The third issue! I am amazed and thankful. Once again, this process has helped me learn much about the world and the people around me. I am excited to be highlighting international students on campus. This issue has so many different cultures, and each model gets to share a little something from home. I thank them for allowing BIPOC to share this, and I personally loved working with them at every step. So thank you to everyone who worked HARD on this issue. And a special thanks to the new BIPOC team. The issue could not have been done without yall. Here's to the next issue!

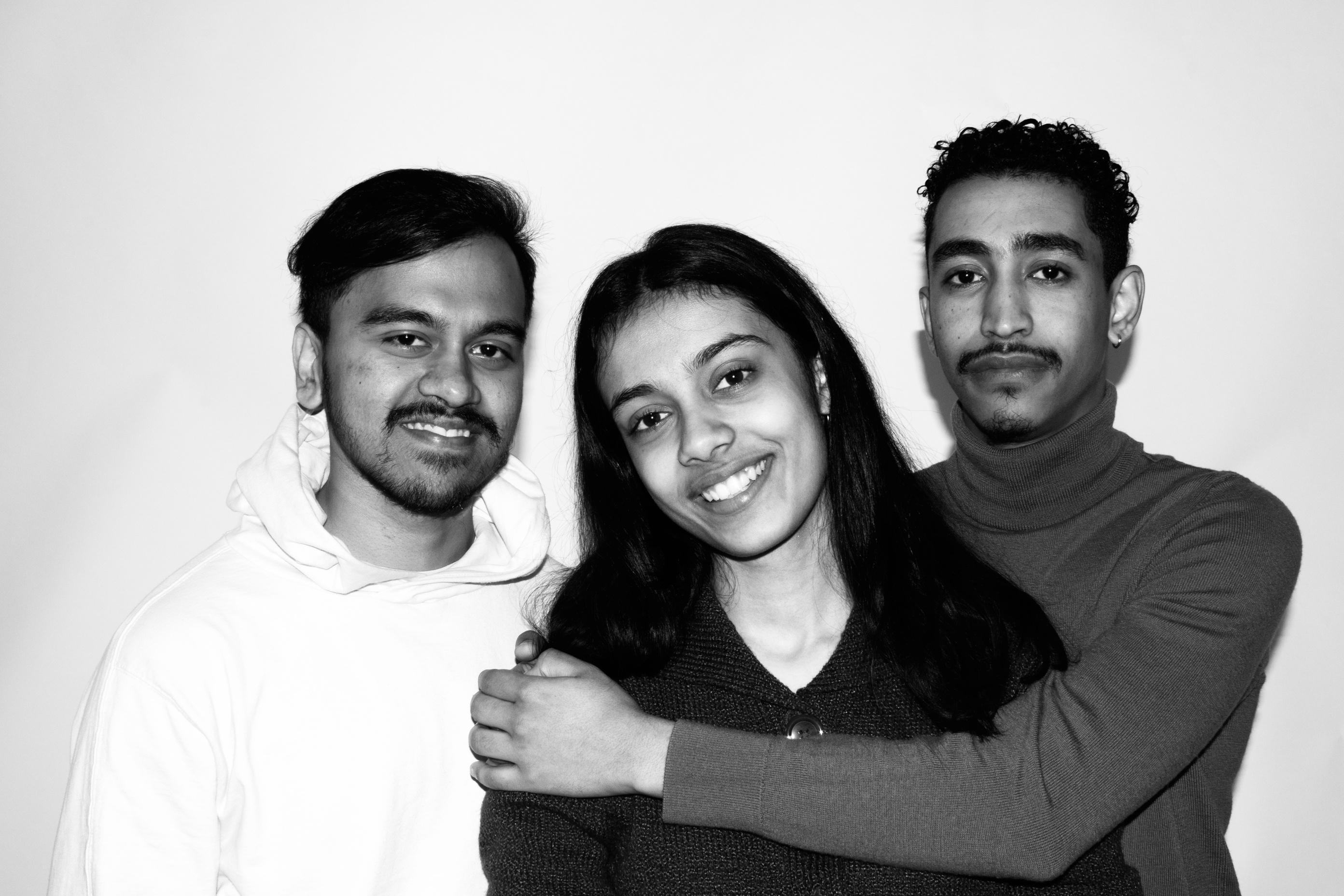

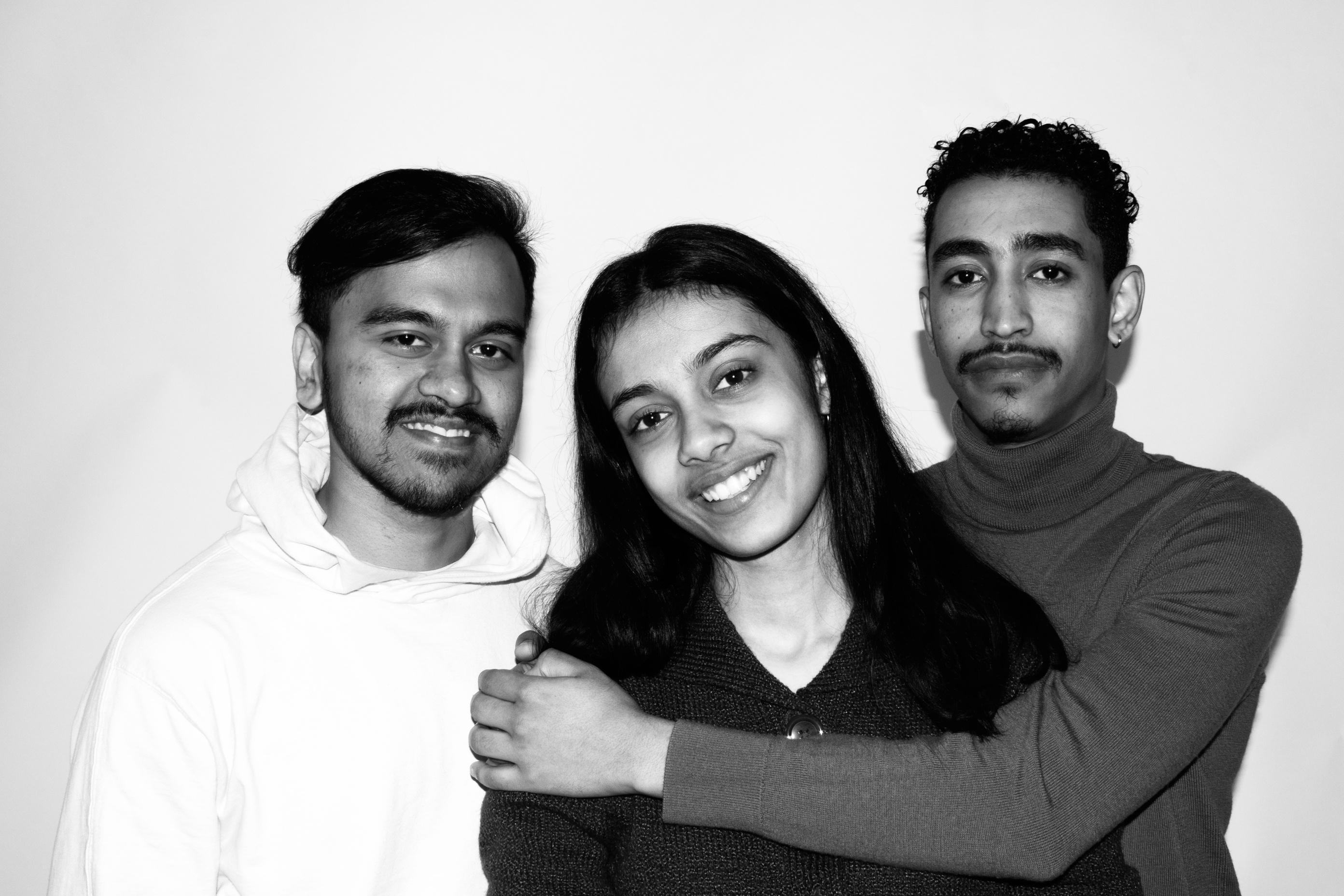

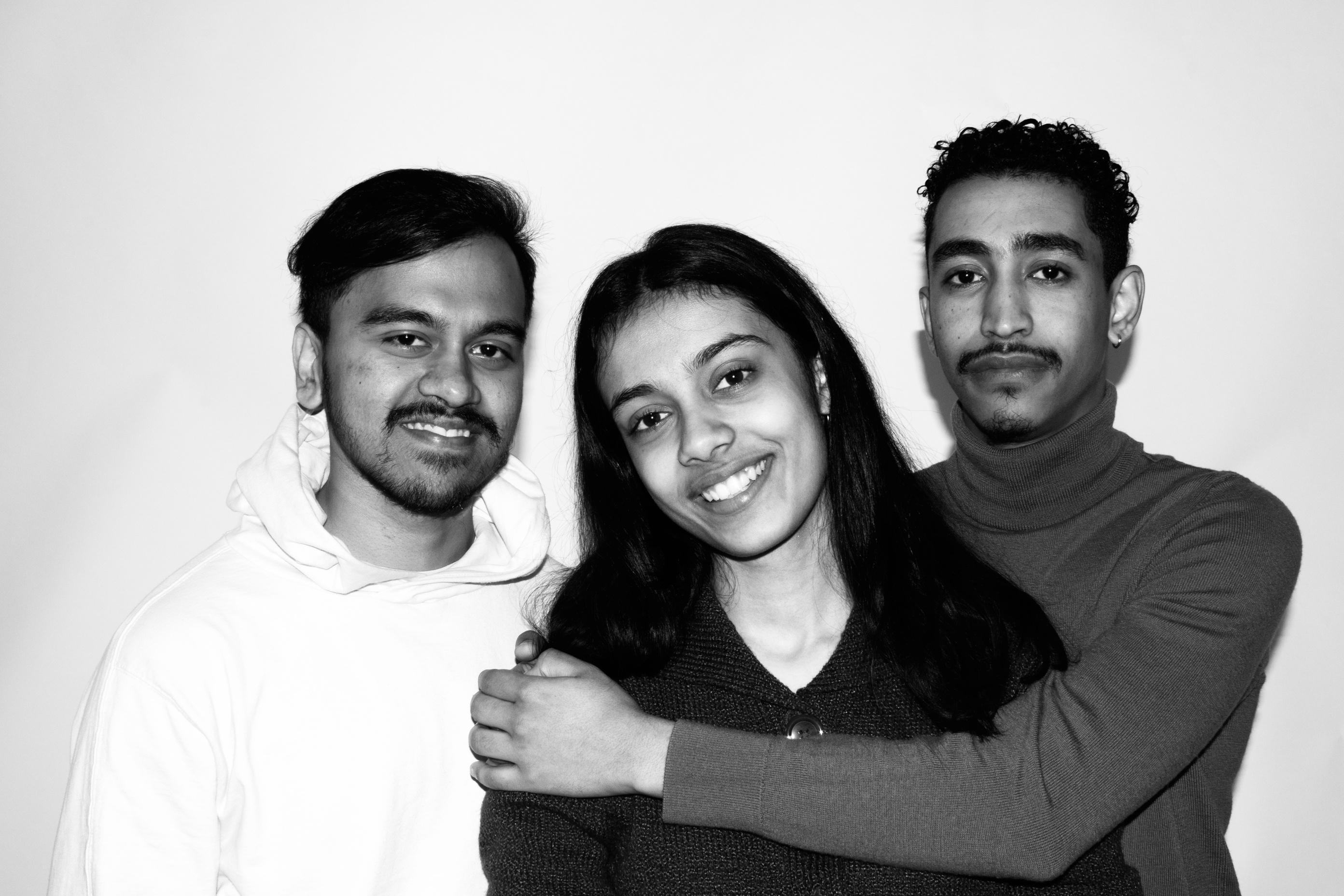

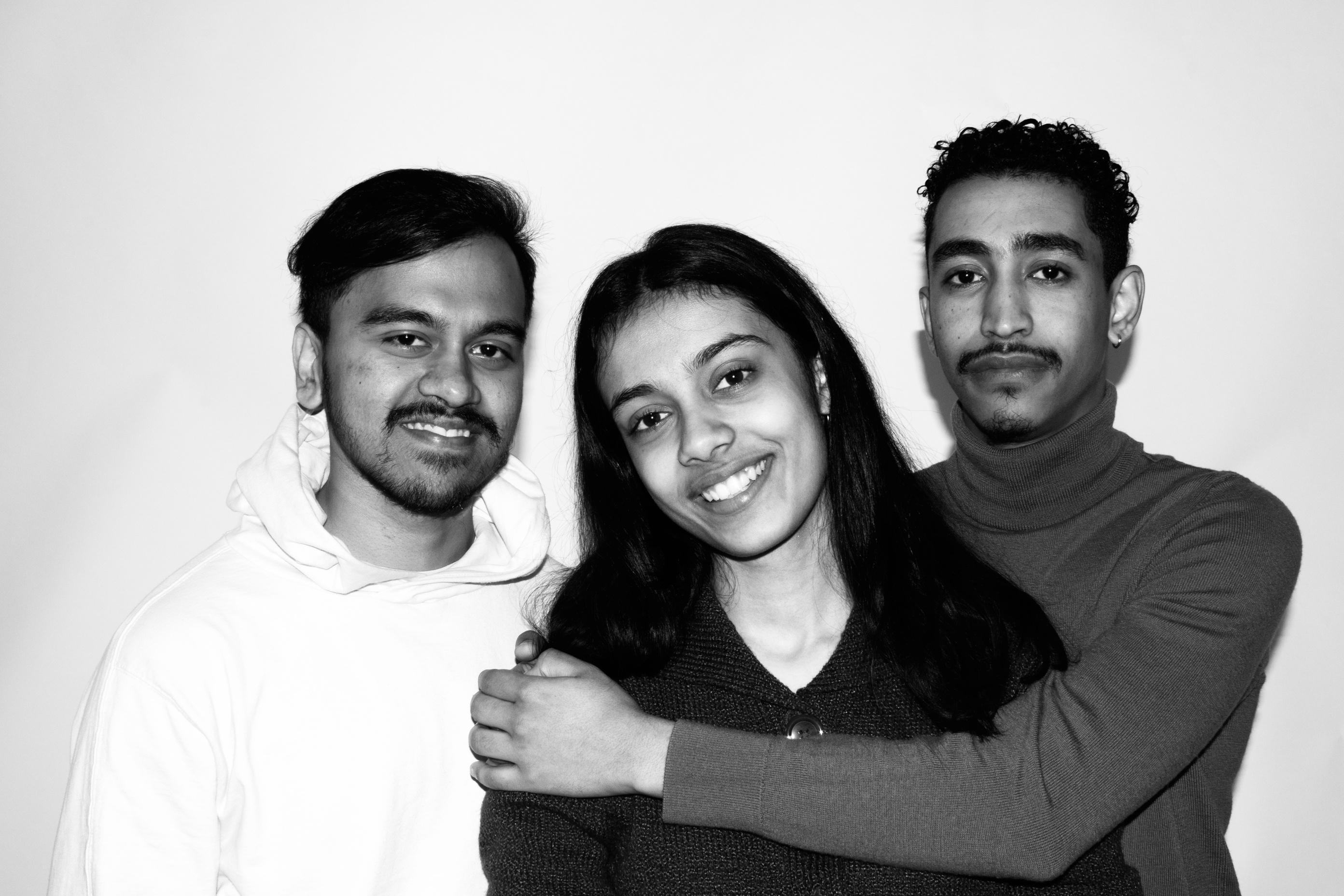

Models

Artists

Mufalo Mufalo Ana Rubianes Sampaio Sofía Chen

This photo shoot is dedicated to showing off Oberlin International Students and the countries they are from. Each Model is featured with photos selected by them that remind them of home. In no way is this supposed to represent every International Student in the world or at Oberlin. Rather this photoshoot is dedicated to showcasing only a fraction of the many beautiful places. International students can come from.

