COLLECTIONS

Meet Helen Thompson Gaige, one of the first professional women herpetologists in the United States. Her one-of-a-kind legacy endures in the archive.

Meet Helen Thompson Gaige, one of the first professional women herpetologists in the United States. Her one-of-a-kind legacy endures in the archive.

SPRING 2023 A PUBLICATION OF THE

BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY

4 The Improbable Herpetologist

Frogs, salamanders, and lizards, oh my! Helen Thompson Gaige was a globetrotting herpetologist who identified and collected new reptile species and blazed a trail as a woman scientist. Her challenges and triumphs endure in her archived papers.

10 The Politician and the Traitor

Detroit Mayor Frank Murphy was a devout Catholic who found a political and spiritual ally in Father Charles Coughlin. That is, until the popular priest descended into fascism. Archived papers tell the story of political turmoil and a fractured friendship.

18

Beyond These Hallowed Halls

Oscar W. Baker Sr. was one of the first African American students accepted into the University of Michigan Law School. His academic career was distinguished, but it was when he left U-M that he made an even bigger impact working tirelessly for racial and social justice.

Burton Tower’s massive carillon bells (pictured here with mechanic Frank Mitchell) are played today using their original keyboard, all thanks to an unlikely ally. Story on p. 30.

EDITOR’S NOTES

1 Partnerships to Repair Harm and Shed Light

ABRIDGED

2 Select Bentley Bites

IN THE STACKS

24 Baseball’s Barrier Breaker

26 Last Call

28 Tragedy on the Ice

BENTLEY UNBOUND

30 The Carillon and the Egyptologist

31 Writing in Secret

SPRING 2023

contents

(ON THE COVER) MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY RECORDS, BOX 4; (THIS PAGE) U-M NEWS AND INFORMATION SERVICES PHOTOGRAPHS

Partnerships to Repair Harm and Shed Light

DURING MY TIME AS INTERIM DIRECTOR OF the Bentley, I’ve cultivated and encouraged strategic partnerships. The idea behind these collaborations is to enhance the understanding of both what the Bentley has and how the library can examine collections with fresh eyes, repair harmful historical descriptions, and construct new models for how to best engage colleagues across campus and beyond.

In the last issue of Collections magazine, you may have read about the ReConnect/ ReCollect project, which is an interdisciplinary, critical examination of the thousands of Philippine artifacts U-M has spread throughout its multiple campus locations—including the Bentley. One item in particular, a small painting that was misattributed, has now been correctly identified as the work of Fernando Amorsolo—an important Filipino painter who created an estimated 10,000 works over his lifetime, many depicting Filipino people, landscapes, and culture.

Now that this “unknown painting” has been correctly identified, it can shed light on Amorsolo’s career and deepen the understanding of the relationships

between Americans, artists, and the indigenous Filipino people of the Baguio area, where it was painted.

This is one small example of the Bentley’s efforts to repair inadequate, inaccurate, and even harmful archival descriptions and this remains ongoing, important work. Although the ReConnect/ ReCollect project officially comes to an end in September 2023, we will continue these reparative efforts with faculty partners, fellow U-M curators, community members, artists, and more.

The Bentley also recently partnered with Eric Hemenway, Director of Repatriation, Archives and Records for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, in discussions about the John P. Murphy photograph collection. This collection contains several hundred images of Michigan in the late nineteenth century, many of which depict American Indian subjects. Hemenway generously provided expert advice on how best to curate these unique images.

I’ve also encouraged internal collaboration at the Bentley, specifically Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion efforts across teams. One example is the library’s new Potentially

Harmful Language and Content Committee, which helps caution researchers about content that might be difficult or adverse. Recently, the committee developed a statement that is now on the website and acknowledges that “some collections reflect outdated, biased, offensive, and possibly violent views and opinions” and that the Bentley is “dedicated to revising and updating our descriptive language, and to describing archival materials in a manner that is respectful to the individuals and communities who create, use, and are represented in the collections we manage.”

This is only a portion of the statement, and I invite you to read the text in its entirety here: myumi.ch/EP6R7

Great partnerships can serve to expand access to collections and shed more light on the past, and I look forward to leading additional collaborations in the future. An archive is most valuable when it’s used— when its holdings are researched, studied, and, ideally, better understood—and this never happens in a bubble.

1 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU EDITOR’S NOTES

Nancy Bartlett Interim Director

Nancy Bartlett Interim Director, Bentley Historical Library

(Left) ReConnect/ ReCollect project participants examine the then-unknown Fernando Amorsolo painting, helping produce a correct identification. SCOTT SODERBERG

abridged

$3

The cost of dance lessons taught by Ethel McCormick in the Michigan League ballroom in 1932, according to The Michigan Daily.

3,000

Number of flower varieties inside Alumni Memorial Hall (now the U-M Museum of Art) during the 1913 chrysanthemum show.

SPORTS WORLD HISTORY GEOLOGY OF THE GREAT LAKES

MICHIGAN IN THE PHILIPPINES

POLITICAL SCIENCE RESEARCH DESIGN

A sampling of undergraduate classes that recently came to the Bentley to research collections.

AND THE BAND PLAYED ON

In mid-November 1896, more than 20 musicians met for the first time in the University of Michigan’s Harris Hall. Their first big performance was the very next year, and the group would eventually evolve into the University of Michigan Marching Band. There were no official uniforms during the band’s earliest years; standard attire would debut in 1923, featuring an officer’s cap with no plume, a black jacket with shoulder-to-shoulder braids and tassels, and a short cape. Today’s uniforms are designed by Stanbury Uniforms and fit more than 400 band members.

2 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

ABRIDGED

“I and my end of the boat were submerged in the water. Our escort played the Hero and rescued me. I was drenched and had to walk back to town dripping all the way and a swish, swish at every step.”

Lulu Channer recounting a spill into the Huron River in her 1924 Alumnae Survey. (She did not care, she added, because she had “a good time.”)

ALEXIS ANTRACOLI NAMED NEW BENTLEY DIRECTOR

Exciting news! The Regents of the University of Michigan have approved Alexis Antracoli as the Bentley’s next director.

“The Bentley has a long history of excellence and leadership in the archival profession, and I am honored by the opportunity to work in collaboration with a diverse group of colleagues at the Bentley and across campus in order to best lead this stellar library forward,” Antracoli said.

Her appointment will begin on May 1, 2023, and she will work with archivists and other professionals overseeing the Bentley’s vast collections, both physical and digital.

One Million Students

An 1894 mock issue of The Michigan Daily imagined U-M in the year 2000, and “reported” that one million students would be in attendance and balloon rides would be offered over campus, among many other imagined advances.

PRESIDENT ONO TOURS THE STACKS (AND MORE!)

U-M President Santa J. Ono recently visited the Bentley Historical Library to look at some historical papers, books, and even a football helmet. In the Conservation Lab, he saw samples of old wallpaper preserved from the historic president’s house on campus.

BAMEWAWAGEZHIKAQUAY

The Ojibwe name of Jane Johnston Schoolcraft, one of the earliest Native American literary writers, who lived in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. Her name means “The Sound the Stars Make Rushing Through the Sky,” which is also the title of a volume of poetry she wrote, now held at the Bentley.

POP QUIZ

Do you know where in Michigan this is?

Answer:

If you guessed Ann Arbor, you’re right! This was painted by Roxina Norris in 1895, and the Bentley holds eight of her watercolors in the Roxina Norris watercolor collection.

Some of the locations visited in this issue of Collections magazine.

3 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU abridged COLLECTIONS ABRIDGED

PANAMA CAIRO, EGYPT LADY FRANKLIN BAY, GREENLAND BAY CITY, MICHIGAN ROYAL OAK, MICHIGAN

HELEN THOMPSON GAIGE’S passion for frogs, salamanders, lizards and more was unusual for a woman at the turn of the century. She defied gender stereotypes by becoming an expert in zoology and launching herself into globetrotting adventures to collect and study specimens. Her scientific legacy endures in the archive—and beyond.

By Madeleine Bradford

By Madeleine Bradford

TheImprobable Herpetologist

GROWING UP IN THE MIDDLE OF MICHIGAN’S “THUMB” IN THE 1890s, HELEN THOMPSON WAS BORN INTO A CHANGING WORLD. RAILROADS UNFURLED ACROSS THE COUNTRY, THE USE OF ELECTRIC LIGHTS WAS SLOWLY SPREADING, AND MORE AND MORE WOMEN WERE PURSUING HIGHER EDUCATION.

Helen’s father was able to encourage her studies. A believer in the importance of education, Charles E. Thompson, widely known as “Charley,” had attended Goldsmith, Bryant & Stratton, a small business college

in Detroit. He was well known for trying his hand at a wide range of local jobs in the town of Bad Axe, from bookkeeper to probate judge. Helen watched her father throw himself into new pursuits with determination, again and again.

She decided to follow her father’s footsteps: she would get a degree. Two, in fact.

She applied to the University of Michigan and was accepted in 1906.

By 1907, Helen had discovered the U-M Museum of Zoology, and within it, the reptiles and amphibians collection. A detailed history of U-M, called the Encyclopedic Survey, notes that Helen was seen as “a student of natural history.” After earning her Bachelor of Arts degree in 1909, a teacher’s certificate, and her Master of Arts in 1910, she applied for a position at the Museum of Zoology.

