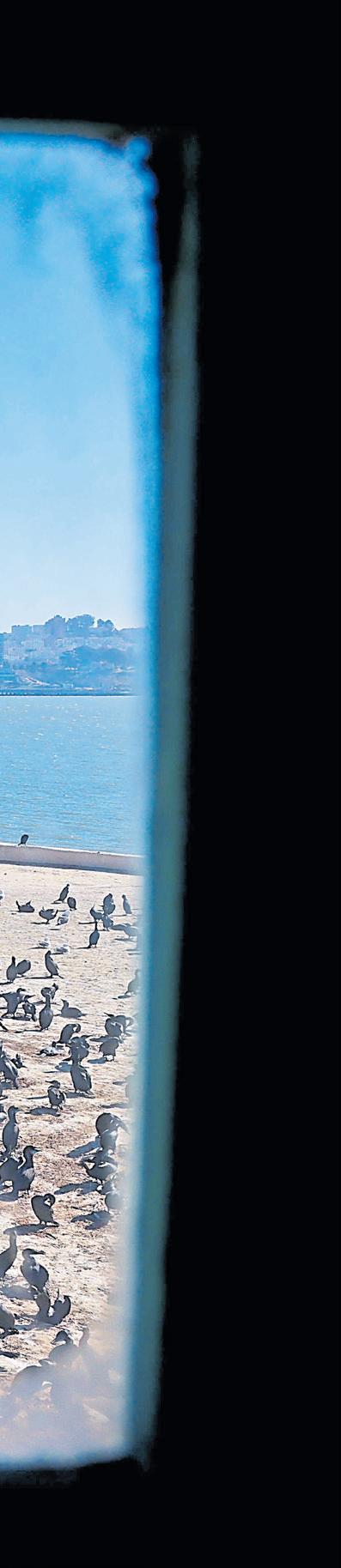

Thousands of birds nest all over the Farallon Islands National Wildlife Refuge. The island has been a hotbed for research on seabirds, sharks and fish for more than 50 years.

RAY CHAVEZ/ STAFF ARCHIVES

Thousands of birds nest all over the Farallon Islands National Wildlife Refuge. The island has been a hotbed for research on seabirds, sharks and fish for more than 50 years.

RAY CHAVEZ/ STAFF ARCHIVES

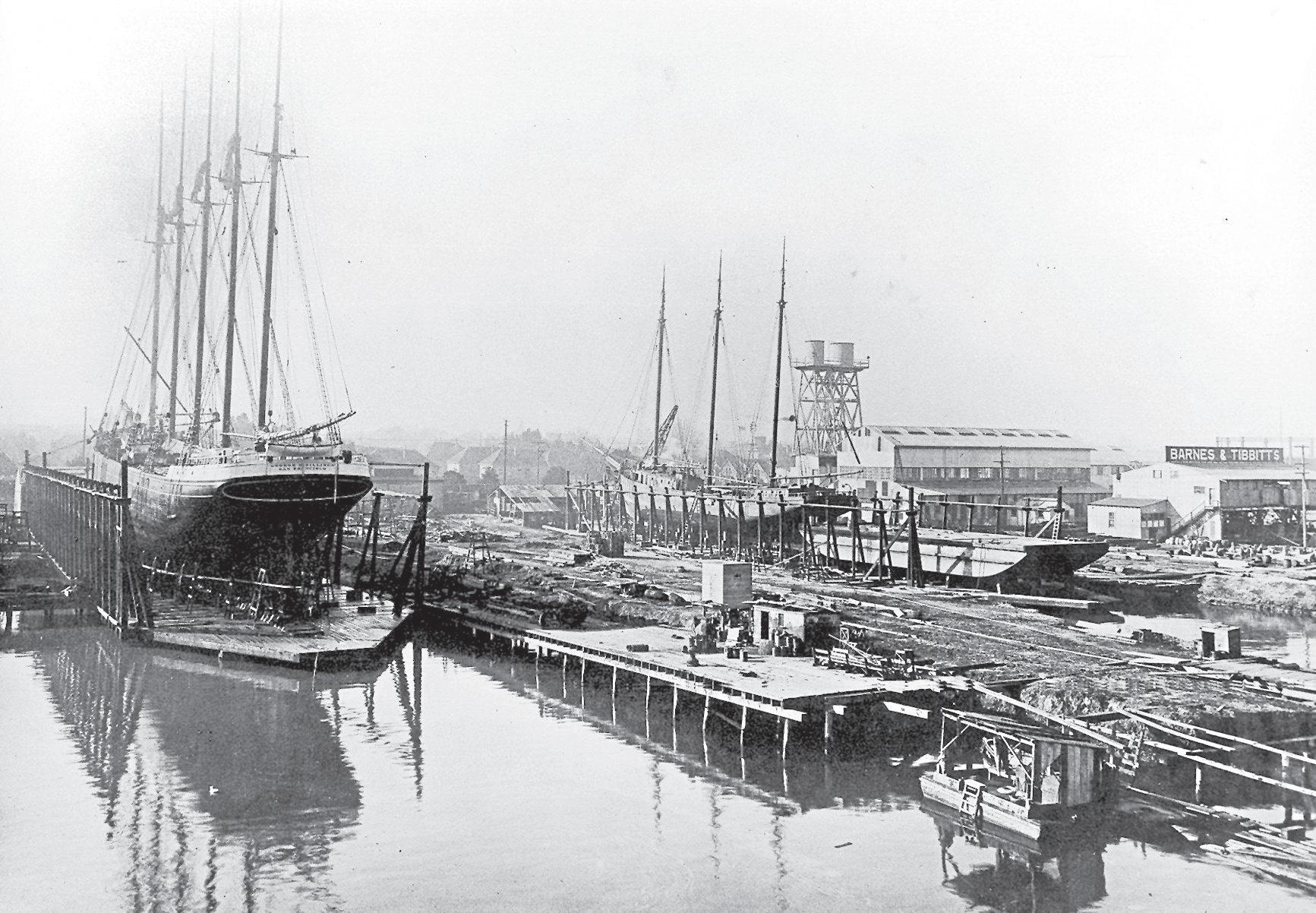

Above: Before the Posey Tube opened in 1928, thousands of people used the Webster Street drawbridge — seen here circa 1920 — between Oakland and Alameda.

The ‘manicured little island’ that had a rough-and-tumble beginning

BY JOHN METCALFE

Ah, Alameda — that suburban island with its waving palm trees, main street parades and beach with sun-kissed views of San Francisco. Is there any more pleasant place to traipse around than the “Island City”?

But it wasn’t always so. In place of doggo-filled beer gardens and kid-filled bistros, there once was stinking mud, noxious weeds and at one point, a pretty rough-and-tumble populace. People traveled by street cars called “Dinkeys,” and for a time, there was a risk of a sludgy Salton Sea and 32-lane highway obliterating the quality of life. Heck, Alameda wasn’t even an island at first — it was latched to Oakland before the largest dredging operation prior to the Panama Canal carved it loose.

“I think you can make the argument that Alameda was the first Bay Area suburb as early as the 1870s. There were upper-middle class professional people — lawyers and business people — who lived in Alameda and met everyday in downtown San Francisco by using

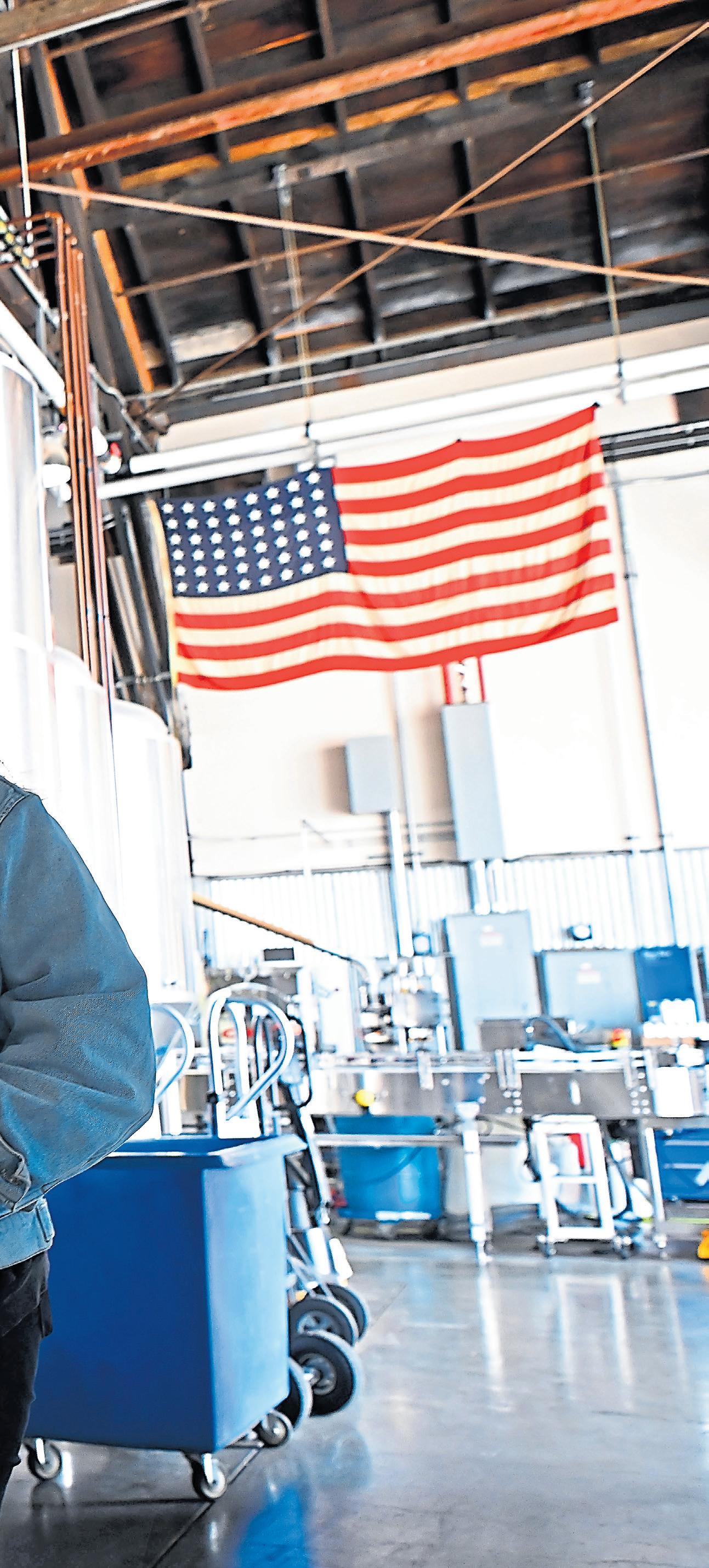

Mike Albrant, center, Hospitality & Merchandise Manager at St. George’s Spirits gives a tasting to patrons on the former Naval Air Station in Alameda March 2.

time. It started smelling bad, and people were throwing their trash in there,” says Evanosky. That wasn’t the last of the major construction on Alameda. Around the same time, seeing their land erode at a rate of 3 to 7 feet a year, residents toward the south began building bulkheads. Then in the 1920s, the area was filled in with 43 acres of new land to expand Neptune Beach, the so-called “Coney Island of the West.”

The amusement park opened in 1917 and drew throngs from San Francisco and beyond. Located by today’s Crab Cove, it was one of several play paradises operating around the Bay. There was also the sprawling Sutro Baths and Playland-at-theBeach on the Pacific Coast and Idora Park in Oakland with its mountain slide, Japanese garden and ostrich farm. Oakland also had the Piedmont Baths, a swimming complex with 20 types of baths that drew water from Lake Merritt, filtered to remove unpleasant gases.

Fun-seekers arrived at Neptune Beach via ferries or trains running from the Alameda Mole, a Southern Pacific Railroad spur on the island’s west side that served electric commuter trains called Big Reds. For a time, Alameda was something of a public-transit utopia, complete with small street cars called Dinkeys. Residents were allowed to choo-choo all around the city free of charge, and a newspaper declared the island “enjoyed the best transportation facilities of any city west of the Mississippi River.”

For 10 cents admission, visitors to Neptune Beach could paddle in the largest outdoor swimming pool in the U.S., see movies like Buster Keaton’s “What! No Beer?” and watch Johnny Weissmuller, the Olympian star of “Tarzan the Ape Man,” break the world record for the 100-meter freestyle. There were mock aerial dogfights, rides from the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition and roller coasters called the Lindy Loop and the Whoopee, responsible for at least two deaths. Frights and hazards were a given. “The Whoopee jerked its petrified customers around to the point of whiplash,” notes the Alameda Museum on an exhibit placard. “The Merry Mix-Up

got people dizzy in the big swimming pool. It was deemed so dangerous by local authorities that it was relocated from the pool onto dry ground. The Flying Airplanes gave riders the illusion of flight, complete with nausea bags.”

The park took a one-two punch from the Great Depression and the opening of the Bay Bridge, which decimated ferry service, and the gates closed permanently in 1939. “It had a rather sad ending, because the family that owned it just overextended and defaulted on a bond measure,” says Evanosky. “They sold everything for a penny on the dollar.”

But there was more bad news for Alameda in the form of a man called John Reber, who was hell-bent on reshaping not just the island but all of the Bay.