Mufalo What Molds Me

In the early 1990s, Woldeab Woldemariam, a radical revolutionary leader, and one of the fathers of Eritrean nationalism, gathered prominent Eritrean artists and intellectuals to a meeting. He just returned from more than 3 decades of exile, when Eritrea finally achieved its independence in 1991, after successive colonialism from Italy, UK, and Ethiopian regimes. There he tasked Eritrean musicians for an important mission. With great wisdom, he said the following about Music:

“We must understand music’s role in the renaissance of a people. I love music, and I appreciate its power And you are not just meant to create music for the sake of entertainment, but for the revival of a nation, for the deliverance of the Virgin, the beautiful princess.”

This is translated from Tigrinya, and Woldeab Woldemariam clearly stated that music was key to nation building and advancement of society. Indeed, during the bloody years of armed struggle, Music was an abode to the Eritrean population and its freedom fighters. Eritrean musicians were instrumental in instilling national unity when in the 1940s, the UK who at that time occupied Eritrea after defeating Italy in 1941, planned to partition the former Italian colony to Sudan and Ethiopia In the 1950s however, the UN ignoring the will of the Eritrean population, deci-

-ded to federate Eritrea with Ethiopia. During the federation, Eritrean artists used music to preserve national identity, and challenge foreign culture that was engulfing the country. In 1950s, Atewebrhan Seghid, a prominent musician wrote a song called “Aslamay Kristanay - Muslim and Christian”, with message to unite the two religions, and combat sectarianism. The song paved the way for the creation of a united national identity that surpassed religious and ethnic identities. The music of the 1960s, and 1970s continued to

raise political awareness often through coded secret messages to avoid Ethiopian censorship, and inspire the youth to join the armed struggle for Eritrean Independence. In the mountainous northern part of the country, where Eritrean resistance liberated lands, music was instrumental to uplift the morale of the people, promoting social consciousness of equal rights, and an outlet of the Eritrean voice

