Podium

Belmont Hill’s History and Social Sciences Magazine

An important note: All opinions and ideas expressed in The Podium are the personal opinions and convictions of featured student writers and are not necessarily the opinions of The Podium sta!, the Belmont Hill History Department, or the Belmont Hill School itself.

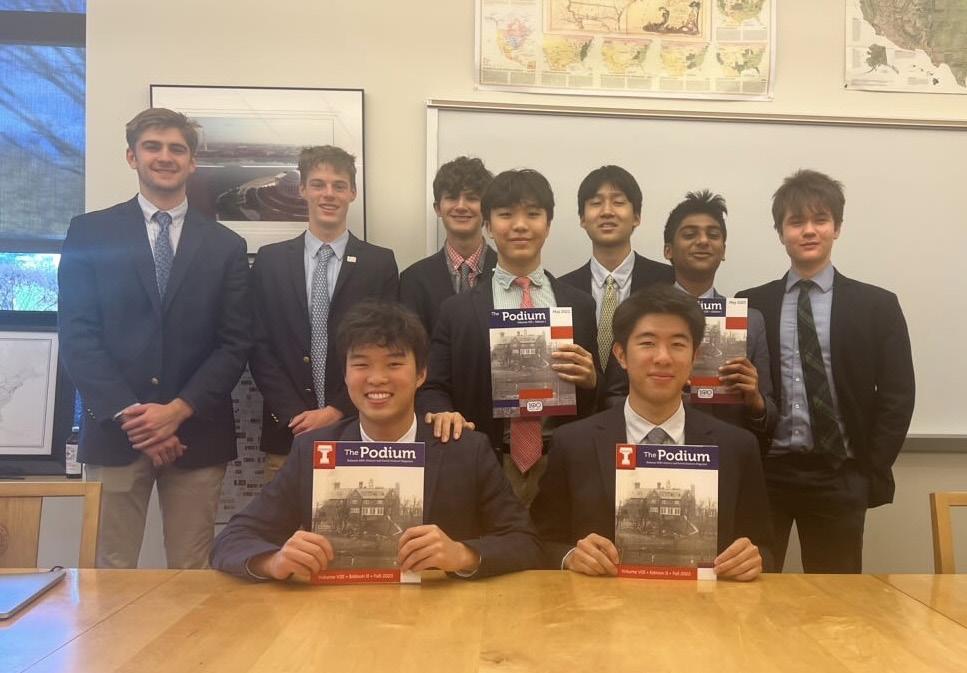

The Sta of Volume IX of The Podium Back Row, Left to Right: Ben Adams, Davis Woolbert, Mikey Furey, Jaiden Lee, Brandon Li, Suhas Kaniyar, Teo Rivera-Wills; Front Row: Wesley Zhu, Ernest Lai

Cover photo from BH Archives

Published by the Belmont Hill School 350

Printed by Belmont Printing Co.

Designed with Adobe InDesign and Adobe Photoshop

Letter from the Sta!

Dear Reader,

We are extremely excited to share Volume IX, Edition II of The Podium with you. For the seniors on the sta!, this will be the final edition published during their time at Belmont Hill. A total of thirteen fantastic student works are included in this issue, covering a dazzling array of topics in history, current events, and politics.

This edition opens with “History on the Hill”, in which Brandon Li ‘26 thoughtfully examines World War II through the Belmont Hill Panels. As always, The Podium received numerous outstanding student paper submissions for their annual op-ed competition. Belmont Hill students were asked about their views on ChatGPT as a grading tool, the necessity of the Electoral College, and whether or not the automobile industry should transition to electric vehicles. The three winners were Daniel Chen ‘26, Jack Ramanathan ‘26, and Rylan Dean ‘26, and we thank all the students who submitted op-eds.

Also included in this edition are three research papers nominated by the Belmont Hill History Department. Monaco Prize-winner James Keefe ‘25 begins by discussing the anti-slavery movements from the U.S. Catholic community during the Ante-Bellum and Civil War eras. Next, Will Days ‘27 examines the struggles of migrant workers in China and the hukou system of residential registration. Finally, Riley Marth ‘27 somberly reflects on the Rape of Nanjing and the lessons that can be learned from such a horrific event. We sincerely congratulate all these students who were selected for their outstanding work.

