A PUBLICATION OF THE BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY

A PUBLICATION OF THE BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY

BENTLEY STAFF REVEAL WHAT HAS MADE A LASTING IMPRESSION ON THEM FROM THE LIBRARY’S INCREDIBLE COLLECTIONS. READ THE FULL STORY ON P.16.

Robben W. Fleming, the ninth president of the University of Michigan, was known for his empathy in the face of conflict. See the full story on p. 4.

From World War II to Vietnam, Robben Fleming’s views on war revealed a deep understanding of the challenges faced by those called to fight. His experience defending German teenagers showed him how young people’s lives could be cut short by the decisions of their elders.

Lucinda Hinsdale Stone was a tireless champion for women who wanted to attend college and work as professors in an era when men dominated university campuses. A teacher, writer and suffragist, she changed the face of the University of Michigan—and beyond.

The Bentley is packed with incredible primary source materials, from maps to photos to letters and more. Many of these special holdings have made an indelible mark on the hearts and minds of staff. We’re excited to show you some of the items that staff call favorites.

DIRECTOR’S NOTES

1 More than Materials

ABRIDGED

2 Select Bentley Bites

IN THE STACKS

24 Atomic Connections

28 Sleuthing the Story Behind a Photo

30 Ford on the Field

31 An Ill-Fated Voyage PROFILES

32 The Gutenberg Bible and Beyond

33 “I Know This Place”

BENTLEY UNBOUND

34 On the Fly

36 A Plucky Bunch

What gives the collections at the Bentley meaning? Turns out, the library is only of use when people use it.

WHAT IS YOUR FAVORITE THING AT THE BENTLEY?

In this issue, you’ll hear from library staff about what they think are some of the more remarkable materials from the archive. It’s everything from a small note tucked into a collection of papers to whole gigabytes of online materials.

Staff have learned about these materials by acquiring them, processing them, pulling them for patrons, digitizing them, researching them, writing about them—and more.

It’s this hands-on use of the collections that gives them meaning. Without people engaging with them and understanding the materials in the archive, it’s all just . . . stuff.

Of course, it’s not just Bentley staff who give the collections meaning. In this issue, you’ll read about one researcher who may

have discovered heretofore unidentified letters from famed physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. The undated letters, signed simply “Robert,” were written to U-M physics professor George Uhlenbeck on the eve of World War II and relate to Oppenheimer’s discoveries around fission. You can read more about these letters—and our new efforts to authenticate them—on page 24.

There’s also a story about the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the tragic shipwreck, and one researcher has not only used Bentley materials to better understand what happened to the ship that fateful night, but he also donated his materials to the Bentley. This will help researchers who are interested in learning more about the topic in the future.

And that’s the point of so much of what we do, really—to help people better understand and use what we have here.

That’s why we’re in the process of redesigning our website and creating more online guides to find materials. It’s why we’re continually updating our finding

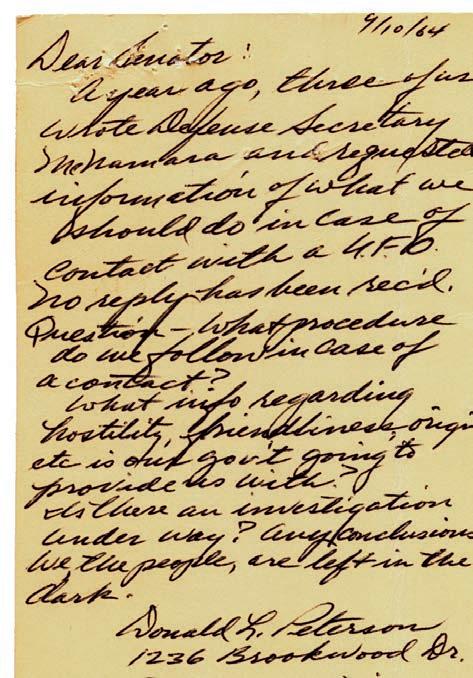

(Left) Many letters from famed physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer survive at the Bentley and, excitingly, there may be even more than were previously known.

aids, which are like a table of contents for what you can find in a collection. It’s why we’ve increased our public programming and faculty outreach. It’s why we bring materials into the classroom so U-M students can experience the awe of actually touching history.

The part of this work that I’ve always loved is when all our efforts affect people in the present. Yes, the stuff is important, but caring for these materials is ultimately in the service of people.

Every day, people come into the library’s reading room or interact with the collections online to create new knowledge, to teach students about the past, to find their ancestors, and to piece together the histories of their communities. Each time this happens, we come a little closer to fulfilling our vision of connecting people to materials that help us explore the context of our lives, discover our stories, and hold each other accountable for the future we are creating.

Alexis Antracoli Director

10,850

Number of moving image recordings in Bentley holdings, 49 percent of which are VHS tapes.

3

Number of new faces on the Bentley’s full-time staff. Please help us welcome:

Gregory Parker, Director of the Detroit Observatory

Isabel Planton, Archivist for Reference

jay winkler, Archivist for Athletics

Hoof it over to the John Phillip Berner collection, which is saddled with this image from Berner’s time at Camp Custer in 1924. Berner participated in Citizens’ Military Training Camps, which were annual programs that allowed men to receive military training without being compelled into active duty. No word on whether this horse and rider were told to rein it in.

U-M’s very first varsity softball team is pictured here in 1978. This team helped pave the way for a softball legacy that includes 11 Big Ten tournament championships. Fun fact: Former U-M softball coach Carol Hutchins led her teams to the most wins of any coach in any sport across the history of U-M.

HANGZHOU, CHINA

MÖNCHENGLADBACH, GERMANY

FREMONT, OHIO

MANILA, PHILIPPINES

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

Some of the locations visited in this issue of Collections magazine.

Two students were caught trying to pry loose and steal the Block M from the University of Michigan Diag on March 15, 1964, but were caught by onlookers and arrested.

Forget about postal trucks; imagine your mail being delivered by a dog sled! This 1910 postcard shows a dog ready to pull a U.S. mail sled from Cheboygan, Michigan, and is from the Bentley’s historic postcard collection.

“Essential reading for all who have both the curiosity and courage to wade deeply into the troubled waters of this nation’s history relative to the education of Black Americans.”

The Block M suffered some damage from the crowbar the students used (which was also stolen) and was temporarily removed for repair. When asked why they did it, the students told The Michigan Daily they were drunk and it was a joke.

A recent review of the new book A Forgotten Migration: Black Southerners, Segregation Scholarships, and the Debt Owed to Public HBCUs. The book was written by Crystal Sanders, an associate professor of African American studies at Emory University, and tells the story of “segregation scholarships,” citing the Bentley’s African American Student Project database.

Matinees showing at U-M’s Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre in May 1929.

n Photos of historic U-M alums n Pictures of relatives who were U-M students n Glimpses into the history of campus life

Did you know that many Michiganensian yearbooks have been scanned, and are available online? Browse past issues here: myumi.ch/W2yDA

U-M’s ninth president opposed the United States’ war in Vietnam. His papers at the Bentley reveal how his experiences in an earlier conflict showed him firsthand the tragic loss of young people.

BY KIM CLARKE

First Lieutenant Robben Fleming dug in his heels. No, he told his commanding officer. This was an impossible order to follow.

The Vietnam War was tearing apart the campus. In his eyes, the United States’ involvement in Southeast Asia was consuming the national budget and fracturing society, while the government was drafting young men—often poor and dark-skinned— into combat.

Encouraged by left-leaning faculty and backed by his executive officers, President Fleming decided to speak out. He chose an anti-war teach-in, and an audience of 5,000 people squeezed into Hill Auditorium, in September 1969.

The war, he said, “is a colossal mistake”—one that was robbing the country of its young people for a questionable cause.

“Death on the battlefields of Vietnam is not a statistic,” he said, “it is a tragedy in the lives of a whole network of human beings.”

Fleming was a World War II veteran. One of his most challenging assignments as an Army lawyer had been defending two German teenagers charged with spying on U.S. troops.

When he told the Hill Auditorium audience, “The youth of a country are always the wave of the future,” he may have been thinking about 1945, a firing squad, and Heinz Petry and Josef Schöner.

It was late March 1945. The 28-year-old officer was moving through western Germany as part of the Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories, or AMGOT.

Fleming had earned a law degree just before the U.S. entry into the war and joined the National War Labor Board. Despite the opportunity for a draft deferment, he enlisted in 1943 and was sent to the European Theater. (“The young men of my generation were going into the service, and I could not in good conscience stay out,” he wrote years later.)

