Barnard Columbia Urban Review

Spring 2024 Issue

Barnard Columbia Urban Review

Spring 2024 Issue

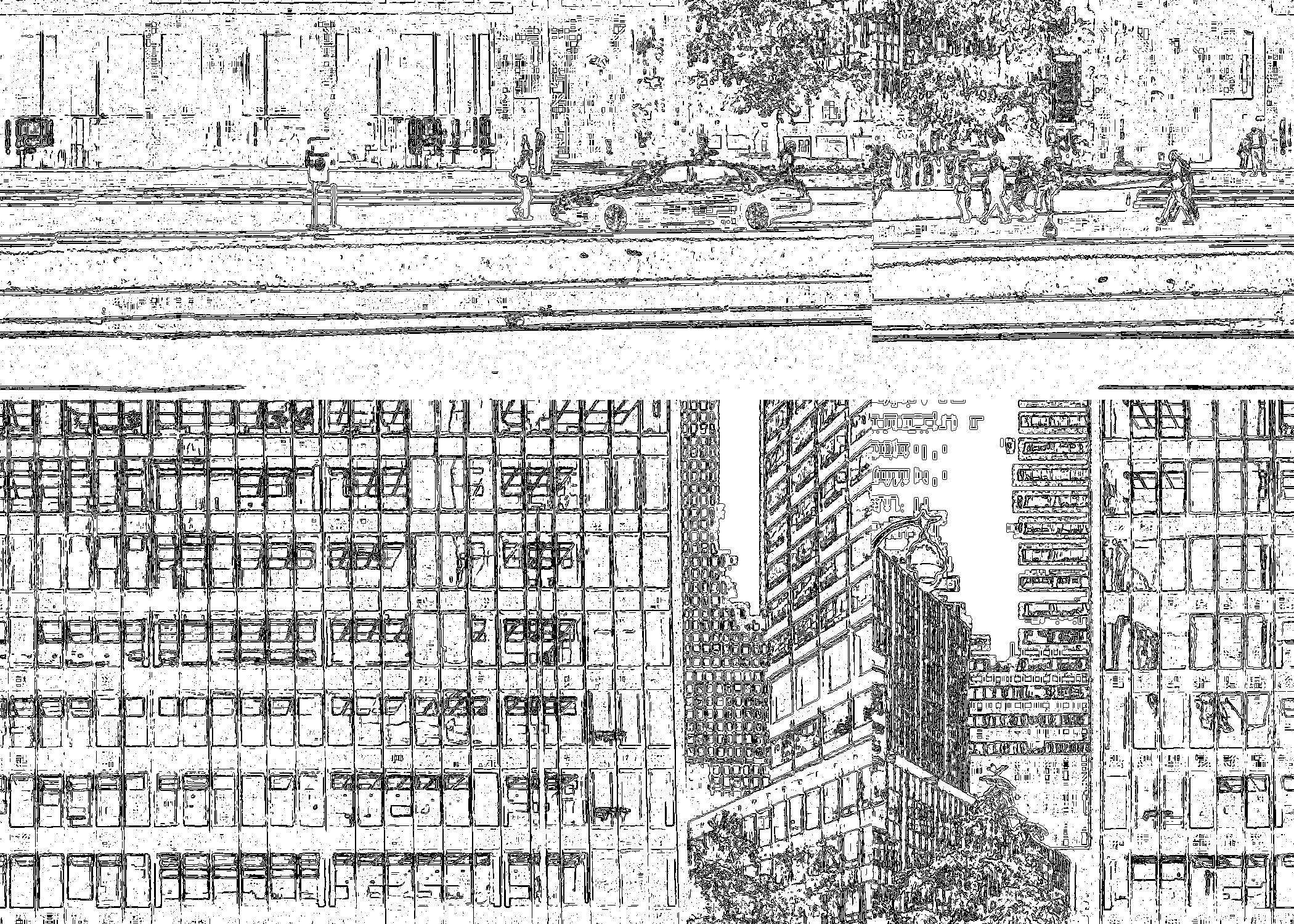

FRONT COVER

Iman Taha

UNTITLED (PEDESTRIAN); UNTITLED (CURTAIN WALL); UNTITLED (FACADE)

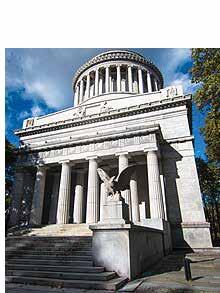

MONUMENTS OF ADHERENCE & RESISTANCE

Bayley McDaniel

UNTITLED

Zoe Pyne

BACK COVER

Zoe Pyne 1

EXECUTIVE BOARD

EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

NYAH AHMAD, BC ’24

MAYA FELSTEHAUSEN, BC ’25

LAYOUT EDITOR

AMANDA CASSEL, BC ‘25

PUBLICITY DIRECTOR

JACQUELINE ARTIAGA, BC ’25

EVENTS MANAGER

GISELLE (GIGI) SILLA, BC ’24

TREASURER

JENNIFER GUIZAR BELLO, BC ’24

SENIOR EDITORS

ELEANOR AILUN DING, CC ’26

MARGARET BARNSLEY, BC ’24

ISHAAN BARRETT, CC ’26

SOPHIA CORDOBA, CC ’26

LILLY GASTERLAND-GUSTAFSSON, BC ’25

ANANYA PAL, BC ‘25

PEER REVIEWERS

JACQUELINE ARTIAGA, BC ‘25

MARTHA CASTRO, BC ‘27

LOWELL CERBONE, CC ’26

SUSANA CRANE, BC ’26

FRANKIE EISENBERG, BC ’26

HELEN GOODMAN, BC ‘27

ALIA KHANNA, BC ’27

ASHLEY MEDEL, CC ’25

AVA LYON-SERENO, BC ’26

VICTORIA TSE, BC ‘24

AUTHORS

YUMTSOKYI BHUM, BC ‘24

AMY XIAOQIAN CHEN, CC ‘26

FARUK ECIRLI, UPENN ‘27

JENNIFER GUIZAR BELLO, BC ‘24

MADELEINE MARTIN, BC ‘27

JARED MURTI, USF ‘24

THEA PAN, BC ‘26

DANIELLA RIVERA-AGUDELO, BC ‘25

AIMAR ROSARIO ÁVILA, BC ‘25

ART CONTRIBUTORS

BEN ERDMANN, CC ‘25

BAYLEY MCDANIEL, GS ‘25

ZOE PYNE, BC ‘26

COVER ARTIST

IMAN TAHA, BC ‘25

BACK COVER ARTIST

ZOE PYNE, BC ‘26

STAFF WRITERS

ISHAAN BARRETT, CC ‘26

FRANKIE EISENBERG, BC ’26

VERA (V.V.) JANNEY, BC ‘26

WEB MANAGER

MADELEINE MARTIN BC ‘27

PUBLICITY STAFF

TENZING (CHO) CHOSANG, BC ‘26

VERA (V.V.) JANNEY, BC ‘26

EMILY LIN, BC ‘26

CLAIRE MCDONALD, BC ‘26

EVENTS STAFF

LAILA ABED, CC ‘27

AVA LYON-SERENO, BC ’26 66

Ben Erdmann 68

It is with pleasure and pride that I write—again—to celebrate the release of a new volume of the BarnardColumbia Urban Review. As much as “pleasure” and “pride” are key to that sentence, I want to emphasize the “again” above all. Student publications are not always long-lived, because they require continuity in a context of constant change. It is not easy to find the next group who will be eager to run the show when the current group graduates and it is not easy to gracefully hand it over. BCUR has accomplished this and more. While also an excellent outlet for student research, BCUR has transcended its origins as a publication and become a collective, a community of shared interest in the urban—of precisely the kind our program aspires to. Leave it to students to figure out how to make this work!

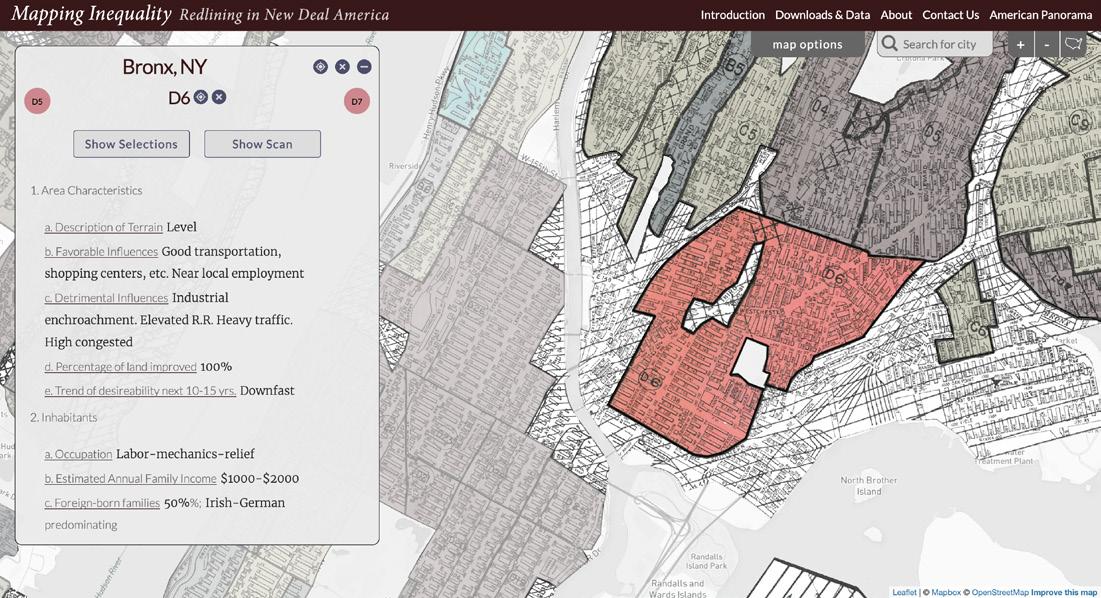

What will likely strike you first about the articles in the seventh issue of BCUR is their geographic diversity. The student researchers included here are investigating urban dynamics in Colombia, Istanbul, Puerto Rico, San Francisco, Manhattan, and the Bronx, with attention to diasporic populations in some of the places closer to our campus. This points to their attention to the diversity of urban phenomena and experiences and demonstrates the importance of doing what Professor Smith might call thinking “elsewhere,” even when thinking about places nearby. You might equally notice a concern for social justice—the words “vulnerability,” “injustice,” “racialization” and “racial capitalism,” “homelessness,” and “power relations” stand out in even a quick look at the titles. Finally, you might also detect the enduring importance of New York City itself to the Urban Studies Program in the city of New York.