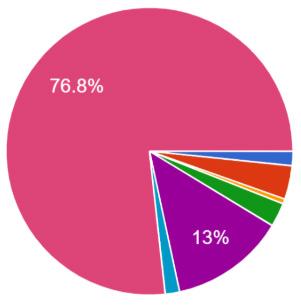

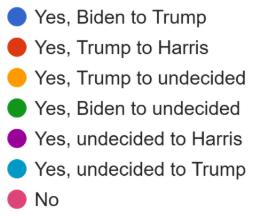

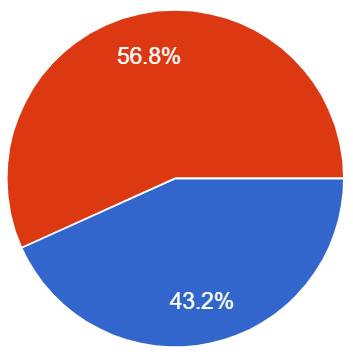

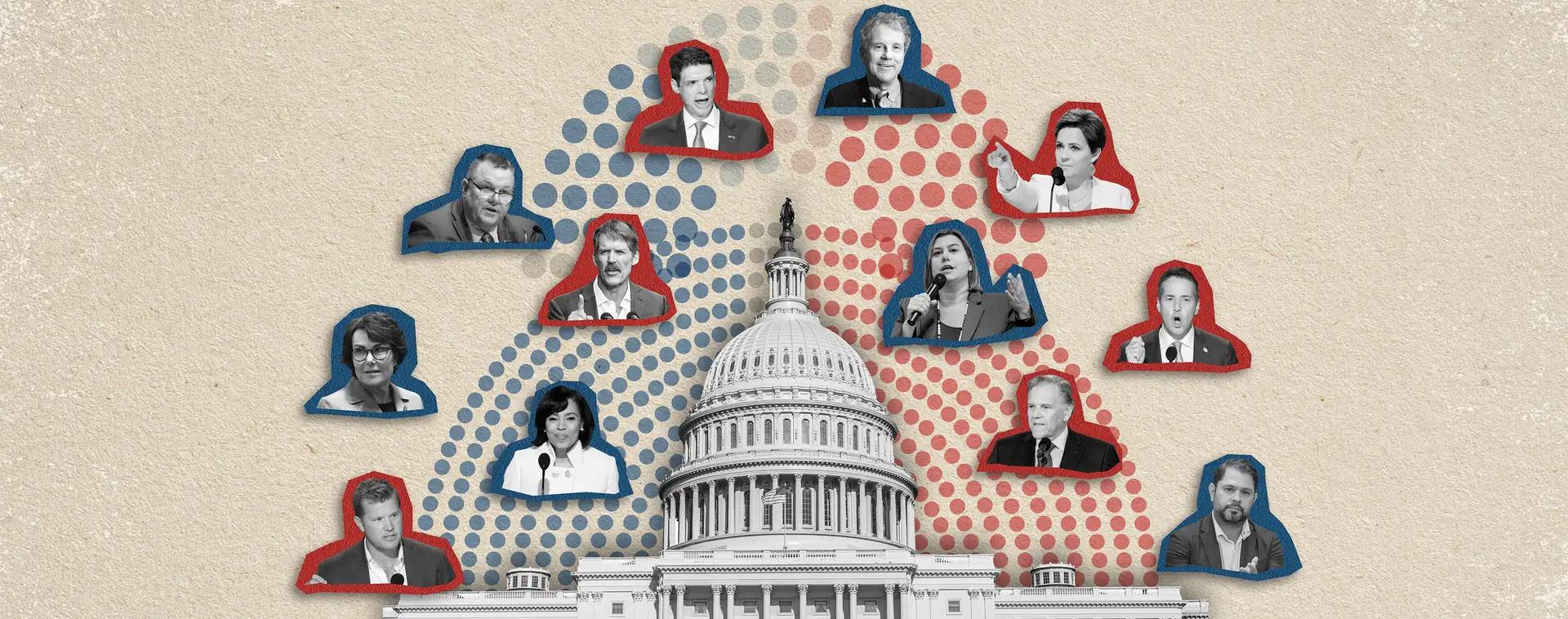

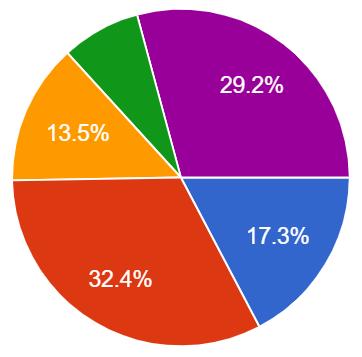

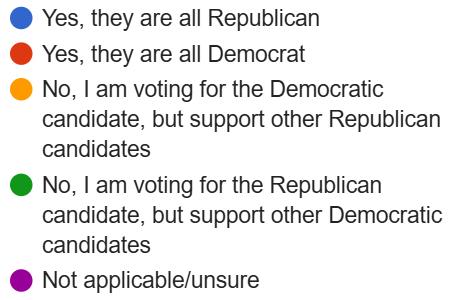

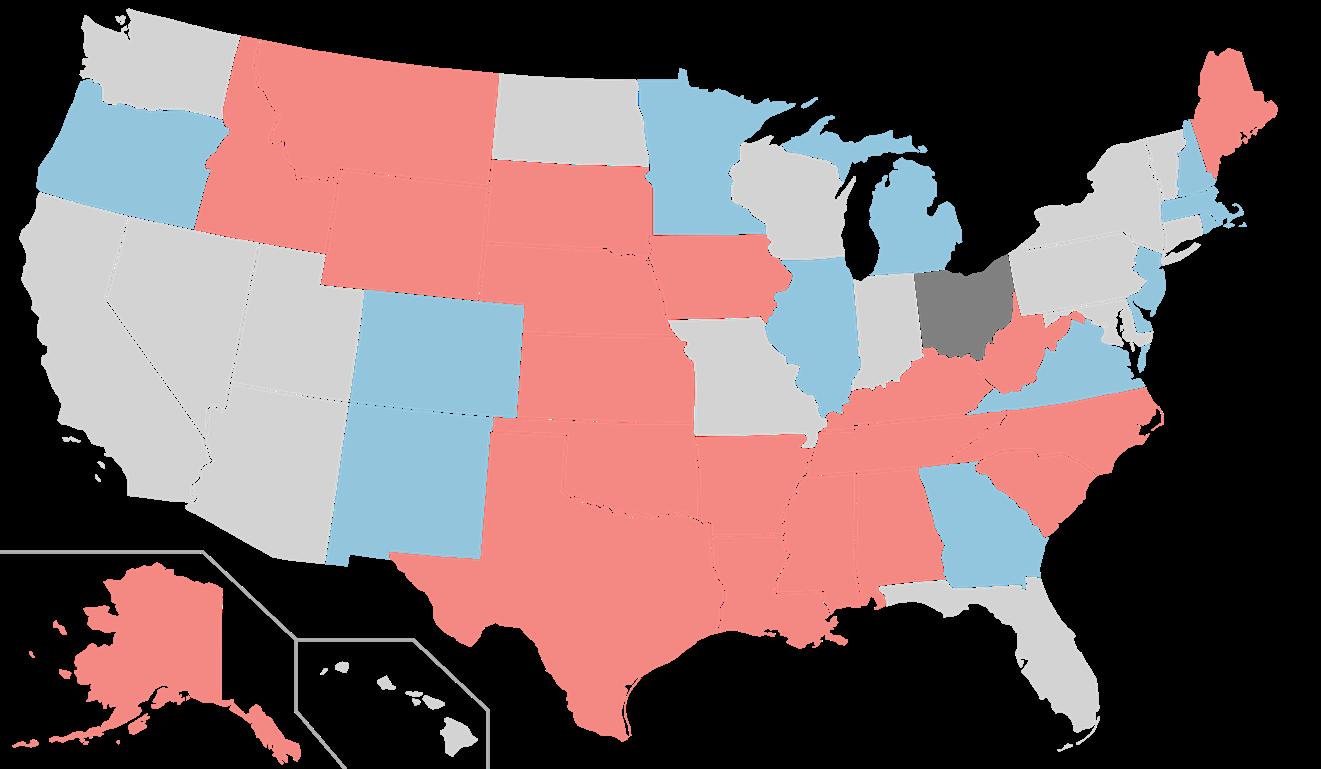

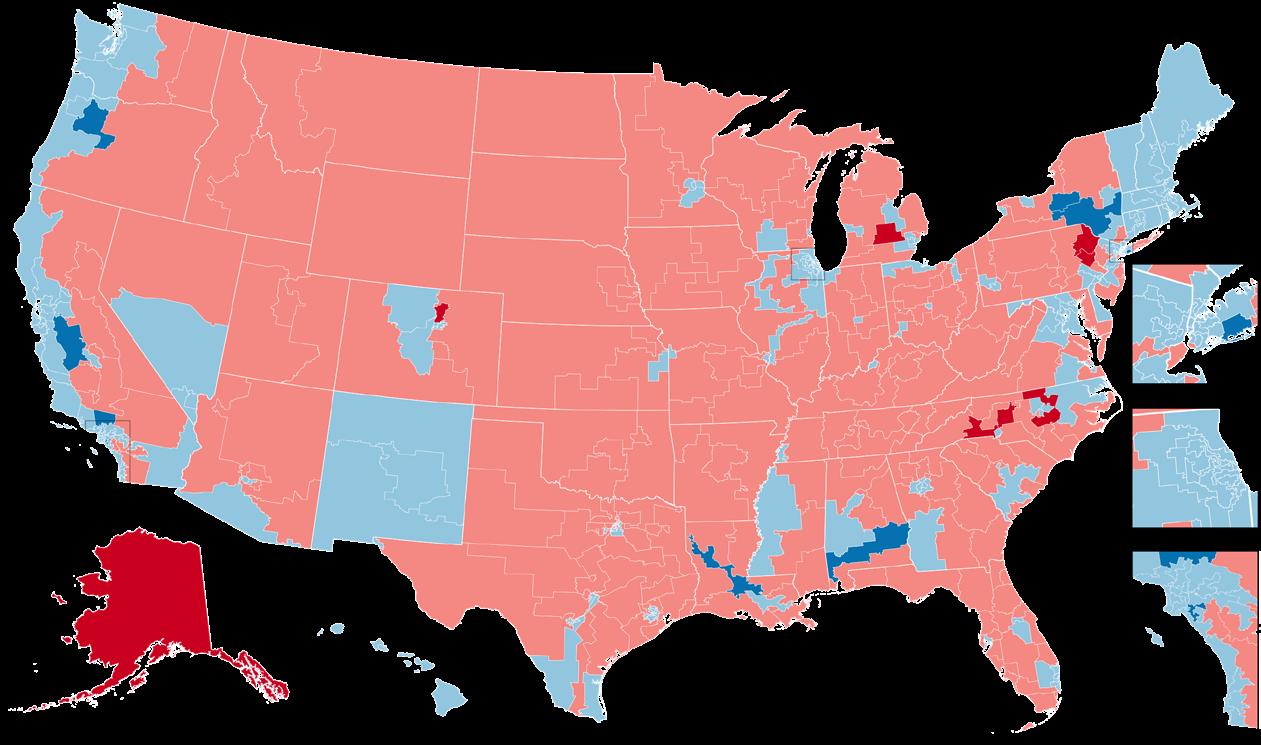

In addition to these papers, several sta! articles are included in this edition. Ben Adams ‘25 and Christopher McEvoy ‘25 surveyed the Belmont Hill community and its sentiments toward the 2024 presidential, Senate, and House elections. This issue closes with five miscellaneous essays, covering themes like the House and Senate races, politics in the Olympics, the legality of military occupation of the West Bank, student protests in Bangladesh, and Elon Musk’s impact on Trump’s campaign.

We would again like to thank everyone who submitted work to The Podium, and give a special thanks to Glenn Harvey, our faculty advisor. Thank you for picking up a copy of this edition of The Podium, and happy reading!

Ernest Lai ‘25, Wesley Zhu ‘25 | Editors-in-Chief

Mikey Furey ‘25, Davis Woolbert ‘25 | Executive Editors

Jaiden Lee ‘26, Brandon Li ‘26, Christopher McEvoy ‘26 | Associate Editors

Ben Adams ‘25, Bradford Adams ‘26, Lucien Davis ‘26, Suhas Kaniyar ‘27, Sam Leviton ‘27, Eli Norden ‘26, Henry Ramanathan ‘26, Teo Rivera-Wills ‘27 | Sta Writers

Mr. Harvey | Faculty Advisor

World War II Through the Belmont Hill Panels

Brandon Li ‘26

Ever since Belmont Hill was founded in 1923, the school has required graduating members of Form VI to carve a panel as part of their graduation requirement. Through these carvings, seniors often choose to reflect items or themes of significance to them. These panels are then hung up and displayed around the school for future observers, reminding them of our institution’s storied past and the unique individuality of the many men who were shaped by it.

Some seniors choose to illustrate sports, extracurriculars, or hobbies they participated in during their time at Belmont Hill; others portray some concept or life lesson they may have learned. However, many panels also provide fascinating accounts of the historical events taking place in America and around the world at the time of each senior’s graduation. Such history-oriented panels provide unique commentary on cultural movements, political events, and global news through the fascinating lens of a Belmont Hill senior about to enter the adult world.

Specifically, this article will focus on World War II as told through Belmont Hill’s panels from 1940 to 1945. World War II had a profound impact on Belmont Hill. Several faculty members departed as they were drafted to fight overseas, even including the headmaster at the time, Thomas R. Morse. Enrollment at the school sharply dropped as families anticipated financial di!culties from the war. Even clubs and extracurricular o erings at Belmont Hill shifted to provide an educational experience more tailored to wartime: Theater, debate, and glee were replaced by First Aid, navigation, and motor mechanics. By analyzing a few of the panels produced at Belmont Hill during World War II, this article hopes to provide greater insight into the thoughts and concerns of everyday high schoolers throughout this war.

Even though the United States had not yet entered World War II when this panel was created in 1940, the themes represented in the carving demonstrate how the possibility of America joining the war was very much present in the minds of Belmont Hill students at the time. The empty rocking chair, sad-looking dog, cane, and hat represent home life, fami-

ly, and comfort. These are juxtaposed with the faded figures of American men marching o to war, highlighting the personal sacrifices soldiers make when heading o to fight for their country. The carver, George Lawrence ‘40, likely chose this topic knowing that if the United States were to join World War II, he would be drafted to serve and fight overseas. Lawrence’s panel indicates that Belmont Hill students paid close attention to World War II in its early stages, knowing that if the U.S. decided to enter the war, their futures would be greatly impacted. The 1940-1941 school year was a time of increasing fear, uncertainty, and awareness about World War II at Belmont Hill. Seven boys from England had joined as refugees of German bombings, and they undoubtedly would have carried their knowledge about World War

II with them. This panel, authored by James Knowles ‘41, shows a French Croix de Guerre (Cross of War), which was a military award given to French soldiers for acts of heroism in battle. Marianne, the personification of the French Republic, is placed at the center of the iron cross, with Republique Francaise inscribed around her. Knowles was referencing the Nazi occupation of France at the time and the establishment of the puppet “Vichy France” regime, intending to convey themes of French resilience, hope, and struggle against the foreign invaders.

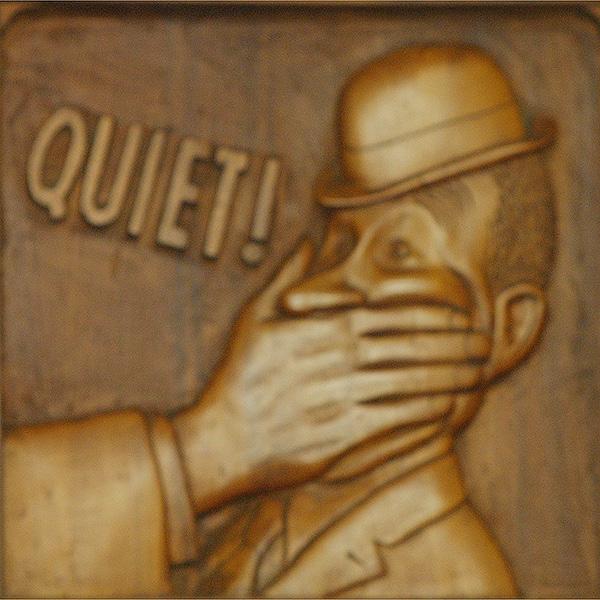

The attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 finally pushed America into joining World War II, and many panels from the class of 1942 reflect the tension and excitement of war. The U.S.

government used patriotic slogans and propaganda to reinforce a culture of nationalism, unity, and individual responsibility. The most famous of these was the phrase “Loose lips sink ships,” which cautioned citizens of inadvertently sharing sensitive wartime information with the overseas enemy. This panel, by Robert Baldwin ‘42, likely sought to portray this; a hand silences the cartoonish man, and the bold text – QUIET! – alludes to the wartime emphasis on secrecy. Baldwin’s panel is one of many that demonstrate how Belmont Hill students questioned and reacted to the cultural shift as America was violently and suddenly brought into World War II.