Woldeab WoldemariamBenhur and other performers to announce that their victory was inevitable. The Italians were the first to fully colonize Eritrea in 1890. They created perhaps the first apartheid in the world, whereby native Eritrean were not allowed to walk through the main boulevard of the capital Asmara, barred from education above the 4th grade- so to allow Eritreans to be smart enough to labor in colonial industrial factories, but dull enough so as to not wake up to resist colonialism. The Italians colonizers were fond of music, and built an Opera house in the restricted center of Asmara. The Teatro di Asmara constructed in 1918, would become a famous venue for Italian musicians to perform orchestral, operatic and band music to exclusively Italian audiences. In 1961, 20 years after the Axis Italy’s defeat, the Asmara Theatre Association famously known as MaTeA, was formed by Eritrean artists and started to showcase drama and music performances in the once-segregated Asmara Theatre. MaTea musicians started out with traditional roots of Eritrean music, but soon developed to integrate modern musical instruments. Several Italians who stayed after the Italian colonization ended, also started giving music education to Eritreans artists who become skilled musicians of Western instruments such as violin, clarinet, accordion and fused them with indigenous instrumets irar and kebero. MaTeA was an Inclusive space where musicans from Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, Egypt and Italy, performed together and brought immense cultural exchanges and friendships. MaTeA musicians, in large part influenced through the radio broadcasts of Kagnew

Station (US military installation in asmara during the Cold War), began to incorporate American music like psychedelic rock, motown and soul. In 1974 after the brutal Ethiopian Emperor Haileselasssie was overthrown by another brutal communist military junta, MaTeA artists started to flee into exile or join the armed struggle The legacy of MaTeA and revolutionary Eritrean musicians guides the postindependence musicians. As Eritrea embarks on nation-building, music plays a major role in once again inspiring youth to socio-politico-economic development. This is the common pathway that music ought to play in the African continent as a whole. This is just a little bit of the vast history of music in a small part of the continent; one can imagine the unique, complex and astonishing music history of the 54 nations of Africa. It is in this light, that we consider the role of Art music as the troubled continent charts a new bright future, and aspire to fulfill the dreams and hopes of the many generations that passed African Art Music should African Art Music should reflect the tremendous cultural heritage of the extremely diverse and rich continent. African cultures and peoples have barely explored the immense possibilities of the already extensive musical treasure that abound. And this is in spite of the fact that modern popular music is heavily influenced and based on African rhythm, style and ingenuity. Africans on both sides of the Atlantic and beyond, have shaped what music is today. Even going back to several centuries ago, it was the North African Islamic civilizations that brought sophisticated musical instruments and music theory, along with scientific revelation to Middle ages Europe. One can refer to the Moors expansion into the Spanish peninsula and establishment Africans shouldn’t shy away from exploring all art forms, and particularly classical music. The scourge of colonial history, and the exclusivity of classical music may discourage burgeoning African artists from attempting to participate in. However, the vast canon of classical music as well as music education, can be used as a tool to explore and use African music Music has an undeniable transformative power, and just as Science is global in its nature, so is Art. In fact,the main issue is not

African restraint to go into classical music, but the racist & elitist walls created and maintained by westerners. The west doesn’t shy away from extracting and exploiting African raw resources; but when it comes to African minds and talents, the interest is nowhere. The history of African Art Music is ancient and prestigious, and this tasks African musicians with a responsibility to use art for the development and unity of their peoples. African musicians are expected to add momentum for sustainable economic growth, inclusive social justice, peace & reconciliation, and cultural rejuvenation & propagation. Music in its purest form is fostering love and understanding, empowering humanity and equality, advocating for peace and justice, and harboring respect for nature and the environment. African art music thus should focus in guiding the aspirations of Africans on their quest for a just, peaceful way of life that aims to the Pan-African values goals.

Fawad Mohammadi Afghanistan

Fawad Mohammadi Afghanistan

From the capital of Afghanistan to Oberlin, Ohio. A deep dive into the individual experience of Fawad Mohammadi and his transition to the states.

NK: So I guess my first question is what made. you chose Oberlin? Or even just choose to go study abroad internationally?

FM: Well, I usually say “coincidence” and then people look at me funny (Laughs)

NK: Coincidence?

FM: Well, I came to the states in 2013 for a specific program And then a lot of people were asking me to stay here because it was not that safe back home. But I was like, "No, I don't want to stay. If I do come, it will be for college." So I went back home and later one of my mentors told me that I could go back to the states to study abroad. So I just applied to a bunch of schools.

NK: And what was that like?

FM:Well, I did all of the SATs stuff, which is so hard back home because you don't have a center that they can help you.

NK: Really?

FM: Yeah, or you only have few people who have actually applied and got into school. So that was hard And there was like five people including me who were, applying for schools So we had to kind of divide those schools because if two people from same country apply for the same school, that'll make chances difficult So I just like applied to a bunch of schools And I got into schools in New York and a bunch of other places And when I got on Swarthmore's wait list, I actually spoke to an Oberlin admission officer here. And it was funny because I asked her, “ If you were me, what would you do?”

(Laughs)

NK: And what did she say?

FM: She told me it's better to come here! Even if I am on other schools like Swathmore wait lists. But after that I rejected all wait lists I was on. And some schools I didn't even email. Because I was like, “I’m gonna go to Oberlin.” So I took a gap semester and started late in the spring.

NK: And now you’re here! (Laughs)

FM: Now I’m here!

NK: And How has it been being a student in Oberlin Overall?

FM: Well, that’s an interesting question I think every international student is different But there are things that are especially difficult, and common For me its just getting used to normal things that an American student would do I'm a first generation student. Some of my family never even went to high school, or haven't graduated. So the only thing they could do is write and read in their own language. So for me, to just go to school in the states was a big thing. Like, I didn't even know what a syllabus was.

NK: A syllabus! I wouldn’t have even thought about it.

FM: Yes! You don’t even think about it. But its all new to me. So those things were difficult. The cultural differences are hard.

NK: Right. And have you gone back home recently?

FM: I haven't since 2021. I actually watched from far away, watched from social media, my country collapse and the Taliban took over the country And the United States was involved in that But watching all these things away from your family, from your home, from the place that you always talk about, I feel that I'm kind of representing my country Many people have never met someone from Afghanistan So, it's being that person and then seeing the country that you lived in all your life-the country that you always plan to go back to change And in your head, you realize you can’t go back. And I don't know if I will be able to go. Because I don't agree with the people who are there. Even if they have been given the government. I don't agree. And I have publicly said in my interviews that I don't agree with them. So if I go there, I don't know what will happen to me.

NK: And that has to be so difficult.

FM: It is. But then you remember some people at home cannot go to school. Girls cannot go to school.

NK: Wow. And that has to be hard in itself. And I can't imagine not being able to see your parents or have them close by

FM: And that isn’t even unique to me. When it's homecoming or when its parents' weekend, international students face the same thing Their parents cannot come.

