheticisation of life posited contradictory theories on the distinguishing characteristics of art, craftsmanship or design, on the peculiarities of autonomy, heteronomy or Kant’s ‘disinterested satisfaction’, and on the striving for normativity, diversity or innovation, on what it means to serve humanity, society or the market, on attitudes to politics, ecology or sustainability, and on matters of form, aesthetics and problem-solving – in short, those contradictory theories that in the course of history sparked controversy, and were either jettisoned or elevated to dogmas leading to the rational, problem-solving deartification of design. In a culture of solutionism, design is that non-art that invariably promises to solve problems. But in many areas of this history of design aesthetics, the question of how it came to that, and whether it was inevitable, remains unanswered.

The term ‘deartification’ is a deliberate borrowing from Theodor Adorno, who used the lexical parallels between ‘Entkunstung ’ and ‘Entartung ’ as a deliberate provocation. While the Nazis stigmatised modernist art as ‘entartet ’ (degenerate), Adorno’s ‘Entkunstung ’ was a reference to the ever-greater commercialisation of art after 1945, which, he argued, had destroyed the distance, the reflective space, between the work and the viewer.4 And now the talk is of the deartification of design, which implies that without art, design forfeits a supporting pillar of its true potential. Deartification is as much a concern of design theory as it is of design practice from the drawing to the finished artefact in that it conditions our thinking about design and the meaning of design between theory and practice. It also conditions the ‘Haltung’ – or attitude – taken by the individual designer. Despite the heroic and ideological connotations that ‘Haltung ’ has retained from the Nazis’ use of the term, it is so central to the language of design and architecture that it really is the mot juste here.5 Because what ‘Haltung ’ addresses is nothing less than the ideological formation of character, which even while still in training is under tremendous pressure to conform. The deartification of design is a key component of this norming. Pondering the deartification of design should therefore be deemed of the utmost relevance, since that is what determines the designer’s attitude.

Many designers have reconciled themselves to deartification; others actually see it as a necessity; and others still are not even aware of it. But there have also been repeated attempts to counter design’s deartification and win back its autonomy; for without artistic, critical self-awareness and independence there can be no scope for ethical design. To put it another way, adapting to the deartification of design is an attitude that makes a mockery of ethical considerations on matters such as sustainability. There are fashion designers, for example, who service an industry whose penchant for

fast fashion is responsible for 20 per cent of the world’s effluent and 5 per cent of its carbon emissions, to say nothing of the mountains of unwanted garments, 90 per cent of which were made by slave labour.6 Yet they all claim to be in favour of sustainability, even if nothing changes. While designers themselves are not to blame for this, they seem not to mind working for those who are, even voluntarily declaring themselves their service providers, as will be discussed in greater detail in what follows. This relationship of hierarchical dependency between designer and client, between design and industry, was made possible by the deartification of design. Yet none of the said attempts to counter it has yielded results; nor could they, since they all sought to tackle the symptoms and not the causes, which are rooted in design’s dilemma between art and problem-solving. The elucidation of this in the diachronic review that follows is intended to call to mind a state of affairs that has come to be taken for granted, and for this reason has slipped out of our purview. The story and circumstances of its emergence and of the great divergence of design and art have in part been lost to oblivion.

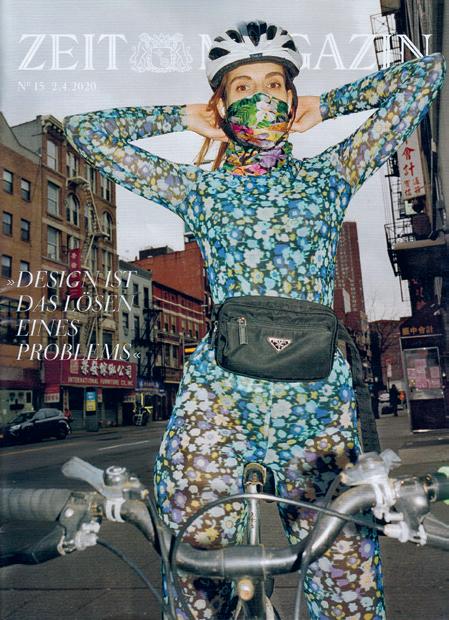

The narratives and myths that have arisen to fill the void emphasise the capacity of design – unlike art – to help people and solve problems. That is why design is considered social, functional and pragmatic. Design as a problem solver is probably one of modernity’s greatest myths. The mantra of problem-solving design recently featured on the title page of the German weekly ZEITmagazin (2.4.2020), which was blazoned with the headline ‘Design ist das Lösen eines Problems’ (Design is the solving of a problem) (fig. 1). That is a clear stance; and it once again confirms how closely design is tied to the mindset of the perennial utility imperative. Design has therefore become closely bound up with solutionism, which is the view that social problems can be redefined as technical problems and hence can be solved only with technical solutions.7 The close ties between the history of design and the history of industry and technology derives from the technophilia of solutionism, culminating in today’s Silicon Valley.

What tends to be forgotten, however, is that design has been in the grip of problem-solving euphoria only since the 1940s. Only since then has there been all this rapturous talk of the utilitarian avant-garde constantly setting off for new shores to create design utopias and gift the world its Bauhaus lamps, Frankfurt kitchens, Breuer chairs

and iPhones. Many of these success stories are shrouded in utilitarian and problem-solving myths. They accord the design discipline a useful place in society and invest designed products intended for consumption with a certain mystique. This has also been the target of most of the critique to date, which in essence is a critique of consumerism and capitalism8 and reveals a mindset that is itself reliant on the very same myths that cemented the idea of commerce as design’s dirty little secret. Design, according to this argument, is just a stepchild of capitalism concerned solely with prettification, decoration or even just plain old seduction; it is a tool of the profit motive and designers themselves mere service-providers; design is non-art. Not so long ago there were even calls to abolish design altogether on the grounds that it was too compliant and ‘obscured the true nature of the things to which it gave shape’,9 the implication being that art, by contrast, is free, critical and non-conformist.

As capitalism’s problem-solving, prettifying, socially responsible, sustainable, profit-oriented, commercialised, manipulative and controlling non-art, design is certainly a chimera, a weird hybrid which, depending on your values, can either be a blessing or spell ruin. Steering a course through such an accumulation of contradictions is difficult, given how arbitrarily the critique ranges between utility at one extreme and outright harm at the other. The way out of this labyrinth of value judgements presented in what follows is a diachronic review of the origins of the various narratives and myths and the ideas from which they sprang before becoming set in stone as the design dilemma. This reconstruction of their origins, which in some instances date back centuries, will recall those past conflicts through which the contours that design and art now have were negotiated. The history of these conflicts can sharpen our awareness that design’s hybrid state is not necessarily the result of progress, but should rather be viewed as the inevitable consequence of conflicts being resolved by certain ideas winning out over others. That is by no means a trivial matter, considering that the history of functionalism is inextricably interwoven with a rather crude variant of Darwinism that wantonly disregards one key aspect of Darwin’s theory of evolution. Had this not been forgotten, the critique of functionalism, design aesthetics and consumerism that first took hold in the 1960s would probably have taken a very different course.

