I VERSE UTOPIA

So this is the basic dilemma of our age: we are smaller than ourselves.

In other words, we are incapable of creating an image of something that we ourselves have made.

To this extent we are inverted Utopians: whereas Utopians are unable to make the things they imagine, we are unable to imagine the things we make.

— Günther AndersI VERSE UTOPIA

URBANISM AND THE GREAT ACCELRATION

ALBERT POPE

Birkhäuser Basel

FLOODING FROM HURRICANE HARVEY on Greens Watershed, Tidwell Rd. Looking east from the Sam Houston Freeway, August 28, 2017, Houston, Texas. Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.

FLOODING FROM HURRICANE HARVEY on Greens Watershed, Tidwell Rd. Looking east from the Sam Houston Freeway, August 28, 2017, Houston, Texas. Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.

0.0

THE PROMETHEAN INCREMENT

Henning Wagenbreth, 2007.

Henning Wagenbreth, 2007.

0.1

ADAPTATION AND MITIGATION

A flooded-out suburban street is an excellent place to start a discussion on contemporary urbanism. This image was taken in Houston in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, which hit the city in August 2017. While the hurricane was expected, its severity was not and has subsequently been linked to anthropogenic climate disruption.1 At the time the storm came onshore, there was an excess of moisture in the air because of the increased water and air temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico. This additional heat and moisture accompanied weak steering currents, resulting in a much lower temperature differential between the hurricane and surrounding air. The result was a storm parked over Houston for four days, creating the largest rainfall event ever recorded in the United States and causing $125 billion in damage. It also caused a lot of architects to wonder if design can respond to such an unprecedented event.

The first response to Hurricane Harvey and similar disasters, is for designers to adapt new projects to meet the changed circumstances. Adapting the built world to the hotter/wetter environment of the Gulf Coast certainly has its place. But to limit design’s response to adaptation is to only deal with the effects of the climate crisis, not with its causes. At some point, just pulling people out of the river becomes futile. What is needed is to go upstream and keep them from falling in. And while adaptation to climate change is an important design response, it is not the limit of what design can do. Design can not only respond to the effects of climate disruption; it can also work to mitigate its causes.

Any significant shift toward mitigation requires that we substantially rethink the scope, if not the ambition, of the design of the built environment. Architectural and urban designers are good at adapting to our environmental circumstances. Mitigation, on the other hand, constitutes an entirely different design process. Mitigation requires that we move from a reactive to an anticipatory mode of design. While many of us prefer to respond to the certainty of existing circumstances, we know that circumstances are often volatile, even in the context of the built environment. Like it or not, designers have always needed to anticipate the future, even if that future is limited to the time that it takes to design and realize a single project.

In a world of climate disruption, however, where 50 inches of rain can fall on a city in a few days, anticipation is easier said than done. This difficulty is due, in large part, to our inability to accurately anticipate the future. In order to mitigate climate disruption, we must be able to anticipate its future effects. While this logic is easy to understand, it is far more difficult to execute, given that we live in a period of time in which an endless series of unprecedented events undercut our powers of anticipation. When the past no longer serves as a reliable guide to the future, the mitigation of future effects can only be described as a fool’s errand.

In a newsletter called “The Snap Forward,” Alex Steffen, a climate “futurist,” has developed the thesis that we currently exist in a temporal “discontinuity.”2 In short, Steffen believes that the climate crisis has caused us to lose ourselves in time. “Discontinuity is a moment where the experience and expertise you’ve built up over time cease to work.”3 He explains that discontinuity is a profound reorientation of our relationship to time. It is “extremely stressful, emotionally, to go through a process of understanding the world as we thought it was is no longer there.”

Discontinuity is a disabling confusion that comes from being stranded in the present. A temporal distortion disarms us; we are confused about when we are. Said another way, we are left in the present, living out our future’s past. “There’s real grief and loss. There’s the shock that comes with recognizing that you are unprepared for what has already happened.” Steffen believes that we are in the middle of an ongoing crisis and that we urgently need to check our nostalgia and learn to become “native to now.”4

With regard to design, our powers of anticipation are based on an understanding of the past; yesterday becomes the template for today. To the extent that hour predictably follows hour, day predictably follows day, and year predictably follows year, our future becomes knowable. A breakdown in this predictability destabilizes our material certainties, as it undermines just about every working assumption about what the future will bring. With regard to anticipatory design, we must make plans that are based on the accumulated knowledge and experiences of a planet that scientists tell us no longer exists.5

The only guaranteed aspect of our past experience is that, given our present circumstances, it can only take us in the wrong direction.