Reber was an actor from Ohio who had met many politically well-connected people while working on community pageants across California. Though he didn’t seem to have much of an engineering background, he believed the Bay Area was “a geographic mistake” — particularly in its unpredictable access to fresh water. His solution was to build two massive earthen dams, one by today’s Richmond-San Rafael Bridge and another by the Bay Bridge, to trap river water and create the “greatest fishing hole in the world.”

The early 20th century was a fertile time for far-fetched infrastructure schemes. Atlantropa, a 1920s concept from German architect Herman Sörgel, would have dammed up the Mediterranean Sea to lower the water level by 600 feet and create new space for colonization. Construction commenced in the 1930s on the Cross Florida Barge Canal, a pseudo-Panama Canal cutting through the state, before

President Nixon put the final kibosh on the on-again, off-again project.

Water needs seemed to fuel these pipe dreams in drought-ridden California. In the 1950s, engineers envisioned a network of 400 gigantic fountains — nicknamed “The Big Squirt” — spitting high into the air, one to the other, to transport

BY KATE BRADSHAW

From public art installations and panoramic views to beachside strolls and birdwatching, the islands of the San Francisco Bay offer abundant joys to explore on foot. Here’s where to go.

BAIR ISLAND

This may feel like a breezy bayfront park tucked amid the marshes of Redwood City, but it’s actually an island. Or rather, it’s three islands — Inner, Middle and Outer Bair Island — with so much wildlife, you could fill a nature bingo board or 12 with the flora and fauna you’ll spot as you stroll this 3.4-mile route on Inner Bair Island. The trail is an out-and-back, no navi-

gation needed.

Inner Bair Island is part of the Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge and open to the public for hiking and other recreation. Some parts of the island can be reached by kayak, but you needn’t get your feet wet for this trail. It’s hard to imagine, but in the early 1900s, these islands were used for agriculture — not particularly successfully, though.

By midcentury, they were used to create salt evaporation ponds. This marshy area has been an ecological reserve since 1986.

Details: Open 7 a.m.-8 p.m. daily at 3 Uccelli Drive in Redwood City; fws.gov.

Panorama Park, which opened in May 2024, is a beautiful addition to Yerba Buena Island. Built atop a hillside with stunning Bay views, the park is home to a towering 69-foot-tall sculpture by Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto called “Point of Infinity” that acts as a giant sundial.

Meander down the landscaped hillside, and you’ll find a minimalist dog park with breathtaking views of Treasure Island.

A monument in Panorama Park commemorates the Port Chicago mutiny trial held on the island in 1944. Hundreds of servicemen refused to load munitions after a deadly explosion at the Port Chicago Naval facility on Suisun Bay killed more than 300 people, most of them Black, and injured nearly 400 others. Fifty of the servicemen were convicted of mutiny and sentenced to prison and hard labor — and exonerated in 2024.

BY JOHN METCALFE

If you’ve ever watched the 2023 movie “Oppenheimer,” there’s a scene where the titular physicist watches soldiers put bomb parts into trucks that then drive off into the horizon. Everyone knows what happened after that: The U.S. dropped the atomic bomb on Japan, leading to the end of World War II and the advent of the nuclear age.

What isn’t shown is those bomb parts first headed to Mare Island, a ship-building facility in Vallejo in the northern San

Francisco Bay.

“These packages came into a small building. Nobody knew what was in them. There were armed Marines on all the rooftops around it, basically snipers,” says Kent Fortner, president of the Mare Island Historic Park Foundation. “If you talk about the seminal event of the world in the last century, it might be the dropping of the atomic bomb. All that came to pass through right here on the island.”

This gripping nugget is among hundreds from Mare Island — despite its name, it’s technically a peninsula — whose

Mare Island Brewing’s food and beverage director Sharyl Lytle samples the wares near the 30-barrel fermentation tanks at the brewery’s Coal Shed Brewery and Taproom, which opened in 2017 on Mare Island.

JOSE CARLOS FAJARDO/STAFF

secrecy-shrouded past dates from the Civil War to its decommissioning in the 1990s. More than 500 numbered vessels were built here, and a thousand-plus more overhauled. The first commander was Admiral David Farragut of “damn the torpedoes, full steam ahead!” fame. Mare Island supported the Navy during both world wars and helped spy efforts during the Cold War by tapping Soviet cables from nuclear submarines. Even if you don’t know about

its past, it’s a fascinating place to visit. Almost 3.5 miles long, it has a mix of residential blocks with neocolonial homes and an industrial waterfront on the Napa River with functioning dry docks and “Star Wars”-scale cranes. There are scenic hiking areas and a lovely park, featuring concrete bomb shelters and a nuclear Polaris missile aimed at the sky. Then there are the commercial enterprises that moved in once the Navy left — art studios, tasting rooms

for wines and whiskey and a brewery pouring Navy-themed suds in an old coal shed.

On a recent afternoon, Lew Halloran is leading a tour of the same place he was stationed as a Navy man from 1989 to 1993. Mare Island’s historic foundation offers these public tours as part of its educational programming, along with a speaker series with topics such as the advent of kamikaze pilots and 2,000 years of cryptography.

“The purpose of Mare Island

was to maintain ships and to build ships. That’s why she’s here. And by the time we came up to closure, this yard could do anything,” says Halloran. He gestures around: There was a shop for bending and X-raying pipes and a foundry to cast propellers. A sawmill and a place to calibrate periscopes. A coffee roaster and grinder that did nothing during World War II but make 5-pound coffee cans for caffeine-deprived sailors. A paint factory and laboratory

where research against barnacles supposedly led to superglue. There were craftsmen who could fix your wooden leg.

“They could tear apart a boiler and put it together again from scratch,” says Halloran.

Nearby, a siren suddenly blares. Foghorn blasts and electronic shrieks around the base give the uncanny impression the Navy never left.

“I don’t know what that means,” he frowns. “Nobody’s running, so I think we’re good.”

Mare Island’s bellicose history goes back to its name. A Californio general lost his prized horse overboard in 1835 and later found it wandering the peninsula — thus “Isla de la Yegua” or Island of the Mare. During the Gold Rush, the U.S. government carved out land here to protect the San Francisco harbor and its booming economic activity. The first ship built was the USS Saginaw in 1859, a paddle-wheel gunboat used in the Civil War to guard against Confederate marauders.

Admiral Farragut assumed control in these early years with the intention of nurturing a world-class shipyard on the lines of what existed on the East Coast. Things began gaining momentum in the early 1900s, when the yard teamed up with Union Iron Works in San Francisco for armored ships, built ahead of schedule and under cost. Churning out destroyer escorts and submarine chasers elevated operations during World War I, because German subs were sinking convoys left and right.

World War II saw employment surge through the roof. Ultimately, some 45,000 people worked here, a quarter of them women.

“They were building submarines, all kinds of destroyers, and interestingly enough, the biggest need in terms of number

Mare Island tours: The Mare Island Historic Park Foundation offers tours by reservation during the first and third weeks of each month at 10 a.m. Thursdays and Saturdays and 2 p.m. Sundays. Tours are $20 per person (children are free) and begin at St. Peter’s Chapel, 1181 Walnut Ave. in Vallejo. Find details and book a tour at www.mihpf.org/tours.

Mare Island Art Studios: Open from noon to 4 p.m. on Sundays at 110 Pintado St.; https:// mareislandartstudios.com/.

Vino Godfather Winery: Open noon to 7 p.m. Thursday-Sunday at 1005 Walnut Ave.; www. vinogodfather.com/.

Redwood Empire Whiskey: This distillery tasting room on Mare Island is scheduled to reopen this spring; https:// redwoodempirewhiskey.com/.

Mare Island Brewing Co.: The Coal Shed Brewery taproom opens at 11:30 a.m. WednesdaySaturday at 850 Nimitz Ave.; www.mareislandbrewingco.com.

of vessels was landing crafts,” says Dennis Kelly, a foundation board member who refilled nuclear submarine reactors here during the 1970s. “Mare Island built so many tank landing crafts that if you laid them out in row, it’d stretch for six miles.” (These vehicles’ parts were shipped by train from Colorado, and what determined their ultimate size was the size of a single railroad tunnel under the Continental Divide.)

Mare Island was one of only two public shipyards in America that built nuclear submarines during the Cold War. It hosted

an “ocean-and-engineering program” that actually was a highly classified mission called “Ivy Bells,” sunk deep in the Soviet Sea of Okhotsk.

“We had telephone taps that were 20 feet long and would take them by submarine with saturation divers to tap into undersea lines and record conversations,” Kelly says. The tapes were swapped at Mare Island, then presumably flown in handcuffed briefcases back to D.C. for analysis. “That program was credited for helping end the Cold War, because we were very hawkish about what the Soviets were up to and found out they were actually more worried about us attacking them.”

The base was decommissioned in 1996 when a federal cost-benefit analysis of military bases found it lacking for the post-Cold War age. There

ARIC CRABB/STAFF

Top: A thenrestricted photo from 1945 shows a warship docking at

was a three-day “conversion” ceremony — the term “closure” seemed too grim — with river patrol boats from the Vietnam era and Marines jumping out of a helicopter. But there’s still plenty to explore today, and you don’t even need a top-secret pass.

St. Peter’s Chapel is the oldest standing Navy chapel in the United States, dedicated in 1901. It’s cozy, but the vaulted wood ceilings and Tiffany stainedglass windows lend a grand and

Gothic air. Plaques pay tribute to every conflict the Navy’s been in, from the Revolutionary War to Vietnam, and are made from metal salvaged from notable ships — including the USS Hartford, which Farragut steered through withering fire from Confederate cannons in 1864’s Battle of Mobile Bay (“damn the torpedoes!”). Tour the chapel on the second and fourth Sunday of the month or take a tour in which your guide may noodle on the old church organ.

Nature lovers might enjoy the Mare Island San Pablo Bay Hiking Trail, an easy walk near the water that should get you thirsty for a beer later. And budding botanists will delight in identifying the individually tagged trees all around Mare Island that hail from far corners of the world: Canary Island Pine, Chinese Pistache, Brazilian Pepper, Chilean Soap Tree.

Many of these owe their origins to Commodore James Alden in the late 1800s. “He told

ship captains, ‘Wherever you go, pick saplings and send them back, and I’ll plant them here,” says Halloran. “As far as trees go, this island is supposedly the most biodiverse in the country.”

The alien species have led to at least one close call, when a yard worker was clearing around an Australian bunya-bunya in the 1960s. “As I raked around the tree, I heard several loud noises coming from above me,” he recalls on a University of California garden-

ing blog. “I looked up and at the same time, a cone hit the ground about 10 feet away from me. I took the cone home with me and weighed it. It weighed 20 pounds.”

The Mare Island Art Studios is a quirky collective of painters and sculptors located on the banks of the Napa River. It’s open to the public every Sunday afternoon, when visitors might meet a resident artist such as Jean Cherie. She’s working to decorate the ferry dock at the old base with a 10-foot bronze statue of Wendy the Welder, the lesser-known cousin of Rosie the Riveter.

“Somebody said there’s not really anything that represents the women who worked here during World War II. I said, ‘Yeah, I can fix that,’” says Cherie.

As you might imagine for a place filled with sailors, the drinking culture on Mare

Mare Island’s Alden Park includes lush grass, a charming gazebo and more than a century of naval weaponry, including cannons, torpedoes and a Polaris missile.

ARIC CRABB/STAFF

Island was robust in its day. Submariners who earned their “dolphins” — their hard-won insignia — couldn’t just pin them on. They had to first drop them into a pint glass filled with every liquor imaginable and drink it all the way down. There was a bar named Chesty’s in the former Marine Corps barracks. It was named after Lewis “Chesty” Puller, a famously hardass Marine given to wisdom like, “We’re surrounded. That simplifies the problem.” (By firing in every direction.)

This drinking tradition lives on at the Vino Godfather Winery, which serves flights and charcuterie, and the new tasting room of Redwood Empire Whiskey, with its Sonoma-style bourbon and Southern menu designed by a real Kentucky colonel. Then there’s the Mare Island Brewing Co.’s Coal Shed Brewery, run by Ryan Gibbons

and Kent Fortner — yes, the president of the Mare Island Historic Park Foundation.

The taproom is sheltered in a hulking shed formerly used to store coal for ships, including Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet, the battleships that circled the globe. When an electrician wired up the brewery, Fortner pointed him to a panel so big, it looked like its own room.

“He’s like, ‘Oh my God — there’s enough power here to power a battleship’ and comes to the realization that we had enough electricity to run a small city off these things, because that’s what these ships were.”

The brewing company pays tribute to the local history with beers such as Chesty’s Barrel Aged Stout and the porter General Order No. 99, aged in a bomb shelter and named for the Navy Prohibition directive banishing alcohol from bases. For grub, there’s a food truck called the Pie Wagon serving hand pies, crab cakes and fries. It is named after a World War II-era, luggage-toting type of vehicle that delivered food to nearly 50,000 people on base.

“Mare Island is the most unique and awesome branding opportunity I’ve come across,” Fortner says. “It’s a story that desperately needs to be told. It’s one of most important places on the West Coast in terms of naval history, and it impacted the world in so many ways.”

That includes the small building used to store Oppenheimer’s atomic-bomb parts and which is no longer standing.

“There’s a taco truck that sits there where I eat about once a week,” says Fortner. “We call it the atomic taco truck.”

BY JASON MASTRODONATO

California was never a hotbed of Civil War action, but the Golden State — and the Bay Area in particular — played a major role. The riches of the Gold Rush didn’t just line the pockets of lucky miners; they fueled the Union war effort.

