Barnard Columbia Urban Review Fall 2022 Issue

Life around the Fulton Street Ferry and the Brooklyn Bridge: A Comparative Study of Brooklyn Heights and DUMBO 7 By: Olivia Cull

Life around the Fulton Street Ferry and the Brooklyn Bridge: A Comparative Study of Brooklyn Heights and DUMBO 7 By: Olivia Cull

Co-Editors-in-Chief: Margaret Barnsley BC ’24 & Victoria Tse BC ’24

Events Coordinator: Gigi Silla BC ’24

Layout Editor: Samuel George GS ’23

Publicity Director: Nyah Ahmad BC ’24

Treasurer: Ellie George BC ’23

Isa Alberola BC ’23

Karen Chavez BC ’24

Avery Ransom CC ’24

Araiya Shah BC ’24

Olivia Canterbury CC ’25

Ben Erdmann CC ’25

Elijah Horn CC ’25

Lola Rael BC ’23

Sanya Verma GSAPP ’23

Alice Warden BC ’23

Jennifer Guizar Bello BC ’24

Ben Erdmann CC ’25

Fiona Campbell BC ’23

Christina Duan BC ’23

Maya Felstehausen BC ’25

Alex Crow CC ’25

Olivia Delgado BC ’25

Unathi Machyo BC ’24

Celeste Ramirez BC ’24

Karen Jia Hui Zhang CC ’26

Clay Anderson CC ’23

Olivia Cull BC ’24

Sungyoon Kim CC ’24

Grace Li BC ’24

Yetlanezi Martinez BC ’24

Noelle Hunter CC ’22

It is our honor and pleasure as the Co-Editors-in-Chief to present the fourth issue of the Barnard-Columbia Urban Review. This Fall, BCUR has taken great strides in organizing events for urbanists on campus to gather. Highlights of the semester include our welcoming night at Hex & Co, our movie night screening La Haine, and our two-part, place-based writing workshops led by writer and activist Sarah Butler.

Our cover artist for this issue is Noelle Hunter, whose brilliant painting captures the complexity, collaboration, and cohabitation that inherently exists within urban spaces. Featuring a ferry to the side as a nod to Olivia Cull’s “Life around the Fulton Street Ferry and the Brooklyn Bridge” published in this issue, in combination with the photographs taken by Grace Li that capture parts of our cities at a standstill, come together to form an amalgamation of how we view and interact with the urban spaces that we live in.

Clay Anderson’s piece “The Dangers of Delivering” offers a thorough and engaging look into the everyday violence deliveristas face in their front-line work of delivering food by bike. His scholarship is deeply illuminating and utterly convincing of the need to expand protected bike lanes. Grace Li’s photography offers beautiful and evocative images of New York from many vantage points. Sungyoom Lim’s photography offers similarly beautiful compositions of New York, this time highlighting a few of the city’s greenspaces, including the New York Botanical Gardens located in the Bronx and Central Park. Finally, Yeltanezi Martinez offers her rendering of “vertical layering,” showing readers an intricate maze where outside viewers are aware of the pattern, but inside participants are not.

This issue of BCUR would not be possible without the hard work and dedication to workshopping and creating the journal from start to finish. We owe our thanks to everyone who submitted their written and art/visual works, our peer reviewers, the staff and board of the journal, all of our general members, the faculty and staff of the Urban Studies department, the administrative staff of SEE, every past BCUR member, and countless other individuals who have made undergraduate urban research a reality at Barnard and Columbia.

As always, we welcome and encourage feedback and participation in the future of BCUR, and we sincerely hope that you enjoy this issue.

Sincerely, Margaret Barnsley

Co-Editor-in-Chief | Barnard College ’24 Victoria Tse

Co-Editor-in-Chief | Barnard College ’24

On May 24th, 1883, after thirteen long and tedious years of construction, the majestic Brooklyn Bridge was officially completed (McCullough 2012, 1). On its opening day, a reporter for the New York Times wrote, “It is estimated that over 50,000 people came in by the railroads alone, and swarms by the sound boats and by the ferry boats helped to swell the crowds in both cities” (The Learning Network 2012). The Bridge represented Brooklyn’s identity as the third-largest city in the United States at the time one that was actively developing into a booming industrial hub. Nearly everyone viewed the Bridge as a positive addition to the area. Manufacturers based in Lower Manhattan could efficiently store their goods on the spacious Brooklyn waterfront, commuters could travel without the stress of bustling crowds and weather-related hazards associated with the ferry, real estate developers understood the potential of the expansive vacant lots and farmland farther inland, and tourists could enjoy what Brooklyn Bridge engineer John Roebling called “a great adventure between the two cities” (McCullough 2012, 1). Individuals involved in the ferry industry were decidedly less in favor of the bridge. Although the Bridge revolutionized the relationship between Brooklyn and Manhattan as the first physical structure to connect the two cities, the land on and around where it was built had been bustling with commuters for nearly 200 years. Ferry transport running between what is now Fulton Street on both sides of the East River dates back to Dutch colonization of the Brooklyn coastline in the mid-1600s (Reiss 2001). The ferry’s instrumental legacy contributed to the development of two adjacent neighborhoods long before the Brooklyn Bridge was even an idea; today, we know these neighborhoods as Brooklyn Heights and DUMBO.

Despite their geographic proximity, Brooklyn Heights and DUMBO developed into distinct enclaves of industrial and residential life. Directly to the East of Fulton Street and the new bridge, Brooklyn Heights, previously known as Clover Hill and Brooklyn Village, flourished as the first “commuter suburb” in the United States. In the 1800s it was home to some of the biggest names in New York history: Mayor Seth Low, Minister Henry Ward Beecher, Tammany Hall politician William Marcy Tweed, and Brooklyn Bridge engineer Washington Roebling (The Learning Network 2012). To the West lay the neighborhood that is now known as DUMBO. Before this, it had taken on many names, including Olympia in the late 1700s and Gairville in the late 1800s. In 1890, DUMBO was a booming industrial hub with a relatively small residential population, most of whom lived in tenement-style housing.

How did the built and social environments of these two neighborhoods develop in such markedly different ways during the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, despite their equal distance from the Fulton Ferry? Firstly, DUMBO’s comparatively lower elevation attracted industrial growth, while the plateau of Brooklyn Heights provided geographical separation from waterfront industries and attracted wealthy homeowners. Secondly, a small pool of real estate developers capitalized on the industrial potential of DUMBO and the residential potential of Brooklyn Heights, shaping the built environment of each neighborhood to maximize profit and influence. Thirdly, between 1880 and 1910, a growing immigrant population adjacent to the Bridge and West of DUMBO supported industrial growth by working as factory operatives and laborers, while Brooklyn Heights remained a largely nativeborn enclave (Baics et al. 2021).

To understand the development of the two neighborhoods, it is crucial to follow the story of Fulton Street and the Ferry. In 1642, shortly after the Dutch colonization of Canarsie land along the Brooklyn coastline, farmer Cornelius Dircksen established the first ferry service between Manhattan and Brooklyn with the primary goal of connecting agricultural workers to the New York marketplace (Brooklyn Waterfront History 2014). The constant flow of resources via the transportation of passengers, livestock, game, and produce attracted settlers to the shore. The first main street in Brooklyn, King’s Highway (which is now Fulton Street), was laid out in 1704 off of the “low watermark at the ferry” (Everdell and MacKay 1973). The next significant industrial development in the area occurred after the Revolutionary War in 1787 when Joshua and Comfort Sands purchased the land around the Ferry and laid out a set of streets around King’s Highway to form “Olympia,” which is now part of modern-day DUMBO (The Bowery Boys 2022). Around the same time, engineer Robert Fulton developed the world’s first successful steamboat. In 1814, he established a steam-powered ferry to traverse the East River between what is now Fulton Street in both Brooklyn and Manhattan (Everdell and MacKay 1973). His contributions to the Brooklyn waterfront prompted significant growth in the local population: between 1793 and 1830, the number of Brooklyn residents skyrocketed from a mere 1,703 to 15,000, and included merchants, professionals, laborers, and immigrants migrating from Manhattan (Everdell and MacKay 1973). By 1835, developers widened Fulton Street to accommodate the everincreasing traffic to and from the ferry.

In 1853, the Union Ferry Company bought Fulton’s business as well as several other ferry businesses in the area and constructed a central terminal at 1 Water Street, which is shown in Appendix A, figure 1 (Everdell and MacKay 1973). Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont, a prominent investor and landowner in Brooklyn Heights, was a central figure in the Union Ferry Company, having aligned himself with Robert Fulton decades earlier as an ardent supporter of the ferry business. Pierrepont knew that increasing access to Manhattan would attract wealthy landowners who worked in Lower Manhattan but disliked its crowded living environment. Between 1860 and 1863, the Union Ferry Company built ten new boats and invested millions in ferry houses along the coastline. These investments, spearheaded by Pierrepont, paid off; by 1870, the ferry system accommodated 15 million commuters annually. Appendix A, figure 2 illustrates the increase in coastline infrastructure during the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1874. Post-1883, the coastline continued to accommodate industries moving in along the water, including the New York Dock company, which is a primary feature of the map in Appendix A, figure 3, from 1906. Famous poet, Walt Whitman, whose office overlooked the Fulton Terminal, described the area as “an incessant stream of people clerks, merchants, and persons employed in New York on business tending towards the ferry” (Everdell and MacKay 1973).

