INSIDE OUT

A Partnership between City of Dublin Education and Training Board (CDETB) Education Centre in Mountjoy Prison and Mná100.

A Partnership between City of Dublin Education and Training Board (CDETB) Education Centre in Mountjoy Prison and Mná100.

We hope you find this photo-essay informative and enjoyable. This photo essay — Inside Out — was created by Mná100, in partnership with City of Dublin Education and Training Board (CDETB) teachers and students in the Education Centre, Mountjoy Prison. Together, we look to events of 100 years ago, exploring the experiences of women during our Civil War, particularly the experience of imprisonment of female political prisoners during this period. We reflect on objects and locations in Mountjoy Prison which still exist today, to assist in exploring this centenary story.

November 1922 marked the beginning of what would become the mass arrest of women who opposed the establishment of the Irish Free State. Nell Humphries and her daughter Sighle; Writer, Dorothy Macardle; Daisey Cogley; Lily O’Brennan; Bridie O’Mullane; Teresa O’Connell; Máire Deegan; Cecilia Gallagher; and former T.D., Mary MacSwiney, were among the women imprisoned for their opposition to the Irish Free State.

The Irish Civil War has had a lasting legacy on many people in Ireland and abroad — loss of life, loss of liberty and many people subsequently moving away from Ireland. In seeking to understand this time and the traumas that resulted from the Civil War, historians look anew at the accounts of those times, and uncover new material and new ways of interpretation. Some aspects of our Civil War and its legacy are only now being fully examined and discussed.

Throughout the Decade of Centenaries, we aim to look objectively at the events that took place during this period and endeavour, in a nonjudgemental and holistic way, to show the complexity of our history and the multiplicity of narratives. By doing so, we seek to explore difficult themes and find ways to appropriately commemorate this seminal period in our history.

Mná100 hopes by bringing a variety of perspectives to the fore, to help in understanding the experiences of those times and allow new voices to interpret these events.

This project builds on the work previously undertaken by the teachers and students in the Education Centre of Mountjoy Prison, as they studied this period with History Teacher Paula Egan. Collaborating with students in the art class and their teacher, Zack Sex, the students consider the projects to be their contribution to the Decade of Centenaries Programme. As Head Teacher Anne Costelloe describes:

During the Ireland 2016 Centenary Programme, a project — ‘Studying the Rising’ — was led by the City of Dublin Education and Training Board (CDETB). Then, in June 2021, a series of history panels called ‘Women and Mountjoy’ were unveiled, and at this time Governor Eddie Mullins said:

“These panels form part of a series ofvignettes that celebrate, commemorate, and highlight the historical significance of MountjoyJail during the most formative period of Irish history.”

The series is focused on the role and experiences of revolutionary women in the period leading up to the War of Independence and the Civil War, and its aftermath. The exhibition is displayed on the fence of the Dóchas women’s prison along the North Circular Road. As Governor Eddie Mullins has outlined:

“Working on this and other commemorative projects, enables prison learners to create meaningful and tangible links with the outside world, while show casing the excellent work and talent evident in the Education Centre.”

To view the exhibition Women and Mountjoy you can click here

“History has always been a popular subject among prison learners and this collaborative project reminds us that history is all around us.”

Have you ever stopped to think what a powerful weapon a key is?

It is only a simple old-fashioned mechanism, yet it can mean open sesame to love, home, friendship, or it can shut out all of these; it can mean liberty or bondage; its possession indicated individual responsibility and power, its loss strikes at the root of personal freedom, and imposes a necessity of dependence on others; lose your latchkey, and a sense of loneliness is yours on the spot…

Magnifyyour latchkey by five, multiply the result by twelve, hang them all on a steel ring, and then rattle them, and you understand a little of my feelings when the heavy door of MountjoyJail clanged to, on Little Christmas Eve, 1923, and I was a prisonerwithin its walls.

