Collective Tenure: a community-driven counter strategy for housing in Chilean campamentos.

A case study from Latin America

P. MSc in Urban Design

Collective Tenure: a community-driven counter strategy for housing in Chilean campamentos.

P. MSc in Urban Design

This thesis investigates the potential of collective tenure as a counterstrategy to the neoliberal housing policies that have dominated Chile since the military dictatorship. It focuses on how organized communities in Chilean campamentos can challenge the commodifcation of housing by fostering self-management and collective organization. Inspired by international case studies from Latin America, including Uruguay, Puerto Rico, Bolivia, Chile and Brazil, the thesis demonstrates the benefts of alternative housing tenure models that prioritize social value over market-driven individual property ownership.

Through a qualitative case study methodology, the research examines fve self-managed housing projects and explores how collective tenure contributes to housing security, community agency, and urban transformation. The fndings highlight the need for legal reforms to incorporate surface rights and collective ownership structures in Chile, where market-oriented policies have marginalized vulnerable communities. By framing the analysis within Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the right to the city, the thesis argues that housing security, achieved through collective tenure, is foundational for reclaiming urban spaces for the people.

Diese Arbeit untersucht das Potenzial kollektiver Eigentumsformen als Gegenstrategie zu den neoliberalen Wohnungspolitiken, die Chile seit der Militärdiktatur prägen. Der Fokus liegt darauf, wie organisierte Gemeinschaften in chilenischen campamentos die Kommodifizierung von Wohnraum durch Selbstverwaltung und kollektive Organisation herausfordern können. Inspiriert von internationalen Fallstudien aus Lateinamerika, darunter Uruguay, Puerto Rico, Bolivien, Chile und Brasilien, zeigt die Arbeit die Vorteile alternativer Wohnformen auf, die den sozialen Wert über marktorientiertes individuelles Eigentum stellen.

Durch eine qualitative Fallstudienmethode untersucht die Studie fünf selbstverwaltete Wohnprojekte und erforscht, wie kollektives Eigentum zur Wohnsicherheit, zur Selbstbestimmung der Gemeinschaft und zur urbanen Transformation beiträgt. Die Ergebnisse weisen darauf hin, dass rechtliche Anpassungen notwendig sind, um Nutzungsrechte und kollektive Eigentumsstrukturen in Chile zu integrieren, wo marktorientierte Politiken schutzbedürftige Gemeinschaften marginalisiert haben. Durch die Analyse im Rahmen von Henri Lefebvres Theorie des Rechts auf die Stadt argumentiert die Arbeit, dass Wohnsicherheit, erreicht durch kollektives Eigentum, eine Grundlage für die Rückeroberung urbaner Räume durch die Menschen bildet.

In the last decades, housing has become the world’s biggest economic asset class (The Economist, 2020), illustrating the explosive increase in its economic value. On the other hand, many countries include housing as a basic social and constitutional right. In Latin America, only Chile and Peru do not include housing in their Constitutions. On an international level, the United Nations states that housing is a human right (United Nations General Assembly, 1948, Art. 25), however, in a global capitalist context of land price increase and less public agency, accessing a home both through traditional market and public policies is becoming almost impossible for a growing segment of western societies (Wetzstein, 2017).

In Latin America, during the second half of the 20th century, right wing governments and dictatorships were established with the support of the US, who were seeking to extend the neoliberal model and counteract the socialist movement backed and promoted by the USSR. In this context, local policies where heavily infuenced, as they reduced state’s power and gave more space to the private sector, reforming the political structures to align with liberal and market-oriented principles (Martínez Rangel & Reyes Garmendia, 2012).

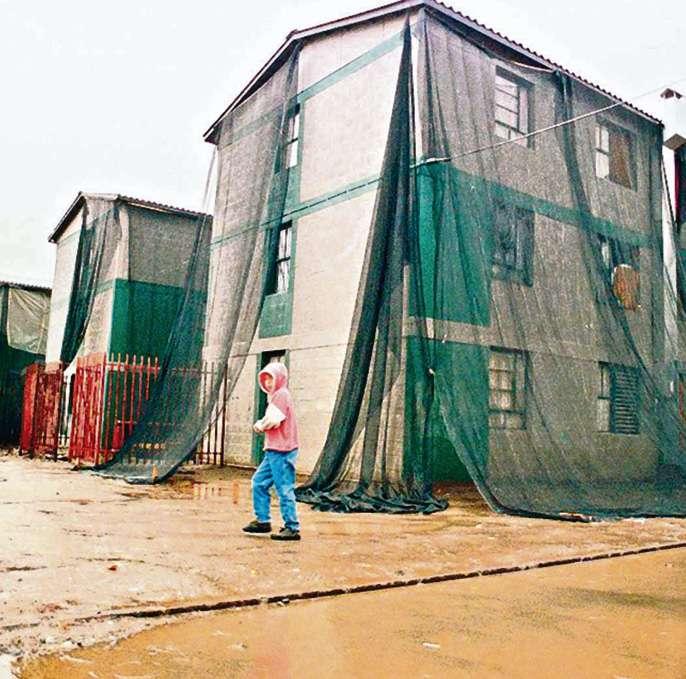

In Chile, during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973 –1990), neoliberal principles where deeply spread into housing policies, resulting in a model of demand-side subsidy where benefciaries are subjects to a voucher with which they can acquire a dwelling in the private market. These policies were (and still are) mostly oriented to housing in property for individual households, without considering self-organised communities as active producer of habitat nor collective tenure as a valuable strategy for housing. Moreover, the housing movements that existed before 1973 were heavily oppressed as they presented a threat to the neoliberal principles (fg. 1). These new policies started rooting not only locally, but also started spreading to other countries in Latin America as they presented a new alternative for economic growth.

During the 1990s, these policies were highly successful on decreasing the quantitative housing defcit. After the frst tumultuous years of the regime, the social and economic environment slowly stabilized, and market-oriented programmes became the mainstream strategy to satisfy social needs. The state not only gave a protagonist role to the market in housing, but also in every social need: health, education, and social security. It is in this economic framework that private companies could thrive developing housing projects with high income margins. However, to achieve this, they sacrifced the quality of the construction, and the location of the projects. Additionally, in order for the system to actually serve as proft generator, the role of people as active producers of the habitat during the middle of the century, mutated to become benefciaries of subsidies and clients of the social housing market. For instance, the regime changed the regulatory bodies of housing cooperatives, transforming them in a structure that is closer to a private company where individual proft is prioritized. The system only allowed individual property and tenure, supporting the idea of people as solely clients of the housing market. This process had devastating consequences for Chilean cities, it produced highly segregated areas of poverty, urban fragmentation, and an important problem of people living in poor-quality housing and neighbourhoods.

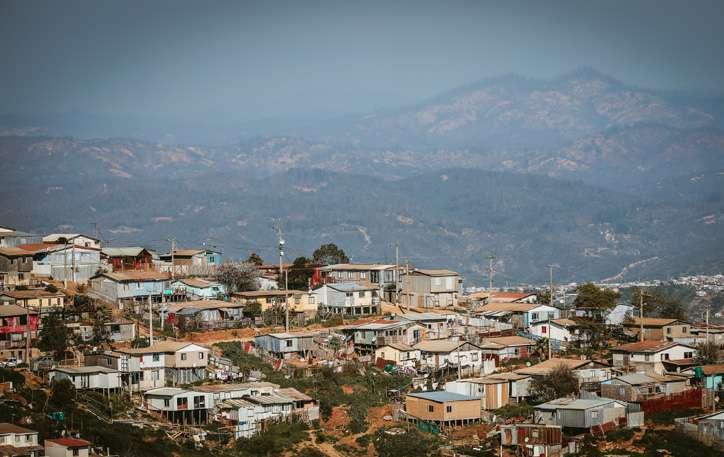

Currently, a new housing crisis is undergoing, where between 2019 and 2020, there was an increase of 73% of households living in campamentos, the

Chilean term to refer to informal settlements (TECHO-Chile, Fundación Vivienda, & CES, 2021). Although this is a valuable expression of organised communities’ active role in habitat production, it has many times negative impact over people’s life quality (a more in detail discussion will be given in chapter III and IV). In addition to this, an increase in rent prices and higher requirements for accessing mortgage loans over the last decades has created a quantitative housing defcit of around 660.000 units, and a social demand for housing of up to 2.210.000 (Défcit Cero, 2024), which include people living in overcrowded dwellings, irregular tenure, and other situations that are not traditionally included in the quantitative defcit. Moreover, there is a growing threat in major cities of being pushed to the periphery to make space for private developments. Nevertheless, there is also a re-emerging of pobladores movements (term to refer to organised groups seeking a housing solution, which usually has a non-party political character) who are seeing collective organisation as a strong path to achieve their right to the city in a system that does not recognise them as a protagonist actor in housing provision.