“We enlisted 17,000 Californians, but they mostly fought in the West, marching across the desert into Arizona and New Mexico,” says Concord native Glenna Matthews, a former Cal and Stanford history professor and author of “Golden State in the Civil War.” “Mostly what California did for the Union was send money.”

And, she says, historical sites from that era — forts, armories and even a duel site — dot the region, popping up in parks, on the waterfront and on its islands.

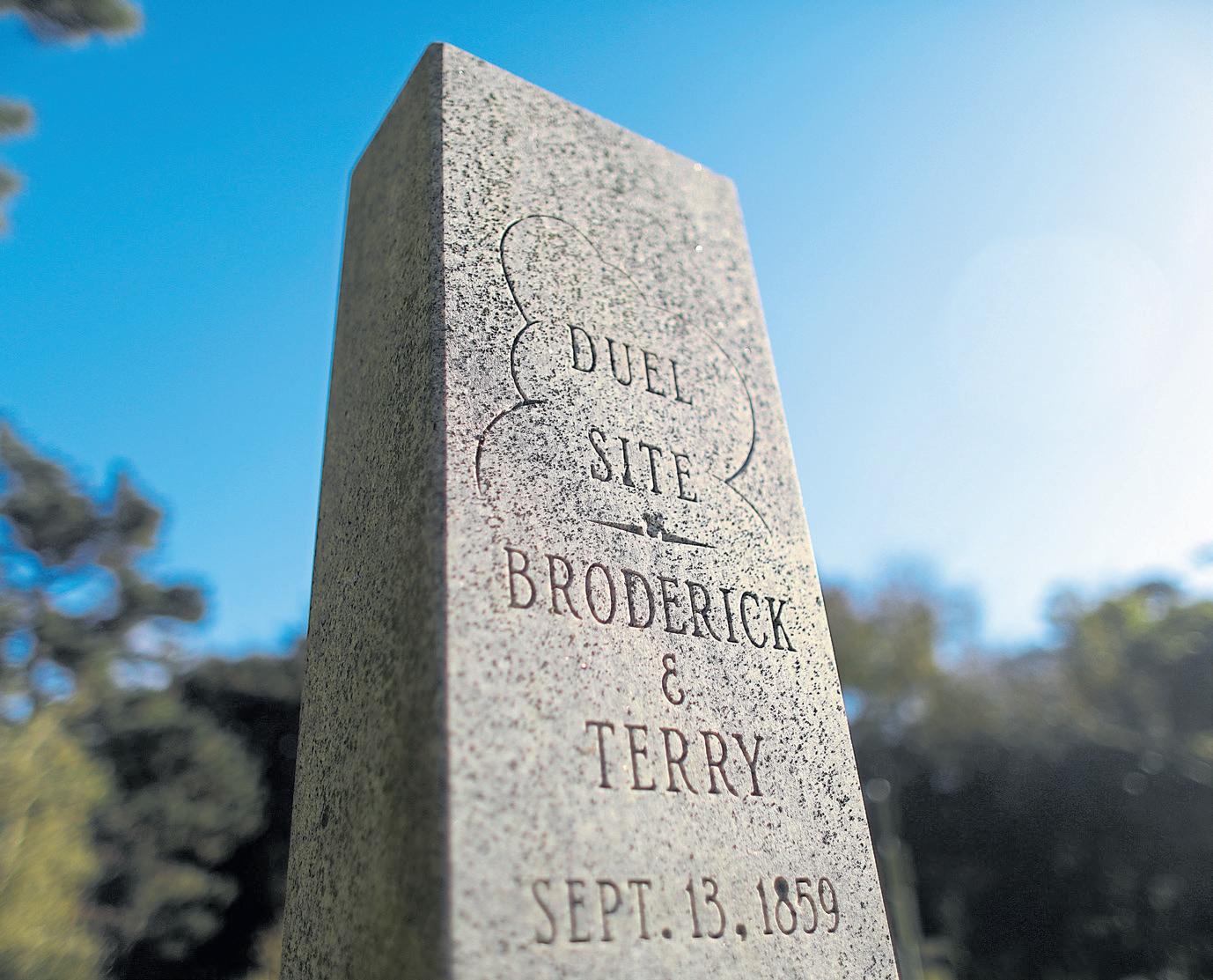

BRODERICK-TERRY DUEL SITE

In a small, quiet Daly City park just south of San Francisco’s Lake Merced, two century-old granite shafts sit 10 paces apart, with the name Broderick carved into one and Terry into the other, commemorating the last great American duel.

In 1859, U.S. senator David Broderick and California Supreme Court chief justice

Top right: Actors portraying Union Army soldiers steal a peek at the battlefield during a Living History Days event on Angel Island.

SHERRY LAVARS/ STAFF ARCHIVES

Bottom right: This marker in a Daly City park commemorates the site of a duel fought by U.S. senator David Broderick and California Supreme Court chief justice David Terry in 1859.

ARIC CRABB/STAFF

David Terry — former friends on opposite sides of the slavery argument — fired their pistols in a battle that cost Broderick his life but proved a significant tipping point to push California away from the Confederacy. Terry, who had a history of violence and once stabbed a man to death, denounced Broderick publicly for his anti-slavery stance. Broderick challenged him to a duel.

According to the National Parks Service, Broderick’s gun misfired into the dirt just before the one-two-three count. Terry fired straight into Broderick’s chest. He died three days later, reportedly saying, “They killed me because I am opposed to the extension of slavery and a corrupt administration.”

Terry resigned as chief justice and joined the Confederacy. But Broderick became a martyr, and his death supplied a jolt of energy to California’s anti-slavery movement.

Details: 1100 Lake Merced Blvd. in Daly City; nps.gov

THOMAS STARR KING STATUE

After Broderick’s death, Abraham Lincoln sent a friend, politician Edward Baker from Illinois, to California to give the

A ferry boat ride to Angel Island leads to many rewarding discoveries

BY JASON MASTRODONATO

As day trips go, this one is spectacular. You arrive by water with views of the Golden Gate Bridge and the entire Bay. There’s hiking, biking and barbecuing. And it all starts with one charismatic sea captain.

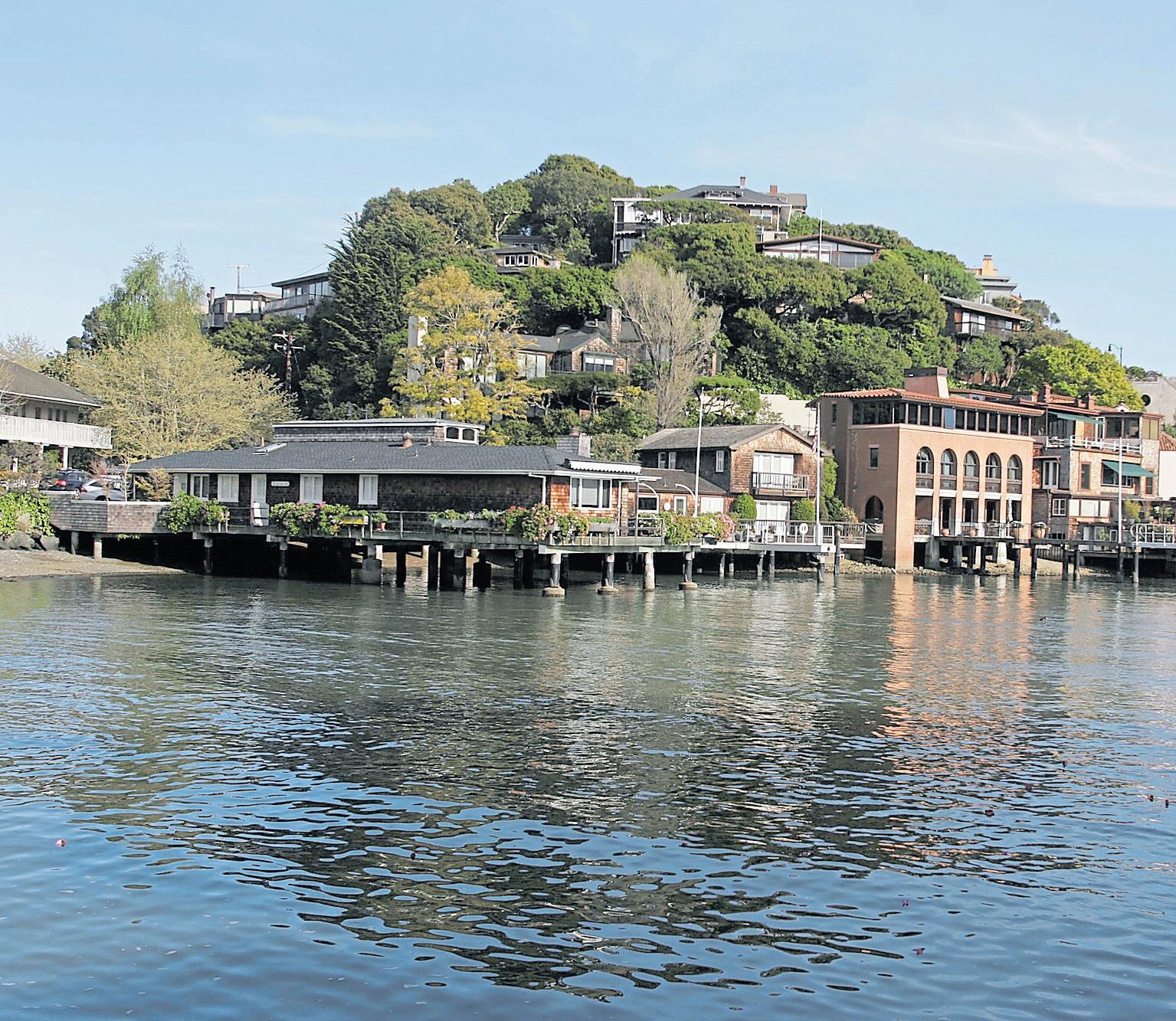

Captain Maggie McDonogh is the fourth-generation owner and operator of Angel Island Tiburon Ferry, which takes hikers, cyclists and picnickers from Tiburon’s cozy, historic waterfront to Angel Island’s Ayala Cove.

McDonogh has made it her mission to help locals and tourists alike discover the beauty of a picturesque island that is 33 times bigger than its famous sister, Alcatraz — with less than two percent of its crowds.

“It’s one of the best kept secrets in California,” says McDonogh. “It’s an underutilized park in every way.”

Angel Island wasn’t always open to the public, of course. For a century — from the Civil War

The soft sand at Angel Island’s Ayala Cove beach is popular with families.

LAURA A. ODA/STAFF ARCHIVES

through the Cold War — its strategic location made it a military outpost, a defender of the Golden Gate. The army built a base there, Camp Reynolds, in 1863 to help defend against Confederate sympathizers. In the late 1800s, the island housed quarantined soldiers coming back from the Spanish-American War in the Philippines.

For three decades in the early part of the 20th century, it was used as a grueling detention center for immigrants (and some American citizens) hoping to gain entry into the U.S. And during the 1950s, Nike missiles were stored in underground rooms, with elevators ready to bring them to launch position.

The island’s military period came to a close in 1962, its missiles ruled obsolete and the Army base decommissioned. The island became a California state park the following year.

Today, it’s inhabited by fewer than 40 people, all state park employees, and occasional intrepid campers lucky enough to snag a reservation. Everyone else is a day tripper, and there are far fewer of them than you might expect. Some 20,000 visitors alight on the island each year, compared with the 1.2 to 1.6 million who dock at Alcatraz. There are no crowds here, no competition for astonishing views or trail space.

Angel Island Conservancy secre-

With 1.2 square miles of land, Angel Island State Park is the largest natural island in the San Francisco Bay and provides some amazing views.

COURTESY OF ANGEL ISLAND CONSERVANCY

a daily passenger ferry to shuttle folks to Angel Island once the island opened to the public. The 400-passenger ferry he designed in 1975 — The Angel Island — is still sailing today.

Jump aboard one of the McDonogh family’s four ferry boats, and you’ll find yourself sailing with all sorts of people, from kids on field trips to explore the island’s rich history to a mother and baby here for the fresh air, not the destination. You might share the ride with a senior cycling club, the Geezers on Wheels, perhaps, or the Old Spokes. Or campers toting backpacks. Or a piano.

McDonogh had an entire band on board for one memorable crossing. They rolled a piano onto her ferry, she says, then rolled it off the boat and up a hill to help set the vibe for a music-themed camping trip.

There have been impromptu weddings and family reunions, too.

“The other day,” she says, “I had a guest who said, ‘13 years ago, you ran a boat out so our family could see me proposing to my wife.’ Just to be a part of the community’s history, it’s stunning.”

Angel Island sits on the horizon across from the San Francisco Yacht Club boat docks in Tiburon.

KARL MONDON/ STAFF ARCHIVES

It’s never the same trip twice. The people vary — and so does the wildlife.

“You can see seagulls, cormorants, pelicans, puffins, orcas, elephant seals, sea lions, harbor seals, porpoises,” McDonogh says. “I had a bottlenose dolphin who was in love with Angel Island in 2004. Every time I left the dock, she waited for me, and we went across.”

You, too, can board the ferry, taste the sea breeze and take it all in — and 15 minutes later be dockside in Ayala Cove.