As the war neared its end, the Battle of Iwo Jima shocked the American public with its bloodiness. Japanese soldiers fought with extreme resolve and near-suicidal determination, knowing that American troops were encroaching on the Japanese mainland with every

island that was captured. This panel, by Thomas Kau man ‘45, depicts an iconic photograph taken of U.S. Marines raising the American flag atop Mount Suribachi during the battle of Iwo Jima. Kau man’s decision to carve this image demonstrates the extent to which students at Belmont Hill were moved by the sacrifices and resilience of American soldiers during World War II.

The Podium | History on the Hill

Preserving Representation: Why the Electoral College Still Matters

Jack Ramanathan ‘26

Since the framing of the Constitution, our founding fathers have understood the necessity of holding fair and just elections, especially for the o!ce of the president of the United States. However, determining how a “fair and just” election would be held presented a confusing challenge to the framers. During the Constitutional Convention of 1787, many different plans to elect the president were opinionated. Some delegates argued for Congress to elect the president, and others insisted on a popular vote to determine the holder of executive o!ce. Ultimately, a compromise between the two - known as the Electoral College - was reached. For the next 237 years, The system has served as a vital mechanism that ensures smaller states have a voice and has prevented the dominance of urban centers over the entire country.

The Electoral College has allowed for a wider representation of America to have a more meaningful and impactful vote in presidential elections. It also prevents highly populated urban areas with dense media markets from deciding the fate of the presidency. Such a system forces candidates to campaign across the country to places like Vermont or Wyoming, which has more influence than their population alone would suggest, preventing large states from monopolizing elections. The Electoral College also addresses the Founders’ fears of “tyranny of the majority,” where, in a democratic race, the majority party pursues its own objectives at the expense of minority parties. If a popular vote were to decide who would hold the o!ce of the president, a candidate that would solely represent problems in big cities, such as Los Angeles, New York City, or Chicago, would be elected over a di erent candidate that would support the needs of other, more rural states. That being said, the Electoral College can still elect a president that supports the needs of

cities. However, it also requires the president to be more mindful of problems more applicable to all of America rather than specific or concentrated areas.

While some citizens may argue that a popular vote would be more democratic and thus fair to elect a president, they would also overlook the intention that our founding fathers had; they designed the Electoral College to protect the country from the risks of a purely majoritarian society, where highly populated cities would determine the outcome of elections. Centuries later, that same argument that the founders had is in some ways even more applicable today, with over 80% of Americans living in cities.

Rather than creating an amendment to abolish the Electoral College, we should consider reforming the system and allocating the amount of electoral votes in each state. By doing so, the concerns of fairness in elections without dismantling the entire election system would be better addressed.

In a country as diverse and vast as the United States, the Electoral College remains the best method for balancing the needs of all States, and ensuring proper representation within each presidency.

Should Teachers Be Able to Use ChatGPT to Grade?

In recent years AI has become a transformative technology in numerous industries. One of the most controversial uses of AI is in school by both teachers and students. Teachers are often burdened with large numbers of papers and tests to grade, and AI could certainly expedite the process with consistency. However, teachers should not be allowed to use AI in grading as it lacks the nuance required for e ectively grading subjective assignments and diminishes the human relationship that is central to the classroom environment.

AI lacks the emotional intelligence and depth to properly grade subjective assignments such as essays, research papers, or creative writing. At first glance, the advantages of AI grading are obvious. When it comes to objective assignments such as multiple choice, math, or grammar and syntax questions, AI is able to quickly and e ectively determine their correctness. Essays and creative projects are far from questions with a simple one-dimensional correct answer. They require students to use their critical thinking skills, synthesize diverse sources of information, and craft arguments from the student’s personal experiences and insight. These assignments require an evaluation process beyond technical accuracy and incorporate emotional resonance and meaning, areas where AI currently struggles to perform e ectively. AI also lacks the ability to

grasp context in complex writing assignments. Whether it’s historical context in a history paper or an underlying theme in an English paper, this information may not be present in an AI data set, resulting in the AI not being able to fully grasp the implications of this context.

AI’s lack of emotional understanding also destroys the student-to-teacher emotional connection that is crucial in a classroom environment. Feedback from teachers is often more important than the grade itself, as it allows the student to adapt and improve. A teacher’s comments provide sympathy, motivation, and guidance, allowing the student to rethink their approach. AI-generated responses no matter how

accurate at identifying technical errors, cannot often have the same depth of human insight that allows students to thrive and grow.

Ultimately the decision to allow teachers to use AI for grading should be made carefully. It is certainly an e ective tool to minimize and teacher’s workload and reduce human error. However, it should not replace human judgment entirely, or replace the relationship aspect of teaching. As for students, if AI becomes integrated into the classroom environment it should be used as a tool for enhanced learning, for example creating practice questions, or asking good questions, but should not be used as a shortcut in the student’s educational experience.

Driving in Reverse: The Truth About Charging Forward with Electric Vehicles

Rylan Dean ‘26

The international automobile industry should not transition toward electric cars in the near future under the current circumstances of their sustainability. In the ever-substantial world of a rising climate and increased carbon dioxide emissions, the question of electric cars is at the forefront of every automotive company’s list. Nearly 20% of all carbon emissions annually are a result of gas-powered cars. Not only does the operation of these vehicles lead to an outpouring of CO2 into the atmosphere, but also the delivery and manufacturing. The environmental results of these issues are terrifying to say the least. Without immediate action, the earth’s average temperature may see an extreme increase of 8.6°F by 2100, leading to the annihilation of ecosystems, an increase in destructive storms, and a severe displacement of communities.

It would only make sense for the solution to this problem to be that we should replace all gas-powered cars with electric vehicles in order to immediately cut our emissions before its too late. However, by taking a closer look at the underlying implications of both the production and disposal of these electric automobiles, a valid argument can be made for why we should wait to integrate them into society. First of all, the average carbon emissions from the assembling of an electric and gas car are both around seven to ten tonnes, showing no signs of improvement on the electric side. However, the production of an average electric automobile battery emits an additional nine tonnes of carbon dioxide into the environment. So before either of these cars is on the road, the electric car has already released double the amount of carbon dioxide than a gas-powered car would in manufacturing.

The story does not end here either. The

idea of charging cars rather than filling them up with gas might sound like a simpler and more sustainable solution to lowering carbon emissions; however, most charging stations worldwide actually receive their energy from fossil fuel or gasoline-powered power plants. These sources emit around 400-800g of carbon dioxide per kWh of charging (the average battery capacity of an electric car is 60kWh/300 miles). The di erence in carbon release into the atmosphere between electric and gas-powered cars might not be as large as we think. This raises a question that almost all car companies and national governments are asking right now. Should the car industry really be aiming at a full electric fleet on the roads by the end of the decade?

The answer to this question is twofold. On one hand, you keep with the old and continue the production gas powered cars that continue to destroy the air with tailpipe emissions. On the other hand, you make a full switch over to electric cars but see basically no positive outcome due to the fossil fuel-powered charging stations. The solution to this problem is simplicity and patience. Charging stations running on renewable energy sources such as wind turbines and solar panels only emit around 36g of carbon dioxide per kWh, significantly less than power plants. If we made a complete shift to electric vehicles within the next year, charging stations would become overloaded and only worsen the emission situation. Therefore, national governments should direct most of their focus toward creating charging stations that run on renewable energy rather than trying to increase the number of electric cars on the road. Only once all the problems of supply chain and charging emissions are solved should we begin to discuss the idea of electric cars taking over the roads.

RESEARCH PAPERS

“A Practice So Repugnant to Catholic Feelings”: U.S Catholic AntiSlavery movements in the AnteBellum and Early Civil War Eras

Winner of the 2024 Monaco American History Prize

James Keefe ‘25

Introduction

On the eve of the United States’ independence from Great Britain, Catholics numbered less than 25,000 (approximately 1% of the overall population of the original 13 colonies) and were concentrated primarily in the more tolerant Middle Colonies.1 However, after religious freedom was protected constitutionally by the fledgling American republic, the Catholic Church’s demographics expanded rapidly.2 By 1850, the Church counted approximately 1.75 million faithful.3 Much of this expansion was due to an influx of people from the Catholic Old-European - predominantly Ireland and Germany.4 While Protestantism was still the largest Christian sect in the United States, Catholicism had become the largest single denomination.5

This massive and diverse growth also gave birth to a significant backlash in the form of anti-Catholicism and nativism in the U.S., which portrayed Catholics and immigrants, among other things, devils seeking to undermine American democracy. Many prominent figures in the United States embraced these ideas, spurring the brief significance of the reactionary, anti-immigration, and xenophobic Know-Nothing political party.6 However, the Catholic Church persevered through such adversity by balancing assimilation into Americanized culture with the preservation of distinct religious and ethnic heritage.7

This shift in the Church’s demographics mirrored its stance on slavery. Many of the first U.S. Catholics inhabited the Catholic hav-

en of Maryland and supported the institution of slavery. However, this began to change as the Vatican and the Society of Jesus became more skeptical of slave ownership.8 Ultimately, the influx of immigrants into America shifted the balance of power - and the Church’s centre - towards foreign-born Catholics, who would occupy many of the clerical positions in the Church by the Ante-Bellum period.9 These foreign-born Catholics were relatively new to America. Although many held strongly negative views on the “peculiar institution” of slavery, many more were focused primarily on simply trying to make it in their new country, before rocking the boat politically on behalf of another population. This sentiment was only further influenced by the aforementioned rise in nativism. This duality would persist for decades and provides insight as to why a majority of the Catholic faithful failed to take a strong stance against slavery.10

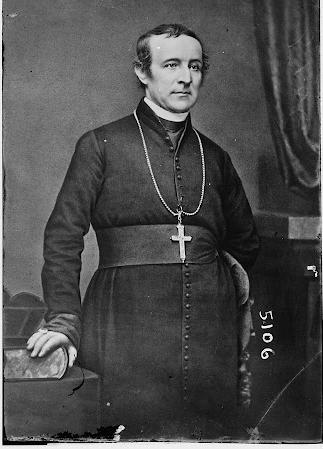

During the Ante-Bellum and early Civil War eras, the Catholic Church in America counted among its ranks many staunch anti-slavery advocates and had received a significant degree of anti-slavery guidance from the Vatican; however, despite this influence, the American Catholic Church at large remained neutral on the issue. Three examples of this conflict provide insight on this failure to win hearts and minds First, while Catholic anti-slavery movements did gain traction via prominent figures such as Daniel O’Connell as well as the duo of Bishop John Baptist Purcell and Fr. Edward Purcell; all saw their work undermined by a population of faithful that was more concerned with issues of inte-

gration, Catholic oppression abroad, or fears of nativist backlash than activism. Next, the Vatican, while publishing several anti-slavery encyclicals, directed its spiritual and moral guidance towards Portugal and Spain, both overwhelmingly Catholic countries that remained active in the international slave trade and largely left America’s slavery question as a secondary issue. Lastly, Irish-born Bishop John England and his allies ultimately won more hearts of the faithful and the direction of the Church based on their neutral approach and focus on combatting nativism via appeasement rather than conflict on the issue of slavery. Ultimately, despite strong voices to the contrary, neutrality with respect to slavery was more convenient, appealing, and expedient to a rapidly changing American Catholic Church.