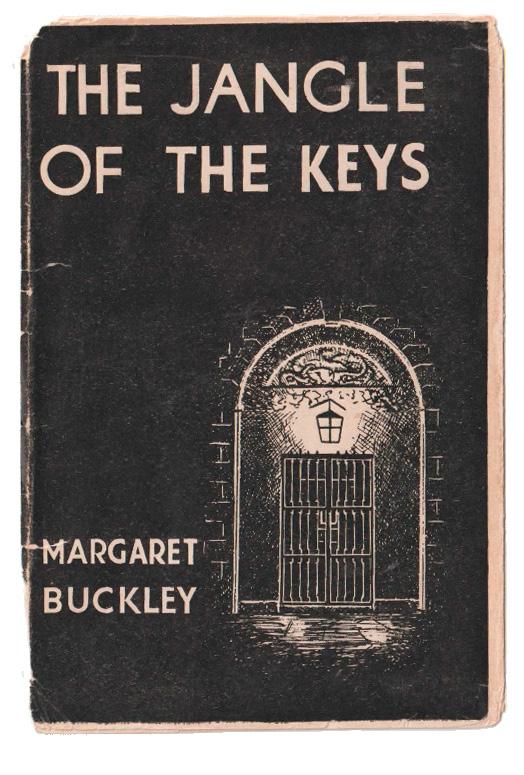

‘The Jangle of the Keys’— Margaret Buckley, ‘TheJangle of the Keys’, James Duffy & Co, 1938

As part of their work on ‘Inside Out’ students in the Education Centre in Mountjoy Prison looked at Margaret Buckley’s book, ‘The Jangle of the Keys’, James Duffy & Co, 1938 which tells the story of her imprisonment, 100 years ago:

Margaret Buckley was born Maggie Goulding in Cork in 1879. In her youth, she joined the Gaelic League, the Cork Celtic Literary Society and the Cork Nationalist Theatre Company. She also joined Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland) and served as Hon. Secretary and later as President of the Cork branch.

In 1906, she married Patrick Buckley and moved to Dublin. Widowed in 1913, thereafter she was active in the trade union movement as Secretary of the Irish Branch of the Women’s Federation. In 1919, she joined the Irish Women Workers’ Union and later she was in charge of the Domestic Workers’ Union.

After the 1916 Rising, Margaret became a member of Sinn Féin and was a judge in the Dáil courts. In 1922, she joined the Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League.

She was President of Sinn Féin from 1939 to 1950.

Margaret Buckley was arrested and taken to Mountjoy Jail in January 1923. In her book she described herself as ‘a woman of no importance’ but she had been central to the campaign of independence. Her opposition to the Irish Free State led to her imprisonment in 1923.

“Especially here where we are in Mountjoy, there’s the old triangle, goes jinglejangle.Andthatbringsmetomind a book… the fantastic History teacher up in the schoolput me onto lastyearit wasbyMargaretBuckley.Thebookwas called the… ‘The Jangle of Keys’ was the name of the really good book and theladywasinprisonhereshewasalso the first female president of Sinn Féin.”

In Mountjoy Jail in November 1922, 17 female political prisoners were imprisoned for their opposition to the Irish Free State.

On 10th November, Sinn Féin’s offices at 23 Suffolk Street were raided and all of the staff were taken to Mountjoy Jail. Lily O’Brennan wrote to her sister, Áine, that she was taken from ‘23’ after a raid on the premises at 5 o’clock that evening.

Lily lists those who were also taken as Mrs Cogley (also known as Madame Bannard), Miss Macardle, Miss Birmingham, Miss Devaney, and Tessie O’Connell. She stated that they were brought to Portobello Barracks first and at about eight o’clock that night were transferred to Mountjoy Jail.

Mother and daughter, Nell and Sighle Humphreys, were already there, following a raid on their home on 4th November. Nell’s sister, Anna O’Rahilly, who was injured, was brought to hospital and imprisoned later. Mary MacSwiney had also been arrested that day in the home of their relative, Nannie O’Rahilly, widow of their brother Michael. Nan was held briefly, went on hunger strike and was subsequently released.