The island typically sees two types of visitors — history buffs

who ramble among the ruins and exhibits and hikers eager to enjoy the trails, viewpoints and picnic spots as they explore the 1.2-square-mile landscape. The conservancy’s apps split it up nicely, depending on your interests. The captain and the park’s rangers are happy to provide itinerary suggestions as well. Fill your water bottle, grab a map (or download the app) and make a plan. If you’re here to hang out and barbecue, the warmth of Ayala Cove is the perfect place. Spanish ships once anchored here in the shelter of the cove. Today, you’ll

find sailboats anchored there, not galleons. There are rolling lawns, picnic tables and a beach that’s popular with families. (Quarry Beach, on the other side of the island, is also popular.)

If you have a bike — McDonogh recommends bringing an E-bike; her staff will help you load it on the ferry — hit the paved Perimeter Trail for a 6-mile journey up and around the scenic island. There are some steep parts, within a total elevation gain of 528 feet, but there are also plenty of places to take a break, explore the scenery and learn some history.

For the park’s richest history tour, a 1-mile walk takes you to Immigration Station, where an incredible museum will teach you about the 300,000 people once detained here.

Walk a mile in the other direction, and you’ll reach Camp Reynolds, a must-see.

“Camp Reynolds is a great deal

RAY CHAVEZ/STAFF

Right: For

more than just Civil War history,” says conservancy director Frances Bellows. “Its history spanned from the 1860s through 1940s.”

JENNIFER WAICUKAUSKI

In addition to hosting overnight Civil War field trips for fourth and fifth grade classes, rangers periodically hold living history events that are open to the public.

“We do one that’s a timeline with soldiers and families dressed from the Civil War to Spanish American War, World War I and II. (They) share the history of what life was like at Angel Island at the period,” Bellows says. “It’s geared to every age.”

And if you’re looking for out-

doorsy exercise, the entire island awaits. For an adventurous climb, try the Mount Livermore trail — named for conservationist Caroline Sealy Livermore. It’s a steep climb, a 5-mile loop that takes you up almost 800 feet, but the reward is a stunning view of the entire Bay and picnic spots for a memorable lunch.

The North Ridge Trail and the Sunset Trails provide selfguided nature walks for folks looking for a challenging hike. If you’re doing one of the longer hikes, arrive early and plan your time, so you’re back on the dock before the last ferry leaves.

Diehards looking to maximize their Angel Island experience may want to check out the camping options. The island offers nine reservation-only backpacking camps, three with views of San Francisco sunsets over the Bay.

However your visit comes to an end, Captain Maggie will be waiting to take you home — and the next generation is waiting to take the tiller. McDonogh’s 23-year-old daughter, Becky, is carrying on the family tradition as a deckhand and soon-to-be captain.

“I’m honored,” McDonogh says.

Details: The Angel Island Tiburon Ferry ($6-$18 round trip) begins its runs at 10 a.m. and returns as late as 5:20 p.m. in the summer months; angelislandferry. com. The San Francisco Ferry Terminal sends boats ($16-$31 round trip) to Angel Island beginning at 9:25 a.m. and returns as late as 5 p.m.; goldengate. org. Learn more about Angel Island at angelisland.org.

Island oysters ($22 for six, $40 for a dozen) and crispy Dungeness tacos ($28) many places but here. And though the burrata salad ($21) is a mainstay, the seasons dictate its other ingredients, sometimes beets or pears and sometimes (personal fave) citrus and chimichurri.

Vegetarian and vegan options abound, including avocado and ricotta-topped pizzas and roasted cauliflower steaks as well as pescatarian fare (lobster slider, anyone?) and dishes for the omnivores (hello, hanger steaks). As for that gorgeous view, you can take it all in from the deck — with heat lamps for chilly days — or the airy, Scandi interior.

Details: Opens at 11 a.m. weekdays and 9 a.m. weekends at 9 Main St. in Tiburon; www.malibu-farm.com

This waterside hot spot is tucked away in Redwood City’s Westpoint Harbor, a marina for local boaters that sports an intriguing history.

Starting in the 19th century, this corner of San Francisco Bay was home to lumber shipyards, concrete manufacturing and salt-farming facilities. Local boater and entrepreneur Mark Sanders saw an opportunity in the 1980s, but it took decades to bring his dream to fruition. The marina opened in 2008 — and a destination restaurant just last year.

Redwood City’s appealing climate and the placid bay waters provide an appealing spot for Hurrica’s alfresco diner designed by noted chef Parke

Dine al fresco at Tiburon’s Malibu Farm and the views include Angel Island, the city skyline and Tiburon’s docks.

DOUGLAS ZIMMERMAN/STAFF ARCHIVES

Ulrich, who has built the menu around live-fire cooking. Grab a table and order a hearth-roasted Liberty duck salad ($21), smoky slow-roasted pork chop ($45) or beer-battered fish and chips ($22) with remoulade.

Indoors, diners get a peek outdoors — plus what you might call an ocean view, courtesy of the museum-caliber jellyfish aquarium.

Details: Open from 5 to 9:30 p.m. daily for dinner and 11 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. for lunch Wednesday-Sunday at Westpoint Harbor, 150 Northpoint Court, Redwood City; www.hurrica.restaurant.

Treasure Island

Baked-to-order mega snickerdoodles with some of the best waterfront views of the Bay, minus the crowds? This indoor-outdoor restaurant built from shipping containers is decked out in vibrant murals.

Add lawn games, succulents in abundance and delicious burgers, and you have a complete package for a small island getaway, a secret Bay Area life hack and instant escape from rush hour.

The seasonal menu varies, but the Island Double-Decker Cheeseburger ($18), Fish and Chips ($19) with curry tartar and vegan Beyond Burger ($16) with caramelized onion and

chipotle crema offer creative flourishes on the classics. And the Snickerdoodle ($7) is enormous.

There’s live music Friday-Sunday from noon to 3 p.m. And if you want to make a day of it, the petite Treasure Island Ferry zips over to the San Francisco Ferry Building in a matter of minutes.

Details: Open from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Wednesday-Sunday at 699 Avenue

SHARP PARK TAPROOM Pacifica

OK, technically this is a “coming soon” venture — but it should be very soon. After two years of fundraising, planning and prepping, the Sharp Park Taproom is set to open this

astic neighborhood crowd. On a recent Thursday, the gathering included Pacifica resident Paul Zadin, who says he’s planning to be the first in line when the taproom opens. “Beer,” he says, “makes everything happy.”

Details: 100 Santa Rosa Ave., Pacifica; keep tabs on the taproom progress at instagram.com/sharpparktaproom/.

San Francisco

Good thing the signature Waterfront Cioppino ($45) arrives piping hot at the table — and stays that way for a while. You’re going to be setting down the soup spoon and seafood fork every couple of bites to soak up the spectacular San Francisco Bay views. The scene outside the expansive windows at this white-tablecloth Pier 7 restaurant encompasses the Bay Bridge, two riverboats (the Klamath and the San Francisco Belle) and the Ferry Building.

To maximize your enjoyment of the day’s colors, reserve a view table — inside or outside — an hour before sunset to order cocktails and appetizers and take in the azure blue water and skies, the gulls swooping down and boats slipping by.

spring in its new digs near the Pacifica Pier. The brain child of co-owner Kris Englund and her partner Alex, the taproom will offer brews from across Northern California and bar bites, including housemade dips and paninis.

While they await final permits, the couple has been hosting popups, including a weekly pop-up with Shmash’d Burgers, whose burgers ($11) draw an enthusi-

Soon the bay will turn slate blue, and the sun’s setting rays will glint off the glass on buildings across the Bay. As night falls, the lights of the Bay Bridge and Embarcadero buildings create a sparkling tableau on the shiny obsidian waters.

By then, it will be time to order dessert, maybe a seasonal fruit crisp or the Valrhona chocolate-walnut brownie, each topped with vanilla bean ice cream ($10 each).

Details: Open from noon to 8 p.m. Wednesday-Sunday at Pier 7, the Embarcadero, San Francisco, with $20 valet parking onsite; www.waterfrontsf. com.

BY JASON

MASTRODONATO

ILLUSTRATION BY ALDO CRUSHER

PHOTOS BY RAY CHAVEZ

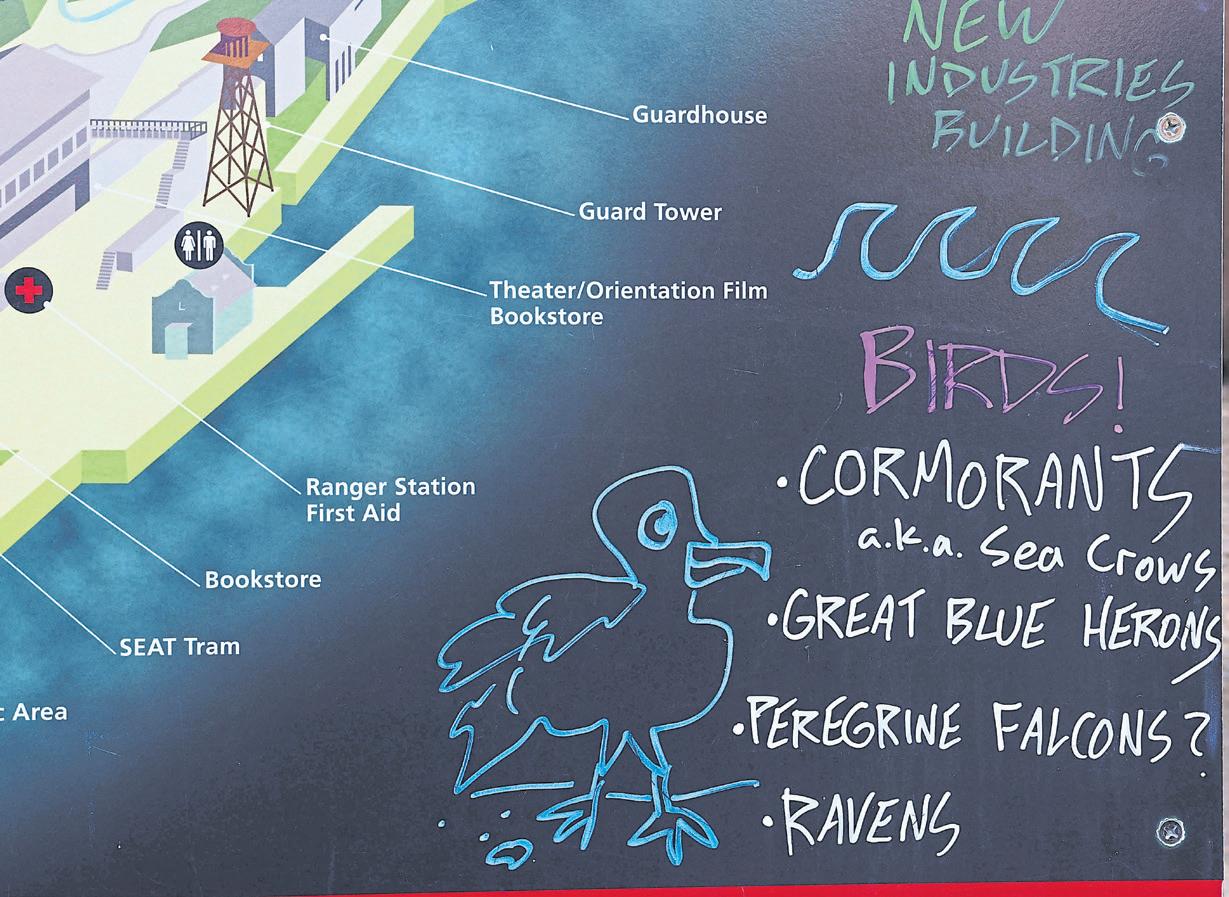

At the rocky edge of Alcatraz, a Brandt’s cormorant is committing a crime.

A cormorant neighbor just returned from a patch of nearby grass, where it plucked a mouthful of greens and waddled back to its mate to help build their nest. But the happy couple is about to make a mistake.

They turn their attention elsewhere, leaving their pile of vegetation unprotected just for a moment, and a crafty avian miscreant spots an opportunity.

Thief!

“It’s like watching a soap opera,” says Julie Thayer, a senior scientist at the Farallon Institute who has studied the birds of Alcatraz for almost 30 years.

Standing by the railing on the western edge of the island with the old cellhouse lurking on the hill behind you, it’s easy

RAY CHAVEZ/STAFF

marine life, there’s an abundance of nearby food for birds that feast on ocean creatures.

The result is magnificent, with cormorant and gull colonies spread out over the island, as if it were theirs alone. Snowy egrets and black-crowned night herons nest more discreetly in the bushes. Geese are everywhere. Sparrows and hummingbirds can be found, too. Ravens, of course. And until recently, there were a couple of peregrine falcons nesting on the island, but as of March, park rangers had gone months without spotting them, a particular concern, given the recent bird flu outbreak.

The National Parks Service, with help from scientists like those at the Farallon Institute, has been carefully protecting the island to ensure it remains a flourishing location for birds.

Imagine how many birds were there in the early 1800s, when Spanish explorers named the island after alcatraces or seabirds. Military takeover in the 1850s pushed the birds out, and for the next century, cannon fire and military activity made it an unwelcoming place for birds. Not even the famous “Birdman” prisoner, Robert Stroud, was allowed to have birds on the island.

