Our Heritage Place Mzinigan

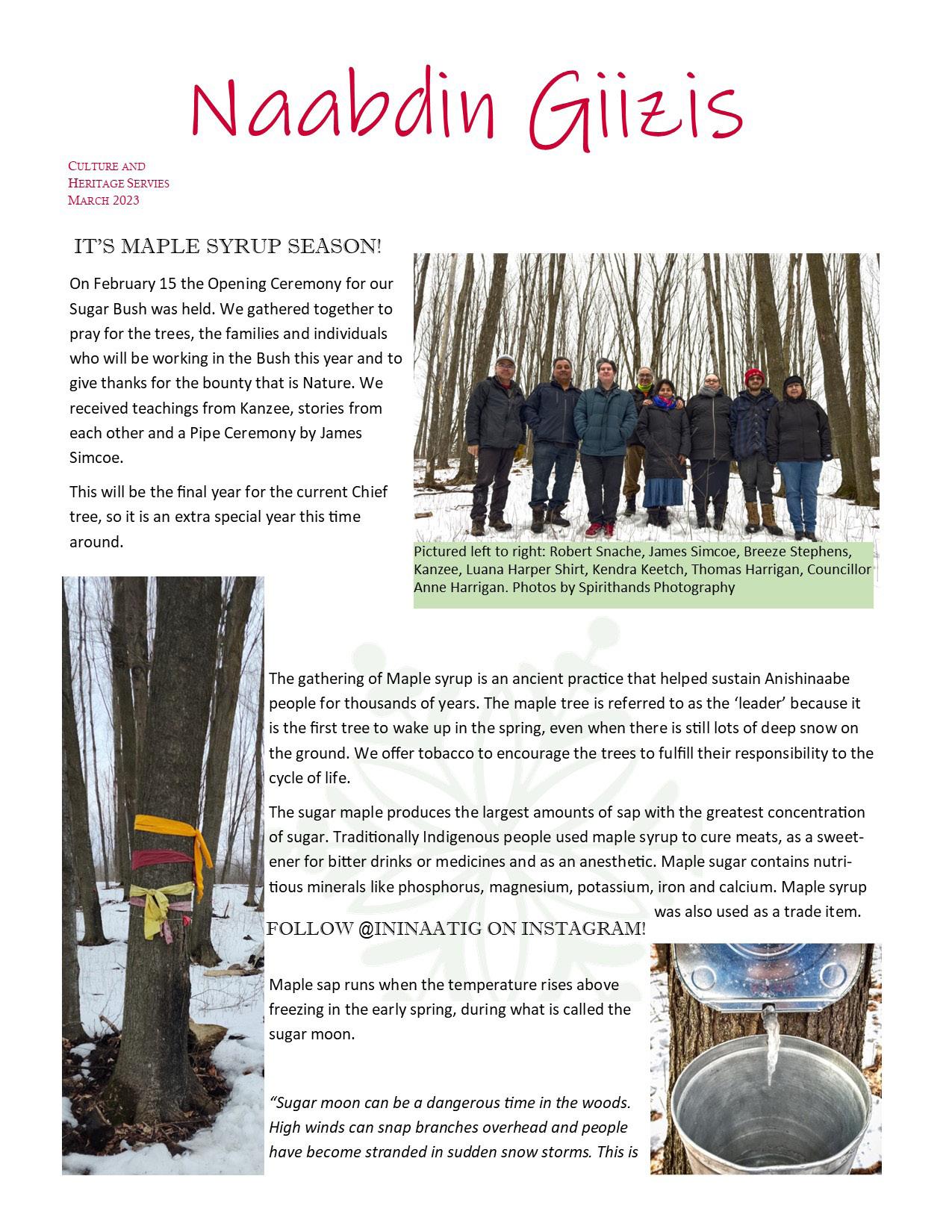

In the summer of 2022, Our Heritage Place was notified of a successful grant application. The grant was for a community sugar shack as well as an evaporator and a sap storage resevoir. In the fall, we were able to purchase a pre-fab sugar shack!

Public works did some clean-up of the bush, including felling some dead trees and pouring a concrete slab for the shack. The sugar shack was delivered to the Maple Avenue sugar bush and we were handed the keys.

We are very excited to have a beautiful (and a dry, wind-free) location to make that delicious food and medicine we call ziisbaakwadwaaboo (maple syrup). Several families have taken up Our Heritage Place’s programming offer of a family sugar bush (in which supplies were provided for free) and they, as well as annual maple bush waadookaaged (helper) Robert Snache, will be creating some delicious maple syrup over the next couple months.

