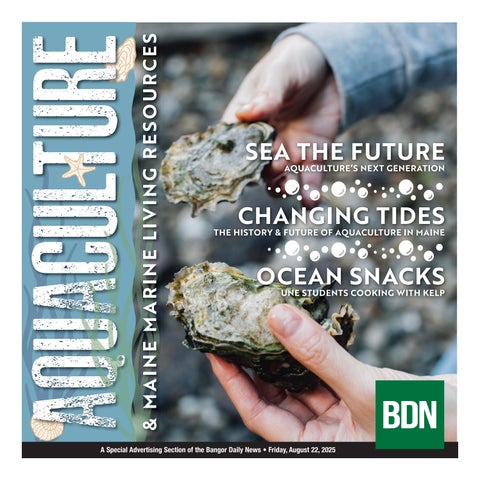

SEA THE FUTURE

AQUACULTURE’S NEXT GENERATION

CHANGING TIDES

THE HISTORY & FUTURE OF AQUACULTURE IN MAINE

AQUACULTURE’S NEXT GENERATION

THE HISTORY & FUTURE OF AQUACULTURE IN MAINE

UNE STUDENTS COOKING WITH KELP

BY HANK GARFIELD

Mayzie Corman may not have realized it at the time, but growing up on an apple farm and then moving to a Maine island provided the perfect foundation for a career in aquaculture.

Corman, 27, is a freelance farm hand and nursery technician for the Spartan Sea Farm Cooperative, a collection of small oyster farms in the Freeport area. When she was 10, her family moved from Cornish, Maine to Cliff Island in Casco Bay, where her parents ran the island’s general store for three years. The island’s year-round population is around 40.

“I went to fifth grade at the one-room school,” she said. “There were six students total.”

It was on the island that her love of the sea was born, and she eventually enrolled at the University of Maine to study marine biology. After spending some time out west, she returned to Maine, earned an associate’s degree from Southern Maine Community College, and delved into growing oysters and kelp.

“You have to know some science to do farming in general,” she said. “My ding-ding-ding moment, when I knew this is what I wanted to do, was when I saw that I could do science out on the water instead of in a laboratory.”

Corman enjoys the physical work of oyster farming, but she said there are many opportunities

for young people to become involved in all different facets of aquaculture.

“We need engineers, computer people, lab technicians, people with all kinds of different skills,” she said.

Aiden Coleman, 25, grew up in the greater Boston area. He first became interested in sea life while working for a tent company that delivered vinyl to the famed New England Aquarium for its sea turtle rehabilitation program. Coleman became entranced with the ancient marine reptiles and decided then and there to pursue a career on the water.

He’s in his third year of graduate studies at the University of Maine and works full-time at Norumbega Oysters in Edgecomb. His graduate thesis involves developing a species of scallops that can be readily grown and harvested.

Oysters dominate the aquaculture market, Coleman said, because they are hardy, and the infrastructure for growing them has been in place for some time.

“You can throw an oyster on the ground and come back 24 hours later, and chances are it will still be alive,” he said. “Scallops are a bit more delicate.”

What he likes best about his job is networking with new people and looking for innovative ways to produce seafood while being mindful of conservation efforts.

“I love being able to see the results of my work

every day. I like going home at night knowing I’ve done something to bring food to people in a sustainable way.”

Lily Hanks, 25, grew up in Massachusetts and graduated with a degree in marine biology from the University of Maine in 2021.

“I immediately moved back in with my parents and started waitressing at a restaurant in my hometown,” she said. “It was really hard to get a job during the pandemic.”

But her desire to work on the water eventually led her to a job at a Maine oyster farm.

“I had no experience with shellfish, I didn’t know how to drive a boat, and I didn’t know how to tie any nautical knots,” she said. “Other marine fisheries have such a history and tradition that it can be hard to get started if you aren’t born into it. It’s rare, outside of aquaculture, to be able to get your foot in the door at a young age.”

Hanks works as a nursery/hatchery technician at Muscongus Bay Aquaculture. The company supplies “seed” oysters to farms in Maine and beyond. She splits time between the nursery, hatchery, and two oyster farms on the Damariscotta River.

“I get to do the hands-on work on the water, and I get to scratch my science brain in the lab,” she said. “I see the whole life cycle of the oyster.”

