CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 32

AT THE UNITED STATES POTTERS’ ASSOCIATION convention in December 1908, the organization’s historian, Henry Brunt, delivered a eulogy for two of its members: “The most noted change that has occurred in the personnel of the potters of the United States was caused by the death of two old and noted potters—Mr. Edwin Bennett and Mr. D. F. Haynes. It is singular that they both came from Baltimore, that they were both successful potters, and that they had once been partners in business, and that both should die within the short period of a few weeks.” 1 It was tting that Brunt should be the one to give this address as he was a friend to both men and had worked with them at what were Baltimore’s leading potteries in the late nineteenth century: Edwin Bennett’s eponymous rm and Haynes’s Chesapeake Pottery. While the varied and rich production of these two manufacturers was well-known to Brunt’s audience in 1908, it is less so today—and their majolica wares, in particular, are little recognized ( g. 32.1). Edwin

Bennett has been wrongly championed in ceramic lit erature as the pioneer majolica manufacturer in the United States, and yet, as this essay will show, the ware was but a small part of and late addition to his rm’s output.2 By contrast, Haynes’s company made a signi cant amount of the colorful lead-glazed ware and, in fact, was responsible for making Baltimore a leading center of American majolica production in the rst half of the 1880s. Why, beginning with the establishment of Bennett’s pottery in the mid-1840s, did Baltimore become home to two prominent American ceramic manufacturers? Founded in 1729, Baltimore became a leading American city largely due to its location on the Chesapeake Bay, a major coastal estuary that fostered easy access to the Atlantic maritime trade with Europe, the Caribbean, and other American colonies. Commerce and manufacturing grew throughout the nineteenth century, as the city’s reach expanded with the opening in 1830 of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O). The earliest commercial rail network in the United States, the B&O eventually connected Baltimore to the middle South and Midwest. The city and the surrounding regions contained important deposits of clay, int, and other raw materials, and had relatively easy access to coal—the resources necessary for the

development of its ceramic industry. Finally, by the second half of the nineteenth century, Baltimore was a major port of entry, second only to New York, for European immigrants to the United States, including many from England, ensuring a steady labor supply for the potting trade. In the 1890s, published chronicles of the city’s history, industry, and prominent citizens proclaimed it “the Liverpool of America”—comparing Baltimore to Britain’s leading commercial center and port. 3

David Francis Haynes

David Francis Haynes (1835–1908) was born to Reuben and Harriet (Marsh Clark) Haynes in Brook eld (now West Brookeld), Massachusetts, on June 26, 1835 ( g. 32.2).4 His childhood was spent on family farms in Brook eld and Barre, Massachusetts. In 1851, at age sixteen, he was employed by Ephraim Brown, who advertised in the Lowell, Massachusetts, directory that year as a “Dealer in Crockery, China, Glass, Stone & Earthen Ware, Table Cutlery, Silver Spoons, Britannia, Japaned [sic] and Plated Ware, Girandoles, Solar, Camphene and Fluid Lamps, Camphene and Burning Fluid.”5 Haynes seems to have quickly taken to the mercantile trade. From November 1855 to October 1856, he promoted Brown’s newly patented burglar alarm for money drawers

and doors in Britain and Continental Europe.6 An 1893 account of this trip notes, “His visits abroad, among the art treasures of England and the Continent, proved a revelation and an education to him.” 7 During this year, Haynes was primarily based in Birmingham, the center of Britain’s metalworking industry.8 From August through October 1856, he visited London and Paris, as well as Germany, the Netherlands, Scotland, and Ireland. Haynes made note of modern industry, historical and contemporary architecture, art, and design throughout his travels. By November 1856, Haynes had returned to Massachusetts, but he left again later that year or in early 1857 for Baltimore, where he would spend much of his life. 9 He did, however, maintain strong ties to his home state, including marrying Ephraim Brown’s daughter Anstress there in 1858.10 In Baltimore, Haynes found employment at Abbott and Son, later the Abbott Iron Company, where in 1861, he was put in charge of a new mill that produced the plates used to sheath the USS Monitor, the rst ironclad ship commissioned by the United States Navy.11

From 1868 to 1871, he was general manager of Abbott’s iron ore mine and smelting plant in Rockingham County, Virginia.12 His mercantile inclination reasserted itself when he opened a general store at the iron plant in August 1868.13 Through this enterprise, he sold clothing and household goods, proclaiming, “In hardware, tinware, woodenware, queensware, we have a well-selected stock.” 14 However, in late 1870 or early 1871, after the death of his wife and a ood that severely damaged both the ironworks and the store, he moved back to Baltimore.15

In 1871, Haynes returned to the china and glass trade, this time on the wholesaling side, when he became a third partner in the rm of Ammidon & Co. of Baltimore, leading “Importers and Jobbers in French and English China, Queensware of Every Description, Lamps and Chandeliers, Table Glassware, Castors, Spoons, Tea Trays and Table Cutlery,” etc.16 In 1875, the trade publication Crockery Journal pro led Ammidon & Co. as the largest importer of “china queensware, glassware, lamps, [and] chandeliers” in the country south of New York, with most of the stock coming “direct from Bohemia, and from the best factories at Limoges at France, and the far-famed potteries of Sta ordshire, England.” 17 The rm’s ve-story showroom and warehouse building on West Baltimore Street indicated “the vast amount of business transacted there,” which annually totaled “over $300,000,” and was “steadily on the increase.” 18 In 1876, company founder John P. Ammidon left the business, and the rm was reorganized as D. F. Haynes & Co. with a more narrow focus on wholesaling ceramics and glassware.19 As Haynes was very much aware, majolica was a signi cant segment of the crockery and glass trade in the late 1870s and early 1880s. A brochure anticipating the 1882 holiday season indicates that Haynes & Co. was importing “Beautiful English Majolica,” which it notes “is coming into such general use.”20 The company o ered retailers a number of di erent packages, each an assortment of several dozen useful majolica items, including tea sets, fruit plates, cake plates, owerpots, and comports ( g. 32.3).

As part of his wholesale business, in June 1879, Haynes formed an exclusive relationship with the newly founded Maryland Queensware Factory of Baltimore to distribute its full production.21 In addition to having a ready supply of “White Granite” and “C.C.” (cream-colored) wares “to meet the demands of the closest buyers,” Haynes promoted Maryland Queensware as “American manufacture, worthy of the State of Maryland,” going so far as having the wares marked with an eagle symbol reminiscent of the Great Seal of the United States, which is encircled by the words D. F. HAYNES & CO. BALTIMORE WHITE GRANITE 22 This venture was a success, and by the end of 1879, the factory with its three kilns and 150 workers was struggling to ful ll its many orders.23 By the following spring, “pushed to its utmost capacity,” it hired experienced practical potter Thomas McNulty (1832–1890), who had been a manager at Ott & Brewer, a leading Trenton pottery, to double its output.24 In addition to its more utilitarian production, including white granite in “the popular cable shape,” the rm began to make “novelties,” such as a “leaf comport, or cake plate, of beautiful outline and workmanship.”25

By 1881, Haynes was distributing a wide variety of wares from the factory, including “beautiful antique shape chamber sets” that were “hand painted with pansy decorations, relieved with bright gold and water-green bands,” along with other wares that were transfer-printed.26

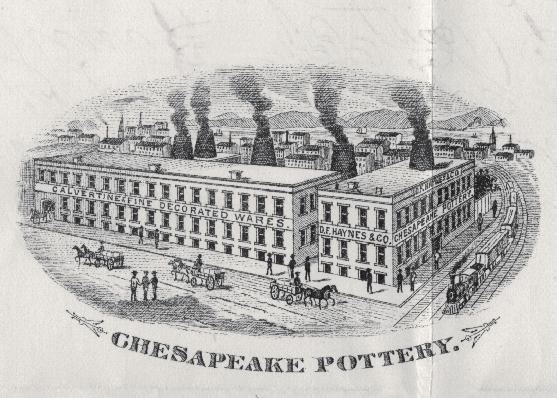

While it is likely that Haynes had direct in uence over Maryland Queensware production, in 1882 he was able to take full control of manufacturing by purchasing the Chesapeake Pottery, located on the southwest corner of Nicholson and Decatur Streets in the Locust Point section of Baltimore ( g. 32.4).27 The pottery had been established in 1880 by John Tunstall (ca. 1838–ca. 1890) and brothers Isaac (1842–1896) and Henry O. Brougham (1828–1891), English immigrants from Sta ordshire potting families, “for the

purpose of manufacturing yellow, Rockingham, and sanitary ware.”28 Setting up a three-story brick factory with one kiln was costly—and the necessary pro t margin not immediately achievable—and so by October 1881, to pay their creditors, the partners were forced to either rent or sell the pottery.29

In January 1882, Haynes purchased the business and set about enlarging and improving it, which included sta ng the works with experienced English potters. He hired John Watson (1836–1916) of Trenton to install “the most substantial and improved machinery” and William Brookes (1835–1890) to construct two additional kilns, something that Brookes had previously done in England for Worcester Royal Porcelain Company and J. & G. Meakin. 30 To manage the pottery with its force of approximately a hundred workers, Haynes hired Lewis Toft (1839–1904) and Frederick Hackney (1848–1892). Initial reports indicate that Toft was brought on to “take charge of the bodies and glazes and the kilns,” while Hackney was to be “in charge of the artistic department, and has for months been preparing his molds for the various lines of ware, experimenting with colors and materials. . . .”31 Toft had been employed at William Brown eld’s Cobridge Works in Burslem, Sta ordshire (see chap. 23), before immigrating to the United States in 1869. 32 He spent much of his career in the American potting center of Trenton, where, prior to his employment with Haynes, he was “the leading man on the sta of Ott & Brewer.”33 While Toft did not remain at the Chesapeake Pottery for long, he was crucial in its foundation and provided vital technical knowledge, including recipes for the clay bodies and saggers used early on by the factory.