NK: Right

FM: And I usually say that my parents wouldn't come even if they could. It's hard to come. But when seeing other people with their parents I can feel the distance from mine.

NK: And you said it yourself, this is the case with a lot of international students.

FM: Right. Even with move in day you can see international students just looking lost They don't know where to go, what to do. But then you see a national student driving a few hours or flying in with their family and they speak the same language as everyone else, so they just can ask where to go. It's a hard experience starting the transition from high school to college. Especially for international students.

NK: And then you also mentioned the cultural differences. That another thing on top of being far from home

FM: Yes exactly. Remember your comment about syllabuses? That’s with everything here. The first few days of school I remember saying “Oh my God, this is the first time I talk English every single day.” That was insane for me And I also don't understand or fit into many national college students lifestyle They talk about music in America like Taylor Swift. I listen to my own country's music Music a lot of people would not even know of. I don't fit into those situations. But I still have great conversations with a lot of people And when it comes to cultural differences for international students there are a lot of varieties

NK: What do you mean?

FM: There are International students who are upper class in their hometown But then there are international students who are first generation, who are low income So every international student has their own differences and in turn different cultural struggles.

NK: Now quick question And forgive me if I’m wrong, but is it true that International students also have different protocols and rules when it comes to protest or jobs?

FM: Yes. We have different process when it comes to most things

NK: Does that ever cause problems?

FM: Well, people are always talking about the idea of “Assimilating” in the states

NK: Assimilating?

FM: Yes, people say, “Oh, there's this thing I need to change", for example, changing your name to an america

American name in order to fit in And if you were called by that name, you wouldn’t correct someone NK: Right

FM; Because you just wanna fit in And some international students want to immerse themselves in American culture and others are like that because they're afraid of not fitting in or speaking out. Same reason for why international students are afraid of protesting. They could lose their financial aid, or they could be sent back home and a lot of other things And how would their family react to that?

NK: Right And I know that international students could be sent back home if they were arrested

FM: Yes But I try to speak up But when I am talking, it means that I'm taking a risk to be sent back. Or that my financial aid could be taken. And maybe some people's parents can pay full tuition but not only do I pay for tuition I send my parents money. That's what makes such a difference.

NK: And are there restrictions when it comes to internships and scholarships?

FM: Yes! Like I’ll see a job opening or internship and say, “oh, I'm qualified ” But then there's something that says you have to be a United States citizen. So all that qualification is for nothing. You just have to look for another thing, or be a US citizen. Scholarships too. If you see a scholarship for first gen or a minority group for example, say it's for 10 K or 5k. And you'll say ,“that's good money to take”, but then it says you have to be a citizen. So this kind of limits you

NK: It’s crazy I didn’t know any of this How can American students support their international peers?

FM: I think it's about acknowledging privilege that they have through other identities. You have these privileges and it's just acknowledging those things and saying, "Yes, I have these privileges and this is how I can help others."

NK: I think the first time I saw you was when I was talking about acknowledging my privilege by living in the States

FM: Right and you help others by doing things like writing and putting together this magazine

NK: Thank you I appreciate it (Laughs)

FM. But seriously, I think everyone can do something with their own privileges that they have. If you have power, use it and speak out. If you are a writer, write about it. If your parents have an influence on college, use it If we help each other and speak up the college will respond with us But if we don't stand up for each other, then these issues will continue to go on

