THE BERKELEY CARROLL SCHOOL VOL53, ISSUE1, 2024

Sunspots

Grade 12 ,

THE BERKELEY CARROLL SCHOOL VOL53, ISSUE1, 2024

Grade 12 ,

Reflections, the annual literary and arts magazine of the Berkeley Carroll Upper School, seeks to tap the vibrant, creative energy circulating in the classrooms and hallways of our school. Berkeley Carroll’s mission is to foster an environment of critical, ethical, and global thinking; Reflections contributes by making space for artistic conversation and collaboration, in our meetings and in this volume.

What’s in a name? “Reflection” implies both a mirroring and a distortion: something recognizably strange and strangely recognizable. In selecting and arranging the visual and written work in this magazine, we seek to create this experience of broken mirrors: reflections that are just a bit off, refracted, and bent to reveal unexpected resemblances. Notice, for example, Nico G’s “Pantheon Angel” striding forth from the end of Avi K’s “Ruminations of a Physarum Polycephalum. ” While our first thought might be that a fierce divine messenger would have nothing in common with a sentient slime mold, as we edited the magazine we chuckled as we noticed the two of them united in their bold visions and sense of purpose: the angel with scepter raised, the physarum polycephalum certain that they “have been placed here to preside over it all.” We hope that, as you page through the magazine, you will notice many similar odd connections.

The Reflections staff is a small, dedicated group of students that meets biweekly over Pop Corners, wasabi peas, and cutting-edge Oreo flavors to discuss and develop a shared interest in art and literature. In the fall, Reflections members establish the magazine’s high standards, solicit submissions, and refine their own works in progress. In February, the editors preside over small groups who read and critique anonymous student art and literature submissions. After the preliminary critiques—and with helpful suggestions from the art department—the editors carefully consider feedback from the entire Reflections team before choosing and editing the final selections and laying out the magazine, including selecting and designing the spreads. Editors then submit all materials to our fantastic printer, review the proofs, and distribute copies of our beautiful magazine—through our library, as summer reading for our writing courses, at admissions events, and to anyone lucky enough to find the PDF on our school website.

Reflections is a student-run, -led, and -organized coterie; neither the editors nor the staff receive class credit for their work. We are proud members of the Columbia Scholastic Press Association. The striking artwork and writing in this magazine were all crafted by Berkeley Carroll Upper School students, sometimes to fulfill class assignments, but always from the engines of their own creativity.

At Reflections, our layout process is old-school. We like to move words and images around on paper until everything looks right.

Staff

Editors-in-Chief

Avi K

Devra G

Arts Editor

Max M

Faculty Advisors

Ms. Drezner

Mr. Gavryushenko

Staff

Aarju F

Alexis SG

Amelia L

Elle C

Elsie W

Welcome to the fifty-third edition of Reflections! This beautiful volume that you’re holding in your hands is made up entirely of art and writing created by our own BC Upper School community, and it’s the culmination of weeks and weeks of hard work. The Reflections staff spent the spring laying out hundreds of little pieces of paper on the ground every day after school— ordering and re-ordering, pairing and re-pairing, scribbling and re-scribbling. This book is made up of both the challenges that we overcame as a team and the joy we found in spending time with one another. There is no one without the other; this coexistence is the magic of creation.

Hannah H JP L

Veronica M

Tessa G

Ula K

This year’s Reflections would not have been possible without our faculty advisors, Ms. Drezner and Mr. Gavryushenko; our talented designer Bob Lane at Studio Lane; and the support of our faculty in the Art and English departments. And of course, Reflections would be blank without the thoughtful writing and intricate artwork that is shared with us each year.

Every spring, Reflections finds new ways to harness the creativity and passion at the heart of the Berkeley Carroll community. This is this year’s endeavor. We hope that you love it.

Devra G, Avi K, Max M

Editing Team, Spring 2024

P OETRY

10 Sylvia AVI K, Grade 12

21 What This Is Really About MAX G, Grade 12

32 no just verbs for this traffic jam DEVRA G, Grade 11

38 Untitled: Today It’s Misting HANNAH H, Grade 9

53 Dreams of the Horizon DANIEL E, Grade 11

61 far-out cities

ELSIE WM, Grade 9

73 The Gale Force

ELLE C, Grade 9

78 she wants to be naked DEVRA G, Grade 11

92 Sueños (to Ana Maria Tigre) JAZEERA A, Grade 11

98 Trespasser ALEXIS SG, Grade 11

100 Elegy for Grandpa: Missed Opportunities

ELIAS D, Grade 9

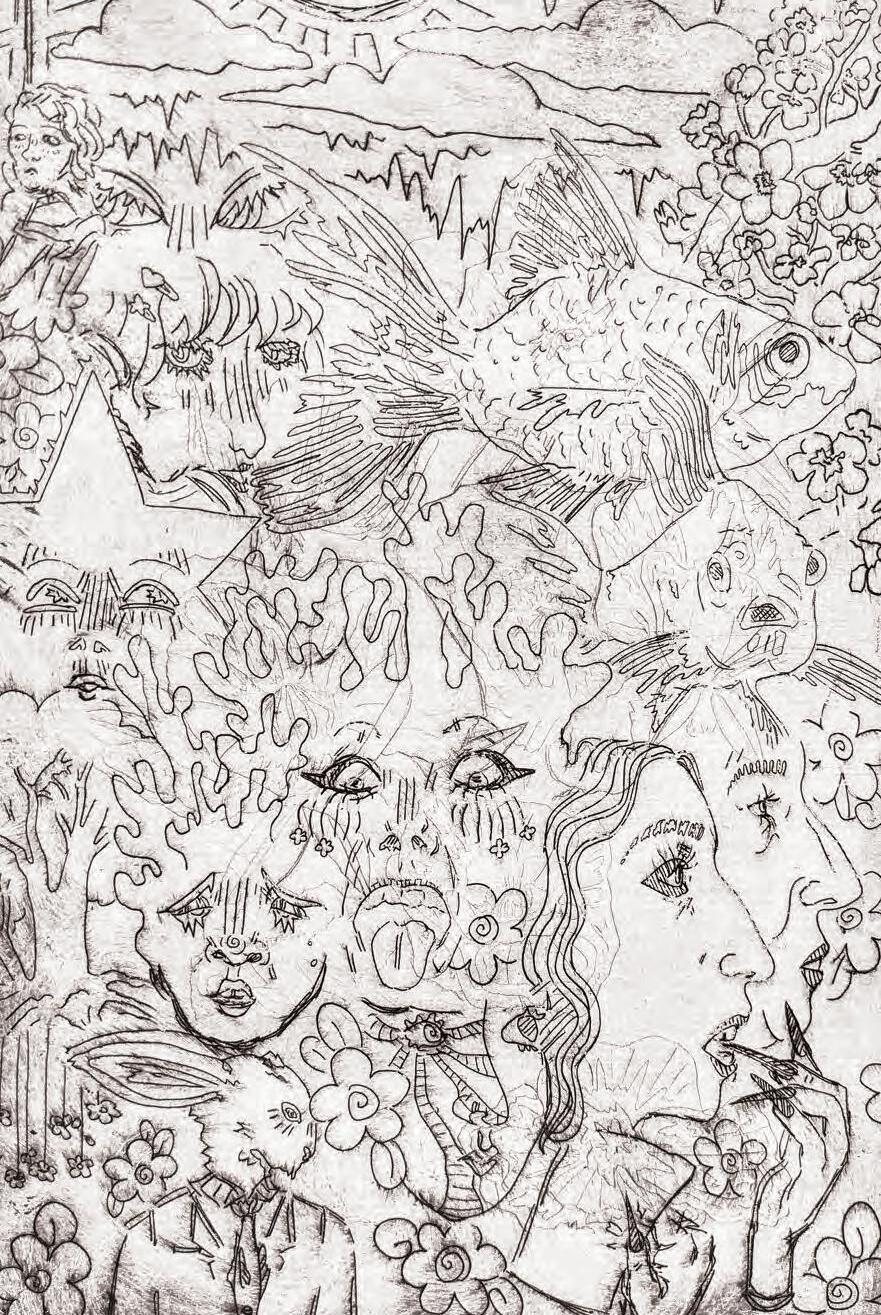

Fish !!

ULA K Grade 11 , Screen Print

106 To My Grandfather, My World SARAH K, Grade 12

112 Golden RILEY H, Grade 9

13 Parabola

ROSE H, Grade 12

17 Arrival to the Year

MATILDA F, Grade 11

30 Unconditional Hand-Me-Downs

AMELIA L, Grade 12

35 The Girl with the Prettiest Smile

GURLEEN K, Grade 10

41 Losing at Le Dock

WYATT B, Grade 12

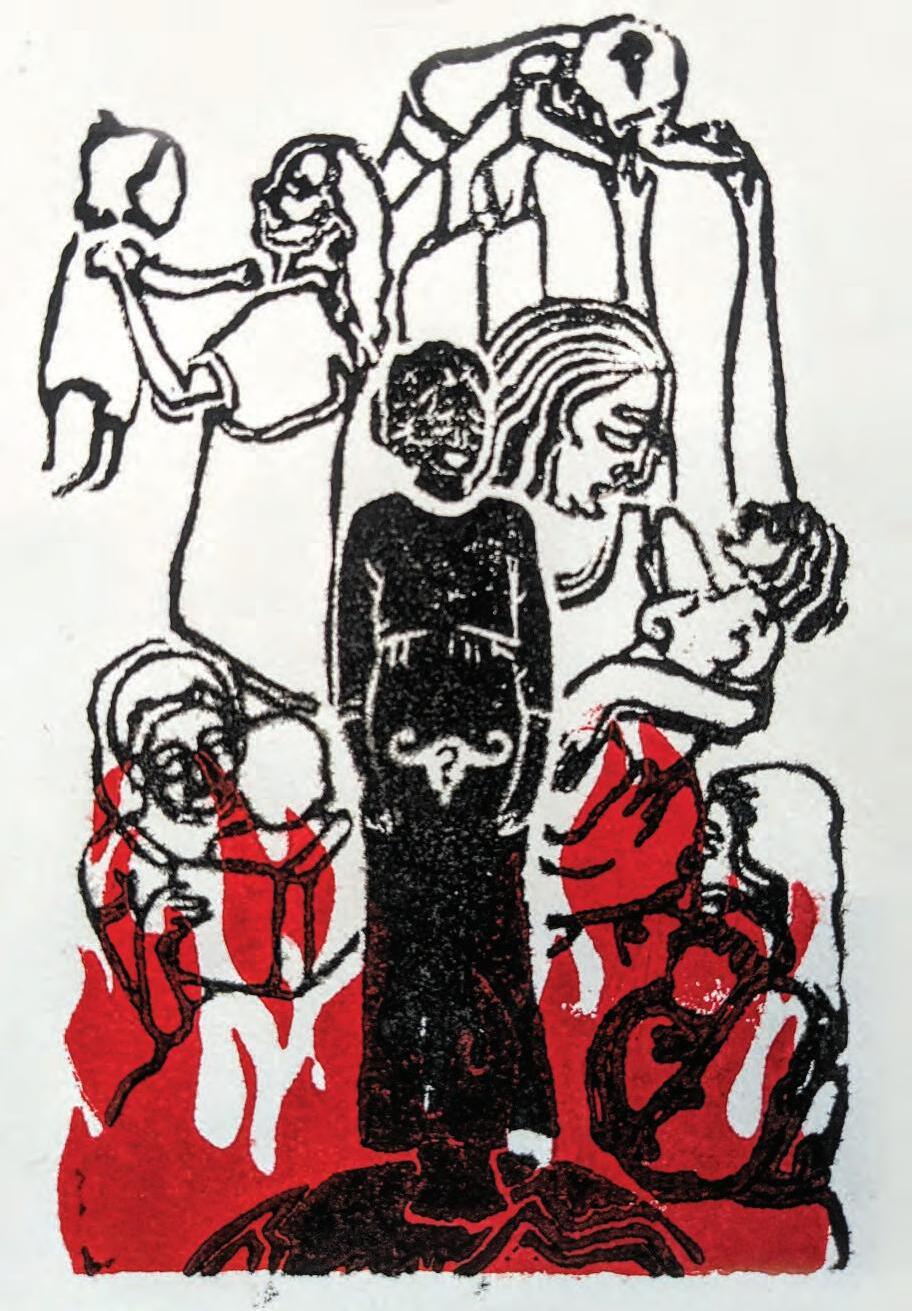

57 A Hair Oil Massage is Culture

AMAN K, Grade 12

62 A Letter to an Absence of Joy

JACQLENE S, Grade 12

74 What’s Next?

RACHEL O, Grade 12

81 Ye Olde Hipster in Ye Newe Zaragoza

MATILDA F, Grade 11

85 Fluoropolymer

MULAN J, Grade 12

102 How to Push a Wheelchair

AMELIA L, Grade 12

108 Walking in the Sunlight

BASANT K, Grade 12

67 Ruminations of a Physarum Polycephalum

AVI K, Grade 12

95 A Guide to Older Sibling ing from an Older Sibling, for Older Siblings

LEE R, Grade 12

115 Airborne

DEVRA G, Grade 11

(continue d)