34 Hackney held a leading role as manager at Chesapeake from 1882 through 1886—the period in which the rm produced majolica.

35 Born to a potting family in Hanley, Sta ordshire, he is described as a “graduate of Wedgwood’s famous factory” in the contemporary press.

36 Hackney was one of ve partners in the rm Hackney, Kirkham & Co. (later F. Hackney and Co.), which made majolica and other fancy wares at the Railway

as “the head of the artistic department” at Turner & Wood in Stoke-upon-Trent, makers of parian, majolica, and other wares.41 Haynes may have met Hackney there when he visited England and the Potteries in June and July of 1880, for Hackney traveled to Baltimore less than two years later to join Haynes in his new venture.42

Pottery in Stoke-upon-Trent between the spring of 1878 and the fall of 1879 (see chap. 26). In this venture, he was in charge of the design and glazing of the wares, which quickly captured the attention of the press. 37 By July 1878, trade reports proclaimed, “Their colors are rich, their designs are good, and the quality of the ware and glaze leaves nothing to be desired.” 38 Reports about the new rm reached the American trade press in the late summer of 1878, where it may well have been noticed by Haynes. In August, the Crockery and Glass Journal noted Hackney, Kirkham & Co.’s “excellent designs . the chief features being the excellent manner in which the colors are brought out,” and in September, the Pottery and Glass Trades’ Journal observed that the “young rm has booked considerable orders for the American market.”39 However, by the following year, the business underwent a change in management and eventually was taken over by Simon Fielding (1827–1905), one of the rm’s senior partners.40 By 1880, Hackney, “who has long been known as an art decorator,” was working

In 1891, David Haynes wrote an article on “American Pottery” for the Home Magazine, in which he notes that the “Chesapeake pottery of Baltimore lighted its res and began the manufacture of Majolica ware at a time when goods of that character were in great demand.” 43 The kilns of Haynes’s pottery were rst lit in August 1882.44 By early September, the Crockery and Glass Journal reported that “the majolica painters” at the factory were “busy putting on the fancy touches to a great variety of jugs, vases and sets intended to make a display in the trade procession of the Oriole festival,” a three-day civic event held in Baltimore.45 Chesapeake’s horse-drawn oat, one of three hundred presented by the city’s merchants and manufacturers, was indeed a striking presence in the festival parade, which took place on October 13, 1882.46 The Baltimore American newspaper notes the display was approximately eighteen feet long and featured an eighteen-foothigh pyramidal arrangement of goods with an “entablature at the top” that “bore the words ‘Chesapeake Pottery, D. F. Haynes & Co. Beauty and Utility Combined.’” 47 The American reports that Haynes was “superintending in person the designing and decorating of the di erent styles of ware, aiming to produce artistic and tasteful articles within the reach of persons of

moderate means,” and outlines in detail the items presented by the rm. The “leading style” was Chesapeake’s underglaze-decorated majolica, called Clifton ware (after a suburb of Baltimore) and described as “a display of bright colors of natural foliage upon a soft ivory-tinted ground, worked into a strong relief” (see g. 32.1).48 The undersides of most Clifton ware are stamped with two interlocking crescents that contain the words CLIFTON DECOR and surround the monogram DFH ( g. 32.5). The second major style the rm presented was Avalon Faience ware ( g. 32.6), which features “softer neutral tints” of enamels painted on the same body and ground glaze used in Clifton ware. This overglaze, often matte decoration, is generally not considered majolica today. Avalon Faience was named after the “Province of Avalon” (located in present-day Newfoundland), which in turn was named after the Arthurian Isle of Avalon by Sir George Calvert (later Lord Baltimore), who in 1623, obtained a charter for a part of what is now Canada.49 The undersides of this ware are usually stamped with a triangular formation that contains the words AVALON FAIENCE BALT. and surrounds the monogram DFHC ( g. 32.7).

Both Clifton majolica and Avalon Faience wares were made in “a great variety of pitchers, vases, teapots, sugar, cream, pickle, salad, and lemonade bowls, oatmeal sets, bread plates, etc.” The third style the rm exhibited was “ivory ware in plain shapes, suitable for dinner and tea sets,” which was transfer-printed. Majolica with a white ground, rst introduced by Wedgwood in 1878 as “Argenta,” had become popular by the time the Chesapeake Pottery began production of Clifton ware in 1882.

Many of the American rm’s patterns closely follow Wedgwood prototypes, and early trade press notes the “light cream or ivory tint” of its body. Among the rst designs were “six sizes of bramble jugs, teapots and sugars of the same design” as well as “cake plates and pickles of very attractive shapes, a very handsome line of vases, comports, salads, lemonade bowls, and many other useful and beautiful articles.” 50 Another report highlights a “a large rustic lemonade bowl,” or punch bowl, which is “embellished with a rich cluster on each side of blackberry leaves and fruit . . and nished at top and bottom with a knotted stick border” ( g. 32.8).

Haynes advertised its “Bramble” Lemonade Bowl, available in ve sizes, the following year ( g. 32.9). 51 Chesapeake’s “Bramble” decoration is clearly modeled after a Wedgwood pattern of the same name, which the English rm rst introduced on a garden pot in 1868 (see g. 14.30) and then on tea- and dessert wares in about 1878. 52 In fact, some pieces made by Chesapeake—for example, the teapot, creamer, covered sugar bowl, and jug—are direct copies of Wedgwood shapes ( g. 32.10). However, Haynes and Hackney, with their modelers, also created new forms in this pattern, including the lemonade bowls, a cylindrical vase with three blackberry feet ( g. 32.11), graduated vases with bows “tied” around their necks (see g. 32.36), pickle and butter dishes, and comports.

53

By early 1883, the Chesapeake Pottery had expanded its physical plant and added new categories of wares, including white parian, or bisque porcelain, in the form of oral plaques

and owers mounted on velvet, as well as the Arundel and Cecil lines—whose respective blue and drab stoneware bodies resemble the well-known jasperware originated by Wedgwood in the eighteenth century.

54 Much of this work was being done under the direction of Jesse Ash (1844–1915), an English-born parian and porcelain specialist who was hired by Haynes at the same time as Toft and Hackney. 55 In January, the pottery also completed a new building that would “add largely to the producing capacity of the works.”

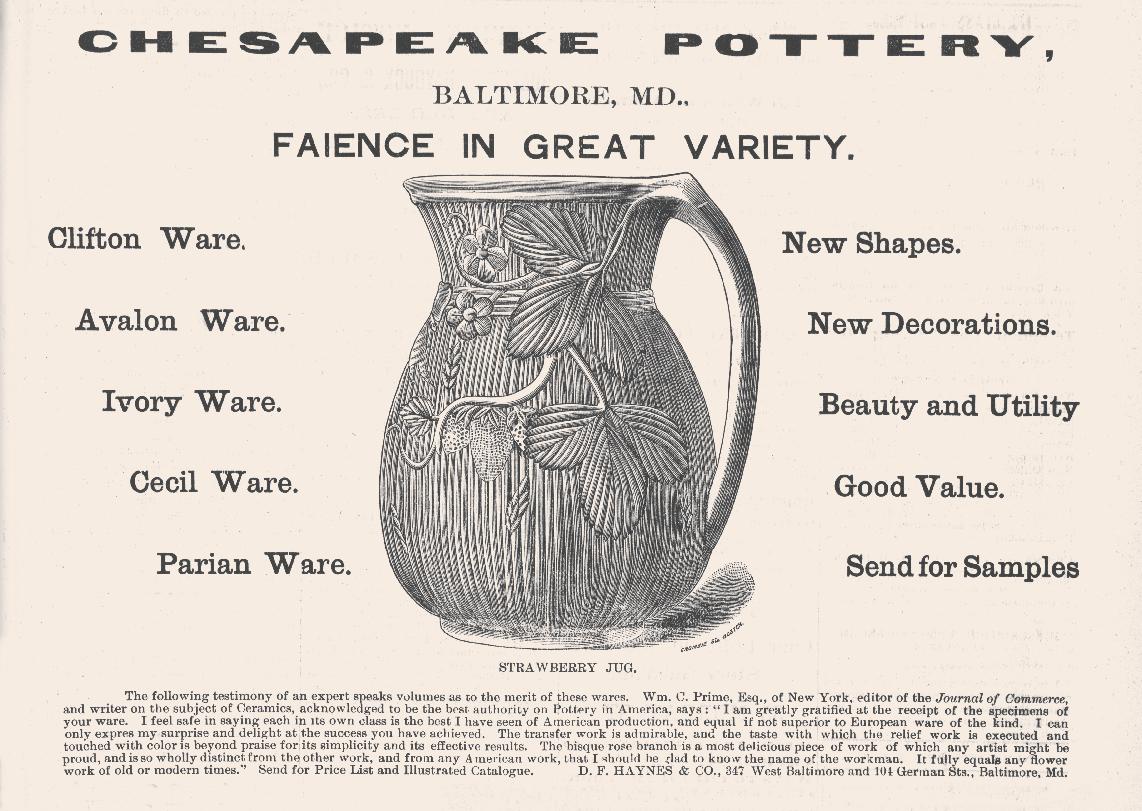

56 By February, Haynes was advertising a new addition to the rm’s “Faience in Great Variety”—a “Strawberry” jug (see g. 32.35).