In this context, researchers, NGOs, and the government are looking for new alternatives to approach the crisis, and although more and more literature

is showing the relevance of people’s organisation and the key role they play in adequate housing, there are few researches that relate this struggle to alternative types of tenure. How can Chile’s housing system encourage a more prominent role for collective and self-organized communities in habitat production, recognizing this as the essence for the right to the city? Additionally, could collective tenure be a strategy to counteract the negative efects of a neoliberal housing model in campamentos?

To answer this, an international perspective is relevant as it provides learnings from similar experiences and can help tracing guidelines for alternative approaches to the housing problem in Chile. It is important to remark that the crisis is multi-factorial, and it can’t be approached from a single point of view, nor it has an absolute solution. Therefore, this thesis aims to propose improvements and suggestions to the current housing provision system in Chile, in order to allow more alternatives to emerge, specially from the people.

To do so, a qualitative case study is carried out, analysing cases in Latin America where people (including organised communities, NGOs, corporations, among others) are advocating for a stronger role of self-managed communities in housing production, with collective tenure playing a key role for providing housing security. Examples include Uruguay’s housing cooperative movement, Chile’s emerging one, Brazil’s favela communities, Puerto Rico’s Caño Martín Peña Community Land Trust (fg. 2), and collective initiatives in Bolivia. All these cases share a common objective of achieving community-driven housing through diferent degrees of collective tenure. This thesis considers these approaches as counter strategies to the challenges imposed by neoliberal policies.

The thesis is structured in four main parts: i) the analysis of Chile’s recent housing history, which serves as the foundation to understand the role of people throughout the diferent socio-political phases of the country, ii) the study of current housing policies and the characterization of campamentos, iii) the study of international cases, and iv) the discussion of fnding and the defnition of suggestions for the Chilean case. The frst two parts of the thesis are based on literature review, including academic publications, reports, legal texts, and newspapers. As for part iii), it also incorporates interviews of people involved in the case studies.

In 1968 Henri Lefebvre published his well-known book Le Droit à la Ville, which is translated as The Right to the City. This text serves as the theoretical foundation for this thesis. Specifcally, Lefevre defnes social needs –opposed to individual needs driven by a society of consumerism—as having an anthropological foundation, that is, they are rooted in existential aspects of humanity and go beyond the need of survival. He describes how these needs are opposed and complimentary, including the need of isolation and encounter, independence and communication, and of immediate and long-term perspectives, among many others (Lefebvre, 1996 [1968]). In this constellation of urban needs, adequate housing, the quintessential element of every city, becomes the starting point for human development, which he names as the efective realization of urban society. To achieve this, Lefebvre states that it is necessary to defeat current dominant strategies, consequently, this must be carried out by social life in its global capacity, where individual eforts can only clear the way and try out strategies (p.151). Thus, this work is framed on the concept of a right to the city that must be achieved through a societal transformation, inspired by cases of organized groups.

In the same period, the Brazilian scholar Theotônio dos Santos started discussing the concept of under development in a capitalist context of development (1970), showcasing how the theory of development was entering a crisis, and it would need to be re-defned as a theory of dependency. This theory argues that the under development of Latin American countries can’t be separated from the historic context, where rooted production and economic structures work for an existing system of colonialist capitalism, and therefore can’t be expected to succeed in the same ways that it did in advanced economies, as the historic processes of industrialization, production, and extraction are unique to each reality. The author states that the theory of dependency –which he denominates as a development model—oriented most scientifc research and national policies: being these parties programmes and political organisations (dos Santos, 1970). This theory is also the base for this thesis’ critical approach towards the implementation of neoliberal policies that were inspired and infuenced by the reality of a diferent historic context (USA). Although specifc housing policies were not directly transferred to the Chilean context, by following strict capitalist principles from a foreign developed context (abstractgeneral conditions), they failed to acknowledge the uniqueness of the local context (historic-specifc conditions, [dos Santos, 1970]). Following the author’s analysis, a similar unsuccessful outcome would have happened in a scenario where the USSR would have managed to implement socialists’ policies of mass housing production in Latin America, as it again fails to acknowledge the diferent local historic processes of both regions, specially associated to the industrialization process and overall urban dynamics. Thus, a context-specifc perspective over housing issues clarifes the failure of neoliberal policies, while at the same time provides a more accurate approach for the selection of international study cases, recognising the diversity of realities where the projects emerged, while at the same time acknowledging the common struggle and objective that people may have in diferent countries of Latin America.

At this point, it is necessary to delve in the defnition of tenure and tenure security. UN-Habitat defnes land tenure as “The way land is held or owned by individuals and groups, or the set of relationships legally or customarily defned amongst people with respect to land. In other words, tenure refects relationships between people and land directly, and between individuals and groups of people in their dealings in land”(2008). Following this defnition, collective tenure refers to ways of holding land by a group of people. Land tenure security is later defned as “i) the degree of confdence that land users will not be arbitrarily deprived or the rights they enjoy over land and the economic benefts that fow from it, ii)the certainty that an individual’s rights to land will be recognized by others and protected in cases of specifc challenges; or more specifcally, iii) the right of all individuals and groups to efective government protection against forced evictions” (UN-Habitat, 2008). Accordingly, Geofrey Payne et al. add that property rights may vary between tenure systems (local-specifc conditions) where there is not necessarily a co-relation between property rights and tenure security (Payne & Durand-Lasserve, 2013). Furthermore, Payne describes how security of tenure does not depend on a legal status of the communities but rather on people’s perception of past and present policies, where intermediate tenure systems –being these tenure arrangements that are not fully formalized nor are completely informal—provide more tenure security particularly to the urban poor (Payne, 2001, 2004). The author later defned three main tenure systems: customary, religious and statutory. The frst refers to traditional practices and norms, where land is typically held communally by a group (often based on tribal, ethnic, or kinship ties). Land use and allocation are managed by community leaders, such as chiefs, councils or elder. Religious tenure systems are those where land ownership and rights are regulated by religious laws and authorities. These systems are particularly common in Islamic countries, where religious principles play a major role in determining land ownership and usage. And lastly, Statutory tenure systems are formalized land tenure arrangements that are established by law, often based on written legal statutes or government regulations. These systems are generally associated to national or municipal laws and are typically enforced through legal institution (Payne & Durand-Lasserve, 2013). Considering that most Latin American political-economic systems can be considered among capitalist western societies, this thesis aims to study cases where organised groups are seeking to achieve statutory tenure security, which can incorporate intermediate or full arrangements, recognising the variety of rights and security levels that are pursued in each context.

Returning to the discussion of Lefebvre’s right to the city, David Harvey (2008) delves deeper in the impacts of capitalism and neoliberalism in the urban process. Specifcally, he criticizes the “immense concentrations of wealth, privilege and consumerism in almost all the cities of the world in the midst of an exploding “planet of slums”. For this, Latin American cities are the prime example of both uneven distribution of wealth and informal settlements, which tend to be two interconnected phenomena, as this uneven distribution produces a disproportionate accumulation of wealth (through housing properties as its main asset), and consequently creates signifcantly worst condition for a vast majority of population to access adequate housing. Harvey then continues explaining that his idea of a right to the city is to have agency in the process of urbanization and the make and re-make of cities (Harvey, 2008).

In Latin America, this agency is clearly illustrated through the expansion and multiplication of informal settlements. In this sense, Payne defnes that informal settlements’—considered generally as something negative— tenure arrangements are as follow: 1) unauthorized commercial land development, where legally owned land is subdivided and sold informally for housing development, and 2) squatter settlements, where private or public land is illegally occupied, and housing production is carried out regardless of planning and building codes (Payne, 2001). The scope of this thesis includes both informal tenure arrangements, however, it recognises that the cases are selected due to their goal of promoting the social value of housing over its economic value, in combination with a strong agency of communities.

This informal agency is what Ananya Roy defnes as a mode of urbanization (Roy, 2005). Rather than separating two sectors: the formal and informal, the author states that the latter is a “series of transactions that connect diferent economies and spaces to one another”. Additionally, Caldeiras’ defnition of informality as Peripheral Urbanization in the global south provides clear insights about how cities are produced by residents themselves. First, she defnes that the process is gradual over time, where people build their homes and neighbourhoods as resources become available. Secondly, it recognises residents as key agents of urbanization. Thirdly, similar to Roy’s ideas, she states that these urbanizations are an important factor in the formal urban dynamics. And fourth, these communities often become politically active, demanding better infrastructure, services, and recognition (Caldeira, 2017). Therefore, the term informal settlement is used to refer to dwellings that are an important element to city dynamic and that are strongly interconnected with them. It does not mean, in any case, a critique to their origin or development. Moreover, this study recognises that these settlements are in its essence an expression of the right to the city.

