Bahá’í Publishing

1233 Central St., Evanston, IL 60202

Copyright © 2025 by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States

All rights reserved. Published 2025

Printed in the United States of America ∞

28 27 26 25 1 2 3 4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Barnes, Kiser D., author. | Grant, Linda Ahdieh, author.

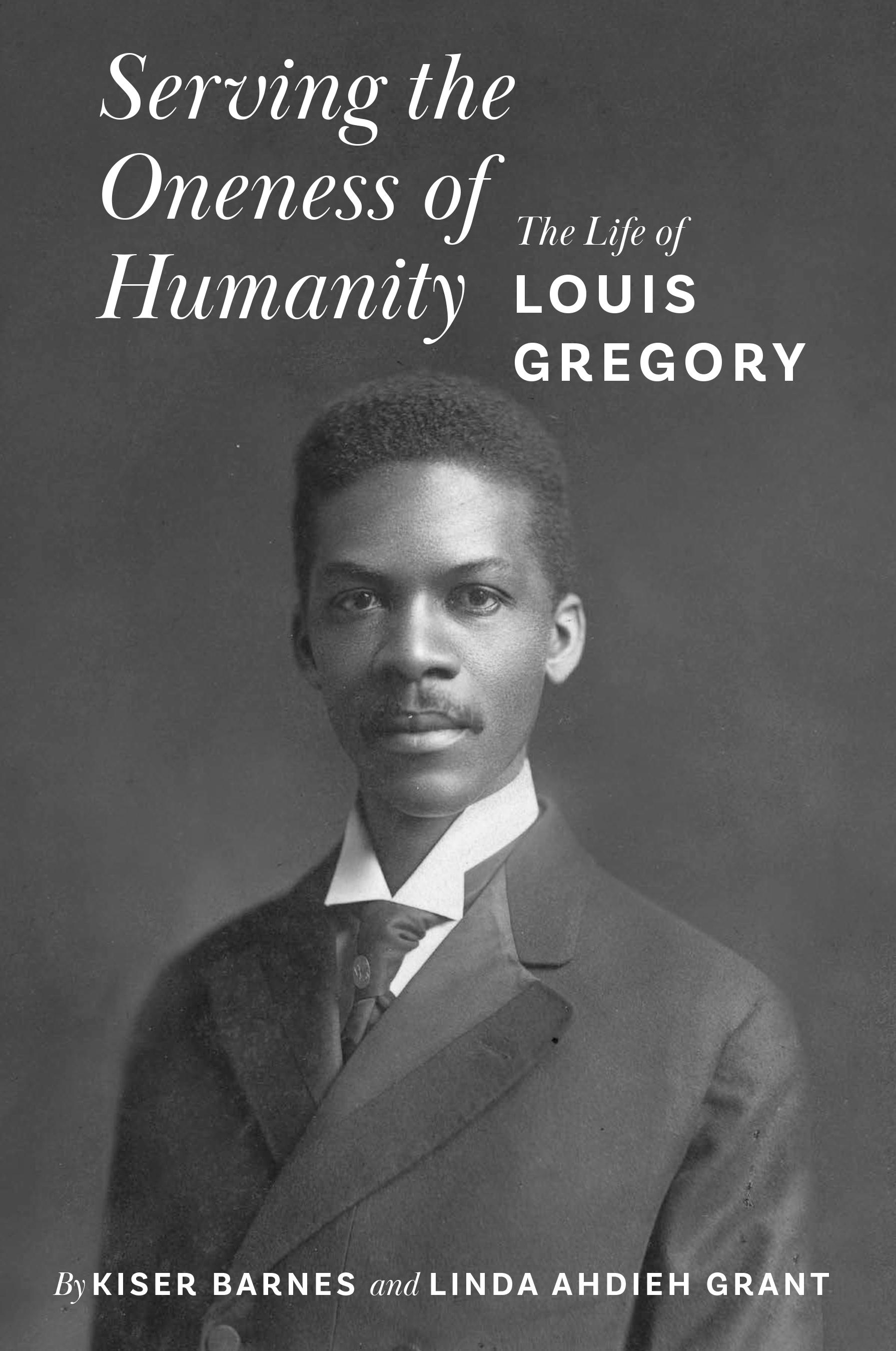

Title: Serving the oneness of humanity : the life of Louis Gregory / by Kiser Barnes and Linda Ahdieh Grant.

Description: Evanston, IL : Bahá’í Publishing, 2025. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2025026568 (print) | LCCN 2025026569 (ebook) | ISBN 9781618512642 (paperback) | ISBN 9781618512659 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Gregory, Louis G. | Hands of the Cause of God—United States—Biography. | African American Bahais— Biography. | Bahais—United States—Biography. | Bahai Faith. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC BP395.G73 B376 2025 (print) | LCC BP395. G73 (ebook) | DDC 297.9/3092 [B]—dc23/eng/20250607

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2025026568

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2025026569

Cover design by Carlos Esparza

Book design by Patrick Falso

INTRODUCTION

“In this illumined age that which is confirmed is the oneness of the world of humanity. Every soul who serveth this oneness will undoubtedly be assisted and confirmed.” —‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’lBahá, no. 77.1.