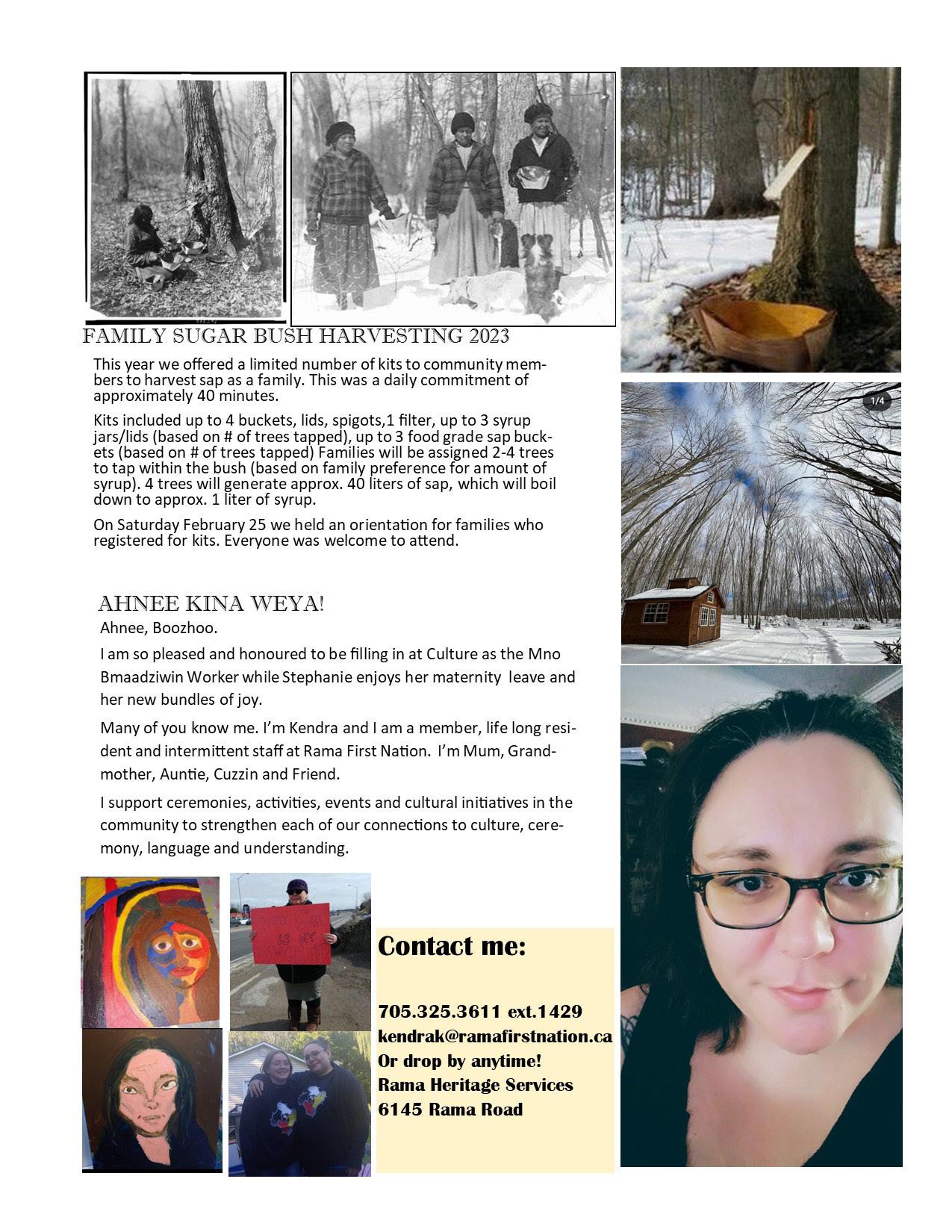

Mino Bmaadziwin Worker Stephanie McInnis recently welcomed twins! Congratulations Stephanie and family. Stephanie will be off on maternity leave for a while. Kendra Keetch has stepped in to fill Stephanie’s role while she is at home with her bebiinsag (babies). Kendra offers an “aaniin” later in the mzinigan.

Anishinaabemowin Naagaanzid Jessica Shonias and her team of Anishinaabemowin staff are doing some amazing work getting the immersion daycare up and running. Staff have been hired to begin working at the current Rama daycare in what will be the temporary Anishinaabemowin immersion room, prior to their move to Giiwedin Ki’s Maple building. The Maple building at Giiwedin Ki will be the home of the immersion daycare. This is a very exciting, and has been the dream of many language teachers and speakers for a long time. The immersion daycare is the beginning of community language reclamation.

Anishinaabe Waadookaaged James Simcoe continues to be ever-busy, organizing and assisting with ceremony, cultural teachings, and helping us all learn more about who we are as Anishinaabe.

Researcher/Archivist Ben Cousineau has transitioned over to the Communications Department, albeit carrying on much of the same research work. Ben will still maintain close ties to Our Heritage Place and assist with research and history whenever needed.

Otherwise, believe it or not but planning for the 2023 Rama Powwow has already started. Last year we saw record attendance and it was an incredible weekend. Such a big event takes many months to plan and we are excited to release some new information in the coming weeks. Stay tuned! For now, save the date: August 26-27 2023!

Miigwech for reading the biboon/winter edition of the Mzinigan. As ever, please contact Ben at benc@ramafirstnation.ca with any comments or questions regarding the mzinigan.

The sugar shack at Maple Avenue

The sugar shack at Maple Avenue

As part of the Crown’s Duty to Consult, Rama First Nation is regularly engaged with a wide range of proponents, developers, and municipalities. This means that a couple of staff have a neverending cycle of reports to review to ensure that our territory is being protected, or at least, not needlessly destroyed.

There are a couple of consultations which you may have heard of, and they will have major ecological and economical impacts on our region for years to come.

The first project is the Bradford Bypass. Essentially, the Bypass is a 16.2km highway propsed to connect Highway 400 to Highway 404. Ontario and the MTO (Ministry of Transportation) are developing the highway in order to ease traffic congestion, especially with forecasted population growth rates in the province.

Another major consultation project we’re working on is the Innisfil Orbit. The Orbit is a hugely ambitious project. Innisfil was awarded the opportunity to build a GO train station, connecting Innisfil to the GTA via rail. Centered around the GO station will be the “Orbit”, a large-scale development of residential and commercial buildings. Innisfil was granted an MZO (Ministerial Zoning Order) for the project, which essentially removes many checks and balances on developers in order to expedite development.

The Orbit could potentially be home to 150,000 people. Innisfil currently has a population of approximately 40,000 and many of of those calling it home are long-time, rural residents. This is a major shift for Innisfil and the area in general. 150,000 people means an intense strain on infrastructure, especially water and wastewater services. Furthermore, such a development will drastically changed local eco-systems. Due to the proximity to Lake Simcoe, and by extension our (Chippewa Tri-Council) traditional hunting and harvesting territories, we’re concerned.