Among these informal settlements, collective and organized groups are challenging the reigning paradigm of individual housing tenure in diferent regions of the world. More and more communities are pursuing a protagonist role of the collective in deciding how they want to live, as this organisation provides better alternatives to access housing in a market logic (Czischke & Schlack, 2019). In this context, Jennifer Robinson arguments that the future of urban studies needs to be detached from ethnocentrism and intellectual division caused by a colonial past become extremely relevant. She suggests debunking the paradigm of global and world cities and start studying ordinary cities (which include all cities) with a post-colonial perspective (Robinson, 2006). Therefore, the selection of study cases refects the aim of this work to frst, recognise the distinctiveness of these ordinary cities and the agency over their own future, and second, to challenge the hierarchisation and categorisation of cities in urban studies (developed/under-developed, western, non-western, etc) in order to reach accurate outcomes for the Chilean context.

The collective tenure systems proposed by communities, can be considered as a type of collaborative housing. Darinka Czischke et al, while studying the specifc concept, conclude that this term is an umbrella defnition that encompass diferent degrees of collective self-organisation. Following this argument, the selected study cases of collaborative housing are characterised by a high degree of social contact with shared goals and motives in relation to the housing project, and a common aim to become active agents of their own

housing situation in two diferent levels: as individual autonomy to choose their way of living, and as collective autonomy to organise with people to achieve their objectives (Czischke et al., 2020).

Finally, this thesis is framed in what Brenner, Marcuse and Mayer (Brenner et al., 2009) defne as a critical approach to urban studies, this being, a study focused on the intersection between capitalism and urbanization, examining the “socio-spatial inequalities and political-institutional arrangements” that are a consequence of neoliberal urbanization processes, specifcally focused on the Chilean housing model. From that starting point and following the idea of the right to the city, this work carries out a study of fve cases of collaborative housing in Latin America with a post-colonial perspective and historic-specifc conditions. The cases include housing cooperatives (mutual aid), collective tenure (as Community Land Trust) in informal settlements, and diferent types of collective property as modes of urbanization. They illustrate the work of people who organised themselves to face the difculties imposed by decades of market-oriented housing policies, implementing counterstrategies to achieve housing security.

During the 90s, most of the published literature was studying the benefts, the transferability and the success of Chilean housing policies. However, in this optimistic context, María Elena Ducci (1997) was one of the frst voices to claim that Chilean housing policies implemented during the military regime were creating serious urban and social problems. Along with her, many authors started raising awareness of the negative outcomes of neoliberal urban policies overall (Gilber, 2003; Hevia Díaz, 2003; Orellana Ossandón, 2003; Sabatini et al., 2001; Sabatini & Arenas, 2000; Tironi, 2003). But the defnitive turning point was the publication of the article El problema de Vivienda de los “con techo” (The Housing issue of the ones with roof) by Ana Sugranyes and Alfredo Rodríguez. They defned the new housing problem as the Con Techo (‘with roof’, making a direct reference to the UN’s 1987 international year for the people without a home, in Chile called ‘roofess’). In this article, they described the many negative outcomes of the housing policies during the late 80s and 90s, for instance, the strong preference of quantity over quality, urban fragmentation over social integration, the prioritized relationship between private companies/ state over the participation of people, and the traditional building methods over innovative technologies (Rodríguez & Sugranyes, 2004) (fg. 3). Adding to this, in 2006, Isabel Brain and Francisco Sabatini also published a study describing how the demand-side subsidy system was failing to keep the pace to land prices (Brain & Sabatini, 2006), as most of the money ended up covering land costs.

In this context and accompanied by a regrowth of housing movements among people who were struggling to fnd a solution, most authors were working to disentangle the outcomes of decades of neoliberal housing policies to propose new paths to satisfy people’s housing need. For instance, Castillo, Forray and Sepúlveda described how housing policies were socially segregating Chilean cities with poor quality neighbourhoods, promoting insecurity, mental health issues and the perpetuation of poverty. They also advocated for a stronger and protagonist role of both people and the state as promoter of social and urban

development. They described the necessity of recognising the role of organised communities (who were already socially building their homes in campamentos) as members of a common task (Castillo Couve et al., 2008).

Opposite to this, a minor number of scholars did not see this issue as a problem rooted in the essence of housing policies. The economist José Miguel Simian wrote in 2010 a thorough study about the social housing industry in Chile, and although he was indeed critic with some aspects of it, the analysis failed to recognise the structural problems of market-oriented policies. As an example, the author mentions that, as subsidies do not require a specifc location, benefciaries are free to choose where they buy or build their homes, so it should not be a problem of the policy itself but rather a problem of the housing market (Simian, 2010), as if both elements where not strongly correlated.

From an international perspective, Rolnik’s work clearly illustrates how housing has been commodifed and fnancialized through a market-based housing system, impacting housing rights. She argues that neoliberalism has removed the meaning of housing as a social good and instead it is now considered a means to wealth through value appreciation (Rolnik, 2013).

Current Chilean literature is discussing the necessity for housing policies to include organised communities as active producers of the habitat, as this strategy is useful to return the social value of housing. For instance, Meza describes how self-managed communities have established consolidated strategies for housing production at the margin of housing policies, and the relevant role of these in the de-marketisation of housing production (Meza Corvalán, 2017). In the same line, Castillo discuss how pobladores and their knowledge has evolved according to diferent phases in housing policies, learning the know-how of the system and presenting themselves as relevant potential actors in the housing policy discussion (Castillo Couve, 2014), but it does not discuss the specifc case of campamentos, as the majority of people with housing needs have other housing arrangements. The literature also discusses the role of organised communities to

access housing in individual property, but there is a lack of research in alternative tenure methods that can produce long-term sustainability.

During the last fve years, Javier Ruiz-Tagle represents the movement forward of discussing specifc strategies to promote collaborative housing, mostly through housing cooperatives. In 2021, together with a group of scholars, they published proposals to implement cooperative housing in current Chilean housing system, addressing issues of tenure, organisation, technicalities and funding (Ruiz-Tagle et al., 2021). On her side, Darinka Czischke, specialized in collaborative housing, is also studying the benefts and opportunities of these methods, with an international perspective, drawing connecting threads between diferent realities with a shared aim of agency over the type of dwelling (Czischke & Schlack, 2019). On another article, Czischke, Urra, Ersoy and Gruis describe how collaborative housing, based on the few cases existing in Chile, present important opportunities to tackle the social defcit of housing (Czischke, 2018). This literature it is indeed important to illustrate the re-birth of a formerly oppressed cooperative movement, and its potential in the current housing crisis.

However, in all the revised literature, there is little space to discuss other types of tenure which are proven to provide housing security for communities in the international context. This might respond to the reigning paradigm of housing as individual property and as the main method to achieve economic security in a country where social services are scarce. A gap is also identifed in the target objective of studies, which are oriented to a part of people in need of housing that does not live in campamentos. However, as these settlements are growing, both in number and in surface, it is necessary to link the existing literature regarding housing provision with the reality within campamentos. Therefore, this thesis aims to contribute to the discussion of collaborative housing, giving hints from a regional perspective about alternative types of tenure that are suited to address the pressure of the housing market, with a specifc focus on people living in informal settlements.

Chile’s ongoing housing crisis is deeply rooted in the neoliberal policies that have infuenced urban development for decades. These policies, which prioritize market-driven housing production, have systematically marginalized low-income communities, specially people living in campamentos. These informal settlements represent a critical gap in the country’s housing strategy. Considering the diversity of them, existing policies have largely failed to address their specifc needs, leaving them vulnerable to social, economic, and environmental challenges.

Despite the challenges, there is a strong sense of community and organization among the people, with housing movements emerging after being heavily oppressed during the military dictatorship. In this context, international cases of self-management combined with collective tenure arrangements may demonstrate success as counter strategies to the pressures of housing markets.

This thesis seeks to explore the following research questions: How can the Chilean housing system promote a more signifcant role for collective and selfmanaged communities in habitat production, recognizing this as a foundational step towards the right to the city? Furthermore, can collective tenure serve as a strategy to mitigate the negative impacts of a neoliberal housing model?