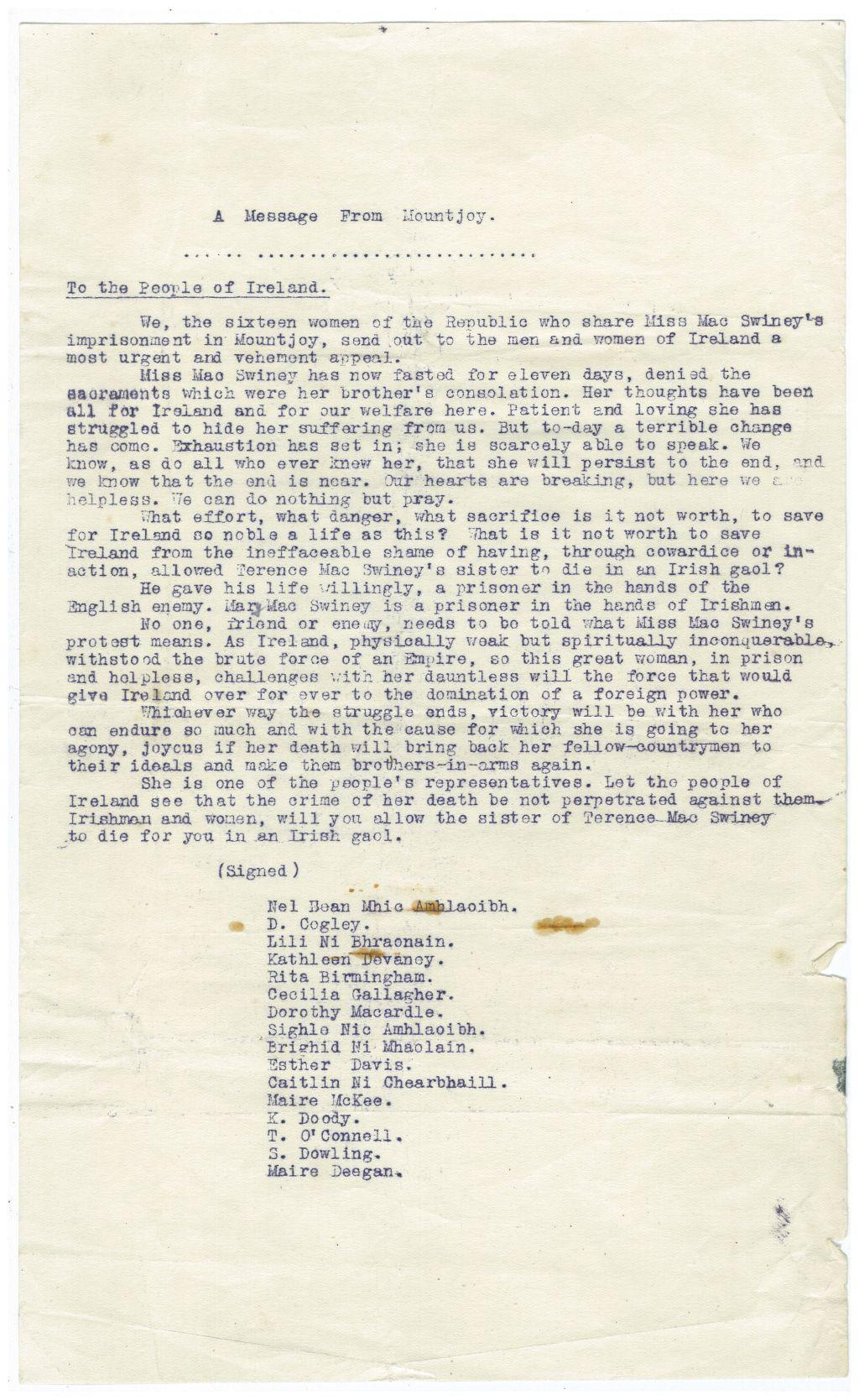

When Mary MacSwiney was brought to Mountjoy Jail, she immediately went on hunger-strike. Eleven days later, on 15th November, Mary MacSwiney’s fellow prisoners, describing themselves as “sixteen women of the Republic” issued a “most urgent and vehement appeal” on her behalf:

‘What effort, what danger, what sacrifice is it not worth to save for Ireland so noble a life as this?’

Those who signed the message were Nel Bean Mhic Amhloibh (Nell Humphreys), D (Daisy) Cogley, Lili Ni Bhraonain (Lily O’Brennan), Kathleen Devaney, Rita Birmingham, Cecilia Gallagher, Sighle Nic Amhloibh (Sighle Humphreys), Brighid Ni Mhaolain (Bridie O’Mullane), Esther Davis, Caithlin Ni Chearbhaill (Kathleen O’Carroll), Maire McKee, K Doody, T. (Teresa) O’Connell, S. (Sighle) Dowling, and Maire Deegan.