THE STRUCTURE OF INDIVIDUATION

We want the creative faculty to imagine that which we know.

—Percy Bysshe Shelley 1

It has been clear for decades that we construct and inhabit vast cities that extend, in some instances, for hundreds of miles. This scale is as easy to understand as reading a map. As a lived reality, however, it barely registers. Our characteristic inability to grasp the world beyond our immediate local, experiential spaces blocks a greater understanding of our larger social and environmental contexts and our responsibilities toward them. It is this failure to see the forest for the trees that explains so many of our parochial responses to problems that are urban, regional, and planetary in scale. Unable to grasp the scope of the environmental factors that enable our existence, we only deal with the issues at hand.

These local biases blind us to our vital dependencies, squandered synergies, and unmet obligations. For the suburbanite, the lush seclusion of the cul-de-sac is the ideal model of urban coexistence. For the Brooklynite, the civic beauty of urban monuments framed by blocks and streets is the only model for a truly civil society. For the exurbanite, dwelling has always been about obtaining an original relationship with nature. While our understanding of the city is directly tied to sensations and statistical abstractions, these sensations remain strictly local and, more often than not, are tethered to the status quo, if not to the urbanism of our past.

We do, of course, “know” better. Over two centuries ago, Percy Shelly defined culture as “the creative faculty to imagine that which we know.” While we may know all about the extensive urban environment we inhabit, that does not mean we have the creative faculty to imagine a continuous city that stretches uninterrupted along 700 miles (1,126.54 km) of the Atlantic seaboard.

We have also “known,” of course, about the scope and magnitude of our urban environments for decades. The Megalopolis, first defined by French geographer Jean Gottmann in the 1950s, was described as a conurbation of lowdensity, self-similar parts that first appeared in the years immediately following the Second World War. As the postwar consumer economy kicked in, and the

indicators of what is today known as the Great Acceleration began to spike, the discrete cities along the Atlantic coast rapidly expanded into the rural spaces between them. Within a decade, these expansions merged with others, forming a nonstop pattern of urbanization that ran continuously from Boston to Washington. The mash-up of cities that constitute “BosWash” today is commonplace worldwide, from the Texas Triangle to the Pearl River Delta in China to the Taiheiyō Belt in Japan to Mega Manila. These conurbations are characterized by merging multiple cities into continuous, interconnected super-regional networks. Far exceeding the confines of isolated cities, these conurbations interconnect unprecedented numbers of people with reliable, fast-moving physical and virtual infrastructures.

As these regional continuities proliferated, something unexpected occurred. The open network of blocks and streets that characterized urbanism for the past century suddenly fragmented into discontinuous cul-de-sac enclaves. Upending a set of urban expectations based on an open, monocentric urban pattern, these closed, spine-based enclaves became the constituent elements of the new megalopolitan conurbation. This is the paradox. As urban extents became ever larger and unknowable, local concerns (neighborhoods) drew into themselves, forming self-defined enclaves, often behind protected gates. Residential subdivisions, office parks, industrial parks, commercial “centers,” and medical districts all withdrew from the continuities of a universal grid expansion. No continuous, citywide boulevards, no more numbered streets (there would be no 600th, 800th, or 1200th streets), and no more experiential (pedestrian) contact. Closed, cul-de-sac, or spine-based development preempted not only the extension of new urban development but also the extension of preexisting parts of the city. These enclaves further bracketed the local, putting actual limits on the world revealed to us by our senses. It tended to confirm our inability to see beyond our immediate local, experiential spaces, triggering many of the myopic responses to the world at large that prevail today.

Even though we know that a new type of closed urban element has upended our familiar urban world, we have yet to imagine its urban consequences. Our strictly local, routine existence dominates our urban imaginary, making it impossible to grasp the world beyond the limited proof of our senses.

1.0.2

THE STRUCTURE OF INDIVIDUATION

The first three chapters argue that all urbanism produces its organizational logic. It brings attention to contemporary urban development’s underlying, spine-based logic. As essential as the structure of DNA is to an understanding of the genome, the spine constitutes the root form of the contemporary Megalopolis, underlying its architecture and urbanism alike. The spine form is ubiquitous, and our knowledge of its qualities and characteristics is essential to any reforms in the contemporary urban environment.