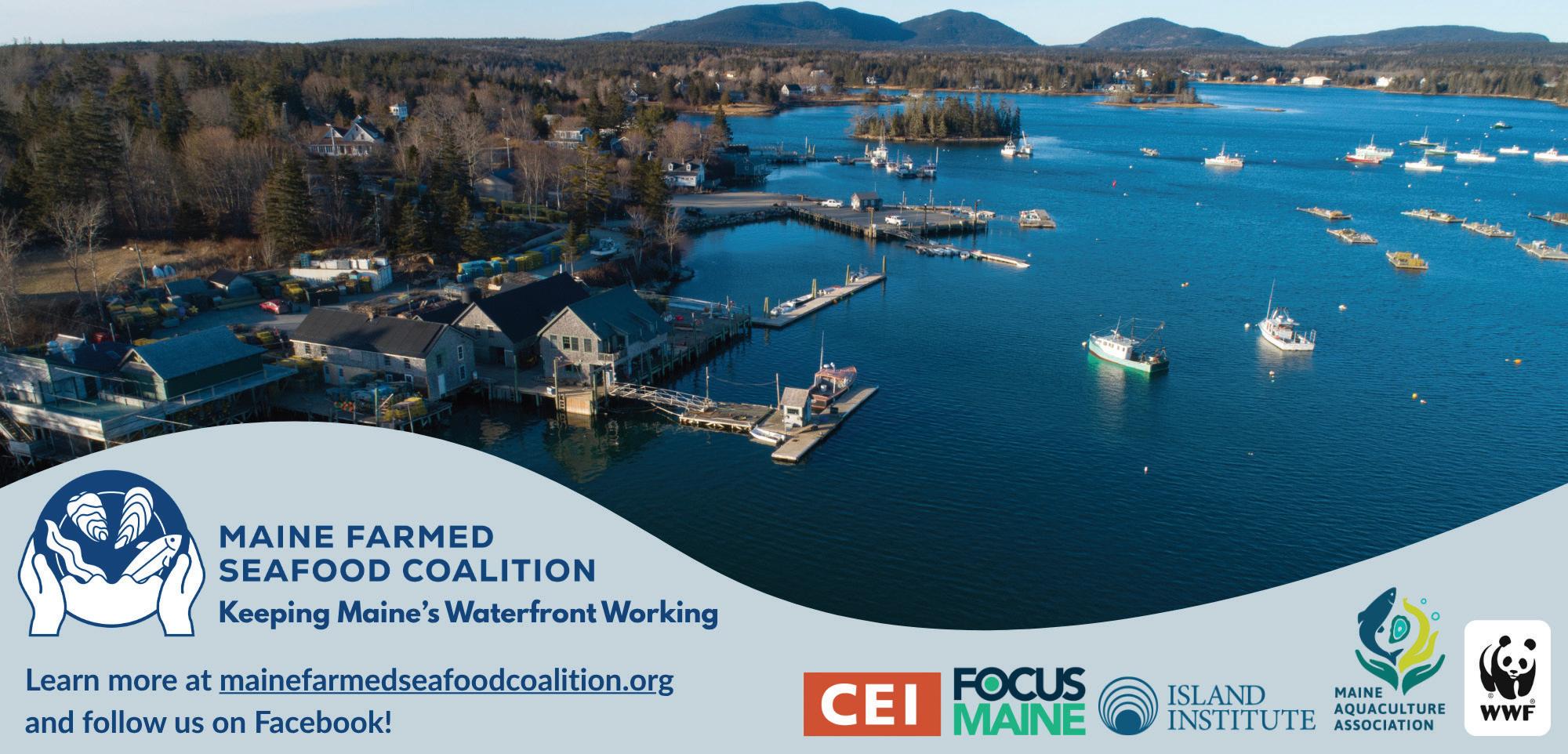

In March of 2025, the Maine Farmed Seafood Coalition (MFSC), was launched to support the Maine farmed seafood sector. Today the MFSC has over 35 companies, associations, and individuals working together to tell the compelling story of Maine farmed seafood and aquaculture. Our mission is to support sustainable seafood, strengthen coastal communities, and protect Maine’s working waterfronts by promoting the many contributions of farmed seafood to Maine families and communities: strengthening food supplies, reducing climate impacts, creating jobs and economic growth, and preserving the working waterfront.

Founded by FocusMaine, the Maine Aquaculture Association, World Wildlife Fund, Coastal Enterprises Inc., and the Island Institute, we are united in our commitment to Maine’s maritime economy, its rich coastal heritage, and the future.

Maine’s fishermen and sea farmers produce local, healthy, sustainable, and great-tasting seafood from the working waterfronts of many Maine coastal communities.

Maine’s farmed seafood is not just food—it’s a vital part of our state’s economy and a meaningful contributor to environmental health and coastal community resilience.

Yet, despite its promise, aquaculture is not sufficiently understood and sometimes faces opposition.

Here are some facts about aquaculture:

• Aquaculture directly supports over 1,000 jobs in Maine.

• 99% of Maine sea farms are family-owned.

• Farmed seafood helps to protect the ocean and relieves pressure on wild-caught fisheries.

• Maine’s aquaculture regulations are viewed worldwide as the gold standard for best practices and environmental protection.

• More Maine-based farmed seafood strengthens our food supply and ensures that the seafood we eat is produced locally according to our rules.

• Aquaculture improves the overall environment by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and protecting the quality of Maine waters.

Mainers want the facts about farmed seafood—and the people growing it. Of Mainers who are familiar with aquaculture, 8 out of 10 support the industry’s growth, with 6 out of 10 in strong support. 9 in 10 believe aquaculture can help strengthen working waterfronts and diversify coastal and rural economies.

Research shows that the more Mainers know about aquaculture, the more they support it and want to see more farmed seafood from Maine. Aquaculture in Maine

is not without its challenges, however. Timely and predictable regulatory decisions on aquaculture leases can give Maine sea farmers more clarity for their business planning and long-term operations success. And, as Maine’s coastline is impacted by climate change and changing home ownership patterns, aquaculture can partner with wild-caught fisheries to strengthen working waterfronts and address water quality challenges.

Maine’s future depends on our seafood economy, which is about more than what’s on your plate: it’s about the people who produced it.