The hypothesis is as follows: the collective organization and selfmanagement of communities through associations, cooperatives, Community Land Trusts, and other collective tenure arrangements ofer substantial opportunities of addressing the housing needs of Chilean campamentos. Specifcally, the hypothesis suggests that these tenure arrangements can serve as a counterstrategy to the negative impacts of neoliberal housing policies by fostering community empowerment, social cohesion, and overall housing security as the starting point towards the right to the city. Furthermore, the thesis proposes that policy adaptations, inspired by the experiences of international case studies, can play a key role for the efective implementation of such strategies.

This thesis is an instrumental case study of fve organized, self-managed communities that, through various forms of collective tenure within the framework of collaborative housing, have aimed (or are aiming) to achieve housing security in Latin American cities. The cases examined are the COVIREUS al Sur Housing Cooperative in Montevideo, Uruguay; the Caño Martín Peñas Community Land Trust (CLT) in San Juan, Puerto Rico; Hábitat para la Mujer Comunidad María Auxiliadora in Cochabamba, Bolivia; the Trapicheiros Favela TTC in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; and the Ñuke Mapu Housing Cooperative in Santiago, Chile (fg. 4). These cases were selected after a review of more than 10 diferent examples from the Global South. The selection was based on three factors: frst, the similarities in social, economic, and political contexts with Chile; second, the limited timeframe for completing this thesis; and third, the fact that these cases demonstrate a collective approach to addressing the challenges posed by neoliberal urban development. Future research might explore connections with other regions, such as East Asia or Africa, where interesting projects are emerging that address issues relevant to the Chilean context.

Caño Martín Peña CLT San Juan de Puerto Rico

Hábitat para la Mujer Comunidad

María Auxiliadora

Cochabamba, Bolivia

Trapicheiros, favela TTC Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Ñuke Mapu housing cooperative Santiago de Chile

COVIREUS al Sur Montevideo, Uruguay

The primary objective of this thesis is to analyse these international cases in terms of their legal and organizational backgrounds, specifc characteristics, key actors involved, and the spatial aspects of collaborative housing. The goal is to discuss the opportunities, benefts, and challenges that a similar approach could ofer for Chilean campamentos, and to provide suggestions for further developing collective strategies in housing provision for the (re)emerging collaborative movement in Chile.

A qualitative methodology is employed, focusing on three main sources of information: i) academic literature; ii) reports, data, and regulatory texts; and iii) semi-structured interviews.

The purpose of the interviews is to gather insights from individuals who were or are involved in the development of each case, in order to evaluate the challenges and benefts of promoting this approach within the Chilean context. The interviewees were selected for their expertise in the development of these housing projects, with roles ranging from legal advisors, organizers, and community leaders to researchers and activists:

For each international case, six diferent topics are to be analysed: i) the context (either social, political, or economic) in which the projects emerged, ii) the actors involved in the case, being these community-driven, public, private, or NGOs, iii) specifcity of the case and what makes it relevant for the study, iv) legally and organisational background that allows (or not) the case to success, v) a brief fnancing structure of the project, including the acquisition of land, construction, and the property of them, vi) spatial aspects of community living.

Through the review of academic literature, the thesis provides diferent perspectives on the study cases and examines housing policies in Chile over the past 50 years. This review highlights the dynamic emergence of housing movements in campamentos, their roles during various political-economic phases, and their adaptations to changing realities.

Additionally, the thesis includes a review of qualitative and quantitative data to characterize campamentos in terms of their diverse origins, compositions, and locations. This serves as a starting point for connecting with the study cases. Furthermore, a review of major Chilean housing programs and their regulations is provided to clarify the challenges and possibilities for alternative initiatives.

In Chile, as in many other countries, the housing provision system—and its diverse aspects—has been highly infuenced by diferent social, economic, and political phenomena, both local and international. In the following pages, the most signifcant housing policies from 1964 onwards, together with their impacts over the provision system in Chile, are described. To do so, local academic articles, books, and ofcial documents are analysed, while international literature provides a broader perspective of the global infuence over local policies. The timespan for the study is defned according to two signifcant turning points, one at the beginning and the other at the end. The frst one is the creation of the current Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning (Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo de Chile, MINVU) under Frei Montalva’s reformist administration, which was followed by other signifcant events in Chilean housing history. The second turning point corresponds to the frst mention of ‘social integration’ in Chilean housing policies, giving way to the current phase, which will be discussed in the next chapter. In between, three main phases are identifed to describe the evolution of the housing system in Chile: 1964-1973 as the reformist and socialist period, 1973-1989 as the neoliberal experiment, and 1990-2006 as the hybridisation of the system. Regarding the specifc site to analyse, the focus of this chapter lays on the city of Santiago, as in one hand it fosters almost half of Chile’s population, and on the other hand it portrays—to a greater or lesser degree—the similar urban processes that occurred in other cities.

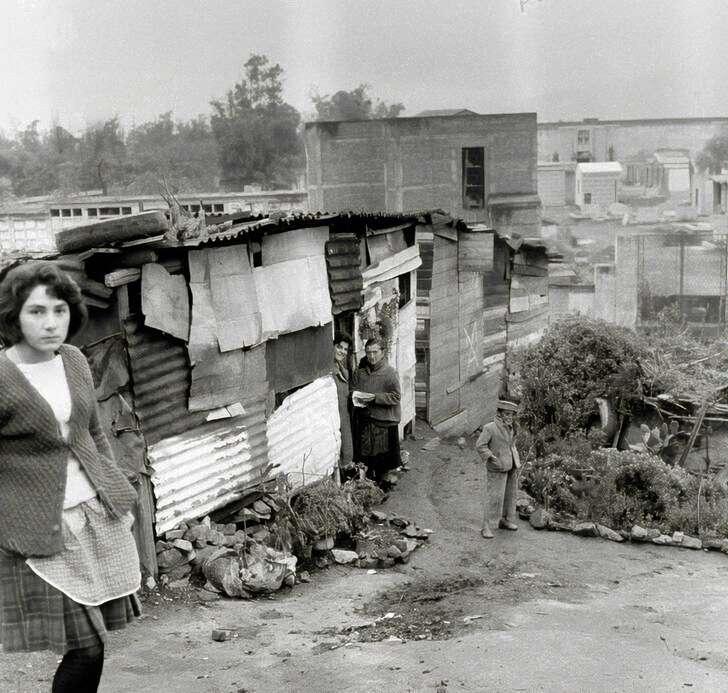

To comprehend the urban reality of this period, it is worth mentioning that the confguration of Chilean cities was deeply infuenced by rural-urban migration fows prompted by the advent of the industrial revolution since the end of the XIX century. People living in rural areas started to move to the city in mass, pursuing the dream of new opportunities and better living conditions. On a country level, the percentage of urban population escalated from 34,9% to 60,2% in the period of 1875 to 1952 (Servicio Nacional de Estadística y Censos, 1952), after which it signifcantly increased to 68,2% by 1960 (Dirección de Estadística y Censos, 1960). This unplanned process created substantial pressure over the capacity of the city to provide homes and urban services. Although the frst rural migrant to the city managed to allocate themselves in central areas by renting rooms in high density conventillos or cités (fg. 5), by the 1960s most of that population had been relocated to the periphery of the city, many times in poblaciones callampa1 located in tomas (occupied lands usually without basic services [fg. 6 and 7]) (Loyola, 1989). This meant that the urban surface of Santiago also increased accordingly. In this respect, the capacity of the state and private entities to ofer adequate housing was limited due to internal and external factors. That is why a not minor portion of public eforts to solve this issue were addressed to provide the so called ‘housing solutions’, a term used to refer not only to defnitive housing units, but also to the diferent alternatives that aimed to provide the starting point for a defnitive home, without considering location or habitability conditions (Castillo & Hidalgo, 2007). Since the decade

1 There are a few theories about the origin of the term poblaciones callampa, a slang term that translates directly to ‘mushroom-villages’. The most famous one refers to the fact that many of these occupations were organised to be done during the night, where a group of people would come together and set up a camp in empty lands. Worth noting the resemblance with similar methods in other regions of the world, like the Tŷ unnos in Wales or the Gecekondus in Türkiye.

of 1930, this resulted in the delivery of several empty—although many times served—plots of lands (sometimes they may have included a ‘sanitary booth’), an initiative that showcased the importance given to self-building and the main role of people in the development of their homes. By the beginning of the 1960s, the urban morphology of Santiago was therefore characterized by the exclusion of the urban poor from the city centre, who were living in self-built houses, poblaciones callampa, or minimal state-provided plots of land. Through interviews made to pobladores of Jorge Alessandri R. community (1968), the role of people in the development of their neighbourhoods is portrayed:

“His greatest pride, says Mr. Morales, is the building and completion of a classroom in the Public School Nº351, to be used during this year, the 70s, and the 80s, for classes that were essential due to the high number of students in need [sic] and the aforementioned school only had 6 classrooms.