As Germany began collapsing and communities surrendered, Fleming and his fellow AMGOT soldiers worked to keep cities and villages functioning so that U.S. troops moving toward Berlin would not be at risk. That work involved rationing food, treating the sick, and providing a semblance of police, jails, and a court system that upheld justice and due process—democratic principles the Allies were fighting for on two fronts.

“The hearts of the cities were gone. They were grey destroyed masses,” Fleming wrote in GI Government, an unpublished memoir in his papers at the Bentley. “On the walls were mute reminders of the recent exit of the Nazis. Everywhere one saw signs reading, ‘Your greeting is “Heil Hitler”; ‘Long Live Hitler’; or ‘Stalin speaks to Germany.’”

Now, Fleming had been ordered to Ninth Army headquarters at Mönchengladbach, near Germany’s border with the Netherlands, to defend two German boys charged with espionage after they’d been found hiding near American soldiers. Conviction in a U.S. military court meant execution.

Over his objection to being handed a death penalty case (“since when did the Army listen to the preferences of lieutenants?”), Fleming was further frustrated by the “physically impossible task” of having only a half-day to meet the teens and prepare a defense.

Heinz Petry and Josef Schöner had been arrested in late February. While Fleming never named the teens in his papers, contemporary military and news accounts identified them. He met with the boys on March 28, a day before their trial.

“One of them was a slight blond boy with nice wavy hair and a very boyish face,”

he wrote. “The other was a taller, huskier, dark-haired boy—also a nice-looking kid.”

Both boys were 16 years old.

Fleming had little to work with, as Petry and Schöner had already signed confessions. But the teens had a backstory.

They told Fleming they had been conscripted into forced labor. After running away, the boys were captured and sent to a penal camp for Hitler Youth. Once there, an officer offered a way to clear their records: Sneak across enemy lines and look for U.S. artillery positions.

They were poor spies. American soldiers captured Petry and Schöner less than 24 hours after they set out on their mission. The boys said they had changed their minds almost immediately after realizing how dangerous it was.

“Both of them were, I supposed, more or less the victims of the vicious Nazi system,” Fleming wrote.

As Hitler rose to power in the 1920s and ’30s, he aimed to Nazify public education and a robust network of youth organizations that had been a hallmark of the German republic.

For children ages eight to 18, their upbringing included compulsory organizations that indoctrinated them in Nazi ideology. Parents who balked at their children’s conscription faced prison. Boys the ages of Petry and Schöner were in Hitler-Jugend, or Hitler Youth; at 18, they would move into the German Army. The Third Reich also set up Adolf Hitler Schools, which were seen as elite institutions for teaching young people leadership skills that would serve the National Socialist Party and society. Petry was sent to an Adolf Hitler School when he was 13.

Despite his sympathy for the youthfulness of Petry and Schöner, Fleming said their actions were wrong, a conviction that comes through in his archived correspondence to family members. “If they had carried out their mission and

(Previous spread, foreground) As a wartime Army attorney, Robben W. Fleming served with the Corps of Military Police.

(Previous spread, background) War-related destruction in Cologne, Germany, in 1945.

(This page, background) As U-M president, Fleming often met face-toface with students who were protesting university or national policies.

(This page, foreground) Fleming’s administration stretched across one of the nation’s most turbulent eras, including the war in Vietnam.

returned to the German lines as they were supposed to have, they might have caused the deaths of many of our boys.”

Fleming decided he would plead for mercy and ask the court to spare the boys’ lives because of their age, lack of actual espionage training, and the fact that German officers had coerced them.

The court-martial took place the next day and lasted into the evening with Fleming’s defense. With no electricity in Mönchengladbach, he argued for leniency in a room lit with candles.

Court recessed at 8:30 p.m. Fleming and his young defendants awaited the verdict.

Before the panel of officers returned to the courtroom, a military aide approached Fleming. “Hand over your sidearm,” he said.

Fleming immediately knew the boys’ fate.

“If the court wanted me to remove my pistol, it could only mean that the death penalty was coming and they did not want the boys to attempt to grab my gun,” he wrote.

The president of the court read the verdict: “You will pay the supreme penalty for your offenses so that the German people will know that we intend to use whatever force is necessary to eradicate completely the blight of German militarism and the Nazi ideology from the face of the earth.”

The candles flickered as an interpreter translated the verdict. The teens were stoic. If they had been in military uniforms when arrested, they would have been held as prisoners of war. Convicted as civilians, they faced execution. The sentence was a warning to others considering spying.

Fleming silently agreed with the court. “It is a pity to have to put these kids to death,” he wrote later, “but the Nazis are utterly unscrupulous.”

The next day, he penned a letter to Sally, his wife of three years, who was living with her parents in Rockford, Illinois, awaiting the war’s end.

“I needed you terribly, honey bunny, in the last couple of days,” he wrote. “When I need to be smarter than I really am, I always talk to you a little while and you

make me feel good, so I have more confidence that I’ll be able to do something that is going to be very hard to do.”

Fleming visited the teens in jail to prepare an appeal. Schöner had been crying, which was the first time Fleming had seen any hint of emotion from the boys. “More than anything else, they showed an acceptance of what had befallen them.”

Using pencils, each boy wrote out an identical appeal in German. “The punishment the court of justice imposed on us is too severe,” they pleaded, “we don’t feel that our debt is that big that we should receive the death sentence.”

Fleming hoped the war would soon end and the Army would commute the boys’ sentences. The teens anxiously asked how close American and Russian troops were to capturing Berlin. “I couldn’t feel sorry for them—they would have killed us—but it all seems so useless,” Fleming wrote.

Later that night, he learned of two more German teens with cases almost identical to Petry and Schöner’s. “All of which means if the Nazis are going to play this way,” he wrote, “these kids are pretty sure to get death.”

The experience rattled him even more so as it unfolded over Easter weekend. He wrestled with the conflicting emotions of protecting American lives and the age and circumstances of the boys. He repeated details of the trial and appeal in letters to Sally, his mother Jeannette, and his younger brother Jack, an Army private stationed in Texas. He poured out his thoughts in a diary. All the materials, including the teens’ handwritten appeals, are in Fleming’s papers at the Bentley.

“I suppose that sometimes it must sound like I’m doing a lot of interesting things. In a sense I suppose I am,” he wrote after leaving the jail. “But so much of it is so empty, so boresome, so without humanity.”

Fleming never saw the boys after filing their appeal. With his unit, he moved deeper into Germany and witnessed the chaos and carnage of war: bloated corpses of horses and cows, decimated cities, looting and raping by Allied soldiers, including Americans. He was morally disgusted and physically filthy. “My hair is so dirty it is stiff,” he told his mother.

Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, ending the war in Europe.

On June 1, Heinz Petry and Josef Schöner left their jail cells. The

commander of the Ninth Army, Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson, had rejected their appeal and upheld the death sentences. American soldiers marched the teens into a gravel quarry near Braunschweig.

Petry was first. Soldiers tied him to a wooden post as 12 military policemen assembled. Raising their rifles in unison, they shot and killed Petry. The firing squad repeated the process with Schöner. Army photographers and a cameraman recorded the deaths.

Fleming only learned of the executions a week afterward when reading Stars and Stripes. “I didn’t think they would be after the war was ended,” he told his wife. “I don’t believe they realized what serious trouble they let themselves in for.”

Fleming led the universities of Wisconsin and Michigan during one of the most turbulent eras of American history, including the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War. He was known for empathy and compassion when it came to the zeal of young people. Yet he did not tolerate civil disruption or violence.

After World War II, Vietnam, and his U-M presidency, Fleming again reflected on the spring of 1945, this time in his memoir, Tempests into Rainbows: Man aging Turbulence (University of Michigan Press, 1996).

“I understood the rationale for the decision, and could accept the fact that success in their spy mis sion could have cost many Amer ican lives. Still, they were only sixteen years old, the war was almost over, and it seemed a pity that they had to be a last-minute casualty of the war,” he wrote.

“I THOUGHT OF SIXTEEN-YEAR-OLD AMERICAN BOYS AND WHAT A TRAGEDY IT WOULD BE TO HAVE THEIR LIVES CUT SHORT BY THE MISTAKES OF THEIR ELDERS.”

(Background) A priest administers last rites to German teenager Josef Schöner, a convicted spy, as he awaits a U.S. Army firing squad.