What this root form means in the design context can be demonstrated by hand tools such as hammers or utensils such as spoons. There is a single root form of

1.0 THE STRUCTURE OF

2.0

TERMINAL DISTRIBUTION

SUBJECTIVITY

It has long been argued that society constructs individuals. Simply stated, we construct the world, and the world constructs us. The study of “subjectivity” attempts to understand how society constructs individuals by analyzing the individual itself. In the language of the human sciences, this individual is referred to as the social “subject.” When the study of a subject is extended to the study of cities, it becomes clear that the unique environment of cities constructs unique individuals. From this perspective, we can easily see how individuals in medieval cities would be constructed in an entirely different way than the individuals in industrial cities. Moving forward, we can apply the analysis of subjectivity to modern urbanism, specifically the Radiant City urbanism that emerged in the 1920s, codified in the 1930s, and exported worldwide following the Second World War. Like all cities before it, the Radiant City was imagined to create a unique subject. This subject—the “universal subject” of Modern architecture and urbanism—was a subject like no other.

In the 1920s, the advocates of modern urbanism saw a technical, economic, and political change of such magnitude as to require the reorganization of the city at an existential level. Out of this reorganization, it was imagined that an entirely new mode of subjectivity would emerge. This led to the notion that the urban subject could be both anticipated and designed for. In other words, the constituent of the modern city did not yet exist, but it would be the ultimate result of the latter’s construction. This anticipation of a truly universal subject was hardly defensible, and the early 1970s critique of it was definitive. The critique argued that a truly universal subject did not, and could not, exist but as a figment of a utopian imagination. With 50 years’ hindsight, the universal subject was seen as an agent for the emergence of a brutal and oppressive mode of urbanization.1 It is safe to argue that the universal subject of modern urbanism was a naive attempt to establish an unknown and unrecognizable subject against all subjectivities that came before.

This naivety regarding an urban subject was largely overcome through the writing of French historian Michel Foucault. In the mid-1970s, Foucault redefined subjectivity around two key innovations: that the subject was historically grounded and that the subject was socially individuated. 2 The implication of a historical, individuated subject on the discourse of architecture and urbanism

should have been significant, for it answered much of the critique that modern urbanism was undergoing at virtually the same time. The postmodern critique, however, became a polemic, condemning not only the universal subject but the notion of projecting subjectivity altogether. It can be argued that the problem of Radiant City urbanism was not that it projected subjectivity but that it projected subjectivity devoid of recognizable features. Over the past 30 years, this outright rejection of subjectivity has had drastic consequences that can be summed up in a few simple questions that are rarely asked and almost never answered, even today. Who, exactly, is the subject of contemporary architectural and urban design? Who are our discourses (such as this one) targeting? For whom do we presume to speak? Given that subjectivities are the inevitable outcome of historical forces, what is the role of urban form in their construction? Ever since Foucault’s cogent argument, the prospect of a modern universal subject has been substantially diminished, but the question of “who” nonetheless remains.

Foucault’s conception of a historically grounded subject could help answer the contemporary question of “who?” His conception of an individuated subject, on the other hand, was far more problematic. If architects and theoreticians conceive of the subject at all, they usually conceive of it in collectivist terms. This devotion to the collective subject is nearly second nature to architects and urbanists, and it has all but eliminated any obvious alternatives. It is generally understood that urban spaces such as the agora, the parvis, the royal square, and the village green all created the constituencies they contained. These constituencies and others continue to exist in enduring urban form to this day. These historical forms notwithstanding, more recent examples of collective subjectivity exist—“the people,” the working class, or mass society, to begin the list. They are rarely associated with contemporary urban form. For a whole host of reasons, we are unable to account for a collective subject in the practice and discourse of contemporary urbanism, leading us to discount the projection of subjectivity further. This begs the question of whether Foucault’s analysis of an individuated subject might point the way to an alternative subject position. It will be the contention here that individuated subjectivity is more relevant to contemporary urban form—specifically infrastructural form—than its collective counterpart. Understanding the substitution of the individuated subject for a universal subject and the encoding of that subject in the concrete form of the city will be the primary objective of the text that follows. This rise animates the evolution of recent urban history as the emphasis on forms has shifted from a validation of the collective to a validation of an individuated subject.