By way of context, Catholicism existed in the New World since first contact with mainland Europeans. Spanish and Portuguese explorers, almost universally Catholic, often sought to expand their faith in addition to their flag as they moved across the continent.11 These early explorers were followed by the French - also overwhelmingly Catholic - and then lastly the English - primarily Protestant.12 Catholic missions exploded across Latin America and New France (extending from Eastern Canada to the Mississippi Delta). Religious orders such as the Jesuits, Franciscans, and Dominicans thrived during this period, influencing politics, theology, and society.13 One notable cleric among these orders was Bartolomé De las Casas, a Dominican priest and the first anti-slavery advocate of importance from the Old World. Through his decades-long life in the Americas, De Las Casas fiercely battled the system of Encomienda.14 A practice which claimed evangelization and protection as its goal, but it resulted in the de-facto enslavement of Native Tribes.15 De Las Casas continually attempted to sway the Spanish Crown toward his

views - and eventually succeeded in doing so - by publishing scathing reports of atrocities committed against the native population.16 These actions, among others, resulted in De Las Casas being coined as a “friend to the Indians”.17 However, these missions and Catholic presence were largely absent from the 13 colonies of England - which became the United States of America.18 Indeed, with the potential exception of Maryland, Catholics in the British colonies - few that there were - were absent from positions of influence. They were excluded from residing in certain areas, barred from holding Mass (except in Pennsylvania), and treated as second-class citizens.19 These conditions were exacerbated during subsequent conflicts between the three colonial powers of Britain, France, and Spain, which ultimately culminated in the Seven Years War. At the end of the hostilities, France’s Catholic banner was near-banished from the New World.20 Although the Spanish presence would persist for decades after the war, by and large, Eastern North America firmly fell into the hands of British-backed Protestants.21 By the Early 1800s - around the same time as the beginning of Ante-Bellum slavery - Spain too lost the plurality of its colonies at the hands of nationalist rebellions in Latin America.22, 23

In addition, with respect to the issue of slavery, the Catholic Church had a long, complicated, and notable history. For a significant portion of its ministry, the Church existed in nations where slavery was not only permitted but quotidian.24 In fact, early Christians - to whom Catholics trace back their faith - were often themselves enslaved by Roman masters.25 Due to slavery’s common nature over centuries, a!rmed by its presence in the Bible itself, the Church primarily viewed the institution as it would any other state of being - simply preaching Christian morality in its exercise.26 Although reprehensible today, there was a significant theological movement that

believed slavery could be moral should the master treat his slaves as “brothers” and equals.27 Even then, however, a relationship such as this was nigh impossible due to the inherently hostile nature of slavery. Thus, although there is documentation to support that the Church stepped in during the worst cases of abuse, it had not fundamentally and completely broken with the legacy of the institution prior to the creation of the United States.28 Yet, as time went on, the Church began to become more socially conscious, specifically concerning the issue of slavery. Although scholars debate when precisely slavery was o!cially outlawed in the Church - with some saying as early as 1435 and others arguing for as late as 1965 - they generally agree that, particularly in the Vatican, a movement against slavery had been fermenting and gaining traction by the late 18th century.29

Anti-Slavery Voices: O’Connell & the Purcells

During the Ante-Bellum era and the early stages of the Civil War, Anti-Slavery Catholic advocates, such as Daniel O’Connell and brothers Bishop John Baptist Purcell and Fr. Edwards Purcell, became among the most influential Catholic figures in America. These men fought painstakingly against the “peculiar institution”; however, due to a multitude of factors, their missions did not resonate with the majority of Americans.

Daniel O’Connell was a renowned Irish Catholic political leader during the Early 19th century and was immensely popular among the Irish population in Ireland and America.30 Born in County Kerry in 1775, O’Connell would become a lawyer and leader in the movement to liberate Ireland. A proponent of peaceful protest, O’Connell was known to gather crowds of over 100,000 for his rallies.31, 32 He also took an aggressive stance against slavery in the United States and desired to turn his fellow Irishmen against the institution.33

However, though Daniel O’Connell’s work was immensely impactful on the Church in Ireland, it was largely lost on the American Church due to the distraction of Irish-Americans, who were more concerned over civil liberties being stripped away by the British gov-

ernment in Ireland. Additionally, even in the height of his American mission, O’Connell was considered to be something of a foreigner. He was an Irishman born and raised, and Ireland is where he called home, as his detractors would point out.34 This would be used to attempt to discredit O’Connell’s scathing anti-slavery criticisms, which were primarily directed at America.35

Even so, O’Connell had a long history of combatting American slavery, attempting several times to rally people to put an end to the institution for good. The American abolitionist Frederick Douglass toured Ireland and heard O’Connell speak at an Abolitionist rally in Dublin. O’Connell declared to his audience,

“I have been assailed for attacking the American institution, as it is called,—Negro slavery. I am not ashamed of that attack. I do not shrink from it. I am the advocate of civil and religious liberty, all over the globe, and wherever tyranny exists, I am the foe of the tyrant; wherever oppression shows itself, I am the foe of the oppressor; wherever slavery rears its head, I am the enemy of the system, or the institution, call it by what name you will. I am the friend of liberty in every clime, class and colour. My sympathy with distress is not confined within the narrow bounds of my own green island. No—it extends itself to every corner of the earth. My heart walks abroad, and wherever the miserable are to be succored, or the slave to be set free, there my spirit is at home, and I delight to dwell.” 36

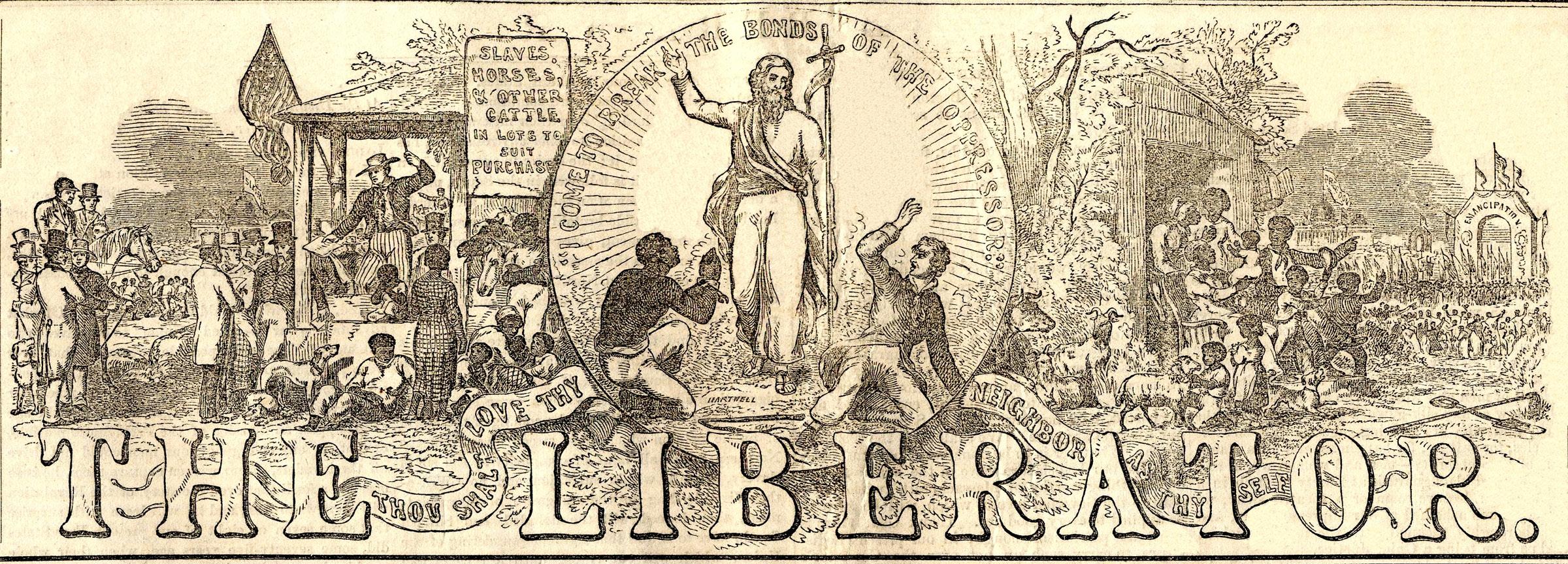

Another famed black abolitionist, Charles Lenox Remond, was deeply moved by rebukes like these and wrote to William Lloyd Garrison in 1845 after his own tour of Ireland: “My Friend, for thirteen years I have thought myself an abolitionist, but I had been in a measure mistaken until I listened to the scorching rebukes of the fearless O’Connell”. However, perhaps most notable of O’Connell’s pushes to end American Slavery was a petition he signed and circulated, “An Address of the People of Ireland to their Countrymen and Countrywomen in America.37” Noticing the surging Irish American population in the United States, O’Connell firmly believed that if united, they could be a political force unleashed against slavery. Further, understanding that all the Irish Cath-

olics had left a brutal system of oppression at the hands of the British, O’Connell believed the Irish would be the most likely to empathize with the struggle of Black Americans in their newfound country.38 As stated in “An Address …”, “Irishmen and Irishwomen! Treat the colored people as your equals, as brethren. By all your memories of Ireland, continue to love liberty [and] hate slavery - cling by the abolitionists and in America you will do honor to the name of Ireland.” 39 While O’Connell may not have been completely wrong in the logic of Irish-American understanding of the African American plight, history would prove him naive to hope that this sentiment would lead to Irish-Americans turning en masse against their country of refuge.40