(Foreground) Fleming shared with his wife, Sally, his frustrations with legally defending the young Germans as they faced the death penalty.

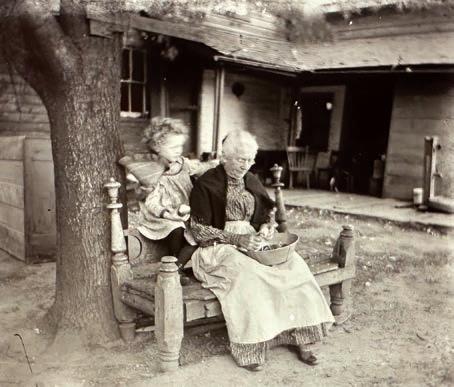

LUCINDA HINSDALE STONE AND A GROUP OF WOMEN SHE WAS TEACHING WHILE TRAVELING IN HEIDELBERG, GERMANY, CIRCA 1866–1870.

LUCINDA HINSDALE STONE WAS A PASSIONATE ADVOCATE FOR WOMEN’S EDUCATION, EVEN WHEN IT THREATENED HER REPUTATION AND CAUSED HER PAIN. RECORDS AT THE BENTLEY SHOW HOW HER TIRELESS WORK IN THE FACE OF ADVERSITY CHANGED WOMEN’S LIVES ACROSS THE STATE OF MICHIGAN.

By Madeleine Bradford

!STONE'S HOUSE IN KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN, WAS AN EARLY HUB FOR COEDUCATION, EVIDENCED BY MALE AND FEMALE STUDENTS IN THIS PHOTO CIRCA 1863–1866.

WAS A CHILLY JANUARY EVENING IN ANN ARBOR WHEN LUCINDA HINSDALE STONE HEARD THE NEWS.

IT WAS 1870 AND U-M’S REGENTS HAD MADE A GROUNDBREAKING DECISION: FOR THE FIRST TIME, WOMEN OFFICIALLY COULD BE ADMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY. THIS WAS A MOMENT STONE HAD BEEN WAITING FOR. A LIFELONG TEACHER, AND AN ADVOCATE FOR WOMEN’S EDUCATION, SHE’D BEEN PUSHING FOR U-M TO ADMIT WOMEN FOR YEARS.

She went straight from Ann Arbor to Kalamazoo and told Madelon Stockwell that she should apply to U-M immediately. Stockwell had been one of Stone’s pupils at Kalamazoo College. Stone knew she was bright enough to succeed.

At her former teacher’s urging, Stockwell became the first woman to be officially admitted to U-M, accepted less than a month after the resolution had been passed. Stone later described Stockwell as “a lone star,” representing the dawn of a new era—one that the older woman had worked for tirelessly.

She and her husband were some of the earliest advocates for coeducation in Michigan, according to the biography, Lucinda Hinsdale Stone: Her Life Story and Reminiscences, by Belle Perry.

It took tremendous effort; Stone wrote to newspapers, gave speeches, and sent endless letters. “The world is surely setting toward the higher education of women. The power of the pickaxe on the hardest soil consists in that it works with the law of gravitation on its side,” Stone wrote, according to her biographer.

Archived books, papers, and newspaper clippings show how fervently Stone advocated for women’s education. She knew better than anyone just how desperately some women wanted to attend a university, and how badly it hurt when they couldn’t.

Stone was an intensely curious child growing up in the early 19th century. She inherited her father’s habit of questioning other peoples’ assumptions, and her mother’s habit of reading. Although her father died before she was three years old, she was raised on stories about his opinionated nature from religious neighbors in her hometown of Hinesburg, Vermont, who told

her he’d disagreed with the local church and therefore “gone to hell.”

Her greatest joy was waking up early to watch the sunrise over the mountains. This gave her time to think, write, and study, away from the hustle and bustle of her family. Her house was full; Lucinda was the youngest of 12 children. She would remain an early riser all her life.

“At first I pursued my study of Greek covertly,” she wrote in her chapter of the 1874 essay compilation book The Education of American Girls . Soon, however, she wanted more.

So, at 13 years old, she applied to the local preparatory school, Hinesburg Academy. “It was a thing never heard of before for a girl—and caused much discussion—but her desire was finally granted through the courtesy of the principal, Dr. Stone. . . . Merely to express such a wish was considered fairly revolutionary,” the 1914 Kalamazoo Telegraph reported. The principal would affect her life in more ways than one.

Stone studied alternately at Hinesburg Academy and the local Ladies Seminary. Her childhood pastor encouraged her to enter advanced classes with “these young men fitting for college” at Hinesburg, according to her account in the 1891 Detroit Tribune. She wrote that she “found it entirely easy to keep up with them, besides pursuing at least two studies which they did not take into their curriculum.”

She desperately wanted to learn more. But when she said, “Oh, I wish I could go to college,” her classmates teased her until she cried. “It was a very dangerous thing for a girl to aspire toward a higher education, or even to wish she might go to college then,” she wrote.

The doors of higher education were closed to her. She never forgot how that rejection stung.

Denied further schooling for herself, Stone decided to provide education to others; after teaching briefly at Burlington Academy, she traveled to Natchez, Mississippi, to work as a governess and teacher, in 1837.

While teaching in Natchez, she witnessed the brutal reality of slavery. She was horrified to learn that the white parents of the children she taught, who acted friendly toward her, also beat the African American people that they enslaved. The violence left her heartbroken.

“From her own observations and experiences in those antebellum days Lucinda Hinsdale formed the opinion that slavery was from its primary principles utterly wrong,” the Kalamazoo Evening News wrote in a summary of her life, in 1900, preserved at the Bentley.

The teacher who formerly held her position, an anti-slavery advocate, had fled the area, fearing lynching. The three years Stone spent in Mississippi transformed her into an ardent lifelong abolitionist.

Stone moved away from the South, to Grand Rapids, Michigan, where she married the former principal of her preparatory school, the Reverend James Andrus Blinn Stone, in 1840.

The newlyweds moved to Gloucester, Massachusetts, where Stone’s husband taught at the Newton Theological Seminary. Shortly afterward, in 1843, they moved to Kalamazoo, Michigan. They would have three children.

At the time, U-M had “branch schools” that acted as preparatory schools for young men intent on attending the university. The Kalamazoo branch also acted as the equivalent of high school for young women.

Stone found herself teaching as the “principal of the ladies’ department,” while her husband led the Kalamazoo branch school, which had recently merged with a local Baptist Institute.

“There were about an equal number of young men and young women studying beautifully together, the girls always keeping up fully with the boys, until the boys went to the University, and the girls were supposed to consider their education finished,” Stone wrote.

She added: “The question often pressed itself upon me, why should co-education stop here, just at the door of our University?”

In 1845, U-M’s regents decided to cut the appropriations funding the branch school. Over the next decade, Stone and her husband transformed the school into Kalamazoo College, using their own money to fund the “women’s department.”

Stone was unpopular with the school’s Baptist leadership. Not only did she teach women many subjects also learned by men, but she also asked pupils to read Byron, who was seen by the academy’s elders as not Christian enough. Furthermore, a copy of the Atlantic Monthly (considered improper due to articles about politics and abolition) was spotted on her desk.

Compounding matters, the college buildings had been costly. James Stone was blamed for the deficit.

The Stones resigned from Kalamazoo College in 1863, and Lucinda Stone created a “Ladies Seminary” in her own home. Many of the women attending Kalamazoo College left with her.

According to Stone’s biographer, leaders from the college pleaded with her to either return or close her school, which was out-competing them among local young women. She refused. Her school expanded.

According to the book Emancipated Spirits: Portraits of Kalamazoo College Women , Kalamazoo College’s president warned her there would be reprisals. Soon, rumors were spread about her husband’s alleged affairs. Some quickly proved false; a letter with

supposed “proof” was revealed as a forgery. Still, the community turned on the Stones, as accusations flew. Lucinda Stone claimed not to believe them.

She kept teaching until her home burned down on Christmas in 1866, in a chimney fire that engulfed the upper floors, then spread. With no water in the nearby wells, and with cold causing the firefighters’ equipment to freeze and clog, their home was lost. It was enough to set Stone on a journey abroad.

She remained focused on education and traveled through Egypt, England, Syria, Greece, and beyond, teaching women about art and history, sometimes accompanied by her husband and sons, who otherwise spent their time running the Kalamazoo Telegraph newspaper.

