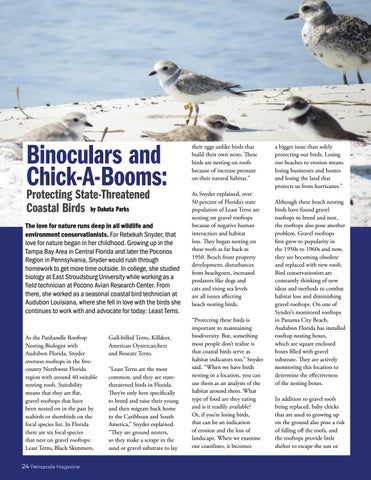

Binoculars and Chick-A-Booms: Protecting State-Threatened Coastal Birds

by Dakota Parks

The love for nature runs deep in all wildlife and environment conservationists. For Rebekah Snyder, that love for nature began in her childhood. Growing up in the Tampa Bay Area in Central Florida and later the Poconos Region in Pennsylvania, Snyder would rush through homework to get more time outside. In college, she studied biology at East Stroudsburg University while working as a field technician at Pocono Avian Research Center. From there, she worked as a seasonal coastal bird technician at Audubon Louisiana, where she fell in love with the birds she continues to work with and advocate for today: Least Terns.

As the Panhandle Rooftop Nesting Biologist with Audubon Florida, Snyder oversees rooftops in the fivecounty Northwest Florida region with around 40 suitable nesting roofs. Suitability means that they are flat, gravel rooftops that have been nested on in the past by seabirds or shorebirds on the focal species list. In Florida there are six focal species that nest on gravel rooftops: Least Terns, Black Skimmers, 24 Pensacola Magazine

Gull-billed Terns, Killdeer, American Oystercatchers and Roseate Terns. “Least Terns are the most common, and they are statethreatened birds in Florida. They’re only here specifically to breed and raise their young and then migrate back home to the Caribbean and South America,” Snyder explained. “They are ground nesters, so they make a scrape in the sand or gravel substrate to lay

their eggs unlike birds that build their own nests. These birds are nesting on roofs because of increase pressure on their natural habitat.” As Snyder explained, over 50 percent of Florida’s state population of Least Terns are nesting on gravel rooftops because of negative human interaction and habitat loss. They began nesting on these roofs as far back as 1950. Beach front property development, disturbances from beachgoers, increased predators like dogs and cats and rising sea levels are all issues affecting beach nesting birds. “Protecting these birds is important to maintaining biodiversity. But, something most people don’t realize is that coastal birds serve as habitat indicators too,” Snyder said. “When we have birds nesting in a location, you can use them as an analysis of the habitat around them. What type of food are they eating and is it readily available? Or, if you’re losing birds, that can be an indication of erosion and the loss of landscape. When we examine our coastlines, it becomes

a bigger issue than solely protecting our birds. Losing our beaches to erosion means losing businesses and homes and losing the land that protects us from hurricanes.” Although these beach nesting birds have found gravel rooftops to breed and nest, the rooftops also pose another problem. Gravel rooftops first grew to popularity in the 1950s to 1960s and now, they are becoming obsolete and replaced with new roofs. Bird conservationists are constantly thinking of new ideas and methods to combat habitat loss and diminishing gravel rooftops. On one of Synder’s monitored rooftops in Panama City Beach, Audubon Florida has installed rooftop nesting boxes, which are square enclosed boxes filled with gravel substrate. They are actively monitoring this location to determine the effectiveness of the nesting boxes. In addition to gravel roofs being replaced, baby chicks that are used to growing up on the ground also pose a risk of falling off the roofs, and the rooftops provide little shelter to escape the sun or