As Maine’s aquaculture sector grows, here are some suggestions to become involved in advancing the potential of Maine farmed seafood:

• Learn more about the MFSC and its mission by visiting mainefarmedseafoodcoalition.org.

• Follow “Maine Farmed Seafood Coalition” on Facebook.

• Contact the MFSC via email at: mainefarmedseafood@gmail.com

• Ask your local officials to support responsible aquaculture practices.

• Support your local sea farmers by asking for and buying Maine farmed seafood.

Maine historical novelist Kenneth Roberts (1885-1957) wrote of a time when lobsters were so plentiful along the Maine Coast that you could walk along the shore at low tide and find them among the seaweed covering the rocks in the intertidal zone. Today, it takes a bit more effort, but Maine’s drowned coast has been a bountiful provider of seafood since the last glacier receded.

Ancient shellfish middens on outlying islands attest to indigenous peoples’ awareness and use of these resources. With modern harvesting methods came increased yields, the threat of overfishing, and the pressure of demand from a hungry world.

Enter aquaculture, the practice of farming the sea. By most accounts, the history of Maine aquaculture begins with the opening of the Craig Brook National Fish Hatchery in 1889. Established by Charles Atkins on an old mill site where the brook flows into Alamoosook Lake in the town of Orland, its mission was to raise Atlantic salmon in the face of an already noticeable decline of the species. For more than 100 years, the hatchery provided eggs and juvenile fish for many species of salmon to state agencies and private partners across the country. Today, the hatchery works to preserve the genetic integrity of seven river-specific species of Atlantic salmon, seeking to preserve the imperiled species for future generations.

Another milestone in Maine aquaculture occurred in 1965 with the opening of the Ira Darling Marine Center for Research Teaching and Service, commonly known as the Darling Marine Center, owned and operated by the University of Maine. Ira C. Darling was an Illinois businessman who purchased 148.6 acres of land in Walpole, on the shore of the Damariscotta River, in 1939 as a retirement home for him and his wife Clare. Darling became interested in tree farming and planted over 15,000 pine and spruce trees on the property.

When the annual trips to the Midwest and back became too difficult for the couple, Darling donated the land to the University of Maine as the site of a marine laboratory, funding it with the largest trust in the university’s history and endowed two chaired professorships.

Today, the Damariscotta River estuary, with cool, clear, nutrient-rich waters, is the heart of Maine’s booming oystergrowing business, producing some 80% of the state’s farmed oysters, and the Darling Marine Center is a primary spawning ground for young professionals entering the aquaculture industry. The center has expanded into a full marine research facility, with six faculty from the University of Maine’s School of Marine Science in residence. It has moved beyond just oysters to include research on biochemistry and microbial ecology, conservation science and policy, invertebrate biology and biodiversity, plankton ecology, and

BY HANK GARFIELD

oceanography. It attracts students and industry professionals from throughout New England and the world.

The Maine Aquaculture Association formed in 1978 as an advocacy group for the industry.

“We’re a trade organization,” said outreach and development specialist Trixie Betts. “We’re the oldest aquaculture association in the country. We act as an advocacy group for studies, resource development, and environmentally responsible business practices.”

In 1987, Maine developed the nation’s first environmental monitoring program for marine aquaculture, which led to the first integrated state and federal aquaculture permitting and monitoring process two years later. In 2000, the MAA adopted a set of guiding principles based on the United Nations’ guidelines for environmentally responsible aquaculture development. In 2010, MAA partnered with Maine Sea Grant, the Maine Aquaculture Innovation Center (MAIC), and UMaine’s Aquaculture Research Institute to create the nation’s first economic development plan for aquaculture.

“Maine is considered to have the gold standard for environmental regulations,” Betts said. “The working waterfront is an essential part of Maine’s history and identity. If we can keep coming up with sustainable ways to produce protein, we can carry that tradition into the future.”

COURTESY OF MAINE AQUACULTURE ASSOCIATION

Unless you’ve been living under a rock (or an oyster bed), you likely saw that the Maine Oyster Trail was recently featured in the New York Times, reaching over 100,000 readers in a single week. Created in partnership with Maine Sea Grant, the Oyster Trail is an interactive oyster tourism guide to Maine’s oyster businesses and experiences. While that story captured the beauty of enjoying oysters along our coast, it missed what’s truly transformative about the Trail: its role in strengthening Maine’s seafood economy, bolstering small businesses, and keeping our working waterfronts alive.

Since its launch in 2021, the Maine Oyster Trail has attracted over 5,800 users who’ve logged over 9,000 check-ins at oyster businesses.

“The Maine Oyster Trail has brought more visibility to small farms like ours, and given visitors a meaningful way to connect with the people and place behind the oysters,” reports Kelly Punch, Catering Event Manager at Mere Point Oyster Company. “Beyond boosting sales, it’s deepened our community connections and opened doors we never expected.”

In an effort to adapt to the challenges of the pandemic, many oyster farmers began selling oysters directly to consumers, offering farm tours, shucking lessons, and other oyster experiences to help diversify their businesses. The Maine Oyster Trail was born from this spirit of resilience, and it has grown into a national model for how aquaculture and tourism can work together.

“It’s been a crucial revenue generator during a pivotal period of the year for us,” says Cameron Barner of Love Point Oysters. “Operating oyster farm tours has been an excellent way for our small business to foster lifelong oyster enthusiasts and share our farm with the public.”