As recent scholarship shows, design critique has become reliant on two distinct lines of attack: (1) critique of design aesthetics, here meaning not prettification but sensory perception, and (2) critique of consumerism and capitalism. This two-pronged approach to design critique, which on the one hand is aesthetic and on the other economic, has nevertheless become imbalanced, in that while the former has only just started, the latter already has a 150-year-old tradition to draw on. William Morris, Thorstein Veblen, Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Jean Baudrillard, Wolfgang Fritz Haug and Gert Selle are among the greats to have addressed design’s complicity in consumerism and capitalism, in some cases tarnishing design’s reputation in the process. Design critique concerned solely with aesthetics, by comparison, has so far received short shrift. Once Andreas Dorschel’s Ästhetik des Brauchbaren (2002) had staked out the desideratum, Annette Geiger picked up the thread in her Andermöglichsein des Designs (2018), which recalls the aesthetics of design beyond all economic and functional constraints. Daniel Feige’s recent studies on the philosophy of design are concerned with the design aesthetics of the functional. Finally, the debate has also been

informed by philosophical investigations into figures at the interface of art and design.10 Irrespective of which perspective one is inclined to share, it was high time design aesthetics re-entered our purview, given that aesthetic theory since Hegel has focused mainly on art, excluding the ‘servile’ arts.11

To broaden design’s aesthetic horizon still further, we will have to examine what exactly happens to the perception and appreciation of artefacts when, as in the eighteenth century, the hierarchy of the human senses is re-ordered and the sense of touch that has hitherto been held in high esteem is collectively downgraded. Given that most design artefacts are objects of use (applied arts) and hence are intended to be touched and held, design’s reception aesthetics is bound to change dramatically in such a case.12 And the changed relationship between design and art brought about by the reversal of proximity and distance, of touching and seeing, in turn changes the societal and economic role of design and with it the course of industrialisation and even many a far-reaching judicial ruling. This shift in the hierarchy of the senses is just as much part of the history of aesthetic conflicts as is the aforementioned emergence of functionalism out of Darwinism. Both were hotly contested issues at the time. The reconstruction of these conflicts – how they were thrashed out and the arguments, ideas and theories of those on each side of the debate – is not a history of the victors alone, since it also acknowledges the losers and the many sound arguments that they had. In countless cases, the stance of the losers in the conflict has been forgotten, and unjustifiably so, since today it may provide guidance, as long as its problematic history is faced.13

Admittedly, both ‘design’ and ‘art’ are woolly concepts. They are all but impossible to grasp, and their complex definitions vary greatly, depending on the social or professional group doing the defining and the value system being applied. Design and art remain controversial concepts and this book makes no attempt to change that. The focus will rather be on key definitions of two creative disciplines, from whose semantic overlaps both points in common and points of difference can be extrapolated. Any account of the historical problem of design and art is bound to be a history of their divorce, of the design-art dichotomy, since the two disciplines were originally very close, and only much later, above all in the Modern Era as of 1800, drifted apart – quite literally so, given that it was then that art came to be placed on a pedestal in museums, far removed from utilitarian design. But whereas design turned into a chimera, and still lurches between usefulness and harmfulness even today, art, especially since the Enlightenment, has acquired both an ever-clearer direction as well as the autonomy of a ‘fenced-in high culture’. Absolved of any kind of serviceability whatsoever, its greatest good is freedom, the same freedom that is enshrined in today’s democratic constitutions. This is how three key characteristics traditionally ascribed to art, specifically autonomy, rebelliousness and openness, came to have such grave consequences for design’s self-image. Art’s claim to autonomy addresses the conceptual freedom of the artist, which can be traced back to the aesthetic theories of Kant and Hegel. Yet the conceptual purposelessness of art is also part of its autonomy – the fact that, as noted above, one cannot clean one’s teeth with it. Art’s rebelliousness is its claim to constant experimentation: art as daring, confounding, shattering or eye-opening, art as a remaking of the world. Art does not seek to be affirmative but rather to shake viewers out of their ideological certainties. As for openness, according to Umberto Eco’s Opera Aperta (1962), the open work of art is open to interpretation and derives its meaning

and its subjective pluralism only through the viewer, and hence quite independently of the artist.

These three pillars of the definition of art have arisen in the past 250 years and have developed into the very antithesis of design: the autonomy of art as opposed to the heteronomy of design, the rebelliousness of art as opposed to the compliance of affirmative design, and art’s openness to interpretation as opposed to the obvious, trivial and purely decorative character of design. These contrasts are summed up by the concept of the design-art dichotomy, which describes how each of art’s three ideals in turn took its leave of the design cosmos. If this development seems inevitable when viewed from today’s perspective, then only because the history of the competing ideas and of the problems they posed has been forgotten and a materialistic, evolutionary account inserted in its place. According to this version of what happened, design is a child of industrialisation which craves returns, not art, and whose machines were ostensibly destroyers of art. This is the linear and evolutionary version of the history of design: a tale of adaptation to extraneous, technical circumstances. What it conceals, however, is the eventful, non-linear, cultural history of the competing ideas and the problems they threw up. It is this forgetfulness of history that makes the design dilemma invisible.

Yet a diachronic elucidation of this Problemgeschichte, this historical problem, soon reveals that what is supposedly a history written by the victors is in fact the work of dwarves standing on the shoulders of giants. The dwarves can see into the future, but only because they are held aloft by the giants, whose strength is nourished by discourse, by the struggle to make sense of the world, of life, of religion, of nature – and indeed of the arts and design. Many dwarves, however, forget the giants supporting them, and many are even self-professed patricides, who repudiate their predecessors, just as the Renaissance dismissed the ‘Dark Ages’ that it might shine all the brighter, and the avant-garde of the 1920s history itself.14 But when dwarves try to airbrush out those on whose shoulders they are standing, they are basically contributing to the formation of a myth. They are inhabiting a present without any history at all, which to them comes across as normality, as the natural state of affairs. The way mythologies transform the historicity of the present into an innocuous matter of course is something Roland Barthes drew attention to in his eponymous book of 1957, noting that it leads to things that are actually a product of history being mistaken for ‘naturalness’.15 Mythologies, Barthes argues, obscure the historical problem underlying them, reducing it to normality – and blinding the dwarves.

Barthes’s ‘mythologies’ should be broadened to include the design-art dichotomy, which has since mutated into a design-art antithesis. Its mythologies embed themselves in everyday aesthetics, eventually becoming an unquestioned matter of course that leaves its stamp on the attitude taken by designers and architects, and even on German legislation; for whereas the intellectual property rights to a work of art (copyright) endure for seventy years after the artist’s death, those to a design artefact (registered design, since 2014) last no longer than twenty-five years after the creation of the prototype. The ‘individual creativity’ of German design law is evidently deemed a much lower bar than the ‘artistic originality’ of copyright law. The first copyright law for artists, the Neue Kunstschutzgesetz of 1907, by contrast, protected art and design equally, without differentiating between the two.16 Between 1907 and the present,

however, the relative value attached to design and art has evidently undergone a dramatic shift to the detriment of the design discipline. While the history of jurisprudence may offer some justification for this development, the perception of today’s hierarchical view of art and design as ‘normal’ and the lack of awareness that it used to be quite different are definitely problematic.