39 Seeing Double

LUCIA R, Grade 10

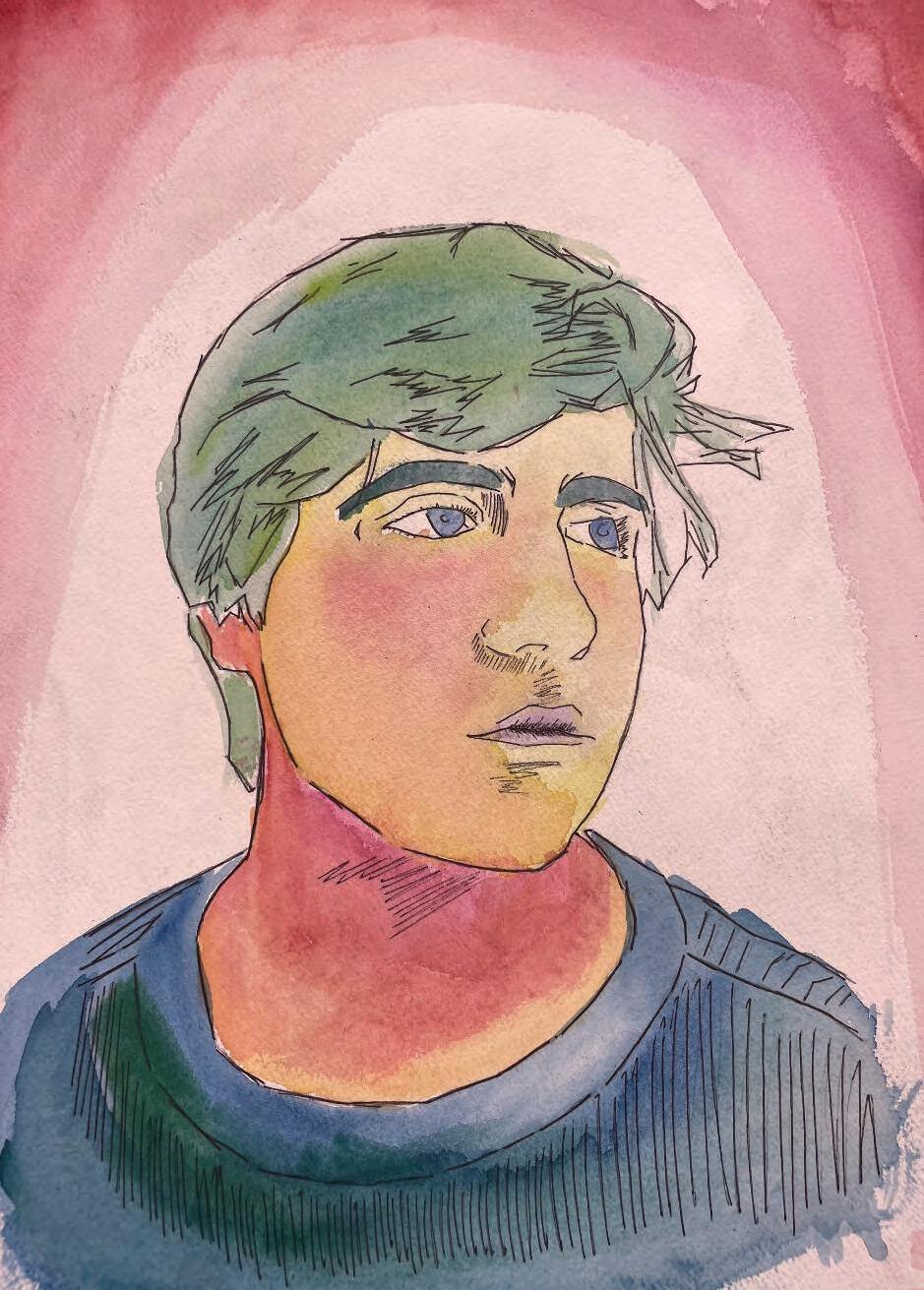

40 Self-Portrait: Entry

RAFA B, Grade 9

45 Fata Morgana

AARJU F, Grade 10

47 Do What Makes You Scared

CLEO L, Grade 10

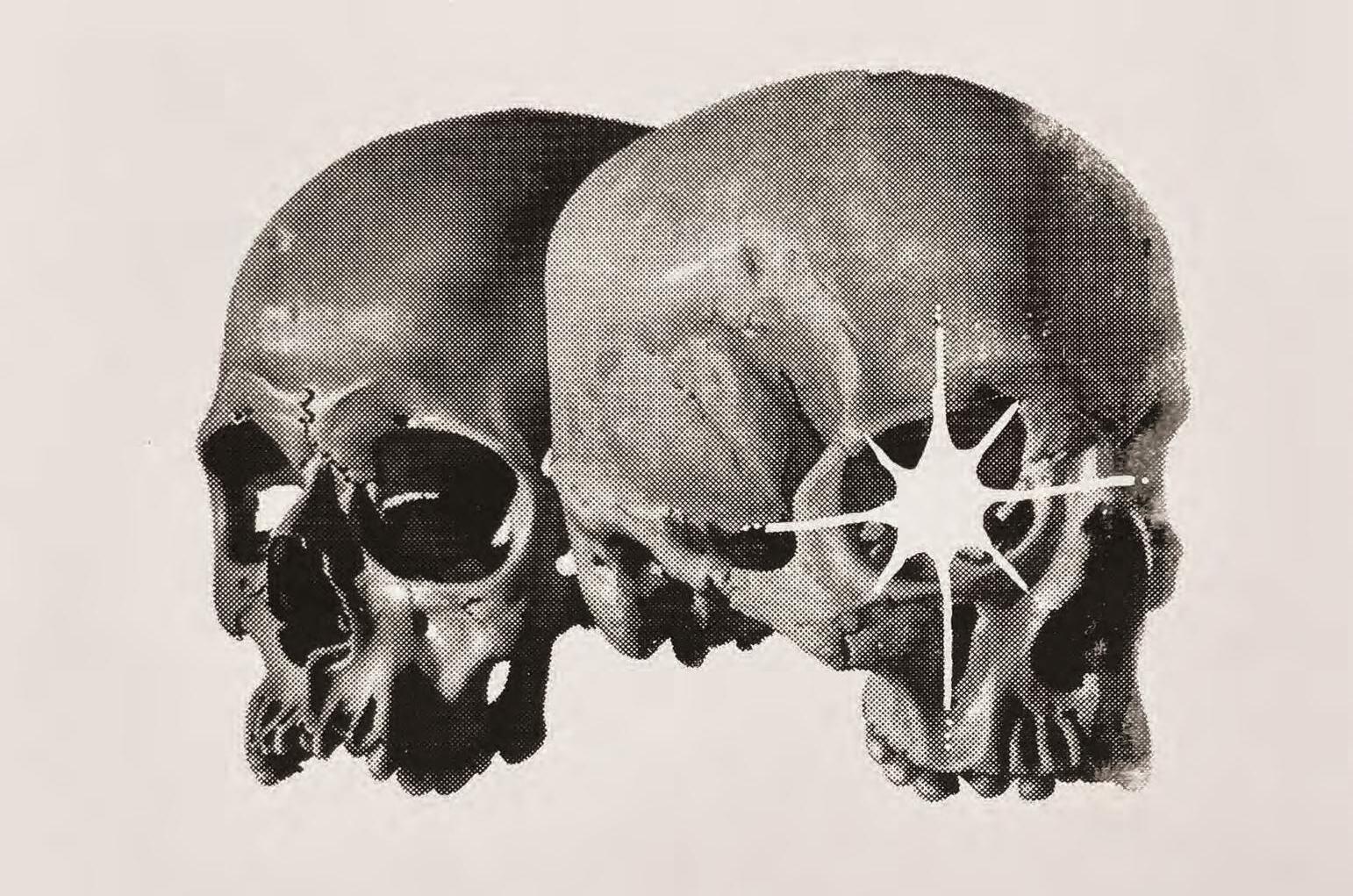

49 Skulls

LEE M, Grade 10

50 Drone Fight

JACOB G, Grade 12

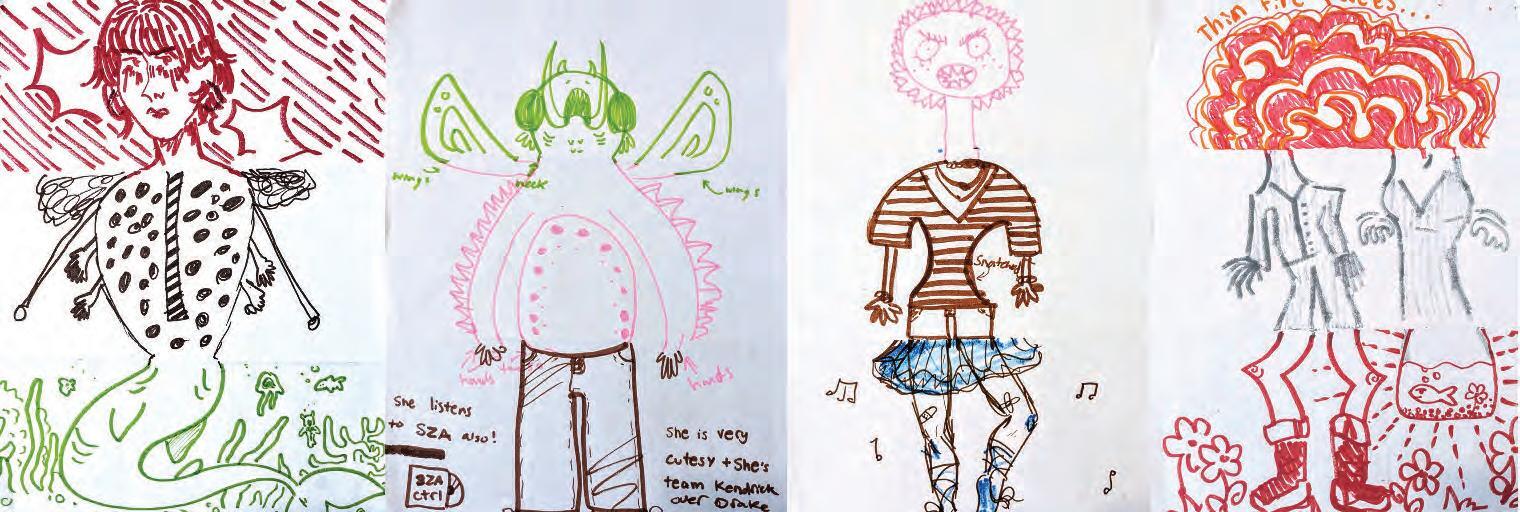

51 Creature Concepts

JACOB G, Grade 12

52 Reproductive System

MADDEN N, Grade 12

55 The Edge of the Sky

MAX M, Grade 12

56 Summoning Circle LILY G, Grade 11

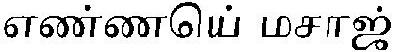

60 Thrive NICO G, Grade 12

63 Regard: Inquiry

AARJU F, Grade 10

66 Dazed & Bamboozled

SARAH K, Grade 12

71 Pantheon Angel NICO G, Grade 12

72 Dragon Mirror

LEE M, Grade 10

75 Missing Connections

ARDEN B, Grade 11

77 Solitude

ARDEN B, Grade 11

79 I’ve Been Afraid of Changing

SOFIA L, Grade 11

80 Leadlight

TESSA G, Grade 9

83 Once in a Blue Manta

SARAH K, Grade 12

84 The Valley

ULA K, Grade 11

87 Molly in Charcoal

MOLLY S, Grade 12

88 Away Triptych: Far Far Away, Driving Away, Away-ke

MADDEN N, Grade 12

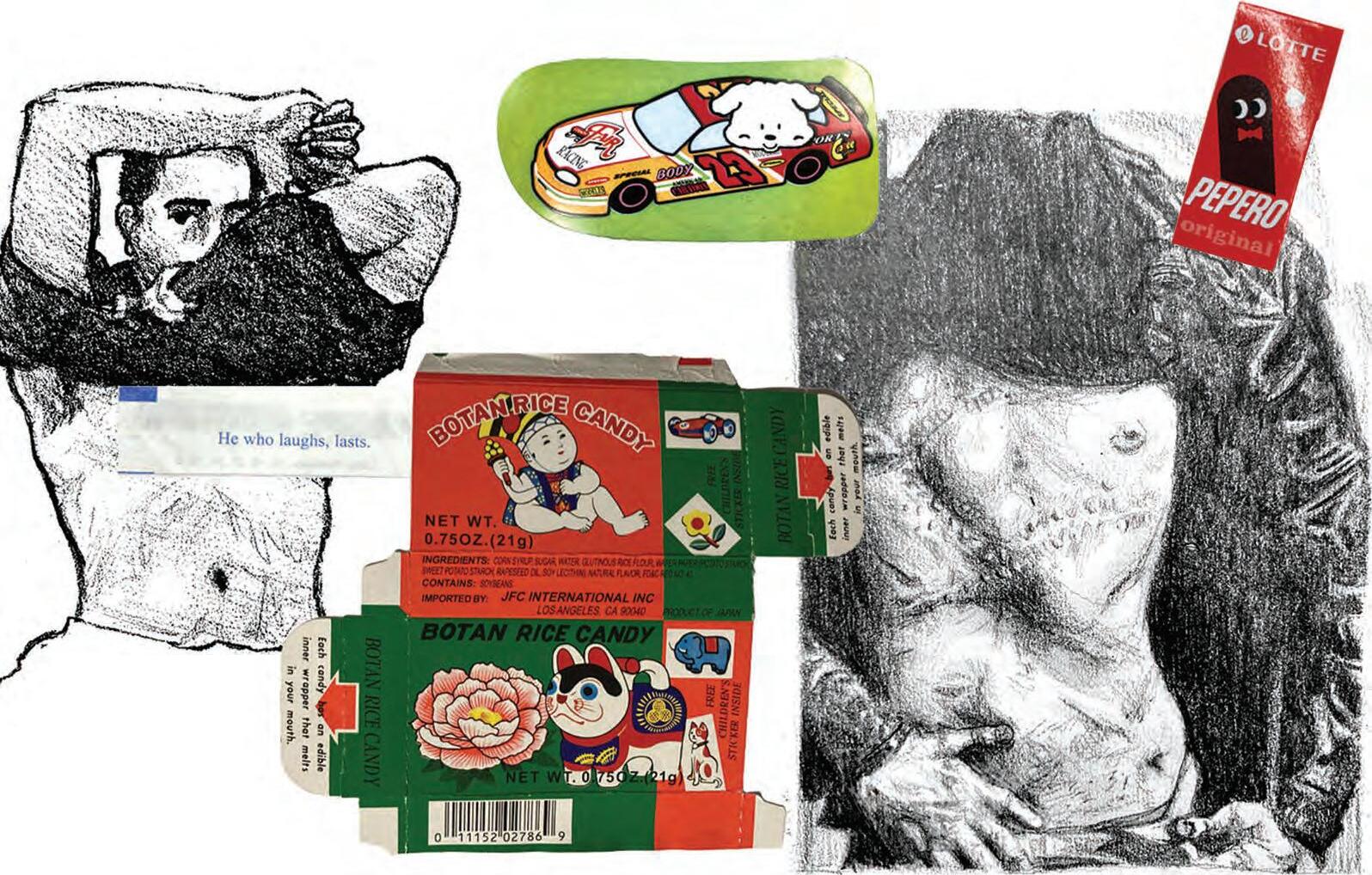

90 Untitled ECHO M, Grade 11 91 Snack

RAFA B, Grade 9 93 Moment of Disbelief and Hesitation before Accepting a Compliment

