Earl Cameron

An Actor’s Journey

Edited by

Jane Cameron Sanders and Robert Weinberg

Paterson

Ira

Jane

Roger

David

Quinton Astwood

Helen Rutstein

Karmeta Hendrick and Kelly Hodsoll

Jane Cameron-Sanders

Chapter One

I WAS BORN IN Hamilton, the capital city of Bermuda on 8 August 1917, the youngest of six children – three girls and three boys – and grew up on that delightful little island, which is now about ninety minutes’ plane ride from New York. In those days, Bermuda was a very peaceful place, with little happening apart from the thriving tourist trade that kept things quite solvent.

I was five years old when my father passed away. My mother worked as a chambermaid at the American House Hotel. It was not an easy life for her and our childhood was by no means luxurious. Somehow or other we all managed to survive, kept reasonably happy, and I have indeed a lot to be thankful for. We were not a particularly religious family. My mother went to church from time to time and like every kid, I went to Sunday School, but we were taught at home to have good manners and to be courteous to others. I was a bit spoiled by my three sisters – I never learned to cook because they cooked everything. Whenever I went into the kitchen, they would say “Get out of here!” I didn’t even learn how to boil an egg. They never gave me a chance.

My first experience of the cinema was when my sister took me to see a silent movie at the Aeolian Hall on Angle Street in Hamilton and I saw people moving up on the screen. After that, every time I saw a White man walk past our house, I would say, “Hey, that’s the man who was in the film.” I could never have imagined that I would become an actor, or what life had in store for me.

I attended the Central School which was not far from our home. On the whole, our education was far from satisfactory. Like many Bermudan boys, I left school at the age of 13. I started learning a trade as a plumber but, after a couple of years, I realised that plumbing was not quite what I wanted to do and I followed my friends into jobs in various hotels, as a bellhop or a waiter. But the thing that held the greatest fascination for me was meeting with the guests.

Bermuda at this time was a very racially prejudiced island. In schools and cinemas, even in some of the churches, segregation was ever present. In the main cinema in Hamilton, all the best seats were for the Whites and the ten rows at the

Earl’s mother, Edith

Left: “Guns at Batasi” (1964)

front were for the Blacks. Even at this early stage of my life, I could not come to terms with such an unforgivable evil. Only a few generations before, Bermuda had practised slavery. While the majority of the population was Black, power was in the hands of the wealthy Whites – descendants of the former slave masters who then adopted laws and policies designed to ensure their economic and political dominance. Although the average Black Bermudian seemed to have accepted these conditions as quite normal and natural, deep down they knew it was wrong.

Looking back on those times, I recall one incident that particularly affected me. The great world boxing heavyweight champion at that time was Joe Louis, known as “The Brown Bomber”. His wife Marva, who was very fair, had checked into the Hamilton Hotel with her friend who was also light-skinned – maybe even White. They were there for a few days and when the hotel got news that she was Joe Louis’s wife but was not Caucasian, they forbade her from staying at the hotel. Perhaps this further experience of injustice contributed to my yearning to see what the rest of the world was like. I had always had a strong desire to travel. As a child I would watch the big ships going out to sea and say to myself, “One day, I will be on one of them.”

While waiting for my chance to get away, I would hang out with friends on Angle Street, just a bunch of guys having fun. It was during this time that I got involved with a girl called Marjorie, which resulted in the birth of a baby son, Quinton. But I wasn’t ready to settle down, especially because her parents didn’t approve of me, and when I was twenty, an opportunity came up to get a job on a ship, Monarch of Bermuda. I didn’t hesitate. Like her luxurious sister ship Queen of Bermuda, the Monarch sailed weekly between

Bermuda and New York, carrying six hundred passengers, plus crew. She would leave Hamilton on a Wednesday, arrive in New York by Friday, start her return the next day and get back to Bermuda by Monday.

Seeing New York City for the first time was like entering another planet. This was 1938, long before cars and other motor vehicles were allowed on Bermuda’s roads, everything was either horse and buggy or carts and bicycles. In New York, there were thousands of cars going up and down, and crowds of people surging everywhere.