There are significant environmental concerns with the Bypass. Most notably, the Bypass crosses over the Holland River and the through the surrounding wetlands. There are archaeological sites scattered along the proposed Bypass route as well. Thus, the Williams Treaties First Nations are involved in the consultation process, with Georgina Island the designated lead, in order to ensure development is happening in a good way. With the Ford government attempting to gut environmental protections through Bill 23, we as First Nations find ourselves as one of the last lines of defence for the environment. It is our duty as Anishinaabe to look after Mother Earth as best as we can, and consultation work is an extension of that responsibility.

The Bradford Bypass is still in the reports and assessments phase, with preliminary design expected in 2023. Visit the Bradford Bypass website for more information: www.bradfordbypass.ca

We are ensuring the developer, Vaughan-based Cortel Group, are consulting with us properly and providing all requested environmental and archaeological reports. We are not anti-development, but we must ensure that development doesn’t harm the next seven generations’ ability to hunt, harvest, and survive.

At the moment, planning is very much in the early stages. More PICs (Public Information Centres) will be planned shortly, and this is an opportunity to learn more as well as contribute your thoughts or concerns regarding the Orbit. This is a huge and long-term project, in which there may be employment opportunities for our members. Please visit www.innisfil.ca/en/building-and-development/orbit.aspx for more information.

Here we see a list of families who were present for the distribution of presents at Holland Landing, October 1818.

“Presents” were essential goods, given out by the Crown. The annual “distribution of presents”, which normally took place in Manitoulin or Holland Landing throughout history, was the Crown’s interpretation of traditional gift-giving. As the Crown attempted to understand Indigenous customs and protocol, they learned to utilize our ways to further their own goals. For example, for a long time, our ancestors were given guns and ammunition at gift-giving. However, the Crown grew wary of arming our ancestors in case of rebellion or worse, taking up arms for gchi-mookmaan (“big knife” aka America). Thus, they stopped handing out guns and ammunition, which were regularly used

for hunting, in order to alleviate their worries about safety and security.

Although the old script in the documents may be difficult to read, it contains some fascinating information. From left to right, we see the family name; the family clan (listed under “tribe”); and then how many men, women, boys, girls and total household members are present. Clans represented were catfish, pike, otter, caribou, bark, oak, crane, hawk, and even peacock. Some of the names are still found in our area today and of course we can recognize the clans too.

This document was originally shared with Rama First Nation by researcher Laurie Leclair. Gchi miigwech to Laurie for finding and sharing this important piece of our history.

Chief Yellowhead (Musquakie) was one of Rama First Nation’s most important and notable Chiefs of the colonial history period. Musquakie lived from approximately 1769-1864. The name Musquakie is presumed to be a derivative of msko aki, meaning, “red earth”. One can only guess where Musquakie’s name comes from, but one of the most likely theories is the reference to his hunting grounds of Muskoka and its pink Canadian Shield rock.

The name “Yellowhead” also inspires wonder. Yellowhead can be translated as ozaawindib in Anishinaabemowin, and there are other ozaawindib and Yellowhead names found in historical figures and places across Anishinaabe territory. Musquakie too finds namesakes in meskwaki, also known as the Fox people, who called several northern United States regions their territory. The Meskwaki referred to themselves as the “red earth” people, which was said to be a reference to their creation story in which they were created out of red clay. Thus, the names of our most notable Chief have many potential origins, of which we will likely never be sure is the correct one.

Musquakie’s father was also named Chief Yellowhead, and there is sometimes some confusion between the two Chiefs. Yellowhead Senior was Chief until shortly after the War of 1812. During the War of 1812, the older Chief Yellowhead suffered a serious injury to his eye, apparently losing vision after being shot with a musket. He passed soon after the War of 1812. Per his late father’s instructions, Musquakie was lifted as principal Chief in 1817.

Musquakie led Rama through its formative years. After returning from the War of 1812, Musquakie developed an impressive reputation amongst both his own people as well as the colonial government and religious leaders. Not only a fierce and renowned warrior, as shown in the War of 1812, Musquakie was often referred to as a great orator and diplomat. Indeed, early colonial writings and correspondence often praise Musquakie for his ability as a leader.

Chief Yellowhead found himself as a leader in a time of complete turmoil and chaos. For our ancestors and Yellowhead, his time as Chief spanned during arguably the most transformative time in our known history. Up until the War of 1812, relations with settlers and colonial government had been at least decent; there were wars which were fueled by colonial influence of course, but there was reciprocity and respect. The conclusion of the War of 1812, which solidified British rule of what became Canada, brought with it a change in relationship between our ancestors and the colonial government.

The nation-to-nation relationship was over. Instead, the Crown imposed a paternalistic rule in which Yellowhead

and our ancestors were obstacles in the way of colonization and development of what became Canada. Treaties, once a way to solidify equally-beneficial agreements and peace through wampum and gifts, became little more than tools of land theft. Treaties 16 and 18, signed in 1815 and 1818 respectively (by Yellowhead and others Chiefs) resulted in over 2,500,000 acres of territory allegedly surrendered to the Crown. Without territory, equal relationship, or leverage (in the form of military support), Yellowhead and our ancestors entered a difficult period of our history.

The first example was when Yellowhead and those he led were relocated from their vast territory to the Coldwater Narrows Reserve around 1830. Called the “Coldwater Experiment”, the reserve was a systematic attempt to assimilate our ancestors in Euro-Canadian culture. The reserve was also the very first reserve in North America. Yellowhead and our ancestors were expected to become Christians, and take up European-influenced agriculture and lifestyle. The expectation was that Yellowhead and our ancestors were to give up their ancient hunter-gatherer lifestyle, abandon spiritual and cultural practices, and be more like the European immigrants.