As a result of differing mean elevations, Brooklyn Heights and DUMBO began to separate morphologically and demographically at the turn of the 18th century and would continue to diverge throughout the 19th century. When landowners Joshua and Comfort Sands established a street grid for Olympia (present-day DUMBO) in 1787 with Main Street as its spine, they expressed hope that the area would develop into a summer colony for New Yorkers to “enjoy the river breezes” (Goldberger 2021). In 1800, the Brooklyn Mayor, General Jeremiah Johnson, noted that Olympia’s proximity to the water’s edge made it superior to Brooklyn Heights, which was located on a bluff and would be difficult to expand and innovate as the population grew. He wrote, “Olympia must receive the whole progress which otherwise would be given to Brooklyn Heights” (Goldberger 2021). He also described the layout of the village: “Olympia is extremely well calculated for a city: on a point of land which presents its front up the East River, surrounded almost with water, the conveniences are almost manifest. A pure and salubrious atmosphere, excellent spring water, and good society are among a host of other desirable advantages…” (Goldberger 2021).

Indeed, as demonstrated by the maps in Appendix B, the topographical layout of Olympia allowed for efficient growth as Brooklyn’s population expanded. Figure 1 in Appendix B compares the location of 1880 dwellings to modern-day elevation in meters (Baics et al. 2021). It shows that Fulton Street slopes slowly upward from the coastline, which likely accommodated an easy commute on foot or via horse-drawn cart from more elevated areas of Brooklyn. DUMBO’s elevation only surpasses 30 meters on the block encompassed by Water, Plymouth, Main, and Washington Streets, adjacent Empire Stores. The majority of its blocks have an elevation between 9 and 22 meters. The lowest areas of DUMBO are West of Pearl Street and close to the coastline, which in 1880, was home to industries such as Allen’s Agricultural Imports Factory and Howard & Fuller Brewery, and in 1906, to E.W. Bliss & Co. and Arbuckle Coffee Company. Figure 1 demonstrates only a slight increase in elevation at the Southern border of DUMBO, indicating that it was seamlessly connected to greater Brooklyn (Baics et al. 2021).

On the other hand, Brooklyn Heights is aptly named; traveling south of Fulton Street and the bridge, mean elevation increases from 15 to 44 meters over a span of two blocks, peaking on the cross-sections of Hicks and Pineapple Streets. It retains a high elevation (between 31 and 36 meters) going Southwest along Henry Street but declines more gradually to the Southeast parallel to Fulton Street below Sands Avenue. These sharp elevation changes are foundational to the identity of Brooklyn Heights (Baics et al. 2021).

General Johnson’s conviction that Olympia would become a residential hub was never made a reality (Goldberger 2021). Because of its more favorable location on the waterfront, Olympia was a prime location for industrial, not residential development. The name “Olympia” receded into history, leaving the area without an official or even colloquial name until the late 1800s (Goldberger 2021). Although both neighborhoods attracted industries along the coastline, the vast majority of Brooklyn Heights’ factories are located in areas of low-elevation within a block of the East River.

Unlike General Johnson and the Sands Brothers, Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont knew that the area of Brooklyn Heights was prime real estate. Instead of viewing the bluff as a limitation, he saw it as an opportunity to appease wealthy business owners with an inclination to settle farther from their places of work. In the early 1800s, he bought 60 acres of land in what later became South Brooklyn Heights, and advertised the area as having “all the advantages of the country with most of the conveniences of the city” (Sullivan 1970). He

correctly predicted that the steam ferry would have a revolutionary impact on the accumulation of population and wealth near the Brooklyn coastline.

By utilizing their wealth and influence to develop the built environment of their respective neighborhoods, capitalists and business owners helped shape DUMBO and Brooklyn Heights into separate entities: one, a center of industrial wealth, and the other, an elite residential suburb. After the Fulton Street Ferry opened, industries slowly started moving into the DUMBO area, which dissuaded wealthy homeowners from buying the land nearby. In 1836, one prominent resident wrote about Fulton Street as the great dividing line: “on its east live the masses… [and] on the westerly side reside the… silk stocking gentry” (Sullivan 1970). According to H. Allen Smith in his biography of business titan Robert Gair, the DUMBO of the mid-1800s was a “slum-ridden district… that possessed a handful of factories but was mostly an abode of wretched poverty. The dreary prospect of ramshackle tenements standing beside rows of shanties was not a pretty sight, nor were the sour smelling, dilapidated gin mills which stood on almost every corner” (Smith 1939). Smith paints a dire, somewhat hyperbolized picture of life in the area before the industrial boom of the 1890s. According to the 1855 Perris Atlas Map, most blocks were commercially and residentially mixed, such as the block encompassed by Front, York, Pearl, and Adams Streets containing a casting shop, machinist shop, and steam engine manufactory (Perris and Browne 1855). The largest industrial building on the map is Empire Stores on Water and Main Street, which would become a coffee storage facility and, later, a part of the New York Dock Company. Meanwhile, in Brooklyn Heights, the 1855 Atlas shows that mixed-use blocks containing factories were few and far between, and were all within one block of either the coastline or Fulton Street (Perris and Browne 1855).

Before the construction of the bridge, most of the factories in the DUMBO area were unique and only spanned a quarter or half of a block at most, with the exception of Empire Stores. By the 1880s, however, Perris Atlas maps depict marked shifts in the industrial composition of the area (Perris and Browne 1880). These changes are partially digitized on the maps in Appendix C, which track the expansion of Robert Gair Paper Goods, Arbuckle Brothers, and machine manufacturer E.W. Bliss and Company between 1880 and 1916 (Goldberger 2021).

Arguably, the most influential business in the area was Robert Gair Paper Goods. Gair, a Scottish immigrant and packaging manufacturer, unintentionally invented the paper box

when a metal ruler used to crease bags shifted positions and created a corrugated cut (“Gairville, Brooklyn” 2012). By 1879, he had established a business on Reade Street in Lower Manhattan and sought to expand into a more spacious location. His friend John Arbuckle, the owner of the massively influential Arbuckle Coffee Company, recommended DUMBO as a desirable destination due to its proximity to the coastline, the Brooklyn Bridge, and the homes of many of his workers. By 1887, Gair had purchased 37 acres of land in the DUMBO area and initiated construction of ten new buildings, six of which are shown in Appendix C, figure 3 on the 1916 Perris Atlas Map (Baics et al. 2021). Because of Rober Gair’s major influence on the built environment of the area, it became colloquially deemed, “Gairville” (The Bowery Boys 2022).

Another massively influential business that moved to the DUMBO area after the opening of the Bridge was the Arbuckle Coffee Company. Established in 1868 in Pittsburg by John and Charles Arbuckle, the business stood out from others of its kind due to John Arbuckle’s patented formula for a sugar-coated, egg-based glaze for coffee beans and his invention of a streamlined coffee packaging machine (Levine 2017). They moved to Brooklyn in the 1870s, transforming Empire Stores into a coffee and sugar warehouse. Over the next twenty years, Arbuckle Coffee Company would develop into an eleven-block complex with control over 85% of the nation’s coffee supply. Their growth is demonstrated by the white buildings (representing sugar) in Appendix C, figures 2 and 3; most of their buildings are located along the water close to the Brooklyn Bridge and the ferry (The Bowery Boys 2022). However, as their business expanded across Gairville, the brothers needed to develop an efficient system to transfer goods from the shoreline to multiple factories.

In 1904, the Arbuckle brothers invested in the construction of a private railroad soon to become the Jay Street Connecting Railroad (JSC). Although the JSC was initially intended only for Arbuckle Company use, John Arbuckle soon recognized the potential profit it would bring if it were to serve neighborhood businesses (“Jay Street Connecting Railroad”). The rail began at an open-air freight terminal under the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge adjacent to Dock Street, where crews of horse-drawn wagons could unload cargoes from freight cars directly into their vehicles. It ran North along Plymouth St., turned toward the East River at Adams Street, and finally traveled North into John Street, ending among a complex of piers, warehouses, and factories owned by the Arbuckles (“Jay Street Connecting Railroad”). The

JSC remained a central feature of DUMBO until 1959 and strengthened its identity as a prominent industrial landscape (“Jay Street Connecting Railroad”).