It was an unusual choice in the early 20th century. Of the 20 Master of Science degrees awarded by the University of Michigan in 1910, only one was awarded to a woman.

“We know very little about the early women of science,” Margaret Rossiter writes in “Women Scientists in America before 1920,” published in American Scientist magazine. What is verifiable is that “they had fewer job opportunities and lower status, were more often unemployed, and less often considered eminent by their fellow scientists.”

The academic journal Ichthyology & Herpetology notes that Helen was “among the first professional women herpetologists in the United States.”

THE SEA SERPENT AND THE EXPLORER

Helen obtained her position at the U-M Museum of Zoology “by enthusiasm and competence,” according to the Encyclopedic Survey.

Her fieldwork and publications were regularly reported on in The Michigan Daily. The paper even asked her about the Loch Ness Monster.

"These stories about sea monsters appear quite frequently, but we have yet to see one,” she said. “People are inclined to exaggerate the size of snakes that they may see. They are so frightened at seeing a snake of any sort that its size increases in their imagination.”

The water would be far too cold for a sea snake in Scotland, she insisted. (She then gave a short lecture on how sea snakes swim.)

Helen’s passion for learning drove her outdoors, starting with a 1912 expedition to Nevada, to make some discoveries for herself.

Soon enough, she was happily swooping a long-handled dip-net into muddy streams, searching for frogs.

In 1913, Helen married Frederick Gaige, a fellow museum professional. However, marriage didn’t mean leaving her job, as it did for many women at the time. According to several sources, she and her husband enjoyed their work and collaborations, which included widespread research travels. The couple went to the Davis Mountains of Texas in 1916, and the Olympic Mountains of Washington in 1919.

“Both she and Professor Gaige are real people, tireless workers, out every day, not a miss, paying no regard to weather, more and more enthusiastic over their catches; their whole aim was to add something more to their collection. And they were unreservedly liked by all who knew them,” U-M alumnus J.B. Smedley said in the 1923 Saginaw News

6 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU G

(PREVIOUS

COLLECTION

SPREAD) MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY RECORDS; (THIS PAGE) FREDERICK M. AND HELEN T. GAIGE PHOTOGRAPH

(Previous spread) Helen Thompson Gaige’s tireless herpetology research resulted in her naming and identifying several new frog and salamander species.

(This page) Helen, holding ivy in this undated photo, conducted scientific fieldwork at home and abroad.

That same year, in 1923, they also made their way to the Chiriqui Mountains of Panama.

THE MISFIRE AND THE MIRACLE

Panama was hot, tangled with forests, and the Gaiges pushed gamely through them.

The noise of the shot that took Helen’s finger was muffled by undergrowth. Frederick Gaige stumbled hurriedly to the scene, and found his wife, staring in shock at her hand. Both Helen and Frederick habitually carried guns when exploring.

Helen’s had misfired.

Helen bore the pain silently at first: “Not a cry nor a whimper from her,” her husband wrote. “She showed unbelievable courage every minute.”

A doctor gave her morphine, but her fever quickly skyrocketed. “She was white and her eyes got such a terribly tired look, every time I had to leave the room she started singing a soft little song to herself,” Frederick remembered. “It was the most heartbreaking thing I ever saw.”

Telegraphs were urgently sent, but there weren’t many medical supplies readily available in the middle of the wilderness, and the chances of anything reaching them in time were slim.

It began to look like she might die there.

Then, there was what Frederick Gaige called the “miracle.”

A buzzing overhead.

It was a U.S. plane, dropping a tetanus vaccine nearby, “wrapped with tire tape and weighted.” It saved Helen’s life.

She lost her finger, but she survived the trip. Her injury certainly didn’t stop her from continuing her life’s work. It didn’t even stop her from traveling. She would go on expeditions in Florida and Colorado only two years later, in 1925.

Still, her husband’s notes about the incident show the kind of underestimation she sometimes dealt with, even at home.

In several instances, in a tone of sympathy, he called her a “child.”

8 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

(Top to bottom)

Allophryne ruthveni, a frog genus named by Helen in honor of colleague Alexander Ruthven.

Helen at home in Ann Arbor.

The salamander genus Rhyacotriton, first identified by Helen.

SPECIMENS AND SCIENTIFIC CAMOUFLAGE

Helen’s colleague Alexander Ruthven described Helen as someone who applied herself to her job with gusto, uplifted colleagues, and loved sharing what she knew.

“Her careful work and sound judgment are well known,” he wrote. “With a total lack of professional jealousy, she has not only contributed directly to knowledge of the subject but has had a prominent part in improving techniques, in promoting the work of others, and in developing an esprit de corps among investigators.”

The Museum of Zoology newsletter, The Ark, joked in 1922 that, when handling new creatures being added to the collections, “Mrs. Gaige does the brain work and writing, and Dr. Ruthven ties the label string about the little animal. Cooperation is everything.”

Ruthven would become Director of Museums that very year, and then the president of the University of Michigan in 1929.

Identifying new specimens as part of her work, Helen often chose names for them that echoed the names of her colleagues. For example, Gastrotheca williamsoni is a tree frog she likely named after Edward Williamson, a curator at the Museum of Zoology.

She also named an entire Genus of small golden frogs from the Amazon rainforest of Guyana: she christened them “Allophryne.”

Translated from Greek, the title means “Other Toad.” These frogs are colloquially known as “Ruthven’s Frogs,” because she named the first one she found Allophryne ruthveni A photograph of an Allophryne ruthveni can be found in the Museum of Zoology’s Specimen Type digital image collection for reptiles and amphibians. It’s a little frog, freckled with spots, like a leaf in late autumn.

Helen’s focus on supporting others—even naming species after them—may have been a survival strategy in a field where women’s contributions were often overlooked. Bolstering the work of her male colleagues may have been one way to keep them accepting, and supportive, of her presence. She wouldn’t have been the first to use other people’s assumptions about gender to carve a niche for her work.

In her book The Madame Curie Complex: The Hidden History of Women in Science, historian Julie Des Jardins describes how an early woman chemist, Ellen Richards, actually “sewed buttons and swept floors to gain men’s acceptance in the lab.” Leaning into the supportive role women were expected to take, Jardins argues, can be seen as a kind of “camouflage” that women used to take on a scientific role.

Margaret Rossiter’s research also shows that women who worked in scientific fields could be uncredited partners in scientific work. For example, she notes a significant bump in the careers of zoologist men who married zoologist women, while the women’s careers sometimes stalled or stopped. She hypothesizes that many of those women were likely contributing to their

husband’s careers, uncredited.

There is no archival proof that this is the case for Helen, but it may be worth noting here that her life does follow this pattern: her highest role at the University of Michigan was as a curator. Her husband eventually became the director of the Museum of Zoology.

RECOGNITION AND IMPACT

MAs an early woman in science, Helen had a brilliant herpetological career. She was named an editor of the journal Ichthyology & Herpetology (formerly Copeia). In 1930, she became Ichthyology & Herpetology’s editor-inchief and stayed in that position until 1949. She was the first woman to hold either position—on top of having been the first woman published in that journal to begin with. She would publish 40 papers over the course of her life.

Helen was also the first person to identify the salamander genus Rhyacotriton: tiny, speckled lizards, no longer than a finger, with bellies as yellow as sunflower pollen.

Her hard work paid off with broader recognition: in 1946, she was named the “permanent honorary president” of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (ASIH).

As one of the first women to become a professional herpetologist in the United States, Helen helped break down the gender boundaries in her field, paving the way for others to follow. She also advocated for fieldwork in scientific education, believing strongly in the importance of hands-on experience.

Her impact can still be seen in the Museum of Zoology specimen database: “Helen T. Gaige” or “H. T. Gaige” is labeled as the collector of 2,040 reptiles and amphibians. That database still helps scientists with their research today.

Helen’s legacy lives on: ASIH also established an award in her name, funding herpetological research and exploration.

To learn more about Helen Thompson Gaige, see The Herpetology of Michigan, cowritten by Alexander Ruthven, Helen Gaige, and Crystal Thompson, available both in the Bentley’s Reading Room and in the HathiTrust digital library. The Bentley also has files on Helen Gaige’s life in the Museum of Zoology records and the News and Information Faculty and Staff collection. More images of Helen can be seen in the Frederick M. and Helen T. Gaige photograph collection.

9 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS

(TOP

“MRS. GAIGE DOES THE BRAIN WORK AND WRITING, AND DR. RUTHVEN TIES THE LABEL STRING ABOUT THE LITTLE ANIMAL. COOPERATION IS EVERYTHING.”

TO BOTTOM) MATTHIJS KUIJPERS/ALAMY, FREDERICK M. AND HELEN T. GAIGE PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION, WIRESTOCK, INC./ALAMY

&

& WASFATHERCHARLESE.COUGHLIN POPULARACATHOLICPRIESTAND RADIOHOSTWHOEVENCOUNTEDPOLITICIANS,AND PRESIDENTFRANKLINMANYD.ROOSEVELT,AMONGHIS FRIENDS.CLOSESTINWASHISCIRCLEOFINFLUENCE MICHIGANGOVERNOR FRANKMURPHY.

BUTBYTHESTARTOFWORLDWAR II,MURPHYWOULDCUTTIESWITHTHEPRIEST,WHOWOULD FINDHIMSELFINTHETHROES OFATREASONINVESTIGATION.ARCHIVED PAPERSATTHEBENTLEYHELPTELLTHESTORYOFWHAT HAPPENED— ANDWHY.