The O’Connell-backed petition began in Ireland, where it was distributed across the country by O’Connell’s many Irish allies, rapidly gathering approximately 60,000 signatures in mere weeks.41 Notably, O’Connell found the most adamant supporters of the petition to be Irish Catholic clergymen, with many rallying members of their parishes to the cause. Thereafter, Lenox Remond - at O’Connell’s instruction - departed Ireland for Boston with the petition in hand.42 There, he met with several other abolitionists, namely William Lloyd Garrison, George Brayburn, and Wendel Phillips (among others). They organized an event at Faneuil Hall where the petition would be unveiled and read to the public. Boston’s community was ecstatic to witness the reveal of the

document, and Faneuil Hall was packed with 5,000 people - about 1,500 of whom were Irish immigrants.43 There, they were treated to rousing speeches by the event organizers and others - many painted the similarities between the Irish struggle in Ireland and the Black struggle in America. Phillips even gave a particularly noteworthy testament to the nature of the Catholic Church, stating:

“African lips may join in the chants of the Church, unrebuked even under the proud dome of St. Peter’s; and I have seen the colored man in the sacred dress pass with priest and student beneath the frowning portals of the Propaganda College in Rome, with none to sneer at his complexion... [A] long line of Popes, from Leo to Gregory have denounced the sin of making merchandise of men - that the voice of Rome was the first to be heard against the slave trade - and that the bull of Gregory XVI, forbidding every true Catholic to touch the accursed thing, is yet hardly a year old.44”

Ultimately, however, it may have been that the then-current situation in Ireland resonated more with these Irish Bostonians. Daniel O’Connell’s other loyalty resided with the Irish Repeal movement, which strove to repeal the Act of Union forced upon Ireland in 1800. This legislation stripped many of Ireland’s previously given freedoms and amounted to a crackdown on Irish self-governance by the British.45 This enraged a large swath of the Irish people and the many Irish Americans who still sympathized with the su ering of their homeland.46

As both slavery and repeal were topics discussed at this Faneuil Hall gathering, one could reasonably presume that the latter reason attracted the Irish Americans at least as much, if not more, than slavery. An examination of the aftermath of this event confirms this assumption. Although the O’Connell-endorsed petition had an overwhelmingly positive response initially - with the Irish in Philidelphia, in particular, flooding anti-slavery o!ces to obtain copies of the petition, over time, this response soured.47 First, Irish-owned or backed newspapers began to cover the anti-slavery cause with a degree of skepticism, reemphasizing instead the importance of repeal.48 While the articles still opposed slavery in its most fundamental sense - they clearly stated that the priorities of Irish Americans should be the support of a free homeland and not fraying bonds in their new nation.49 From there, criticism of the petition escalated, particularly among the Democratic-led political machines who were the primary supporters of the Repeal movement in the United States.50 Seeing a connection between Repeal and anti-slavery as potentially disastrous for the overwhelmingly pro-slavery Democrats - who drew many immigrants into their fold via direct aid upon their arrival - leading Democrats ripped into O’Connell, hoping to dissuade the Irish from endorsing his views.51 Although many Irish would stand up for their hero, precious few would publicly endorse his views in the face of their benevolent Democratic machine bosses.52, 53

Ultimately, O’Connell’s e orts - although legion - failed to sway a preponderance of American Catholics against slavery, particularly the Irish-Americans that he targeted. For these Americans, O’Connell and his allies stretched themselves too far. He alienated many who would otherwise have been sympathetic to the petition’s cause via its scathingly public critiques on slavery, as such positions would upset many of America’s immigrant-driven, Protestant-led and pro-slavery Democratic political machines who were the source of many economic and social opportunities for Irish-Americans. Such rhetoric calling for these Americans to “bite the hand that fed them” was unappealing for those reaping the benefits of the status

quo.

Bishop John Baptist Purcell and his brother, Father Edward Purcell, faced similar opposition to their anti-slavery ideals. Like O’Connell, both were Irish-born; however, the Purcells di ered in station - one being Archbishop and the other a Priest in the American Catholic Church.54 Both of these posts granted them a di erent but significant sway over the a airs within their own Archdiocese of Cincinnati and a large amount of influence over the Catholic Church in the US.55 Interestingly, both men are often credited as the first prominent American Catholic figures to directly and publicly oppose slavery.56 Although the Purcells’ activism is notable, their most public and scathing criticisms came during the onset of the Civil War, with their message losing impact due to the tumult of the time. Additionally, Bishop Purcell ultimately did not publicly challenge his fellow Bishops theologically, instead taking the path of most Catholic Bishops of the day by prioritizing the unity of the Church - a philosophy whose importance was only exaggerated by the high degree of nativism that gripped the nation at the time.

Archbishop John B. Purcell and his brother were a force to be reckoned with in 19th-century America. John Baptist would play the role of the figurehead and leader of the Archdiocese. He represented the interests of the Church and Cincinnati at conferences, in speeches, and his work for the city’s community.57 One of his primary endeavors was his advancement of the anti-slavery movement. However, John Baptist was not as public as his brother due to the public scrutiny inherent in his position.58 Archbishop was a title that demanded one to serve the entire Catholic community and was often considered nonpartisan.59 Thus, as Ohio was a free state with many still sympathetic to pro-slavery movements, a measured approach was a necessity for the Archbishop.60 Pragmatism may also have dictated this, as the Archdiocese of Cincinnati was very diverse, and the immediate emancipation of slaves may have drastically increased tension and violence concerning employment and economic opportunities.61 Nevertheless, John Baptist still practiced a degree of bluntness when faced with this issue,

decrying the “virus” of slavery in speeches dating back to 1838 and later expressing slavery as “ a practice so repugnant to Catholic feelings”.62 63 Further, Archbishop Purcell was an unflinching unionist, and he would hang the stars and stripes over his Cathedral for the duration of the Civil War - a time in which his and Edward’s anti-slavery sentiments grew far more public.64

On the other hand, John’s brother, Edward, often served as the mouthpiece for the Purcells’ anti-slavery positions. Fr. Edward was the editor of the Catholic Telegraph - a diocese-supported and endorsed newspaper - from 1840 to 1879. 65 Fr. Edward published a large variety of anti-slavery documents in this newspaper, including an express and direct condemnation of the sin of slavery and slaveholding in 1863.66 During the Civil War period, he would decry slavery as “the cause of all our national trouble” and called for, “Shame on the man who would uphold a system which mocks at matrimony, oppresses the poor, deprives the labourer his wages and sends the wife and daughters to the slave-pen to be sold to the highest bidder”.67 Such a declaration, although relatively late compared to secular anti-slavery movements, was profound as it was a clear, published anti-slavery stance in a o!cial Church publication sanctioned by an American Catholic Church that had tried for many years to stay neutral.68 Beyond that, however, the Catholic Telegraph published many less direct condemnations of slavery over the years before the Civil War.69

Both John and Edward Purcell spent much of their lives fighting against the injustice of slavery and attempting to define the Archdiocese of Cincinnati as a harbor for equality. However, their e orts fell short, in all likelihood, due to their reluctance to do so more publicly and sooner. Archbishop John had several opportunities to directly challenge Southern bishops on the issue before the Civil War, yet he instead prioritized the unity of the Church. Fr. Edward - by extension - also measured his criticisms to a degree until the commencement of the war in order to stay aligned with his brother’s position. Many of the causes of such discretion were not entirely either man’s choosing. Operating in a free state with

a significant pro-slavery populace, tensions between Catholic immigrants and African Americans for jobs, and the necessity to maintain a unified church despite di erences all made a tempered approach necessary. In summary, while both men were trailblazers in the Catholic anti-slavery movement in the US they did not push the agenda far enough.

The Vatican’s Opinion: In Supremo Apostolus In 1839, Pope Gregory XVI signed an encyclical titled In Supremo Apostolus. 70 To any modern reader, this Papal bull would read as another in a long list of direct condemnations of slavery from the Vatican. Written in the late 1830s, In Supremo Apostolus was directed at the Spanish and Portuguese, who were continuing to engage in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.71 Both countries were almost entirely Catholic and longtime loyal allies of Rome.72 As such, the intent was to dissuade both nations from continuing this practice by o!cially condemning it as a sin in the strongest possible terms (even though the Vatican had already long technically considered such an act to be such).73 In Supremo Apostolus gathers centuries of Papal and Ecclesiastic Canon and evidence and uses them to attack Slavery in a nearly all-encompassing fashion.74 75 However, there still were loopholes that Slavers, particularly in the United States, used to get around such admonitions.76 Thus, despite the Vatican’s Bull containing a significant degree of anti-slavery language, it was viewed by a majority of the American Catholic Church as an encyclical only intended to ban the slave trade still practiced by Spain and Portugal, as opposed to banning slavery in the American South.

In Supremo Apostolus was not without precedent, and as Pope Gregory XVI notes, many of its fundamental tenets had been expressed numerous times over centuries of Church history.77 However, what made this bull di erent - in the lens of the American Church - was as much the timing as anything else. The issue of slavery had been a political pressure cooker for decades in the United States, and both sides of the argument were looking for any ability to increase their influence.78 In Supremo Apostolus, complete with virulent anti-slavery language,

mirrored many of the messages of Anti-Slaverites in the United States and seemed a direct condemnation of Slavery.79 80

“We say with profound sorrow – there were to be found afterwards among the Faithful men who, shamefully blinded by the desire of sordid gain, in lonely and distant countries, did not hesitate to reduce to slavery Indians, negroes and other wretched peoples, or else, by instituting or developing the trade in those who had been made slaves by others, to favour their unworthy practice.81”

Indeed, Gregory’s description of slave-holders as “shamefully blinded men” and expressing the Church’s profound disappointment with their actions is quite damning.82 However, some slavers were able to escape such condemnation via the Pope’s later remarks:

“We reprove, then, by virtue of Our Apostolic Authority, all the practices abovementioned as absolutely unworthy of the Christian name. By the same Authority We prohibit and strictly forbid any Ecclesiastic or lay person from presuming to defend as permissible this tra!c in Blacks under no matter what pretext or excuse, or from publishing or teaching in any manner whatsoever, in public or privately, opinions contrary to what We have set forth in this Apostolic Letter.” 83

Specifically, those sympathetic to the system of American slavery focused on the ban on “tra!cking blacks” and “reducing blacks to slavery”.84 In their mind, tra!cking Black slaves ended in 1808 with the ban of the international slave trade in the United States, and as American law dictated that slaves were enslaved by birth, there was technically no practice of “reducing” Blacks to slavery.85, 86 Thus, those supporting slavery characterized the bull as supporting the status quo in the US.