The prisoners, however, were allowed to help tend the gardens and did such a good job introducing resilient plants that many continued to flourish years after the prison closed in 1963. Today, volunteers through the Alcatraz Historic Gardens Project keep the gardens blooming.

“It’s poignant to think about,” says local naturalist John Muir Laws. “Here you are in lockup for the rest of your life, but what

For birders, Alcatraz is an unusual environment. Seabirds often breed on land that’s not accessible to humans to observe. But there are no land predators on this island, so the birds don’t have to worry about exposing their nests.

“If you look at the spacing of the nests, they’re all about two neck lengths away,” he said. “So if you lean over, you won’t be able to peck or steal stuff from your neighbor.”

That’s a general rule of bird behavior on the island: lose focus, lose your nest. Or your chicks.

Ravens and, since 2019, peregrine falcons are waiting for unprotected nest eggs or for baby gull chicks to hatch, as they become easy prey.

The gulls don’t seem too concerned; they’ve nested everywhere on the island, with almost 1,000 pairs spotted there last year. From the old officers’

quarters to the warden’s house near the parade grounds, the Western gull has never looked more proud to make a home.

These birds can live to be as old as 30, though most live between 15 and 18 years.

Lucky birders might also catch a glimpse of the great blue herons. There are only a few, and they can be found in the eucalyptus tree above the Alcatraz rose garden.

It may require binoculars, but the pigeon guillemots can be spotted nesting in pipes and nest boxes near the shores. The black birds blend in with the darkness of their cavernous homes, but their bright red feet and bright red throats are unmistakable. Sometimes, you’ll see them right when you get off the ferry.

It takes some effort, but chasing the birds at Alcatraz can reward you with cheery entertainment.

At “The Rock,” it’s the birds’ world — we’re just visiting it.

“Whenever I’m over there, I think of being incarcerated on that island,” Muir Laws says.

“You may never fly again, but I wonder if the inmates looked out at the birds, if that could bring them comfort and hope.

“The birds can go in and out. And they chose to come there.”

Details: Take the ferry to Alcatraz ($48 for adults, $29 for children) as early as 8:20 a.m. returning as late as 6:35 p.m. through November; cityexperiences.com. See the “Birds of a Changing Climate” exhibit in the island’s New Industries Building, open from 3 p.m. to 4:45 p.m. on Tuesdays and Thursday-Saturday and other times depending on staff availability; nps.gov.

BY JIM HARRINGTON

Hollywood has long embraced the Bay Area’s many charms, filling countless films with scenes of the Golden Gate Bridge, cityscapes and rolling hills. The islands of San Francisco Bay have gotten their share, too, of close-ups over the decades, appearing in box office blockbusters, Oscar-nominated films and everything in between.

Here’s a look at just a few of our favorite films that were shot, at least in part, on those islands.

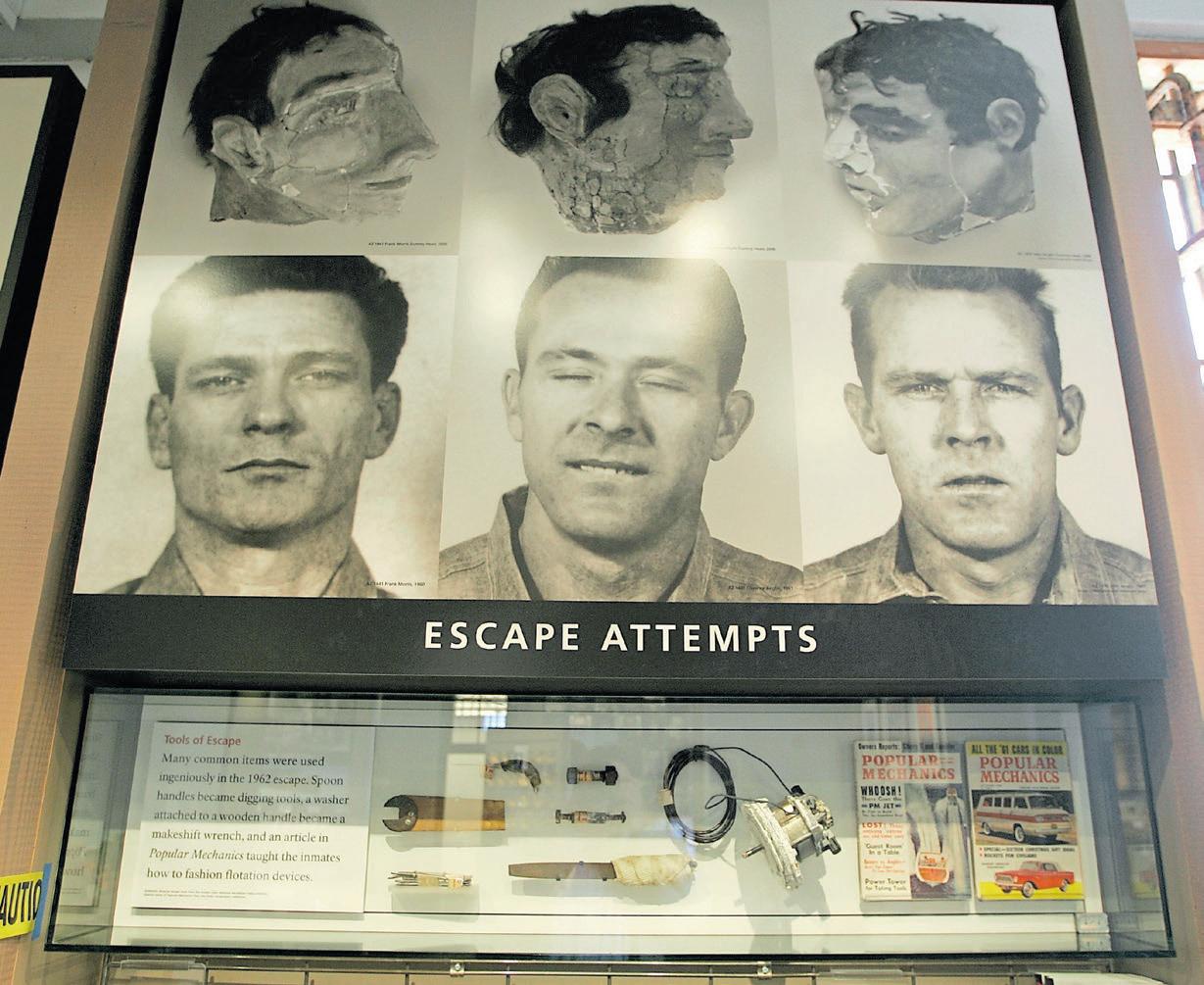

“ESCAPE FROM ALCATRAZ” 1979

Directed by Don Siegel, this iconic film is based on John Campbell Bruce’s 1963 account of the infamous Alcatraz prison escape in 1962. The movie stars the Bay Area’s own Clint Eastwood as escape ringleader Frank Morris in a cast that also includes Fred Ward, Patrick McGoohan, Jack Thibeau, Larry Hankin and another Bay Area screen legend, Danny Glover, in his film debut.

The film’s attention to historic details, from costumes to setting, landed it at No. 3 on the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy’s list of the top 10 movies made in the parks. (“Vertigo” took the top

A cellhouse museum exhibit, above, depicts the 1962 prison escape made famous in the movie “Escape from Alcatraz.”

evil general (Harris) and a rogue band of Marines who have taken tourists and security guards hostage on Alcatraz Island. The baddies are threatening to fire stolen rockets filled with VX gas at the city if their demands are not met. The $100 million ransom imposed by Harris’ character is intended to compensate, at least partly, the families of fallen men under his command.

Most of the film was shot on location at the prison, even though that meant having to dodge visitors who had ferried out to tour the National Park Service-governed site.

Interesting side note: The film inspired a 2003 remake in India under the title of “Qayamat: City Under Threat.”

Perhaps the most underappreciated offering in the Mike Myers oeuvre, this dark comedy serves as a nice showcase for the “SNL” funnyman’s many cinematic charms — which he later used to much greater financial reward in the “Shrek” and “Austin Powers” film franchises.

Myers plays a Beat poet living in, of course, San Francisco (which is apparently the only place Beat poets are allowed to live). He doesn’t have much luck with relationships, other than as fodder for his poetry. Then he meets Harriet (played by Nancy Travis), who is really great and all, except for the fact that she may well be an axe murderer.

The film is set entirely in San Francisco, but one of its most memorable scenes occurs during a visit to Alcatraz. It’s there that we meet one of the greatest tour guides of all time — John Johnson (aka, “Vicky”) — played to

weirdly menacing perfection by fellow “SNL” star Phil Hartman.

1954

Alcatraz isn’t the only Bay Area island to have received screen time over the years. Another cinematic favorite is Treasure Island, where productions ranging from “Hulk” (2003) to TV’s “Nash Bridges” (1996-2001) were filmed in the former naval station’s giant hangars.

One of our faves, however, is the 1954 juggernaut, “The Caine Mutiny.” This Edward Dmytryk-directed movie was based on Herman Wouk’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same name, which imagined a mutiny aboard a World War II minesweeper.

The movie’s great cast included Humphrey Bogart, who was nominated for a best actor Oscar for his portrayal of the erratic Lt. Commander Philip

Francis Queeg, as well as José Ferrer, Van Johnson, Robert Francis and Fred MacMurray. Sharing the screen with these famed actors is Treasure Island’s landmark Administration Building, which gets a small spotlight in this WWII Pacific Theater tale. (We like to think that the Treasure Island inclusion helped propel the film to score seven Academy Award nominations, including for best picture.)

1989

Built in 1937-38 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008, Treasure Island’s Administration Building also had a starring moment in the “Indiana Jones” series’ third chapter, which made $474 million worldwide.

The building was used in this Steven Spielberg-directed action-adventure flick as the Berlin Flughafen or airport,

the launching point for Jones (played by Harrison Ford) and his father (Sean Connery) to flee their pursuers via zeppelin, Grail diary in hand.

The impressive structure we see onscreen is draped in Nazi flags, which was historically appropriate for the scene — sure — but jarring when one realizes this was a working U.S. Navy base at the time of filming. (No worries. We’re told the flags were added in post production.)

Granted, it’s hard to take any action film seriously that shares a name with a can of tuna. Yet, this one was partially shot on Mare Island — and features John Cena — so we’re definitely including it here.

Directed by Travis Knight (the son of Nike bigwig Phil Knight), “Bumblebee” is the sixth in what surely feels like 987,477 installments in the film series inspired by Transformers toys.

This 2018 series offering, like all the ones that came before, was a hit at the box office, grossing nearly half a billion in ticket sales around the globe.

The storyline is opaque, even by Transformer standards.

The Autobots are evacuating from the planet Cybertron, when Decepticon’s attacking forces arrive, so Optimus Prime sends a scout, B-127, to Earth to set up an alternative base. That plan goes badly south. Just before B-127 collapses, the bot transfers itself to a yellow, 1967 Volkswagen Beetle — and about-to-be birthday present for young Charlie (played by Hailee Steinfeld).

It’s a lot. But the graphics are cool, and it’s fun to see all the Bay Area scenery.

on eight-hour expeditions that leave East Bay and San Francisco harbors.

We were invited to come ashore by Point Blue Conservation Science, the nonprofit organization that in partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been monitoring and conducting research on the islands’ seabirds. For 56 years, Point Blue scientists have braved wind, fog and isolation to build a rich wildlife database. But due to federal budget cutbacks, Point Blue biologists will no longer be monitoring the islands all year. As soon as September, they’ll be leaving their posts for the first time in nearly six decades. They wanted journalists to see the value of their work.

The journey out felt stomach-churning. Our day was beautiful and brightly scrubbed by the wind. But the going felt agonizingly slow, as the boat lurched into the wind and fierce swells pounded into every wave head on and sent bone-chilling spray gusting over the cabin.

Spring weather near the Farallones is deceptive. While the mainland begins to wake up from the dormant stage of winter, the temperature on the islands becomes cooler, according to the islands’ scientists. That’s because the trademark northwesterly winds of spring create rich upwelling zones within the California Current that rips through the lonesome rocks, sometimes reaching gusts up to 40 knots.

Finally, on the horizon, the Farallones emerged. Named for the Spanish farallón, meaning a rocky pillar jutting from the sea, the islands were called “the devil’s teeth” by sailors in the 1850s for their ragged profile and treacherous shores, the cause of many a shipwreck. The four small islands rise starkly from the sea: South Farallones, two islands divided by a narrow channel; Middle Farallon, a solitary rock three miles south; and North Farallones, four miles north. Southeast

Left: A derrick crane lifts a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service boat to bring seabird research assistant Heather Williams, top, and Farallon program biologist Amanda Spears, right, to land at the Farallon Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

Top: Jaime Jahncke, a director at Point Blue Conservation Science, takes a selfie with the gulls nesting at the Farallon house, where a few biologists live during the year.

the Farallons, where trees are in short supply, it loves crevices and burrows.

A blackboard featured a dauntingly long “to do” list: “Fix ceiling in laundry room.” “Collect water supplies.” “Switch out fire extinguishers.” “Review Seabird Report draft.” “Fix Leak on stanchion.” “Boat maintenance.”

After lunch, we hiked up rock cliffs, surrounded by a buzz of activity. A coronet of gulls circled overhead. Guillemots dived from the rocks, and cormorants flew in long black lines offshore.