57 Made in both Clifton majolica and Avalon Faience, it was part of a range of wares featuring the “Strawberry” decoration ( g. 32.12). Again, Chesapeake’s inspiration seems to have come from a Wedgwood prototype. In 1878, the British rm introduced a strawberry set in the “Boston” pattern, which includes a tray, creamer, sugar bowl, and individual dishes, and features a background of a sheaf of wheat tied at each end with a bow, wheat kernels poking through at intervals, and strawberry leaves, vines, owers, and fruits overlaying the wheat.

58 The Chesapeake version is by comparison less sophisticated, at least in the tray form, with its truncated sheaves of wheat, amorphous wheat kernels, and less elegant bow ( g. 32.13). The original shapes Chesapeake created in this pattern, such as the jugs, mugs, and a cake plate, are generally more re ned in their modeling and thus more appealing ( g. 32.14).

The rm also introduced other designs in Clifton majolica and Avalon Faience, probably in 1882–83, that parallel prototypes by Wedgwood and other leading English makers. Wedgwood’s “Fruit” pattern, with its molded basket-weave background overlaid with various kinds of fruit, served as one source of inspiration. Chesapeake made a close copy of this pattern on both an oval dish and an individual butter, only slightly varying the scale of the background and the assortment of fruit ( g. 32.15). Wedgwood’s “Fruit” pattern also likely inspired a series of jugs, but here the textured background is similar to the “rustic” or barklike motif found on the British rm’s (and Chesapeake’s) “Bramble” ware. The handles of the Clifton jugs are formed as entwined twigs glazed in browns and greens ( g. 32.16). Chesapeake directly copied a George Jones jug featuring a wren perched on an ivy vine among blades of meadow grass ( g. 32.17) and an Adams & Bromley water lily plate (see g. 16.20). 59 Chesapeake’s version was made in both Avalon Faience, with details highlighted in lines of gold and matte green, and Clifton majolica, in which the leaves are glazed a rich deep green and the ower in white with a yellow center ( g. 32.18).60

By April 1883, the trade press was extolling Chesapeake’s “almost endless variety” of “new styles of vases, water jugs, sugars [sic] bowls, cream jugs, teapots, fruit plates, oval cake plates, various kinds of salad dishes, [and] butter dishes,” all of which the rm featured in a “new forty-eight page catalogue.” 61 Among these new styles was “Japonica,” which the company rst advertised in March 1883 ( g. 32.19). This pattern re ects the burgeoning interest in Japanese art and design. To realize

32.8. D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery. “Bramble” Lemonade Bowl, ca. 1882–86. Earthenware with majolica glazes, h. 6 ⅞ × diam. 13 ½ in. (17.5 × 34.3 cm). Painted decorator’s mark. Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby. Cat. 307.

FIG. 32.9. D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery advertisement. From Crockery and Glass Journal, April 19, 1883, page 10. Smithsonian Libraries, Washington, DC.

FIG. 32.10. Left: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons. “Bramble” teapot, pattern no. M2903, designed ca. 1878; this example 1879. Earthenware with majolica glazes, 7 ⅜ × 8 ⅜ × 5 ⅜ in. (18.6 × 21.2 × 13.7 cm). Impressed marks: WEDGWOOD // YVH // M // L painted mark: 2903 . Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby. Cat. 213. Right: D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery. “Bramble” teapot, ca. 1882–86. Earthenware with majolica glazes, 7 × 8 ⅛ × 5 in. (17.7 × 20.5 × 12.5 cm). Stamped mark: CLIFTON DECOR (see fig. 32.5); impressed mark: 2 painted decorator’s mark. The English Collection. Cat. 214.

FIG. 32.11. D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery. Left: “Bramble” vase, ca. 1882–86. Earthenware with majolica glazes, h. 8 ⅝ × diam. 4 ½ in. (21.9 × 11.5 cm). Stamped mark: CLIFTON DECOR (see fig. 32.5); painted decorator’s mark. Cat. 314. Right: “Bramble” vase, ca. 1882–86. Glazed earthenware painted in enamels and gilding, h. 9 ⅝ × diam. 5 ⅛ in. (24.5 × 13 cm). Stamped mark: AVALON FAIENCE BALT (see fig. 32.7); painted decorator’s mark. Private collection, ex coll. Dr. Howard Silby.

FIG. 32.12. D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery. “Strawberry” jugs, ca. 1882–86. Earthenware with majolica glazes, left: 7 × 6 ¼ × 5 ⅝ in. (17.6 × 15.9 × 14.2 cm); right: 5 × 4 ⅜ × 4 ⅛ in. (12.7 × 11.2 × 10.5 cm). Both, stamped mark: CLIFTON DECOR (see fig. 32.5); both, painted decorator’s mark. John Collier Collection. Cat. 316.

FIG. 32.13. Left: D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery. “Strawberry” tray, ca. 1882–86. Earthenware with majolica

it, Chesapeake reworked motifs found in Wedgwood’s “Lincoln” pattern, introduced by the English rm in 1881–82 (see g. 31.15).62 Available in both Clifton majolica and Avalon Faience, Chesapeake’s “Japonica” pattern features fan palm leaves and branches of owering quince on a textured white ground, and is ornamented at the top with a diaper or lattice band, colored sky blue in the majolica version (see g. 2.48). The term “Japonica,” used at the time to refer to all things Japanese, is also among the common names for Chaenomeles japonica , or owering quince.

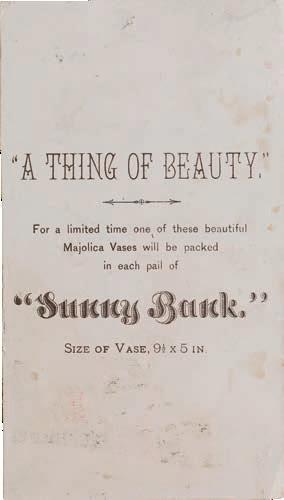

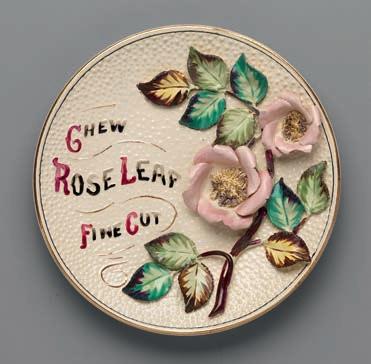

The Chesapeake Pottery also manufactured a number of items in Avalon Faience for other companies to o er as premiums or use as advertising. These include wares for A. Colburn Company of Philadelphia for its “Colburn’s Mustard,” and for G. W. Gail & Ax of Baltimore for its tobacco products, such as “Chesapeake Fine Cut.” Spaulding & Merrick of Chicago gave away a covered jar made by the Chesapeake Pottery to customers who bought pails of its “Sunny Bank” tobacco ( g. 32.20). This “limited time” o er was promoted by a trade card with an image of the jar on its front while the reverse proclaims, “These beautiful Majolica Vases” are “A THING OF BEAUTY” ( g. 32.21). Though described as majolica, the covered jars were, in fact, made in Chesapeake’s Avalon Faience with overglaze enamels. The decoration borrowed elements of the “Bramble” pattern in the blackberry canes as well as the barklike texture of the ground. P. Lorillard & Co. of New York, another tobacco company, promoted “Rose Leaf” chewing tobacco with a decorative Avalon Faience plate featuring a carefully painted three-dimensional applied rose cane ( g. 32.22). The pottery also produced similar decorative plates not branded as promotional items, including one marked CLIFTON DECOR that is embellished with a brightly painted butter y and a owering, fruit-laden blackberry cane on a pebbled white background ( g. 32.23). Intended as wall decoration, it is typical of the barbotine or raised- ower majolica wares being introduced by both American and British manufacturers in the early to mid-1880s (see gs. 24.32, 24.33, 26.24, 26.29).

By the end of May 1883, Haynes was promoting the rm’s new Cecil ware, or drab stoneware.63 The geranium motif on the Cecil vase pictured in the rm’s May advertisement was also applied to Avalon Faience and Clifton wares. An impressive example incorporating this pattern is a vase that Chesapeake made as a stand-alone piece and also used as a lamp base ( g. 32.24).