It is hard, as I write this, not to slip into unattractive self-congratulation. You all, after all, are conspicuously embodying the goals that we share for this program—already! But I cannot persuade myself that we (smearing my colleagues by association) have done much more than facilitate the interests and energy that you brought with you into our classes and into the major. Let me say again then how pleased and proud I am to celebrate the efforts of the authors, editors, and all who contribute to the process of creating BCUR and to the community that surrounds it.

Sincerely,

Aaron Passell Director of the Barnard–Columbia Urban Studies Program

Aaron Passell Director of the Barnard–Columbia Urban Studies Program

We are delighted—and especially relieved—to present as Co-Editors-in-Chief the seventh issue of The Barnard-Columbia Urban Review. It’s hard to believe the time has come to present this issue as we wrap up the academic year. This spring, we received a record number of written submissions, publishing nine papers in this journal, along with student-created visuals dispersed throughout the journal. We remain foregrounded in our presence as one of the few publications that are a part of Columbia University Apartheid Divest and hope to only expand our organizing efforts within and beyond the institution in the coming future. Our weekly newsletter and Instagram page have remained active throughout the semester and we published four new staff articles this semester, all of which can be found and read on our updated website, www.bcurbanreview.com.

In addition to our biweekly meetings, we organized events such as an excursion to the Queens Museum; a film screening of The Last Black Man in San Francisco ; a Zine Night in the Barnard Zine Library; and an Urban Studies Senior Thesis panel. This would not have been possible without the organization and support of Jacqueline, our Publicity Director; Amanda, our Layout Editor; Gigi, our Events Manager; and Jennifer, our Treasurer. BCUR is far more than a student-run publication, and we are constantly reminded of that through all the hard work invested to foreground ourselves as the only social and professional network of students with like-minded passions surrounding urban studies on campus.

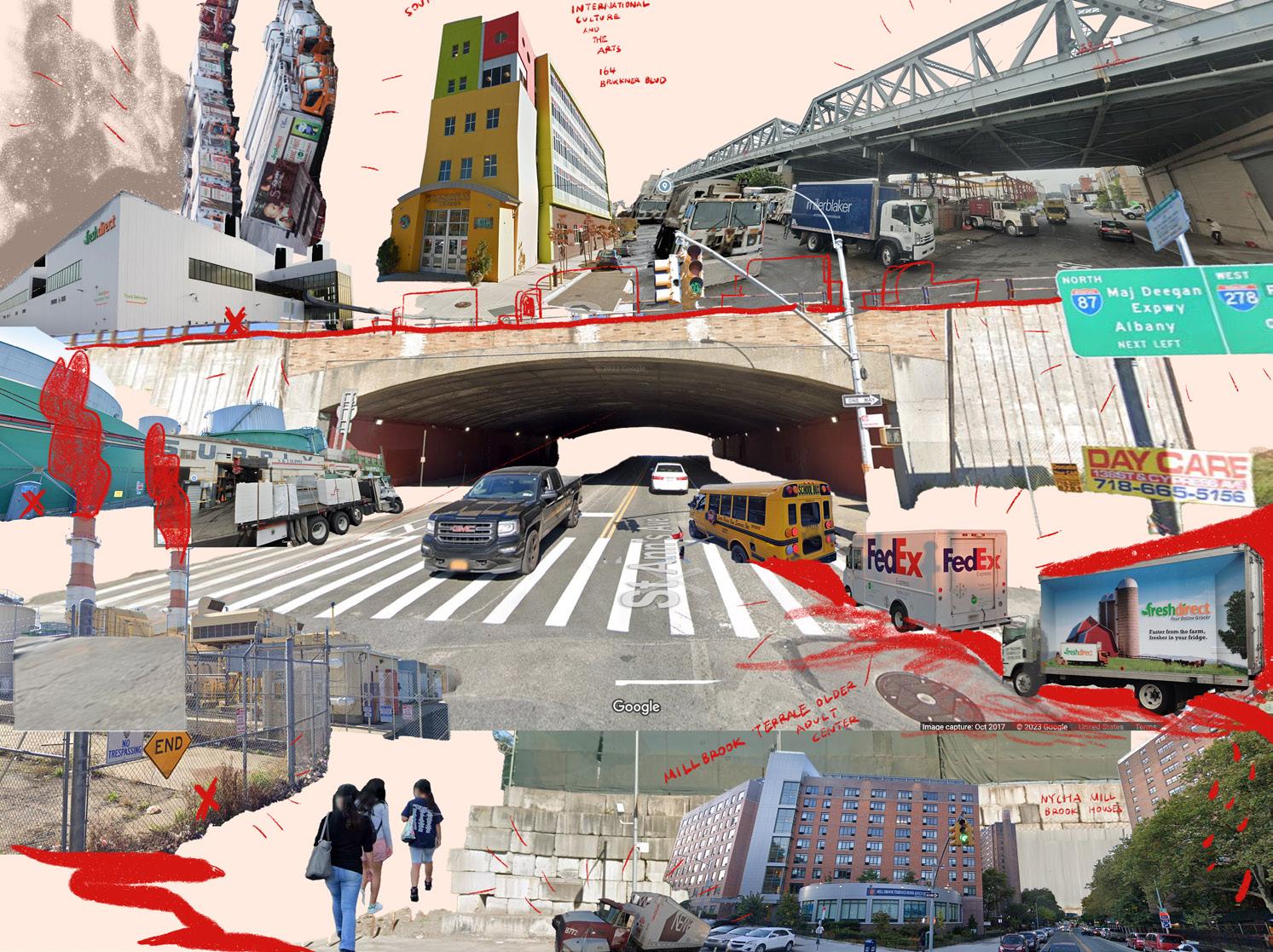

The front cover of this semester’s edition includes an intricate multimedia collage by Iman Taha that reflects various urban structures and elements. The written work in this publication highlights students’ critical, multidisciplinary approaches to global and translocal urban research. From addressing urban environmental justice in neighboring boroughs; investigating urban space in international cities; to intersecting frameworks of critical theory in urban environments, our contributors explore the crucial urban social, political, and material phenomena of the present. We also welcomed two undergraduate submissions from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of San Francisco, expanding our journal to student contributors across the country! Interspersed between our written pieces are visual works, all of which are united by the photographers’ attention to the built environment.

We want to express our utmost gratitude for the work and dedication of countless individuals in bringing this journal together. The work we do truly is a collective effort. A big thank you to the BCUR executive board and general members; written and visual submission contributors; our peer reviewers; our senior editors; the faculty and staff of the Urban Studies department; the administrative staff of SEE; every past and future BCUR member; and countless others who have supported our endeavors with BCUR every step of the way. We are so proud of the community we have been privileged to foster through our work—both within the Urban Studies cohort and beyond.

As the Co-Editors-in-Chief for BCUR this academic year, we are eternally grateful for the opportunity to embrace this role and expand the organization. We have accomplished so much this year as an organization and we know that BCUR’s only trajectory from here is a positive one. As we pass off our positions to the new Co-Editors-in-Chief, our only wish is for BCUR’s continual growth and impact across the university—and across the world—particularly for those passionate about urban studies. We sincerely hope you enjoy this issue as much as we do. Creating it was a cosmic labor of love from start to end. And as always, Free Palestine.

Sincerely,

Nyah Ahmad Maya Felstehausen

Nyah Ahmad Maya Felstehausen

Co-Editor-in-Chief | Barnard College ’24

Co-Editor-in-Chief | Barnard College ’25

INTRODUCTION

This study is inspired by the work of the Copenhagen-based company, arki_lab, and the Boston-based non-profit, Culture House, both of which specialize in coordinating planning-stage community involvement through intentionally short-term projects. I had the opportunity to meet the founders of both organizations while studying in Copenhagen in Fall 2023, and after learning about their common model for local engagement, I was drawn to the concept of how structures with planned impermanent trajectories might not only serve to accommodate the ever-evolving, pressing needs of residents, but also challenge the dominant definition of a successful urban space as one with steadily increasing land value. In search of connections between temporality and community engagement, I turn to two frequently cited pieces by authors of different eras, professions, and regions: Philipp Oswalt’s (2013) Urban Catalyst and Henri Lefebvre’s (2004) Rhythmanalysis. Reading Lefebvre’s study and categorization of urban daily life in tandem with Oswalt’s (2013) survey of terrains vagues in post-reunification Berlin illuminated for me the incongruence of addressing cyclical human needs with physical structures that are governed by linear notions of property value. Intrigued, and with the good fortune of being only a train ride away, I visited the Berlin neighborhoods surrounding some of the temporary urban spaces studied by Oswalt (2013). The differences between Oswalt’s (2013) description and my 2023 observations raised for me the question: why, and by what means, are some sites created by interim users subsequently regarded as useful steppingstones for more permanent development—and permitted entry into the city’s linear structural history—while others remain within the same unfixed temporal trajectory as before? I explored these questions by visiting two sites that were born in similar, yet distinct, circumstances; both exist today under dramatically divergent leadership structures: Arena Berlin and Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal. More specifically, I visited Arena Berlin in the neighborhood of Kreuzberg, where the now commercialized concert-hall once operated informally, and two sites that Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal has occupied, including both its current location and its previous location along the Spree River. At Arena Berlin I attended a “Qweer Market” held in the space during its most bustling time of day: night. Not only did a young crowd queue for Qweer Market, but also for the venue’s adjacent nightclub and for other, unaffiliated surrounding venues. For reasons that will be explained below, the grounds of Radical Qweer Wagenplatz Kanal were less accessible. So while I document demographic and social patterns of Arena Berlin based on in-person observations, for Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal I mainly rely on their extensive website postings. During my visits I recorded observations of the surrounding neighborhoods in all the aforementioned locations, especially to document signs of new, formal development. Paradoxically, some temporary urban spaces with trendy

manifestations of counterculture are co-opted by the very growth-oriented models of neighborhood-building which they symbolically, even if inadvertently, subvert. I will be utilizing research from urban scholars on how applications of tactical urbanism have diverged from its roots to understand discourse on what and who makes a city attractive. To analyze recent private and governmental involvement in temporary urban spaces, I will reference past scholarship’s already-established theoretical and economic distinctions between what informal economy and informal space risk upon being institutionally regulated. In the following literature review, these concepts will be explored in terms of their interconnectedness, and will then be applied to the two case studies of temporary urban spaces in Berlin. The discussion of the case studies will address the question: how might a space’s vulnerability to private and government appropriation eventually manifest in its evolving physical and ideological forms?