From the late 1860s through the 1880s, she wrote about her travels, published under her initials in newspapers like the Kalamazoo Telegraph and the Detroit Post and Tribune. Her writing helped readers in Michigan imagine places they had never seen.

Her travel descriptions also reveal Stone’s contradictory views about other cultures. She insisted that everyone attending her traveling classes be respectful of local traditions, saying, “I count nothing human foreign to me.” Yet she could be prejudiced, describing women in “portions of the East” as “primitive,” without a hint of the respect she prized so highly.

Even at home in Kalamazoo, Stone knew very well that things were not perfect; not all women could access the education they wanted.

While working at the branch school in Kalamazoo, she started the Kalamazoo Ladies Library Association for women, and hosted talks by national experts on abolition and suffrage. But she wanted to do more.

So, across the mid-to late-19th century, she embarked on a quest to establish women’s clubs across the state of Michigan. According to her biographer, these clubs “fostered art, history, and literature study, lecture courses, and an intelligent interest in the best in current literature,” providing opportunities for lifelong learning.

Stone became famous as the “mother of women’s clubs.”

“These are established in almost every little village in our state,” the Detroit Post and Tribune wrote in 1883, describing the women’s club movement as “truly a new renaissance, of which it may be said, ‘dux femina facti,’” a Latin phrase meaning: “a woman leads the events.”

Stone’s impact on U-M went beyond the enrollment of Madelon Stockwell. U-M granted her an honorary Doctorate of Philosophy in 1890, fulfilling Stone’s lifelong dream of a degree. That same year, at the age of 75, she helped charter the Michigan Women’s Press Association.

Then she found a new cause: advocating for women to be allowed to become professors at U-M.

She lived to see it happen. In 1896, 55 years after male professors taught U-M’s first students, Dr. Eliza Mosher became the first woman officially granted the title of professor by the university.

After Stone died at home in Kalamazoo in 1900, women’s organizations across Michigan donated scholarships in her honor. A Daughters of the American Revolution chapter, and a senior faculty award at U-M, are named after her today.

Stone shaped the lives of women across the state of Michigan. Every woman who attends U-M benefits from her relentless advocacy for women’s admission. Kalamazoo College, which she helped transform, is a highly ranked liberal arts college. True to Stone’s prediction, a majority of colleges across the U.S. are coeducational.

“Growth is the law of every true life,” she told a reunion of her former students in 1885. “No tomorrow should find us where we are today.”

You can read Stone’s writing in archived newspapers including the Kalamazoo Telegraph, and her biography, Lucinda Hinsdale Stone: Her Life Story and Reminiscences. You can also explore the Lucinda Hinsdale Stone photograph collection, the book Emancipated Spirits, and the Lucinda Stone Vertical File, at the Bentley. (ABOVE) PORTRAIT OF STONE, CIRCA 1890. (RIGHT) A MEMORIAL ARTICLE COMMEMORATES HER ROLE AS A PROMINENT EDUCATOR.

WITH MORE THAN 75,000 FEET OF ARCHIVED MATERIALS, 80,000 PRINTED VOLUMES, 10,000 MAPS, 136 TERABYTES OF DIGITAL MATERIAL—AND MUCH MORE—YOU’D THINK IT WOULD BE CHALLENGING FOR BENTLEY STAFF TO PICK A FAVORITE OBJECT OR TWO FROM THE COLLECTIONS. FORTUNATELY, SOME SPECIAL HOLDINGS HAVE MADE AN INDELIBLE MARK ON THE HEARTS AND MINDS OF STAFF, WHO WERE HAPPY TO SHARE THEIR TOP PICKS.

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN proclaimed its intention to be a research institution with the construction of an observatory in 1854.

A year later, artist Jasper Cropsey captured the building in vivid oils, making it the first known image of a facility known today as the Judy and Stanley Frankel Detroit Observatory. The building became part of the Bentley Historical Library in 2005.

Cropsey was friends with U-M President Henry P. Tappan, who brought the 32-year-old painter to Ann Arbor in 1855 to depict the young campus on canvas. Cropsey created two paintings—one of the handful of buildings and open field that we know today as the Diag, and another of the new Detroit Observatory to the northeast of campus.

The painting is a favorite of Austin Edmister, the

Observatory’s assistant director for astronomy.

“By itself, it’s a beautiful painting by a renowned landscape artist,” he says. “It’s also really unique in that it documents a structure that is a combination of 19th century astronomical observatories and 19th century Ann Arbor architectural trends.”

Cropsey had studied both art and architecture and had an excellent reputation as an artist. “Although predominantly a painter of nature, Cropsey was also interested in man-made structures and considered them worthy subjects for his paintings,” wrote Anthony M. Speiser, director of the Newington-Cropsey Foundation. “Perhaps because of his architectural background, he often depicted buildings and other structures, elements that were usually incorporated into his landscape compositions in a manner that blended them into the natural setting.”

The Cropsey painting is on loan from the Bentley Library and can be seen at the U-M Museum of Art.

PROFESSOR

DAVID M. GATES

was a prolific diarist. A U-M graduate and botanist who led the U-M Biological Station in northern Michigan from 1971–1991, his papers at the Bentley include journals and notebooks filled to the edges with tight handwriting about events monumental (“I broke down and cried bitterly” after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy) and trivial (“meetings all day today”).

between journal pages.

Archivist Steven Gentry is a fan of the Gates papers because it was one of the first collections he processed after joining the Bentley in 2019. He also appreciates the poignancy of Gates’ thoughts through the decades until he died in 2016.

Gates began keeping a journal in 1935. Along with recording his thoughts, he tucked clippings, photos, identification cards, postage stamps, and ticket stubs

“The most powerful entry of all was that he continued journaling even as he lay dying, with the final entry in the last journal being penned by one of his children noting his passing,” he says.

IN 1961, THE KENNEDY ADMINISTRATION sent the U-M Symphony Band to the Soviet Union in the hopes of thawing relations between the two countries through music. The musicians’ warm reception is evidenced in notes that are a favorite for Olga Virakhovskaya, assistant director for collections management.

The small scraps of paper, tightly folded, “were often passed through the crowd to the performers to indicate their wish for unity or to say thanks,” says Virakhovskaya.

There were also requests. “Please play some jazz things!” reads one note. Another asks for Rachmaninov’s Italian Polka.

“This group visited during the Cold War, and here is an example of people opening up to each other even though they’re supposed to be enemies,” says Virakhovskaya, who is Russian. “It touches my soul.”

ON THE DORM-ROOM DOORS of two Black U-M students. Slurs spray painted on the iconic U-M rock. A decline in Black enrollment. This was the climate in 2014 when hate-filled flyers started appearing on campus, many of them more than just paper: white supremacists had been rigging them with harmful objects such as razor blades.

“Be careful . . . have some gloves on hand,” advised Austin McCoy, then a Ph.D. student and postdoctoral fellow at U-M, and one of the leaders of the Being Black at the University of Michigan (#BBUM) campaign.

#BBUM ignited protests and walk-outs on campus and ultimately brought a set of demands to U-M leadership, one of which was the “increased exposure of all documents within the Bentley Library. There should be transparency about the University and its past dealings with race relations.”

Part of the material relevant to the demand was housed in the archived papers of the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies (DAAS). But accessing those materials meant making an appointment and coming to the Bentley in person.

“We realize that archives can be confusing to use and, in this case, there was understandable concern that we were hiding the university’s history,” says Bentley Associate Director of Curation Max Eckard.

In light of this, the Bentley digitized more than 65,000 documents and 1,116 audiovisual materials for a total of 1.9 terabytes in content. All of it was made available online.

These digital materials are now a favorite for Eckard. “This collection is a good example of being responsive to the community. We wanted the students to know we were listening.”

VICTOR LEMMER WAS A BUSINESSMAN and historian from the city of Ironwood in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. His papers, including letters, research notes, and photographs, are favorites of Bentley Assistant Director for Reference Services Diana Bachman.

“In reference, we’re usually looking up material about others’ interests,” Bachman says. “As a ‘Yooper’ [someone born in the Upper Peninsula], the Lemmer papers was the first collection I investigated on my own to start looking at the Bentley’s Upper Peninsula holdings.”

Lemmer’s photographs show miners wearing candles strapped to their helmets, a stark contrast to modern electric lamps. The Upper Peninsula’s copper and iron deposits made mining a crucial part of its industry, and miners like these shaped Michigan, both through trade and through strikes for rights, pay, and safety.

By collecting these photos, as well as World War II correspondence with soldiers from Gogebic County, details about local buildings, logging, mining, and more, Lemmer preserved local history that might not otherwise have been saved.