Mythogenesis is a cultural technique that gives societies orientation, legitimacy and stability. Myths rest on past facts that have undergone interpretive sublimation. This necessitates a reduction in complexity, which not only allows a highly complex reality to be processed but also gives that reality meaning.17 This is how political, religious and scientific myths come about – and stardom, too. Nowhere is the life of society entirely free of myths. They offer cohesion where rationality fragments, which is why they are above all a phenomenon of the modern era that began around 1800.18 And because myths forge unity within and project distinctiveness without, societal groupings depend on them for their very existence. The design system and art system are likewise characterised by adaptation and distinction, especially when they are in competition, as we shall see in what follows. In this commemorative cosmos, the development of the design-art dichotomy can be viewed as continuous myth-making dating back to the Late Middle Ages.

The chapters that follow will reconstruct the myth-making that has happened in art, industry and Pragmatism, taking their cues from these methodological and historical considerations. Among the causes of the ostensible idealism of art (Chap. 1) is the hitherto disregarded aesthetic category of changing hierarchies of the senses, which was touched on above. Around 1800 the sense of touch clearly suffered a setback and with it a demotion that downgraded design but elevated art. The idealism of art also concerns Kant’s notion of aesthetic autonomy, the definition of which would later be narrowed to allow art to be styled autonomous, as opposed to heteronomous design. One problem of the philosophical history of art, moreover, is the different value attached to abstraction and imitation, which dogged both design and architecture from the Early Modern Age onwards, eventually leading to the great divergence of design and art. Its slow unfolding culminating in the design-art dichotomy can likewise be traced back to the Early Modern Age and the separation of art and craft.

Among the industrial causes of the design-art dichotomy (Chap. 2) are the introduction of typologies and norms and mass critique. The hegemony of standard forms that was an inevitable consequence of the growing need for norms in the industrialised design process in 1914 sparked a dispute between Hermann Muthesius and Henry van de Velde that came to be known as the ‘Typenstreit ’ (typology dispute). Many designers and architects resisted the standardisation of forms but were powerless to stop it. On the contrary, the last 150 years have seen a steady rise in the pressure to standardise with the result that there has been a drastic decline in design diversity. From the point of view of design aesthetics, this is remarkable, in that consumer societies are now living in a normed culture of their own choosing, while at the same time indulging a yearning for diversity.19 The origin of this paradox is probably to be sought in the 1930s, when hitherto positively connoted mass production came to be equated with loss of quality and specialness. Three publications that had a significant influence on this paradigm shift were Nikolaus Pevsner’s Pioneers of Modern Design (1936), Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1936) and Max Hork-

heimer and Theodor Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944), each of which in its own particular way advanced the design-art dichotomy by positing a qualitative difference between the series and the one-off, between design and art.

The pragmatistic causes (Chap. 3) should not be confused with pragmatism in the everyday sense. Rather, it was the American philosophy of Pragmatism around 1900 that became a key factor in the problem-solving thrust of contemporary design. The three principal causes of problem-solving design can therefore be enumerated as follows:20 (1) Certain branches of technology and engineering reinforced modernity’s deterministic thinking and this gave rise to a technical bias in ‘design thinking’ with a focus on physical and mechanical problems that might be solved technically. (2) The reception of Darwinism in the late nineteenth century sparked a functionalist approach to design which is still alive and well today and whose solutionist thinking likewise casts design in the role of problem solver. (3) The technical bias and functionalism of design were cemented by American Pragmatism, whose reduction of complexity led from pragmatism to pragmatic, problem-solving designs. Architecture, incidentally, suffered much the same fate, which is why design and architecture will frequently figure as affiliates in the discussion of the great divergence that follows.

The problem with problem-solving design is not that designers wish to solve problems but rather its fixation on technical, economic and socially responsible solutions that are geared exclusively to the present. A fixation on problems is by definition a fixation on the present and offers little scope for a design aesthetics that is reliant on historical consciousness. A practical design aesthetics would rest on comparisons with the history of form, style and reception from which to identify ‘the regularity and order that become apparent in artistic phenomena during the creative process of becoming and to deduce from that the general principles, the fundamentals of an empirical theory of art’,21 as Gottfried Semper put it in his historical justification for practical aesthetics. Whether sensory perception is viewed as psychological, anthropological, cognitive, subjectively personal or societal, it is never exclusively of the present, but always bears the stamp of historical factors and is always part of the collective memory. The ‘regularity and order’ governing aesthetics arise out of their historicity, which extends to all areas of their practical application and reception.

The presentism of problem-solving design, by contrast, is susceptible to myth-making. The propensity to mythogenesis in art, industry and Pragmatism altogether looms large in the history of the great divergence that led to a materialistic concept of design and an idealistic concept of art. Unlike the ‘fenced-in high culture’ of art, the materialism of design is a key factor in its economic capture by practitioners who are subordinate to the profit motive, who disparage themselves as problem-solving service providers and who rarely dare assert their own autonomy, let alone rebelliousness.22 Yet designers who think in terms of solutionism still exert considerable influence on society. This narrative is by no means seldom at odds with reality, the actual intervention being left to the players to which design is indentured, namely industry and business.23 Yet the designer as service provider still dreams of social responsibility, sustainability, gender equality, participation or pragmatic utility. That there really is such a thing as sustainable, socially responsible or participatory utilitarian design obviously cannot be denied. The discussion that follows will nevertheless have to make clear that these are merely symptoms obscuring the much deeper causes, just as

design’s drift into ‘creative industries’ – the name says it all – has sealed its economic capture as a problem-solving mechanism.

As already said, economic design critique, unlike aesthetic design critique, has a long tradition to draw on. It has been part of the Soixante-Huitards’ general condemnation of consumerism at least since Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944), with many designers of renown joining in the chorus. In 1968 Max Bill spoke of design as akin to hairdressing and in 1971 Otl Aicher dismissed it as being ‘in the reins of industry’. The critique from theoreticians of design was even more damning, and design increasingly came to be associated with consumerism and merchandise, falling into disrepute as at once venal and banal. Writing in 1973, Gert Selle was forced to face the sobering truth that while there had been many theoretical and practical attempts at socially responsible design beyond the reach of industry, these had ‘congealed in their historical inconsequentiality’;24 Hans Magnus Enzensberger saw in ‘advertising, design snd styling’ mere vehicles of neoliberalism;25 and in 1970 Wolfgang Fritz Haug willingly went on record with the following aphorism: ‘The role of design in a capitalist environment is comparable to that of the Red Cross on the battlefield. It treats a few of the wounds – though never the worst – that capitalism inflicts. Its cosmetic exercises, which make things look rather less awful here and there, and hoisting of the banner of morality in reality merely prolong capitalism, just as the Red Cross prolongs war. Design’s formative impulse thus upholds the general deformation. It is responsible only for questions of presentation, environmental presentation.’ 26 The fate of design today, to quote an even more extreme take by Walter Grasskamp, is consumerism and hence, ultimately, the rubbish dump.27

Design has still not recovered from this negative image, which has only become more entrenched since it was lumped together with consumerism in 1968. While Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction (1979), Gernot Böhme’s Aesthetic Capitalism (2015) and Frank Trentmann’s Empire of Things (2017) all tried hard not to condemn the consumption of culture but to view it instead in relation to the formation of taste as a social badge of distinction, most critiques of design have been critiques of consumption generally. Writing in 2010, Peter Sloterdijk defined the ‘new smart middle classes’ as a ‘design civilisation spanning the whole world’,28 in which the creativity of the erstwhile avant-garde had mutated into design as a tool of everyday manipulation and the enslavement of consumers. Other critical voices from the academic heart of the design system go so far as to speak of design as ‘liberated from all metaphysical considerations as well as from truth, morality and other Western values’, and of having degenerated into mere finishing with which to make ‘the surfaces of our utterly technoid environment more aesthetically pleasing and user-friendly’,29 and of economic design as tantamount to ‘the objective degradation of the world’.30 These are not isolated opinions, but rather part of a larger shift that apprehends design as mere styling, degradation, superficial prettification, inane and purely commercial superfluity that will end up on the rubbish dump, or as a realm of shallow sensuality, an aesthetic ingredient of capitalism that sets out to manipulate, seduce, deceive, desensitise and disenfranchise or even to discipline us and cash in on our attention economy.31 This collection of examples drawn from the past seventy years might be continued ad infinitum. What is abundantly clear from them is that design, rightly or wrongly, has an image problem.