Born out of necessity, temporary urban space should not be considered an active resistance to so much as a subversion of a city’s obsession with land value. Prominent urban theorist Harvey Molotch (1976) positions the influence of urban landowners as a central force in shaping city policies, a structure upheld by both the state and private enterprises that seek to increase the values of their properties by attracting demographics that they deem desirable (i.e. “the growth machine”). Recently, there has been a trend among these two sets of players to mobilize “creative” urban aesthetics as a means of attracting a wealthier socioeconomic class, as discussed by Richard Florida (2012) in his book, The Rise of the Creative Class. For instance, he mentions a monthly arts festival that the Las Vegas-based tech firm, Zappos, funds as an “urban-renewal” effort (Florida 2012). While some urban scholars contend that such projects only serve to make city planning more inclusive, others disagree, claiming that they instead end up displacing the very residents from whom their ground-up designs were inspired. This literature review will further discuss the private-sector and government appropriation of resident-based tactics, as well as the criticism that it has generated from urban scholars, architects, and urban economists alike. Building on this analysis, this paper will examine two once-temporary urban spaces in Berlin as imperfect, yet relevant case studies for applying and drawing out existing literature and theory regarding temporality and commodification of land in the urban, built environment.

In his piece, Rhythmanalysis, Lefebvre proposes rhythm as a method of analysis for gauging the flow of one’s own bodily experience simultaneously to that of one’s external happenings (Lefebvre 2004). Distinct paces—quick, legato, rushed, etc.—of one’s internal and external experience are understood precisely in terms of their interaction. Embodied repetition is how these paces, which are integral to rhythm, manifest. Lefebvre refers to absolute repetition as “only a fiction of logical and mathematical thought,” because, if “A= A (the sign reading ‘identical’ and not ‘equal’),” then “the second A differs from the first by the fact that it is the second…Not only does repetition

not exclude differences, it also gives birth to them” (Lefebvre 2004). He argues that rhythm complicates otherwise purely mathematical or scientific analyses because it embodies repetition, therefore detecting differences both within and between patterns of day-to-day life (Lefebvre 2004). For example, if a city-dweller who walks down a particular street every morning has an early appointment one day, her rush might make her feel as though the crosswalk lights are especially slow or passersby especially relaxed. In this way, situational perception is more accurately described with a relational lexicon because of how the understanding of a new situation or environment so often stems from comparing it to a past one.

The terms “cyclical” and “linear” are widely used by theorists to categorize conceptions of time (Lefebvre 2004; Madanipour 2017). Lefebvre’s analysis of rhythm positions the “cyclical” as more relational and the “linear” as more dualistic. Broadly, cyclical manifestations of time are linked to biological, natural systems, like the circadian rhythm, while linear descriptions of time are related to man-made, progress-oriented systems (Madanipour 2017). In the context of urban theory, however, scholars have also applied cyclical time to social patterns. In his 2017 study, Cities in Time, Ali Madanipour writes, “through cultural practices, a common sense, cyclical concept in biological life is extended to human societies as a whole, observed in the succession of kings, recurrence of floods and earthquakes, [and] emergence and decline of cities” (Madanipour 2017). These events are rhythmically cyclical because their actors collectively encounter and adapt to biologically-imposed changes, whether these be the death of a ruler or destruction due to natural disaster. Madanipour even includes a city-level scale of impermanence, being the “emergence and decline of cities” (Madanipour 2017). In doing so, he argues that human, social processes are not exempt from the culminating impacts of earthly, natural processes. Abandoning reverence to a no-longer situationally suitable order, “the cyclical is social organization manifesting itself” (Lefebvre 2004). A linear concept of time, in contrast, is rooted in forces that control day-today routines for the sake of consolidating a communal sense––but top-down definition––of progress (Lefebvre 2004). Thus, it is more susceptible to being dictated institutionally. An example of linear time integral to this paper is the commodification of land and how it sets urban standards of progress to consistently appreciating land values. Madanipour argues that linear conceptualizations are “decontextualized from people and places… understood by mathematical and technological methods” (Madanipour 2017). Because the linear lens is “decontextualized,” ––ideologically imposed onto rather than biologically stemming from humans and their environments––a subject who employs it to understand the history and future of a physical space is likely less cognizant of that space’s interconnecting rhythms (Lefebvre 2004).

Tactical urbanism is an adaptive measure that exposes and addresses the shortcomings of “decontextualized” linear urban strategies. Oli Mould defines “Tactical Urbanism” as “small-scale activities undertaken by local citizens that redesign their urban area to be more ‘liveable’” (Mould 2014). One apt example are the “parklets” built by the non-profit organization, Street Lab, during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. In current literature regarding tactical urbanism, “tactics” are framed as resident responses to an urban landscape’s current rhythm, whereas “strategies” seek to command a future one into being. In “What City Planners Can Learn from Interim Planners,” theorist of temporary urban spaces, Peter Arlt, quotes military general

Carl Von Clausewitz (1780–1831) as having defined tactics as “the art of landing blows in the other’s realm” (Arlt 2004). Tactics are implemented on any property other than the actor’s non-existent own, and are therefore unconfined by spatial or temporal boundaries. If tactics comprise “the art of the weak,” then strategies are the art of the powerful, or of, as articulated by Clausewitz, the “realm”-owners (Arlt 2004). Strategists design their own future environmental conditions, whereas tacticians adapt to current, already-defined conditions.

Temporary urban spaces are manifestations of tactical urbanism that are especially in tune with cyclical rhythms, which urban linear strategies fail to accommodate evenly. Drawing from the studies of Phillip Oswalt in 2013, Claire Colomb in 2012, and Ali Madanipour in 2017, this paper defines temporary urban spaces as city-born tactics that are physically constructed in socioeconomic contexts, which serve to foundationally oppress their formal, permanent implementation. To refer to the creators of temporary urban spaces, Arlt offers “the interim user” as an alternate term for that of “the weak” actors of urban tactics (Arlt 2004). Temporary urban spaces provide non-concrete frames for unevenly accessible amenities, activities, and services. Because temporary urban spaces 1) are built to respond to current resident needs (hunger, community, shelter, etc.) and 2) must engage with impermanence, they align more with cyclical rhythms than do tactical urban structures that are embroiled in landownership, not to mention corporate, profit-oriented strategies.

Temporary urban spaces grow on the grounds of linear urban rhythms, arising from them and bringing light to them. The dissolution of these spaces can catalyze critical attention to linear rhythms, as a temporary urban space is prone to disband for reasons such as a lack of funding, a shift in the need that it serviced, or the city use or corporate purchase of its land. This last scenario can lead to a permanent space that is inspired by the very purpose of the same location’s previous temporary space. The intricacies of this process will later be examined through the case study of Arena Berlin, a concert venue that was formalized by city government but initially organized by interim users. To approach this analysis critically one must consider discourse among urban theorists and architects about which actors should be entitled to implement tactical urbanism, including the creation or molding of temporary urban spaces. Arlt argues that the city should learn ways to move formal planning strategies towards a more “tactical discipline,” in which visions for the city are paired with the present rather than the future (Arlt 2004). In consideration of how this rhetoric has been mobilized, Mould warns, “Despite its origins in community-led, activist, unsanctioned and even subversive activities, TU [Tactical Urbanism] is becoming (if it is not already so) co-opted by prevailing ‘neoliberal development agendas’” (Mould 2014). While the formalization of temporary urban spaces amplifies solutions that residents have identified are needed in city planning, at the same time it also “co-opt[s]” them, making them vulnerable to serving a city’s economic development.

To better understand the origins of temporary urban spaces, they should be studied alongside economist Saskia Sassen’s concept of “The Informal Economy” (Sassen 1994). She affirms Mould’s “tactical” informal economy by stating that “The scope and character of the informal economy are defined by the very regulatory framework it evades” (Sassen 1994). When read through the lens of tactical urbanism, the regulatory framework strategizes and the informal economy adapts. In the United States, the overlap between the informal economy and temporary urban spaces is linked to the

disparity of income levels brought on by the post-Fordist era, starting in the 1970s (Sassen 1994; Oswalt 2013). The informal economy is a network through which low-income city residents sell unregulated services to the service workers of the formal economy, who cannot afford what is offered by the formal realm in which they work (Sassen 1994). These informal exchanges often manifest in more temporary urban spaces, such as flea markets and food stands (Sassen 1994). Increased urban vacancies caused by the post-Fordist era’s shift to labor outsourcing and an information economy further encouraged temporary urban spaces, providing them physical grounds for interim-user occupation (Oswalt 2013). Sassen and Oswalt agree that in municipalities that experienced a rise of the information economy, increased economic polarization and its subsequent spatial manifestations contributed to the spread of the informal economy, and eventually, temporary urban spaces.