The vibrant colors of the geranium leaves and owers are echoed in the lappets edging the top and bottom of the ceramic. The geranium motif was also employed on a range of vases and jugs, and on an oval dish, all of which was o ered in both Clifton majolica and Avalon Faience ( g. 32.25). Other introductions at this time include parian gural plaques by James Priestman (1838–1913), “a talented young designer and carver of decorative work” from Boston who was active in Baltimore in this period.64

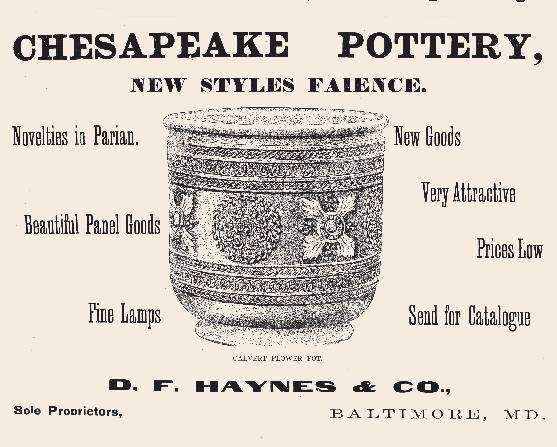

In 1886, the Crockery and Glass Journal remarked on the “rapid dying out of the once popular majolica” in multiple colors and the growing interest in “articles modeled in good style with the ornament in relief and covered with a monochrome glaze.”65 The trade paper rightly points out that this was “simply an old friend in a new dress”—and that “the popular line is nothing more nor less than majolica, technically considered.” An example of this new class of ware was recorded three years before, in June 1883, when the same journal noted new “vases with highly artistic geometric bands in rich olive and blue” that would soon be o ered by Chesapeake Pottery.66 Dubbed “Calvert” after the family name of the Barons of Baltimore, the proprietors of the

colony of Maryland, this product, when it is marked, usually displays the CLIFTON DECOR stamp (see g. 32.5). An August 1883 report records that Calvert was available in “vases of four patterns, jugs of three patterns,” and would be made in a “great variety of other articles.”67 The reporter extols it as “at once chaste and striking” and notes the “colors are very rich, being blue, olive and green” ( g. 32.26). Later that year, a New York critic commented that Calvert features “the same low relief decoration, zones of ornament, and sober-colored glazes” as stoneware made by Doulton & Co. at its Lambeth Pottery in London.68 Doulton’s decorative stoneware, which it marketed as “Lambeth Faience,” became widely known in the United States through the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia.69 While likely inspired by Doulton but not copied directly, Chesapeake’s Calvert continued to be a mainstay of the company’s o erings through 1885. It was made in range of forms, including a owerpot featured in a September 1883 advertisement ( g. 32.27). This latest majolica line met with success and was even carried by exclusive retailers such as Ti any & Co. of New York.70 Chesapeake wares were now sold widely across the country, including in New England, the South, and as far west as California.71

In 1884, the rm continued to prosper—the factory was enlarged yet again, and Chesapeake engaged a Boston agent.72 It also expanded its product line by adding “Calvertine Faience,”

which, as indicated in the name, is related to Calvert ware. Similar to Avalon Faience in terms of its decoration, Calvertine Faience features an ivory earthenware body covered in a lustrous clear glaze, with molded ornament highlighted in neutral and pastel-colored matte-overglaze enamels and gold ( g. 32.28). First advertised by the company in August 1884, the range includes a variety of ornamental jugs and bottles, as well as clocks. Calvertine was made in three patterns—“Oxalis,” “Pansy,” and “Oak”—and decorated in “light fawn, olive or gray, and relieved with gold,” the e ect of which, the company claimed, is “suggestive of Royal Worcester, yet not an imitation” ( g. 32.29).73 At least some of the new Calvertine shapes were also available in the solid-color majolica glazes used on Calvert ware. An “Oak”patterned clock features a striking combination of a leaf motif and lion’s head embellishments on the green-glazed case, while a clear glaze applied to the face reveals the ivory body color, with the numbers and other molded details highlighted in gold and black ( g. 32.30).74 By the year’s end, more items had been added to the Calvertine line, including “an owl card receiver,” which is shown on the back cover of the rm’s 1885 catalogue.75 This deluxe portfolio features another Calvertine card receiver on its front cover, and the publication’s contents reveal a range of wares in the company’s then principal lines: Avalon Faience, Severn, and Calvertine ( g. 32.31A). While majolica wares were probably still available from Chesapeake in 1885, they are not shown in this catalogue—with the exception of some lamps in what is likely solid-color majolica glazes ( g. 32.31B).76

World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition, 1884–85

In the summer of 1884, Maryland set about “securing a full and proper representation of the State commensurate with the importance of its resources and the value and variety of its industries” for the upcoming World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition to be held in New Orleans between December 16, 1884, and June 1, 1885.77 Among the resources to be represented in the state’s display were “Maryland clays . . in the raw material and its products,” including “specimens of earthenware, chinaware, stoneware, tobacco pipes, terra cotta work, sewer pipes, re clay brick and a large collection of the famous Baltimore-made brick.” 78 D. F. Haynes & Co. showed a range of Chesapeake Pottery wares in this display, including parian plaques by Priestman, Avalon Faience tableware, teaware, and toilet sets; Calvert vases and jugs in solid-color majolica glazes; Calvertine jugs and card receivers; and clocks, lamps, and other wares in unspeci ed decorations.79 Haynes’s “beautiful display of Maryland pottery” was judged by one critic to be “ nely executed and the e ect harmonious and attractive.”80

The Maryland presentation, especially the Chesapeake Pottery wares, captured the attention of the second secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Spencer Fullerton Baird (1823–1887). He was so impressed that he wrote to George W. Bishop,

32.26. D. F. Haynes & Co., Chesapeake Pottery. Calvert ware vases, ca. 1883–86. Earthenware with majolica glazes, left: h. 5 ¾ × diam. 3 ¾ in. (14.6

Maryland’s senior commissioner for the exposition display, in April 1885: “There are among the objects exhibited by your State in the New Orleans Exposition many which would be of the greatest service to the National Museum. . . Kindly advise me of the best steps to take in securing these for permanent deposit in Washington.”81 Baird did receive a gift from D. F. Haynes & Co. of eleven pieces to be “placed permanently, in the name of the makers, in the National Museum at Washington.”82 Although the Smithsonian Institution had been established by the United States Congress in 1846, the creation of a national collection did not become a strong focus until the 1870s; the rst museum building and exhibits opened in 1881. Baird was a driving force

behind the rapid expansion of the collection, securing gifts such as the one from Haynes, which included two Avalon Faience “Bramble” jugs, an Avalon Faience “Japonica” sugar bowl, an Avalon Faience “Chrysanthemum” jug, two parian plaques, two Calvert jugs ( g. 32.32), and three examples of Calvertine Faience (see g. 32.37).

The Smithsonian, however, did not acquire an example of Severn ware, Haynes’s newest o ering, introduced by the rm in early 1885.83 Available in a variety of jugs and vases, Severn relies on the warm tones of Maryland clays, which are covered in a clear glaze. The pieces are accented with geometric bands of ornament like those found on Calvert and Calvertine wares, but here the bands are nished with matte gold or neutral tones with gilded highlights. Raised decorations in gold and silver are sometimes arrayed across the smooth areas between geometric bands ( g. 32.33). Very much in the Aesthetic taste, Severn is quite far removed from the company’s majolica lines of 1882.

In January 1885, David Haynes took a less prominent role in his wholesaling business, which became the separate rm of Ramsay, Baker & Co. (the names of Haynes’s two partners), while D. F. Haynes & Co. was reorganized to solely operate the Chesapeake Pottery. 84 A year later, Haynes left the wholesaling business entirely and focused his e orts on ceramic manufacture. 85 The pottery seems to have discontinued production of majolica at about this time. A sale of Chesapeake “samples, trial pieces, and odd lots” in December 1885 encompassed a wide variety of items, including “Avalon Ware, Severn Ware, Eggshell Porcelain, [and] Parian Medallions,” but advertisements for the auction make no mention of majolica or of Clifton and Calvert wares, the pottery’s majolica lines.86 Chesapeake’s principal new o ering in 1886 was “Buttercup Ware,” which appears to have been an evolution of Avalon Faience. Advertisements for Buttercup strongly indicate that the company was no longer producing majolica. The new line included “jugs, cuspadores, teapots, sugars, molasses cans, salads, comports,” etc., and Haynes’s advertisement for it asserts, “This ware, while designed to take the place of Majolica, does not resemble it in any way.”87

Changes in the pottery’s o erings were mirrored in changes to its leadership. Chesapeake’s long-time manager, Frederick Hackney, left the company in April 1886.88 He set up a china decorating business in Baltimore that may have subcontracted with Edwin Bennett, Haynes, and other rms, before he returned to Sta ordshire in the late 1880s. 89 In 1886, Haynes hired Henry Brunt (1852–1915) to help manage the pottery, provide new artistic direction, and introduce new lines. Brunt was an English potter from Stoke-upon-Trent who, prior to coming to Baltimore, trained at George Jones and Minton as well as worked in Trenton.90

A signi cant transition for the Chesapeake Pottery occurred at the end of 1886 and beginning of 1887. On November 9, 1886,

George R. Miller, a major investor in D. F. Haynes & Co., died, and Miller’s $25,000 stake had to be returned to his estate.91 The company was unable to produce this sum and so Haynes was forced to sell the business at auction in February 1887.92 The purchaser was E. (Edwin) Huston Bennett (1856–1941), son of Edwin Bennett, who paid “$13,000 for the property and plant, and $10,000 for the stock on hand,” and retained Haynes as general manager, along with Henry Brunt and the approximately 150 employees of the rm, which was o cially renamed “Chesapeake Pottery Co.”93

Bennett’s ownership coincided with a shift in focus for the pottery that seems to have already been underway.94 The rm was soon to introduce the “Arundel Dinner & Tea Service,” with shapes largely designed by Brunt.95 This “semi-porcelain,” or re ned white earthenware, line met with critical approval. As a writer for the Art Amateur magazine, who saw Arundel ware on display in a New York department store window, noted in June 1888, “Both in form and in decoration they are better than similar imported ware, and they cost no more.”96 In addition to tableware, Chesapeake o ered a wider array of toilet sets, which had been a mainstay since 1882. Both table- and toilet wares produced by the company more and more relied on transfer-printed patterns, many of which were further decorated with color and gilding. Under Bennett’s ownership, Chesapeake remained a leader among American potteries, winning multiple prizes in 1888 and 1889 at expositions of ceramics and glass sponsored by the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (today the Philadelphia Museum of Art).97 The prizewinning pieces in 1888 include a large porcelain vase featuring “a group of dancing boys with owing drapery, modeled and painted in pink china slip,” designed by Henry Brunt and Herbert W.