Design as a discipline, however, has been blithely ignoring its lousy reputation, preferring instead to engage in self-praise. ‘Because design changes the world’, ‘The world is an object and an outcome of design [...] To design the world is a moral obligation’, ‘Design is a key discipline of the future’, ‘Good design is timeless’, ‘Design is something to hold onto in difficult times’ or ‘The honesty of design’ and other such slogans seek to outbid each other in their romanticism, even as the actual substance of what they are claiming remains diffuse.32 The design scene hails the mystique of its own artefacts and with quasi-religious solemnity promises to make the world a better place. As models for its moral imperative it will probably cite the Arts and Crafts movement, or the Werkbund, or the Bauhaus: design the do-gooder now ossified as a topos of solutionism. One consequence of this that has been observable since the 1990s is the breathtakingly inflationary use of the term for everything from furniture to the landscaped garden to sausages (fig. 2) to cosmetic surgery. Even business consultants now describe their work as ‘design thinking’.33 The design hype also accounts for the economic success of the industry, which in terms of economic clout ranks third after the automotive industry and machine-building – and not just in Germany either.34 The great strength of contemporary design apparently resides in its ROI, in its measurable results, in companies that turn a profit with design. Yet this economic strength is also its great weakness, in that it weakens the position of designers, who have to submit to the dominance of the market, and marginalises the aesthetics of design and its origins in art.

The design-art dichotomy no longer applies, inasmuch as the boundaries between art and non-art are already at an advanced stage of dissolution. It has even been predicted that anything created or modelled, including art, will soon be subsumed under the heading of ‘design’;35 and it is indeed the case that art has made many attempts to

dismantle hierarchies. The first staging of Richard Wagner’s ideal of a Gesamtkunstwerk and the advent of classical modernism with its invocation of the essential unity of art and everyday life all but suspended the design-art dichotomy; and in academia it has long been obsolete, the ostensible differences between high and low having been levelled out many times over, whether in John Dewey’s Art as Experience (1934), the inquiries of Aby Warburg (1866–1929) into the afterlife of images, George Kubler’s The Shape of Time (1962), or by ‘visual studies’, the ‘pictorial turn’, the ‘material turn’, the ‘sensual turn’ and Actor-Network Theory (ANT). And now that the spatial separation of art, which belongs in museums, and design, which is part of everyday life, has been overcome, most art museums also have a design department. The Humboldt Forum in the resurrected Berlin Palace, for example, has adopted a format of the Early Modern Age, the cabinet of curiosities or Wunderkammer, thanks to which it can display art of all genres without hierarchies. More and more exhibitions, moreover, are now devoted to the work of individual designers. The design artefacts of Jasper Morrison at documenta 8 in Kassel (1987), for example, were accorded the status of art, which in the decade to come was to have a profound influence on Konstantin Grcic, Jonathan Ive and the Dutch collective Droog Design. Western contemporary art has likewise had to overcome its fear of design on multiple occasions and Jeff Koons, Damian Hirst, Takashi Murakami and KAWS have all followed the model of Asian countries by reuniting design and art. More and more exhibitions now show design under the banner of art, among them the spectacular shows of fashion design at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the 2018 exhibition called Design in Midcentury America at the Milwaukee Art Museum, the MoMA’s many design shows, including its overview of post-1945 Good Design , and the Tate Modern’s 2018 exhibition devoted exclusively to the works of the Bauhaus textile designer Anni Albers.

Yet whether it is in the world of art, in academia or on the museum-scene, this dismantling of the hierarchies separating design and art provides only a semblance of the design-art dichotomy having been overcome. In reality, it remains ineradicable – at least in the collective perception of Western consumer societies. After all, it is above all the neoliberal ‘society of singularities’ that is so wholly caught up in the myths of the materialism of design and the idealism of art.36 It is here, therefore, that the annoying trend of declaring ordinary, mass-produced wares to be ‘unique’ in order to boost sales is most prevalent. Such items are acquired like works of art and their putative share in the ‘liberal arts’ presented as a promise of freedom, even though 90 per cent of all works of art these days are in fact commissioned by public or private patrons.37 In the 1990s this artification of design even became a subject of interest to jurisprudence, which by legal fiat declared the chairs of Le Corbusier and Marcel Breuer to be works of art, thus elevating them from the lowlands of design to the Olympian heights of art.38 The ‘creative industries’, too, have cemented the design-art dichotomy by endowing certain works with a certain aura or mystique and hence singularity so as to ensure their reception as art.39 The creative economy is booming, though the work of the designer is not properly appreciated. Not only is there a large cohort of struggling designers, but even successful star designers are amazed at how little their work is valued on the free market.40 The artification of design, it turns out, is just a marketing facade born of the hegemony of ‘authenticity’, behind which the design-art dichotomy lives on. This is ‘the dark side of the boom’.41

It is against this backdrop that design theory has stalled for what will soon be three generations. The reason for this, as Selle wrote back in 1973, is its subservience to the economic power apparatus, which ‘unperturbed, continues to insist on its right to societal theorising, i.e. to the ideology that it represents’.42 The investigation of design aesthetics in what follows will therefore attempt to break out of the perspective imposed by this same apparatus by calling into question its myth of the design-art dichotomy. This change of perspective will seek the philosophical unity of design and art beyond their myths and clichés, beyond the now economically driven museums and beyond the seemingly indestructible notion of design as materialistic and art as idealistic – but also beyond any cloud-cuckoo-land Arts and Crafts or Flower Power romanticism. The design-art synthesis should be conceived of not as flight from solutionism and economic neoliberalism, but as firmly anchored in their everyday reality. The design-art synthesis turns on the attitude of its actors; for as will become apparent, it is not just the external factors of industrialisation and economic constraints that determine how design is valued. The reality is rather the other way around: The history of this problem might even help us to understand that it was in fact the conflicts of design aesthetics that made it possible for it to be delivered up to the economic power apparatus. The deartification of design brought about by art, industry and Pragmatism, in other words, was the precondition for its narrowing to the economic function of affirmative problem-solving. Only through deartification, only by banishing autonomy, rebelliousness and interpretive openness was affirmative design able to lay itself open to the entrepreneurial imperative. This is a dilemma from which the neoliberal artification strategies that instrumentalise old myths cannot liberate themselves.