Saskia Sassen argued in 1994 for the regulation of the informal economy, but in her conversation with Philipp Oswalt—recorded in Urban Catalyst (2013)—, Sassen expresses how her diverging perspective on informal, temporary urban spaces hinges on an appreciation of terrains vagues (Solà-Morales 1995). While interviewed, Sassen references terrains vagues—which means “wastelands” in French—as spaces that “allow many residents to connect to the rapidly transforming cities in which they live, and subjectively to bypass the massive infrastructures that have come to dominate more and more spaces in the city” (Oswalt 2013). Sassen concludes that, “from this perspective, pouncing on terrains vagues in order to maximize real estate development would be a mistake” (Oswalt 2013). Here, Sassen argues that the formalization of space cannot, in its current capitalist form, simultaneously incorporate and preserve terrains vagues because real estate is part of an institutional system that terrains vagues inherently subverts. While both urban scholars highlight the informal economy and informal planning as inspirations for a less linear form of city planning, the two forms of urban tactics differ because interim users are not primarily motivated by profit-making, whereas participants in the informal economy are (Arlt 2004). Analyzing these two interrelated concepts alongside each other highlights that the risk in formalizing temporary urban spaces lies precisely in their sedimentation and commodification, qualities that are antithetical to their cyclical, situational, and tactical purposes when deployed in the informal economy.

Conversations like Sassen and Oswalt’s underscore the increasing prevalence of governmental and corporate interest in enacting tactical urbanism, and in doing so beg the question: what investments are the profit-seeking forces of a city making when funding an asset that is not inherently economic? Claire Colomb explores this in her book, Staging the New Berlin, through the example of the Berlin government’s push in the early 2000s to globally advertise tactical urbanism happening around the city (Colomb 2012). One example she details is Strandbar Mitte, the first of many beach bars during its time. These beach bars could be considered urban tactics as well as participants in an informal economy because they were “leisure-oriented,” “temporary uses” that popped up in empty sites in relatively low-rent, vacant neighborhoods (Colomb 2012). Rather than dissuading this illegally implemented space, Berlin spotlit it, in what she describes as an attempt to cater to “[t]he consumption practices of, in particular, professionals involved in the cultural and knowledge-based industries” (Colomb 2012). Today, many of the once-informal beach bars, including Strandebar Mitte, still exist as

tourist destinations. Colomb conjectures that because a faction of people looking for work and homes is attracted to innovative urban practices, cities can successfully advertise tactical urbanism to commodify spaces that were once outliers to the city’s linear rhythm (Colomb 2012).

Richard Florida attributes these private and government interests in tactical urbanism to the increased prevalence of the “creative class” (Florida 2012). He defines the creative class as a socioeconomic categorization born out of the post-Fordist shift to an information economy whose companies ultimately seek creative and innovative employees (Florida 2012). He further emphasizes young, single workers of the creative class as especially desirable for cities to attract and retain due to their high-paying jobs, few fiscal obligations, and desire to socially experience the city (Florida 2012). In general, the creative class has the means to contribute to the local economy while also imbuing liveliness into the city fabric. On attracting a creative class, Florida writes that it should be done “not all at once and from the top down—most of what defines and shapes creative communities emerges gradually over time,” and instead through “smart strategies that recognize and enhance bottom-up, community-based efforts” (Florida 2012). Temporary urban spaces, which are not relatively long-lasting, but nevertheless “community-based,” complicate Florida’s suggestion; he implies that a temporary space does not have the power to influence a city’s demographic in the same way that a permanent space does, but encourages permanent spaces to be designed with methods similar to those of temporary urban spaces, specifically for the purpose of attracting well-paid young people (Florida 2012).

Attracting this worker demographic was exactly the goal of the two architecture projects conducted by the architecture firm ZUS in response to vacancies and safety concerns in the area around Rotterdam’s Central Station (Van Boxel et al. 2018). The first project described by the firm in their report, “City of Permanent Temporality,” is Luchtsingel, a walking bridge that connects Pompenburg, a city plaza undergoing major development, to Rotterdam’s central district. The firm states that although the demolition of the bridge was written into its budget, hope remained that “proactive investment in public space would lead to investment in private real estate” (Van Boxel et. al 2018). Attracting investment in private real estate was the goal of ZUS’s 2013 project, 24Hofpoort. This project turned Hofpoort Tower into a “24-hour city” to study ways Rotterdam residents might use its spaces as part of a test stage for the building’s redesign.

While both Luchtsingel and 24Hofpoort started with a community-oriented design process similar to one that a tactical, temporary urban space might follow, both projects only used the temporary structure to linearly increase monetary value by attracting a creative class to Rotterdam. This is true of Hofpoort Tower in particular, which was accessible to all residents during its temporary “testing stages,” but not after 24Hofpoort was partially sold to a Czech investor. This international developer turned “the building’s lower seven floors into flex-work offices,” spaces signature of the alternative working structures favored by finance and tech-related employers of the creative class (Boxel 2018; Florida 2012). Luchtsingel has also shifted from its once temporary implementation; developers of office and shopping units in Pompenburg relay plans to “retain the temporary Luchtsingel as a permanent feature” (Studioninedots 2023, “Pompenburg - Studioninedots”).

As evidenced by 24Hofpoort, when landowners of city spaces

use tactical urbanism as inspiration for ways to attract the wealthy creative class to a city, they undermine tactical urbanism’s purpose of making neighborhoods more accessible to more marginalized residents. As argued by Harvey Molotch in “The City as A Growth Machine,” landownership is an economic investment in not only a parcel of land, but also in its adjacent parcels, which together form a neighborhood (Molotch 1976). Of the interconnection between urban landowners, he states that “one sees that one’s future is bound to the future of a larger area, and that the future enjoyment of financial benefit flowing from a given parcel will derive from the general future of the proximate aggregate of parcels” (Molotch 1976). Because tactical urbanism is desirable to a socioeconomic demographic that is willing to pay for it, its features have been increasingly commodified and therefore increasingly inaccessible for low-income residents. Molotch’s theory of interdependent land parcel values explains how co-opting tactical urbanism has the potential to increase the value of an entire neighborhood, especially of land most proximate (Molotch 1976). Oli Mould criticizes this “neoliberal” real estate method, stating, “it represents the latest cycle of the urban ‘strategy’ to co-opt moments of creativity and alternative urban practices to the urban hegemony – it is the new Creative City” (Mould 2014).

Insofar as land value is driven by desirability, the longevity of formal urban spaces will be inextricably linked to how effectively their messaging and advertising attract a plentiful and wealthy demographic. While multiple factors can contribute to this achievement, high on the list is the trendiness of a space’s intended use. Richard Florida claims trendiness is attained when a city closely embodies not resident-level, but creative-class-level needs and wants, a cityscale reflection of the adage, “dress for the job you want, not the job you have” (Florida 2012). To better encapsulate the desires of the desired class, the architecture firm ZUS enacted the strategy of using experimental, short-term urban implementations as test stages for informing more permanent structures. The aim to control both the audience and timescale can help sharpen an otherwise blurry distinction between formal, short-term spaces, like Luchtsingel and 24Hofpoort, and informal temporary urban spaces. Whereas the tactical methods of the latter sense and respond to existing rhythms in a city, the strategies of the former impose on it a linear projection of time rooted in landownership, which reaches toward a demographic and economic goal.

But these differences between audience and timescale which delineate the informal and formal are not necessarily static. Claire Colomb exemplifies this in her description of previously temporary urban spaces in Berlin. The demographic of these spaces, after being marketed by the city to attract tourism, transformed from interim-users to young out-of-towners with access to disposable income (Colomb 2012). The spaces that were advertised and recorded by Colomb were specifically ones that held economic purposes or were connected to what Sassen might call Berlin’s informal economy (Colomb 2012; Sassen 1994). The beach bars Colomb studied, for example, even before being regulated, had potential to facilitate economic activity in a neighborhood. When a beach bar attracts paying customers, the visitors may also notice and visit neighboring establishments; all aggregate land-parcel owners benefit. The more influence that the informal economy has on a temporary urban space, the more the space can lend itself to linear urban rhythms, despite the extent to which it once stemmed from addressing cyclical resident needs.

The potential for profitability indicated by the presence of informal

economic activity in informal spaces has not gone unnoticed by both private and governmental landowners. The consequence is that these entities appropriate what they deem as trendy deviations from normative means-making and place-making processes. As touched on by Oswalt and Sassen, this process of formalization threatens the existence of authentic terrains vagues. The following case studies investigate how this vulnerability to private and governmental appropriation corresponds with a space’s ongoing physical and ideological malleability. To examine the specific pressures that these spaces face, this paper will rely on Colomb’s and Florida’s descriptions of aesthetically ground-up, yet in essence corporatized, urban efforts for attracting the creative class. To describe varying interim-user responses to these pressures, this paper will utilize the military general Carl Clausewitz’s contradistinctive definitions of “tactics” and “strategies,” as they are contextualized in urban theory by Arlt’s and Mould’s discussions of tactical urbanism. The terms “cyclical” and “linear,” drawn out by Lefebvre and Madanipour, will be used to distinguish between the separate rhythms, or embodied patterns, behind these interacting forces. “Cyclical” will describe tactics that evaluate and adapt to imbalances in the urban ecosystem which threaten biological human needs of shelter and community, and “linear” will characterize the strategies that govern the city with fixed goals of financial gain. The following case studies and discussion will rely on and continue to interrelate these concepts developed by past scholarship.