Beattie (1863–1918), and a “Moorish”-style vase by Fannie Haynes (1860–1944), David Haynes’s daughter, which was subsequently purchased by the Pennsylvania Museum.98

In 1890, Haynes was able to buy back a portion of the business, becoming partners with E. Huston Bennett, and the rm’s name was changed to Haynes, Bennett & Co.99 The company’s wares made up a large part of the United States Potters’ Association’s display at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, probably because of Haynes’s position as head of the group’s Art and Design Committee. Chesapeake showed a range of ornamental items, including clock cases and vases, chief among them the two-foot-tall classically inspired Calvert vase, as well as eight styles of toilet sets, such as the Alsatian set decorated with transfer-printed scenes from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. 100 The company was awarded a rst-class medal and diploma at the fair, honors that Haynes and Bennett touted in their promotional materials, including in a brochure showing the rm’s tablewares, vases, clocks, lamps, and other ornamental items.101 Haynes, Bennett & Co. o ered many of these models as “blanks,” or undecorated, for use in china painting, a popular pastime.102

In early 1895, Haynes was able to buy out Bennett and bring in his son Frank Reuben Haynes (1869–1938) as a partner.103 Renamed D. F. Haynes & Son, the rm continued to make mostly ornamental wares, often with transfer-printed decoration and, by about 1900, in glazes applied with a spray gun—as seen on examples in a view of the company’s decorating rooms from about

this time ( g. 32.34). Frank Haynes continued to operate the pottery, but it began to falter after his father’s death in 1908, and by 1912, was forced to shut down.104 After attempting to revive the business over the next few years, he sold the property in 1916. It eventually became part of the site of the Domino Sugar plant which is still in operation in Baltimore’s inner harbor.105

David Haynes was perhaps exceptional among American potters for his active engagement with the wider art and design community and for his enthusiasm for art education, especially for women. He cultivated connections to artists, critics, and educators in order to foster the success of his own business, and by the second half of the 1880s, to encourage the American ceramic industry to work with trained artists and designers— and to ensure a ready supply of the same by supporting industrial art education.

While Haynes’s involvement with artists and critics prior to owning the Chesapeake Pottery is unclear, it seems likely he kept up with trends in art and design as a successful wholesale merchant specializing in ceramic and glass tableware and decorative items. He was also probably aware of the English pottery industry’s reliance on trained artists and designers, having spent nearly a year in Britain in 1855–56. In any case, he would have known of artist designers working at major English rms such as

Minton and Wedgwood through press accounts in the Crockery and Glass Journal, to which his company was an early subscriber and in which it advertised from the trade paper’s founding in 1874.106 As the owner of Chesapeake Pottery, Haynes employed a number of designers and artists, most of whom are little known, if at all, beyond the work they did for the rm.107 After Haynes purchased the pottery, he seems to have used his associations with prominent artists to create greater publicity and demand for his factory’s o erings. He worked hard to cultivate an image of his wares as artistic productions by continuously sending samples to and corresponding with leading critics and artists, including painters Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900)108 and William Hart (1823–1894), and sculptors Thomas Ball (1819–1911) and John Quincy Adams Ward (1830–1910). Haynes subsequently published their praise for Chesapeake products in his rm’s promotional materials.109

Haynes’s interactions with leading journalists and critics would prove even more fruitful. In November 1882, only a few months after he began production, Haynes’s correspondence with William C. Prime (1825–1905), editor of the New York Journal of Commerce resulted in a lead editorial proclaiming Chesapeake’s new majolica and faience to be “equal to any European work of their class in potting, glaze and decoration.” 110 Prime was not only a prominent journalist and author, but also an art historian. He was instrumental in founding what is now the Department of Art and Archaeology at Princeton University

and was the rst vice-president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.111 Moreover, he had a special interest in ceramics—among the many books he authored is Pottery and Porcelain of All Times and Nations (1878).112 He and Haynes seem to have conducted an active correspondence in the 1880s and Haynes used quotations from one of Prime’s early letters in his rm’s rst advertisements ( g. 32.35; see also g. 32.19). Framing this testimony as that of “the best authority on Pottery in America,” Haynes quoted Prime’s contention that Chesapeake’s wares, including its Clifton majolica, “were the best I have seen of American production, and equal if not superior to European ware of the kind.” 113 Haynes’s exchanges with Prime, which included sending him samples, resulted in many mentions within the New York Journal of Commerce, including one in 1885 that likens Haynes to Josiah Wedgwood I (1730–1795) for his ongoing experimentation and striving for artistic excellence. In this article, Prime notes that he had repeatedly highlighted Chesapeake Pottery wares in previous ones “because they are of peculiar importance in the history of the pottery industry in America.” 114

Though Haynes may have found an ardent champion in Prime, his relationship with other in uential critics was more complicated. Montague Marks (ca. 1847–1905), editor and publisher of the Art Amateur, also regularly reviewed productions of the Chesapeake Pottery. Subtitled “A Monthly Journal Dedicated to the Cultivation of Art in the Household,” the Art Amateur was an important vehicle for the arts, and an advocate

for integrating artistic design and products into everyday interiors—in other words, a leading journal for the promotion of Aesthetic movement principles in the United States.115 In February 1883, Marks reviewed the rst Chesapeake wares sent to him by Haynes, praising them as “creditable to the taste of the rm, as they are to its enterprise. . They mark a forward step in the application of art principles to the production of attractive ware of American manufacture for the adornment of the average home.” 116 However, in the same article, he questions Prime’s “unstinted praise,” and notes that though the Clifton majolica “body is solid, the glaze is excellent and the decoration is suitable,” he “would suggest that the imitation blue ribbon around the neck of the vase is not in particularly good taste” ( g. 32.36). He has even less regard for the Avalon Faience samples he received, deeming their decoration “rather tawdry.” 117 By November 1883, Haynes had sent the Art Amateur more examples of his latest productions, including parian plaques of cow’s heads and Calvert majolica vases and mugs. Marks proclaimed that “we have hardly anything but praise” for these samples, that the Calvert wares “are all good in form, and the enamel is faultless,” and that one vase in particular is “beautifully modelled.” 118 By 1885, Marks was again both criticizing and praising the Chesapeake wares sent to him by Haynes, remarking that the parian plaques were not in the best artistic taste, but no worse than European versions. He was initially complimentary of the Calvertine samples, writing, “The glaze and body of this beautiful cream-colored ware are excellent, and the simple decoration are harmonious and in good taste.” He then added, however, “The forms of the vessels are new, but they are not good,” referring to the card receiver as “nothing more or less than a well-kneaded apple ‘turnover,’ with the apple omitted” ( g. 32.37).119 Nonetheless, despite equivocating at times, Marks and his journal would go on to regularly commend Chesapeake Pottery productions through the end of the 1880s and into the next decade.120

By the 1890s, Haynes had also become acquainted with the pioneering and in uential ceramic historian Edwin AtLee Barber (1851–1916). Chesapeake is among the manufacturers that he highlights in a January 1892 article published in Popular Science Monthly outlining recent developments in the United States potting industry.121 In this piece, Barber calls Haynes “an artist and designer of the highest rank” who has “invented a number of new bodies and produced a wealth of beautiful designs to-day beautifying the homes of thousands who could not otherwise enjoy the possession of works of artistic merit.” 122 As a historian, the latter traced not only current productions of the factory, such as its Merchant of Venice wares, but also admired the parian plaques and Severn ware of the mid-1880s. Barber, who had a fondness for majolica (see chap. 9), also praised the earliest Chesapeake production: “Clifton ware from this manufactory belongs to the majolica family, and is said to equal, if not surpass, in body the famous Wedgwood ware of the same class.”

123

In his landmark book on American ceramics, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (1893), Barber devotes ten

illustrations and more than twelve pages to Haynes and his pottery, one of the book’s most extensive manufacturer pro les.124 His account not only outlines Haynes’s personal history and the productions of the Chesapeake Pottery, but also celebrates Haynes and his work wholeheartedly: “No one of our potters has done more to re ne the wares for daily household use than Mr. Haynes. He has always held it to be of much greater importance to elevate the quality, as far as possible, of the entire pottery product of the country, than to produce a few ne pieces that should be within the reach of only the wealthy.” 125 Tellingly, Haynes is one of only ten men singled out by Barber in his preface “for valuable assistance and advice.”

126 By this point, Haynes had served for several years as head of the committee on design for the United States Potters’ Association, and so Barber’s praise seems at least partially due to this advocacy for artistic design and training in the American ceramic industry.

Haynes’s promotion of art education and his engagement with educational institutions was long-standing by the 1890s. His relationship with the Maryland Institute Schools of Art and Design in Baltimore (today Maryland Institute College of Art) was especially fruitful—ensuring a steady ow of welltrained artists and designers, mostly women, for his pottery. His daughter, Fannie, was a graduate of the Maryland Institute and may have helped foster this relationship.127 By the fall of 1882, Haynes had set up a workshop at the Institute where pupils not only received instruction in pottery decoration but also were paid for their work.128 By the end of the year, between thirty and forty young women were decorating Chesapeake wares under the supervision of Fannie Haynes.129 By 1884, Haynes employed about sixty Maryland Institute graduates as decorators at his pottery, and these “young ladies” worked in “bright and cheerful quarters, with a lunch-room adjoining.” 130 That year, Haynes conducted a competition among Institute students to create

designs for Chesapeake, several of which were chosen for commercial production ( g. 32.38).131

Haynes’s encouragement of art education and professional development for women is noted as singular in a report on industrial statistics for the state of Maryland in 1884–85. This document records that the Chesapeake Pottery “a ords a eld for the employment of female talent in decorative arts which has been gladly accepted by many of the students of the art schools of the Maryland Institute” and that the women “employed in this industry occupy the highest grade among female employees of the State.”