This book considers Louis George Gregory’s unique and historic contributions toward advancing racial unity in America and beyond. These contributions were grounded in his full embrace of the teachings of the Bahá’í religion “directed toward . . . [the] spiritual transformation of both the individual and of society”1 and the oneness of humanity, “the pivot round which all the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh revolve.”2 Louis Gregory fully realized that this reality held the potential to “alter completely the patterns of racial discrimination reinforced by class, caste, and religion in America and throughout the world and ultimately to create a new world civilization in which the characteristics and contributions of all peoples would play a part.”3 Louis Gregory himself asserted that what “‘the majestic Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh brings . . . is not black or white or yellow or brown or red, yet all of these. It is the power of divine outpouring and endless perfection for mankind.’”4

He manifested commitment to this new Revelation in every facet of his adult life, including his marriage; his law practice; his heroic services spreading teachings of the Bahá’í Faith; his election as the

first Black American member of the National Spiritual Assembly, the highest Bahá’í administrative institution in America; and his role as a key participant in Race Amity Conventions in cities throughout the country following a series of violent racial riots across the United States.

The Louis G. Gregory Public Museum at Charleston, South Carolina; the Louis G. Gregory Training Institute, a national educational center in Hemmingway, South Carolina; and the Louis G. Gregory Children’s School in Eliot, Maine, are also inspiring and enduring testaments to Louis Gregory’s lifelong belief that the transformation of society could be built on spiritual principles.

Of Louis Gregory’s unique services, Glenford Mitchell has observed that “‘Being one of the earliest Bahá’ís in America, Louis Gregory, the son of slaves, proved to be not only a luminous example in this sense but also, and more important, an instrument of change. His forty years of unremitting labor in promoting race amity was unprecedented in its scope, generated as it was by a universalism incomprehensible even to the most distinguished of the civil rights activists who were his contemporaries.’”5

The African-American lawyer, community activist, writer, newspaper editor, and lecturer was called by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá—the leader of the Bahá’í Faith in the early 1900s—to “‘become . . . the means whereby the white and colored people shall close their eyes to racial differences and behold the reality of humanity, and that is the universal unity which is . . . the basic harmony of the world . . .’”6

Louis Gregory clung to the Master’s guidance.7 He said of ‘Abdu’lBahá, “‘He is able to make all places fruitful’” and “‘His is a wonderful culture of hearts and minds.’”8 Janet Ruhe-Schoen wrote, “[Louis Gregory had] found the fulfillment of his heart’s deepest desire, the longing that had entered him when he was a child in the midst of a violent tragedy.” He wanted to help remove racial disunity, and he wanted humanity to be one, united in love.9

When he studied at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee and Howard University’s law school in Washington, DC, Louis “placed

his undiminished concern for the welfare of his people within a universal context: the establishment of a new world order founded, like the great civilizations of the past, on faith in a Supreme Being and on an ennobling vision of human destiny.”10

He shared Bahá’í teachings with Blacks and whites in large cities and small towns throughout the country, particularly in the South, where “his advocacy of racial unity could easily have cost him his life.”11 According to Glenford Mitchell, “‘The life of Louis Gregory produced the litmus test of the workability of the Bahá’í teachings in effecting race unity. The successful result of this unprecedented effort would be an example to all peoples for all time.’”12 Louis Gregory had “lived his life in the forefront of a struggle that is still being waged” and “the immediacy of his example has the power to inform and to inspire.”13 He is described as “one of the spiritual giants of his era” and “an historic figure.”14 He was “‘a unique instrument in the binding together’” of people of different races.15

Louis Gregory was among the first generation of African Americans born free in the United States after slavery ended. However, he suffered, throughout his long life, the lurking humiliations and pains of living in a society plagued by racism. After the Civil War, Blacks had hoped they would finally be free not only from slavery but also from racial prejudice. However, this initial hope was replaced by the gradual realization that new forms of dominance, based on notions of white supremacy, had become the new reality in American society. Still hopeful that the sufferings of Black people in America would eventually be removed, Blacks had continued singing from the Negro Spirituals: “I’m so glad trouble don’t last always.”16 They continued, along with like-minded people of other races, to struggle against racial inequality.

Louis Gregory’s parents and grandparents knew they needed to safeguard his well-being as much as possible. They had no public education and lived in poverty, and they knew protecting their child would be a challenge. They knew, for instance, that many Southern white people would subject him to mistreatments. Realizing