In Mountjoy Prison Chapel, (formerly part of the Women’s Prison), there are three stained glass windows, commissioned by Nell Humphreys, a former prisoner, and designed by Richard King of the Harry Clarke Studios in 1939. At the time of their installation, the windows were dedicated to the women of Cumann na mBan.

Members of the History Class discuss the commissioning of the window by this former inmate:

“I think the glass was done by Harry Clarke, but it was commissioned by Nell Humphreys... and Nell Humphreys was actually imprisoned in Mountjoy female prison, so that’s really, for me, I think it’s really interesting that Nell Humphreys, after being here like, we are, leaves, and then commissions like a really famous stainedglass artist to come in and do something that she’s not even going to be able to appreciate. Then as far as I knowwe were told that she died before it was finished. So I dunno, it says a lot for the character of Nell Humphreys, in my opinion.”

Click here to Listen to Audio

Courtesy of Irish Prison Service

In March 1939, Nell went to the Harry Clarke Studios on North Frederick Street and placed an order for the windows for Mountjoy Jail. By then the founder of the studio had died but the work created by his studio carried the hallmarks of his individual style. In correspondence seen by Margaret Ryan — who has written and researched extensively on the commissioning of these windows — Nell wanted the image of the central window to resemble as closely as possible the original icon of the Mother of Perpetual Succour.

Three months later, Nell died on 8th June 1939, so she did sadly not live to see the windows installed in October of that year.

Mary Ellen Humphreys, known as Nell, and her daughter who was also named Mary Ellen but always known as Sighle, were arrested in their home at 36 Ailesbury Road, Dublin, in November 1922. They were amongst the first of hundreds of women detained during the Irish Civil War. Anna O’Rahilly, Nell’s sister, had been wounded during the raid and after a time recovering in hospital, she too was incarcerated.

Nell had been widowed in 1903 when her three children, Richard (b.1896), Sighle (b.1899) and Emmet (b.1902), were very young. From 1909, the Humphreys family lived in Dublin and all became involved in activities of cultural revival and nationalist politics. Nell’s brother, Michael, known as the O’Rahilly, had been killed in the fighting during the 1916 Rising. During the Rising in 1916, Nell brought medals of the Mother of Perpetual Succour to the GPO for the rebels. She also brought her son Dick home with her. He said

it was more dangerous on the road home than in the GPO. Identified as a sympathiser, Nell was arrested and imprisoned during the Rising.

Nell continued her devotion to the Mother of Perpetual Succour, distributing medals to those active in the subsequent years of fighting. In 1923, the image of the icon was used outside and inside of Mountjoy Jail. Nell organised prayer vigils during her time in prison, including some all-night vigils. As one of the more senior women who took on official roles in the prison using military terms, she became affectionately known by her fellow inmates as ‘Officer Commanding God’ and ‘Officer Commanding Prayers.’ Following her period in Mountjoy Jail, she was imprisoned in Kilmainham Jail and later in the North Dublin Union. She was released in July 1923.