ByLaraZielin

ByLaraZielin

THE QUIET MARCH NIGHT IN ROYAL OAK, MICHIGAN, WAS SHATTERED AT 3:00 A.M. WITH A TERRIBLE EXPLOSION. A BOMB HAD BEEN LOWERED INTO THE BASEMENT OF A PRIVATE HOME ON FAIRLAWN ROAD, AND THE BLAST RIPPED THROUGH A STEAM PIPE AND SHATTERED WINDOWS. CANNED GOODS WERE RUPTURED AND SPLATTERED.

WITHIN MINUTES, THE POLICE ARRIVED. GUARDS WERE PLACED AROUND THE HOUSE. THEN, NONE OTHER THAN DETROIT’S MAYOR, FRANK MURPHY, ARRIVED ON THE SCENE.

MURPHY WAS THERE TO COMFORT AND HELP THE BLAST’S INTENDED VICTIM: FATHER CHARLES E. COUGHLIN, A CATHOLIC PRIEST AND A PERSONAL FRIEND OF MURPHY.

It was 1933, at the height of the Great Depression. Coughlin had a popular radio show that reached millions of listeners, giving them hope amidst terrible economic circumstances.

Together, Coughlin and Murphy had worked hard on behalf of those hit hardest by the Depression by setting up food distribution centers and lodging houses. As a team, they stumped tirelessly for Roosevelt, helping him win the White House in 1932. Murphy even helped Coughlin write some of his speeches during this time.

It makes sense, then, that Coughlin would call Murphy for aid after his home had been bombed.

But the bomb itself was a sign that Coughlin’s role was changing, going beyond that of a typical Catholic priest to one that was far more political—not to mention divisive.

Coughlin told The New York Times he assumed the bomb in his house was “an act of intimidation” in response to his highly critical broadcasts against Detroit bankers and a Depression-era banking plan.

Murphy had already tried to get Coughlin to tone down his anti-banking rhetoric, but had failed. Now, here was Murphy again, this time in the dead of night, trying once again to help Coughlin out of a scrape.

For the next decade, this pattern would continue. As Coughlin grew more political, Murphy would do his best to rein in his friend and keep him from alienating allies and the listeners of his successful radio program.

But to no avail.

Coughlin’s rhetoric would become increasingly antisemitic and isolationist as the U.S. tipped toward full involvement in World War II. Eventually, Coughlin would come dangerously close to being indicted on sedition charges.

As papers at the Bentley reveal, Frank Murphy tried to pull Coughlin from the edge time and again. Eventually, Murphy would have to give up the fight and admit that his one-time friend had turned U.S. traitor. And maybe even worse.

THE INFLUENCER AND THE OVAL OFFICE

In the early- to mid-1930s, nearly 30 million people tuned into Father Coughlin’s weekly radio broadcasts on Sunday, roughly a quarter of the U.S. population at the time. More than 30,000 people flocked to his church in Royal Oak on Sundays, called the Shrine of

12 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

(PREVIOUS

MURPHY

SPREAD LEFT TO RIGHT) FRANK

PAPERS, CHARLES E. COUGHLIN PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION

the Little Flower. One survey at the time stated Coughlin was the most important person in the United States behind the president.

There’s no question Coughlin used his radio program to persuade the American people to vote for Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 1932 election. Coughlin’s brand of social justice and reform fit well with New Deal policies, and he painted Roosevelt as an American savior.

Coughlin and Roosevelt were reportedly close after Roosevelt had secured the White House. Coughlin told one interviewer he was with the president every couple weeks. And of course Coughlin made sure to put in a good word for his friend Frank Murphy, eventually taking credit for Murphy’s appointment as governor general to the Philippines, then a U.S. territory, in 1933.

But however close Coughlin thought he was to Roosevelt, it apparently wasn’t close enough. Coughlin had specific ideas and policies he wanted Roosevelt to implement, including substituting silver for gold for the money standard. When the president ignored him, Coughlin seethed.

In an archived letter in the Bentley’s Frank Murphy collection from January 1934, Coughlin complained about how his affection for the president went unreciprocated: “I have had no contact either directly or indirectly with the president since you left [for the Philippines]. Sometimes I am of the opinion that while I certainly rebuilt the confidence of the people in him, a confidence which had been greatly impaired, I sometimes wonder whether or not he favors my being with him.”

Gradually, Coughlin’s speeches became increasingly critical of President Roosevelt, questioning his judgment and policies. In 1934, William Walker, a friend of Murphy, wrote to Murphy in the Philippines to note that Coughlin was “getting in Dutch,” meaning he was getting in trouble or disfavor with his critical rhetoric and was “on the toboggan,” or on the decline.

At the same time, others were writing to Murphy asking if he might use his

friendship with the still-popular radio star to their benefit. John D. Dingell Sr. (father of John D. Dingell Jr., who served Michigan for 59 years in the Democratic party) was up for reelection in 1934 and asked Murphy to please “write to Father Coughlin on my behalf.” A positive word from Coughlin could mean big results at the polls, after all.

Generally, Murphy’s letters to Coughlin convey concern, care, and genuine friendship. Murphy wrote to Coughlin in 1934 after getting news that the priest was ill and wished him a speedy recovery. Letters from Murphy’s family referenced Coughlin spending time at the family home. Coughlin sent Murphy birthday cards.

But all that changed when Coughlin started endorsing a candidate to challenge Roosevelt in the 1936 election.

13 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS

(Top) Coughlin speaks to a crowd in Minnesota in 1936, encouraging them to vote against Roosevelt in the upcoming election.

(Left) Frank Murphy addresses the Michigan legislature on January 7, 1937.

(THIS PAGE) FRANK MURPHY PAPERS, CHARLES E. COUGHLIN PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION

MURPHY WALKS A FINE LINE

By 1935, Roosevelt had appointed Murphy high commissioner to the Philippines—a position that reported directly to Roosevelt and would help the Philippines transition to independence. Murphy, while doing well in the Philippines, also had his eyes on Michigan and on a bid for governor.

An endorsement from Coughlin would go a long way to boost his candidacy.

The problem was that Roosevelt was putting pressure on Murphy to get Coughlin to tone down his criticism of the New Deal and of Roosevelt writ large.

“President Roosevelt not only compromised with the money changers and conciliated with monopolistic industry,” Coughlin said in a 1935 sermon about the failures of the New Deal, “but he did not refrain from holding out the olive branch to those whose policies are crimsoned with the theories of sovietism and international socialism.”

Murphy was working to handle the relationship diplomatically, apparently with some success according to James Farley, a member of Roosevelt’s cabinet. Farley wrote in his memoir that Roosevelt thought Murphy was doing “a splendid job in handling Coughlin.”

It couldn’t have been easy, especially as Coughlin launched the National Union for Social Justice in early 1936. It was an anti-capitalism and anti-big business organization—as well as deeply antisemitic and anti-New Deal.

(Top) Coughlin and Murphy meet at Detroit’s Book Cadillac Hotel in better times, circa 1934.

(Bottom) From right to left, Frank Murphy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and G. Hall Roosevelt meet just ahead of the 1932 presidential election.

(Opposite) Coughlin’s antisemitic Social Justice newsletter sympathized with Nazis and blamed Jewish people for manipulating the economy and spreading

The National Union for Social Justice teamed up with Francis Townsend, an activist, and Gerald L.K. Smith, an organizer and white supremacist, to form the Union Party. The express goal of the Union Party was to unseat Roosevelt in the 1936 presidential election. They put forward their own candidate, William Lemke, hoping Lemke could draw enough votes away from Roosevelt to allow Alf Landon, the Republican candidate, to win.

The plan was a disaster.

Roosevelt won the 1936 presidential election in a landslide. That same November, Murphy was elected governor of Michigan.

His popularity was on the rise, while Coughlin’s was on the decline. A 1939 Gallup survey estimated that out of the 15 million listeners who tuned in to Coughlin each month, fully one third disapproved of what he said. And that’s just the folks who listened. Among those who didn’t tune in, 75 percent disapproved of him.

A BRIDGE TOO FAR

Murphy served Michigan for two years as governor, then was appointed U.S. Attorney General in 1939. By this time, war was raging across Europe and Americans were debating whether to take up arms and fight.

Coughlin had begun producing Social Justice, a weekly newspaper that was deeply antisemitic and pro-Germany. Coughlin praised Hitler and claimed that Germany was an “innocent victim” of a war declared by the Jewish people. Should the United States enter the war, it would be feeding into a Jewish and Communist plot to “liquidate Americanism.”

Critics began to call Coughlin’s church The Shrine of the Little Führer.

In 1940, Murphy was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court and was quickly confirmed by the Senate. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the U.S. entered World War II, Murphy joined the reserves and served while the court was in recess.

While Murphy fought, Coughlin continued to write Social Justice and speak over the airwaves. Members of Roosevelt’s administration worried Coughlin

(TOP AND BOTTOM) FRANK MURPHY PAPERS

SERIAL

COLLECTIONS CHARLES E. COUGHLIN, SOCIAL JUSTICE

CHARLES E. COUGHLIN, SOCIAL JUSTICE SERIAL

CHARLES E. COUGHLIN, SOCIAL JUSTICE SERIAL

and moved to a home in Birmingham, Michigan. In a 1968 interview with The New York Times he said he didn’t regret any of his actions and “couldn’t honestly take back much of what I said and did in the old days when people still listened to me.”