ALEXIS SG, Grade 11

Greyhound Encounter

DELPHINE M, Grade 12

Reach LILY B, Grade 11

Jerry MADDY R, Grade 10 101 Before LILY B, Grade 11

103 Writer’s Block MADDEN N, Grade 12

Laundry Day

LEE M, Grade 10 111 Incline

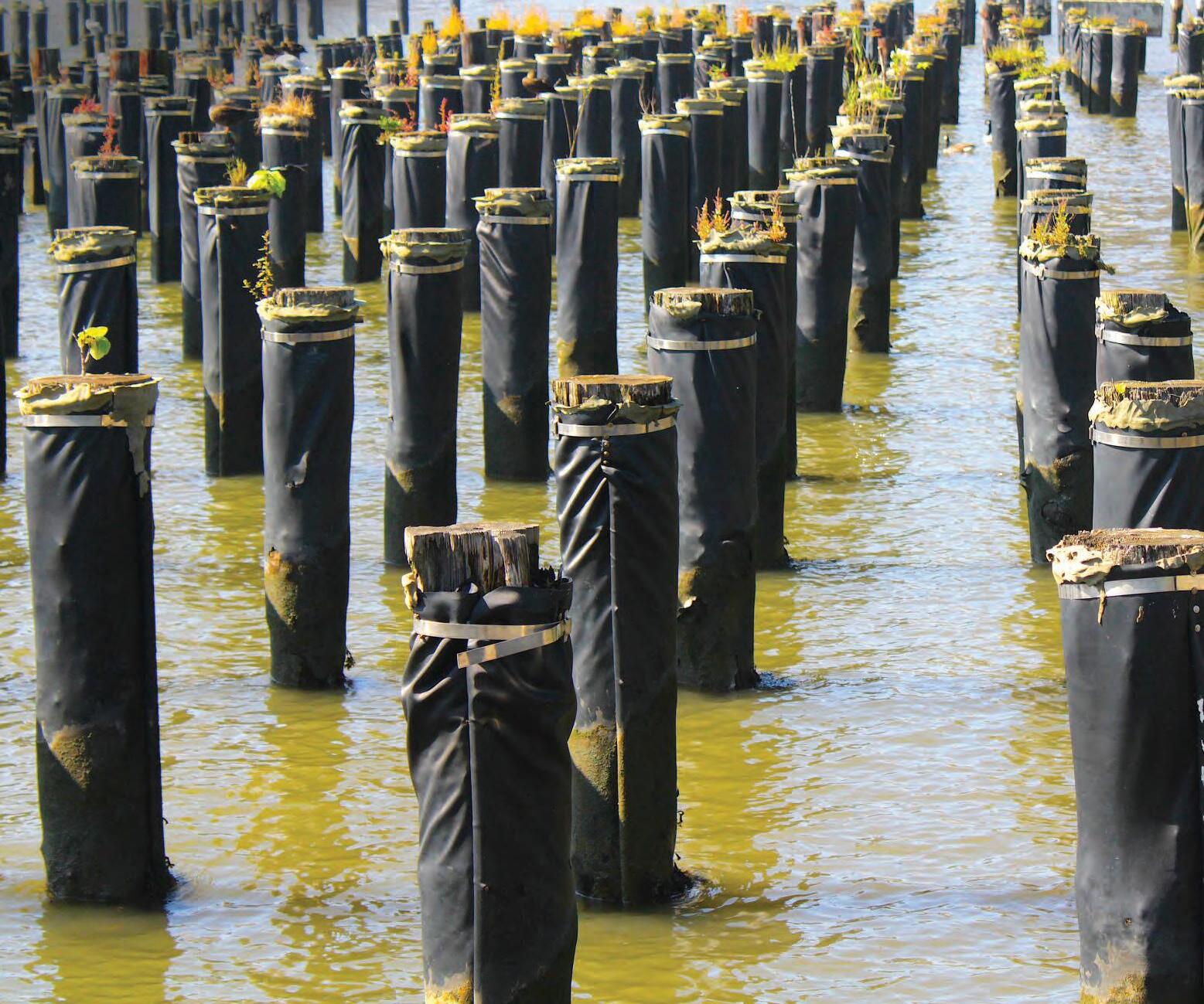

MIRA G, Grade 9 113 Tide Poles

SARAH K, Grade 12 114 Night Air

DELPHINE M, GRADE 12

INSIDE BACK COVER

Public Service Announcement

VERONICA M, Grade 9

how it must feel to drop wet, cool to the earth plucking notes from treetops and harmonizing with warbling larks. I think about the wind howling with victory, how it must feel to brush the hair from your eyes. I think about birdsong pouring from my face, my arms, my soft lips. I think about pink silks fluttering in mist keeping time with pounding feet. I think about being yours. I think about a teeny tiny ant a soaring mountain a blade of grass the deep blue sea the daring pink-orange sunset. I think I want to be everything.

H

GRADE 12 . PERSONAL ESSAY

NIONS, GARLIC, MUSTARD (which I don’t like on its own, but seems to work here), ketchup (my favorite), Worcestershire sauce (pronounced wrshtrshr), molasses (which looks like tar), and cayenne pepper: barbeque sauce. My dad’s barbeque sauce. This is, perhaps, the best dinner to have on Fire Island. After a day of sitting in the kiddie pool and washing my hair where the waves break, and before my mom rinses the sand from my scalp in the shower, I will eat barbeque chicken on the back porch with my parents and my sister and my parents’ friends and their sons, who are like brothers I have a crush on. We worry that our teeth will release from their gums with each bite of the charred meat. We will worry the same thing when our skin has fallen toward the earth and our hair has turned the color of the geese on the bay and we shrink to three quarters of our size. But tonight, we are five and we have yet to grow, so we may not worry about shrinking. It’s funny how life works; like a parabola. We seem to end where we start, a different x-coordinate, but the same y.

One, two, three, four, five. I shove each of my stubby fingers loaded with barbeque sauce, one at a

time, into my mouth. The metal bowl of sauce sits on the kitchen counter, and I sit to the right of it. I love sitting on the counter where the fake marble cools my legs, and my head fits perfectly under the cabinet. If I straighten my spine to the point where I suck in my breath to add some extra centimeters as I do when the doctor measures me, the cabinet kisses my head. I like feeling that pressure above me. Next summer I will sit here again and bend my spine to convince myself that my life is still small enough to fit under the kitchen cabinet. Then, the touch of the cabinet on my head will feel like less of a kiss and more of a casket.

My dad sweeps some more garlic off the knife and into the bowl—another taste for me. He shakes some more wrshtrshr out of the bottle—another taste for me. He drops the chicken into the sauce— yet another taste for me. Oops. Before my dad opens his mouth I know what I’ve done: I’ve come in contact with salmonella.

“Oh, Buddy,” he sighs.

My stomach drops. “Is it okay?” I ask with tears in my eyes.

“Pumpkin, that’s how you get salmonella.”

“Am I going to die?”

“No,” he says with a laugh.

But I know he must be wrong, he doesn’t have the best grasp on what’s good for you and what isn’t. This is the end of my life as I know it. The end of the parabola came too soon.

I feel a sharp pain in my feet, and that’s how I know I’ve jumped off the counter. Before I know what I’m doing, my feet carry me as if my life depends on it (which, at this moment, it does) away from the kitchen and into my parents’ bedroom. When we have friends over they sleep in the room I share with my sister, so my whole family, all four of us, sleep in my parents’ bed. There’s really only room for three so I tend to “accidentally” kick my sister off each night (oops!). But I guess my sister will have enough room soon when I die from salmonella. I climb under the white duvet, being careful that finger number two, the one that gave me salmonella, does not leave salmonella on the blanket and give it to my whole family. I rustle and weep under the covers, enough for no one to hear but my mother because she knows when her baby needs help. She finds me and wraps me in her arms as I sit on her lap. I dig my head into her neck. Somehow those parts of our bodies don’t follow the cycle of

the parabola because, no matter how much we grow or shrink, they always fit together like the missing puzzle piece you found under the coffee table. And so I cry to her about dying, about inflicting death on myself because of my wandering fingers and curious mouth. In the next few decades, I’ll fit my head into her neck dozens of times to worry about work, and pressure, and regrets, and lost friendships. But tonight, I will worry about death for the last time. I will worry about never feeling the ocean again, or the sizzling of the sun, or the freshness of the air after it rains. For the last time, I will not worry about my life, but the absence of it. For the last time, I will feel fragile under the weight of the world. Soon, I will grow stronger and taller, and my teeth will be set in place, and I will believe I can survive anything. But tonight, I know the parabola will come to an end.