NK: Thank you so much for meeting with me

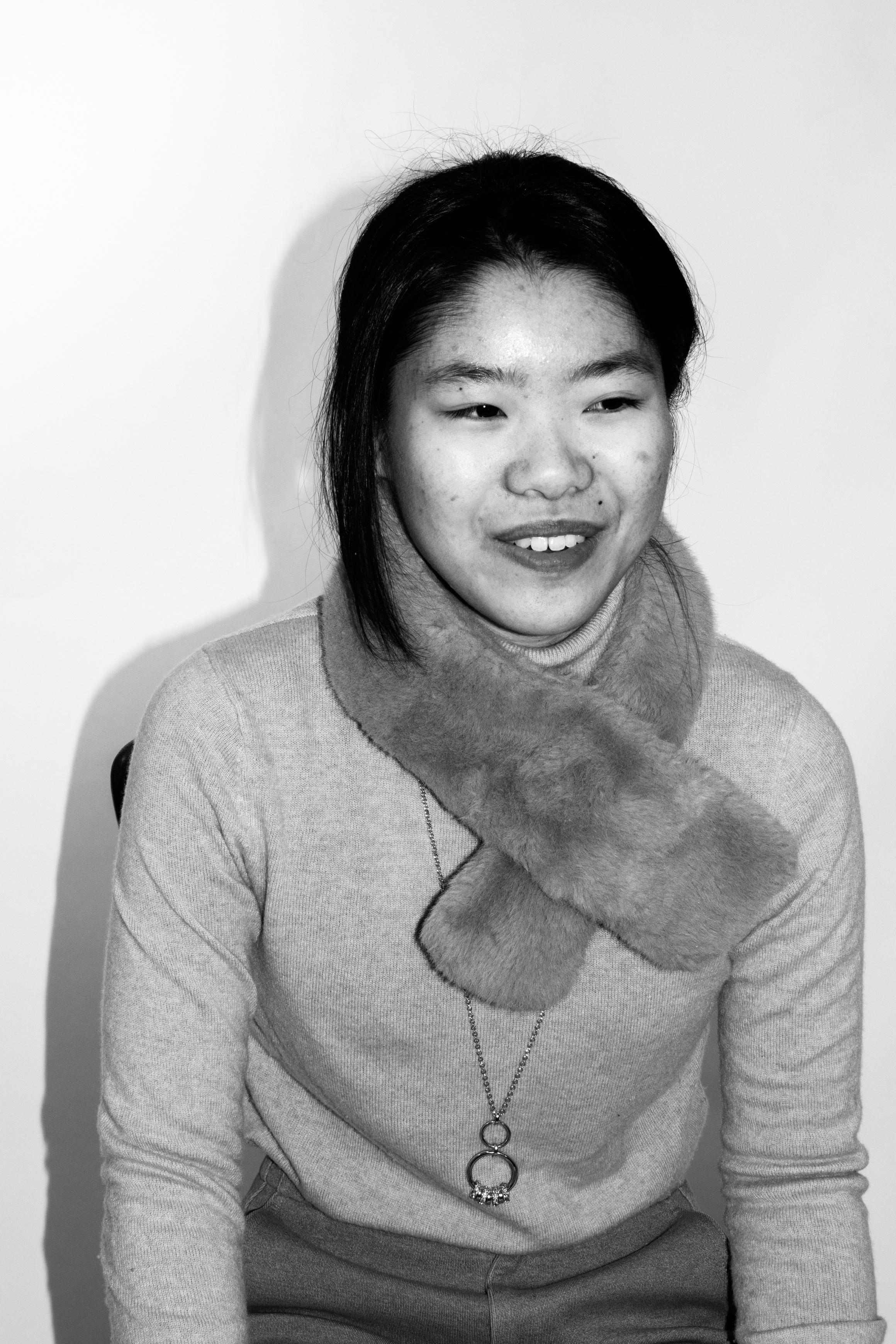

Nyakwea Ndegwa Kenya

Nyakwea Ndegwa Kenya

A EXCERPT OF THE RESEARCH ESSAY WRITTEN BY PROFESSOR ZEINAB ABUL-MAGD, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AND DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS PROGRAM

A EXCERPT OF THE RESEARCH ESSAY WRITTEN BY PROFESSOR ZEINAB ABUL-MAGD, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AND DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS PROGRAM

Under a pseudonym in December 2011, I published an article titled “al-Jaysh wa-lIqtisad fi Barr Misr” (The Army and the Economy in Egypt) in Jadaliyya. I wrote it after months of participating in numerous protests in Cairo against the government of the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF), which took power upon President Hosni Mubarak’s abdication in February 2011, and of searching fervidly for the political sources that had allowed the military to prevail over civilian forces In addition to the tanks and fighter jets, I found some of these sources hidden in a gigantic business empire that the military had clandestinely developed for years. In early 2012, the editor of an online edition of a widely read Egyptian newspaper, a revolutionary female journalist who would later be arrested and detained, invited me to write a series of articles on this business empire, this time using my real name. The first work in decades to be

published on this taboo topic, this became the foundation for my later book-length study. As a scholar, this was my humble contribution to an ongoing revolution. Ten years later, it would be nice to be able to report that the Egyptian military has abandoned its profitable business enterprises and political offices and returned to its barracks Unfortunately, the exact opposite has occurred The country’s economy has been militarized to unprecedented levels, and a new military regime has placed the entire society under close surveillance. In this essay, I do not attempt to present yet another academic analysis of what happened in Egypt over the past decade. Rather, I seek to present some observations, posted as diary en

-tries, as a surveilled citizen following a failed revolution. I do not look with total pessimism on the outcomes of the 2011 uprisings in Egypt. I believe that although the revolution failed politically, it succeeded in opening wide doors for social change and that many repressed and marginalized groups have been able to snatch some small rights here and freedoms there The secular “revolutionary youth” could not gain power for several reasons, including their lack of political experience, which allowed in part for the domination of Islamist forces over the transitional process Despite their romanticized image, many of those young rebels who called for freedom and social justice could not free themselves from inherently conservative views regarding gender, class, sect, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Sadly, too many of them were either killed during the first few months of the uprisings or later disappeared in prison cells. Despite this, great social movements have emerged, even if small, and this would not have happened without the events that began on 25 January 2011. However, when it comes to the military’s control over the economy and the state, nothing has changed Indeed, things have gotten much worse When the 2011 uprisings took place, Egyptian society had already been deeply militarized Mubarak, an ex-military pilot, had kept a civilian facade for his government but allowed fellow officers and ex-officers to function as de facto rulers of the country Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, he appointed a large number of retired generals to top administrative positions in the state’s bureaucratic apparatus, in almost every big city, small town, or village across the country. He allowed the military institution to expand

massive investments in almost every economic sector, and their concealed, untaxed, and unaudited business empire sold the consuming masses almost every good they needed to purchase or service they used in the liberalized economy. Whether managing government offices or lucrative enterprises, officers and exofficers securitized everyday life and closely watched and disciplined citizens from all social classes and in every locality. After the abdication of Mubarak, one of the main goals of the protests that continued throughout the rest of 2011 was to “demilitarize” the country, but these failed. In 2011 and early 2012, I shared with revolutionary groups actively fighting for an agenda of demilitarization every piece of data I collected about the military’s accumulated wealth and subsequent economic and political control Using academic research as a tool of resistance against the SCAF, I collaborated with three main teams of activists. The first was a youth campaign with a Facebook page, “Boycott SCAF Products,” that posted images of various brands of home appliances, canned food, cars, pesticides, pasta, etc., made in military-owned plants and urged citizens not to buy them to help financially disarm the officers. A second youth campaign called NoMilCivilPositions (La li-‘Askarat al-Waza’if al-Madaniyya) diligently compiled lists of ex-officers in top or lower bureaucratic positions and drew electronic maps locating their exact posts in Cairo and every province across the country The third was a popular street movement called The Military are Liars (‘Askar Kadhibun), which screened in open spaces videos of the army’s brutal practices against protesters. Its members incorporated information on the military’s business activities into their raw footage of tanks chasing after and spraying tear gas on protesters on side streets off Tahrir Square, and they attempted to spread political awareness of how the army's political oppression was insp

-arable from its economic domination I also wrote extensively about protests led by workers in military-owned enterprises or government employees who worked under ex-military administrators. As the military police were dispersing their strikes, I collaborated with human rights organizations and journalists to amplify the voices of

these demonstrators None of this risky activism by myself and other researchers and journalists succeeded In 2014, a new military president swept the presidential elections. Since then, military business has expanded to monopolize more key sectors of the economy, and ex-officers have seized all essential and most government positions, entrenching their control over daily life. All movements are now under surveillance. The goal is obvious: to insure that 2011 never again happens. In the age of smartphones and social media, a military regime that does not take advantage of new technologies of cyber control would not count as an efficient dictatorship As Foucault wrote in a short treatise titled Security, Territory, and Population, “defense of society is tied up with war by the fact that it is thought of in terms of ‘an internal war’ against the dangers arising from the social body itself.” If one considers the events of 2011 a war launched by the Egyptian armed forces against the lost sheep from the good citizens’ flock, then what has happened since has turned Egypt into an infinite military camp in which every citizen, rebellious or docile, is subjugated and closely surveilled. The new military regime has invented creative measures of control that penetrate deeply into the homes and bodies of its population so that they can never take to Tahrir Square again In the age of information technology, the daily tasks of managing the camp have become easier What follows are a few, random diary entries from my life as a surveilled citizen in Egypt under a new military regime. As an Egyptian who works and lives in the US, I visit my family in Cairo routinely every year and spend long months in the city. Back in the US, as an academic, the regime’s panopticon follows me to rural Ohio.