The excitement of New York made a great impression on me. In those days, it was indeed swingin’, especially Harlem. Soon after our ship arrived at New York’s docks on a Friday, it became quite a habit for a few of us to make our way uptown to West 125th Street and catch a show at the Apollo Theatre where we would see all the great musicians, such as Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Tiny Bradshaw, Chick Webb and a host of other well-known bands of that time. Each band would be resident at the Apollo for a week. After the show, we ventured further uptown to the Savoy Ballroom. These were peaceful times in comparison with what was just around the corner for the planet. Within a year, Hitler would march into Poland, setting the stage for the Second World War.

After a year or so working on the Monarch, my desire to see more of the world became stronger. I applied for a job on another ship, The Eastern Prince, also owned by the Furness Withy Line. On 18 June 1939, we left New York for six weeks’ sailing to Buenos Aires, calling at Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, Santos and Montevideo, returning to Buenos Aires. The return trip took six weeks. By now, I was a fairly seasoned seaman and found those South American countries fascinating.

Chapter Two

ON 26 OCTOBER 1939, just a few weeks after the war started, we arrived at Woolwich Docks in the east of London. The Eastern Prince was to remain in dock for a couple of weeks before it returned to New York.

As it happened, I was fascinated with London and found it very exciting, but the thought of staying did not enter my mind. At night, everything was blacked out. We were issued with gas masks and forced to carry them with us at all times. To be honest, I didn’t think they would offer much protection if a full-scale gas attack were to actually happen. I recall one of the evening newspapers’ headlines in early December announcing, “Peace by Christmas”. Little did we realise that the world was facing more than five years of the most terrible war it had ever known. As for me, I was faced with my own personal battle, trying to earn a living and finding any kind of job to keep myself alive.

After a few days in the East End, I decided to take a bus and look for some place where Black people might hang out. I was told to get out at the corner of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road and ask someone for an address on Bateman Street in Soho. After a couple of enquiries, I found out how to get to this place, five or six minutes’ walk away. The café was owned by a Jamaican and was pretty seedy, certainly by Bermudian standards. I ordered a cup of tea and sat down hoping to find someone to have a chat with. A couple of guys came in and went through to the back. After a while I asked, “What’s going on in there?” The waiter asked me if I had ever shot dice and I replied that I had, a few times. I learned there

was a dice game going on and I was free to join them if I cared to. I wasn’t sure if it was a good thing to get involved, but I had set out hoping to meet with a few Black people to chat to, as I had hardly seen any since I left the ship.

There were about seven guys around the gambling table including a short guy who was running the game, known as Chicken. To be honest, I would never have ventured into an environment like that in New York, but somehow these guys – although they looked somewhat rough – had a friendly air about them. The stakes were not very high, about two to five shillings a time, which suited me fine. I was not prepared to risk losing any worthwhile money, I was just looking for camaraderie. Although they obviously knew each other well, they warmly accepted me.

After an hour or so, and losing about 15 shillings, I decided I’d had enough of this kind of friendship. There was one very rough looking guy they called Daisy. I knew from the start that he was the type to stay on the right side of. A few times, he asked me to put some money down for him, which I did. Now that I wanted to leave, I pretended I had lost all my money and that I no longer had enough to get back to my ship in the East End. I asked Chicken to let me have a shilling or so for my fare back to Woolwich Docks. He refused, but to my surprise Daisy intervened. “Look, man,” he said, “this guy has lost a lot of money and he needs to get all the way back to Woolwich. Let him have the f****** fare.”

One of the reasons I pretended I was broke was also because I was concerned about walking out of there now that it was dark and, of course, with the blackout, one of these guys could hold me up and rob me. However, I need not have worried as, within a few weeks, I got to know most of them and they were not the type to rob another Black man.

Chapter Twelve

LIKE MOST ACTORS, I had been knocking at the door of the film industry for some time but my big break into films came in 1949, eight years after I had first stepped out onto the stage in Chu Chin Chow.