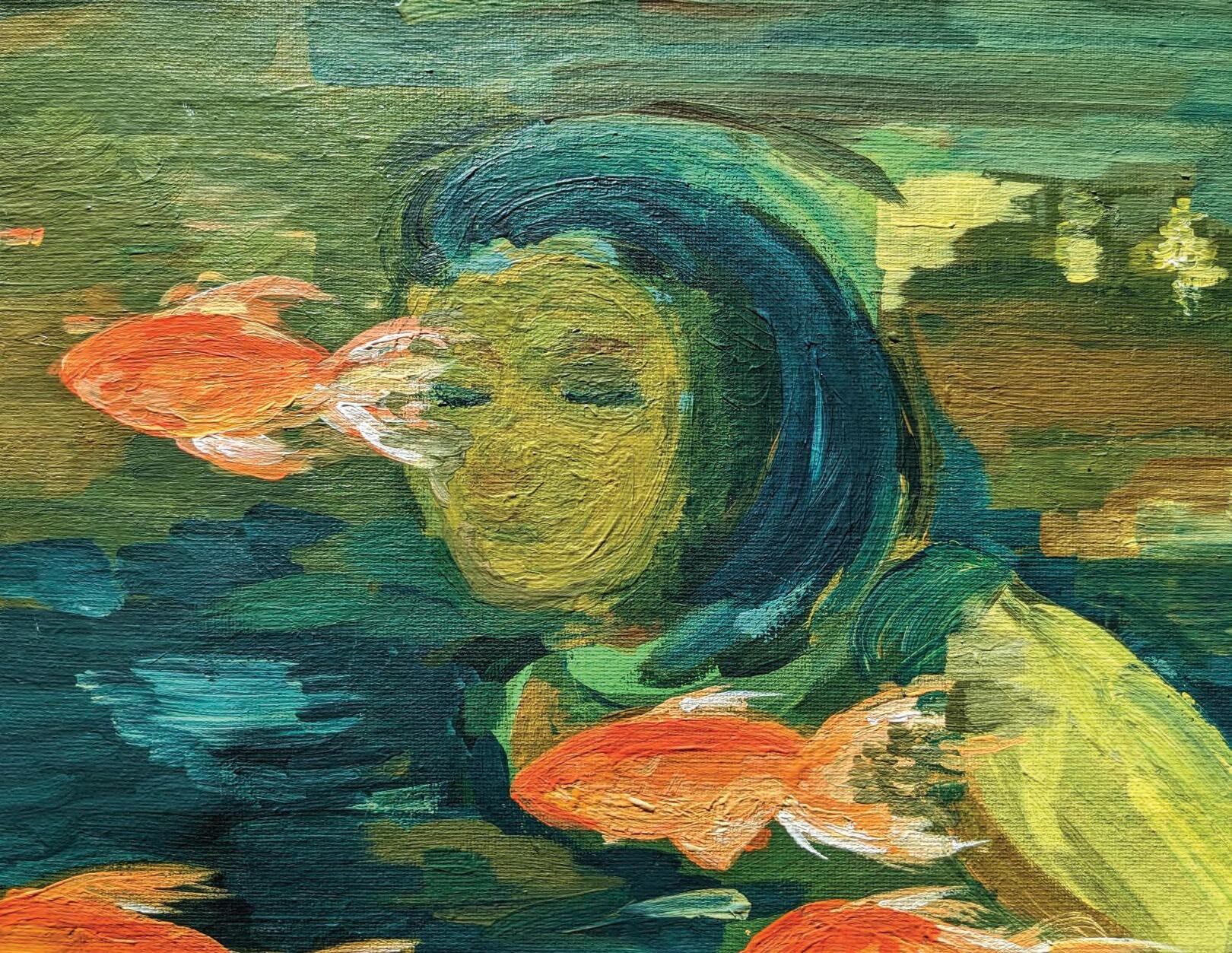

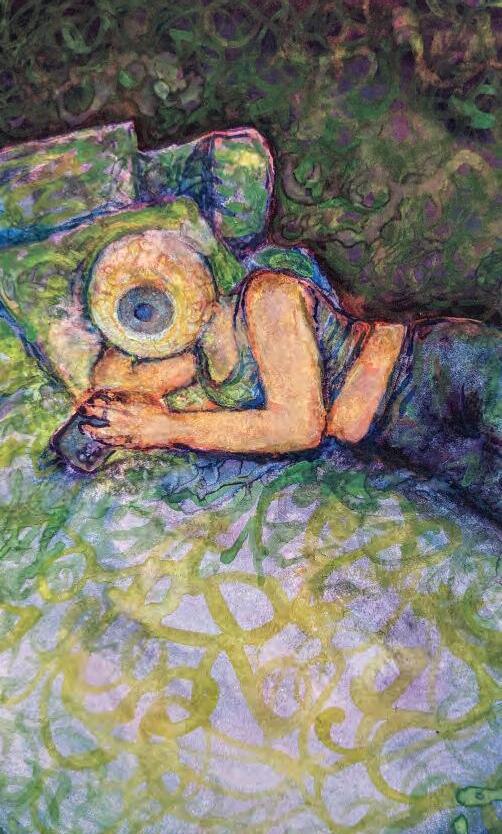

SORAYA G

Grade 10 , Acrylic

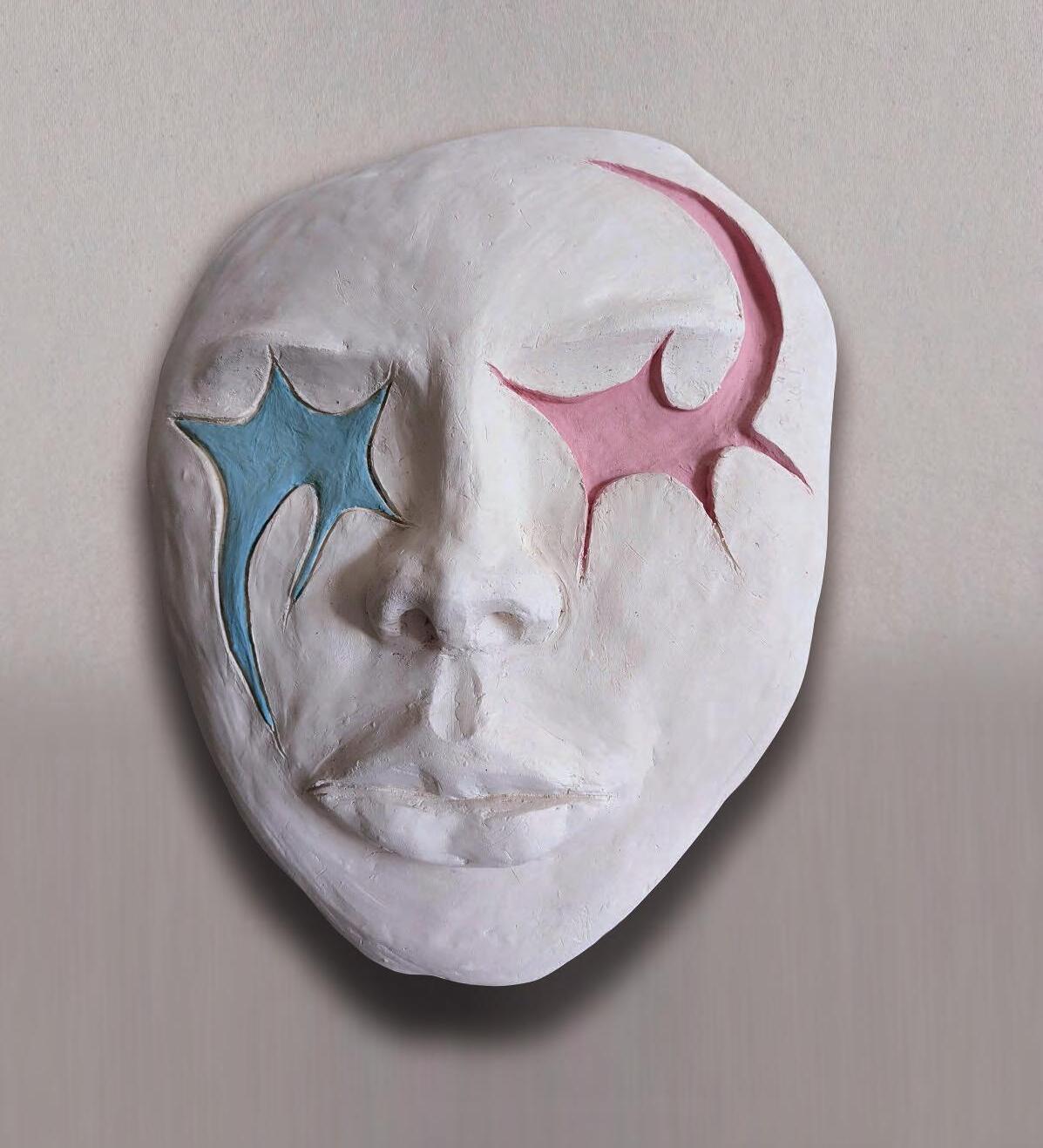

Grade 11 , Ceramic

F

IRCA DECEMBER 2022, I had been lying in my bed swiping through TikToks for hours when I encountered a video of a girl in the window seat of an airplane. She panned from the magnificent clouds outside back to her own tearsoaked face, with a caption about the incapacity of concerned flight attendants to understand the depth of emotion this flight to Europe brought her. I opened the comment section, rewatched the video, opened the comments again, and read the caption to find the hashtag ‘exchange student.’ I had just begun my application to School Year Abroad for a full year away in Spain, a country of fashionistas and ancient cities, 3,677 miles from Brooklyn. The girl on the plane framed my idea of the Arrival to the Year, that formidable, incomprehensible knowledge that the most tangible interaction between myself and my loved ones for the next nine months would be the click of a small red heart on Instagram.

Almost a year later, as Iberia flight number 6166 soared above Portugal and into Madrid, I sat dry-eyed in the window seat and struggled to adjust the supposedly reclining seat, wondering if I should’ve ordered the beef or the pasta. The following hours were filled with white plaster walls and repeatedly showing my passport to Madrid customs agents.

While talking to those agents, I must’ve had the same sort of conversation as the girl from Tiktok did with her flight attendant, but felt no urge to burst out crying. Had I done something wrong in my processing—or lack thereof—of my journey? Had I been asleep for the pilot’s announcement that my life would never be the same? I had forgotten to pack my rose-colored shades—maybe that was the problem?

The only thing that kept me awake on my first night in Zaragoza was one unexpected problem: my bedroom window was right next to the streetlight. All night, the light filled my room to the point that it could have been daytime. I tried sleeping every way I possibly could to block out what the gauzy curtains pretended to hide. My jet lag, like Prometheus’s liver, seemed to subside—only to surge back full force, leaving me with no room to focus on my surroundings. The lack of rest gave my incredible new world the quality it has during midterms: work needs to be done, coffee must be drunk, a routine must be established. Zaragoza became home quite quickly, in that at home, there is nothing to be discovered. A few days later, I decided to take a walk around the neighborhood and investigate why this empty suburb gained the name “Miralbueno,”

beautiful view. The layout was unlike what anyone could find in Brooklyn: the city just drops straight off into the countryside. From that final road I could see the whole sky, like someone had altered a camera lens and given the world a fisheye view. The soft glowing sun in the early evening gave the previously nondescript buildings new personality. It occurred to me how different this singular experience was from an evening in New York, and at the same time how not-different Zaragoza felt from home. I had acclimated fairly easily, and days after arrival still hadn’t had a big moment of epiphany. I simply felt indifferent.

In The Art of Travel, Alain de Botton lays out his own fault as a traveler: that each time, he inadvertently brings himself—his own anxieties, preoccupations, melancholia—with him. He fails to mention, however, the incredible guilt that this fault inspires. How come I’ve spent this much money, this many resources, and this much effort to come to a city that I’ve dreamt about so often and just feel . . . fine . . . about it?

It’s as if I’ve spat in the face of Spain and then continued living in it without regard. I desperately want to make amends to both Zaragoza and the parallel me that existed before arrival, to run after

her and scream that it’s not her, it’s me; to apologize for not having reinvented myself as a person. Abroad-Matilda could make more friends, could go out more, could write this essay better. Unlike de Botton, my anticipation of the arrival could not be more tied to the idea of myself abroad. I simply couldn’t wait to come back as a changed person, to have absorbed the qualities of a determined exchange student, to use the cheat code to become the mature version of myself that everyone else seemed to be. But personal development is a process so gradual that as of now I can’t say that I’ve come to any realization about myself. My internal confusion and stress is so great that even to conclude an essay about a real experience that is happening right now is near impossible. Spain has not given me clarity. It has given me beautiful views, new relationships, and a new-ish language, which could just be all that I wanted when I applied—not clarity, but something new.

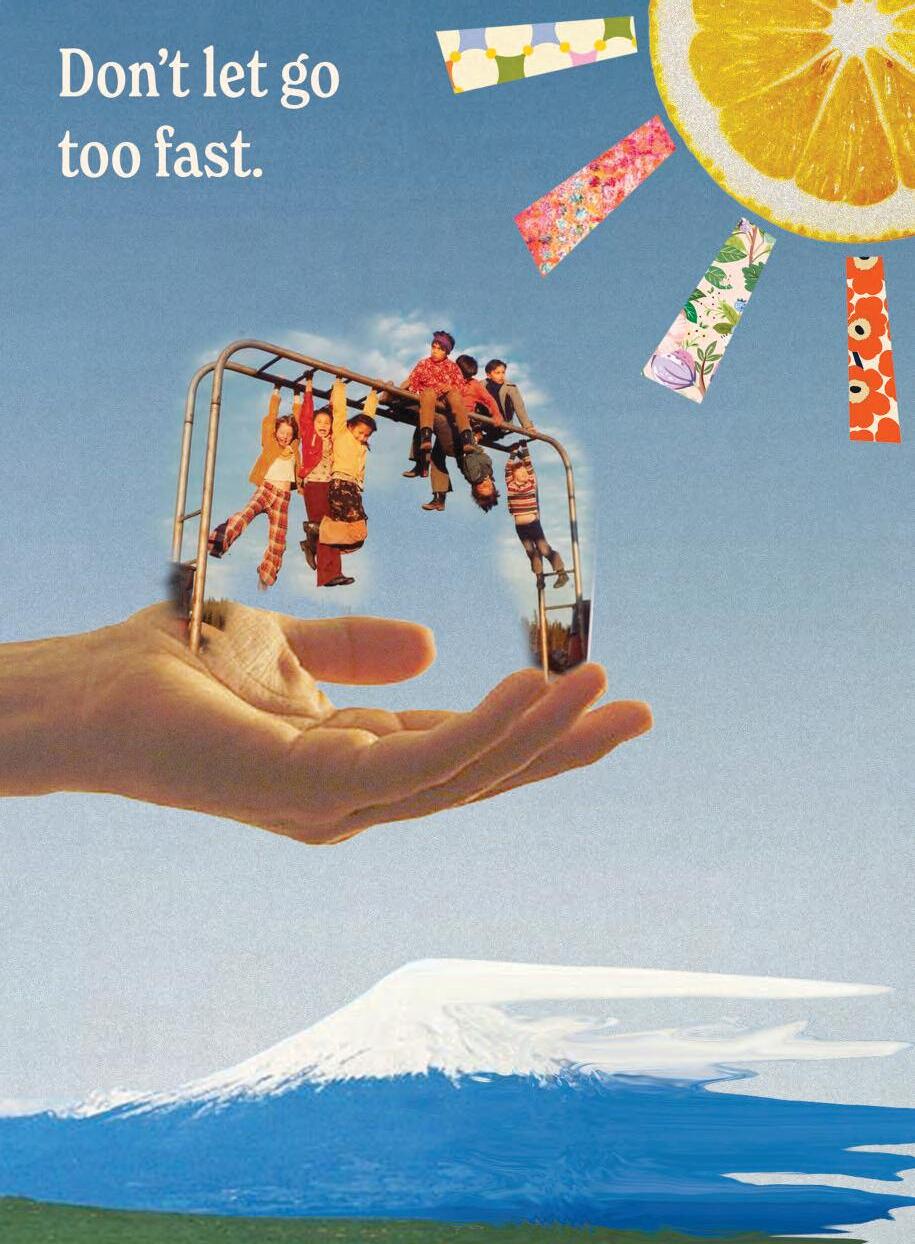

Grade 9 , Digital Collage

MAX G GRADE 12 . POETRY

usic a Lot of People Would Call Crunchy, or Granola is really about a specific group of people and a specific view behind them.

It’s really about a place.

It’s about looking down at your feet while walking to school, and knowing that the song playing in your headphones was also played out in front of that specific, recognizable, tear-jerking view.

It’s really about being somewhere and wishing you were somewhere else. So you play that music in your headphones and let it paint you a portal and imagine it playing out with those specific people with that specific view. Then you trip over the sidewalk below you because you started to forget where you actually are and foolishly began to feel like you are where you wish you were.

It’s really about hearing the rhythm and the beat and the familiar tone and immediately looking away from what you’re doing as each hair on your body stands up straight. It’s really about looking off until your eyes go fuzzy, not picturing one moment in particular, but a slurry of them all. Of running through the snow. Of holding hands in the meadow. Of looking out at that specific view. And feeling your heart start to drift off.

Tubs of Chocolate Icing

are really about the giddy little kid who jumps out of you when a birthday cake gets taken out of the kitchen.

They’re really about stealing the big tub from the storage room and pigging out with Amalie, Ron and Mina.

They’re really about a quick sugar high and a rush to the aux plug at the end of study hall.

You hope so hard that there’ll be a dance party that night, and that everyone else will be in the mood to dance it out too.

They always are.

There’s always more chocolate icing in the tub. There’s always more bowls of it to pig out over and more songs to play when it’s time to dance out the sugar high.

Until the tub is empty–and it’s time to go home.

And not eat chocolate icing for a while. At home there aren’t any tubs of it to eat.

And it isn’t really about all that anymore.

But sometimes you eat it and listen to that music most people would call crunchy, or granola.

It gives you goosebumps and fuzzy eyes too; thinking about the days when it came in a tub.

Being Too Cold

is really about cuddling up on one small sleeping pad. Or even in one sleeping bag, because even all the layers and layer and layers of fleeces and puffies can’t keep you as warm as body heat can.

It’s really about getting close enough to stop shivering and inching closer and closer to one another during the night, because the warmth is irresistible. It’s really about avoiding the snow, but the snow being unavoidable. It’s really about living in a world of white and blue, right at the edge of the sky, where it’s never felt colder. And the people have never felt warmer.

The Back Porch of Whover’s Hall

is really about being in the place where we all howled at the moon. It’s really about where the snow first fell on our shoulders. Where we danced in the rain for the first time. And the last time.

Where we fell in love.

Where the crunchy, granola music is played. Where the icing was eaten. Where we were always cold, and squished together at one table to stay snug. The back porch of Whover’s Hall is really about that place we wish we were. That place we drift off to when our eyes go fuzzy. That place where we said “we’ll all be here forever.”