This work became reality, says Mr. Morales with emphasis, thanks to the hard-working support of parents and tutors, who contributed both economically and physically.”

“Another aspiration that was successfully accomplished and which solution was appreciated by all the pobladores, was the installation of public lighting in the población, reality made possible with the contribution of the Ñuñoa district.

Mr. Morales with great emphasis tells us that currently, his and all the community leaders greatest concern, is to have a telephone in the población,

for which they are already negotiating with Promoción Popular2 the communal installation of a telephone, the only way of emergency communication in cases of disease or any other event that requires instant notice, at any time.”

Interview of Mr. José Morales, leader of Jorge Alessandri R. Community, for the newspaper El Cordillerano3 (1968), own translation.

2 Colloquial term referring to the Consejo Nacional de Promoción Popular (National Council of Popular Promotion). This institution was formed in 1964 under the Frei Montalva administration to promote dialogue, education, and solutions with base organisations among the people. The frst bottoms-up approach to urban challenges in Chile.

3 Local newspaper in Peñalolén, a district in Santiago. Its aim was to provide information, education, technical/legal advisory and overall empowerment to housing organisations in need under a catholic social justice perspective.

In 1964, Eduardo Frei Montalva was elected president on behalf of the Christian Democrats (DC), a centre-left wing party that proposed the ‘revolution in freedom’ for Chile. Frei Montalva’s government was an exemplary expression of the global geo-political situation at the time. On one side, many Latin American countries were following a path towards left-winged administrations, being the most prominent Cuba, with the success of the Cuban Revolution and its close ties with the USSR. This event inspired the Chilean Socialist Party (PS), which adopted farther leftist ideals. On the other side, the United States were seeking to protect their interests and avoid a bigger infuence of the USSR in the region. Therefore, in 1961, John F. Kennedy created the Alliance for Progress, an institution that proposed strategies for structural changes in Latin America as an alternative to a socialist revolution. In Chile, this alliance was represented by the DC and its connections with the European Christian Democrats (Moulian, 2018). Frei Montalva’s ideals were of a reformist nature, aiming to reduce inequality and secure basic rights like health, education, and housing. The administration also pursued a more prominent role of popular base organisations within the political context. Impregnated by fresh catholic ideals of social justice, new organised groups among popular communities were formed (Hidalgo, 2019), with some of them following a more radical path inspired by communist movements. These self-organisations aimed to unify common struggles like the fght for public services and housing, and to gain a stronger leverage in the negotiation with public entities. The general housing policy of this administration set a goal of building 360.000 units in the period 1964-1970, from which most would be units of 50 m2 (Hidalgo, 2019). As in the decades before, the main tenure system would be housing in property for single households, that would be achieved by the contribution of the state and family savings. Additionally, the DC administration promoted the creation of a diverse range of cooperatives, however this did not have the expected outcome in the housing sector, where there were only a limited number of existing workershousing-cooperatives created at the beginning of the XX century (Hidalgo, 2019). Nevertheless, amidst the emergence of organised pobladores groups, the government created new regulations promoting these community organisations, seeking to generate dialogue instances between people and the public apparatus.

In this political context, after some years of debate, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning was created (1965). Its role was to unify all the diferent entities that existed before, and to fll the gaps between the provision capacity of CORVI (Corporación de Vivienda, Housing Corporation in English), which at the time became the institution in charge of the design, construction, urbanisation, promotion and renovation of the majority of social housing and neighbourhoods), and the real demand for housing and city (Hidalgo, 2019). Together with it, a new public corporation was created under the name of Corporación de Mejoramiento Urbano (CORMU, Corporation for Urban Improvement), entity that also participated in in housing provision, but with a rather broader and deeper urban—modernist—perspective (fg. 8). Although there were still some actors against the creation of the mentioned institution, a broader consent between academics, public entities, and the Chilean Construction Chamber (CChC by its name in Spanish, to this day a powerful association of private companies in the construction sector) allowed its foundation. MINVU, with its limited economic capacities, soon realised that

the initial goals for state-built housing units was not going to be completed, and thus changed its strategy towards a site and service approach. In that period, four housing solutions were implemented: i) CORVI apartments of 60 m2 , ii) site and service with solid house of 27 – 30m2, iii)site and service, and iv) site only (Hidalgo, 2019). It is important to mention that most of the 1800 hectares of land used for the Operación Sitio (‘Site Operation’, name given to the site and service programme) were located in the periphery of the city (which now is the peri-central area of Santiago) (fg. 9 and 10). Again, as in the past decades, the role of people both economically and physically, this time with stronger organisations, became extremely relevant in the aforementioned housing policy, which contributed considerably to the current urban shape of Santiago.

In the year 1970, the occupation of land in the capital had evolved from being a frst necessity of a place to live in the 50s, to a settlement phenomenon due

Source: Hidalgo (2019), p 320.

to the explosive increase in the demand for land (Castillo & Forray, 2014). Thus, Santiago saw how the number of tomas increased from 8 in 1968, to 215 in 1970 (Quevedo & Sader, 1973), fostering some of the biggest campamentos in Chilean history. The politically polarized context of the time was fed by international conficts and fgures, while locally, strong reformist movements and social efervescence—with an active participation of pobladores created the necessary environment for the election of Salvador Allende, the frst democratically elected socialist president, on November 3rd of the same year. At the time, this event was perceived as one of the greatest threats to western capitalist economies, specially represented by US president R. Nixon and his National Security councillor Henry Kissinger (Casali Fuente, 2011). Although this fact may escape the scope of the thesis, it is the goal of the author to clarify the infuence of global politics over local realities. In a declassifed document, Henry Kissinger advised the former president:

“The election of Allende as President of Chile poses for us one of the most serious challenges ever faced in this hemisphere. Your decision as to what to do about it may be the most historic and difcult foreign afairs decision you will have to make this year, for what happens in Chile over the next six to twelve months will have ramifcations that will go far beyond just US-Chilean relations. They will have an efect on what happens in the rest of Latin America and the developing world; on what our future position will be in the hemisphere; and on the larger world picture, including our relations with the USSR. They will even

afect our own conception of what our role in the world is.”

Later he continues with one of three proposals which he clarifes is his favourite: “This view argues that we should not delay putting pressure on Allende and therefore should not wait to react to his moves with counterpunches. It considers the dangers of making our hostility public or of initiating the fght less important than making unambiguously clear what our position is and where we stand. It assumes that Allende does not really need our hostility to help consolidate himself, because if he did he would confront us now. Instead he appears to fear our hostility.

This approach therefore would call for (1) initiating punitive measures, such as terminating aid or economic embargo; (2) making every efort to rally international support for this position; and (3) declaring and publicizing our concern and hostility.”

Henry Kissinger on a Memorandum for the President, November (1970, p. 1,6)

Allende, representing the Unidad Popular (UP) political coalition, proposed a diferent approach to social housing. In the past decade, the communist and socialist parties were critics with DC housing policies of site and service as -according to them- they relied on the exploitation of workers for its success. Instead, as Rodrigo Hidalgo explains, in Allende’s government, the responsibility of providing housing for the people was one of the main responsibilities of the state, changing the self-building paradigm of the time (Hidalgo, 2019). According to the author, Allende’s housing programme was similar to the Cuban one. Nevertheless, due to diverse causes like the high infation, low economic capacity of the state, and an important demographic growth, the ambitious goals of the UP Government were not met (R. A. Hidalgo Dattwyler et al., 2016), and in September of 1973, a military coup ended with the socialist government and Allende’s life. During this period as well, many pobladores’ movements fghting for housing and urban services became more radical, being the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR) an important

paramilitary organisation that spread its infuence across land-occupation settlements in Santiago (Hidalgo, 2019). Additionally during this period, a short process of toma asistida (assisted occupation), where campamentos developed and transformed into neighbourhoods through the cooperation of the state and pobladores, marked Allende’s presidency (Castillo & Forray, 2014)

Worth mentioning that in the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale, Pedro Alonso and Hugo Palmarola presented the exhibition ‘Panel’, which showcased the symbolically charged trajectory of the frst prefabricated KPD concrete panel built in the factory donated by the USSR to Chile in 1972. This panel was hand signed by Salvador Allende, however after the military coup, the new administration under the Navy’s command “covered the signature and painted the panel, adding an altarpiece of the Virgin Mary and child instead of a window and two neocolonial lamps at each side” (Alonso & Palmarola, 2015). This exhibition showcases what Theotônio dos Santos defned as dependency theory, where diferent foreign powers (USA and the USSR) deeply infuenced the local reality without considering the specifcities of their histories.