Yellowhead and our ancestors resisted these efforts. Some people, Yellowhead included, did convert to Christianity. Nonetheless, despite some conversion to Christianity by the community, our ancestors remained Anishinaabe. They continued to hunt and harvest; continued to practice culture and ceremony; and continued to speak Anishinaabemowin. Angry at the lack of complete assimilation, as well as being pressured for land by settlers, the government coerced an illegal surrender of the Coldwater Reserve from Yellowhead (as well as other Chiefs of the Chippewas of Lakes Simcoe and Huron). As a result, in 1836 our ancestors were essentially landless, and Yellowhead had to find a new home for his community.

This led to a new period of transition for our ancestors and ultimately the beginning of Rama First Nation as we know it. As part of the Coldwater surrender, the Crown had promised 4,000 acres of new lands. In the late 1830s and early 1840s, Indian Affairs staff and Yellowhead sought out territory to purchase and re-locate to. Ultimately, Indian Affairs and Yellowhead settled on the abandoned farmland on the east side of Lake Couchiching. The majority of it was owned by War of 1812 veterans (obtained by land grants), and it had not been developed. The land was rocky and rough, with poor soils and as such, was left to sit idle by its owners.

Yellowhead directed Indian Affairs to allocate whatever they could to his community. In a rare occurrence, annuities and Yellowhead and other Rama men’s War of

1812 pensions were used to pay for the land, essentially meaning our ancestors purchased our reserve. Land was purchased in blocks of whatever was available and affordable, hence the checkerboard nature of the reserve which still exists today. The 4,000 promised acres did not materialize and we were left with a measly 2,300 acres; Indian Affairs purchased the land for more than what it was worth and the remainder of the 4,000 acres could not be afforded. Regardless, Yellowhead had secured a home for his community, and our ancestors dutifully began working the land and building their homes.

Around the same time Yellowhead was buying our reserve for the community, he was renewing peace with historical enemies, the Haudenosaunee. A meeting between the Anishinaabeg and Haundeosaunee took place in 1840, in which a historical wampum belt (which Anishinaabe historian Alan Corbiere refers to as the Eternal Council Fire Belt) was recalled. The Eternal Council Fire belt was said to “have a row of White Wampum in the centre, running from one end to the other, and the representations of wigwams every now and then, and a large round Wampum tied nearly the middle of the belt, with a representation of the sun in the centre”. Yellowhead spoke to the significance of the belt, and fortunately, his words were transcribed:

“this Belt was given by the Nahdooways (Haudenosaunee) to the Ojibways (Anishinaabeg) many years ago – about the time the French first came to this country. That the great Council took place at Lake Superior –that the Nahdooways made the road or path and pointed out the different council fires which were to be kept lighted.

The first marks on the Wampum represented that a council fire should be kept burning at Sault St. Marie. The 2nd mark represented the Council fire at Manitoulin Island, where a beautiful whitefish was placed, who should watch the fire as long as the world stood.

The 3rd mark represents the Council fire placed on an island opposite Penetanguishine Bay, on which was placed a beaver to watch the fire.

The 4th mark represents the Council fire lighted up at the Narrows of Lake Couchiching at which place was put a white reindeer. To him, the reindeer was committed the keeping of this Wampum talk. At this place, our fathers hung up the sun, and said that the sun should be a witness to all what had been done and that when any of their descendants saw the sun, they might remember the acts of their forefathers. At the Narrows our fathers placed a dish with ladles around it, and

a ladle for the Six Nations, who said to the Ojibways that the dish or bowl should never be emptied, but he (Yellowhead) was sorry to say that it had already been emptied, not by the Six Nations on the Grand River, but by the Caucanawaugas residing near Montreal.

The 5th mark represents the Council fire which was placed at this River Credit where a beautiful white headed eagle was placed upon a very tall pine tree, in order to watch the Council fires and see if any ill winds blew upon the smoke of the Council fires. A dish was also placed at the Credit. That the right of hunting on the north side of the lake was secured to the Ojibways, and that the Six Nations were not to hunt here only when they come to smoke the pipe of peace with their Ojibway brethren. The path on the Wampum went from the Credit over to the other side of the lake, the country of the Six Nations.

Thus ended the talk of Yellowhead and his Wampum”

Chief Yellowhead’s legacy is immense and perhaps unmatched. He fought in the War of 1812, and immediately after became a Chief of our community. He resisted a new era of colonial-tribal relations as best as he could, most notably in an 1846 meeting when he initially rejected the concept of industrial schools (residential schools) and refused to relocate the community to Manitoulin Island. He found and purchased new lands for our ancestors to relocate to. He was a key signatory on several treaties and notably, the orator tasked with renewing the peace between Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabeg. His name is remembered as the place that many spends millions upon millions to live in: Muskoka. The imagery of his wampum renewal speech is seen in the Rama First Nation logo (designed by Theresa Desormeaux). Indeed, evidence of Yellowhead’s legacy is easy to find.

Yellowhead was known and sometimes referred to as Chief of “all the Chippewas”. How far his reach and leadership spanned is difficult to know, but without doubt he was instrumental in the formation of Rama and is arguably the most important figure in our documented history.

A replica of the wampum belt as described by Chief Yellowhead, made by Brian Charles

We know now that our ancestors certainly lived there immediately before 1830, as there is historical reference to moving from “Yellowhead’s Island” to Orillia in that time frame. As to when the island first became occupied, it is impossible to say. Mnjikaning (the place of the fish fence), only a short paddle away, has been in place for over 5,000 years. With Chief Island being in the middle of a well-travelled lake and part of a vital route north into hunting territories, it is safe to say people have lived or camped there for millenia.