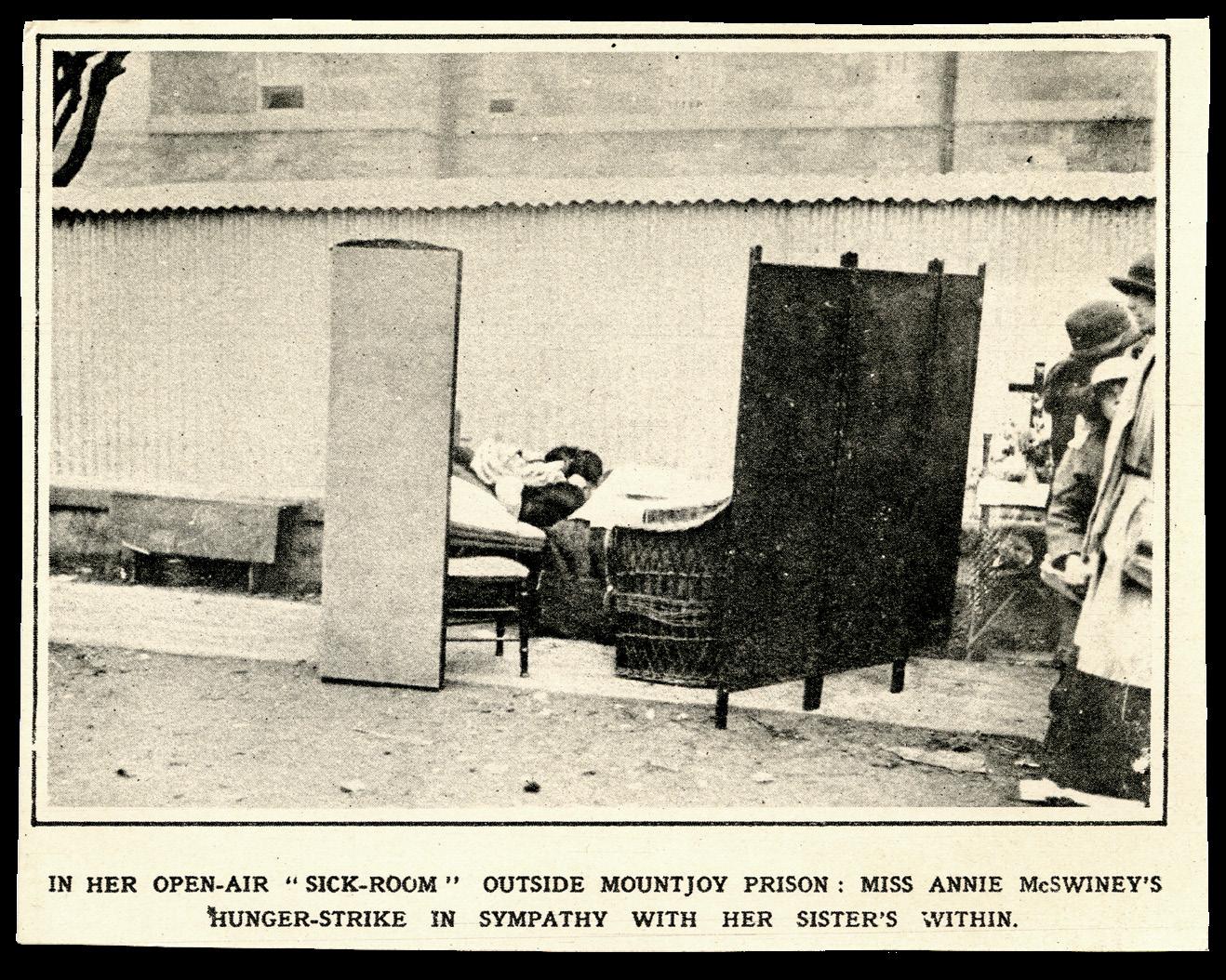

Prohibited from visiting her sister Mary, Annie MacSwiney joined her sister on hunger-strike outside Mountjoy Jail on 17th November 1922. Annie MacSwiney (1884-1954) was a science graduate and became a teacher of Maths and English. In 1914, she worked on the Isle of Wright before returning home. Along with her sister Mary, they set up Scoil Íte in 1916 — the only lay school in Cork — in their home at 4 Belgrave Place.

In November 1922, Annie was described as occupying an ‘open air sick room’ as partitions were erected around her at the front of Mountjoy Jail. As Annie described, she was:

“Fasting night and day in protest against such callous brutality as the world has never heard of – shutting me out from my dying sister… No criminal in the land in the world is denied the right to see his people and settle his affairs before death.”

In a letter dated 27th November 1922 headed ‘outside Mountjoy’ she wrote: ‘...If either or both of us die, our blood will be upon your head. You may say I am not in prison, but I am imprisoned by their torturing inhumanity, and I shall never be released until that prison is opened. Do not imagine my sister or I fear death.’

Mary MacSwiney refused to be attended to by doctors and nurses, in protest at the exclusion of her younger sister. On 24th November, after 20 days on hunger-strike, Mary MacSwiney was given the last rites. Four days later she was released, and returned home with her sister.