In contrast with Gair, Arbuckle, and other factory owners’ intentions to gain profit from industrial growth, landowners like Hezekiah Pierrepont in Brooklyn Heights sought to maximize wealth by investing in elite residential institutions. In the 1810s, Pierrepont owned land in what is now South Brooklyn Heights, while John and Jacob Hicks owned parts of North Brooklyn Heights (Furman 2015). Following the opening of the Fulton Ferry, the State of New York granted Brooklyn a charter to become a village. As stakeholders in the village’s development, Pierrepont and the Hicks brothers collaborated to design a unique street grid: however, they had different visions for the future of the Heights. Both parties agreed that smaller lots were key to residential development, but the Hicks brothers favored smaller lots than Pierrepont’s proposed 8-by-30-meter lots (Nevius 2015). In the end, the Hicks’ plan was adopted North of Clark Street while Pierrepont’s was adopted South of it. The Hicks brothers envisioned the development of a local middle-class suburban enclave and advertised North Brooklyn Heights with enticing street names including Pineapple, Orange, and Cranberry. Unsurprisingly, their curb appeal tactics failed and Pierrepont’s vision of a Manhattanite commuter suburb for merchants, bankers, and other elites won out (Nevius 2015). Pierrepont’s Brooklyn Heights developed with the construction of low-rise architecture, urban mansions, and pre-civil war Brownstone row houses suitable for wealthy families. The typical brownstone was three or four stories tall, with the main floor above the street level and reached by the stair. By 1841, more than two-thirds of the city’s wealthiest families lived within a single square mile on and around the bluff. With an increase in wealthy residents came an increase in public institutions: courts, churches, banks, hotels, and schools (Sullivan 1970). Appendix D shows the development of hotels, churches, and schools in the Heights and Gairville between 1880 and 1916. All three maps indicate that the Heights promoted residential growth significantly more than Gairville did. Schools and churches are only located on the fringes of Gairville, distant from the mainly industrial blocks bordered by Dock, Bridge, York, and Marshall Streets. Appendix D figures 1 and 2 show that the number of churches in Gairville declined between 1880 and 1906, likely due to high rates of construction during the industrial boom that hindered the growth of residential clusters (Baics et al. 2021). One school disappeared from the map between 1906 and 1916, demolished to make way for the Manhattan Bridge.

Brooklyn Heights, on the other hand, was known for its high concentration of pious institutions. In her biography of Henry Ward Beecher, author Debby Applegate describes an outsider’s perception of the area: “Sunday was the big day when the entire town promenaded to church. The churches were so central to social life that Manhattanites returning from a visit to Brooklyn were sure to hear the hackneyed joke, ‘Oh, did you go to a prayer meeting?’” (Applegate 2007, 201). According to the 1880 Perris Atlas map in Appendix D figure 1, at least nine churches were clustered around a 2 square-block radius near Monroe and Pierrepont streets (Baics et al. 2021). Some of the most famous churches in the Heights include St. Anne’s Church, Plymouth Church, and the Church of the Holy Trinity (Baics et al. 2021).

Schools were also common in the area, although most of the public schools were located on the fringes of the Heights because the majority of wealthy residents sent their children to private schools; this separation likely dissuaded lower-class families from settling in the heart of the Heights. Several notable private schools include Packer Collegiate Institute and Brooklyn Collegiate and Polytechnic Institute on Livingston Street, all-girls and all-boys respectively, and the Brooklyn Academy of Music, which became a prime social venue after beginning in the 1860s and hosted the opening ceremonies for the Brooklyn Bridge (Baics et al. 2021). In addition to schools and churches, hotels became a staple of the Brooklyn Heights built environment between 1880 and 1910. The first hotel in the area was a tavern opened in 1774 on Cranberry Street between Willow Street and Columbia Heights, which advertised its proximity to the ferry. By the early 1900s, there were over twelve luxury hotels in Brooklyn Heights, demonstrating the flourishing wealth of the area. The St. George Hotel, founded in 1885, remains a spectacular landmark. After its 1930 expansion, it contained 2,632 rooms and touted the world's largest saltwater swimming pool and ballroom. Pierrepont himself established several hotels on Willow Street, physical legacies of his major influence on the built environment and residential splendor of the Heights (Furman 2015).

As a result of their distinct built environments, DUMBO and Brooklyn Heights attracted residents and workers of differing social classes and ethnic backgrounds. Directly East of DUMBO, a large Irish population clustered around the Brooklyn Navy Yard in a neighborhood called Vinegar Hill. In the late 1700s, John Jackson bought 100 acres around the Eastern Waterfront where he established his own shipyard. He named the area Vinegar Hill in honor of the final battle of the 1798 Irish Revolution, with the hopes of attracting Irish immigrants

(Reiss 2001). Jackson was ultimately successful: by 1890, more than half the neighborhood was Irish. At its peak, Vinegar Hill accommodated more than 6,000 residents in 1,900 modest homes and small tenements (Reiss 2001). In 1880, the highest concentration of factory workers in North Brooklyn was located in and around Vinegar Hill. In contrast, the vast majority of Brooklyn Heights was devoid of factory workers; only the region closest to Fulton Street housed more than 20 factory workers per block. However, Vinegar Hill’s concentration of factory workers faded away almost entirely by 1910 (Baics et al. 2021). This is likely due to large-scale residential displacement during the construction of the Manhattan Bridge, which opened in 1909. While factory operatives and laborers made their homes on the fringes of DUMBO’s industrial area, a much wealthier tier of professionals settled in Brooklyn Heights. In 1880, the area below Pierrepont Street was home to an average of 52 to 64 lawyers, bankers, and managers per block (Appendix E figure 1). In 1910, a cluster of professionals also lived around Henry and Cranberry Streets. Individuals employed in high-paying industries contributed to the concentration and accumulation of wealth that would sustain the neighborhood’s elite legacy for decades to come (figure 2).

Between 1880 and 1910, the ratio of foreign-born to native-born individuals in DUMBO surpassed that of Brooklyn Heights (figures 3 and 4). In 1880, the majority of DUMBO’s blocks had a ratio of 66:33 % foreign vs. native-born residents, while the majority of Brooklyn Heights had a ratio of 33:66% foreign vs. native-born residents. Between 1880 and 1910, Brooklyn’s population skyrocketed from 599,000 to 1,634,000 residents. Although both neighborhoods show an increase in immigrants per block in 1910, DUMBO remained more ethnically diverse than Brooklyn Heights (“City of New York: Population and Population Density from 1790”). A combination of factors played into this foreign/native-born distribution. Brooklyn Heights’ wealthy real estate was relatively inaccessible to newly arrived immigrants with few resources to call their own, while tenements near the factories were much more financially feasible. In addition, DUMBO’s industries presented favorable access to a larger pool of job opportunities for unskilled laborers (Baics et al. 2021).

Two of the most prominent immigrant groups in the area between 1880 and 1910 were the Irish and the Italians (figures 5–8). In 1880, Irish-born individuals constituted between 21 and 40 percent of the block-level population in DUMBO and Vinegar Hill. Irish-born individuals were comparatively sparse in Brooklyn Heights (0–20% Irish residents per block), particularly

in areas of higher elevation. By 1910, the Irish population of Brooklyn Heights had increased significantly, but a large Irish cluster was still present to the East of DUMBO (figure 7, Baics et al. 2021).

The Italian population was relatively absent from Brooklyn Heights between 1880 and 1910 with the exception of clusters on Poplar and Willow Streets by the waterfront (figure 8). In DUMBO, however, the 1880 and 1910 maps show a significant increase in the ratio of Italian immigrants on blocks between Dock, Jay, Plymouth, and Front Streets (figures 7 and 8). Between 1900 and 1910, two million Italians immigrated to the United States, many through Ellis Island and into Brooklyn. Italian Americans generally gravitated toward unskilled labor positions including railroad, road, and bridge construction, making the outskirts of DUMBO an appealing location for settlement (“Digital History”).

Although they are geographical neighbors, Brooklyn Heights and DUMBO have had unique impacts on Brooklyn life, each contributing to the borough’s notoriety as both an appealing residential area and a center of industrial innovation. Brooklyn Heights’ transformation into a luxurious suburb attracted Manhattanite wealth throughout the 1800s and early 1900s and led to architectural developments that rivaled those across the East River. DUMBO’s growth into an industrial novelty contributed to the advancement of vast transportation networks such as the elevated railroad and subway, as well as further development of the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges. Though the ferry business lost its influence throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, it played an instrumental role in shaping the distinct social demographics of the two neighborhoods: wealthy landowners like Pierrepont utilized it to attract commuters to the Heights, while factory owners like Arbuckle and Gair utilized it to expand their businesses along the Brooklyn coastline. These wealthy titans’ contributions to the built environment shaped the settlement patterns of Brooklyn’s fast-growing immigrant population, which demographically distinguished the two neighborhoods. The nuanced story of Brooklyn Heights and DUMBO is still visible today: visitors can trace the remnants of the Jay Street Connecting railroad, peek through the windows of Empire Stores, and stroll along the tree-lined blocks of the Heights, marveling at Hotel St. George and the pre-Civil War era brownstones. In the center of it all is the Fulton Ferry Landing with a clear view of Manhattan, a powerful legacy of four hundred years.