The real power of the trail lies in how it turns curiosity into connection—and revenue—not just for oyster farmers, but also for the many seafood wholesalers, boatbuilders, equipment suppliers, restaurants, and tourism operations who rely on a thriving waterfront economy. Maine’s identity is built around our working waterfronts and coastal

communities, which attract millions of people to our state every year. The Trail provides an opportunity for all those visitors to engage with the realities of those working waterfronts beyond the postcard, and come face to face with the hard work it takes to put seafood on our tables and the people we have to thank for it.

This kind of connection can only exist if working waterfronts do. The Maine Oyster Trail would not be possible without the infrastructure that supports our coastal economy. Behind every oyster slurped is a network of other businesses, wharves, and working people. Supporting this infrastructure is critical—not just for tourism, but for preserving Maine’s coastal identity and economy.

We’re thrilled the Oyster Trail is turning heads, and with that we also hope it engenders a greater respect for the essential working waterfronts that support it. “Maine’s future depends on our seafood economy, which is about more than what’s on your plate: it’s about the people who produced it.. Visit maineoystertrail.com to check out the trail!

COURTESY OF EDUCATE MAINE

It’s no secret that aquaculture is a growing industry in Maine – oysters, kelp, and other shellfish are showing up on menus and grocery store shelves across the state and beyond. But beyond tasting local oysters or taking a farm tour, how can someone turn their curiosity about marine science into hands-on experience in aquaculture?

Sixteen participants found their answer this summer through the fourth year of the Aquaculture Pioneers program – administered by Educate Maine and made possible by funding from Focus Maine in partnership with The Builders Initiative. This paid, summer-long experience provides a career exploration opportunity for participants who may have little to no practical experience, while also reducing financial burdens on small to mid-sized farms that need extra help during the busy summer months. Open to everyone from high school students to adults exploring a new career path, the program gives participants a chance to see what it really takes to work as a farmhand in this growing industry.

The program kicks off with a two-day, overnight “bootcamp” at the Boothbay Sea and Science Center. Pioneers come together to learn about the industry, meet leaders, and develop skills they’ll use over the summer. The agenda supports all experience levels, with sessions covering industry basics, oyster lifecycle, physical wellness, and farm ambassadorship. Participants also get hands-on practice with gear, knot tying, boat safety, and tours of local farms.

After bootcamp, Pioneers spend their summers at farms up and down the coast — from Beals to York, immersed in learning daily farm operations. Typical tasks include flipping oyster cages, sorting and tumbling oysters, harvesting, and helping to grow seed in hatcheries. Many also join their farms at summer community events, where they help out with shucking and share their new knowledge with the public.

For Lily Pierannunzi, a Maine Maritime graduate with prior experience on the waterfront, this was “the perfect next step after graduating and moving into the professional world.” The program also attracts participants from out of state. Alex Stutzer initially saw it as an opportunity to spend the summer away from Virginia’s heat on Maine’s coast — a natural extension of his experience in both agriculture and sailing. What started as a seasonal opportunity quickly turned into a deeper interest in Maine’s unique coastal environment and a growing curiosity about aquaculture as a career.

“Maine’s working waterfront has a culturally rich history,” Stutzer shared. “Participating in the Aquaculture Pioneers program afforded me the opportunity to experience that firsthand, with a built-in support system to ensure success in a career in aquaculture.”

If Pioneers feel that Aquaculture is truly the right fit for them at the end of the summer, there is a clear path forward. The Aquaculture Pioneers program is a certified pre-apprenticeship recognized by the Maine Department of Labor and linked to the nation’s only Registered Apprenticeship Program for Shellfish and Seaweed Aquaculture Technicians. Pioneers are guaranteed interviews for this competitive program and receive advanced credit if accepted. This pathway from exploration to apprenticeship plays a vital role in cultivating the next generation of skilled aquaculture farmers, supporting the long-term growth and success for the industry.

If you are interested in applying to participate in the summer 2026 Aquaculture Pioneers cohort, or if you’re a farm interested in hosting a Pioneer, visit mainecareercatalyst.org/aquaculture-pioneers or reach out to Meg@educatemaine.org.

ake two iconic, cherished classics of Maine’s children’s literature: Charlotte’s Web, by E. B. White, and One Morning in Maine, by Robert McCluskey. The first unfolds on a farm while the second captures the coastal life of a young girl and her father digging for clams. Both books resonate with themes of Maine and the journey of growing up in this beautiful state. But could there be a deeper connection between the books? After all, farming extends beyond land to the very shores of the sea.

Aquaculture, or ocean farming, presents a significant opportunity for Maine’s coastal communities and economy, and Maine has already established itself as a leader in sustainable farmed seafood. This sector not only connects local food systems and jobs to Maine’s rich culture and environment, but also embodies handson innovation and creative scientific exploration — ideal for engaging Maine students in meaningful, placebased educational experiences.

The Maine Aquaculture Innovation Center (MAIC) in partnership with Maine Sea Grant, the University of

Maine, the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, the Downeast Institute, and teachers across Maine, are developing a vision for integrating aquaculture into Maine schools. This initiative aims to foster engaged, knowledgeable communities while preparing students for jobs. Education begins at the K-8 level where students learn about aquaculture’s role in Maine coastal ecosystems, and progresses to high school where students explore various career pathways — from working on boats, to marketing products, and conducting research.