It’s really about a specific group of people and a specific view behind them.

AMELIA L

12 . PERSONAL ESSAY

Y MOM SCATTERS MEMORIES of my middle school years all across my bedroom

floor as Eva sifts through my old shirts, skirts, and pants, no longer compelled by my old dresses. Each time Eva, Nathaniel, Julia, and Maddie come back to America for December, they leave with an extra suitcase. It’s red and not too big, eventually filled with all the clothes that no longer fit me and my sister, but which are the perfect size for our ten-yearold cousin. There always used to be some air of reluctance that followed this tradition. I have distant memories of tears being shed as my sister and I said goodbye to the items of clothing we had cherished. But this tradition isn’t a cause for mourning anymore. I watch as Eva’s eyes scan over the emptied contents of the clear plastic container that holds our hand-medowns, not sure where to begin. As she looks through my old favorites, I create a map in my mind. I wore that shirt at my tenth birthday party, I wore those pants on my first day of middle school, I wore that yellow dress for sixth grade picture day.

“Girls, do you remember this!” I look up to see my mom holding a pink T-shirt with white stripes, and a sequined sparkly peace sign in the center. Upon

seeing it again for the first time in years, shallow memories that linger distantly in my mind resurface.

I remember the way I would play with the sequins when I was bored in fifth grade math, or when I didn’t want to look my friend directly in the eye after hurting her feelings.

“Eh, I don’t really like pink that much anymore,” Eva remarks as her eyes drift over to a yellow shirt instead. I only see a flash of disjointed sequined reflections as my Aunt Julia tucks the shirt into the depths of the red suitcase anyway.

I fiddled with the sequins as I waited for Esme to finish tying her dirty shoelaces. Sunlight leaked through paper thin curtains of the house that was still vaguely unfamiliar to me, reflecting off my shirt, to shimmer on a patch of the kitchen wall where paint was peeling. Esme and I had grown up with our families inextricably linked. My cousins were hers, her parents were mine. I would tell people I wasn’t the oldest child, because I basically had an older sister. Back when I was little, I only ever saw her when our families joined together. As often as that was, when I couldn’t see her for long stretches, I

RILEY R

Grade 9 , Watercolor

felt gaps growing in me that time couldn’t mend. When I began middle school, she moved into the new house in Kensington. I took the train for the first time by myself. Two stops over to see her.

Upon seeing the refracted light dancing on her kitchen wall, she looked up to say, “Oh, I remember that shirt! I wore it all the time in middle school.” I used to hate it when she said things like this. Especially around our parents. I don’t know why, but after hearing those words, there would be a lingering feeling of frustration I just couldn’t shake. She would emphasize our nearly four-year age gap, and my eleven-year-old brain had always twisted and warped this time between us into an eternity. Hearing her wistful comments about the pink shirt with a thread hanging loose meant to me that nothing that came from her would ever truly be mine.

She finished tying her shoelaces, got on her coat, and gave me a hug that caught me by surprise.

“I’m so happy you’re here.”

There is a specific part of my brain that is solely dedicated to the things Esme has told me before, however small or insignificant they may be. I can’t

‘‘ ‘‘

HER ROOM IS LIKE RAPUNZEL’S. THERE ARE PAINTINGS AND ART HANGING ON EVERY SURFACE, AND I WOULD ALWAYS SAY THAT HER CREATIONS WERE BETTER THAN THE ART WE SAW IN MUSEUMS.

remember when exactly I let myself be the younger sister. At some point, I knew any frustration I felt was an act of grabbing blindly at the integrity of being the older mature sister when I was at home. I eventually released the tension in my shoulders when she would beg me to let her braid my hair.

We spent so many spring afternoons sitting on her bedroom floor. As she would lean in to finish

brushing the blush onto my face, I scanned the room. Light and shadow entangled in the atmosphere of late March, when the sun lingered in ways that continued to surprise me. Her room is like Rapunzel’s. There are paintings and art hanging on every surface, and I would always say that her creations were better than the art we saw in museums.

“Your freckles are so pretty, Amelia,” she said gently as she pushed the hair out of my eyes. When I got home that night, I stood smiling at myself in the mirror, trying to count them all.

September tries to twist and mold me into whatever I want to be that year, eventually giving up and starting over again by November. I remember wearing Esme’s dress on the first day of eighth grade hoping to be her, but Izzy rejects my old shirts, grappling with some sense of defining individuality that I’ve never wholly understood.

“God, what if everyone hates me!” she declares in her typical diva fashion.

“You can always hang out with me,” I suggest.

“Ugh, no.” She lies face up on the floor, rejecting every outfit I suggest. Unconditional hand-me-downs pile up on our childhood carpet as we sift through her

drawers, reminding us both of our December tradition. There has always been a layer of confusion that rests comfortably in the spaces between our understanding of one another. I’ve learned to let it rest.

“What about this one?” I suggest. It jumps out from the middle of our mess, and now lies on the ground begging to be worn again. We watch it from a bird’s-eye view, and in my blurry morning vision, it seems to shrink as we stand there.

“I want to wear pink, but that’s too pink,” she declares. It hasn’t been worn since the beginning of her eighth grade year, but it lasted her longer than the rest of us. We put it back in the drawer, and excitedly return to a state of restless “I remembers.”

As I watch frozen cubes of coffee slowly melt into a cold glass of milk, I wipe sweat from my forehead and hear my cousins’ laughter coming in from outside. They run around on the grass barefoot, kicking the deflated soccer ball that Nate found under his bed last week. That same day, I find a new coffee stain on the old faded couch cushions. I hesitantly cover it with the nearest pillow, and continue to doodle in my journal with Eva sitting

next to me. She writes in perfect cursive in her spiral-bound notebook, glances over at my wrinkled pages, and declares she couldn’t possibly begin to decipher my handwriting.

“I hate summer, because it gives me mosquito bites,” she exclaims, startling me out of the restful silence we’ve made. I lean over, careful not to let my wet hair drip on the pages of her journal, to see all the scabs that cover her legs.

“I’m sorry.” I squeeze her hand as she leans her head on my shoulder, not caring if her hair gets wet. Every summer, I watch her undergo metamorphosis from the absurdly mature eleven-year-old who watches out for her younger brother, into the kid who picks at her mosquito bites no matter how many times I tell her not to. She is less of a cousin and more like a younger extension of myself, as July has never failed to bring her back to me. The other day, I found the pink shirt with the peace sign in her drawers after she asked me to pick out her outfit. The loose thread had been mended, and I’m still wondering why she brought it with her, even though she no longer likes pink. She never wore it once, but let it sit among the rest of the hand-me-downs. As her eyes continue to scan the pages of her notebook, her finger traces the poems she wrote about our day

at the pond. The significance of the moment only washes over me once it is August and summer slips from my grasp.

The second she gets back home, she calls me on her landline. “I’m calling to say goodnight,” she says softly into the phone.

“It’s still 3 p.m. here…”

“Oh, right.” I can hear her voice begin to break from the other side of our connection, my own beginning to catch in my throat as well. I remember how I would endlessly beg her to just let me brush her hair, but she always refused. I think she found comfort in leaving the knots as they were. After long days of salty water, her long wavy yellow strands would interweave themselves and begin to lighten, as my own curls frizzed from the moisture that never left the air even for a moment. Beneath the scabs, the knots and the fraying hems of skirts and shirts, she is living her childhood through pieces and fragments of my own.

no just verbs for this traffic jam

GRADE 11 . POETRY

NCONCEIVABLE, to not know you. like there’s one set reality and we’re all just shoehorned in, like i’m threading through the cars. i always hated motorcycles, the way they sound, but sirens are coming and i’m not yet out of the street. now we’re driving in circles, veering into sidewalks. no one’s safe, no one is sugarhappy. the lights are always red. over-promising myself like i’m written on a peeling receipt. one

me, fifty cents. two for seventy. now that’s a steal. give me a chance to fail, i promise it will be spectacular. i have nothing much to offer you. is it just me or is the sky caving? pink tinged menace. i hope you like sunsets.

GURLEEN K

GRADE 10 . PERSONAL ESSAY

My cousin Gurjeet and I are walking to Dollar Tree. She’s laughing while covering her mouth so no one sees what she looks like while smiling. She slaps my arm and pushes me to the side as usual because she can’t stop giggling at random things; of course I join her. She has on her usual black leggings with a tee plus a zip-up sweater, and her black curly hair is slicked back. She opens the door to the Dollar Tree, pushing it wide open and making a loud noise that catches everyone’s attention in the store. I think to myself, there she goes again, grabbing people’s attention just because she loves it. She grabs a cart and runs in her crocs to the party section. My cousin grabs accessories, like a big, glittery, bright pink birthday hat. Then she grabs a bright blue necklace of flowers and puts it on. She says, “Let’s do a photoshoot.” When I’m with Gurjeet, it feels like the world doesn’t have any problems but is just filled with joy and laughter.

ANAND 1

“You always late.”

“I know, bro, nobody be leaving my house on

time,” Gurjeet says, dressed up in a beautiful baby pink salwar kameez, her hair up in a gura, and her chuni draped on her head covering half of her hair.

“I’m almost ready, I just need to finish tying my disstar,”2 I say.

‘‘ ‘‘

GURJEET IS SITTING IN A W SHAPE LIKE A TODDLER

WHILE ALL MY OTHER COUSINS AND I SIT CRISSCROSSED, OUR PLATES FILLED WITH THE WARM, HOME COOKED CHICKEN CURRY, PIELA CHOLL, SHAHI PANEER, AND DHALL.

1

2

“How do you get your layers done so neat and clean?” she says, sitting down beside me looking at me tie my pink disstar. I see her watching me closely through the mirror.

“Practice, that’s how. You’ll get there one day.”

Still watching me tie my disstar, Gurjeet says, “When you finna teach me how to tie the crown, I’m in love with disstars.”

“I got you any day,” I say while we walk to the Gurdwara Sahib3 and sit down. Gurjeet listens to our prayers, sung by everyone in the room, including me.

“Wow. I feel at peace, I feel free,” she says with this look on her face that I have never seen. She isn’t smiling nor is she laughing. She is listening carefully. She seems like she is in Anand while everyone else sings prayers out. She says, “Kirtan is so peaceful.”

I glance at her, thinking I hope she finds this taste of peace she received today permanently sooner or later.

I open the door to my uncle’s new house, and there she is, my cousin waiting for me. We haven’t seen each other for a few months, but the months felt like decades to us. Our parents’ problems force us to

be apart. My cousin and I always say together, “It’s not fair we don’t get to see each other often anymore just because they get into arguments.” She rests her hand on my arm and pulls me to the backyard of our uncle’s new house, where all of our relatives are gathered for our family reunion. She tugs on my arm, pulling me toward the bouncy house. We jump up and down, laughing loudly as she’s covering her mouth as usual. I never understood why she would cover her smile, because it’s the prettiest smile I have ever seen. We sit down and eat inside the bouncy house. Gurjeet is sitting in a W shape like a toddler while all my other cousins and I sit criss-crossed, our plates filled with the warm, home cooked chicken curry, piela choll, Shahi paneer, and dhall. We all sit, eat, and talk all night. We don’t know when we will see each other again.

3 Sikh place of worship

Untitled: “To day It’s

TTODAY IT’S MISTING, if not raining, ever so slightly, and this wallpaper is eggshell blue and peeling and there is a little yellow lamp in that corner.

Your chest is heavier than usual today and the bruise on your knee is almost beautiful. Almost. And how do we conceptualize time?

Raining. It’s definitely raining now.

Your features are starting to melt into something lovely. You wish others would see that, too.

And why is self-love always retrospective?

But there you were, spinning until all sunlight drains from the sky. You laugh and collapse on the grass.

You are fine.

WYATT B

GRADE 12 . PERSONAL ESSAY

TTHE SUMMER I WAS SIXTEEN, I wanted a job. For the last six weeks of my precious break, I was to stay with my parents in Fire Island, a small community off the coast of New York. Covered in boardwalks and beaches, it was where old and middle-aged people went to play tennis and spend summers with their teenage children, and where those teenage children went to lounge in luxurious beach houses and swim in the ocean. Though I definitely enjoyed the idea of making money, it wasn’t the main reason I wanted to find work: I was bored out of my mind. I needed an experience, an adventure, an epiphany, just something to do to make my summer interesting. I got on my semi-broken black bike, pedaled over to a nearby restaurant, applied to be a busser, and was hired! And with that hiring, I felt destined for a summer of adventure, a summer of making friends, meeting girls, and having fun. When I showed up for my first day of work however, I realized that while I would get an adventure, it wouldn’t exactly be the one I’d hoped for.

Le Dock was a restaurant a five-minute bike ride away owned by two men named Michael and Lance.

Lance was a tall, thin, pale-skinned man in his midsixties who looked seventy but was in fantastic shape. He was extremely kind, never once raising his voice for the entire time I worked there. You could relax around Lance because you knew that he knew that everything was going to be fine. The lack of restaurants on Fire Island made his extremely

‘‘ ‘‘

DURING SLOW SHIFTS, I WOULD IMAGINE THAT THE MICHAELS COULD FUSE TOGETHER LIKE VOLTRON, CREATING A MECHAMICHAEL THAT WOULD PROTECT THE RESTAURANT WHEN IT NEEDED THEM MOST.

popular, so no matter how crappy the food was, customers were always back next Friday, if not earlier. But Lance usually wasn’t around much, as he let his business partner Michael, the chef of the place, handle the boots-on-the-ground operation.

Michael was nothing like Lance: he was intense. The way I remember him was as a seven-foot-tall figure with a barking voice and a face similar to Anthony Bourdain. I don’t think I saw him blink once. He was probably just a normal-looking, fairly tall guy with a pretty loud voice, but to my sixteenyear-old self, he was the wrath of God. As the head chef of the place as well as its co-owner, he was always bellowing orders from the kitchen to the other chefs and waiters, but usually saying no more than three sentences to me in an entire shift.

“Table thirty-four needs water.”

“The phone’s ringing.”

“This kid is shadowing you today.”