Top: Figure 1, Middle: Figure 2, Bottom: Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figures 3 and 4

Applegate, Debby. The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher. New York: Doubleday Broadway Publishing Group, Dec 8, 2007.

Baics, Gergely, Wright Kennedy, Rebecca Kobrin, Laura Kurgan, Leah Meisterlin, Dan Miller, and Mae Ngai. Mapping Historical New York: A Digital Atlas. New York, NY: Columbia University. 2021. https://mappinghny.com

The Bowery Boys. “The History of DUMBO, the Brooklyn Neighborhood Built upon a Legacy of Coffee and Cardboard Boxes.” New York City History, February 28, 2022. https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2018/03/history-dumbo-brooklyn-neighborhood-builtcoffee-cardboard-boxes.html.

“Brooklyn Public Library Archive from 1809-1963.” Brooklyn Public Library archive from 1809-1963 - Brooklyn Public Library Archive. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://bklyn.newspapers.com/.

City of New York & Boroughs: Population & population density from 1790. Accessed May 12, 2022. http://demographia.com/dm-nyc.htm.

Everdell, William R., and Malcolm MacKay. Rowboats to Rapid Transit: A History of Brooklyn Heights. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Heights Association, 1973.

Furman, Robert, and Brian Merlis. Brooklyn Heights: The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of America’s First Suburb. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015. ISBN 9781626199545. Disponível em: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip&db=nlebk&AN=1190 128&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Accessed May 12, 2022.

“Gairville, Brooklyn.” New York History Walks, January 12, 2012. https://nyhistorywalks.wordpress.com/2012/01/09/gairville-brooklyn/.

Goldberger, Paul. Dumbo: The Making of a Neighborhood and the Rebirth of Brooklyn. New York, NY: Rizzoli, 2021.

Gray, Christopher. “Streetscapes/Robert Gair, Dumbo and Brooklyn; Neighborhood's Past Incised in Its Facades.” The New York Times. The New York Times, March 14, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/14/realestate/streetscapes-robert-gair-dumbobrooklyn-neighborhood-s-past-incised-its-facades.html.

“Historic Timeline.” Dumbo, February 23, 2021. https://dumbo.is/looking-back.

“The Jay Street Connecting Railroad.” www.nypress.com. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.nypress.com/news/the-jay-street-connecting-railroadJCNP1020030422304229995.

The Learning Network. “May 24, 1883 | Brooklyn Bridge Opens.” The New York Times. The New York Times, May 24, 2012. https://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/05/24/may-24-1883brooklyn-bridge-opens/.

Levine, Lucie. “Roasteries and Refineries: The History of Sugar and Coffee in NYC.” 6sqft, June 6, 2017. https://www.6sqft.com/roasteries-and-refineries-the-history-of-sugar-and-coffeein-nyc/.

Sullivan, Stephen Jude. “A Social History of the Brooklyn Irish, 1850-1900.” Academic Commons, January 1, 1970. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8639P4D.

“Mass Transit, Brooklyn Style.” Brooklyn Waterfront History, May 9, 2014. https://www.bkwaterfronthistory.org/story/mass-transit-brooklynstyle/#:~:text=In%201814%2C%20Robert%20Fulton%2C%20inventor,of%20rapid%20gr owth%20in%20Brooklyn.

McCullough, David G. The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012.

Nevius, James. “How Brooklyn Heights Became the City's First Historic District.” Curbed NY. Curbed NY, March 18, 2015. https://ny.curbed.com/2015/3/18/9982438/how-brooklynheights-became-the-citys-first-historic-district.

Perris & Browne. Insurance maps of the city of New York, 1850 and 1880. (New York: Perris & Browne) https://www.loc.gov/item/2010586541/.

Reiss, Marcia. Fulton Ferry Landing, Dumbo, Vinegar Hill Neighborhood History Guide. Brooklyn, NY, NY: Brooklyn Historical Society, 2001.

Smith, H. Allen. Robert Gair; a Study. New York: Dial Press, 1939.

Trachtenberg, Alan. Brooklyn Bridge: Fact and Symbol. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

US Census Manuscript Schedules 1850, 1880, 1900; US Bureau of the Census, Special Report: Vital Statistics for New York City and Brooklyn (Washington 1891).

“Welcome to DUMBO!” Dumbo, April 29, 2022. https://dumbo.is/.

How New York City’s Deliveristas Experience Traffic Violence and Utilize Cycling Infrastructure in the Upper West Side and Upper East Side

By: Clayton Thomas AndersonWhen the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered the doors of restaurants in New York City, demand for delivery services like Uber Eats, GrubHub, and Postmates went through the roof. Thousands of people started to cycle for these companies, but despite large strides in the construction of cycling infrastructure in the past decade, riding a bike is still relatively dangerous in New York City because of car crashes that can severely injure or kill cyclists. This study combines an interview-based approach to determining how bike infrastructure impacts the safety and wellbeing of deliveristas with a quantitative observation of streets in Upper Manhattan to assess who uses cycling infrastructure. Data collected from interviews revealed that 75 percent of a sample of 61 deliveristas had been hit by a car or a car door while working, indicating that cycling infrastructure often fails to protect the cyclist. With 97 percent of interviewees being immigrants and people of color, the racialized element of the problem of traffic violence cannot be understated, and in turn should be considered a matter of environmental racism. While the majority of interviewees indicated they feel safer riding in a bike lane compared to car lanes, a number of interviewees reported feeling the opposite and identified problems with the design of bike lanes. Bike counts on avenues in Upper Manhattan revealed that some avenues without bike lanes have similar numbers of cyclists compared to avenues with bike lanes, suggesting the need for more and better bike infrastructure.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, restaurants in New York were forced to shutter their doors, crippling the industry and rendering thousands unemployed. With dining rooms closed, food delivery services, while already around, gained greater popularity in the city, and a large though unknown number of New Yorkers ditched low-paying jobs in restaurants and delis and started making food deliveries on apps like Uber Eats, Postmates, and GrubHub. Known colloquially as deliveristas, a term that combines the English word “delivery” and the Spanish suffix “ista,” an estimated 65,000-80,000 traverse the city on bikes and e-bikes, quickly transporting meals through rain or shine and heat or cold (Figueroa 2021, 17).

In July 2021, deliveristas were honored at the Canyon of Heroes parade, which gave thanks to the city’s essential workers for putting their own safety at risk throughout the pandemic. Despite their importance to the city, deliveristas have endured numerous

inequities. Before the passage of protective laws in October 2021, restaurants refused to let deliveristas use their restrooms, delivery apps prevented workers from setting maximum travel distances, and delivery apps were not required to disclose their gratuity policies (Local Law 2298-2021, Local Law 2289-2021, and Local Law 1846-2021). On April 22, 2022, the NYC Department of Consumer and Worker Protection implemented regulations onto food delivery apps, requiring them to allow deliveristas to set distance limits, pay deliveristas at least once a week, provide a free insulated bag after six deliveries, and disclose the route, pay, and gratuities for an order prior to accepting it (Local Law 118-2021, Local Law 1162021, Local Law 115-2021, Local Law 114-2021, Local Law 113-2021). Recently, robberies against deliveristas have been common, with thieves eager to steal e-bikes that cost upward of $2,000 and are difficult to track by police (Dzieza 2021).

As cyclists, deliveristas also occupy a vulnerable position on New York City’s streets. While there have been large strides in developing New York City’s bike network in the last decade, riding a bike in the city is still dangerous, and even deadly (Sadik-Khan and Solomonow 2017). In 2020, 5,175 car-bike crashes resulting in injuries were reported, with 24 fatalities (NYC DOT 2020). Cycling injuries are likely to be significantly undercounted due to a lack of reporting, as indicated by interview results from the sample of 61 deliveristas. The term environmental racism refers to an environmental policy, practice, or directive that disadvantages individuals, groups, or communities based on race or ethnicity (Bullard 1999, 5). While usually the term is used to describe contaminated land, proximity to toxic industry, or the repeated occurrence of natural disasters, this researcher argues that the term can be extended to traffic safety issues in the built environment, and in this case, the lack of safe, quality bike lanes to protect cyclists from vehicles. This is a sharp departure from recent discourse that has accused bike lanes as being tools of gentrification that cater to wealthy, white riders, rather than safety infrastructure that benefits workers in some of the city’s most precarious occupations (Stein 2011, 34).