2.2

INFRASTRUCTURE

Subjectivities are found encoded at all levels of the built environment. Foucault found them encoded in various institutions such as prisons, asylums, schools, and factories. While he rarely speculated on an urban scale, it is nevertheless true that powerful subjectivities are encoded, not only at the level of the individual building but also at the base level of urban organization. I am referring to the subjectivities constructed by street infrastructure. By street infrastructure, I mean the layout of water and sewage lines, electrical and communications grids, pedestrian walks, and drainage capacity, along with unpaved or paved roadbeds. While largely a matter of civil engineering, the significance of street infrastructure goes far beyond its technical specification. I would like to argue

2.0 TERMINAL DISTRIBUTION

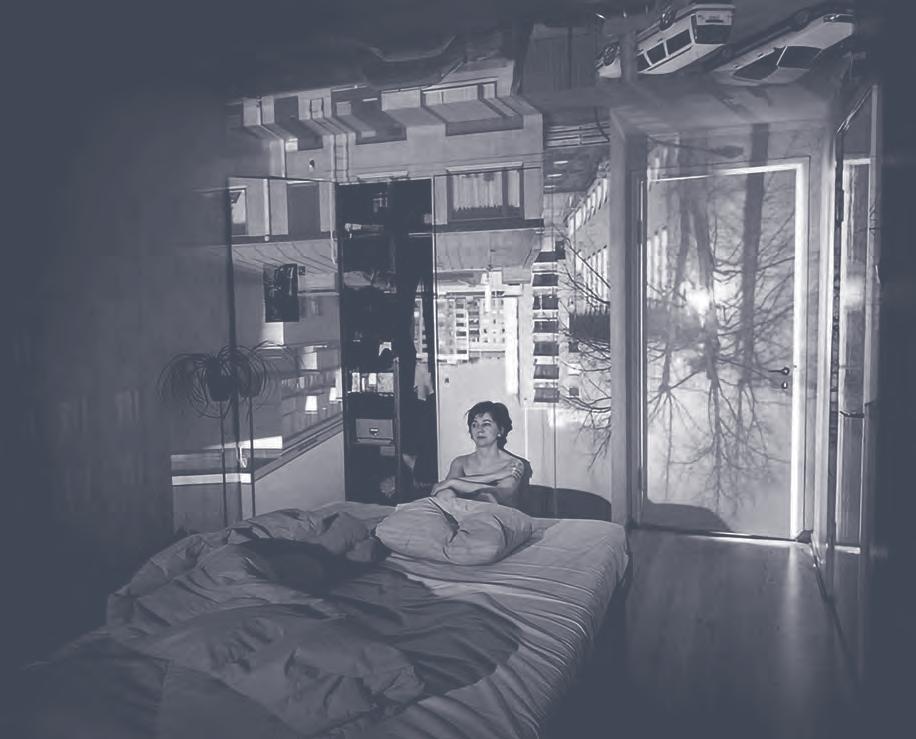

THE SUBJECT OF INDIVIDUATION

The very word suburb denotes an urbanism that unabashedly falls short. The suburb earned its subclass status because it lacks the social and functional integration that has informed every historical definition of the urban.1 This status often leads to a flat-out dismissal of the suburb as a design problem, never mind as a viable starting point for comprehensive urban reforms. Despite its subclass status, this section sets aside any prejudice against the world we have made. It portrays it as a legitimate urbanism that is neither dependent on a historic urban core nor lacking in potential qualities of its own.

Given the suburb’s lack of an integrated public world, private life has become its dominant urban characteristic. Instead of ignoring this quality, the suburb will be considered a scene of a uniquely contemporary type of urbanism characterized by “individuation.” Individuation is the predominant motif, not only of the contemporary Megalopolis, but of modern urban discourse that fully anticipates many of the urban conditions we live in today. As a motif, individuation manifests in the urban dispersion of the Garden City’s single-family housing tracts and the modular aggregation of individual units in Radiant City housing blocks. This argument maintains that, despite its suburban status, it is necessary to embrace mass individuation as a positive social and urban force upon which a viable urban future must be built.