Mary MacSwiney lived for another 20 years remaining in continuous opposition to the Irish Free State. She and Annie continued to run Scoil Íte. It closed in the year of Annie’s death in 1954.

Execution… the most extreme form of punishment. In 1868, public executions were banned with the passage of the Capital Punishment Act. The Hang House in Mountjoy Jail is thought to be a building that may have originally served another purpose, which was then adapted for use for executions from 1901 to 1954.

During the campaign of independence, eighteen-year-old Kevin Barry was hanged in November 1920. During 1921, Thomas Whelan (22), Patrick Moran (26), Patrick Doyle (29), Bernard Ryan (20), Thomas Bryan (22), Frank Flood (19), Thomas Traynor (40), Patrick Maher (32), and Edmund Foley (23) were executed in Mountjoy jail. Patrick Moran had a chance to escape from prison but did not take part, believing his innocence would be proven. Thomas Whelan also claimed he was not guilty. His mother came from Galway to be outside the prison where she was photographed with Maud Gonne MacBride. Kate Whelan said of her son:

“He was loved by everyone in Dublin that knew him and especially the people of Ringsend his whole leisure time he spent in practising singing… The night before his execution he sang the ‘Shawl of Galway Grey’.”

On 8th December 1922, the women prisoners would have awoken to the news that their fellow inmates — Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellowes, Joseph McKelvey and Richard Barrett — had been executed, as a result of the shooting of Seán Hales T.D. Labour Leader, Tom Johnston, spoke in Dáil Éireann later that day, using a quote from William Shakespeare’s Othello: “Horrors upon horror’s head accumulated”. He also mentioned that it had been just two days after the ratification of the Treaty and the formalising of the Irish Free State.

As part of the work on ‘Inside Out’, the History Class of Mountjoy Education Unit gained special permission to visit the Hang House, at the end of D wing. Subsequently, the in-classroom discussion was recorded:

“Upon entering the hang house, I dunno, it was like something akin to going into like a funeral home… it was just like a reverence in the air, and it was like, I dunno, an eerie feeling. That’s how I felt, how did you feel?

“Yeah I got the same. It’s like the smell, the musty smell and yeah. I just got goose pimples when I walked in… it got that weird feeling like you were walking into a wake or like a funeral home or something. Yeah, yeah I was the same, I was the same.

“I never even knew it was there. It was only then I was got brought to it, I was like woah, like there was fellas who were staying where I was staying but theywere getting brought from the cell to the hang house to be executed.

“Yeah, I, I never even knew that it was at the end of D wing so same thing for me I would’ve been placed not far from that actual hang house, at one stage through me sentence. So it’s just mad to think that, yeah, it was just so close, you knowwhat I mean?”

Click here to Listen to Audio

Tim Carey described in his history of the prison: “Mountjoy Jail closed its doors for the first time.”

—Sean Milroy, in his book ‘Memories of Mountjoy’, published in Dublin in 1917.

The prison on the northside of Dublin city was opened for the first time on 27 March 1850 or as

In 1849, there were 115,871 people imprisoned in Ireland, according to the Inspector General’s report. Mountjoy Jail was originally constructed as a prison for criminals sentenced to transportation but soon it became used as a convict prison.

In 1914, the annual prison population was, according to Carey, just over 10,000. In Ireland, there were, along with Mountjoy Jail, Maryborough Jail (now Portlaoise), fourteen local prisons, one borstal, which opened in Clonmel in 1906 for the punishment and reform of 16- to 21-year-old males, one inebriate reformatory for “habitual drunkards” (opened following the Inebriates Act of 1898), and also five Bridewells for petty offenders.

In 1883, women who had been imprisoned in Mountjoy Jail were moved out to other prisons. By 1897, they were back and housed in a women’s prison within the complex. Mountjoy Jail had become a local prison for Dublin.

In the period that followed, Mountjoy Jail became very identified as a place of incarceration for political prisoners, both men and women. During the Irish Civil War, it became one of the locations of detention for women who opposed the Irish Free State. In 1922 and 1923, there were over 500 women imprisoned - their places of detention were Mountjoy Jail, Kilmainham Gaol (which was a disused prison for several years when it was used as a place of detention for ‘suspect women’), and the workhouse of the North Dublin Union.