The Vatican - occupied with the encyclical’s intended recipients in Spain and Portugal - did little to dissuade this convenient misinterpretation.87 Instead, they allowed neutralist bishops and other clergy to fill the translation void in the US through the publication of much less controversial interpretations of the bull. Neutralists, such as Bishop John Hughes and Bishop John England, released clarifying

statements regarding their interpretation of the encyclical’s “true meaning”.88 Abolitionists did attempt to capitalize on the encyclical. For example, the aforementioned gathering at Faneuil Hall also included a reading of In Supremo Apostolus. 89 However, much like in the aftermath of Daniel O’Connell’s e orts, many Catholics chose to listen to the opinion of the neutralists and maintain a low profile on this increasingly tense political issue.90 Further, when information emerged that the Protestant British government had a role in recommending to the Vatican the publication of the encyclical, the importance of the document was diminished for much of the immigrant Catholic community and US patriots alike.91

The Neutralists: England & Hughes

While there were a significant number of anti-slavery figures in the American Church, they were often opposed by a segment of the clergy who desired neutrality on the issue. These neutralists often took stances to defend slavery in order to counterbalence their anti-slavery brothers and sisters in Christ.92 Most prominent among these figures were Bishop John England of Charleston and Archbishop John Hughes of New York. Both of these men had a highly complex relationship with the institution of slavery. Both were originally from Ireland and had a focus on education.93 Both grappled with rising violent nativist movements.94, 95 Both, on occasion, criticized pro-slavery members of their communities. Nevertheless, history remembers them as men who resisted pressure from anti-slavery Catholics, and while both attempted to reconcile an increasingly polarized nation and world, such actions would portray them as defending slavery in various instances.

Bishop John England was born in Cork, Ireland, and was ordained in 1809. As a young priest, he fought in Ireland for the rights of prisoners, Catholic emancipation, and the dignity of the poor and needy.96 These qualities would follow England throughout his life, despite him not fully embracing them concerning slavery. England became the Bishop of Charleston in 1820 and began his ministry there shortly thereafter.97 Interestingly, England original-

ly included slaves and African Americans in his ministry to a higher degree than many of his contemporaries in the Ante-Bellum South at the time.98 He would minister to slaves and set up free schooling for African Americans in his diocese. However, these measures would come to a screeching halt during a nativist riot in 1835. Many of England’s schools were targeted and had to be defended by a volunteer Irish immigrant self-defense force.99 Shortly thereafter, England shuttered the schools and ended many of his more progressive initiatives.100 This retrenchment in the face of pressure would be a common theme for England, who often would prioritize the well-being of the majority of his Catholic community over his personal morality.101 He would go on to defend many Democratic candidates against accusations related to nativism and racism - likely due to Irish Catholics’ close relation to the party in exchange for economic opportunities in an otherwise hostile environment.102 England’s defense of divisive figures and institutions was on full display during his response to In Supremo Apostolus. England proactively published both the original Latin and an English translation of the document in his newspaper “US. Catholic Miscellany” along with his own analysis limiting the extent of the encyclical to simply a condemnation of the international slave trade - which had been outlawed in the United States since 1808.103 104 However, England did not stop there. John Forsyth, the then-current U.S. Secretary of State and Georgia native attempted to stir up anti-Whig sentiment by linking the “catch-all party” to abolitionism. In his statements, Forsyth linked domestic abolitionist sentiment with a rising tide of abolitionism worldwide - specifically mentioning In Supremo Apostolus as an example.105 Despite this being a mere political statement to swing Southern voters and was not directed at England or his congregation, the Bishop became

concerned that such wording would be used against Catholics in the pro-slavery South.106 Consequently, John England went on a writing campaign in his newspaper, first condemning Forsyth’s words and the potential discrimination that could result from them but then later expanding his thoughts to address slavery as a whole.107 In these articles, England delved into scripture from the Old and New Testaments to detail exactly what forms of slavery were forbidden - or conversely - acceptable under Catholic doctrine. He concluded that the Church was at least tolerant of slavery throughout its history, although the Church viewed all slaves as human beings created by God and should be treated as such.108 Much of the commentary regarding the doctrine of “just” or “moral” slavery went unopposed by other American Bishops. As such, neutralists would become the de-facto opinion of the American Catholic Church, preaching morality and respect for others yet not directly opposing the institution of slavery.109

Archbishop John Hughes grew up in Ulster (Northern Ireland). Following religious and ethnic persecution there, he immigrated with his family to the United States in 1816 and was ordained a priest 10 years later in Philadelphia. He would go on to become Bishop and later Archbishop of New York.110 Archbishop Hughes is notable for his impact on New York and founding Fordham University in the Bronx.111 However, Hughes would - like England - become an advocate for neutrality.112 Hughes had long favored the assimilation of immigrants into American society - which he viewed as important for the Church’s survival in the United States.113 He may have had a valid basis, as a string of nativist attacks forced Hughes to post armed guards outside of each church in the city.114 Unfortunately, this belief also extended to the system of slavery as well. When the Daniel O’Connell-backed anti-slavery petition An Address of the People

of Ireland to their Countrymen and Countrywomen in America searched for signatories in America, Bishop Hughes actively encouraged his flock not to sign it - hoping to make as few waves as possible.115 As a prominently influential Catholic figure at the time and one of the few men with the status of Archbishop in North America, such a statement was extremely detrimental for a document almost entirely reliant on Irish Catholic support in America.116 Ultimately, the legacy of both Hughes and England was that of players at a constant game of juggling regional, Church, and moral interests in a hostile environment. Thus, the American Catholic Church would o!cially remain silent on the issue, as its two of its most influential members held this as a rule.117, 118

Conclusion

Icons opposed to slavery in the American Catholic Church were plentiful during the 18th-century periods of the Ante-Bellum and the Early Civil War eras. These forces notably included anti-slavery advocates, such as Daniel O’Connell, Bishop John Baptist Purcell, and Father Edward Purcell, in addition to the guidance of the Vatican. However, the neutralist viewpoint - one of defending the institution’s existence without supporting it - was expressed by Bishops John England, John Hughes, and others and would ultimately win. This result was due to concerns regarding the status of Catholics abroad, the Catholic Church in the U.S. wielding less political and social power than their old world counterparts, a fear of nativist backlash due to Catholic advocacy, and a variety of other factors.

One aspect not yet to be addressed in this paper is the matter of Black Catholics. Black Catholics have also existed in the U.S. since its inception - particularly in the South - and formed significant cultural and religious communities, namely in the old Louisiana territory.119 While Black Catholics were a part of each of the dioceses previously mentioned and overall a part of the broader U.S Catholic Church, they also fought against the institution of slavery in their own unique ways.

A primary example of this - albeit 100 years before the In Supremo Apostolos, Dan-

iel O’Connell, the Purcell Brothers, and the neutral Bishops- is the Stono Rebellion. This event is significant, as it marked an instance in which Black Catholic slaves organized a rebellion against their white, Protestant, English slaveowners in order to preserve their liberty, religion, and cultural traditions. The majority of these slaves - and almost the entirety of its leadership - were taken from the same African kingdom, Kongo.120 Kongo (in present-day Angola) was a fascinating nation as it was profoundly Catholic whilst never having been colonized. Catholicism represented a fundamental part of the Kongolese identity, and the Kingdom of Kongo had independent relations with the Vatican, Kongolese Catholic schools, and a relatively high literacy rate at the time.121 It is believed that leading up to the Stono revolt, the Kongolese slaves were in contact with the Catholic Spanish, who encouraged them to rise against their slaveowners and seek physical and spiritual asylum in St. Augustine.122

On the 9th day of September in the year 1739 - close to a day of Marian veneration in the Kongolese-Catholic calendar - the slave revolt began and would result in the deaths of (approximately) 30 whites and 44 slaves.123, 124 While ultimately the rebellion failed, it holds a place of importance in the struggle against slavery. Immediately evident is that this event arguably marked the most significant Catholic anti-slavery movement since De Las Casas and Encomienda. In the same breath, this movement was driven by the most overlooked Catholic population, African Catholic slaves. Unfortunately, as the Catholic population of South Carolina at the time was almost entirely African slaves whose movement was restricted and were presumably unable to interact with the broader - predominantly white - American Catholic community centered in Baltimore, it is reasonable to assume that many of the Slaves would have seen the Spanish as the only source of Catholicism on the Continent.125 Ultimately, however, this revolt, while important in its novelty, would not accomplish much due to the deaths of the plurality of the slaves involved and the complete disconnection between the rebels and the broader American Catholic community.126

Endnotes

1) ”American Catholics - Digital History.” Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_ textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=2997.

2) U.S. Constitution, amend. 1.

3) “American Catholics - Digital History.” Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_ textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=2997.

4) Lincoln, Mullen. 2013. “Maps of Catholic Dioceses in the US, Canada, and Mexico.” Lincoln Mullen. https:// lincolnmullen.com/blog/maps-of-catholic-dioceses-in-the-us-canada-and-mexico/.

5) 1. Julie Byrne, “Roman Catholics and Immigration in Nineteenth-Century America,” National Humanities Center, 2000, https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/ tserve/nineteen/nkeyinfo/nromcath.htm.

6) “Nativism | Definition, Racism, Chinese Exclusion Act, Japanese-American Internment, Replacement Theory, & Facts.” n.d. Britannica. Accessed May 19, 2024. https:// www.britannica.com/topic/nativism-politics.

7) “American Catholicism,” Site Search, accessed May 20, 2024, https://pluralism.org/american-catholicism.

8) Adam, Rothman. “Georgetown University and the Business of Slavery.” Washington History 29, no. 2 (2017):

9) Kathleen. Flanagan, S.C. “The Changing Character of the American Catholic Church 1810–1850” Vincentian Heritage Journal 20, no. 1 (1999): 5.

10) John F. Quinn, “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 709.

11) Po-chia, R. Hsia. “The Catholic Historical Review: One Hundred Years of Scholarship on Catholic Missions in the Early Modern World.” The Catholic Historical Review 101, no. 2 (2015): 225.

12) Ibid: 240.

13) Ibid: 240.

14) Francis Patrick Sullivan, Indian Freedom: The Cause of Bartolomé de Las Casas, 1484-1564: A Reader (Kansas City, MO: Sheed & Ward, 1994): 240.

15) Ibid: 240.

16) Ibid: 146.

17) Ibid: 353.

18) Po-chia, R. Hsia. “The Catholic Historical Review: One Hundred Years of Scholarship on Catholic Missions in the Early Modern World.” The Catholic Historical Review 101, no. 2 (2015): 239-240.

19) NCHE, Catholics in America, 2016, https://backstoryradio.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/ Catholics-Sources.pdf.

20) “Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations - O!ce of the Historian.” n.d. History State Gov. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/french-indian-war

21) Ibid

22) Diego, Velázquez. n.d. “Western colonialism - Spanish Empire, New World, Colonization.” Britannica. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Western-colonialism/Spains-American-empire

23) Lee, Boomer, and Eastman Johnson. 2023. “Antebellum - Women & the American Story.” Women & the American Story. https://wams.nyhistory.org/a-nation-divided/antebellum

24) Panzer, Joel S. “The Popes and Slavery: Setting the Record Straight: EWTN.” EWTN Global Catholic Television Network, 1966. https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/popes-and-slavery-setting-the-recordstraight-1119.