I had screen tested for Zolton Korda for Cry, the Beloved Country which did not work out for me, but it did give me the chance to become friends with a young American actor called Sidney Poitier. The first time I met Sidney, I could not help but be very impressed by him. He just looked so fresh. He had come over from the States after getting wonderful notices for his first film No Way Out, alongside Richard Widmark. Sidney was testing for the part in Cry, the Beloved Country of Absolom, the preacher’s son. However, when Korda saw Sidney, he realised that he would be better for the part of Reverend Msimangu for which I was being considered. Around that same time, I was preparing to play the part of a Zulu and – because I was too light skinned for the potential role – I had spent a lot of time going up and down to Camden Town to get an artificial tan, rather than studying my lines for Cry, the Beloved Country. I simply didn’t know the words very well for the screen test and was not very good. I could tell Korda was a bit dismissive of me and I didn’t hear any more from him. Two or three weeks later, I decided to take the bull by the horns and phone him. It must have been one of his bad days.

“Look,” he said abruptly, “you came to the studio, you didn’t know your lines. It is unforgivable for an actor not to know his lines. Goodbye.” And he slammed down the

phone. Needless to say, Sidney got the part and I was left out in the rain.

However, it all worked out in my favour. A few weeks later I landed the major part of Johnny in Pool of London, a role for which Sidney would have been the obvious person, but he was away shooting Cry, the Beloved Country in South Africa.

At that time, I was playing the lead in a musical called Thirteen Death Street Harlem. It was a terrible thing and I hated it. The show was just as bad as the title, and it had been losing money from the beginning. We had done most of the London dates – including the Metropole, Edgware Road, Chiswick Empire and others – and that week, we were at the Walthamstow Empire Theatre. There were future bookings lined up around the country at all the Stoll and Moss Empire theatres. I was not looking forward to a long tour playing a part which I strongly disliked, so I took the opportunity to phone a young lady I knew who was working for a film company. She mentioned that Ealing Studios were planning to make a picture called Where No Vultures Fly in Kenya. I immediately called Ealing’s casting director, Margaret Harper Nelson. She said they would not be shooting the film until November. I had told her my name and she said, “I have seen your picture in Spotlight and you could be right for a part in a film we are planning to shoot starting next month. Would you be free to go to Denham Studios this afternoon?”

I explained I would need to be back in Walthamstow by six as I was in a show there. She soon rang me back and said she had arranged for me to meet the director Basil Deardon at half past two that afternoon. I would have plenty of time to get back for my performance.

We met as agreed and had quite a chat about the work

in films was beginning to come more naturally to me and I loved it. From that moment on, I felt very much at home and relaxed in front of a camera.

The competition for the role of Johnny was now, as they joked in the studio, between the two Earls – Earl Hyman, who had come from America – and myself. American Earl came on the Thursday and three days later, Basil Deardon phoned me and said, “We have decided on you for the part.” This was music to my ears. At last, I could say goodbye to Thirteen Death Street Harlem. Fortunately, I had not signed a contract with the show, mainly because when I joined it, it had been losing money. The manager had promised that when they broke even, they would give me the fee I had first asked for. The box office had in fact picked up, but all I got were promises. This suited me fine when I realised the possibility of getting this wonderful part in Pool of London. On the Monday following receiving the news from Ealing Studios, I went to the manager’s office and said, “I would like to have a chat.” He greeted me with, “I know what you want to talk to me about but Earl, we still can’t put your money up. I know the houses have improved, but we still haven’t broken even.”

“Alan,” I said, “I’ve not come to ask you for the pay that was originally agreed when the show picked up.”

His face lit up. “Oh, good, so what is it you’d like to talk about, Earl?”

“I want to give you two weeks’ notice.”

“You what? You can’t do that!”

I reminded him that I had not signed a contract. He threatened to have me black-listed with Equity. “As you like,” I said, knowing that he didn’t have a leg to stand on, and I left the office.

A Guyanese actor named Cy Grant took over from me in Thirteen Death Street Harlem and two weeks later I set off again for Ealing Studios for my first day shooting Pool of London, this time with a fat contract under my belt.