He died on October 27, 1979, at age 88.

Murphy had passed away several decades prior, in 1949, from a blood clot in his coronary artery. His death at age 59 was a shock; just the day before, the hospital that was performing tests on him had permitted him to go for a car ride with friends. He was not considered to be in critical condition.

Last rites were performed for Murphy by Henry J. Kenowski, a Catholic chaplain.

Father Coughlin was nowhere nearby.

(Opposite) By 1940, Coughlin was being pressured to end his radio career and Social Justice was considered enemy propaganda in violation of the Espionage Act.

(Top) Frank Murphy was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court as the U.S. entered World War II. He enlisted in the reserves and served while the Supreme Court was in recess.

Sources for this story include:

Bentley collections including the Frank Murphy papers and the Charles E. Coughlin Sermons and Sunday Evening Radio Addresses. Sidney Fine: The Frank Murphy Series (University of Michigan Press, 1975). James P. Shenton: “The Coughlin Movement and the New Deal,” Political Science Quarterly 73, no. 3 (1958). “Father Coughlin’s Residence Bombed,” The New York Times, March 31, 1933. Radioactive: The Father Coughlin Story, Andrew Lapin, PBS podcast. Rachel Maddow Presents: Ultra, MSNBC podcast.

17 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

COLLECTIONS

FRANK MURPHY PAPERS

By Margaret Leary

By Margaret Leary

BEYOND THESE HALLOWED HALLS

In 1899, Oscar W. Baker Sr. was accepted into the University of Michigan Law School, becoming the 100th African American student to attend U-M. After graduation, Baker would make remarkable contributions and achievements working for racial and social justice. The Bentley’s new African American Student Project helps fill in some of the information about this exceptional alum.

IN THE LATE 1800S,

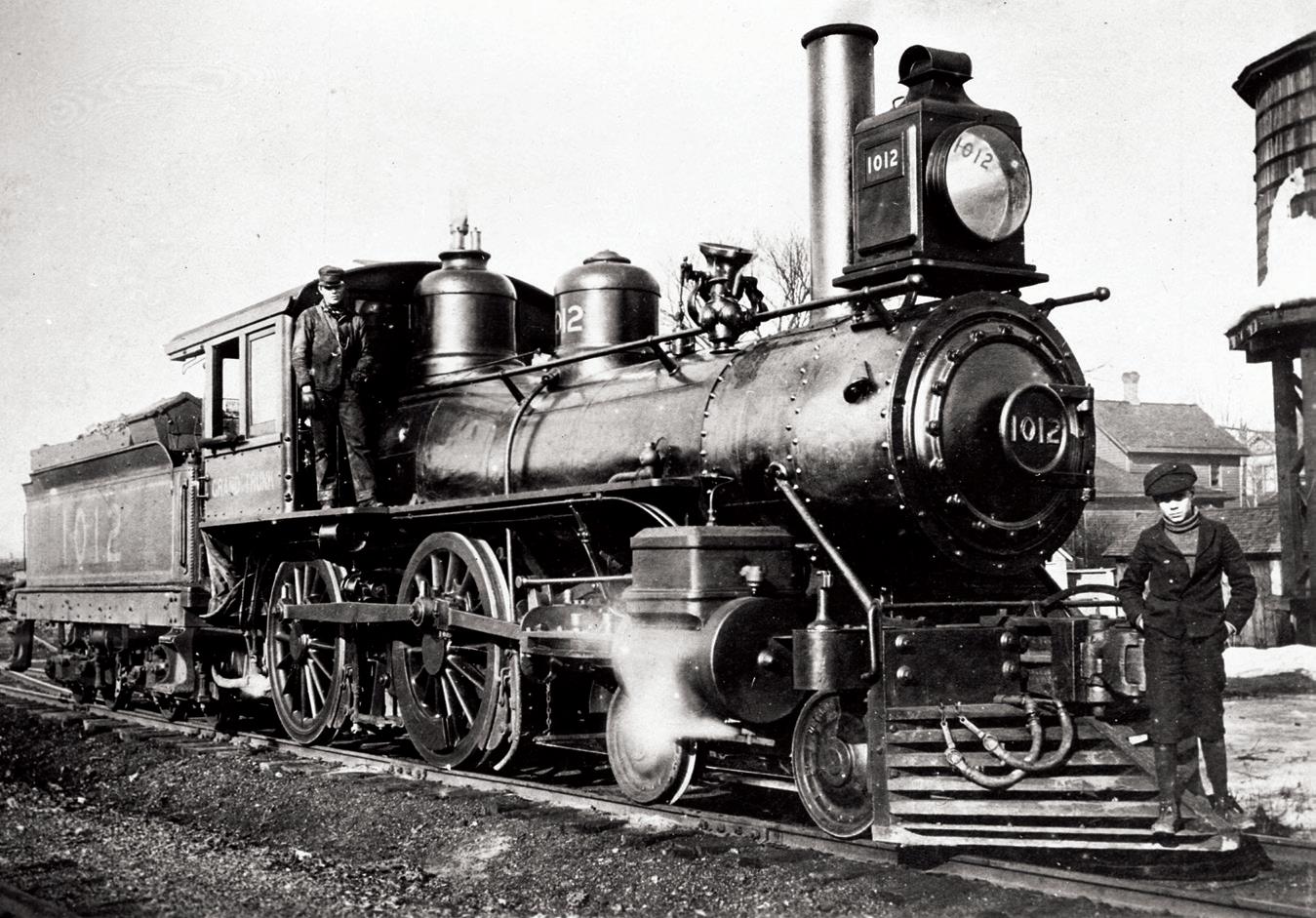

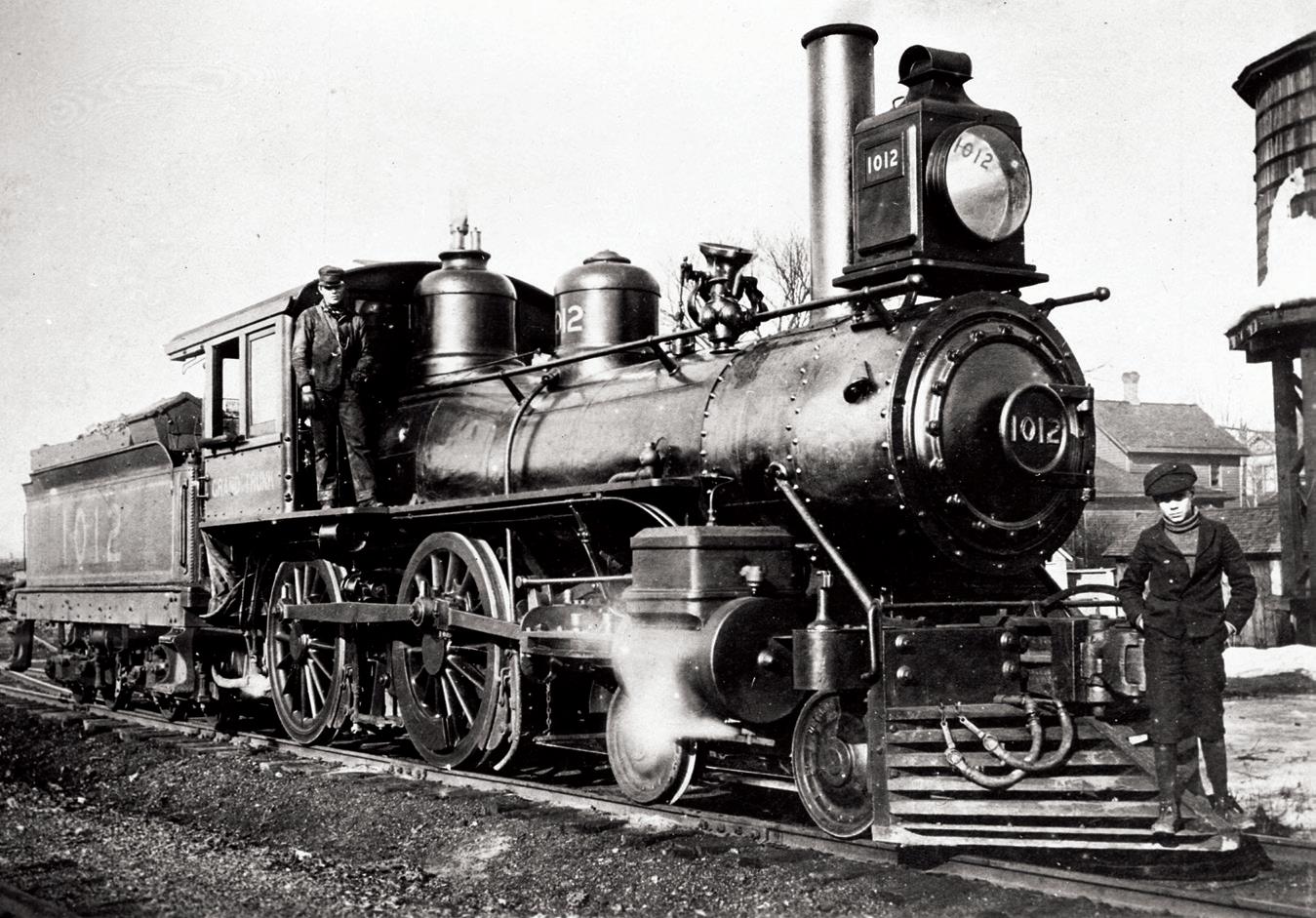

THE TOWN OF BAY CITY, MICHIGAN, WAS THRIVING. Its location, where the Saginaw River flows into the Saginaw Bay of Lake Huron, had proven ideal for lumbering, shipbuilding, coal mining, salt production, and the sugar-beet industry. Railroads augmented the rivers, connecting Bay City by land to the rest of the country.