The period between 1964 and 1973 was characterized by the recognition of housing as a social right, and a partial systematic involvement of people in housing production (recognising the aversion of socialist policies to what they defned as ‘people’s exploitation’), mostly through self-building and the recognition/promotion of organised groups of pobladores who would negotiate with diferent public entities in charge of fnancing, developing, and building housing projects. The power of organised groups was also refected on the amount of tomas that occurred during this period. As the limited capacities of the state were not enough, people would take the issue in their own hands, frstly as a response to bare necessities, and later as a symbolic political fght. Nevertheless, apart from specifc projects during the UP times, this period was also characterized by the exclusion of the poor to the periphery, worsening the socio-spatial gap of the city. Finally, after the coup in 1973, the last attempts to provide state-built housing ended for the country, giving rise to new neoliberal housing policies that would treat people as clients, rejecting their participation in housing production.

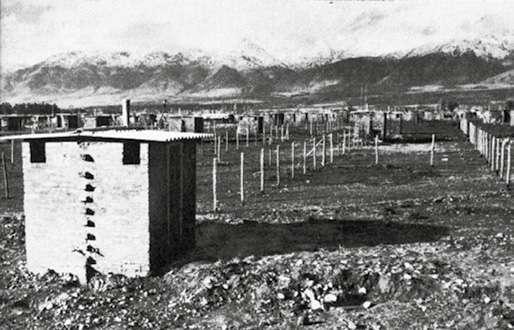

After the violent military coup of 1973 led by Augusto Pinochet, a process of ‘de-structuration’ of the existing regulations for basic services and rights— housing included—began (R. A. Hidalgo Dattwyler et al., 2016). Together with the prohibition of political parties, social movements were violently repressed, and the tomas were strictly prohibited (fg. 11 and 12). As Ducci states, it can be understood that during this period there was a clear motif to halt the poor from ‘creating their own city’ (Ducci, 1997). On the economic side, at the end of 1973 the country was in a severe crisis, and thus the regime decided to liberalize the economy, giving birth to the frst neoliberal project (Harvey, 2005).

It began with the ‘Chicago boys’, a popular name given to Chilean economists trained in the University of Chicago following Milton Friedmann’s economic ideals. Due to their ties with the Navy, institution in charge of the Finance Ministry at the time, a selected group of these professionals were called in to re-build the Chilean economy. In an accurate defnition while discussing

neoliberalism in the urban US condition, Neil Brenner and Nik Theodore describe:

“Neoliberalism hinges upon the active mobilization of state power. Neoliberalism does not entail the “rolling back” of state regulation and the “rolling forward” of market; instead, it generates a complex reconstitution of state-economy relations in which state institutions are actively mobilized to promote market-based regulatory arrangements;” (Brenner & Theodore, 2005)

This defnition represents accurately the policies established by the military regime, which included the cancellation of industries’ nationalization processes and the privatization of public assets. They also privatized social security and created a regulatory environment to promote foreign direct investment and repatriation of profts (Harvey, 2005). As expected, it also had a direct impact over the housing provision system, in the years 1975-1978, a new demandsubsidy policy began, which was characterized by the delivery of vouchers to cofnance units in the housing market (Ducci, 1997; R. A. Hidalgo Dattwyler et al., 2016), an element that has a central role to this day, even being replicated on a regional level. In this period, MINVU would base its system in the delivery of a subsidy to benefciaries that could prove own savings—mostly through mortgage loans—in order to buy a house built by private companies in cheap lands, with generally low urban services (R. A. Hidalgo Dattwyler et al., 2016). A system of points was introduced to defne the benefciaries (Tapia Zarricueta, 2011), giving no space to other kind of people’s involvement. As mentioned before, this new approach meant that housing was not considered a social right, but rather a consumer good. In addition to this, the Military Board applied a strong eradication programme, aiming to re-locate the campamentos from the central districts of Santiago to the periphery, in highly proftable housing projects located in cheap land (fg. 13).

In 1979, the Military Board was facing another economic crisis, and the number of housing units built per year was signifcantly exceeded by the demand. With the contribution of the Architects Institute and the Chilean Engineers Institute, the regime diagnosed that cities were the path to territorial cohesion and national security and would therefore create a new National Urban Development Policy to tackle the existing problems. However, as in the last seven years, the programme followed neoliberal principles, expanding the urban surface of the city, and liberalizing regulations to promote the most proftable private investment. Land was declared a ‘not scarce’ good, and social housing production was driven by private proft, which forced the relocation of campamentos to the southern periphery of the city. Contrary to the expectations of the regime, land prices increased notoriously, which led to the replacement of the 1979 Urban Policy by a new one in 1985 that defned land as an economically scarce good (Alvarado Leyton & Elgueda Labra, 2021)

The eradication process continued until the end of Pinochet’s dictatorship, who after feeling the international pressure and internal dissatisfaction, called for a referendum where the people rejected the continuity of the military regime. Before this, in one of his last attempts to gain peoples appreciation, he claimed that they were pursuing in Chile a nation of owners, and not workers (Augusto Pinochet, 1987), making a direct reference to Fracisco Franco’s housing minister who said in the 50s “we don’t want a Spain of workers, but that of owners”(D. Jose Luis de Arrese, 1959. Own translation).

In 1989 a period of extreme neoliberal changes ended, characterized by the prioritization of economic proft and private investment over urban or social aspects. There are still some debates regarding the extent of US infuence over Pinochet’s policies (see Brender, 2010), however, the historic events suggest that the neoliberal reforms were born in the US University of Chicago, and with direct or indirect help from the US Government, applied in Chile, shaping urban policies and thus our cities. In housing, the role of the state as producer and promoter was almost completely replaced by the private market, giving MINVU a subsidiary role. As for the people, the existing organised groups fghting for the right to housing were considered as clients, being excluded from participating in the process of housing provision. This legacy still exists, the demand-subsidy system continues to these days, and the urban problems created by it are still a reality in Santiago and many Chilean cities.

3.4. 1990-2006: the hybridisation of a neoliberal system in housing provision

The impacts of neoliberal policies over the quantitative housing defcit were not as successful as their creators expected. If in 1973 the housing defcit was around 590.000 units, by 1990 it reached almost a million homes (R. Hidalgo Dattwyler, 1999; Hidalgo, 2019), which even considering the population growth of that period still represents a slightly higher ratio per inhabitant, being 0,067 and 0,074 respectively (own calculation, based on INE, 1970, 1993). Besides this, there was a serious problem with the focalization of the subsidies. According to a study from 1983, the housing programme operated with a clear orientation towards middle and middle-high classes, where 67% of state’s benefts would be captured by higher-income groups, and only around 17% would go in beneft of the lower sectors (Necochea, 1986). Nevertheless, in the last years of Pinochet’s regime, there was a more stable socio-economic situation, where the housing production reached 90.000 units per year (Rugiero Pérez, 1998).

In this context, and after the victory of Patricio Aylwin in 1990, who represented the Concertación de Partidos por la Democracia (Coalition of Parties for Democracy), a new phase in housing policies began, where the government tried to fnd a balance between the existing neoliberal political and economic environment created by the military institutions, and a better wealth distribution in search of improving living conditions for the most underprivileged population. In an international level, the World Bank promoted a change in the role of states as active producers of housing to an administrative facilitator, aiming to tackle the housing defcit while boosting the economy (Fuster-Farfán, 2019), which Chile and other countries in the region considered most adequate by the time. This stage, that Fuster-Farfán describes as ‘hybrid neoliberalism’ aimed to secure and improve the participation of the three main actors in the housing provision system: people, state, and market (2019) in addition to promote the application of collective organisations for housing solutions (Hidalgo, 2019). However, and considering the quantitative success of the end of the 80s, it also perpetuated and reinforced the subsidy model for housing production, this time oriented to the ‘basic house’ model (the minimal built unit provided to lower-income households). Regarding tomas, the end of the 80s and the beginning of the 90s was a period with almost no new occupations, in the frst because it was strictly forbidden and the participation of people entailed the exclusion of any other

state’s beneft; and in the latter because there was an active efort of dialogue and contention to avoid new tomas (Castillo & Forray, 2014). In general, this period of economic bonanza and political stability with a market-friendly political environment led the 90s to become the decade with the highest decrease in housing defcit for Chile, from around a million units to 450.000 before the new millennium (Hidalgo, 2019), and a signifcant decrease in the number of campamentos, giving birth to what is known as the Chilean model.