A� ABOlITIONIST pOET

THE RARE AND ENGAGING Elizabeth

Margaret Chandler papers are a source of inspiration for Alexis Antracoli, director of the Bentley Historical Library.

A writer and opponent of slavery, Chandler rose to fame when her 1825 poem, “The Slave-Ship,” appeared in a Philadelphia magazine.

The papers remind Antracoli of her love of early American history, the city of Philadelphia, and the writings of young women of the early 19th century.

“While Chandler stood out from the crowd in many ways, she was well-educated, came from a family of some means, and was a successful published author and well-known abolitionist. I’m always drawn to materials that give us insight into the inner lives of young women from earlier periods of time.”

“THE ROAD STARTS RIGHT HERE, with our decisions about recycling,” says the driver of a recycling truck in a video from the City of Ann Arbor. The truck is a cartoon, drawn around an actor who is speaking lines and turning a fake steering wheel. It’s exactly the kind of public service announcement that Archivist for Digital Curation Elena Colón-Marrero enjoys.

“I like watching PSA videos from local government agencies,” Colón-Marrero says. “They are usually earnest, cheesy, and incredibly creative in a way that really captures the spirit of local government.”

Colón-Marrero says she appreciates “the effort to educate the public about recycling,” and has even used some of the tips, but that she refers to the City of Ann Arbor’s website for the most up-to-date information.

sŦUDE�� owLS

AN OWL-THEMED RECORD BOOK is a whimsical piece of student history, and a favorite of Communications Specialist Madeleine Bradford. It was created by the “Owls,” a U-M social fraternity also known as Gamma Delta Nu, which existed from 1899–1910.

According to the record book, initiates were called “fledglings,” and their password was an owl call: “to-whit, to-whit, to-woo.”

They weren’t the first with this mascot: an earlier secret society called “The Owls” fostered friendships between U-M fraternities from 1860–1870. Gamma Delta Nu claimed (without evidence, Bradford notes) to be a secret continuation of those earlier “Owls.”

“I love that there were historical secret societies themed after owls,” Bradford says. “Digging into these joyful, unexpected details, that’s part of the fun of research.”

WHEN JOSEPHINE GOMON DIED IN 1975, after decades of service to the less fortunate of Detroit, the Detroit Free Press hailed her as “the city’s conscience.”

Gomon was among the most influential women in the Motor City for half a century. And for just as long, she recorded her thoughts in diaries now held by the Bentley Historical Library, providing an insider’s view of the people and politics of Michigan’s largest city.

Gomon worked with attorney Clarence Darrow, Mayor Frank Murphy, and industrialist Henry Ford. She fought for housing and food for low-income Detroiters, promoted birth control, and helped establish the ACLU in Michigan.

The diaries resonate with Michelle McClellan, Johanna Meijer Magoon Principal Archivist. “She started writing more than 100 years ago, and yet it sounds so relatable, especially as a wife and mother juggling a busy life. She was both typical and unusual, her voice and sense of self.”

ON NOVEMBER 25, 1897, the U-M football team was slated to play the University of Chicago in the last game of the season.

Before the showdown, U-M Coach Gustave “Dutch” Ferbert received a letter from Horton Ryan, secretary of the U-M Alumni Association group in St. Louis. Filled with deliberate misspellings and a joking tone, Ryan calls Ferbert a “fraud swindler prevaricator [sic]” and says “the eyes of the San Looiey [St. Louis] alumni are upon you.” Ryan demands U-M must “knox [sic] the spots off Chick-liog-oh [Chicago].”

The letter is a favorite of Athletics Archivist jay winkler, who says it is a humanizing moment among “mostly serious correspondence about the business of operating the football team.”

Surrounded by contracts and plans to schedule football games, winkler marvels at this ribbing among friends. “It helps speak to Dutch Ferbert, the actual person who had a personality that apparently enjoyed over-the-top teasing.”

“BOTh TYPICAL AnD UNUSUAl”

MORE THAN 100

YEARS AGO, Ypsilanti farmer Ella Fuller snapped photographs of her everyday life, including her family, farmyard animals, horse-drawn buggies, and more. Ella’s photos and glass negatives live on in the archives, and they are favorites of Reference Assistant Karen Wight.

“This collection is fascinating,” Wight says, “especially for those of us with farmers in our ancestry.”

Taken between the 1890s and the 1910s, these photos provide a unique glimpse into Ypsilanti’s past, showcasing posed family portraits, alongside more relaxed, unvarnished images of farmyard life. In Ella’s photos, women laugh, and energetic children blur with movement.

“I have a real interest in genealogy,” Wight says. “I love photos like these because I know my own family lived this way.”

When researcher Walt Di Mantova came to the Bentley to investigate a possible family connection to the Manhattan Project, he found more than he bargained for regarding famed physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer.

By Jim Ottaviani

IN 1939, AS THE CONFLICT IN EUROPE metastasized into World War II, physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer penned a letter to George Uhlenbeck, a theoretical physics faculty member at the University of Michigan. In the letter, Oppenheimer discussed the newly discovered phenomenon called fission. He called it “bursting uranium” and hypothesized that it “might very well blow itself to hell.”

But in the letter, Oppenheimer also identified a problem: for this process to work, he wrote that “one should have something to slow the neutrons without capturing them.”

In other words, he needed something to slow down the neutrons just enough to allow the uranium to capture them, hold them, and cause fission—all without the neutrons being absorbed. But what?

Oppenheimer’s “something” turned out to be graphite.

Graphite became one of the keys to the success of the first atomic reactors in 1942 and, subsequently, the Manhattan Project, the massive effort led by Oppenheimer that created the atomic bomb and the nuclear age. Decades later, it was graphite that led researcher Walt Di Mantova (M.A. ’82) to the Bentley, where he did more than just deepen his knowledge of and connection to Oppenheimer; he also discovered some potentially unidentified—and scientifically valuable—Oppenheimer letters in the process.

Before Oppenheimer became a household name—and the title character, played by Cillian Murphy, of the 2023 blockbuster film—he was a promising young scientist. His friends called him “Oppie” and marveled at his myriad side interests, ranging from obscure languages to poetry to the culture of the American Southwest. And like many of his physicist colleagues, Oppenheimer visited Ann Arbor and the U-M Summer Symposia in Theoretical Physics.

Great minds in physics gathered in Leiden, Netherlands, in July 1927, including George Uhlenbeck (front row, far left) and J. Robert Oppenheimer (second row, second from left). Oppenheimer and Uhlenbeck developed a longstanding friendship and their decades of letters are archived in Uhlenbeck’s papers at the Bentley.

Under the guidance of U-M professors Harrison Randall, David Dennison, and Uhlenbeck, these symposia attracted scientists from all over the world, among them 15 past and future Nobel laureates, such as Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, E. O. Lawrence, and frequent visitor Enrico Fermi.

Oppenheimer was a repeat attendee, visiting in 1928, 1931, and 1934, and during those visits he became close friends with Uhlenbeck and his wife, Else. Even when Oppenheimer couldn’t come to Michigan, he kept in touch with them, discussing everything from the weather to vacation plans. But mostly it was science, and the letters at the Bentley are bursting with equations describing positrons, neutrinos, and other

particles that scientists discovered as they peered inside—and eventually split—the atom.

For example, Di Mantova was thrilled to discover a six-page letter from Oppenheimer to Uhlenbeck, dated April 1929, which is chock-full of dense, handwritten equations and musings. At the bottom, Uhlenbeck scratched a note in pencil:

“This is a very important letter showing that Robert had almost all aspects of [neutron] collision theory straight at a very early date.”

For Di Mantova, it was an unbelievable discovery, a “moment of holding incredibly important scientific history in your hands,” he says. And it was precisely this science that Di Mantova wanted to know more about, and its potential connection to his wife’s family—via physicists’ quest for graphite to slow down the neutrons.

The biggest graphite producer in the country at the time was National Carbon with, among others, a large plant in Fremont, Ohio. In peacetime, the graphite they produced was used for batteries. But during WWII, Di Mantova says the company “secretly provided the graphite blocks used to not only create the first nuclear reactor but eventually to produce large amounts of uranium and plutonium.”

The head of National Carbon’s Fremont plant was George Warfield Armstrong, a University of Michigan graduate from the class of 1915. His granddaughter, Polly Paulson (M.P.H. ’82), is Di Mantova’s wife.