To support educators in incorporating aquaculture into their classrooms, MAIC and partners are creating hands-on, STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math) curricula that align with Maine learning standards. In 2023 and 2024 with support from the World Wildlife Fund and the USDA, MAIC successfully piloted the Kelp Curriculum for grades 4 to 6. Teachers statewide were introduced to this free, online resource and many have implemented the hands-on lessons. In Blue Hill, for example, Ms. Herrmann’s class explored seaweeds, tried

their hands at cooking with kelp, and discovered how kelp farming benefits ecosystems. With enthusiastic support from educators, MAIC and partners continue to engage Maine teachers in aquaculture education with funding from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), by hosting workshops, field experiences, and a summer teachers’ camp. The project team — which includes two outstanding teachers — is now developing a new curriculum focussed on bivalve aquaculture, which will serve as an additional free resource for Maine classrooms. With all of the innovation in aquaculture, it only makes sense to connect young, enthusiastic learners with emerging opportunities in their own communities. And what better way to do that than with a little ‘kelp’ from the teachers who know them best?

To access the free Kelp Curriculum, visit maineaquaculture.org/kelp_curriculum. For more information about MAIC’s other education projects, visit learn.maineaquaculture.org or reach out to us directly at learn@maineaquaculture.org

COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MAINE

Ascallop farm based in Belfast and co-owned by University of Maine alumnus Struan

Coleman was featured in the PBS documentary “Hope in the Water.” Coleman received his master’s in marine policy from UMaine in 2021, during which time he studied the economic feasibility of scallop farming in Maine and was introduced to one of the founders of Vertical Bay.

“Hope in the Water” is a three-part documentary series that highlights the stories of innovators, water farmers, and fishers working toward a sustainable future. Vertical Bay is featured in the second episode titled “Farming the Water,” as the story shows how the team at Vertical Bay sustainably farms scallops from seed to market size using Japanese techniques. The episode, which tells the origin story of scallop farming in Maine, received a 2025 Emmy nomination for outstanding science and technology coverage.

Vertical Bay’s episode featured Martha Stewart, who spent a day on the water farming scallops, and another one demonstrating how to cook them at her home on Mount Desert Island.

“Working with the ‘Hope in the Water’ team was an incredible experience,” Coleman said. “Our whole team at Vertical Bay was incredibly grateful for the opportunity to tell our story and highlight the ways in which dozens of researchers, farmers, and regulators have come together to build this new and exciting industry in the state. Getting to spend the day with Martha Stewart was also a once in a lifetime experience.”

(Right) University of Maine alumnus Struan Coleman chats with Martha Stewart for a PBS documentary about innovators, water farmers, and fishers working toward a sustainable future.

Coleman joined Vertical Bay, which was co-founded in 2017 by Andrew Peters, late in 2022. Today, the business employs two full-time crew members and sells scallops to home cooks and restaurants across the country. Vertical Bay is one of the companies in Maine working to commercialize research and development that has been led by institutions such as UMaine, Maine Sea Grant, and the Maine Aquaculture Association.

Maine is a leader in aquaculture, and the R1, sea-grant University of Maine plays a pivotal role in growing the industry and ensuring the state continues to be a global competitor in the Blue Economy. Programs and partnerships led by faculty and staff in the School of Marine Sciences and Cooperative Extension solve industry challenges and prepare the future workforce. World-class facilities such as the Aquaculture Research Institute, the Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research, and the Darling Marine Center support the sustainable use of ocean and coastal resources through experiential student learning, cutting-edge research and industry collaboration. For more information, visit umaine.edu

From afar, the series of 100-meter rings that constitute an Atlantic salmon farm site in the Gulf of Maine appear unchanged since the transition from steel cages to highdensity polyethylene pens in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Atlantic salmon aquaculture has been practiced in Maine since the late 1970s and early 1980s, with the first commercial lease being issued by the Maine Department of Marine Resources for a farm site in Cobscook Bay near Eastport in 1982. The industry has evolved and modernized tremendously since then, with the adoption of precision farming defining the last 20 years or so.

So what is precision farming? Also known as precision agriculture, precision farming refers to the use of advanced technologies and data analysis to optimize farming practices. Farmers who embrace precision farming, in theory, increase efficiency and productivity and minimize environmental impact.

For aquatic farmers, that translates to more precise and scalable ways to feed fish and to monitor fish health and growth, ocean conditions and water quality.

Cooke USA has been farming Atlantic salmon in Maine since 2004, celebrating 20 years of aquaculture operations in the state last year. Today, Cooke USA’s operations consist of marine farm sites in Downeast Maine, a processing plant in Machiasport, and three land-based freshwater hatcheries in both the eastern and western parts of Maine. Its fresh farmed Atlantic salmon is sold at supermarkets and restaurants throughout New England and the United States. It was around the early 2000s that the company, and the industry by and large, began embracing precision farming. It’s what a passerby on a boat or an onlooker from the shore can’t see that’s revolutionizing Atlantic salmon aquaculture in Maine and globally — hardware such as underwater cameras and sensors, which have been used for years, and the AI-enable software behind the hardware.