The island at one point had a church/school, and was staffed by a missionary. There would have also been wiigwaaman (homes) on the island too.

There is reference to Chief Island in the 1851 Census. The text states,

“The Indians cultivate small patches of land on an island in Lake Couchiching upon which they raised up little Indian corn and potatoes...”

The soils of Chief Island supported small gardens. Although the majority of our community had moved to our current village in Rama between 1838-1848, Chief Island was still regularly used and visited. More recently, there is living memory of the island being home to many pigs!

There has been a lot of focus on Chief Island in the past few years in regards to it being accessed without permission by non-community members. This has been particularly concerning due to the island being considered sacred by many as it contains many gravesites.

In the early 1920s, Indigenous remains found in the ground at Mary Street in Orillia were taken to Chief Island and reinterred.

“Rama Council resolved to give these people a final resting place on Chief’s Island. In the recent past, the community had fought vehemently for privacy and control over the maintenance of this traditional burial ground, frankly telling outsiders who complained of its unkempt state to mind their own business. This was a sacred site not a public park. In fact, John C Simcoe and Norman Snache dug the grave themselves... at least 36 ancestors

found a sacred and respectful resting place”. (Laurie Leclair , http://anishinabeknews.ca/2018/10/31/chiefs island grave story/story/)

Historically, there were many inquiries regarding potentially purchasing Chief Island. Indian Affairs were questioned whether it would be surrendered by ambitious settlers. Time and time again, Rama refused, pledging that the island would never be surrendered. The burials and importance of the island were always known to our ancestors.

There are 14 gravestones on the island:

-Maggie Sandy, June 1879 - October 30, 1903

-Eva Frances York, Born May 6, 1908

-Betsy L. Myrtle, April 10, 1901 - December 12, 1909

- “B.L.M.Y.”

-Arthur Shilling, 1900 - October 8, 1920

-Chief John Kenice, 1837 - May 28, 1902

-William Jacobs, 1843 - February 19, 1859

-Albert Nelson Snache, July 11, 1906 - October 7, 1927

-Phoebe Ann Joe, January 20, 1860 - September 11, 1906 - and two gravestones with illegible names and dates.

However, there are many more ancestors buried on the island but not identified with a grave markers. Historical documents such as death certificates report many burials occuring at Chief Island, but there are no gravemarkers for them.

Chief and Council recognized our ancestors’ resting place with a beautiful monument installed in the summer of 2019. In addition, the existing gravestones, many of which were well over 100 years old and in rough shape, were completely remade with exact replicas. The originals were later crushed and taken back to the island to be put back on the earth.

Throughout Rama First Nation’s history, Chief Island has played an important role. Whether it be a burial site, village site, or spot of refuge, it has always been waiting for us in Lake Couchiching. Chief Island has always

The monument found on Chief Island, acknowledging the many unknown burials of our ancestors.

been part of the traditional territories of the Chippewas of Lake Simcoe and Huron, as we were referred to by settlers and the government. The Chippewas of Lake Simcoe and Huron became three separate First Nations after the loss of the Coldwater Narrows Reserve in 1836, known today as: Chippewas of Rama First Nation, Chippewas of Beausoleil First Nation and the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation. To this day, we continue to have close ties and are collectively called the Chippewa Tri-Council.

In 1873, Canada enacted ‘An Act for the Better Protection of Navigable Streams and Rivers’, S.C. 1873. Prior to this time, the right to navigate waters was governed by the British common law which established that all people have the right to navigate tidal waters (i.e. seas and oceans). In Canada, however, the history of Indigenous peoples’ use of in-land rivers and lakes was significant motivation to protect this right to navigate which had not previously been an issue in Britain. Since navigation is the responsibility of the federal government, Canada implemented the Act to restrict people from polluting, blocking, or otherwise altering navigable waters in Canada unless the project has been reviewed by government officials. In many ways, this was a protection of Indigenous ways of life.

However, as time went by, we know that Canada began to see Indigenous peoples as limiting the ability of settlers to establish themselves on some of the most fertile and sought-after lands in Canada. As such, Canada did what it could to purchase as many of the lands as possible, restricting “Indians” to reserve lands set aside for them. For Rama First Nation, a significant shift in harvesting rights occurred with the signing of the Williams Treaties in 1923, treaties attempting to clarify earlier Pre-Confederation treaties. Although many members of Rama had undertaken farming practices at Coldwater, they continued to have hunting camps and pursued fishing as well.

The Williams Treaties took away harvesting rights including fishing in the waters. The motivation for this was likely economic: Canada and Ontario could then grant paid licenses, control commercial fishing, all hunting, and the waters, as other countries do. It was also used as a way to encourage Indigenous peoples across Canada to “become civilized” by establishing farms and devoting themselves to the settler’s religions.

From this came a great deal of hardship for Rama and other Williams Treaties First Nations. Often, reserves were located on lands that were not easily farmed, and

so the result was a poor harvest and hungry people. Fishing kept our people from starving. Eventually, Ontario granted permission to Williams Treaties First Nations to fish up to 100 yards from the shoreline. It is unknown when this policy was put into place, but it can be found referenced as early as 1991. Many believe that we own that 100 yards into the water, however, according to Canada and Ontario, we were only granted the right to harvest in this water for personal use.

Throughout history, many First Nations from all over traveled to the Mnjikaning fish weirs every year to fish, trade and to meet on important issues. The weirs at the Narrows were neutral territory and a significant aspect of our social structure. It is clear that these waters have always been an important part of our lives.