Any time I broke a glass, screwed up an order, or left a table messy for too long, I could see rage well up in his unblinking eyes, only for him to exhale aggressively and order me to handle it before speedwalking away. A strange thing to note about Michael’s hiring practices though: he seemed to have a bias for hiring one specific type of

person—a Michael. The man loved to hire people with his own name. He hired eight of them in fact, making a huge percentage of the workforce at the relatively small establishment a Michael. There was Michael Panarello, AKA Pan, Michael the other chef, Michael the bartender, Miguel, and Michael the busser to name a few. During slow shifts, I would imagine that the Michaels could fuse together like Voltron, creating a mecha-Michael that would protect the restaurant when it needed them most. I knew others existed from seeing a mystery Michael take a shift on our work app or hearing one of the particularly chatty waiters talking about a new one during family meal, but at the end of the day, I’ve to come to terms with the fact that I have not met all of Michael’s Michaels, and likely never will. But the ones I did meet, well they knew how to run a restaurant.

Considering this was the only restaurant in the neighborhood, no night was slow, and every night I wished I could have been a waiter instead of a busser, getting paid around fifteen dollars an hour and a meager 10% of tips. I wouldn’t stop moving from the moment we opened to two hours after we closed. The first couple of hours I always felt productive and buzzed, but soon I began to lose

speed. Any fantasy of being that attractive and mysterious guy who works at a restaurant quickly goes out the window when you’re cleaning the bathroom and seeing your sweaty self in the reflection, covered in clam chowder, of course, because someone from table thirty-seven wanted to be helpful and hand you their plate with a little too much force. By the end of every shift I was mentally and physically exhausted, ready to crash on my family’s couch before even making it to my bed. And that was when I was lucky enough to be a busser. I also worked half the time at Michael and Lance’s much lower paying pizza place, “Le Pizza.” I could say I took the job when Lance pitched it to me because I enjoyed the idea of being a pizza boy or wanted a new experience, but that wasn’t what happened. What happened was I accepted their proposal because I saw a cute girl named Ashley working the cash register and after a quick conversation, I had a little crush. And just like that I had handled Michael and Lance’s pizza boy problem. And that girl? She left a week in, and to be honest, even if she had stayed I doubt I would have had the confidence to ask her out in the first place. Though Le Pizza paid much less, it had a quiet charm to it

compared to the frenzy of Le Dock. I ended earlier, moved less, and even had a wooden chair to sit on in front of the cash register. On top of this, I worked with Miguel (!), a Mexican man in his early thirties who had been working the pizza oven at “Le Pizza” for thirteen years, long before new management had

‘‘ ‘‘

WHAT IF I’D TAKEN A DIFFERENT JOB? WHAT IF I’D TRIED HARDER TO MAKE MORE FRIENDS? WHAT IF I’D ASKED OUT THAT GIRL AT THE CASH REGISTER? WHENEVER I ASK MYSELF THESE QUESTIONS, I ALREADY KNOW THE ANSWER: ONLY MICHAEL’S MICHAELS KNOW FOR CERTAIN.

taken over. He and I had a quiet, polite friendship where he would look the other way when I would swipe a slice and I would clean his station for him so he could get out a little early. Nights at Le Pizza were relaxed but also rather sad for me, as I served slices to other teenagers going on dates or hanging out with their friends before heading to some party later that night, usually around the time I was quietly sweeping Miguel’s station.

By my last day of work, I couldn’t wait to get back to New York, AKA “the mainland.” But as I rolled silverware into napkins for whoever would be working tomorrow, I couldn’t help but feel disappointed. Before I had arrived I’d had goals of bonding with my coworkers, befriending my bosses, and maybe even meeting someone cute, but to my dismay, none of these things had happened. What was the point of all this? Where were my friendships and epiphanies? As I finished the last of my napkin rolls however, a fat envelope fell in front of me. I looked up to see Lance standing over my table.

“That’s all of it,” he said.

I had been a complete idiot. Who was I to be so entitled that I expected every experience to have

some special meaning? I got a job, did the job, and was paid exactly the amount agreed upon. They never promised friendship, respect, or adventure, so why should I have expected it myself? I took the money, shook Lance’s hand, biked to the ferry to meet my parents, and got the hell out of there. Looking back at that summer, I can’t help but wonder about what could have happened if I’d taken a different turn. What if I’d taken a different job? What if I’d tried harder to make more friends? What if I’d asked out that girl at the cash register? Whenever I ask myself these questions, I already know the answer: only Michael’s Michaels know for certain.

AARJU F Grade 10 , Photograph

10 . HUMOR

S A SOCIETY, WE TEND TO reward functionality, and, as a result, punish impracticality. Think how quickly new technology is replaced, for example, or, how quickly athletes are traded once they age. The main exception to this rule is the EXTREMELY common use of the number 2; people ignore how it’s the most unoriginal, boring, simple, yet difficult number there is, and put it literally everywhere.

Its whole goal, as the first even, is to fit into as much of everything else as it can. Tell me it has a personality of its own—you can’t! It morphs itself into everything else because it has no individuality and no redeeming qualities. It has to change into anything and everything else to hide its worthlessness..

Well, you might think, at least it’s easy to deal with! Nope! Its square root is hideously irrational (1.41421356…….. and on, with infinite digits), making it abysmal math-wise. And of course it’s a prime number, because why wouldn’t it be? On top of having an awful square root, it’s not divisible by anything. Seriously? Such a useless number can’t even be divisible by anything?

But okay, apart from the nerdy math stuff, does 2 sucking really matter? Absolutely. Some people don’t

mind losing. Others, including myself, very much do. Although many would consider second place a victory, it is, speaking from personal experience, the bane of a competitive existence. Ask any competitor; I guarantee that they’d rather be last place than be second place, because coming in second is the reminder that you really tried, really had a chance, and still did not succeed. The memories of (seemingly wasted) effort and talent, immortalized by a slightly-smaller-than-first-place trophy or a silver medal, are an eternal progress stifler for those who possess them. There is no greater cause of anger to a person whose only goal in life is to win, win, win, than being told by ignorant bystanders Wow, great job! when you’ve just lost—excuse me, come in second.

They say the losers of the Super Bowl get a party too. Just imagine spending your whole childhood playing football, getting really, really good, making the NFL, playing well for a couple of years, signing with a contending team, and making the Super Bowl. And losing. Imagine people trying to console you by giving you a, “It was still a great season, and you lost to the winners, there’s no shame in that” party. That sucks. And, fittingly, which number do we

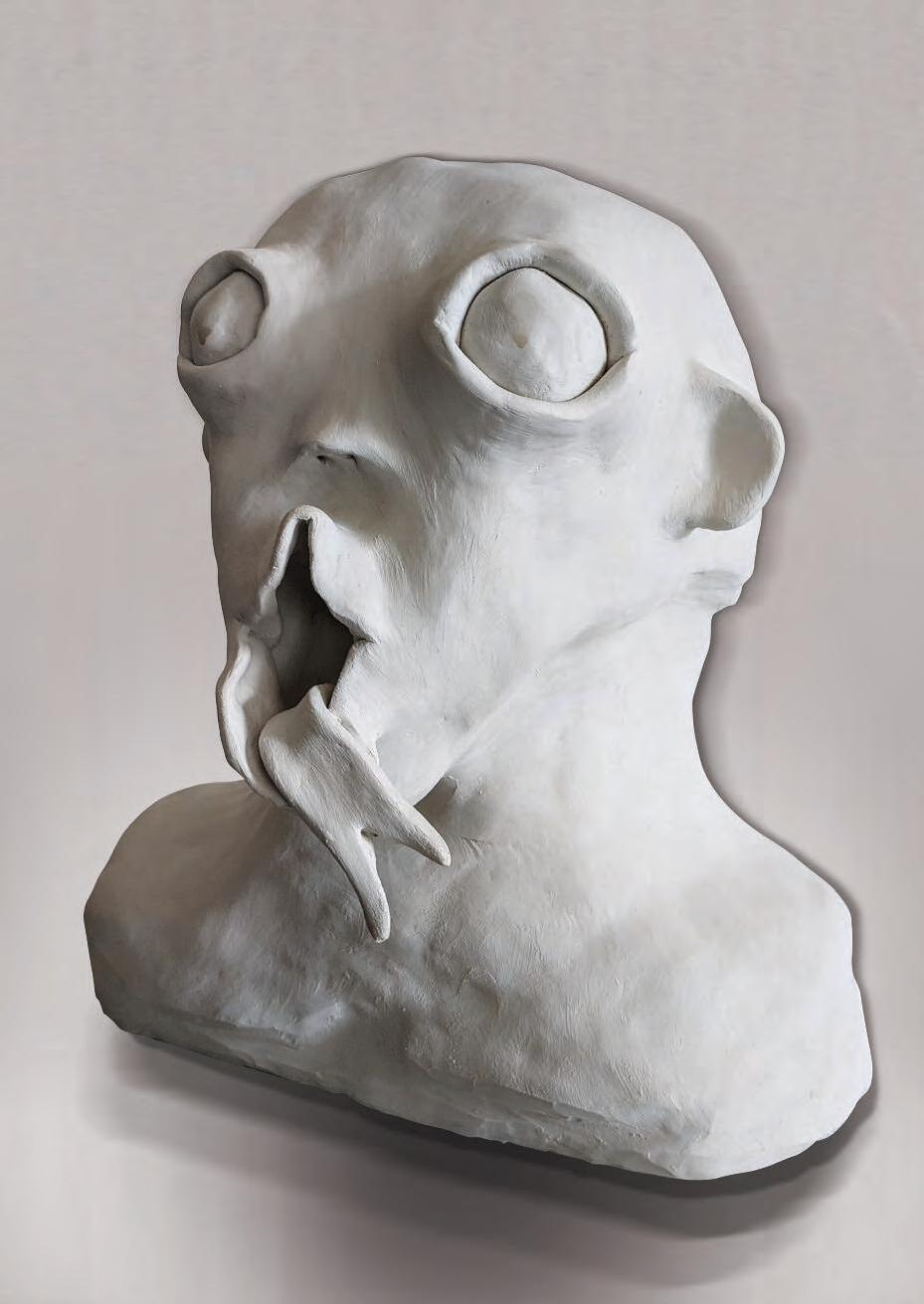

Grade 10 , Sculpture

assign to this miserable yet supposedly great achievement? 2.

Humans are classified as tetrapods, four legged creatures, because we descended from a common tetrapod ancestor—however, unlike other tetrapods, humans walk on 2 feet and use our remaining limbs for other tasks. Imagine how much better we would be if we had eight limbs; we would move faster on four legs than we can on 2, be stronger, and be more versatile; the only problem would be finding pants that fit. But seriously, why would anyone choose to walk on only 2 legs and have only 2 arms? If you break a limb now, you’re down to one, and basically immobilized for as long as it takes to heal; if you broke a limb before the advent of medicine, you would likely die. Dying because of breaking one of a very few 2 legs or arms implies, to me, that 2 is just not the right number, and therefore I propose a change in human limb number.

In a more real-life vein, consider something like rock climbing. You always want to have at least three points of contact. If you only have 2 and you don’t happen to be a mountain goat, bye bye. Again, death by cause of 2.

‘‘ ‘‘

IMAGINE HOW MUCH BETTER WE WOULD BE IF WE HAD EIGHT LIMBS; WE WOULD MOVE FASTER ON FOUR LEGS THAN WE CAN ON 2, BE STRONGER, AND BE MORE VERSATILE; THE ONLY PROBLEM WOULD BE FINDING PANTS THAT FIT.

The Romans didn’t have a “number zero.” They let it exist solely as a concept, not as an actual tool of math, because of what a pain it was for them. I suggest, given how 2 causes death and destruction, we take the Romans’ example and remove it from existence. Thank you.

DANIEL E GRADE 11 . POETRY

Yaritza lived in Washington Heights

Miguel lived in Corona

Raul lived in Hunts Point

Gloria lived in Sunset Park

Josefina lived in Port Richmond

The doors of la Ciudad de Nueva York 1 are open to everyone

Yaritza stepped forward, exiting the Dominican Republic

Miguel had shut his Salvadoran door for good

Raul constantly opened and closed his door to Puerto Rico

Gloria closed her Colombian door for the American one

Josefina leapt away from Mexico toward “freedom”

Yaritza worked as a maid for the Smiths

Miguel worked in construction

Raul worked as a Spanish teacher at the local public school

Gloria worked as a bartender

Josefina worked at her local deli

1 New York City

Yaritza dreamt of being a model, but her hair and skin were unprofessional

Miguel dreamt of being a violinist, but construction busted his fingers

Raul dreamt of studying law, but he got stuck in the loop of poverty

Gloria dreamt of being an accountant, but she couldn’t speak English

Josefina dreamt of opening up a restaurant, but nobody would sell to her

They built families from aspiring hopes and dreams

They always followed the rules, whether it mattered or not

They arrived early and left late

They prioritized their families’ health

They always started and ended their day with a prayer, thanking God

They always sent food, money, and clothes back to their families abroad

They taught their oldest children to be selfsufficient

They taught their youngest children to respect their elders

They reused plastic bags, clothes, plastic bottles, and all other plastics

They always played la lotería 2

The cockroaches in the cracks of their bathrooms didn’t bother them (as long as their children slept)

The insults on the streets didn’t bother them (as long as their children didn’t hear them)

The hunger that hit them exactly at 3 p.m. didn’t bother them (as long as their children were satisfied)

The confusing English on their legal papers didn’t bother them (as long as their children always translated)

The unhealthy food they had to eat didn’t bother them (as long as their children were alive)

They loved saying cuando yo me muera . . . 3

They loved saying uno nunca sabe 4

They loved putting all the pots and pans in the oven

They loved putting all the plastic bags in the cabinets

All of them died before seeing their family back at home

All of them died before being able to afford their own houses

All of them died before ever learning English

They died peacefully by their American families’ side

They died with faith in God and what He has planned for their children

They died with satisfaction, knowing it was worth coming to America

The American hatred of them kept them awake like a drug

The American dream put them to sleep like a drug

They were all buried under the same sky

Cause of death: dreams of the horizon

2 The lottery

3 When I die…..

4 One never knows

GRADE 12 . PERSONAL ESSAY

IIf I had to choose the first thing that comes to mind when I think of what hair means to me and my culture, I’d have to say “hair oil massages.”