Case in point is feeding. For finfish aquaculture, one thing remains constant — feed amount and timely feeding are critical to the success of a farm. Feed represents around 50 percent of a farmer’s costs. Overfeeding leads to higher ammonia levels, which can negatively impact the environment. Underfeeding leads to slow fish growth. Forty years ago, fish were fed manually by hand from a barge, with no visibility beneath the surface. Years later, barges were equipped with blower-based systems, allowing fish in multiple pens to be fed simultaneously.

Next came underwater cameras. Farmers observe feeding behavior and stop feeding when fish stop eating, resulting in better fish health and less uneaten feed. Then came oxygen and temperature monitoring. Today, farmers are aligning environmental conditions with optimal feeding schedules, further minimizing the environmental impact.

Feeding is far from the only practice that Cooke is embracing with precision farming. For Cooke’s operations in Maine, Atlantic Canada, and Scotland, an AI-enabled system is being piloted to monitor individual fish in pens in real time, executing tasks such as measuring fish weights and monitoring fish health, giving fish health technicians more time to analyze data.

In Maine and Atlantic Canada, Cooke is trialing an AIenabled smart measuring system for algae detection. The system monitors and identifies microscopic algae species in real time, categorizing densities and identifying species as harmful or harmless. Benefits include faster and more accurate detection of harmful algae blooms around the clock, giving farm managers time to mitigate the effects before fish are harmed by algae blooms. It’s yet another tool in the fight against climate change.

It doesn’t stop there. Seal predator detection and deterrent and net cleaning are also among the practices where precision farming is being applied in aquaculture.

Globally, Maine represents only around 1 percent of Atlantic salmon production. But the state can have — and

is having — an outsized effect on the advancement of aquaculture abroad. Over the years, Maine has been a hotbed for aquaculture research and development, and numerous innovative, pioneering farming practices were developed in the state, embraced by Cooke USA and adopted by sea farmers worldwide. These practices include the introduction of farm site rotation and fallowing, development of the world’s first containment management system, and introduction of non-chemical animal health support systems, all done in cooperation with state and federal regulators, academia, and environmental and nongovernmental organizations.

All these advancements have enabled salmon farming to become one of the healthiest and most efficient ways to feed the population with minimal environmental impact, the lowest freshwater use, and one of the lowest carbon footprints of any animal protein.

Cooke operates in full compliance with the laws set forth by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection, the Maine Department of Marine Resources, and its operating permits. Salmon farms are routinely inspected by state regulators and subject to regular monitoring reports. These laws are designed to protect Maine waters as well as Maine’s heritage fisheries.

Finfish aquaculture has coexisted with lobstering in Maine waters for more than 40 years. Lobster landings are not negatively affected by Atlantic salmon farms. In fact, lobster gear is set alongside and within aquaculture lease boundaries.

By capitalizing on precision farming and embracing the tools needed for more precise and scalable ways to feed fish and to monitor fish health and growth, ocean conditions, and water quality, Maine can continue to be a nest for Atlantic salmon-aquaculture research and development among strong working waterfronts in rural coastal communities.

Senior Production & Operation Manager- Eastport

Hatchery Technician - Gardner Lake Hatchery, East Machias

Fish Processors - Machiasport Processing Facility

Maintenance Technician - Machiasport Processing Facility

BY JULIA BAYLY

Since gaining a foothold in the state a half century ago, Maine’s aquaculture industry has been on an upward trajectory. Based on economic and other key indicators, it’s showing no signs of slowing down in meeting ever-changing demands.

More recently, those in the sea-based industry are adapting to shifting food trends and the increasing impacts of climate change in the Gulf of Maine.

“It’s really an amazing new frontier using a lot of things central to and traditional to Maine’s identity,” said Trixie Betz, outreach and development specialist with the Maine Aquaculture Association. “Our working waterfronts are such a central part of Maine culture and [aquaculture] allows people to pursue careers on the waters in new ways.”

Those ways may be new, Betz said, but they are based on generational skills going back decades.

Maine has seen steady growth in this industry. The total economic impact of aquaculture nearly tripled from $50 to over $137 million from 2007 to 2014, according to the Maine Aquaculture Association’s most recent data. It employs over 700 people full-time at nearly 200 farms along the coast.

Annual sales of those farmed seafood products reach $110 million annually and predicted growth in the industry of 2 percent a year. That prediction could be confirmed later this summer when the association releases its most recent census data.

Certainly the country’s appetite for food from the oceans is not slowing down. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, Americans consume 20.5 pounds of seafood annually per capita. Based on the 2023 United States census data, that’s a staggering 6.867 billion — with a ‘B’ — pounds of shellfish and finfish eaten every year.

“Americans want to eat seafood,” Betz said. “Mainers want to grow the best seafood for people in the state and around the country.”

Doing so will help put a dent in the 85 percent of the country’s seafood market that is supplied from other countries.

“It’s so valuable to grow this seafood in our own backyard,” Betz said. “It’s coming from people you know.”

The overwhelming majority of Maine’s seafood industry revolves around lobster, that iconic state crustacean tourists gobble up by the plate — or lobster roll bun-full. According to the Maine office of tourism,

more than 50 percent of those visiting Maine in 2021 said they specifically came to eat lobster.

Lobster fishing in Maine goes back to the 1600s and is one of the oldest continually operated industries in North America. Maine remains the largest lobster-producting state in the nation.