The Pacific Ocean stretched westward 2,000 miles to Hawaii. On Southeast Farallon’s west end — the “weather side” — big swells thundered against the cliffs and rolling, great booming breakers raced up surge chan-

The Oceanic Society offers whale-watching expeditions to the Farallon Islands each year from April through mid-December. Led by a wildlife guide, the experience includes sightings of sea lions, sea birds and whales — more than 30 per trip last season — near these islands, which are 27 miles from the Golden Gate. Trips ($299) aboard the 60-foot Salty Lady depart at 8:30 a.m. on weekends from the San Francisco Marina Yacht Harbor, 3950 Scott St. in San Francisco. Find details at www.oceanicsociety.org/.

nels choked with logs.

In a cove, a cluster of tawny California sea lions glided through aquamarine water that

roiled with their antics.

We peered through a hidden bird blind at common murres, striking birds that are the ecological counterparts of Antarctic penguins. Similar to penguins, murres appear to be wearing tuxedos, with a coat of black feathers on their head, back and wings and a pale white belly and underwings. Clustered together, they preened and caressed. On bare rocks, pairs incubated one beautiful egg, shaped to roll in a circle so it won’t fall off a rocky ledge.

As we walked, we took care not to step on the auklet burrows that riddled the ground. A biologist fished an incubating auklet chick from its burrow. As fuzzy as a plush toy, it stared up at us, unflinchingly, with an

opalescent eye.

More than 400 species of birds have been recorded there — a stunning number for a refuge that measures only 211 acres in size. That’s largely because the Farallones get so many “vagrant” bird species — more than any other wildlife sanctuary in the U.S. When birds migrating over land encounter bad weather conditions, like headwinds or rain, they can stop traveling and rest. But songbirds flying over open ocean don’t have that option. So a wide variety of species — such as warblers, flycatchers, and buntings — make their way to the Farallones to recuperate, often confused and exhausted.

Soon, reluctantly, it was time to sail home.

As recently as 10,000 years ago, we could have hiked back. At the end of the last ice age, the coastline of the San Francisco Bay region was 35 miles seaward beyond its present position. That’s because great sheets of ice stored water — so sea level was about 300 feet lower than at present. The melting of the ice sheets caused sea level to rise, forming the Gulf of the Farallones and San Francisco Bay. Once-coastal hills are now the Farallon Islands.

The return trip was surprisingly serene, as the boat rolled and yawed pleasantly in quartering seas. We passed under the span of the Golden Gate Bridge and through its steely shadow, then glided into a slip at a Berkeley harbor and fastened the lines.

Giddy from the experience, I climbed off the boat, ears still ringing from the islands’ madhouse cacophony and muscles rocking from the ocean waves. But my heart was filled with gratitude for those who saved this special place, and I prayed for continued support.

When authors set their mysteries on an island, the suspense mounts and mounts

BY JACKIE BURRELL

Sure, tropical breezes and icy mai tais are lovely. But if you’re a writer of thrillers, mysteries or gothic romance, there are few settings more delightfully and deeply unsettling than an island. What could be more atmospheric than panicky characters marooned by storms, waves and geographic isolation?

No wonder Agatha Christie loved the setting so much. So did Dashiell Hammett, whose fictional Couffignal Island sits in San Francisco Bay. Jen Wheeler’s gothic romance unfolds in the Farallones. T. C. Boyle uses Anacapa and Santa Cruz islands for one of his books. And if the land of Dewey decimals is any guide, Catalina is a positive hotbed of stabby doings.

There’s just something about an island’s isolation that fires the imagination, says Wheeler, whose “The Light on Farallon Island” is set on those rugged rocks 27 miles off the coast. The Portland, Oregon, author found herself swept up in the lore and wonder of the craggy archipelago after reading Susan Casey’s “The Devil’s Teeth,” a nonfiction survival tale of surfer-scientists and great white sharks, and couldn’t shake the fascination.

“I’m a very solitary person, an introvert,” Wheeler says. “To me, the Farallones are really beautiful — teeming with wildlife and inhospitable to humans. You have to work hard to habitate the place. I like to imagine what kind of person would be drawn there.”

In Wheeler’s hands, the answer includes 19th-century lighthouse keepers, a teacher and the rough-and-tumble collectors who swept up murre eggs by the millions, devastating the bird population and making bank during the Gold Rush.

You can’t journey back in time to the Farallones, circa 1859, or set foot on those islands now, of course; it’s a marine sanctuary and off limits to the public. And you can’t outstrip the gunrunners of Couffignal Island either — except through the pages of a book.

So here’s just a sampling of mysteries and thrillers, divided by island inspiration.

(maybe)

Written in 1925, Hammett’s pre-Sam Spade story, “The Gutting of Couffignal,” stars a cynical gumshoe (of course)

assigned to guard wedding gifts at a swanky island colony, when the sound of gunfire and wild explosions suddenly fills the air. The islanders — wealthy retirees, vacationing aristocrats and a Russian princess among them — soon discover themselves marooned, the wooden bridge to the mainland in flames and boats cast adrift, with only our intrepid private eye on hand to save the day. (Spoiler: He does.)

It’s a rollicking read and a fast one, with action set on a

The communities of Corinthian Island, pictured, Belvedere and Tiburon are the likely setting of a Dashiell Hammett short story.

DOUGLAS ZIMMERMAN

fictional island on San Pablo Bay. We think the wedgeshaped island and exclusive colony are Belvedere and Corinthian Islands, a couple of bays over. Developed as a summer retreat for the wealthy in 1890, Belvedere is connected to Tiburon by two causeways now — but a century ago, a wooden drawbridge did the transportation honors, and the raising of that bridge each spring to release arks and sailboats into the open water

is still known today, Tiburon historians say, as Opening Day on the Bay.

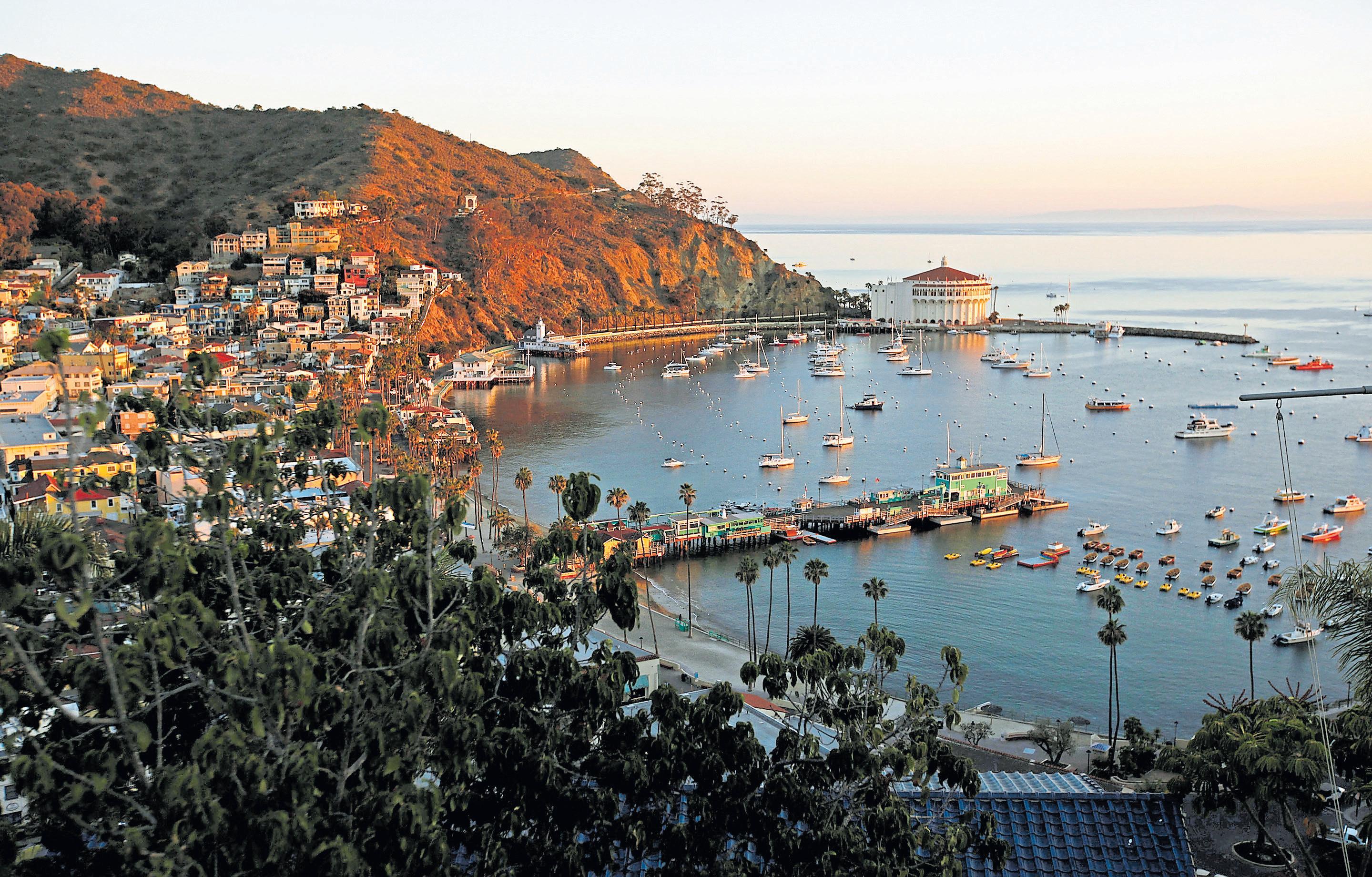

Catalina is a sweet, sun-kissed destination for any vacationer. It’s just mystery writers who gaze upon the sandy strand looking for caches for corpses.

For Los Angeles-based author Rachel Howzell Hall, Catalina is “a spot for the best locked-room story, except it’s an island.” The

frantic page-turning action in her 2023 novel, “What Never Happened,” revolves around obit writer Colette “Coco” Weber, who returns to Catalina 20 years after her family was murdered. What awaits isn’t exactly sunshine and sand — more like buried secrets, a violent home invasion and a serial killer — and there’s no way to escape, except by reading faster.

The island is the setting for more mayhem this spring in a sunnier — but still murderous

— follow-up to Catherine Mack’s witty best-seller, “Every Time I Go on Vacation, Someone Dies.”

Published last year and swiftly optioned for a TV series, the book-about-a-book sent amateur sleuth Eleanor Dash and her ex on an ill-fated, but very funny Italian book tour for Eleanor’s first novel, “When in Rome.”

The sequel, “No One Was Supposed to Die at This Wedding,” picks up the thread — you might want to take notes here — with a wrap party for the movie version of “When in Rome,” starring Eleanor’s childhood bestie, who is marrying the actor playing Eleanor’s ex. But things go seriously awry when Eleanor discovers a body at the wedding reception at Avalon’s Descanso Beach Club. Also, there’s a hurricane coming “because of course there is,” Eleanor tells the reader.

The briny spray and pungent

aroma of the Farallon Islands wafts off the pages of Wheeler’s “The Light on Farallon Island.” This historic gothic novel, an Oregon Book Awards finalist, weaves rich detail into the tale of Lucy, a young woman who has fled her past, not just to the West Coast but 27 miles beyond, taking a job teaching the lighthouse keepers’ children.

There’s some poetic license, of course, but the book takes inspiration from several real life events, including the 1858 Lucas shipwreck and a desperate, storm-swept crossing in the 1890s. And fans of gothic romance will swoon over the echoes of Bronte’s “Jane Eyre.”

“I didn’t set out to pay homage to them,” Wheeler says. “That arose organically from the character and nature of the Farallones themselves. I was especially captivated by the image of them at their foggiest and wildest and darkest — they felt so inherently gothic with the island itself standing in for

The Farallones’ lighthouse keepers and their families lived in these homes built in the 1870s.

JANE TYSKA/STAFF ARCHIVES

the forbidding stone manor and miles of empty ocean in place of desolate moors. To put it more fancifully, the Farallones went straight to my heart and met Jane there.”

Rupert Holmes may well be the multi-hyphenate to end all multi-hyphenates — a novelist, playwright, composer, arranger, producer and prolific songwriter who has won two Edgar awards for his mysteries, five Tony awards for his “Mystery of Edwin Drood” and a double-take (ours, when we learned this) for the multiplatinum “Escape,” better known as the “Pina Colada Song,” as well as other Billboard hits.