In the face of community struggle, a plan was discussed in 1915 to develop the island to help our people survive economically, but the idea was eventually discarded. Chief Island continues to be an important place for our people. In recent years, there have been many improvements made to the island’s cemetery. The main section of the island has trails and a few cabins for Rama members to use. These improvements were made to allow some human activity on the island, partially to deter cormorants from nesting, but primarily to make use of valued territory in the community. Land-based programming is planned to provide teachings and ceremony to youth in the community once the pandemic has passed.

Throughout the process of development on the Island, when something is done to repair or improve it, a ceremony is held to ask permission of our ancestors and to explain what we are doing. This practice goes back as long as we have had care of the island. Chief Island has played a prominent role in our history and the history of the Huron-Wendat. Many of our people carry with them the stories handed down through the generations about Chief Island and how important this sacred place is to our people.

For more information on Chief Island, including regarding visiting the island or staying at one of the cabins on it, please contact Rama First Nation.

Prior to efforts by Rama First Nation, Chief Island was overrun by boats and weekend parties. Education and restrictive measures (including a bylaw) have helped improve the situation.

Prior to efforts by Rama First Nation, Chief Island was overrun by boats and weekend parties. Education and restrictive measures (including a bylaw) have helped improve the situation.

Clockwise from above: OjibwayBayMarina,circa1970’s,with RamaRoad and Ramahouses in the background;The SilverNightingale Band dancers leading a parade in Orillia(date & event unknown) - the dressworn bythewoman on the right is currentlyon displayat OurHeritage Place; agroup of guides from Ramain Muskokashowing off theirhaul forthe day; HenryBird Steinhauer,born around 1818,left Ramaas ayoung man to attend universityto studytheologyand religion, and ended upworking as aMethodist missionary.He settled outwest.Ramahas a familial and historical connection to his descendants,aswell as Henryhimself.He died on December 29th, 1884.

The Department of Indian Affairs (now known as Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada) Annual Reports and memos are an important yet somewhat controversial part of our history. They are often the only first-hand account of our community’s documented history. However, they are a biased insight into our ancestors’ day-to-day lives, often laden with racism and a sense of ethnic and cultural superiority on behalf of the authors (who were Indian Affairs bureaucrats).

Our ancestors’ “progress” towards “civilization”, uptake of religion, and use of alcohol (or lack thereof) was routinely commented upon in the reports. Indian Affairs staff remarked on agricultural work: how many bushels of wheat the community grew, what farm equipment was present, and how many oxen and other livestock were kept. Ultimately, the Indian Affairs reports and memos were essentially report cards on assimilation, provided for Canada and the Crown by their dutiful bureaucrats.

We and surely our ancestors knew that we didn’t really need any instruction on farming (we’d been farming for millenia); that we had spiritual and cultural practices already; and that there were already vast, complex civilizations all across Turtle Island. But as we know now, Canada and Indian Affairs simply didn’t agree with our ways of life. As a result, assimilation and genocide was attempted. The fact that we’re still here, that our language exists, and that our culture, stories, and ceremonies survive is a testament to the fact that assimilation and genocide were only attempts...and not a success.

Nonetheless, if we can read Indian Affairs reports critically and with an understanding that they were a measurement of Canada and the Crown’s efforts of assimilation, we can learn a lot about our history. (Note - the language is unchanged - there’s some outdated terms and the communication style will seem quite strange to those unfamiliar with it).

This correspondence was recently found and it shares some interesting information about the history of Rama.

The Chippewas of Lakes Huron and Simcoe, in

three bands under Chiefs Yellowhead, Aissance, and Snake (Bigwin) were in 1830, settled by the Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne, on a tract of land between Coldwater and the Narrows under the supervision of Capt. T.G. Anderson. Gerald Alley was appointed by the Government a a teacher and farming instructor for the Indians in 1830 and commenced farming on 50 acres of land at the Narrows in 1831.

The Indians moved from Yellowhead’s Island to the Narrows in the fall of 1830 and during the next ten years houses and a school were built for them there. This formed what was known as the Indian Village. In December, Mr. Law who was the Methodist teacher on the Island moved to the Narrows and taught school in a bark wigwam.

There seems to have been continued friction between the Methodist Missionary and Mr. Law on the one hand, and Superintendent T.G. Law and Mr. Alley on the other. The Methodists at this time seem to have drawn their mission workers from the Society at Rochester and they did not always work in harmony with the local British Officials. There was the same trouble at Coldwater.

In the spring of 1831 the Rev. Mr. Allison applied for a lease or grant of land on which to build a two story log house 34 by 28 feet for the family of the Methodist Missionary and there was some dispute over the selection of a site for it.

In the fall of 1831 the Methodist Missionary seems to have been the Rev. Gilbert Miller. He urged the completion of the school building and said he was daily expecting the arrival of two teachers.

The Indian houses were not finished before the white immigrants began to settle in the village and on the 22nd of July 1832, when Cholera broke out among them, Gerald Alley reported that there were 94 of these people encamped upon the common fronting the village and 30 other whites in the vicinity. The whites suffered more than the Indians.

In this epidemic, Dr. Wm. B. Algeo, who was appointed in 1831 at fifty pounds a year to attend the Chippewas, had the voluntary assistance of Dr.

Paul Darling, a licentiate of the Royal College Surgeons of Edinburgh who had just come to Canada with his father and mother and two brothers to take up land in this district. The father had died in Montreal on their way.

On resignation of Dr. Algeo on the 4th of July, 1833, Dr. Darling succeeded him as medical attendant to the Indians and in September 1836 he went to Manitoulin Island in a similar capacity and was succeeded by Dr. Chas. J. Robinson as medical attendant for the Chippewas.