A history of working cyclists and cycling infrastructure in New York City

According to urban historian Evan Friss, cycling has risen and fallen in popularity and been subject to multiple bans and restrictions since bicycles first arrived in New York City in 1819 (Friss 2021). Initially an expensive hobby for New York’s white elites, bike prices began to drop by the 1890s when they hit the second hand market, opening the activity to a more diverse crowd, including immigrants and Black people. With a new contraption on the streets,

New Yorkers began to ask questions about where bikes should be allowed. City officials answered these questions by placing multiple restrictions on cyclists, regulating the time of day they could ride, banning them from parks, and requiring them to carry a lantern at night. Since cobblestone streets made it difficult to ride, cyclists began advocating for bike infrastructure, and in 1894, the City built an 18-foot-wide bike path on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn, without controversy (Friss 2021, 48). The City also laid narrow strips of asphalt to reduce costs of paving entire streets, but they were often blocked by carts and cars, similar to modern day issues with painted bike lanes.

In the early 20th century, Robert Moses, the city’s parks commissioner who had been rumored to never have ridden a bicycle, took the position that bikes were strictly for recreation and that streets were for cars only, so bike lanes were built only in and around parks (Friss 2021, 77). Little data about cycling was collected during Moses’s time, except for a record of crashes resulting from “careless bicycle riding” with no line item for car-bike crashes (Friss 2021, 88). This follows a similar sentiment seen in New York today, where cyclists are often blamed for being hit or causing crashes, even though it is the driver who hit them.

By the 1970s, no permanent significant bike infrastructure had been added to the city’s streets, but the demand for bike messenger services grew quickly. While commercial cyclists had been around before the 1970s and 80s in the 19th century, boys cycled to deliver telegrams, and during World War II, nurses made house calls on bikes bike messengers had especially intense jobs, being tasked with delivering documents quickly for offices across the city. They were primarily men of color only about three to four percent of bike messengers were women made up of struggling artists, immigrants, and people craving excitement and freedom from bosses (Friss 2021, 125). Bike messengers were paid about five dollars per delivery, and made up to $100 on a good day. They were not provided with insurance or paid leave, despite the high injury rates. Messengers did not fit into the predominantly white “cycling community,” which was primarily made up of recreational riders, eco-conscious “yippies,” and young urban professionals known as “yuppies” (Friss 2021, 129).

Even though other cyclists violated traffic rules, messengers were targeted by multiple pieces of legislation. In 1984, after a councilwoman was almost hit by a messenger, she proposed and implemented legislation requiring all messengers to carry identification cards and wear identification tags on their bikes so they could be ticketed (Friss 2021, 131). In

1986, after a 17-year-old messenger hit and killed a pedestrian, NYPD put together a report detailing how cycling was a danger to society, even though bicycle-vehicle crashes killed 24 people all cyclists the year before, while bicycle-pedestrian crashes killed two (Friss 2021, 133). New Yorkers were more likely to be killed by a falling air conditioner than a cyclist, but even so, this report resulted in the Midtown Bike Ban of 1987, which explicitly banned bike messengers from 5th Avenue, Madison Avenue, and Park Avenue in Midtown. Soon after the law was passed, bike advocates sued the city and won, tabling the ban (Friss 2021, 142).

In a shift of the city’s transportation policy during the Bloomberg administration, Janette Sadik-Khan transformed New York City’s streets into safer places for biking using only paint and good design (Friss 2021, 150). After visiting Denmark, Sadik-Khan imported the design of parking-protected bike lanes, where parked cars would act as a buffer between speeding traffic and cyclists. Due to low infrastructure costs, she worked quickly and added about 56 miles of new bike lanes each year, causing serious injuries on bikes to fall by 73 percent during Bloomberg’s three terms (Friss 2021, 178).

Though the internet eliminated the need for bike messengers, delivery cycling grew in the 2010s with the rise of delivery apps like Uber Eats and Postmates. Delivery cyclists started to use pedal-assist and throttle-based e-bikes, which add a boost of power while pedaling and allow a cyclist to use a throttle without pedaling, making it significantly easier to ride long distances and up hills. After public backlash to delivery cyclists, the deBlasio administration banned e-bikes in 2017, but quickly relaxed the ban in 2018 to allow pedal assist bikes though not throttle powered bikes again targeting commercial cyclists. After the start of the COVID pandemic in April 2020, the de Blasio administration announced that throttle-based bikes would be temporarily decriminalized in recognition that deliveristas were essential, frontline workers (Offenhartz et al. 2020). They were fully legalized in November of that year (NYC DOT 2020).

On the Upper West Side, Amsterdam Avenue and Columbus Avenue are both oneway streets with parking-protected bike lanes, Amsterdam going uptown and Columbus going downtown. Central Park West has car traffic that goes both uptown and downtown, with a buffered bike lane that goes uptown. West End Avenue lacks a formal bike lane, but has about a four-foot buffer between parked cars and car traffic. The Upper West Side lacks bike

lanes on Riverside Drive, West End Avenue, and Broadway. There are East-West painted bike lanes on 110th Street, 106th Street, 91st Street, 90th Street, 78th Street, and 77th Street.

On the Upper East Side, 1st Avenue and 2nd Avenue are both one-way streets with parking-protected bike lanes that go uptown and downtown respectively. The Upper East Side lacks bike lanes on the majority of its avenues, including 5th, Madison, Park, Lexington, 3rd, and York. There are East-West painted bike lanes on 110th Street, 106th Street, 91st Street, 90th Street, 78th Street, 77th Street, 71st Street, and 70th Street.

While the addition of parking-protected bike lanes to avenues in the Upper West Side and Upper East Side significantly improved safety, their designs and inexpensive installation techniques produce significant problems. New York’s parking protected bike lanes were famously cost-effective, since they only used paint and a reconfiguration of parking to create significant amounts of new infrastructure (Sadik-Khan and Solomonow 2017, 168). But because of this inexpensive construction technique, stretches of these cycling paths are littered with manholes and potholes, making riding bumpy and potentially hazardous. Despite being buffered by parked cars, automobiles and delivery trucks sometimes park in the cycling lane, blocking bike traffic and forcing cyclists to dart into the street. Painted bike lanes without a buffer of car parking are especially vulnerable to becoming parking spaces. Police officers are frequent culprits, and despite being a safety hazard, police say they reserve the right to park their vehicles in bike lanes (personal communication 2021). NYPD also rarely tickets or tows others who park in bike lanes, refusing to enforce traffic laws (Coburn et al, 2021).

The expansion of restaurants into the street due during the pandemic created a new conflict between pedestrians and cyclists. On Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues restaurant sheds overtook parking spaces, building to the borders of car lanes and bike lanes and often taking away the car door buffer on bike lanes. This constricts portions of the bike lanes, but also introduces new pedestrian-cyclist conflicts, since waiters and restaurant-goers frequently pass through the bike lane to get to the shed. Some restaurants have responded to this problem by putting cones in the bike lane, further constricting it, and signs that urge cyclists to slow down in both English and Spanish. Some pedestrians, not realizing that bike traffic travels through the lanes, step into the lane while waiting to cross the street or to take phone calls.

While a significant amount of bike infrastructure has been added to the Upper West Side and Upper East Side in the past decade, the bike lanes are imperfect and do not

completely protect cyclists from car traffic. The expansion of restaurant sheds onto streets have in some places narrowed bike lanes and created new potentials for cyclist-pedestrian conflicts.

While past studies have focused on various social and economic inequities that deliveristas face, little emphasis has been placed on how deliveristas utilize bike infrastructure and experience riding a bike through the city (Figueroa et al 2021; Lee and Saegert 2018). NYC DOT also lacks data about bike-car crashes for working cyclists, making the rate of crashes for deliveristas unknown. In recognition of the safety risks associated with riding a bike in the city, this study seeks to understand the unique interactions deliveristas have with New York City’s built environment and its cycling infrastructure.

NYC DOT conducts twelve-hour yearly bike counts on avenues in the Upper West Side and Upper East Side at 86th Street, but their counts do not differentiate between working cyclists (deliveristas) and other types of cyclists (NYC DOT 2021). Additionally, the DOT’s bike counts do not indicate if a cyclist was riding in a bike or car lane or if they were going the right or wrong way. Without this data, it is impossible to determine who bike lanes serve. For this reason, this study seeks to conduct bike counts that record if the cyclist is a deliverista or other cyclist, if they ride in the bike lane or in a car lane, and if the cyclist is going the right way or wrong way on the street.

To answer these research questions, this research will be divided into two parts: interviews with deliveristas and bike counts. See figure 2.