But changes are on the near horizon. And it wasn’t always about lobster.

“Lobster as sort of that mono crop is really a new thing,” Betz said. “In decades past Maine had a really big wild ground fish industry with cod, halibut, and sardines.”

As those stocks dwindled over the years, lobsters rose in importance and monetary value. It’s a $1 billion annual industry, according to a 2018 study by Colby College.

“But it’s risky to have all your eggs in one basket,” Betz said. “Especially since the Gulf of Maine is warming so fast.”

Annual sea surface temperatures have increased at a rate of 0.84-degrees Fahrenheit every decade between 1982 and 2024, according to The Gulf of Maine Research Institute. That rate of warming is nearly triple that of the world’s oceans. Those warming waters are forcing some species — like lobsters — to move northward out of Maine fishing grounds to find cooler waters.

That’s where aquaculture comes in.

“Having something to hedge our bets and return us to our roots in terms of fishermen harvesting multiple species throughout the year is key,” Betz said.

That has some lobstermen and women, along with newcomers to Maine’s coastal waters, farming kelp, oysters, mussels, seaweed, scallops, clams, trout, halibut, and green sea urchins. In many cases, these farmed species create year-round income for the traditional fishing enterprises. Lobster, for example, is fished and sold in the summer. Kelp is a winter crop.

“The kelp can be harvested and sold in the spring when the lobster fishers normally don’t have an income at all,” Betz said.

In addition to the economics, Betz said aquaculture is providing cultural and environmental wins for the state.

“It builds on the strong generational knowledge and traditions of our working waterfront,” Betz said. “It’s also a great frontier for entrepreneurs or people wanting to work on aquaculture farms. It attracts those who want to work outside in a sustainable industry with green jobs.”

Betz is well aware these new aquaculture ventures represent some big changes for Maine’s working waterfronts.

“Change is hard and there are people who are uncomfortable with it,” she said. “But if you think about the alternative, we risk losing the working waterfronts of Maine.”

Among those threats is the so-called gentrification of small coastal communities. Housing prices have been steadily rising along the coast, especially since COVID when people fleeing bigger New England cities discovered waterfront property in Maine was affordable. That phenomenon has led to opportunities for longtime property owners to sell at prices far above those possible even a decade ago and pricing out local buyers.

“If there are no opportunities for working and preserving the waterfronts, they will be lost,” Betz said. “No one wants that.”

Moving forward Betz sees aquaculture in Maine responding to challenges on two major fronts — globally and nationally.

“I think we are being proactive in terms of the U.S.,” she said. “We already have some of our 3,500 miles of coastline, 3.5 acres of state water, strong traditions, and workers that can all help us succeed.”

Most of Maine’s coastal communities have a generational understanding of what it means to work on the water, Betz said.

“We have been proactive in setting the bar on regulations for growing our products and assuring growth is sustainable,” she said. “We know we are doing it right and not just throwing things out there to see what happens.”

As far as reducing seafood imports, Maine is playing more of a catch up game.

“There are so many other countries that are really ahead of Maine,” Betz said. “So we are hoping to catch up to meet U.S. demand.”

A big part of that is ongoing cooperation among those in aquaculture, neighboring residents, regulators, and politicians all working together.

“Before any regulations are put in place, there are open discussions between everyone involved to get opinions,” Betz said. “We want any conflict worked out before any laws are on the books [and] it’s a very transparent process.”

That is going to help everyone involved in aquaculture grow the changing fishing industry together despite any local, national, or global challenges.

“Sure, in terms of our working waterfronts we could keep our heads in the sand,” Betz said. “But sooner or later the tide comes in.”

COURTESY OF MAINE SEA GRANT

On the coast of Maine, whether you’re munching on lobster, haddock, or a seaweed salad, you’re supporting the time-honored traditions of those who make their living from the sea. Maine’s seafood community is bursting with the ingenuity needed to keep up with the ecology and economy of an ever-changing world. Maine Sea Grant’s long-term collaborations with fishermen, sea farmers, regulators, researchers, and community leaders help strengthen Maine’s fisheries and aquaculture sectors. As a federal-state partnership between NOAA and the University of Maine, our team is connected to a national network of 33 other Sea Grant programs in coastal states, Puerto Rico, and Guam, bringing a broad perspective to address local needs.

What does that look like in practice for Maine’s seafood economy? When anyone in the industry reaches out to Sea Grant staff for support, they’re tapping into a network of hundreds of extension professionals around the country, and in some cases, a global aquaculture community. Whether we are working with Maine’s farmers to develop new seafood products, adapt to rapid environmental change, or diversify their businesses, we draw upon expertise and resources from around the world. In the words of a Casco Bay oyster farmer, “The generosity of the Maine Sea Grant team in knowledge transfer and introductions is one huge reason why our aquaculture community is so strong.”

How do Sea Grant staff gain national and global perspectives? We participate in knowledge exchanges. For example, traveling to Japan to investigate scallop growing techniques or South Korea to glean ideas for how to strengthen Maine’s seaweed industry. We bring this knowledge home and work directly with farmers to apply methods that work best for Maine’s coastal communities. We also host experts and others eager to learn from our state’s reputation for providing safe, sustainable seafood.