Discourse regarding temporary urban space largely consists of architects who formalize it and document their processes. It is pertinent to critique these methods of formalization to ensure that they do not override the social infrastructure (Klinenberg 2015) built by a community’s residents. Philipp Oswalt concisely articulates this dilemma from his perspective as an architect: “in view of this Sisyphean task, we will be bound time and again to dissolve existing formalizations and formalize informal practices and integrate them into established structures” (Oswalt 2013). In Urban Catalyst, he examines the role that urban scholars and planners have played and should play when working with ground-up designs for urban spaces, but he approaches his analysis from a different stance than Richard Florida’s in The Rise of the Creative Class from 2012 (Oswalt 2013). Whereas Florida focuses on the economic assets that innovative planning can offer cities and private companies, Oswalt discusses how cities have interacted with temporary urban spaces in ways that have either enhanced or stunted their non-commodified nature and cyclical rhythm.

This paper will continue the study of two temporary urban spaces mentioned in Oswalt’s 2013 book Urban Catalyst, Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal and Arena Berlin. Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal remains as a temporary urban space today that has occupied three different locations over the last 30 years, while Arena Berlin was once a temporary urban space that has been privatized under a long-term land lease by the Berlin government. Though they were born in similar contexts, the two projects have evolved drastically differently. A paper called “Temporary Use of Vacant Spaces in Berlin” by Ikeda Mariko from 2018 provides an in-depth study of the influx of temporary urban spaces that arose in 1990s East Berlin, the context in which both Arena Berlin and Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal originated (Mariko 2018). In 1989, the Berlin Wall, which had previously separated East and West Berlin, was disestablished, and free passage between the two Berlins was renewed. Following this

event, a combination of many vacant properties, confusion over property rights, and a shift of industries in East Berlin led to a suddenly high concentration of temporary urban spaces (Mariko 2018). In her interview with Oswalt, Saskia Sassen comments on the lack of topdown infrastructure in Berlin during this time of rebuilding: “Ironically, the lack of development kept the city going as a cultural center after the Wall came down” (Oswalt 2013). RQWK and Arena Berlin are case studies of the alternative, community-based movements that brought fresh, cultural vibrancy to Berlin.

Arena Berlin’s massive, warehouse-like main hall stands as a reminder of its original purpose as a 1920s bus depot. Its detailed architecture nostalgically reflects its design during the city’s “Golden Age” of economic stabilization and increased attention towards the fine arts. The primary use of the bus depot’s building changed for the first time during the Third Reich when it was used as an arsenal for Nazi soldiers. In the following years, it was used as a refugee camp, and then, in 1989, as a bus depot once again (Arena Berlin 2023, “History”). The physical form of the bus depot’s main hall remains today, and is versatile due to its vast, unobstructed interior and surrounding smaller buildings. In particular, when barred from access after its transition back to a bus depot, in 1993, tactical, interim uses stemmed from what were then Arena Berlin’s adjacent administrative buildings (Arena Berlin 2023, “Home”).

Philipp Oswalt documents Arena Berlin’s stages of transformation in Urban Catalyst from 2013. Up until 2013, a man who had been part of occupying Arena Berlin since 1995, Falk Walter, managed the space privately since the year 2000 (Oswalt 2013). Having changed leadership three times in about 10 years, Arena Berlin has consistently stayed a hub for performance arts since the 1990s. But varying structures of leadership and occupation have resulted in varying performers and audiences. In the 1990s, while the main hall was in use as a bus depot, a community of artists began to use the hall’s surrounding structures as spaces for artists to live and perform. While this part of Arena Berlin’s history is briefly mentioned in Oswalt’s records in his 2013 book, it receives little attention from other sources. Arena Berlin’s website excludes it altogether, only beginning its account of the space in 2000 (Arena Berlin 2023, “Arena Halle”). A reason for this could be that the wider interim user community was largely muffled by Falk Walter’s non-profit organization, Art Kombinat, which emerged from, but did not encompass, the entirety of the space’s users. As more and more interim users in the Arena joined Art Kombinat, the organization began implementing new capitalist structures—such as renting out parts of the building—leading to what Oswalt poses as one of the first structural shifts of the Arena’s use as a performance space (Oswalt 2013). He further states that though these efforts were not economically successful under Art Kombinat’s leadership, they drew attention to the potential that the space had as a formal, commodified performing arts venue (Oswalt 2013).

Today, Arena Berlin appears in articles ranging from those advertising a contemporary performance by the Berlin Philharmonic (Cooper 2018), to those advertising a newly touring synth-rock act, Unhelig (Ferguson 2010). Largely by the crafting of Falk Walter, Arena Berlin is now undoubtedly—arguably primarily—a commercial space, marketed as hosting up-and-coming artists, with the main hall rented out for corporate events and talks (Oswalt 2013). The Arena underwent a full renovation over 20 years ago but is still structured

as a conglomeration of smaller buildings surrounding one main hall. Instead of flexible spaces for interim users, the smaller buildings now take the forms of a restaurant and bar, gala spaces, and techno club whose building, despite the renovation, preserves the structural integrity of its original use as a “boiler house” (Arena Berlin 2023, “Home”). While visiting Arena Berlin in November 2023, I found myself amid the aftermath of one of its events and was able to witness the massiveness of the space and the impact it has on its surrounding environment. Under a street sign, demarcated only by the word “Arena” written over an arrow (see figure 1), a line of trucks and vans attempting to turn towards Arena Berlin spilled out onto the busy main street, lining up to pick up rented equipment and furniture (see figures 2 and 3). I was struck by the irony of how the building still corralled an influx of vehicles to its street, depending on these vehicles for its operations, even after a long and varied ownership history since its origins as a bus depot.

Mirroring the Arena itself, its surrounding neighborhood has also undergone a host of transformations in the past thirty years that have contributed to building elements that Richard Florida dubs paradigmatic of the “Creative Community” (Florida 2013). Notably, Oswalt observed that in Kreuzberg, the neighborhood across the Spree River from Arena Berlin, creative industries were on the rise: “fashion schools, record labels, clubs, design studios, and handicrafts workshops are part of a powerful development initiated in large part by the Arena” (Oswalt 2013). A walk around the perimeter of the Arena today supports this statement. The brick facade of the building’s perimeter extends towards a pier, from which cranes and modern apartment and office buildings crowd the skyline of the opposite riverbank. Between the pier and Kreuzberg towers a sculpture of two silhouettes in the middle of the river (see figure 4). Kreuzberg was not always so extravagantly developed. In Claire Colomb’s 2012 discussion of the ways in which alternative cultural aspects in Berlin have been advertised to attract creative residents, she states, “Berlin’s ‘ordinary’, socially and ethnically mixed neighbourhoods (such as Kreuzberg), and their ‘authentic’ as well as alternative and counter-cultural life, have increasingly been portrayed as tourist attractions or potential settings for young creative entrepreneurs in marketing campaigns and publication” (Colomb 2012). From an evening’s scan of the city space surrounding the Arena, new developments and an active nightlife model as fruits of the labor of the promotional campaigns that Colomb describes (see figuress 4 and 5).

The occupancy of the Arena has vacillated between private and interim forms over the past thirty years and is now private once again. Falk Walter was able to facilitate the most recent shift from interim use to formalized, private occupancy through a 35-year lease. This lease was awarded to him and Art Kombinat by the city of Berlin after Art Kombinat hosted a massive music festival in the late 1990s. This long-term lease was intended to continue the space’s use as a cultural center, though this was only one of the multiple profitable ventures undertaken by Walter. Oswalt states, “The length of the lease was the deciding factor that catalyzed the use and development of the area as a whole” (Oswalt 2013). As Richard Florida observes, attracting the creative class happens “gradually, over time,” and this necessary time was allotted to Falk Walter via government subsidy (Florida 2012). In the instance of Arena Berlin, the interim users who hosted a large-scale, 46-day music festival (Oswalt 2013), and could therefore demonstrate the space as profitable, were able to continue occupying it, while other interim users were all but erased from the

space’s present form and archived history.

The history of the residential community originally called Schwarzer Kanal, or “Black Kanal,” is long and multifaceted, but consistently situated in the non-linear rhythm of temporary urban spaces. In 1990, Schwarzer Kanal was a squatted, trailer community that occupied a vacant plot of land along the Spree River, near the center of the city of Berlin. The city government permitted Schwarzer Kanal to occupy the land without interference until 2002 when it turned the

land over to Hochtief, a development company, at that time constructing a service worker union. After negotiations, Hochtief agreed to grant Schwarzer Kanal medium-term rights to move to another one of their undeveloped plots in a nearby neighborhood known for office real estate (Oswalt 2013). This new location was spatially divided by two plots, Köpenickerstrasse and Michaelkirchstrasse, and so were the members of Schwarzer Kanal. As they were divided geographically, an ideological rift simultaneously formed; issues concerning sexist community members led Michaelkirchstrasse to become a settlement for “women-lesbians” while Köpenickerstrasse remained “mixed.” Eventually, in 2010, Schwarzer Kanal moved to

Neukolln, where they remain today. In 2013, the original three-year land use agreement under which they relocated expired, and, after over three more years of re-negotiating and informal occupation, a new lease with the government was established, which halved their permitted land area. According to the website’s latest news update in 2021, these are the current grounds for their occupation (RQWK 2021, “New Shoes for Kanal”). In this most recent location, the name of the project has changed to “Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal,” or RQWK, by which they commonly refer to themselves and will be referred this paper for sake of brevity (RQWK 2016, “History of Occupation”). Throughout these shifts in location, the membership

size, mission and demographics of RQWK have all adapted flexibly and reflexively, too.

As their new name indicates, RQWK has become a home for otherwise historically marginalized people. However, the community openly reflects in its public statements that this has not always been the case. As previously mentioned, the first major division of RQWK occurred both spatially and ideologically in their second location in 2002, when they were divided into Köpenickerstrasse and Michaelkirchstrasse (see figure 6). But RQWK states that the community’s battle against sexism during that time did not extend to exclusivity based on gender conformity. Eventually, this too was debated, and

the result was another change in RRQWK’s demographics (RQWK 2016, “History of Occupation”). As Michaelkirchstrasse continued as a “cis woman and lesbian-only place” throughout 2002–2007, the residents of this location also began to tackle more intersectional issues of oppression by making strides to be more inclusive towards trans people. RQWK states that this happened only after difficult discourse, but that their community eventually became a home, as well as an event space, for Trans Berlinites (RQWK 2016, “Political Statement”).