132 It notes that women decorators, however, were paid the least among pottery workers, earning approximately $1.20 per day, while male painters and gilders earned $2.50 per day.133 In 1886, Haynes’s female decorators organized a strike for better wages. They were successful—an unusually generous move for a pottery manufacturer in the period when going on strike often resulted in the loss of one’s job.134 Haynes’s advocacy was again highlighted in a state report, this one for 1888–89, which focuses in particular on female and child labor in Maryland. Haynes was one of the chief authorities consulted and is thanked by name in the document’s introduction, which also quotes an article on art education for industry provided by Haynes.135 It is perhaps not surprising that the introduction also states that “the attention of [Maryland’s Bureau of Industrial Statistics] has been particularly directed to the manufacture of ceramic goods, and the opportunities a orded in that industry for the employment and development of the higher grades of female labor.”

136 In a section of the report including excerpts from letters written by employers to accompany their answers to the state’s survey, Haynes clearly outlines his thoughts: “I beg to say that I nd [women] equally as intelligent as men are, and more reliable and faithful to their duties. The great drawback to the working girls and a future that discourages them, is the small pay they receive for their labor.”

137 According to the report, Haynes employed thirty-one women ages twenty-one to forty, and seventeen girls ages fourteen to twenty, at a time when no other pottery in Maryland employed adult women and one other employed girls.138 Haynes would continue to be involved with the Maryland Institute and employ its graduates until his death in 1908.139

Edwin Bennett (1818–1908) has been hailed as the rst American manufacturer of majolica.140 While he has been rightfully celebrated as a pioneer of industrial production in the United States ( g. 32.39), it is unlikely that his Baltimore pottery produced majolica before the 1870s or 1880s—and even then, the colorful lead-glazed ware did not form a large portion of his factory’s output.

Bennett was born on March 6, 1818, to Daniel and Martha Webster Bennett in Newhall, Derbyshire, England.141 His father was the “principal bookkeeper for a large coal mining com-

pany for more than 50 years.” Late in life, Edwin recalled that he had “received a common education” in Newhall and, at the age of twelve, was apprenticed at the Harrison & Cash pottery in nearby Wooden Box, now Woodville.142 Historian Llewellynn Jewitt (1816–1886) records in The Ceramic Art of Great Britain (1878) that Woodville, whose “inhabitants are principally potters and colliers” was “noted for extensive manufactories of Derbyshire ironstone ware; cane-colored, Rockingham, black, bu , and brown wares; sanitary goods, terra cotta, &c.” 143 In 1841, after completing his apprenticeship and working several years in the local pottery industry, Edwin Bennett left England with his brothers Daniel (1815–1892) and William (1821–1889) to join a fourth brother, James (1812–1862), who by about 1840, had established the rst pottery located in what would become one of the leading ceramic manufacturing centers in the United States: East Liverpool, Ohio. In 1844, the Bennetts left East Liverpool for Pittsburgh to establish Bennett & Brothers, a new enterprise that made “Fancy Rockingham Ware, Ironstone Cane Ware, &c. &c.” 144 In 1845 or 1846, Edwin Bennett moved to Baltimore, where he would establish his own pottery.145 He received permission from the Baltimore city council on May 13, 1847, “to erect a queensware manufactory” on the corner of Canton Avenue and Canal Street (today Fleet Street and South Central Avenue) in the Fell’s Point section of the city.146

In about 1849, Edwin’s brother William joined him in Baltimore and remained part of the enterprise, known as E. & W. Bennett, until about 1856.147 In these years, the rm manufactured yellow- or cream-colored and Rockingham wares. The Bennetts’s Rockingham, with its rich mottled-brown leaded glazes, is considered among the nest produced in the United States.148 E. & W. Bennett employed the modeler Charles Coxon (1805–1868) from about 1849 until 1856.149 From a Sta ordshire potting family, Coxon immigrated to the United States in 1849 and is credited with designing the wide variety of relief-molded wares produced by the Bennetts in the early years of the factory. One is a jug depicting Chesapeake Bay marine life ( g. 32.40). With Coxon taking on the task of modeling, it seems that Edwin Bennett was able to experiment with clays and glazes. His “Daybook” from this period includes several recipes for blue bodies and stains, which were also used in some of the early productions of the factory, such as the jug shown in gure 32.40.150

In 1893, about forty- ve years after the founding of the pottery, Edwin AtLee Barber recorded that Bennett produced majolica in the 1850s. An oft-cited passage in his seminal book The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States suggests that Edwin Bennett was the rst American producer of majolica—and that he manufactured it as early as Minton & Co. This is highly unlikely. In his discussion of Bennett’s rm, Barber describes the retrospective display of the company’s output, which it presented at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. He notes “a majolica bust of Washington made by E. & W. Bennett, 1850; a pair of mottled majolica vases, two feet in height, with raised grape-vine designs and lizard handles, produced by him in 1856;

[an] enormous octagonal majolica pitcher, with blue, brown, and olive mottled glazes, 1853; co ee-pots and other pieces in blue, green, and olive bodies.” 151 The bust of Washington is not known to survive and so cannot be evaluated.152 Also not known to survive is the “enormous octagonal majolica pitcher,” but nonetheless, Barber’s description of mottled glazes in blue, brown, and olive does not match current understandings of majolica glazing and was likely more closely related to Bennett’s mottled-brown Rockingham. The pitcher’s glaze may be similar to that found on one example of the “mottled majolica vases” with “lizard handles” preserved in the collection of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, a gift of the wife of a Bennett descendant ( g. 32.41). In any case, Barber’s broad de nition of “majolica,” which includes Bennett’s 1850s wares, is not generally accepted as valid today, and moreover, additional evidence that Bennett produced majolica before the 1880s has not come to light.

Bennett was an important manufacturer in the United States, and his rm was located in a major American seaport. Continually employing English immigrant potters in his factory,

he was undoubtedly aware of the general developments in British ceramics of the 1850s through the 1870s, including the rise of majolica. Bennett also almost certainly had the technical expertise in his factory to produce the ware. However, it seems that he instead focused on producing the types of ceramics in high demand in the United States during this period. From the late 1840s through the 1860s, he advertised as a manufacturer of “cane,” or cream-colored ware, and “Rockingham” in the Baltimore city directories and today is recognized as a major maker of these popular products.153 The rm exhibited and won several awards for its “queensware,” or cream-colored earthenware, in the Maryland Institute Fairs of the 1850s.154 He also was very interested in producing practical kitchenware. In the 1850s and 1860s, Bennett patented several designs for earthenware jars for use in food preservation—items that likely saw ready sales in the burgeoning American consumer market.155

By about 1869, Bennett expanded his o erings to include white ironstone, a change recorded in his advertisements in the Baltimore directories and documented by the fact that in 1870, he patented a lobed serving bowl likely for white ironstone production.156 In 1873, his “Queensware Manufactory” ( g. 32.42) was included in a Baltimore guidebook highlighting the city’s merchants and industry. Bennett’s rm then employed more than one hundred workers and “turn[ed] out about two thousand dozens” of ware each week. The production is described as “all kinds of White ware—Dinner, Tea and Breakfast, and Toilet sets” as well as “Brown or Rockingham ware and Yellow Fire-proof ware, for kitchen purposes.”

157 Bennett’s rst advertisement in the Crockery Journal, which ran in January 1875, a month after the periodical was founded, outlines his rm’s o erings as “White Granite & C.C. [cream-colored] Ware, Also, Yellow, and Rockingham, Fire-Proof Ware.”

158 In 1876, Bennett again expanded his business to include roo ng tiles by opening a new factory to manufacture them at the corner of Aliceanna Street and Central Avenue, adjacent to his original facility.159 He would go on to win a silver medal for roo ng tiles at the 1878 Maryland Institute Fair and to patent “an improved roo ng tile” the following year.160

During the early 1880s, Bennett gradually changed and diversi ed his pottery’s production. It is likely that the factory began making a small amount of majolica during this time, when demand was high in the United States for the brightly colored ware. An 1880 pro le of the rm emphasizes the substantial nature of the operation, noting, “Each week the factory turns out 3000 dozen pieces composed of a great variety of articles,” numbering more than three hundred items, including “dinner, tea and toilet sets, hotel and kitchen ware, spittoons, teapots, baking dishes, little and immense pitchers, &c.” 161 By 1882, the operation was slightly larger, employing 120 (compared to 100 in 1880), but on the whole, the products were the same: “white stone china and C.C. ware, Cane and Rockingham reproof ware.” 162 “Decorated ware” was added to this list, likely in response to increasing US demand in the 1870s and 1880s for decorated tableware—which might be adorned with patterns,

gilding, or colored glazes. Judging by trade journal reports, white granite and Rockingham-glazed wares continued to be the company’s main productions, but new items, such as a teapot with a uted body patented by Bennett in 1883, were occasionally introduced.163 Another patented item, a “no-drip molasses jug,” was being made in large numbers by September 1883, and by December, the model was being o ered in white as well as “prettily decorated.” 164 These molasses or syrup jugs were made with a wide variety of decorations, including transfer prints; with molded embellishments and painted in imitation of jasperware; with molded embellishments in mottled glazes of browns, yellows and greens; and in bright solid-color majolica glazes ( g. 32.43).