To answer the question of how bike infrastructure impacts the safety and wellbeing of deliveristas, a qualitative, interview-based approach was necessary to reflect the range and diversity of lived experiences. A quantitative, survey-based method would have limited the findings of this study by oversimplifying interviewees’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences. The interviews for this research were conducted on the street in the Manhattan neighborhoods of the Upper West Side and Upper East Side. This study focuses on these neighborhoods because as a student at Columbia University, I have noticed the large numbers of deliveristas working in the area. Conversations with deliveristas on the Upper West Side led me to expand the scope of this research to include the Upper East Side, since

multiple deliveristas told me there are lots of orders there, but the lack of bike infrastructure makes it more difficult to safely ride in the area. On certain days between June 14 and July 27 and the times of 1 p.m. to 8:30 p.m., I walked up and down avenues in the Upper West Side and Upper East Side and visually identified deliveristas who were either on taking a break on a side street or waiting in front of restaurants to pick up orders. I approached them and asked, “Do you speak English?” If they said only a little, hesitated, or no, I would ask in Spanish, “Hablas Español?” and then introduce myself in Spanish. If the deliverista spoke neither Spanish nor English, I would apologize and walk away.

Forty-three out of the 61 interviews were conducted in Spanish, and the rest were conducted in English. I am not a native Spanish speaker I started teaching myself when I was 12 years old but I am able to communicate effectively to where I can verbalize my questions and understand everything spoken to me. My Spanish is by no means perfect, and I frequently make grammatical errors, but this did not hinder my interviews with deliveristas. I never felt the sense that the deliveristas I spoke with were unsure if I understood them, and occasionally, my errors would lighten the mood and make the interviewees more comfortable. During one interview, when asking if the interviewee fell when he was hit by a car, I asked “te callaste?” instead of “te calliste?” which translates to “did you shut up?” He laughed, and then I realized my mistake.

A significant limitation of this research is that I was only able to interview English and Spanish speakers, leaving out large populations of deliveristas who come from Frenchspeaking countries in West Africa and a smaller population from Asian countries. While there are no statistics on what countries deliveristas come from, research by CUNY Queens Professor Do Lee focuses on the experiences of Chinese deliveristas, indicating there are large populations of Asian deliveristas working in the city, in addition to Central Americans and West Africans (Lee and Saegert 2018). I approached 88 deliveristas in total and interviewed 61 of them. Twelve deliveristas I approached whom I did not interview did not speak English or Spanish, and 15 were either busy working or did not want to participate.

I decided to take notes on my iPhone instead of asking if I could record the conversation, since I presumed that pulling out a recorder would make some people feel uncomfortable. Choosing to do this limited the number of direct quotes I could collect, but I was still able to document the conversations. I sought to establish an open environment

where deliveristas felt safe to share personal details of their lives with me while being aware of my class and racial presentation.

For privacy reasons, I assigned pseudonyms to the participants. Many deliveristas have undocumented immigration statuses, and while the risk of retaliation by immigration authorities from this research is low, assigning pseudonyms protects their identities.

Out of the 61 deliveristas interviewed, 51 disclosed their country of origin. Ninety-six percent of the interviewees were from countries other than the United States. Ten countries from three continents were represented, including Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Côte de Ivoire, El Salvador, Guatemala, Italy, Jamaica, Mexico, Senegal, and the United States. The largest group was Mexican, making up 23 of the participants, with 15 hailing from the state of Guerrero in Southwest Mexico, which has experienced significant violence and economic instability since the rise of the cartel Los Zetas in the 2000s (Woodrow Wilson International Center 2015). The next largest group of deliveristas interviewed was Guatemalan, making up 13 of the participants, followed by three Bangladeshis, and three Americans. Of the three Americans, all were from New York City. One was Black, one’s mother immigrated from Mexico, and the other did not disclose their ethnic background. As previously mentioned, this study is limited in its scope because interviews were only conducted in English and Spanish, leaving out large groups of French-speaking deliveristas from West Africa and others from Asian countries. None of the 61 of the deliveristas interviewed were white.

Of the 61 deliveristas interviewed, 40 disclosed their ages, which ranged from 17 years old to 59 years old. The median age of the participants was 26.5 years old. Fifty-nine of the 61 deliveristas interviewed were men, and two were women. While looking for deliveristas to interview and counting cyclists on streets, I saw three women making deliveries, two of whom I interviewed. Women are an underrepresented group of cyclists in the United States, making up about 30 percent of all riders, one of the worst gender disparities in the world, according to transportation researcher Ralph Buehler (Buehler 2021, 197). It is not clear why the gender gap among working cyclists is so pronounced, but it is likely that a combination of harassment, violent thefts, and traffic violence deter women from becoming deliveristas. One woman deliverista who I interviewed said she had been followed for blocks and had to call her boyfriend, also a deliverista, to diffuse the situation.

For many immigrants in New York, and especially undocumented immigrants, delivering food is far more attractive than other job options. Due to language barriers and lack of documentation, many immigrants are forced to take jobs in kitchens or delis, where they work long, stressful hours over hot grills, sometimes illegally being paid less than minimum wage. “They abuse you in restaurants,” Mario Hernandez, a 35-year-old from Mexico, said. “They want you to do the work of three or four people.” Moustapha Abdou, a deliverista from Senegal, remarked, “It’s not good working in restaurants. They don’t pay you anything.” Though research has shown that deliveristas make less than New York minimum wage at roughly $12.21 per hour, including tips, interviewees told me they make significantly more delivering than in restaurants (Figueroa et al, 2021, 7). In addition to better pay, interviewees told me they started working as deliveristas for a number of reasons, including the freedom from reporting to a boss, the ability to take breaks whenever they want, the ability to choose when to take days off, the ease of making deliveries compared to kitchen work, and the excitement of exploring the city. For many, making deliveries provided a new sense of freedom. Despite the risks of traffic violence and robberies that come with working as a deliverista, for many immigrants, this job is the best option. “The cars kill people, but we have to keep going because this is the only job we have,” Israel Rojas, a 39-year-old from Guatemala, said. “We can’t work other jobs.”

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic forced thousands of businesses to close their doors in New York, creating an exodus of immigrants from grueling jobs in restaurants. Many of them turned to delivery work, which provided and continues to provide stable work throughout the pandemic. Eleven interviewees in this study said they started making deliveries because they were laid off or their hours were reduced during the pandemic.

Traffic violence

Forty-five out of 61 deliveristas or 75 percent of the sample reported that they had been hit by a car or a car door while making deliveries. In comparison, a recent report by the Workers Justice Project found that 49 percent of their survey respondents had been hit by a car or a car door (Figueroa et al, 2021, 8). This study found that 23 out of 61 participants said they had been hit by a car. Of the 23 participants who had been hit, 19 indicated if they went to the hospital or not after the incident. Eleven of these 19 said they went to the hospital afterwards, due to substantial injuries from being hit. The rest either determined their injuries

were not serious enough to go to the hospital or were not injured during the crash (sometimes drivers bump the back tire of bikes, for instance).

Of the 23 participants who said they were hit by a car, 18 disclosed whether or not they reported being hit to the police. Only six out of the 18 reported being hit to the police.

Thirty out of 51 participants 59 percent said they had been doored while working, which occurs when a driver or passenger opens their door without looking for cyclists, causing the biker to run into the door. While these crashes are often less severe than being hit by a car, they can still result in fatalities. Recently in February 2022, someone riding a bike died after being hit by a car door on the Upper West Side (Kuntzman et al. 2022). Of these 30 participants, 22 indicated if they went to the hospital or not. Seven of these 22 went to the hospital afterwards. The rest determined their injuries were not serious enough to go to the hospital.

Of the 30 participants who said they were doored, 17 disclosed whether or not they reported being hit to the police. Three out of 17 participants who all went to the hospital as a result of their injuries reported the incidents to the police.

The frequency of traffic violence against deliveristas has lasting impacts both physical and mental on deliveristas and their families. Gonzalo Juarez, a 39-year-old from Mexico, said after a car hit him while he was working, he’s now afraid to ride. A taxi driver hit Alfredo Jonathan, a 26-year-old from Italy, while making a turn, putting him in the hospital for two weeks, forcing him to ask his family for money, since he couldn’t work. He still has lower back pain, which gets significantly worse during the winter. “My lower back is fucked for life,” he said.

Despite the fact that bikes cause crashes and kill pedestrians at far lower frequencies than vehicles, many New Yorkers perceive bikes to be the biggest threat to them on the street (Kuntzman et al 2021; Levine 2021; Hamilton 2019). Though only seven fatalities have been reported for bike-pedestrian collisions in New York City between 2010 and 2020 compared to the 1,499 pedestrian fatalities caused by cars (NYC DOT Pedestrian Fatalities 2021), city politicians quickly mobilized to pass laws targeting cyclists. Alfredo Jonathan noted this trend. “When a car hits a person, it’s different from when a bike hits a person.”