At the outset, it is important to understand that the suburb’s emphasis on individual over collective existence is not a “lifestyle choice” brought about by consumerism. This unprecedented shift toward the private world owes as much to the absence of a viable collective identity as it does to the specific choices made by those of us who live in the suburbs. To say the obvious, public spaces emerge as a reflection of a society’s collective life. If the suburban extensions of cities we have constructed since the Second World War lack a communal life, it is because there is no shared agreement as to what that life would look like. As the Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck put it in the 1960s, “If society has no form—how can architects build the counterform?”2 In this regard, prioritizing individual over collective life is less of an exclusive desire for uniqueness or privacy and more the absence of a shared or collective alternative.

This lack of an integrated public space in contemporary suburban development explains that we must commandeer the public spaces of our ancestors as if they were our own. The suburbs are built upon preexisting urban cores because those cores serve a social and political function. They provide the illusion that contemporary urbanism maintains viable public spaces where all economic, political, and cultural programs intersect with viable collective spaces. These historical spaces are, however, manifestations of a shared life that is a century obsolete, born of a political economy that is very different from our own. No matter how storied or extravagant traditional urban venues may be, they cannot compensate for the absence of spaces where public life directly engages our routine existence.

This absence of public life in contemporary urbanism, like the absence of a coherent collective identity, is not only unfortunate, it is socially and politically destabilizing. History shows us that, if public life is not actively cultivated

(instead of appropriated), a regressive or toxic form of collective existence will emerge to fill the void. Because it is unformed, this inadvertent form of collective existence often lacks explicit political or cultural intentions. The consequence is to see the emergence of individuation’s opposite social and political function. For lack of a more precise term, individuation’s opposite number can be called massification. Turning this binary into a formula, urban individuation is inversely related to urban massification.

The German-American political philosopher Hannah Arendt described this binary shift from individuation to massification as it unfolded in the first half of the 20th century:

. . . the masses grew out of the fragments of a highly atomized society whose competitive structure and concomitant loneliness of the individual had been held in check only through membership in a class. The chief characteristic of the mass man is not brutality and backwardness, but his isolation and lack of normal social relationships. Coming from the class-ridden society of the nation-state, whose cracks had been cemented with nationalistic sentiment, it is only natural that these masses, in the first helplessness of their new experience, have tended toward an especially violent nationalism, to which mass leaders have yielded against their own instincts and purposes for purely demagogic reasons.3

The irony of Arendt’s observation is familiar, yet it is still difficult to grasp. Individuation has an understandable basis, even though it becomes an agent of its own demise. The social relationships—“membership in a class”—to which Arendt refers are predicated on hierarchies that set severe limits upon individual agency. These social relationships were not restored at the end of the Second World War at the onset of the Great Acceleration. Instead, our highly atomized society became even more atomized. It was at this moment that existentialism, as a philosophy, emerged to support individual action. Existentialism instructed us to resist the social structures that brought about the catastrophe of global warfare. Existentialism also instructed us to stoically confront the fact that there is nothing to fall back on but our own devices. The existentialists defined this fallback position as personal “freedom.” As defined, however, this freedom was not liberating; it was tragic. The more we abjure collective hierarchies, the more atomized we become. And as we push forward into extreme

ACCELERATED OBSOLESCENCE

Today, we are living out the future’s past. Technically speaking, this has always been the case, yet there are moments in history when the present is overtaken by a future, a future so richly conceived and broadly anticipated that it begins to block out the concerns of the day.

The transformation of the chemical composition of the atmosphere and the effects that transformation will have on agriculture, sea level, and the extinction of species suggest a future world that bears little resemblance to the one we live in today. The routine appearances of freak weather, acute resource scarcity, and ever more frequent and devastating fires and floods already indicate a present that is about to give way. And while a picture of the future is beginning to emerge—in the white papers of scientists, speeches of activists and politicians, and the fictional worlds in which books, films, and television variously place us—the actual living conditions that climate change will impose on us are as impossible to predict as they are frightening to ponder.

Suspended between a past that is no longer relevant and a future that has yet to be imagined, we occupy a temporal impasse that has stalled forward motion, especially regarding the climate crisis. In the short term, this gap has come to be filled by ever more outrageous distractions of the day. The latest celebrity scandal, reactionary political ploy, retro marketing campaign, or emerging global market all serve to divert our attention from the endless climate catastrophes that occupy the margins of the news. But as the grim toll that climate science has forecast begins to mount, these distractions will ultimately give way to a reality for which we are wildly unprepared.