The diachronic reflections in what follows therefore seek to answer a specific question, which is to specify what it is that distinguishes design from art, without ever actually defining design and art. As is evident from the philosophical and theoretical discourse, both concepts have so far eluded any exact definition and are highly complex.43 The clichés they spawn that have become lodged as myths in the collective memory, by contrast, have clear conceptual boundaries and are not especially complex. Searching for the causes of their emergence entails inverting the standard perspective of history to the view ‘from below’. This will allow closer scrutiny of buzzwords like ‘artistic licence’, the ‘autonomy of art’, the ‘unique work of art’, the ‘serialism of design’, the ‘functionalism of design’ or ‘design as problem-solving’, all of which are a product of academic theorising and eventually mutate into reductionist clichés. As myths, these seep into the collective memory until they are eventually played back to those same scholarly circles for further consideration.

The quest for the philosophical origins of our definitions of art and design and their mythical remodelling need not lead to a redefinition. What is aspired to is rather their ‘determinate negation’. This concept, which was introduced into philosophy by Hegel and taken up by Adorno and Critical Theory as ethical social critique, is the critique of entrenched myths, whose deconstruction might yet open up scope for something different.44 The ‘determinate negation’ is more than just rejection, being also a solid pointer to how something once was and should, or could, be now. The ‘determinate negation’ of design myths will not supply any new definition of the key concepts, but will instead attempt to uncover the faults that have afflicted them hitherto. One such fault is the commonly applied notion of art as idealistic and design as materialistic. Its

‘determinate negation’ will pave the way for new conceptualities and for a new understanding of the self, including a new design attitude. ‘Determinate negation’ will at least bring the design dilemma to the fore, if nothing else. The realisation that we are in fact dwarves standing on the shoulders of the giants of the design dilemma would itself be part of the solution to the problem of problem-solving design.

Design was born in the nineteenth century, in the age of industrialisation – at least according to the history books. In this telling, the machine was the mother of design; for it was the machine that spawned the mass-produced wares that for many were what constituted design and made it categorically different from the unique work of art.45 But the industrialisation myth has feet of clay in that it overlooks the fact that design has always existed. Not only is the series not its defining characteristic, but countless objects are designed outside the realm of industrial product design, as the output of bespoke tailoring, interior design, goldsmithing, glass-blowing and cabinet-making proves. It follows that there is as much design in the unique artefact as there is in mass-produced wares. Besides, serial production is not an invention of industrialisation, since it existed long before that. The serial production of votives, tableware and other objects of everyday use – oil lamps, for example – has been known at least since Antiquity, if not before. Early modern collections were well appointed with proto-industrial, serially made objects such as small terracottas, silk flowers and Nativity scenes;46 and the Gutenberg Bible of the mid-fifteenth century is an impressive example of what was then a new method of mechanical mass reproduction: book printing. There therefore seems little point in having the history of design begin with industrialisation, especially as the mechanisation of serial production processes and the machines developed to that end are not a modern invention; hence the talk of the ‘medieval industrial revolution’, for example,47 even if the difference in scale compared with the modern machine age remains beyond dispute. Situated somewhere between the unique object and the series, the aesthetic peculiarities of design are thus as old as civilisation itself. Design, in other words, predates the modern age, though it arose at a time when no distinction was drawn between design and art. While the word ‘design’ is an English invention of the nineteenth century, viewed historically it was born not of industry but of art. Design was initially a facet of art, and only in the course of the great divergence did the two drift apart as art migrated to the museum, leaving design to the purely utilitarian domain. Since then, the educated classes have worshipped an art that to the rest of society has become aloof, lifeless, obscure, while the demand of the others for aesthetic artefacts outside the confines of the museum has tended all too easily towards the cheap and vulgar, as John Dewey noted in 1934.48 And since the cheap and vulgar are all too frequently conflated with design, Dewey also tried to show that the experience of art naturally extended to the applied arts, too. Such a design aesthetics is thrown into relief only when viewed in relation to the aesthetics of art. To do this, however, we first have to examine the aesthetic and institutional causes of the great divergence, some of which lie deep in the pre-modern era, when the separation of art and handicraft that would culminate in the separation of design and art began.

The term ‘art’ stood, and still stands, for the ideal of aesthetic autonomy as a bulwark against the economic, entrepreneurial or functionalist capture of design. Yet since the dawn of the modern age, art has also served design as a shared source for the history of forms and styles in which all artistic genres are rooted. Owing to certain developments in the pre-modern era that drove a wedge between design and art, however, that same claim to aesthetic autonomy had become porous and in need of repair. As noted, the developments in question took place long before the nineteenth century, when industrialisation was at its height.

The three aspects of their history that will form the focus of Chapter 1.1 are as follows: the re-ordering of the hierarchy of the senses, a different history of aesthetic autonomy and the art-theoretical claims of mimesis or figurative imitation. The aesthetic and reception-aesthetic causes of the great divergence had an institutional impact, too, as when the academies affirmed the divergence and art museums styled themselves an aesthetic contrast to design’s preoccupation with the things of everyday life. The great divergence was at its peak in the nineteenth century, a period that will be accorded closer scrutiny in Chapter 1.2. This will show that the problem hitherto diagnosed by the discourse was not so much the industrial machine as the general deterioration in taste resulting from the great divergence. Finally, Chapter 1.3 will concern itself with the design-art dichotomy, and by reconstructing the etymological evolution from disegno to design will arrive at an aesthetic synthesis. This particular discussion will provide a timely reminder of design’s true origins in drawing, which these days are all too easily forgotten, as when the term ‘design’ is used for strategies, say, or planning processes. Hence the importance to any analysis of the design-art dichotomy of differentiating clearly between drafting, planning and production; for whereas drawing (disegno) makes ideas perceptible to the senses and opens up hitherto hidden possibilities, planning is an organised process consisting of a series of purposeful decisions and actions, at the end of which stands production. Planning and production, in other words, are about institutional implementation as a service (of many hands).49

In the Middle Ages, design and art constituted a single discipline. This explains how the medieval building yard or Bauhütte came to be so deeply romanticised by both modernist designers and exponents of the British Arts and Crafts movement. The Weimar and Dessau Bauhaus, which recalled the Bauhütte even in its name, was likewise conceived as a place where the applied arts and fine arts would come together on equal terms, and the Bauhaus Manifesto of 1919 enshrined this in its rallying cry: ‘Let us then create a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist!’50 Like those early building yards, the artists’ workshops of the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Age were structured without any ‘arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist’. The workshop of Cennino Cennini (c.1370–1440), for example, produced paintings, painted standards, signs and chests, supplied drawings for embroiderers and printmakers and attended to the artful application of make-up on women.51 Pre-modern artists undertook to aestheticise all spheres of life for their elite patrons. They painted, sculpted, decorated and sought to optimise the techniques necessary to all of these. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) has been hailed as the first great artist-designer, whose repertoire of applied art ranged from dams to flying machines, from weaponry to costumes for the court of the Sforza in Milan – and much else besides. Michelangelo (1475–1564) carved his Pietà in marble, painted the ceiling frescos of the Sistine Chapel, ran the building yard for the new St. Peter’s basilica and even designed uniforms for the Swiss Guard. The Bolognese sculptress Properzia de’ Rossi (c.1490–1530) was as much at home in art as in craft, and created everything from portrait busts to altarpieces and microsculptures made of apricot, peach and cherry stones. Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) built the piazza and colonnade in front of St. Peter’s, carved an Apollo and Daphne group for Cardinal Borghese and produced chairs and candelabra for both churches and palaces. As court painters to Louis XIV and Louis XV respectively, Charles Le Brun (1619–1690) and François