It is common for deliveristas to be blamed for being hit by cars and car doors and for assailants to not stop and render aid, let alone apologize. When a woman hit Gonzalo Juarez with her door as she exited her taxi, knocking him to the ground, she did not apologize or ask

if he was ok, but rather berated him for getting in her way. After someone doored Raphael Antonio, a 24-year-old from Mexico, they walked away without saying a word. The same happened to Inocente Rojas, who fell after being hit by a door. June, a woman deliverista who was hit by a car and badly injured, said that the driver kept going after the crash. Passersby ran after the driver and stopped him. She is pressing charges. This aggression and lack of empathy towards deliveristas have made many feel disrespected and as if the city does not care about them. “No one cares about our work,” said Jose Hernandez. “We don’t bother anyone,” said Israel Rojas. “We just want to work.”

According to a survey conducted by the Workers Justice Project, 54 percent of deliveristas have had a bike stolen (Figueroa et al. 2021, 8). This study’s sample of 29 deliveristas who disclosed whether or not they have been robbed found that 12 had been robbed or experienced an attempted robbery. Some deliveristas are robbed while they are on their bicycles and are held at gun or knifepoint, and others have their bikes stolen while they walk into restaurants to pick up orders. Thieves use bolt cutters to break bike locks, doing so discreetly and quickly.

Alberto Ruiz Gonzales, an undocumented immigrant from Guatemala, said that someone pulled a knife on him while he was working at 66th Street and 3rd Avenue on the Upper East Side. He defended himself and fought the assailant to get his bike back. Librado Pú, a 17-year-old from Guatemala, said he’s had his bike stolen twice, both times in front of Dig on Broadway between 112th and 113th Streets.

These thefts have large financial implications for deliveristas, since e-bikes popular among deliveristas cost somewhere between $1,000 and $2,000. Having to buy a new bike can be a large burden, especially since the average income for deliveristas is about $2,345 per month, according to the Workers Justice Project (Figueroa et al. 2021, 7).

Some deliveristas take precautions to avoid being victims of robberies. Jose Ortega, a 28-year-old from Mexico, said that he doesn’t deliver after 8pm. Many others agree that it’s more likely for them to be robbed when it gets dark. “It makes me scared to deliver at night,” Jose Mendez said, a 36-year-old from Mexico. Six deliveristas said that it is especially dangerous to deliver to public housing complexes, and three of them said that they no longer accept deliveries to them. “At 125th Street, they take bikes and try to fight you,” Hector Mendoza, a 42-year-old from Mexico, said, referring to NYCHA housing projects in the area.

“They’re always waiting for an immigrant to rob.” When delivering to a housing project, Mendoza said he’ll sometimes go in groups of deliveristas to appear less vulnerable. Despite these precautions, some deliveristas feel it is inevitable that they will be robbed or their bikes will be stolen. “I haven’t been robbed…yet,” Jose Galvez said, a 19year-old from Mexico who was raised in New York.

“The police don’t do anything”

Alberto Ruiz Gonzales, who has been hit by cars three times and been doored once, said he did not report the incidents because of his undocumented immigration status. He said he knows undocumented people who have reported crimes to the police and it resulted in immigration authorties coming after them. Gonzales, who was held at knifepoint during an attempted robbery, also did not report the incident to the police. “Reporting doesn’t do anything,” he said. “They don’t care about us.”

Other deliveristas who have been hit by cars, doored, or been robbed share similar sentiments about law enforcement’s effectiveness and interest. Jesus Castillo, a 20-year-old deliverista from Mexico who has been hit by cars twice, doored three times, and robbed once, has never reported to the police. “I didn’t report because the police don’t do anything,” he said. “We’re like trash to them.” Since most deliveristas do not have the financial capability to hire lawyers, it is usually very difficult or impossible for deliveristas to sue the driver who hit them or negotiate settlements, meaning reporting to the police is not a step towards justice, but rather a waste of time.

Bikes are extremely difficult for police to recover once stolen, so most deliveristas choose not to report the robberies. Mohammed Akter, a 22-year-old deliverista from Bangladesh, said his bike has been stolen twice. He reported to the police both times, but they never responded, so he assumes they did not find it. Instead of relying on the police, some utilize their network of deliveristas to help locate them, sending out messages on large Whatsapp group chats asking them to keep an eye out for their bike. Jesus Garza, a 35-yearold deliverista from Guatemala, said when his brother’s bike was stolen, he and his brother gathered a group of about 30 deliveristas to look for the bike. The bike was not recovered. Geobany Espinosa, a deliverista from Mexico, said when his bike was stolen on 106th Street in the Upper West Side, he did not call the police to report the theft, and instead he went with friends to look for it. He was unable to find it.

Barriers to reporting crashes and robberies

In addition to the perception that police officers do not do anything for deliveristas who are victims of crashes or robberies, NYPD poses other barriers for deliveristas who want to make police reports. Margarito Perez, a 43-year-old deliverista from Mexico who only speaks Spanish, said he called the police after he was robbed, but he wasn’t able to make a report because the person who answered did not speak Spanish. Anthony George, a 24-year-old deliverista from Harlem, New York, said he tried to make a police report after he was hit by a car, but the officers turned him away, telling him he had to report the crash at the precinct where he was hit. He never made the report because he didn’t think it was that important. “I could have gotten a settlement, but at least I have my life,” he said.

Currently, delivery apps do not offer ways to report a crash, either to the company or the police. Ibrahim Koffi, a 48-year-old from Cotê de Ivoire, was making a delivery when he was hit by a car, so he called the company to tell them why he would not be able to deliver the order. “They only say ‘I’m sorry,’” he said. When asked for the number of deliveristas who have been hit on the job, GrubHub, Postmates, Uber Eats, DoorDash, and Seamless did not respond.

Out of 40 deliveristas who were asked, 38 said their families worry about them while they are working because of traffic violence and robberies. Omar Cantú, a deliverista from Mexico, said after he told his family that someone tried to stab him to steal his bike, they told him “Money’s not everything. Life is more than money,” and asked him to quit. Jose Mendez, a 36-year-old from Mexico who’s been doored once and robbed twice, said his wife tells him to look for other work because she’s so worried about him. Jesus Garza, a 35-year-old from Guatemala, says his family always tells him, “May God protect you,” as he leaves for work each day.

The purpose of bike infrastructure is to provide dedicated space for cyclists to prevent deadly collisions with vehicles. But, not all bike lanes are successful in protecting cyclists. Thirty-six participants were asked if they feel safer riding in bike lanes or in car traffic. Twentythree said it was safer in bike lanes, five said safety is about the same in bike and car lanes, and eight said it was safer to ride in car lanes. Though 64 percent a clear majority of interviewees said they feel safer in a bike lane, 36 percent said they don’t feel any safer riding in the bike lane or they feel safer riding in car traffic.

Interview results revealed the presence of multiple design flaws for NYC’s bike lanes. Sharmin Khatun, a 27-year-old from Bangladesh, has experienced traffic violence in New York very intimately. His brother, also a deliversta, was hit and killed by a driver. Khatun said he feels safer riding in the bike lane than the street because the cars and buses aren’t able to drive in the lanes. He said he rides on 1st and 2nd Avenues because of the parkingprotected bike lanes. “I feel safe,” he said. Israel Rojas, a 39-year-old from Guatemala, agreed that it is safer to ride in the bike lane, but he pointed out that pedestrians, both knowingly and unknowingly, walk into the bike lane, creating the potential for crashes if he doesn’t ride carefully. Still, he said, the bike lane is far better than riding in the street, where he has to dodge cars and ride between them. Rojas said he thinks it would be a huge improvement to add a bike lane on 3rd Avenue, a crowded thoroughfare in the Upper East Side.

On the other hand, multiple deliveristas explained why they thought it was safer to ride in the street, rather than the bike lane. Hector Mendoza, a 42-year-old from Mexico, said he doesn’t believe bike lanes work because people park in them and leave their doors open. Pablo Juarez, a 27-year-old from Mexico, said it’s safer to ride in the street than the bike lane because of pedestrians who wander into it, including children and old people. He would rather compete with cars than possibly hit a pedestrian or have to dodge parked cars, which, he pointed out, are often police cars.

Discussion

This 61 person sample, where 75 percent of all interviewees had either been hit by a car or a car door while working, indicates the presence of a public health issue of traffic violence that most directly impacts deliveristas, whose jobs require them to be riding for long periods. Moreover, the demographic makeup of deliveristas the vast majority of whom are immigrants, people of color, and low-income indicate the presence of a racialized inequity stemming from New York City’s built environment. For this reason, this researcher classifies the problem of traffic violence directed towards deliveristas as environmental racism. Since neither NYPD nor NYC DOT collect data on the number of crashes involving deliveristas or working cyclists, the impact of traffic violence on deliveristas is unknown to the city. Additionally, deliveristas in this sample reported incidents of traffic violence and robberies at very low rates, indicating that these events are likely significantly undercounted by NYPD.