The Chesapeake Pottery also seems to have stimulated changes in Bennett’s production. In December 1883, the Crockery and Glass Journal noted “three sets of fancy jugs, one ornamented with a sun ower, another with a rose in relief” that Bennett decorated “after the manner of very popular Avalon ware of Messrs. D. F. Haynes & Co.” 165 By April 1884, the rm had introduced “new chamber sets and a line of fancy ware.” 166 These descriptions may relate to models featured in a portfolio of “Illustrations of Artistic Wares, Manufactured by Edwin Bennett,” which is preserved in the Bennett archive at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution ( gs. 32.44A, B).167 In form, in their pattern names (“Bramble” and “Japonica”), and in the type of glazes used, the Bennett designs closely follow Haynes’s Avalon Faience prototypes and their overglaze enamel decoration ( gs. 32.45, 32.46). Later in the year, Bennett introduced a new line of parian owers, and again, he seemed to be following Haynes’s lead. The Crockery and Glass Journal notes at the end of its report on this development that “Calvertine ware,” a Haynes product, “is a strictly Baltimore specialty”—mistakenly equating the two major Baltimore rms.168

“Fine-Lined Masterstrokes of Design:” Edwin Bennett Pottery in the 1890s

In the 1890s, there were signi cant changes at Bennett’s pottery, including in the range of wares produced by the rm. Probably the most important one occurred when Henry Brunt left Chesapeake Pottery to become general manager of the newly incorporated “Edwin Bennett Pottery Company.” 169 As a result of the incorporation, Brunt in fact became a part owner of the company along with Edwin Bennett, his son E. Huston Bennett, the chief salesman Joseph L. Sullivan, and business associate Wilber T. France. Brunt soon hired Mary V. Thaler, who had trained at the Maryland Institute and “developed considerable ability in designing decorations for pottery” as the rm’s “art director.” 170 He also began to sta the decorating department with young women ( g. 32.47), as had been the practice at the Chesapeake Pottery, his previous employer.171 By early the following year, new developments at the company were being noticed. The Pottery and Glassware Reporter remarked in January 1891 that, under

syrup jugs, ca. 1875–85. Earthenware with majolica glazes and metal, far left: 7 8 ⅛ × 4 ⅝ × 3 ⅜ in. (20.6 × 11.6 × 8.5 cm); center: 6 ¾ × 5 × 4 in. (17.1 × 12.6 × 10.1 cm); center right and far right: 6 ⅞ × 4 ¾ × 4 in. (17.5 × 12.1 × 10 cm). Far left and center left, stamped mark: BENNETT’S JAN. 23, 1873 / PATENT center, center right, and far right, impressed mark: BENNETT’S PATENT [in a circle] . John Collier Collection. Cat. 328.

Brunt’s direction, the “pottery is branching out into decorating and the initial e orts promise well for the future.” 172 By summer, the same journal was extolling Bennett’s new “Clytie” dinner service in semi-porcelain (re ned white earthenware), as well as several new toilet sets in various decorations, proclaiming these e orts “show all the beauty and freshness of May, blended with the boldness and ne-lined masterstrokes of design that come only from ripened experience.” 173 A high point for the Edwin Bennett Pottery and its majolica production came in 1893 with what was perhaps the rm’s most prominent exposure to date. Bennett, like most other American potteries, was featured in a display at the World’s Columbian Exposition presented under the auspices of the United States Potters’ Association—and arranged by David Haynes, head of the Association’s design committee and a business partner of Edwin Bennett’s son at the Chesapeake Pottery. This Baltimore and family connection likely ensured both rms received prominent places at this important world’s fair, which was attended by twenty-seven million people. Bennett’s display, designed by Thaler and Brunt, was unusual in that it featured objects dating from the rst decade of the pottery’s existence in combination with a wide range of new designs and pieces created especially for the fair.174 As discussed earlier, Bennett showed a number of wares produced in the 1850s.175 Among the new designs the company presented were examples of its semi-porcelain tableware as well as a variety of toilet sets, such as the Persian shape, decorated in an intricate transfer-printed design.176 One report also notes “a handsome lot of jardinieres in various shapes” available in “twelve varieties of colored glazes,” while another mentions “jardinieres of Egyptian, Grecian, Japanese and Persian designs.” 177 Examples of the Grecian design, featuring a pro le in molded-relief decoration

and subdued colored glazes are now in a private collection ( g. 32.48). These single-color wares in their muted tones are similar to solid-color majolica being produced at about the same time by other manufacturers, both British and American.

The highlight of Bennett’s display, a monochrome-glazed plant stand with gri n supports, is the nest example of majolica produced by the rm ( g. 32.49). The company showed two of these “large oral urns of Italian Renaissance design,” as the Baltimore Sun described them.178 The Baltimore American noted that the “jardiniere, or large ower stand” was “one of the largest pieces of pottery ever made in America in one piece,” and the company was showing one in “a monochrome tint of silver gray” and the other in a “yellow which shows every graduation of tint from a deep golden yellow to a pale ivory.” 179 The rm commissioned the design from Herbert W. Beattie (1863–1918), a sculptor and designer based in Quincy, Massachusetts, with whom Brunt had previously worked.180 English by birth, Beattie was “a graduate of the South Kensington Art School, London,” and was a freelance modeler who specialized in tombstone and monument decoration but also designed a wide variety of articles including kitchen and parlor stoves.181 Beattie’s father and grandfather were also designers.182 The latter, sculptor William Beattie (ca. 1802–1867), was active as a modeler for potteries in Sta ordshire in the middle of the nineteenth century (see g. 14.18).183 Shortly before the close of the exhibition, Bennett arranged through Barber to give one of the fern stands to the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art. Barber, in his capacity as honorary curator, wrote enthusiastically on October 26, 1893, to Dalton Dorr (1846–1901), the museum’s director at the time: “It is a ne piece of work in majolica. You might suggest which color you prefer, as there are three or four

tints.” 184 A “silver grey” model entered the collection shortly thereafter.185 While it is unlikely that more than a few were made, the rm featured this tour de force of potting in company literature over the next few years.186

In the decade following the Chicago fair, Edwin Bennett Pottery continued to create a small amount of art ceramics in addition to its major production of re ned white earthenware table- and toilet wares. Named for the owners of the factory (Brunt, Bennett, and Sullivan), the Brubensul line, with its rich glazes in tones of brown, is described as of the “majolica family” by Barber, but would likely not be accepted as such today ( g. 32.50).187 Albion ware, designed and painted by Kate DeWitt Berg (ca. 1857–1929) and Annie Haslam Brinton (1867–1947), was rst introduced in 1895 ( g. 32.51).188 The company gained some notoriety for Albion, which, following in the tradition of French slip-decorated art pots, was painted with colored slips under thick rich glazes.189

Edwin Bennett Pottery’s production largely seems to have returned to table- and kitchenwares after 1900. Bennett himself was active in the company until his death at ninety in 1908. Henry Brunt continued to be the rm’s artistic and business manager until his own death in 1915. The Bennett family operated the pottery until it was forced to shut it down in 1936.

mark: E. BENNETT

CO. / 1897

/ K.B. center, painted mark:

BENNETT

/

/

(21.2 × 21.9 × 10.6 cm). Left,

/ Albion right, painted mark: E. BENNETT POTTERY / 1895 / A.B. Albion. John Collier Collection.

While the products of Edwin Bennett’s Baltimore pottery are rightfully celebrated today, Bennett cannot be considered a pioneer of American majolica production. His modest output of the lead-glazed ware in the 1880s and 1890s does not distinguish his rm, apart perhaps from a showpiece such as the gri n fern stand. David Francis Haynes’s Chesapeake Pottery was the true pioneer maker of majolica in the city of Baltimore. While its production of this ware was brief, Chesapeake contributed some of the nest examples of American majolica.

For their generous assistance in the research for this essay, the author wishes to thank Alisse Cable Craig and J. David Cable; John M. Collier; Bonnie Campbell Lilienfeld, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution; Alexandra Deutsch, Catherine May eld, Paul Rubenson, and Damon Talbot, Maryland Historical Society; and Laura Microulis, Bard Graduate Center.

1 Henry Brunt, “American Pottery Trade in 1908,” Brick 30, no. 3 (March 1909): 175.

2 The account of Bennett producing majolica in the 1850s seems to have been rst recorded by ceramic historian Edwin AtLee Barber (1851–1916) in 1893. See Edwin AtLee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art from the Earliest Times to the Present Day (New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893), 195–99. Subsequently, Barber’s account has been repeated almost verbatim in more recent literature. See, for example, M. Charles Rebert, American Majolica, 1850–1900 (Des Moines: Wallace-Homestead, 1981), 16–18; and Marilyn G. Karmason with Joan B. Stacke, Majolica: A Complete History and Illustrated Survey (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1989): 142–44.

3 Baltimore, Maryland, The Monumental City, the Liverpool of America, with the Finest Harbor in the World [. .] (Baltimore: Baltimore American, 1894); and Baltimore: The Gateway to the South, the Liverpool of America (Baltimore: Mercantile Advancement Co., 1898).

4 Unless otherwise noted, information in this section is taken from Frances Haynes, ed., Walter Haynes of Sutton Mandeville, Wiltshire, England, and Sudbury, Massachusetts, and His Descendants, 1583–1928 (Haverhill, MA: Record Pub. Co., 1929), 118–20, 152–54.