In 1834 the Indians built a wharf and a store at the Narrows. In this year also Gerald Alley, the farming instructor, resigned and was succeded by John Fletcher. Mr. Alley applied for a license of occupation for 3 acres of land in front of the Indian Village at the Narrows on which to build an Inn and had plans prepared for the same. I don’t know, however, whether this was ever built for the plan shows a bar room and on the 15th of January 1835 there was a petition against the sale of liquor at the Narrows.

The Indian Village was surveyed by Mr. Hawkins in 1834 and the reserve at the Narrows was surveyed by Jacob Gill in May 1835.

A mill site of 20 acres on the North River, part of Lot No.2 in the 1st Concession of the Northern division of Orillia, was purchased for the Indians from Mr. Wm. Hume at a cost of 200 Halifax currency and the deed is dated the 5th of April 1836.

In 1836 the Chippewas surrendered their land between Coldwater and the Narrows and a new reserve of 1621 acres was purchased, with their funds for the use of Yellowhead and his band of 184 Indians at Rama. Chief Aissance and his band numbering 232 went to Beausoleil Island and Chief Snake (Bigwin) and his following of 109 Indians settled at Snake Island.

Yellowhead and his band moved to Rama in 1838 where houses were built for them.

In 1839 the White settlers petitioned to have the Indian Village at the Narrows surveyed and sold into town lots. Samuel Richardson made the survey and the “Plan of Townplot” on Lots 7 & 8 in 5th Concession of Southern Orillia is dated January 1840.

On the 17th of December 1836 Mr. Andrew Moffat, a teacher in the Mission School, applied to purchase Lot 7, Concession 5 Orillia but I have found no reference to Miss Manwaring in the Archives. The accompanying letters may be of interest.

G. M. Matheson Registrar16th May 1932

1840 Survey of Southern Orillia - the “Indian Village” is seen between Misssissagua and Cold-Water Street to the left of the survey (the rectangular shapes are buildings/homes). 2370-CLSR TOWN PLOT ON L.7 & 8,CON.5 OF SOUTHERN ORILLIA

Yellowhead’s Island Sept. 15th 1830

(a letter from Yellowhead to Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne)

Father, Seven young men belonging to this tribe and perhaps some of the Snake tribe will settle on the portage road from this to Majedusk next spring. As for us old men, we intend to settle at the village you are building for us and end our days there; our children will be kept at school. Father, We are always grateful to receive your instructions and ready to obey them, but it is getting so late in the season, we shall not be able to clear much this fall, but early next spring we will commence as you desired us. Father, We are poor yet and have no mockasins, we wish to hunt this fall and get some deer skins against the cold weather.

Father, We are glad of the money you sent us for our work this season, and we wish to know when you can pay us the remainder. We shall be going to our huntings in about two weeks and should be glad of the money before we go and if you can accomodate us we should be glad of some small change in such as three, two, and one dollar bills with some 2/6 pieces. We are your children.

William Yellowhead x Bigwin x Watumbone Yongs x Isaac Johns x Big Shilling x

Indian Department, Coldwater, 28 December 1830

Sir: A short time since I had the honour to report to you that Mr. Alley had commenced Keeping School at the Narrows; at this time the Indians were encamped about their New Village and the Methodist Teachers had not come away from Yellow Head’s Island, however as soon as Mr. Law the teacher could come over he did, and, in a bark wigwam, commenced Keeping School, and the Indian children apparently contrary to their wishes, left Mr. Alley who is in a subsequent conversation with Mr. Law received almost unqualified abuse.

On the 24th inst. I considered it necessary to know from Yellow Head whether he intended that any of their children should attend our school or not, and in presence of several other Indians I asked him the simple question, observing that I did not make use of persuasive language but merely wished to have their decision, for if they did not intend to send them to be taught by the Master their Father had sent to them for that purpose the would go to Coldwater and Keep School there. The Indians seemed quite satisfied that it would be the best plan to send part of their children to our school, still there appeared a delicacy or fear to give a positive and immediate answer, I said there was no secret in the queston I had asked them and as I wished for a deliberate reply, it would be better for them to wait until monday and in the meantime if they concluded to allow part of their boys and girls to attend Mr. Alley, it might be well, as we did not wish to have the choice of his scholars to consult Mr. Law as to which ones he would recommend giving up, and that it was not their Father’s wish in any wise to interfere with their

Yellowhead’s house, circa 1830’s above and below in 1847. In the image below, St. James’ Church is seen in the background. Image above from A History of Simcoe County, byAndrew F. Hunter; unknown source for image belowTeachers at this station further than to assist in bringing the children forward as fast as possible.

On Monday, being the day appointed to receive their answer, Mr. Alley went to where the Indians were in consultation with the Methodist Minister and the Teacher; On Mr. Alley’s explaining the object of his visit poor Yellow Head was so confounded from the desire of displeasing Mr. Allison (the minister) that the perspiration rolled from his face and finally he could not say anything satisfactory on one side or the other, and put off his answer until he could see his father at York.

In the meantime, Mr. Alley was loaded with gross abuse by the Minister with which he appears to have submitted, with patience and great forbearance, but as it appears highly necessary that this business, as well as Mr. Lewis’ affairs should be more fully explained by letter, I have requested Mr. Alley to be the brain of this and other dispatches for His Excellency’s information and beg permission to refer to him for further particulars.

I have the honour to be Sir, Your Most Obedient and Humble Servant

T. G. AndersonIndian Department, Coldwater, 19 March, 1831

To Colonel J. Givens

Sir: In compliance with the direction received from His Excellency, Yellow Head pointed out a spot of ground for the Methodists to build on but they have changed their plan and insist upon building in another place and occupying a large parcel of land which the Indians do not at all approve of, and desire me to request that His Excellency will be pleased to name the spot and quantity allowed to them.