In 1885, six-year-old Oscar W. Baker was chasing friends along the Pere Marquette train tracks when, at the crossing of Jefferson and 11th Streets, he stumbled and fell. He was struck by an oncoming train and nearly killed. The train cut off part of his leg, which soon had to be removed to the hip. His father, James H. Baker—one of the first African Americans in Bay City, who had been a barber, owned a local restaurant, and had run for office in town—sued the railroad. He won a then-enormous $5,000 judgment.

Young Oscar was a crucial witness in the trial, examined and cross-examined by the lawyers. One of the lawyers predicted his future: “He was and is prevented from doing any work and from attending

school, and is, and always will be, hindered and disabled from earning his own living . . . .”

Oscar proved this prediction completely wrong. He would become a sought-after lawyer, fighting racial prejudice and becoming the first president of the Bay City NAACP. At one point in his career, Oscar helped Black women such as Marjorie Franklin achieve fair housing at the University of Michigan, representing Franklin when she fought to live in Couzens Hall.

The Bentley’s new African American Student Project database has helped fill in more details about Oscar’s life, revealing his remarkable contributions and achievements working for racial and social justice.

EARLY CAREER

Oscar finished high school at age 19, then attended the Bay City Business School to learn typing and shorthand. In 1899, he was accepted into the University of Michigan Law School, becoming the 100th African American to attend U-M.

Money was tight, however, because Oscar’s father had poorly invested the $5,000 judgment funds from the railroad accident. To earn tuition money, Oscar was an office assistant for Lt. Governor Orrin W. Robinson, using the typing and stenographic skills he had learned in business school.

Oscar later became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, an African American fraternity, probably joining as an alum since the U-M chapter didn’t form until 1906. Student directories show him living at 217 N. First Street, about a mile west of campus, in the segregated area of Ann Arbor, where many African American homes and churches were located. He graduated in 1902 and had his law license. But how to set up an office, with no resources?

A white lawyer, Lee Joslyn, offered Oscar the extra desk in his Bay City office and said Oscar could take any case that walked in when Joslyn was absent. The invitation made the law firm the first integrated law firm in the state. Oscar made his “maiden plea” in police court in August 1902 and, although he lost, his arguments were so eloquent that the West Bay Times newspaper called him “one of the coming young attorneys of this city.”

An early case that Oscar brought was an attempt to recover the $5,000 his father had lost. His father had acted as the “next friend” of his minor son, and Oscar learned in law school that the railroad may have erred in making the payment without bond, which was not required at the time. Oscar ultimately lost that case but may have won a bigger victory: As a result of the litigation, insurance companies and railroads began to require a guardian, who would be responsible to the minor and had to post a bond, to be appointed for minors involved in civil suits.

FIGHTING FOR RACIAL JUSTICE

At age 35, Oscar became the President of the Michigan Freedmen’s Progress Commission, an organization that produced the Michigan Manual of Freedmen’s Progress. The Manual chronicled in pictures, stories, and documents the progress of African Americans in Michigan 50 years after the abolition of slavery.

Commissioned by the State of Michigan and paid for by the Michigan legislature, the Manual became a comprehensive catalog of accomplishments by Michigan African Americans. It listed doctors, lawyers, clergy, dentists, nurses, musicians, and other professions; highlighted volunteer service in the military; chronicled Michigan politicians; and more. It showed hundreds of

(Previous spread)

Interior of the U-M Library at the turn of the century, when Oscar Baker would have studied here as the first African American accepted into the U-M Law School.

(Opposite page)

An 1841 map of Michigan showing a rapidly expanding system of canals, trains, and roads, overlaid by an image of a train engine in Bay City, Michigan, in 1904.

(This page) The 1902 Michiganensian yearbook featured images of the Law School’s graduating class, including Oscar Baker, number 12.

21 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS

(PREVIOUS SPREAD) UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PHOTOGRAPHS VERTICAL FILE; (OPPOSITE PAGE, TOP TO BOTTOM) HS1348, CLAUDE THOMAS STONER COLLECTION (THIS PAGE) 1902 MICHIGANENSIAN

photographs of individuals, buildings, houses, as well as lists of patents and inventions, plus facts about the relative health and mortality of African Americans and whites in Michigan.

Another of the Manual’s goals was to provide evidence of press bias against African Americans in four daily Detroit papers. The analysis showed that of 232 documented articles, only 36 were “commendatory,” while 139 were about “criminal” African Americans.

The Manual also supported the Michigan delegation to the Half Century Anniversary of Negro Freedman event in Chicago, from August 22 to September 15, 1915. Popularly known as the “Lincoln Jubilee and Fifty Years of Freedom” celebration, it attracted thousands of attendees, culminating in a crowd of 22,000 to hear Chicago Mayor William Thompson at the closing.

The delegation’s timing was significant: Reconstruction had long ended, Jim Crow was flourishing, and the KKK would soon be established in Michigan. That Oscar was chosen to help produce the Manual and attend the delegation illustrates the deep trust his community placed in him, and it elevated his profile across the state and nationally.

(This page) As part of work on the Michigan Manual of Freedmen’s Progress, Oscar Baker led a delegation to the “Lincoln Jubilee” celebration in Chicago in 1915, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. (Opposite page) Baker working in his Bay City law office, undated.

Clarence Darrow in representing Ossian Sweet (in 1925) and later Henry Sweet (in 1926), when the men were accused of murder after defending the home Ossian had purchased in a white Detroit neighborhood. Shortly after the Sweets occupied the house, an angry white mob threatened from the front yard. The police who were present did nothing, and a gun fired from an upper story of the house killed one white man and wounded another. The trials were sensational and highly publicized. Both Sweet men were found not guilty, in part due to the recommendations for good legal counsel, which Oscar helped provide.

Oscar also protested prejudice against other minorities. When an ad published by a Michigan resort asked for gentiles only, Oscar wrote a letter to the editor of a local Bay City paper arguing the resort’s ad violated the Civil Rights statute of Michigan.

When a local branch of the NAACP was organized in Bay City in 1919, Oscar was its president. He maintained contact with the national NAACP and advised them about lawyers who could join

(TOP TO BOTTOM) MICHIGAN MANUAL OF FREEDMEN’S PROGRESS , WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, MICHIGAN MANUAL OF FREEDMEN’S PROGRESS

(TOP TO BOTTOM) MICHIGAN MANUAL OF FREEDMEN’S PROGRESS , WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, MICHIGAN MANUAL OF FREEDMEN’S PROGRESS

LOCAL POLI TICS

Oscar continued to support having a branch of the NAACP in Bay City, despite his opinion that “there is little need for such an organization. Prejudice is at a minimum and personally I have very little difficulty in getting by in the courts . . . . There is little prejudice in the theatres, cafes, etc. and the people live in harmony one with the other, so far as the races are concerned.”

Then, in 1951, as a member of the Bay County Bar Association, he voted to expel anyone who “professes membership in the Communist party.” The local Bay City paper ran the headline: “Bar Will Expel Reds; Action is Believed First in Michigan.” The next year, Baker continued to serve on a special advisory committee of the American Bar Association to study the strategy and tactics of Communists. It was ostensibly part of the association’s work to combat Communist infiltration of lawyers’ ranks.

Oscar made headlines again in the fall of 1952 by switching political parties. The local paper reported that Baker, a “pioneer attorney and leading Republican figure in the State for more than 50 years,” had repudiated Republican gubernatorial candidate Fred Alger and would support the re-election of Democratic Governor G. Mennen Williams. His reason? “Williams has been one of the fairest and most liberal governors for the minorities and the common man in his memory.”

Oscar continued to build his career in Bay County and more widely. He was the first African American to be elected head of the Bay County Bar Association, he was vice-president of the Bay County Recreation Commission, and he was a member of the Board of Control of the Bay City Amateur Baseball Federation. He and his family often enjoyed a month at Idlewild, a resort in northwest Michigan. It was one of the few resorts where African Americans could join and own property.

Two of his nine children, Oscar Jr. and James Weldon, earned law degrees from the University of Michigan, and Oscar Jr. continued the family practice. Generations of Bakers have continued to attend the University, including fourth-generation twins David and Nathaniel Cade, who earned J.D.s in 1996, and their cousin, David Baker Lewis, who earned his J.D. in 1971.

Today, the University of Michigan Law School offers the Oscar Baker Sr. scholarship to commemorate his legacy and to support African Americans attending the Law School.

Sources for this story include:

The African American Student Project website (aasp.bentley.umich.edu). Bay City Times Historical and Current, 1889–Present. Professor Edward J. Littlejohn’s archives, Walter Reuther Library at Wayne State University, as well as Littlejohn’s books and articles about African American lawyers. Black Studies Center and Historical Newspapers (ProQuest).