5 George Adams, “Lowell Advertisements,” in The Lowell Directory (Lowell, MA: Oliver March, 1851), 9. A genealogical account of Brown and his daughter Anstress, Haynes’s rst wife, indicates that Haynes joined Brown’s rm in November 1851. Abiel Abbot Livermore and Sewall Putnam, History of the Town of Wilton, Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, with a Genealogical Register (Lowell, MA: Marden and Rowell, 1888): 328–29. David Francis is listed in the 1850 census as living with his family in Barre, MA. Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, National Archives, Washington, DC (hereafter abbreviated as NAW), Ancestry.com. He rst appears in the Lowell directories in 1853 (a directory was not produced in 1852). See George Adams, The Lowell Directory (Lowell, MA: Oliver March, and Merrill and Straw, 1853), 126.

6 Patent no. 13,157, dated July 3, 1855, for “an improved thief-detector or alarm apparatus to be applied to money-drawers,” https://patents.google.com /patent/US13157. For more on Brown’s patented products, see “Brown’s Safety Alarm Detectors,” American Farmer’s Magazine 10, no. 5 (November 1857): 290–91. Haynes was the junior partner with Brown in the venture to manufacture and sell the locks in the UK as is recorded in a partnership agreement dated September 15, 1855, and now in the possession of Haynes’s descendants Alisse Cable Craig and J. David Cable. In 1880, Haynes made another trip to England, and a reporter for the Crockery and Glass Journal noted in May, “He expects to renew many friendships formed during a twelve months’ residence there some twenty years ago or more.” “Baltimore Reports,” Crockery and Glass Journal (hereafter abbreviated as CGJ ) 11, no. 21 (May 20, 1880): 19.

7 Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States 320.

8 Haynes recorded the details of his year abroad in letters published in 2 Massachusetts newspapers: the Lowell Weekly Journal and Courier and the Barre Gazette Though most of the issues in which these letters appear do not survive in widely accessible sources, Haynes kept a scrapbook of the published letters, which is inscribed on its rst page, “D. F. Haynes / Lowell / Nov 25th / 1856 / Letters written by D. F. Haynes to the / Barre Gazette of Barre Mass at the / age of 21 years.” I thank Alisse Cable Craig and J. David Cable for sharing this scrapbook with me. Three of Haynes’s letters can be found in widely accessible sources. H. D. F. [David Frances Haynes], “European Correspondence of the Gazette: Birmingham, Its Early History—Politics—Churches—Public Buildings, & c., June 14th 1856,” Barre Gazette July 4, 1856, 3; D. F. H. [David Frances Haynes], “European Correspondence of the Gazette, Paris, Sept. 27th, 1856,” ibid., November 7, 1856, 3; and D. F. H. [David Frances Haynes], “Correspondence of the Gazette, Lowell, Nov. 15th, 1856,” ibid., November 26, 1856, 2.

9 Haynes is listed in the 1855 Lowell directory. See George Adams, The Lowell Directory (Lowell, MA: Oliver March, and Merrill and Straw, 1855), 92. He is not included in the 1858 directory (no directory was published 1856–57), but his brother Henry Stone Haynes is listed as operating Brown’s former crockery and glass store and Brown, a “patent alarm locks” business. See Adams, Sampson & Co., The Lowell Directory (Lowell, MA: Joshua Merrill and B. C. Sargeant, 1858), 49, 111, 225, 330. Haynes rst appears in the Baltimore directories in 1858, when he is listed as a “bookkeeper.” See The Baltimore City Directory (Baltimore: Richard Edwards and William H. Boyd, 1858): 152.

10 They were married December 14, 1858, in Barre, MA. Hartford Times, January 6, 1859, Newspapers and Periodicals, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, Ancestry.com. A family Bible owned by Haynes and now in the possession of Alisse Cable Craig and J. David Cable con rms this, recording on the “Marriages” page that “D. Frank Haynes & Anstress Brown / were married Dec. 14th 1858 at Barre Mass / By Rev Mr Derham.”

11 His daughter noted that Haynes was unable to serve in the military during the Civil War because of a broken ankle that had healed badly, but Abbott “made D. F. Haynes, the Sup’t of the job, which had to be done in record time, thus assuring him he was loyally serving the Cause.” Haynes, Walter Haynes 53, 153.

12 The plant, Mount Vernon Forge, was located near what is now the town of Grottoes, VA, and Shenandoah National Park.

13 Advertisement, Staunton Spectator and General Advertiser August 25, 1868, 2.

14 Advertisement, ibid., November 30, 1869, 2. “Queensware” is a generic term used at the time to denote cream-colored earthenware.

15 The death of Anstress Brown on February 20, 1870, was noted in Baltimore. “Death of an Estimable Lady,” Baltimore Sun February, 26, 1870, 1. In October 1870, the damage to the ironworks was estimated to be several thousand dollars. “Mount Vernon Iron Works,” Staunton Spectator and General Advertiser October 25, 1870, 2. By November, Haynes was liquidating his store’s inventory. See advertisement, ibid., November 22, 1870, 2.

16 Ammidon & Co. advertisement in George W. Howard, The Monumental City, Its Past History and Present Resources (Baltimore: J. D. Ehlers and Co., 1873), 234. This partnership is dated April 1, 1871. “Copartnership Notices,” Baltimore Sun April 7, 1871, 2. Founded in 1858 by John P. Ammidon, also a native of MA, the rm rst advertised coal oil and patent lamps in September. Advertisement, ibid., September 22, 1858, 3. For a biography of Ammidon, see Lynn R. Meekins, Men of Mark in Maryland (Baltimore, Washington, DC, and Richmond, VA: B. F. Johnson, Inc., 1910), 2:123–24. Ammidon and Haynes likely knew each other from their youth in Lowell, MA, where they both lived in the early 1850s, and remained lifelong friends. Ammidon attended high school in Lowell, graduating in 1847. Ibid., 123. He is listed in the Lowell directories for 1849, 1851, and 1853. See The Lowell Directory and Business Key for 1849 (Lowell, MA: Oliver March 1849), 24; George Adams, The Lowell Directory (Lowell, MA: Oliver March, 1851), 19; and George Adams, The Lowell Directory (Lowell, MA: Oliver March and Merrill and Straw, 1853), 43. Both Haynes and Ammidon were leaders in the Brown Memorial Church of Baltimore. J. E. P. Boulden, The Presbyterians of Baltimore, Their Churches, and Historic Graveyards (Baltimore: Boyle and Son, 1875), 122. Although Ammidon preceded him in death, his son was one of the pallbearers at Haynes’s funeral. “Mr. D. F. Haynes Buried,” Baltimore Sun August 28, 1908, 7.

17 “A Leading Baltimore House,” Crockery Journal 1, no. 10 (March 13, 1875): 6. This publication was renamed the Crockery and Glass Journal from vol. 2, no. 1 (July 8, 1875).

18 Ibid.

19 For Ammidon leaving the business, see “Mr. D. F. Haynes Dead,” Baltimore Sun , August 25, 1908, 12. D. F. Haynes & Co. is listed under “China, Glass and Queensware” in the 1877 and subsequent Baltimore directories. Woods’s Baltimore City Directory (Baltimore: John W. Woods, 1877). The rm is no longer listed under “Coal Oil,” “Lamps and Oil,” or “Oil Dealers and Re ners” as Ammidon & Co. had been.

20 D. F. Haynes & Co. brochure, 1882. I thank Nicolaus Boston for sharing this brochure with me.

21 The text of Haynes’s rst Maryland Queensware promotion includes the date “June 1st, 1879” even though it was published in August. See D. F. Haynes & Co. advertisement, CGJ 10, no. 7 (August 14, 1879): 12. A later report states that Haynes took the rm’s full production. “Baltimore Trade Reports,” CGJ 11, no. 14 (April 1, 1880): 10. An 1885 article indicates the rm was founded in 1879. “Maryland Queensware,” Baltimore Sun December 17, 1885, 3.

22 D. F. Haynes & Co. advertisement, CGJ 10, no. 7 (August 14, 1879): 12. See also “D. F. Haynes & Co. [. .],” ibid., 16.

23 “Baltimore Trade Reports,” CGJ 10, no. 23 (December 4, 1879): 18.

24 “Baltimore Trade Reports,” CGJ 11, no. 14 (April 1, 1880): 10. McNulty was a native of Belfast, Ireland, who came to the US in 1861, served in the Civil War, and worked in the Trenton potteries, before moving to Baltimore to manage Maryland Queensware (subsequently Maryland Pottery Co.), “Deaths: Mr. Thomas McNulty,” Baltimore Sun , March 12, 1890, 6.

25 “D. F. Haynes & Co.,” CGJ 12, no. 17 (October 21, 1880): 32.

26 “Baltimore Reports,” CGJ 14, no. 22 (November 24, 1881): 41. The transferprinted decorations included “jockey scenes” as well as “American game— birds, deer, ducks, partridges, orioles, etc.,” which had been “specially engraved for this rm by an American artist,” ibid. See also “Baltimore Reports,” CGJ 13, no. 16 (April 14, 1881): 32, and “Baltimore Reports,” CGJ 14, no. 12 (September 15, 1881): 42.

27 “Baltimore Reports,” CGJ 15, no. 3 (January 19, 1882): 26.

28 “Copartnership Notices,” Baltimore Sun , November 20, 1880, 2. Tunstall applied to construct 2 buildings and install a “steam boiler and engine, 45-horse power” at the Chesapeake Pottery site earlier the same year.