Inspired by Paulson’s connection, Di Mantova began to research more about what Armstrong did during the war. “He was proud of his contributions,” Paulson says. Family lore has it that, exhausted after the war, Armstrong retired young. “He left it all on the field,” Paulson says, and he was reticent about discussing his role. That left lingering questions about how directly Armstrong contributed to atomic work, what he knew about the Manhattan Project, or if he had a relationship with Oppenheimer or other scientists.

At the Bentley, Di Mantova was able to view Armstrong’s alumni file, where he discovered Armstrong was a chemistry major and a member of the Tau Beta Pi and Sigma Xi fraternities, as well as the Alchemist Society. After graduation, Armstrong served in the military, and went on to Hercules Powder, where he put his chemistry background to work making gunpowder and explosives. Not long after WWI ended, and only five years after graduation, he was running National Carbon in Fremont.

“Without the decision to use graphite in the first reactors and the availability of that very pure graphite, the United States would not have been able to produce the materials used in creating the first reactors

and then atomic weapons,” says Di Mantova. “National Carbon, led by a University of Michigan alum, helped us win WWII and usher in an era of nuclear danger.”

A U-M anthropology graduate, Di Mantova deepened his background in science and technology over his career working with industry and startups. This gave him a framework to understand physics as he researched Oppenheimer and other scientists in archives across the country, and their possible relationship to Armstrong. In the process, he became familiar with the turns of phrase the scientists used in their letters, how they signed their names, what topics they gravitated toward, and more.

That’s how he came to suspect there might be letters in the Bentley’s Uhlenbeck collection that were from Oppenheimer—but not labeled as such because they were undated and rarely signed with a full name.

It’s not too hard to imagine why the letters haven’t been identified as Oppenheimer’s: like today’s

emails and text messages, correspondence between close friends of that era didn’t always include the sender’s and recipient’s physical addresses, and envelopes rarely got saved.

But Di Mantova saw plenty of clues.

Sitting at a table in the Bentley’s reading room, Di Mantova pored through folders in Ulhenbeck’s collection one by one, reading letter after letter, for hours on end.

missives to Uhlenbeck include the mundane, like this postcard from New Mexico, and the extremely important, like this 1929 letter describing neutron collision theory.

Oppenheimer was also part of U-M’s Summer Symposia in Theoretical Physics in 1931, second row, fourth from left (Uhlenbeck is next to him, third from left).

He discovered detailed discussions of beta decay and positron theory, often with Oppenheimer’s characteristic takedowns of other physicists’ papers. “I am now utterly sick of the ramifications of positron theory,” reads one undated letter. “It turns out that the whole second part of Heisenberg’s paper is a swindle.”

Oppenheimer’s fondness for the American Southwest came through as he wished Uhlenbeck would spend time with him in

Walt Di Mantova’s research into George Warfield Armstrong (inset, left) and his potential relationship to atomic work led to a discovery of potentially more Oppenheimer letters, signed simply “Robert.”

Pecos, New Mexico, instead of Ann Arbor.

Di Mantova says that even the typos are clues. “Oppenheimer was a lousy typist, which you can see in early letters. That goes away when he gets a secretary who knew her way around the keys,” he says.

And then there are the complex, handwritten physics equations scribbled onto paper in his signature style.

Many letters are simply signed “Robert,” which isn’t as conclusive as if he’d signed with his full name or his nickname, Oppie. But Di Mantova notes that even this is somewhat expected. “As his professional stature grew, Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty eventually convinced him to stop signing as ‘Oppie.’”

The Bentley is currently in discussions with Di Mantova about how to fully authenticate the letters—of which there are three. But

more in the papers of other U-M professors who participated in the Summer Symposia. “I don’t know how many Oppie letters there are,” says Di Mantova. If the three letters currently in question can be authenticated, the Bentley will move them to the labeled folder that already includes documented correspondence between Oppenheimer and Uhlenbeck. Depending on their content, the Bentley may also update its finding aid to better help future researchers.

Meanwhile, Di Mantova’s work will continue researching Armstrong, graphite, and his possible connection to leading physicists. “It’s so exciting to uncover the different relationships through this correspondence,” Di Mantova says. “It’s a critical time for world history, and it’s amazing to see what’s there.”

An unusual picture of my grandmother sparked a research quest that started at the Bentley and took me across continents. The story is still unfolding.

By Edward Mears

THE DAUGHTER OF POOR POLISH IMMIGRANTS, Estelle Mislik Mears (1909–1992) was a former schoolteacher from Flint, Michigan. She was the first in her family to attend college—specifically the University of Michigan.

She was also my grandmother.

In 2022, my father and I traveled to New York City to retrieve Estelle’s photo albums from a storage locker in Queens, to find clues about her experiences in Ann Arbor from 1931–1933.

One photo that stood out above all others showed Estelle with an Asian man in front of the former Alpha Lambda Chinese

fraternity at 1402 Hill Street, taken in May 1933. The photo was a gift to my grandmother; this man had written “To Veronica, with love, Ben” on the image in blue ink.

The desire to learn more about this photo triggered a three-year quest that brought me from the Bentley Historical Library to Hangzhou, China. Along the way, I developed a well-defined picture of my grandmother’s life in Ann Arbor, her circle of friends, and her leadership on campus. I also had an opportunity to learn about the university’s historic connections to China and the experiences of exchange students from that country in the 1930s.

Estelle was white and, during 1930s when she was at U-M, there was “a reluctance of American students to associate with foreign students,” according to Professor Ting Ni in her study Cultural Experiences of Chinese Students Who Studied in the United States During the 1930s–1940s (2002).

Yet here was Estelle in a photo having befriended an Asian student on campus.

On the back of the photograph, Estelle inscribed several notes with the date (May 1933), the photo’s location, and the man’s name, Benjamin King. I was determined to learn more about Benjamin and the nature of his friendship with my grandmother.

I began by searching for Benjamin’s name in The Michigan Daily archives. I found several articles from the early 1930s that mentioned a Chinese student with that name. Chief among them was a series from the spring of 1933 that highlighted the “International Students Conference on World Affairs” held at the Michigan Union’s ballroom that May.

For four days, students and professors transformed the ballroom into a cosmopolitan hub of global discourse, debating pressing geopolitical issues using a format and procedures modeled after those of the League of Nations.

TRIGGERED A THREE-YEAR QUEST THAT BROUGHT ME FROM

father’s occupation as “Merchant” and a home address in Hangzhou, China. He received his undergraduate degree from Hujiang University in Shanghai and was engaged in graduate studies in law and municipal government at U-M.

As an emergency contact, he listed a B.C. Dih of the Lakeland Community Church in Hangzhou and indicated his religious preference as Baptist. The file also contained letters from Benjamin requesting that the registrar forward his transcript to several U.S. law schools and to the Shanghai Municipal Government.

I learned Benjamin had spent most of his professional career at the National Commercial Bank of China in Shanghai, where he was a sub-manager and authored one of the first Chinese language books on modern banking practices in 1940. As a member of the Rotary Club, he was well-connected with top bankers and industrialists from Republican-era China and came from an aristocratic family. He also served as vice president of the University of Michigan Alumni Club of Shanghai from 1939 to 1940, while most of the city was occupied by the Japanese.

As a complete surprise, I learned Benjamin had remained in China after the People’s Liberation Army occupied Shanghai in 1949. Considering his background, it remains unclear why he did not seek refuge outside of China. Life was likely difficult for him during the Anti-Rightist Campaign and China’s Cultural Revolution, when the authorities closely monitored and questioned people with foreign ties.

This photo, uncovered in a storage locker in Queens, New York, sparked a research quest by Edward Mears to discover more about his grandmother Estelle’s friendship with Benjamin King.

The Daily also mentioned that the chair of the conference’s World Politics Commission was a graduate student named Benjamin King and the Commission’s secretary was my grandmother Estelle. This connection established the likely basis for their friendship and shed new light on my grandmother as a campus leader. Although these articles provided important details of the conference, they failed to illuminate Benjamin’s character. Who was he and where did he go after Ann Arbor? I reached out to the Bentley Historical Library to see if there was more information about Benjamin. In response, I received a scan of his student file. From this, I discovered that Benjamin’s real name was Gin Behmin. The file listed his

An image emerged of Benjamin as a highly educated young man of religious conviction, who possessed a strong desire for a career in law and was passionate about improving China’s standing in the world. Alumni postcards in his file suggested that after a brief career teaching law at Peking University, he settled on a career in banking in Shanghai as an employee of the now defunct National Commercial Bank of China. The last update submitted by Benjamin in the file was from 1934.