In Hindi, the universal language of the motherland, you would say “” (pronounced as: Tel Maalish), Tel meaning “oil” and Maalish meaning “massage.” And in Tamil, my mother’s language, you would say “ ” (Enney Macaj). I have never been able to speak either of these languages fluently. Growing up, I was never taught because my parents strongly believed that if they spoke to me in their languages, I would never learn English and therefore struggle when it came to acclimating to school. Although speaking was never within my ability, by simply hearing these two languages constantly, the understanding aspect began to form within my naive brain. I regret not knowing the language. I think they regret it too.

Typically, you must always put coconut oil in the concoction. Coconut oilis very good for Indian hair especially as it nourishes, moisturizes, and keeps that long soft luscious hair sleek and shiny. We use the brand of 100% pure coconut oil that probably every single brown kid has in their house somewhere. You can only purchase India’s No. 1 coconut oil, Parachute, at the Indian grocery store. In New York City, Jackson Heights, Queens is where you shop for all the desi goods that were imported from the home country.

Whenever my grandmother (Pati) came to Brooklyn from her daughter’s house in Jersey, I would ask for her to give me a nice warm hair oil massage, or she would offer; either way, I knew she enjoyed the feeling of caring for her granddaughter’s hair.

Castor oil is an every-other-week product that is used on our hair—a thick, slightly yellow tinted oil that promotes beautiful hair growth and strength. There is no one specific brand that we use for this oil. My aunt brings gallons and gallons and gallons of this oil and we store it in the storage room of our house. This oil is not only used for our hair, but our bodies, too, when we take oil baths on holidays or when we are sick and have to reluctantly take a teaspoon of oil straight down the hatchet. (I swear, these home remedy medicines seem gross but really really work).

Amla oil is the last oil that I would use for my hair oil massage. Dabur Amla Oil (pronounced as

“Umla”) is the brand itself, which is an oil that comes from Indian gooseberry. I never really knew until I looked it up myself because we almost always simply call this type of oil “Amla.” It’s a dark green silky wonderfully perfumed oil that ensures long, soft and strong hair, with scent you can’t find anywhere else or compare to any other thing. I could say it smells like Indian gooseberry, but I have never experienced the smell of that fruit so it wouldn’t be truthful. The Amla aroma resembles the scent of blooming jasmine flowers on a warm afternoon in my other grandmother’s (Nani’s) backyard. When it’s warm, the texture and tension that remain between the oil molecules is released, transforming it from a thick cold solution to a warm flexible one. This oil is particularly my favorite because it reminds me of where I’m from.

Now that we have covered the various types of oils that can be used, let’s talk about the process. Each oil has to be heated up to a slightly warm-hot temperature, nothing too hot, but just enough to open your hair cuticles to let the oil seep in. If my grandmother or an elder of some sort is doing it for me, all I really have to do is sit back, relax with my eyes closed, and let my Pati relieve all of the pressure that I hold on my head.

‘‘ ‘‘

MY AUNT BRINGS GALLONS AND GALLONS AND GALLONS OF THIS OIL AND WE STORE IT IN THE STORAGE ROOM OF OUR HOUSE. THIS OIL IS NOT ONLY USED FOR OUR HAIR, BUT OUR BODIES, TOO, WHEN WE TAKE OIL BATHS ON HOLIDAYS OR WHEN WE ARE SICK AND HAVE TO RELUCTANTLY TAKE A TEASPOON OF OIL STRAIGHT DOWN THE HATCHET.

Usually after a looonngg day at school, I come home and wait till the evening when Pati is watching a movie with my parents and relaxing after a long day of cooking and cleaning for her family. The

process of a is not a simple one. Applying oil to my head is something of second nature to Pati. She can do it without thinking about it, keeping her focus on the movie that my dad put on, while still managing to grace each and every hair follicle with oil. When the evening comes, I calmly approach Pati with love and appreciation for her skills, waiting for her to simply invite me toward her with a wave. No words needed. I sit on the floor at her feet, her on the couch, and wait for her to begin. Her fingers glide with the right amount of force through my scalp, rubbing the oil onto each and every crevice of my head. This is not something that is done lightly. Pati’s and aunties have no remorse for any pain or discomfort that you might be feeling through this massage, because they know that being “gentle” is not gonna cut it. She rubs back and forth with the palm of her hand and the tips of her strong fingers dig into my scalp, releasing the tension that I hold in there. Then, once she has finished at the root, she slides her fingers down into the rest of my hair, breaking apart the knots that have formed, and friction-palming the warm oil into my hair. (Frictionpalming is what I like to call that movement where you put your hands together and rub them back and forth like an evil genius, only with enough force to create heat. I have heard some white people say that

this method is “bad” for your hair as they say it causes “friction” or something, but if my Pati does it, I know that it’s the right way.) Toward the end of this hair oil massage, she takes all my hair into one ponytail, wraps it around into a long twist, and then begins to slap my head all around the perimeter. I know this may sound odd but I promise it isn’t. After all the scalp scratching, rubbing, knot untangling, and the occasional and unintentional hair pulling from the root, my scalp feels raw and itchy, which is where the head hitting works magic. It feels soooooo good. Truly my favorite part.

All of this is done without one inconvenience. I think Pati doesn’t pay as much attention as some may think. This is understood muscle memory for her, as it was for her mother, and those before her. There will never be a time when she denies my sweet loving granddaughter request for a . Pati embraces me as I sit in front of her and feel the nurturing that seeps down through her strong fingertips and into my tender scalp. This is culture. This is family.

ELSIE WM GRADE 9 . POETRY

SSHE LOOKS TO THE FAR-OUT CITY through her fogging window. the city calling her name as it always has and always will. the bright lights bleeding out the stars, the dark buildings housing sleeping people in their deep bellies, the slow clouds gliding across the dark sky. she yearns for that place though she is living there. she longs to be out in the cool breeze and the soft drizzle of water. she needs to be soothed by the low rumble of cars and people trudging along but hates it when it gets too loud. she longs for the wind in her hair but is annoyed with the way it messes it up. she wants the taste of the city on her tongue but is dissatisfied with the taste of gasoline and dirty air.

JACQLENE S GRADE 12 . PERSONAL ESSAY

Why do you feel nonexistent, pointless, and forced—like I’m floating through a day that’s a figment of my imagination? Once Halloween comes around, I know you are four days in the future and I dread your approach. Your presence fills my mind, body, and soul with dread, grief, sadness, and guilt. Guilt because I can’t just be and exist, but I have to be “happy” and “excited” that I’ve lived another “year.” I still wake up with crust in my eyes, have homework due in a couple of days, have to ask my parents to go anywhere, and have dishes to wash at the end of the day. Nothing’s changed. Age truly is just a number.

Dear Balloons,

Why do you deflate two days after my birthday?

You are alive and plump the day of, halfway dead the next day, and then shriveled and flat like my fingers after spending thirty minutes in the shower. The water dripping down my face blends in with the tears seeping out of my eyes. Nobody can see me, I am silent. I romanticize all the glitter and glamor, but I don’t even remember the last time I experienced real sparkle on my birthday. You, Balloons, are supposed to be there to add color, sparkle, light, and delight to a

day I dread. A day that only really technically exists for twelve hours—the twelve hours I spend wishing I was sleeping instead of dreading the sun’s rays peeking through my curtains or getting constant messages and phone calls. Balloons, everyone loves to play with you but I never get it. Why waste money on the helium just for it to be released into the open air and disappear into the clouds? In all honesty, it’ll probably get stuck in a tree and maybe kill a bird.

Dear Candles,

You reek of charcoal, jumbled thoughts, and awkwardness. Why must I sit in front of you surrounded by a group of people singing to me? Why do I need to blow you out? In my inhale and exhale nothing changes; I don’t even believe the wishes I make will come true. You are just a prop, a placeholder for I-don’t-know-what. Your wax oozes down your side with each second, stopping and hardening right before it reaches the tip of the H written in icing. I used to care where I put you on Cake. You couldn’t be blocking my name or the cursive “Happy Birthday.” If there were more than one of you, you all had to be spread out evenly. Usually, my mom just looked through a random

plastic bag in the medicine cabinet to find you already used and ashy. Now, you’re often an afterthought. You’re just a little added pizazz to Cake. If anyone truly wanted to, they could light a piece of paper and just stick it in Cake. The fire is the star of the show, and your wax is a supporting act. But that wouldn’t be safe. I get it, and I’m sorry. But I also think you like it. You like your few seconds of fame helping the fire live and then getting picked out of Cake with icing on the bottom of you for someone to lick. Your job is done, mission accomplished. You can now go back into your Ziploc bag in the medicine cabinet and build up ash until the next birthday.

Dear Cake,

You are sweet and yummy and make me want water afterward. You’re the second best part of Birthdays. I feel bad that my awkward energy radiates onto you when I am surrounded by a cacophony of tired singing every year at the dining room table in the purple-painted living room. I used to get you from BJ’s: rectangular, bigger than necessary, and with that gentle, silky smooth strawberry buttercream. I got you for that one birthday party I had at the Regal Movie Theatre on Court Street. Just like my birthday party era, not too many years later that movie theater was shut down.

Around the same time, BJ’s decided to discontinue you. I ponder your legacy every year. You were a safe option, and easy, and cheap. Nothing to worry about there. As life always seems to have it in for me, I can’t have it safe and easy. Now cheap, it depends on how you choose to interpret that one. Except this year, you were frozen and dull.

Dear Family,

I’m sorry but you always seem to make Birthdays worse. I always feel suffocated by your expectations and lack of consideration, and I’m forced to participate in meaningless traditions that do nothing to contribute to Birthdays being any good. Why must you feel the need to say how cranky, miserable, and ungrateful I am? All those things may be true, except it’s not for no reason. I don’t need a nap, or to fix my face, all I need and want is to be left alone. I want a say in what I do and don’t do on MY day. When and why did you stop giving me gifts? I’ve mentioned so many things that I’ve needed or desired and have not been given one. I don’t feel like you see me, or know me. Why must my three cousins come over from around the corner just to sing a meaningless song, for me to cut a pointless Cake, and for them to enjoy it all more than I do? It feels like it is everyone and anyone’s day but mine.

Dear Gifts,

You are the best part about Birthdays, and occasionally the worst, but we’re gonna look at the glass like it’s half full this time! Getting carefully thought-out gifts, with things I barely mentioned, especially since I don’t talk about myself much, is heartwarming. I get to see who knows me, and my likes, dislikes, wants, and needs. It never matters to me how much money someone spends, but what truly matters is the care and love expressed through you that make me feel seen and appreciated. I love a good card or letter. Handmade, on wrinkled looseleaf, or copy paper. Bleeding ink, erasure shavings, perforated edges. The less perfect the better. Those words on the page are intentionally chosen, written, and placed together. Words that remind me of my place in this world, who I am, and who I should continue to be. In the moments of uncertainty and insecurity, you, Gifts, repair and restore my confidence in myself, my friendships, and my relationships.

Gifts are physical representations of how closely the people in my life listen to and pay attention to me, my interests, habits, and desires. Often around my birthday, I am reminded of how much effort I put into the relationships in my life and how that effort is not reciprocated. The gifts I get aren’t as thoughtful or intentional. Like someone just searched up a gift

for teenagers on Amazon and purchased the first thing that came up. People rarely know my favorite snacks, have to ask me my favorite color, or just plainly ask me what I want for my birthday. It stings.

Dear Parties,

I haven’t had one of you since I was maybe seven years old? It’s been so long I don’t remember when I had you or what we did. Maybe the movies? Chuck E Cheese? It was a memory I had and buried. I’ve attended when friends, classmates, and family friends had their versions of you, watching them run around free, happy, and young. I’ve jumped up and down on plenty of bouncy houses, feeling the air from a small slit in the plastic rush right into my face when I slipped and fell. I’ve watched plenty of movies with my kid’s snack box of buttery popcorn, ashy fruit snacks, and a random soda. I’ve held laser tag guns, made pottery (I have no clue where those pieces are now), made slime, and been to a firehouse. At events, especially yours, on a day that was supposed to be about me, I grew to despise the attention and responsibility I felt for everyone around me.I don’t like carrying that weight so I’d rather not have a birthday, get balloons, put candles on a cake, be with family on November 4th, get gifts, or have a party at all.