“Pool of London” (1951) - with Bonar Colleano (right) and Susan Shaw (facing page)

Chapter Twenty-One

WE BECAME VERY ACTIVELY involved in the local Bahá’í community in Ealing. Audrey ran a class for the children and put a lot of effort and attention into that. But after nine years, we felt that the time was right to make a move to an area where we could offer more service to the Bahá’í Faith. Because it has no clergy or salaried teachers, there was a great emphasis at this particular stage in the Faith’s growth for members to consider moving to different parts of the country, or indeed further afield, to put down roots and begin the process of building a new pattern of community life based on the Teachings of Bahá’u’lláh. There is no compulsion to do so and Bahá’ís are absolutely free to choose, through their own conscience, whether they are willing and able to do this.

We decided on Welwyn and Hatfield as Bahá’ís were needed there to make up the requisite numbers to be able to form a Local Spiritual Assembly, the nine-member elected body that administers the affairs of every Bahá’í community. We discussed our plans with the children and all agreed to make the move. We found a four-bedroomed home in Bell Bar, near Potters Bar which suited us fine. We knew it would not be difficult to rent our house out in Ealing which would cover the rent for our new place. Soon after moving to Bell Bar, another Bahá’í friend moved into the area which enabled us to establish the Assembly.

By this time, Jane, Simon and Helen, had completed their schooling at the Lycée and were ready to start university. Jane chose a secretarial course and Simon and Helen went

to Glasgow University. Serena and our youngest daughter Philippa – who was born in 1967 – attended a local school nearby. Audrey had become a salesperson for a linen hire company. This worked out well for a number of years as a backup to my sometimes precarious life as an actor. As always, there could often be long periods of waiting for my agent to call. So, in between the occasional parts in TV and film, I was able to support Audrey in her travels around the country. For a large part of our married life, we also hired au pairs who were a great help to our large family.

One day, we received a letter from a Bahá’í friend who lived in Western Samoa, Suhayl Ala’i, who was passing through London on his way to the Bahá’í World Centre in the Holy Land. We had met Suhayl once before and talked about perhaps even moving to somewhere in the Pacific. At that time, we had hardly been in any kind of position to make such a move, but now most of our children had grown up and our house in Ealing was fully paid for.

Audrey and I discussed the possibility of making such a tremendous change for all the family and eventually came to the decision to look carefully into a potential new life overseas in the Solomon Islands. It is a very remote part of the world, with a good proportion of its citizens travelling or resident outside of the country. Simon and Helen would continue to attend University in Glasgow, Jane, Serena and Philippa could come with us to continue their education in the Solomons. It was all well worked out but, as you soon learn in life, things rarely go as planned.

I took a trip to the Solomons for a couple of months to try and assess the situation. Suhayl had introduced us to a man called Bruce Saunders who told us about an ice cream business which had been up for sale for a couple of years,

situated in the marketplace in Honiara, the capital city on the largest island Guadalcanal. I met Bruce on arrival at Honiara airport.

At the time they were building a new Bahá’í centre and I was taken to the old place, which was very dilapidated. Bruce told me I could stay there if I wanted to. Suddenly my phobia about rats took hold of me and I thought, “There’s no way I’m going to spend the night here. I’m going to a hotel.” There was an American guy called Bob Darrow who was helping to build the new centre and he watched my face when Bruce said, “By the way Earl, you can sleep over there.” After Bruce left, Bob said, “You can stay at my place if you want to.”

Shortly after my arrival, I took a look at the ice cream parlour, if you could call it that. It was a small but very solid building, with more than sufficient space for making ice cream, with a nice frontage for serving customers. There was an office in the back, with storage available for cones, milk powder and flavourings. But the equipment for making the ice cream was, for the most part, obsolete and all the machinery needed to be replaced, which I had more or less expected. It would take time for it all to be imported from Australia.