Trapped between the past and the future, we have become profoundly estranged from the principles and values, if not the worldview, that brought us to this moment. This estrangement from the present is not only conceptual; it is also material. It transforms our view of the most familiar or routine objects that enable our daily existence. These objects, including buildings and cities, fall out of time, belonging to our future’s past.

While estrangement from the objects that populate the present has provoked nearly complete inaction, it can also create the cultural space in which once

unexamined political and economic assumptions, now lethal in their consequences, can finally give way to a comprehensive set of urban reforms. First among these reforms is a fundamental change in our relationship with the object world that surrounds and enables us. Such reforms are not just quantitative in the manner of a routine technical upgrade. They are also qualitative in that they require a revaluation of the cultural practices that structure our daily existence. Before we can consider future reforms, however, we must come to terms with the diminished present from which they will emerge.

4.0.2

SURVIVING OBSOLESCENCE

Estrangement from the objects of mass production is nothing new; planned obsolescence is standard practice in a modern consumer economy. When a

durable artifact outlives the world that produced it, that artifact acquires what an antiquarian calls a patina and a historian calls an aura. Such relics were once limited to museums, antique shops, or the octogenarian’s attic. More recently, only a few decades have to pass before simple objects begin to carry the aura of a bygone world. Long-playing records, fountain pens, fixed-gear bikes, and the entire cityscape of Brooklyn have rushed in to fill the void produced by our ever-shrinking present. Nostalgia burns bright in our future’s past, as every backward-looking political, technical, or commercial distraction obscures the obvious evidence of the diminished present. But nostalgia alone does not produce the kind of profound social and material estrangement that we confront today.

We are instinctively alienated from the obvious objects of environmental decline—coal-burning power plants, sea walls, oil tankers—and their consequences—mass extinctions, retreating glaciers, and the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. We are also aware of how these objects are directly related to the objects of our routine existence. The freeways we drive on, the lawns we maintain, the thermostats we set, the servers we log in to, and the glass walls we gaze out from are all suddenly seen as hostile to our immediate future. In other words, material obsolescence is not limited to the antiquated technologies we now fetishize or to the toxic residue of excessive consumption; it includes the obsolescence of the many things that make up our world—the accumulated artifice of human production.

This cumulative artifice has a name. A 2017 study estimated the mass of the global “technosphere,” the material habitat that humans have created in support of the species—massive fleets of cars and airplanes, continental expanses of managed landscapes, billions of buildings, and the physical and electronic infrastructure that supports it all—weighs in at 30 trillion tons, some five times the weight of the human beings that it sustains. That is approximately 4,000 tons of transformed Earth per human being or 27 tons of technosphere for each pound of a 150-pound person.1 A virtual exoskeleton for the species, everything we do, we do through the technosphere: prepare a meal, buy a shirt, message a colleague, fill a prescription, or simply bathe. Despite their importance to basic survival, these activities and the familiar objects that enable them will come to be perceived as threats to that survival. As it turns out, just being human and alive in the world today requires a significant carbon

In a 2009 lecture to architectural students, German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk spoke about the relationship between an explicated dwelling unit and the city that the unit brings into existence. Drawing literal connection between foam and urban density, he argued that:

. . . foam, in my opinion, is a very useful expression for what architects call density—itself a negentropic factor. Density can be expressed in psychosocial terms by a coefficient of mutual irritation. People generate atmosphere by mutually exerting pressure on one another, crowding one another. We must never forget that what we term “society” implies the phenomenon of unwelcome neighbors. Thus, density is also an expression for our excessively communicative state, and, incidentally, the dominant ideology of communication is repeatedly prompting us to expand it further. Anyone taking density seriously will, by contrast, end up praising walls. This remark is no longer compatible with classic Modernism,

which established the ideal of the transparent dwelling, the ideal that inside relationships should be reflected on the outside and vice versa. Today, we are again foregrounding the way a building can isolate, although this should not be confused with its massiveness. Seen as an independent phenomenon, isolation is one form of explication of the conditions of living with neighbors. Someone should write a book in praise of isolation. That would describe a dimension of human coexistence that recognizes that people also have an infinite need for non-communication. Modernity’s dictatorial traits all stem from an excessively communicative anthropology: For all too long, the dogmatic notion of an excessively communicative image of man was naively adopted. By means of the image of foam you can show that the small forms protect us against fusion with the mass and the corresponding hypersociologies. In this sense, foam theory is a polycosmology. 2

expenditure that is not easily dismissed. In this time of climate disruption, routine objects transform from valuable tools into the instruments of our own decline.