Still, at this stage, a significant majority of the collective remained white and German. This changed after RQWK was forced to move to their new location in Neukolln, where they were granted by the Berlin government a few years of guaranteed land rights and the subsequent ability “to reflect more intensely on the structure of the project (e.g. in relation to classism, racism, transphobia…)” (RQWK 2016, “Political Statement”). The RQWK website states that the internal investigation into racism and exclusionary aspects of the residence started in the summer of 2014 by “BPoC that came to live in the place and were not willing to deal with the racism” (RQWK accessed 2023, “History of Occupation”). Now, granted after a mass exodus of disapproving residents, RQWK has a majority BIPOC, LGBTQ+ demographic, and publicly specifies intersectional and reparative ways of living as crucial to their mission (RQWK 2016, “Political Statement”).

“Schwarzer Kanal” has been able to evolve into “Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal,” and the primarily Black, Indigenous, People of Color and Queer space that it is today because it has cyclically grappled with permeating, oppressive social norms without being limited by the fear that a continuously changing, and sometimes shrinking, community will detract monetary value from the land which it occupies. Thus, RQWK has, in all its iterations, kept space for critical reflexivity. In their latest online statement, “Political Statement of Radical Queer Wagenplatz KANAL,” RQWK proclaimed, regarding the impact that temporariness has had on their community, “whenever it is about changes, the first reaction is resistance. Deconstructing and/or [losing] power are consequences of this – which privileged people who have benefited from the structure before, are not used to. Changes confront people and make positions more visible” (RQWK 2016, “Political Statement”). This comment was made in reference to the members of RQWK who left after BIPOC residents’ critiques of the community began to be taken seriously. Rather than market their space to attract and retain a consumer base, RQWK takes a more cyclical approach, uplifting demographic change as a tool for exposing and “deconstructing” power dynamics.

This research on RQWK aims to examine how tactical occupation manifests in a community uninvested in the linear, profit-motivated strategies of advertising, interest in adjacent land parcels, and curating economically profitable demographics. In that “tactics” resist and contrast “strategies,” the use of the term “tactical urbanism” in relation to RQWK implies that the temporary aspect of the community’s structure is a method of adaptation rather than a goal. This is important to note because the existence of RQWK not only serves the needs of community-building and creativity among low-income, queer, non-white residents of Berlin, but also primarily serves their needs for shelter. RQWK, despite its various projects, is primarily a home for people who are affected by a looming threat of displacement (see figure 7). Though not unique to the community, or even to the city of Berlin for that matter, the correlation between socioeconomic status and vulnerability to displacement is potent in the history of moving locations that RQWK has had to undertake.

This vulnerability manifests in a protective and isolated atmosphere, making the space, arguably, the opposite of advertised. After sending a message to the email address listed on RQWK’s website, as well as to their Instagram social media account (though their last post was in 2021), I did not receive a response from the community in regard to my request to visit the space or speak with a member. I decided to walk to the address anyway, which was listed publicly on their website and only 20 minutes away from Arena Berlin, in case it was open to visitors. It was not. When I arrived at around 5:30 pm, the gates were closed, though a couple of residents walked in and out. The surrounding fence was tightly slatted, offering almost no visibility of the community from the sidewalk. At that point, sensing clearly that RQWK’s priorities were purely residential for that time, I walked around the neighborhood on the street, Kiefholzstraße. The land that RQWK occupies in 2023 is a small plot of dense woods that interrupts a peripheral urban landscape otherwise dominated by wide roads and construction sites. Most notably, about four minutes from the community is an overpass that overlooks a newly paved and not-yet-opened portion of the German Autobahn (see figuress 8 and 9). Graffiti on the sign for the construction project reads “Stop Versigelung,” a German phrase that translates to “Stop Sealing.” “Sealing” is referred to by several German sources as a practice for strengthening highway pavement that increases the heat that asphalt attracts and limits the permeability of rainfall, increasing the risk of flooding in the surrounding neighborhood (Berlin.de 2023, “Versiegelung”). RQWK’s new location is rife with aspects that are

widely considered unattractive to potential homeowners and renters, as evidenced even by the graffitied demand.

RQWK itself is one such unattractive aspect, according to Claire Colomb’s Berlin-based claim regarding the representation of temporary urban spaces in media; she states, “only certain types of entertainment-related, ludic temporary uses are portrayed. Trailer sites and alternative living projects deemed too radical and politicized are, unsurprisingly, not featured” (Colomb 2012). Her description of how the city and its companies tend not to advertise “radical” spaces, like RQWK, blatantly contrasts with Arena Berlin’s hefty media presence. This difference indicates that the city’s landowners prefer to platform profitable displays of counterculture over ideological ones. It is simultaneously true that RQWK does not consistently advertise itself, sheltering its residents with a nondescript location and lack of media presence.

I also visited RQWK’s original location, on Köpenicker Straße along the Spree River, to discern how the site had developed since the community’s first eviction in 2002. On a plot of land that was once home to 25 residents (RQWK 2023, “History”), now stands a massive office complex called “Ver.di,” the headquarters for Germany’s service trade union (see figure 10). At about 2 million members (ver. di 2023, “Über Uns”), the union is sizable in both numbers and in physical structure. Though Ver.di is only accessible to union workers and not the general public, I was able to see its open-layout design by peering inside through a Spree-facing glass facade. The high ceiling covering the building’s wide-open and empty atrium was also glass, blurring the division between inside and outside. Across the street is Køpi, another 1990s-born squatter community that still occupies its building without a lease, and is reportedly currently appealing the eviction of its outdoor “wagenplatz” homes. The site of Køpi, like RQWK’s Neukolln location, is surrounded by construction. The property next to Køpi is currently cleared for construction and surveilled by people in a windowed cargo box on its grounds. On Køpi’s construction-facing brick wall is the graffitied phrase: “HANDS OFF OUR HOMES” (see figure 11). Evidently, the dissonance between tactical urbanism—“landing of Blows on another’s land”—and new construction is still prominent in the original neighborhood from which RQWK was displaced.

Perhaps the most blatant, tangible difference between RQWK and Arena Berlin today is the visibility of the people that they service. Successful advertising of Arena Berlin is a feat measured linearly and accomplished exponentially; the more members of the creative class that the space attracts, the more attractive the space is to the creative class. This conclusion is supported by Richard Florida’s 2012 theory that the creative class values socializing with its fellow members, and also from observing a line that formed around the venue for a pop-up “Qweer Market.” While visiting Arena Berlin, I stood in a 5-minute-long line at 5:00 pm that became well over 30 minutes long by 6:00 pm. The line was for Arena Berlin’s market space, where “Qweer Market,” a market for queer art and zines, was being held (Qweer Market 2023, “Here we are today 13:00–21:00”). Whether it be through word of mouth or catching the attention of passersby, the sudden growth of the line—for a market that had been running the entire day—seemed to me an apt metaphor for the general advertising strategy of the Arena: exhibit and commodify subculture to attract more and more people. This is not, of course, a critique of Qweer Market, which platforms LGBTQ+ voices and art, but instead, an observation of Arena Berlin’s success in transforming a building

once inhabited by squatters and interim users to one that people pay for and line up to enter, whether it be to see the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra or shop at the annual Qweer Market.

In contrast to Arena Berlin RQWK implies, even in its name, a desired demographic that they welcome, and does not encourage vast numbers of visitors. RQWK has held some events such as a winter festival and a birthday party for the community in the past (RQWK 2022, “KANAL WINTER SOLI FESTIVAL”), but has not publicized one since December 2022. Additionally, RQWK emphasizes that admittance is conditional—for straight, cis-gendered, white visitors in particular—in the messaging of their online presence (RQWK accessed 2023).

Their website specifically asks:

White and white passing individuals who participate in the living project are understood to carry a responsibility of helping build the space and take on some of the various labor tasks involved in the upkeep of the project, without centering themselves or their narratives as a form of historic reparations and praxis. (RQWK 2023, “History of Occupation”)

In this statement, RQWK posits their priorities as primarily contextually developed and communally upheld, rather than emerging from the top-down strategy of pandering to plentiful patronage.

Referring to their day-to-day embodiment of an ideal community as their “living project,” RQWK’s ideology is based in the everyday lives of residents as well as contextualized in varied histories of marginalization and trauma. RQWK asks its members to acknowledge their privileges, and it offers a space to practice minimizing the harmful impacts. RQWK’s website emphasizes that “all people, regardless of racial or gender identity, are equals in the space, especially when it comes to decision-making” (RQWK accessed 2023, “History of Occupation”). This statement, in conversation with their living project, highlights how the community views historical oppression not as a force of the past, but as actively deleterious today. RQWK therefore poses privilege as necessary to address in order to work toward a community of “equals.”

RQWK resists what authors Barca et al. refer to in their article, “The End of Political Economy as We Knew It?,” as “growth realism,” or the idea that, as a means to any collective future, there is no alternative other than to strive towards economic growth (Barca et. al 2013). The word “realism” indicates the propensity that the perspective has to naturalize a system that was socially imagined into being. Barca et al. propose what they deem an inherently political term, “nomadic utopianism,” as an ideological alternative to growth realism (Barca et. al 2013). Nomadic utopians are necessarily political because they do not succumb to institutional restraints when working toward embodying their ideals. Instead, they adapt organizational structures cyclically as their circumstantial perspectives morph. In this way, the constant flux of nomadic utopianism contrasts with the growth realist’s linear conceptualization of utopianism, which plans concrete steps for achieving a future goal (Barca et. al 2013). Arena Berlin, on the other hand, has adopted the growth realist perspective under Art Kombinat’s leadership and assisted by a government grant. It has thus shifted away from temporary urban space, by its definition in this paper, to a space that conforms and enables the capitalist structure of landownership described by Harvey Molotch in 1976.