Sign outside the Lawyers Syndicate promoting the Ministry of Military Production. Photograph by the author.

Sign outside the Lawyers Syndicate promoting the Ministry of Military Production. Photograph by the author.

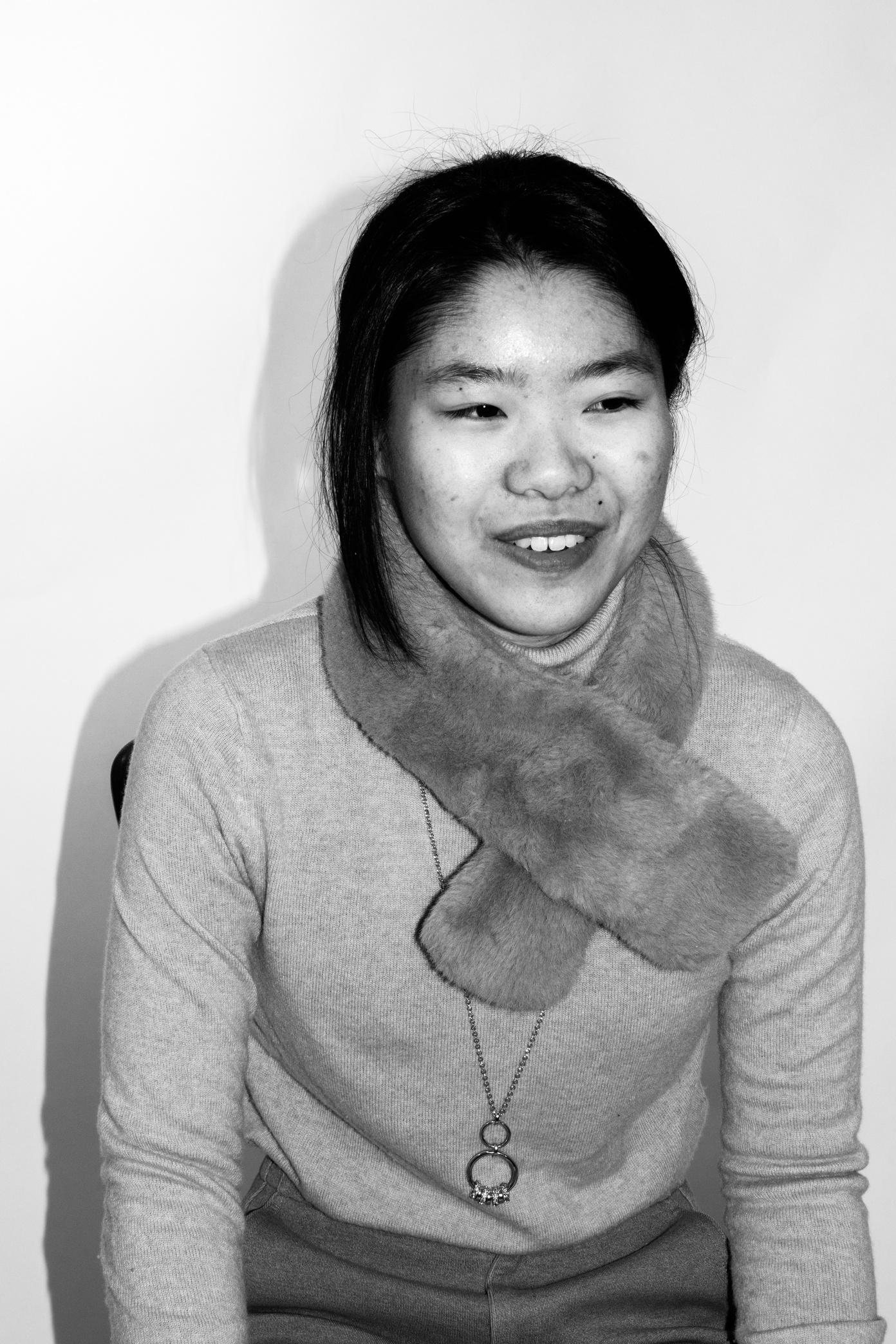

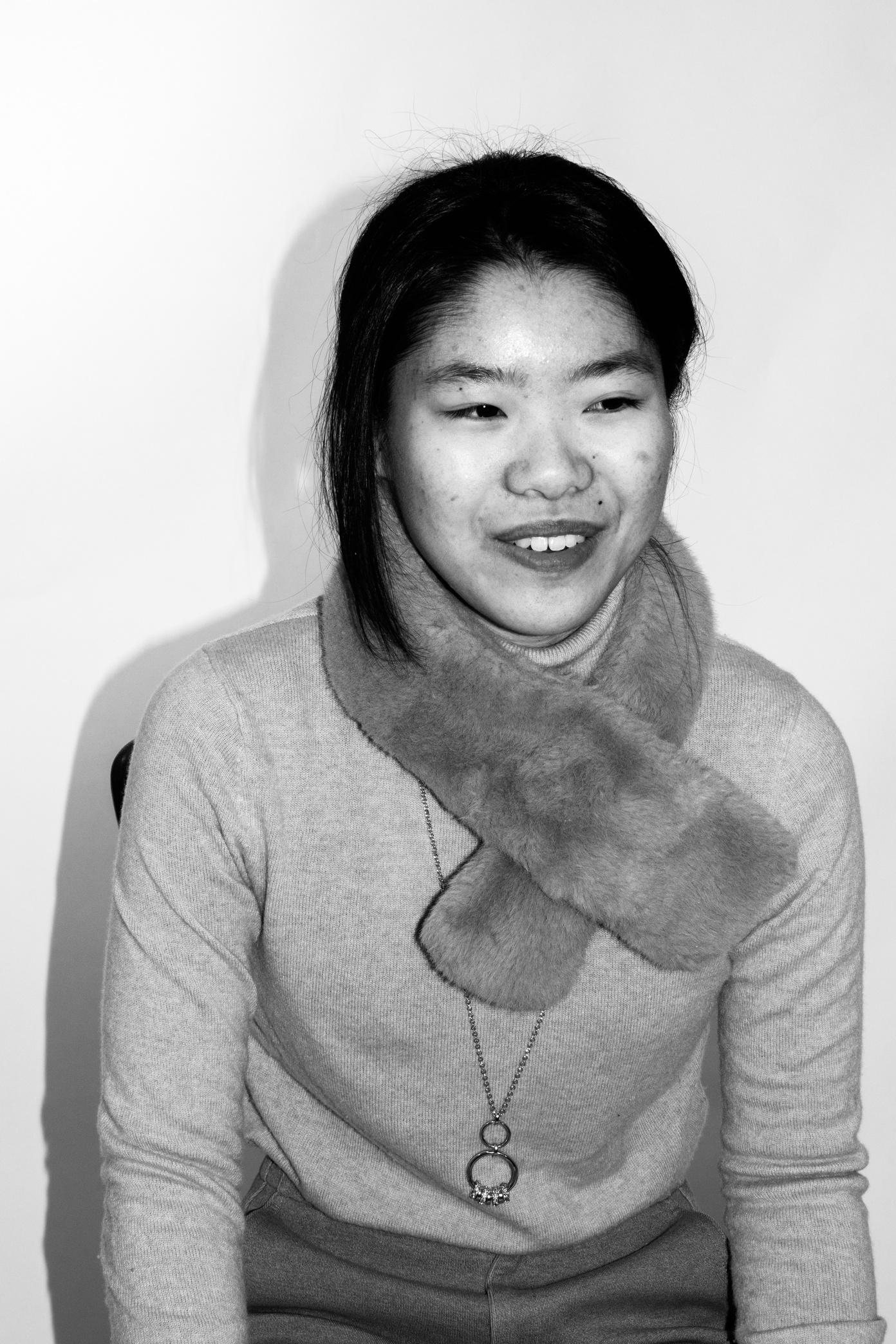