While the distance between ourselves and our surroundings is increasingly sensed, it remains difficult to articulate the unease it creates. When the objects of our mass production and consumption lose their familiarity, they continue to function even as they lose their ability to describe the world in which we now live. An SUV, for example, no longer represents a simple means of transportation—good for shopping and safaris—but our routine participation in environmental destruction. SUVs are an easy target, of course, but the same can be said for the sudden obsolescence of tract houses, jumbo jets, plastic bags, and red meat.

Predictably, there is no lack of pushback in defense of an object’s status quo. Beyond the obfuscations and the outright lies of the politicians, the selfishness of the careerist, the theatrics of the polemicist, or the nostalgia of the consumer, in the light of our imminent future, a single grim fact is clear: the objects of our routine existence, objects by which we negotiate the urban and natural world, are no longer capable of carrying us into the future. Any desire to reform our relationship to a dangerously outmoded object world will require feats of imagination that even an emptied present will find difficult to accommodate.

4.0.3

ON MATERIAL CULTURE

To initiate a reform of the object world, it is necessary to fully understand the role that it plays in our daily lives. Utilitarian objects consistently exceed their instrumental value; they are not merely tools but constitute a crucial explication of the world around us.3 Equal to the vast archives of painting or poetry, the quotidian network of utilitarian objects transforms the base materiality of the world into an environment that is recognizably human. Such representations of our material existence are not to be counted as luxuries; they instead produce the ontological stability necessary for any functioning society. In other words, routine objects make sensible, and thus operable, the tools of human existence in the 21st century.4 It is this vital interpretative function that allows us to 4.0 ACCELERATED

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Each of these chapters began as edited essays. While none have gone untouched by the effort to produce a coherent book, they have all benefited from initial editorial support of Neeraj Bhatia, Sarah Whiting, Cynthia Davidson, Rafi Segal, Daniel Ibañez, Alexander Eisenschmidt, and Elisa Iturbe. Equally important was the editorial support that came later while grappling with the text in its entirety, provided by Kohen Hudson and Maximilien Chong Lee Shin. As much gratitude is due to the students of Rice University School of Architecture, who constituted an involuntary sounding board for these ideas as they made their way through seminars and studios toward their presentation in this book. I would also like to thank the extraordinary Present Future cohort that attended the school from 2015 to 2023. The production of this book was made possible by the administrative support of the staff of the Rice University School of Architecture and the diligence of Andy Entis. Crucial financial support came from Rice University as well as from the enormous generosity of H. Russell Pitman. Academic support, a rare thing indeed, came from Luke Bulman, John Casbarian, Scott Coleman, Andrew Colopy, Lars Lerup, Reto Geiser, Brittany Utting, and Ron Witte. Finally, and especially, real moral support came from Kathrin Brunner and Amanda Pope, to whom this work is dedicated.

INVERSE

Albert Pope

Rice School of Architecture—Rice University, Houston, Texas

Printed with the financial support of Rice University School of Architecture and H. Russell Pitman

Concept: Albert Pope and Luke Bulman

Acquisitions Editor: David Marold, Birkhäuser Verlag, Vienna, Austria

Content and Production Editor: Bettina R. Algieri, Birkhäuser Verlag, Vienna, Austria Proofreading: Alisa Kotmair, Berlin, Germany

Graphic design: Office of Luke Bulman, New York Printing: Holzhausen, the book-printing brand of Gerin Druck GmbH, Wolkersdorf, Austria Paper: Munken Print White 115 g/m² Typeface: Untitled Sans

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023936777

Bibliographic information published by the German National Library

The German National Library lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, re-use of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in other ways, and storage in databases. For any kind of use, permission of the copyright owner must be obtained.

ISBN 978-3-0356-2700-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-0356-2712-1

© 2024 Birkhäuser Verlag GmbH, Basel Im Westfeld 8, 4055 Basel, Switzerland Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 www.birkhauser.com