25) Mary L, Gordon. “The Nationality of Slaves under the Early Roman Empire.” The Journal of Roman Studies 14 (1924): 111.

26) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 79.

27) “Ethics - Slavery: Philosophers Justifying Slavery,” BBC, 2014, https://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/slavery/ethics/ philosophers_1.shtml.

28) Paul III. Sublimis Deus. Encyclical Letter. Papal Encyclicals Online. May 29, 1537. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/paul03/p3subli.htm

29) Joel S Panzer, “The Popes and Slavery: Setting the Record Straight: EWTN,” EWTN Global Catholic Television Network, 1966, https://www.ewtn.com/catholicism/library/popes-and-slavery-setting-the-recordstraight-1119.

30) Shane O’Brien, “Why Is Daniel O’CONNELL so Revered?,” IrishCentral.com, August 6, 2022, https://www. irishcentral.com/roots/history/why-is-daniel-o-connell-so-revered.

31) Patrick M. Geoghegan, King Dan: The Rise of Daniel O’CONNELL 1775-1829 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2010). 168.

32) Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Daniel O’Connell.” Encyclopedia Britannica, May 11, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Daniel-OConnell.

33) John F. Quinn, “Expecting the Impossible? Abolition-

ist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 672.

34) John F. Quinn, “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 697.

35) Ibid: 672

36) Fredrick Douglas , “Letter to William Lloyd Garrison (September 29, 1845),” The Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, April 7, 2015, https://glc.yale.edu/letter-william-lloyd-garrison-september-29-1845.

37) John F. Quinn, “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 690.

38) Ibid

39) Daniel, O’Connell. Address from the people of Ireland to their countrymen and countrywomen in America. [N. P, 1847] Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/11007405/.

40) QUINN, JOHN F. “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America.” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 697.

41) Ibid: 691.

42) Ibid: 691.

43) Ibid: 692.

44) Quinn, “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” 697

45) McNamara, Robert. “Ireland’s Repeal Movement.” ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/irelands-repeal-movement-1773847 (accessed April 3, 2024).

46) John F. Quinn, “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 694.

47) Ibid: 693.

48) Ibid: 693.

49) Quinn “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America.” 694.

50) David Brundage, Irish Nationalists in America: The Politics of Exile, 1798-1998 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019). 60.

51) Quinn “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America.” 696.

52) Ibid. 696.

53) “Political Machine,” Encyclopædia Britannica, March 22, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/political-machine.

54) Satish, Joseph. “‘Long Live the Republic!’ Father Edward Purcell and the Slavery Controversy: 1861-1865.” American Catholic Studies 116, no. 4 (2005): 26.

55) Sebastian Messmer, “Archbishop ,” The Catholic Encyclopedia 1 (1907), https://doi.org/https://www.newad-

vent.org/cathen/01691a.htm.

56) “A Closer Look: The Purcell Brothers, Abolition and The Catholic Telegraph – Catholic Telegraph.” 2020. Catholic Telegraph. https://www.thecatholictelegraph. com/purcell-brothers-abolition-and-the-catholic-telegraph/70302.

57) Satish, Joseph. “‘Long Live the Republic!’ Father Edward Purcell and the Slavery Controversy: 1861-1865.” American Catholic Studies 116, no. 4 (2005): 34.

58) Ibid: 34.

59) Ibid: 34.

60) “Black History - Ohio as a Non-Slave State.” n.d. Shelby County Historical Society. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.shelbycountyhistory.org/schs/blackhistory/ohioasanonslave.htm.

61) Satish, Joseph. “‘Long Live the Republic!’ Father Edward Purcell and the Slavery Controversy: 1861-1865.” American Catholic Studies 116, no. 4 (2005): 34.

62) Ibid: 35.

63) “A Closer Look: The Purcell Brothers, Abolition and The Catholic Telegraph – Catholic Telegraph.” 2020. Catholic Telegraph. https://www.thecatholictelegraph. com/purcell-brothers-abolition-and-the-catholic-telegraph/70302.

64) Satish, Joseph. “‘Long Live the Republic!’ Father Edward Purcell and the Slavery Controversy: 1861-1865.” American Catholic Studies 116, no. 4 (2005): 35.

65) A Closer Look: The Purcell Brothers, Abolition and The Catholic Telegraph – Catholic Telegraph.” 2020. Catholic Telegraph. https://www.thecatholictelegraph. com/purcell-brothers-abolition-and-the-catholic-telegraph/70302.

66) Ibid.

67) Satish, Joseph. “‘Long Live the Republic!’ Father Edward Purcell and the Slavery Controversy: 1861-1865.” American Catholic Studies 116, no. 4 (2005): 36.

68) Ibid: 26.

69) Ibid: 35.

70) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 67.

71) Ibid: 68.

72) Diana Mishkova and Balázs Trencsényi, European Regions and Boundaries: A Conceptual History (BERGHAHN Books, 2018): 126.

73) Gregory XVI. In Supremo Apostolatus. Encyclical Letter. Papal Encyclicals Online. 1839. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/greg16/g16sup.htm

74) Ibid.

75) Paul III. Sublimis Deus. Encyclical Letter. Papal Encyclicals Online. May 29, 1537. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/paul03/p3subli.htm

76) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 86.

77) Gregory XVI. In Supremo Apostolatus. Encyclical Letter. Papal Encyclicals Online. 1839. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/greg16/g16sup.htm

78) Amanda Onion et al., “U.S. Slavery: Timeline, Figures & Abolition,” History.com, April 25, 2024, https://www. history.com/topics/black-history/slavery.

79) Gregory XVI. In Supremo Apostolatus. Encyclical Letter. Papal Encyclicals Online. 1839. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/greg16/g16sup.htm

80) James Brown, Yerrinton, and William Lloyd Garrison. “The Liberator.” Newspaper. Boston, Mass.: William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp, January 14, 1832. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/8k71pj045 (accessed May 22, 2024): 1.

81) Gregory XVI. In Supremo Apostolatus. Encyclical Letter. Papal Encyclicals Online. 1839. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/greg16/g16sup.htm

82) Ibid.

83) Ibid.

84) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 78.

85) Ibid: 78.

86) “Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves,” DocsTeach, March 2, 1807, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/ act-prohibit-importation-slaves.

87) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 92.

88) Ibid: 78.

89) Ibid: 81.

90) Ibid: 92.

91) Ibid: 76-77.

92) John F. Quinn. “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America.” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 709-710.

93) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Histori-

cal Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 74.

94) Joseph, Kelly. “Charleston’s Bishop John England and American Slavery.” New Hibernia Review 5, no. 4 (2001): 49.

95) Elizabeth Stack, “Dagger John: Archbishop John Hughes and The Making of Irish America by John Loughery,” New York History 103, no. 2 (December 2022): 4.

96) Richard H. Clarke, “Lives of the Deceased Bishops of the Catholic Church in the United States, Volume 3: Clarke, Richard H. (Richard Henry), 1827-1911 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1888: 273.

97) “Our History,” Charleston Diocese, April 30, 2024, https://charlestondiocese.org/about/our-history/.

98) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 74.

99) Joseph, Kelly. “Charleston’s Bishop John England and American Slavery.” New Hibernia Review 5, no. 4 (2001): 49.

100) Ibid: 50

101) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 74.

102) John F. Quinn, “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 694.

103) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 75.

104) “Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves,” DocsTeach, March 2, 1807, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/act-prohibit-importation-slaves.

105) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 76-77.

106) Ibid: 78.

107) Ibid: 78-79.

108) John England and J. Murphy, “Letters of the Late Bishop England to the Hon. John Forsyth, on the Subject of Domestic Slavery, Copy 2, 1844,” Letters of the late Bishop England to the Hon. John Forsyth, on the subject of domestic slavery, copy 2, 1844 | Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston ArchivesSpace, 1844: 1.

109) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 78.

110) Elizabeth Stack, “Dagger John: Archbishop John Hughes and The Making of Irish America by John Loughery,” New York History 103, no. 2 (December 2022): 4.

111) Ibid: 4.

112) Satish, Joseph. “‘Long Live the Republic!’ Father Edward Purcell and the Slavery Controversy: 1861-1865.”

American Catholic Studies 116, no. 4 (2005): 26.

113) John F. Quinn, “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 696-697.

114) Elizabeth Stack, “Dagger John: Archbishop John Hughes and The Making of Irish America by John Loughery,” New York History 103, no. 2 (December 2022): 4.

115) John F. Quinn, “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 696-697.

116) Ibid: 697.

117) Ibid: 697-698.

118) John F. Quinn, “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Histori-

cal Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 79-80.

119) “Black Catholic History Timeline,” National Black Catholic Congress Website, October 18, 2021, https://nbccongress.org/black-catholic-history-timeline/.

120) John K. Thornton. “African Dimensions of the Stono Rebellion.” The American Historical Review 96, no. 4 (1991): 1102.

121) John K. Thornton. “African Dimensions of the Stono Rebellion.” The American Historical Review 96, no. 4 (1991): 1103.

122) Mark M, Smith. “Remembering Mary, Shaping Revolt: Reconsidering the Stono Rebellion.” The Journal of Southern History 67, no. 3 (2001): 517-518.

123) Ibid: 527-528.

124) Resistance to the State, accessed May 21, 2024, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/exhibits/deathliberty/resistance/index.htm.

125) Charles H, Lippy. “Chastized by Scorpions: Christianity and Culture in Colonial South Carolina, 1669–1740.” Church History 79, no. 2 (2010): 253–254

126) Mark M, Smith. “Remembering Mary, Shaping Revolt: Reconsidering the Stono Rebellion.” The Journal of Southern History 67, no. 3 (2001): 519.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

“Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves.” DocsTeach, March 2, 1807. https://www.docsteach.org/ documents/document/act-prohibit-importation-slaves.

Clarke, Richard H. “Lives of the Deceased Bishops of the Catholic Church in the United States, Volume 3 : Clarke, Richard H. (Richard Henry), 1827-1911 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, January 1, 1888. https://archive.org/ details/LivesOfTheDeceasedBishopsV3.

England, John, and J. Murphy. “Letters of the Late Bishop England to the Hon. John Forsyth, on the Subject of Domestic Slavery, Copy 2, 1844.” Letters of the late Bishop England to the Hon. John Forsyth, on the subject of domestic slavery, copy 2, 1844 | Ro-

man Catholic Diocese of Charleston ArchivesSpace, 1844. https://archive.charlestondiocese. org/repositories/2/archival_objects/11126.