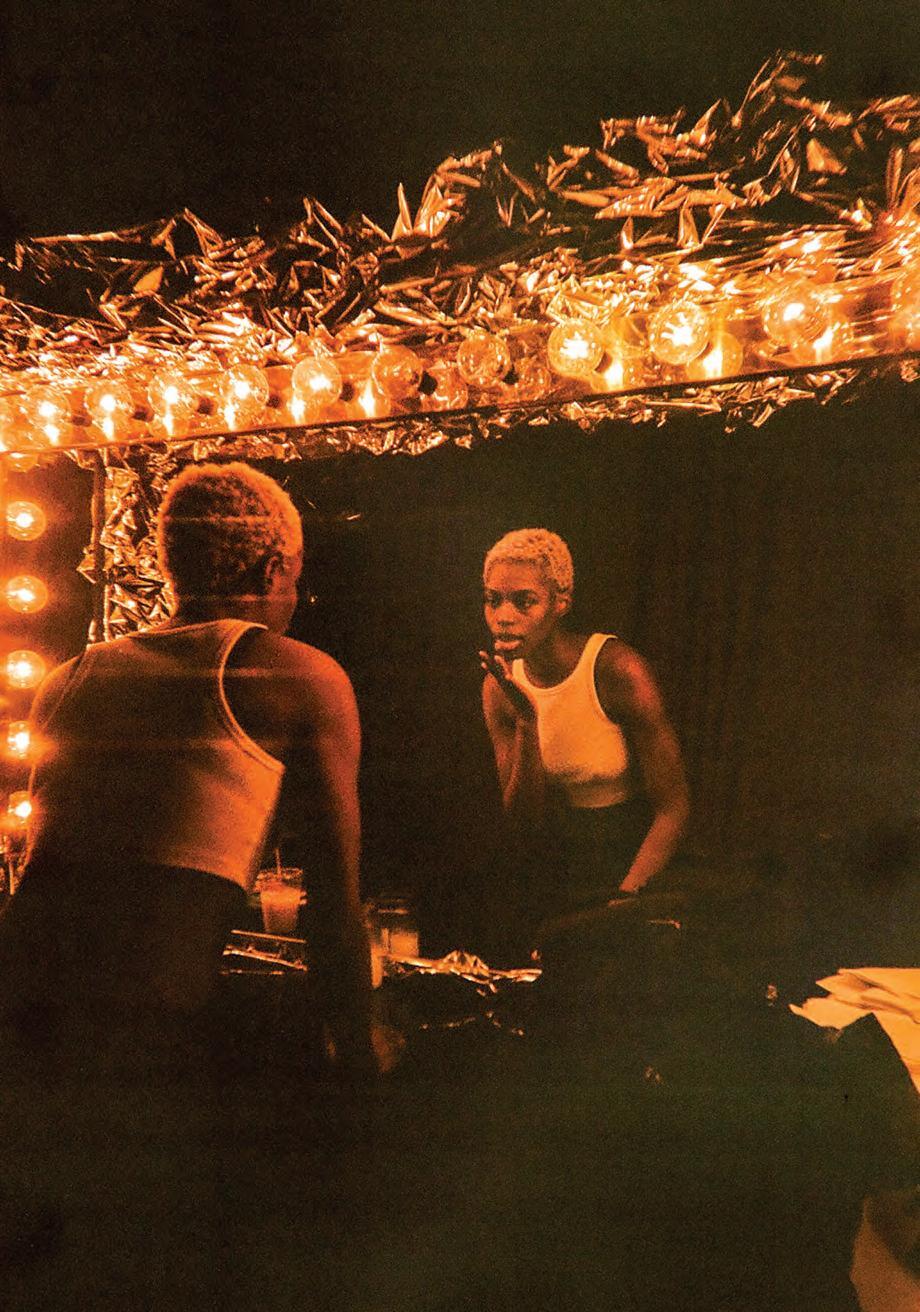

K Grade 12 , Photograph

GRADE 12 . FICTION

SLIP FROM MY LOG as sunlight once again creeps across the forest floor, pondering, as I usually do, the vastly complicated nature of the universe. Why did the ineffable powers above facilitate the constructing, and subsequent positioning, of all lives and matter in this world? What joins the teeming mass of organisms that collectively assigns the label “home” to this humble stretch of trees and green? And how is it that I, in my über-complex biological mechanisms and thought processes, have been placed here to preside over it all?

My daily ruminations are quickly interrupted by the scent of today’s meal: some tasty Bacillus a few hundred paces away through a winding maze of trees, bushes, and insects. The common caterpillar would have no hope of navigating these obstructions before it perished, but not I; I am famous for my maze-solving abilities. I set off, spreading through the forest.

Before long, I sense a thick patch of fungi before me. Many confuse me for a fungus; at the sight of these pathetic posers, rage pounds through me. Ganoderma yowls silently as I rip through it. I gouge

gaping holes in the fanned-out Matsutake, wreak seismic destructuralization in the spindly trunks of Chanterelle.

My kind and I are not, in fact, simple multicelled organisms of the rigid variety. No: we were all

‘‘ ‘‘

WHEN THE PROUD CALL TO ENVELOP THE LANDS IN OUR INTELLIGENCE AND SUPERIORITY RANG FROM TREETOP TO TREETOP, WE BOUND OURSELVES TOGETHER IN MIGHTY GROUPS OF VAST, ROLLING NETWORKS OF RACING SIGNALS AND PROBING EXTRACELLULAR BIOLOGICAL MATERIAL.

single-celled organisms, once, but when the proud call to envelop the lands in our intelligence and superiority rang from treetop to treetop, we bound ourselves together in mighty groups of vast, rolling networks of racing signals and probing extracellular biological material. Our abilities to locate food, sense light, and tell time are but a fraction of what elevates us above the common landfolk—what secures our destiny as the dominant biology of our hemisphere.

I abandon the smoking remains of Ganoderma, Matsutake, and Chanterelle and forge farther, keeping to the shady sides of trees.

An ant colony passes by, the undergrowth bowing to accommodate them. They scramble to keep rhythm and pace with one another—unlike me, they cannot merge themselves with one another, passing on knowledge, advancing their dominance. They are forever doomed to be in conflict with one another. I broadcast as strongly as possible: Silly ants! You have no sense of intercolony coherence! Also, your features are both impractical and unsightly! Who needs antennae when you have pulsing yellow feelers, like me?

The cloud of ants curves to give me a wide berth. I sense some antennae drooping, some limbs

dragging, despondent, in the dust.

Once the ants have marched away, I forge onward: around a tree, through a bush. Past another patch of Chanterelle, towards whom I squirt some mucus. Chanterelle always gets too big for its birches.

Before long, I spy an old pal of mine: Venus Flytrap. It stands above the undergrowth like a gaping mouth, the striking red gradient on the fold of its lobes tantalizingly visible. Venus Flytrap is a fake. All the beetles and spiders and squirrels think it can think for itself, but that’s nothing like what it does. Venus Flytrap uses hairs on its lobes to sense prey, and then, like a leaf contracting in the cold, it closes its mouth. That’s nothing compared to what I do. HA-HA, Venus Flytrap. You can only perform a single task—that is, close your lobes when you detect food within them—that is, engage in thigmonastic behavior!

Venus Flytrap closes its lobes around a Cochliomyia Hominivorax and chews mournfully. I skirt on, satisfied.

Next, I pass a small patch of grass. Grass! You can’t even move! I swarm Grass and eat some, for good measure. I make fun of Grass every day, and it’s forgotten by the next. Of course it’s forgotten—it

can’t remember things like I can.

Soon enough, I locate the patch of Bacillus, which is feasting on the decomposing remains of some apple. I slink steadily toward it.

Something snags the corner of my awareness. It’s massive—much bigger than any Ganoderma, Matsutake, or Chanterelle—and it’s moving jackrabbit-fast toward me. I scramble away, but I am the slow crush of lava to the darting wings of a hummingbird. In an instant, the thing is near me. And now, niggling in my consciousness, is another organism, of similar proportions to the first. I freeze.

The first organism looks at me. Rather, it looms over me. I imagine it sending out intangible feelers of its own, prodding at me, judging me. It then gestures toward the second organism. Come here, it seems to be saying to its companion. Come, look what I have found.

The two stand there for a moment. I hope they’re marveling at my wondrous physique. Then, the second one lowers itself and gets very close to me. It wriggles. Its friend makes a loud, high-pitched sound, like the twittering of a bird. The realization closes on me like the lobes of a Venus Flytrap: They are making fun of me. They think of me as a less valuable organism than they are.

I spread feelers towards the Bacillus, attempting to communicate to these organisms my complexity of thought.

Astoundingly, they do not react. These organisms think slightingly of my intelligence. I maneuver away as quickly as I can.

Which is, to say, much too slowly. Using a long, spindly protrusion (I must say, this thing has mightily

‘‘ ‘‘

THAT’S NOTHING COMPARED TO WHAT I DO. HA-HA, VENUS FLYTRAP. YOU CAN ONLY PERFORM A SINGLE TASK—THAT IS, CLOSE YOUR LOBES WHEN YOU DETECT FOOD WITHIN THEM—THAT IS, ENGAGE IN THIGMONASTIC BEHAVIOR!

fewer feelers than I), the second organism plucks a stick from beside me and drives it into my body.

In the entirety of my long, triumphant life, I have never had to contend with such a disaster. Parts of me—single nuclei, who are themselves their own beings—are pulverized into specks of unfeeling yellow dust. Whole globs of myself are torn away, raked off in clouds of dust like ants carried down a raging river in a storm. I feel their absence in my sudden loss of perspective—my exceptional awareness of living organisms and light dulls and I am unable to feel far beyond me. I am isolated within myself, at the heart of myself; I am trapped in a mold with just myself for company.

I am violently turned over again and again, cartwheeling through crumbling dead leaves and the rotting carcasses of beetles. Every broken-off nucleus I feel sharply—it pains me—

And just like that, the massive organisms are gone. I send out a single, pitiful feeler—I can move. Barely. I feel a rush of strange gratitude.

In my shrunken state, I slink from the scene of my humiliation.

On my way home, I pass Grass. It waves at me, blowing in the wind, having forgotten already my morning scorn. I pass Venus Flytrap, who is

‘‘ ‘‘

IN THE ENTIRETY OF MY LONG, TRIUMPHANT LIFE, I HAVE NEVER HAD TO CONTEND WITH SUCH A DISASTER. PARTS OF ME—SINGLE NUCLEI, WHO ARE THEMSELVES THEIR OWN BEINGS—ARE PULVERIZED INTO SPECKS OF UNFEELING YELLOW DUST.

crunching a Gasteracantha Cancriformis with eight thrashing black legs. As I slip back into my log, I glimpse a brigade of ants who march nearby, straight-lined hip-to-hip, their own thousands-strong body trampling the forest floor underfoot.

Thinking about the vast turnings of the world, I give myself over to sleep.

I I’M ON LINE for the ride and the line is moving moving slowly but also quickly and my family is laughing and I’m laughing and then we’re on the stairs and then we’re about to get on and I AM ON THE RIDE! it starts moving backward and then forward and we’re going up super fast and we’re twisting and turning and I’m screaming and my brother is screaming and the wind brings tears to our eyes but we’re still smiling and I’m laughing uncontrollably and it’s been less than a minute but suddenly the ride is over.

M My irrational fear of death has not allowed me to live in my now and my real self. I find myself not engaging in deep conversations with my loved ones, always answering with indifference when asked “How was your day?”, cutting the conversation short. As I complete my daily activities, I fall into the pattern of thinking about the next task at hand, trying to make something of myself before it’s too late.

Maybe it’s not irrational, when the women in my family are dying from the same type of sickness, when someone who looks like me is killed, when the candle in front of my neighborhood deli always seems to have a rotation. Some part of my fear must be valid.

In 2020, my aunt died of breast cancer, leaving her two kids under the age of ten. She was forty-five when she died and had just started to ground herself. She left the world with “so much left to give” in my mother’s words. The ironic thing about death is that people describe it as something that happened randomly. Yet, as she lay sick in her bed, her body failing to respond to medication, we knew death was going to take her eventually, we just didn’t know when. With a long history of breast cancer taunting us, death was something that no one else was prepared for. This possibility looms and lurks over me, chipping away at my hope day by day.

“Mo ara re.” Know yourself, as she always said. I channel her wisdom and skill of always knowing the right

thing to say. Trying to make up for the fact that this grief will carry heavy as I grow into a woman myself. Unfortunately, she gave me other things to carry along with me. She gave me a premature epiphany.

The sight of an older person by themself breaks my heart. Even if they are just sitting down living their life, a part of me assumes the worst of what life has thrown to them. I wonder whether they go home to a loving family, whether they’re still working even if their body says no, or even whether they’ve lived a life well spent. I think about how easy I feel like my days have quickened and gone by and assume they feel the same way. I tear up.

Because I have an older father, my father’s and my age difference has always been a determining factor in our relationship. As we both grow older, the obvious difference in personality remains at the top of my mind. Loud arguments, quiet resentment, and stagnancy. I can never remember a time where our relationship has been good, making a part of me think about the what-ifs. Maybe there is more depth to him than he shows. However, it’s been seventeen years with the same pattern. Why hasn’t he shown any difference? He tells stories on the living room couch of his compound back home with so much happiness that I wish he would radiate toward me. Telling stories of his everyday teenage life like the memory is a

long-lost friend he is reuniting with. At times like this, the age difference is not the only gap, the emotional gap seems to show itself as he mentally reconnects with the memory, leaving my physical being there. I value communication no matter what form it seems to present itself in: toxic, over text, in person, whispers, or yelling—and so I sometimes find it hard to believe how I was raised by someone who sees any type of communication as useless. When he finds another thing wrong and holds grudges against me, a part of me despises the wrinkles on the corners of his eyes that supposedly hold wisdom. What life experiences has age thrown at him that don’t make him want to change or take a risk?

We all hope to live to the expected lifespan, but eventually death betrays age and does its own thing. Then at that point, age manages to lose its meaning. When I was ten, my parents asked me to wash the dishes, redefining what age meant for me. A responsibility that wasn’t entirely about my upkeep. The exponential growth of that path sticks with me. Worrying about the soapy suds running down my forearm escalated quickly to worrying if my little brothers like the meal I made for them. My responsibilities became much greater, two whole humans under my care. Their homework assignments carry the future of their education, so I try to instill the habits I struggle to uphold myself: “Do your homework on time,” “Make sure your handwriting is neat,” “Cross your t’s and dot your i’s.” The double digit monster lurks over me telling me that this is what I have

to do and reminding me that the number one in front of those double digits is temporary. Two comes along and takes its place and then comes three, then four, then five, and then six, seven, eight, and then nine, and the very few who make it until ten. I can’t expect a “thank you,” because this is what’s expected of me.

As my tween years escape from under me and fifteen comes around, another future is now in my hands. Adulthood lurks around the corner. How can I make my mark? Make sure that I’m not missing the present by anticipating the future? My responsibilities never seem to let these questions escape my mind. I’m left wondering whether my new age of seventeen has left me sucked dry.

A pessimistic part of me imagines myself at age twenty-one, out of college, still figuring out what career path I want to pursue—all the while living with my parents while they stare at me in disappointment, reminiscing about their once-gifted child. As the stages in life start to escalate, so do the tasks. At some point, those defining numbers become a template that is hard to stray from; soon after, everything is set for me and you. As I complete another year in life, the cultures and communities I am surrounded with all expect something new out of me just because of this number.

I’ve reached a point where it feels childish to whine about how the coming of age movies lied to me. I’ve come to the age, what’s next?

ARDEN B Grade 11 , Photograph

she wants to be naked after Angel Olsen

DEVRA G GRADE 11 . POETRY

S THE DAY SHE WAS / born some kind of forced / vulnerable, shivering in the dark, and i’ll / probably join her one of / these days—blood, bone, breath—