”Palace of Bolt and Bars – don’t forget to take your imagination with you when you go oryou are in for a devil of a time.”

By the early months of 1923, conditions became overcrowded in Mountjoy Jail as more women prisoners arrived. Within weeks of the arrival of Margaret Buckley, Margaret Skinnider (1893-1971) arrived. Originally from Glasgow, she was a wellknown activist, having taken part in the 1916 Rising as a member of the Irish Citizen Army when she was badly wounded. In 1917, she travelled to the United States to undertake a speaking tour. Her book, Doing my bit for Ireland, was published in New York. While teaching at the Sisters of Charity School, Kings Inn, she was active in the campaign of independence. She opposed the Treaty and held the position of I.R.A. Paymaster General at the time of her arrest.

As numbers increased, the prison authorities began to put two women in cells designed to hold just one person. When the new bedding arrived, the women political prisoners began to throw the bedding on to the landing. If a bedstead was placed in one of the larger rooms, this was wheeled back out by the prisoners (who had freedom of movement) and it was put in the corridor.

This was something that was discussed by the History Class:

“Another thing we found out that when the ladies used to be protesting, they used to throw all their stuff from their cells including the beds out on to the landing.”

May Lagan arrived in the middle of the night and got into bed in the corridor. Her bed was located beside the altar and when she awoke, she was surrounded by women praying the rosary. Her immediate thought was that she had died, according to Margaret Buckley’s account in ‘The Jangle of the Keys’. For long after the story was recalled as “May Langan’s wake.”