The contrast between these two case studies suggests to me that

the term “temporary urban space” may need to be reconceptualized as a space that will inevitably change ideologically, spatially, or ideologically and spatially. The origins of Arena Berlin can still be considered a temporary urban space even though its new form exists in the same location because the use of the space has switched from being flexible, evolving, and need-based, to linear and heavily monetized. From the moment that its profit potential was recognized by forces with the means to invest, Arena Berlin was formalized, exploited, and advertised. There are two frames through which to analyze this transition: 1) the space was less vulnerable to aggregate landowners because it had capitalist potential and therefore potential for longevity in physical existence and 2) the space’s original interim users were more vulnerable to profit-seeking individuals because the latter had more powerful, monetary means to co-opt its use.

When city governments and private entities co-opt the infrastructure for tactical urbanism and temporary urban spaces without adopting their cyclical ideological and emic rhythms, tactics for urban “liveability” are appropriated as strategies for accumulating land value. Increasing attention towards tactical urbanism has been widely attributed to the prominence of “creative class” (Florida 2012), but the origins of temporary urban spaces are discussed more site-specifically. In the case of Berlin, scholars position temporary urban spaces at the intersection of East–West reunification and terrains vagues, conditions which in coincidence laid the grounds for nomadic utopianism by means of re-envisioning landownership. Under RQWK’s interim users, the community became grounds for nomadic utopianism, while Art Kombinat of Arena Berlin used the space’s former temporary status to experiment with methods for kickstarting profitability.

Architect Rance Mok in 2010 discusses a specifically spatially enacted form of nomadic existence, that of the urban nomad, and states that the term “nomad” originated as a colonialist categorization of indigenous pastoralist tribes (Mok 2010). Discussing the term’s connotations today, Mok states, “a Nomad is deemed different from the norm by way of his spatial practice” and that “his relationship to the land seems less defined than that of the propertied system” (Mok 2010). RQWK’s community’s safety and social action are endangered by displacement, so moving locations should by no means be implied as its purposeful goal. But, even if not on purpose, between RQWK’s “living vision” and physical structure two cyclical rhythms intertwine; as RQWK’s structure changes and moves, the community, as reflected by a number of its public statements, self-reflexively names its prejudice, works to address it, and then re-examines for new ones to eradicate.

Temporary urban spaces that are appropriated with the intent of economic growth are susceptible to the mechanisms through which landownership ascribes power in cities. While Arena Berlin was commodified and remained stationary along the Spree River in Kreuzberg and RQWK was displaced from its Spree-adjacent property, within their life spans, both of the plots’ surrounding neighborhoods have transitioned from terrains vagues to newly developed office buildings, bars, concert halls and apartments. Whether Arena Berlin and RQWK’s relative commodification and displacement were causal or resulting factors of neighborhood change is a question for future research, but this paper will extend to conjecture that it was potential for profitability that made Arena Berlin physically resilient, yet inevitably prone to a hegemonically imposed linearity, and a lack of profitability which resulted in RQWK’s consistent displacement, but also its persisting nomadic utopianism.

The many times that RQWK has had to move in comparison to Arena Berlin evidences that landownership can disempower non-economically motivated communities in cities. Temporary urban spaces take various forms—gathering spots, performance venues, outdoor film screenings, etc.—and each form is vulnerable to landownership to a different extent. Informal homes that aim to protect marginalized peoples by implementing cyclical rhythms of reflexivity are simultaneously less at risk for co-option through permanent implementation and more vulnerable to displacement because they cannot be marketed to the creative class. Because a space that is unmarketable to the wealth-bringing class that cities desire is a threat to real estate value, it is forced into building, moving, rebuilding… into a cyclical manner of existence. A study of formalization and landownership in the context of temporary urban spaces reveals that a dialectical rhythm most in touch with resident needs is not favored by current, urban, hegemonic systems. As originally interim-user-generated spaces are perceived as feasibly profitable, they acquire a shot at longevity but simultaneously lose flexible ideological compatibility with the communities that envisioned them.

This paper juxtaposes the linear strategies that have preserved artists’ use of Arena Berlin with the cyclical tactics that have preserved Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal’s nomadic utopianism. These two aspects of the case studies, a specific space’s use and a community’s collective ideological flexibility were both originally born from community-based decisions. However, under state and corporate seizure of land, they became mutually inhibitive within each temporary urban space. This conclusion is well-contextualized in existing scholarship that has detected a pattern of urban government and private entities utilizing terrains vauges to attract members of the creative class. Complimenting Claire Colomb’s study of how these entities mobilize advertising strategies, this paper contributes ethnographic evidence of Arena Berlin’s extensive self-promotion and RQWK’s lack thereof. Specifically, Arena Berlin’s heavy advertising and attendance for its “Qweer Market” connects Colomb’s work on informal spaces in Berlin to Saskia Sassen’s urban economic theory by pointing to how some spaces utilize counterculture messaging as a source for generating income through seemingly informal means. While both RQWK and Arena Berlin hold space for queer residents of the city, the commercialization of the latter only does so for queer residents who are also members of the economically mobile creative class described by Richard Florida.

In future studies on temporary urban spaces, interviews with interim users would add invaluable insight into the process and obstacles of temporary urban place-making with nomadic utopian ideals. The interim-user perspective is particularly underrepresented in the current literature on temporary urban spaces, especially because many of the authors on the subject are architects, themselves designers of formal structures. In this piece too, no interim-user perspective was included. So, although this research revisits two sites surveyed by Philipp Oswalt in 2013 a decade later, it maintains Oswalt’s limited, outsider perspective on them. Perhaps for Oswalt and certainly for me, the absence of input from interim users was not for lack of asking via email and social media. Especially after conducting this research, it does not escape me that RQWK’s lack of response may be indicative of concerns about divulging information regarding its community.

Contextualized in existing scholarship on temporary urban spaces,

this paper’s case study of RQWK speaks to how cyclical forms of community-building evade the ideological linearity of commercialized urban land. In fact, an urban space’s ideological non-conformity poses a risk of its displacement, and therefore increases its likelihood of being temporary in a spatial, structural sense. The case study of Arena Berlin exemplifies an alternate scenario of a temporary urban space that was uprooted ideologically, rather than spatially. By adopting a for-profit agenda, Arena Berlin secured its location and structure, but lost its cyclical rhythm. Arena Berlin’s marketing pursues its capitalist goals deceptively, through strategies that advertise creativity and mask underlying linearity. Arena Berlin is one example of many projects designed by architects, planners, and companies who draw inspiration from temporary urban spaces (i.e. 24Hofport and Luchtsingel). Given the prominence of such projects and their capacities to cause displacement, interim-user perspectives should be incorporated in urban planning and literature for the explicit purpose of promoting cyclicality. The overarching findings in this paper highlight this need, as they illuminate an incompatibility between durable uses of the urban built environment and the flexible values and thought processes of the people it organizes. The applied and theoretical aspects of such an addition to the field of temporary urban spaces would discursively tie less linear values to land-use, and therefore encourage interim-user communities and newly designed structures to primarily support resident needs.

yhb2108@barnard.edu

Oswalt, Philipp, et. al, eds. Urban Catalyst: Powers of Temporary Use. Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2013.

———. “Introduction.” In Urban Catalyst: Powers of Temporary Use, edited by Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer, and Philipp Misselwitz, 7-16. Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2013.

———. “Co-Existence.” In Urban Catalyst: Powers of Temporary Use, edited by Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer, and Philipp Misselwitz, 43. Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2013.

———. “Informal Economies and Cultures in Global Cities.” In Urban Catalyst: Powers of Temporary Use, edited by Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer, and Philipp Misselwitz, 105-116. Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2013.

———. “Arena, Berlin.” In Urban Catalyst: Powers of Temporary Use, edited by Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer, and Philipp Misselwitz, 332-339. Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2013.

“Arena Halle - Die Event Location an Der Spree.” Arena Berlin, February 22, 2023. https://www.arena.berlin/en/location/arena-halle/.

Arlt, Peter. “What City Planners Can Learn from Interim Planners.” Essay. In The Urban Catalyst: Strategies for Temporary Urban Use, 141–46. Berlin: Studio Urban Catalyst, 2004.

Barca, Stefania, Ekaterina Chertkovskaya, and Alexander Paulsson. “The End of Political Economy as We Knew It? From Growth Realism to Nomadic Utopianism.” Essay. In Towards a Political Economy of Degrowth, 1–17. London: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2019.

Boxel, Elma Van, Kristian Koreman, and ZUS Zones Urbaines Sensibles. “City of Permanent Temporality.” Joelho Revista de Cultura Arquitectonica, no. 9 (2018): 22–49. https://doi. org/10.14195/1647-8681_9_1.

Colomb, Claire. Staging the New Berlin: Place Marketing and the Politics of Urban Reinvention post-1989. London: Routledge, 2012. Cooper, Michael. “Notes of Transformation: In Simon Rattles 16Year Reign, the Berlin Philharmonic Became One of This Century’s Most Progressive.” The New York Times, June 26, 2018.

Ferguson, Tom, ed. “Truly Grosse.” Billboard, October 30, 2010. Florida, Richard L. The Rise of the Creative Class: Revisited. New York: Basic Books, 2012.

“History of Occupation.” Radical Queer Wagenplatz Kanal, 2016. https://kanal.squat.net/?page_id=70.

“History.” Arena Berlin, February 22, 2023. https://www.arena. berlin/en/location/arena-halle/.

Hu, Winnie. “Go Play in the Street, Kids. Really.” The New York Times. April 1, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/01/nyregion/ street-lab-open-streets-nyc.html.

Klinenberg, Eric. Heat Wave: a Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. Chicago, Ill: The University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Lefebvre, Henri. Rhythmanalysis. Translated by Stuart Elden and Gerald Moore. London, England: Continuum, 2004.