Deliveristas are hesitant to report crashes or robberies to the police for reasons including concerns that police could arrest them because of their immigration status and the view that reporting to the police does nothing. While it is possible that police outreach to deliveristas could bridge the gap in trust between NYPD and this workforce, it is my view that no amount of public outreach will convince immigrant deliveristas that they will not be at risk of facing incarceration or deportation. Additionally, reporting a crash to the police can be time consuming and confusing.

The majority of deliveristas in this sample agreed that riding in a bike lane was safer than riding in car lanes, though the ability for drivers to park in bike lanes reduces their safety. Improving bike lanes by adding permanent infrastructure like bollards or concrete curbs, which have been deployed in cities across the world, could solve this issue. Pedestrian-bike conflicts are also a significant safety problem, though the solution to preventing these interactions is less clear as restaurant sheds are likely to remain on New York’s streets in the endemic COVID era.

Conducting bike counts that differentiate working cyclists from others is necessary to quantify the extent to which (a lack of) bike infrastructure impacts deliveristas. Twenty-eight times during June and July of 2021 and the hours of 5 p.m. to 8 p.m., I sat on street corners at 85th Street and the following major avenues in the Upper West Side and Upper East Side: Upper West Side

Riverside Drive, West End Avenue, Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue, Columbus Avenue, Central Park West Upper East Side 5th Avenue, Madison Avenue, Park Avenue, Lexington Avenue, 3rd Avenue, 2nd Avenue 1st Avenue

I chose to sit at 85th Street, the numeric center of the Upper West Side and Upper East Side (using the downtown boundary of 60th Street and the uptown boundary of 110th Street), for all of these avenues in an attempt to control variation in these counts.

The intersections of 85th Street and avenues on the Upper West Side and Upper East Side have different land uses. On the Upper West Side, Riverside Drive, West End Avenue, and Central Park West only have residential uses, whereas Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue,

and Columbus Avenue are mixed-use, with restaurants and shops on the ground floor and apartments above. On the Upper East Side, 5th Avenue and Park Avenue are only residential use, whereas Madison Avenue, Lexington Avenue, 3rd Avenue, 2nd Avenue, and 1st Avenue are mixed-use.

New York City law requires working cyclists to wear a helmet while on the job (NYC DOT, 2021). If cited, a deliverista must go to court and potentially pay a fine ranging from $15 to $500, depending on the charge. This law polices deliveristas but exempts people who ride bikes for commuting, leisure, or any other activity, continuing a historic trend of targeting biking laws at people who ride bikes for work. Enforcement of these laws likely falls starkly along racial and socioeconomic lines, given that the vast majority of deliveristas and 100 percent of this sample size are Black, Indigenous, and people of color. Ninety-six percent of deliveristas in this study were immigrants.

This summer was especially hot with high temperatures hovering around 90ºF, so some deliveristas chose not to wear helmets, which get uncomfortably warm. To avoid drawing attention from police, some deliveristas ditched their large, boxy food carriers, and opted to carry food by the bag on their handlebars or basket, as well as abandon reflective vests for inconspicuous pedestrian clothing. For this reason, it could be entirely possible that I undercounted the number of deliveristas on the street, though it is impossible for me to tell by what margin.

The following graph records the number of people riding bicycles on the road, noting if the person was clearly a deliverista or another type of cyclist. Due to the large number of bicycles rolling quickly through the street, it was impossible for me to record other data, such as the perceived gender or race of the cyclist, or if they were riding a personal bicycle or a Citibike, and an e-bike or a regular bike. See figure 3. Raw numbers of deliveristas and other cyclists on avenues in Upper Manhattan.

The following graph shows raw data from bike counts, including the first count, indicated as #1, and the second count, #2. I was only able to take two bike counts for each avenue due to time constraints, and while this is not statistically significant data, the counts reveal how avenues with bike lanes generally attract more cyclists, though some avenues without bike lanes Third and Broadway have similar levels of ridership to avenues with bike lanes.

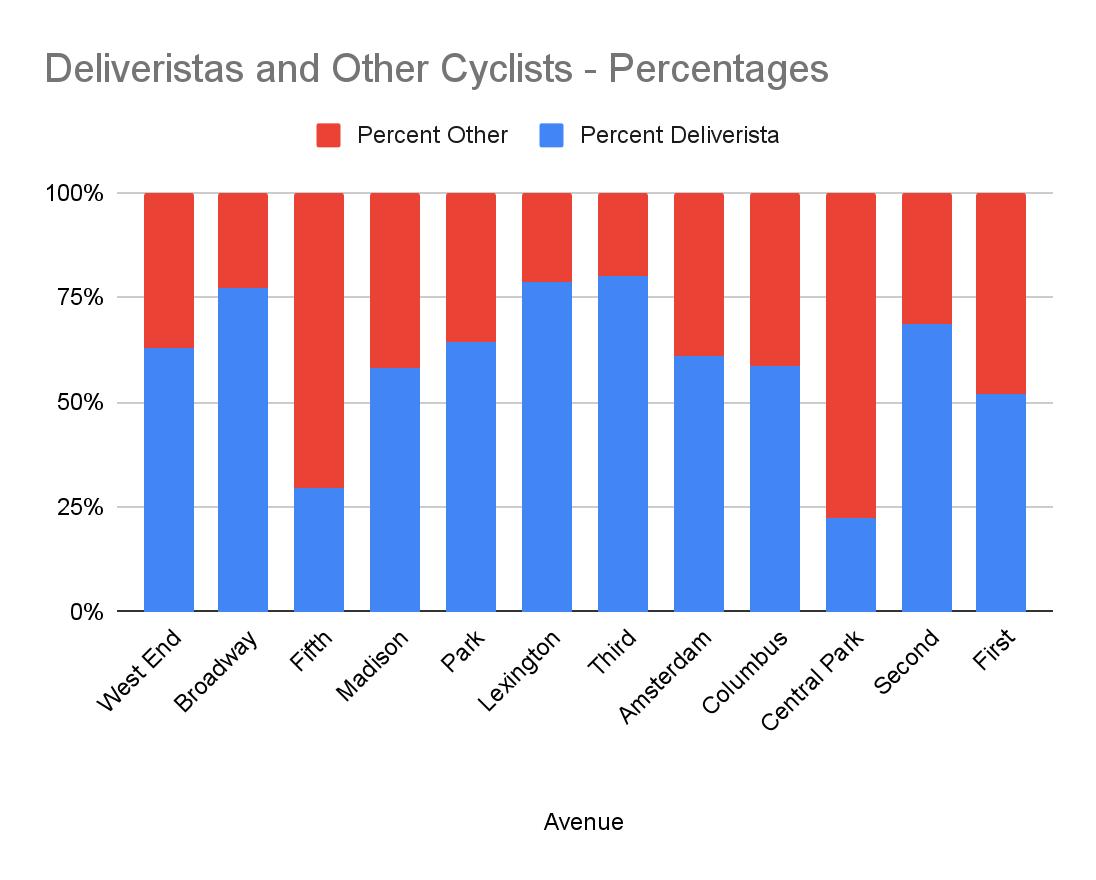

While the total number of cyclists observed neared 50 percent deliveristas and 50 percent other cyclists, different types of cyclists use select avenues at different rates. While thoroughfares such as Fifth Avenue and Central Park West mainly serve recreational cyclists due to their position surrounding Central Park, over 75 percent of cyclists on Broadway, Lexington Avenue, and Third Avenue were deliveristas. See figure 4.

Wrong-way cyclists

Wrong-way cycling can create unsafe cycling conditions for both the wrong-way cyclist and others around them. But, wrong-way cycling should not be viewed as a deliberate defiance of the law, rather an indication that one-way cycling infrastructure does not meet the needs of cyclists. There are many reasons why someone may choose to bike in the wrong direction. For instance, to reach a destination using one-way cycle paths, it may force the cyclist to circle the entire block, an annoying detour that could be avoided by briefly biking in the wrong direction. When separating deliveristas from other cyclists, there is not a significant difference between the rate each group was observed biking in the wrong direction. See figure 5. Percent of cyclists going in the wrong direction organized by avenue.

Discussion: bike counts

Avenues without bike lanes

Compared to avenues with bike lanes, avenues without bike lanes serve an average of twelve percent more deliveristas. Out of the six avenues with the highest percentages of deliveristas, five of them lack bike lanes. The following reasons could explain why avenues without bike lanes generally serve a higher percentage of deliveristas compared to other cyclists:

1. Deliveristas do not have the choice to take a potentially safer route with a bike lane because they are trying to get to specific restaurants or apartments.

2. Deliveristas are using the most direct route to their destination to maximize their speed of delivery. The most direct route may not have a bike lane.

3. Other cyclists including recreational cyclists and commuters may be intimidated by fast moving car traffic, leading them to take routes with bike lanes.

Wrong-way cycling