However, at the beginning of the 2000, many voices started to raise concerns about the negative outcomes of these housing policies, which produced severe social and spatial segregation, vast areas of low-income socio-economic homogeneity, low quality constructions, and all the many subsequent impacts in life quality (Brain & Sabatini, 2006; Ducci, 1997; R. Hidalgo Dattwyler, 2004; Rodríguez & Sugranyes, 2004). Among these voices, Alfredo Rodríguez and Ana Sugranyes wrote one of the most relevant and eloquent texts describing

the socio-spatial reality of social housing inhabitants. Among other things, they describe how proft-oriented policies produced housing with poor quality construction. For instance, a project from 1997 named Casas Copeva—name given because of the building company Copeva—became historically infamous due to severe fooding of the apartments in the very frst winter after they were given to their owners (fg. 14). Some of them received a compensation from the state ffteen years later (2012), that reached only $2.900.000 clp. or €4.640 at the time (Velásquez Ojeda, 2018).

In the article, the authors also analyse the perspective of the three main

actors in housing production: the ‘users’, the state, and the CChC:

“The users

From the survey applied to the social housing stock users, a decisive fact arises: 64,5% of users want to ‘leave their home’. The reasons for this are of a social nature. Neighbour’s coexistence, insecurity perception, crime and drugs, are among the most signifcant motives; that’s the opinion of 52,6% of them.”

“It can also be said that, among the users wanting to leave, 90% feel shame and fear of their neighbourhood”

“Institutions

The territorial dimension –this is, the location of the housing complexes, the relationship between themselves and the city—, it’s not a primary concern for MINVU, who seeks mostly a better focalization of state’s resources to the lowest sectors, neglecting the importance of the location and environment of the future placer were these people will live.

From the Chilean Construction Chamber, there is a remarked interest on understanding the satisfaction levels among pobladores of social housing. This interest responds to the possibility of this stock to be used as a alternative for the demand of the poor, applying broadly the concept of housing mobility, which would allow the building sector to focus on more expensive housing units, and therefore stop ‘sacrifcing’ land for such low investments as social housing” (Rodríguez & Sugranyes, 2004)

In 2006, an article described the land price dynamics related to the development of social housing projects: it gives the example of how in the lowincome district of El Bosque, with a high number of social housing projects, the land price presented an annual proftability of 19,4%, while the high-income district of Providencia only reached 3,2% (Brain & Sabatini, 2006). The article clarifes how years of market-oriented housing policies—in addition to an overall stable land-price increase—, caused enormous levels of socio-spatial segregation in many Chilean cities, while at the same time stating the relevance of addressing this issue from an urban governance perspective. Thus, in the same year, for the frst time in local history, the Government issue the Decree Nº174 regulating housing policies and including the term ‘social integration’, aiming to tackle the high segregation levels (Decreto 174 | Reglamenta Programa Fondo Solidario de Vivienda, 2006). This event marked the beginning of a new phase in housing policies, changing its market-oriented path to a more integral perspective, gaining relevance in the public discussion over the future of Chilean cities.

Chile’s housing policies have undergone signifcant changes over the years, infuenced by various socio-political events both within and outside the country. Key characteristics of these policies have persisted for decades, while others have only been in place for short periods. Between 1964 and 1973, Chile experienced reformist and socialist housing programs. Under Frei Montalva’s administration, housing policies encouraged self-organization and active participation in housing provision. The government recognized housing as a

social right and collaborated with various public, private, and community actors to provide defnitive solutions. Although cooperatives were promoted, most housing solutions were single-family homes and individual properties. The ambitious goals set by the government were not fully met, and the Operación Sitio programme relocated many families to the periphery of Santiago. During this period, institutional changes were made with the creation of MINVU, CORMU, and the consolidation of CORVI. Internationally, these policies were supported by the US’s Alliance for Progress program, which aimed to ofer an alternative to socialism in Latin America.

Salvador Allende’s socialist period between 1970 and 1973 was characterised by the recognition of housing as a social right for which the state had the main responsibility to provide a solution. The Cuban housing model was the closest reference (the USSR donated a prefabricated concrete factory, similar to the ones used in the Caribbean country). Allende’s policies were against people exploitation, and thus they did not promote programmes oriented to self-help or explicit participation of people in habitat production, as –for them—that was mainly task of the state. They soon realised that the economic capacities of the state—diminished by international economic pressure, specially from the US, and internal rejection from the economic elites—were not enough to satisfy the growing demand. The internal social climate was also polarized, and paramilitary organisation would start to use and promote tomas as a fghting method rather than as a frst necessity, thus, land occupation peaked during this period. Nevertheless, it all fnished with the military coup of September 11th , 1973, ending with the last publicly produced housing policies.

During the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, new neoliberal policies were implemented, directly imported from the University of Chicago. These included halting all socialist programmes in every major sector. In this period, housing was a right that had to be earned with the work and savings of the family, and with a contribution of the state (Hidalgo, 2019). The role of the state as organizer, promoter and producer of housing was transformed to a provider of the adequate political-economic conditions for private companies to take care of housing provision. Consequently, the role of people as active actors in housing production and land access soon became a role of client who would buy a home in the private market with a public subsidy or voucher. During these years, many campamentos were violently relocated in the periphery of the city, increasing the existing socio-spatial segregation. The housing programme was not as successful as expected due to high prices of land and economic crisis. Therefore, in 1979 a new urban national policy was implemented, which was marked by the liberalization of land for private investments. After its failure and the price increase in land value, the law was changed in 1985. By the end of the military dictatorship, the social and economic internal environment was notoriously more stable, and housing production—from a quantitative perspective—was reaching a clear success.

With the advent of democracy in 1990, a neoliberal hybridisation period began, which was characterised by the perpetuation of neoliberal policies, but with new characteristics that would allow a stronger involvement of people in the process. This decade was highly successful in decreasing the quantitative housing defcit, decreasing the number of campamentos like never before. However, this success relied on private companies buying cheap land, highly defcient constructions, and severe impact in people’s life quality. By the beginning of the

new millennium, awareness was growing among academics and politicians that this issue needed to be addressed urgently, and therefore in 2006, the frst social integration policy was published, giving way to the current phase in housing policies.

Across the whole analysed period, a wide range of housing policies has been implemented, with some of them being more successful than other, and with some of them receiving a bigger rejection from society or the international community. Nevertheless, some key elements have been constant through the years. Firstly, the concept of housing has always been of a privately and individually owned unit—even in the socialist period most units were given in property to owners—and within the Operación Sitio, the land was also given in property to the inhabitants. Secondly, in the diferent analysed phases, the poor have always been excluded from the central areas of the cities, either to new sites provided by the state or to campamentos. Although it must be recognised that former peripheral areas are currently peri-central sectors in Santiago, there was a constant trend to move the lower-income population to cheaper and badly served land. Thirdly, even though in the period of 1973-1990 they were violently repressed, people’s organisation has always been a key factor in housing policy, either by being recognised as an element of public policies, or by being used as a way of collectively fghting for the right to housing. Tomas and campamentos are the most prominent example of this organisation, and they persist as a fghting tool to these days. Therefore, the recognition of these three aspects is essential to face current housing challenges, and it is of most importance to recognise the role that organised people can play in land acquisition and housing production.

As discussed in the previous chapter, Chilean housing policies throughout the last decades had been characterized by a withdrawal of the state as an active producer and promoter, shifting to a role of enabler and creator of the adequate regulatory framework for private entities to provide housing for the poor. Accordingly, peoples’ active role since the 1960s, changed to a passive role of voucher receiver to buy a house in the private market. What was stable during the whole period was the systematic exclusion of the poor from the city centre, and thus from essential urban services, creating highly segregated areas, both spatially and socially.

Policies based on demand-subsidy have created a problem that involves not only the number of dwellings that need to be built but also the possibility of building them on well-located land. Nearly 20 years ago, an article by Brain and Sabatini showed that increasing the economic contributions through state vouchers is insufcient to cope with the rising land-prices, most of which go towards land acquisition. In ‘social housing districts’, land proft is signifcantly higher than in wealthier districts (Brain & Sabatini, 2006). Consequently, following the locational pattern of the late 20th century, new projects are

Figure 16: Location of campamentos 2022-2023.