Boucher (1703–1770) drew designs for Gobelin tapestries and porcelain dinner services, even if these days they are famed mainly for their history paintings. Today they would be called the ‘artistic directors’ of the royal manufactories, whose production processes – nota bene – had long rested on an efficient, proto-industrial division of labour. The pre-modern artist, in other words, was also what would now be called a designer; and as a designer, he or she generally supplied the drawings, leaving the actual manufacture to others. In the course of time, however, this interdisciplinary unity began to break apart. First to go was craft, followed in the modern age by design. Preindustrial aesthetics had already smoothed the path to industrialisation by the time the great divergence was noticed. By then it was almost too late to change course, although Gottfried Semper (1803–1879) put up a vigorous defence of the old aesthetic unity, as did William Morris (1834–1896) and Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) after him. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the positioning of design somewhere between artistic autonomy and entrepreneurial heteronomy was being disputed all the way up to the highest political circles. When the chairman of the German Werkbund Theodor Fischer (1862–1938) told its annual conference in Munich in 1908 that aesthetic questions should be answered by individual artists and not by organisations or business enterprises,52 his ‘Haltung ’ or attitude signalled that design was now in crisis-mode. Fischer tried to keep the art in the design and to defend it against other camps and interest groups, although it was the other camps that would gain the upper hand after the Second World War. Design and art then became institutionalised antitheses, as attested to by the declarative book title Design is not Art (1998), to name but one example.53

The evidence of design’s dilemma between art and problem-solving is to be found even in the terminology, which after all distinguishes between applied and non-applied arts. This terminological distinction makes sense, in principle, given that design is applied art, which is not the same as art. What matters is which distinctions are accorded the limelight, and which not. As will become apparent, myth-making alleges distinctions where previously there were none, if only so as to set the one discipline apart from the next. It was the terminological distinction between design and art that led to that incisive design polemic that was outlined in the introduction. Of course, critique of commercialised design is warranted in certain cases. Of course, there is such a thing as affirmative design born of cupidity, design as mere styling or ‘shallow sensuality’. Yet that is no reason to drag a whole discipline into disrepute; after all, there is also such a thing as affirmative, commercial and trivial art, which has never been cited as grounds to disparage all artists. This one aspect of the alleged differences between design and art alone should suffice to give us an insight into the world of myth and its wanton disregard of the fact that all the arts are aesthetic. If, on the other hand, they are vulgar, then they are also unaesthetic. Art and design are both located somewhere between the aesthetic and the unaesthetic. That they vary in quality is not a difference but a point in common.

Any discussion of aesthetics is bound to address first and foremost the five human senses; after all, the term itself is derived from the Greek aisthesis, meaning sensory perception. The history of design aesthetics is at the same time an account of the historical problem (Problemgeschichte) of the changing hierarchy of the senses, which has had a crucial influence on the great divergence and hierarchical ranking of design and art. The eighteenth century saw the hierarchy of the human senses undergo a paradigm shift. It was then that the sense of touch, until then held in high esteem, including by no less a thinker than Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), fell victim to widespread disparagement. The consequences of this for the applied arts, that is, for the design of objects of use that are touched and held, were dire. Yet they have since disappeared from the purview of scholarly interest. Also worth remembering is Kant’s notion of aesthetic autonomy, which today is attributed solely to art, even though Kant himself conceived it as a design aesthetic – which is all the more astonishing given that the academies had been trying to keep the applied arts out of their hallowed halls ever since the Renaissance. The autonomy of the fine arts began in the academies, and the role later played by Kant should be corrected to make it clear that for him, aesthetic autonomy was an argument against the divergence of art and design. Their divorce would be finalized only after 1800, specifically by the aesthetics of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), in the wake of which the number of art museums multiplied rapidly. Then there is a third aspect of aesthetic history, which although little heeded by scholars is undoubtedly relevant to the great divergence, and that is the dialectic of abstraction and imitation, which since the Late Middle Ages has had a formative influence on how design and art are appraised and appreciated. That design products are not figurative as a rule, whereas the meaning of art throughout the modern era has been presumed to reside in its imitation and enhancement of nature, that is, in its capacity to represent, has played a crucial role here. The objects of use created by the applied arts, by contrast, do not imitate nature and are not mimetic. A spoon, a hammer, a crinoline dress are all abstract entities which, as in architecture, cannot be traced back to any model in nature. As will become apparent, modern design critique had an aesthetic problem with abstract form. The historical problem of the aesthetics of abstraction dates back to the Late Middle Ages and was articulated first in the critique of architecture, whose expulsion from the erstwhile trinity of the fine arts (architecture, sculpture, painting), set a precedent for that of design.

The hierarchy of the senses began to change in the course of the eighteenth century. The two remote senses – seeing and hearing – were elevated to the ‘higher’ senses, while touch, smell and taste were downgraded to man’s ‘baser’ faculties. Since then, Western societies have lived in a culture of seeing and hearing to the exclusion of physical contact, in other words the sense of touch, which is no longer sought or

welcome. Museums of art and design have become temples of purely visual, handsoff knowledge acquisition in which every exhibited artefact is placed at an insuperable distance from the viewer. Glass cases, barriers and alarm systems enjoin us to contemplate only and prohibit any physical contact. This has the effect of setting the exhibits apart from the design artefacts of everyday life, since cups, spoons, garments and other ‘applied arts’ are constantly exposed to touch and use, and without them would not work at all or would not be fit for purpose. A vacuum cleaner that may not be touched is a vacuum cleaner no longer. It is purposeless, or, to be more exact, purpose-free; and alone this aspect transports it into the positively connoted role of ‘art’, which after all derives its freedom primarily from its normative purposelessness. Even if there are now performative arts that allow or evoke direct physical contact with ephemeral artefacts, touching remains taboo in the non-performative arts of the West. The touchable-untouchable antithesis originates in the steep hierarchical divide between the senses of touch and sight, which endures to this day in an aesthetics of distance. The dichotomy between feeling or fingering and looking forms the aesthetic foundation on which the design-art dichotomy rests.