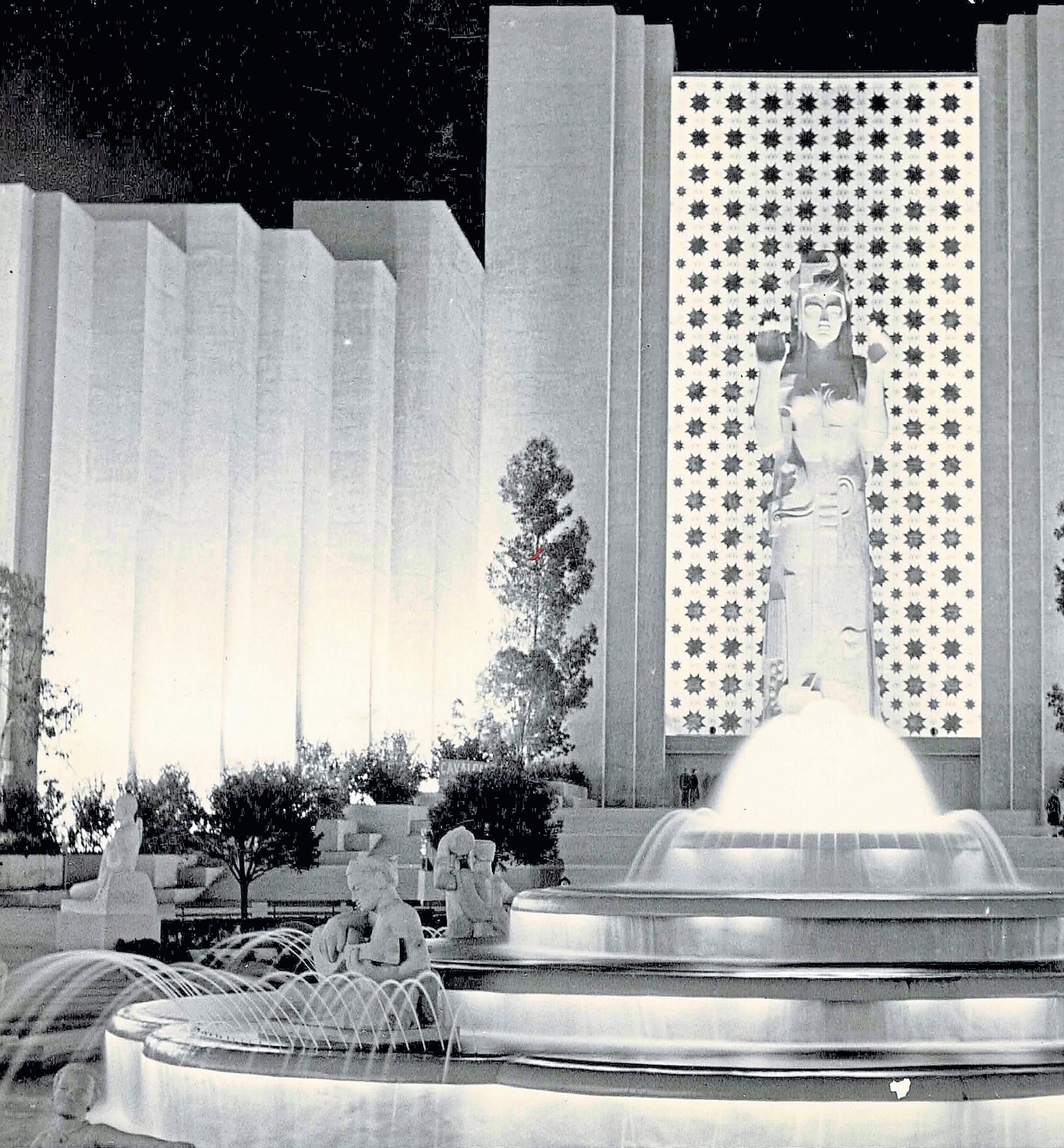

He also wrote “Swing,” a stylish, noir-ish murder-meetsjazz mystery set on Treasure Island during the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939-40. As the book opens, tenor sax man Ray Sherwood and his Jack Donovan Orchestra bandmates are checking in at Berkeley’s Claremont Hotel, when he receives a mysterious message from a UC Berkeley coed — a composer in search of an arranger. But when Sherwood goes to rendezvous with her on the Expo grounds, he arrives just in time to see a young woman plunge to her death from the Expo’s iconic Tower of the Sun.

Twisty mysteries abound, along with references to cat’s pajamas, wartime spies and plenty of jazz — not only in the swing-era, Expo setting but on the accompanying CD, where Holmes’ songs provide both atmosphere and clues.

STORY BY MARTHA ROSS ILLUSTRATION BY JUI ISHIDA

“Everyone has a story about Treasure Island,” says John Hogan, director of the Treasure Island Museum.

Visitors to his museum love to open up about their connections to this 393-acre island in the middle of San Francisco Bay, a landmass that didn’t even exist 100 years ago. Nonetheless, this flat, man-made island has played a unique, outsized role in illuminating the region’s vision of itself as a vanguard for American progress.

Two years after it was built in 1937, Treasure Island hosted 17 million people for a World’s Fair to promote international unity, then served as the point for wartime embarkation and debarkation for 4.5 million sailors, Marines and servicewomen headed to the Pacific Theater of Operations during World War II. More servicemen and women passed through Treasure Island in the years that followed — up until 1997 — as the Navy continued to use the island for command, electronics and nuclear weapons training and for regional command operations.

I recall my father, a Naval Reserve captain and veteran of the Pacific Theater, bringing our family to special-occasion dinners at the Officer’s

A blow for civil rights was struck here, and an historic expo mounted

90-year-old sculptures still inspires a heart-pounding sense of awe and discovery. The works are stunning and historically significant in their own right.

For the 1939-40 Golden Gate International Exposition, eight Bay Area artists — four women and four men — were commissioned to create monumental works that presented America’s hope for global unity, even with World War II looming.

The sculptures are among the original 20 featured in one

of the Expo’s most spectacular locations: the Court of Pacifica, named for an 80-foot-tall figure of a mythological goddess. Each of the sculptures represented people of the Pacific Rim.

They are in storage now with the expectation that they will again be publicly displayed on the island at housing and retail centers, said Bob Beck, director of the Treasure Island Development Authority.

The group includes one of three dancing Chinese musicians crafted by Fresno-born Helen Philips, who was later known for her avant-garde and surrealist bronzes, and two massive figures of Incan soldiers riding llamas by Sargent John-

A drone view of Treasure Island yields glimpses of the 22-story Tidal House apartment tower going up and the historic Administration Building that dates back to 1938.

JANE TYSKA/ STAFF ARCHIVES

son, a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance, even though he lived much of his life in San Francisco’s North Beach.

The majestic figure of a seated Polynesian woman is by Brents Carlson, who, like these other artists, trained at the now-shuttered San Francisco Art Institute. And an almost kinetic figure of an Indigenous boy wrestling an alligator, which shows signs of decades of wear, was made by Cecelia Graham, another San Francisco native.

The artists were among the thousands who found work on Treasure Island during the Depression, helping to prepare the island to host the exposition.

A few months after the

Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the Navy took formal possession of the island and knocked down or repurposed exposition buildings. It kept the Court of Pacifica and allowed the statues to stay, though the goddess Pacifica came down in 1942. By the early 1990s, six of the sculptures had been restored and were displayed in front of the Administration Building, which also houses the Treasure Island Museum. But the grand former Court of Pacifica eventually became a parking lot.

The island was also the setting

If you go

Pretty much any waterside perch on Treasure and Yerba Buena islands offers spectacular views of San Francisco Bay, the San Francisco and Oakland skylines and the Golden Gate Bridge.

Yerba Buena’s Panorama Park delivers a 360-degree view of the Bay, the exhibit dedicated to the Port Chicago 50 and the Point of Infinity, a 69-foot-tall stainless steel spire by Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto.

The Treasure Island Museum occupies just one room in the historic Administration Building, but it offers well-curated displays and a wealth of information about the island’s cultural and military past and its future. The museum also hosts special events and is a good place to start a self-guided walking or driving tour. Among other things, the museum’s downloadable guide recommends stops at “the YMCA mural,” which depicts the island’s history, and at the famed Doggie Diner heads, as well as a swing over to Yerba Buena Island to see the Nimitz House, the home of Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet during WWII.

Dining on Treasure Island? Two excellent, innovative restaurants emphasize outside dining. Mersea Restaurant, which serves casual comfort fare and boasts incredible views, is built out of container ships arranged around a garden of succulents; www. mersea.restaurant. Aracely Cafe offers a cozy, intimate experience whether you are sitting indoors or in outdoor lounge areas around a fireplace. Aracely is known for its daily brunch service. It’s open for dinner Wednesday-Saturday as well; aracelysf.com.

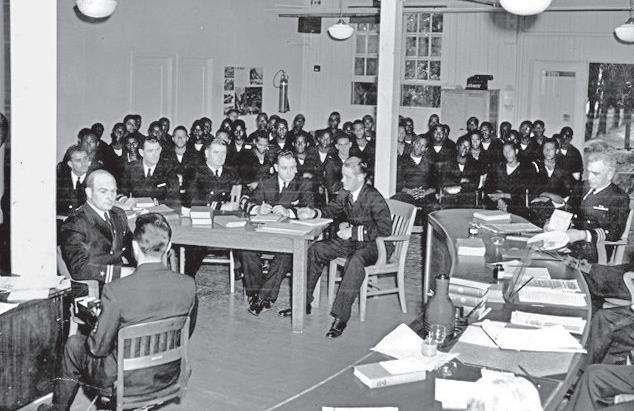

for a pivotal moment of civil rights history, a court martial for mutiny in the wake of the 1944 Port Chicago disaster that carried the threat of years of prison or even the death penalty.

Even though they were the defendants, Jack Crittendon and 49 other Black sailors, many in their teens and early 20s, had to occupy seats in the back of the room on Yerba Buena Island, which was part of the U.S.

Navy’s World War II-era Treasure Island Training and Distribution Center at the time. Their offense: refusing to return to work loading munitions at the Port Chicago Naval facility on Suisun Bay two months after an explosion killed 320 sailors and civilians, most of them Black.

In October, an exhibit commemorating the “largest mass military trial in U.S. history” was unveiled in

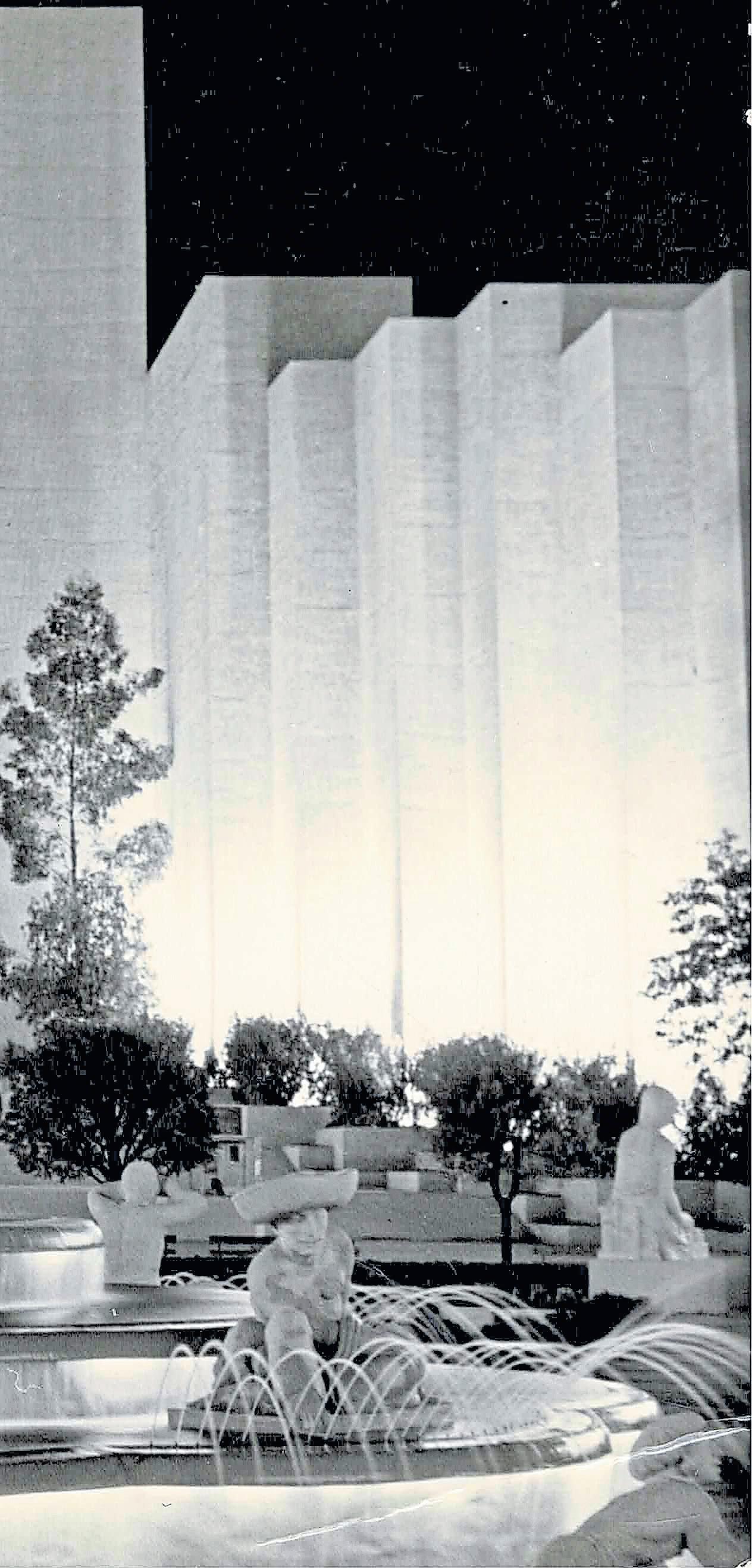

Above: The Court of Pacifica during the Golden Gate International Exposition 1939-40.

Right: The 1944 trial of the “Port Chicago 50” became a pivotal moment of 20th century military and civil rights history.

COURTESY OF THE TREASURE ISLAND MUSEUM

Panorama Park at the top of Yerba Buena Island. The trial is now recognized as one of the defining moments in 20th century civil rights and military history.