The asking price for the business was US$23,000. Not having had any experience of business my entire life, it would be a big risk. To be truthful, I was getting cold feet about it and beginning to think of ways of making my way back to the UK where I felt a lot more secure. Bruce invited me to his house to meet the parlour’s owner, an American by the name of Fox who had started the business some years before, had gone into shipping, became a millionaire and was now living in New York. It was a coincidence that he was

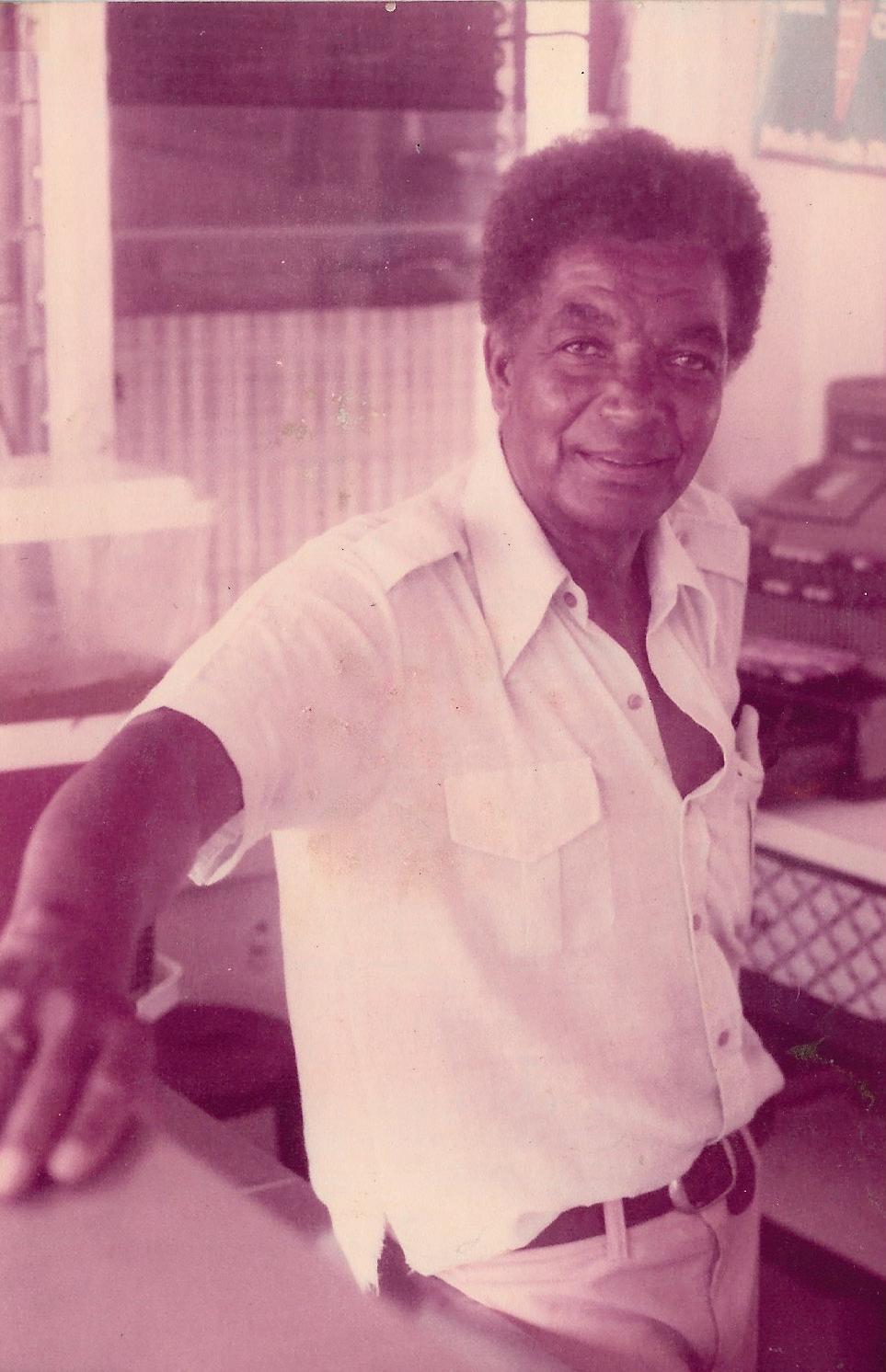

Earl in the Solomon Islands

End of this sample.

To learn more or to purchase this book, Please visit Bahaibookstore.com or your favorite bookseller.