I wondered if Benjamin, as a foreign-educated, religious banker, might have fled China when the Chinese Communist Party unified the country in 1949. Nonetheless, I could find no trace of him in places like Hong Kong, Taiwan, or the United States. To learn more, I was compelled to delve into Chinese language sources with the assistance of ChatGPT. I also traveled to Shanghai and Hangzhou in 2024 to trace Benjamin’s footsteps and unravel his story.

I also connected with several members of his extended family, and I hope that sometime soon I will connect with his surviving children, who may have stories or other artifacts from their father’s time in Ann Arbor.

I still have many questions about why my grandmother gravitated toward Benjamin and developed a friendship with him, but it is clear to me now that they both had similar, outgoing personalities, and shared a curiosity about the world beyond their own cities and countries. Perhaps they also found camaraderie as “outsiders” at the University of Michigan—Benjamin as one of a handful of Chinese exchange students and my grandmother as a first-generation college student from a poor family. I also believe that Benjamin and Estelle found a commonality in the plights of their ancestral countries, as both China and Poland found themselves menaced by belligerent neighbors.

Learning about my grandmother’s relationship with Benjamin in a time of global conflict also gives me hope that similar friendships will endure today as cross-cultural communication and understanding become even more important. And it will be archives like the Bentley Historical Library that help tell the complete story.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Gerald R. Ford’s presidency. His accomplishments on a national scale make it easy to forget he was also an exceptional U-M football player.

By jay winkler

AMONG ALL THE RETIRED NUMBERS in all of college athletics, Michigan football’s #48 is unique: it is the only one retired for a person who later became a U.S. president.

Gerald “Jerry” Ford began making a name for himself on the gridiron as a high school student in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Before his senior season in 1930, the Grand Rapids Press noted that Ford’s “work as a defensive fullback on occasions last year was extraordinary.” He was featured, smartly dressed, in an ad that touted “Popular Football Team Captains Wearing Young Men’s Clothes from Houseman and Jones.” (Apparently the NCAA was not yet enforcing rules about athlete endorsements.) When the Detroit Free Press editors selected him for its AllState team, they called him “the ideal center and all over the field on defense.”

When Ford came to Michigan in 1931, freshmen could not play varsity football. Nevertheless, The Michigan Daily kept a close eye on him in practice. The paper reported that Ford “showed ability in backing up the line in the Michigan system of defense” when he started for the freshman “Yearlings” in their annual contest against a team of students from the Physical Education department. After spring practice concluded, Ford was awarded the Chicago Alumni Trophy, given to the “freshman player who had shown the greatest development.”

Despite the first-year accolades, Ford spent his sophomore and junior seasons stuck on the bench behind All-American Chuck Bernard. Ford appeared on the field sporadically but competently as a backup, helping Michigan win the 1932 and 1933 National Championships.

Meanwhile, off the field he was a model student: he joined the Sphinx, the junior men’s honors society; he sat on club boards; and the Athletic Department was proud to report his good academic standing to the Daily Ford was poised to be a breakout football star his senior year. Though Michigan football experienced a significant performance downturn and limped to 1–7, Ford

was the team’s star. The Michigan Daily regularly featured his photo, with captions such as “Ford plays stellar game” and “Ford proves dependable.” Before his final game, the paper noted his toughness for starting a full season “despite enough injuries to keep several less hardy men confined to bed.” As a send-off, his teammates voted him 1934’s Most Valuable Player.

Ford played in the East-West Shrine allstar game on New Year’s Day in 1935. Both the Green Bay Packers and Detroit Lions offered him professional football contracts, but he turned them down, opting to become an assistant coach at Yale. His last game of organized football was a college All-Stars vs. Chicago Bears exhibition in August of 1935. While initially denied admission due to his football coaching duties, by 1938 he entered Yale Law School and was promoted to junior varsity head coach.

While Michigan did not retire Gerald Ford’s number until he was out of office, it wasn’t just a courtesy to the president: as materials at the Bentley show, Ford earned every tackle and took every hit.

Ford on the football field in 1934, the same year his teammates voted him Most Valuable Player.

Fifty years ago, the Edmund Fitzgerald freighter sank beneath the waves of Lake Superior. Ric Mixter’s research into the wreck is archived at the Bentley, ready to help the next generation of shipwreck enthusiasts.

By Lara Zielin

THE NOVEMBER GALE was whipping Lake Superior into a frenzy. The ship Arthur M. Anderson was sailing into waves as high as 30 feet, while 50-knot winds howled.

Arthur M. Anderson’s captain, Bernie Cooper, was in touch with a nearby vessel, whose captain had reported damage from the storm. The other captain reported that his ship’s radar was out, the sump pumps were running, but nothing appeared too amiss.

The Edmund Fitzgerald survived an ice storm on Lake Superior in this archived postcard.

“We’re holding our own,” the other captain radioed.

Cooper thought everything was fine. He never suspected

that a short time later, captain Ernest McSorley and his ship, the Edmund Fitzgerald, would be gone beneath the waves. The entire crew, 29 men total, would die on November 10, 1975, in a Great Lakes’ maritime disaster.

Shipwreck researcher and historian Ric Mixter has spent decades investigating what factors contributed to the Edmund Fitzgerald tragedy and wrote a book of his findings called Tattletale Sounds: The Edmund Fitzgerald Investigation (Airworthy Productions, 2022). Today, his in-depth research on the topic is archived at the Bentley Historical Library.

“One factor is that just about everyone misjudged the storm’s speed,” says Mixter, a former journalist who has appeared as a shipwreck expert on the History and Discovery channels. “That storm went across Lake Superior about an hour faster than anyone expected. Captain McSorley could have stopped at several places to shelter but he thought he could make it down to Whitefish Point (Michigan).”

McSorley also had a track record for pushing the ship to its limits. Nicknamed the Toledo Express, the Edmund Fitzgerald had been setting records for both speed and how much it could carry. “McSorley really believed that the ship was infallible,” Mixter

says. This, despite documentation that the ship had a loose keel and its hatch covers were compromised, even before it left Superior, Wisconsin, on its ill-fated route. “I think McSorley pushed that ship every year and it finally caught him,” says Mixter.

Mixter even got a closeup look at the damage to the ship when he dove the wreck in 1994. Underwater he could see firsthand the mangled hatch covers. The ship itself was in two pieces.

Back on dry land, Mixter unearthed documentary footage at the Bentley of the ship being constructed and interviewed the ship’s builders. He also interviewed ship captains on the lake the night the Edmund Fitzgerald sank, additional divers who explored the wreck, and many others. His work comprises decades of research that will now be available at the Bentley for anyone to explore.

“I’m so glad I had experts at the Bentley to guide me because it’s so easy to miss things, and now my own research can be there to help guide others,” Mixter says.

It’s likely his papers will grow as he continues to amass evidence and research about the Edmund Fitzgerald and other shipwrecks. “As I do more research and projects, I’ll definitely be adding to the collection,” he says.

Meet Thomas Hyry of the Houghton Library at Harvard University. He’s part of our new series about great archivists who trained at the Bentley and are doing important work in the field.

By Katie Vloet

Hi Tom, nice to meet you! Tell us about the work you do at Harvard.

I’m the associate university librarian for archives and special collections and the Florence Fearrington Librarian of Houghton Library at Harvard. In addition to Houghton Library, Harvard’s premiere home for rare books, manuscripts, and literary and performing archives, I oversee the Harvard University Archives, the Harvard Film Archive, the Fine Arts Library, and the Eda K. Loeb Music Library. My work involves a lot of strategy, management, budgets, fundraising, running teams, that sort of thing.

With so many management duties on your plate, I’m guessing you have less time in the archives.

It’s a terrible irony—you get drawn into archival work through your interest in the collections, but if your career progresses into leadership and administration, you engage with them less and less. But I have brilliant colleagues who work more directly with our collections and users—they are very talented and dedicated, and I’ve found that trusting them is a good approach.

What kind of training did you receive at the Bentley?

While a graduate student in the archives track of the School of

Information, I took a course then known as the Archives Practicum, based at the Bentley, and was assigned a collection to process. Archival work clicked in for me pretty quickly. I created a finding aid for Brian Williams [now an assistant director and archivist for university history at the Bentley], and he said, “You’ve really never done one of these before? You seem to think like an archivist.” Brian gave me a job and I worked at the Bentley for almost a year before beginning my professional career at Yale.