Yet the touching-viewing dichotomy was virtually unknown in pre-modern times. Of course, there had been champions of visual primacy who emphasised intellectual as opposed to material cognition ever since Plato. But the primacy of visus or tactus had not yet been resolved, and even the Gospels tell of the struggle over the relative value of seeing and touching. We have only to think of the ‘Noli me tangere’ scene and, as if by way of a contrast, the figure of Doubting Thomas who ‘sees’ with his finger and ‘grasps’ the reality of the Resurrection only when he is able to touch the wound in Christ’s side.54 The Early Modern Age set great store by the sense of touch and was fascinated by the idea of ‘grasping’ in the truest sense of the word, as is borne out by the art of that period. When the Flemish painter Lieven Mehus (1630–1691) painted his Blind Sculptor in c.1660 (fig. 3), what interested him was evidently the comparison between the senses of touch and sight. Seated on an ashlar with a marble head of Homer in his lap, the blind artist is feeling his way around the sculpture with his right hand, while fingering the painting propped up against the wall beside him with his left. He is not facing either object, but rather tilts his head back with his sightless eyes firmly closed. Not by chance is he depicted cradling the stony face of Homer, the legendary blind visionary and epic narrator of the Iliad and Odyssey. Blindness, here, is interpreted as a virtue of the true seer and the sense of touch as a window to reality, which is spatial and three-dimensional. The essence of the Homer portrait, or so the message of the work seems to be, can only ever be felt, not seen. It gains visibility only through the painter, who translates its tactile plasticity into the visuality of a painting. Mehus’ Blind Sculptor is thus an allegory of the painter, whose challenge is to bring to life the haptic qualities of reality in a purely two-dimensional image so that the act of viewing the painting stimulates the viewer’s sense of touch55– there being no empirical experience of the world without touch. The importance of touch expressed in Mehus’ painting became a preoccupation above all of painting, which after all is heavily reliant on creating visual illusions of plasticity; hence the popularity of both blindness and Doubting Thomas as subjects of Baroque painting. Touching art, moreover, was an integral part of the ritual, ceremonial and empirical normality of the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age, extending even to the physical punishment of art in the

many iconoclasms of those periods.56 A few tactile works of art can still be admired today, among them the Pórtico de la Gloria in Santiago de Compostela (Spain), whose central marble column every pilgrim must touch, and whose reliefs are already visibly worn.

Touching has always been integral to Christian practice, especially in the cult of icons and relics. The practice of touching images of the Virgin and relics grew out of the conviction that the holy, miracle-working powers of sacred objects would be transferred to the devout through physical contact. This was not just a matter of faith, however, and the nascent natural sciences of the Late Middle Ages and – even more so – the Early Modern Age even had a scientific explanation for it, which incidentally was also how they accounted for the movement of the spheres. This legacy of Late Antiquity was called ‘Impetus Theory’, which following its revival in fourteenth-century Tuscany would have its place in the standard scientific repertoire at least until Galileo and Newton. It posited a quantitative and qualitative transmission of power by means of physical contact alone. The key concept here is virtus, denoting both force and virtue, in that virtus in pre-modern times was a measure of both physical and moral strength. While virtue was a force that set things in motion – the heavenly bodies, say – it was also what invested inanimate objects like paintings and sculptures with the moral power of healing, which was believed to ‘impress’ itself on the person touching it (vis impressa). The history of virtus as a concept, which has been discussed in detail – including in relation to craft – elsewhere,57 is also a history of the tactile, even corporeal perception of the arts, specifically of architecture, sculpture and painting.

Even beyond the realm of the sacred, art in pre-modern times could lay claim to a range of ritual and empirical purposes that entailed not only its touch but even its consumption. The point of art originally was never its own material and auratic immortality. The touching of art as a theme in literature can be traced back to Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ovid tells of the sculptor Pygmalion, who was so enamoured of his statue of a woman that he could not help touching it, caressing it and eventually kissing it to persuade himself that the dead matter was not in fact real flesh and blood after all – until the statue really did spring to life and Galatea herself stood before him:

‘Often does he apply his hands to the work, to try whether it is a human body, or whether it is ivory; and yet he does not own it to be ivory. He gives it kisses, and fancies that they are returned, and speaks to it and takes hold of it, and thinks that his fingers make an impression on the limbs which they touch, and is fearful lest a livid mark should come on her limbs when pressed.’58

This metamorphosis attests to the vital force – the virtus – typically attributed to the work of art. There were reports of sculptures of women so seductive that excitable young men actually ravished them even in Antiquity and some are recounted in Roman travel guides of the seventeenth century.59 The Early Modern Age also supplies multiple accounts confirming the equal value attached to both sight and touch in the appreciation of sculpture. The Florentine sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455), for example, told of the discovery of an ancient sculpture of a hermaphrodite: ‘In this statue there was the greatest refinement, which the eye would not have discovered had not the hand sought it out.’ Then there is the story of the monumental sculpture of the river god

Tiber (now in the Louvre) whose discovery in Rome in 1512 had the envoy Federico Gonzaga reporting breathlessly that he had ‘seen [it] with his eyes and touched [it] in detail with his hands’.60 For empirical knowledge acquisition, seeing and touching were both proven methods of art appreciation. Even the extremely fragile pieces of Chinese porcelain kept in the many Wunderkammer and cabinets of curiosity of the period were appraised by being picked up and felt. By the same token, we know that the European artefacts that went on display in China were likewise exposed to direct physical contact.61

Early modern art theory likewise saw the sense of touch as warranting closer attention. Feeling (touch) as a form of art appreciation figured especially prominently in the paragone, the debate on the relative merits of the arts.62 If the point was to rate sculpture more highly than painting, for example, it was averred that the hand ‘felt’ the truth – an argument that would endure into the Age of Enlightenment, as is evident from Herder’s interpretation of touching as truth and seeing as dream, and from Kant’s characterisation of touch as ‘sensory truth’. The paragone of the Renaissance ranked the sense of touch the highest of all the senses, which is why sensory truth posed such a challenge for painters, too. They had to endow their paintings with rilievo, that is, with a plasticity whose visual contemplation alone would suffice to stimulate the sense of touch. Michelangelo was – and still is – hailed as a master of rilievo in painting, which may have to do with his having also been both a sculptor and an architect. Painting’s mission, in other words, was to stimulate the sense of touch even without physical contact. One especially vivid example of this is the Allegory of Love (before 1545, fig. 4) by Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572), which has Cupid lasciviously contorting himself in order to kiss Venus and caress her breast. Bronzino evokes the haptic qualities of the bared flesh in part by modelling it with light and shade, and in part through the putto racing into the picture from top right. He has trodden on a thorny twig, one of whose thorns has visibly pierced the flesh dividing his second and third toe (fig. 5). The sense of touch that sensory theory associates primarily with both sexuality and physical pain is thus given prominence as a key aspect of the theme.63 In fact, it was precisely because it stood for sexuality that touch was such a popular theme in the visual arts. The Allegory of Tactus (fig. 6) engraved by Jan Saenredam after Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) is a good example of this.64

The first public museums that began appearing around 1700 were places of direct physical contact with the objects displayed there. Visitors were explicitly allowed to pick them up, weigh them in their hands, shake them and smell them. The tactile appreciation of sculpture had long been everyday practice. But there were other artefacts that could be touched as well. A visitor to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 1702, for example, described a ‘Cane, which looks like a solid, heavy thing but if you take it in your hand it’s as light as a feather’.65 Numerous accounts of museum visits in the late eighteenth century, moreover, indicate that handling the objects exhibited there was perfectly normal. As a tourist in London, Sophie de la Roche, for example, went to the British Museum and there, by her own admission, picked up a Carthaginian helmet, a Roman mirror and even an ancient urn on which a ‘female figure was being mourned’.