Madanipour, Ali. Cities in Time: Temporary Urbanism and the Future of the City. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, 2017.

Mariko, Ikeda. “Temporary Use of Vacant Urban Spaces in Berlin: Three Case Studies in the Former Eastern Inner-City District Friedrichshain.” Geographical Review of Japan Series B 91, no. 1 (2018): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4157/geogrevjapanb.91.1.

Mok, Rance Yan Ki. “Nomad in the City: Composing an Architectural Dissonance.” Thesis, 2010.

Molotch, Harvey. “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place.” American Journal of Sociology 82, no. 2 (September 1976): 309–32. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/ stable/2777096.

Morales, Sola. “Terrain Vague.” Anyplace, (1995): 118–23.

Mould, Oli. “Tactical Urbanism: The New Vernacular of the Creative City.” Geography Compass 8, no. 8 (2014): 529–39. https:// doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12146.

“Pompenburg - Studioninedots.” Studioninedots. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://studioninedots.nl/project/pompenburg/. Sassen, Saskia. “The Informal Economy: Between New Developments and Old Regulations.” The Yale Law Journal 103, no. 8 (1994): 2289. https://doi.org/10.2307/797048.

“Versiegelung.” Berlin.de Startseite, May 10, 2023. https://www. berlin.de/umweltatlas/boden/versiegelung/.

“Über Uns.” zur ver.di Startseite. Accessed December 6, 2023. https://www.verdi.de/ueber-uns.

In the wake of the Colombian armed conflict, millions of rural farmers and civilians were forcibly displaced from their homes by paramilitary and guerrilla groups. The conflict lasted for five decades and resulted in changes to national security, a growing influence of illicit drug groups, and a total of seven million internally displaced persons (IDPs). An internally displaced person is defined as a person (or group of people) who “have been forced to flee homes or places of habitual residence as a result of or to avoid, in particular, the effects of the armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights, or natural disasters” (Bennett 1998). The main contributing factor to IDPs in Colombia was violent events through the seizing of land by armed forces, which were then used for illicit logging, illegal crops, increased cattle ranching, and more (Andersson 2021, 8). To deal with the massive influx of IDPs to urban areas, the Colombian government addressed the spatial concerns of displacement through housing initiatives that aimed to prevent informal settlements. I seek to explore how the housing initiatives created by the Colombian government impacted the relationship between IDPs and the lands of their original and new homes, and how the projects reflect the government’s ideological priorities.

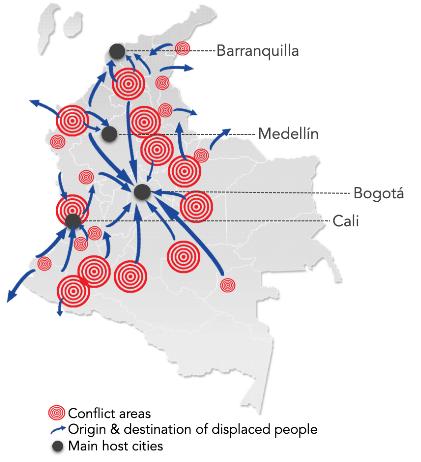

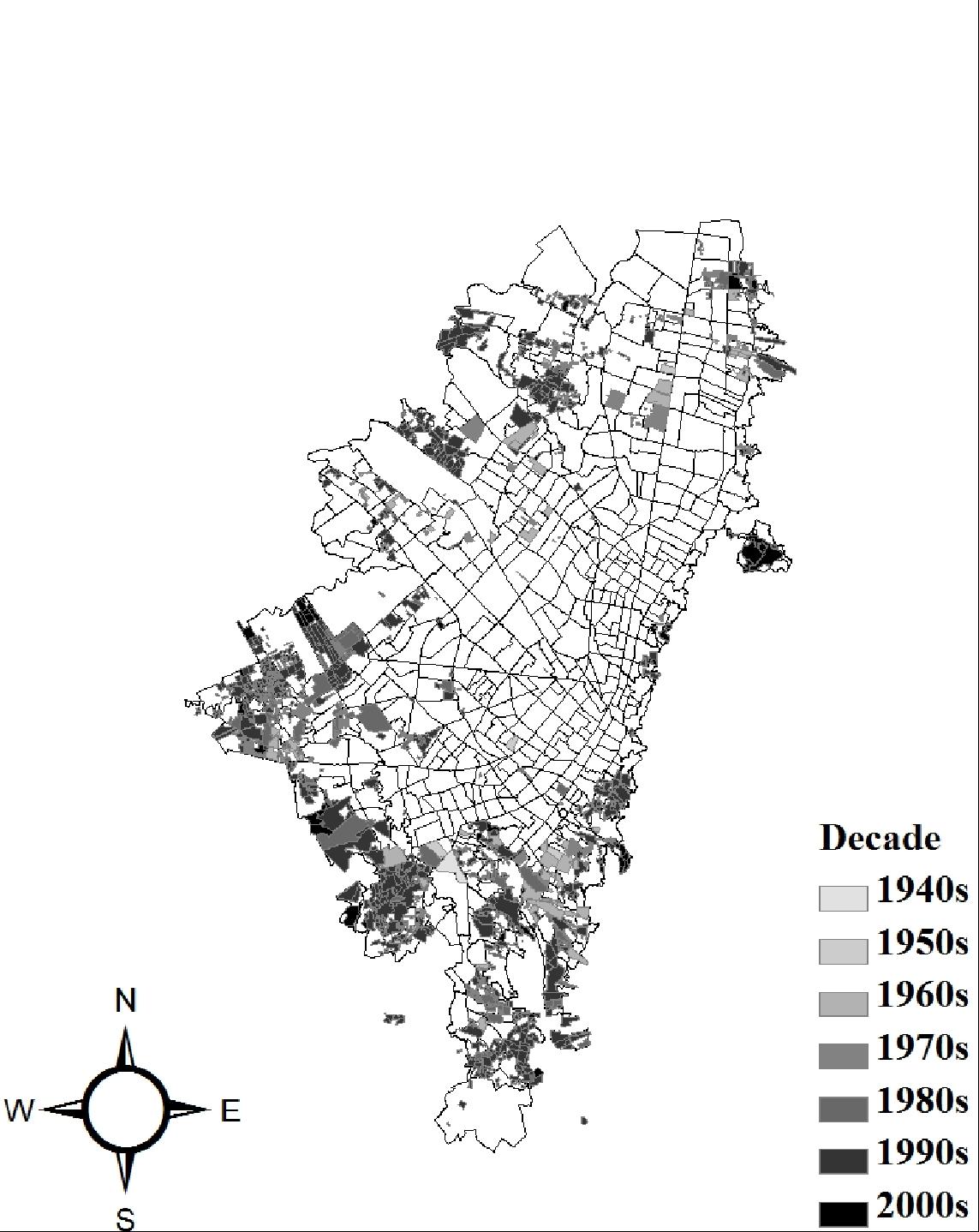

The major Colombian cities—Bogotá, Medellín, Cali, and Barranquilla—can be understood as spaces that reflect the conflicts, disputes, and ongoing practices of the armed conflict and national issues. Starting in the mid-20th century, the influx of rural to urban migration developed in a mostly informal manner; it is estimated that about seventy percent of new houses in Colombian cities were planned through informal squatter settlements and invasions (Silwa and Wiig 2016, 12). Many, but not all, of the migrants in the city were fleeing conflict zones, as shown in figure 1. Additionally, IDPs oftentimes had less formal education, making it more likely for them to be unemployed if not working in the informal sector (Silwa and Wiig 2016, 12). The socioeconomic disparities of IDPs were often further exacerbated by the greater spatial formations of the city, most notable in the capital city, Bogotá. The most common form of land acquisition for informal settlements involved an agent who would claim, subdivide, and resell the land in parcels to migrants to develop their homes through self-building—later known as “pirate urbanizations” (Camargo Sierra 2015, 137). Both factors, education and land division, contributed to the production of built space that occurred in a predominantly self-built manner, further qualifying the informal and often precarious nature of the urban developments that IDPs reside in.

The repercussions of the Colombian armed conflict are present in the greater formation of Bogotá, as exemplified by the disproportionate development of informal settlements in the South of the city. The armed conflict began in 1964; within the decades of the 1960s and 1970s, approximately a quarter of the city was developed in an informal manner, generating approximately 62% of the total informally

Figure 1. Map of internal displacement and migration to major cities in Colombia. Map by Franco Calderón, April 2019. “The Production of Marginality. Paradoxes of Urban Planning and Housing Policies in Cali, Colombia.”

urbanized land in the city within these two decades (Sierra 2015, 138). Bogotá was ultimately planned in a segregated manner by both North-South and center-periphery divisions. As seen in figure 2, the greater conglomeration of informality sits in the southern periphery of Bogotá. Consequently, the segregation of IDPs in Bogotá, and in many other Colombian cities, is not only social and economic but also spatial due to the geographic locations of informal settlements. Although many, if not the majority, of informal settlements are now legally recognized and integrated into the city, the North-South and center-periphery divisions remain today. Residents of informal settlements in the southern periphery of the city often face longer and more expensive commutes to the city, exposure to environmental contamination that contributes to health problems, and overall stigmatization from the status quo (Rueda-Garcia, 19-20).

On a brief personal note, I had the opportunity to conduct research in the summer of 2023 in informal settlements of Bogotá which mostly focused on land use planning issues surrounding environmental risk determinations. The majority of my research occurred in Las Amapolas, a small neighborhood in the San Cristobal locality in the outermost southeastern periphery of Bogotá. I connected with a few grandmothers in the neighborhood who were among the first ten families to purchase subdivisions of land to develop their homes. They shared stories from their childhoods, where they migrated with their families as a child (one of them without her parents) to the capital city due to formal displacement by armed forces. These grandmothers honored their campesina (“peasant” farmer) backgrounds by forming