What stands out from your time at the Bentley?

Well, it’s coming up on 30 years, but one thing I remember is that I got to help pack up and accession some of the Jim Toy collection. Toy was a pioneer in the gay rights movement in Michigan, and his collection really demonstrated to me what a courageous activist he was, especially at the time. He seemed pretty heroic to me.

What are some of your favorite items at the Harvard archives?

It’s very hard to choose. We have one of only 48 surviving copies of the Gutenberg Bible, and one of only 23 that is complete. It’s in two volumes, and one of them is always on display. It was given to Harvard by the family of Harry Elkins Widener, who was a rare book collector. He and his father perished on the Titanic and his mother Eleanor funded the construction of a new library at Harvard as a memorial to him.

Were you interested in libraries even as a child in Ironwood, Michigan?

Ironwood, in the Upper Peninsula, is as far as you can get from Ann Arbor and still be in Michigan. It never occurred to me that I might become an archivist and librarian when I grew up, but I was a library rat in high school and college. Whenever I go back, I visit the library.

“I Know This

A

visiting researcher from the University of the Philippines identifies significant documents—and locations— in Bentley collections.

By Katie Vloet

EIMEE LAGRAMA WAS DIGGING through files last August when she came across a photo she’d never seen. It was a picture of a bullet-riddled library building on the campus of the University of the Philippines, photographed after the World War II Battle of Manila when the United States and the Philippines fought against Japan to liberate the capital city.

“I have pictures in our archives of the building from the outside, but never from the inside,” says Lagrama, head of the university archives division and deputy university librarian at the University of the Philippines, Diliman (UPD). “It was emotional to see it in the sense that I hadn’t known how damaged it was.”

She unearthed the photo not in her home country but at the Bentley Historical

Library. Lagrama visited for the month of August 2024 thanks to a Bentley fellowship, which allowed her to sift through more than 100 collections that contained material related to the Philippines.

Ricky Punzalan, director of the Museum Studies Program and associate professor of information at the U-M School of Information, is a friend of Lagrama from their time as students at UPD. Punzalan and Bentley Director Alexis A. Antracoli went to the Philippines in 2023 as part of a multi-year reparative project surrounding Philippine collections at U-M called ReConnect/ReCollect. There, they spoke with Lagrama about ways she could shed light on materials in the Bentley, which paved the way for her visit.

U-M and the University of the Philippines have a long history of collaboration, Lagrama points out—beginning when the United States took control of the Philippines from Spain after the Spanish-American War.

Among the collections she researched were several boxes of materials from the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, where she found the photo of the war-ravaged library building, which she has since shared with her own university’s archives.

“I didn’t know what to expect. But I found so many things [like] photos of my dad’s hometown, including a church that is still standing, and I couldn’t help but be excited. I said, ‘Alexis, I know this place! We used to play there,’” she recalls. She also texted colleagues back home, too excited to worry about the 12-hour time difference.

She looked through paperwork in the late Michigan Senator Carl Levin’s collection; papers and diaries of Frederick G. Behner, a Thomasite educator who traveled to the Philippines in the early 1900s; pictures of a faculty member swimming in a pond— some demure, some less so—as well as love letters to his girlfriend; and extensive documentation about Philippine plants from the University Herbarium collection.

With her visit, Lagrama became part of the long tradition of collaboration between the two universities—a history that is richer and more intertwined than she previously understood.

“It’s not just an exchange of people,” she says. “It’s an exchange of learning and ideas, too.”

Eimee Lagrima discovered images of the Philippines after the Battle of Manila.

Typhoid, dysentery, tuberculosis–in the early 1900s, they could all be spread by flies. That’s why one woman launched a crusade to rid the city of Cleveland of its flying pests.

By Kim Clarke

NOT EVERYONE CAN CLAIM to be a giant killer. But Jean Dawson could. And she did so with gusto.

A three-time Michigan alum, Dawson was bequeathed the splendid title of “America’s Most Famous Woman Fly

Fighter” for her early 20th-century assault on a winged pest that threatened young and old by transmitting diseases.

“Flies are now known to be the most deadly enemy of man,” Dawson proclaimed in 1912. “They kill more people than all the lions, tigers, and snakes, and even wars.”

As a U-M graduate student a decade earlier, Dawson was a founding member of the Women’s Research Club. The organization was in response to the 1901 creation of the U-M Research Club, whose male scientists refused to admit women. The discrimination infuriated and motivated Dawson and other women preparing for careers in science. “Jean Dawson was always the loudest and most outspoken,” said Ellen Bach, a fellow co-founder. The Bentley holds the papers of both research clubs.

Armed with her doctorate in zoology, Dawson carried out her crusade against flies in Cleveland, Ohio, first as a biology teacher and then as a city public health official.

Flies could transmit typhoid, dysentery, tuberculosis, and other lethal yet preventable diseases. It was a time when automobiles were becoming fashionable, yet horses—and their manure—still filled city streets and stables. Along with rotting garbage, the refuse was the perfect breeding ground for flies, which spread disease to human foods using their germy legs.

Dawson went after flies as a professor of civic biology at the Cleveland Normal Training School, along with the help of her students. Starting in 1911, she and her minions—all women—attacked

the insects on three fronts: liquidating the “winter fly” before it had the chance to breed in the spring (“one fly killed in April is equivalent to killing thousands in August”), trapping and snuffing out those pests that managed to surface in the warm months, and eliminating fetid organic matter.

Armed with a Michigan doctorate, Jean Dawson took on houseflies and the diseases they transmitted.

She recruited schoolchildren to be “junior sanitary police” and rewarded them for tiny corpses (10 cents per 100 flies). She recommended traps to capture and poison flies (4,000 dead critters equaled 1 pint). She distributed hundreds of thousands of fly swatters—provided by a local merchant—to carry out the slaughter. In 1915, she became chief of the city’s Bureau of Fly Prevention.

Most notably, she worked with city leaders and merchants to clean up the community and rid it of manure and garbage. Contractors hauled horse dung out of town, inspectors patrolled alleys behind restaurants and markets, and workers regularly collected trash. After five years of Dawson’s work, Cleveland saw a noticeable decrease in flies and disease.

Dawson pointed to the testimony of a businessman: “In past years flies rose like steam before you as you passed in front of the stalls in the market. Why, you could not tell the color of the meat for flies in those days.”

Cleveland, Dawson declared, was “practically the only flyless city in America.”

Dawson moved from Ohio to Florida to live on a 50-acre fruit ranch with her scientist husband, Clifton F. Hodge. As she wrapped up her fly fighting in Cleveland, the two collaborated to write a book about the power of “civic biology” to fight public health crises. In the Sunshine State, they studied oranges and other citrus. She died in 1948 at 75.

U-M’s Mandolin Club records tell the story how this unlikely instrument took the campus—and nation—by storm in the early 1900s and faded just as quickly.

By Kim Clarke

IMAGINE, IF YOU WILL, hundreds of University of Michigan alumni crowded into a theater for a night of live music. The opening number is, of course, “The Victors”—what better way to fire up a room? Leading the audience from the stage in full harmony are members of the Glee Club. And backing them up with instrumentation are another handful of young men playing not trombones, clarinets, or tubas but rather mandolins.

The scene was repeated many nights over many years at the turn of the 20th century as the Mandolin Club plucked and strummed its way around the country in tours that routinely sold out and left crowds wanting more.

The mandolin, in its many forms, was all the rage. When a group of young people known as the Figaro Spanish Students performed on bandurrias and guitars in New York City in 1880, it launched a mandolin craze that would continue for four decades in the United States.

The U-M Mandolin Club began in the 1890s with roots entwined with the Glee Club. Both groups were for male students. For a while, the College of Engineering had its own group, the Technic Mandolin Club. Women formed the Girls’ Mandolin Club in 1916.

The Mandolin Club regularly embarked on tours that took students to the West Coast, the Pacific Northwest, and the East. Tour programs, notes, and news clippings can be found at the Bentley.

Often playing before enthusiastic Michigan alums, the students wielded their mandolins to perform all manner of songs: selections from popular musicals, waltzes, ragtime, and marches. They played classical music, such as Franz von Suppé’s “Light Cavalry,” and robust marches like John Philip Sousa’s “Invincible Eagle.”

The U-M standard, “Varsity,” was a given; Earl V. Moore wrote the song in 1911 while a student and, as a graduate student, directed the Mandolin Club in 1916.