Not only that, but she describes how she tipped out some of the ashes it contained and ‘pressed the grain of dust between my fingers tenderly, just as her best friend might once have grasped her hand’.66 Paintings were also fingered, as were the various tombs, altars and other furnishings in churches.67

Yet there are also one or two written sources from this period that point to attempts to prevent such physical familiarity with works of art, despite its being customary practice. Gianlorenzo Bernini, for example, deliberately planted his marble bust of Louis XIV (1665) on a very wide plinth so as to place it beyond the viewers’ reach.68 And the first recorded prohibition of touch was that introduced in the Vatican Museums just one generation later. That it was the sexual connotations of touch that prompted Pope Clement XI Albani (Pontificate 1700–1721) to have the famous Belvedere Torso

fenced in beyond the reach of visitors’ grubby hands cannot be entirely ruled out.69 Certainly the pope lent greater weight to seemlier forms of art appreciation. Distance was now the order of the day. The enclosure of the Belvedere Torso can be read as an early Enlightenment act ushering in the re-ordering of the sensory hierarchy.

The prohibition of touch in museums that did not become standard until the mid-nineteenth century was motivated not by concerns about conservation as visitor numbers rose, but rather by a methodological shift that elevated visual perception over the sense of touch as the only form of empirical knowledge acquisition that really counted. In the course of time, moreover, keeping one’s distance and eschewing all physical contact came to be regarded as genteel. The hierarchy of the senses became a gauge of social standing, with touch increasingly regarded as intrusive and vulgar, and its avoidance, by the same token, as a marker of restraint and self-control. Henceforth, only connoisseurs and experts (museum curators, for example) would enjoy the privilege of being able to appraise artefacts by literally taking hold of them.70

Scientific theory and the history of ideas were flanked by the aesthetics of distance that evolved out of the symbiosis of seeing and touching, eventually culminating in the presumed supremacy of the former. The perception of sight as the greatest of the senses, which since Plato had gone largely uncontested, helped widen the gap between tactus and visus, even if they were still treated as sister senses and were still deemed reliable for the empirical study of science only when applied in concert. The hierarchy of the senses had been topped by the sense of touch and sense of taste long after the Middle Ages,71 and John Locke (1632–1704) remained firmly convinced that the senses that require direct contact were just as essential to our empirical knowledge of the world as those that do not. While he, too, regarded sight as paramount, he also insisted that it defer to touch for the experience of texture, shape and weight. In fact, the only way of apprehending volumes, distances and boundaries was through tactile experience and by moving through space, said Locke. Touching produced solid empirical results. The primacy that Locke accorded to seeing and touching was to influence the empirical and theoretical study of science for over a century before the heuristic role of the tactile was literally forgotten in the period after 1800.

Only just recently has the history of science dated this downgrading of the sense of touch to the period around 1800. In his influential study of the Order of Things (1966), the philosopher, historian and sociologist Michel Foucault (1926–1984) expressed his conviction that the ‘almost exclusive

privilege’ enjoyed by sight had been evident even in the empirical sciences and ever greater reliance on reason of the seventeenth century.72 Fou cault’s overrating of the sense of sight became cemented in an unshakable narrative that has endured to this day. The classic example cited for the primacy of seeing, the microscope, is also the principal medium of scientific seeing, even if many of those writing at the time of its invention did not see it that way at all. In his book Allerhand nützliche Versuche (1729), for example, the natural philosopher Christian von Wolff (1679–1754) took a sceptical view of the primacy of seeing, arguing that: ‘Experience is an inexhaustible fount of truth [...] Of course there are many who believe that all that is necessary to experience is the eyes, and the other senses as and when necessary; yet just how much our eyes deceive us can be gathered from these experiments.’73

6: Jan Saenredam, The Allegory of Tactus, engraving after Hendrick Goltzius, c.1560

For Wolff, seeing and touching form a methodological alliance, it being their complementarity that enables us to ‘grasp’ things. Indeed, we cannot fully ‘grasp’ anything without the sense of touch, he says. As looking through the microscope cannot be complemented by touching the microscopically small objects under scrutiny, apologists of touch like to field tactile media in its stead, first and foremost among them drawing as an expression of mediated ‘contact’ at one remove from the object.74 The hand that draws what is observed through the microscope makes the seen easier to grasp.

Denis Diderot (1713–1784) was undoubtedly right when, in his ‘Lettre sur les aveugles’ (1749) he emphasised how deceptive the eye would be were it not constantly corrected by the sense of touch; hence his description of the skin as a ‘blind organ’ which through touching and feeling has the capacity to discern beauty above all else. The skin was not merely a surface, he claimed; it was rather a sentient organ,75 which is similar to how Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) described it in his magnum opus on education, Émile (1762). Rousseau, too, emphasised the eyes’ propensity to deception and our unthinking reliance on them. He also called for the other senses – touch, especially – to be properly honed as a means of keeping sight in check: ‘For my part, I

prefer that Émile, instead of keeping his eyes in a chandler’s shop, should have them at the ends of his fingers.’76

The Hierarchy of the Senses and Philosophy Foucault’s early dating of the primacy of sight and citing of the microscope as evidence for the same is not wrong, though it does belittle the value hitherto accorded the sense of touch as crucial to the judgement of craft objects. Shortly before 1800 and hence at a time when touch was already falling into disrepute, Kant singled it out as the greatest of the five senses, which he broke down into the first-class senses of touch, sight and hearing and the second-class senses of taste and smell. His Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (1798) contains the following passage on the sense of touch (Book I, Section 17): ‘The sense of touch lies in the fingertips and their nerve papillae, so that through touching the surface of a solid body one can inquire after its shape. Nature appears to have allotted this organ only to the human being, so that he could form a concept from the shape of a body by touching it on all sides; for the antennae of insects seem merely to have the intention of inquiring after the presence of a body, not its shape. This sense is also the only one of immediate external perception; and for this very reason it is also the most important and most reliably instructive, but nevertheless it is the coarsest, because the matter whose surface is to inform us about the shape of the object through touching must be solid. (As concerns vital sensation, whether the surface is soft or rough, much less whether it feels warm or cold, this is not in question here.) – Without this sense organ we would be unable to form any concept at all of a bodily shape, and so the two other senses of the first class must originally be referred to its perception in order to provide cognition of experience.’

Discussing the grounds for aesthetic judgement in his Critique of Judgement (1790), Kant accordingly treats all the senses equally, grouping them all together as ‘Sinnenanschauung ’ (sensible intuition). The only distinction he draws is that between the discernment of beauty (seeing) and form (touching): ‘The formative arts, or those by which expression is found for Ideas in sensible intuition (not by representations of mere Imagination that are aroused by words), are either arts of sensible truth or sensible illusion . The former is called Plastic, the latter Painting. Both express Ideas by figures in space; the former makes figures cognisable by two senses, sight and touch (although not by the latter as far as beauty is concerned); the latter only by one, the first of these.’77 Kant, then, does not undertake any kind of hierarchical ranking of the senses. Yet not even his plea for cognition at once both visual and tactile could halt the cultural demise of touch, which all too soon was drowned out by the thunderous applause greeting the triumph of sight.

What is also apparent from these examples fwrom this critical period, however, is that the re-ordering of the sensory hierarchy was not taken lightly. While Kant would not budge an inch from his praise for touch, other intellectual heavyweights of the age felt torn between touch and sight. The young and astute Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), for example, lamented the general disparagement of ‘feeling’ (touch) already under way in a theoretical work called Viertes Wäldchen (1769): ‘We have banished [touch] among the coarser senses; we develop it the least, because sight and hearing, lighter senses and closer to the soul, hold us back from it and spare us the effort of