Indian Department, Coldwater, 7 April 1831

To Colonel J. Givins

Sir: I have the honour to report for you for the information of His Excellency the Lt. Governor that in obedience to that part of Asst. Commr. Genl. Foote letter of the 30th Ult. relative to the Methodist buildings, I have seen Mr. Allison the preacher on the subject who informs me his object is to build a two story log house 34 by 28 feet intended for dwelling for the members of the Missionary family. The spot which Mr. Allison would prefer is immediately adjoining the south end of Yellowhead’s village and he also wishes, in front of the building, to have a garden and potato field extending along Shingle Bay Road and down to Lake Simcoe containing from three to ten acres. Mr. Allison wishes to be informed whether he or the society to which he belongs, will receive a lease or other grant of the ground which they may be allowed to occupy.

The Chief Yellowhead being from home on a hunting excursion, I could not consult him on this subject, but have no doubt it should meet His Excellency’s approbation he will be satisfied with it.

Mr. Allison has all the timber prepared for the house and begs that he may be favoured with an early answer, in order that he may proceed with his building. The Methodist Minster (Mr. Currie) of Matchedash has also requested of me to beg His Excellency’s permission to occupy a piece of ground at Coldwater, for the same purpose as required by Mr. Allison at the Narrows.

I have the honour, Sir, to be Your Most Obdt. Hble. Servt.

Unfortunately, the chain of correspondence trails off there, at least in terms of digitized and accessible proof. There isn’t a steady stream of letters culminating in the result which we know of today.

The correspondence in the previous pages shows how many moving parts were involved in what was a chaotic time period. Quite often when we look at history, it is easy to forget the day-by-day life of those involved, and instead we focus on major events rather than the many small decisions that lead up to them. Different individuals and groups had varying goals for Orillia and our ancestors were heavily involved. Settlers wanted land, the church wanted schools and churches (as well as people to put on the pews) and the Indian Department wanted our ancestors centralized, dormant, and manageable.

The result was the beginning of the most frantic time in our community’s history. Our ancestors moved village sites four times in ten years. The Methodist and Anglican churches were constantly fighting about who was better suited to teach religion to our ancestors. The Indian Department was in the middle trying to control everything. And amidst it all, our ancestors were trying to make the best of a difficult situation, in which they had the least control but were the most impacted.

There was an Indian Council House as well as a home for Chief Yellowhead built by the government around 1831. The buildings were located in what today is downtown Orillia (where St. James Church stands, across from TD Bank). The government also built homes and a school. The buildings were a part of the Coldwater Narrows reserve and were a key part in convincing our ancestors to relocate to the reserve. But fighting between Methodist and Anglican sects complicated matters for the Crown. Both religions wanted to utilize the buildings to teach their versions of religion. Around the time that our ancestors were being convinced to relocate to the reserve, Orillia was starting to become a busy place of white settlement. Part of what ultimately led to the taking of the Coldwater Reserve by the Crown was petitioning by these settlers. The settlers wanted land and the religious groups wanted the buildings to utilize as the first places of worship in Orillia. Furthermore, the government felt that our ancestors were not “progressing” (i.e. resisting assimilation) as they wished.

In 1836 the Coldwater Reserve Narrows was allegedly surrendered. Beginning in around 1838, our

ancestors began moving to Rama township, where Chief Yellowhead had started to purchase plots of abandoned farmland. More details about these land purchases can be found in the Fall Our Heritage Place Mzinigan. In June 1852 and additional 20 acres of Orillia was surrendered by Chiefs Yellowhead, Nanigishkung, Bigwin, Young, Snake, Aissance, and two others (names are illegible on the surrender).

The Indian Village and the Coldwater Narrows Reserve were shortlived and shortsighted attempts at controlling and assimilating our ancestors. Through it all, our ancestors moved village sites 4 times in ten years. With a population of around 185, this would have been difficult. As Chief Aissance remarked at an 1846 Council meeting regarding moving to Manitoulin Island, “I have have already removed four times; and I am too old to move again”.

Chief Yellowhead’s home as well as the Indian Council house ultimately did become part of the church. The Anglican church began preaching in the old Council house and the minister lived in Yellowhead’s home. Eventually, the massive church called St. James Church was built in 1890 and still stands today.

Yellowhead’s connection to his former home remained. After his death around 1864, he was said to be buried on the property. There is a monument recognizing the burial of Yellowhead, somewhere, on the church property. Yellowhead, apparently a devout Christian, was said to have donated the property to the church. Whether that “donation” was a part of the larger Coldwater Narrows alleged surrender or something he personally worked out with the church requires additional research. Early indications and a lack of evidence of the fact suggests that no, Yellowhead did not personally donate his property to the church...but more updates will be provided once research is complete.

Above: Log Shanty on the Coldwater Road, Orillia Township, Ontario, Titus Hibbert Ware.

Source: Toronto Public Library

Below: “Indians and Canoe, Coldwater River, Coldwater, Ontario” , Titus Hibbert Ware

Source: Toronto Public Library

Above: Page 2 of the 1852 surrender of 20 acres of Orillia Township land. The Chiefs’ doodem (clan) marks indicate their approval of the surrender.

Source: Library & Archives Canada

Below and right: Early images of the Atherley Narrows, which has been a historic meeting and gathering space for millenia, as well as the site of our village throughout history. Mnjikaning, the place of the fish fence, was and in some places remains throughout the channel and in the marshy area on the Lake Couchchiching side. Images Source: Orillia Past and Present, Facebook

Above: A map of the Coldwater Narrows Reserve (within the red boundaries).

Above: A map of the Coldwater Narrows Reserve (within the red boundaries).

Miigwech for reading. next issue gtige-giizis / May 2023