23 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

MICHIGAN MANUAL OF FREEDMEN’S PROGRESS

Baseball’s Barrier Breaker

ON MAY 1, 1884, MOSES FLEETWOOD WALKER took to the baseball field as a catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings. It was his inaugural game with the team, which had just joined Major League Baseball. They were playing against the Louisville Eclipse in Kentucky.

Robinson would play for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

All while being jeered, taunted, and harassed—or worse.

By Dr. Rashid Faisal

The Blue Stockings lost that day, 5–1, in part because, as one paper wrote, Walker made “three terrible throws.” The Toledo Blade wrote about the game with more nuance and cited the “gravitating circumstances” that may have rattled Walker and caused his “poor playing.”

Walker had just broken baseball’s color barrier, more than 60 years before Jackie

“Walker is one of the most reliable men in the club, but his poor playing in a city where the color line is closely drawn as it is in Louisville should not be counted against him,” wrote the Toledo Blade.

Walker’s experiences on the field and off would propel him to become an editor, author, and political advocate for Black rights as segregation blanketed the United States.

The

24 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU IN THE STACKS

Before Jackie Robinson, there was Moses Fleetwood Walker, a U-M law graduate who would use the racism and discrimination he faced in baseball to fuel a career as an editor, author, and political advocate for Black rights.

1882 U-M baseball team with Moses Fleetwood Walker, front row, third from right.

ACADEMICS AND BASEBALL

Walker was born on October 7, 1857, in Mount Pleasant, Ohio, to a Black American physician, Dr. Moses W. Walker, and a white mother, Caroline O’Harra. In 1860, the Walker family moved to Steubenville, Ohio, an abolitionist hub that had served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Walker and his brother, Weldy, attended Steubenville High School after the community passed legislation in favor of racial integration. Walker started his athletic career in 1879 as the first Black baseball player at Oberlin College. The integrated institution established intercollegiate baseball in 1881, and Walker developed a stellar reputation as a star catcher and leadoff hitter.

In 1882, Walker enrolled in the University of Michigan Law School. He was recruited by members of U-M’s baseball team and earned a starting position as catcher on the 1882 varsity team.

Walker was the first Black American to play baseball at U-M and the first to play varsity sports at U-M. Walker helped lead the 1882 U-M baseball team to a 10–3 record and the championship of the newly formed Western Baseball League, the predecessor to the Big Ten. Walker batted .308 that season and elicited rave reviews from the Chronicle, U-M’s student newspaper: “Walker, as a catcher, did some of the finest work behind the bat that has ever been witnessed in Ann Arbor.”

In 1884, Walker left the University of Michigan to sign a semi-pro contract with the Toledo Blue Stockings of the Northwestern League. Walker would soon learn that racism awaited him at every stop during his baseball career.

“WHITE BASEBALL”

Weldy Walker joined his brother on the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884, becoming the second Black American in Major League Baseball. Weldy made his debut as an outfielder on July 15, 1884. He appeared in five games with a .222 batting average.

Both Weldy and Moses Walker experienced open racism. They were taunted and subjected to racial slurs by fans and members of the opposing team. They were spit on and threatened with lynching.

Even some of Walker’s teammates subjected him to race hate. Blue Stockings

pitcher Tony Mulane admitted that Walker “was the best catcher I ever worked with. But I disliked a Negro, and whenever I had to pitch to him, I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals.”

Ahead of a game in Richmond, Virginia, the manager of the Blue Stockings, Charlie Morton, received a letter from a racist mob threatening to lynch Walker if he were to take the field. The letter read, in part: “We could mention the names of 75 determined men who have sworn to mob Walker if he comes to the ground in a suit.”

THE OVERT RACISM AND DEATH THREATS FROM FANS, OPPOSING TEAMS, EVEN HIS OWN TEAMMATES TOOK A TOLL ON BOTH HIS PHYSICAL AND EMOTIONAL HEALTH. WALKER OFFICIALLY RETIRED FROM BASEBALL IN 1891 AND WAS THE LAST BLACK AMERICAN TO PLAY MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL UNTIL JACKIE ROBINSON IN 1947.

Four days later, Walker was released from the Blue Stockings.

Weldy would go on to join the Pittsburgh Keystones in the National Colored Base Ball League, although the league would last less than a year.

Walker continued to play for integrated minor leagues teams, including joining the Syracuse Stars in 1888. There, he faced the hostilities of racist fans and lasted one season before the Stars released him.

The overt racism and death threats from fans, opposing teams, even his own teammates took a toll on both his physical and emotional health. Walker officially retired from baseball in 1891 and was the last Black American to play Major League Baseball until Jackie Robinson in 1947.

SELF-DEFENSE AND EQUALITY

After his retirement in the spring of 1891, Walker was attacked by a racist mob in

Syracuse, New York. One of Walker’s assailants, a white ex-convict named Patrick Murray, hit him in the head with a rock. In retaliation, Walker stabbed Murray in the groin with a pocketknife. Murray died from his injuries a brief time later.

Walker was arrested and tried for second-degree murder. The all-white jury acquitted Walker, though his legal troubles weren’t yet over. In July 1895, while working as a mail clerk in his hometown of Steubenville, Ohio, he was charged and found guilty of mail robbery. He was sentenced to one year in prison.

After his release from prison, Walker was no longer an advocate of racial integration. He and Weldy both became advocates of Black nationalism. Walker believed racial integration between the races was impossible due to white America’s unwillingness to accept and treat Black Americans as equals.

Walker and Weldy abandoned the Republican Party and co-founded the Negro Protective Party. The party’s platform called for “an immediate recognition of our rights as citizens such as have been repeatedly pledged and as often violated.” The Walker brothers published The Negro Protector as its official party newsletter.

The brothers jointly edited The Equator, a newspaper that advocated for racial separation and for Black Americans to return to Africa to free themselves from segregation, discrimination, and mob violence. In 1908, Walker published a 47-page book titled Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America, in which he advocated racial separation and Black Americans’ emigration to Africa. He argued against the possibility of Black and white Americans coexisting on fair, just, and equal terms.

With Weldy, Walker also opened the Opera House in Cadiz. Ohio, which hosted live performances and shows. Walker also patented several inventions related to film and “nickelodeons.”

After spending his retirement years as an entrepreneur, newspaper editor, civil rights activist, and agent for the Back-to-Africa Movement, Walker died on May 11, 1924, in Cleveland, Ohio—four years after the Negro National League was established. His remains were brought back to Steubenville, where he is buried in Union Cemetery.

25 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU COLLECTIONS IN THE STACKS

U-M ATHLETICS TEAM PHOTOS, 1882

Last Call

Prohibition drove alcohol underground at U-M beginning in 1920. But apparently not underground enough. A police raid in 1931 brought national attention to drinking on campus. Archived records at the Bentley show how U-M administrators responded—and what the fallout was like.

By Andrew Rutledge

By Andrew Rutledge

AT 12 A.M. ON JANUARY 17, 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution went into effect. From that moment on, “Prohibition” made it illegal for any American to “manufacture, sell, barter, transport, import, export, deliver, furnish, or possess any intoxicating liquor.”

Traditionally, the University of Michigan had taken a neutral stance in the national debate over alcohol. But Prohibition

changed the University’s stance, both legally and as part of its broader in loco parentis philosophy, where school officials closely supervised students’ behavior outside the classroom.

Nevertheless, alcohol was still widely, if quietly, available. Due to its proximity to Canada, Detroit was a major center for alcohol smuggling, and it was easy for Michiganders to purchase drinks from there.

The records of the University Discipline Committee, responsible for determining punishment for students breaking University rules, are full of incidents involving alcohol. In 1929, for example, a trio of students was arrested for running a bootlegging operation from their dormitory. All three were suspended.

But the most egregious alcohol-related incident on U-M’s campus kicked off on the night of Tuesday, February 10, 1931.

That evening, the Ann Arbor police arrested a pair of bootleggers. Under questioning, they confessed that they had delivered alcohol to five fraternity houses earlier that night. The fraternities’ members had purchased the booze in

preparation for the annual J-Hop junior dance that weekend. Search warrants were swiftly issued, authorizing the police to search the fraternities.

The police struck in the early hours of the morning, ransacking the houses from top to bottom and arresting every one of the 79 students they found. The results:

■ Sigma Alpha Epsilon—four quarts and one pint of whiskey

■ Phi Delta Theta—four quarts and nine pints of whiskey

■ Delta Kappa Epsilon—four quarts of whiskey and half a case of beer

■ Kappa Sigma—fourteen quarts of whiskey, four quarts of gin, and three quarts of wine

■ Theta Delta Chi—nine quarts and four pints of whiskey, and one quart of gin.

The police had also brought a reporter along on the raids. The next morning, accounts of the raids appeared in newspapers from coast to coast. “Fraternity Houses Raided at Michigan” read The New York Times. In Los Angeles, Californians woke to the headline: “Raids Net Seventy

26 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU IN THE STACKS

MICHIGAN UNION RECORDS

Students.” Papers in Chicago, Boston, Washington, D.C., and Naples, Florida, as well as a host of smaller towns across the Midwest, also carried the story. It even made the news in Honolulu.