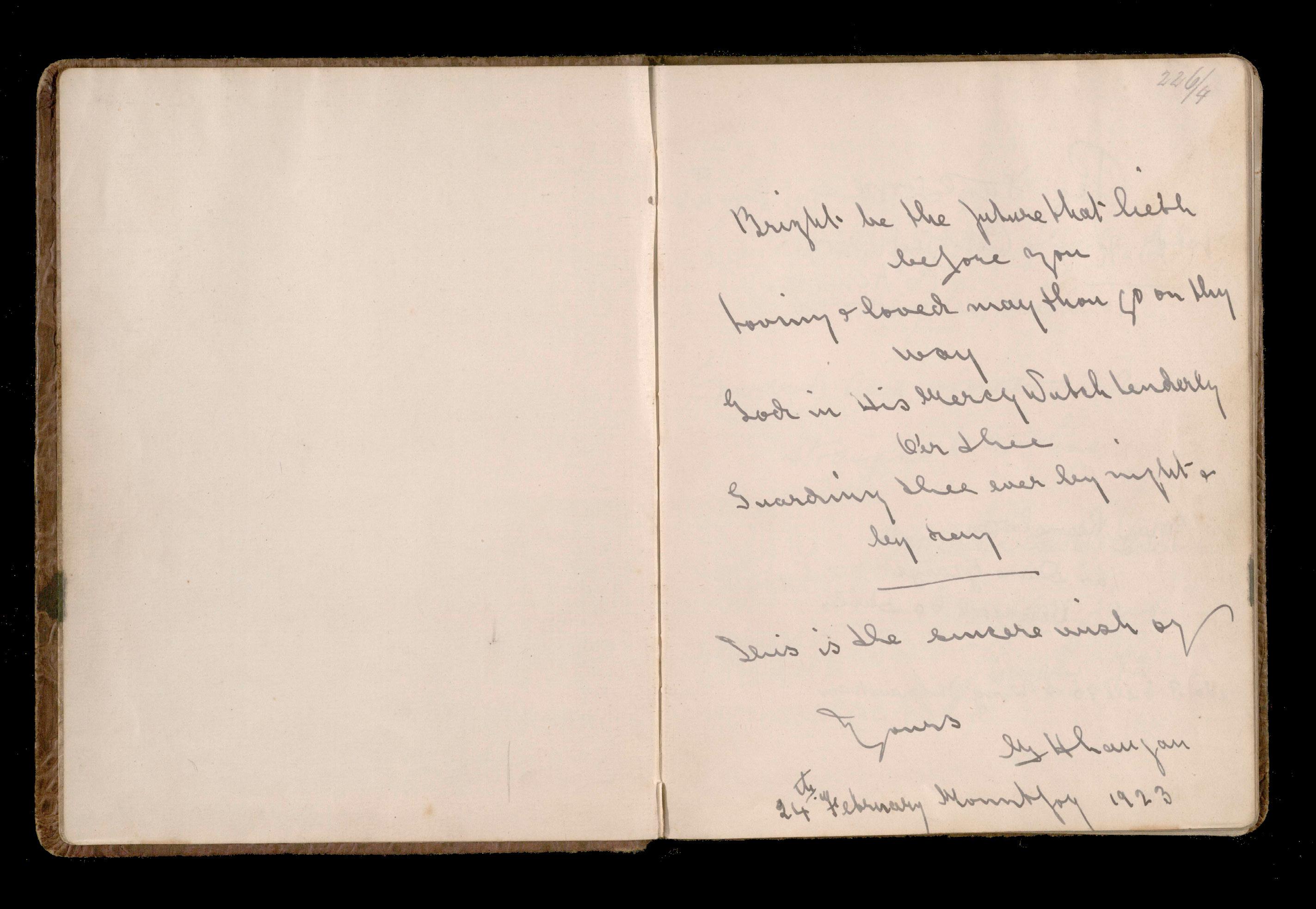

Autograph Book inscription from Mary Langan with signatures of prisoners from Mountjoy Prison, North Dublin Union and Kilmainham Gaol 1923:

Bright be the future that lieth before you

Loving and loved may thou go on thyway

God in his mercywatch tenderly over thee

Guarding thee ever by night and by day

This is the sincerest wish by Yours M H Langan 24th February Mountjoy 1923

This new initiative from Mná100, in partnership with City of Dublin Education and Training Board (CDETB) teachers and students in Mountjoy Prison, seeks to highlight the role and experiences of women in the transformative events which took place from 1912-1923, the period we are now remembering in the Decade of Centenaries. In this photo essay, we have illuminated the stories of well-known and some not so well-known women who were imprisoned during this time.

“The importance of prisoners’voices — both past and present — being heard, lies at the heart of this History project. By allowing prisoners’words and creative work to filter from the inside to the outside, walls, which previously silenced and separated, can become sites of learning and reflection. Considering the role played by prison and prisoners in the birth of the State, it is fitting that prisoners from Mountjoy Education Centre can contribute towards the Decade of Centenaries Programme.”

- Paula EganMargaret Buckley, Civil War Prisoner Pg. 4

Information from Dictionary of Irish Biography

’50 Years Ago – Margaret Buckley, President of Sinn Féin, Saoirse, July 1998

Obituary, Irish Independent, 25 July 1962

Uinseann MacEoin The I.R.A. in the Twilight Years 1923-1948. Dublin, Argenta, 1997

Women Political Prisoners Pg. 5

Sinéad McCoole, No OrdinaryWomen, The O’Brien Press, 2003

The MacSwiney Sisters HungerStrike Pg. 9

Máire MacSwiney Brugha History’s Daughter, The O’Brien Press, 2005.

A Message from Mountjoy on behalf of Mary MacSwiney’ 20 MS-IB42-06, Kilmainham Gaol Museum (see page 6) Executions, Mountjoy Jail Pg. 10-11

Tim Carey, Hanged for Ireland, the Forgotten Ten, Blackwater Press, 2001.

Dáil Éireann Debates - https://www.oireachtas.ie/ en/debates/debate/dail/1922-12-08/9/

Nell Humphrey’s, Civil War Prisoner Pg. 6-8

Margaret Ryan, ‘A Woman of 1916 and Our Lady of Perpetual Succour’ Reality May 2016

Margaret Ryan, ‘Second Glance: Nell Humphreys and the Mother of Perpetual Succour’, History Ireland, Volume 29 January/February 2021, May 2016

Palace of Bolt and Bars Pg. 12

Tim Carey, Mountjoy The Story of a Prison, The Collins Press, 2000.

Christina M. Quinlan, Inside Ireland’s Women’s Prisons, Past and Present, Irish Academic Press, 2010.