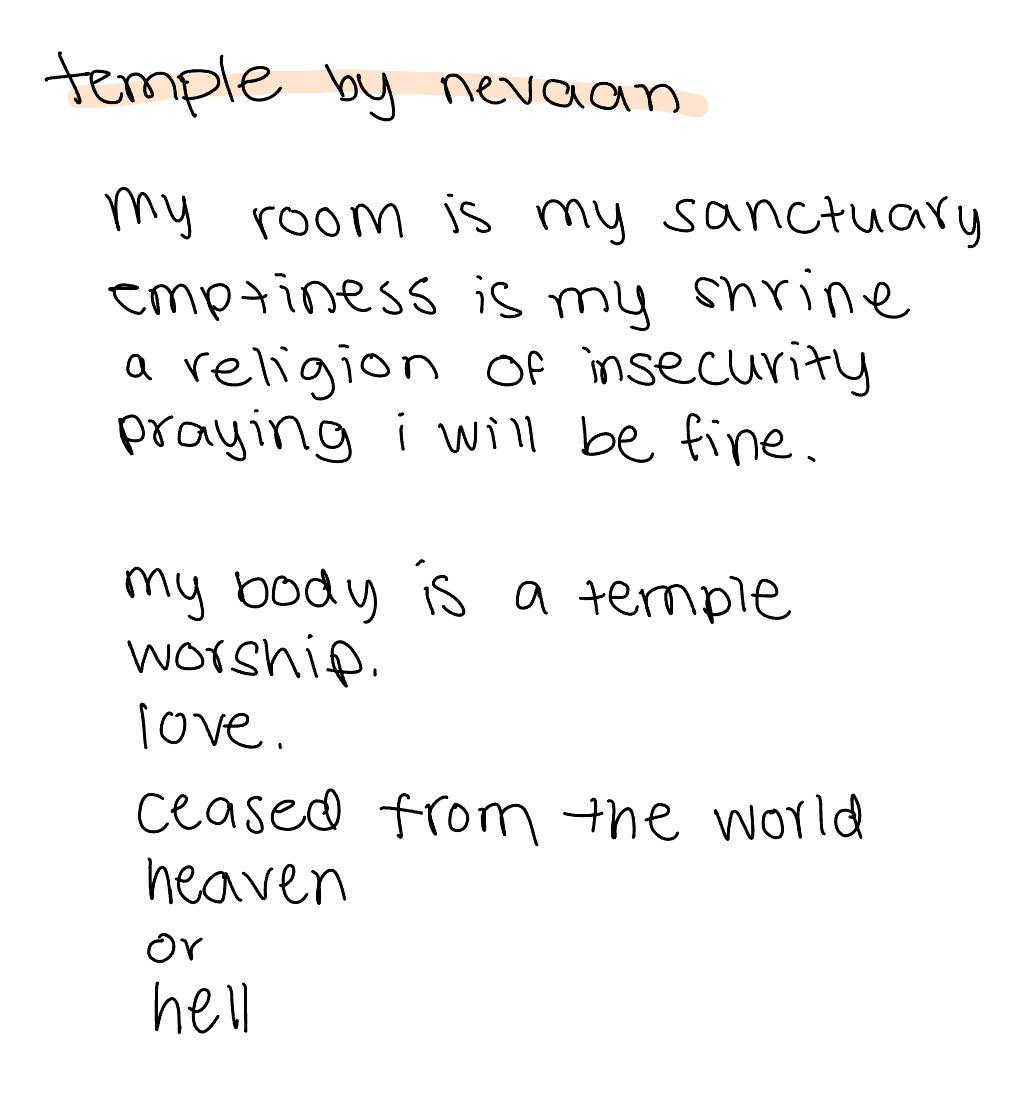

Sangeetha Ramanuj India

Sangeetha Ramanuj India

BIPOC Lenses is an Oberlin Student-run magazine that unites many different POC organizations under one publication to showcase the beauty, talent, and art that students of color create on campus.