Even more embarrassingly, the police had provided a list of those arrested and several papers printed the names. The list included some of the most popular and influential students on campus, such as James Simrall, captain of the football team; Morton Bell, president of the student council; Carl Forsythe, night editor of The Michigan Daily; and Louis Colombo Jr., “son of a prominent Detroit lawyer.”

When his breakfast was interrupted by the news the next morning, Dean of Students

Joseph Bursley was furious. Both at the students for breaking the law and at the bad press for the University. And while the students had been released from jail, they’d all been ordered to appear in court that Friday.

Bursley knew a trial would only cause a deeper scandal for the University, so he and other U-M officials hurriedly met with the city prosecutor. They convinced him not to press charges, promising that the University would punish the malefactors. That afternoon, Bursley met with the Discipline Committee to decide how to do exactly that.

Due to the fraternity members’ “conduct detrimental to the best interests of the University and the serious injury to the University’s reputation,” the Discipline Committee determined that the fraternities would be suspended until September 1931 and placed on social probation for more than a year. Furthermore, the residents of the five fraternities were ordered to leave their houses by February 20. They were banned from returning to the fraternities until the fall term. However, the students themselves would not be suspended

Instantly, 182 students were made homeless in the middle of winter, scrambling around town for new lodgings. But it was not just fraternity brothers who were affected. Thirty-seven more students who worked as waiters and dish washers in the five houses also lost their lodgings, as well as their jobs in the midst of the Great Depression. At least two of them were African Americans: James Slade and Raymond Hayes, who lived and worked at the Kappa Sigma house. Neither returned to Michigan in the fall.

Letters poured into Bursley’s office from alumni and parents. He carefully archived them, and they reveal polarized opinions on both the crime and the punishment. Many denounced the closing of the

“FRATERNITY HOUSES RAIDED AT MICHIGAN”

READ THE NEW YORK TIMES.

(Opposite page) Members of Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity drinking alcohol.

(This page, left to right) Michigan Daily coverage of the fallout from the alcohol raid on U-M fraternities; a letter from Dean of Students Bursley to the Phi Delta Theta fraternity president announcing the fraternity's closure.

doing what nine out of ten of the rest of us do.” Others praised the decision for assuring parents that “there is one place they can send their children with some peace of mind regarding the moral atmosphere.”

Bursley responded to many of these letters, primarily those from prominent alumni, countering some of the sensationalism from the newspapers and seeking to explain the University’s punishment. The state legislature threatened to investigate alcohol on the campus, but the investigation never materialized, and the story soon faded from the news. The five fraternity houses eventually reopened in September 1932, and fraternity alumni pledged to ensure an end to liquor violations.

IN THE STACKS

COLLECTIONS

THE MICHIGAN DAILY , FEBRUARY 17, 1931, STUDENT DISCIPLINARY FILES

Tragedy on the Ice

By Andrew Rutledge

TUCKED INTO THE ALUMNI FILE of Edward Israel is a hand-written copy of an article about the 1881 graduate. It describes Israel as “a man of unusual character who, had he not been cut off at the early age of 25, would undoubtedly have left a decided impress on the world.”

The article appeared in a strange place—the American Meteorological Journal—and was written by Israel’s mentor, Mark Walrod Harrington, third director of the University’s Detroit Observatory. It wasn’t exactly commonplace for faculty to write articles in academic journals about former students, let alone students who weren’t scholars in that field. So why did Harrington pick up his pen and write so eloquently about Israel?

The answer may be, in part, guilt.

THE ARCTIC ASTRONOMER

In early 1881, Harrington was asked to nominate a student to serve as the astronomer for an expedition to the Arctic called the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition. His mind went immediately to his prize pupil: Edward Israel.

Born to Jewish parents who had come to Kalamazoo, Michigan, from Germany, Israel had entered U-M in 1877 and excelled at astronomy. Harrington wrote later that he approached Israel “with some hesitation” about the Arctic expedition since “[Israel’s] circumstances in life were so easy, he could pursue any line of study he might select, [but] on consulting him, the only motive which restrained him was a knowledge of the pain his acceptance would cause his [widowed] mother.”

Eventually, Israel’s mother gave her blessing, and Israel accepted the nomination. The expedition’s departure date forced Israel to leave Michigan before his final exams. The Board of Regents made a special dispensation to grant him his degree in absentia, something normally forbidden by University rules.

The Lady Franklin Bay Expedition had its origins in the first ever International Polar Year, which sought for the first time to create a coordinated approach for exploring the Arctic. Led by Lieutenant Adolphus Greely, the expedition’s goal was to establish a research station at Lady Franklin Bay on Ellesmere Island west of Greenland. The team planned to spend two years there collecting tidal, meteorological, astronomical, and magnetic data, as well as exploring the region for future expeditions to the North Pole.

Israel, Greely, and 23 other men left for the Arctic in July 1881, stopping in Greenland only long enough to hire a pair of Inuit sled drivers and a doctor. By August, they had reached their destination and the 25 men began building the longhouse that

would be their new home. They dubbed it Fort Conger, after expedition sponsor Senator Omar Conger of Michigan, and would spend the next two years there—farther north than any other humans in the world.

During the following months, Israel played a key role in collecting the expedition’s scientific data, while other members of the party traveled north, coming closer to the North Pole than any explorers had before. But despite these scientific successes, all was not well. Unbeknownst to Greely or his men, the summer of 1881 had been extraordinarily warm, allowing them to sail through open water to Fort Conger. That was not to be repeated.

By the summer of 1882, the men were expecting their first supply ship, but it was blocked by ice hundreds of miles to the south. Eventually, it was forced to turn back. A second attempt in 1883 ended with the relief vessel crushed by ice. Unaware of any of this, but knowing that his men were in danger of starving, Greely ordered his team into boats on August 9, 1882. Their goal was Cape Sabine 250 miles to the south, where the relief expeditions had been ordered to leave their supplies if they were unable to reach Greely.

After a nightmarish 51 days at sea, during which Israel’s astronomical skills proved vital for navigation, the group reached Cape Sabine. To their horror they found only a fraction of the supplies they had expected; there were only 40 days’ worth of rations, which they would have to make last until the following summer.

WARMLY LOVED BY ALL THE MEN

On January 18, 1884, the first member of the expedition succumbed to scurvy and malnutrition. He would not be the last. Over the following months, men died one by one, trying to survive on tiny shrimp from the bay along with candlewax, boots, bird droppings, and anything else remotely edible.

When a faculty member recommends his prize pupil for a daring expedition in Greenland, disaster strikes on multiple fronts.

One man was caught stealing food from the others and was shot on Greely’s orders. In an effort to stay warm, the survivors shared sleeping bags. Israel paired with Greely, who described him “as a great com fort and consolation to me, during the long weary winter . . . He was warmly loved by all the men.”

Edward Israel died “very easily and after losing consciousness” on May 27, 1884.

Twenty-six days later, rescue finally arrived. By then, there were only seven survivors, one of whom died soon after. Greely and the others returned to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to a hero’s welcome. But worse was yet to come.

Soon, rumors of cannibalism arose among the rescuers who had seen the corpses at Cape Sabine. An autopsy on the body of Frederick Kislingbury, second in command of the expedition, found flesh had been cut from his bones. The survivors all stridently denied any knowledge of cannibalism, with some suggesting that those fishing may have used corpse meat for shrimp bait.

Edward Israel’s body was not among those reportedly mutilated, but his mother refused to allow an autopsy. When his remains arrived in Kalamazoo, nearly the entire city greeted it. The funeral was held that same day. His mother would later donate 50 arctic plants he had collected to the University’s collections.

As for Israel’s mentor, Mark Harrington, he too met a tragic fate. After leaving U-M to head the U.S. Weather Bureau in 1891, he briefly became the president of the University of Washington. One night in 1899, he told his wife he was going out to dinner and disappeared. For the next decade there was no sign of him, until his son found him in an asylum in New Jersey in 1908. Sadly, Harrington did not recognize either his son or even his own name. He never recovered, spending the remainder of his life in the asylum before passing away in 1926.

(Background) Ice towering in Lady Franklin Bay, 1882.

(Top left) One of the expedition’s accomplishments was sending three of its members farther north than any human had previously traveled.

(Top right) The meteorological observation shed at Fort Conger.

(Middle) Edward Israel, front row, third from right, among other expedition members.

(Bottom) Only six out of 25 men survived and were rescued on June 22, 1884. Edward Israel was not among them.

(TOP TO BOTTOM) LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

(TOP TO BOTTOM) LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The Carillon and the Egyptologist

The carillon bells in the Burton Memorial Tower on U-M’s campus are played on their original keyboard, all thanks to an unlikely savior: a U-M Egyptologist.

By Madeleine Bradford

EARLY IN HIS CAREER AS A U-M PROFESSOR OF DENTISTRY, Dr. James E. Harris loved the music of the Burton Tower bells on Central Campus.

He remembered that music, even as his U-M work took him across the world, to the Cairo Museum in Egypt. There, in a joint 1967 project between U-M and Alexandria University, Harris examined the X-rayed teeth of mummified Egyptian royalty and used dental records to gain medical insights about them—all without having to unwrap the bodies.

Harris developed an expertise in Egyptology, which soon became his career.

Harris is listed as part of the U-M team that, in 1976, identified King Tut’s grandmother, Queen Tiye, using X-rays and hair analysis. Previously known only as an “Elder Lady,” Queen Tiye’s mummy was reconnected to her name, and moved to the Cairo Museum.