The explosion and trial were “devastating to him,” Jack Crittendon’s son, Hiram Crittendon said. The trial ended with Jack’s conviction, and he was initially sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Born in rural poverty in Alabama, drafted into the Navy after Pearl Harbor and serving his first assignment, Jack Crittendon was scheduled to go on guard duty the night of July 17, 1944. He told author Robert L. Allen, there was “a great big flash,” then he was thrown out

of a building. “People running and hollering, (men in the barracks) blown to pieces,” he said. The next morning, he was ordered to help with the search and rescue, finding “a shoe with a foot in it” and “a head floating in water.”

Three weeks later, he was among 258 Black sailors who refused to do the hazardous work, unless they received proper training.

The work stoppage was classified as mutiny, and 50 sailors were put on trial that September. In an unusual move, the Navy opened the trial to local and national media, prompting NAACP attorney and future Supreme Court Justice

Above: With the San Francisco skyline in the distance, a pair of cyclists relax in the courtyard at the Mersea Restaurant on Treasure Island.

MONDON/STAFF

The 18th China Clipper, a 74-passenger Boeing sea plane, hovers over an uncompleted Treasure Island in the preparation stages for the 1939 Worlds Fair.

STAFF ARCHIVES

Thurgood Marshall to attend and eventually commission a blistering, nationally distributed 18-page pamphlet on the Navy’s “bias, bigotry and bungling” that found its way to activist first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Public outcry over the trial became a catalyst for change in the military, with President Harry S. Truman signing an executive order in 1948 to desegregate the armed forces. Jack Crittendon died in 2017 at age 92, seven years before advocacy by groups like the Port Chicago Alliance convinced the Navy to finally issue a full exoneration of the sailors.

Now, the sailors’ heroism is being remembered with a set of panels in Panorama Park, some 300 feet above where the trial took place.

BY JACKIE BURRELL AND MARTHA ROSS

The Bay Area is so passionate about wine and beer, whiskey and gin, even our islands boast tasting rooms. You can sip cabernet on Alameda, do a whiskey tasting on Treasure or dabble in bubbly on Mare Island. Here’s just a sampling of possibilities.

The Golden State boasts plenty of wine passports and ale trails, but only Mare Island has a “Wet Mile,” where visitors are encouraged to “Eat like a mare. Drink like a sailor.” It includes a quartet of tempting libation stations, including The Quarters Coffee House and Vino Godfather Winery, Mare Island Brewing’s Coal Shed taproom and the soon-to-open Redwood Empire Whiskey, which is taking over the old Savage & Cooke Distillery.

Head for the island’s historic center, a row of stately two-story homes — officers’ quarters — that date to 1900, rebuilt after a 6.5 earthquake destroyed 14

officers’ residences in 1898. Today, Walnut Avenue feels like such a gracious portal to the past, you expect to hear Sousa wafting from the gazebo across the street.

Sip bubbly or a rosé of grenache on Vino Godfather Winery’s grand front porch, say, or taste your way through its award-winning, small-batch tempranillo or Prohibition Red in the parlor. There’s live music in the garden nearly every weekend (tickets start at $12) and charcuterie, cheeses and crackers available for purchase in the tasting room.

Details: Walk-ins are welcome at Vino Godfather Winery, which is open Thursday-Sunday at 1005 Walnut Ave.

in Vallejo; www.vinogodfather.com.

URBAN LEGEND AND HUMBLE SEA

Alameda

Alameda has become quite the destination for tasting rooms, taprooms and distillery tours. You can brewery hop from Humble Sea to Almanac, Faction and more, tour the distillery doings at St. George or taste your way through a flight at a winery — Dashe Cellars, say, or Urban Legend. The latter, which is owned by techies-turned-winemakers

Above: A couple enjoys a glass of pinot noir at Treasure Island Wines.

Right: Vino Godfather Winery at Mare Island is tucked inside one of the historic officers’ quarters built in 1900.

RAY CHAVEZ, JACKIE BURRELL/ STAFF

the place to be, brew in hand.

Details: Urban Legend is open FridaySunday by reservation (walk-ins welcome when space permits) at 1951 Monarch St., Alameda; https://ulcellars. com/. Humble Sea is open daily at 2350 Saratoga St.; https://humblesea.com.

Treasure Island

Treasure Island’s potential as a mecca for wine lovers began in 2007, when brothers Paul and James Mirowski opened their Treasure Island Wines collective on the former U.S. Naval base to produce and showcase smallbatch wines.

The warehouse-style building is both production and storage facility, with a laid-back tasting room in front that eschews the self-importance of Napa Valley and features wine that’s relatively affordable. There’s a kidand dog-friendly picnic patio, too.

Steve and Marilee Shaffer, does its tastings indoors as well as out on the patio, where stellar water views are paired with wine. So you can sample your way through “a trio” — a threewine flight of bubbles, say, cabernets or other delights — while you take in the city skyline.

Santa Cruz’s Humble Sea took over this corner of the former Naval Air Station in 2023, bringing its signature Socks & Sandals IPA, Seasquatch DIPA and laid-back surfer vibe to Alameda. When the weather warms, the umbrella-shaded picnic tables on the sandy patio are

The collective sells wines from six other local winemakers. On a recent Sunday, Umbriaso winemaker Dennis Hayes was pouring tastes of his award-winning 2022 Bianco Altopiano, a sauvignon blanc, as he talked about harvesting the grapes from a vineyard in the gorgeous-sounding Mayacamas Mountains on a 2,400-foot-tall plateau.

Prefer spirits? Second-generation Napa Valley winemaker Montgomery Paulsen has opened a retro whiskey tasting room for his brand’s Gold Bar Whiskey in Treasure Island’s historic, art moderne-style Administration Building. The structure served as the administration headquarters for the 1939-40 Golden Gate International Exposition and as the terminal for the Pan Am Clippers flying boats that once landed here.

Today, the tasting room and bar pay tribute to Depressionera jazz clubs, with one wall

looking especially rich and shiny: It’s lined with Gold Bar’s signature, 750-ml glass bottles, which are shaped like gold bars and stacked accordingly. Enjoy a “Gold Fashioned” and other takes on classic whiskey cocktails at the bar or expand your knowledge of whiskey mixology with one of the bar’s daily classes and learn to make

three iconic cocktails.

Details: Treasure Island Wines is open on weekends at the corner of 995 Ninth St. and Avenue I; www.tiwines.net. The Gold Bar Distillery is open for tastings Tuesday-Sunday at 1 Avenue of the Palms, No. 167. Mixology classes ($79$89) are offered most days; reserve a spot at https://goldbarwhiskey.com.

BY MARTHA ROSS

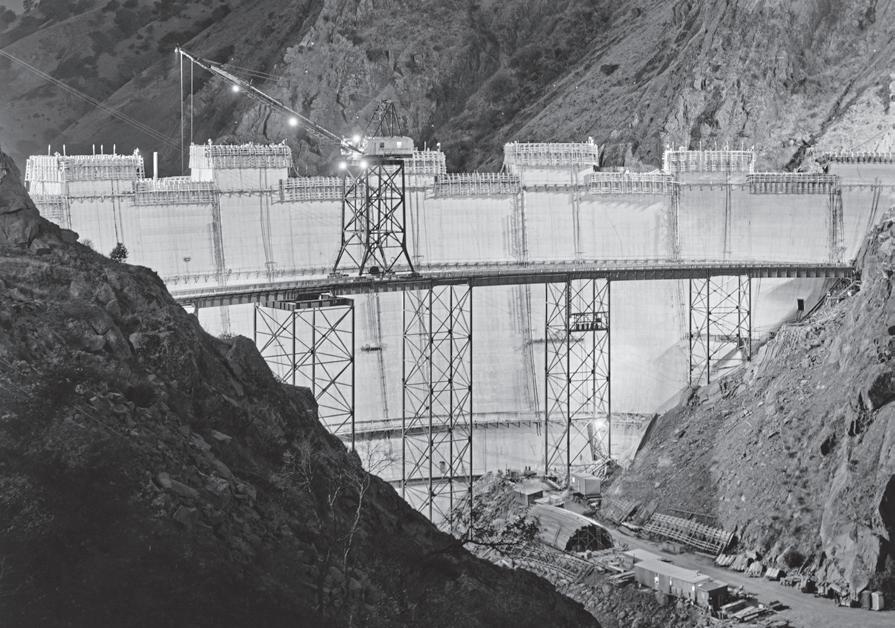

Ifyou look at a map of Lake Berryessa, a 23-mile-long body of fresh, blue water in the mountains east of Napa Valley, you’ll notice that its 165 miles of shoreline are jagged, broken up with deep, meandering inlets and island archipelagos.

Those strings of islands include tiny, hump-backed Goat Island, which used to be a small hill overlooking the former Berryessa Valley. Up until the 1950s, this valley was an agricultural jewel, home to rich soil, family farms, orchards, a famous stone bridge, Putah Creek and the small town of Monticello.

Then came the water — more than a million acre-feet filling the basin over the course of several years after the Monticello Dam was completed in 1957. This massive inundation wiped out a thriving community and one-eighth of Napa County’s farmland, though it created a new reservoir with remarkable new topography and beauty.

Many people visit Berryessa for boating, fishing, picnicking or

Far left: Goat Island serves as a reminder that the scenery around Lake Berryessa in unincorporated Napa County once looked very different.

JANE TYSKA/STAFF

Near left: Dorothea Lange photographed the destruction of a California landmark, Berryessa Valley. All trees were cut to within six inches above the ground. From “Berryessa Valley – The Last Year.”

swimming. They hike in the surrounding mountains or drive up Highway 128 from Winters to gaze into the maw of the Glory Hole — an engineering feat near the 304-foot-tall dam. It’s a circular spillway that drains the lake when the water level reaches 440 feet.

But visitors might not be aware of the lake’s unique history and that its waters now cover the location of a former town. It was such a mind-boggling concept in the 1950s that famed photographer Dorothea Lange and her assistant, Pirkle Jones, traveled to the valley multiple times to document its extinction. If nothing else, Goat and the other islands in the lake serve as reminders that the scenery here once looked very different.

A first-time visitor also may be surprised that Lake Berryessa feels so remote and that public amenities are limited, even though it’s less than an hour’s drive from Winters or Napa Valley. All roads leading to the lake wind around hills and peaks of sometimes harsh, rugged beauty. There’s the Cedar Roughs National Wilderness to the west and oak- and manzanita-covered hills, rising to 3,060-foot Berryessa Peak, to the east. In August 2020, an unprecedented lightning storm sparked a devastating fire in the tinder-dry hills that raged down to the lake and devastated much of the Spanish Flat neighborhood on the lake’s western shore and an additional 100 homes in another part of the lake.

Peter Kilkus, the Lake Berryessa News’ publisher, has described the area as marked by a series of tragedies, even before the 2020 LNU Lightning Complex fires. Some may vaguely remember that the Zodiac killer targeted two of his victims on a tiny spit of land — a landform that turns into yet another island when the lake’s water level rises during winter rains.

To Kilkus, the first tragedy was the destruction of Native

The remains of a residence destroyed by the LNU Lightning Complex Fire in Spanish Flat Aug. 22, 2020.

Top: The Morning Glory spillway at Lake Berryessa drops water down a vertical spillway into Putah Creek in Napa. This spillway has become affectionately known by Northern Californians as the “Glory Hole.”

JOSH EDELSON/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

American culture. For thousands of years, hunter-gatherer groups thrived in the rich natural environment of Berryessa Valley. But after European contact, they were driven out by settlers, sent to California missions or killed by smallpox or other diseases.

The second tragedy, he writes, was the destruction of Spanish culture after California was ceded to the United States in

1848. Still, Kilkus points out, the valley gets its name from two Mexican brothers, Sisto and Jose Berryessa, who received the valley from a land grant from the Mexican government. Debts eventually forced the Berryessa brothers to sell off much of their property. New settlers included farmers, ranchers and small-town businessmen, who transformed the valley

into a prosperous agricultural community. “The valley itself was flat and fertile and was considered to have some of the best soil in the country,” Kilkus writes.

Established in 1867, Monticello had at most 300 residents during its nearly 90-year history. Still, at various times, it supported a hotel, a school, a bar and general store. People would catch up on community gossip at the store or gather in town for rodeos, baseball games and “cow roasts.”

Tom Gamble, who owns Oakville’s Gamble Family Vineyards, says his family began farming in Napa County in 1916. Gamble is a descendant of James Gamble, co-founder of Procter & Gamble, and related to the Gamble family of Palo Alto. But the pride and joy of his grandfather, Launcelot Gamble, were the tracts of ranch and farmland he pulled together in the Berryessa Valley, including 3,000 acres on the valley floor. “My grandfather spent his life putting that ranch together,” Gamble says.

All that began to end after World War II with what Kilkus calls a third tragedy: the destruction of rural culture in Berryessa Valley.

America was still in its era of large-scale dam building, and officials in Solano County and the federal government wanted to find a reliable source of water for booming Solano County agriculture and Cold War-era military bases, including Travis Air Force Base. So they focused on a plan to capture the water of Putah Creek in a reservoir by constructing a massive dam across Devil’s Gate, a steep, rocky gorge at the southeastern end of the valley.

Gamble’s grandfather was among the valley residents who traveled to Washington to protest the dam’s construction, in part because the new reservoir’s water would only go to Solano County. But it was all for naught. Ground was broken for the dam in 1953. Photos by Lange and Jones show how the