What are some great examples of our work? The Maine Oyster Trail, recently featured in the New York Times, is an example of Maine Sea Grant’s work to connect people from elsewhere to Maine’s aquaculture industry. Maine Sea Grant established the Trail more than a decade ago, and worked with the Maine Aquaculture Association to launch an expanded version during COVID. The current version features 93 farms and businesses providing interactive oyster experiences like kayak tours, learn-toshuck classes, and opportunities to buy directly from farmers. With nearly 6,000 registered users, the Trail serves both locals and visitors looking to experience all that Maine’s oyster community has to offer.

Alongside partners across the state, we also provide training and professional development opportunities so that Maine’s small business owners and farmhands have the skills and knowledge they need on the water. In the words of a Downeast oyster farmer, “Mainers rely on our working waterfronts for jobs, food, culture, and sustainability. Maine Sea Grant helps us to thrive.”

Fishing and farming are all about solving problems and looking for new opportunities. As Maine’s sea farmers face these challenges and opportunities head on, we strive to connect them with the science and knowledge they need.

BY WANDA CURTIS

University of New England students are engaged in an exciting project which involves the production and marketing of seaweed (kelp) snack bars. The cranberry-almond-kelp bars were first created and marketed by the former owners of the SeaMade Seaweed Company in 2016. Last year, they gifted the company to UNE with the intention of students taking over the production, marketing, and distribution of the SeaMade Bars.

According to UNE communications specialist Deirdre Stires, the limited availability of processed seaweed made it difficult for the former owners to meet wholesale demands for the product. The co-owners decided “gifting their company to UNE was the perfect way to keep the company founded on sustainability viable, especially with the students growing the kelp in their aquaculture classes,” Stires shared in an article on the UNE website.

Stires said that the owners were excited by the idea that students could work on new nutritional and flavor aspects and take the product to the next step.

The UNE SeaMade project kicked off last August with a demonstration production run involving UNE faculty and staff and former owners Tara Treichel and Mark Dvorozniak. This past year, a team of six students, enrolled in several different UNE programs, have been collaborating on the project using existing recipes and also testing new recipes.

SeaMade Bar mentor Megan Letendre said the current recipe for the bar follows the flavor profile developed by its founders. That includes cranberries, almonds, honey, and kelp. She said the team has also experimented with two other flavor profiles, including blueberries and pecans. They plan to use ingredients from as many local sources as possible. Honey will be sourced from UNE beehives, Letendre said.

SeaMade bars are prepared in the UNE Teaching Kitchen on the Biddeford Campus in August 2024.

– PHOTO COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW ENGLAND

“Our long-term goal is to source as many ingredients as possible from Maine and our own campus, reflecting our commitment to local sourcing and sustainable food systems,” she said.

According to UNE Associate Professor Carrie Byron, Ph.D., the kelp used in the bars will come from UNE’s largest aquaculture farm site in Casco Bay that is leased with the Maine Department of Marine Resources. UNE is licensed by the state of Maine to harvest kelp.

Once the project is operating at full scale, Letendre projects UNE students will need to produce several thousand SeaMade Bars annually to meet the anticipated demand on the campus. The bars are made in the UNE Teaching Kitchen under the supervision of Emily Estell, M.P.H., an assistant clinical professor of nutrition. The kitchen is located on UNE’s Biddeford campus.

Seaweed snacks have become increasingly popular throughout the world because of their nutritional benefits. The owners of Maine Coast Sea Vegetables, a Maine company that markets North Atlantic sea vegetables and products nationwide, have described seaweed as “a nutritional powerhouse.” They report, on their website, that sea vegetables (edible forms of seaweed) contain almost all 24 minerals and trace elements required for the body’s physiological functions, some of which “greatly exceed quantities found in land plants.” They note that sea vegetables are also one of the best natural sources of dietary iodine.

The general manager of Maine Coast Sea Vegetables, Seraphina Erhart, said seaweed is a “functional food,” meaning that “it has health benefits beyond basic nutrition.” She said that seaweed has unique polysaccharides not found in land plants.

“These all have bioactive properties such as regulating blood sugar levels and have anti-cancer and anti-viral effects,” she said.

Including seaweed in your meals is a simple way to nourish your body and enjoy the benefits of the ocean’s bounty.

Pursuing a career in Maine’s mariculture industry is an excellent choice due to the state’s abundant natural resources and commitment to sustainable practices.

Maine’s coastal waters are perfect for cultivating high-demand seafood such as shellfish and seaweed, which are increasingly sought after both locally and globally. The industry’s focus on environmental stewardship and sustainable aquaculture ensures a forward-looking career path aligned with ecological preservation. Additionally, with continuous advancements in technology and a supportive professional community, Maine’s aquaculture industry offers exciting opportunities for innovation and growth.

Local expert Carter Newell has created a Mariculture Certificate program designed to provide aspiring professionals with essential skills for success in shellfish or sea vegetable farming. An industry professional with 40 years in shellfish farming, Dr. Newell has dedicated his career to mussel and oyster cultivation and advancing Maine’s mariculture industry. This program provides a strong foundation for those looking to start their own business or work as an employee or manager in an established sea farm or seafood business.

With modular scheduling and convenient hybrid learning there’s no need to leave your current job to join the fastest-growing sector in the marine industry. Learn more and register at mainemaritime.edu/cpmd/mariculture/ or call (207) 326-2211.