Meanwhile, the years were taking their toll on the bell tower, and the building needed renovations and repairs. The older bells were replaced in 1974, and the carillon keyboard was almost scrapped. It was removed to a warehouse of the Verdin Company, a carillon-making business where, by chance, Harris discovered it.

As a staunch supporter of the University of Michigan’s carillon music, he purchased the keyboard and held onto it for decades.

Then, serendipity struck.

In 2011, new renovations on Burton Tower began, with plans to reinstall the two highest octaves of old bells. Assistant Professor Steven Ball, a carillon music expert, had saved the original bells from destruction, and set about tracking down the keyboard, too.

He discovered that it was owned by Harris, who leapt at the chance to get it back where it belonged. What could be better than playing the original bells on their own keyboard? Harris donated the keyboard back to the University of Michigan, along with funding to restore it to its original state.

Today, U-M students can take classes to learn to play the carillon keyboard, which is a complex, physically demanding mix of pushing wooden levers and striking hammers. The public is welcome to attend 30-minute recitals at the top of the tower, which are performed at noon every weekday that classes are in session. The concerts are followed by a visitor Q&A session.

More about the Burton Memorial Tower can be found in the Bentley’s Building and Grounds Department records, and more about the Baird Carillon can be found in the Bentley’s School of Music, Theatre, and Dance records. Additional details about Dr. James Harris can be found in his faculty file, located in the News and Information Faculty and Staff Files collection.

Thanks to Egyptologist James Harris, the Burton Tower bells can be played on their original keyboard, as demonstrated here by carillonneur Percival Price.

BENTLEY UNBOUND

U-M NEWS AND INFORMATION SERVICES PHOTOGRAPHS

Writing in Secret

The Whimsies was an anonymously published literary magazine that became massively popular on U-M’s campus in the early 1920s. But who was behind it?

By Madeleine Bradford

THE STUDENT LITERARY MAGAZINE

The Whimsies was inspired, at first, by indignation.

“Professions, athletics, and the social side of life,” got the bulk of attention and encouragement at U-M, leaving literature and the arts to suffer, according to a 1921 article in The Michigan Daily by Stella Brunt.

Being “frankly dissatisfied” with U-M’s lack of artistic encouragement, a small group of students started a new literary magazine in secret. By writing and assembling it themselves, they could distribute it anonymously.

The first two issues of The Whimsies were made on hand-cranked duplicating machines that churned out mimeographed copies. These imperfect pages, peppered

with white space where ink should be, were clipped together, then “surreptitiously distributed” from Ann Arbor mailbox 147. Ink-smudged and triumphant, the authors went home.

The publication was well received. “Box 147 has a real idea,” wrote “L.M.W.” in The Michigan Daily, praising the mystery publisher and using its mailbox number in place of a name. But who, exactly, was “he?” Rumors swirled. One theory was that The Whimsies was being published by a member of the faculty. Encouraging letters began arriving, and writing submissions started coming in, but the publishers’ identities remained hidden—for a time.

The first 45 copies of inaugural issue had been mimeographed by hand but, by the third issue, the publishers were distributing 1,000 copies and had even found a printer: local bookstore owner George Wahr.

Then, on the front page of the third issue, the identity of the mastermind

BEING “FRANKLY DISSATISFIED” WITH U-M’S LACK OF ARTISTIC ENCOURAGEMENT, A SMALL GROUP OF STUDENTS STARTED A NEW LITERARY MAGAZINE IN SECRET.

behind The Whimsies was revealed. “He proved to be five girls!” wrote Stella Brunt.

Stella should know; she was one of the five. The other contributors were Yuki Osawa, Doris Gracey, Helen Master, and Hope Stoddard.

Opinion pieces in The Michigan Daily had all speculated that the author was a “he.” None of them seemed to consider that the publisher was a woman—or multiple women.

The Whimsies quickly pivoted, vowing to have a more even distribution of men and women in charge of the literary magazine in the future, to avoid accusations of unfairness.

Soon, they also found a mentor: the poet Robert Frost.

Teaching in Ann Arbor for the 1921–1922 academic year, Frost became a guest critic for The Whimsies, offering them advice. In return, they “respectfully and affectionately” dedicated the first issue of Volume 2 to him.

The Whimsies was later folded into another student publication, The Inlander, which lasted until 1930. Its founders’ belief that “there was among the students an urge for artistic expression as well as love for art itself” has proven true. Today, student literary publications on campus include Xylem Magazine and the Fortnight Literary Press.

You can find copies of The Whimsies in the Bentley’s Inlander publications.

31 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

THE INLANDER SERIAL

MAKE AN APPOINTMENT: myumi.ch/z1jDR

PREPARE FOR YOUR VISIT: myumi.ch/dkpyx

IF YOU HAVE QUESTIONS OR NEED ADDITIONAL ASSISTANCE, PLEASE CONTACT US: BENTLEY.REF@UMICH.EDU

32 BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

Bentley welcomes new donors whose materials can help build a better archive. More than 11,200 donors have entrusted us with their unique collections. FIND OUT IF WHAT YOU HAVE IS RIGHT FOR THE ARCHIVE. CONTACT US

U-M MATERIALS: Aprille McKay 734-936-1346 aprille@umich.edu FOR STATE OF MICHIGAN MATERIALS: Michelle McClellan 734-763-2165 mmcclel@umich.edu

The

FOR

THE

BENTLEY HISTORICAL LIBRARY IS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC BY APPOINTMENT. This means anyone is welcome in the reading room.

OPEN

WE’RE

ACCESS MATTERS

YOUR STORY BELONGS HERE

Explore online collections: BENTLEY.UMICH.EDU

COLLECTIONS, the magazine of the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, is published twice each year.

Nancy Bartlett

Interim Director

Lara Zielin

Editorial Director

Patricia Claydon, Ballistic Creative Art Direction/Design

Copyright ©2023 Regents of the University of Michigan

ARTICLES MAY BE REPRINTED BY OBTAINING PERMISSION FROM: Editor, Bentley Historical Library 1150 Beal Avenue

Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2113

PLEASE DIRECT EMAIL CORRESPONDENCE TO: laram@umich.edu 734-936-1342

Regents of the University of Michigan

Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods

Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc

Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor

Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor

Sarah Hubbard, Okemos

Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms

Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor

Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor Santa J. Ono, ex officio

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office for Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-6471388, institutional.equity@umich.edu. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.

Land Acknowledgment Statement

The Bentley Historical Library acknowledges that coerced cessions of land by the Anishnaabeg and Wyandot made the University of Michigan possible, and we seek to reaffirm the ancestral and contemporary ties of these peoples to the lands where the University now stands.

H. Miller.

Meet Frederick

Can you help?

supporting the Bentley’s Public Outreach Fund, you can help uncover more names and stories.

USE THE ENCLOSED ENVELOPE OR GIVE ONLINE TODAY. bentley.umich.edu/giving 734-764-3482 SUPPORT STORIES. ELEVATE VOICES. GIVE TODAY.

Thanks to recent crowdsourcing efforts, the Bentley has learned his name and identified him in recently donated photographs. Miller earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan in 1911 and was the third president of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity. But the two women who are with him are still unidentified.

By

PLEASE

Their Names Matter

ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48109-2113

Where Michigan’s History Lives

Every day, people use the Bentley Historical Library to explore history. With more than 70,000 linear feet of letters, photographs, books, and more, the Library is a treasure trove of primary source material from the State of Michigan and the University of Michigan. We welcome you to uncover Michigan’s history here.

The Bentley Historical Library is open to the public by appointment only.

REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT ONLINE

myumi.ch/35py6

EXPLORE COLLECTIONS AND FINDING AIDS ONLINE

bentley.umich.edu

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL facebook.com/bentleyhistoricallibrary

@umichbentley

@umichbentley

MAKE A GIFT

bentley.umich.edu/giving

734-764-3482

RUMOR HAS IT

Gossip swirled around a popular University of Michigan literary publication distributed anonymously in the early 1920s. Who was behind it? Readership skyrocketed, and the campus magazine was soon printing a thousand copies each issue. Then, this cover appeared and listed the editors: five women! Read about the start of the literary magazine The Whimsies, and the women who published it, on p. 31.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

1150 BEAL AVENUE

ABOUT

THE BENTLEY

Meet Helen Thompson Gaige, one of the first professional women herpetologists in the United States. Her one-of-a-kind legacy endures in the archive.

Meet Helen Thompson Gaige, one of the first professional women herpetologists in the United States. Her one-of-a-kind legacy endures in the archive.

By Madeleine Bradford

By Madeleine Bradford

ByLaraZielin

ByLaraZielin

CHARLES E. COUGHLIN, SOCIAL JUSTICE SERIAL

CHARLES E. COUGHLIN, SOCIAL JUSTICE SERIAL

By Margaret Leary

By Margaret Leary

(TOP TO BOTTOM) MICHIGAN MANUAL OF FREEDMEN’S PROGRESS , WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, MICHIGAN MANUAL OF FREEDMEN’S PROGRESS

(TOP TO BOTTOM) MICHIGAN MANUAL OF FREEDMEN’S PROGRESS , WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, MICHIGAN MANUAL OF FREEDMEN’S PROGRESS

By Andrew Rutledge

By Andrew Rutledge

(TOP TO BOTTOM) LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

(TOP TO BOTTOM) LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS