7 minute read

Diaries of a Surveilled Citizen after a Failed Revolution in Egypt

from BIPOC Lenses Issue 3

by bipoclenses

A E X C E R P T O F T H E R E S E A R C H E S S A Y W R I T T E N B Y P R O F E S S O R Z E I N A B A B U L - M A G D , P R O F E S S O R O F H I S T O R Y A N D D I R E C T O R , I N T E R N A T I O N A L A F F A I R S P R O G R A M

nder a pseudonym in December 2011, I published an article titled “al-Jaysh wa-lIqtisad fi Barr Misr” (The Army and the Economy in Egypt) in Jadaliyya. I wrote it after months of participating in numerous protests in Cairo against the government of the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF), which took power upon President Hosni Mubarak’s abdication in February 2011, and of searching fervidly for the political sources that had allowed the military to prevail over civilian forces. In addition to the tanks and fighter jets, I found some of these sources hidden in a gigantic business empire that the military had clandestinely developed for years. In early 2012, the editor of an online edition of a widely read Egyptian newspaper, a revolutionary female journalist who would later be arrested and detained, invited me to write a series of articles on this business empire, this time using my real name. The first work in decades to be published on this taboo topic, this became the foundation for my later book-length study. As a scholar, this was my humble contribution to an ongoing revolution. Ten years later, it would be nice to be able to report that the Egyptian military has abandoned its profitable business enterprises and political offices and returned to its barracks. Unfortunately, the exact opposite has occurred. The country’s economy has been militarized to unprecedented levels, and a new military regime has placed the entire society under close surveillance. In this essay, I do not attempt to present yet another academic analysis of what happened in Egypt over the past decade. Rather, I seek to present some observations, posted as diary en -tries, as a surveilled citizen following a failed revolution. I do not look with total pessimism on the outcomes of the 2011 uprisings in Egypt. I believe that although the revolution failed politically, it succeeded in opening wide doors for social change and that many repressed and marginalized groups have been able to snatch some small rights here and freedoms there. The secular “revolutionary youth” could not gain power for several reasons, including their lack of political experience, which allowed in part for the domination of Islamist forces over the transitional process. Despite their romanticized image, many of those young rebels who called for freedom and social justice could not free themselves from inherently conservative views regarding gender, class, sect, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Sadly, too many of them were either killed during the first few months of the uprisings or later disappeared in prison cells. Despite this, great social movements have emerged, even if small, and this would not have happened without the events that began on 25 January 2011. However, when it comes to the military’s control over the economy and the state, nothing has changed. Indeed, things have gotten much worse. When the 2011 uprisings took place, Egyptian society had already been deeply militarized. Mubarak, an ex-military pilot, had kept a civilian facade for his government but allowed fellow officers and ex-officers to function as de facto rulers of the country. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, he appointed a large number of retired generals to top administrative positions in the state’s bureaucratic apparatus, in almost every big city, small town, or village across the country. He allowed the military institution to expand

Advertisement

Apartment buildings in al-Asmarat housing project. Photograph by the author.

massive investments in almost every economic sector, and their concealed, untaxed, and unaudited business empire sold the consuming masses almost every good they needed to purchase or service they used in the liberalized economy. Whether managing government offices or lucrative enterprises, officers and exofficers securitized everyday life and closely watched and disciplined citizens from all social classes and in every locality. After the abdication of Mubarak, one of the main goals of the protests that continued throughout the rest of 2011 was to “demilitarize” the country, but these failed. In 2011 and early 2012, I shared with revolutionary groups actively fighting for an agenda of demilitarization every piece of data I collected about the military’s accumulated wealth and subsequent economic and political control. Using academic research as a tool of resistance against the SCAF, I collaborated with three main teams of activists. The first was a youth campaign with a Facebook page, “Boycott SCAF Products, ” that posted images of various brands of home appliances, canned food, cars, pesticides, pasta, etc., made in military-owned plants and urged citizens not to buy them to help financially disarm the officers. A second youth campaign called NoMilCivilPositions (La li‘Askarat al-Waza’if al-Madaniyya) diligently compiled lists of ex-officers in top or lower bureaucratic positions and drew electronic maps locating their exact posts in Cairo and every province across the country. The third was a popular street movement called The Military are Liars (‘Askar Kadhibun), which screened in open spaces videos of the army’s brutal practices against protesters. Its members incorporated information on the military’s business activities into their raw footage of tanks chasing after and spraying tear gas on protesters on side streets off Tahrir Square, and they attempted to spread political awareness of how the army's political oppression was insp

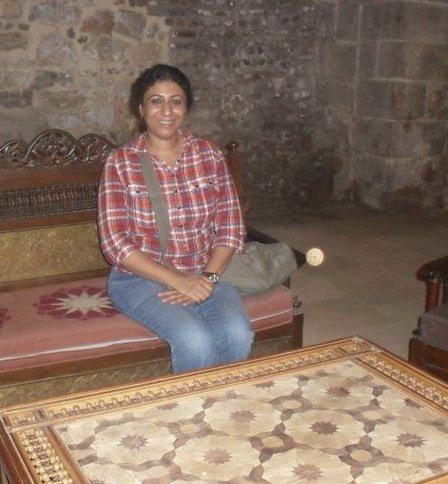

Professor Zeinab Abul-Magd in Egypt.

Want to read more? Click the QR Code for the full story

Sign outside the Lawyers Syndicate promoting the Ministry of Military Production. Photograph by the author. -arable from its economic domination. I also wrote extensively about protests led by workers in military-owned enterprises or government employees who worked under ex-military administrators. As the military police were dispersing their strikes, I collaborated with human rights organizations and journalists to amplify the voices of these demonstrators. None of this risky activism by myself and other researchers and journalists succeeded. In 2014, a new military president swept the presidential elections. Since then, military business has expanded to monopolize more key sectors of the economy, and ex-officers have seized all essential and most government positions, entrenching their control over daily life. All movements are now under surveillance. The goal is obvious: to insure that 2011 never again happens. In the age of smartphones and social media, a military regime that does not take advantage of new technologies of cyber control would not count as an efficient dictatorship. As Foucault wrote in a short treatise titled Security, Territory, and Population, “defense of society is tied up with war by the fact that . . . it is thought of in terms of ‘an internal war’ against the dangers arising from the social body itself. ” If one considers the events of 2011 a war launched by the Egyptian armed forces against the lost sheep from the good citizens’ flock, then what has happened since has turned Egypt into an infinite military camp in which every citizen, rebellious or docile, is subjugated and closely surveilled. The new military regime has invented creative measures of control that penetrate deeply into the homes and bodies of its population so that they can never take to Tahrir Square again. In the age of information technology, the daily tasks of managing the camp have become easier. What follows are a few, random diary entries from my life as a surveilled citizen in Egypt under a new military regime. As an Egyptian who works and lives in the US, I visit my family in Cairo routinely every year and spend long months in the city. Back in the US, as an academic, the regime’s panopticon follows me to rural Ohio.

How to get Involved

Join our Mailing list for Photoshoot Information, Writing/Art Submission and more!

BIPOC LENSES

BIPOC Lenses is an Oberlin Student-run magazine that unites many different POC organizations under one publication to showcase the beauty, talent, and art that students of color create on campus.