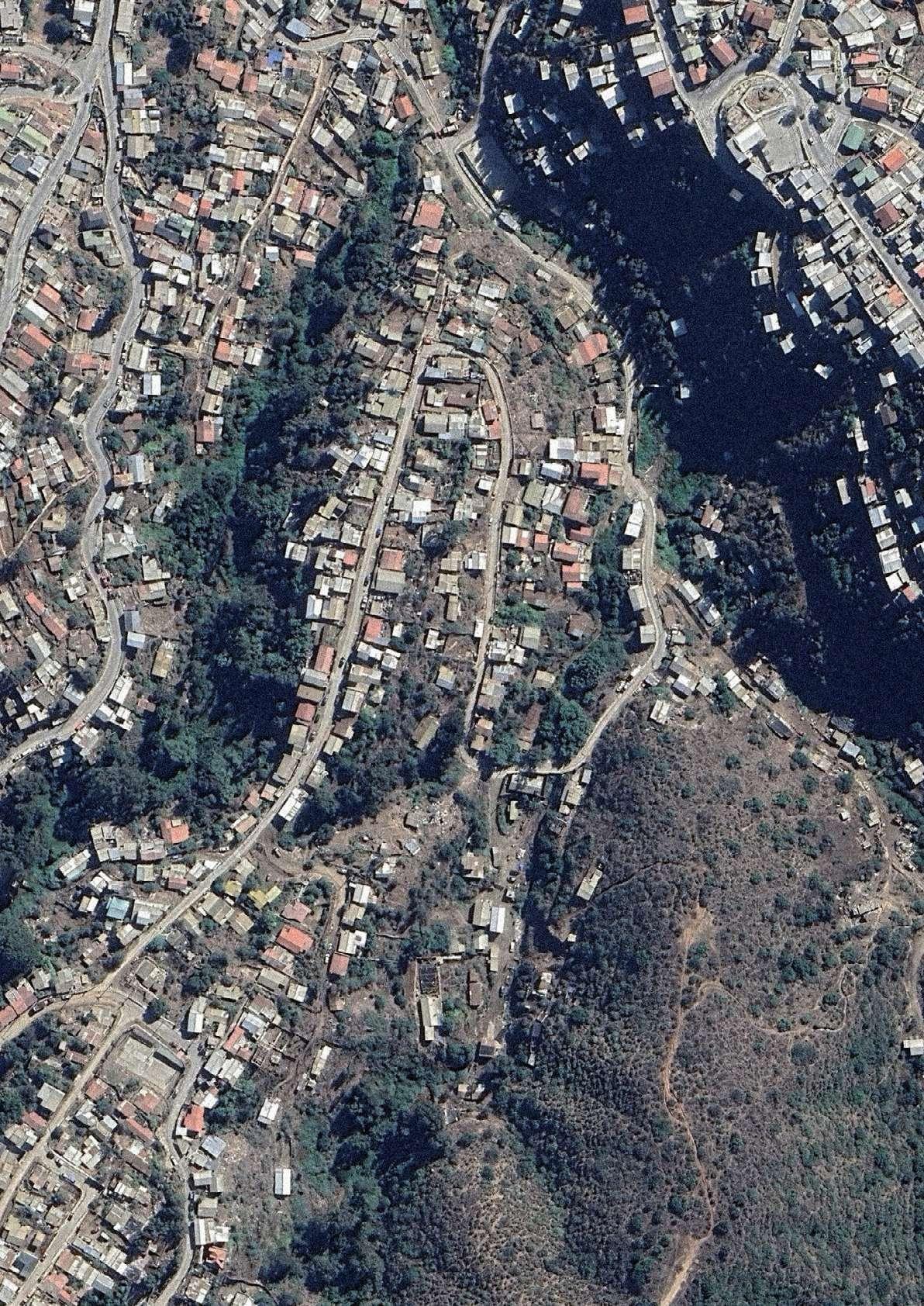

primarily situated in peripheral areas where land prices are low enough for private companies to develop. Furthermore, the existing social housing stock built in the 1990s has severe issues related to poor construction quality, overcrowding, allegamiento (more than one household in the same home), lack of public services, and overall spatial segregation, leading to precarious living conditions for the most vulnerable inhabitants. Additionally, the difculty to access housing either in the traditional market, or through public subsidies; the high levels of migration from other countries in the region (especially since 2010); and the economic consequences of COVID-19 pandemic, produced an increase of 73% in the number of households living in campamentos, reaching 81.643 families in 969 settlements, numbers that have not been seen since 1996 (TECHO-Chile, 2021).

These settlements have extremely relevant organisational characteristics, but they also often involve tenure insecurity and lack of public services, among other problems. This way of creating cities is what Caldeira (2017) defned as Peripheral Urbanization, however traditional housing policies have failed to acknowledge their social and urban value, and they have been traditionally excluded from the ‘housing defcit’, a term most commonly used in Latin America to refer a statistical and political indicator (or group of indicators) of an unsatisfed demand of housing needs (Moreno Crossley, 2015), and it has been particularly surveyed to be dealt with focalized public programmes.

Before examining the performance of these programmes, it is necessary to characterize the campamentos and clarify—as precise as possible—their composition, location, size, origin, and the aspirations of their inhabitants. To do so, this thesis analyses national reports and literature, and it is based mainly in: i) the study carried out by the NGO Défcit Cero (2024), where a thorough analysis of data was done to defne fve diferent typologies of campamentos, and ii) the data collected by TECHO-Chile, an NGO that since 2001 measures the number of settlements and families living in them.

Favelas in Brasil, Villas miseria in Argentina, or Campamentos in Chile, are all terms referring to often precarious and self-built settlements, which are usually located in occupied land, with limited access to public services and infrastructure. According to the Participatory Slum Upgrading Programme PSUP, around 30% of the developing countries’ population reside in these settlements, while in Latin America and the Caribbean, this number reaches 21% (PSUP, 2016). In Chile, campamentos are the physical expression of the difculties for the poor to access adequate housing. TECHO-Chile defnes campamentos as “a group of eight or more families forming a socio-territorial unit, without regular access to (at least) one basic service: sewage, drinking water or electricity; in a notformalized tenure; and with a requirement for housing”(TECHO-Chile, 2023. Own translation).

In 2005, the number of campamentos touched its lowest point, with 453 settlements and 24.940 families living in them (Un Techo para Chile, 2005) –most likely associated to the boom in social housing construction in the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s—but started escalating again in 2007, reaching

Source: Own elaboration. Data from TECHO Chile (2023)

17: Number of campamentos and families living in them in the period 2001-2023. Source: TECHO Chile (2023a). Own translation and intervention (colour change).

1.290 campamentos fostering 113.887 families in 2023 (fg. 17).

Moreover, the number of campamentos has increased at a lower pace compared to the number of families that inhabits them. Therefore, they are growing in size and density, often requiring more public services and equipment. The average number of families also varies according to the region, being the biggest number in the northern regions of Arica y Parinacota, and Tarapacá. After these comes the Metropolitan Region, where Santiago is located. Nevertheless, in absolute numbers, the biggest concentration of campamentos and families is in the central Matropolitan Region and Valparaíso (TECHO-Chile, 2023).

18: Average number of families per campamento in the period 2001-2023. Source: TECHO Chile (2023b). Own

(colour change).

AricayParinacotaTarapacáAntofagastaAtacamaCoquimboValparaísoMatropolitanO´HigginsMauleÑubleBiobío

Figure 19: Average number of families per campamento per region in 2023. Source: TECHO Chile (2023c). Own translation and intervention (colour change).

Figure 20: Number of campamentos and number of families living in them in 2023. The biggest numbers in Valparaíso and Metropolitana Source: TECHO Chile (2023d). Own translation and intervention (colour change).

The origin of the residents also varies, and immigrants are a signifcant portion of the people living in campamentos. In general terms, almost 35% of the families living there come from other countries, mostly from Latin America. Their location is predominantly in campamentos at the northern and Metropolitan regions. Although in Magallanes the total number of campamentos is low, it has one of the highest percentages of immigrant families (fg. 21). Regarding the reasons why they settle in campamentos, TECHO Chile defned seven main motives to do so, where the most commons are the high prices of rent, independence (stop being allegados), and low income. Furthermore, they realized that around 77% of the families were already living in the same district, 12% come from a diferent district as the campamento, and only 6,2% come directly from other countries, which would mean that immigrant families arrived to other type of settlements before moving to a campamento (fg.22).

Disasters (wildfre, earthquake, landslide, etc)

To speed up a housing solution form the state

Possibility to have agency about housing

Regarding the decision for choosing the specifc land where campamentos are settled, the vast majority of residents mentions that is due to the availability of underused or unused land (74,5%). Additionally, almost 23% mentions that

Sold or leased land Other

Security in the area

Close to services and equipment

Close to work

Close to former home

Privately ceded land

Publicly ceded land

Public land

Underused or unused land

it was because the land is public, and a 17,1% because the land is close to their former homes.