Gregory XVI. In Supremo Apostolatus. Encyclical Letter. Papal Encyclicals Online. 1839. https://www.papalencyclicals.net/greg16/g16sup.htm

O’Connell, Daniel. Address from the people of Ireland to their countrymen and countrywomen in America. [N. P, 1847] Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/ item/11007405/.

U.S. Constitution, amend. 1.

Paul III. Sublimis Deus. Encyclical Letter. Papal Encyclicals Online. May 29, 1537. https://www.papalen-

cyclicals.net/paul03/p3subli.htm

Yerrinton, James Brown, and William Lloyd Garrison. “The Liberator.” Newspaper. Boston, Mass.: William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp, January 14, 1832. Digital Commonwealth, https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/8k71pj045 (accessed May 22, 2024).

Secondary Sources

Journals:

QUINN, JOHN F. “Expecting the Impossible? Abolitionist Appeals to the Irish in Antebellum America.” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 4 (2009): 667–710. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25652054.

Quinn, John F. “‘Three Cheers for the Abolitionist Pope!’: American Reaction to Gregory XVI’s Condemnation of the Slave Trade, 1840-1860.” The Catholic Historical Review 90, no. 1 (2004): 67–93. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/25026521.

ROTHMAN, ADAM. “Georgetown University and the Business of Slavery.” Washington History 29, no. 2 (2017): 18–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/90015020.

Stack, Elizabeth. “Dagger John: Archbishop John Hughes and The Making of Irish America by John Loughery.” New York History 103, no. 2 (December 2022): 420–22.

Hsia, R. Po-chia. “The Catholic Historical Review: One Hundred Years of Scholarship on Catholic Missions in the Early Modern World.” The Catholic Historical Review 101, no. 2 (2015): 223–41. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/43898525.

Gordon, Mary L. “The Nationality of Slaves under the Early Roman Empire.” The Journal of Roman Studies 14 (1924): 93–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/296326.

Joseph, Satish. “‘Long Live the Republic!’ Father Edward Purcell and the Slavery Controversy: 1861-1865.” American Catholic Studies 116, no. 4 (2005): 25–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44194961

Kelly, Joseph. “Charleston’s Bishop John England and American Slavery.” New Hibernia Review 5,

no. 4 (2001): 48-56. https://doi.org/10.1353/ nhr.2001.0063.

Smith, Mark M. “Remembering Mary, Shaping Revolt: Reconsidering the Stono Rebellion.” The Journal of Southern History 67, no. 3 (2001): 513–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3070016.

Thornton, John K. “African Dimensions of the Stono Rebellion.” The American Historical Review 96, no. 4 (1991): 1101–13. https://doi.org/10.2307/2164997.

Kathleen. Flanagan, S.C. “The Changing Character of the American Catholic Church 1810–1850” Vincentian Heritage Journal 20, no. 1 (1999): 5 https:// via.library.depaul.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1211&context=vhj

Messmer, Sebastian. “Archbishop .” The Catholic Encyclopedia 1 (1907). https://doi.org/https://www. newadvent.org/cathen/01691a.htm.

Lippy, Charles H. “Chastized by Scorpions: Christianity and Culture in Colonial South Carolina, 1669–1740.” Church History 79, no. 2 (2010): 253–70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27806394.

Websites:

NCHE. Catholics in America, 2016. https://backstoryradio.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/ Catholics-Sources.pdf.

Panzer, Joel S. “The Popes and Slavery: Setting the Record Straight: EWTN.” EWTN Global Catholic Television Network, 1966. https://www.ewtn. com/catholicism/library/popes-and-slaverysetting-the-record-straight 1119.

“American Catholicism.” Site Search. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://pluralism.org/american-catholicism.

Mullen, Lincoln. 2013. “Maps of Catholic Dioceses in the US, Canada, and Mexico.” Lincoln Mullen. https:// lincolnmullen.com/blog/maps-of-catholic-dioceses-in-the-us-canada-and-mexico/.

Velázquez, Diego. n.d. “Western colonialism - Spanish Empire, New World, Colonization.” Britannica. Accessed May 19, 2024. https://www.britannica.

com/topic/Western-colonialism/Spains-American-empire

Boomer, Lee, and Eastman Johnson. 2023. “Antebellum - Women & the American Story.” Women and the American Story. https://wams.nyhistory. org/a-nation-divided/antebellum

“A Closer Look: The Purcell Brothers, Abolition and The Catholic Telegraph – Catholic Telegraph.” 2020. Catholic Telegraph. https://www.thecatholictelegraph.com/purcell-brothers-abolition-and-the-catholic-telegra ph/70302.

Black History - Ohio as a Non-Slave State.” n.d. Shelby County Historical Society. Accessed April 4, 2024. https://www.shelbycountyhistory.org/schs/blackhistory/ohioasanonslave.htm.

Resistance to the State. Accessed May 21, 2024. https:// www.lva.virginia.gov/exhibits/deathliberty/resistance/index.htm.

“Political Machine,” Encyclopædia Britannica, March 22, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/political-machine.

“Black Catholic History Timeline.” National Black Catholic Congress Website, October 18, 2021. https:// nbccongress.org/black-catholic-history-timeline/.

Onion , Amanda, Missy Sullivan, Matt Mullen, and Christian Zapata. “U.S. Slavery: Timeline, Figures & Abolition.” History.com, April 25, 2024. https:// www.history.com/topics/black-history/slavery.

“Our History.” Charleston Diocese, April 30, 2024. https:// charlestondiocese.org/about/our-history/.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Daniel O’Connell.” Encyclopedia

Britannica, May 11, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/ biography/Daniel-OConnell.

O’Brien, Shane. “Why Is Daniel O’Connell so Revered?” IrishCentral.com, August 6, 2022. https://www. irishcentral.com/roots/history/why-is-danielo-connell-so-revered.

Byrne, Julie. “Roman Catholics and Immigration in Nineteenth-Century America.” National Humanities Center, 2000. https://nationalhumanitiescenter. org/tserve/nineteen/nkeyinfo/nromcath.htm.

Books:

Geoghegan, Patrick M. King Dan: The rise of daniel O’CONNELL 1775-1829. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2010. Pg. 168

Sullivan, Francis Patrick. Indian freedom: The cause of Bartolomé de las Casas, 1484-1564: A reader. Kansas City, MO: Sheed & Ward, 1994.

Mishkova, Diana, and Balázs Trencsényi. European regions and boundaries: A conceptual history. BERGHAHN Books, 2018.

Brundage, David. Irish nationalists in America: The politics of exile, 1798-1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

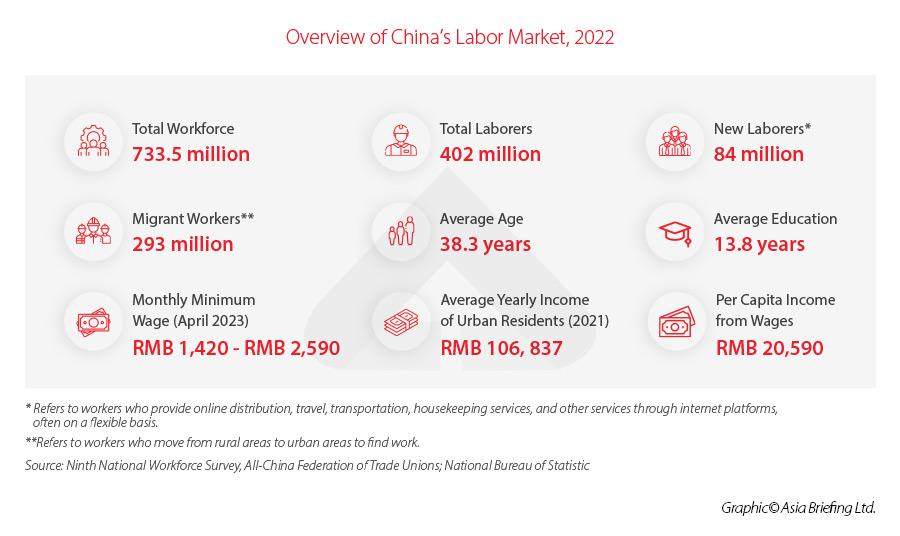

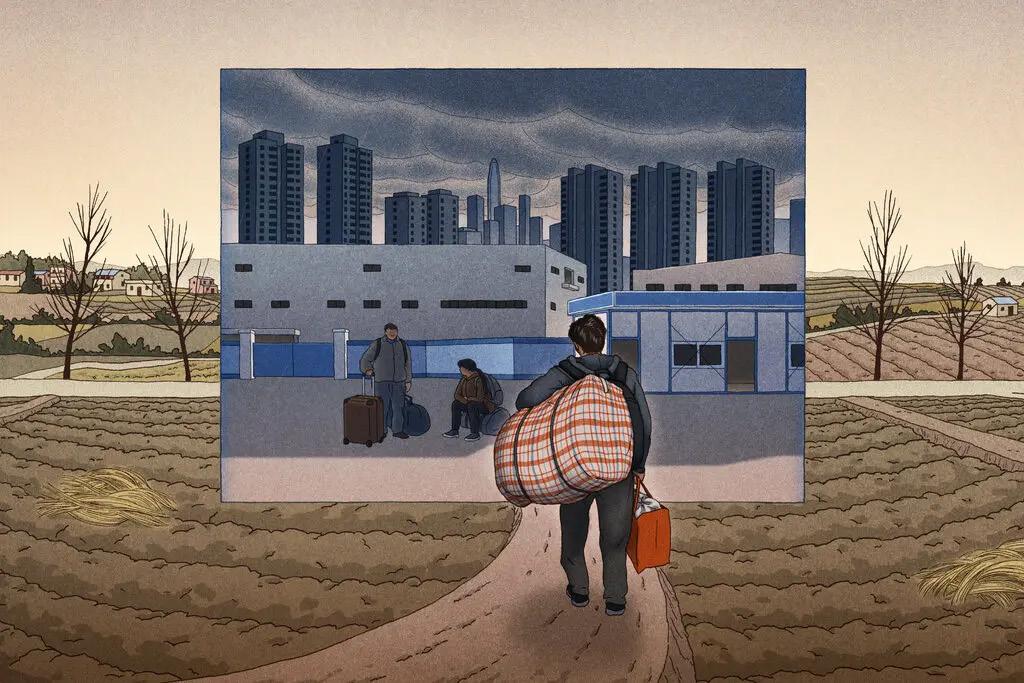

China’s Migrant Workers and the Curse of Hukou

Will Days ‘27

When labor issues in China come to mind, most people think about things like underage workers or unsafe working conditions,1 but one of the most significant labor issues in China today concerns the treatment of internal migrant workers. This paper deals primarily with migrant workers, explaining why a particular economic reform is needed to ensure that they are treated fairly, and outlining how better treatment of migrant workers will improve China’s economy in the 21st century.